Abstract

Objective: As a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown etiology, vulvar leukoplakia mainly affects postmenopausal and peri-menopausal females. The main clinical manifestations of vulvar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (VLSA) include itching, burning pain, and sexual dysfunction, which can lead to a decline in the quality of life. The existing treatment options include topical corticosteroid ointment, estrogen, and traditional Chinese medicine. However, their therapeutic effects on VLSA remain unsatisfactory. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the clinical efficacy and safety of photodynamic therapy (PDT) in combination with 5-aminoketovaleric acid (ALA) for the treatment of vulvar leukoplakia. Methods: A total of 30 patients with VLSA who failed routine treatment were treated with ALA-PDT. The patients were irradiated at a power density of 60-90 mW/cm2 with a red light at a wavelength of 635±15 nm for 20 min. Twenty percent of ALA water-in-oil emulsion was applied to the lesion and sealed with plastic film for 3 h. The treatment was repeated three times every 2 weeks. The objective and subjective symptoms and signs of vulvar lesions based on the horizontal visual analogue scale were recorded at 6 months after each treatment and the last treatment. Results: All patients completed three cycles of ALA-PDT and follow-up. The clinical symptoms of pruritus completely disappeared in 27 cases. Itching changed from severe to mild in three cases. The pathological changes of all subjects were improved. The main side effects of ALA-PDT were pain, erythema, and swelling. The side effects were temporary and tolerable. All patients reported their results as “satisfied” or “very satisfied”. Conclusions: ALA-PDT was an effective and safe approach for the treatment of VLSA.

Keywords: Vulvar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, 5-aminolevulinic acid, photodynamic therapy, refractory patients

Introduction

Vulvar leukoplakia belongs to vulvar intraepithelial non-tumor-like lesions, which can be divided into vulvar squamous epithelial hyperplasia, vulvar lichen sclerosus (VLS), and vulvar squamous epithelial hyperplasia with VLS. Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease characterized by remissions and exacerbations [1]. It affects mostly genital and perianal areas, although every skin area and oral mucosa can be involved [1]. Postmenopausal women are more commonly affected by LS compared with men, with a prevalence estimated at approximately 3%. Children and men can be affected with a prevalence of approximately 0.1% and 0.07%, respectively [2]. These percentages are possibly underestimated, as many cases are asymptomatic and undiagnosed. Some commonly reported symptoms include burning sensation, pain, itching, dyspareunia, dysuria, and painful defecation. With strange itching of the vulva as the main symptom and local pathological biopsy as the main diagnosis, LS is one of the refractory diseases in the world. Vulvar leukoplakia histiocytosis is active and its pathogenesis may be related to HPV infection. Some theories have been described, such as genetic theory, in which it is believed that about 22% of lichens can be inherited. Autoimmune factors and oxidative stress have also been accepted because of their high association with autoimmune diseases and the existence of highly specific antibodies to extracellular matrix proteins (ECM-1). A previous study has reported an autoimmune phenotype characterized by increased expressions of Th1-specific cytokines, dense infiltration of T cells, and increased expression of BIC/miR-155 [3]. This phenotype affects genital skin, and can cause severe itching, skin hypopigmentation, and poor skin elasticity or atrophy, which can lead to stricture, pain in sexual intercourse, pain in urination, and intestinal movement. It is the second leading cause of non-neoplastic vulvar disease and a risk factor for vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), including invasive SCC and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. The lifetime risk of untreated or improperly treated diseases is 2%-6% [4,5]. The diagnosis mainly depends on clinical diagnosis, and biopsy should be performed when malignant transformation is suspected. It should be distinguished from atopic dermatitis, extramammary Paget disease, genital warts, vitiligo, non-pigmented seborrheic keratosis, and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. In general hospitals, the classically cited prevalence rate is close to 0.1-0.3%. Therefore, LS is recognized as a rare disease by the Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD). Among all patients in general gynecology clinics, the incidence of LS is 1.7% [6]. A recent study in the Netherlands has estimated that the incidence of LS is at 14.6 per 100,000 women [4]. At present, there is no effective treatment for LS.

