Abstract

Background

The first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in a drastic reduction in kidney transplantation and a profound change in transplant care in France. It is critical for kidney transplant centers to understand the behaviors, concerns and wishes of transplant recipients and waiting list candidates.

Methods

French kidney patients were contacted to answer an online electronic survey at the end of the lockdown.

Results

At the end of the first wave of the pandemic in France (11 May 2020), 2112 kidney transplant recipients and 487 candidates answered the survey. More candidates than recipients left their home during the lockdown, mainly for health care (80.1% vs. 69.4%; P < 0.001). More candidates than recipients reported being exposed to Covid-19 patients (2.7% vs. 1.2%; P = 0.006). Many recipients and even more candidates felt inadequately informed by their transplant center during the pandemic (19.6% vs. 54%; P < 0.001). Among candidates, 71.1% preferred to undergo transplant as soon as possible, 19.5% preferred to wait until Covid-19 had left their community, and 9.4% were not sure what to do.

Conclusions

During the Covid-19 pandemic in France, the majority of candidates wished to receive a transplant as soon as possible without waiting until Covid-19 had left their community. Communication between kidney transplant centers and patients must be improved to better understand and serve patients’ needs.

Keywords: Candidates, Covid-19, Kidney, Patients, Transplantation

1. Introduction

In 2020, a novel coronavirus, designated SARS-CoV-2, caused an international outbreak of a viral illness predominantly affecting the respiratory system, termed Covid-19. In France, to limit the spread of the virus and control the first wave of this pandemic, a nationwide lockdown was implemented from March 17 2020 until May 11 2020. At that time, it had been reported that, amongst a total of 43327 kidney transplant recipients, and 17112 candidates for kidney transplantation, 532 (1.2%) recipients and 112 (0.7%) candidates had been diagnosed with a confirmed Covid-19 infection (11 May 2020, https://www.agence-biomedecine.fr).

Given the high rate of morbidity and mortality observed in transplanted patients [1], [2], [3], [4], [5] and to avoid saturation of intensive care units with recent transplant recipients [6], the Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in a drastic reduction in transplant activities in the United States and France [7], [8]. In France, kidney transplantation was even suspended during the lockdown. In the UK, it has been estimated that during a 3-month period of Covid-19-related restrictions, up to 722 kidney transplantations were not performed [9].

Not only has access to transplantation been limited, but in order to shield patients from exposure in healthcare environments, clinics have transitioned to videoconference and telephone delivery of pre- and post-transplant care [10], [11]. Further, many transplant societies (including the Francophone Society of Transplantation on the 11 March 2020) recommended not leaving home, favoring teleworking, physical distancing, and the systematic use of mask and hand sanitizers. However, despite these practice changes and published guidelines, it is unclear what was the perception of the transplant recipients or candidates regarding this information and whether or not they had the necessary tools to comply with precautions for avoiding Covid-19.

During the first wave of the pandemic, transplant centers have been tasked to make decisions on patients’ behalf regarding the safety of kidney transplantation. This decision incorporates health systems considerations, including forecasts of hospital bed availability, as well as risks of Covid-19 infection and mortality in individuals on immunosuppressive therapy. Importantly, the patient's perspectives are often conspicuously absent from these decisions, including whether transplantation remains a priority for them. Despite an explosion of publications on the novel coronavirus, the patient's voice has been scarce [12], [13].

In the present study we used a short survey to elicit and understand the behaviors, concerns, and priorities of kidney transplant recipients and waiting list candidates at the end of the first wave of the pandemic in France.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design

The COWAIT study (Evaluating the impact of COvid-19 on WAIting list and Transplant patients), launched on the initiative of The Francophone Society of Transplantation (SFT), was approved by the French Institutional Review Board CPP 1283 HPS3 and registered on ClinicalTrials (Identifier: NCT04376775). Briefly, at the end of the lock-down, from 11 May 2020 to 23 May 2020, French kidney candidates and recipients were contacted directly by the French patient association France Rein (www.francerein.org) or by transplant centers to answer an electronic survey.

