Abstract

Early recruitment of neutrophils from the blood to sites of tissue infection is a hallmark of innate immune responses. However, little is known about the mechanisms by which apoptotic neutrophils are cleared in infected tissues during resolution and the immunological consequences of in situ efferocytosis. Using intravital multi-photon microscopy (IV-MPM), we show previously unrecognized motility patterns of interactions between neutrophils and tissue-resident phagocytes within the influenza-infected mouse airway. Newly infiltrated inflammatory monocytes become a major pool of phagocytes and play a key role in the clearance of highly motile apoptotic neutrophils during the resolution phase. Apoptotic neutrophils further release epidermal growth factor (EGF) and promote the differentiation of monocytes into tissue-resident antigen-presenting cells (APCs) for activation of anti-viral T cell effector functions. Collectively, these results suggest that the presence of in situ neutrophil resolution at the infected tissue is critical for optimal CD8+ T cell–mediated immune protection.

Introduction

Despite the available antiviral drugs and vaccines against seasonal strains, influenza virus causes substantial seasonal and pandemic morbidity and mortality1. While clearance of influenza-infected cells is primarily mediated by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, the now well-established dependency of anti-viral host responses on both the innate and adaptive immune compartments suggests that harnessing innate immunity might form a basis for the development of effective vaccines and novel therapeutic approaches.

Once they complete their action, early infiltrated neutrophils should be quickly cleared from infected tissue sites. Delayed neutrophil resolution is often associated with widespread tissue damage, organ failure, and ultimately death in severely infected patients. The cellular and molecular signals that drive the initiation of neutrophil-mediated inflammatory responses are well studied, but we have a relatively poor understanding of the mechanisms through which the neutrophil response is resolved; thus, it has been challenging to clearly differentiate neutrophil host-protective roles from their damaging inflammatory functions. We undertook this study to address critical knowledge gaps regarding the function and fate of neutrophils during influenza infection, and their roles in anti-viral T cell responses. IV-MPM of our newly generated Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice revealed a striking motility pattern of neutrophil and tissue-resident phagocytes during the resolution phase in a mouse influenza infection model. Based on several lines of evidence from our study, we propose novel functions of neutrophil resolution that can actively promote T cell function in the infected airway.

Results

The presence of in situ efferocytosis of neutrophils in the influenza-infected trachea

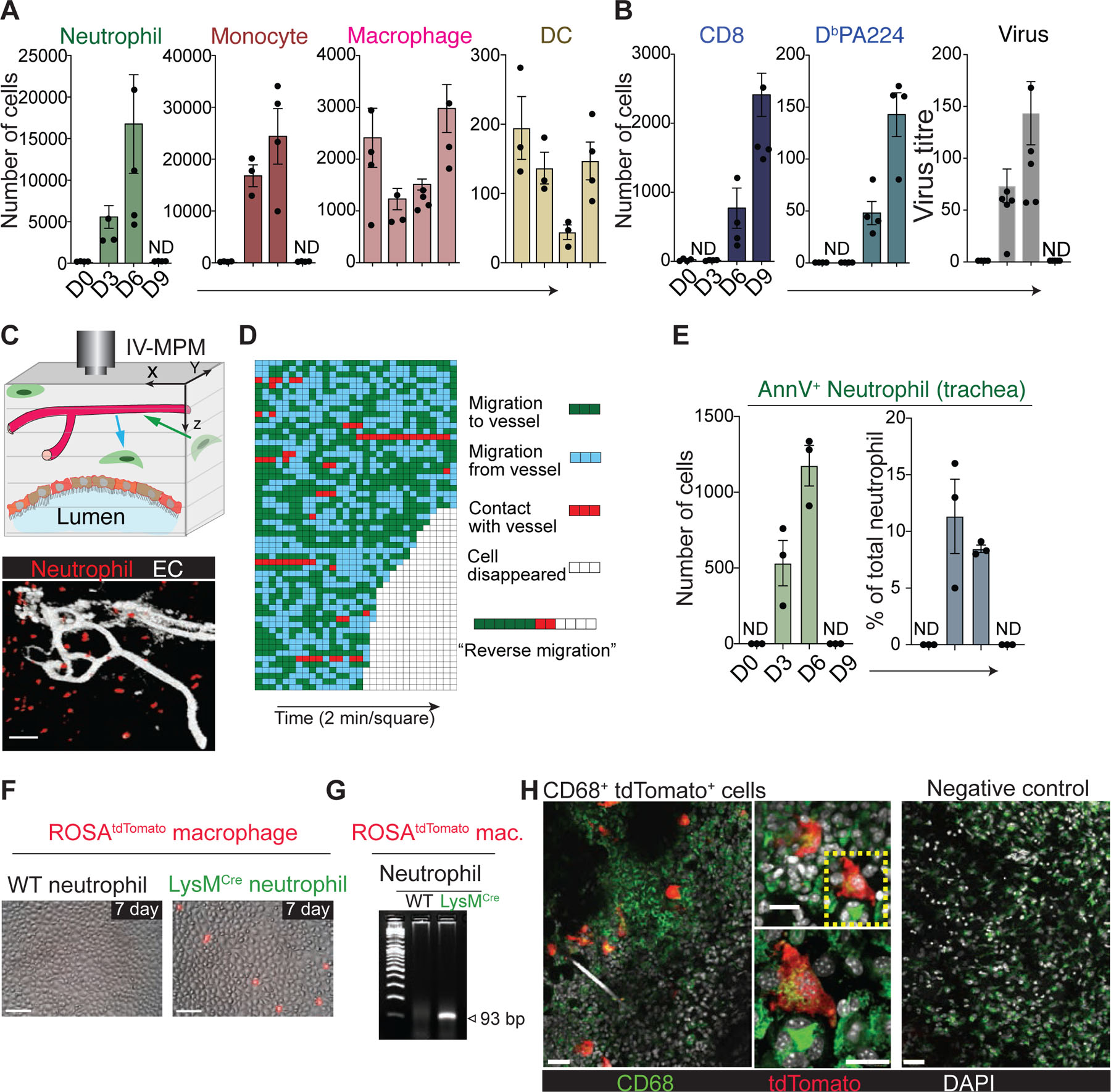

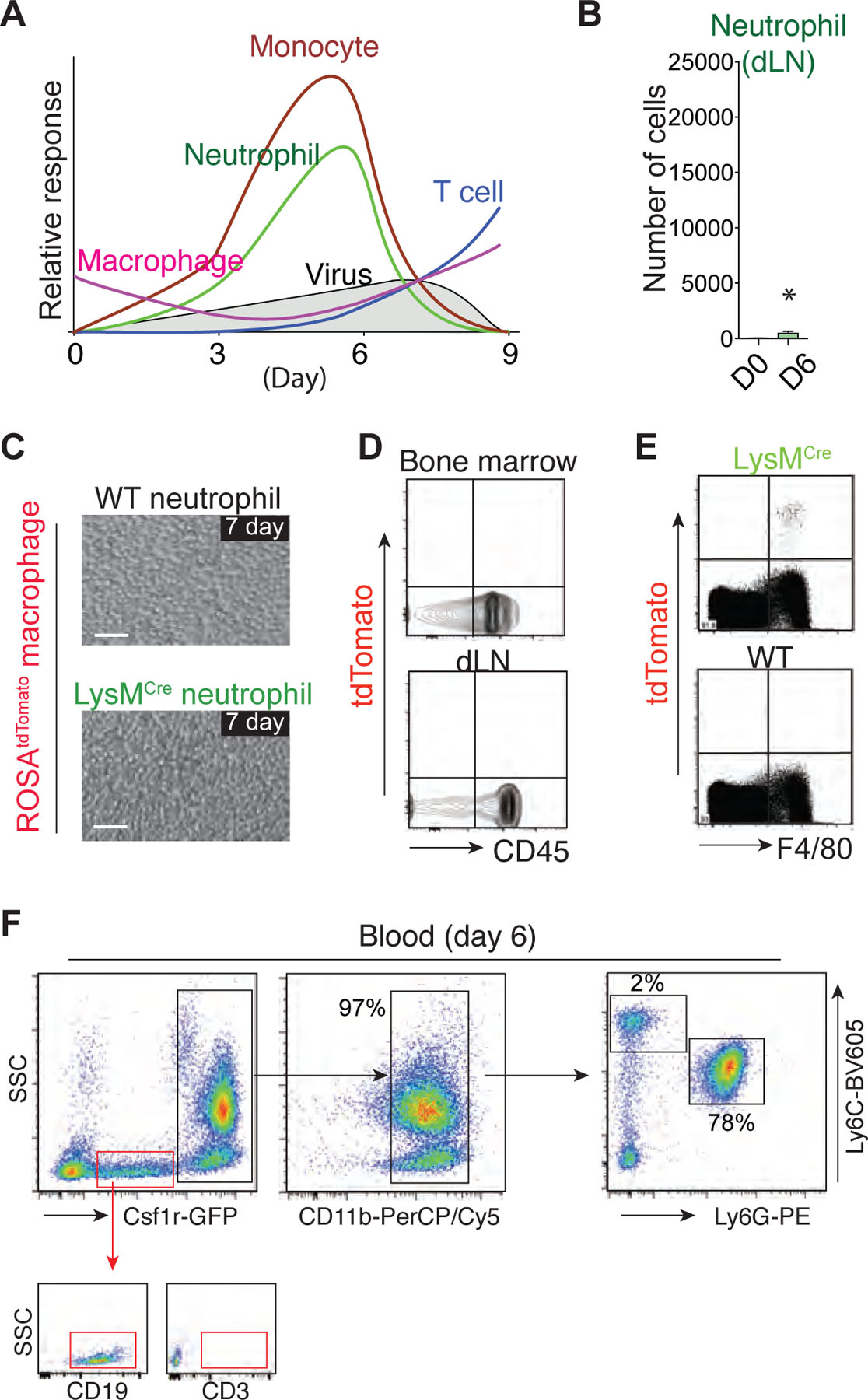

To examine the dynamics of neutrophil resolution during infection, we first measured overall host immune responses in the mouse trachea infected with influenza virus. Infection of mice with H3N2 influenza A/Hong Kong/X31 (HKx31) virus resulted in a massive transient infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes into the trachea, with the increase in their numbers peaking at day 6, followed by a rapid and near complete disappearance of both cell types (“resolution”) at day 9 (Fig. 1a). Unlike neutrophils and monocytes, tissue-resident macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) were partially depleted during the early infection period and gradually replenished by day 9 (Fig. 1a). During these active early innate immune reactions, there was continuous viral replication until the recruitment of CD8+ T cells at approximately day 6 – day 8 (Fig. 1b). Importantly, the initial neutrophil response was actively resolved in the infected tissue even during ongoing viral infection and inflammation prior to the maximum CD8+ T cell response (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a). When both the total CD8+ T cell response and the number of CD8+ T cells specific for the nucleoprotein-derived epitope of influenza A virus presented by H2-Db (DbPA224) reached peak levels at day 9, the mice were recovered and had completely cleared the influenza virus (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. In situ efferocytosis of neutrophils in the influenza-infected trachea.

(a) Flow cytometric analysis of innate immune cells in the trachea after influenza infection (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3 mice per group). ND, not detected. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of total (CD3+CD8+) and virus-specific (CD3+CD8+DbPA224) CD8+ T cells (left) (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3 mice per group). Viral nucleoprotein (NP) mRNA levels (right) measured using qRT-PCR and normalized to the cellular actin mRNA level (%) (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3 mice per group). ND, not detected. (c) (Top) Cartoon illustrating IV-MPM analysis. (Bottom) Representative IV-MPM image of neutrophils (red) in the trachea of Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato mice infected with influenza virus. Blood vessel (anti-CD31 antibody): white. Bar, 50 µm. (d) Each horizontal line: an individual neutrophil; Each square: 2-min interval. A representative example of reverse migration is shown on the right. Green and blue squares correspond to neutrophils migrated toward or away from the nearest blood vessel, respectively. Red squares correspond to the neutrophil contacted the vessel. Empty squares correspond to the time point at which neutrophils disappeared from the image. (e) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic neutrophils in the trachea after influenza infection (mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice per group). ND, not detected. (f) Apoptotic neutrophils and bone marrow (BM)-derived macrophages from ROSAtdTomato mice were co-cultured for 7 days. A time-lapse image representative of three independent experiments is shown. Bar, 50 μm. (g) Recombination of LoxP sites in ROSAtdTomato BMDMs after co-culture with apoptotic LysMCre neutrophils was detected by PCR of genomic DNA. (h) LysMCre neutrophils were injected into the ear of recipient ROSAtdTomato mice (B6-Albino). The injection site was imaged. CD68+ tdTomato+ (left and middle images) cells are shown in green. The boxed area (middle, upper) is shown in the middle, lower panel. WT neutrophils were injected for the negative control (right). Representatives of three independent experiments are shown. Scale bars represent 50 μm (left and right) and 25 μm (middle).

After recruitment and activation at the site of inflammation, neutrophils are thought to undergo apoptosis, after which they are cleared by other tissue-resident leukocytes with phagocytic activity, such as macrophages. This paradigm was recently challenged by studies suggesting that neutrophils actively leave the injury site and migrate into the surrounding healthy tissue or vasculature, a process referred to as reverse migration2. However, neutrophil reverse migration has never been investigated in live tissue under active pathogen infection conditions. To address this, we infected Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato mice3 with HKx31 virus and performed IV-MPM on the surgically cannulated trachea to determine whether neutrophils leave the infection site and reenter the vasculature (Fig. 1c). As a substantial number of cells accumulated in the infected trachea, the neutrophils remained highly motile during infection (day 3 – day 6), with exploratory motion relative to the location of neighboring vessels (Supplementary Movie 1). This motility pattern indicated the absence of any chemotactic signals that would distribute neutrophils away from the injury site or drive these cells toward the vasculature. Despite extensive analysis of in vivo 3D-live imaging with unbiased computational single-cell tracking of neutrophils in the infected trachea, we failed to detect migratory patterns that represent overt neutrophil reverse migration (Fig. 1d). Although there was a significant increase in the number of neutrophils in the draining lymph node (dLN) during infection, the total number of neutrophils in the dLN was negligible compared to the number of neutrophils in the infection site (Extended Data Fig. 1b); instead, there was a significant accumulation of apoptotic (CD11b+Ly6G+Annexin V+) neutrophils in the infected tissue site during active infection (day 3 – day 6) (Fig. 1e). Thus, it is also unlikely that lymphatic draining is the main process for the resolution of the local neutrophil response.

Because of the lack of detectable neutrophil death and efferocytosis at the site of injury, it was proposed that reverse migration is a main mechanism by which neutrophil-mediated inflammation is resolved4,5. Although we failed to observe a similar reverse migration pattern in neutrophils, this discrepancy may be due in part to the relatively short imaging time or limited area of the microcopy image. To confirm these findings and further determine the absence (or presence) of neutrophil apoptosis and efferocytosis at sterile injury sites, we developed a novel fate-mapping strategy. Previously, it was demonstrated that genomic DNA from apoptotic cells can be transferred to phagocytosing cells via the uptake of apoptotic bodies, and it becomes transiently activated and expressed within the phagocytes6–9. Based on this phenomenon, we designed a Cre-LoxP system to induce a color to be switched on specifically in reporter-expressing cells (e.g., tdTomato+) that engulf Cre-expressing apoptotic cells and tested whether we could utilize this approach to track the long-term fates of phagocytes that take up apoptotic neutrophils. We first isolated neutrophils from LysMCre mice and induced apoptosis by incubation for 24 h. WT (Creneg) or Cre-expressing apoptotic neutrophils were then co-incubated with bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) isolated from ROSA26-tdTomato mice. Red color-converted tdTomato+ BMDMs appeared only in co-cultures with LysMCre neutrophils within 24 – 48 h and lived for up to 7 days (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Movie 2). In addition, Cre-mediated recombination was readily detected by PCR in BMDMs that engulfed LysMCre neutrophils (Fig. 1g). Prolonged incubation of ROSAtdTomato-BMDMs with microparticles prepared from LysMCre-neutrophils10 or separation of BMDMs and neutrophils by a transwell filter (Extended Data Fig. 1c) did not induce a color change, suggesting that the engulfment of apoptotic cells or cellular fragments (but not exosomes and/or microvesicles) through direct contact is required for the gene recombination.

To test whether gene transfer between apoptotic neutrophils and tissue-resident phagocytes occurs in vivo, we locally injected LysMCre Ly6G+ neutrophils into the ear dermis of ROSAtdTomato-recipient mice (ROSAtdTomato B6-Albino). After 5 days, we examined the injection site for the presence of reporter phagocytes that took up Cre-expressing neutrophils (i.e., tdTomato expression). A small number of tdTomato+ cells (red) appeared in the ears of mice that received LysMCre-neutrophils but not WT-neutrophils (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Movie 3). The color change in vivo was not detected in other organs, including the bone marrow (BM) and dLN (Extended Data Fig. 1d). To investigate the nature of these cells, we analyzed the expression of CD68, which is a marker of monocytic phagocytes and macrophages. We observed that 100% of tdTomato+ cells in the ears of ROSAtdTomato-recipient mice that were injected with LysMCre-neutrophils were also CD68+ cells, suggesting that tissue resident macrophages had taken up the neutrophils (Fig. 1h). We further confirmed the color change in vivo by injecting live BM cells prepared from LysMCre mice into the peritoneum of ROSAtdTomato mice. Flow cytometry analysis on day 3 post-injection clearly showed the presence of tdTomato+/F4/80+ macrophages in the peritoneal lavage of ROSAtdTomato mice that were injected with LysMCre cells but not in that of mice injected with WT cells (Extended Data Fig. 1e). Collectively, these data suggest that a significant fraction of in vivo clearance of apoptotic cells occurs through in situ efferocytosis that is mediated by tissue-resident phagocytes.

Simultaneous imaging of neutrophils and other tissue-resident myeloid cells reveals novel motility patterns of cell-cell interactions during resolution.

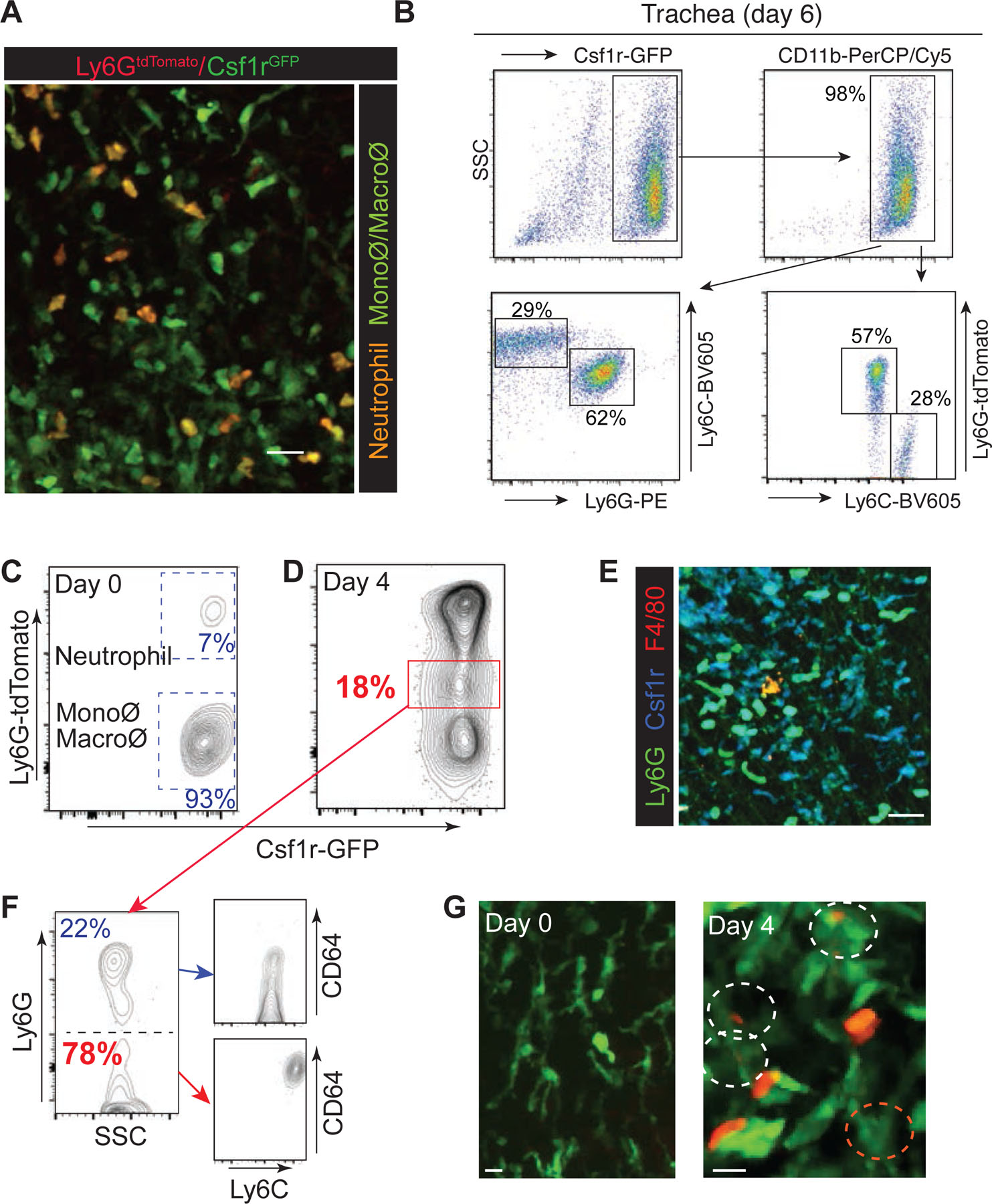

Despite recent advances in studies concerning phagocytic removal of apoptotic cells, visualization of the dynamic cell clearance process in peripheral tissues in vivo has been challenging. To simultaneously image both neutrophils and tissue-resident monocytes/macrophages in live mice, we generated Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice, in which neutrophils express both tdTomato and GFP (orange), while monocytes and macrophages express only GFP (green) (Fig. 2a). In Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice, the majority of GFPpos cells in the influenza infected trachea are CD11b+Ly6GhitdTomatopos neutrophils (62 – 57%) and CD11b+Ly6ChitdTomatoneg monocytes (29 – 28%) (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, we confirmed the presence of GFPdimtdTomatonegCD3negCD19+ B cells in the blood of Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice (Extended Data Fig. 1f), but these cells were not detected in the trachea.

Fig. 2. Simultaneous visualization of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in the influenza-infected trachea of Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice.

(a) Tracheal imaging of Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice. Monocyte/macrophage: Green; neutrophil: Orange. Bar, 25 µm. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of GFP- and/or tdTomato-positive cells in the influenza infected trachea of Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice. (c) & (d) Tracheal cells (day 0 and day 4 post- HKx31 infection) from Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. (e) The trachea of Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice (day 6 post-infection) was fixed and imaged using IV-MPM. F4/80 staining is indicated in red. The scale bar represents 25 μm. (f) Ly6G-tdTomatomid/Csf1r-GFP+ cells (red box in (d)) were sorted and stained for cell surface expression of Ly6G, Ly6C, and CD64. (g) IV-MPM images of the trachea of Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice (day 0 and day 4 post-infection).

Flow cytometry and IV-MPM analysis of our Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice in the steady state showed a tissue-resident macrophage population (Ly6G-tdTomato−/Csf1r-GFP+; Fig. 2c and 2g_left and Supplementary Movie 4) and a small number of neutrophils (Ly6G-tdTomato+/Csf1r-GFP+; Fig. 2c) in the trachea. Examination of the tracheal tissue on day 4 post-infection showed noticeable increases in both neutrophil and monocyte populations (Fig. 2d). During the active infection (day 6), macrophages (tdTomatoneg/Csf1r-GFP+/F4/80+) only accounted for a minor population in the trachea (~25,000 of monocytes vs. ~1,500 of macrophages; Fig. 1a & Fig. 2e). Analysis of the tracheal tissue further revealed the appearance of a new population of cells with a Ly6G-tdTomatomid/Csf1r-GFP+ phenotype during the infection (Fig. 2d: red box). Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface markers indicated that the majority of these cells were tdTomatomid/Ly6G−/Ly6C+/CD64+ monocytes (~ 80%) (Fig. 2f). Subsequently, IV-MPM and confocal imaging of the tdTomatomid/Ly6G−/Ly6C+/CD64+ monocytes demonstrated that these cells were mainly inflammatory monocytes that had taken up tdTomato protein from neutrophils likely via direct phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils or the uptake of cellular components from necrotic cell bodies (Fig. 2g_right, and Supplementary Movie 5 & 6). In vitro co-culture assays of Csf1r-GFP+ monocytes and tdTomato+ neutrophils further confirmed the presence of GFP+ monocytes with engulfed intracellular red fluorescence signals (Extended Data Fig. 2a and Supplementary Movie 5). Consistent with previous reports11–13, our study showed that the absence of monocyte infiltration in CCR2 knockout (KO) mice led to a significant delay in the clearance of apoptotic neutrophils in the influenza-infected trachea (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Therefore, our data suggest that, in addition to other tissue-resident phagocytes (e.g., tissue-resident macrophages, DCs, and non-professional phagocytes)14, monocytes play an important role in the clearance of dead neutrophils in the influenza-infected trachea.

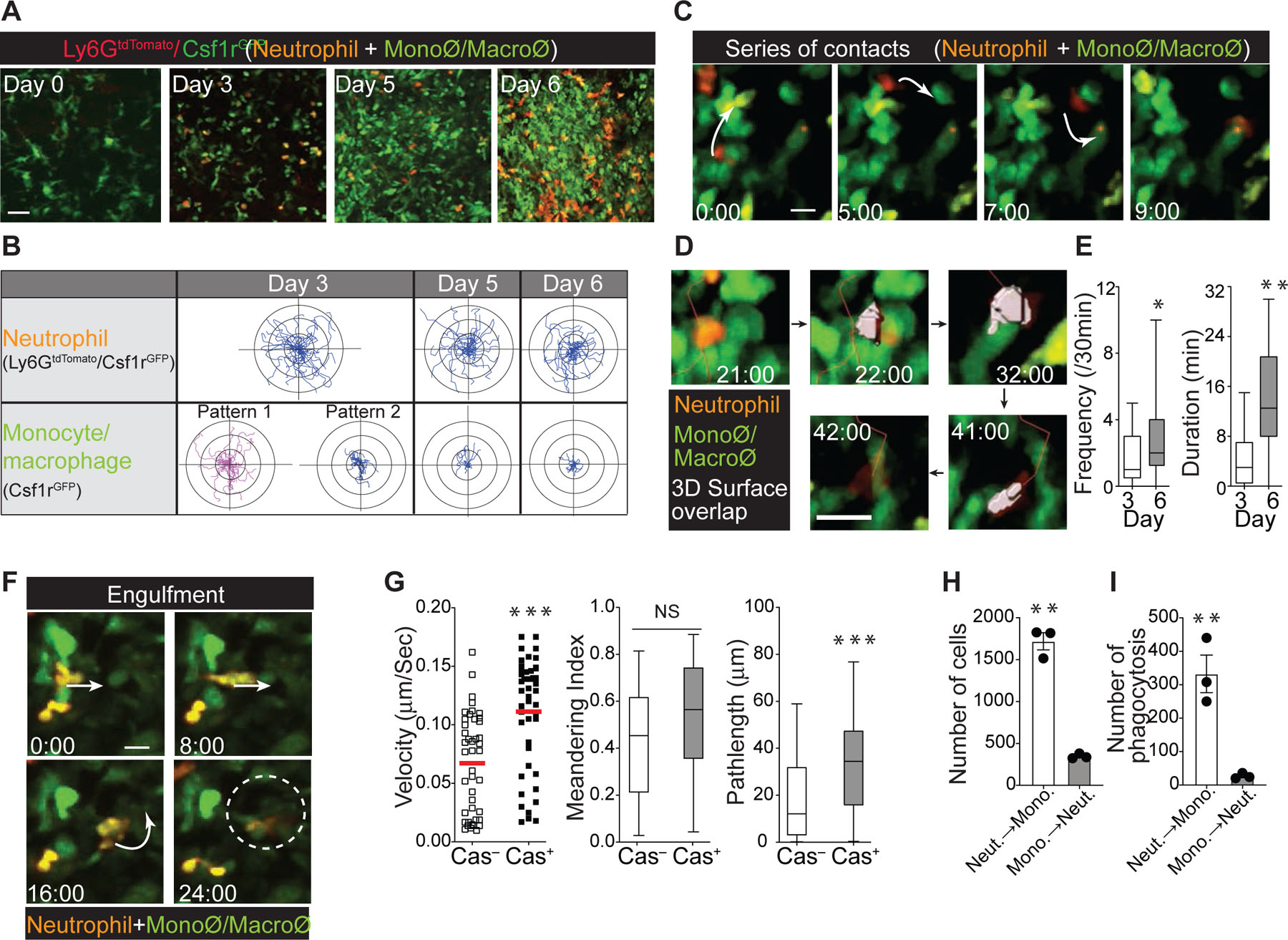

To examine the dynamics of neutrophil and monocyte/macrophage interactions in vivo in the influenza-infected trachea, we infected Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice with HKx31 virus. On day 3 post-infection, we found a large number of tdTomato and GFP double-positive (Ly6G-tdTomato+/Csf1r-GFP+) neutrophils actively migrating throughout the trachea (Fig. 3a and 3b and Supplementary Movie 7). The migration profile of tdTomato-negative and GFP-positive cells (Ly6G-tdTomato−/Csf1r-GFP+) revealed two distinct motility patterns suggesting the presence of highly motile inflammatory monocytes (Pattern 1: red) and non-migratory tissue-resident macrophages (Pattern 2: blue) (Fig. 3b; Day 3 and Supplementary Movie 7) during the early infection period. As a substantial number of inflammatory monocytes accumulated in the infected trachea on days 5 – 6 post-infection, the majority of Ly6G-tdTomato−/Csf1r-GFP+ cells became non-motile, showing a morphology similar to that of tissue-resident macrophages (Fig. 3b; Day 5 & 6, and Supplementary Movie 8 (day 5) & 9 (day 6)). Note that the majority of non-motile Csf1r-GFP+ cells on day 6 post-infection were monocytes, while macrophages were sparsely distributed in the infected trachea and only accounted for a minor population (Fig. 1a & Fig. 2e). The majority of neutrophils (Ly6G-tdTomato+/Csf1r-GFP+), however, remained highly motile (Fig. 3b, and Supplementary Movie 8 (day 5) & 9 (day 6)), constantly moving in close proximity to the surrounding monocytes/macrophages (Csf1r-GFP+) (Fig. 3c – e, and Supplementary Movie 10). After tracking hundreds of neutrophils, we observed very few stationary neutrophils. Flow cytometry analysis and in vivo imaging confirmed that the highly motile neutrophils during the resolution phase were newly recruited cells in each imaging session due to tissue injury (Fig. 2c & 2d and Supplementary Movie 1, 8, & 9).

Fig. 3. Visualizing dynamic neutrophil-phagocyte interactions during the resolution of infection.

(a) IV-MPM of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in the live trachea on the indicated days post-infection. Scale bar, 25 µm. (b) Migratory paths of the neutrophils (Ly6GtdTomato/Csf1rGFP) and monocytes/macrophages (Csf1rGFP) in the influenza-infected trachea over a 30-minute period in mice (presented as x-y projections). A total of 30 cells from three independent assays. (c) IV-MPM images showing serial interactions between neutrophils (orange) and monocytes/macrophages (green). Scale bar, 10 µm. (d) Unbiased 3D computational analysis of neutrophil-monocyte/macrophage interactions. The neutrophil is shown in gray at the moment of contact with the monocyte/macrophage. Scale bar, 10 µm. (e) The interaction frequency (over a 30-minute period) between neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages and duration (minutes) on day 3 and day 6 post-infection (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3 mice per group). Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney test. (f) IV-MPM images showing the engulfment of a neutrophil (orange) by a phagocyte (green). Scale bar, 10 µm. (g) In vitro migration of early apoptotic neutrophils. Spontaneous apoptosis of BM-purified neutrophils was induced and the cells undergoing apoptosis (Cas+) or not (Cas−) were sorted after staining with Alexa 660-conjugated Z-VAD-FMK. Sorted neutrophils were allowed to migrate on ICAM-1 coated glass. The mean velocity, displacement, and meandering index of the neutrophils are shown. n = 3 per group. Statistical differences were assessed by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. (h) & (i) Migration of early apoptotic neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+Cas+ stained with violet fluorescence) or monocytes through a transwell insert (3 μm pore size) toward monocytes or apoptotic neutrophils in the bottom chamber, respectively (h) and subsequent phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils (the number of Violet+Ly6G−GFP+ monocytes) (i). n = 3 per group. Statistical differences were assessed by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001,***P <0.0001).

Importantly, the majority of stable phagocytic interactions formed when migrating neutrophils arrested at the sessile target monocytes/macrophages (Csf1r-GFP+) (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Movie 11, Example #1), and we detected only a small number of monocytes/macrophages that actively migrated toward neutrophils (Supplementary Movie 11, Example #2). Our data suggest that, unlike the late apoptotic cells (that have lost membrane integrity with a necrotic morphotype), the directional migration of an early apoptotic neutrophil continues until it completes the apoptotic process and encounters a target phagocyte (“find-your-phagocyte”)15. Therefore, the active migration of neutrophils toward phagocytes during apoptosis may be the primary means of removing dying neutrophils from the infected airway. To further test this concept, early apoptotic neutrophils (live with intact membrane integrity) were sorted after staining with Alexa 660-conjugated Z-VAD-FMK78 (CD11b+Ly6G+Cas+). Consistent with IV-MPM data, our in vitro migration assay confirmed the enhanced cell migration of early apoptotic neutrophils (Fig. 3g and Annexin V+ neutrophils in Extended Data Fig. 3a). To further dissect this, we performed a transwell assay. Early apoptotic neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+Cas+) or monocytes were placed in the upper chamber and then incubated with monocytes or apoptotic neutrophils in the bottom chamber, respectively. After the onset of migration, the early apoptotic neutrophils in the upper chamber moved toward the monocytes in the bottom chamber, resulting in significant phagocytosis, whereas the monocytes placed in the upper chamber were less responsive, with minimum migration followed by insignificant phagocytosis events (Fig. 3h & 3i).

Our finding that actively migrating neutrophils make multiple transient close interactions with phagocytes before being cleared suggests that these tissue-resident myeloid cells are a major source of chemokines that mediate early apoptotic neutrophil migration and serial cell-cell interactions. To examine chemokine production by phagocytes, we first screened 19 mouse chemokines and detected 10 chemokines in monocyte lysates prepared from influenza-infected mice on day 5 post-infection (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Neutrophils from infected mice expressed receptors that recognize at least 6 of these detected chemokines (CXCL10, CXCL9, CXCL2, CCL6, CCL21, and CCL19; Extended Data Fig. 3b)16–22. Among the six chemokines tested for their effects on neutrophil migration, only CXCL2 significantly induced cell migration in early apoptotic neutrophils in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 3c), suggesting that the apoptotic neutrophil-monocyte interaction during influenza infection is at least partly dependent on CXCL2 signaling.

In situ efferocytosis of neutrophils regulates DC differentiation of inflammatory monocytes.

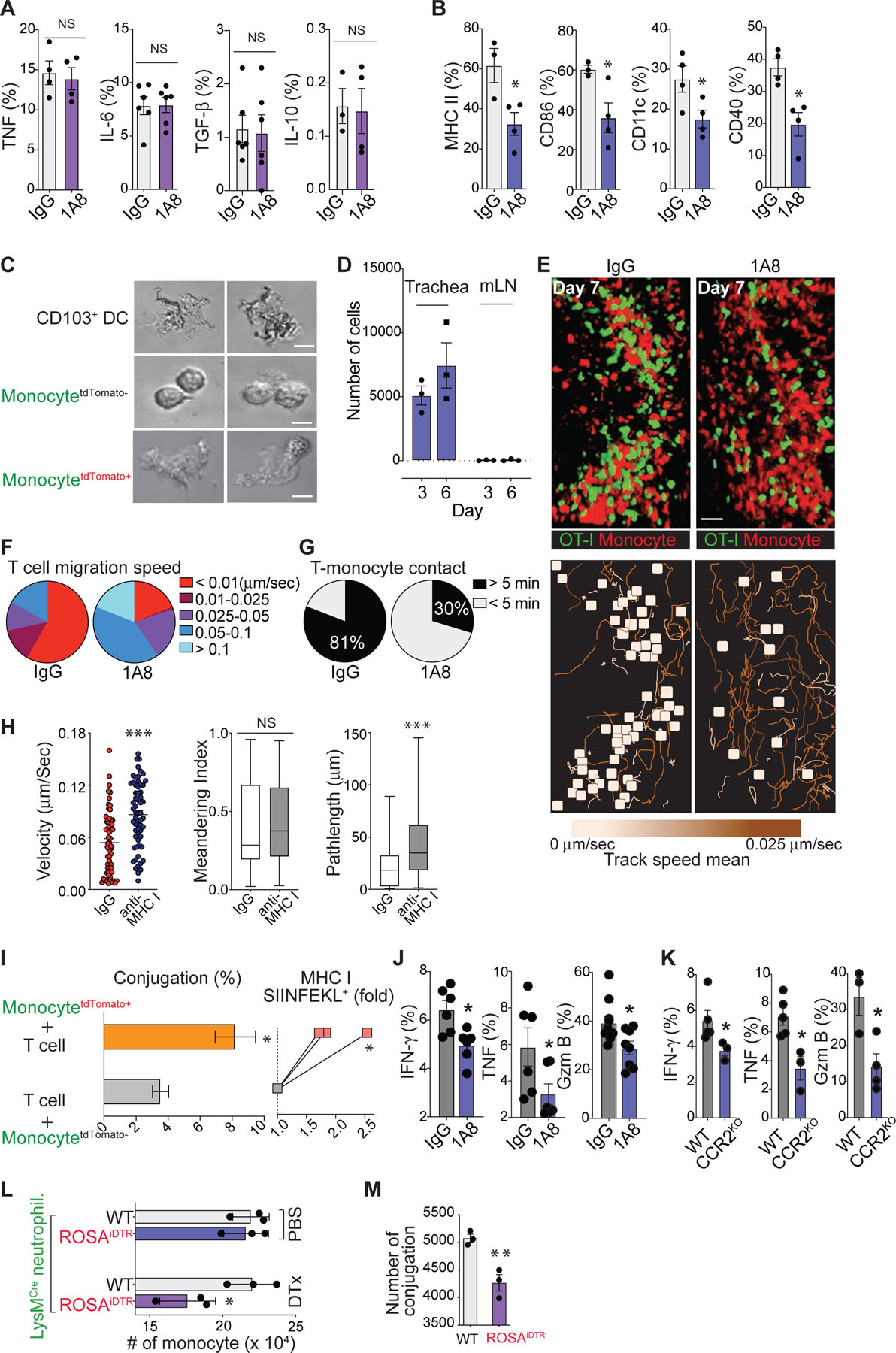

After clearing apoptotic neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes and tissue-resident macrophages often initiate a feed-forward pro-resolution program by releasing tissue-repairing cytokines, such as TGFβ and IL-1023,24. Based on the fact that the number of newly recruited monocytes greatly exceeds the population of tissue-resident macrophages during the resolution of neutrophil responses, we hypothesized that Ly6C+/CD64+ inflammatory monocytes, particularly those closely interacting with apoptotic neutrophils (Fig. 2e – g), become the main source of anti-inflammatory mediators and that these monocytes regulate tissue repair and the resolution of inflammation. However, neutrophil depletion during influenza infection (Extended Data Fig. 4a) did not significantly change cytokine production (both pro- and anti-inflammatory) by monocytes (Fig. 4a). Unexpectedly, examination of monocyte cell surface markers on day 6 post-infection revealed that the depletion of neutrophils during infection elicited a significant decrease in the expression of DC differentiation/maturation markers on monocytes25,26 (Fig. 4b). Neutrophil depletion had a minimal impact on the local abundance of monocytes in the influenza-infected trachea, suggesting that the significant change in monocyte differentiation marker expression after neutrophil depletion was not due to changes in monocyte populations (Extended Data Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. Neutrophils promote the differentiation of inflammatory monocytes into antigen-presenting cells for potent CD8+ T cell activation.

(a) & (b) Flow cytometry analysis of the cytokine production (a) and cell surface expression of DC maturation markers (b) by monocytes in the trachea of normal and neutropenic mice. (c) Morphology of lung DCs and monocytes (tdTomato+ vs. tdTomato−). (d) Numbers of tdTomato+ monocytes from the dLN and trachea of virus-infected mice. (e) (Top) Representative IV-MPM images of OT-I GFP CD8+ T cells in virus-infected CCR2RFP/+ mouse trachea. Scale bar, 25 µm. (Bottom) Color-coded cell tracks of the OVA-specific CD8+ T cells display the mean track velocity. The brown tracks correspond to higher track velocities, and the yellow squares show cell tracks < 5 µm/30 min. (f) Relative proportions of T cells with different migration speeds. (g) Individual OT-I T cells were assessed for their interactions with CCR2+ cells with or without neutrophil depletion (black: > 5 min, white: < 5 min). (h) Interaction of OT-I T cells with CCR2+ cells after iv injection of MHC I blocking or isotype control IgG. All data in this figure are representative of two independent experiments and the mean ± SEM for each group is depicted with horizontal black lines. (i) (Left) Conjugation of OT-I CD8+ T cells with monocytes (tdTomato+ vs. tdTomato−). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3 mice per group. (Right) SIINFEKL/H-2kb expression on the Ly6C+ monocytes (tdTomato+ vs. tdTomato−) was determined by flow cytometry. (j) & (k) Flow cytometry analysis of the production of IFN-γ, TNF, and Granzyme B (Gzm B) in CD8+ T cells on day 7 post-infection from normal vs. neutropenic (j) or from WT vs. CCR2 KO influenza-infected mice (k). (l) Numbers of CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G− monocyte-derived cells from the peritoneum of WT or ROSA-iDTR mice that were administered thioglycollate and LysMCre neutrophils, together with DTx or PBS (day 4). (m) Conjugations of OVA peptide pulsed monocytes with OT-1 CD8+ T cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical differences were assessed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01,***P < 0.0001).

When antigen-specific T effector cells enter the infected tissue, they must first locate antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to restimulate their effector functions27–32. Growing evidence suggests that CCR2+Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes are recruited to inflammatory sites, acquire a strong capacity to efferocytose apoptotic cells, and become important APCs by cross-presenting antigens to CD8+ T cells33–38, which is a functional property that is particularly attributed to Batf3+ conventional DC1s (cDC1s)39–42. Morphologically, monocytes with signs of phagocytic interactions with neutrophils (neutrophil-experienced; tdTomato+/Ly6C+/CD64+) exhibited large cytoplasms characteristic of CD103+ DCs43, whereas non-experienced (tdTomato−/Ly6C+/CD64+) cells showed a typical small monocyte-like shape with smooth membranes (Fig. 4c). The majority of tdTomato+/Ly6C+/CD64+ monocytes accumulated at the infected tissue site without significant lymphatic draining, suggesting that these cells do not actively migrate to the dLN (Fig. 4d).

Based on our findings that the newly recruited inflammatory monocytes are a major myeloid pool in the influenza-infected trachea and that the presence of neutrophils in the infection site is key for DC-differentiation of the inflammatory monocytes, we hypothesized that apoptotic neutrophil-experienced Ly6C+/CD64+ inflammatory monocytes differentiate into an important pool of tissue-resident APCs that can promote T cell effector functions. To test our hypothesis, we first examined the dynamic interaction between influenza-specific CD8+ T cells and inflammatory monocytes in the trachea. Splenocytes from a transgenic mouse that produces naïve GFP–expressing OT-I T cells were transferred into CCR2RFP mice, which express red fluorescence protein (RFP) in Ly6Chi monocytes44. We then infected the mice with HKx31-OVA virus and performed IV-MPM on the surgically cannulated live trachea. On day 7 post-infection, newly infiltrated RFP+ monocytes formed clusters in the trachea and a large number of GFP-positive OT-I CD8+ T cells showed dramatically reduced migration velocity and stably interacted with RFP+ monocytes for a prolonged period of time (> 5 min and often more than 30 min) (Fig. 4e – 4g and Supplementary Movie 12), suggesting that T cells arrested their motility by forming stable immunological synapses with RFP+ monocytes45. In stark contrast, upon neutrophil depletion we found that only a few CD8+ T cells made stable contacts with RFP+ monocytes and that the movement of CD8+ T cells occurred at an increased mean velocity in apparently random patterns (Fig. 4e – 4g and Supplementary Movie 12). We further explored the MHC I dependence of the stable engagements between CD8+ T cells and RFP+ monocytes by measuring T cell motility parameters in the presence of an MHC I blocking antibody46. Inhibition of MHC I interactions increased mean track velocities and path lengths for CD8+ T cells that contacted RFP+ monocytes in the influenza-infected trachea (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Movie 12). These data demonstrate that the interactions between CD8+ T cells and RFP+ monocytes are MHC I dependent. An in vitro cell-cell conjugation assay further showed that neutrophil depletion led to a reduced frequency in conjugation between RFP+ monocytes and GFP-positive OT-I CD8+ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 4c). To confirm that neutrophil-experienced Ly6C+/CD64+ inflammatory monocytes become important APCs for CD8+ T cell activation by inducing more stable T:APC conjugates, we isolated neutrophil-experienced (tdTomato+/Ly6C+/CD64+) and non-experienced (tdTomato–/Ly6C+/CD64+) monocytes from Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice infected with HKx31-OVA virus (Fig. 2d & 2f). An in vitro cell-cell conjugation assay with OT-I CD8+ T cells revealed that phagocytic interactions with neutrophils led to an increased frequency of conjugates (Fig. 4i, left). This effect was associated with increased amounts of cognate peptide class I complexes expressed by neutrophil-experienced monocytes (Fig. 4i, right). These significant changes in the CD8+ T cell-monocyte interaction suggest that the stable interactions between effector T cells and monocyte-derived, tissue-resident APCs in the trachea must be governed by the presence of neutrophils during infection. Indeed, neutrophil depletion during the primary infection of mice caused reduced production of IFN-γ, TNF and granzyme B (Gzm B) by influenza A virus-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4j). Furthermore, cytokine production in virus-specific CD8+ T cells was decreased in CCR2 KO mice (Fig. 4k), while similar numbers of total virus-specific CD8+ T cells were recovered from the dLN and trachea of WT vs. CCR2 KO mice during the primary infection (Extended Data Fig. 4d). These results suggest that the absence of inflammatory monocytes reduces the magnitude of influenza-specific CD8+ T cell activation in the target tissue site (trachea) without altering T cell priming and expansion in the dLN.

To clearly define the biological implications of newly recruited inflammatory monocytes, we performed additional experiments with CCR2 depleter mice that express a functional diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) under the control of the CCR2 promoter. Following diphtheria toxin (DTx) administration, > 80% of monocytes were ablated in the influenza infected trachea (Extended Data Fig. 4e). Consistent with previous experiments using CCR2 KO mice (Fig. 4k), acute depletion of CCR2+ inflammatory monocytes caused a significant decrease in cytokine production by virus-specific CD8+ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 4f), which suggests that the absence of newly recruited inflammatory monocytes during the infection reduces the magnitude of influenza-specific CD8+ T cell activation in the target tissue site. To further support this finding, we performed additional experiments to assess the involvement of neutrophil-experienced monocytes (e.g. tdTomato+/Ly6C+/CD64+ in Fig. 2d – 2g) in mediating T cell activation at tissue sites. In this study, we used ROSA-iDTR mice (instead of ROSAtdTomato mice (Fig. 1f)). When ROSA-iDTR phagocytes engulf Cre+ neutrophils, the STOP sequence is deleted in the phagocyte, and thus, DTR is expressed, rendering the cells susceptible to ablation following the administration of DTx. Selective elimination of apoptotic neutrophil (Cre+)-engulfing ROSA-iDTR+ cells in the inflamed tissue significantly decreased monocyte-derived, tissue-resident APCs (Fig. 4l), leading to diminished monocyte-T cell conjugations (Fig. 4m).

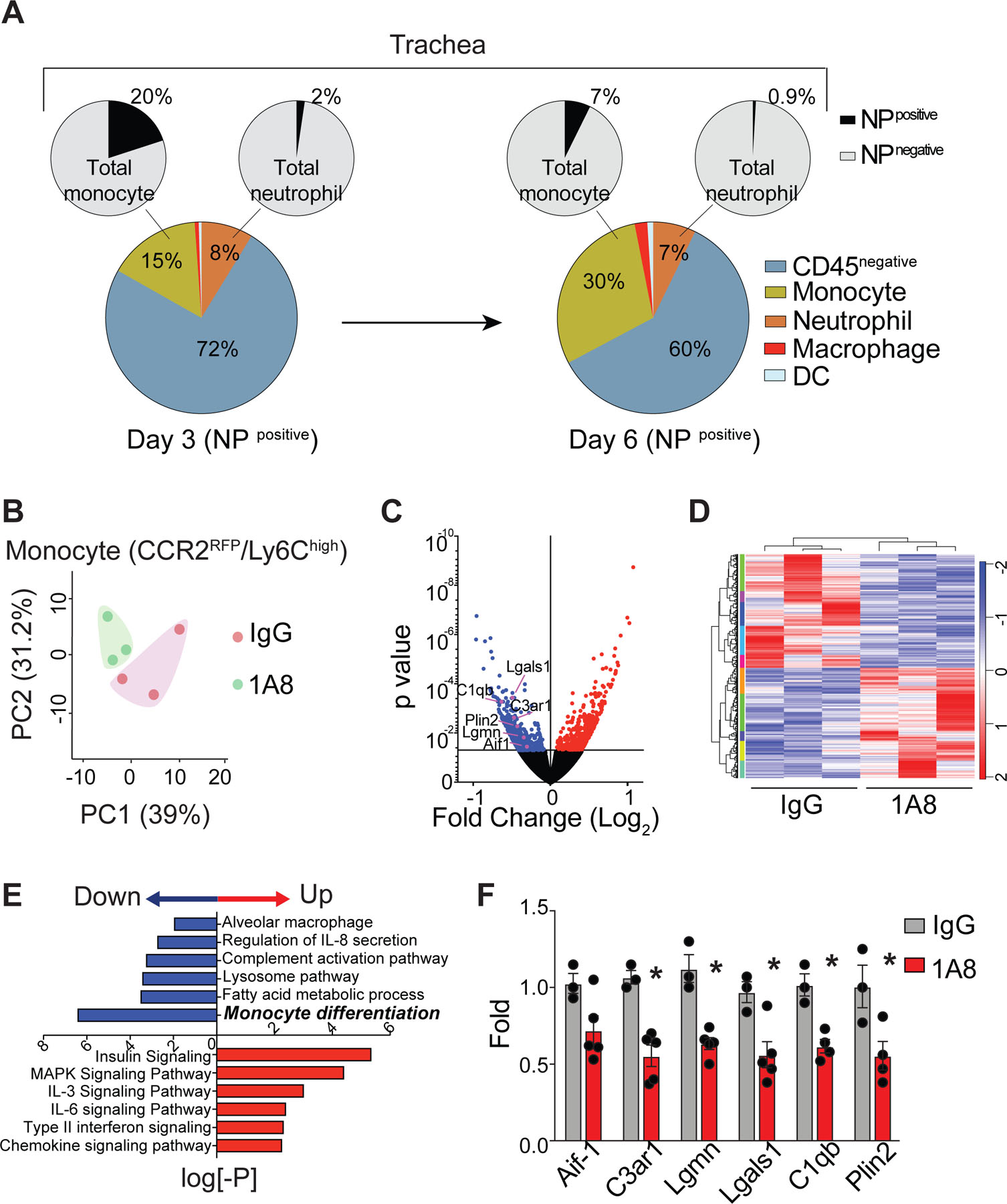

Although it is well established that influenza virus infection is initiated in the respiratory tract, the cell types that become infected or access viral antigens remain incompletely understood. Different cell types that can access influenza antigen (via infection and/or protein uptake) during infection were further analyzed by expression of the viral nucleoprotein (NP) (Fig. 5a). Consistent with previous studies47, flow cytometry analysis revealed that the majority of NPpos cells in the trachea were CD45neg (day 3; 72 ± 3%, day6; 60 ± 8%). In addition, monocytes accounted for the majority of NPpos/CD45pos cells at day 3 post-infection and the frequency increased over time (day 3; 15 ± 6% → day6; 30 ± 3%). Neutrophils were the second largest NPpos/CD45pos cell population, but they represented only a very small fraction of the total neutrophils in the infected trachea (day 3; 2.0 ± 0.5%, day6; 0.9 ± 0.5%). Our data suggest that non-hematopoietic cells, such as epithelial cells lining the airways, serve as the major target cells of influenza infection and that monocytes account for the prominent myeloid cell type that gains access to the viral antigen at the tissue site. Due to the low frequency and number of NPpos neutrophils, it is unlikely that monocytes gain access to virus antigens via phagocytosis of neutrophils (that are either directly infected or have ingested viral material), but we cannot completely exclude the possibility.

Fig. 5. Transcriptional analysis of the effects of neutrophil efferocytosis on the monocyte differentiation into antigen-presenting cells.

(a) Distribution of virus antigen-bearing (NPpos) cells in the trachea following infection (Days 3 & 6). Pie charts represent a composite of two independent experiments, with responses pooled from 5 mice per group. (b) Principal component (PC) analysis of differentially expressed genes in monocytes isolated from the trachea of normal and neutropenic mice on day 6 after influenza infection. (c) Comparison of differentially expressed genes in monocytes (normal vs. neutropenic mice). Red denotes increased genes, and blue denotes decreased genes in neutropenic monocytes relative to normal monocytes. (d) Heatmap of gene expression among the top 1,077 most differentially expressed genes (z-score). (e) Differentially expressed genes in neutropenic monocytes relative to normal monocytes were analyzed and pathway enrichment is expressed as the log[–P]. (f) Expression of the indicated genes (marked in (c)) in monocytes by qRT-PCR (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3). Statistical differences were assessed by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. (*P < 0.01).

We next sought to define the impact of the presence of neutrophils on the transcriptional signature of monocytes. Principal component analysis revealed clear transcriptional differences in monocytes from mice after neutrophil depletion and a volcano plot showed the changes in specific genes (Fig. 5b & 5c). Among the 53,736 genes identified, 1,077 were differentially expressed in monocytes after neutrophil depletion (Fig. 5d). Pathway analysis revealed that the absence of neutrophils led to a significant downregulation of genes related to monocyte differentiation (Fig. 5e). Of those, we further validated robust downregulation of several key DC functional genes by qRT-PCR (Fig. 5f).

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) released from apoptotic neutrophils promotes monocyte differentiation.

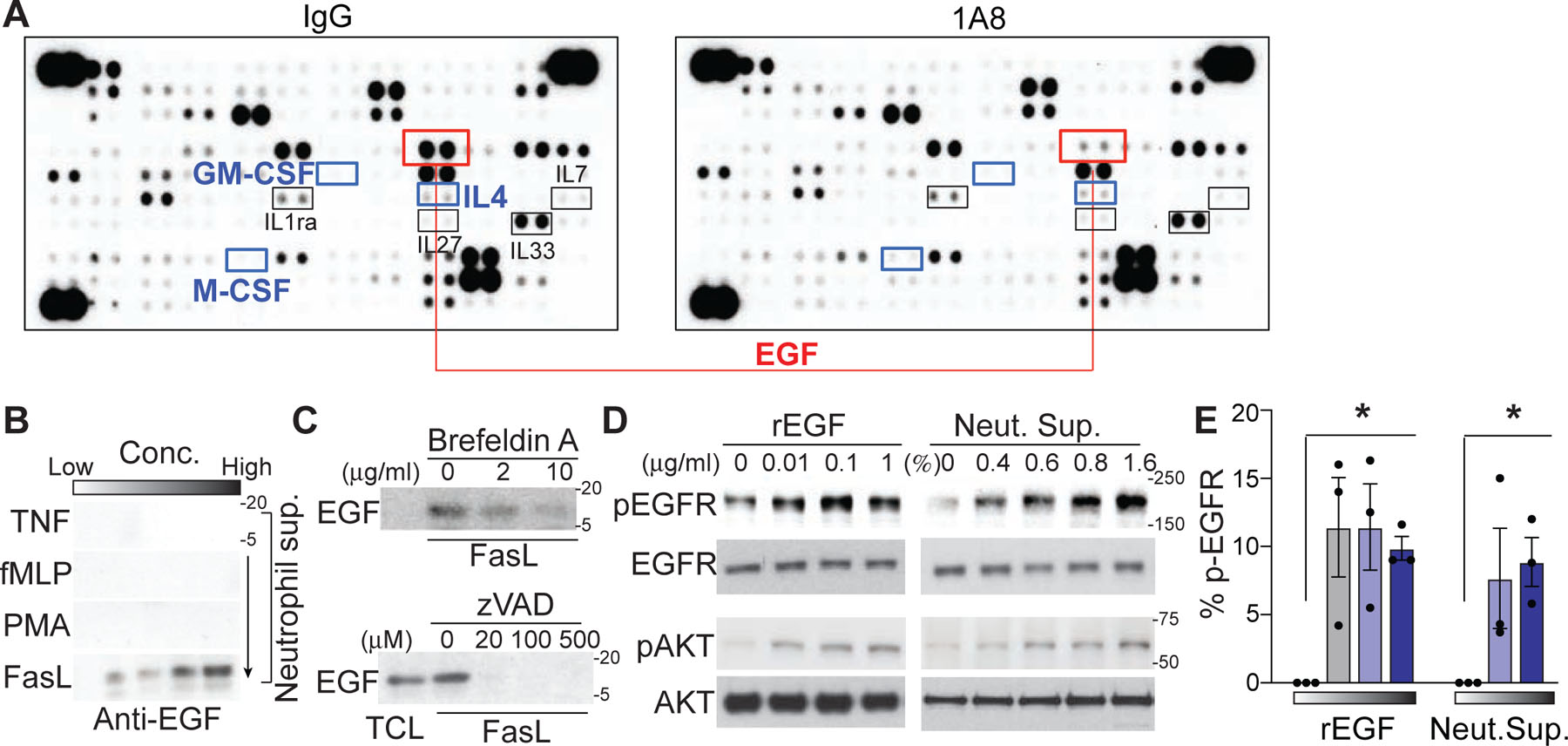

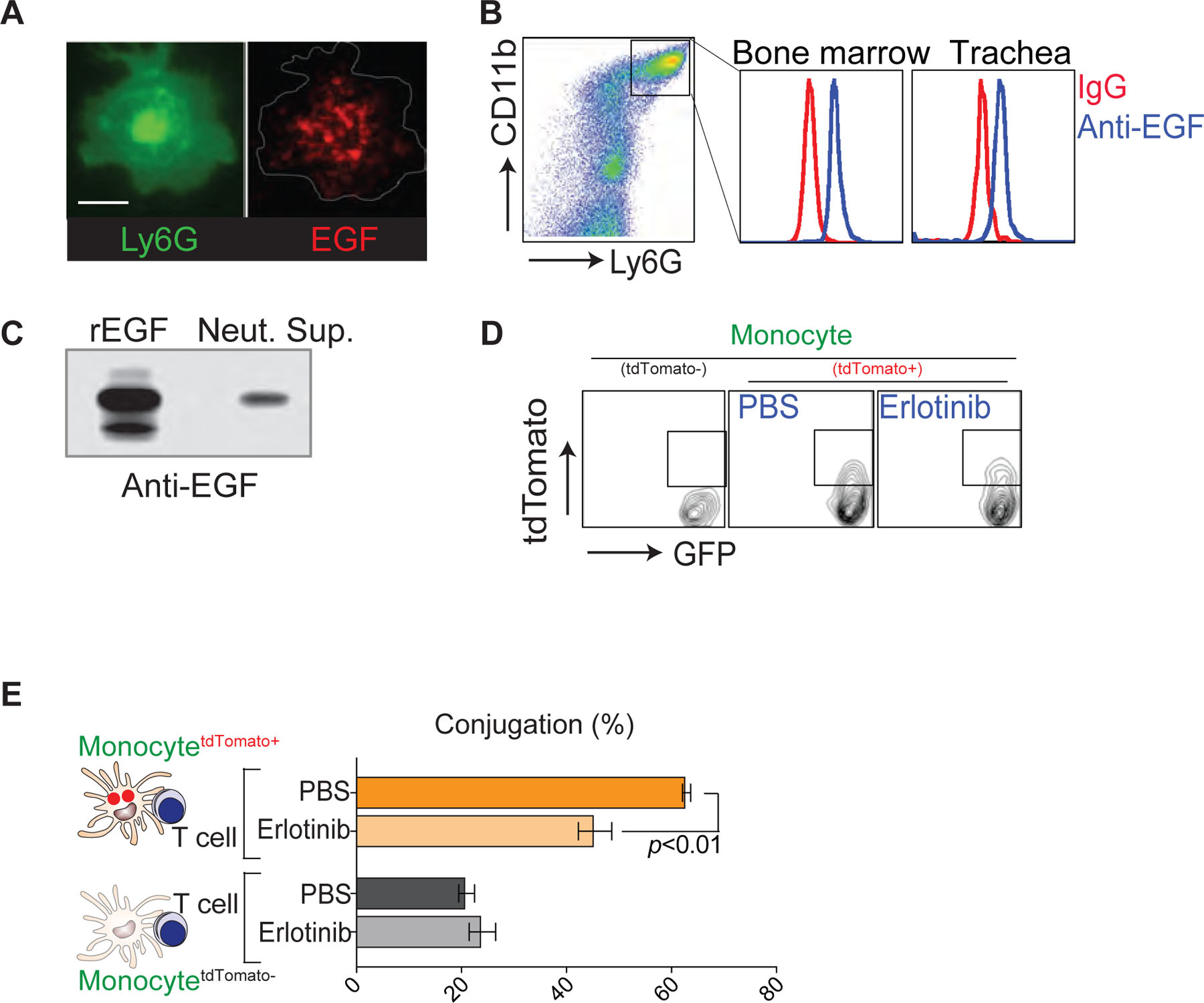

It is well established that GM-CSF, M-CSF, and IL-4 are key cytokines that induce monocyte differentiation into DCs in the context of inflammation48. Therefore, we used a mouse cytokine/growth factor antibody array to determine whether neutrophils regulate the release of these cytokines to promote monocyte differentiation in tracheal tissues. In contrast to our prediction, we failed to detect significant expression of GM-CSF and M-CSF in the infected trachea with or without neutrophil depletion (Fig. 6a). There was a detectable IL-4 signal, but the expression level did not change after neutrophil depletion. Unexpectedly, among the more than 120 proteins that were screened, only the expression of epidermal growth factor (EGF) in the infected tissue was abolished after neutrophil depletion (Fig. 6a). Flow cytometry and immunohistological examination of mouse neutrophils confirmed that EGF was stored within intracellular vesicles (Extended Data Fig. 5a and 5b). Surprisingly, even with high concentrations of inflammatory stimuli that induce neutrophil degranulation such as PMA, TNF or fMLP, we failed to detect a significant release of soluble EGF from neutrophils, whereas total neutrophil lysates contained significant amounts of EGF that were detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6b). To screen for potential stimulators that trigger EGF release from neutrophils, we next turned our attention to neutrophil apoptosis. Surprisingly, the secretion of EGF was most significantly enhanced after the induction of neutrophil apoptosis with Fas ligand (FasL) (Fig. 6b). EGF release was further confirmed during spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis49 (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Pretreatment of apoptotic neutrophils with brefeldin A (Fig. 6c) and the inhibition of FasL-induced neutrophil apoptosis with the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk (Fig. 6c) abolished EGF release into the neutrophil culture supernatant, suggesting that the secretion of EGF from neutrophils depends on caspase-mediated cell apoptosis. Importantly, in vitro co-culture assays showed that EGF released from apoptotic neutrophils was sufficient to activate EGF signaling in both mouse primary epithelial cells (Fig. 6d) and monocytes (Fig. 6e).

Fig. 6. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) derived from apoptotic neutrophils promotes the differentiation of inflammatory monocytes into antigen-presenting cells.

(a) A cytokine/growth factor antibody microarray was performed with lysates of the influenza-infected (day 4) trachea after neutrophil depletion (1A8). IgG: isotype-treated group. The signals at the three corners are loading controls. (b) EGF secretion by neutrophils in response to TNF (2–200 ng/ml), fMLP (0.1–10 μM), PMA (1–100 nM) or FasL (1 −100 ng/ml) stimulation was determined by Western blot analysis of neutrophil supernatants with an EGF-specific antibody. Each panel shows one representative image of three replicated experiments. (c) FasL-induced EGF secretion in the presence of Brefeldin A or z-VAD-fmk. TCL; total cell lysate. (d) Western blot analysis of EGFR activation (phospho-EGFR; pEGFR) and its downstream signaling protein AKT (phospho-AKT; pAKT) in mouse primary lung epithelial cells treated with increasing concentrations of recombinant EGF (rEGF) or apoptotic neutrophil supernatant. One representative image of three repeated experiments is shown. (e) Flow cytometric analysis of EGFR activation (anti-p-EGFR) in permeabilized monocytes after treatments with increasing concentrations of rEGF or apoptotic neutrophil supernatant. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice per group. Statistical differences of rEGF vs. PBS treatment were assessed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. (*P < 0.01).

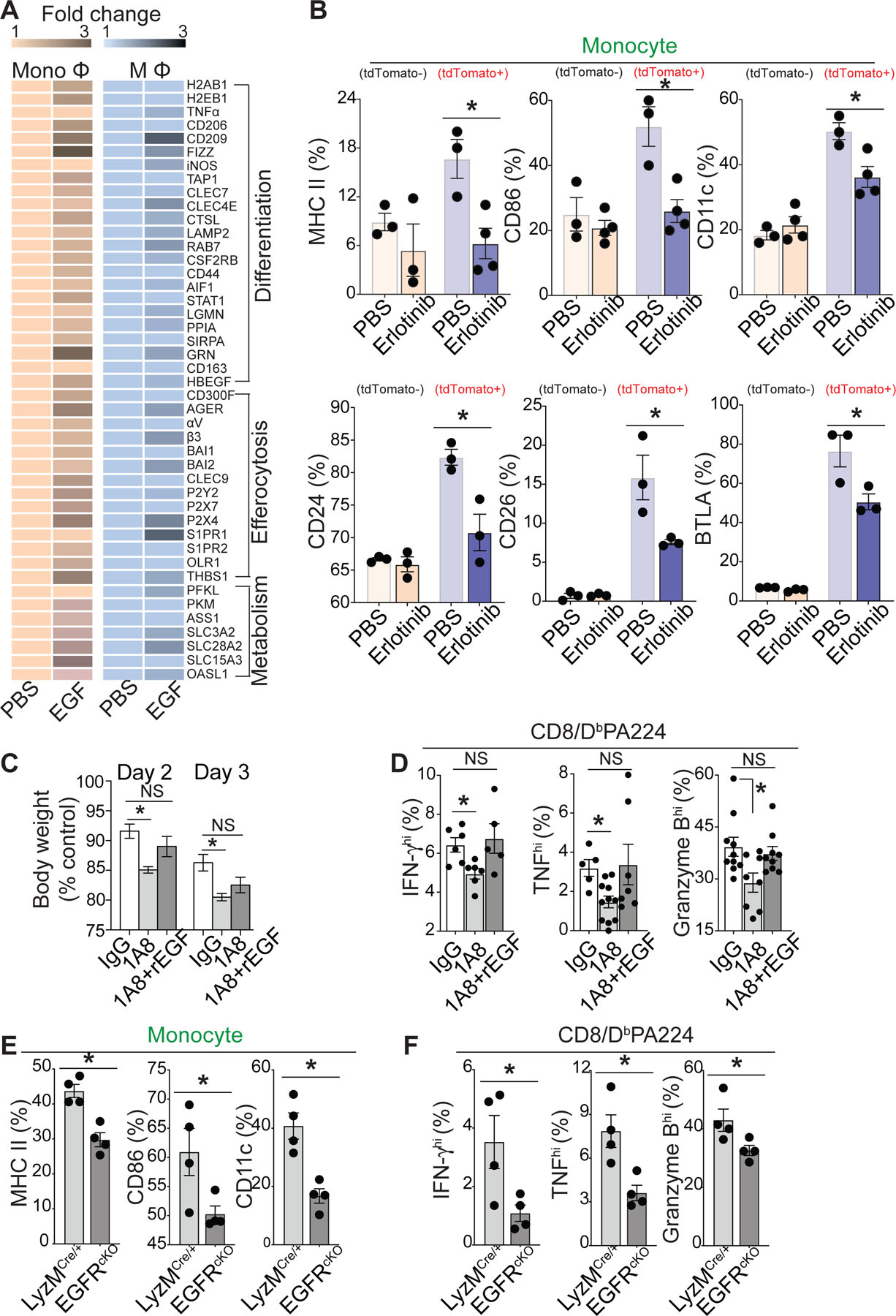

Our data support the idea that neutrophils continue to migrate at high speed and make multiple transient contacts with monocytes until they form a stable conjugate with a phagocyte (Fig. 3). If the initial transient interaction between a neutrophil and monocyte plays a key role in monocyte differentiation, conceptually it may be possible that cell maturation/differentiation signals are delivered from migrating (and apoptosing) neutrophils to the potential phagocytes during the initial phase of brief interactions and that these signals accumulate in phagocytes until they fully differentiate. qRT-PCR analyses of monocytes and macrophages further revealed that stimulation with EGF induced 2- to 4-fold changes in the expression of several genes associated with cell differentiation, efferocytosis, and metabolism (Fig. 7a). Importantly, we observed a significant increase in the expression of DC differentiation/maturation markers on neutrophil-experienced monocytes (tdTomato+) compared with that of non-experienced monocytes (TdTomato−), which was significantly reduced by the EGF receptor inhibitor, erlotinib (Fig. 7b) without any changes in phagocytic activity (Extended Data Fig. 5d). In addition, erlotinib treatment significantly reduced the frequency of conjugate formation between neutrophil-engulfed monocytes (tdTomato+/Ly6C+/CD64+) and CD8+ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 5e).

Fig. 7. EGF released from apoptotic neutrophils promotes T cell effector functions.

(a) An expression heat map (qRT-PCR) showing the candidate gene expression in monocytes (CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−) and macrophages (F4/80+Ly6C−) sorted from influenza-infected lungs on day 4 post-infection with/without 1 μg/ml rEGF stimulation for 12 h. Data represent average fold change values (n = 3, p <0.05). (b) Flow cytometry analysis of the cell surface expression of DC maturation markers on monocytes (Csf1r-GFP+Ly6C+Ly6G−) isolated from the influenza infected lung of Csf1r-EGFP mice after co-incubation with tdTomato+ apoptotic neutrophils for 12 h in the presence of PBS or erlotinib (0.1 μg/ml). (c) Neutrophils were depleted with/without recombinant EGF (rEGF) injection, and changes in the body weights of the treated mice were measured. Weights are expressed as the mean change from the starting weight, n = 5–7 mice per group. (c) IFN-γhi, TNFhi, or Granzyme Bhi virus-specific (DbPA224) CD8+ T cell numbers in 1A8- or IgG-injected mice with/without rEGF injection were counted by using flow cytometry on day 7 after infection. n = 5–10 mice per group. mean +/− SEM, Statistics; Student’s t test. (e) & (f) Flow cytometry analysis of the cell surface expression of DC maturation markers on monocytes (LysMCre/+ vs. EGFRcKO) (e) and the number of IFN-γhi, TNFhi, or Granzyme Bhi virus-specific (DbPA224) CD8+ T cells (LysMCre/+ vs. EGFRcKO) (f) isolated from the influenza infected lung. n = 4 mice per group. mean +/− SEM, Statistics: Student’s t test. (*P < 0.05).

These findings provide important correlations between neutrophil resolution and tissue-resident APC activation, as apoptotic neutrophils release EGF during their transient interactions with monocytes and promote the differentiation of these monocytes into mature tissue-resident APCs that can subsequently activate T cell effector functions. Consistent with this result, the reduction in mouse body weight (Fig. 7c) and CD8+ T cell cytokine expression (Fig. 7d) after neutrophil depletion were reversed by injection of recombinant EGF. The specific functions of EGF-EGFR signaling in anti-viral host immune responses were further confirmed with EGFR-cKO mice (LysMCre/+/EGFRfl/fl). We observed that the increased expression of DC differentiation/maturation markers on monocytes was significantly reduced in EGFR-cKO mice as compared with that of WT (LysMCre/+) mice (Fig. 7e). Subsequently, CD8+ T cell cytokine expression was also significantly suppressed in EGFR-cKO mice (Fig. 7f). Thus, decreased monocyte differentiation in EGFR-cKO mice was associated with decreased T cell effector functions.

Discussion

Through several lines of evidence in our study using mouse influenza infection models, we showed novel functions of neutrophils that can actively promote the host anti-viral immune response during the resolution of inflammation. Our data suggest that during influenza infection unlike sterile injury or other highly activated inflammatory responses, the disappearance of neutrophils is mediated mainly by in situ efferocytosis in inflamed tissues. Although neutrophil reverse transmigration has been reported, such reverse programming of cellular trafficking during influenza infection is seemingly counterintuitive, as neutrophils are recruited in very large numbers during the early infection phase where they may play a crucial role in the host immunity and tissue repair processes within the target tissue microenvironment. We showed that the resolution of the neutrophil response during infection is not merely a passive termination of early neutrophil infiltrates but rather an active biochemical and cellular process that may benefit the host by providing key resources for effective immune functions, which may point to a novel altruistic function of neutrophils.

Our data suggest that neutrophils are highly motile during the resolution phase. We propose that clearance of apoptotic neutrophils during influenza infection is mediated by two distinct methods—active migration of neutrophils toward phagocytes during early apoptosis and engulfment by phagocytes. Early apoptotic neutrophils may continue to migrate with a high speed until they complete the apoptotic process, which is then followed by the formation of stable conjugation (“phagocytic synapse”) between the late apoptotic neutrophils and phagocytes on day 5 post-infection. The whole procedure is completed by the engulfment of apoptotic neutrophils by phagocytes (by day 6). Importantly, the directional migration of neutrophils during early apoptosis may benefit other cell types by facilitating efferocytosis by phagocytes, while limiting tissue damage caused by premature necrosis (another altruistic trait of apoptotic neutrophils).

Growing evidence from recent outbreaks of respiratory viral infection suggest that the patient lethality is closely linked to both direct viral cytopathicity and inflammation-mediated tissue damage. Thus, the therapeutic strategy to bridle excessive immune damage has been proposed for severe respiratory infections. Here, we showed that, in addition to the reduction in T cell number50, the virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the influenza-infected airway displayed impaired effector cytokine production in the absence of neutrophils without significant changes in CD8+ T cell priming in the secondary lymphoid organs. Importantly, impaired T cell activation and the reduction in mouse body weight during the viral infection were reversed by injection of recombinant EGF. Together, these data strongly suggest that the absence of neutrophils not only impairs the establishment of a sustained CD8+ T cell population at the site of infection through altered CD8+ T cell traffic and localization, but it also greatly diminishes the effector function of the remaining CD8+ T cells by preventing EGF-mediated APC differentiation. Note that our attempt to generate a neutrophil specific EGF cKO mouse by crossing Ly6GCre mice3 with EGFfl/fl mice was unsuccessful.

Much of our understanding of the dynamics of T cell-APC interactions comes from naïve T cell activation in the LN. Currently, the identity of major tissue-resident APCs for T cell activation is not known, but evidence suggests that newly recruited CCR2+Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes become important APCs by cross-presenting antigens to CD8+ T cells 33–38. It was previously shown that multiple inflammatory conditions (e.g. TLRs) differentially enhance the cross-presentation functions of Ly6C+ monocytes to a level similar to that of cDCs26. Our data suggest that, in addition to the pattern recognition signals, EGF released from apoptotic neutrophils is critical for monocyte differentiation and antigen presentation in the inflamed tissue microenvironment to efficiently activate T cell effector function.

Methods

Mice and influenza infection.

C57BL/6, Macgreen (B6N.Cg-Tg[Csf1r-EGFP]1Hume/J), CCR2RFP/RFP (B6.129[Cg]-Ccr2tm2.1lfc/J), and LysMCre (B6.129P2-Lyz2tm1(cre)lfo/J) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). CCR2RFP/RFP mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice to produce CCR2RFP/+ (CCR2 reporter) mice. OT-1GFP mice were described previously50. The CatchupIVM-red (Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato) mouse line was a gift from Dr. Gunzer3. The CCR2-DTR mouse line was obtained from Drs. Tobias Hohl and Amariliz Rivera51. EGFR-cKO (LysMCre/+/Egfrfl/fl) mouse was a gift from Dr. Fang Yan52. Eight- to nine-week-old male mice were infected with influenza virus as described previously at a dose of 6 × 105 of the 50% effective egg-infective dose (EID50) of HKx31 and a dose of 1 × 105.25 EID50 of HKx31-OVA50. Mouse neutrophils were purified from the BM using a MojoSort mouse neutrophil isolation kit (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) or were cell sorted based on Ly6G expression. The mice in this study were maintained in the pathogen-free space of the University of Rochester (UR) animal facility. The animal protocols were approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources at the University of Rochester (Rochester, NY, USA).

Antibodies and reagents.

Antibodies against Ly6G (1A8), Ly6C (HK1.4), F4/80 (BM8), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), MHC II (M5/114), H-2Kb-SIINFEKL (25-D1.16), CD8a (53–6.7), CD3 (17A2), CD4 (H129.19), CD19 (6D5), Granzyme B (GB11), TNF (MP6-XT22), IFN-γ(XMG1.2), CD64 (X54–5/7.1), CD86 (GL-1), CD40 (3/2.3), TGFβ (TW7–16B4), IL-6 (MP5–20F3), IL-10 (JES5–16E3), CD31 (390), CD26 (H194–112), CD24 (M1/69), BTLA (6A6), CD103 (2E7), CD68 (FA-11), and CD45.2 (104) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Antibodies against mouse EGF were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and BioVision (Milpitas, CA). Antibodies against EGFR and phospho-EGFR for Western blotting were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) and fluorophore-conjugated phospho-EGFR antibody for flow cytometry was purchased from R&D Systems. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for Western blotting were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). FITC-conjugated anti-influenza A virus nucleoprotein (NP) antibody was purchased from Virostat (Portland, ME). An anti-Ly6G antibody for neutrophil depletion and the corresponding isotype control IgG, and MHC I blocking antibody (M1/42.3.9.8) (and the corresponding isotype control IgG) were obtained from BioXcell (West Lebanon, NH). Brefeldin A, recombinant EGF and annexin V were purchased from BioLegend. Recombinant mouse ICAM-1 was obtained from Sino Biological (Wayne, PA). The pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk, recombinant CXCL2, CXCL9, CCL6, CCL7, CCL12, CCL19, CCL21, and TNF, Proteome Profiler mouse XL cytokine array kit, and Proteome Profiler mouse chemokine array kit were purchased from R&D Systems. fMLP, PMA, and diphtheria toxin (DTx) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). FasL was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). Influenza polymerase (PA) peptide (SSLENFRAYV) and nucleoprotein (NP) peptide (ASNENMETM) were obtained from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). An Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated tetramer complex that recognizes H-2Db/influenza PA (DbPA) was provided by the NIH Tetramer Facility (Atlanta, GA). The cell trace dye CFSE was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) and fluorophore (AT655)-conjugated z-VAD-fmk (CAS-MAP™ ProBo™ P Red) was purchased from Vergent Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN). Mouse primary lung epithelial cells and growth medium were purchased from Cell Biologics (Chicago, IL). Transwells (Transwell permeable supports, tissue culture-treated polyester membrane) were obtained from Costar (Corning, NY).

Intravital multi-photon microscopy.

Intravital multiphoton microscopy (IV-MPM) imaging was performed at the University of Rochester Multiphoton Research Core Facility using an Olympus FluoView FVMPE-RS Twin-Laser Gantry system with a 25x water immersion objective (NA 1.05 Olympus) and two lasers, the Spectra-Physics InsightX3 and MaiTai HP DeepSee Ti:Sapphire. Anesthesia of the mice was started by intraperitoneally injecting pentobarbital sodium-salt (65 mg/kg) and was further maintained by isoflurane inhalation for restraint and to avoid psychological stress and pain during imaging50. The trachea was exteriorized and a small cut was made on the frontal wall to insert an 18G blunt-end cannula. The mouse was subsequently placed on a custom-designed platform for tracheal imaging2. To visualize blood vessels, Brilliant violet 421- or Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated CD31 antibody was i.v. injected before the start of imaging. For IV-MPM of the mouse ear, 2 × 106 Ly6G+ neutrophils (LysMCre or WT) in 30 μl PBS were intradermally injected into the ear of Tyrc−2J/c−2J/ROSAtdTomato mice (B6-Albino). The injection site of each mouse was fixed and imaged again after 5 days using IV-MPM. Tissue resident macrophages were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD68 Ab.

Data were acquired at a resolution of 512 × 512 (16 bit) in stacks of 40 frames each 2.5 – 3.5 μm apart at a frame rate of 1.5 sec using FluoView software (Olympus). Red fluorescent signals were excited by 975 (tdTomato), 1100 (mRFP), or 1200 (Alexa Fluor 647) nm. Green fluorescent signals (FITC/GFP) were excited by 975 nm (GFP) or 820 nm (FITC), blue fluorescence by 820 nm, and SHG by 850 nm. The following filter cubes were used: SHG/Blue/Green (420–460nm/495–540nm, DM485) and Red/fRed (575–630nm/645–685nm, DM650). Raw imaging data were processed and analyzed with Volocity (PerkinElmer), Imaris (Bitplane), Arivis Vision 4D (Arivis), and ImageJ. Three-dimensional tracking of cells was performed using Volocity to generate spatial coordinates of individual objects over time. Automatic object tracking via Volocity was aided with manual corrections to retrieve cell spatial coordinates over time that were analyzed in ImageJ.

For the generation of 3D image projections, Arivis Vision 4D was used with default parameters. Unbiased 3D computational analysis of cell-cell interactions was performed by measuring voxel overlap between two cell surfaces with Imaris. First, 3D surface of monocyte and neutrophil was generated for all migrating cells in the image field by masking fluorescence signals under the intensity threshold, which was set on non-fluorescent cell images after background subtraction. The visible signal that was physically located within the overlapped pixels (within each z-stack in 3D) between monocyte and neutrophil 3D surfaces were automatically tracked over time and visualized.

Immunofluorescence and bright-field microscopy.

For migration assays, neutrophils were freshly isolated from mouse BM and placed in a glass-bottomed chamber (Millipore, Burlington, MA) coated with 10 µg/ml recombinant mouse ICAM-1 and the indicated chemokines in L-15 medium (Thermo Fischer Scientific) at 37°C. For immunofluorescence microscopy, neutrophils bound to the glass slide were fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% saponin, and stained with the indicated antibodies. Microscopy was conducted using a TE2000-U microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) and a 20x magnification objective. Migration analysis and image processing were performed using NIS (Nikon) or Volocity software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Flow cytometry and cell sorting.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting were performed at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) Flow Core. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from crushed and/or collagenase-digested tissue were stained with the indicated antibodies conjugated with fluorophores and analyzed using an LSRII 18 color flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Mouse neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+), monocytes (CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−), RFP+ cells from CCR2RFP/+ mice, macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+Ly6C−), DC (CD45+CD11chiMHC IIhi), and CD8+ T cells were cell sorted from the trachea, lungs, and lymph nodes using a FACS Aria (BD Bioscience). For the phenotypic analysis of CD8+ T lymphocytes, trachea/lung homogenates were isolated on day 7 post-infection from normal or neutropenic mice and incubated with viral NP and PA peptides (1 μM) in the presence of IL-2 and Brefeldin A for 6 h, and flow cytometry was conducted to measure the production of IFN-γ, TNF, and Gzm B following intracellular staining for the proteins.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Total RNA was prepared from the trachea or indicated cell types, and the transcript levels of the indicated genes were analyzed by qRT-PCR using the primers listed below (Supplementary Table 1).

RNA sequencing and data analysis.

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer’s recommendations. RNA concentration was determined with NanopDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE) and RNA quality was assessed with Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). One ng of total RNA was pre-amplified with the SMARTer Ultra Low Input kit v4 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) per the manufacturer’s recommendations. The quantity and quality of the subsequent cDNA was determined using the Qubit Fluorometer (Life Technnologies, Carlsbad, CA) and the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). 150 pg of cDNA was used to generate Illumina compatible sequencing libraries with the NexteraXT library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) per the manufacturer’s protocols. The amplified libraries were hybridized to the Illumina single end flow cell and amplified using the cBot (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Single end reads of 100 nt were generated for each sample. Volcano plot analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism v.7, and genes in the different conditions were compared based on adjusted p values and log2 fold change after filtering out genes with zero reads. Genes that were differentially expressed with p values less than 0.05 were highlighted based on negative or positive fold changes. Further clustering and heat map representations were produced using RStudio (Version 1.1.442, 2009–2018). Genes were clustered based on both Pearson and Spearman methods and plotted in terms of z-score. ‘ggplot2’ and ‘viridis’ libraries were installed and ‘heatmap.2’ was used to represent data clustered using ‘viridis’ color palettes. The Enrichr gene ontology (GO) database was used to obtain categories of signaling pathways relating to genes that were downregulated and upregulated in monocytes. The listed categories were ranked by the likelihood that genes fall into the group as a function of p-value.

Neutrophil depletion.

For neutrophil depletion, 500 μg of Ly6G (1A8) or isotype (2A3) antibody in 700 μl PBS was intraperitoneally injected into mice, and an additional 70–80 μg/10 μl of antibody was administered intranasally one day before infection and on days +1, +3, and +5 post-infection. Depletion of neutrophils was confirmed in each experiment by flow cytometry with anti-CD11b and anti-Ly6C antibody staining.

Depletion of DTR expressing cells.

For depletion of CCR2+ cells, CCR2-DTR mice and control CCR2-DTR–negative littermates received 2 ng/g (body weight) DTx intraperitoneally on days −1, +1, +3, and +5 during influenza infection. In the experiment with WT vs. ROSA-iDTR mice, the mice received 2 ml thioglycollate and 40 million of LysMCre neutrophils intraperitoneally on day 0 and then 2 ng/g DTx on day 2. Two days later, peritoneal cells were harvested for analysis.

Antibody microarray.

Total protein was extracted from the whole trachea or monocytes and used for an antibody microarray according to the manufacturer’s instructions. These arrays detected the relative levels of selected mouse cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors.

Western blot analysis.

Proteins in total cell lysates or the supernatant of neutrophil cultures were analyzed by Western blotting. Primary and secondary antibodies were used as indicated by the manufacturers, and the target proteins on the blot were visualized by SuperSignal West pico chemiluminescent reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and ChemiDoc (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Cell conjugation assay.

Neutrophil engulfed monocytes (GFP+/tdTomato+) or non- engulfed monocytes (GFP+/tdTomato−) were sorted from the lungs of HKx31-OVA infected Ly6GtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice. In other experiments, CCR2RFPLy6C+ monocytes were sorted from the lungs of HKx31-OVA infected normal or neutrophil-depleted CCR2RFP/+ mice. CD8+ T cells were negatively sorted from the lymph nodes of HkX31-infected OT-I mice (CD4−CD11b−CD19−MHCII−). The monocytes from HKx31-OVA infected mice and OT-I CD8+ T cells were incubated at a ratio of 1:20 for 30 min and chilled on ice. In another format, monocytes were pulsed with 5 μg/ml OVA peptide for 20 min and incubated with OT-I CD8+ T cells for 30 min. Conjugation was measured by counting GFP+ cells that were bound to CD8+ T cells on a glass slide using microscopy.

Neutrophil apoptosis.

Neutrophils were isolated from mouse bone marrow and incubated in serum-free RPMI medium. This procedure resulted in 50% spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis within 24 h. For some assays, early apoptotic neutrophils (live with intact membrane integrity) were sorted after staining with Alexa 660-conjugated Z-VAD-FMK53 (CD11b+Ly6G+Cas+).

Whole mount staining of the mouse ear.

WT or LysMCre neutrophils were injected into ROSAtdTomato mouse ears and, 5 days later, the whole ears were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 18 h. The fixed ears were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated with FITC-conjugated CD68 antibody for 18 h. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI before imaging.

Transwell assay.

A total of 150,000 monocytes were sorted from the lungs of influenza-infected Csf1r-GFP mice. Neutrophils were isolated from the bone marrow of Ly6G-tdTomato mice and induced to undergo spontaneous apoptosis. Cells were labeled with violet fluorescence (CellTrace™ Violet cell proliferation kit, Thermofisher), placed in a transwell insert (3 μm pore size) and then incubated with 150,000 purified early apoptotic neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+Cas+) or monocytes in the bottom chamber, respectively. The plate was incubated for 16 h, and the cells from the bottom chamber were harvested for analysis. In a different experiment, 2 million WT or LysMCre neutrophils were placed in a transwell insert (0.4 μm pore size), and the transwell insert was placed in a bottom well that contained ROSAtdTomato-BMDMs.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1.

a. Schematic representation of the host immune responses in the airway during influenza infection. The various waves correspond to schemes (neutrophils, monocytes, CD8+ T cells, and macrophages) that summarize the data presented in Fig. 1A and 1B. b. Flow cytometry analysis of the neutrophil numbers in the dLN (mediastinal lymph node) of naïve or influenza-infected mice. c. Apoptotic neutrophils from WT or LysMCre mice (upper chamber) and bone marrow (BM)-derived macrophages from ROSAtdTomato mice (bottom chamber) were co-cultured for 7 days in the cell impermeable transwell system (0.4 μm pore size). Bar, 50 μm. d. Flow cytometry analysis of the BM and dLN of the mice in the experiments described in Fig. 1I. Note the lack of tdTomato+ cells in the BM and dLN. e. Live BM cells isolated from LysMCre or WT mice (20 – 50 × 106) were injected into the peritoneum of recipient ROSAtdTomato mice. Flow cytometry analysis of the peritoneal lavage revealed tdTomato+/F4/80+ macrophages in the mice that received LysMCre cells. Representative plots of the flow cytometry data from five independent experiments are shown. f. Blood cells (day 4 post HKx31 infection) from Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato/Csf1r-EGFP mice were analyzed by flow cytometry.

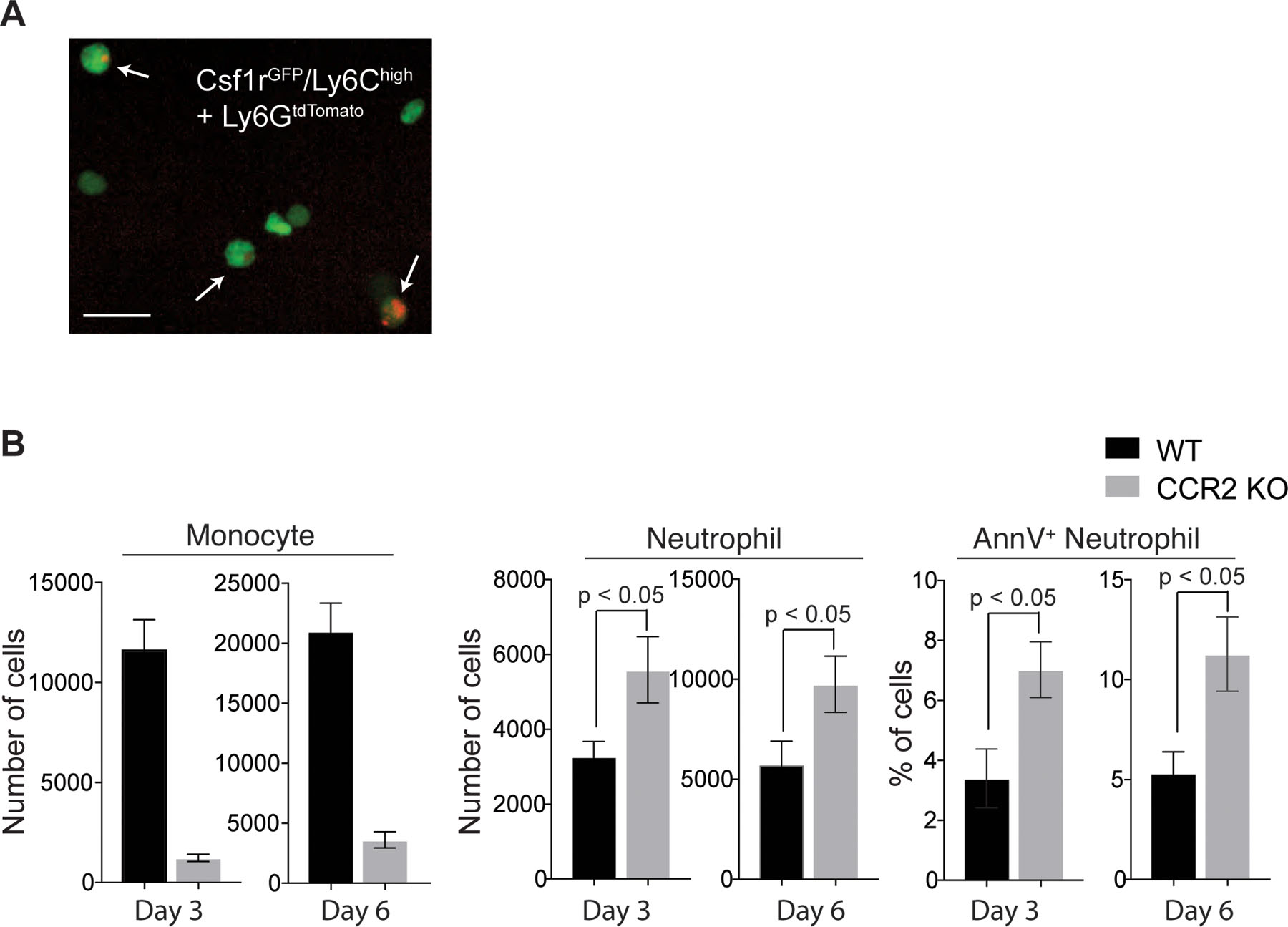

Extended Data Fig. 2.

a. In vitro fluorescence images of apoptotic neutrophil-engulfed monocytes. Monocytes (green; GFP+Ly6C+Ly6G−) were sorted from influenza-infected Csf1r-EGFP mouse lungs and co-incubated with apoptotic neutrophils (red) isolated from Ly6GCre/ROSAtdTomato mice. Three hours later, Ly6G−Csfr1GFP cells were sorted again and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. Arrows indicate neutrophil-engulfed monocytes. Scale bar, 25 μm. b. Numbers of monocytes (left) and total neutrophils (middle) and percentages of Annexin V+ neutrophils (right) in the influenza-infected trachea of WT or CCR2 KO mice (n ≥ 3 per group).

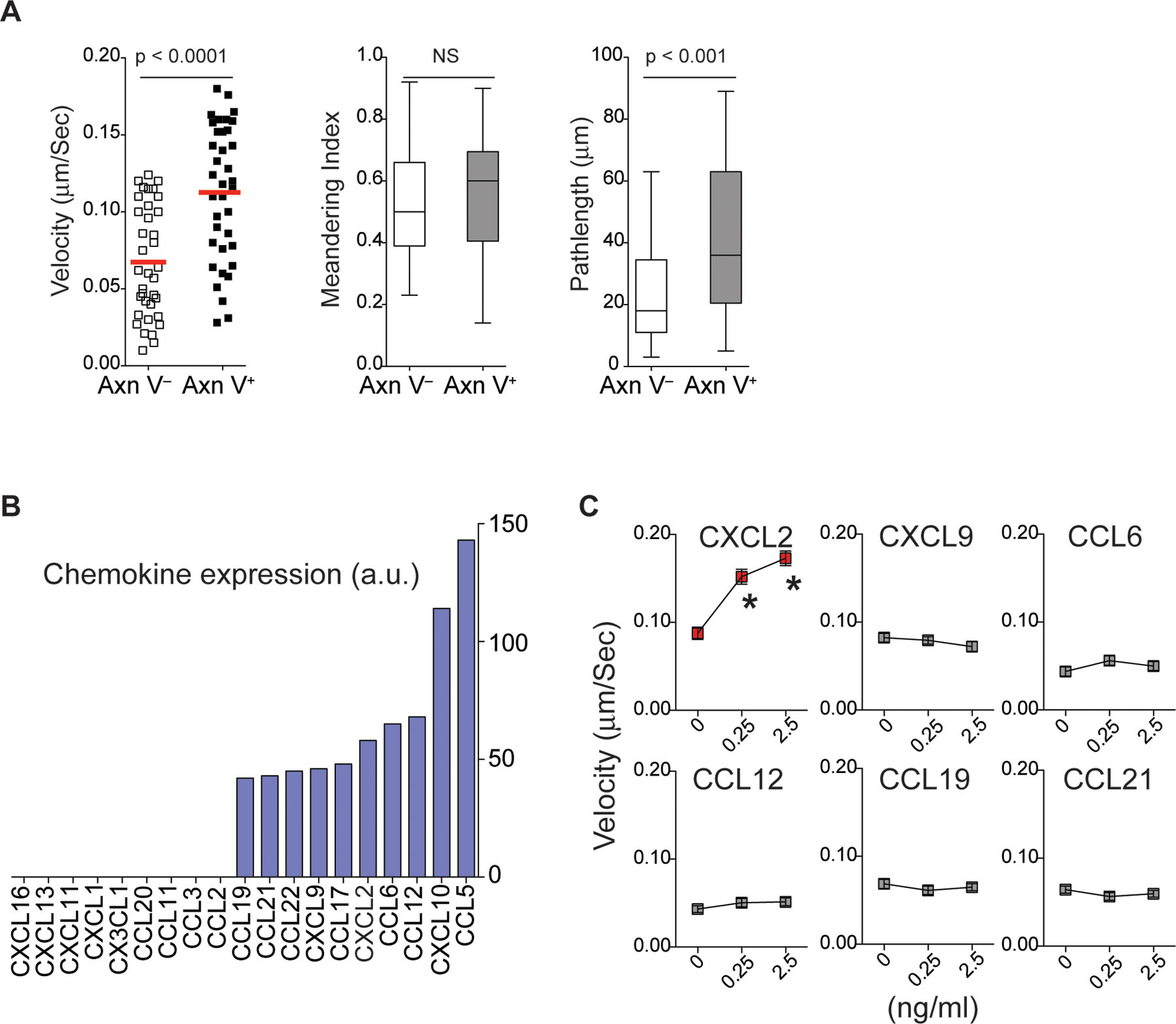

Extended Data Fig. 3.

a. In vitro migration of Annexin V− vs. Annexin V+ neutrophils on the ICAM-1 coated surface. The mean velocity, displacement, and meandering index of the neutrophils are shown. n = 3 per group. Statistical differences were assessed by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. b. Chemokine microarray performed with total lysates of monocytes harvested on day 5 post-infection from the influenza-infected mouse lung. Chemokine expression levels are expressed as arbitrary units measured by densitometry. c. Neutrophil migration via ICAM-1 with the indicated chemokines. A single assay analyzed at least 10 cells (n = 3 assays per group). *p <0.05 compared with the control. Data were analyzed with the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s posttest.