The treatment of vulvar leukoplakia is a worldwide problem. Treatment failure remains common. It is important to treat the disease as soon as possible, and a method that can reverse the progression of the disease should be used. At present, there is no definite treatment for vulvar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (VLSA). Therefore, the main purpose of currently available treatments is to relieve or eliminate symptoms (especially vulvar pruritus), rather than cure the disease. Traditional treatments include effective topical corticosteroids, hormones (testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone), 5-fluorouracil, and retinoic acid. Other physiotherapeutic methods have also been attempted, including surgery, cryosurgery, and carbon dioxide laser therapy, as well as focused ultrasound therapy, and traditional Chinese medicine therapy. Among the above-mentioned options, effective topical corticosteroids are the first-line treatment. Long-term use of topical corticosteroids may increase the risk of skin atrophy and pigmentation. Surgical intervention is usually applied to patients with atypical hyperplasia and malignant tendency. Surgery is often accompanied by infection, a high recurrence rate of disease, and unacceptable pain [7]. VLSA needs more effective treatments, with a lower incidence of side effects and a lower rate of recurrence.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been recommended during the treatment of VLSA [8]. As the second generation of porphyrin photosensitive drugs, 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) is an endogenous substance, which is the intermediate product of porphyrin metabolism, and it participates in the biosynthesis of heme in vivo, and has no phototoxicity. The principle of 5-ALA-mediated PDT is that 5-ALA is given topically in the lesion area, the hyperproliferative cells in the lesion area can be selectively absorbed, and 5-ALA is converted into protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) with strong photosensitivity in vivo. After light irradiation at specific wavelengths, many singlet oxygen and free radicals are produced, resulting in apoptosis and necrosis of cells in the lesion area, and no damage is induced to the surrounding normal tissues and cells. At present, the concentration of ALA used in the treatment is 20%, the light source is red light with wavelengths of 631-635 nm, and the power density is 60-90 J/cm2. Recently, 30 patients with vulvar leukoplakia were treated with ALA-PDT in our hospital, and the curative effect was remarkable. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of PDT-ALA for the treatment of vulvar squamous epithelial hyperplasia. Our findings suggested that ALA-PDT was an effective, non-invasive, and acceptable approach for the treatment of vulvar leukoplakia.

Materials and methods

Patients

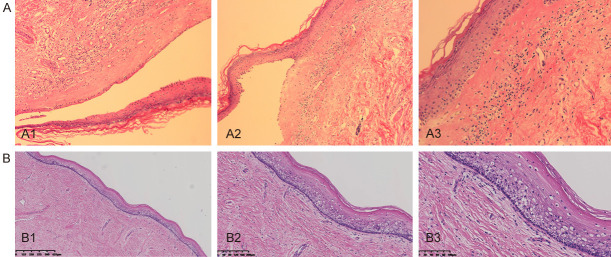

From January 2019 to December 2019, 30 patients with vulvar leukoplakia who failed conventional treatment were enrolled in the present clinical study. The clinical manifestations of vulvar lesions were hypopigmentation, waxy atrophy, lichenoid keratosis, or sclerosing lesions. All patients underwent vulvar biopsy, and the pathological diagnosis was consistent with vulvar leukoplakia (Figure 1A). Informed consent was obtained from every patient. All patients received a variety of routine treatments before selection, including effective topical corticosteroids, vitamin E, and Haijisin. However, these treatments only resulted in temporary improvements for some patients, or even no relief at all.

Figure 1.

A. Squamous epithelial atrophy, acellular collagen degeneration zone in the superficial dermis, inflammatory cell infiltration, consistent with vulvar sclerosing lichen; B. After treatment, pathology showed that chronic inflammation, acellular collagen band in dermis disappeared and superficial epithelial vacuolar degeneration improved.

Exclusion criteria were set as follows: LS patients with skin thickening, ulcer, and chapping, in which the possibility of canceration could not be ruled out; patients suffering from severe pelvic inflammation, cervical inflammation or other serious gynecological inflammations; patients with undiagnosed vaginal bleeding; people currently suffering from allergic diseases; patients with suspected or known porphyria or known history of allergy to experimental drugs and drugs with similar chemical structure; patients with severe diseases of cardio-cerebral vascular, nervous, mental, endocrine, and hematopoietic systems; patients with known severe low immune function or long-term use of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants; patients with malignant tumor; patients with abnormal liver function (ALT, AST, and total bilirubin 1.5 times higher than the normal upper limit) or renal dysfunction (creatinine and blood urea nitrogen 1.5 times higher than the normal upper limit); women during pregnancy and lactation; patients who took physiotherapeutic measures for vulvar leukoplakia after this diagnosis; those who participated in any drug clinical trial within 30 days before this trial; and those were not suitable to participate in this clinical trial according to the researchers’ judgment.

