Abstract

In the heart, Ca2+ participates in electrical activity and myocardial contraction, which is closely related to the generation of action potential and excitation contraction coupling (ECC) and plays an important role in various signal cascades and regulates different physiological processes. In the Ca2+ related physiological activities, CaMKII is a key downstream regulator, involving autophosphorylation and post-translational modification, and plays an important role in the excitation contraction coupling and relaxation events of cardiomyocytes. This paper reviews the relationship between CaMKII and various substances in the pathological process of myocardial apoptosis and necrosis, myocardial hypertrophy and arrhythmia, and what roles it plays in the development of disease in complex networks. This paper also introduces the drugs targeting at CaMKII to treat heart disease.

Keywords: CaMKII, Ca2+, cardiomyocyte, necrosis, hypertrophy, arrhythmology

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+), one of the most common signal transducers, plays many important regulatory roles in cardiomyocytes [1]. It can mediate various biological functions, such as muscle contraction, extracellular swallowing, neuronal activity and triggering programmed cell death [2]. In the initial stage of action potential, Ca2+ which flows into L-type Ca2+ channel through myoplasma voltage gating triggers sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) to release a large amount of Ca2+. This process of myocardial contraction and blood drawing driven by Ca2+ is called excitation contraction coupling (ECC) [3]. The transport mechanism of Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes includes Ca2+ cycling between cytoplasm and extracellular space and Ca2+ cycling between cytoplasm and calcium pool, especially SR. In the place where the distance between T-tubules and SR is very close, dyad is very important for intracellular Ca2+ cycle [4], Dyad is regarded as a signal link related to cardiac contraction, and it is composed of L-type Ca2+ channel clusters on SR, which are closely distributed to form RyRs clusters. Cardiac dyad may help regulate the release of Ca2+ in SR during systole [5].

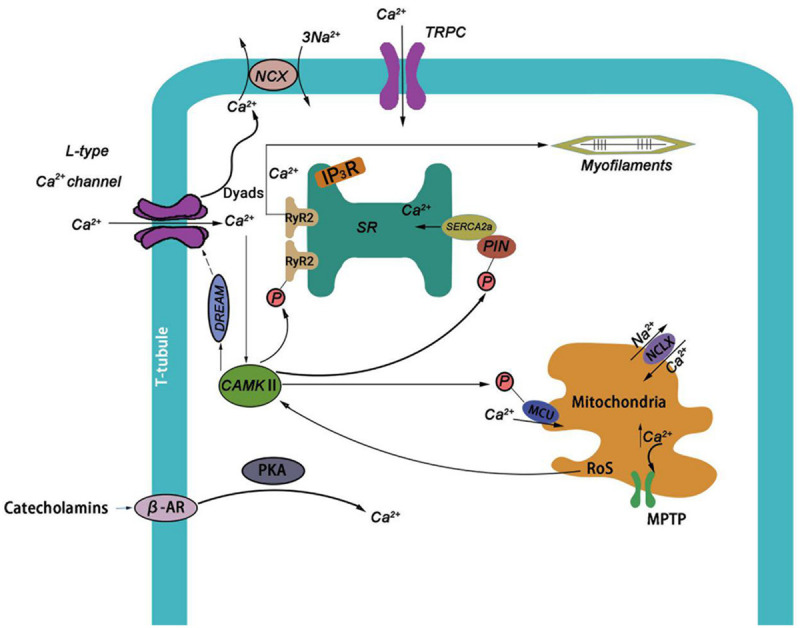

In the initial depolarization phase of AP, the probability of LCC opening increases, which allows Ca2+ to enter dyad. SR is the main intracellular Ca2+ storage cell [6]. Ca2+ release in SR is mediated by RyR2 which is a special Ca2+ release channel [7]. With the increase of Ca2+ concentration in dyad, Ca2+ binds to RyR2s, which increase the probability of receptor opening. When calcium triggers the release of calcium, the large opening of RyR2 receptor results in Ca2+ releasing from JSR. Ca2+ is rapidly accumulated in dyad and diffuses to cytoplasm. Ca2+ in the cytosol binds to and activates cardiac troponin C (TNC), and then initiates myofilament contraction [8]. The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) excretes one Ca2+ every three Na+, which is the main way to excrete Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes (Figure 1) [9]. During the diastolic phase, Ca2+ enters SR from SERCA2a, or enters extracellular space from NCX, which causes myocardial relaxation. In addition, Ca2+ released from SR enters the cytoplasm rapidly, and then enters SR or extrudes out of the cells, which causes a transient wave of Ca2+ throughout the cardiomyocytes.

Figure 1.

Ca2+ and CaMKII in cardiomyocytes. Ca2+ can enter cardiomyocytes through LTCC, TRPC and other channels, β-AR can also regulate the influx of Ca2+. When Ca2+ increases to a certain extent in dyads, it will combine with RyR2 and cause CICR. When a large amount of Ca2+ influx into the cytoplasm, it can promote the contraction of cardiomyocytes. Ca2+ can be transported out of cells by NCX. The increase of Ca2+ concentration can activate CaMKII, which can phosphorylate IP3R and increase the opening of RyR, and also phosphorylate PLN and promote the absorption of SR Ca2+. DREAM, a downstream factor stimulated by CaMKII, inhibited the opening of LTCC by negative feedback. Meanwhile, under the activation of CaMKII, MCU would be phosphorylated to promote Ca2+ inflow into mitochondria, and a large increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration would cause the opening of MPTP channels and trigger cell apoptosis.

The activity of Ca2+ channel and exchanger involving EC coupling is regulated by various mechanisms and signal pathways. IP3 (inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate) is the substrate produced by phospholipase C (PLC), hydrolysis of ptdlns (4, 5) P2 (phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate), which acts as the second messenger to regulate Ca2+ release by stimulating IP3 receptors [10]. The increase of paracrine or autocrine of Endothelin-1 (ET-1) can promote the production of IP [11]. Protein kinase A (PKA) can phosphorylate IP3R (Inositol trisphosphate receptor) and enhance its Ca2+ release at a lower concentration of IP3 [12]. TRP channel plays an important role in regulating cell contraction, proliferation and death. The integrated stimulation is transmitted to the downstream signal pathway through Ca2+. In cardiomyocytes, especially TRPC channel, it is an important regulatory factor of Ca2+ cycle, which is related to calcineurin and other effectors to regulate and control the physiological and pathological processes of the heart [13,14]. PKA and CaMKII play an important role in the regulation of cardiac Ca2+ circulation. Activated β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) stimulates adenylate cyclase (AC) to activate PKA and regulate calcium uptake in SR. CaMKII has a similar function with PKA, and is also activated by sympathetic nerve to play a role. CaMKII can also phosphorylate Ca2+ and Na+ channels, change ICa and lNa gating, in order to prolong APD time and improve the possibility of early depolarization. CaMKII has a more important and long-term impact on Ca2+ cycle [15].

Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II

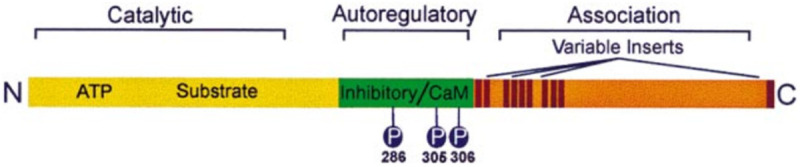

CaMKII is a polymer compound composed of 12 monomers [16]. Each CaMKII monomer has three main domains: N-terminal catalytic domain, self regulatory domain and C-terminal association domain (Figure 2 and Table 1) [17,18]. The catalytic activity of the self regulatory domain which has the binding site with Ca2+/CaM is relatively low without stimulation, and regulates the activation state through binding Ca2+/CaM and self phosphorylation [18]. When the intracellular Ca2+ concentration increases, it can be keenly sensed by the regulatory domain, and thus Ca2+/CaM is bound to liberate the catalytic domain and activate CaMKII [19,20]. When the concentration of Ca2+ increases, CaMKII will self phosphorylate at threonine 287 (T287), and destroy the interaction between self inhibition domain and catalytic site [21]. Autophosphorylation occurs between different subunits of CaMKII holoenzyme, and the polymerization structure of CaMKII hol enzyme increases the relative concentration of subunits when autophosphorylation occurs, which makes the built-in kinase cascade possible [18]. T287 autophosphorylation can significantly increase the affinity of CaMkinase to calmodulin [20]. Phosphorylation of substrate subunits at T287 depends on Ca2+/CaM binding [22]. Self phosphorylation of T287 can produce CaM capture and maintain the activity of CaMKII [23]. The N-terminal of the binding domain of Ca2+/CaM and CaM produce high affinity binding after self phosphorylation [24]. It has also been proved that with the help of CASK, when T305/T306 site is self phosphorylated, the sensitivity of CaM binding domain to CaM will be lost [25,26].

Figure 2.

Linear diagram of a prototypical CaMKII subunit.

Table 1.

Structure and function of CaMKII subunit

| Domain | Structure and function |

|---|---|

| N-terminal catalytic domain | The catalytic domain is autoinhibited by a pseudosubstrate autoregulatory sequence that is disinhibited following Ca2+/CaM binding. |

| self regulatory domain | The association domain produces the native form of the enzyme, a multimeric holoenzyme composed of 12 subunits. |

| C-terminal association domain | Conserved sites of autophosphorylation are indicated in the autoregulatory region. |

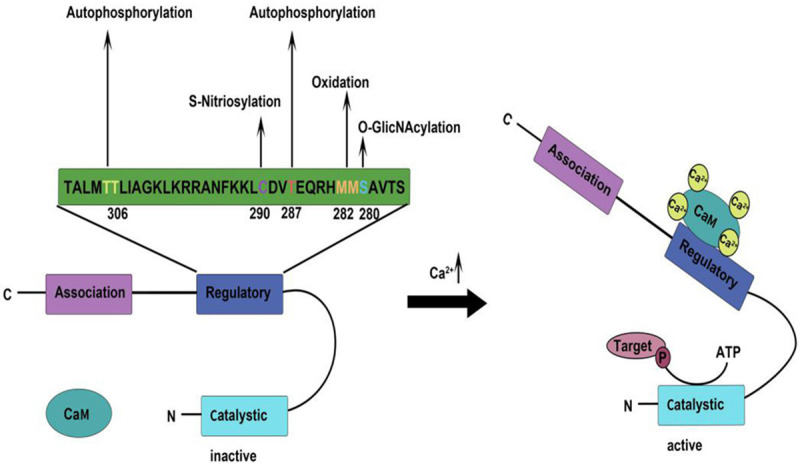

In addition to autophosphorylation, there are several other post-translational modifications. The nitrosylation of Cys290 site promotes the NO-induced CaMKII to develop and live [27], and increases Ca2+ spark frequency after activation [28]. The direct oxidation of M281/282 to CaMKII is mainly through the H2O2 activation pathway, and the direct oxidation at Met281/282 site is possible to increase the coordination activities of CaMKII [29]. When the blood glucose rises sharply, O-GlcNAc covalently will modify CaMKII. CaMKII modified by O-GlcNAc at Ser279 can activate CaMKII autonomously, which can produce molecular memory even after calcium concentration decreases [30]. The inactivation of CaMKII also involves some complex mechanisms, one of which is to block the signal to inhibit CaMKII by expressing inhibitor protein. Besides, PEP-19 indirectly mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ flow and antagonizes the activation of CaMKII [31]. PP2A belongs to heterotrimer, and multiple PP2A holoenzymes may contribute to the dephosphorylation of soluble CaMKII (Figure 3) [32].

Figure 3.

Structure, regulatory sites and activation mechanism of CaMKII. CaMKII includes catalytic, regulatory and association domains. Different stimuli can act on the corresponding sites at regulaory domain, directing CaMKII to undergo autophosphorylation or post-translational modification. When Ca2+ concentration increases, the Ca2+/CaM complex binds to the self-regulatory domain, which releases its inhibition of the catalytic domain, enabling it to phosphorylate the target.

CaMKII can regulate the intracellular calcium content. CaMKII is distributed in the high-density cardiomyocytes near the T-tube, and in the vicinity of mitochondria and nuclei, close to RyR2 channels of LTCC and SR, which can regulate calcium release triggered by calcium in cells [33]. It has been suggested that CaMKII can inhibit the expression of LTCC by activating downstream regulatory elements through combination with the transcription factor Dream, which forms a negative feedback mechanism and inhibits the inflow of Ca2+ [34]. IP3R2, the main subtype in cardiomyocytes, will be phosphorylated by CaMKII at specific sites, which will cause the release of nuclear Ca2+ mediated by IP3R and enhance the opening of RyR [35,36]. CaMKII can phosphorylate PLN, which promotes the reabsorption of SR Ca2+ and the relaxation of muscle cells, and counteracts the enhanced release of Ca2+ [37]. RyR in sarcoplasmic reticulum is the main target of phosphorylation of CaMKII. CaMKII can phosphorylate RyR2 at ser2815, change the probability of RyR opening, increase the leakage of SR calcium into the cytoplasm, and enhance the spontaneous release of SR Ca2+ (Figure 1) [38].

CaMKII is also distinguished by its four isomers (α, β, γ, δ), with different expression rates in different types of tissue, α and β are mainly in neurons [39], δ and some γ are mainly located in cardiomyocytes [40]. At present, CaMKIIδ was studied most and fully. CaMKIIδ can induce cardiac hypertrophy after catecholamine stimulation [41]. It mediates histone deacetylase (HDAC) phosphorylation, regulation of transcription, and stress overload [42]. Other studies have shown that the activation of CaMKIIδ can mediate inflammation-driven remodeling [43]. The activated CaMKIIδ triggers inflammatory bodies in cardiomyocytes by NF-κB and ROS signals and induces the production of chemokines, thus promoting macrophage infiltration [44]. δA is mainly expressed in neonatal cardiomyocytes [45], and overexpressed in plasma membrane and T-tube [46]. The nuclear localization sequence is mainly located in CaMKIIδB, while CaMKIIδC is mainly located in cytoplasm [47].

The Increasing expression of CaMKIIδA can enhance EC coupling [48]. CaMKIIδB plays an anti apoptotic role by binding the necessary transcription factor GATA4 and protein Bcl-2 to the premotor region, which can inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis after adriamycin treatment [49]. CaMKIIδC can improve diastolic function [50], and it can significantly enhance the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes induced by β1-adrenergic receptor (β1AR) [51]. It is significant to study the relationship between these splicing variants and different stages of heart development and disease.

The role of CaMKII in heart disease

Myocardial apoptosis and necrosis

In general physiological state, the uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria plays an important role in metabolic response, which is used to increase the activity of tricarboxylic acid cycle to increase the reduction equivalent, mainly in the form of NADPH, thus promoting oxidative phosphorylation and the production of ATP. If there are too much Ca2+ in mitochondria, it will cause apoptosis or programmed necrosis through open MPTP. It is evidenced that activated CaMKII can induce harmful cardiac remodeling and cardiomyocyte apoptosis [52,53]. Under the continuous stimulation of Angiotensin ll (AngII), cardiomyocytes will produce ROS, and through PKA mediating activation of CaMKII, ROS can also increase the activity of CaMKII by oxidation of M281/282 site, aggravate heart injury, and even resulted in the increase of mortality after myocardial infarction [54,55]. About 10% of CaMKII is located in mitochondria [56]. Compared with WT, there is no significant increase in the expression of CaMKII in Epac1-/- cardiac myocytes, and similar results are obtained by transfection of Epac1∆2-37 into WT cardiac myocytes and immunoprecipitation assay, and these results suggest that MITEpac1 (mitochondrial exchange protein directly activated by cAMP 1) is involved in the mitochondrial localization of CaMKII. Knockout of CaMKIIδ with specific siRNA can prevent IDH2 phosphorylation induced by 8-CPT-AM. Finally, some studies show that MITEpac1-CaMKII pathway inhibits the activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2) and reduces ROS detoxification, so as to promote the death of cardiomyocytes in the process of I/R [57].

