Abstract

Background and Aims:

Endotracheal intubation is the predominant cause of airway mucosal injury, resulting in post-operative sore throat (POST), with an incidence of 20-74%, which brings immense anguish to patients. This study was conducted to evaluate and compare the efficacy of nebulised dexmedetomidine and ketamine in decreasing POST in patients undergoing thyroidectomy.

Methods:

Patients were randomly allocated into two groups of 50 each; Group 1 received ketamine 50mg (1mL) with 4mL saline nebulisation, while Group 2 received dexmedetomidine 50μg (1mL) with 4mL saline nebulisation for 15 min. GA was administered 15 min after completing nebulisation. POST monitoring was done at 0,2,4,6,12 and 24h after extubation. POST was graded on a four-point scale (0-3). The statistical analysis were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 17.0. Fisher Exact-t-test, Chi square test, Student t-test, Paired t test and repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for analysis.

Results:

The overall incidence of POST in this study was 17%: POST was experienced by seven patients (14.3%) in ketamine and 10 patients (20.4%) in dexmedetomidine group (P = 0.424). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of POST between the two groups at 0,2,4,6,12 and 24h post-operatively. Severity of sore throat was also significantly lower in both groups at all time points. A statistically significant increase in heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure was noted in ketamine group, post nebulisation.

Conclusion:

Pre-operative dexmedetomidine nebulisation can be utilised as a safe and ideal alternative to ketamine nebulisation in attenuating POST, with less haemodynamic derangement.

Key words: Dexmedetomidine, general anaesthesia, ketamine, nebulisation, sore throat, thyroidectomy

INTRODUCTION

Post-operative sore throat (POST) is a feeling of discomfort usually voiced by the patients during the post-operative recovery period, following surgeries under general anaesthesia (GA). Even though POST is of a lesser concern to the treating physician, it causes significant agony and anguish to the patient, besides bringing immense displeasure with the quality of recovery after anaesthesia.[1]

The reported incidence of POST following GA varies between 20-74%.[2,3] On comparing with other surgeries, the occurrence of POST is shown to be higher in post thyroidectomy patients.[4,5] Numerous trials had been conducted in the past using different pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods for attenuating POST with varying outcomes.[6,7,8,9]

Nowadays, nebulisations are better accepted and tolerated by the patients than gargle, as it spares them from the bitter taste of the drug. The chance of aspiration is also less likely as only a reduced volume is administered when compared to the volume needed for gargle. Ketamine is an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, which has already been in use in the nebulised form, for attenuating POST, due to its anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties.[10,11] Dexmedetomidine is a colorless, tasteless and odorless drug with a selective α-2 adrenergic agonistic action, which causes sedation and analgesia.[12] No study has been conducted so far to evaluate the effectiveness of nebulised dexmedetomidine in decreasing POST. Nevertheless dexmedetomidine has already been in use in a nebulised form, and being a highly lipid soluble agent it has good systemic absorption on transmucosal administration.

Hence, we planned this study to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of nebulised dexmedetomidine and nebulised ketamine in alleviating POST in patients undergoing thyroidectomy under GA.

METHODS

After procuring the approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee (approval number: 07/IEC/19/AIMS-C; dated: 22-6-2019) and informed written consent, 100 patients, in the age group of 18-60 years, with American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (PS) 1-2, who were scheduled to undergo elective thyroid surgery under general anaesthesia (GA) with endotracheal intubation were recruited in this prospective, double-blind, randomised comparative trial (CTRI/2019/07/020082). Exclusion criteria included patients with a history of pre-operative sore throat, upper respiratory tract infection, known allergy to study drug, pregnancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Mallampati grade <2. The enlisted patients, who needed more than one intubation attempt or developed any intra-operative or post-operative complication were also excluded from further evaluation and analysis.