Treatments

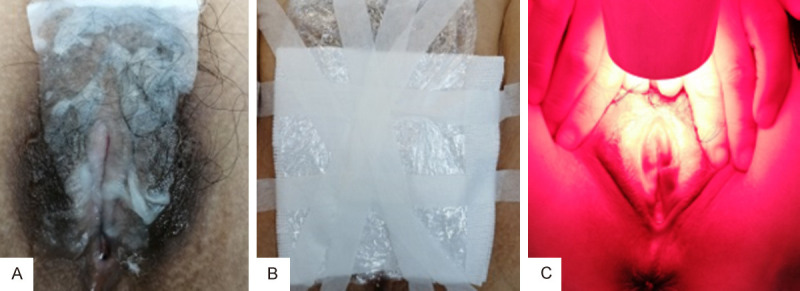

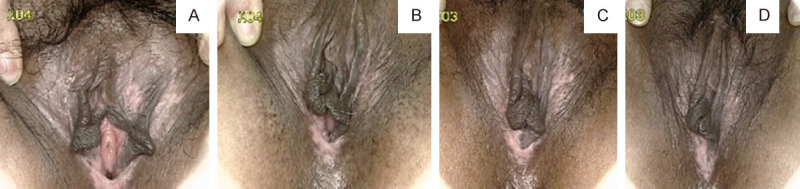

The pictures of VLSA lesions before each treatment and during follow-up were acquired using the same colposcope. The patients in the treatment group were treated with bladder lithotomy, the vulva was cleaned with normal saline and gently wiped using medical gauze, and the vaginal mouth was blocked with condoms to avoid contamination of secretion. During the treatment, the ALA dose was determined according to the area of vulvar leukoplakia, and an area of 1 cm2 was covered by 0.5 mL gel containing 118 mg ALA. Briefly, 118 mg 20% ALA (Shanghai Fudan Zhangjiang Biopharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) was applied to the hypopigmented area of vulvar skin (1 cm boundary) and covered with gauze and fresh-keeping film for 3 h. The patient was treated within 7 days after menstruation using a 635-nm LED gynecological therapeutic instrument (Wuhan Accord Optoelectronic Technology Co., Ltd.) under the conditions as follows: power density, 60-90 mw/cm2, and exposure time, 20 min (Figure 2). The treatment was given every 14 days for a total of three times, and sex life was prohibited during treatment. The patients were followed up at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months post-treatment (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

A. 5-ALA to the leukoplakia of the vulva. B. Uses cling film to cover Ella medicine. C. Illumina tes for 20 minutes. Power: 60-90 mw/cm2, exposure time: 20 minutes.

Figure 3.

A patient was followed up for 6 months after 3 times of ALA-PDT treatment to observe the general features of vulvar lesions. A. Before treatment. B. One month after treatment. C. 3 months after treatment. D. Six months after treatment. These figures showed that hyperkeratosis was alleviated, the area of vulvar leukoplakia was significantly reduced, even hypopigmentation was completely improved, and skin elasticity was significantly improved.

Follow-up and evaluation indicators

Clinical evaluation was conducted before each treatment and follow-up. Patients were also asked to assess the degree of subjective symptoms, such as itching, burning pain, and difficulty in sexual intercourse caused by VLSA, according to the horizontal visual analog scale (0= absence, 1= mild, 2= moderate, 3= severe). The objective clinical and morphological manifestations and the size of the lesions during before and at 1, 3, and 6 months after treatment were independently assessed by two gynecologists. The four objective parameters (atrophy, hyperkeratosis, depigmentation, and sclerosis) were graded according to the following scores: 3= severe, 2= moderate, 1= mild, 0= deletion [14]. The grading criteria were determined to evaluate the anatomical scope of the disease (0.5= vulvar surface involvement of less than 30% Magi; 1= vulvar surface involvement of 30-60% Magi; and 1.5= vulvar surface involvement of more than 60% Magi) [14]. The total score was obtained by summing the score of each parameter [14].

During each PDT treatment, patients were asked to provide visual analogue scores for treatment-related pain, ranging from 0 to 10 (0= no pain, 10= extreme pain), as well as the duration of the pain. In addition, during each treatment and follow-up, patients were asked to use the rating scale (0= dissatisfied, 1= somewhat satisfied, 2= satisfied, and 3= very satisfied) to assess their overall satisfaction.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS 20.00, and chi-square test. Student’s t-test were used when appropriate. P less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