Inhibition of SR dependent phosphorylation of CaMKII can prevent I/R damage induced by CaMKII, which is closely related to RyR2, PLN, and two substrates of CaMKII at SR level [58]. Activated CaMKIIi is important for the activity of calcium-regulated/mediated [59]. In the model of cardiac arrest, after 30 minutes of cardiac arrest and the same time of extraporal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) reperfusion, the ratio of PCaMKII T287 to total CaMKII in the experimental group is almost twice that of the control group. After cardiac arrest/reperfusion in vivo, the phosphorylation state of RyR2 and PLN, which are the common targets of CaMKII and PKA, is also detected. The results clearly shows that the CaMKII rather than PKA pathway is activated after cardiac arrest, thus maintaining the increase of CICR triggered by the surge of catecholamine and reactive oxygen species [60]. The phosphorylation level of Thr17-PLN and PThr17-PLN is used as the index of CaMKII activity. It is found that HMGB1 stimulates RAGE to enhance CaMKII activation, and CGP, a β1AR blocker, which could completely eliminate CaMKII induced by HMGB1. Under the influence of hormone and metabolism, RAGE and β1AR can form a protein complex, activate the common downstream signal molecule CaMKII, and result in the death and remodeling of cardiac myocytes [61].

Ox LDL is the key to heart injury. In the presence of ox LDL, the use of KN93 (CaMKII inhibitor) and Mn (III) TABP (ROS scavenger) significantly reduce the apoptosis rate, which suggests that ox LDL stimulates apoptosis through CaMKII and ROS pathways [62]. RIP3 binds directly to CaMKII and makes it phosphorylate at T287 and oxidize at M281/282, which can cause various heart diseases [63]. RIP3 can also bind to MLKL, and the T357 and S358 sites of MLKL are phosphorylated, which can cause cell necrosis [64]. In SNI, chronic pain is induced, and the phosphorylation of RIP3 reduces the expression of TNFα, which in turn inhibits the phosphorylation of MLKL and CaMKII, and significantly reduces the myocardial necrosis of SNI mice induced by myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (MI/R) [65]. It has been proved that CaMKII can regulate the expression of membrane surface and current density of KATP channels in the heart [66]. In healthy hearts, CaMKII phosphorylates Kir6. 2 pore to form KATP channel subunit, which promotes the endocytosis of KATP channel [67]. Cardiac KATP pathway is closely linked with cellular metabolic signaling pathway, which plays an important role in the coordination of myocardial energy health [68], and can also reduce the injury caused by myocardial ischemia-reperfusion [69]. Under pathophysiological conditions, such as the non ischemic heart failure model induced by ligation of the transverse aorta, CaMKII will be continuously activated, the expression of KATP channel on the membrane surface will be significantly reduced, and the energy consumption of the heart will increase. Therefore, it is helpful for the development of myocardial injury, cell death and heart failure [70]. In vitro kinase test, CgA fragment catestatin (CST) strongly inhibits the activity of CaMKIIδ in a dose-dependent manner. In vivo, CST could alleviate the phosphorylation of RyR2 and PLB in CaMKIIδ dependent. In post infarction HF mice, chromogranin A(CGA)-CST conversion is impaired, and the inhibition of CaMKIIδ is reduced, which will increase the mortality of cardiomyocytes [71]. It is speculated that CaMKII plays a significant regulatory role by preventing uncontrolled necrosis in myocardial injury.

Myocardial pressure overload and hypertrophy

Cardiac hypertrophy is an adaptive cardiac response to cardiac stress. Recent evidence strongly suggests that CaMKII is a key regulator of cardiac pathological hypertrophy [72], and its mechanism is being explored by the further studies. The continuous increase of intracellular calcium concentration can activate calcineurin (PP2B), which combines with the activated nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT). The rapid transfer of NFAT to the nucleus can induce pathological cardiac hypertrophy [73,74]. Cellular hypertrophy and fibrosis are important consequences of cardiac remodeling caused by obesity or hyperlipidemia. It is reported that free fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, can induce cellular hypertrophy [75]. In a diabetic model, impaired intracellular Ca2+ metabolism activates CaMKII, promotes ROS production and brings about cardiac remodeling [76]. RT-qPCR analysis shows that 12 hours after palmitate treatment, the proliferation markers (ANP and BNP) and fibrosis markers (TGF-β1, collagen1) significantly increase, while CaMKII inhibitor has a significant inhibitory effect on them. These results indicate that CaMKII plays an important role in mediating hypertrophy and fibrosis of H9c2 cells [77]. Previous studies indicate that overexpression of STAT3 can aggravate pathological cardiac hypertrophy [78]. Some studies suggest that CaMKII can promote the expression of STAT3, and IL-6 can activate the CaMKII-STAT3 pathway in cardiac hypertrophy [79,80]. A mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy is established by TAC surgery. ANG-II treating mice shows higher heart/body weight and heart weight/length ratio. Echocardiography suggests that the left ventricular wall of ANG-II group is thinner than that of PBS group. But after the silence of CaMKII, EF and FS in the Silence Group are lower than those in the control group, which suggests that the silence of CaMKII can eliminate the myocardial hypertrophy induced by ANGII [81].

A previous report suggests that TRPC is a cation selective internal flow channel, overexpression can cause cardiac hypertrophy, and Ca2+ can regulate gene transcription of TRPC through CaMKII and calinerin [82,83]. It has been evidenced that TRPA1 expression increase in hypertrophic heart, and HC and TCS (TRPA1 blocker) can reduce myocardial hypertrophy in vivo, and can significantly reduce the pressure overload causing autophosphorylation of CaMKII, indicating that the activation of CaMKII may be necessary for TRPA1 mediating myocardial hypertrophy [84]. At the same time, the combination of calcineurin and CaMKII inhibitor can significantly reduce hypertrophic response induced by IGF-IIR [85]. It has been proved that the expression of cardiac hypertrophy gene induced by urotensin II (UII) requires the participation of CaMK kinase [86]. UII is used to stimulate the primary culture of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes for 48 h. The cell size, protein/DNA content and intracellular Ca2+ increase, and the phosphorylation of CaMKII and its downstream targets PLN and SERCA2a increase. KN-93 treatment can reverse all of these effects of UII. The results show that UII could induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through the upregulation of the signaling pathway of the PLN Thr17-phosphorylation mediated by CaMKII [87].

In the heart samples of HCM patients, the phosphorylation of CaMKII and its downstream targets also increase [88]. In HCM, the increase of INaL will cause the overload of Na+ in cells, which will damage the NCX mediating Ca2+ extrusion, give rise to Ca2+ overload, and then enhance the activity of CaMKII through calmodulin binding [89]. The activated CaMKII can move to the nucleus and phosphorylate the hystone deacetylase (HDAC), thus relieving the inhibition of myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) - controlled genes and promoting cardiac hypertrophy [90]. In addition, recent evidence reveals the key role of mitochondrial dynamics in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy [91]. Drp1, a mitochondrial mission protein, is used to feed rats with high salt food to promote hypertension. Mdivi1 (an inhibitor of drp1) is used or not used at the same time, and then myocardial hypertrophy is evaluated. High salt fed rats show left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis, while mdivi1 inhibited them by inhibiting calcineurin and CaMKII [92].

