Abstract

Background

Multidimensional solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) spectroscopy has emerged as an indispensable technique for resolving polymer structure and intermolecular packing in primary and secondary plant cell walls. Isotope (13C) enrichment provides feasible sensitivity for measuring 2D/3D correlation spectra, but this time-consuming procedure and its associated expenses have restricted the application of ssNMR in lignocellulose analysis.

Results

Here, we present a method that relies on the sensitivity-enhancing technique Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (DNP) to eliminate the need for 13C-labeling. With a 26-fold sensitivity enhancement, a series of 2D 13C–13C correlation spectra were successfully collected using the unlabeled stems of wild-type Oryza sativa (rice). The atomic resolution allows us to observe a large number of intramolecular cross peaks for fully revealing the polymorphic structure of cellulose and xylan. NMR relaxation and dipolar order parameters further suggest a sophisticated change of molecular motions in a ctl1 ctl2 double mutant: both cellulose and xylan have become more dynamic on the nanosecond and microsecond timescale, but the motional amplitudes are uniformly small for both polysaccharides.

Conclusions

By skipping isotopic labeling, the DNP strategy demonstrated here is universally extendable to all lignocellulose materials. This time-efficient method has landed the technical foundation for understanding polysaccharide structure and cell wall assembly in a large variety of plant tissues and species.

Keywords: Solid-state NMR, Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP), Polysaccharide structure, Cellulose, Xylan, Plant cell wall, Natural isotopic abundance

Background

The past decade has witnessed the rapid advances in multidimensional solid-state NMR (ssNMR) capabilities that have enabled high-resolution characterization of intact plant cell walls. This spectroscopic method provides a wealth of atomic-level information on the conformational structure of polysaccharides, covalent linkage patterns of matrix polysaccharides, dynamical profile and water contact, as well as cellulose-matrix packing on the subnanometer scale [1]. With a rapidly expanding territory, from eudicotyledons (Arabidopsis thaliana) to commelinid monocotyledons (Zea mays, Brachypodium distachyon, etc.) [2–5], from primary to secondary cell walls [6–10], and from plants to algal and fungal species [11–13], ssNMR has progressively evolved into a vital tool for characterizing carbohydrate-rich biomaterials. The molecular information of cell wall architecture can serve as the structural basis for improving the current technologies of biofuel production using lignocellulosic biomass [14].

Enriching the cell walls with NMR-active isotopes (such as 13C and 15N) is a prerequisite for measuring two- and three-dimensional (2D/3D) correlation experiments, which provides the spectral resolution required for resolving numerous carbon and nitrogen sites in cell wall polymers. Two strategies can be employed: plants can be grown in the dark, using a medium-containing 13C-labeled glucose [2]; otherwise, 13CO2 can be continuously supplied to the plants grown in a day–night cycle [4, 15]. Depending on the developmental stage and the tissue of interest, labeling can be time-consuming and costly. In vitro replication procedures also weaken the merit of ssNMR as an analytical technique targeting natural tissues.

The recent development of Magic-Angle Spinning Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (MAS-DNP) methods has presented a unique opportunity for circumventing these drawbacks [16–19]. MAS-DNP enhances NMR sensitivity by tens to hundreds of folds, which allows us to skip isotope enrichment and use unlabeled samples to measure 2D 13C–13C/15 N correlation spectra for high-resolution structural characterization [20–22]. Regarding the plant biomass, three exploratory studies have been conducted to reveal the restructuring effect of ball milling on cotton cellulose [23], the alternation of xylan conformations induced by genetic mutations of rice [24], and the compositional changes of lignin in high-S and low-S poplar [25]. With the rapid development of DNP instrumentation [26–29] and radical design [30–33], this is certainly a direction of great potential but not yet explicitly explored for plant materials.

This methodology article aims at establishing a universally applicable toolbox for characterizing polymer structure and assembly in unlabeled plant biomass. This is achieved by combining a series of DNP-enabled experiments that probe the composition and conformational structure of polymers with conventional ssNMR measurements that examine the rate and amplitudes of molecular motions. Implementation of this method will expand the ssNMR capabilities and enable high-resolution investigations of unlabeled cell walls, which, at least in part, provides a replacement and upgrade to the conventional methods that rely on 13C-enriched materials. Most of the structural aspects previously investigated using 13C-enriched samples, such as the composition, conformation, packing, and motion of cell wall polymers, can be studied using unlabeled materials via a blend of MAS-ssNMR and MAS-DNP methods (Table 1). This technical advance will eliminate the threshold that has long been impeding lignocellulose characterization, which will immediately benefit the research communities of plant biology, biomaterials, and bioenergy.

Table 1.

Capabilities of solid-state NMR and DNP in biomass research

| Samples and techniques | Polymer composition | Structural polymorph | Intermolecular packing | Molecular motion | Water contact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled; MAS-ssNMR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Unlabeled; MAS-ssNMR | In part | No | No | In part | In part |

| Unlabeled; MAS-DNP | Yes | Yes | In part | Noa | Noa |

Technical aspects are categorized as being fully capable (Yes), partially limited by insufficient resolution or sensitivity (In part), and infeasible or unsuitable (No)

aMAS-DNP is conducted at cryogenic temperature (~ 100 K); therefore, it is unsuitable for investigating molecular motions. It is also better to investigate polymer–water contacts at room temperature

Results

Sensitivity Enhancement by MAS-DNP

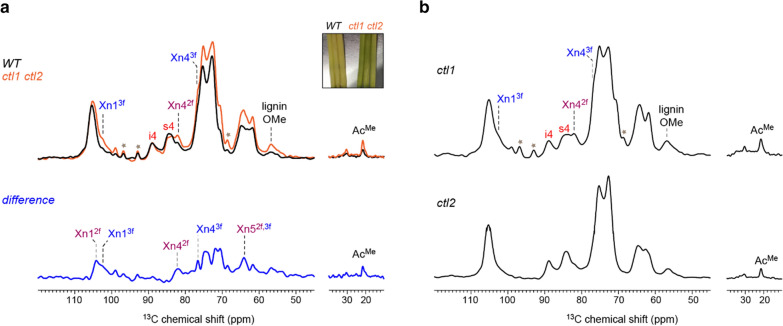

For decades, one-dimensional (1D) 13C spectra have been conducted using unlabeled materials to analyze the structure and composition of polysaccharides at natural isotope abundance (1.1% for 13C) [34–37]. Figure 1 shows the 1D quantitative spectra of four rice samples including the wild-type (WT) stems, two single mutants, which are ctl1 (harboring an identical mutation of brittle culm 15) and ctl2, as well as a double mutant ctl1 ctl2. These mutations happen to rice CHITINASE-LIKE1 (CTL1) and its homolog CTL2, which have been suggested a role in controlling cellulose biosynthesis, thereby affecting wall integrity [38–41], as ctl1 and ctl1 ctl2 plants exhibited obvious brittleness phenotypes. Quantitative detection of all carbons is achieved using a recently developed pulse sequence, MultiCP, which counts on 1H T1 relaxation to repeatedly restore 1H magnetization between the many CP blocks included in each individual scan of the experiment [42–44]. The rice stems are collected from the field, without any dissolution procedures or chemical digestions; therefore, the cell walls being analyzed are still native and intact. Various peaks of cellulose (interior chains: i; surface chains: s) and xylan (Xn) have been observed (Fig. 1a), indicating the predominance of secondary cell wall components in these mature stems.

Fig. 1.

