Key Points

Question

Can a printed vision chart used as a home vision test accurately measure visual acuity for people with eye disease?

Findings

In this diagnostic study of 50 control participants and 100 ophthalmology outpatients, Bland-Altman analyses showed excellent repeatability of the Home Acuity Test and good agreement with the last recorded in-clinic visual acuity.

Meaning

These findings suggest that a printed chart can be used to measure visual acuity at home by ophthalmology patients.

Abstract

Importance

Many ophthalmology appointments have been converted to telemedicine assessments. The use of a printed vision chart for ophthalmology telemedicine appointments that can be used by people who are excluded from digital testing has yet to be validated.

Objectives

To evaluate the repeatability of visual acuity measured using the Home Acuity Test (HAT) and the agreement between the HAT and the last in-clinic visual acuity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This diagnostic study was conducted from May 11 to 22, 2020, among 50 control participants and 100 adult ophthalmology outpatients who reported subjectively stable vision and were attending routine telemedicine clinics. Bland-Altman analysis of corrected visual acuity measured with the HAT was compared with the last measured in-clinic visual acuity on a conventional Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study logMAR chart.

Main Outcomes and Measures

For control participants, repeatability of the HAT and agreement with standard logMAR visual acuity measurement. For ophthalmology outpatients, agreement with the last recorded in-clinic visual acuity and with the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision visual impairment category.

Results

A total of 50 control participants (33 [66%] women; mean [SD] age, 36.0 [10.8] years) and 100 ophthalmology patients with a wide range of diseases (65 [65%] women; mean [SD] age, 55.3 [22.2] years) were recruited. For control participants, mean (SD) test-retest difference in the HAT line score was −0.012 (0.06) logMAR, with limits of agreement (LOA) between −0.13 and 0.10 logMAR. The mean (SD) difference in visual acuity compared with conventional vision charts was −0.14 (0.14) logMAR (range, −0.4 to 0.18 log MAR) (−7 letters) in controls, with LOA of −0.41 to 0.12 logMAR (−20 to 6 letters). For ophthalmology outpatients, the mean (SD) difference in visual acuity was −0.10 (0.17) logMAR (range, −0.5 to 0.3 logMAR) (1 line on a conventional logMAR sight chart), with the HAT indicating poorer visual acuity than the previous in-clinic test, and LOA of −0.44 to 0.23 logMAR (−22 to 12 letters). There was good agreement in the visual impairment category for ophthalmology outpatients (Cohen κ = 0.77 [95% CI, 0.74-0.81]) and control participants (Cohen κ = 0.88 [95% CI, 0.88-0.88]).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study suggests that the HAT can be used to measure visual acuity by telephone for a wide range of ophthalmology outpatients with diverse conditions. Test-retest repeatability is relatively high, and agreement in the visual impairment category is good for this sample, supporting the use of printed charts in this context.

This diagnostic study evaluates the repeatability of vision measured using the Home Acuity Test and the agreement between the Home Acuity Test results and the last in-clinic visual acuity among ophthalmology outpatients in the United Kingdom.

Introduction

Eye problems are the cause of approximately 1.5% of all consultations with family physicians in the English health care system,1 and ophthalmology is the largest specialty, with nearly 8 million ophthalmology outpatient appointments taking place in England every year.2 In response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, in March 2020 the UK’s Royal College of Ophthalmologists recommended that “all face-to-face outpatient activity should be postponed unless patients are at high risk of rapid, significant harm if their appointment is delayed.”3(p1) During the next 3 months, more than 100 000 ophthalmology outpatient appointments were canceled at Moorfields Eye Hospital alone.

Video and telephone-based consultations have been used successfully in ophthalmology,4,5,6 but measuring visual acuity (VA) remotely remains a challenge. Computer-based assessments of VA require careful calibration of viewing distance, screen size, and screen luminance.7 Trials of computer-based VA measurements have involved giving participants laptops with known screen parameters.8,9

Smartphones can be used to measure VA,10 but a 2015 review of smartphone vision testing applications found poor agreement with results of conventional vision tests, particularly for people with severe vision impairment.11 In addition, more than 1 in 8 people in the UK do not use the internet, including 48% of those older than 75 years,12 all of whom are classified as being of at least moderate risk of complications from COVID-19.13 People with lower household income are also more likely to be digitally excluded.12 These difficulties have caused ophthalmology services to ask patients to judge their performance on daily living tasks such as reading television subtitles, to measure certain aspects of vision but not distance VA, to defer VA testing completely, or to use printed charts.14,15

Organizations such as the American Academy of Ophthalmology16 and the UK’s College of Optometrists17 have made paper vision charts to be downloaded and printed. These tests do not meet the international guidelines for progression of letter size,18,19 do not have crowding bars, and have not been validated. Furthermore, only 1 chart is available from each organization, making repeat measurement inaccurate, as people are likely to remember the letters when reading with their second eye.