All 30 patients completed the entire treatment and were followed up for 6 months. The average age of the patients was 48 years. The medical history ranged from 1 to 12 years, with an average course of 80 months. Table 1 shows the clinical features of the patients.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 48.23+11.45 |

| Gender | |

| Postmenopausal women | 15 |

| Perimenopausal women | 15 |

| Duration (months), mean ± SD | 81.31+68.10 |

| Macroscopic characteristics of lesions Atrophy | 30 |

| Hyperkeratosis | 30 |

| Depigmentation | 30 |

| Sclerosis | 19 |

| Previous treatment | 23 |

| Topical corticosteroids | 22 |

| Topical calcineurin inhibitors | 0 |

| Estrogens | 0 |

| Local injection | 0 |

| UVA1 | 0 |

| Others | 1 |

Clinical evaluation

Patients showed significant relief of itching, burning pain, and difficulty in sexual intercourse after ALA-PDT. Before ALA-PDT, 28 patients complained of moderate and severe vulvar pruritus, two patients had no pruritus, and hypopigmentation of vulvar skin was found during physical examination. The average pruritus score before the first ALA-PDT cycle was 2.4. With treatment, the score of itching was gradually decreased. After the third ALA-PDT cycle, the itching symptoms of 25 patients completely disappeared, and the itching symptoms of three patients were relieved from severe to mild. Two patients complained of mild to moderate vulvar pain, 28 patients had no vulvar pain, and four patients complained of moderate to severe sexual intercourse difficulty. After three cycles of ALA-PDT, the pain and difficulty in sexual intercourse completely disappeared. During the 6-month follow-up after the last treatment, no recurrence of these symptoms was found in these 30 patients. Table 2 lists the subjective symptoms of the patients at 6 months after the first and last treatments.

Table 2.

The subjective symptoms of patients at the first treatment and last follow-up

| No | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 48.37±11.75 | |

| VAS of before the treatment | Itching | 2.4±0.82 |

| Pain | 0.1±0.40 | |

| Dyspareunia | 1.23±0.77 | |

| VAS of the last follow-up | Itching | 0.17±0.59 |

| Pain | 0±0.00 | |

| Dyspareunia | 0.07±0.37 |

Patients’ self-evaluation

After follow-up for 6 months, the clinical signs of all patients were significantly improved. The average score of clinical signs at baseline was significantly higher compared with that at the last follow-up. Before the first PDT, all patients showed hypopigmentation and atrophy in vulvar lesion area, hyperkeratosis was found in seven cases, and vulvar sclerosis was found in five cases. The vulvar lesions were significantly reduced in 25 patients after treatment, and the vulvar lesions completely disappeared in five cases. The average score at 6 months after the last treatment was lower compared with that before the treatment. Before the treatment, the vulvar lesions of 21 patients were more than 60%, the vulvar lesions of seven patients were 30%, and the vulvar lesions of two patients were less than 30%. At 6 months after the last treatment, the vulvar lesions of all patients were less than 30%. Among them, the vulvar lesions of 17 patients basically or completely disappeared (Table 3). After the PDT, the thickness of epidermis was reduced, and the inflammatory cell infiltration of dermis was ameliorated (Figure 1B), suggesting that ALA was effective in the treatment of LS and had a therapeutic effect on vulvar inflammation.

Table 3.

The clinical manifestation and lesions size and the scores before treatment and 6-months follow-up after the last session

| No | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| The clinical manifestation at baseline | Atrophy | 2.07±0.69 |

| Depig mentatior | 2.43±0.57 | |

| Hyperkertosis | 2.17±0.75 | |

| Lesions size at baseline | Sclerosis | 1.7±0.88 |

| <30% | 0.05±0.15 | |

| 30-60% | 0.27±0.45 | |

| >60% | 0.95±0.74 | |

| Total scores | 9.73±2.47 | |

| The clinical manifestation at last follow-up | Atrophy | 0.25±0.43 |

| Depigmentation | 0.47±0.57 | |

| Hyperkertosis | 0.17±0.38 | |

| Lesions size at last follow-up | Sclerosis | 0.17±0.35 |

| <30% | 0.25±0.25 | |

| 30-60% | 0±0 | |

| >60% | 0±0 | |

| Total scores | 1.23±1.65 |

Adverse reactions

No serious adverse reactions were observed during and after the treatment. The main adverse reactions of ALA-PDT were pain and burning sensation during irradiation, which gradually disappeared within 3-48 h. Twenty-eight patients were able to tolerate the pain, and two patients were given painkillers and lidocaine to relieve the pain. The score of the treatment-related pain was 3-6, the visual analogue score was 10, and the average pain score was 3.93. Slight erythema and swelling were seen in all patients after each irradiation. These symptoms lasted for 4 days and almost disappeared after 3 days. No infection, blistering or erosion was observed during and after the treatment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adverse reactions after treatment with ALA-PDT in patients