1D 13C spectra of unlabeled cell walls of wild-type rice and mutants at room-temperature. a 1D 13C MultiCP spectra of wild-type sample (WT; black) and ctl1 ctl2 double mutant (orange) yielding quantitative detection of all molecules. Abbreviations of carbohydrate assignments are shown in Fig. 4, except for xylan acetyl group (Ac). The difference spectrum is obtained by subtraction of the two parent spectra after normalization by i4 peaks. The difference spectrum mainly contains xylan signals, revealing the higher hemicellulose content in ctl1 ctl2 mutant. The insert picture on the right top side is the representative photo of the two kinds of rice stems. b 1D 13C MultiCP spectra of ctl1 and ctl2 single mutants. The spectral pattern of ctl1 mutant is similar to that of the ctl1 ctl2 double mutant while ctl2 is closer to the WT sample

There are ongoing debates regarding the nature of 89 and 84 ppm cellulose peaks. Recent high-resolution ssNMR studies support that these signals originate from the interior and surface glucan chains in cellulose microfibrils rather than the longitudinally distributed domains of crystalline and disordered domains [1]. The cellulose microfibrils in intact plant cell walls were found to adapt a unique structure that differs from the model Iα and Iβ allomorphs [45, 46], which were later found to only exist in highly crystalline cellulose with large crystallites, for example, the cotton balls [23]. The surface residues have extensive interactions with water molecules and matrix polymers and adapt a gauche-trans conformation, while the interior chains adapt trans-gauche conformation and exhibit substantially weaker contacts with other molecules [46–48].

Different from the WT stems, the double mutant has a higher amount of methyl ether (-OMe) groups, which is a chemical substitution frequently occurring in lignin. The ctl1 ctl2 sample shows a higher peak at 56 ppm for methyl ether groups (Fig. 1a) but comparable intensities for aromatic carbons (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). This observation indicates that the ctl1 ctl2 sample, when compared with the WT stems, has a higher fraction of the guaiacyl (G) and syringyl (S) units that contain methyl ether groups, rather than the p-hydroxyphenyl (H) unit that does not contain methyl ether group. The ctl1 ctl2 sample has shown stronger xylan peaks, for example, the carbon 1 of threefold xylan at 102 ppm (Xn13f), the carbon 4 of twofold xylan at 82 ppm (Xn42f), and the methyl carbon of acetyl group at 21 ppm (AcMe). Subtraction of the WT and ctl1 ctl2 spectra has generated a difference spectrum, which contains well-resolved signals from twofold and threefold xylan, revealing a relatively higher amount of xylan (with normalization to the amount of interior cellulose) in the double mutant. The spectral patterns of the two single mutants are intriguing: the spectrum of ctl1 resembles that of the double mutant, while ctl2 is similar to the WT sample (Fig. 1b). Combined with the cell wall defects detected in bc15 [41], the results have suggested a stronger role of the ctl1 mutation in modulating cell wall composition and structure. While useful information can be obtained by following this conventional 1D analysis, only a few carbon sites can be resolved. This resolution issue can be partially alleviated by spectral subtraction, but significant improvement is still needed for characterizing these polysaccharides and cell walls.

The rice material is then impregnated in a solvent mixture of 13C-depleted, d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O, which contains 10 mM of a stable biradical AMUPol [30]. 13C-depletion of glycerol is a necessity for investigating unlabeled samples where both biomolecules and glycerol are at natural 13C abundance: it can effectively eliminate the glycerol signals that overlap with the carbohydrate signals. This protocol, when compared with a matrix-free method that was recently applied to cotton [23, 49, 50], better retains polymer hydration in cell walls. The payoff is a moderate decline in the signal-to-noise ratios, because the solvent occupies some volume in the MAS rotor, which will otherwise be filled with more biomolecules.

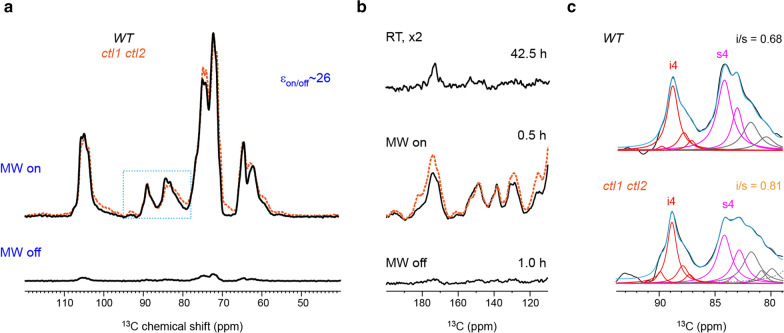

Under microwave irradiation, polarization of the electrons in the biradical will thereafter be transferred to 1H spins in unlabeled rice stem, and then to the natural-abundance 13C for detection. The sensitivity enhancement (εon/off) is 26-fold for the wild-type sample and 22-fold for the ctl1 ctl2 double mutant (Fig. 2a, Additional file 1: Fig. S2a), which respectively shortens the experimental time by factors 676 and 484 times. The same gain of sensitivity also occurs to lignin. We have observed strong signals of the aromatic carbons (120–160 ppm) within a short time of 0.5 h (Fig. 2b). These signals, however, are invisible in the conventional ssNMR even after 42.5 h of measurements at room temperature.

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity enhancement from DNP. a DNP enhances the NMR sensitivity by 26-fold on the wild-type sample. This value is obtained by quantifying the intensity ratio between the spectra collected with microwave on (MW on) and microwave off (MW off). The DNP-enhanced spectrum of ctl1 ctl2 (orange dashline) is compared with the wild-type (WT) sample. b Lignin region of the room-temperature spectrum (RT; top), DNP-enhanced spectrum (MW on; middle), and non-DNP spectrum (MW off; bottom). The experimental time is labeled for each panel. DNP significantly saves experimental time and enhances NMR sensitivity. c, Spectral deconvolution of the interior cellulose carbon 4 (i4) and surface cellulose carbon 4 (s4) region (dashline square in panel a) reveals the crystallinity change in rice cellulose. The experimentally measured spectra (black) are overlaid with the simulated spectra (blue), with the deconvoluted peaks underlying the spectral envelope. The interior-to-surface (i/s) ratio of cellulose is quantified for both samples, which has shown an increase in cellulose crystallinity in the ctl1 ctl2 mutant. The fit parameters are listed in Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2

The DNP experiment preferentially detects the molecules with a highly ordered structure, for example, the cellulose microfibrils in plants (Additional file 1: Fig. S3) and the highly microcrystalline chitin in fungi [10, 12]. At the cryogenic temperature (~ 100 K) of MAS-DNP, the conformational distribution of mobile molecules, such as xylan and small molecules, will be fully trapped, resulting in broader lines and lower intensity. Recently, concerns have also been raised regarding the radical distribution in cell walls, which were supposed to induce a biased detection of molecules in spatial proximity to the radicals. This argument is invalid, because all molecules within tens of nanometer to a radical can be efficiently polarized via 1H–1H spin diffusion, which is due to the inherently long relaxation times of the 1Hs in cell walls [51]. This mechanism ensures a homogenous polarization of all molecules throughout the cell wall, which has been confirmed by the consistent spectral envelopes with and without microwave irradiation (Additional file 1: Fig. S4).