Herein we assess the Home Acuity Test (HAT),20 an open-source vision screening test that can be printed on A4-size paper and mailed to patients. It could also be downloaded and printed by patients for urgent or emergency assessment—a silhouette of a credit card is included with the downloadable test to ensure that the printed size of the image is correct and that no unexpected scaling has taken place. The HAT incorporates a logarithmic scaling of letter size and crowding bars. A total of 58 quadrillion unique charts can be downloaded from https://homeacuitytest.org for home monitoring of vision.

Methods

We developed the HAT to measure VA remotely for patients unable to attend hospital ophthalmology appointments because of the COVID-19 outbreak. The HAT chart consists of 18 randomly selected Sloan letters21 displayed on 5 lines. Letter size progresses logarithmically, with letters being half the size of those on the preceding line. Four letters are presented on each line except the first line, which contains 2 letters. Crowding bars of 1 stroke width surround each line of letters, with a 1 stroke–width gap between the letter edge and the crowding bar. From 150 cm, the largest letters subtend 1.3 logMAR (3/60 or 20/400) and the smallest line measures 0.1 logMAR (6/7.5 or 20/25). The study of control participants was approved by the University College London Research Ethics Committee prior to data collection. Written informed consent was collected from all participants and no incentive or remuneration was provided for participation. Approval for the retrospective analysis of patient data was obtained from the Clinical Audit committee at Moorfields Eye Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust.

Control Participants

In this diagnostic study conducted from May 11 to 22, 2020, 50 adults were recruited from Moorfields Eye Hospital staff. All had good corrected VA (of at least 0.1 logMAR [6/7.5 or 20/25] with spectacles). Participants covered their better eye with their hand and read 2 versions of the HAT chart from 150 cm with their poorer eye. Spectacles were not worn, to avoid a ceiling effect and to evaluate whether the HAT overestimated vision for those with uncorrected myopia, owing to the chart’s closer viewing distance. Data were recorded in 2 ways: as a total number of letters read and by using a line assignment method in which credit was given for a line where half of the letters were read correctly. Participants also read a conventional retroilluminated Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) logMAR VA chart from the standard distance of 4 m, with data recorded using letter-by-letter scoring.

Bland-Altman analysis evaluated agreement between VA measured using the HAT and using the conventional logMAR chart, as well as agreement using repeated measurements on the HAT (repeatability).22 For each of these analyses, we report the mean (SD) difference in score, which quantifies bias between measurements, with range of differences. In addition, we report the limits of agreement (LOA), which quantify the interval expected to contain 95% of the difference scores. Results of these analyses are reported in full with 95% CIs in Table 1.23 The lower granularity of the HAT (0.3 logMAR per line) places limits on the minimal agreement possible (expected measurement difference given zero variability across tests is bias ±0.15 logMAR). We assigned clinical categories to both test scores and computed Cohen κ as measures of category agreement; values exceeding 0.7 are considered to provide evidence for good agreement.24,25,26

Table 1. Bias, SD, and LOA for All Bland-Altman Analyses.

| Analysis | Bias (95% CI) | SD (95% CI) | LOA (95% CI) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Control participants | |||||

| HAT vs clinic line scorea | −0.145 (−0.199 to −0.091) | 0.136 (0.098 to 0.174) | −0.412 (−0.45 to −0.373) | 0.121 (0.083 to 0.159) | −0.4 to 0.18 |

| First HAT vs second HAT, No. of letters | 0 (−0.19 to 0.19) | 0.67 (0.483 to 0.857) | −1.313 (−1.643 to −0.983) | 1.313 (0.983 to 1.643) | −2 to 1 |

| First HAT vs second HAT, No. of letters converted to logMAR | 0 95% CI (−0.014 to 0.014) | 0.05 95% CI (0.036 to 0.064) | −0.098 95% CI (−0.123 to −0.074) | 0.098 95% CI (0.074 to 0.123) | −0.075 to 0.15 |

| First HAT vs second HAT, line score | −0.012 (−0.029 to 0.005) | 0.059 (0.009 to 0.11) | −0.128 (−0.158 to −0.099) | 0.104 (0.075 to 0.134) | −0.3 to 0 |

| Outpatients | |||||

| HAT vs clinic, line scorea | −0.102 (−0.136 to −0.067) | 0.171 (0.147 to 0.196) | −0.437 (−0.462 to −0.413) | 0.234 (0.209 to 0.259) | −0.5 to 0.3 |