| Adverse reactions | Value |

|---|---|

| Pain (incidence) | 30 |

| Pain (VAS/mean ± SD) | 3.6±0.76 |

| Burning sensation (incidence) | 29 |

| Erythema (incidence) | 28 |

| Swelling (incidence) | 29 |

| Hyperpigmentation (incidence) | None |

| Infections (incidence) | None |

| Blister (incidence) | None |

| Erosion (incidence) | None |

Discussion

Vulvar leukoplakia, also known as white lesion of vulva, belongs to vulvar intraepithelial non-tumor-like lesions. It is a group of chronic diseases with degeneration and pigmentation of female vulvar skin. This disease is a skin disease that has a great impact on the female reproductive system. The diagnosis is mainly made based on local pathological biopsy. Vulvar leukoplakia can be divided into vulvar squamous epithelial hyperplasia, VLS, and vulvar squamous epithelial hyperplasia with VLS. Vulvar leukoplakia is more common in middle-aged women and often occurs in clitoris, labia minora, and medial labia majora. The lesions are hypertrophic patches or plaques of different sizes, numbers, and shapes. The main symptoms are strange itching and burning pain of the vulva. In addition, it may narrow the entrance to the vagina and urethra, resulting in burning urination and difficulty in sexual intercourse. Generally, VLS’s main symptom is pruritus (93%), which frequently causes complications [9]. For instance, scarring can lead to narrowing of vaginal introitus and clitoral hood adhesions. This might induce the formation of pseudocysts, which in turn might lead to dysuria, dyspareunia, pain during defecation, bleeding, and a need for surgical reconstruction [10].

This disease can seriously affect the quality of life and sexual health of patients, and it is associated with an increased risk of malignant transformation, such as vulvar SCC. The International Health Organization has listed vulvar leukoplakia as one of the refractory diseases in the world. Therefore, treatment is important for relieving symptoms and preventing complications.

In recent years, various treatments have been developed at home and abroad, while the results are different, while no approach can cure such condition [11]. Lan T et al. have conducted a trial consisting of 10 cases of vulvar pruritus treated with ALA-PDT and found that nine cases of vulvar pruritus are completely cured, and one case of pruritus was relieved. All patients were satisfied with the results. Safety is high, treatment can be repeatedly used, and it is not easy to produce drug resistance.

At present, the first-line therapy for VLSA is topical high-efficacy corticosteroids, and 0.05% clobetasol propionate cream is the gold standard. The drawback of most published studies is that they only followed up with the patients for the first 6 months. There were few long-term observations and studies on a sufficient number of treated patients. For most publications, the maximum recorded observation period was 3 years. A descriptive cohort study from the UK had an average follow-up period of 66 months; a long-term study from France was prospectively conducted for more than 10 years; and a study from Australia was prospectively conducted for more than 8 years [12-14]. The latter study consisting of 507 women provided our best evidence that most experienced practitioners know that although TCS is easy to induce remission, it does not cure VLS. In addition, the French study reported that if the treatment is stopped, the recurrence rate is 84%. Topical use of corticosteroids not only causes recurrence of symptoms, but also results in side effects, such as irritation, dryness, burning, skin atrophy, and hypopigmentation. Therefore, it is highly necessary to develop a more effective treatment with less side effects and a lower recurrence rate.

In 1990, Kennedy et al. [15] have applied PDT in combination with aminolevulinic acid (ALA-PDT) in dermatology for the first time. PDT has been widely used in the treatment of various skin diseases and non-melanoma skin tumors [16]. PDT uses photosensitizers in combination with light to trigger photodynamic reactions to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), especially singlet oxygen, leading to apoptosis and necrosis of target cells. The mechanism of PDT is based on the interaction of photosensitizer, visible light, and oxygen to produce ROS (such as singlet oxygen), which can destroy organelles, cause cell and tissue destruction, promote microvascular occlusion, and stimulate immune response [16]. When ALA is applied to the injured surface of the skin, it penetrates the skin barrier, selectively accumulates in the target cells, and metabolizes into photoactive free porphyrins, which are also called PPIX [16]. When the best light is emitted to excite PPIX, it produces singlet oxygen and destroys the target tissue. PDT is a non-invasive treatment that can even destroy small cancer cells and dysplastic cell clusters without affecting healthy tissue [17]. Because DNA is not targeted, there is no treatment-induced mutation or selection, and such approach can be repeatedly used without drug resistance [18].

Agnieszka [19] has studied the safety of PDT and its effect on pregnancy and delivery of women after PDT. The median observation time from the end of treatment to delivery is 3.92 years (2-7 years), and 10 patients deliver healthy full-term infants. One of the patients with diabetes also successfully delivered, and two patients gave birth to two children. Our current study proved that PDT had almost no negative effect on female reproductive function. Its safety could be further determined. In Shi et al. [20] erosions after PDT were treated with mupirocin ointment for one week. The other two articles did not report any after-treatment [21,22]. In summary the three studies reported decrease in subjective symptoms. Olejek et al. [22] concluded a relevant subjective symptom reduction with both types of lamps, without significant difference in results between the two groups. The two smallest studies Lan et al. [21] (n=10) and Shi et al. [22] (n=20) also described a substantial improvement in objective lesion characteristics.

The patients in the treatment group were treated with 20% ALA on the lesions, which were sealed with plastic film for 3 h to promote the penetration of ALA, followed by irradiation with 90-nm red light at a power density of 60 mW/cm2 for 20 min, and a good therapeutic effect was obtained. Pain, burning sensation, mild erythema, and swelling were the main adverse reactions found in this study, which were tolerable in all patients. Vulvar pain and swelling were treated with vulvar cold compress, which were relieved within 1 day after the treatment. In future treatment, the patients would be divided into two groups. In one group, the ALA concentration would be 20%, while it would be 10% in the other group, and the two groups of patients would be compared in terms of the vulvar pain and clinical treatment effect.

Prodromidou et al. have found that PDT can be used in precancerous skin lesions and skin cancer without long-term adverse effects. It has a therapeutic effect on LS. Some patients have different degrees of erythema, edema, and burning sensation [23]. A total of 24 patients with VLSA were treated with PDT for three to six cycles every 2 weeks. All patients could tolerate the treatment process, and the itching symptoms in 70.83% patients disappeared completely [24]. Romero et al. [25] treated a case of intractable erosive VLS with PDT at an interval of 1 month. After treatment, the symptoms, erosion, and skin lesions basically disappeared. The only discomfort was the moderate pain during irradiation, which disappeared after a few days. Sotiriou et al. [26] treated 10 patients with VLS using PDT, twice every 2 weeks. The treatment was well tolerated. The symptoms of all patients were significantly relieved, and the quality of life was improved, while the objective clinical signs were only slightly improved in nine cases. Sotiriou et al. [27] treated five patients with intractable VLS using a single cycle of ALA-PDT. It was reported that the symptoms were completely relieved for more than 3 months, while the appearance of vulvar lesions was only slightly improved. ALA-PDT was a safe and effective method for the treatment of VLS, and the therapeutic effects could be maintained for at least 3 months. The therapeutic effects may decrease during the 3-6-month period after PDT [28]. The combination of holmium laser therapy and ALA-PDT may further improve the efficacy with good tolerance of VLS patients [29].

Methods to reduce the side effects of PDT

In the process of ALA-PDT for vulvar leukoplakia, patients experience various degrees of vulvar pain. The pain caused by lower light intensity was less. High-intensity light caused severe cell necrosis, while low intensity mainly caused cell apoptosis [30]. Apoptosis does not cause inflammation, while necrosis can lead to the release of inflammatory mediators, such as adenosine and bradykinin triphosphate, resulting in activation of sensory and motor nerves, and induction of pain [31]. Cottrell WJ et al. proposed that the initial stage should be irradiated at a light intensity of 40 mw/cm2.

Photobleaching occurs in most of PPIX, followed by irradiation with high light intensity at 150 mw/cm2, and rapid administration of residual light does not only significantly reduce the pain in the process of illumination, but also does not affect the photodynamic effect [32].

During treatment, we used lidocaine local external spray, wet compress, and infiltration anesthesia. Sensitive patients were treated with biphasic irradiation to relieve vulvar pain. In subsequent treatment, the treatment was changed to a two-step radiation therapy with an irradiation at 50 mw/cm2 for 5 min before the treatment. After patients adapted to mild pain during the treatment, it was then changed to an irradiation at 90 mw/cm2 for 17 min, by which a consistent total radiation energy was given. The vulvar skin damage and exudation after treatment were reduced. During treatment, all the patients were tolerable, and the treatment was not interrupted.