In addition, the crystallinity of cellulose becomes higher in the double mutant. Cellulose crystallinity is evaluated using the intensity ratio between the carbon 4 of interior glucan chains (i4; 89 ppm) and the carbon 4 of surface glucan chains (s4; 84 ppm) in cellulose. When normalized by the i4 signal, the s4 peak is lower in the double mutant than in the WT sample as consistently observed at room temperature (Fig. 1a) and under the DNP condition (Fig. 2a). Spectral deconvolution allows us to resolve the underlying resonances and quantify the interior-to-surface (i/s) ratios, which are 0.68 for WT and 0.81 for ctl1 ctl2 (Fig. 2c, Additional file 1: Fig. S5, Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2). The higher cellulose crystallinity in the double mutant may originate from an increased degree of cellulose bundling in the cell wall. The observation here actually counters previous X-ray analysis of Arabidopsis, which has shown reduced content of crystalline cellulose in a ctl1 ctl2 mutant [40]. The discrepancy is attributed to different plant species being studied as our unpublished X-ray diffraction data on the same rice stems have observed a higher relative crystallinity index (RCI) for cellulose in the double mutant, which has confirmed the NMR observation.

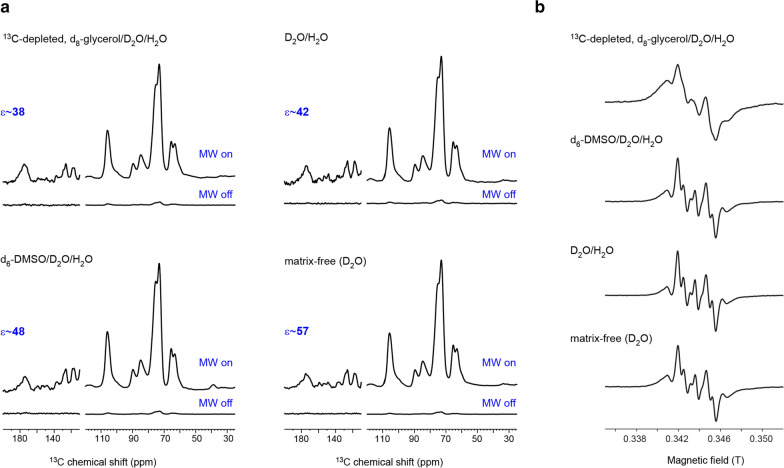

During the sample preparation, the radical usually is dissolved in a solvent mixture at room temperature to ensure uniform distribution. To examine how the DNP matrix affects the sensitivity enhancement, multiple DNP enhancement experiments with four major matrix protocols (glycerol/D2O/H2O, DMSO/D2O/H2O, D2O/H2O, and a matrix-free protocol) are measured. The results are shown in Fig. 3a and summarized in Table 2. The spectra of ctl1 sample in the four solvent mixtures in Fig. 3a are highly similar, indicating that the matrix solvents have no major influence on the structure of biomolecules. Meanwhile, the matrix-free (with a limited amount of D2O) protocol [49, 50] gives the largest enhancement factor ε of 57, which means a time-saving of 3249-fold. This matrix-free protocol efficiently avoids the enhancement reduction caused by aggregation and phase separation of glass-forming solvents at 100 K.

Fig. 3.

The influence of various matrices of AMUPol radical on DNP sensitivity enhancement. a DNP enhancement factors on the unlabeled ctl1 sample are 38, 48, 42, and 57, respectively, when preparing the sample with 13C-depleted, d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (60/30/10 vol%), d6-DMSO/D2O/H2O (80/10/10 vol%), or D2O/H2O (75/25 vol%) solvents. For the matrix-free protocol, there is no bulk solution and only a few mL of D2O is present in the final sample. The detailed experimental parameters are listed in Table 2. b Room-temperature EPR spectra of AMUPol at 9.6 GHz in the above four solvents

Table 2.

Experimental parameters of DNP enhancement

| Figure number | Sample | Matrix and protocol | Rotor type | Year | Build-up time (s) | MAS (kHz) | εon/off |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 2a | WT | 13C-depleted, d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (60/30/10 vol%) | ZrO2 thin-wall rotor | 2018 | 2.77 | 10 | 26 |

| Additional file 1: Fig.S2a | ctl1 ctl2 | 13C-depleted, d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (60/30/10 vol%) | 2.59 | 10 | 22 | ||

| Figure 3a | ctl1 | 13C-depleted, d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (60/30/10 vol%) | Sapphire rotor | 2020 | 2.64 | 8 | 38 |

| Figure 3a | ctl1 | d6-DMSO/D2O/H2O (80/10/10 vol%) | 1.96 | 8 | 48 | ||

| Figure 3a | ctl1 | D2O/H2O(75/25 vol%) | – | 8 | 42 | ||

| Figure 3a | ctl1 | D2O (matrix-free) | 1.67 | 8 | 57 | ||

| Additional file 1: Fig. S2b | ctl1 ctl2 | D2O (matrix-free) | 1.40 | 10.5 | 44 |

The related figure position of each matrix protocol is given. Unidentified (–). The samples freshly measured in 2020 give high sensitivity enhancement of 38–57 fold due to the use of sapphire rotor, optimization of sample preparation, and the improvement of the DNP instruments

Besides, the second batch of samples packed in sapphire rotors and measured in 2020 have exhibited better sensitivity enhancement than the first batch of samples packed in ZrO2 thin-wall rotor in 2018. The reason for the improvement is multifaceted: the loss of microwave is less in the sapphire material than the ZrO2 material; our preparation protocol, in particular, the procedure for mixing radicals with biomaterials, has been optimized [52]; and the improved performance of the MAS-DNP instrument during the past 2 years. The continuous-wave (CW) electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of AMUPol biradical at 9.6 GHz in the four solutions are shown in Fig. 3b. AMUPol is mostly “free” in the solution. The four spectra are similar except for the glycerol-based mixture, which is highly viscous; therefore, the tumbling rate is slow and a true liquid-state EPR spectrum cannot be observed.

2D 13C-13C correlation spectra of unlabeled cell walls

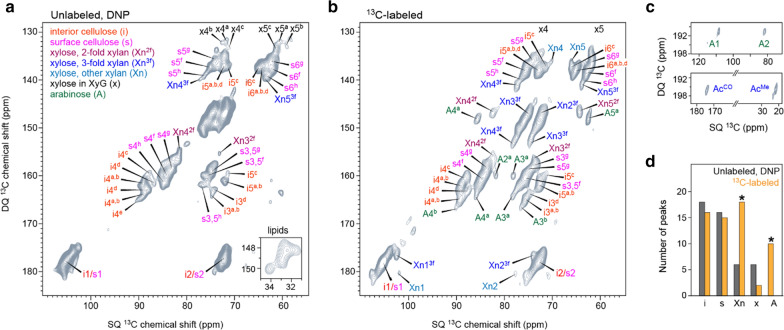

Benefiting from the substantial gain of NMR sensitivity, we have successfully collected a 2D 13C–13C J-INADEQUATE spectrum [53, 54] using unlabeled stems of WT rice (Fig. 4a). Because of the low abundance (1.1%) of 13C in nature and the even lower probability (0.01%) for observing a cross peak between two carbons, such a 2D experiment has long been deemed impossible, but can be finished now within 35 h using the rice stems.

Fig. 4.

