Abstract

Background

General practitioners (GPs) should regularly review patients’ medications and, if necessary, deprescribe, as inappropriate polypharmacy may harm patients’ health. However, deprescribing can be challenging for physicians. This study investigates GPs’ deprescribing decisions in 31 countries.

Methods

In this case vignette study, GPs were invited to participate in an online survey containing three clinical cases of oldest-old multimorbid patients with potentially inappropriate polypharmacy. Patients differed in terms of dependency in activities of daily living (ADL) and were presented with and without history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). For each case, we asked GPs if they would deprescribe in their usual practice. We calculated proportions of GPs who reported they would deprescribe and performed a multilevel logistic regression to examine the association between history of CVD and level of dependency on GPs’ deprescribing decisions.

Results

Of 3,175 invited GPs, 54% responded (N = 1,706). The mean age was 50 years and 60% of respondents were female. Despite differences across GP characteristics, such as age (with older GPs being more likely to take deprescribing decisions), and across countries, overall more than 80% of GPs reported they would deprescribe the dosage of at least one medication in oldest-old patients (> 80 years) with polypharmacy irrespective of history of CVD. The odds of deprescribing was higher in patients with a higher level of dependency in ADL (OR =1.5, 95%CI 1.25 to 1.80) and absence of CVD (OR =3.04, 95%CI 2.58 to 3.57).

Interpretation

The majority of GPs in this study were willing to deprescribe one or more medications in oldest-old multimorbid patients with polypharmacy. Willingness was higher in patients with increased dependency in ADL and lower in patients with CVD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-020-01953-6.

Keywords: Deprescribing, Polypharmacy, Multimorbidity, Primary health care, Old age

Background

Polypharmacy, commonly defined as the concurrent use of 5 or more medications, is a growing concern in a context of common overtreatment. More than 40% of older adults aged 65 years and over and an even higher percentage of older nursing home residents have polypharmacy [1, 2]. Polypharmacy can be problematic as it is associated with a higher risk of being prescribed potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) [3]. One third of adults aged 65 years and over are taking at least one PIM [4]. Polypharmacy and PIMs are linked to an increased risk of adverse drug events [5, 6], drug-drug and drug-disease interactions [7, 8], functional decline [9–11], decline in cognitive function [10, 12], increased risk for falls [13, 14], and increase in direct medical healthcare costs [15].

Older multimorbid adults with cardiovascular diseases (CVD) have been shown to be disproportionately affected by medication-related issues [16]. Due to these potential negative consequences optimizing polypharmacy in older adults including those with CVD is highly relevant.

With increasing age the main treatment goals often shift from the prevention of mortality and morbidity to the maintaining of functional independence and quality of life, especially in less robust older adults with limited levels of independence [17]. In addition, the benefit-risk profile of older dependent and less robust adults is altered as they are at greater risk of medication induced harm and may not have sufficient remaining life span to benefit from preventive medications [18, 19]. Therefore, older adults with limited functional independence might particularly benefit from medication optimization through deprescribing. However, little is currently known about general practitioners’ (GPs) attitudes towards deprescribing in patients with and without history of cardiovascular disease or in those with limited functional independence.

In recent years, deprescribing has become a popular “new word to guide medication review” [20]. It is commonly defined as ‘the process of withdrawal or [reduction] of an inappropriate medication, supervised by a healthcare professional with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes’ [21]. Deprescribing has several benefits, such as achieving better health outcomes through resolving adverse drug reactions, better medication adherence, and direct medical healthcare costs reductions [22]. However, deprescribing may also have negative consequences, such as withdrawal reactions and the worsening or return of medical conditions. These potential harms can be minimized with appropriate planning, monitoring, and re-initiation of medications if needed [22]. As evidenced by the high prevalence of inappropriate medication use in older adults, deprescribing is not routinely conducted in practice. Despite its potential benefits, deprescribing is difficult to implement [23]. In practice, both physicians and patients report barriers to deprescribing, such as uncertainty on how to deprescribe due to a lack of evidence-based guidelines. Patients have reported believing that their medications are still necessary or beneficial [24–27]. An understanding of GPs’ deprescribing decisions and the potential barriers they face is needed to inform GP education and develop interventions to optimise appropriate medication use in older adults.

In a case vignette study with 157 GPs in Switzerland, we found a high rate of hypothetical deprescribing of certain medications, which was influenced by patients' history of CVD [28]. However, we were not able to establish the generalisability of these results and the influence of other patient characteristics on GPs deprescribing decisions. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine deprescribing decisions of GPs in oldest-old patients (80 years and over) with polypharmacy across different countries and to examine whether increasing levels of dependency in activities of daily living (ADL) and history of CVD influenced these decisions.

Methods

Setting and study design

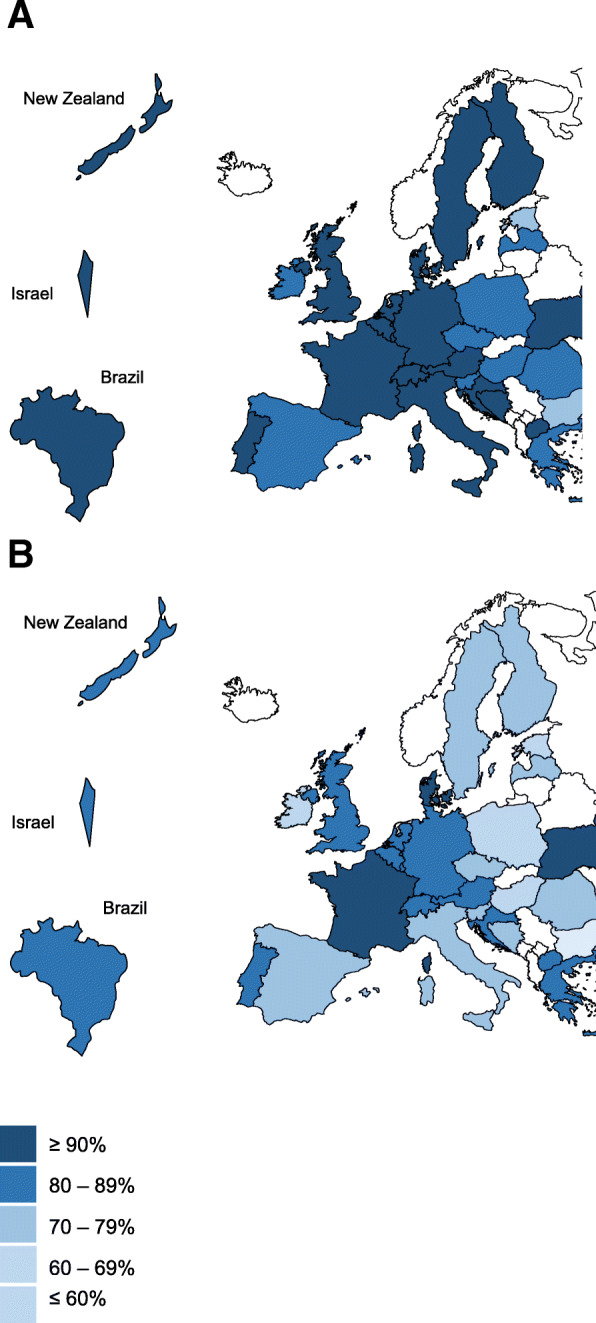

This is a cross-sectional case vignette study conducted with GPs from 31 countries (see Fig. 1). It is part of the LESS (barriers and enabLers to willingnESs to depreScribing in older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy and their General Practitioners) study.

Fig. 1.

Per country average of the percentage of case vignettes in which GPs (N = 1,706) reported they would deprescribe at least one (map A) vs. at least two (map B) medications. List of participating countries (alphabetical order): Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, United Kingdom, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Macedonia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine. Maps designed by and adapted from PresentationGO.com / © Copyright PresentationGO.com

Participants

Our total sample consisted of 3,175 GPs from 31 countries who were invited to participate by email through national coordinators. Participants had previously provided consent to be contacted with opportunities to participate in future research [29, 30]. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were practicing GPs.

Questionnaire

We used the same questionnaire as described in Mantelli et al. (2018), but we included additional case vignettes [28]. We used the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) guidelines for reporting results of internet e-surveys [31, 32]. The questionnaire had 3 parts: 1) GP characteristics, 2) 3 case vignettes of oldest-old patients with higher/heightened dependency in activities of daily living (ADL) including increasing cognitive impairment, each presented with and without history of CVD, and 3) Likert-scale questions concerning factors influencing GPs’ deprescribing decisions. For the complete questionnaire, refer to Additional file 1: Appendix 1. Where necessary, national coordinators translated and back-translated the survey from English into 22 languages. In Finland and Israel, the survey was distributed in English. In all other countries the survey was distributed in one or several national languages (see Additional file 1: Appendix 2 for more information on survey languages). The online survey was distributed and administered with SurveyMonkey (Palo Alto, CA, USA).

To sample the participating GPs, first, we engaged with national coordinators through the European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN). Second, national coordinators identified relevant networks through which the survey could be distributed. Available networks varied depending on the country. Most national coordinators did a convenience sampling in which they distributed the survey by email to GPs in their personal networks, who had previously consented to be invited to participate in research. Participation was voluntary. In some countries, the survey was sent to lists of GPs available at primary care research institutes or professional societies, which explains the bigger sample size in these countries. Reminders were used when necessary (maximum two reminders where sent). The response rate for each country can be found in Additional file 1: Appendix 2. In Ukraine the survey was administered on paper during a national GP conference due to infrastructure-related reasons. We collected responses from February to December 2018.

Our research team, largely composed of GPs, designed the case vignettes with the aim of creating hypothetical patients aged ≥80 years representing patients typically seen in primary care. Repeated meetings to discuss the case vignettes were held. Collaborators in other countries were consulted by email, with changes made as necessary. Before starting the data collection, the online questionnaire was piloted among five Swiss GPs to test its content validity. Before starting the data collection in each participating country, each national coordinator checked and, if applicable, adapted the layout of the survey based on the local context.

The case vignettes were identical except for CVD status and levels of dependency in ADL. We provided descriptions of dependency related to low, medium and high impairment of ADL and cognitive function. All hypothetical patients were prescribed the same medications. For every case vignette, we asked GPs whether they would stop/reduce the dosage of at least one medication (i.e. deprescribe), and if so which one(s). GPs were instructed to respond as to how they would act in their usual practice.

In part 3 of the questionnaire, GPs were asked to rate the importance of sixteen factors that potentially influenced their deprescribing behaviour using 5-point Likert-scales ranging from “not important” to “very important”. The selection of these factors was based on work done by Luymes et al. [33] and Anderson et al. [34] and was completed with factors based on our team’s experience.

Completion of the survey took 10–15 minutes. The different parts of the questionnaire were presented on different pages and where necessary the content of one part was distributed over different pages to keep the number of items per page small. Respondents were able to navigate back and forth through the survey. The national coordinators sent a web link to GPs, which was required to access the survey. The selection of one response option was enforced. We did not use cookies nor did we collect IP addresses. We did not perform a timestamp analysis.

Statistical analyses

We described GP characteristics by calculating proportions, means, and confidence intervals (CI). We calculated crude odds ratios (OR) from univariate logistic regressions to determine if GP characteristics were associated with decisions to deprescribe. For each case vignette we described the proportions of GPs who would deprescribe. As a sensitivity analysis, we also performed this analysis in countries with a > 60% response rate. We calculated the average number of medications deprescribed per case vignette. We performed a multilevel logistic regression to examine the association between both history of CVD and level of dependency in ADL and GPs’ decisions to deprescribe at least one medication in any of the case vignettes by accounting for the clustering of GPs at country level. We adjusted the model for the following GP characteristics: age, sex, average number of consultations per day, frequency of seeing patients with polypharmacy. Subsequently, we performed a comparison of proportions to determine whether GPs’ deprescribing decisions concerning specific medications changed with increased patient dependency. Lastly, for the factors included in the Likert-scales we calculated the percentage of GPs who rated these factors as (very) important. We defined a two-sided p-value of < 0.05 as significant. All analyses were performed with STATA 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

GP characteristics

In the participating countries, the median response rate was 50% (range: 11–95%). Of the total of 3,175 invited GPs across countries, 1,706 responded (54%), and 1415 GPs completed the whole questionnaire. The number of participants differed by country (range: 20 in Czech Republic and Ireland; 247 in Hungary).