2.2. Study Population

French adult patients registered and awaiting a kidney transplant or those transplanted with a functional kidney were approached to participate in this study.

2.3. Survey

The questionnaire was adapted from the original initially developed by members of the Duke University Group for Abdominal Transplant Outcomes Research (GATOR), which comprises nephrologists, transplant surgeons, hepatologists and researchers (Annexe 1). It was obtained by iterative consensus over a series of meetings. A pilot test was performed with a few patients. The 38-question survey was translated in French. Three questions were removed: two about race and origin in accordance with French law and one about primary health insurance provider since there is a single French primary health insurance. The survey was placed on a secured platform accessible via a web link, the latter of which was emailed directly to patients. This anonymous survey did not solicit any patient identifying information and answers were not linked to the patient's medical records. In light of this means of distribution, patterns of non-response were not quantifiable.

2.4. Definition of the viral risk zone in France

In France, regions which had both a high prevalence of Covid-19 (more than 10% of emergency service admission for a suspicion of Covid-19) and/or a saturation of intensive care units (more than 80% of the intensive care beds occupied by Covid-19 patients) were classified as a high viral risk zone. The others were defined as low viral risk zones.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Categorical data are presented as counts and percentages and compared with a chi-square test. The Bonferroni post-hoc correction was applied for multilevel categorical variables. Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations upon verification of their normal distribution with the Shapiro–Wilk test, and compared with a t-test. All analyses were conducted in the R environment (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and two-tailed P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patients description

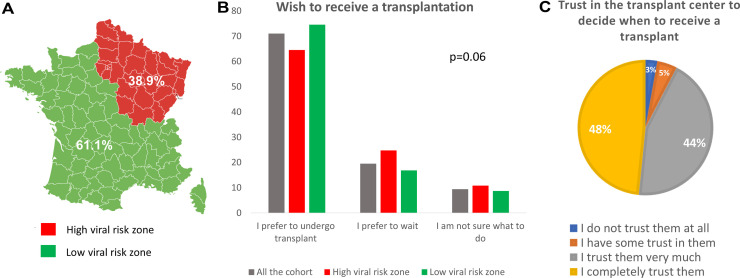

In France between May 11 2020 and May 23 2020, among the 43327 kidney transplant recipients and the 17112 waiting list candidates, 2112 recipients (4.9%) and 487 candidates (2.8%) answered the survey. The majority of respondents lived in a low-risk viral zone (n = 1589; 61.1%), however over a third of respondents were living in a high-risk viral zone (n = 1010; 38.9%) (Fig. 1A). The mean ages of the recipients and candidates were 55.1 and 56.5 years-old, respectively (Table 1 ). The majority were male and were married or living as married. Most had internet and TV at home.

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV2 circulating zones and distribution of patients who answered the survey. In France, regions which had both a high prevalence of Covid-19 and/or a saturation of intensive care units were classified as a high viral risk zone (Red). The others were defined as low viral risk zones (Green) (A). Among patients on the waiting list, the wish to receive a transplant is reported in all the cohort and according to the viral risk zone (B), as well as their trust in their transplant center to decide when to receive a transplant (C).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics..

| Kidney transplant recipients |

Waiting list candidates |

p | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2112 | n = 487 | |||

| Age (years), mean | 55.1 ± 13.2 | 56.5 ± 13.0 | 0.032 | 2594 |

| Male, n (%) | 1322 (62.6%) | 292 (60.0%) | 0.303 | 2599 |

| Familial situation, n (%) | 0.391 | 1155 | ||

| Single | 248 (26.7%) | 50 (22.1%) | ||

| Living as a couple | 470 (50.6%) | 126 (55.8%) | ||

| Divorced | 149 (16.0%) | 38 (16.8%) | ||

| Widowed | 62 (6.7%) | 12 (5.3%) | ||

| Education level, n (%) | 0.287 | 2599 | ||

| No diploma | 287 (13.6%) | 83 (17.0%) | ||

| Middle school diploma | 479 (22.7%) | 115 (23.6%) | ||

| High school graduate | 366 (17.3%) | 83 (17.0%) | ||

| College graduate (2 years) | 361 (17.1%) | 74 (15.2%) | ||

| College graduate (> 2 years) | 619 (29.3%) | 132 (27.1%) | ||

| No. people at home, mean | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 0.439 | 2595 |