DNP enables 2D correlation spectroscopy using unlabeled and native cell walls. a 2D 13C–13C INADEQUATE spectrum of unlabeled WT rice collected on a 600 MHz/395 GHz DNP system. DNP effectively detects and resolves the signals from cellulose and hemicellulose at natural isotope abundance. Superscripts are used to denote the eight types of glucose units in interior and surface cellulose and the twofold and threefold conformations in xylan. Inset shows the lipid signals that are folded in the indirect dimension. b 2D 13C–13C INADEQUATE spectrum of 13C-labeled WT rice stems measured on a 400 MHz NMR spectrometer. The spectral pattern is comparable to the DNP-assisted natural-abundance spectrum in a. c Arabinose and acetyl signals are detectable using 13C-labeled samples, but become invisible in the DNP spectrum of unlabeled materials. d Number of peaks detected using labeled and unlabeled samples, which are tabulated in Additional file 1: Table S3. Asterisks indicate the components that are poorly detected using natural-abundance DNP

We have observed eight types of glucose units in cellulose: types a–e for the glucan chains embedded in the core of microfibrils and types f–h for those exposed on the surface. Their 13C chemical shifts are consistent with those observed in Arabidopsis, Zea mays, and Brachypodium distachyon, revealing the polymorphic nature of cellulose structure [45]. Hemicellulose shows weak signals, for example, the carbon 4 and carbon 5 in threefold xylan (Xn43f and Xn53f) as well as the carbon 3 and carbon 4 in twofold conformers (Xn32f and Xn42f). In addition, the α-xylose (x) of xyloglucan also exhibits some weak signals, indicative of a small portion of primary cell walls. Besides polysaccharides, we have also observed some self-correlation cross peak of the CH2 acyl chains in lipid polymers. Therefore, the remarkable resolution of the DNP-enabled 2D spectrum allows us to unambiguously resolve many carbon sites in cellulose, matrix polysaccharides, and lipids, which is otherwise impossible.

The validity of natural-abundance MAS-DNP is confirmed by the consistent spectral pattern between unlabeled (Fig. 4a) and 13C-labeled (Fig. 4b) rice stems. In addition, a few peaks are omitted in the natural-abundance DNP spectrum. These signals are primarily from the arabinose residues of xylan sidechains, some carbon sites in twofold, threefold, and mixed forms of xylan backbones, as well as the acetyl groups (Fig. 4c). Peak counting has confirmed MAS-DNP’s preferential detection of ordered molecules: we can effectively detect all cellulose carbons and part of xylan backbones, but not for arabinose sidechains (Fig. 4d). These mobile molecules, when trapped at 100 K, bear a wide distribution of conformations, which has broadened out their signals.

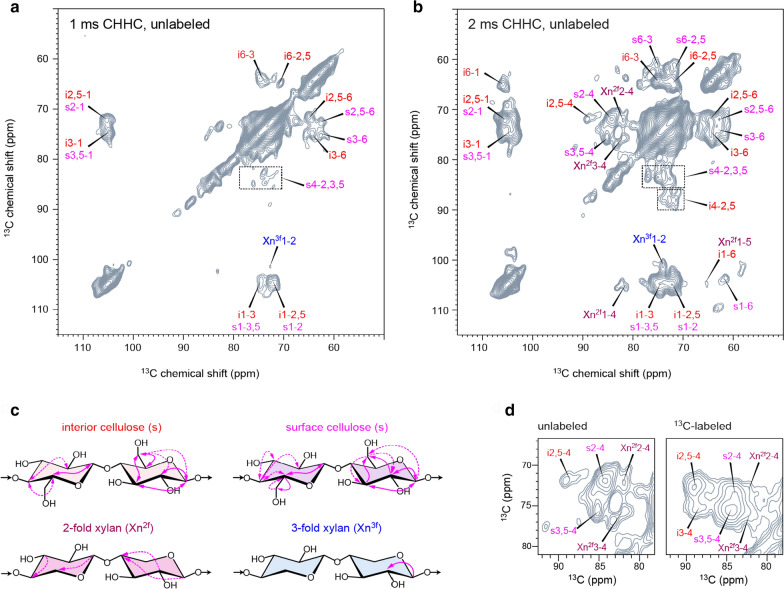

While the J-INADEQUATE experiment only probes through-bond correlations, we have also performed a CHHC experiment to detect long-range and through-space correlations (Fig. 5a, b). The CHHC sequence relies on 1H–1H spin diffusion to transfer polarization, which is followed by cross-polarization (CP) from 1H to 13C for site-specific detection [55]. The Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) linewidths are around 3 ppm and the representative signal-to-noise ratios are ranging from 4 to 41 (Additional file 1: Fig. S6). The off-diagonal cross peaks are mostly intramolecular correlations within cellulose, for example, the i6-3 cross peak (at 65, 75 ppm) and the s3-6 cross peak (at 75, 62 ppm) in the 1-ms CHHC spectrum. Elongating the mixing time to 2 ms allows us to extend the reach; therefore, many additional cross peaks now become observable (Fig. 5b). The new signals are primarily from cellulose, such as the i6-1 cross peak (at 65, 105 ppm) and i2,5–4 cross peak (at 72, 89 ppm). We have also observed some signature signals of xylan, for example, Xn2f2-4 (at 73, 82 ppm) and Xn2f3-4 (at 78, 82 ppm).

Fig. 5.

DNP-enabled 2D CHHC spectra of unlabeled rice stems. The CHHC spectra of unlabeled WT sample are measured with a 1 ms and b 2 ms 1H-1H mixing times. c Summary of through-space intramolecular cross peaks. Solid lines denote the cross peaks observable in both 1 and 2 ms spectra, while dash lines indicate the cross peaks that are observed only in the 2-ms spectrum. Arrows are used to indicate whether the cross peaks are bidirectional (e.g., C1-to-C2 and C2-to-C1 cross peaks) or unidirectional (e.g., only from C1 to C2). d Comparison of polysaccharide signals in the 2-ms CHHC spectrum of the unlabeled sample and a 5-ms PDSD spectrum of 13C-labeled rice

All the inter-carbon correlations are summarized in Fig. 5c. For cellulose, the large number of cross peaks allows us to assign the 13C chemical shifts of all carbons in interior and surface glucan chains. The flat-ribbon twofold xylan has shown 4 distinguishable signals, while the non-flat threefold xylan only exhibits a single cross peak from carbon 1 to carbon 2 (Xn3f1-2). The spectral pattern of CHHC resembles those PDSD spectra that measured using 13C-labeled plant biomass (Fig. 5d, Additional file 1: Fig. S7). Therefore, natural-abundance MAS-DNP has the full capability of investigating cellulose structure; it is also partially prepared for investigating matrix polysaccharides.

It should be noted that the CHHC experiment is specifically chosen for natural-abundance MAS-DNP. For most other 2D correlation methods, such as PDSD and DARR, the diagonal peaks will dominate the spectrum of unlabeled materials, because the probability of observing off-diagonal internuclear correlation is very low at natural 13C abundance. The CHHC experiment can effectively avoid this issue due to the 13C–1H–1H–13C pathway used for polarization transfer [56]. Alternatively, dipolar homonuclear recoupling schemes could also be used for characterizing unlabeled biomaterials [22, 57].