Arrhythmia

It is well known that late INa elevation is closely related to the development of systolic dysfunction and arrhythmia [93]. The disorder of cardiac Ca2+ circulation is closely related to the late INa. The results show that the late INa dependent increase induced by Ca2+ leakage of SR is also mediated by CaMKII in mouse cardiomyocytes [94]. The enhanced INa of mouse cardiomyocytes results in the increase of Ca2+ spark frequency and Ca2+ transient amplitude. Inhibition of CaMKII or PKA attenuates the late INa dependent induction of Ca2+ leakage of SR. This study shows that the disturbance of phosphatase/kinase balance brings about the destruction of Ca2+ circulation through CaMKII and PKA dependent pathways [95]. In HCM samples, CaMKII increases the Na+ channel phosphorylation level by 2.5 times, which may lead to the increase of INaL in HCM cardiomyocytes, thus resulting in AP prolongation and Na+ overload [96]. Compared with normal myocardium, the rate of ICAL inactivation observed in HCM cardiomyocytes is slower [97]. CaMKII increases phosphorylation of β-subunit of L-type Ca2+ channel, thus delaying repolarization [98].

The increase of ROS will cause the oxidation of RyR2, which will result in SR Ca2+ leak and promote arrhythmia in mice [99,100]. ROS can enhance the response of CaMKII to the increase of Ca2+, and change the excitation contraction coupling of the heart [101]. Fluorescein staining shows that the increase of ROS production in MDX mouse ventricular myocytes is consistent with the increase of ox CaMKII in Western blotting. The results showed that inhibition of ROS or ox CaMKII can protect Ca2+ in arrhythmogenic cells and prevent ventricular arrhythmia in DMD mice [102]. There are many factors that cause arrhythmia. Excessive drinking can easily induce arrhythmia [103]. The activation of JNK is helpful for liver toxicity and other organ damage induced by alcohol [104]. CaMKII of WT mice labeled by human influenza hemagglutinin is overexpressed in HEK293 cells after 24 hours of alcohol exposure. It is found that drinking alcohol significantly increases the activity of CaMKII, but when JNK2 inhibitors appeare, this will not happen. The pure active human JNK2 protein is incubated with the anti ha antibody immunoprecipitated CaMKII of WT mice or mutant CaMKIIT286A protein. It is found that activated JNK2 significantly increase the phosphorylation of HA labeled CaMKII protein. The results show that JNK2 is activated by alcohol, and then JNK2 phosphorylates CaMKII protein and enhances the activity of CaMKII in cells, which results in atrial arrhythmia [105].

Catecholaminergic pleomorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is an arrhythmia caused by RyR2 gene mutation [106]. CaMKII phosphorylated RYR2-S2814 can promote Ca2+ leakage of RyR2 in diastolic period and promote arrhythmia [107]. A human engineering tissue model based on CPVT is constructed in a laboratory. In the model, when CPVT tissue is stimulated by rapid pacing and catecholamine, it is easy to have reversible rhythm. The Ca2+ spark and depolarization rate in CPVT related tissues are significantly reduced by cell permeable AIP. RYR2-S2814 phosphorylation by CaMKII is found to be necessary for the cause arrhythmia potential in CPVT tissue. These studies indicate that CaMKII is a key signal molecule in the pathogenesis of CPVT [108]. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 can regulate the steady state of phosphorus and calcium [109]. It can promote the expression of PKC, increase INaL, bring about abnormal oxidation of CaMKII and calcium treatment, and induce atrial arrhythmia [110,111]. The central role of CaMKII in arrhythmia pathology makes it an attractive therapeutic target.

Treatment methods for CaMKII

CaMKII is a downstream target with a variety of agonists and has been regarded as a conventional target for the treatment of heart disease. KN-93, a common CaMKII inhibitor, can affect many ion channels, including LTCC [112]. One study finds that the use of CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 in the experimental substance reduces the activity of CaMKII in AF with noradrenaline [113]. SMP-114 is an ATP competitive inhibitor of CaMKII, which has a significant inhibitory effect on VEGF production of macrophages in rheumatoid synovium fluid and can be used in the treatment of arthritis [114-116]. It has been proved that 10 mol/L SMP-114 can greatly inhibit the activity of CaMKII [117]. The reduction of VEGF production by smp-114 is due to its inhibition of CaMKII, similar with KN-93 [118]. It is found that SMP-114 strongly reduces the correlation of SRCa2+ leak and arrhythmia in cardiac myocytes, and improves post-rest potentiation of cardiomyocyte Ca2+ transients and contractility. In addition, it can inhibit the late sodium current [119]. AS105 is also a high affinity ATP competitive CaMKII inhibitor [120]. Cardiomyocytes of heart failure mice overexpressing CaMKIIδC are isolated from the donor, and AS105 effectively reduced the leakage of SRCa2+ in diastolic phase. In addition, the ability of SR to accumulate Ca2+ is enhanced in the presence of SR Ca2+ [121].

All trans retinoic acid (RA) can alleviate the transition from adaptive cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure, and also can alleviate the ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction [122,123]. It has been shown that the absence of Cellular tretinoin binding protein 1 (Crabp1) leads to the over activation of CaMKII, which suggests that Crabp1 has a protective effect on the reduction of inadaptable cardiac remodeling [124]. Under the induction of isoproterenol (ISO), mice with Crabp1 knockout experiences more severe heart failure and remodeling. RA is used to pretreat induced mice. It is found that the ejection fraction recovered in the wild-type mice, but not in the CKO mice. Cell culture experiments confirms that RA inhibits the phosphorylation of CaMKII, in which crabp1 participate. The molecular data reveals that RA selectively enhances the interaction between Crabp1 and the regulatory domains of CaMKII. These data suggests that RA plays a protective role in β-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac remodeling, mainly due to its inhibition of CaMKII activity [125].

Researches show that Chicago Sky Blue 6B (CSB) has many biological targets, including VGLUT [126], and can reduce the conditional reward effect caused by methamphetamine (METH) and relieve pain [127,128]. The proliferation of p8 cardiomyocytes is successfully induced by CSB, a VGLUT inhibitor. After 5 days of MI, CSB prevents the increase of phosphorylated CaMKII under the premise of keeping the total level of CaMKII. CSB treatment reduces the scar size, maintains the cardiac ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS), and inhibition of CaMKII weakens the protective effect of CSB. The experimental data shows that the CSB in adult mice promotes the cardiac repair and improves the contractility of cardiomyocytes by inhibiting the CaMKII signal pathway [129]. Phenolic compounds have many medicinal and health care functions [130], and they can be anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidation, affect the metabolism of sugar and lipid, and prevent cardiovascular disease and its complications [131-134]. Three month old Wistar rats are selected and treated with phenol compounds (PC) for 14 months. Compared with the untreated control group, the PC group shows a decrease in ejection fraction, left ventricular hypertrophy, and AR ventricular diameter and posterior wall thickness. The analysis of cardiac tissue protein shows that PC could weaken many hypertrophic pathways, including calcineurin/activated T-cell nuclear factor (NFATc3) and CaMKII [135].

Chinese herbal medicine has a unique curative effect in the treatment of chronic and complex diseases. Ginseng can improve the general health condition and has been widely used in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases [136], which combined with other drugs can achieve better therapeutic effect [137]. The results show that ginseng combined with Fuzi Beimu can maintain the lung function improvement caused by FBC (Fuzi and Beimucompatibility), inhibit the cardiotoxicity, inhibit the activation of βAR-Gs-PKA/CaMKII and Epac1/ERK1/2 axis through the crosstalk of PKA and Epac signal pathways, and protect the cardiac function and inhibit the myocardial apoptosis [138]. In addition, the YiQiFuMai powder injection (YQFM) is a traditional Chinese medicine prescription which has been used in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. The research shows that YQFM can improve the mitochondrial function of heart failure (HF) by inhibiting the production of ROS and the CaMKII signal pathway, and provide another way for the clinical treatment of HF [139].