| Internet at home, n (%) | 2029 (96.1%) | 461 (94.7%) | 0.203 | 2599 |

| TV at home, n (%) | 1969 (93.2%) | 446 (91.6%) | 0.238 | 2599 |

| Smartphone, n (%) | 1795 (85.0%) | 403 (82.8%) | 0.245 | 2599 |

| Tablet, n (%) | 1145 (54.2%) | 257 (52.8%) | 0.600 | 2599 |

| Computer, n (%) | 1826 (86.5%) | 396 (81.3%) | 0.005 | 2599 |

| Time on the waiting list, n (%) | 487 | |||

| Less than 1 year | 158 (32.4%) | |||

| Between 1 and 2 years | 133 (27.3%) | |||

| Between 2 and 3 years | 79 (16.2%) | |||

| Between 3 and 4 years | 49 (10.1%) | |||

| Between 4 and 5 years | 25 (5.1%) | |||

| More than 5 years | 43 (8.8%) |

3.2. Precautions for avoiding Covid-19

69.4% of recipients and 80.1% of candidates left their home during the lockdown (P < 0.001), and among them, 48.2% and 76.9% did so more than once a week, respectively (P < 0.001) (Table 2 ). No differences were observed between the high and low risk zones (data not shown). The main reasons for leaving the home were for health care (recipients: 59.2% vs. candidates: 76.2%; P < 0.001), to buy groceries (recipients: 48.5% vs. candidates: 54%; P = 0.03), and to exercise (recipients: 26% vs. candidates: 21.1%; P = 0.03). Only 11.4% of patients below 55 years-old left home for work. Finally, around 90% of patients had access to hand sanitizer and masks.

Table 2.

Precautions to prevent COVID-19.

| Kidney transplant recipients |

Waiting list candidates |

p | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2112 | n = 487 | |||

| Leaving home during the epidemic | ||||

| Did you need to get out (yes)? n (%) | 1465 (69.4%) | 390 (80.1%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Leaving frequency, n (%) | < 0.001 | 1855 | ||

| 1–2 times per day | 389 (26.6%) | 108 (27.7%) | ||

| 2–3 times per week | 317 (21.6%) | 192 (49.2%) | < 0.001 | |

| Once a week | 402 (27.4%) | 55 (14.1%) | < 0.001 | |

| Twice a month | 205 (14.0%) | 21 (5.4%) | < 0.001 | |

| Once a month | 152 (10.4%) | 14 (3.6%) | < 0.001 | |

| To buy groceries, n (%) | 1025 (48.5%) | 263 (54.0%) | 0.033 | 2599 |

| To work, n (%) | 165 (7.8%) | 43 (8.8%) | 0.514 | 2599 |

| To practice sport, n (%) | 550 (26.0%) | 103 (21.1%) | 0.029 | 2599 |

| For religious services, n (%) | 21 (1.0%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0.601 | 2599 |

| For health care, n (%) | 1251 (59.2%) | 371 (76.2%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Did people living with need to get out (yes)? n (%) | 943 (44.6%) | 152 (31.2%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Home assistance and protective items | ||||

| Do you receive home assistance (yes)? n (%) | 137 (6.5%) | 43 (8.8%) | 0.082 | 2599 |