Motional rates and amplitudes of cell wall polysaccharides

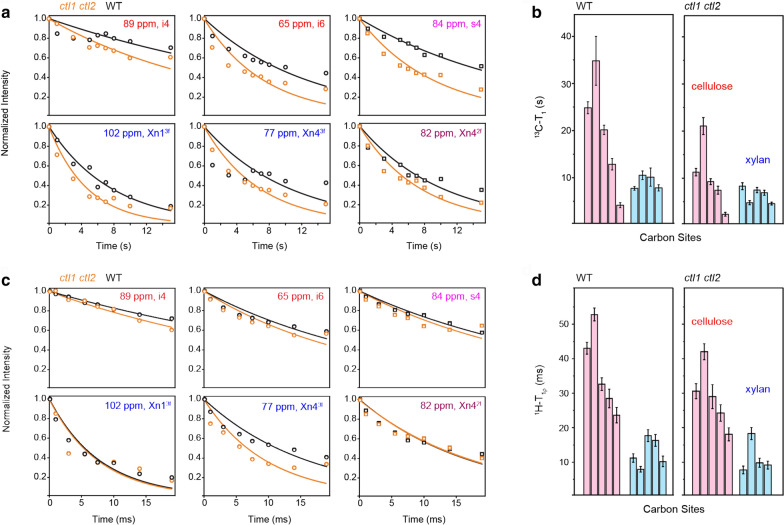

To understand the effect of ctl1 ctl2 mutation on polymer dynamics, we have measured 13C–T1 and 1H–T1ρ relaxation times using the unlabeled stems of WT and ctl1 ctl2 samples. As the most rigid component of cell walls, cellulose exhibits very slow 13C–T1 relaxation (typically on the order of 10–40 s), revealing its lack of motion on the nanosecond timescale (Fig. 6a, b, Additional file 1: Table S4 and Additional file 1: Fig. S8). In contrast, the 13C–T1 of threefold xylan, the conformer that fills the interfibrillar space, is shorter by 4–5 times: 7.7 s for carbon 1 and 10 s for carbon 4 in the WT sample. The twofold xylan, a unique form induced by its packing with cellulose surface, has shown an intermediate 13C–T1 of 10.5 s for its resolved peak of carbon 4. These 13C–T1 time constants are substantially longer than the values reported for uniformly 13C-labeled materials (4–6 s for cellulose and 1–2 s for matrix polysaccharides) [47]. This can be attributed to the lack of spin exchange between rigid and mobile motifs in unlabeled materials.

Fig. 6.

Carbohydrate dynamics probed by NMR relaxation using unlabeled rice stems at ambient temperature. a Representative 13C–T1 relaxation curves of cellulose (top row) and xylan (second row). The ctl1 ctl2 double mutant has shown substantially faster relaxation than the wild-type sample, indicating more pronounced motions on the nanosecond timescale. b Bar diagram summarizing the 13C–T1 relaxation times of cellulose (pink) and xylan (blue). The x-axis represents different carbon sites, which can be found in Additional file 1: Table S4. c Representative 1H-T1ρ relaxation curves. For most peaks, the double mutant shows faster 1H–T1ρ relaxation than the wild-type sample, indicating enhanced dynamics on the microsecond timescale. All the 1H–T1ρ relaxation time constants are summarized in d

The 1H–T1ρ data are highly consistent with the 13C–T1 results. Cellulose remains as the most rigid component on the slower, microsecond timescale, with a representative 1H–T1ρ time of 20–50 ms in WT stems (Fig. 6c, d). The twofold and threefold conformers of xylan have more pronounced dynamics, showing 1H–T1ρ values of 18 ms and 8–16 ms, respectively. Interestingly, most polysaccharides have considerably faster 13C–T1 and 1H–T1ρ relaxations in the ctl1 ctl2 mutant, indicative of a flawed cell wall formed by polysaccharides that are highly mobile on both nanosecond and millisecond timescales.

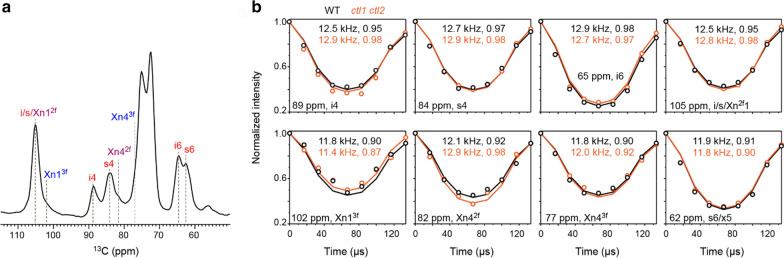

To examine the motional amplitudes of these polysaccharides, we have conducted the 13C–1H dipolar-chemical shift (DIPSHIFT) correlation experiment at ambient temperature without DNP (Fig. 7) [58]. Polymer dynamics can only be measured using non-DNP methods (Table 1), because molecular motions will be significantly restricted at the cryogenic temperature associated with DNP experiments. The 13C–1H dipolar couplings (in kHz) are measured at representative carbon sites of cellulose and xylan, which are further converted to dipolar order parameters. A near-unity value indicates restricted motional amplitudes for the C–H bonds, while a small order parameter suggests large-amplitude motions. Strikingly, all polysaccharides are highly rigid and exhibit large order parameters above 0.90 (Fig. 7b). This is very different from the results collected using Arabidopsis and Brachypodium primary cell walls, in which the order parameters range from 0.3 to 0.6 for matrix polymers [5, 47]. Cellulose has identical order parameters in WT and ctl1 ctl2 samples. The hemicellulose, however, has shown subtle changes: the order parameter has slightly decreased for the carbon 1 of threefold xylan (Xn13f), but increased for the carbon 4 of twofold xylan (Xn42f). These two peaks are the best-resolved signals of xylan, and the discrepancy observed here suggests a small extent of phase separation in the double mutant: the cellulose-packed twofold xylan becomes even more rigid in the mutant while the interfibrillar threefold conformer undergoes even larger amplitude motions. The relaxation and DIPSHIFT experiments can systematically assess the motional characteristics of polysaccharides, which complement the 2D MAS-DNP data to provide a complete view of polymer composition, structure, and dynamics in unlabeled biomass.

Fig. 7.

Dipolar order parameters of polysaccharides in unlabeled rice cell walls at room-temperature. a The first slice of the 2D DIPSHIFT experiment measured under 7.5 kHz MAS, which shows the signals of cellulose and xylan. b 13C − 1H dipolar evolution curves extracted from 2D DIPSHIFT experiment. The fit dipolar coupling values (in kHz) and the dipolar order parameters are labeled for each panel. Most carbon sites, except for some xylan peaks, have shown comparable order parameters in the wild-type sample and the mutant

Discussion

Using a common sample of agriculture lignocellulosic biomass, rice stems, we have demonstrated the feasibility of employing ssNMR and MAS-DNP methods to investigate the structure and dynamics of cell wall polysaccharides without 13C enrichment. The strategy and the experiments described above can be directly applied to many other biomass samples. The method is time-efficient: the total experimental time is 254 h for the wild-type stems, which includes 132 h of measurements on a 600 MHz/395 GHz DNP instrument and 122 h on a conventional 400 MHz ssNMR spectrometer. As a demonstration, this study involves the investigations of several aspects including polymer composition, structure, and dynamics. If only a single aspect is to be investigated, the experimental time will be much shorter.

Multiple factors can impact the enhancement factor and experimental time, for example, the mixing protocol that determines biradical distribution in cell wall materials, the sample pH that affects the lifetime and stability of radicals (the DNP solvent mixture by itself typically has a pH on the range of 7–8), and the choice of DNP solvent. As the beginning step, it is crucial to collect a set of 1D spectra to screen several samples prepared using different protocols and conditions, each of which only takes a few minutes to measure. By monitoring the absolute sensitivity and the DNP gain, the optimal condition will be identified for measuring 2D experiments.

At present, natural-abundance DNP still has limitations. First, it is impossible to derive a detailed pattern of intermolecular contacts using only unlabeled materials (Table 1). This is due to the demanding requirement of sensitivity for probing longer range correlations, which can even be challenging for some 13C-labeled samples. Progress is being made: long-range correlations, typically on the range of 3–5 Å, have been observed recently using model cyclic peptides [22]. Once successfully extended to cellular samples, these techniques will fully enable structural determination. Partial information could be obtained if the polymer contact depends on the conformational structure. For example, the flat-ribbon structure of twofold xylan is responsible for coating cellulose surface; therefore, we have tracked its amount to estimate the extent of xylan–cellulose packing in unlabeled rice stems [24]. Second, molecules with a high disorder suffer from intensity loss under MAS-DNP conditions. Fortunately, we still have distinguishable carbon sites for different xylan conformers, which can be used for structural and compositional analysis. In addition, ssNMR and DNP approaches provide atomic-level resolution on intact plant materials, but they are often limited in sensitivity and resolution for compositional analysis. Therefore, it is a promising strategy to combine ssNMR and traditional chemical assays to systematically investigate the composition of different polymers and the amount of each of their subtypes that are undertaking a variety of conformations and structures.

