Abstract

Background

Despite excellent operative survival, correction of tetralogy of Fallot frequently is accompanied by residual lesions that may affect health beyond the incident hospitalization. Measuring resource utilization, specifically cost and length of stay, provides an integrated measure of morbidity not appreciable in traditional outcomes.

Methods and Results

We conducted a retrospective cohort study, using de‐identified commercial insurance claims data, of 269 children who underwent operative correction of tetralogy of Fallot from January 2004 to September 2015 with ≥2 years of continuous follow‐up (1) to describe resource utilization for the incident hospitalization and subsequent 2 years, (2) to determine whether prolonged length of stay (>7 days) in the incident hospitalization was associated with increased subsequent resource utilization, and (3) to explore whether there was regional variation in resource utilization with both direct comparisons and multivariable models adjusting for known covariates. Subjects with prolonged incident hospitalization length of stay demonstrated greater resource utilization (total cost as well as counts of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and catheterizations) after hospital discharge (P<0.0001 for each), though the number of subsequent operative and transcatheter interventions were not significantly different. Regional differences were observed in the cost of incident hospitalization as well as subsequent hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and the costs associated with each.

Conclusions

This study is the first to report short‐ and medium‐term resource utilization following tetralogy of Fallot operative correction. It also demonstrates that prolonged length of stay in the initial hospitalization is associated with increased subsequent resource utilization. This should motivate research to determine whether these differences are because of modifiable factors.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, health services research, outcomes, pediatrics

Subject Categories: Quality and Outcomes, Congenital Heart Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IQR

interquartile range

- LOS

length of stay

- TOF

tetralogy of Fallot

- US$

2016 United States dollars

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Morbidity and prolonged length of stay during the incident hospitalization after operative correction of tetralogy of Fallot is associated with increased resource utilization in the following 2 years.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Though further research is necessary, the data presented suggest that perioperative mortality insufficiently describes the variability in health and well‐being of patients after operative correction of tetralogy of Fallot, and that strategies of care that reduce the risk of early morbidity may have durable benefits in this patient population.

In contemporary series, early mortality after operative correction of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is <2% across a wide range of hospitals.1, 2, 3 However, this may overestimate the health and well‐being of children after this operation. Residual anatomic lesions such as branch pulmonary artery stenosis and recurrent right ventricular outflow tract obstruction are common.1 These lesions can have significant hemodynamic consequences that may eventually require transcatheter and/or surgical interventions,4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 as well as increased utilization of both outpatient and inpatient care. The magnitude of this morbidity and its variability are not described in case series using traditional outcome metrics. The coincidence of residual lesions and intensive medical care both in terms of re‐intervention and medical follow‐up in TOF and other conotruncal anomalies are associated with diminished health‐related quality of life and functional status.10, 11, 12

Previously, the cumulative impact of postoperative morbidity on children's health has been challenging to measure, especially in observational data sets, because it is manifest in multiple events (not only increased re‐interventions but also inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient encounters) whose relative importance is hard to compare. Cost data have been used to overcome this obstacle. They not only measure the accumulated economic impact of medical care but also integrate intensity and frequency of medical care and morbidity, which provides a surrogate for cumulative morbidity.13, 14, 15, 16 This provides a statistically expedient and potentially more comprehensible measure than counts of individual encounters and/or interventions. Previous studies have demonstrated that the costs during the hospitalization increase in patients with postoperative complications and longer total length of stay (LOS).17, 18, 19 We hypothesize that resource utilization over the first 2 years after operative correction is a potentially valuable proxy for the health and well‐being of these patients and may help inform decisions about how best to care for these patients. To our knowledge, this has not been studied in patients after operative correction of TOF.

To that end, we performed a retrospective cohort study using commercial insurance claims data to generate a national sample and characterize resource utilization over the first 2 years after operative correction of TOF. Second, we sought to determine whether early morbidity (reflected in prolonged LOS in the incident hospitalization) was associated with higher costs of subsequent care. We hypothesized that early morbidity is associated with persistent increases in morbidity and cost over the follow‐up period. Finally, we sought to explore whether these costs varied between geographic regions.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis using the Optum de‐identified Clinformatics DataMart (OptumInsight, Eden Prairie, MN), a de‐identified administrative health database, including claims data from recipients of commercial health insurance and Medicare Advantage (C and D). This database, updated annually, comprises 63 million unique individuals, spanning all 50 states, providing a geographically representative sample of children and families. It does not include recipients of Medicaid who represent a significant minority (30%–40%) of children with congenital heart disease seen in other studies using observational data sets.14, 15, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Therefore, the resulting study population has a higher socioeconomic status than the total population with TOF. The DataMart comprises detailed enrollment information, medical records, prescription drug use, and inpatient hospitalization data. The study team had full access to the data. Data cannot be made publicly available because that runs contrary to our data use agreement. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and was judged as not constituting human subjects research in accordance with the Common Rule (45 CFR 46.102(f)).