Table 1 presents characteristics of the participating GPs. 60% were female, mean age was 50 years, and the mean clinical experience as GP was 18 years. As shown in this table, being female reduced the odds of deprescribing in all case vignettes (compared to not deprescribing in one or more case vignettes), whereas the odds of deprescribing increased with increasing age of GPs, with GPs regularly treating patients aged 70 years or more with polypharmacy and with GPs regularly dealing with the topic of deprescribing.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of general practitioners (GPs) from all participating countries (N countries = 31, N GPs = 1,706)

| GPs’ deprescribing decisionsa (N = 1,428, only complete records) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP characteristics | Overall | Deprescribing in < 6 case vignettes (n = 370) |

Deprescribing in all 6 case vignettesb (n = 1,058) |

Crude odds ratio of deprescribing in all 6 case vignettesc (95% CI) |

P-valued |

| Sex | |||||

| female, n (%) | 1,021 (60) | 240 (65) | 593 (56) | 0.74 (0.57 to 0.96) | 0.024 |

| male, n (%) | 685 (40) | 130 (35) | 465 (44) | ref. | |

| Age, in years | |||||

| mean (standard deviation) | 50 (12) | 49 (12) | 50 (12) |

per 10 years: 1.14 (1.02 to 1.28) |

0.020 |

| Clinical experience as GP, in years | |||||

| mean (standard deviation) | 18 (11.4) | 17 (11) | 18 (11) |

per 10 years: 1.12 (1.00 to 1.25) |

0.055 |

| Average number of consultations per working day, n (%) | |||||

| < 15 | 197 (12) | 31 (8) | 121 (11) | ref. | – |

| 15–25 | 567 (33) | 123 (33) | 356 (34) | 0.78 (0.48 to 1.25) | 0.30 |

| 26–35 | 468 (27) | 93 (25) | 300 (28) | 0.91 (0.56 to 1.50) | 0.72 |

| > 35 | 474 (28) | 123 (33) | 281 (27) | 0.71 (0.43 to 1.20) | 0.21 |

| Frequency of seeing/treating patients aged ≥ 70 years with polypharmacy, n (%) | |||||

| frequently / very frequently | 1,469 (87) | 310 (84) | 942 (89) | 1.63 (1.15 to 2.32) | 0.006 |

| very rarely / rarely / occasionally | 218 (13) | 60 (16) | 116 (11) | ref. | – |

| Frequency of dealing with the topic of deprescribing medications in daily practice, n (%) | |||||

| frequently / very frequently | 935 (56) | 176 (48) | 638 (60) | 1.53 (1.18 to 1.97) | 0.001 |

| very rarely / rarely / occasionally | 729 (44) | 194 (52) | 420 (40) | ref. | – |

| Frequency of deprescribing medications during consultations in daily practice, n (%) | |||||

| frequently / very frequently | 438 (26) | 76 (21) | 305 (29) | 1.46 (1.09 to 1.97) | 0.012 |

| very rarely / rarely / occasionally | 1,226 (74) | 294 (79) | 753 (71) | ref. | - |

adeprescribing defined as stopping or reducing the dosage of at least one medication; bmedian deprescribing behaviour corresponds to deprescribing or reducing the dosage of at least one medication in all of the 6 hypothetical patients; ccrude odds ratios from multilevel univariate logistic regression; dP-values from univariate logistic regression

Deprescribing decisions

Table 2 shows the percentage of GPs reporting stopping at least one, two or three medications per case vignette. More than 90% (range: 94–95%) of GPs reported that they would deprescribe at least one medication in all the case vignettes without history of CVD whereas the proportion was slightly lower (range: 82–90%) in the case vignettes with history of CVD. Around 70% of GPs (range: 68–78%) opted for deprescribing at least 3 medications in the case vignettes without CVD history while the percentage again was lower (range: 27–59%) in the case vignettes with CVD history. In CVD cases, the proportion of GPs who reported deprescribing medications increased with increasing dependency levels. The sensitivity analysis performed in countries with a response rate > 60% showed the same trends (Additional file 1: Appendix 3).

Table 2.

Percentage of general practitioners (GPs) deprescribing in case vignettes, sorted by GPs’ decisions to deprescribe at least one, two or three medications in the respective case vignette, patients’ level of dependency in activities of daily living, and patients’ history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (N = 1,706)

| Case vignette | Patients’ dependency level | Deprescribing decision | Without history of CVD (95% CI) | With history of CVD (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | low | ||||

| (living in own house, no help needed for activities of daily living) | min. 1 medication | 95.1% (94.0 to 96.1) | 81.6% (79.6 to 83.5) | 13.5% (11.3 to 15.7) | |

| min. 2 medications | 88.2% (86.6 to 89.8) | 60.1% (57.7 to 62.5) | 28.1% (25.2 to 31.0) | ||

| min. 3 medications | 69.2% (66.9 to 71.5) | 26.5% (24.3 to 28.7) | 42.7% (39.6 to 45.9) | ||

| 2 | medium | ||||

| (living in own house, some help needed for activities of daily living) | min. 1 medication | 94.3% (93.1 to 95.5) | 87.4% (85.7 to 89.1) | 6.8% (4.8 to 8.9) | |

| min. 2 medications | 85.8% (84.0 to 87.5) | 68.5% (66.1 to 70.9) | 17.3% (14.3 to 20.3) | ||

| min. 3 medications | 67.6% (65.3 to 70.0) | 36.6% (34.1 to 39.1) | 31.0% (27.6 to 34.5) | ||

| 3 | high | ||||

| (living in nursing home, help needed for nearly all activities of daily living) | min. 1 medication | 94.1% (92.8 to 95.3) | 90.4% (88.8 to 91.9) | 3.7% (1.7 to 5.7) | |

| min. 2 medications | 88.5% (86.8 to 90.1) | 79.2% (77.1 to 81.3) | 9.3% (6.6 to 12.0) | ||

| min. 3 medications | 78.4% (76.2 to 80.5) | 58.6% (56.0 to 61.1) | 19.8% (16.5 to 23.1) | ||

aTwo-sample test of proportions

The multilevel logistic regression model of GPs’ decisions to deprescribe at least one medication in any case vignette, adjusted for GP characteristics, showed that the odds of GPs reporting deprescribing in patients without CVD history were 3 times higher than the odds of GPs reporting to deprescribe in patients with history of CVD (Table 3). The odds of GPs reporting deprescribing in the scenarios with an increased level of dependency were 1.29 to 1.50 times higher than the odds of GPs reporting deprescribing in the scenarios in which patients had lower dependency levels. While GPs’ age was associated with taking deprescribing decisions (OR: 1.14 for 10-year increase, 95% CI: 1.06–1.23), female sex was not (OR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.75–1.05) nor were the average number of consultations per day or the frequency of seeing patients with polypharmacy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic regression model: adjusted effect of patient and general practitioners’ (GPs) characteristics on general practitioners’ decisions to deprescribe at least one medication in any of the case vignettes (N = 1,706)

| Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value | |

| Patient’s history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) | |||

| History of CVD | ref. | – | – |

| No history of CVD | 3.04 | 2.58 to 3.57 | < 0.001 |

| Patient’s level of dependency in activities of daily living | |||

| Low | ref. | - | - |

| Medium | 1.29 | 1.09 to 1.55 | 0.004 |

| High | 1.50 | 1.25 to 1.80 | < 0.001 |

| Age (GP), 10-year increase | 1.14 | 1.06 to 1.23 | < 0.001 |

| Female sex (GP) | 0.89 | 0.75 to 1.05 | 0.167 |

| Number of consultations per day | |||

| < 15 | ref. | – | – |

| 15–25 | 1.04 | 0.77 to 1.40 | 0.79 |

| 26–35 | 1.2 | 0.88 to 1.65 | 0.25 |

| > 35 | 0.94 | 0.68 to 1.30 | 0.698 |

| Frequency of seeing patients with polypharmacy | |||

| Never | ref. | – | – |

| Rarely | 0.64 | 0.18 to 2.28 | 0.497 |

| Occasionally | 0.80 | 0.25 to 2.53 | 0.699 |

| Frequently | 1.27 | 0.39 to 3.87 | 0.728 |

| Very frequently | 1.42 | 0.45 to 4.49 | 0.554 |

The multilevel model accounts for clustering of the GPs at country level

Geographical variation

Figure 1 maps the differences in the per country averages of case vignettes in which GPs from our convenience sample opted for deprescribing in at least one versus at least two medications. The percentages of deprescribing a minimum of one medication ranged from 77% in Bulgaria to 100% in Ukraine, whereas the percentages of deprescribing a minimum of two medications ranged from 58% in Bulgaria to 92% in Denmark. Both maps show variation across countries.

Deprescribing decisions by medication type

Table 4 shows the proportion of GPs who would deprescribe sorted by medication type, CVD history, and level of dependency in ADL. There was little variation in reported deprescribing for pantoprazole, tramadol, and paracetamol among the different levels of dependency and CVD history. For atorvastatin, aspirin, amlodipine, and enalapril the percentages of GPs reporting to deprescribe generally increased with increasing levels of dependency and was lower when there was a history of CVD. Overall, GPs were most likely to deprescribe proton-pump inhibitors and pain medication.

Table 4.

Comparison of crude percentages of general practitioners (GPs) reporting to deprescribe the medications in the case vignettes, sorted by medication type, history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), and dependency level (N = 1,706)

| Medication | Level of dependency in activities of daily living | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Low (case vignette 1) |

Medium (case vignette 2) |

High (case vignette 3) |

|

| Percentage of GPs (95% CI) | Percentage of GPs (95% CI) | Percentage of GPs (95% CI) | |

| Pain medications | |||

| Tramadol 50 mg, twice daily | |||

| Without history of CVD | 63.5% (61.1 to 65.9) | 69.4% (67.0 to 71.7) | 68.5% (66.0 to 70.9) |

| With history of CVD | 57.3% (55.2 to 60.2) | 67.0% (64.5 to 69.4) | 67.6% (65.2 to 70.1) |

| Paracetamol 1 g, three times daily | |||

| Without history of CVD | 47.5% (45.0 to 50.0) | 41.9% (39.4 to 44.5) | 44.9% (42.3 to 47.5) |

| With history of CVD | 43.8% (41.3 to 46.3) | 40.8% (38.3 to 43.4) | 43.6% (41.0 to 46.2) |

| Proton-pump inhibitor | |||

| Pantoprazole 20 mg, once daily | |||

| Without history of CVD | 64.5% (63.0 to 67.8) | 64.4% (61.9 to 66.8) | 67.8% (65.3 to 70.2) |

| With history of CVD | 47.1% (44.6 to 49.6) | 49.0% (46.4 to 51.6) | 55.6% (53.0 to 58.2) |

| Antihypertensive medications | |||

| Amlodipine 5 mg, once daily | |||

| Without history of CVD | 15.2% (13.4 to 17.0) | 18.9% (17.0 to 21.0) | 33.9% (31.4 to 36.4) |

| With history of CVD | 8.7% (7.3 to 10.2) | 15.1% (13.3 to 17.1) | 30.3% (27.9 to 32.8) |

| Enalapril 10 mg, once daily | |||

| Without history of CVD | 7.7% (6.4 to 9.1) | 9.8% (8.3 to 11.4) | 19.4% (17.4 to 21.5) |

| With history of CVD | 2.5% (1.7 to 3.4) | 4.6% (3.6 to 5.8) | 15.5% (13.6 to 17.5) |

| Cholesterol-lowering medication | |||

| Atorvastatin 40 mg, once daily | |||

| Without history of CVD | 59.1% (56.6 to 61.5) | 62.7% (60.2 to 65.2) | 76.8% (74.5 to 78.9) |

| With history of CVD | 13.7% (12.0 to 15.5) | 26.5% (24.3 to 28.9) | 52.5% (49.9 to 55.1) |

| Antiplatelet medication | |||

| Aspirin 100 mg, once daily | |||

| Without history of CVD | 52.1% (49.6 to 54.5) | 49.1% (46.5 to 51.7) | 60.3% (57.7 to 62.8) |

| With history of CVD | 4.3% (3.4 to 5.5) | 7.2% (5.9 to 8.6) | 23.9% (21.7 to 26.2) |

Acronyms: CI Confidence interval; CVD Cardiovascular disease; GP General practitioner