In this demonstrative study, we have achieved a satisfactory DNP performance using the rice stems: an enhancement factor in the range of 40- to 60-fold (Table 2) shortens the experimental time by 1600–3600 times. It should be noted that MAS-DNP is still undergoing revolution; tremendous efforts have been devoted to further improving its efficiency. Multiple biradicals have been developed recently, such as the AsymPolPOK family that shortens the DNP build-up time [33] and the Tinypol and TEMTRIPol-I radicals that have shown improved performance over AMUPol on high-field (18.8 and 21.1 T) DNP instruments [31, 59, 60]. The resolution improvement at high-field MAS-DNP (e.g., 800 MHz/527 GHz) will allow us to better analyze biomolecular structures, at least for the molecules bearing structural order [61, 62]. The rapidly evolving MAS-DNP technology has a great potential to bring biomass analysis to a new level of details.

Conclusions

We have presented a strategy that integrates DNP-enabled natural-abundance 2D 13C–13C correlation experiments with room-temperature measurements of polymer dynamics to analyze unlabeled plant cell walls. Because this protocol no longer requires isotopic enrichment, it now becomes possible and time-efficient to screen a large collection of lignocellulose materials found in nature or engineered in vitro. Consequently, the large-scale and high-resolution biomass characterization will provide the structural foundation for improving the biotechnologies of biofuel production.

Materials and methods

Rice stem preparation

The mutant ctl1 was generated by backcrossing a previously reported mutant brittle culm 15 (A213L mutation in OsCTL1) into Oryza sativa cv. Nipponbare background [41]. The ctl2 is an insertional mutant (NC2596 from rice Tos17 insertion mutant database) with a Tos17 insertion at the 1633 bp downstream of the OsCTL2 (LOC_Os08g41100) coding sequence. The double-mutant ctl1 ctl2 was created by crossing ctl1 and ctl2 and then screening out from the F2 progenies via molecular identification. All the WT and mutant rice plants (Oryza sativa) were grown in the experimental fields at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology in Beijing (China). At least five mature stems from different plants of each genotype were harvested for the measurement.

Dynamic nuclear polarization sample preparation

The unlabeled rice stems were sliced using a razor into pieces that are on the dimension of a few millimeters. The materials were mixed with a stock solution, which contains 10 mM AMUPol radical [30] and a solvent mixture of 13C-depleted, d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O (60/30/10 vol%). Around 50 mg of the rice material was impregnated in 100 μL of the AMUPol solution and then ground for 20–30 min, which allows the radicals to penetrate the porous cell walls. Around 33 mg of the plant material was transferred to a 3.2-mm sapphire rotor for DNP experiments. To evaluate the effect of different solvents on DNP efficiency, various matrix protocols are used, including the d6-DMSO/D2O/H2O (60/30/10 vol%), d6-DMSO/D2O/H2O (80/10/10 vol%), D2O/H2O (75/25 vol%), and a matrix-free protocol [23, 49]. A video protocol can be found in reference [52].

Dynamic nuclear polarization experiment

All DNP experiments were conducted on a 600 MHz (14.1 T)/395 GHz MAS-DNP instrument at National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Tallahassee, Florida [27]. The DNP spectra were collected using a 3.2-mm probe under 8 kHz MAS. All 13C chemical shifts were reported on the TMS scale. The microwave irradiation is around 12 W. The temperature was 104 K with microwave irradiation and decreased to 94 K when the microwave was turned off. The DNP build-up time was measured to be 2.77 s for the wild-type sample and 2.59 s for the ctl1 ctl2 sample. Therefore, the recycle delay was typically 3.7 and 3.4 s for the wild-type and ctl1 ctl2 samples, respectively. 1D 13C CP spectra were collected using a 1 ms contact time. A total number of 256 and 512 scans were collected on the wild type, and ctl1 ctl2 samples, respectively. The total experimental time ranges from 16 to 29 min for each sample.

Two types of 2D 13C–13C correlation experiments were conducted on the rice stems: a 2D CP J-INADEQUATE experiment that probes through-bond correlations [53] and a 2D CHHC experiment that probes spatial correlations [55]. For the INADEQUATE spectra, a total number of 320 scans were recorded within 35 h for the wild-type sample. The indirect dimension includes 110 points. CHHC spectrum was much more time-consuming and was only collected on the wild-type sample. For 1 ms CHHC, a total of 320 scans were collected over 36 h, with 64 points in the indirect dimension, and for 2 ms CHHC, a total of 608 scans were collected over 60 h, with the indirect dimension varying from 50 to 60 points. The CHHC experiment relied on 3 CP blocks to transfer polarization from 1H to 13C, back to 1H to enable 1H spin diffusion, and then back to 13C for site-specific detection. The corresponding contact times of the three CP blocks were 1 ms, 0.5 ms, and 0.5 ms, respectively.

Room-temperature solid-state NMR

Multiple experiments were conducted at room temperature to compare with the DNP data. Around 65 mg of unlabeled rice stems were packed into a 4-mm ZrO2 rotor for measurements. All non-DNP experiments were conducted on a 400 MHz (9.4 T) Bruker spectrometer using a 4-mm HCN probe. 1D 13C quantitative spectra were collected using the recently developed MultiCP pulse sequence at room temperature under 10 kHz [43]. This experiment allows for the quantitative detection of all 13C signals with enhanced sensitivity. Within each experiment, 8 CP blocks were used for WT and ctl1 ctl2 double-mutant sample, and 9 blocks were used for ctl1 and ctl2 single mutant rice, with a z-filter time of 0.9 s between two CP blocks for repolarization. In total, 20 k, 23 k, 23 k, and 20 k scans were collected for the WT, ctl1, ctl2, and ctl1 ctl2 samples, respectively. To investigate the molecular motion of polysaccharides in unlabeled rice stems, we have measured 13C–T1 and 1H–T1ρ relaxation. 13C–T1 probes the molecular motions characteristic to the nanosecond timescale and 1H–T1ρ probes the motion happening on the wloser, microsecond timescale. 13C–T1 was measured using a CP-based experiment [63], with a variable z-filter from 0 to 16 s. 1H–T1ρ was measured using a spinlock field of 62.5 kHz on the 1H channel, with a variable spinlock time from 0 to 20 ms. The relative intensity of each data point (relative to the first data point) was plotted as a function of time and fit using a single-exponential equation. For 13C-T1 relaxation, 4 k and 3 k scans are collected for each time point of WT and ctl1 ctl2 samples, respectively. Meanwhile, 6 k (WT) and 2 k (ctl1 ctl2) scans are collected for each time point of the 1H–T1ρ relaxation experiment. In addition, we have conducted the dipolar-chemical shift (DIPSHIFT) correlation experiment under 7.5 kHz MAS [58]. Frequency-Switched Lee Goldburg (FSLG) sequence was used for 1H homonuclear decoupling, with a transverse field of 83 kHz and an effective field of 102 kHz. The scaling factor is 0.577 as verified using a model tripeptide MLF.

In addition, we have measured a series of 2D PDSD experiments using 13C-labeled rice stems to compare with the DNP-assisted 2D CHHC experiment collected on unlabeled samples. Around 85 mg 13C-labeled rice material was packed into a 4-mm ZrO2 rotor for the solid-state NMR experiment. The mixing times were chosen to be 1, 2, 3, and 5 ms for four different spectra.