Study Population

We identified subjects who underwent operative correction for TOF from January 1, 2004 and September 30, 2015 as defined by the (ICD‐9) procedure code for complete TOF operative correction (35.81). To ensure data completeness and avoid bias, we restricted analysis to subjects with continuous enrollment in the database for at least 2 years after the admission where operative correction was performed, the incident hospitalization. This choice prioritizes generating a complete data set over generating the largest possible sample. To evaluate for potential selection bias, the demographics and LOS following operative correction were compared between study subjects (those with >2 years of continuous data) and those with <2 years of data. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups (Table S1). These inclusion criteria also exclude children who died during their initial hospitalization. By definition there is no resource utilization after discharge for subjects who die during their initial hospitalization; therefore their omission does not bias or influence our primary outcome. Two years of follow‐up was chosen because previous studies have demonstrated that the greatest intensity (frequency and severity) of resource utilization occurs in the first 2 years after operative correction for TOF8, 9, 25 and other conotruncal anomalies.10, 11

Study Measures and Variables

Data were extracted directly from the Optum de‐identified Clinformatics DataMart and included age (measured in integer years), sex, race (white versus nonwhite), total household income, and highest household education level. Geographic regions were divided into the 4 United States Census Bureau regions: (Midwest, Northeast, South, and West). The following subject level covariates were also extracted (using [ICD‐9 and ICD‐10] codes): prematurity (gestational age <37 weeks), genetic syndromes (including Alagille syndrome, CHARGE association, 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, Kabuki syndrome, Noonan syndrome, Williams syndrome, Turner syndrome, Trisomy 21, Trisomy 13, Trisomy 18, cri du chat, VATER association, and Holt‐Oram syndrome), and extracardiac malformations (including cleft palate, cleft lip, esophageal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula, duodenal atresia, anal atresia, biliary atresia, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, intestinal malrotation, gastroschisis, omphalocele, and renal agenesis). ICD‐10 codes were used to identify these covariates starting in October 1, 2015.

Data for the incident hospitalization and for subsequent health care were collected. Total standardized costs were calculated for each inpatient and outpatient visit. Adjustments for inflation were performed by correcting all costs to 2016 United States dollars (US$2016) using the consumer price index for medical care. To account for differences in pricing across health plans and provider contracts, Optum applies standard pricing algorithms to the claims data in the de‐identified Clinformatics DataMart. These algorithms are designed to create standard prices that reflect allowed payments for all provider services across regions. For example, professional service rates are standardized using a resource‐based relative value scale approach with prices standardized at ≈130% of Medicare Fee for Service amounts. Cases with costs listed as ≤US$0 were excluded. Other component measures of resource utilization that were collected were total hospital LOS for the incident and subsequent hospitalizations, number of hospitalizations and number of cardiac surgeries following initial TOF operative correction, number of cardiac catheterizations, outpatient visits, emergency room visits, ECGs, and echocardiograms. The number of outpatient visits was defined as the sum of cardiac‐specific (defined as primary diagnosis of a cardiology‐related code) and noncardiac visits. Segregating costs during initial and subsequent inpatient admissions between cardiac and noncardiac admissions/services was not possible.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the baseline characteristics, including demographics and comorbidities. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are presented as medians and interquartile range (IQR).

We then described resource utilization in the incident hospitalization and subsequent 2 years of follow‐up after TOF operative correction using total cost as the primary outcome and number of hospitalizations and other services as secondary outcomes. Second, we studied the association between postoperative morbidity (represented by increased LOS during the incident hospitalization) and persistently increased resource utilization (indicative of ongoing morbidity). For this analysis, we divided the sample into 2 groups based on the median LOS for the entire cohort (7 days) with a shorter LOS (ie, LOS ≤7 days) and prolonged LOS Group (LOS >7 days). Though evaluating for the specific cut point for LOS would be important and useful, this is not feasible in the relatively small data set we have available, so no analyses using splines or other techniques were performed. We used all available hospitalizations (ie, not restricted to cardiology visits) for each subject after the incident hospitalization within the 2‐year period and aggregated the outcomes. Univariable and multivariable generalized linear models were used to test whether prolonged LOS in the incident hospitalization was associated with greater resource utilization in subsequent follow‐up. We modeled count outcomes (number of outpatient visits, catheterizations, subsequent hospitalization(s)) using a Poisson distribution. Likelihood of dichotomous outcomes (eg, having at least 1 subsequent hospitalization) were modeled with a binomial frequency distribution (with a logit link). For cost data, gamma distributions were used as described previously. Covariates included sex, parental education, age at surgery, prematurity, genetic syndrome, extracardiac malformation, and census region. Because ages are rounded to the nearest whole year, it is not possible to determine which subjects underwent neonatal operative correction, a group at higher risk for adverse outcome and reintervention.26 Also, since the analysis focused on the association between hospital course after correction and subsequent resource utilization, palliation with Blalock‐Taussig shunt or other means was not included as a covariate. Since costs were adjusted for regional wage–price indices, census region was not included as a covariate in multivariable models of cost.

Next we studied regional variation in resource utilization. The Kruskall–Wallis test was used to test whether the LOS of the incident hospitalization differed between census regions and to evaluate the association between census regions and the likelihood of subsequent hospitalizations. Before analysis, there was no suspicion that patient clinical characteristics would vary between census regions, but we did suspect that race and family socioeconomic status might vary. To address this, we calculated estimates of LOS and cost adjusted for race and maternal educational level using generalized linear models with a gamma distribution. There is no criterion standard modeling strategy for costs and LOS, which are inherently ≥0 and skewed. Gamma frequency distributions were used to model total cost because they have demonstrated benefits for analysis of cost data in simulations27 and have been used extensively in previous studies in young patients with cardiac disease.14, 15, 20, 22, 28

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A threshold for significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Study Population

In total, 543 subjects met initial criteria for inclusion. Of these, 50% (n=269) had continuous enrollment data for at least 2 years following operative correction and were evaluated. Baseline demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Overall, 53% of subjects were male, and 65% were white. South (49%) and Midwest (25%) census regions accounted for a higher proportion of cases. Total annual household income was >US$100 000 for 42% of subjects for whom income was recorded.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics (n=269)

| Male sex | 143 (53) |

| White race (vs other races) | 176 (65) |

| Age at operative correction, y | |

| 0 | 133 (49) |

| 1 | 121 (45) |

| 2 | 15 (6) |

| Regions | |

| Northeast | 28 (10) |

| Midwest | 68 (25) |

| South | 131 (49) |

| West | 42 (16) |

| Parental highest education level | |

| <12th grade | 3 (1) |

| High school diploma | 48 (18) |

| <Bachelor's degree | 125 (46) |

| Bachelor's degree plus | 89 (33) |

| Unknown/missing | 4 (1) |

| Family annual income | |

| <$40K | 15 (6) |

| $40K–$49K | 13 (5) |

| $50K–$59K | 13 (5) |

| $60K–$74K | 16 (6) |

| $75K–$99K | 35 (13) |

| >$100K | 112 (42) |

| Unknown/missing | 65 (24) |

| Insurance type | |

| Point of service | 187 (70) |

| Exclusive provider organizations | 36 (13) |

| Health maintenance organizations | 33 (12) |

| Preferred provider organization | 12 (4) |

| Other | 1 (0.4) |

Data are presented as N (%).

Resource Utilization

The median LOS for the incident hospitalization was 7 days (IQR 5, 11), with a median cost of US$58 362 (IQR: 43 672, 87 680). Of 269 subjects, 96 (36%) had at least 1 subsequent hospitalization with a total of 215 repeat hospitalizations. Subsequent hospitalizations had a median LOS of 6 days per admission (IQR 3–12), with corresponding median cost of US$26 280 (IQR 11 712, 78 457). Subsequent cardiac surgeries (within 2 years of operation correction) occurred in 40 subjects (15%), and 32 (12% of the total population) underwent >1 subsequent operation. Forty‐nine subjects (18%) had subsequent cardiac catheterizations, 32 (12%) of whom had >1 catheterization. The median number of outpatient cardiology visits was 6 (IQR 4, 8) and of emergency room visits was 1 (IQR 0, 2).

Association of Prolonged LOS After TOF Operative Correction and Later Resource Utilization

To determine whether morbidity after the incident operation was associated with increased resource utilization after discharge, the population was divided between subjects with greater than median LOS (>7 days) during their incident hospitalization for operative correction and those with shorter LOS. The baseline characteristics of subjects with prolonged initial LOS differed significantly from those with shorter LOS (Table 2). Subjects with prolonged LOS had higher likelihood of noncardiac malformations (P=0.04), genetic syndromes (P=0.0003), and younger age at initial TOF operative correction (P=0.01). The proportion with a history of prematurity was higher (23% versus 14%) but this association was not significant (P=0.06).

Table 2.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics of Subjects With Prolonged and Shorter Total Hospital Length of Stay During Incident Hospitalization

| LOS ≤7 d (n=151) | LOS >7 d (n=118) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 83 (55) | 60 (51) | 0.50 |

| White race | 97 (64) | 79 (67) | 0.64 |

| Age at surgery, y | 0.01 | ||

| <1 y | 67 (44) | 66 (56) | |

| 1–2 y | 79 (52) | 42 (36) | |

| ≥2 | 5 (3) | 10 (9) | |

| Regions | 0.38 | ||

| Northeast | 20 (13) | 8 (7) | |

| Midwest | 37 (25) | 31 (26) | |

| South | 72 (48) | 59 (50) | |

| West | 22 (15) | 20 (17) | |

| Premature (<37 wk) | 21 (14) | 27 (23) | 0.06 |

| Noncardiac malformation | 11 (7) | 18 (15) | 0.04 |

| Genetic syndrome | 30 (20) | 47 (40) | 0.0003 |

Data are presented as N (%). LOS indicates length of stay.

As expected, prolonged initial LOS was associated with more than a 2‐fold increase in inpatient cost (P<0.0001) for the incident hospitalization (Table 3). It was also associated with a larger number of subsequent outpatient visits (median 29 versus 18, P<0.0001) as well as a higher total cost (median US$29 219 vs US$17 039, P=0.009) for those visits. Prolonged LOS during incident hospitalization was also associated with an increased likelihood of undergoing subsequent inpatient hospitalization(s) (P<0.0001). The median LOS for subsequent hospitalizations was also longer for those with prolonged initial LOS (7 days, IQR: 3, 13) compared with those with shorter LOS (4 days, IQR: 2, 9), but this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.06). The proportion of subjects undergoing catheterization appeared higher in the prolonged LOS group compared with those with shorter length of stay, but this also was not statistically significant (P=0.06). No differences were identified in number of repeat surgeries, ECGs, or echocardiograms between the 2 groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of Postoperative and Short‐Term Outcomes of Subjects With Prolonged and Shorter Total Hospital Length of Stay During Incident Hospitalization

| LOS ≤7 d (n=151) | LOS >7 d (n=118) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient costs for incident hospitalization ($) | 43 672 (38 480, 58 362) | 93 575 (71 738, 14 927) | <0.0001 |

| Total outpatient visits | |||

| Number | 18 (12, 29) | 29 (19, 48) | <0.0001 |

| Cost ($) | 17 039 (7496, 345 112) | 29 219 (12 469, 66 081) | 0.009 |

| Subsequent hospitalizations | <0.0001 | ||

| 0 | 118 (78) | 55 (46.61) | |

| 1 | 16 (11) | 29 (24.58) | |

| ≥2 | 17 (11) | 34 (28.81) | |

| Cumulative LOS, d | 4 (2, 9) | 7 (3, 13) | 0.06 |

| Cumulative cost ($) | 24 004 (9513, 81 649) | 27 852 (13 438, 79 648) | 0.60 |

| Subsequent cardiac operations | 0.20 | ||

| 0 | 115 (76) | 100 (83) | |

| 1 | 14 (9) | 9 (8) | |

| ≥2 | 23 (15) | 9 (8) | |

| Catheterizations | 0.13 | ||

| 0 | 131 (87) | 89 (75) | |

| 1 | 7 (5) | 13 (11) | |

| ≥2 | 13 (9) | 16 (14) | |

| ECGs | 3 (2, 5) | 4 (2, 6) | 0.07 |

| Echocardiograms | 4 (2, 5) | 4 (3, 6) | 0.13 |

Data are presented as N (%) or median (interquartile range). LOS indicates length of stay.

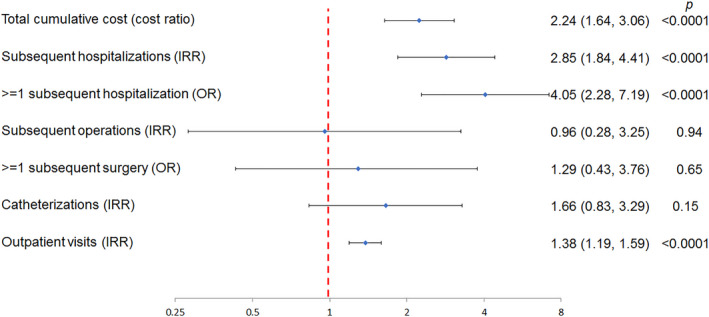

To adjust for measurable confounders, we conducted multivariable regression models to test whether prolonged LOS was associated with greater resource utilization after discharge (Figure). Prolonged initial LOS was independently associated with increased total cumulative costs (cost ratio 2.24, P<0.0001). Prolonged LOS was also associated with a greater number of subsequent hospitalizations (P<0.0001), increased risk of ≥1 hospitalization (P<0.0001), and greater total outpatient visits (P<0.0001). There was no significant association between prolonged LOS and the number of subsequent cardiac operations (P=0.94), risk of ≥1 subsequent cardiac operation (P=0.65), and number of cardiac catheterizations (P=0.15).

Figure 1. Association of prolonged LOS after operative correction and subsequent resource utilization in multivariable models.

This Forest plot depicts the results of a series of multivariable models evaluating the association between prolonged LOS after initial operative correction and subsequent measures of resource utilization. Point estimates for each model are depicted with a light blue diamond. Brackets represent 95% CIs. Point estimates and confidence intervals that are completely to the right of 1 (red dashed line) reflect increased resource utilization. Those that are completely to the left reflect decreased resource utilization. Each model is adjusted for sex, parental education, age at surgery, genetic syndrome, noncardiac congenital malformations, prematurity, and census region. The exception to this is the model of cost, which was not adjusted for census region. IRR indicates incidence rate ratio; LOS, length of stay; and OR, odds ratio.

Regional Variability in LOS and Resource Utilization

Observed differences in resource utilization were calculated (Table S2). Estimates adjusted for race and maternal education are summarized in Table 4. The LOS for the incident hospitalization, during which TOF operative correction was performed, was not significantly different across regions (P=0.19). However, costs were significantly different (P=0.002), with the lowest cost in the Northeast (US$55 684; 95% CI, 38 911–79 689) compared with ≈150% higher costs in the South (US$82 155; 95% CI, 64 100–105 296) and ≈180% higher costs in the West (US$98 679; 95% CI, 71 944–135 349).

Table 4.

Association Between Census Region and Resource Utilization Adjusted for Race and Maternal Education

| Northeast (N=28) | Midwest (N=68) | South (N=131) | West (N=42) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations for operative correction | |||||

| Total length of stay | 6.9 (4.8–9.8) | 8.9 (6.6–11.9) | 9.5 (7.5–12.1) | 8.1 (6.0–11.1) | 0.19 |

| Cost ($) | 55 684 (38 911–79 689) | 64 645 (47 990–87 081) | 82 155 (64 100–105 296) | 98 679 (71 944–135 349) | 0.002 |

| Subsequent hospitalizations | |||||

| Total length of stay | 3.8 (1.26–11.2) | 3.4 (1.5–7.4) | 10.8 (5.6–20.7) | 3.5 (1.5–7.8) | 0.0002 |

| Cost ($) | 15 116 (4719–48 417) | 16 648 (7053–39 300) | 37 086 (18 494–74 368) | 19 369 (8153–46 018) | 0.05 |

| Total outpatient visits | |||||

| N | 19.8 (14.6–26.8) | 16.7 (13.0–21.5) | 21.9 (17.7–27.1) | 17.0 (13.1–22.0) | 0.01 |

| Cost ($) | 7143 (5063–10 075) | 4453 (3353–5914) | 5834 (4615–7374) | 6122 (4556–8226) | 0.008 |

| Cardiac outpatient visits | |||||

| N | 6.7 (4.8–9.2) | 5.0 (3.8–6.6) | 6.3 (5.0–7.9) | 5.6 (4.2–7.5) | 0.10 |

| Cost ($) | 332 (197–589) | 287 (181–454) | 308 (214–561) | 340 (206–561) | 0.85 |

| Noncardiac outpatient visits | |||||

| N | 12.3 (8.3–18.1) | 10.7 (7.8–14.8) | 14.2 (10.9–18.5) | 10.5 (7.6–14.6) | 0.05 |

| Cost ($) | 6820 (4791–9709) | 4100 (3063–5489) | 5482 (4306–6979) | 5696 (4207–7712) | 0.005 |

| Emergency department visits | |||||

| N | 3.1 (1.6–5.9) | 3.0 (1.8–5.1) | 2.1 (1.3–3.2) | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | 0.03 |

| Cost ($) | 1159 (543–2477) | 1331 (707–2506) | 2402 (1332–4332) | 1102 (537–2264) | 0.01 |

Estimate (95% CI).

After discharge, there were also regional differences in resource utilization. The number of subsequent hospitalizations (P=0.0002) and their associated costs (P=0.05) were highest in the South relative to other regions, as were subsequent outpatient visits (P=0.01) and their associated costs (P=0.008). The number of emergency department visits was significantly higher in the Midwest and Northeast relative to the South and West (P=0.03). Costs associated with emergency department visits were highest in the South compared with other regions (P=0.01). This difference did not result in a significant difference in cumulative total costs for emergency department visits during follow‐up (P=0.28).

Discussion

The current multicenter cohort study demonstrates that there is significant resource utilization in the 2 years following operative correction of TOF. It also demonstrates that prolonged LOS after operative correction is associated with increased resource utilization even after discharge. It appears that morbidity in the perioperative period persists after hospital discharge. This highlights that conventional outcome measures following operative correction (ie, operative mortality) do not provide a complete depiction of the health of these patients. More optimistically, this suggests that strategies that reduce morbidity and LOS after operative correction may have durable benefits extending beyond hospital discharge. To our knowledge this is the first study to evaluate resource utilization and economic impact after hospital discharge in this population.

The low rate of mortality after operative correction of TOF1, 2, 3 may overestimate the health and well‐being of infants after discharge. Residual or iatrogenic anatomic lesions are relatively common as are postoperative adverse events.7, 8, 9 Data from the Society for Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgeons Database (reflecting the experience of the vast majority of US congenital cardiac surgery centers) demonstrate a discrepancy between the calculated standardized risk of mortality (STAT category 2/5) and standardized risk of morbidity (Morbidity category 3/5).2, 29 Tremendous variability in the cost of cardiac surgeries (including operative correction of TOF) has been demonstrated, which is driven, in part, by variation in the incidence of major adverse events.16, 30, 31 The risk of residual anatomic lesions and perioperative complications may vary more between hospitals than the uniform mortality rates suggest. This variability also represents an opportunity to improve both short‐ and long‐term outcomes in these patients.

LOS after operative correction can be prolonged by a multitude of complications, including post–cardiopulmonary bypass systemic inflammation, kidney injury, prolonged ventilation, cyanosis, residual lesions, and other postoperative cardiac and noncardiac complications.32 The current study cannot demonstrate that the events that affect LOS are the same as those influencing the observed increase in resource utilization, but the association is intriguing, especially since there is mounting evidence that the risk of prolonged LOS after operative correction for TOF may be modifiable. For example, patients with TOF undergoing neonatal intervention have a higher risk of residual anatomic lesion and longer LOS. Palliation with an operative shunt (instead of neonatal repair) is associated with reduced risk of operative mortality and major adverse events compared with single‐stage operative correction.25 Transcatheter (stent angioplasty of either the right ventricular outflow tract or patent ductus arteriosus) options for palliation are also available with at least equivalent risk of short‐term mortality33, 34 and some evidence of superior pulmonary artery growth than is the case with operative shunts.35, 36 The current data raise the possibility that reductions in short‐term morbidity that may be achieved with initial palliation might also be associated with reduced resource utilization in the medium term. The relative merits of these strategies could not be evaluated in this study, nor could their effect(s) on resource utilization. Future studies should evaluate the effects of these choices not only on perioperative outcomes, but also on medium‐term morbidity and resource utilization. It is important to measure the impact of these decisions beyond operative mortality, since early morbidity appears to persist into childhood.