| Hand sanitizer, n (%) | 1880 (89.0%) | 448 (92.0%) | 0.064 | 2599 |

| Gloves, n (%) | 1305 (61.8%) | 334 (68.6%) | 0.006 | 2599 |

| Masks, n (%) | 1880 (89.0%) | 447 (91.8%) | 0.086 | 2599 |

3.3. Symptoms and diagnosis of Covid-19

The distribution of recipients and candidates was similar in the low and the high-risk zone (data not shown). Patients residing in low risk zones were less likely to having been exposed to someone with Covid-19 than those residing in high-risk zones (0.6% vs. 2.9%; P < 0.001). Reporting of Covid-19 related symptoms was similar between the low and high-risk zones (9% and 11.4%; P = 0.06). However, patients in the low-risk zones were less frequently tested for Covid-19 than those in the high-risk zones (6.1% vs. 11.7%, respectively; P < 0.001). Finally, among those who were tested, 11.3% of patients in the low-risk zones and 16.9% of patients in the high-risk patients were positive for Covid-19 (P = 0.3).

Recipients were less frequently exposed to someone with Covid-19 than candidates (1.2% vs. 2.7%; P = 0.006) (Table 3 ). Around 10% of recipients and candidates experienced symptoms compatible with Covid-19 (P = 0.1). However, recipients were less frequently tested for Covid-19 than candidates (7.2% vs. 12.9%, respectively; P < 0.001). Finally, among those who were tested, 15.1% of recipients and 12.7% of candidates were positive for Covid-19 (P = 0.8).

Table 3.

COVID-19 symptoms and diagnosis.

| Kidney transplant recipients |

Waiting list candidates |

p | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2112 | n = 487 | |||

| No symptom, n (%) | 1893 (89.6%) | 448 (92.0%) | 0.137 | 2599 |

| Fever, n (%) | 49 (2.3%) | 11 (2.3%) | 1.000 | 2599 |

| Cough, n (%) | 50 (2.4%) | 8 (1.6%) | 0.420 | 2599 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 72 (3.4%) | 12 (2.5%) | 0.357 | 2599 |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 120 (5.7%) | 28 (5.7%) | 1.000 | 2599 |

| Anosmia, n (%) | 16 (0.8%) | 5 (1.0%) | 0.573 | 2599 |

| Have you been in contact with a COVID+ patient? n (%) | < 0.001 | 2599 | ||

| I don’t know | 692 (32.8%) | 122 (25.1%) | 0.006 | |

| No | 1395 (66.1%) | 352 (72.3%) | ||

| Yes | 25 (1.2%) | 13 (2.7%) | ||

| Have you been tested for COVID? n (%)? | 152 (7.2%) | 63 (12.9%) | <0.001 | 2599 |

| Was the test positive? n (%) | 23 (15.1%) | 8 (12.7%) | 0.803 | 215 |

3.4. Information and communication with transplant center about Covid-19

A significant number of patients did not receive any information regarding Covid-19 from their transplant center (recipients: 19.6% vs. candidates: 54.0%; P < 0.001) (Table 4 ). The main sources of information for recipients and candidates were television (81.1% and 82.3%; P = 0.6), the internet (66.9% and 61%; P = 0.01), transplant centers (41.9% and 12.1%; P < 0.001), and their primary care doctor (32.6% vs. 56.1%; P < 0.001). Recipients were more likely to be informed by the transplant center whereas candidates were more often informed by their primary care doctor.

Table 4.

Patients information and communication with the transplant center about COVID-19.

| Kidney transplant recipients |

Waiting list candidates |

p | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2112 | n = 487 | |||

| Did you receive information from your transplant center about specific COVID-19 risks? | ||||

| I received, n (%) | < 0.001 | 2599 | ||

| No information | 415 (19.6%) | 263 (54.0%) | < 0.001 | |

| Few information | 552 (26.1%) | 120 (24.6%) | ||

| A lot of information | 308 (14.6%) | 35 (7.2%) | < 0.001 | |

| A complete information | 837 (39.6%) | 69 (14.2%) | < 0.001 | |

| What are your sources of information about COVID-19? | ||||

| Friends/Family, n (%) | 587 (27.8%) | 139 (28.5%) | 0.783 | 2599 |

| Pharmacist, n (%) | 342 (16.2%) | 89 (18.3%) | 0.296 | 2599 |

| Primary care doctor, n (%) | 689 (32.6%) | 273 (56.1%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Transplant center, n (%) | 885 (41.9%) | 59 (12.1%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Newspapers, n (%) | 462 (21.9%) | 131 (26.9%) | 0.020 | 2599 |