Spectral deconvolution

Spectral deconvolution of the cellulose peaks was performed using DmFit software [64]. Deconvolution was performed on the 120 to 50 ppm interval to position the baseline. For the region of interest, the C4 region, deconvolution was initiated with Lorentzian lines while keeping their number to a minimum and fixing their chemical shift according to our previous studies of cellulose conformers in plants [10, 45]. This choice was deemed satisfactory, as perfectly matching the spectrum for interior cellulose, and with a small error margin for surface cellulose. For C1, C6, and C2,3,5 regions, Gaussian lines were used to allow better fit of the bases of peaks and allow the components of C2,3,5 to have minimal overlap with the region of interest (C4). Additionally, referring to previously established chemical shifts and the data indexed in a recently developed carbohydrate ssNMR database [65] provided both good agreement of major line positions relative to the 'modulation envelope' (spectrum) and fit initiation for minor components, which amplitude is too low to be even partially resolved. Finally, it has to be noted that peak intensities are manually adjusted, as automatic computation does not usually yield satisfactory results, as algorithm tend to severely broaden every peak in C4 region to compensate baseline distortions between 90 and 95 ppm.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Fit parameters of 13C CP spectrum of wild-type (WT) sample. Table S2. Fit parameters of 13C CP spectrum of ctl1 ctl2 double mutant. Table S3. Peak numbers of INADEQUATE spectra shown in Fig. 4. Table S4. 13C-T1 and 1H-T1ρ relaxation times of cellulose and xylan in WT and ctl1 ctl2 samples. Figure S1. Lignin has increased methyl ether substitution in the double mutant. Figure S2. Additional dataset of samples prepared using different protocols. Figure S3. Timesaving by DNP on carbohydrate signals in unlabeled rice stems. Figure S4. DNP polarization is uniform across the cell wall. Figure S5. The experimental and simulated spectra have a good match. Figure S6. 1D cross sections of DNP-enabled 2D CHHC spectrum. Figure S7. 2D PDSD spectra of 13C-labeled rice stems. Figure S8. NMR relaxation curves of polysaccharides in unlabeled rice stems.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DNP

Dynamic nuclear polarization

- ssNMR

Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance

- MAS

Magic-angle spinning

- PDSD

Proton-driven spin diffusion

- TMS

Trimethylsilyl

- WT

Wild-type

- DIPSHIFT

Dipolar-chemical shift experiment

- INADEQUATE

Incredible natural-abundance double quantum transfer experiment

Authors’ contributions

WZ, AK, and FMV performed all DNP experiments. FD performed room-temperature NMR experiments. WZ and FD analyzed data and prepared figures. YZ and BZ prepared the samples. TW and BZ designed the project. TW, WZ, BZ, YZ, and FMV wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The DNP analysis of plant cell walls is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (grant no. DE-SC0021210). Room-temperature experiments and spectral deconvolution were conducted by FD, who is supported as part of the Center for Lignocellulose Structure and Formation, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award number DE-SC0001090. YZ and BZ were supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (31571247). The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory is supported by National Science Foundation through NSF/DMR-1644779 and the State of Florida. The MAS-DNP instrument at NHMFL is funded in part by NIH S10 OD018519, NIH P41-GM122698-01, and NSF CHE-1229170.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13068-020-01858-x.