Pathogenesis of VLS

ECM-1, which is involved in the autoimmune mechanism, is the target of humoral autoantigen. Many studies have speculated that the pathogenesis of LS may develop along the immune genetic pathway to humoral autoimmunity, because the development of autoantibodies against unknown autoantigens may explain the histological changes of extracellular remodeling. The dysfunction of ECM-1 is found at the dermal-epidermal junction and has long been related to the pathogenesis of LS. It supports the loss of functional mutation of ECM-1 gene in lipoproteinosis (LIP). LIP is an autosomal recessive dermatosis with clinical symptoms like LS, suggesting that ECM-1 is a powerful presumptive autoantigen in LS autoimmunity. Further analysis showed that ECM-1 was significantly down-regulated only in childhood male LS lesions compared with adult men and healthy controls. Therefore, autoimmunity to ECM-1 alone cannot completely explain the pathogenesis of LS. Through the mutation of ECM-1 gene or the loss of autoantibodies in this particular ECM-1 region, it will effectively destroy the usual regulatory binding of ECM-1 to MMP-9, resulting in an overreaction of MMP-9 collagenase activity to destroy collagen homeostasis, which in turn may explain the focal basement membrane destruction observed in LS [33].

Over-expression of miR-155 promotes the fibroblast proliferation by down-regulating FOXO3 and CDKN1B. In addition to its possible role in inducing autoimmunity, miR-155 is also related to the formation of sclerotic tissue. Ren et al. [34] found that the expression level of miR-155 in LS tissue was increased, while the expression levels of FOXO3 and CDKN1B were decreased accordingly. FOXO3 and CDKN1B are related to fibroblast proliferation and cell cycle inhibition, respectively. The decreased expressions of FOXO3 and CDKN1B may promote the proliferation and persistence of fibroblasts, explaining the high level of collagen synthesis in transparent and hardened dermis in LS [35].

Some scholars believe that the white lesions of the vulva may be related to the decreased expression of 5-α reductase in the vulva and the unrealized transformation of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone [36]. The expression of CDK inhibitor p27Kip1 in vulvar squamous epithelial proliferative lesions is significantly decreased, and the oxidative damage of DNA is significantly increased [37]. p27Kip1 was constantly expressed in normal vulvar epithelium cells while a progressive significant reduction in the percentage of p27Kip1-positive cells was observed in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasias (77%) and in invasive carcinomas (64%). The abnormal expression of p27Kip1 may be one of the therapeutic factors. ALA-PDT is effective in the treatment of female vulvar white lesions with p27Kip1 as the target.