| TV, n (%) | 1712 (81.1%) | 401 (82.3%) | 0.556 | 2599 |

| Social networks, n (%) | 693 (32.8%) | 167 (34.3%) | 0.567 | 2599 |

| Internet, n (%) | 1413 (66.9%) | 297 (61.0%) | 0.015 | 2599 |

| Patients associations, n (%) | 285 (13.5%) | 44 (9.0%) | 0.010 | 2599 |

| Communication with the transplant center | ||||

| Do you communicate with your transplant center? (Yes, %) | 1288 (60.9%) | 126 (25.9%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| How do you communicate with your transplant center? | ||||

| Videoconference, n (%) | 310 (14.7%) | 18 (3.7%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Phone, n (%) | 865 (41.0%) | 74 (15.2%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Emails, n (%) | 740 (35.0%) | 47 (9.7%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Outpatient visits, n (%) | 205 (9.7%) | 29 (6.0%) | 0.012 | 2599 |

| Mail, n (%) | 71 (3.4%) | 8 (1.6%) | 0.065 | 2599 |

| Feelings about expressing concerns about COVID-19 and transplantation | ||||

| To express my concerns I feel, n (%) | 0.003 | 2599 | ||

| Not at all comfortable | 205 (9.7%) | 60 (12.3%) | ||

| Somewhat comfortable | 130 (6.2%) | 38 (7.8%) | ||

| Comfortable | 911 (43.1%) | 232 (47.6%) | ||

| Very comfortable | 866 (41.0%) | 157 (32.2%) | 0.003 |

More recipients were able to communicate with their transplant center than candidates (60.9% vs. 25.9%; P < 0.001). Phone and email were the two most commonly used tools by recipients and candidates, though they were more often used by recipients (41.0% vs.15.2%, P < 0.001, and 35% vs. 9.7%, P < 0.001, respectively). Few recipients and candidates reported communication with their transplant center through videoconference (14.7% and 3.7%, respectively), or outpatient visits (9.7% vs. 6%; P = 0.01). Most of the patients were comfortable expressing their concerns regarding Covid-19 to their transplant center (Table 4).

3.5. Patients concerns

Recipients more frequently thought that the Covid-19 pandemic could affect their ability to work (33% vs. 22.8%; P < 0.001), their ability to get medications (26.6% vs. 17.5%; P = 0.002), and their transportation to the hospital (24.4% vs. 17.7%; P = 0.002) than candidates (Table 5 ). Concern about the ability to work was highest among patients younger than 55 years (51.3% vs. 12.9%; P < 0.001). Those in high-risk vs. low-risk regions reported more concerns regarding the ability to buy food/necessities (19.7% vs. 15.9%; P = 0.01), obtain transportation to the hospital (28.6% vs. 19.6%; P < 0.001), and ability to work (34.3% vs. 29%; P = 0.006).

Table 5.

Concerns about COVID-19.

| Kidney transplant recipients |

Waiting list candidates |

p | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2112 | n = 487 | |||

| COVID-19 will negatively affect | ||||

| Afford my medications, n (%) | 69 (3.3%) | 18 (3.7%) | 0.738 | 2599 |

| Obtain my medications, n (%) | 562 (26.6%) | 85 (17.5%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Transportation to hospital, n (%) | 515 (24.4%) | 86 (17.7%) | 0.002 | 2599 |

| Buy food/necessities, n (%) | 376 (17.8%) | 76 (15.6%) | 0.277 | 2599 |

| Pay bills, n (%) | 254 (12.0%) | 55 (11.3%) | 0.709 | 2599 |

| Health insurance, n (%) | 122 (5.8%) | 20 (4.1%) | 0.177 | 2599 |

| Ability to work, n (%) | 696 (33.0%) | 111 (22.8%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| No concern, n (%) | 743 (35.2%) | 254 (52.2%) | < 0.001 | 2599 |