References

- 1.Zhao W, Fernando LD, Kirui A, Deligey F, Wang T. Solid-state NMR of plant and fungal cell walls: a critical review. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 2020;107:101660. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2020.101660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dick-Perez M, Zhang YA, Hayes J, Salazar A, Zabotina OA, Hong M. Structure and interactions of plant cell wall polysaccharides by two- and three-dimensional magic-angle-spinning solid-state NMR. Biochemistry US. 2011;50(6):989–1000. doi: 10.1021/bi101795q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang T, Zabotina O, Hong M. Pectin-cellulose interactions in the Arabidopsis primary cell wall from two-dimensional magic-angle-spinning solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry US. 2012;51(49):9846–9856. doi: 10.1021/bi3015532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang T, Chen YN, Tabuchi A, Cosgrove DJ, Hong M. The target of beta-Expansin EXPB1 in maize cell walls from binding and solid-state NMR studies. Plant Physiol. 2016;172(4):2107–2119. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang T, Salazar A, Zabotina OA, Hong M. Structure and dynamics of Brachypodium primary cell wall polysaccharides from two-dimensional 13C solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry US. 2014;53(17):2840–2854. doi: 10.1021/bi500231b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terrett OM, Lyczakowski JJ, Yu L, Iuga D, Franks WT, Brown SP, Dupree R, Dupree P. Molecular architecture of softwood revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4978. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12979-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grantham NJ, Wurman-Rodrich J, Terrett OM, Lyczakowski JJ, Stott K, Iuga D, Simmons TJ, Durand-Tardif M, Brown SP, Dupree R, et al. An even pattern of xylan substitution is critical for interaction with cellulose in plant cell walls. Nat Plants. 2017;3(11):859–865. doi: 10.1038/s41477-017-0030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simmons TJ, Mortimer JC, Bernardinelli OD, Poppler AC, Brown SP, deAzevedo ER, Dupree R, Dupree P. Folding of xylan onto cellulose fibrils in plant cell walls revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13902. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupree R, Simmons TJ, Mortimer JC, Patel D, Iuga D, Brown SP, Dupree P. Probing the molecular architecture of Arabidopsis thaliana secondary cell walls using two- and three-dimensional 13C solid state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry US. 2015;54(14):2335–2345. doi: 10.1021/bi501552k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang X, Kirui A, Dickwella Widanage MC, Mentink-Vigier F, Cosgrove DJ, Wang T. Lignin-polysaccharide interactions in plant secondary cell walls revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):347. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold AA, Bourgouin JP, Genard B, Warschawski DE, Tremblay R, Marcotte I. Whole cell solid-state NMR study of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii microalgae. J Biomol NMR. 2018;70(2):123–131. doi: 10.1007/s10858-018-0164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang X, Kirui A, Muszynski A, Widanage MCD, Chen A, Azadi P, Wang P, Mentink-Vigier F, Wang T. Molecular architecture of fungal cell walls revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2747. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05199-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chrissian C, Camacho E, Kelly JE, Wang H, Casadevall A, Stark RE. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy identifies three classes of lipids in C. neoformans melanized cell walls and whole fungal cells. J Biol Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith PJ, Wang HT, York WS, Pena MJ, Urbanowicz BR. Designer biomass for next-generation biorefineries: leveraging recent insights into xylan structure and biosynthesis. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:286. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0973-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Y, Mortimer JC. Unlocking the architecture of native plant cell walls via solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. Methods Cell Biol. 2020;160:121–143. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossini AJ, Zagdoun A, Lelli M, Lesage A, Coperet C, Emsley L. Dynamic nuclear polarization surface enhanced NMR spectroscopy. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(9):1942–1951. doi: 10.1021/ar300322x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ni QZ, Daviso E, Can TV, Markhasin E, Jawla SK, Swager TM, Temkin RJ, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. High frequency dynamic nuclear polarization. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:1933–1941. doi: 10.1021/ar300348n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lilly Thankamony AS, Wittmann JJ, Kaushik M, Corzilius B. Dynamic nuclear polarization for sensitivity enhancement in modern solid-state NMR. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Sp. 2017;102–103:120–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee D, Hediger S, De Paepe G. Is solid-state NMR enhanced by dynamic nuclear polarization? Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 2015;66–67:6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith AN, Marker K, Hediger S, De Paepe G. Natural isotopic abundance 13C and 15N multidimensional solid-state NMR enabled by dynamic nuclear polarization. J Phys Chem Lett. 2019;10(16):4652–4662. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b03874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi H, Lee D, Dubois L, Bardet M, Hediger S, De Paepe G. Rapid natural-abundance 2D 13C–13C correlation spectroscopy using dynamic nuclear polarization enhanced solid-state NMR and matrix-free sample preparation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51(47):11766–11769. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marker K, Paul S, Fernandez-de-Alba C, Lee D, Mouesca JM, Hediger S, De Paepe G. Welcoming natural isotopic abundance in solid-state NMR: probing pi-stacking and supramolecular structure of organic nanoassemblies using DNP. Chem Sci. 2017;8(2):974–987. doi: 10.1039/C6SC02709A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirui A, Ling Z, Kang X, Dickwella Widanage MC, Mentink-Vigier F, French AD, Wang T. Atomic resolution of cotton cellulose structure enabled by dynamic nuclear polarization solid-state NMR. Cellulose. 2019;26:329–339. doi: 10.1007/s10570-018-2095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Gao C, Mentink-Vigier F, Tang L, Zhang D, Wang S, Cao S, Xu Z, Liu X, Wang T, et al. Arabinosyl deacetylase modulates the arabinoxylan acetylation profile and secondary wall formation. Plant Cell. 2019 doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perras FA, Luo H, Zhang X, Mosier NS, Pruski M, Abu-Omar MM. Atomic-level structure characterization of biomass pre- and post-lignin treatment by dynamic nuclear polarization-enhanced solid-state NMR. J Phys Chem A. 2017;121(3):623–630. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b11121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sergeyev IV, Aussenac F, Purea A, Reiter C, Bryerton E, Retzloff S, Hesler J, Tometich L, Rosay M. Efficient 263 GHz magic angle spinning DNP at 100 K using solid-state diode sources. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 2019;100:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubroca T, Smith AN, Pike KJ, Froud S, Wylde R, Trociewitz B, Mckay J, Mentink-Vigier F, van Tol J, Wi S, et al. A quasi-optical and corrugated waveguide microwave transmission system for simultaneous dynamic nuclear polarization NMR on two separate 14.1 T spectrometers. J Magn Reson. 2018;289:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuki Y, Idehara T, Fukazawa J, Fujiwara T. Advanced instrumentation for DNP-enhanced MAS NMR for higher magnetic fields and lower temperatures. J Magn Reson. 2016;264:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaudhari SR, Berruyer P, Gajan D, Reiter C, Engelke F, Silverio DL, Coperet C, Lelli M, Lesage A, Emsley L. Dynamic nuclear polarization at 40 kHz magic angle spinning. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016;18(15):10616–10622. doi: 10.1039/C6CP00839A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sauvee C, Rosay M, Casano G, Aussenac F, Weber RT, Ouari O, Tordo P. Highly efficient, water-soluble polarizing agents for dynamic nuclear polarization at high frequency. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2013;52(41):10858–10861. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lund A, Casano G, Menzildjian G, Kaushik M, Stevanato G, Yulikov M, Jabbour R, Wisser D, Renom-Carrasco M, Thieuleux C, et al. TinyPols: a family of water-soluble binitroxidestailored for dynamic nuclear polarization enhancedNMR spectroscopy at 18.8 and 21.1 T. Chem Sci. 2020;11:2810. doi: 10.1039/C9SC05384K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevanato G, Casano G, Kubicki DJ, Rao Y, Esteban Hofer L, Menzildjian G, Karoui H, Siri D, Cordova M, Yulikov M, et al. Open and closed radicals: local geometry around unpaired electrons governs magic-angle spinning dynamic nuclear polarization performance. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142:16587–16599. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c04911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mentink-Vigier F, Marin-Montesinos I, Jagtap AP, Halbritter T, van Tol J, Hediger S, Lee D, Sigurdsson ST, De Paepe G. Computationally assisted design of polarizing agents for dynamic nuclear polarization enhanced NMR: the AsymPol family. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(35):11013–11019. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b04911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atalla RH, Vanderhart DL. Native cellulose: a composite of two distinct crystalline forms. Science. 1984;223(4633):283–285. doi: 10.1126/science.223.4633.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ha MA, Apperley DC, Evans BW, Huxham M, Jardine WG, Vietor RJ, Reis D, Vian B, Jarvis MC. Fine structure in cellulose microfibrils: NMR evidence from onion and quince. Plant J. 1998;16(2):183–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du X, Gellerstedt G, Li J. Universal fractionation of lignin–carbohydrate complexes (LCCs) from lignocellulosic biomass: an example using spruce wood. Plant J. 2013;74(2):328–338. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bardet M, Gerbaud G, Giffard M, Doan C, Sabine H, Le Page L. 13C high-resolution solid-sate NMR for structural elucidation of archaeological woods. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Sp. 2009;55:199–224. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2009.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hermans C, Porco S, Vandenbussche F, Gille S, De Pessemier J, Van Der Straeten D, Verbruggen N, Bush DR. Dissecting the role of CHITINASE-LIKE1 in nitrate-dependent changes in root architecture. Plant Physiol. 2011;157(3):1313–1326. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.181461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiao S, Hazebroek JP, Chamberlin MA, Perkins M, Sandhu AS, Gupta R, Simcox KD, Yinghong L, Prall A, Heetland L, et al. Chitinase-like1 plays a role in stalk tensile strength in maize. Plant Physiol. 2019;181(3):1127–1147. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez-Rodriguez C, Bauer S, Hematy K, Saxe F, Ibanez AB, Vodermaier V, Konlechner C, Sampathkumar A, Ruggeberg M, Aichinger E, et al. Chitinase-like1/pom-pom1 and its homolog CTL2 are glucan-interacting proteins important for cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24(2):589–607. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.094672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu B, Zhang B, Dai Y, Zhang L, Shang-Guan K, Peng Y, Zhou Y, Zhu Z. Brittle culm15 encodes a membrane-associated chitinase-like protein required for cellulose biosynthesis in rice. Plant Physiol. 2012;159(4):1440–1452. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.195529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan P, Schmidt-Rohr K. Composite-pulse and partially dipolar dephased multiCP for improved quantitative solid-state (13)C NMR. J Magn Reson. 2017;285:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson RL, Schmidt-Rohr K. Quantitative solid-state 13C NMR with signal enhancement by multiple cross polarization. J Magn Reson. 2014;239:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernardinelli OD, Lima MA, Rezende CA, Polikarpov I, de Azevedo ER. Quantitative C-13 MultiCP solid-state NMR as a tool for evaluation of cellulose crystallinity index measured directly inside sugarcane biomass. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:110. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0292-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang T, Yang H, Kubicki JD, Hong M. Cellulose structural polymorphism in plant primary cell walls investigated by high-field 2D solid-state NMR spectroscopy and density functional theory calculations. Biomacromol. 2016;17(6):2210–2222. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phyo P, Wang T, Yang Y, O'Neill H, Hong M. Direct Determination of hydroxymethyl conformations of plant cell wall cellulose using 1H polarization transfer solid-state NMR. Biomacromol. 2018;19(5):1485–1497. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang T, Park YB, Cosgrove DJ, Hong M. Cellulose-pectin spatial contacts are inherent to never-dried arabidopsis thaliana primary cell walls: evidence from solid-state NMR. Plant Physiol. 2015;168(3):871–884. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White PB, