Abstract

In Montana, American Indians with chronic illnesses (CIs) die 20 years earlier than their White counterparts highlighting an urgent need to develop culturally consonant CI self-management programs. Historical and current trauma places Indigenous peoples at increased health risk relative to others, and negatively influences CI self-management. The Apsáalooke Nation and Montana State University partnered to develop and implement a trauma-informed CI self-management program to improve the Apsáalooke community’s health. This paper describes the origins and development of the trauma-informed components of the program. Using community stories and a literature review of trauma-informed interventions, partners co-developed culturally consonant trauma materials and activities grounded in community values and spirituality. Trauma-informed content was woven throughout three intervention gatherings and was the central focus of the gathering, Daasachchuchik (‘Strong Heart’). Apsáalooke ancestors survived because of their cultural strengths and resilience; these cultural roots continue to be essential to healing from historical and current trauma.

Keywords: American Indians, trauma-informed interventions, chronic illnesses

Compared to African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans, American Indians in the United States have the highest prevalence of chronic illnesses (CIs), such as heart disease (42%), diabetes (30%), and arthritis (53%),1 which contribute to the majority of premature deaths among this population.2 These negative health outcomes continue a legacy of adverse impacts of historical and current trauma stemming from colonialism.3–5 Examples of historical causes of trauma among Indigenous communities include genocide, loss of land, loss of languages, forced relocation, and boarding schools.3 Current sources of trauma include the establishment and maintenance of at-risk environments in which adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), structural racism, and individual-level racism are more likely to occur. A review of ACE studies among American Indians (AIs) provides evidence that historical and current trauma can substantially alter genes that are meant to regulate the stress response,6which may lead to greater susceptibility to chronic stress-induced physical and mental illness.

Overwhelming evidence shows chronic stress from trauma leads to behavioral health issues, impaired physical and mental health, and a shorter life span.7 However, neuroplasticity studies also demonstrate the potential for growth and healing from these traumas and also show great variability in response to trauma.8 In a phenomenological study by this research team of Apsáalooke (Crow) community member’s perceptions of the impacts of historical and current trauma, community members described links between trauma and health behaviors, resilience and strength, connection and isolation, language and language loss, cultural knowledge and practices, racism and discrimination, and grieving.9 Thus, linking historical trauma-induced stress with current trauma can demonstrate how health inequities develop and become entrenched in Indigenous communities.10

Trauma-informed care.

A trauma-informed intervention approach acknowledges and attends to trauma and its consequences. Trauma often leads to a cascade of negative impacts on physical and mental health, and health behaviors that in turn affects individuals’ ability to cope effectively; it can inhibit or destabilize healthy relationships, create insecurity, and incite feelings of powerlessness.11 For recovery from trauma to occur, individuals may need to (1) recognize and heal the wounds, (2) refrain from negative reinforcing coping patterns, (3) recognize and reinforce resilience, and (4) establish a sacred connection to life.12 Many trauma-informed intervention models use a multifaceted approach that incorporates an environment of safety, encouragement of healing relationships, and provision of tools to bolster self-management and coping; these tools equip survivors with a foundation on which to grow, heal, and build the steps to achieve future goals.13 Hobfoll and colleagues14 have identified five empirically supported principles that guide trauma-informed prevention and intervention programs; they are a sense of: 1) safety, 2) peace, 3) self- and collective-efficacy, 4) connectedness, and 5) hope.

Trauma-informed care emphasizes the role of resilience, or positive adaptation, over pathology and symptoms.15 In the context of CI self-management, resilient individuals have greater capacity to notice and understand the nuances of their illness, become more active in their care, and demonstrate greater mastery over emotional responses to CI-related stressors.16 For many AI communities, cultural resilience also may play a strong role in individuals’ ability to become better CI self-managers. For example, values and beliefs rooted in spirituality, respect for family, the natural environment, and cultural traditions may improve community members’ ability to manage a CI.