Conclusions

Under normal conditions, CaMKII can stimulate energy production, glucose uptake, sarcolemma ion flux, SR Ca2+ release/reuptake and myocyte contraction/relaxation, so as to promote cardiac adaptability. However, in the pathological state, various therapeutic factors will cause the continuous and chronic activation of CaMKII, which will cause mitochondrial dysfunction, remodeling of ion channels, intracellular Ca2+ circulation disorder, inflammation and myocardial contraction dysfunction, and promote the progress of myocardial necrosis, hypertrophy, arrhythmia and other diseases. Therefore, inhibition of the activation of CaMKII is likely to have a good effect on inhibiting the progress of heart disease. This paper has introduced several new drugs targeting at CaMKII, and in the future more studies should be made to develop specific drugs targeting at the heart subtype of CaMKII, and focus on the clinical effect and possible side effects of the combination of new drugs for CaMKII and traditional drugs for heart disease.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Calcium sparks. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1491–1545. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ringer S. A further contribution regarding the influence of the different constituents of the blood on the contraction of the heart. J Physiol. 1883;4:29–42.3. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1883.sp000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winslow RL, Walker MA, Greenstein JL. Modeling calcium regulation of contraction, energetics, signaling, and transcription in the cardiac myocyte. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2016;8:37–67. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim M, Gorelik J, Yacoub MH, Terracciano CM. The structure and function of cardiac t-tubules in health and disease. Proc Biol Sci. 2011;278:2714–2723. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisner DA, Caldwell JL, Kistamás K, Trafford AW. Calcium and excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Circ Res. 2017;121:181–195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heijman J, Voigt N, Wehrens XH, Dobrev D. Calcium dysregulation in atrial fibrillation: the role of CaMKII. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:30. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bers DM, Stiffel VM. Ratio of ryanodine to dihydropyridine receptors in cardiac and skeletal muscle and implications for E-C coupling. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:C1587–1593. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.6.C1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves JP, Hale CC. The stoichiometry of the cardiac sodium-calcium exchange system. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:7733–7739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higazi DR, Fearnley CJ, Drawnel FM, Talasila A, Corps EM, Ritter O, McDonald F, Mikoshiba K, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Endothelin-1-stimulated InsP3-induced Ca2+ release is a nexus for hypertrophic signaling in cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell. 2009;33:472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betzenhauser MJ, Fike JL, Wagner LE 2nd, Yule DI. Protein kinase A increases type-2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor activity by phosphorylation of serine 937. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25116–25125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yue Z, Xie J, Yu AS, Stock J, Du J, Yue L. Role of TRP channels in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H157–182. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00457.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eder P, Molkentin JD. TRPC channels as effectors of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2011;108:265–272. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:23–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao LH, Stratton MM, Lee IH, Rosenberg OS, Levitz J, Mandell DJ, Kortemme T, Groves JT, Schulman H, Kuriyan J. A mechanism for tunable autoinhibition in the structure of a human Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II holoenzyme. Cell. 2011;146:732–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoelz A, Nairn AC, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of a tetradecameric assembly of the association domain of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1241–1251. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudmon A, Schulman H. Structure-function of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J. 2002;364:593–611. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song Q, Saucerman JJ, Bossuyt J, Bers DM. Differential integration of Ca2+-calmodulin signal in intact ventricular myocytes at low and high affinity Ca2+-calmodulin targets. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31531–31540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804902200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer T, Hanson PI, Stryer L, Schulman H. Calmodulin trapping by calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1992;256:1199–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai Y, Nairn AC, Gorelick F, Greengard P. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: identification of autophosphorylation sites responsible for generation of Ca2+/calmodulin-independence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:5710–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich RC, Schulman H. Substrate-directed function of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28424–28429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudmon A, Schulman H. Neuronal CA2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: the role of structure and autoregulation in cellular function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:473–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putkey JA, Waxham MN. A peptide model for calmodulin trapping by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29619–29623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton BL, Miller SG, Kennedy MB. Activation of type II calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase by Ca2+/calmodulin is inhibited by autophosphorylation of threonine within the calmodulin-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11204–11212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodge JJ, Mullasseril P, Griffith LC. Activity-dependent gating of CaMKII autonomous activity by Drosophila CASK. Neuron. 2006;51:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erickson JR, Nichols CB, Uchinoumi H, Stein ML, Bossuyt J, Bers DM. S-Nitrosylation induces both autonomous activation and inhibition of calcium/calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II δ. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:25646–25656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.650234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutierrez DA, Fernandez-Tenorio M, Ogrodnik J, Niggli E. NO-dependent CaMKII activation during β-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac muscle. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100:392–401. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song YH. A memory molecule, Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and redox stress; key factors for arrhythmias in a diseased heart. Korean Circ J. 2013;43:145–151. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2013.43.3.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erickson JR, Pereira L, Wang L, Han G, Ferguson A, Dao K, Copeland RJ, Despa F, Hart GW, Ripplinger CM, Bers DM. Diabetic hyperglycaemia activates CaMKII and arrhythmias by O-linked glycosylation. Nature. 2013;502:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature12537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johanson RA, Sarau HM, Foley JJ, Slemmon JR. Calmodulin-binding peptide PEP-19 modulates activation of calmodulin kinase II In situ. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2860–2866. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02860.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strack S, Barban MA, Wadzinski BE, Colbran RJ. Differential inactivation of postsynaptic density-associated and soluble Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II by protein phosphatases 1 and 2A. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2119–2128. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swaminathan PD, Purohit A, Hund TJ, Anderson ME. Calmodulin-dependent protein Kinase II: linking heart failure and arrhythmias. Circ Res. 2012;110:1661–1677. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronkainen JJ, Hänninen SL, Korhonen T, Koivumäki JT, Skoumal R, Rautio S, Ronkainen VP, Tavi P. Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II represses cardiac transcription of the L-type calcium channel alpha(1C)-subunit gene (Cacna1c) by DREAM translocation. J Physiol. 2011;589:2669–2686. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maxwell JT, Natesan S, Mignery GA. Modulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 2 channel activity by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)-mediated phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:39419–39428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molkentin JD, Lu JR, Antos CL, Markham B, Richardson J, Robbins J, Grant SR, Olson EN. A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 1998;93:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattiazzi A, Kranias EG. The role of CaMKII regulation of phospholamban activity in heart disease. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuchi Z, Lau K, Van Petegem F. Disease mutations in the ryanodine receptor central region: crystal structures of a phosphorylation hot spot domain. Structure. 