The patients drafted for the study remained fasted for 6 hours prior to surgery. Anaesthesia protocol was standardised for all patients. Patients were randomly allocated into two groups with the help of a computer-formulated randomisation technique, using consecutively numbered opaque sealed envelopes, which were arranged by an anaesthesiologist who did not take part in the study. After opening those envelopes, the nebulisation solution was made ready by an anaesthesia assistant according to the assigned group. The anaesthesia assistant who prepared the solution did not take part in the subsequent analysis of these patients. Patients were also blinded as both the study preparations were colorless and tasteless.

The enrolled study participants were randomised into two groups of 50 each:

Group 1 received ketamine 50mg (1mL) with saline (4mL) nebulisation

Group 2 received dexmedetomidine 50μg (1mL) with saline (4mL) nebulisation,

The drug was delivered using a nebulisation mask for 15 min, with the help of a wall-attached oxygen driven source (8L, 50psi). Fifteen minutes after finishing nebulisation, GA was induced with intravenous (IV) fentanyl 2 μg/kg and IV propofol 2 mg/kg. In order to guarantee minimal trauma, three minutes after giving vecuronium bromide 0.1 mg/kg IV, a swift and a gentle laryngoscopy was performed by a well experienced anaesthesiologist, which lasted less than 15 sec, using a Macintosh blade (size 3 or 4). A sterile single lumen cuffed polyvinyl chloride (PVC) endotracheal tube with an inner diameter of 7-7.5mm in females and 8-8.5mm in males was used for tracheal intubation. Later, the cuff of the endotracheal tube was inflated with room air, till no audible air leakage was detected.

Anaesthesia was maintained using 33% oxygen in nitrous oxide and sevoflurane (1-1.2 MAC). For pain relief, paracetamol 1g IV was administered during surgery, followed by 6th hourly in the post-operative period. Ondansetron 4mg IV was given 30 min preceding the end of surgery and thereafter every eight hours post-operatively. Once the surgery was completed, the oropharynx was gently suctioned using a soft suction catheter and reversal of the neuromuscular blockade was done with neostigmine 50 μg/kg IV and glycopyrrolate 10 μg/kg IV. After regaining complete consciousness, the patient was extubated.

In the post anaesthesia care unit (PACU), sore throat was evaluated by the nursing staff in PACU, who was oblivious of the allocated group of the patient at 0,2,4,612 and 24h after extubation, during the post-operative period. Grading of POST was done using a four-point scale (0-3)[13]: 0 for no sore throat; 1 for mild sore throat (complains of sore throat only when asked); 2 for moderate sore throat (complains of sore throat even without asking); and 3 for severe sore throat (with change of voice or hoarseness, also may be associated with throat pain). Even after 24 hours, if patients still complained of moderate or severe POST, lukewarm saline gargle as well as decongestants would be prescribed for them. If the symptoms still persisted, an oto-rhino-laryngology consultation would be ensured. Haemodynamic variables such as heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) were also recorded at pre-nebulisation, pre-induction, 0,2,4,612 and 24 h after extubation. Any other side effects if present, were also recorded 8th hourly for 24 hours post-operatively.

The primary aim of our study was to examine the effectiveness of dexmedetomidine nebulisation in attenuating POST in adult patients undergoing thyroidectomy under GA, when compared to ketamine nebulization and also to assess the incidence and severity of POST among the two groups. The secondary aims involved the monitoring of side-effects such as cough, dry mouth, post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), hallucinations, respiratory depression and haemodynamic instability in both the groups.

Sample size was formulated from the study,[10] with incidence of POST in Group Saline as 46% and Group Ketamine as 20%. With the power of study at 80% and 95% confidence level, the minimum sample size needed was estimated to be 48 in each group. Considering possible loss during follow-up, we had taken a sample size of 50 in each group.

The statistical calculations were performed using the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows version 17.0 [SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA]. The following statistical methods were applied in the present study. Differences in the age, weight and duration of surgery among the groups were done using Student t-test. ASA grading and differences in the incidence of POST were analysed using Fisher's exact test or Chi-Square test. Continuous data was represented as mean and standard deviation. Paired t-test and repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) were also used for analysis. Paired t-test was used to compare the pre-nebulisation and pre-induction haemodynamic variables. Level of significance was set at 0.05 and all tests were two-sided.