Trauma-informed CI self-management programs for Montana’s Indigenous peoples.

In Montana, AIs with CIs die 20 years earlier for those with nephritis, 14 years earlier for those with heart disease, 12 years earlier for those with cerebrovascular disease, and 11 years earlier for those with diabetes than their White counterparts,17 highlighting an urgent need to develop culturally consonant CI self-management programs. Yet, the capacity for self-management relies heavily on the assumption of normal stress regulation, which may be negatively influenced by historical and current trauma.6 Therefore, it is important for CI self-management programs for AIs to be developed using a culturally derived and trauma-informed approach. This type of approach addresses current and historical trauma and begins to heal the wounds sustained from these traumas in culturally prescribed ways.5

This project uses Indigenous research methods coupled with a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to affect long-term positive health outcomes in the community.9,18–23 These approaches use community strengths and recognize and rely on the community’s understanding of the causes of their health disadvantages and the community’s ideas for effective solutions. In this paper, we describe how the CI self-management program uses a trauma-informed approach and explain how Apsáalooke cultural strengths are an essential source of healing for the community.

Methods

Members of the Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation and Montana State University (MSU) faculty and students worked together to develop a CI self-management program that is consonant with the Apsáalooke culture. Our partnership comprises an Apsáalooke Nation non-profit organization called Messengers for Health, which includes a Board of Directors that also serves as a community advisory board (CAB) for our CBPR work, and Indigenous and non-Indigenous faculty and students from MSU.9 We received primary institutional review board (IRB) approval for the interviews used to develop the program from Little Big Horn Tribal College (Apsáalooke tribal college) and secondary approval from the MSU IRB.

Community stories.

To understand the experience of managing a CI better, the Executive Director of Messengers for Health and third author of this paper interviewed 20 community members who had a variety of CIs. Participants were asked to share about their health from the time they were young up until the present time. Additional open-ended questions explored participants’ experiences with historical and current trauma, its impact on managing their CI, and their thoughts on what should be done to help community members with CIs. We developed a culturally consonant data analysis method that focused on team members listening to the interviews together and discussing “what touched our heart” (see Hallet and colleagues24 for more details). Ideas for a culturally consonant and relevant intervention emerged from the data analysis and informed our creation of an intervention that was trauma-informed in both approach (curriculum delivery) and content (curriculum design).

Intervention approach.

Our CI self-management intervention is called Báa nnilah, an Apsáalooke term which translates to “advice that is received from others.” Báa nnilah involves respect, nurturing, guidance, and love; it is a strong cultural expression of how wisdom is passed from generation to generation. Community members’ stories generated the idea for a group intervention that allows community members to learn through advice given by each other and by trusted community members who have been successful at managing their own CI (Aakbaabaaniilea [the ones who give advice], or mentors). Advice is often shared through story and is a positive way to provide guidance for life. This guidance is viewed as a demonstration of love and community care and is often shared in the Apsáalooke language. The words received are sacred and it is an honor to receive and follow the advice because doing so honors both the storyteller and the tradition. Having Aakbaabaaniilea facilitate group meetings (called gatherings) of 10 community members uses Apsáalooke cultural strengths and values of close kinship ties, visiting, and sharing.25,26 It is also in direct contrast to hierarchical learning contexts in which outside experts disseminate facts and knowledge to community members, which not only perpetuates colonizing behaviors, but also the trauma associated with them.

Báa nnilah draws on Apsáalooke cultural strengths, values, and traditions to help participants learn from each other. Each of the gatherings are implemented in the same format, beginning with a prayer or spiritual blessing, as spirituality is a key Apsáalooke cultural value that nurtures resilience. Opening in this way helps to construct a space in which participants feel safe speaking. Each gathering incorporates a traditional story, which often involves Old Man Coyote, and provides a portal through which the gathering topic is illustrated. Many trauma-informed interventions stress the importance of a safe and comfortable setting, and sharing traditional stories naturally infuses humor, which eases difficulty and pain and conveys a moral message that speaks to overcoming adversity. This environment establishes a strong connection with the health message being conveyed and allows participants to better absorb the information. Gatherings also include sharing circles, where participants voice tips and stories of their personal experiences regarding the gathering topic. They discuss how they interpret or what they received from the story in relation to their health. The program also incorporates supportive partnerships (dyads or triads of program participants who provide encouragement and support during and outside the program gatherings). These unique elements are in stark contrast to the approach of other CI self-management programs that rely on assumptions of health and disease from mainstream culture27–29 and have been shown to be inconsonant with, and difficult to sustain within, AI communities.30,31