2012;20:1201–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaertner TR, Kolodziej SJ, Wang D, Kobayashi R, Koomen JM, Stoops JK, Waxham MN. Comparative analyses of the three-dimensional structures and enzymatic properties of alpha, beta, gamma and delta isoforms of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12484–12494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishra S, Gray CB, Miyamoto S, Bers DM, Brown JH. Location matters: clarifying the concept of nuclear and cytosolic CaMKII subtypes. Circ Res. 2011;109:1354–1362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li K, Lin Y, Li C. MiR-338-5p ameliorates pathological cardiac hypertrophy by targeting CAMKIIδ. Arch Pharm Res. 2019;42:1071–1080. doi: 10.1007/s12272-019-01199-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang T, Kohlhaas M, Backs J, Mishra S, Phillips W, Dybkova N, Chang S, Ling H, Bers DM, Maier LS, Olson EN, Brown JH. CaMKIIdelta isoforms differentially affect calcium handling but similarly regulate HDAC/MEF2 transcriptional responses. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35078–35087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willeford A, Suetomi T, Nickle A, Hoffman HM, Miyamoto S, Heller Brown J. CaMKIIδ-mediated inflammatory gene expression and inflammasome activation in cardiomyocytes initiate inflammation and induce fibrosis. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e97054. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.97054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suetomi T, Willeford A, Brand CS, Cho Y, Ross RS, Miyamoto S, Brown JH. Inflammation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation initiated in response to pressure overload by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II δ signaling in cardiomyocytes are essential for adverse cardiac remodeling. Circulation. 2018;138:2530–2544. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li C, Cai X, Sun H, Bai T, Zheng X, Zhou XW, Chen X, Gill DL, Li J, Tang XD. The δA isoform of calmodulin kinase II mediates pathological cardiac hypertrophy by interfering with the HDAC4-MEF2 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;409:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao RP, Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Suzuki T, Lakatta EG. Dual regulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II activity by membrane voltage and by calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9659–9663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srinivasan M, Edman CF, Schulman H. Alternative splicing introduces a nuclear localization signal that targets multifunctional CaM kinase to the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:839–852. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu X, Yang D, Ding JH, Wang W, Chu PH, Dalton ND, Wang HY, Bermingham JR Jr, Ye Z, Liu F, Rosenfeld MG, Manley JL, Ross J Jr, Chen J, Xiao RP, Cheng H, Fu XD. ASF/SF2-regulated CaMKIIdelta alternative splicing temporally reprograms excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Cell. 2005;120:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Little GH, Saw A, Bai Y, Dow J, Marjoram P, Simkhovich B, Leeka J, Kedes L, Kloner RA, Poizat C. Critical role of nuclear calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIdeltaB in cardiomyocyte survival in cardiomyopathy. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24857–24868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamdani N, Krysiak J, Kreusser MM, Neef S, Dos Remedios CG, Maier LS, Krüger M, Backs J, Linke WA. Crucial role for Ca2(+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II in regulating diastolic stress of normal and failing hearts via titin phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2013;112:664–674. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu WZ, Wang SQ, Chakir K, Yang D, Zhang T, Brown JH, Devic E, Kobilka BK, Cheng H, Xiao RP. Linkage of beta1-adrenergic stimulation to apoptotic heart cell death through protein kinase A-independent activation of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:617–625. doi: 10.1172/JCI16326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoo B, Lemaire A, Mangmool S, Wolf MJ, Curcio A, Mao L, Rockman HA. Beta1-adrenergic receptors stimulate cardiac contractility and CaMKII activation in vivo and enhance cardiac dysfunction following myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1377–1386. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00504.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimm M, Brown JH. Beta-adrenergic receptor signaling in the heart: role of CaMKII. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X, Szeto C, Gao E, Tang M, Jin J, Fu Q, Makarewich C, Ai X, Li Y, Tang A, Wang J, Gao H, Wang F, Ge XJ, Kunapuli SP, Zhou L, Zeng C, Xiang KY, Chen X. Cardiotoxic and cardioprotective features of chronic β-adrenergic signaling. Circ Res. 2013;112:498–509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O’Donnell SE, Aykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham AJ, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 2008;133:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Timmins JM, Ozcan L, Seimon TA, Li G, Malagelada C, Backs J, Backs T, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Anderson ME, Tabas I. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II links ER stress with Fas and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2925–2941. doi: 10.1172/JCI38857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fazal L, Laudette M, Paula-Gomes S, Pons S, Conte C, Tortosa F, Sicard P, Sainte-Marie Y, Bisserier M, Lairez O, Lucas A, Roy J, Ghaleh B, Fauconnier J, Mialet-Perez J, Lezoualc’h F. multifunctional mitochondrial epac1 controls myocardial cell death. Circ Res. 2017;120:645–657. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Di Carlo MN, Said M, Ling H, Valverde CA, De Giusti VC, Sommese L, Palomeque J, Aiello EA, Skapura DG, Rinaldi G, Respress JL, Brown JH, Wehrens XH, Salas MA, Mattiazzi A. CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of cardiac ryanodine receptors regulates cell death in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;74:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anderson ME, Brown JH, Bers DM. CaMKII in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woods C, Shang C, Taghavi F, Downey P, Zalewski A, Rubio GR, Liu J, Homburger JR, Grunwald Z, Qi W, Bollensdorff C, Thanaporn P, Ali A, Riemer K, Kohl P, Mochly-Rosen D, Gerstenfeld E, Large S, Ali Z, Ashley E. In vivo post-cardiac arrest myocardial dysfunction is supported by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii-mediated calcium long-term potentiation and mitigated by Alda-1, an agonist of aldehyde dehydrogenase type 2. Circulation. 2016;134:961–977. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu W, Tsang S, Browe DM, Woo AY, Huang Y, Xu C, Liu JF, Lv F, Zhang Y, Xiao RP. Interaction of β1-adrenoceptor with RAGE mediates cardiomyopathy via CaMKII signaling. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e84969. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.84969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma Y, Gong Z, Nan K, Qi S, Chen Y, Ding C, Wang D, Ru L. Apolipoprotein-J blocks increased cell injury elicited by ox-LDL via inhibiting ROS-CaMKII pathway. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18:117. doi: 10.1186/s12944-019-1066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Doran AC, Ozcan L, Cai B, Zheng Z, Fredman G, Rymond CC, Dorweiler B, Sluimer JC, Hsieh J, Kuriakose G, Tall AR, Tabas I. CAMKIIγ suppresses an efferocytosis pathway in macrophages and promotes atherosclerotic plaque necrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4075–4089. doi: 10.1172/JCI94735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X, Wang X. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell. 2012;148:213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang Z, Li C, Wang Y, Yang J, Yin Y, Liu M, Shi Z, Mu N, Yu L, Ma H. Melatonin attenuates chronic pain related myocardial ischemic susceptibility through inhibiting RIP3-MLKL/CaMKII dependent necroptosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;125:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li J, Marionneau C, Koval O, Zingman L, Mohler PJ, Nerbonne JM, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition enhances ischemic preconditioning by augmenting ATP-sensitive K+ current. Channels (Austin) 2007;1:387–394. doi: 10.4161/chan.5449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sierra A, Zhu Z, Sapay N, Sharotri V, Kline CF, Luczak ED, Subbotina E, Sivaprasadarao A, Snyder PM, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME, Vivaudou M, Zingman LV, Hodgson-Zingman DM. Regulation of cardiac ATP-sensitive potassium channel surface expression by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1568–1581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.429548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zingman LV, Alekseev AE, Hodgson-Zingman DM, Terzic A. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: metabolic sensing and cardioprotection. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;103:1888–1893. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00747.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suzuki M, Sasaki N, Miki T, Sakamoto N, Ohmoto-Sekine Y, Tamagawa M, Seino S, Marbán E, Nakaya H. Role of sarcolemmal K(ATP) channels in cardioprotection against ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:509–516. doi: 10.1172/JCI14270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gao Z, Sierra A, Zhu Z, Koganti SR, Subbotina E, Maheshwari A, Anderson ME, Zingman LV, Hodgson-Zingman DM. Loss of ATP-sensitive potassium channel surface expression in heart failure underlies dysregulation of action potential duration and myocardial vulnerability to injury. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ottesen AH, Carlson CR, Louch WE, Dahl MB, Sandbu RA, Johansen RF, Jarstadmarken H, Bjørås M, Høiseth AD, Brynildsen J, Sjaastad I, Stridsberg M, Omland T, Christensen G, Røsjø H. Glycosylated chromogranin A in heart failure: implications for processing and cardiomyocyte calcium homeostasis. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10:e003675. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fujisawa H. Regulation of the activities of multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. J Biochem. 2001;129:193–199. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crabtree GR, Olson EN. NFAT signaling: choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S67–79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilkins BJ, Dai YS, Bueno OF, Parsons SA, Xu J, Plank DM, Jones F, Kimball TR, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin/NFAT coupling participates in pathological, but not physiological, cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2004;94:110–118. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109415.17511.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zeng C, Zhong P, Zhao Y, Kanchana K, Zhang Y, Khan ZA, Chakrabarti S, Wu L, Wang J, Liang G. Curcumin protects hearts from FFA-induced injury by activating Nrf2 and inactivating NF-κB both in vitro and in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;79:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nishio S, Teshima Y, Takahashi N, Thuc LC, Saito S, Fukui A, Kume O, Fukunaga N, Hara M, Nakagawa M, Saikawa T. Activation of CaMKII as a key regulator of reactive oxygen species production in diabetic rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1103–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Duran J, Lagos D, Pavez M, Troncoso MF, Ramos S, Barrientos G, Ibarra C, Lavandero S, Estrada M. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii and androgen signaling pathways modulate MEF2 activity in testosterone-induced cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:604. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kunisada K, Negoro S, Tone E, Funamoto M, Osugi T, Yamada S, Okabe M, Kishimoto T, Yamauchi-Takihara K. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in the heart transduces not only a hypertrophic signal but a protective signal against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:315–319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hulsurkar M, Quick AP, Wehrens XH. STAT3: a link between CaMKII-βIV-spectrin and maladaptive remodeling? J Clin Invest. 2018;128:5219–5221. doi: 10.1172/JCI124778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao L, Cheng G, Jin R, Afzal MR, Samanta A, Xuan YT, Girgis M, Elias HK, Zhu Y, Davani A, Yang Y, Chen X, Ye S, Wang OL, Chen L, Hauptman J, Vincent RJ, Dawn B. Deletion of interleukin-6 attenuates pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction. Circ Res. 2016;118:1918–1929. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cai K, Chen H. MiR-625-5p Inhibits cardiac hypertrophy through targeting STAT3 and CaMKII. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev. 2019;30:182–191. doi: 10.1089/humc.2019.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bush EW, Hood DB, Papst PJ, Chapo JA, Minobe W, Bristow MR, Olson EN, McKinsey TA. Canonical transient receptor potential channels promote cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through activation of calcineurin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33487–33496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morales S, Diez A, Puyet A, Camello PJ, Camello-Almaraz C, Bautista JM, Pozo MJ. Calcium controls smooth muscle TRPC gene transcription via the CaMK/calcineurin-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C553–563. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00096.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang Z, Xu Y, Wang M, Ye J, Liu J, Jiang H, Ye D, Wan J. TRPA1 inhibition ameliorates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in mice. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen CH, Lin JW, Huang CY, Yeh YL, Shen CY, Badrealam KF, Ho TJ, Padma VV, Kuo WW, Huang CY. The combined inhibition of the CaMKIIδ and calcineurin signaling cascade attenuates IGF-IIR-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:3539–3547. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rodríguez-Moyano M, Díaz I, Dionisio N, Zhang X, Avila-Medina J, Calderón-Sánchez E, Trebak M, Rosado JA, Ordóñez A, Smani T. Urotensin-II promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through store-operated calcium entry and EGFR transactivation. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100:297–306. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shi H, Han Q, Xu J, Liu W, Chu T, Zhao L. Urotensin II induction of neonatal cardiomyocyte hypertrophy involves the CaMKII/PLN/SERCA 2a signaling pathway. Gene. 2016;583:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Helms AS, Alvarado FJ, Yob J, Tang VT, Pagani F, Russell MW, Valdivia HH, Day SM. Genotype-dependent and -independent calcium signaling dysregulation in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2016;134:1738–1748. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yao L, Fan P, Jiang Z, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Wu Y, Kornyeyev D, Hirakawa R, Budas GR, Rajamani S, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Nav1.5-dependent persistent Na+ influx activates CaMKII in rat ventricular myocytes and N1325S mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C577–586. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00125.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Backs J, Song K, Bezprozvannaya S, Chang S, Olson EN. CaM kinase II selectively signals to histone deacetylase 4 during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1853–1864. doi: 10.1172/JCI27438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chang YW, Chang YT, Wang Q, Lin JJ, Chen YJ, Chen CC. Quantitative phosphoproteomic study of pressure-overloaded mouse heart reveals dynamin-related protein 1 as a modulator of cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:3094–3107. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.027649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hasan P, Saotome M, Ikoma T, Iguchi K, Kawasaki H, Iwashita T, Hayashi H, Maekawa Y. Mitochondrial fission protein, dynamin-related protein 1, contributes to the promotion of hypertensive cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in Dahl-salt sensitive rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;121:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Belardinelli L, Giles WR, Rajamani S, Karagueuzian HS, Shryock JC. Cardiac late Na+ current: proarrhythmic effects, roles in long QT syndromes, and pathological relationship to CaMKII and oxidative stress. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sag CM, Mallwitz A, Wagner S, Hartmann N, Schotola H, Fischer TH, Ungeheuer N, Herting J, Shah AM, Maier LS, Sossalla S, Unsöld B. Enhanced late INa induces proarrhythmogenic SR Ca leak in a CaMKII-dependent manner. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;76:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eiringhaus J, Herting J, Schatter F, Nikolaev VO, Sprenger J, Wang Y, Köhn M, Zabel M, El-Armouche A, Hasenfuss G, Sossalla S, Fischer TH. Protein kinase/phosphatase balance mediates the effects of increased late sodium current on ventricular calcium cycling. Basic Res Cardiol. 2019;114:13. doi: 10.1007/s00395-019-0720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Coppini R, Ferrantini C, Yao L, Fan P, Del Lungo M, Stillitano F, Sartiani L, Tosi B, Suffredini S, Tesi C, Yacoub M, Olivotto I, Belardinelli L, Poggesi C, Cerbai E, Mugelli A. Late sodium current inhibition reverses electromechanical dysfunction in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2013;127:575–584. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.134932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ferrantini C, Pioner JM, Mazzoni L, Gentile F, Tosi B, Rossi A, Belardinelli L, Tesi C, Palandri C, Matucci R, Cerbai E, Olivotto I, Poggesi C, Mugelli A, Coppini R. Late sodium current inhibitors to treat exercise-induced obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an in vitro study in human myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:2635–2652. doi: 10.1111/bph.14223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Coppini R, Ferrantini C, Mugelli A, Poggesi C, Cerbai E. Altered Ca2+ and Na+ homeostasis in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: implications for arrhythmogenesis. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1391. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ullrich ND, Fanchaouy M, Gusev K, Shirokova N, Niggli E. Hypersensitivity of excitation-contraction coupling in dystrophic cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1992–2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00602.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Niggli E. The cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum: filled with Ca2+ and surprises. Circ Res. 2007;100:5–6. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255896.06757.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sag CM, Köhler AC, Anderson ME, Backs J, Maier LS. CaMKII-dependent SR Ca leak contributes to doxorubicin-induced impaired Ca handling in isolated cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:749–759. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang Q, Quick AP, Cao S, Reynolds J, Chiang DY, Beavers D, Li N, Wang G, Rodney GG, Anderson ME, Wehrens XHT. Oxidized CaMKII (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II) is essential for ventricular arrhythmia in a mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11:e005682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Voskoboinik A, Prabhu S, Ling LH, Kalman JM, Kistler PM. Alcohol and atrial fibrillation: a sobering review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2567–2576. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang X, Lu Y, Xie B, Cederbaum AI. Chronic ethanol feeding potentiates Fas Jo2-induced hepatotoxicity: role of CYP2E1 and TNF-alpha and activation of JNK and P38 MAP kinase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yan J, Thomson JK, Zhao W, Gao X, Huang F, Chen B, Liang Q, Song LS, Fill M, Ai X. Role of stress kinase JNK in binge alcohol-evoked atrial arrhythmia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1459–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Venetucci L, Denegri M, Napolitano C, Priori SG. Inherited calcium channelopathies in the pathophysiology of arrhythmias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:561–575. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.van Oort RJ, McCauley MD, Dixit SS, Pereira L, Yang Y, Respress JL, Wang Q, De Almeida AC, Skapura DG, Anderson ME, Bers DM, Wehrens XH. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II promotes life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in mice with heart failure. Circulation. 2010;122:2669–2679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Park SJ, Zhang D, Qi Y, Li Y, Lee KY, Bezzerides VJ, Yang P, Xia S, Kim SL, Liu X, Lu F, Pasqualini FS, Campbell PH, Geva J, Roberts AE, Kleber AG, Abrams DJ, Pu WT, Parker KK. Insights into the pathogenesis of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia from engineered human heart tissue. Circulation. 2019;140:390–404. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.039711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Razzaque MS. The FGF23-Klotho axis: endocrine regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:611–619. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Huang SY, Chen YC, Kao YH, Hsieh MH, Lin YK, Chung CC, Lee TI, Tsai WC, Chen SA, Chen YJ. Fibroblast growth factor 23 dysregulates late sodium current and calcium homeostasis with enhanced arrhythmogenesis in pulmonary vein cardiomyocytes. Oncotarget. 2016;7:69231–69242. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Kornyeyev D, El-Bizri N, Budas G, Fan P, Jiang Z, Yang J, Anderson ME, Shryock JC, Chang CP, Belardinelli L, Yao L. Intracellular Na+ overload causes oxidation of CaMKII and leads to Ca2+ mishandling in isolated ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;76:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jin SW, Choi CY, Hwang YP, Kim HG, Kim SJ, Chung YC, Lee KJ, Jeong TC, Jeong HG. Betulinic acid increases eNOS phosphorylation and NO synthesis via the calcium-signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:785–791. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Christ T, Rozmaritsa N, Engel A, Berk E, Knaut M, Metzner K, Canteras M, Ravens U, Kaumann A. Arrhythmias, elicited by catecholamines and serotonin, vanish in human chronic atrial fibrillation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:11193–11198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324132111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Westra J, Brouwer E, van Roosmalen IA, Doornbos-van der Meer B, van Leeuwen MA, Posthumus MD, Kallenberg CG. Expression and regulation of HIF-1alpha in macrophages under inflammatory conditions; significant reduction of VEGF by CaMKII inhibitor. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Westra J, Brouwer E, Bouwman E, Doornbos-van der Meer B, Posthumus MD, van Leeuwen MA, Limburg PC, Ueda Y, Kallenberg CG. Role for CaMKII inhibition in rheumatoid arthritis: effects on HIF-1-induced VEGF production by rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:706–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Li J, Zhao SZ, Wang PP, Yu SP, Zheng Z, Xu X. Calcium mediates high glucose-induced HIF-1α and VEGF expression in cultured rat retinal Müller cells through CaMKII-CREB pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:1030–1036. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tagashira S, Fukushima A. Novel CaMKII inhibitor, SMP-114, with excellent efficacy in collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:288. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wagner S, Dybkova N, Rasenack EC, Jacobshagen C, Fabritz L, Kirchhof P, Maier SK, Zhang T, Hasenfuss G, Brown JH, Bers DM, Maier LS. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3127–3138. doi: 10.1172/JCI26620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Neef S, Mann C, Zwenger A, Dybkova N, Maier LS. Reduction of SR Ca2+ leak and arrhythmogenic cellular correlates by SMP-114, a novel CaMKII inhibitor with oral bioavailability. Basic Res Cardiol. 2017;112:45. doi: 10.1007/s00395-017-0637-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pellicena P, Schulman H. CaMKII inhibitors: from research tools to therapeutic agents. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:21. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Neef S, Steffens A, Pellicena P, Mustroph J, Lebek S, Ort KR, Schulman H, Maier LS. Improvement of cardiomyocyte function by a novel pyrimidine-based CaMKII-inhibitor. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;115:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Choudhary R, Baker KM, Pan J. All-trans retinoic acid prevents angiotensin II- and mechanical stretch-induced reactive oxygen species generation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:172–181. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Paiva SA, Matsubara LS, Matsubara BB, Minicucci MF, Azevedo PS, Campana AO, Zornoff LA. Retinoic acid supplementation attenuates ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. J Nutr. 2005;135:2326–2328. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Park SW, Persaud SD, Ogokeh S, Meyers TA, Townsend D, Wei LN. CRABP1 protects the heart from isoproterenol-induced acute and chronic remodeling. J Endocrinol. 2018;236:151–165. doi: 10.1530/JOE-17-0613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Park SW, Nhieu J, Lin YW, Wei LN. All-trans retinoic acid attenuates isoproterenol-induced cardiac dysfunction through Crabp1 to dampen CaMKII activation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;858:172485. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.He Z, Yan L, Yong Z, Dong Z, Dong H, Gong Z. Chicago sky blue 6B, a vesicular glutamate transporters inhibitor, attenuates methamphetamine-induced hyperactivity and behavioral sensitization in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2013;239:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fujio M, Nakagawa T, Sekiya Y, Ozawa T, Suzuki Y, Minami M, Satoh M, Kaneko S. Gene transfer of GLT-1, a glutamate transporter, into the nucleus accumbens shell attenuates methamphetamine- and morphine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2744–2754. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yu G, Yi S, Wang M, Yan H, Yan L, Su R, Gong Z. The antinociceptive effects of intracerebroventricular administration of Chicago sky blue 6B, a vesicular glutamate transporter inhibitor. Behav Pharmacol. 2013;24:653–658. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Yifa O, Weisinger K, Bassat E, Li H, Kain D, Barr H, Kozer N, Genzelinakh A, Rajchman D, Eigler T, Umansky KB, Lendengolts D, Brener O, Bursac N, Tzahor E. The small molecule Chicago Sky Blue promotes heart repair following myocardial infarction in mice. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e128025. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.128025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Varzakas T, Zakynthinos G, Verpoort F. Plant food residues as a source of nutraceuticals and functional foods. Foods. 2016;5:88. doi: 10.3390/foods5040088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Conforti F, Sosa S, Marrelli M, Menichini F, Statti GA, Uzunov D, Tubaro A, Menichini F, Loggia RD. In vivo anti-inflammatory and in vitro antioxidant activities of Mediterranean dietary plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Velioglu YS, Mazza G, Gao L, Oomah BD. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in selected fruits, vegetables, and grain products. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:4113–4117. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hanhineva K, Törrönen R, Bondia-Pons I, Pekkinen J, Kolehmainen M, Mykkänen H, Poutanen K. Impact of dietary polyphenols on carbohydrate metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:1365–1402. doi: 10.3390/ijms11041365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Renaud S, de Lorgeril M. Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1992;339:1523–1526. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91277-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Chacar S, Hajal J, Saliba Y, Bois P, Louka N, Maroun RG, Faivre JF, Fares N. Long-term intake of phenolic compounds attenuates age-related cardiac remodeling. Aging Cell. 2019;18:e12894. doi: 10.1111/acel.12894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Luo P, Dong G, Liu L, Zhou H. The long-term consumption of ginseng extract reduces the susceptibility of intermediate-aged hearts to acute ischemia reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ma X, Bi S, Wang Y, Chi X, Hu S. Combined adjuvant effect of ginseng stem-leaf saponins and selenium on immune responses to a live bivalent vaccine of Newcastle disease virus and infectious bronchitis virus in chickens. Poult Sci. 2019;98:3548–3556. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Huang Y, Li L, Li X, Fan S, Zhuang P, Zhang Y. Ginseng compatibility environment attenuates toxicity and keeps efficacy in cor pulmonale treated by Fuzi Beimu incompatibility through the coordinated crosstalk of PKA and Epac signaling pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:634. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zhang Y, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Fan X, Yang W, Yu B, Kou J, Li F. YiQiFuMai powder injection attenuates coronary artery ligation-induced heart failure through improving mitochondrial function via regulating ros generation and camkii signaling pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:381. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]