| Concerns about being infected by COVID-19 | ||||

| At home, n (%) | 0.009 | 2599 | ||

| Very concerned | 75 (3.6%) | 11 (2.3%) | ||

| Concerned | 201 (9.5%) | 39 (8.0%) | ||

| Little concerned | 714 (33.8%) | 138 (28.3%) | ||

| Not concerned | 1122 (53.1%) | 299 (61.4%) | 0.008 | |

| In the community, n (%) | < 0.001 | 2599 | ||

| Very concerned | 279 (13.2%) | 47 (9.7%) | ||

| Concerned | 690 (32.7%) | 125 (25.7%) | 0.021 | |

| Little concerned | 927 (43.9%) | 239 (49.1%) | ||

| Not concerned | 216 (10.2%) | 76 (15.6%) | 0.006 | |

| At the hospital, n (%) | < 0.001 | 2599 | ||

| Very concerned | 457 (21.6%) | 63 (12.9%) | < 0.001 | |

| Concerned | 685 (32.4%) | 122 (25.1%) | 0.012 | |

| Little concerned | 718 (34.0%) | 189 (38.8%) | ||

| Not concerned | 252 (11.9%) | 113 (23.2%) | < 0.001 |

The majority of transplant recipients and a large number of candidates reported being concerned or very concerned about being infected by Covid-19 in the hospital (54% vs. 38%; P < 0.001) (Table 4). Similarly, many recipients and candidates reported being concerned or very concerned about becoming infected in the community (45.9% vs. 35.4%; P < 0.001). By comparison, only 13.1% of recipients and 10.3% of candidates reported concerns with infection in their homes. Patients in the high-risk zone more often reported being concerned or very concerned about becoming infected than those of the low-risk zone (data not shown).

3.6. Waiting list candidates and wish to be transplanted

Among candidates, 71% preferred to undergo transplant as soon as possible, 19.5% preferred to wait until Covid-19 had left their community, and 9.4% were not sure what to do. The percentage of patients preferring to undergo transplant was higher in the low-risk zone vs. the high-risk zone, though this did not reach statistical significance (low: 74.5% vs. high: 64.5%; P = 0.06) (Fig. 1B). Similarly, there was no reported difference in those interested in proceeding with transplant by time on the waiting list (< 2 years: 68% vs. > 2 years: 75.5%; P = 0.06). Finally, 48% and 44% of candidates trusted their transplant center completely or very much for deciding when to receive a transplant, respectively (Fig. 1C).

4. Discussion

Kidney transplantation improves patient quality of live and survival by getting patients off dialysis [14], [15], but it could lead to increase the risk and susceptibility to Covid-19 [5]. While the second wave of the pandemic arrives in France and around the world, transplant physicians ignore what is the most appropriate replacement therapy for patients with end-stage renal disease. Therefore, a dialogue about risk-benefit, which respects the patient's perspective, and the concept of share decision-making, are of paramount importance.

In this study conducted in France, it was striking that a majority of surveyed patients wished to be transplanted despite the pandemic. This was true in both high-risk and low-risk areas, in those having been on the waiting list for more or less than 2 years, and despite more than 50% of patients reporting to be concerned or very concerned about Covid-19 transmission in the hospital. The high level of trust reported by patients towards their transplant center may help explain this finding. Importantly, the 30% of patients who preferred to defer transplantation may require a more intensive communication.

Of note, kidney transplant patients appeared to have better home confinement and less contact with Covid-19 patients. Further, many more candidates reported leaving their home for health care. This may be due to patients coming off dialysis following kidney transplantation, an important consideration given the risks of Covid-19 transmission in the in-center dialysis setting [16]. Although dialysis centers were reorganized to provide safe isolation areas for patients awaiting viral test results [17], up to 20% of dialysis patients developed Covid-19 in high prevalence areas with clustering in specific units [16].

Regarding communication between transplant centers and patients, it is notable that 27.4% of all patients and 54.4% of candidates reported having received no information about Covid-19 risks from their transplant center. This proportion may be in fact greater, as we were only able to reach those patients who had internet access. This highlights challenges to direct patient communication for transplant centers, as well as an urgent need to work with national organ procurement agencies to create national mailing lists and to collaborate with the transplant societies to disseminate patient recommendations quickly.

For wait-listed patients, the healthcare professional having provided the most information was their primary care doctor, and also likely their nephrologist. While transplant centers in France may be in regular and close communication with referring nephrologists in dialysis centers, the patients may not experience this communication directly. Given that transplant centers rely on being able to communicate with patients to inform them of an organ offer, more robust communication tools are important. In the UK, the Transplant Alert App has been developed to notify and communicate with patients regarding time sensitive organ offers, and it may be that such tools could be repurposed to facilitate improved real time communications with patients (https://www.mftapps.co.uk/support-TAA).

Examining care delivery during the lockdown, only 10% of kidney transplant recipients reported attending outpatient visits. This is consistent with the recommendations of transplant societies [11]. Surprisingly, in this population of internet connected patients, videoconference was used infrequently. Telephone was most often used for communicating with the transplant center. This is despite the fact that most transplant centers were equipped for this at the onset of the pandemic. It is unclear if this is due to patient or transplant center preference but is worth exploring to ascertain whether technology is matched appropriately with specific populations to maximize access to quality care.

Finally, the incidence of symptoms compatible with Covid-19 was 10% in both groups. However, recipients were less likely to be tested for Covid-19. A shortage of SARS Cov2 RT-PCR in France possibly explains why all symptomatic recipients were not tested. By comparison, in order to avoid the dissemination of Covid-19 in dialysis units, a systematic screening strategy was recommended in all dialysis patients suspected of Covid-19 [18]. This observation could lead to an underestimated incidence of Covid-19 in the transplant population in France, and serological studies could help to reappraise the epidemiology of this infection.

The main limitations of this study are the low response rate and use of a convenience sample of patients with internet access. These raise the potential for sampling bias potentially limiting external generalizability to those without internet access and with lower health literacy. Moreover, we did not ask whether transplant candidates were on dialysis or not. Finally, this survey was administered at the end of the lockdown period, when the pandemic severity was decreasing, which could have affected patient attitudes towards transplant. Nonetheless, our findings represent the views of over 2600 patients and could help to improve patients’ care during the second wave of the pandemic. This survey is currently used in the ICOT study (Impact of Covid On Transplant Candidates and Recipients) at the Duke University and it will be interesting to compare our findings.

5. Conclusion

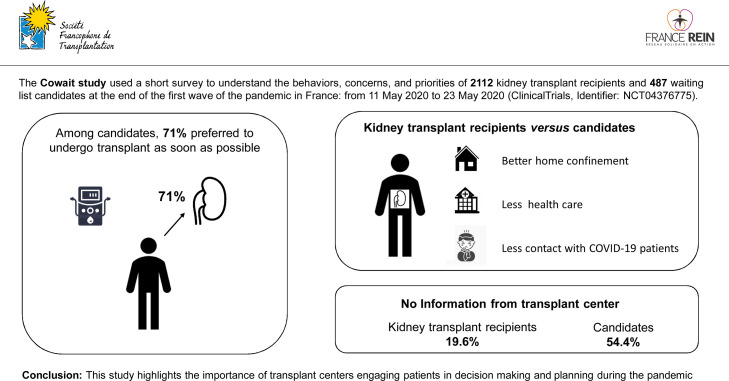

These data represent a large survey of transplant patients at the end of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, providing actionable insights into the patient experience to inform care. The majority of patients prioritized kidney transplant during the pandemic, despite reporting limited communication from their transplant center and significant concern for Covid-19 transmission in the hospital and community. Further, it highlights the need for reliable and accessible communication strategies between transplant centers and patients (Fig. 2 ). Given the ongoing challenges represented by Covid-19, these data underscore the importance of transplant centers engaging patients in decision making and planning during the pandemic.

Fig. 2.

Impact of Covid-19 on kidney transplant and waiting list patients: Lessons from the first wave of the pandemic.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient association France Rein which actively participated in the dissemination of the survey. We also acknowledge Céline Bairrais-Martin, Aurélie Desseix, Dr Karine Moreau, Cyril Millet, and Serge Leroy for their outstanding technical contribution to this study. This work has not required financial support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nephro.2020.12.004.

Online supplement. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Caillard S., Anglicheau D., Matignon M., Durrbach A., Greze C., Frimat L. An initial report from the French SOT Covid Registry suggests high mortality due to Covid-19 in recipients of kidney transplants. Kidney Int. 2020;98:1549–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The OpenSAFELY Collaborative. Williamson E., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K.J., Bacon S., Bates C. OpenSAFELY: factors associated with Covid-19-related hospital death in the linked electronic health records of 17 million adult NHS patients. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.06.20092999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akalin E., Azzi Y., Bartash R., Seethamraju H., Parides M., Hemmige V. Covid-19 and Kidney Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberici F., Delbarba E., Manenti C., Econimo L., Valerio F., Pola A. A single center observational study of the clinical characteristics and short-term outcome of 20 kidney transplant patients admitted for SARS-CoV2 pneumonia. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravanan R., Callaghan C.J., Mumford L., Ushiro Lumb I., Thorburn D., Casey J. SARS-CoV-2 infection and early mortality of wait-listed and solid organ transplant recipients in England: a national cohort study. Am J Transplant. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ajt.16247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelico R., Trapani S., Manzia T.M., Lombardini L., Tisone G., Cardillo M. The Covid-19 outbreak in Italy: Initial implications for organ transplantation programs. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1780–1784. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyarsky B.J., Po Yu Chiang T., Werbel W.A., Durand C.M., Avery R.K., Getsin S.N. Early impact of Covid-19 on transplant center practices and policies in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1809–1818. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loupy A., Aubert O., Reese P.P., Bastien O., Bayer F., Jacquelinet C. Organ procurement and transplantation during the Covid-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:e95–e96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31040-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma V., Shaw A., Lowe M., Summers A., van Dellen D., Augustine T. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on renal transplantation in the UK. Clin Med (Lond) 2020 doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenhalgh T., Wherton J., Shaw S., Morrison C. Video consultations for covid-19. BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar D., Manuel O., Natori Y., Egawa H., Grossi P., Han S.H. Covid-19: A global transplant perspective on successfully navigating a pandemic. Am J Transplant. 2020;6:1512–1517. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuken P.A., Rauchfuss F., Albers S., Settmacher U., Trautwein C., Bruns T. Between fear and courage: Attitudes, beliefs, and behavior of liver transplantation recipients and waiting list candidates during the Covid-19 pandemic. Am J Transplant. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ajt.16118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browne T., Grandinetti A. Please do not forget about us: The need for patient-centered care for people with kidney disease and are at high risk for poor Covid-19 outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ajt.16305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans R.W., Manninen D.L., Garrison L.P., Jr., Hart L.G., Blagg C.R., Gutman R.A. The Quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:553–559. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502283120905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfe R.A., Ashby V.B., Milford E.L., Ojo A.O., Ettenger R.E., Agodoa L.Y.C. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbett R.W., Blakey S., Nitsch D., Loucaidou M., Mclean A., Duncan N. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in an urban dialysis center. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alberici F., Delbarba E., Manenti C., Econimo L., Valerio F., Pola A. A report from the Brescia Renal Covid Task Force on the clinical characteristics and short-term outcome of hemodialysis patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Kidney Int. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basile C., Combe C., Pizzarelli F., Covic A., Davenport A., Kanbay M. Recommendations for the prevention, mitigation and containment of the emerging SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) pandemic in haemodialysis centres. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;382:727–735. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.