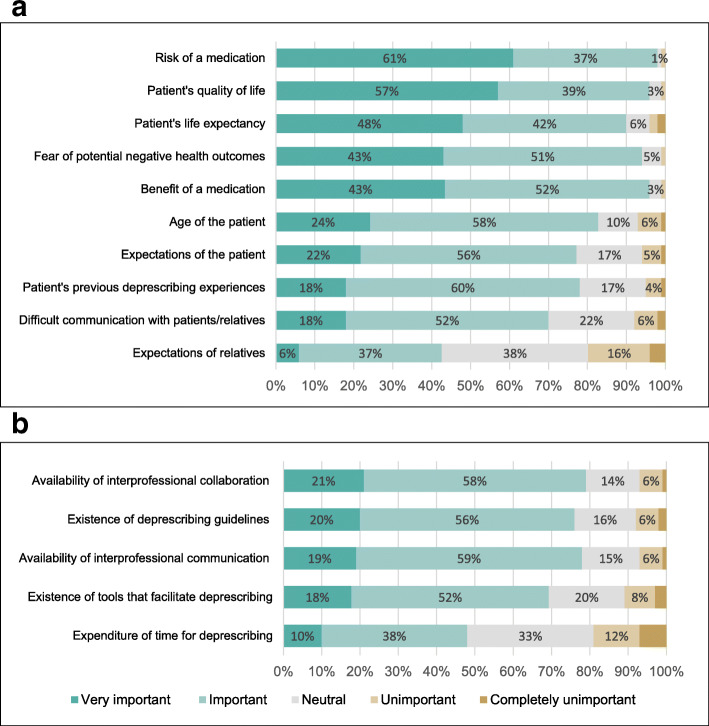

Factors important for deprescribing decisions

Figure 2 shows the importance given to different factors reported to impact GPs’ deprescribing decisions. Risks and benefits of medications, patients’ quality of life, patients’ life expectancy and patients’ fear of potential negative health outcomes were important or very important to more than 90% of GPs. Less than half of GPs rated the time needed for deprescribing as important or very important for making deprescribing decisions.

Fig. 2.

Factors important to general practitioners (GPs) when making deprescribing decisions1, ordered by importance (N = 1,706). a) factors related to the patient, and b) factors related to the GP. 1each GP was asked to rate the importance of each factor

Discussion

In this study of over 1,700 GPs from 31 countries, we investigated GPs’ deprescribing decisions in oldest-old patients with polypharmacy. Despite differences across GP characteristics and across countries, a large proportion of GPs reported that they would deprescribe at least one medication in all scenarios. The odds of GPs reporting decisions to deprescribe was higher in patients with a higher dependency level (OR =1.5, 95%CI, 1.25 to 1.80) and in absence of CVD history (OR =3.04, 95%CI 2.58 to 3.57). The medications GPs were most willing to deprescribe in case vignettes with and without history of CVD were pain medications and proton-pump inhibitors. However, history of CVD appeared to affect deprescribing decisions of certain medications. While GPs were likely to deprescribe cholesterol medication used for primary prevention (no history of CVD), GPs were less likely to deprescribe those medications when used for secondary prevention. Factors GPs rated as important or very important for deprescribing decisions were patients’ quality of life, life expectancy, fear of potential negative health outcomes resulting from deprescribing, and the risks and benefits of medications.

This is the first study to examine deprescribing decisions of GPs across a large number of countries. We found variation in deprescribing decisions across countries and based on GP characteristics, such as age with older GPs being more likely to take deprescribing decisions. Bolmsjö et al. (2016) found that deprescribing behaviours were largely dependent on the structure of healthcare systems [35]. This might explain the differences we found between countries. Previous qualitative studies reported that GPs with greater clinical experience were more able to draw on their own clinical knowledge [36–39], which might explain why older and more experienced GPs in our sample were more likely to deprescribe. Further research is needed to explore the association between GP characteristics and deprescribing in more depth.

Our findings show that GPs were willing to deprescribe in patients with high dependency and increasing cognitive impairment. The results built on a first analysis with the Swiss data from the LESS study, in which we had only included the most dependent, least robust oldest-old adults (case vignette 3) and found that GPs reported to be influenced by the risk and benefit of medications, quality of life and life expectancy when taking deprescribing decisions [28]. Our findings are in line with previous research, which revealed cognitive impairment as an important factor for deprescribing [40]. This also aligns with the basic principles of appropriate medication use which contend that potential benefits of the medication should outweigh potential risks and align with the goals of care of the individual [19]. As mentioned before, the benefit-risk profile of dependent and less robust older adults is altered as they are at greater risk of medication induced harm and may not have sufficient remaining life span to benefit from preventive medications [18, 19]. That GPs seem more willing to deprescribe in older adults with increased dependency levels implies that we need better ways to identify such patients in primary care settings. The routine use of frailty screening tools in primary care is gaining interest. However, it remains unclear which tools are the most useful and feasible and how to best deliver care for those identified as frail and less robust [41, 42]. Furthermore, despite the fact that certain tools exist to conduct deprescribing in older adults with frailty or limited life expectancy, little is known about how such tools can be used in a way that reduces inappropriate medication use and improves clinical outcomes [43].

In line with a qualitative study by Luymes et al., we found that GPs were more likely to deprescribe in patients with a lower CVD risk [33]. A recent national cross-sectional survey of US geriatricians, general internists, and cardiologists found that > 90% of physicians in each specialty reported to deprescribe cardiovascular medications when patients experienced adverse drug reactions [44]. In addition, this study also pointed out potential barriers linked to the communication between physicians when making deprescribing decision. Our finding of the impact of CVD on deprescribing, however, is likely driven by the fact that four out of the seven medications in the case vignette are related to the cardiovascular system. Further research is warranted to find ways to overcome the barriers linked to inter-professional communication, as this is crucial for sustainable deprescribing.

The medications presented in our case vignettes are commonly used in older adults. However, some of them are considered potentially inappropriate to be used in older adults. For instance, according to the 2019 Beers criteria aspirin should not be used for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, tramadol should be used with caution as it may cause or exacerbate the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone, and the use of proton pump inhibitors for more than eight weeks should be avoided in non-high-risk patients [45]. In this study, GPs were most likely to opt for deprescribing proton pump inhibitors and pain medication in case vignettes with and without history of CVD while they were least likely to deprescribe antihypertensive medications. GPs were also likely to deprescribe aspirin and atorvastatin for primary prevention. This shows that GPs in our sample were likely to opt for deprescribing medications that are potentially inappropriate when used in older adults. This awareness needs to be built upon when shifting deprescribing from theory to practice. Generally reported deprescribing was high among the GPs when considering the medications as a whole. However, the results for aspirin show that there remain barriers to deprescribing even in hypothetical scenarios. In 2018 three large studies established that aspirin for primary prevention of CVD has a greater risk of harm and shows relatively modest benefits in relation to cardiovascular outcomes [46–48]. Therefore it would be interesting to see whether our study would yield different results (pertaining to aspirin) if it was repeated.

Further research is needed to create thorough guidance on how to deprescribe in older adults with potentially inappropriate polypharmacy, which includes studying the safety of deprescribing in this population group and to further investigate patient barriers to deprescribing [28]. Over 70% of GPs in our study perceive the existence of deprescribing guidelines and tools that facilitate deprescribing as important or very important. This underscores the need for creating such guidelines, not just on when to deprescribe but also how to deprescribe. It also points to a need to raise awareness of currently existing guidelines and potential benefits of translating guidelines to local languages. Currently, evidence-based deprescribing clinical practice guidelines exist for proton pump inhibitors, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, antihyperglycemics, antipsychotics and cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine [49–53]. Furthermore, an in-depth exploration into the nuanced reasons why GPs do or do not deprescribe specific medications in specific situations and into how deprescribing could be sustainably implemented will be useful for improving deprescribing practices and guidelines.

Our study is strengthened by the inclusion of a large number of GPs from many different countries in Europe and beyond, some of which are rarely included in studies among GPs. Furthermore, the average response rate of 53% is higher than typical response rates of 30–40% in surveys among GPs [54]. The LESS study comes with several limitations. The first one is the hypothetical nature of our case vignettes, which were intended to establish and correspond to GPs’ routine clinical practice [28]. However, we were not able to capture the decision-making process, including barriers and facilitators of deprescribing, such as time limitations and patient preferences, values or goals of care, or capture the reasons why GPs selected to deprescribe or not. Therefore, the results of this study may not reflect the complex process of shared decision making. That said, the simple nature of the hypothetical case vignettes is also a strength, as it allowed gathering of a large number of responses from GPs in standardized cases. Second, we do not know how reported deprescribing decisions would transfer to other medications not included in the case vignettes. Third, we did not randomly sample the GPs in each country but performed a convenience sample based on the networks of our national coordinators, which comes with limited generalizability of our study results. Despite this, to maximise the number of countries involved in order to increase generalisability by reaching a larger number of GPs, we allowed for variations in the types of networks that national co-ordinators used to recruit participants. The variation in the types of networks used was also reflected in the large variation in response rates by country. In addition, GPs self-selecting to complete the survey were likely to be more interested in deprescribing, which may mean that our results could be biased towards overestimating deprescribing decisions. Fourth, we were limited to the self-reported data about GPs’ deprescribing decisions, which might have been affected by social desirability bias and the order in which case vignettes were presented. Fifth, we do not know to what extent the reported deprescribing decisions reflect or were influenced by national deprescribing guidelines or other deprescribing initiatives.

Conclusions

Despite international variation, most GPs in our convenience sample reported they would deprescribe at least one medication in hypothetical oldest-old multimorbid patients with polypharmacy. Older GPs were more likely to take deprescribing decisions. GPs were more likely to deprescribe in patients with a higher dependency in activities of daily living and in the absence of a history of cardiovascular disease. Overall, medications most often chosen for deprescribing in the presented case vignettes were proton pump inhibitors and pain medications. Antiplatelet and cholesterol-lowering medication was frequently selected for deprescribing when used for primary prevention.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Arnaud Chiolero for his inputs on the study design, Michael Deml for his editorial suggestions, and all the participants.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- CHERRIES

Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys

- CI

Confidence interval

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- EGPRN

European General Practice Research Network

- GPs

General practitioners

- LESS

barriers and enabLers to willingnESs to depreScribing in older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy and their General Practitioners

- OR

Odds ratio

- PIM

Potentially inappropriate medication

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: KTJ, SM, ZR, ER, CL, RKEP, NR, JG, SS. Acquisition of data: KTJ (Switzerland and all other countries), SM (Switzerland), ZR (Switzerland), AM (Greece), BGK (Macedonia), BW (Germany), CM (England/UK), CC (Ireland), DB (Brazil), DK (Poland), FP (Italy), GD (Romania), HT (Sweden), HL (Germany), KLJ (Denmark), KW (New Zealand), KH (Austria), LPeremans (Belgium), LPiilv (Estonia), MPS (Slovenia), MB (Germany), MS (Luxembourg), MVDP (the Netherlands), PT (Hungary), PBK (Czech Republic), SV (Israel), RA (Bulgaria), RGB (Spain), RPAV (Portugal), RT (France), SKP (Bosnia), SG (Latvia), THK (Finland), VL (Croatia), VT (Ukraine), CL (the Netherlands), SS (Switzerland and support of data collection in all other countries). Statistical analysis: KTJ and SS had full access to all data in the study. All authors (KTJ, SM, ZR, AM, BGK, BW, CM, CC, DB, DK, FP, GD, HT, HL, KLJ, KW, KH, LPeremans, LPiilv, MPS, MB, MS, MVDP, PT, PBK, SV, RA, RGB, RPAV, RS, SKP, SG, THK, VL, VT, ER, CL, RKEP, NR, JG, and SS) take responsibility for the integrity of data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Interpretation of data: All authors (KTJ, SM, ZR, AM, BGK, BW, CM, CC, DB, DK, FP, GD, HT, HL, KLJ, KW, KH, LPeremans, LPiilv, MPS, MB, MS, MVDP, PT, PBK, SV, RA, RGB, RPAV, RS, SKP, SG, THK, VL, VT, ER, CL, RKEP, NR, JG, and SS). Drafting of the manuscript: KTJ created a first draft. Critical revision of the manuscript: All authors (KTJ, SM, ZR, AM, BGK, BW, CM, CC, DB, DK, FP, GD, HT, HL, KLJ, KW, KH, LPeremans, LPiilv, MPS, MB, MS, MVDP, PT, PBK, SV, RA, RGB, RPAV, RS, SKP, SG, THK, VL, VT, ER, CL, RKEP, NR, JG, and SS) have revised multiple drafts of the manuscript and approved of the submission. Obtained funding: SS, NR, RKEP, and JG. Administrative, technical, or material support: SS. Study supervision: SS.

Funding

The work of Katharina Tabea Jungo was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) (NFP 407440_167465, PI Prof. Streit) and the work of Zsofia Rozsnyai by the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine (SGAIM) Foundation (PI Prof. Streit). The SGAIM Foundation reviewed the study protocol but did not give us feedback or help us plan, conduct, interpret results, or write this manuscript. The SNSF had the same role but did not review the study protocol. CM is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaborations (West Midlands), the NIHR School for Primary Care Research and an NIHR Research Professorship in General Practice (RP 2014–04-026). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. ER is supported by an NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton of Bern in Switzerland (reference number 2017–02188), the Albert Einstein Ethics Committee in Brazil (reference number: 90812118.3.0000.0071), the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee in New Zealand (reference number 017502), the RSU Research Ethics Committee (reference number 58 / 28.06.2018) in Latvia, and the Commission of Ethics and Professional Deontology of the Dolj College of Doctors in Romania (reference number: nr.1 din 24102018). The Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the “Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität” in Germany issued a waiver (ref. 117/18). In the remaining countries, no country-specific ethical approval was required. Participating GPs were informed about the aim of the study. They gave their informed consent by clicking to proceed to respond to the online questionnaire after reading the introduction to the survey. Participation was voluntary. This procedure was approved by the above-mentioned ethics committees. All responses were collected anonymously. No incentive was given to participating GPs.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Katharina Tabea Jungo, Email: katharina.jungo@biham.unibe.ch.

Sophie Mantelli, Email: sophie.mantelli@gmail.com.

Zsofia Rozsnyai, Email: zsofia.rozsnyai@biham.unibe.ch.

Aristea Missiou, Email: teta_st@hotmail.com.

Biljana Gerasimovska Kitanovska, Email: bgerasimovska@yahoo.com.

Birgitta Weltermann, Email: Birgitta.Weltermann@ukbonn.de.

Christian Mallen, Email: c.d.mallen@keele.ac.uk.

Claire Collins, Email: Claire.Collins@ICGP.IE.

Daiana Bonfim, Email: daiana.bonfim@einstein.br.

Donata Kurpas, Email: dkurpas@hotmail.com.

Ferdinando Petrazzuoli, Email: ferdinando.petrazzuoli@gmail.com.

Gindrovel Dumitra, Email: dumitragino@yahoo.com.

Hans Thulesius, Email: hansthulesius@gmail.com.

Heidrun Lingner, Email: Lingner.Heidrun@mh-hannover.de.

Kasper Lorenz Johansen, Email: kasperlorenz@gmail.com.

Katharine Wallis, Email: k.wallis@uq.edu.au.

Kathryn Hoffmann, Email: kathryn.hoffmann@meduniwien.ac.at.

Lieve Peremans, Email: lieve.peremans@uantwerpen.be.

Liina Pilv, Email: liina.pilv@ut.ee.

Marija Petek Šter, Email: marija.petek-ster@mf.uni-lj.si.

Markus Bleckwenn, Email: Markus.Bleckwenn@medizin.uni-leipzig.de.

Martin Sattler, Email: martin_sattler@hotmail.com.

Milly van der Ploeg, Email: m.a.vanderploeg@lumc.nl.

Péter Torzsa, Email: ptorzsa@gmail.com.

Petra Bomberová Kánská, Email: petra.ami@gmail.com.

Shlomo Vinker, Email: vinker01@zahav.net.il.

Radost Assenova, Email: radost_assenova@yahoo.com.

Raquel Gomez Bravo, Email: raquelgomezbravo@gmail.com.

Rita P. A. Viegas, Email: ritapaviegas@gmail.com

Rosy Tsopra, Email: rosy.tsopra@nhs.net.

Sanda Kreitmayer Pestic, Email: kreitmayerdrsanda@yahoo.com.

Sandra Gintere, Email: Sandra.Gintere@rsu.lv.

Tuomas H. Koskela, Email: tuomas.koskela@tuni.fi

Vanja Lazic, Email: vanjlaz@gmail.com.

Victoria Tkachenko, Email: witk@ukr.net.

Emily Reeve, Email: Emily.Reeve@unisa.edu.au.

Clare Luymes, Email: C.H.Luymes@lumc.nl.

Rosalinde K. E. Poortvliet, Email: R.K.E.Poortvliet@lumc.nl

Nicolas Rodondi, Email: nicolas.rodondi@biham.unibe.ch.

Jacobijn Gussekloo, Email: J.Gussekloo@lumc.nl.

Sven Streit, Email: sven.streit@biham.unibe.ch.

References

- 1.Morin L, Johnell K, Laroche ML, Fastbom J, Wastesson JW. The epidemiology of polypharmacy in older adults: register-based prospective cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:289–98. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S153458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herr M, Grondin H, Sanchez S, Armaingaud D, Blochet C, Vial A, et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications: a cross-sectional analysis among 451 nursing homes in France. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(5):601–608. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdulah R, Insani WN, Barliana MI. Polypharmacy leads to increased prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication in the Indonesian geriatric population visiting primary care facilities. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;2018(14):1591–1597. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S170475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alhawassi TM, Alatawi W, Alwhaibi M. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications use among older adults and risk factors using the 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers criteria. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen JK, Fouts MM, Kotabe SE, Lo E. Polypharmacy as a risk factor for adverse drug reactions in geriatric nursing home residents. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(1):36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, O’Mahony D. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized PatientsPIMs defined by STOPP criteria and risk of ADEs. JAMA Intern Med. 2011;171(11):1013–1019. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindblad CI, Artz MB, Pieper CF, Sloane RJ, Hajjar ER, Ruby CM, et al. Potential drug-disease interactions in frail, hospitalized elderly veterans. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(3):412–417. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindblad CI, Hanlon JT, Gross CR, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF, Hajjar ER, et al. Clinically important drug-disease interactions and their prevalence in older adults. Clin Ther. 2006;28(8):1133–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crentsil V, Ricks MO, Xue QL, Fried LP. A pharmacoepidemiologic study of community-dwelling, disabled older women: factors associated with medication use. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8(3):215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jyrkka J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(5):514–522. doi: 10.1002/pds.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corsonello A, Pedone C, Lattanzio F, Lucchetti M, Garasto S, Di Muzio M, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications and functional decline in elderly hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):1007–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koyama A, Steinman M, Ensrud K, Hillier TA, Yaffe K. Long-term cognitive and functional effects of potentially inappropriate medications in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(4):423–429. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher PC, Berg K, Dalby DM, Hirdes JP. Risk factors for falling among community-based seniors. J Patient Safety. 2009;5(2):61–66. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181a551ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masumoto S, Sato M, Maeno T, Ichinohe Y, Maeno T. Potentially inappropriate medications with polypharmacy increase the risk of falls in older Japanese patients: 1-year prospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(7):1064–1070. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyttinen V, Jyrkka J, Valtonen H. A systematic review of the impact of potentially inappropriate medication on health care utilization and costs among older adults. Med Care. 2016;54(10):950–964. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnaswami A, Steinman MA, Goyal P, Zullo AR, Anderson TS, Birtcher KK, et al. Deprescribing in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(20):2584–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG. Thinking through the medication list - appropriate prescribing and deprescribing in robust and frail older patients. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(12):924–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeve E, Trenaman SC, Rockwood K, Hilmer SN. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic alterations in older people with dementia. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13(6):651–668. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2017.1325873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, et al. Reducing inappropriate Polypharmacy: the process of DeprescribingReducing inappropriate PolypharmacyReducing inappropriate Polypharmacy. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827–834. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank C. Deprescribing: a new word to guide medication review. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186(6):407–408. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, Hilmer S. A systematic review of the emerging de fi nition of 'deprescribing' with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(6):1254–1268. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust. 2014;201(7):386–389. doi: 10.5694/mja13.00200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sibbald B. Reducing inappropriate prescribing easier said than done. Can Med Assoc J. 2017;189(19):E706–E7E7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1095427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullinan S, Raae Hansen C, Byrne S, O'Mahony D, Kearney P, Sahm L. Challenges of deprescribing in the multimorbid patient. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(1):43–46. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallis KA, Andrews A, Henderson M. Swimming against the tide: primary care Physicians' views on Deprescribing in everyday practice. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(4):341–346. doi: 10.1370/afm.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reeve E, To J. Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793–807. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeve E, Low LF, Hilmer SN. Beliefs and attitudes of older adults and carers about deprescribing of medications: a qualitative focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(649):e552–e560. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X685669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantelli S, Jungo KT, Rozsnyai Z, Reeve E, Luymes CH, Poortvliet RKE, et al. How general practitioners would deprescribe in frail oldest-old with polypharmacy - the LESS study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streit S, Verschoor M, Rodondi N, Bonfim D, Burman RA, Collins C, et al. Variation in GP decisions on antihypertensive treatment in oldest-old and frail individuals across 29 countries. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0486-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Ploeg MA, Streit S, Achterberg WP, Beers E, Bohnen AM, Burman RA, et al. Patient characteristics and general Practitioners’ advice to stop statins in oldest-old patients: a survey study across 30 countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1751–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Eysenbach G. Correction: improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luymes CH, van der Kleij RM, Poortvliet RK, de Ruijter W, Reis R, Numans ME. Deprescribing potentially inappropriate preventive cardiovascular medication: barriers and enablers for patients and general practitioners. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(6):446–454. doi: 10.1177/1060028016637181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006544. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolmsjo BB, Palagyi A, Keay L, Potter J, Lindley RI. Factors influencing deprescribing for residents in advanced care facilities: insights from general practitioners in Australia and Sweden. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0551-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson K, Foster M, Freeman C, Luetsch K, Scott I. Negotiating "Unmeasurable harm and benefit": perspectives of general practitioners and consultant pharmacists on Deprescribing in the primary care setting. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(13):1936–1947. doi: 10.1177/1049732316687732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moen J, Norrgard S, Antonov K, Nilsson JL, Ring L. GPs' perceptions of multiple-medicine use in older patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(1):69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJ, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinnott C, Hugh SM, Boyce MB, Bradley CP. What to give the patient who has everything? A qualitative study of prescribing for multimorbidity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(632):e184–e191. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X684001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ní Chróinín D, Ní Chróinín C, Beveridge A. Factors influencing deprescribing habits among geriatricians. Age Ageing. 2015;44(4):704–708. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbasi M, Rolfson D, Khera AS, Dabravolskaj J, Dent E, Xia L. Identification and management of frailty in the primary care setting. Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190(38):E1134–E1E40. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.171509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davies BR, Baxter H, Rooney J, Simons P, Sephton A, Purdy S, et al. Frailty assessment in primary health care and its association with unplanned secondary care use: a rapid review. BJGP Open. 2018;2(1):bjgpopen18X101325. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen18X101325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson W, Lundby C, Graabæk T, Nielsen DS, Ryg J, Søndergaard J, et al. Tools for Deprescribing in frail older persons and those with limited life expectancy: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(1):172–180. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goyal P, Anderson TS, Bernacki GM, Marcum ZA, Orkaby AR, Kim D, et al. Physician perspectives on Deprescribing cardiovascular medications for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(1):78–86. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, Lockery JE, Wolfe R, Reid CM, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(16):1519–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, Stevens W, Buck G, Barton J, et al. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(16):1529–1539. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, Cricelli C, Darius H, Gorelick PB, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1036–1046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31924-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, Boghossian T, Pizzola L, Rashid FJ, et al. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors. Evid Based Clin Pract Guideline. 2017;63(5):354–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reeve E, Farrell B, Thompson W, Herrmann N, Sketris I, Magin PJ, et al. Deprescribing cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in dementia: guideline summary. Med J Aust. 2019;210(4):174–179. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farrell B, Black C, Thompson W, McCarthy L, Rojas-Fernandez C, Lochnan H, et al. Deprescribing antihyperglycemic agents in older persons. Evid Based Clin Pract Guideline. 2017;63(11):832–843. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bjerre LM, Farrell B, Hogel M, Graham L, Lemay G, McCarthy L, et al. Deprescribing antipsychotics for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia and insomnia: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Canadian Fam Phys Medecin de famille canadien. 2018;64(1):17–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pottie K, Thompson W, Davies S, Grenier J, Sadowski CA, Welch V, et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Canadian Fam Phys Medecin de famille canadien. 2018;64(5):339–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McAvoy BR, Kaner EF. General practice postal surveys: a questionnaire too far? Bmj. 1996;313(7059):732–733. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.