Collectively, our study provided evidence that ALA-PDT was an efficient and safe approach for the treatment of VLSA, especially for patients who failed conventional treatment. There were no serious adverse reactions during and after the treatment, and all patients tolerated the treatment well. Although our study showed very satisfactory treatment results, the small sample size and short follow-up time were the main shortcomings of our current study. A larger trial with longer follow-up periods, more patients, and good adverse reactions should be carried out to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ALA-PDT in the treatment of VLSA. In addition, no agreement has been reached so far on the parameters, such as the concentration of ALA, application time, light source (power and wavelength), exposure time (energy density and power density), repetition times, and frequency of VLSA treatment. Considering the huge potential benefits of PDT to patients, multicenter clinical trials are needed in future studies to obtain the optimal PDT parameters. The exact mechanism underlying the ALA-PDT-improved LS remains uncertain. Our study provided valuable insights into the related mechanism.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Scientific and Technological Project of Changzhou City Commission of Health and Family Planning for Aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in the treatment of cervical carcinoma in situ and persistent HPV infection after operation (ZD201807).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27–47. doi: 10.1007/s40257-012-0006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girtschig K. Lichen sclerosus-presentation, diagnosis and management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:337–343. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran DA, Tan X, Macri CJ, Goldstein AT, Fu SW. Lichen sclerosus: an autoimmunopathogenic and genomic enigma with emerging genetic and immune targets. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1429–1439. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.34613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleeker MC, Visser PJ, Overbeek LI, Beurden MV, Berkhof J. Lichen sclerosus: incidence and risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1224–1230. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Micheletti L, Preti M, Radici G, Boveri S, Pumpo OD, Privitera SS, Ghiringhello B, Benedetto C. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and neoplastic transformation: a retrospective study of 976 cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:180–183. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein AT, Marinoff SC, Christopher K, Srodon M. Prevalence of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a general gynecology practice. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:477–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burger MP, Obdeijn MC. Complications after surgery for the relief of dyspareunia in women with lichen sclerosus: a case series. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:467–472. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, sMoher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1061–1067. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee A, Fischer G. Diagnosis and treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:695–706. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lan T, Zou Y, Hamblin MR, Yin R. 5-Aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in refractory vulvar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: series of ten cases. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;21:234–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1061–1067. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus infuence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702–706. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.6.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renaud-Vilmer C, Cavelier-Balloy B, Porcher R, Dubertret L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus: efect of long-term topical application of a potent steroid on the course of the disease. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:709–712. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.6.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy JC, Pottier RH, Pross DC. Photodynamic therapy with endogenous protoporphyrin IX: basic principles and present clinical experience. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1990;6:143–148. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(90)85083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen X, Li Y, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy in dermatology beyond non-melanoma cancer: an update. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2017;19:140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, Hahn SM, Hamblin MR, Juzeniene A, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J, Mroz P, Nowis D, Piette J, Wilson BC, Golab J. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson BC, Patterson MS. The physics, biophysics and technology of photodynamic therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:R61–109. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/9/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazdziarz A. Successful pregnancy and delivery following selective use of photodynamic therapy in treatment of cervix and vulvar diseases. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2019;28:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi L, Miao F, Zhang LL, Zhang GL, Wang PR, Ji J, Wang XJ, Huang Z, Wang HW, Wang XL. Comparison of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy and clobetasol propionate in treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:684–688. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan T, Zou Y, Hamblin MR, Yin R. 5-Aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in refractory vulvar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: series of ten cases. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;21:234–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olejek A, Gabriel I, Bilska-Janosik A, Kozak-Darmas I, Kawczyk-Krupka A. ALA-photodynamic treatment in Lichen sclerosus-clinical and immunological outcome focusing on the assesment of antinuclear antibodies. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2017;18:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prodromidou A, Chatziioannou E, Daskalakis G, Stergios K, Pergialiotis V. Photodynamic therapy for vulvar lichen sclerosus-a systematic review. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22:58–65. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biniszkiewicz T, Olejek A, Kozak-Darmas I, Sieroń A. Therapeutic effects of 5-ALA-induced photodynamic therapy in vulvar lichen sclerosus. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2005;2:157–160. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(05)00062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero A, Hernández-Núñez A, Córdoba-Guijarro S, Arias-Palomo D, Borbujo-Martínez J. Treatment of recalcitrant erosive vulvar lichensclerosus with photodynamic therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:S46–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sotiriou E, Panagiotidou D, Ioannidis D. An open trial of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapyfor vulvar lichen sclerosus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;141:187–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sotiriou E, Apalla Z, Patsatsi A, Panagiotidou D. Recalcitrant vulvar lichen sclerosis treated with aminolevulinic acid-photodynamic therapy: a report of five cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1398–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Wang Y, Wang J, Li S, Xiao Z, Feng Y, Gu J, Li J, Peng X, Li C, Zeng K. Evaluation of the efficacy of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;29:101596. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.101596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao Y, Zhang G, Wang P, Li C, Wang X. Treatment of hyperkeratotic vulvar lichen sclerosus with combination of holmium laser therapy and ALA-PDT: case report. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101762. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Francois A, Salvadori A, Bressenot A, Bezdetnaya L, Guillemin F, D’Hallewin MA. How to avoid local side effects of bladder photodynamic therapy: impact of the fluence rate. J Urol. 2013;190:731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Ehnert C, Brenner GJ, Woolf CJ. Bradykinin and peripheral sensitization. Biol Chem. 2006;387:11–14. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cottrell WJ, Paquette AD, Keymel KR, Foster TH, Oseroff AR. Irradiance-dependent photobleaching and pain in delta-aminolevulinic acid-photodynamic therapy of superficial basal cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4475–4483. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujimoto N, Terlizzi J, Aho S, Brittingham R, Fertala A, Oyama N, McGrath JA, Uitto J. Extracellular matrix protein 1 inhibits the activity of matrix metalloproteinase 9 through high-affinity protein/protein interactions. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:300–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren L, Zhao Y, Huo X, Wu X. MiR-155-5p promotes fibroblast cell proliferation and inhibits FOXO signaling pathway in vulvar lichen sclerosis by targeting FOXO3 and CDKN1B. Gene. 2018;653:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neill S. Treatment for lichen sclerosus. BMJ. 1990;301:555–556. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6751.555-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zannoni GF, Faraglia B, Tarquini E, Camerini A, Vrijens K, Migaldi M, Cittadini A, Sgambato A. Expression of the CDK inhibitor p27kip1 and oxidative DNA damage in non-neoplastic and neoplastic vulvar epithelial lesions. Mod Pathol. 2016;19:504–513. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sgambato A, Cittadini A, Faraglia B, Weinstein IB. Multiple functions of p27Kip1 and its alterations in tumor cells: a review. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:18–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200004)183:1<18::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]