It is not possible in this study to connect prolonged LOS and subsequent resource utilization with deficits in health and well‐being from the perspective of the patient. These measurements are not available in medical records, much less insurance claims data. Measurement of health‐related quality of life, functional status, and other patient‐reported outcomes would be helpful in understanding the degree to which differences in resource utilization reflect deficits in patient experience or reflect subclinical disease. This highlights the importance of including patient‐reported outcomes in future prospective studies.

Variation in resource utilization and cost provide evidence of potential to improve the value of care delivery (by reducing costs and improving outcomes). Understanding at what level these differences are manifest is important to direct efforts to improve the value of care delivered. Systematic geographic differences in the cost of congenital cardiac surgery have been demonstrated.37, 38 In hypoplastic left heart syndrome, specifically, significant regional variation in both LOS and costs have been demonstrated, though the explanation for these differences was not clear.39 There is also some evidence that practice patterns in other areas of congenital cardiology vary by geographic region.40, 41, 42 To our knowledge, regional variation in cost of care of children with TOF has not been evaluated previously. The current study did not demonstrate differences in LOS after operative correction, but did demonstrate significant differences in cost for that hospitalization and in both the amount and cost of subsequent inpatient and outpatient care. These associations were noted despite limitations, specifically, a relatively small sample size and unmeasured confounding because of data that are not recorded in the current database. Census regions are broad, including multiple regions and hospital settings. Further research using more granular geographic distinctions and hospital characteristics will be important to study this question. Some possible explanations include broad regional differences in wages and prices. Importantly, however, it is critical to disentangle differences in resource utilization caused by these changes (as well as those caused by differences in case‐mix), both of which are not generally modifiable, and those caused by differences in patterns of practice or quality of care/outcomes, which are more modifiable. Previous studies using hospital‐based administrative data have shown how regional wage–price indices can be used to “control” for these local variations to isolate variation in cost,14, 15, 16, 22, 28, 43, 44 but further work is necessary to effectively control for case‐mix and identify specific modifiable factors that influence resource utilization.

As noted, the study population has higher socioeconomic status than the population at large. It is not possible in this study to evaluate whether this has an effect on resource utilization. Though several studies have evaluated the association between insurance status and the risk of mortality after cardiac surgery, the results have been equivocal.14, 22, 38, 45, 46, 47, 48 There is evidence that lack of insurance is associated with increased risk of adverse outcome for neonates undergoing heart surgery during and after initial hospitalization.45 However, to our knowledge, there is no evidence that there is an analogous association between receipt of Medicaid and the risk of adverse events. Further studies incorporating recipients of both Medicaid and commercial insurances are necessary to address this question. At the same time, a critical part of any such study is to effectively evaluate how interconnected factors (insurance, race, ethnicity, income, and education) may contribute to these issues.

There were several other limitations to this study. Claims data provide a novel means of accessing longitudinal resource utilization data from a geographically representative cohort of children undergoing operative correction of TOF. However, not all clinically relevant data are available (eg, details of preoperative anatomy and any residual anatomic lesions postoperatively), which raise the possibility of unmeasured confounding. A specific concern noted previously is that mortality data are not available. As a result, bias because of the omission of the small percentage of patients who die within 2 years of their incident hospitalization could not be addressed. The data presented provide a best estimate of resource of patients surviving at least 2 years. For inpatient admissions, attributing costs to cardiac or noncardiac issues is also not possible, limiting the inferences possible in this study. Finally, over time as care of TOF continues to advance, differences in resource utilization may continue to evolve and deserve continued attention.

Conclusions

This study is the first to define medium‐term resource utilization in children undergoing operative correction of TOF. It demonstrates that resource utilization is increased over 2 years among patients who have prolonged LOS during their initial hospitalization. Future research should focus on determining whether higher resource utilization is also associated with decreased health and well‐being, and whether strategies to reduce morbidity in the incident hospitalization also reduce resource utilization during subsequent follow‐up. Together this would both improve outcomes for patients with TOF and deliver higher value care.

Sources of Funding

Dr O'Byrne (K23 HL130420‐01), Dr Savla (T32 HL007915), and Dr Mercer Rosa (K01 HL125521) all receive funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The funding agencies had no role in the planning or execution of the study, nor did they edit the manuscript as presented. The manuscript represents the opinions of the authors alone.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S2

Acknowledgments

This project utilized resources from the Cardiac Center Clinical Research Core at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016581 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016581.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

References

- 1. Smith CA, McCracken C, Thomas AS, Spector LG, St Louis JD, Oster ME, Moller JH, Kochilas L. Long‐term outcomes of tetralogy of Fallot: a study from the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Brien SM, Clarke DR, Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Lacour‐Gayet FG, Pizarro C, Welke KF, Maruszewski B, Tobota Z, Miller WJ, et al. An empirically based tool for analyzing mortality associated with congenital heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:1139–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luijten LWG, van den Bosch E, Duppen N, Tanke R, Roos‐Hesselink J, Nijveld A, van Dijk A, Bogers AJJC, van Domburg R, Helbing WA. Long‐term outcomes of transatrial‐transpulmonary repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bacha EA, Scheule AM, Zurakowski D, Erickson LC, Hung J, Lang P, Mayer JE, del Nido PJ, Jonas RA. Long‐term results after early primary repair of tetralogy of Fallot. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sen DG, Najjar M, Yimaz B, Levasseur SM, Kalessan B, Quaegebeur JM, Bacha EA. Aiming to preserve pulmonary valve function in tetralogy of Fallot repair: comparing a new approach to traditional management. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;37:818–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hickey E, Pham‐Hung E, Halvorsen F, Gritti M, Duong A, Wilder T, Caldarone CA, Redington A, Van Arsdell G. Annulus‐sparing tetralogy of Fallot repair: low risk and benefits to right ventricular geometry. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balasubramanya S, Zurakowski D, Borisuk M, Kaza AK, Emani SM, Del Nido PJ, Baird CW. Right ventricular outflow tract reintervention after primary tetralogy of Fallot repair in neonates and young infants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155:726–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mouws EMJP, de Groot NMS, van de Woestijne PC, de Jong PL, Helbing WA, van Beynum IM, Bogers AJJC. Tetralogy of Fallot in the current era. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;31:496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nathan M, Marshall AC, Kerstein J, Liu H, Fynn‐Thompson F, Baird CW, Mayer JE, Pigula FA, Del Nido PJ, Emani S. Technical performance score as predictor for post‐discharge reintervention in valve‐sparing tetralogy of Fallot repair. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;26:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Byrne ML, Mercer‐Rosa L, Zhao H, Zhang X, Yang W, Tanel RE, Marino BS, Cassedy A, Fogel MA, Rychik J, et al. Morbidity in children and adolescents after surgical correction of interrupted aortic arch. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;35:386–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O'Byrne ML, Mercer‐Rosa L, Zhao H, Zhang X, Yang W, Cassedy A, Fogel MA, Rychik J, Tanel RE, Marino BS, et al. Morbidity in children and adolescents after surgical correction of truncus arteriosus communis. Am Heart J. 2013;166:512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldmuntz E, Cassedy A, Mercer‐Rosa L, Fogel MA, Paridon SM, Marino BS. Exercise performance and 22q11.2 deletion status affect quality of life in tetralogy of Fallot. J Pediatr. 2017;189:162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Byrne ML, Gillespie MJ, Shinohara RT, Dori Y, Rome JJ, Glatz AC. Cost comparison of transcatheter and operative closures of ostium secundum atrial septal defects. Am Heart J. 2015;169(727–735):e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Byrne ML, Gillespie MJ, Shinohara RT, Dori Y, Rome JJ, Glatz AC. Cost comparison of transcatheter and operative pulmonary valve replacement (from the Pediatric Health Information Systems Database). Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Faerber JA, Seshadri R, Millenson ME, Mi L, Shinohara RT, Dori Y, Gillespie MJ, Rome JJ, et al. Interhospital variation in the costs of pediatric/congenital cardiac catheterization laboratory procedures: analysis of data from the Pediatric Health Information Systems Database. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011543 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pasquali SK, Sun JL, d'Almada P, Jaquiss RDB, Lodge AJ, Miller N, Kemper AR, Lannon CM, Li JS. Center variation in hospital costs for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:306–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lodin D, Mavrothalassitis O, Haberer K, Sunderji S, Quek RGW, Peyvandi S, Moon‐Grady A, Karamlou T. Revisiting the utility of technical performance scores following tetralogy of Fallot repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:585–595.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ungerleider RM, Bengur AR, Kessenich AL, Liekweg RJ, Hart EM, Rice BA, Miller CE, Lockwood NW, Knauss SA, Jaggers J, et al. Risk factors for higher cost in congenital heart operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:44–48, discussion 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Willems R, Tack P, François K, Annemans L. Direct medical costs of pediatric congenital heart disease surgery in a Belgian University Hospital. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2019;10:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O'Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Mercer‐Rosa L, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, Goldmuntz E, Kawut S, Rome JJ. Trends in pulmonary valve replacement in children and adults with tetralogy of Fallot. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:118–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Byrne ML, Millenson ME, Grady CB, Huang J, Bamat NA, Munson DA, Song L, Dori Y, Gillespie MJ, Rome JJ, et al. Trends in transcatheter and operative closure of patent ductus arteriosus in neonatal intensive care units. Am Heart J. 2019;217:121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Song L, Griffis HM, Millenson ME, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, DeWitt AG, Mascio CE, Rome JJ. Association between variation in preoperative care before arterial switch operation and outcomes in patients with transposition of the great arteries. Circulation. 2018;138:2119–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O'Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Shinohara RT, Jayaram N, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, Rome JJ, Kawut S. Effect of center catheterization volume on risk of catastrophic adverse event after cardiac catheterization in children. Am Heart J. 2015;169:823–832.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Byrne ML, Glatz AC, Hanna BD, Shinohara RT, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, Rome JJ, Kawut SM. Predictors of catastrophic adverse outcomes in children with pulmonary hypertension undergoing cardiac catheterization: a multi‐institutional analysis from the Pediatric Health Information Systems Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1261–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Savla JJ, Faerber JA, Huang Y‐SV, Zaoutis T, Goldmuntz E, Kawut SM, Mercer‐Rosa L. 2‐year outcomes after complete or staged procedure for tetralogy of Fallot in neonates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1570–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang S, Wen L, Tao S, Gu J, Han J, Yao J, Wang J. Impact of timing on in‐patient outcomes of complete repair of tetralogy of Fallot in infancy: an analysis of the United States National Inpatient 2005–2011 database. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19:46–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ. 2005;24:465–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O'Byrne ML, Shinohara RT, Grant EK, Kanter JP, Gillespie MJ, Dori Y, Rome JJ, Glatz AC. Increasing propensity to pursue operative closure of atrial septal defects following changes in the instructions for use of the Amplatzer Septal Occluder device: an observational study using data from the Pediatric Health Information Systems database. Am Heart J. 2017;192:85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jacobs ML, O'Brien SM, Jacobs JP, Mavroudis C, Lacour‐Gayet F, Pasquali SK, Welke K, Pizarro C, Tsai F, Clarke DR. An empirically based tool for analyzing morbidity associated with operations for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1046–1057.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pasquali SK, Li JS, Burstein DS, Sheng S, O'Brien SM, Jacobs ML, Jaquiss RDB, Peterson ED, Gaynor JW, Jacobs JP. Association of center volume with mortality and complications in pediatric heart surgery. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e370–e376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jacobs JP, O'Brien SM, Pasquali SK, Jacobs ML, Lacour‐Gayet FG, Tchervenkov CI, Austin EH, Pizarro C, Pourmoghadam KK, Scholl FG, et al. Variation in outcomes for benchmark operations: an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:2184–2191, discussion 2191–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mercer‐Rosa L, Elci OU, DeCost G, Woyciechowski S, Edman SM, Ravishankar C, Mascio CE, Kawut SM, Goldmuntz E. Predictors of length of hospital stay after complete repair for tetralogy of Fallot: a prospective cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008719 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bentham JR, Zava NK, Harrison WJ, Shauq A, Kalantre A, Derrick G, Chen RH, Dhillon R, Taliotis D, Kang SL, et al. Duct stenting versus modified Blalock‐Taussig shunt in neonates with duct‐dependent pulmonary blood flow: associations with clinical outcomes in a multicenter national study. Circulation. 2018;137:581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Glatz AC, Petit CJ, Goldstein BH, Kelleman MS, McCracken CE, McDonnell A, Buckey T, Mascio CE, Shashidharan S, Ligon RA, et al. Comparison between patent ductus arteriosus stent and modified Blalock‐Taussig shunt as palliation for infants with ductal‐dependent pulmonary blood flow: insights from the Congenital Catheterization Research Collaborative. Circulation. 2018;137:589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Quandt D, Ramchandani B, Stickley J, Mehta C, Bhole V, Barron DJ, Stumper O. Stenting of the right ventricular outflow tract promotes better pulmonary arterial growth compared with modified Blalock‐Taussig shunt palliation in tetralogy of Fallot‐type lesions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1774–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santoro G, Capozzi G, Caianiello G, Palladino MT, Marrone C, Farina G, Russo MG, Calabrò R. Pulmonary artery growth after palliation of congenital heart disease with duct‐dependent pulmonary circulation: arterial duct stenting versus surgical shunt. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2180–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Simeone RM, Oster ME, Cassell CH, Armour BS, Gray DT, Honein MA. Pediatric inpatient hospital resource use for congenital heart defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2014;100:934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Connor JA, Gauvreau K, Jenkins KJ. Factors associated with increased resource utilization for congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2005;116:689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Essaid L, Strassle PD, Jernigan EG, Nelson JS. Regional differences in cost and length of stay in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol. 2018;39:1229–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Quartermain MD, Pasquali SK, Hill KD, Goldberg DJ, Huhta JC, Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Kim S, Ungerleider RM. Variation in prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease in infants. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e378–e385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. O'Byrne ML, Kennedy KF, Rome JJ, Glatz AC. Variation in practice patterns in device closure of atrial septal defects and patent ductus arteriosus: an analysis of data from the IMproving Pediatric and Adult Congenital Treatment (IMPACT) registry. Am Heart J. 2018;196:119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Glatz AC, Kennedy KF, Rome JJ, O'Byrne ML. Variations in practice patterns and consistency with published guidelines for balloon aortic and pulmonary valvuloplasty. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pasquali SK, Jacobs ML, He X, Shah SS, Peterson ED, Hall M, Gaynor JW, Hill KD, Mayer JE, Jacobs JP, et al. Variation in congenital heart surgery costs across hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e553–e560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pasquali SK, Jacobs JP, Bove EL, Gaynor JW, He X, Gaies MG, Hirsch‐Romano JC, Mayer JE, Peterson ED, Pinto NM, et al. Quality‐cost relationship in congenital heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1416–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kucik JE, Cassell CH, Alverson CJ, Donohue P, Tanner JP, Minkovitz CS, Correia J, Burke T, Kirby RS. Role of health insurance on the survival of infants with congenital heart defects. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e62–e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Oster ME, Strickland MJ, Mahle WT. Racial and ethnic disparities in post‐operative mortality following congenital heart surgery. J Pediatr. 2011;159:222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gonzalez PC, Gauvreau K, Demone JA, Piercey GE, Jenkins KJ. Regional racial and ethnic differences in mortality for congenital heart surgery in children may reflect unequal access to care. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chan T, Pinto NM, Bratton SL. Racial and insurance disparities in hospital mortality for children undergoing congenital heart surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33:1026–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S2