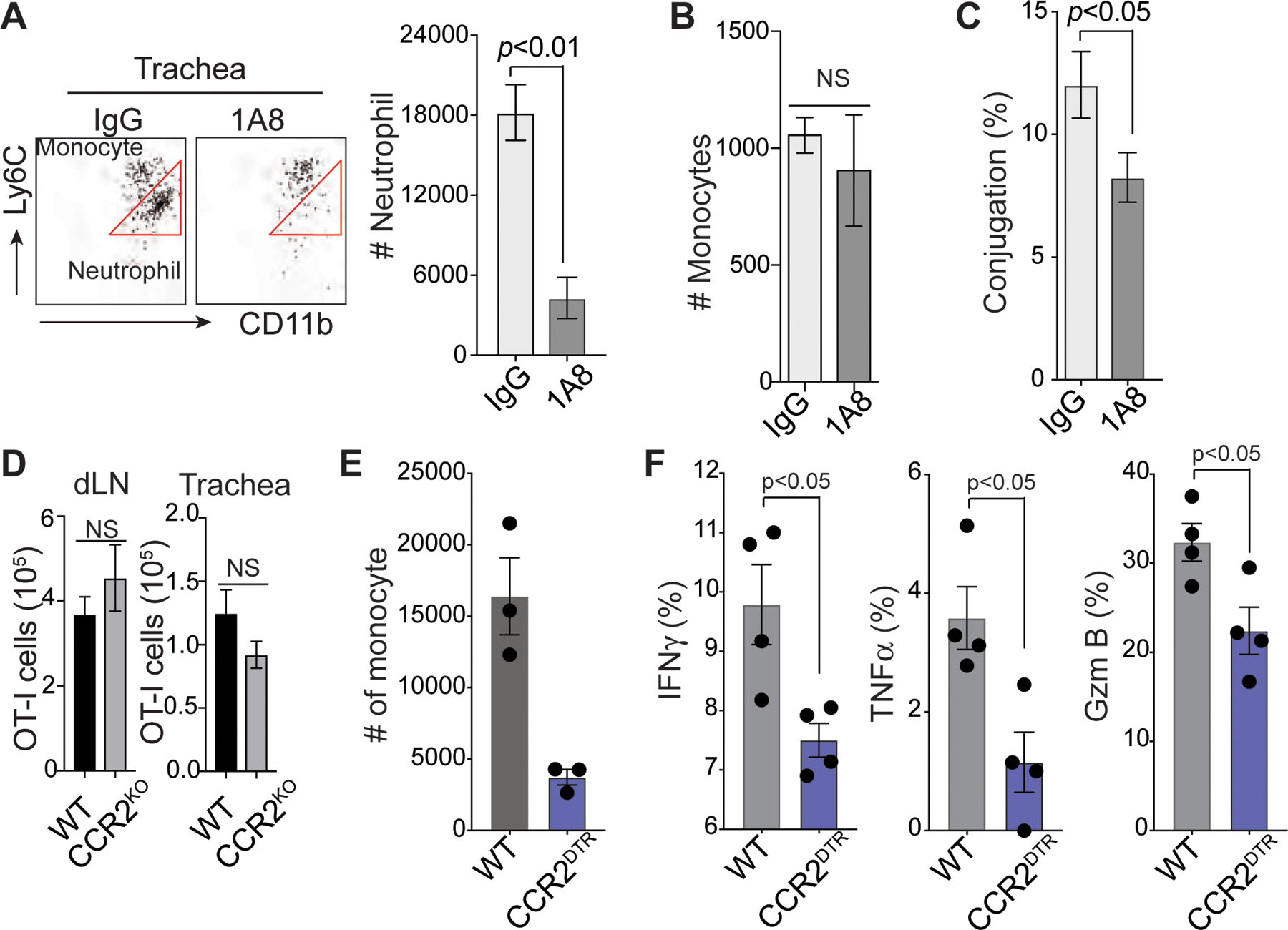

Extended Data Fig. 4.

a. Flow cytometry analysis of neutrophils and monocytes from influenza-infected mouse trachea with or without neutrophil depletion. Cells were stained with Ly6C antibody and CD11b antibody (mean ± SEM, n = 4 mice per group). b. Numbers of monocytes (CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−) in the influenza-infected mouse trachea with or without neutrophil depletion. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 4 mice per group. Statistical differences were assessed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. c. RFP+ monocytes sorted from the trachea and lungs of HKx31-OVA virus-infected CCR2RFP/+ mice with or without neutrophil depletion were incubated with CD8+ T cells isolated from influenza-infected OT-I mouse dLNs. The monocyte-T cell conjugates were measured by microscopy. Conjugation (%); # monocytes bound to CD8+ T cells/# total monocytes. n ≥ 3 per group. Statistical differences were assessed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. d. Numbers of OT-I CD8+ T cells from the dLN and trachea of HKx31-OVA virus-infected WT or CCR2 KO mice. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice per group. Statistical differences were assessed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. e. Numbers of monocytes (CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−) in the influenza-infected trachea of CCR2-DTR and WT mice on day 6 post-infection. Diphtheria toxin was injected into both mouse strains on days −1, +1, +3, and +5 post-infection. f. Flow cytometry analysis of the production of IFNγ, TNFα, and Granzyme B (Gzm B) in CD8+ T cells on day 7 post-infection from WT vs. CCR2-DTR influenza-infected mice treated with diphtheria toxin. Statistical differences were assessed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

Extended Data Fig. 5.

a. Immunofluorescence image of a permeabilized neutrophil stained with Abs against Ly6G (green) and EGF (red). Scale bar, 5 μm. b. Flow cytometry analysis of EGF in permeabilized mouse neutrophils (day 4 post-infection). c. Secretion of EGF from neutrophils undergoing spontaneous apoptosis. d. Flow cytometry analysis of phagocytic activity (tdTomato) of monocytes (Csf1r-GFP) isolated from the influenza infected lung after co-incubation with tdTomato+ apoptotic neutrophils for 12 h in the presence of PBS or erlotinib (0.1 μg/ml). e. Monocytes (Csf1r-GFP) were isolated from the influenza infected lung. After co-incubation with tdTomato+ apoptotic neutrophils for 12 h in the presence of PBS or erlotinib (0.1 μg/ml), neutrophil-engulfed (tdTomato+) and non-engulfed (tdTomato−) monocytes were sorted, pulsed with OVA peptide, and incubated with CD8+ T cells isolated from influenza-infected OT-I mouse dLNs. Monocyte-T cell conjugation was measured by microscopy. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3 mice per group. Statistical differences were assessed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Hohl and A. Rivera for CCR2-DTR mouse and F. Yan for EGFR-cKO (Egfrflox/LysMCre) mouse. We especially thank M. Gunzer for CatchupIVM-Red mouse, Y. Gao for the technical assistance with IV-MPM, and J. Ashton for help with transcriptomic analyses and depositing RNA-sequencing data. This project was financially supported through grants from the National Institute of Health (AI143182, AI147362, AI149775 to M.K. and AI102851 to M.K., D.J.F., & D.J.T. and AI138415 to H.P. and AI070826 to D.J.F.)

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Reference

- 1.Girard MP, Cherian T, Pervikov Y & Kieny MP A review of vaccine research and development: human acute respiratory infections. Vaccine 23, 5708–5724, doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.046 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garner H & de Visser KE Neutrophils take a round-trip. Science 358, 42–43, doi: 10.1126/science.aap8361 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasenberg A et al. Catchup: a mouse model for imaging-based tracking and modulation of neutrophil granulocytes. Nature methods 12, 445–452, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3322 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hind LE & Huttenlocher A Neutrophil Reverse Migration and a Chemokinetic Resolution. Dev Cell 47, 404–405, doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.11.004 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J et al. Visualizing the function and fate of neutrophils in sterile injury and repair. Science 358, 111–116, doi: 10.1126/science.aam9690 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmgren L, Bergsmedh A & Spetz AL Horizontal transfer of DNA by the uptake of apoptotic bodies. Vox Sang 83 Suppl 1, 305–306 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmgren L et al. Horizontal transfer of DNA by the uptake of apoptotic bodies. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bergsmedh A et al. Horizontal transfer of oncogenes by uptake of apoptotic bodies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98, 6407–6411, doi: 10.1073/pnas.101129998 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan B, Wang H, Li F & Li CY Regulation of mammalian horizontal gene transfer by apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Br J Cancer 95, 1696–1700, doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603484 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyun YM et al. Uropod elongation is a common final step in leukocyte extravasation through inflamed vessels. The Journal of experimental medicine 209, 1349–1362, doi: 10.1084/jem.20111426 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poo YS et al. CCR2 deficiency promotes exacerbated chronic erosive neutrophil-dominated chikungunya virus arthritis. J Virol 88, 6862–6872, doi: 10.1128/JVI.03364-13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuziel WA et al. Severe reduction in leukocyte adhesion and monocyte extravasation in mice deficient in CC chemokine receptor 2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94, 12053–12058 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oshima T et al. Analysis of corneal inflammation induced by cauterisation in CCR2 and MCP-1 knockout mice. Br J Ophthalmol 90, 218–222, doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.077875 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart SP, Dransfield I & Rossi AG Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Methods (San Diego, Calif 44, 280–285, doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.11.009 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dzhagalov IL, Chen KG, Herzmark P & Robey EA Elimination of self-reactive T cells in the thymus: a timeline for negative selection. PLoS Biol 11, e1001566, doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001566 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ichikawa A et al. CXCL10-CXCR3 enhances the development of neutrophil-mediated fulminant lung injury of viral and nonviral origin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187, 65–77, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0508OC (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reichel CA et al. Chemokine receptors Ccr1, Ccr2, and Ccr5 mediate neutrophil migration to postischemic tissue. Journal of leukocyte biology 79, 114–122, doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605337 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Filippo K et al. Mast cell and macrophage chemokines CXCL1/CXCL2 control the early stage of neutrophil recruitment during tissue inflammation. Blood 121, 4930–4937, doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-486217 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartl D et al. Infiltrated neutrophils acquire novel chemokine receptor expression and chemokine responsiveness in chronic inflammatory lung diseases. J Immunol 181, 8053–8067 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beauvillain C et al. CCR7 is involved in the migration of neutrophils to lymph nodes. Blood 117, 1196–1204, doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254490 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia GQ et al. Distinct expression and function of the novel mouse chemokine monocyte chemotactic protein-5 in lung allergic inflammation. The Journal of experimental medicine 184, 1939–1951 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaur M & Singh D Neutrophil chemotaxis caused by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease alveolar macrophages: the role of CXCL8 and the receptors CXCR1/CXCR2. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 347, 173–180, doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201855 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soehnlein O & Lindbom L Phagocyte partnership during the onset and resolution of inflammation. Nature reviews 10, 427–439, doi: 10.1038/nri2779 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wynn TA & Vannella KM Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 44, 450–462, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dominguez PM & Ardavin C Differentiation and function of mouse monocyte-derived dendritic cells in steady state and inflammation. Immunological reviews 234, 90–104, doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00876.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakubzick CV, Randolph GJ & Henson PM Monocyte differentiation and antigen-presenting functions. Nature reviews 17, 349–362, doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.28 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broz ML et al. Dissecting the Tumor Myeloid Compartment Reveals Rare Activating Antigen-Presenting Cells Critical for T Cell Immunity. Cancer Cell 26, 938, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.010 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang TT, Jabs C, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK & Sharpe AH Studies in B7-deficient mice reveal a critical role for B7 costimulation in both induction and effector phases of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. The Journal of experimental medicine 190, 733–740 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krummel MF, Heath WR & Allison J Differential coupling of second signals for cytotoxicity and proliferation in CD8+ T cell effectors: amplification of the lytic potential by B7. J Immunol 163, 2999–3006 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindsay RS et al. Antigen recognition in the islets changes with progression of autoimmune islet infiltration. J Immunol 194, 522–530, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400626 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thornton EE et al. Spatiotemporally separated antigen uptake by alveolar dendritic cells and airway presentation to T cells in the lung. The Journal of experimental medicine 209, 1183–1199, doi: 10.1084/jem.20112667 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ley K The second touch hypothesis: T cell activation, homing and polarization. F1000Res 3, 37, doi: 10.12688/f1000research.3-37.v2 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM & Pamer EG Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annu Rev Immunol 26, 421–452, doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090326 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serbina NV, Salazar-Mather TP, Biron CA, Kuziel WA & Pamer EG TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells mediate innate immune defense against bacterial infection. Immunity 19, 59–70 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varol C et al. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine 204, 171–180, doi: 10.1084/jem.20061011 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ginhoux F et al. Langerhans cells arise from monocytes in vivo. Nature immunology 7, 265–273, doi: 10.1038/ni1307 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jakubzick C et al. Minimal differentiation of classical monocytes as they survey steady-state tissues and transport antigen to lymph nodes. Immunity 39, 599–610, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.007 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larson SR et al. Ly6C(+) monocyte efferocytosis and cross-presentation of cell-associated antigens. Cell Death Differ 23, 997–1003, doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.24 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schnorrer P et al. The dominant role of CD8+ dendritic cells in cross-presentation is not dictated by antigen capture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 10729–10734, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601956103 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iyoda T et al. The CD8+ dendritic cell subset selectively endocytoses dying cells in culture and in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine 195, 1289–1302 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desch AN et al. CD103+ pulmonary dendritic cells preferentially acquire and present apoptotic cell-associated antigen. The Journal of experimental medicine 208, 1789–1797, doi: 10.1084/jem.20110538 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sichien D, Lambrecht BN, Guilliams M & Scott CL Development of conventional dendritic cells: from common bone marrow progenitors to multiple subsets in peripheral tissues. Mucosal Immunol 10, 831–844, doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.8 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]