Trauma-informed intervention content.

Since all interviewees shared examples of how trauma and loss negatively affected their CI self-management, it was clear that addressing trauma and loss would be a foundational component of their path towards better health and well-being. Due to the salience and frequency of this topic in the interviews, we decided to not only integrate elements of a trauma-informed intervention throughout the curriculum, but to also dedicate an entire gathering to this issue. Although the complete intervention includes seven gatherings, our results section focuses on the first three gatherings, which have the most trauma-informed content. Next, we describe how we integrated ideas from participants’ experiences into our trauma-informed intervention.

Results

The first three gatherings are described below. There are specific objectives tied to each gathering (see Table 1). Each gathering uses Apsáalooke strengths and values to address historical and cultural trauma and teach participants effective ways for managing their CIs.

Table 1.

Trauma-Informed Gathering Objectives

| Gathering Title | Gathering Objectives |

|---|---|

| Gathering 1: Beginning the Báa nnilah Journey | Share the values of the program |

| Understand the importance of confidentiality | |

| Experience an atmosphere of safety, social connection, comfort, hopefulness, feeling open to sharing, and receiving and giving support | |

| Gathering 2: Ongoing Conditions and Self-Care | Define what an ongoing health condition is |

| Describe what self-care is and discuss why it is important | |

| Become aware of how to access information and resources | |

| Discuss personal self-care | |

| Develop personal goals for improved self-care | |

| Gathering 3: Dasssachchuchik (Strong Heart) | Discuss grief and loss and its relationship to historical and current trauma |

| Describe the stages of change to overcome denial through humility | |

| Describe and discuss Apsáalooke cultural values and resilience and how it positively impacts mental health | |

| Recognize hope as a powerful foundation for healing and wellness | |

| Illustrate what historical trauma and resilience looks like in your own personal lives, family, and community | |

| Identify simple exercises and how to use them to deal with stress, pain, and fatigue |

Gathering 1: Beginning the Báa nnilah journey.

In the first program gathering, the Aakbaabaaniilea discuss how the gatherings will be a place of healing, resilience, connection, hopefulness, and safety. They share the importance of cultural strengths and values relating to the clan system (Ashamaliaxxia) and how advice (Báa nnilah), language (Biiluukeiilia), optimism (Baahpe xaxxua ituuk - “Every day is a good day” and Itchick dii awa kuum - “Good to see you”), and having a strong heart (Daasachchuchik) are integral to overcoming the pain and grief associated with historical and current trauma. Itchick dii awa kuum is a greeting that goes well beyond a “hi” and “goodbye” since it opens the door for a deeper conversation, which may lead to a greater sense of care and well-being. To convey information in a more meaningful manner, Aakbaabaaniilea often incorporate the use of the Apsáalooke language. Apsáalooke is a Siouan language. Most of the tribal members who worked to create the intervention are fluent speakers and those who are not comfortable in their level of speaking, have a passable knowledge of the language and are able to listen and understand what they hear. It is primarily an oral language and not all community members speak it, yet due to the importance of the language in sustaining the cultural perspective on health and wellbeing, it is used in the title of the intervention and in appropriate ways in the intervention content.