Abbreviations: HAT, Home Acuity Test; LOA, limits of agreement.

Analyses were corrected for censored data23 owing to the 0.1-logMAR upper bound of the HAT.

Ophthalmology Outpatients

Since early April 2020, HAT charts have been posted to outpatients having telephone consultations in 2 adult ophthalmology clinics—strabismus and low vision—as part of a service improvement project. Patients were sent 2 different HAT charts (with different letters on each) along with reusable adhesive to fix charts to a wall and a 150-cm length of string to measure chart viewing distance. Patients were telephoned by a clinician (optometrist, orthoptist, or ophthalmologist). As part of their telephone assessment, participants were asked to cover each eye in turn and to read the HAT from 150 cm, using distance glasses if necessary. The number of letters read correctly was recorded. Visual acuity was also recorded in logMAR, with credit given for a line when half of the letters on the line were read correctly (2 of 4 letters for the smaller lines and 1 of 2 letters for the larger lines).

Data were analyzed for 100 patients who self-described their vision as stable. Participants were not excluded based on differences in acuity measured on the HAT and in the clinic. Data were analyzed from the right eye only, unless VA was not recordable from the right eye (ie, VA was poorer than 1.3 logMAR [3/60 or 20/400]), in which case the left eye was used. Bland-Altman analyses were used to compare home-measured VA on the HAT with the last VA value measured in an ophthalmology clinic. Depending on the ophthalmology clinic last attended, VA was measured by clinic staff using either internally illuminated ETDRS logMAR charts or Test Chart 2000 (Thomson Software Solutions).

For ophthalmology patients, vision was classified into categories of visual impairment loosely based on the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision guidelines27 (Table 2). Exact agreement with the World Health Organization guidelines was not possible owing to the levels of VA measured on the HAT.

Table 2. Categorization of Visual Impairment by HAT and ICD-11 Guidance.

| Visual impairment category | HAT guideline, logMARa | ICD-11 guideline, logMARa |

|---|---|---|

| None | 0.1 | 0.3 or Better |

| Mild | 0.4 | Worse than 0.3 |

| Moderate | 0.7 | Worse than 0.5 |

| Severe | 1.0 | Worse than 1.0 |

| Blind | 1.3 | Worse than 1.3 |

Abbreviations: HAT, Home Acuity Test; ICD-11, International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision.

Snellen equivalents: 0.1 logMAR, 6/7.5 or 20/25; 0.3 logMAR, 6/12 or 20/40; 0.4 logMAR, 6/15 or 20/50; 0.5 logMAR, 6/19 or 20/63; 1.0 logMAR, 6/60 or 20/200; and 1.3 logMAR, 3/60 or 20/400.

Results

Control Participants

The mean (SD) age of the 50 control participants was 36.0 (10.8) years (range, 22-61 years). Thirty-three (66%) were female. The mean (SD) VA in the tested eye was 0.15 (0.39) logMAR (6/7.5 or 20/25; range, −0.3 to 1.1 logMAR [6/3 to 6/75 or 20/10 to 20/250]).

Agreement Between HAT and Conventional logMAR Chart

The mean (SD) difference in VA was −0.14 (0.14) logMAR (range, −0.4 to 0.18 logMAR), less than 2 lines on a conventional logMAR sight chart, with the clinic chart indicating better vision than the HAT. The best VA measurable on the HAT is 0.1 logMAR (6/7.5 or 20/15). Post hoc evaluation showed that 31 participants had better vision than this on the conventional chart. This finding means that these values are censored: true acuity may exceed 0.1, but it is unknown whether this is the case or by how much. To account for this possibility, the Bland-Altman analysis was performed using maximum likelihood estimation for censored data.23 This analysis revealed an LOA interval between −0.41 and 0.12 logMAR (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Difference Between Visual Acuity Measured With Conventional and Home Acuity Test (HAT) Charts and Repeatability of HAT for 50 Control Participants .

A, Difference between visual acuity measured with conventional and HAT charts for 50 control participants. B, Repeatability of HAT for 50 control participants using letter-by-letter scoring. N indicates the number of individuals per data point in the plot; VA, visual acuity; the gray-shaded bands, 95% CIs; solid horizontal lines, mean difference across measurements; dashed horizontal lines, reference x-axis corresponding to zero differences between measurements; and vertical lines with limit lines, 95% CIs on the limits of agreement.

Association of Uncorrected Myopia With Test Results

Thirteen participants (26%), with a mean (SD) age of 34.1 (11.3) years, had myopia and read the chart without spectacles. For this subgroup, the mean (SD) difference in VA measured with the HAT and conventional charts was −0.09 (0.15) logMAR (range, −0.34 to 0.18 logMAR), indicating that VA was approximately 1 line worse on the HAT than on the conventional chart. The closer test distance of the HAT did not overestimate VA.

Repeatability of HAT

Using letter-by-letter scoring, the mean (SD) difference in VA between 2 versions of the HAT was 0 (0.67) letters (range, −2 to 1 letters) (Figure 1), with LOA between −1.3 and 1.3 letters. When using line assignment scoring, the mean (SD) difference was −0.012 (0.06) logMAR (range, −0.3 to 0 logMAR), with LOA between −0.13 and. 0.10 logMAR.

Ophthalmology Outpatients

The mean (SD) age of the 100 outpatients was 55.3 (22.2) years (range, 16-97 years). Sixty-five outpatients were female. Primary diagnosis was retinal disease in 24 participants, age-related macular degeneration in 14, and strabismus in 14. Full diagnoses are given in the eTable in the Supplement. The mean (SD) HAT VA in the test eye was 0.78 (0.37) logMAR (approximately 6/38 or 20/125; range, 0.1-1.3 logMAR [6/7.5 to 3/60 or 20/25 to 20/400]). The mean time since the last clinic VA measurement was 12 months (range, 1-69 months).

The mean (SD) difference in VA between the HAT and the last in-clinic VA assessment was −0.10 (0.17) logMAR (range, −0.5 to 0.3 logMAR) (1 line on a conventional logMAR sight chart), with the HAT indicating poorer vision than the previous in-clinic test. The LOA corrected for censored data23 were between −0.44 and 0.23 logMAR (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Difference Between Visual Acuity (VA) Measured With Conventional and Home Acuity Test (HAT) Charts for 100 Ophthalmology Outpatients.

N indicates the number of individuals per data point in the plot; the gray-shaded band, 95% CI; solid horizontal line, mean difference across measurements; dashed horizontal line, reference x-axis corresponding to zero differences between measurements; and vertical lines with limit lines, 95% CIs on the limits of agreement.

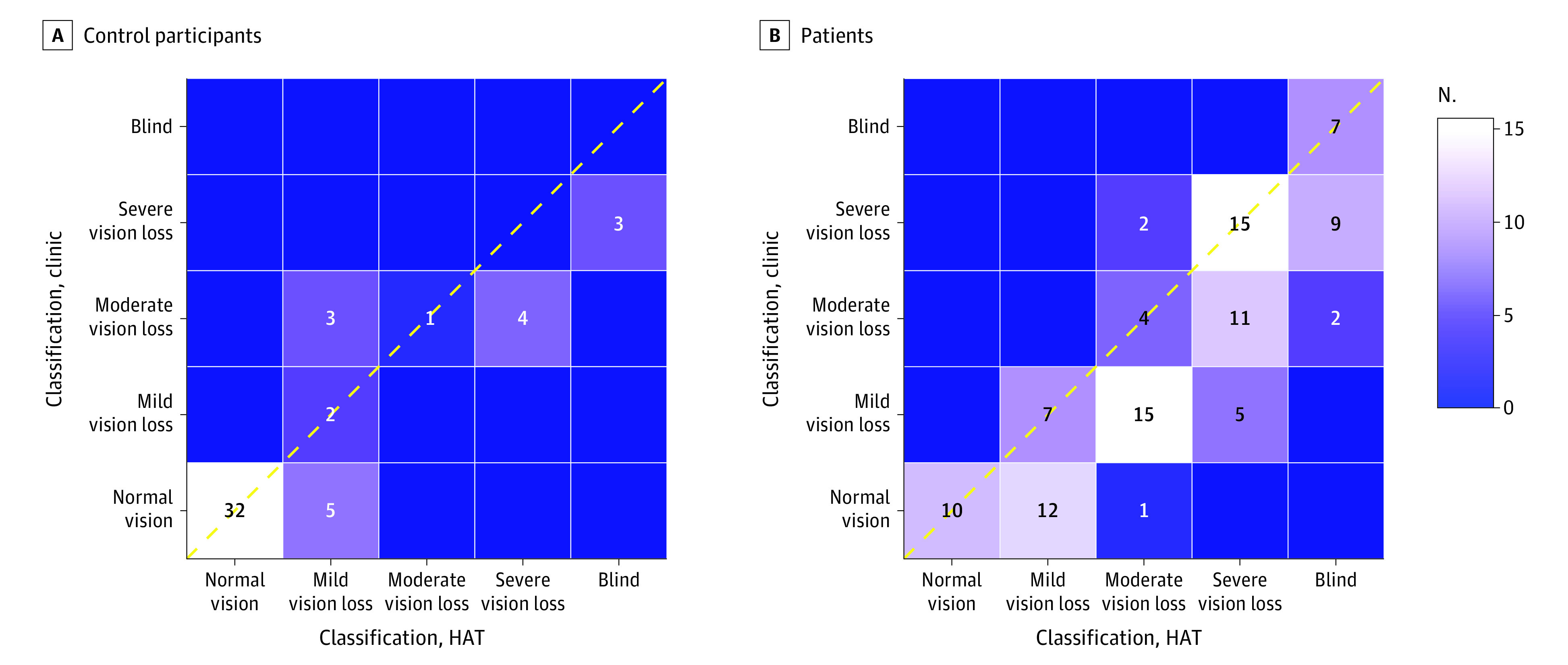

The HAT classified 10 patients as not visually impaired, 19 as having mild visual impairment, 22 as moderately visually impaired, 31 as severely visually impaired, and 18 as blind. The agreement between the categorical classification resulting from the in-clinic test and the HAT test was quantified using Cohen κ, which revealed good strength of agreement between the 2 tests, at κ = 0.77 (95% CI, 0.74-0.81) (Figure 3), following the Altman26 magnitude guidelines. The same analysis for control participants showed an agreement of κ = 0.88 (95% CI, 0.88-0.88).

Figure 3. Agreement in Clinical Categorization Between Home Acuity Test (HAT) and the Last In-Clinic Visual Acuity Measurement.

N indicates the number of individuals per cell in the grid plot; and the dashed diagonal line, the identity line corresponding to perfect agreement between measurements.

Discussion

We have shown that VA can be measured using a printed vision test. Test repeatability is high, with test-retest differences ranging from −2 to 1 letters in control participants and compares favorably with data published for conventional and computer-based clinic charts.28,29 The mean VA difference with standard clinical tests was within 5 letters for patients and control participants, with good agreement for categorizing the level of vision impairment.

The high repeatability of the HAT should give confidence in identifying new intraocular differences in vision, making it potentially appropriate for monitoring vision in people with strabismus, or with disease likely to worsen in 1 eye. Users should note that, because the charts are generated automatically, some charts might be easier to read than others owing to differences in legibility between Sloan letters. Although we have presented data only for a letter chart, the HAT website includes a symbol version of the test for children and those who cannot identify letters that uses the Auckland optotypes.30

Asking patients to self-report their vision on a printed test in their own home differs from measuring VA in a clinic in several important ways. First, the contrast of the printed chart is less than that of a conventional logMAR chart. Contrast sensitivity is reduced in people with a wide range of eye diseases.31,32 Second, lighting at home is likely to be far lower than that of a typical hospital clinic by as much as 10 times.33 Third, patients may have been confused about the exact instructions for reading a chart at home: for example, they may have covered the wrong eye, been wearing the wrong spectacles, or been standing at an incorrect distance. Fourth, motivation may have been lower for a home-based assessment. Given these important differences, our hope was that the HAT would reliably measure VA to within 0.3 logMAR of a conventional acuity chart; in other words, that it would be sensitive to a doubling or halving of visual angle.

We found good agreement between the HAT and the last in-clinic VA measurement. The mean difference in acuity was just more than 1 line of VA, and there was good cross-test agreement in categorical classification of visual impairment. Where differences existed, the HAT erred on the side of safety, tending to underestimate vision compared with the last clinical test. As Figure 3 shows, only 2% of patients were categorized as having better vision by home testing.

Limitations and Strengths

There are several significant limitations to our study design. Our study population was relatively small and we did not test people on the same day as their clinic appointment, meaning that there may have been real change in their vision. This potential bias is the major limitation of our study, but it was unavoidable because the COVID-19 outbreak did not permit us to perform this study in person. Although our patients self-reported stable vision, their eyesight may have deteriorated since their previous assessment. The mean time between the last clinic appointment and the HAT assessment was 11.6 months (range, 1-69 months). There was no association between the time since the previous in-clinic vision measurement and the difference between HAT and in-clinic vision measurements (linear regression, r = 0.067).

Furthermore, our design did not allow us to assess repeatability in people with eye disease; thus, our repeatability data are from a younger group of people with good vision and experience of vision testing. It is unlikely that repeatability would be as good in a patient population, particularly because factors such as glare sensitivity and reduced visual fields may well cause more variability in measurement. Although our population had a range of diseases (eTable in the Supplement), we did not test many people with good vision. We also failed to assess children, people with poor hearing, or people with limited ability to communicate in the English language.

When routine ophthalmology clinics are reopened, direct comparison of the HAT and a standard clinical chart can be performed on the same day. This comparison will help evaluate if the difference in performance between the HAT and logMAR tests of vision are due to features of the test, such as its granularity (acuity lines are separated by 0.3 logMAR), or the difference in testing circumstances (eg, encouragement from a clinic nurse and lighting conditions).

This study also has some strengths. Unlike the American Academy of Ophthalmology16 and College of Optometrists17 tests, our design has a geometric progression of letter sizes, as advocated by the European Standard and the International Council of Ophthalmology.18,19 This design principle allows testing at any distance; for example, extending the test distance to 190 cm allows VA to be measured between 1.0 logMAR (6/60 or 20/200) and 0.0 logMAR (6/6 or 20/20). This would reduce the effect of having an upper acuity limit of 0.1 logMAR for those with good vision; for example, in a routine optometry clinic or a refractive surgery service.

Our charts also include crowding bars. Without crowding bars, letters in the middle of a line are more difficult to identify than the first or last letter on a row, and noncrowded letters overestimate VA in people with many eye conditions, including macular degeneration,34 amblyopia,35 and nystagmus.36

Conclusions

Since data were collected for this study, the HAT has been sent to more than 2000 people receiving telephone assessments of low vision. In an audit of 500 patients, we found that 70.6% were able to complete the test, with the most common reason for noncompletion being the test not arriving in the mail (Ankit Patel, BSc, written communication, August 17, 2020).

Measuring vision at home is unlikely to ever be as accurate as in-clinic assessment by a trained clinician, but these findings show that the HAT can be used to measure vision by telephone for a wide range of ophthalmology outpatients with diverse conditions. Test-retest repeatability is relatively high and agreement in the visual impairment category is good for this sample, supporting the use of printed charts in this context. By avoiding digital devices, the HAT is likely to be accessible to more of the population.

eTable. Primary Diagnosis for Each Outpatient Assessed

References

- 1.Sheldrick JH, Wilson AD, Vernon SA, Sheldrick CM. Management of ophthalmic disease in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43(376):459-462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS Digital . Hospital outpatient activity 2018-19. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-outpatient-activity/2018-19

- 3.Royal College of Ophthalmologists . Management of ophthalmology services during the Covid pandemic. Accessed May 29, 2020. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/RCOphth-Management-of-Ophthalmology-Services-during-the-Covid-pandemic-280320.pdf

- 4.Murdoch I. Telemedicine. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(11):1254-1256. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.11.1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.BenZion I, Helveston EM. Use of telemedicine to assist ophthalmologists in developing countries for the diagnosis and management of four categories of ophthalmic pathology. Clin Ophthalmol. 2007;1(4):489-495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang S, Thomas PBM, Sim DA, Parker RT, Daniel C, Uddin JM. Oculoplastic video-based telemedicine consultations: Covid-19 and beyond. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(7):1193-1195. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0953-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granquist C, Wu Y-H, Gage R, Crossland MD, Legge GE. How people with low vision achieve magnification in digital reading. Optom Vis Sci. 2018;95(9):711-719. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivasan K, Ramesh SV, Babu N, Sanker N, Ray A, Karuna SM. Efficacy of a remote based computerised visual acuity measurement. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(7):987-990. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-301751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PR, Campbell P, Callaghan T, et al. Glaucoma home-monitoring using a tablet-based visual field test (Eyecatcher): an assessment of accuracy and adherence over six months. MedRxiv. Preprint posted online June 1, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.28.20115725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Brady CJ, Eghrari AO, Labrique AB. Smartphone-based visual acuity measurement for screening and clinical assessment. JAMA. 2015;314(24):2682-2683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perera C, Chakrabarti R, Islam FMA, Crowston J. The Eye Phone Study: reliability and accuracy of assessing Snellen visual acuity using smartphone technology. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(7):888-894. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ofcom. Adults: media use and attitudes report 2019. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/149124/adults-media-use-and-attitudes-report.pdf

- 13.NHS Digital. Coronavirus (COVID-19): shielded patients list. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/coronavirus/shielded-patient-list

- 14.Safadi K, Kruger JM, Chowers I, et al. Ophthalmology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020;5(1):e000487. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams AM, Kalra G, Commiskey PW, et al. Ophthalmology practice during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: the University of Pittsburgh experience in promoting clinic safety and embracing video visits. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020;1-9. doi: 10.1007/s40123-020-00255-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Ophthalmology . Snellen chart for adults. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.aao.org/Assets/e2ee3094-abfa-4b4b-b4e2-f56ac4c5c932/637205688825830000/snellen-chart-for-adults-10-feet-1-pdf?inline=1

- 17.College of Optometrists . Home sight test chart. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.college-optometrists.org/uploads/assets/e4899558-1945-49e3-9b3735345fb5a65e/2ba200e5-bed0-4979-90998b72eff71c7d/visual-acuity-chart-for-remote-consultations-14-April-2020.pdf

- 18.International Council of Ophthalmology . Visual Acuity Measurement Standard. International Council of Ophthalmology; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.European Standard . Ophthalmic Optics: Visual Acuity Testing: Standard and Clinical Optotypes and Their Presentation: ISO 8596. European Committee for Standardization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Home distance vision assessment aid. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://homeacuitytest.org/

- 21.Sloan LL. Needs for precise measures of acuity: equipment to meet these needs. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98(2):286-290. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020030282008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307-310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swan AV. Computing maximum-likelihood estimates for parameters of the normal distribution from grouped and censored data. J Royal Stat Soc Ser C (Appl Stat). 1969;18(1):65-69. doi: 10.2307/2346440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. doi: 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd ed. John Wiley; 1981:38-46. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision. Published 2019. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://icd.who.int

- 28.Rosser DA, Cousens SN, Murdoch IE, Fitzke FW, Laidlaw DA. How sensitive to clinical change are ETDRS logMAR visual acuity measurements? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(8):3278-3281. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laidlaw DA, Tailor V, Shah N, Atamian S, Harcourt C. Validation of a computerised logMAR visual acuity measurement system (COMPlog): comparison with ETDRS and the electronic ETDRS testing algorithm in adults and amblyopic children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(2):241-244. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.121715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamm LM, Yeoman JP, Anstice N, Dakin SC. The Auckland Optotypes: an open-access pictogram set for measuring recognition acuity. J Vis. 2018;18(3):13. doi: 10.1167/18.3.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owsley C. Contrast sensitivity. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2003;16(2):171-177. doi: 10.1016/S0896-1549(03)00003-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelli DG, Bex P. Measuring contrast sensitivity. Vision Res. 2013;90:10-14. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cullinan TR, Silver JH, Gould ES, Irvine D. Visual disability and home lighting. Lancet. 1979;1(8117):642-644. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(79)91082-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace JM, Chung STL, Tjan BS. Object crowding in age-related macular degeneration. J Vis. 2017;17(1):33. doi: 10.1167/17.1.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levi DM, Klein SA. Vernier acuity, crowding and amblyopia. Vision Res. 1985;25(7):979-991. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90208-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pascal E, Abadi RV. Contour interaction in the presence of congenital nystagmus. Vision Res. 1995;35(12):1785-1789. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00277-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Primary Diagnosis for Each Outpatient Assessed