RESULTS

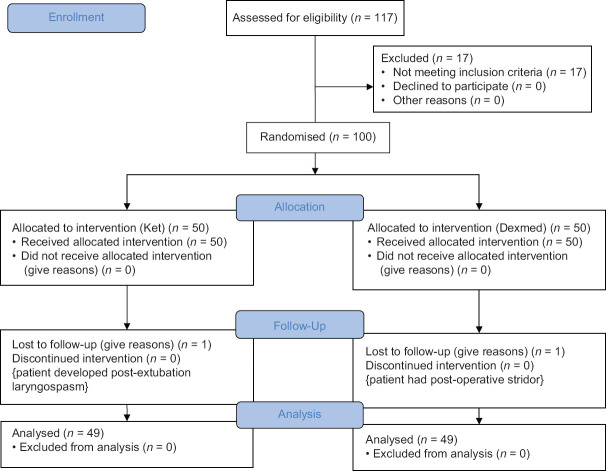

From the 117 patients we screened for the study, 17 patients were excluded. Hence, a total of 100 patients were recruited and assigned into two groups of 50 each. Among them, one patient from ketamine group developed post-extubation laryngospasm and one patient in the dexmedetomidine group had stridor in the post-operative period. Both these patients discontinued the study, while rest of the 98 patients completed the study and were subsequently followed up and analysed [Figure 1]. A comparable distribution of age, gender, body weight, ASA PS and duration of surgery was noted among the two groups [Table 1].

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram (Original)

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | Group 1 (Ketamine) | Group 2 (Dexmedetomidine) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.08 (10.11) | 45.53 (10.002) | 0.801 |

| Weight (kg) | 66.86 (15.75) | 64.10 (6.97) | 0.830 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 100.51 (31.24) | 106.22 (45.01) | 0.365 |

| Male/female | 9/40 | 10/39 | 0.798 |

| ASA PS (grade 1/2) | 16/33 | 15/34 | 0.828 |

Data expressed as Mean (standard deviation) or Number. ASA PS: American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status. *Significant at the 0.05 level

The overall incidence of POST was 17% in our study: POST was experienced by seven patients (14.3%) in ketamine and 10 patients (20.4%) in dexmedetomidine group (P = 0.424). Between the two groups, no statistically significant difference was noticed in the incidence of POST at 0,2,4,612 and 24h post-operatively [Table 2].

Table 2.

Incidence of Post-operative Sore throat

| Time | POST | Group 1 (Ketamine) | Group 2 (Dexmedetomidine) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | Absent | 46 | 44 | 0.461 |

| Present | 3 | 5 | ||

| 2 h | Absent | 42 | 39 | 0.424 |

| Present | 7 | 10 | ||

| 4 h | Absent | 43 | 44 | 0.724 |

| Present | 6 | 5 | ||

| 6 h | Absent | 44 | 44 | 1.0000 |

| Present | 5 | 5 | ||

| 12 h | Absent | 45 | 44 | 0.727 |

| Present | 4 | 5 | ||

| 24 h | Absent | 45 | 44 | 0.727 |

| Present | 4 | 5 |

*Significant at the 0.05 level. POST: Post-Operative Sore throat

Severity of sore throat was also significantly lesser in both groups at all time intervals [Table 3]. Only two patients in dexmedetomidine group and one patient in ketamine group had moderately severe sore throat. None of the patients in both groups developed severe sore throat.

Table 3.

Severity of Post-operative sore throat in patients

| Time | Grades | Group 1 (Ketamine) | Group 2 (Dexmedetomidine) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 0 | 46 | 44 | 0.749 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 2 h | 0 | 42 | 39 | 0.337 |

| 1 | 7 | 8 | ||

| 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 4 h | 0 | 43 | 44 | 0.494 |

| 1 | 6 | 4 | ||

| 2 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 6 h | 0 | 44 | 44 | 1.0000 |

| 1 | 5 | 5 | ||

| 12 h | 0 | 45 | 44 | 0.727 |

| 1 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 24 h | 0 | 45 | 44 | 0.727 |

| 1 | 4 | 5 |

*Significant at the 0.05 level

While considering haemodynamic parameters, a statistically significant rise in HR, SBP and DBP (P = 0.002, P = 0.035 and P = 0.001 respectively) was noted in ketamine group, when pre-nebulisation and pre-induction values were compared [Table 4]. Adverse effects such as PONV, dry mouth, cough, hoarseness, hallucinations or respiratory depression were absent during the entire period of observation.

Table 4.

Comparison of haemodynamic parameters during pre-nebulisation and pre-induction

| Pre Nebulisation | Pre Induction | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | |||

| Group 1 (Ketamine) | 78.90±14.81 | 83.39±11.003 | 0.002 * |

| Group 2 (Dexmedetomidine) | 80.49±11.25 | 77.76±12.88 | 0.072 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | |||

| Group 1 | 119.37±14.48 | 125.37±19.21 | 0.035 * |

| Group 2 | 138.69±18.98 | 134.02±34.52 | 0.299 |

| MABP (mmHg) | |||

| Group 1 | 90.06±10.094 | 92.86±13.416 | 0.154 |

| Group 2 | 103.53±12.17 | 99.69±19.116 | 0.153 |

| DBP (mmHg) | |||

| Group 1 | 75.29±8.32 | 80.59±9.49 | 0.001 * |

| Group 2 | 83.24±11.099 | 83.18±13.97 | 0.980 |

*Significant at the 0.05 level. SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure, MABP: Mean Arterial Blood Pressure, DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure

DISCUSSION

In our study, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of POST between the two groups at 0, 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24h post-operatively. A significant reduction in the severity of sore throat was noticed in both groups at all time points during the first post-operative day. Moderately severe sore throat was noted only in two patients in dexmedetomidine group and in one patient in ketamine group. No patients in both groups developed severe sore throat.

Post-operative sore throat occurs probably as a consequence of injury to the mucosa of pharynx during laryngoscopy or as an injury to tracheal tissues either during intubation or extubation, which may trigger an aseptic inflammatory reaction in the tracheal mucosa.[14,15] Chan et al.[16] in his study using ketamine gargle, came to a conclusion that the topical action of ketamine reduced the incidence of POST more than the systemic effect. Also, Ahuja et al.[10] and Thomas et al.[11] proposed that pre-operative administration of nebulised ketamine significantly declined the incidence and severity of sore throat in the post-operative period. Hence, the topical influence of ketamine nebulisation, which abated the local inflammation and also triggered a peripheral analgesic effect, with its NMDA-antagonistic and anti-inflammatory actions can be the reason for the significant attenuation of POST in our ketamine group.[10,11,13,17]

Many multi-faceted protective functions of dexmedetomidine which even include the inhibitory action on pro-inflammatory cytokine production, have been disclosed by several pre-clinical studies on murine models.[18,19,20] Zhang and Zhang[21] in their study concluded that dexmedetomidine decreased inflammatory responses, thereby reducing the chances of cerebral injury following cardio pulmonary bypass in patients undergoing cardiac valve replacement. They established a significant reduction in the serum concentrations of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-6 and S100β in their study. Similar results with dexmedetomidine were also obtained by Zhu[22] in his study in patients with one lung ventilation. Also, Li et al.[23] conducted a meta-analysis to scrutinise the available data on the effectiveness of dexmedetomidine on inflammatory modulators, when used peri-operatively. They concluded that when administered along with GA, dexmedetomidine produced remarkable reduction in the levels of serum IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α post-operatively. In view of these anti-inflammatory effects shown by dexmedetomidine, many authors are now advocating its pre-emptive administration for better results.[24,25] Iirola et al.[12] in their study evaluating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of intranasal dexmedetomidine observed a rapid and efficient absorption of dexmedetomidine when administered intranasally. Therefore, the significant decline in the incidence and severity of POST that we noted in our dexmedetomidine group can be attributed to the significant reduction in the inflammatory mediators caused by nebulised dexmedetomidine when administered pre-operatively, along with its analgesic action.

Following nebulisation, a marked increase in the pre induction values of haemodynamic parameters such as HR, SBP and DBP was recorded in the ketamine group in our study, which may be because of the systemic absorption of ketamine. Similar results were also obtained by Segaran et al.[26] in the ketamine group in their study, while comparing and evaluating the efficacy of nebulised magnesium sulphate with nebulised ketamine in diminishing POST. The studies done by Ahuja et al.[10] and Thomas et al.[11] showed no such haemodynamic variations.

The overall incidence of POST after GA, was reported to be between 20-74%,[2,3] whereas following total thyroidectomy, the incidence of POST was as high as 80%. Kadri et al.[4] in his study postulated that POST was even dependent on the types of thyroid surgery and he noticed that 59.6% of patients had POST following partial thyroidectomy, 87.7% following subtotal thyroidectomy and 100% following total thyroidectomy. Jung et al.[5] also had similar findings, where he recorded an incidence of POST of 83.9% in patients after total thyroidectomy. In our study majority of the patients underwent total thyroidectomy, only 11 patients had hemi, near total or subtotal thyroidectomy. Because of the minimal number of patients who had surgeries other than total thyroidectomy in our study, we were not able to compare POST with the different types of thyroid surgeries. However, even with the majority of patients undergoing total thyroidectomy, our study showed an overall incidence of POST of only 17%, with only 20% in dexmedetomidine group. The incidence of POST in ketamine group (14.3%) was much lower in comparison to the study done by Ahuja et al.[10] (20%), while it was comparable to the study done by Thomas et al.[11] (14.6%), where both these studies evaluated the effectiveness of nebulised ketamine in reducing POST.

From many previous studies, numerous factors have been recognised as those leading to POST, including patient age, gender, cuff design variations, intra cuff pressure as well as endotracheal tube size.[8,9,27] But, our study showed a comparable distribution of age, gender, body weight, ASA PS and duration of surgery among both groups.

There are a few limitations to our study. Monitoring of cuff pressure was not done during GA and no sedation scale was used during the study. The dose we used for both drugs was a fixed dose. We were also unable to measure the serum levels of the studied drugs and follow-up analysis was not done beyond 24 h.

CONCLUSION

Pre-operatively administered dexmedetomidine nebulisation is as effective as ketamine nebulisation in attenuating POST, with less haemodynamic derangement. Hence, nebulised dexmedetomidine may be considered as a safe alternative to nebulised ketamine for decreasing POST.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Mr. Kevin Suresh, who conducted the statistical analysis of the data of our study. We also express our sincere gratitude to all the patients who participated in the study and to the staff of our Department of Anaesthesiology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:652. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehmann M, Monte K, Barach P, Kindler CH. Postoperative patient complaints: A prospective interview study of 12,276 patients. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arts MP, Rettig TCD, de Vries J, Wolfs JFC, in't Veld BA. Maintaining endotracheal tube cuff pressure at 20 mm Hg to prevent dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery; protocol of a double-blind randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadri I, Khanzada T, Samad A. Post-thyroidectomy sore throat: A common problem. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25:408–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung TH, Rho J-H, Hwang JH, Lee J-H, Cha S-C, Woo SC. The effect of the humidifier on sore throat and cough after thyroidectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;61:470–4. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2011.61.6.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarkar T, Mandal T. Preoperative oral zinc tablet decreases incidence of postoperative sore throat. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:409. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_959_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh NP, Makkar JK, Wourms V, Zorrilla-Vaca A, Cappellani RB, Singh PM. Role of topical magnesium in post-operative sore throat: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63:520–9. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_856_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Boghdadly K, Bailey CR, Wiles MD. Postoperative sore throat: A systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2016;71:706–17. doi: 10.1111/anae.13438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puthenveettil N, Kishore K, Paul J, Kumar L. Effect of cuff pressures on postoperative sore throat in gynecologic laparoscopic surgery: An observational study. Anesth Essays Res. 2018;12:484–8. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_72_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahuja V, Mitra S, Sarna R. Nebulized ketamine decreases incidence and severity of post-operative sore throat. Indian J Anaesth. 2015;59:37–42. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.149448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas D, Bejoy R, Zabrin N, Beevi S. Preoperative ketamine nebulization attenuates the incidence and severity of postoperative sore throat: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Saudi J Anaesth. 2018;12:440–5. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_47_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iirola T, Vilo S, Manner T, Aantaa R, Lahtinen M, Scheinin M, et al. Bioavailability of dexmedetomidine after intranasal administration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:825–31. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canbay O, Celebi N, Sahin A, Celiker V, Ozgen S, Aypar U. Ketamine gargle for attenuating postoperative sore throat. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:490–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudra A, Ray S, Chatterjee S, Ahmed A, Ghosh S. Gargling with ketamine attenuates the postoperative sore throat. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:40–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S-H, Han S-H, Do S-H, Kim J-W, Rhee K, Kim J-H. Prophylactic dexamethasone decreases the incidence of sore throat and hoarseness after tracheal extubation with a double-lumen endobronchial tube. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1814–8. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318185d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan L, Lee ML, Lo YL. Postoperative sore throat and ketamine gargle. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:97. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu MM, Zhou QH, Zhu MH, Bo Rong H, Xu YM, Qian YN, et al. Effects of nebulized ketamine on allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in actively sensitized Brown-Norway rats. J Inflamm Lond Engl. 2007;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taniguchi T, Kidani Y, Kanakura H, Takemoto Y, Yamamoto K. Effects of dexmedetomidine on mortality rate and inflammatory responses to endotoxin-induced shock in rats. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1322–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000128579.84228.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagmurdur H, Ozcan N, Dokumaci F, Kilinc K, Yilmaz F, Basar H. Dexmedetomidine reduces the ischemia-reperfusion injury markers during upper extremity surgery with tourniquet. J Hand Surg. 2008;33:941–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sukegawa S, Higuchi H, Inoue M, Nagatsuka H, Maeda S, Miyawaki T. Locally injected dexmedetomidine inhibits carrageenin-induced inflammatory responses in the injected region. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:473–80. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Zhang W. Effects of dexmedetomidine on inflammatory responses in patientsundergoing cardiac valve replacement with cardiopulmonary bypass. Chin J Anesthesiol. 2013;33:1188–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu H. Effects of dexmedetomidine on intrapulmonary shunt and inflammatory response in patients. Chin J Postgrad Med. 2012;35:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Li Y, Tian S, Wang H, Wu H, Zhang A, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of perioperative dexmedetomidine administered as an adjunct to general anesthesia: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep12342. doi: 10.1038/srep12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang SH, Kim YS, Hong TH, Chae MS, Cho ML, Her YM, et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine on inflammatory responses in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:480–7. doi: 10.1111/aas.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofer S, Steppan J, Wagner T, Funke B, Lichtenstern C, Martin E, et al. Central sympatholytics prolong survival in experimental sepsis. Crit Care. 2009;13:R11. doi: 10.1186/cc7709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segaran S, Bacthavasalame AT, Venkatesh RR, Zachariah M, George SK, Kandasamy R. Comparison of nebulized ketamine with nebulized magnesium sulfate on the incidence of postoperative sore throat. Anesth Essays Res. 2018;12:885–90. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_148_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu B, Bao R, Wang X, Liu S, Tao T, Xie Q, et al. The size of endotracheal tube and sore throat after surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]