One of the most important features of this first gathering is the creation of a safe place to talk about personal struggles. Consequently, elements of safety, respect, kindness, openness, honesty, sincerity, trust, sharing, acceptance, tolerance, sensitivity, humor, resilience, and healing are discussed as core Apsáalooke values and strengths that are central to all aspects of the intervention approach and content domains (see Table 2). During this gathering, all participants and mentors sign a confidentiality agreement stating that they will refrain from sharing any personal information discussed in the gatherings in order to create a foundation for safety and healing.

Table 2.

Apsáalooke Cultural Strengths and Values

| Cultural Strengths and Values | Description |

|---|---|

| Clan System (Ashamaliaxxia) | The Apsáalooke matrilineal clan system is based on close kinship and shows by knowing your clan relatives and having compassion, empathy, and respect for them. Program mentors will select members of their program groups based on the clan system. |

| Advice (Báa nnilah) | This is advice that we receive from others, particularly from elders, which is often shared through story and gives us instructions for life. If one listens and applies this advice, it will keep us on the right path and will help us avoid making mistakes. |

| Language (Biiluukeiilia) | Apsáalooke deliik is the Apsáalooke lanugage. It is used in the program name and in appropriate ways in the program meetings. |

| Optimism (Baahpe xaxxua ituuk) | The belief that everyday is a good day and that life is more valuable than anything else, entails having a positive approach to life. |

| Good to See You (Itchick dii awa kuum) | When individuals see each other, it is never a quick ‘hi’ and ‘goodbye.’ This reflects the importance of spending quality time with others, of real listening and exchange, and understanding that others are special and what they share is important. It makes both people feel good. |

| Strong Heart (Daasachchuchik) | Having a strong heart gives us the desire and willingness to persevere in a positive way despite obstacles. Some use the word resilience to describe this. |

To help participants cope with stress or trauma within the gatherings and in everyday life, we provide information about the window of tolerance, which is the place where we are emotionally regulated. Participants are then guided through an exercise titled Ground Breathe Settle, which was inspired by Dr. Ruby Gibson of Freedom Lodge.32 To help remind participants of the practice in every-day life, they also receive a bracelet inscribed with a Crow design and the words, Ground Breathe Settle.

Gathering 2: Ongoing conditions and self-care.

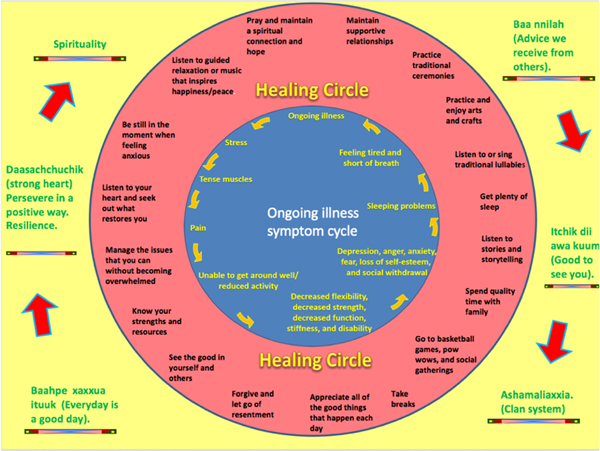

During the second gathering, time is spent talking about ongoing health conditions, how to manage them through self-care, and how to access information and resources regarding CIs. Although a lot of information is provided regarding a variety of CIs, the trauma-informed features of this gathering are an important focus of discussion. A common component of CI self-management education is a CI symptom cycle that includes such things as pain, depression, or sleeping problems that may occur among people living with CIs and that can exacerbate each other. During an early program development meeting, when looking at examples of symptom cycles, one of the Aakbaabaaniilea shared that it would be good for us to overlay the symptom cycle with a healing circle to help participants feel hope and give them practices for breaking out of the symptom cycle. We identified 18 healing circle practices, many that arose from the initial qualitative interviews specific to the Apsáalooke culture (see Figure 1). These practices may increase hope and one’s capacity to move through the cycle of grief, loss and forgiveness. Examples include listening to or singing traditional lullabies, listening to stories and storytelling, spending quality time with family, attending basketball games, pow wows and other social gatherings, practicing traditional ceremonies, practicing and enjoying arts and crafts such as beading, praying and maintaining a spiritual connection. Several other practices came from the book Just one thing, by Dr. Rick Hanson,33 a consultant to our program. The book describes how a simple reflective practice can work eventually to strengthen neural pathways that lead to increased positive feelings of joy, love, and wisdom.

Figure 1.

Healing Circle

During this gathering, each participant is provided with a color copy of the Healing Circle (Figure 1) that they can hang in a prominent place in their home. The program manual includes culturally relevant and appropriate descriptions for each practice. Participants receive a beautifully illustrated Ishdiannee Itchish (Walking a Good Path) handout that describes a practice to become more mindful and intentional about the positive experiences and elements in their lives. The idea for this handout arose from Dr. Rick Hanson’s practice ideas, and the Ishdiannee Itchish practice is completed during Gathering 2. The program manual includes a handout with practical ways to help oneself relax and become calm—all of which relate back to the healing circle.

Gathering 3: Daasachchuchik (strong heart).

Daasachchuchik illustrates perseverance through hardship, which can promote post-traumatic growth. In other words, Daasacchuchik indicates your heart grows stronger as you live in resilience. During this gathering, participants are provided a traditional story about the Old Man Coyote in which he kills a monster that is destroying everything in sight. The story illustrates the importance of killing symbolic monsters (such as violence, shame, and substance abuse) to confront and deal with unresolved issues in a healthy manner and break from unhealthy cycles. Aakbaabaaniilea discuss the importance of having a strong heart and being resilient when overcoming these challenges. Participants are then provided handouts with examples of grief and loss, how to move through them on their healing journey, and how hope can be a powerful medicine along the way. After reflecting on the Old Man Coyote story, participants are encouraged to share their own personal story of loss, trauma, and strength or what they learned from the Old Man Coyote story with the group.

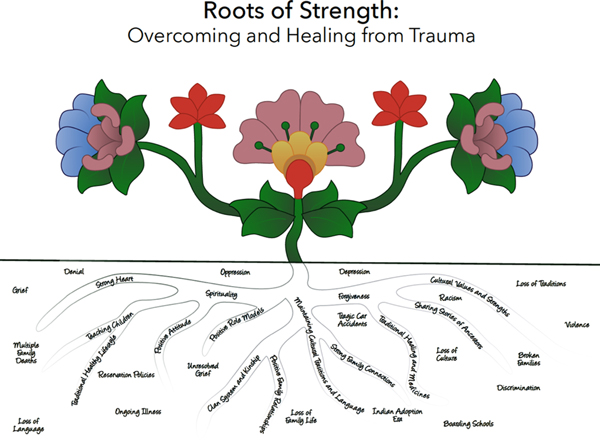

Participants are then invited to work with their supportive partner to complete a Roots of Strength diagram (see Figure 2). This diagram is based on a traditional beaded Crow flower design, and participants identify the roots of their flower’s strength and beauty (such as cultural values, strong family connections, strong heart, spirituality, forgiveness, positive attitude, and role models) as well as challenges they have encountered in their flower’s toxic soil (such as loss of language, culture, and traditions, boarding schools, and discrimination). The roots represent the foundation of Apsáalooke cultural strengths, which are passed down from generation to generation. Participants are provided with a blank flower design; the intention of the exercise is to help them identify their personal challenges, strengths, and resources so that they can heal and flourish in a resilient manner.

Figure 2.

Roots of Strength

Participants are provided a handout entitled The Healing Journey, depicting stages on the journey from loss to healing via an eagle image. This diagram was adapted from Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ work.34 An accompanying section in the program manual describes each stage with examples of what individuals may be feeling and saying while going through the journey (see Appendix Figure). The gathering closes with a spiritual burning ceremony where participants are asked to reflect on what they have learned and write on a small piece of paper an event or moment of loss and grief that they want to release from their life. Participants put their papers in a metal bowl, go outside, stand in a circle, and burn the papers. Mentors are encouraged to modify this activity as appropriate to their group and may include burning sage or sweetgrass as well. The ceremony is concluded with a closing prayer provided by an elder of the group.

Discussion

We described a trauma-informed and cultural strengths-based approach for developing and implementing Báa nnilah, a CI self-management program, designed for Apsáalooke tribal members to validate the continuing impact of historical and current trauma on their physical and mental health and to learn skills for improving their CI self-management. Trauma-informed content is infused throughout three of the program’s gatherings and is the focus of the gathering titled Daasachchuchik, which emphasizes cultural strengths and resilience around one’s own self-care and support for others. The program is built on Apsáalooke cultural strengths and values such as advice-giving and spending quality time with each other. The program atmosphere was designed to promote a sense of safety, instill hope, strengthen connectedness, and support collective efficacy—all essential elements of evidence-based trauma-informed interventions.14 Program materials validate participants’ experiences with historical and current trauma and tap into cultural and personal strengths to overcome the loss and grief associated with trauma.

As with other trauma-informed programs, a sense of trust must be developed for community members to gain confidence in and truly benefit from this program.15,35 Developing trusting relationships allows participants to feel more comfortable in discussing their experiences and provides more open communication.35 Developing the trust of community members is also a fundamental component to the sustainability of health programs.36 It is important that this CI self-management intervention was not seen as a quick “hi” and “goodbye” for the community, as other culturally inconsonant self-care programs may have been viewed by or practiced in the community. Báa nnilah is rooted in the community through cultural strengths such as Daasachchuchik (resilience), is led by a local Indigenous non-profit organization and facilitated by community members, which increases trust that the program is not a fleeting “fix.” In this way, we encourage better health within the community, which is rooted in the strong hearts of its members, healing the rupture in community and community support affected by historical and on-going structural and cultural trauma.

It is worth noting that our approach departs from standard CI self-management programs’ standards37 in two ways: 1) the incorporation of trauma-informed content, and 2) the use of advice from others. A sacred bridge to wellness is built upon supportive relationships that foster a sense of security where trust can be renewed, which in turn fosters coping with and healing from the impacts of trauma. Nurturing healing occurs through an establishment of support systems that strengthen a connection to a healing community that provides care and acceptance, and encourages resilience by including the exploration of the trauma while highlighting how this traumatic history helped the survivor(s) to develop strengths and resources.12,13

Overall, the Báa nnilah program approach adheres to key principles of trauma-informed interventions.15 For maximal effectiveness, trauma-informed interventions should address the trauma’s impact, emphasize strengths and resilience, be culturally consonant, involve input from community members, create a safe and respectful environment, and focus on the process of recovery. Regarding CI self-management, strengthening resilience increases one’s ability to take action towards daily care of one’s illness and gaining mastery in overcoming challenges effectively.16 The program employs a group intervention method that highlights key features for addressing traumas through sharing and validating participant experiences.38

The approach we describe has implications for informing implementation science in the context of tribal communities’ development of effective CI and other health-related interventions. First, it describes foundational principles of health programming: community engagement and cultural-centeredness.39 The Báa nnilah program emerged directly as a result of the long-standing and trusting partnership between the Apsáalooke people and MSU to address the health needs of its tribal members. The result is a community-based CI program that relies on cultural strengths and values to guide program content and delivery. Our approach also matches what is referred to as “integrated knowledge translation (p. 5),”39 in which the intervention and resulting knowledge transfer is co-designed and co-implemented with Western science and Indigenous research methods, thereby valuing both Western and Indigenous ways of knowing.

One limitation of this project is that intervention content was informed from 20 interviews with community members; some other perspectives may have been captured had we conducted more interviews. Additionally, interviews were limited to adults aged 26 and older and, therefore, did not capture the perspectives of youth with a CI. We believe that our approach has several strengths. First, program materials were co-developed by community and university partners, including Indigenous students. This allowed us to draw important information and strategies from academic science and traditional knowledge and practices. Second, due to prior work and development, the partnership had sufficient time to discuss, plan, and develop the program prior to implementing it. Team members understood and agreed that it would take time to discuss the development of program content and delivery method. Third, the program was implemented by community members who themselves were well versed in their own CI self-management.

Understanding wellness through a holistic perspective is an important concept in structuring programs to improve health among Indigenous communities. Health promotion programs within Indigenous communities work best when physical, emotional, and spiritual aspects of self are acknowledged and integrated.40 Since culturally rooted health values and behaviors have largely been ignored by past health improvement approaches due to the exclusion of Indigenous communities in the decision-making process,41 poor health persists. Without Indigenous perspectives on health and wellbeing and their input, health care programs and systems are perceived as imposing and intrusive. In Indigenous communities, it is essential to promote and activate traditional customs and preserve traditional language that fosters good holistic health. The symbolism of the circle regarding health and spirituality, which is found among many Indigenous cultures, may provide a direction for health support and improvement within these communities.41 The Báa nnilah program communicates a circle of healing within the Apsáalooke community wherein hope is infinite.

In conclusion, continuing efforts to improve the health and well-being of Apsáalooke people has been at the heart of the Apsáalooke – MSU partnership. This partnership is based on principles of CBPR and Indigenous research methods with the goal to create sustainable culturally-relevant and impactful health interventions. For CI self-management programs to be truly effective in Indigenous communities, they should be adapted in a way that is both trauma-informed and uses cultural strengths-based content and delivery methods that are consonant with each unique tribal community.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Mark Schure, Assistant Professor of Community Health at Montana State University..

Sarah Allen, Assistant Professor of Family Life and Human Development at Southern Utah University..

Coleen Trottier, student at Montana State University..

Alma McCormick, Executive Director of Messengers for Health, a non-profit health organization..

Lucille Other Medicine, program officer for Messengers for Health, a non-profit health organization..

Dorothy Castille, Health Scientist Administrator at the National Institutes of Health..

Suzanne Held, Professor of Community Health at Montana State University..

References

- 1.Gallant MP, Spitze G, Grove JG. Chronic illness self-care and the family lives of older adults: A synthetic review across four ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2010;25(1):21–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. Leading Causes of Death. Hyatsville, MD: National Center for Heatlh Statistics;2017. Retrieved June 24, 2019 from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brave Heart MY, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian Holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. Am Indian Alaska Nat. 1998;8(2):56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brave Heart MYH. The historical trauma response among natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duran E, Duran B, Heart MYHB, Horse-Davis SY. Healing the American Indian soul wound In: Danieli Y, ed. International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. New York, NY: Plenum; 1998:341–354. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brockie TN, Heinzelmann M, Gill J. A framework to examine the role of epigenetics in health disparities among Native Americans. Nurs Res Pract. 2013;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychological Association. Stress in America: Paying with our Health. Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doidge N The brain’s way of healing: Remarkable discoveries and recoveries from the frontiers of neuroplasticity. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Real Bird S, Held S, McCormick A, Hallett J, Martin C, Trottier C. The Impact of Historical and Current Loss on Chronic Illness: Perceptions of Crow (Apsáalooke) People. Int J Indig Health. 2016;11(1):198–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walters KL, Mohammed SA, Evans-Campbell T, Beltrán RE, Chae DH, Duran B. Bodies don’t just tell stories, they tell histories: Embodiment of historical trauma among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Du Bois Review: Soc Sci Res Race. 2011;8(1):179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raja S, Hasnain M, Hoersch M, Gove-Yin S, Rajagopalan C. Trauma Informed Care in Medicine. Fam Community Health. 2015;38(3):216–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller D Addictions and trauma recovery: An integrated approach. Psychiat Quart. 2002;73(2):157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bath H The three pillars of trauma-informed care. Reclaim Child Youth. 2008;17(3):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hobfoll SE, Watson P, Bell CC, et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid–term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiat: Interperson Biol Process. 2007;70(4):283–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott DE, Bjelajac P, Fallot RD, Markoff LS, Reed BG. Trauma‐informed or trauma‐denied: Principles and implementation of trauma‐informed services for women. J Community Psychol. 2005;33(4):461–477. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franczak M, Barshter D, Reich JW, Kent M, Zautra AJ. Enhancing resilience and sustaining recovery In: Singh NN, Barber JW, Van Sant S, eds. Handbook of Recovery in Inpatient Psychiatry. Switzerland: Springer; 2016:409–438. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. Montana Vital Statistics 2016. Helena, MT: Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stillwater B Living Well Alaska In. Alaska Section of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Chronicle. Vol 1 www.hss.state.ak.us/dph/chronic/: Alaska Division of Public Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Ingram BL, Swendeman D, Lee A. Adoption of self-management interventions for prevention and care. Primary Care: Clin Office Practice. 2012;39(4):649–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duran E, Firehammer J. Story sciencing and analyzing the silent narrative between words: Counseling research from an indigenous perspective In: Decolonizing “multicultural” counseling through social justice. New York, NY: Springer; 2015:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battiste M Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson S Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallett J, Held S, McCormick AKHG, et al. What touched your heart? Collaborative story analysis emerging from an Apsáalooke cultural context. Qual Health Res. 2016:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roripaugh R (1994). From the Heart of the Crow Country: The Crow Indians’ Own Stories by Joseph Medicine Crow. Western American Literature, 29(1), 94–94. doi: 10.1353/wal.1994.0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauerle P (2003). The way of the warrior: Stories of the Crow people. University of Nebraska Press: Nebraska, OK. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartlett JG, Iwasaki Y, Gottlieb B, Hall D, Mannell R. Framework for Aboriginal-guided decolonizing research involving Metis and First Nations persons with diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(11):2371–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duran BM. The promise of health equity: Advancing the discussion to eliminate disparities in the 21st century. Paper presented at: 32nd Annual Minority Health Conference 2011; Chapel Hill, NC. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donatuto J, Satterfield T, Gregory R. Poisoning the body to nourish the soul: Prioritising health risks and impacts in a Native American community. Health, Risk & Society. 2011;13(2):103–127. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jernigan V Community-Based Participatory Research with Native American Communities: The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. Health Promot Practice. 2010;11:888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narayan K, Hoskin M, Kozak D, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Lifestyle Interventions in Pima Indians: a Pilot Study. Diabetic Medicine. 1998;15:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson R My body, my earth: The practice of somatic archaeology. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanson R Just one thing: Developing a buddha brain one simple practice at a time. Oakland, CA: New Harbor Publication, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kübler-Ross E On death and dying. New York, NJ: Macmillan Co; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reeves E A synthesis of the literature on trauma-informed care. Issues Ment Health N. 2015;36(9):698–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hacker K, Tendulkar SA, Rideout C, et al. Community capacity building and sustainability: outcomes of community-based participatory research. Prog Comm Hlth Partn. 2012;6(3):349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorig K, Holman H, Sobel D. Living a healthy life with chronic conditions: self-management of heart disease, arthritis, diabetes, depression, asthma, bronchitis, emphysema and other physical and mental health conditions. Third ed Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing Company; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foy DW, Unger WS, Wattenberg MS. Group interventions for treatment of psychological trauma: An overview of evidence-based group approaches to trauma with adults. American Group Psychotherapy Association;2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oetzel J, Scott N, Hudson M, et al. Implementation framework for chronic disease intervention effectiveness in Māori and other indigenous communities. Globalization Health. 2017;13(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westerman T Guest Editorial: Engagement of Indigenous clients in mental health services: What role do cultural differences play? Adv Ment Health. 2004;3(3):88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross J, Ross J. Keep the circle strong: Native health promotion. J Speech Lang Path Audio. 1992;16(4):291–302. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.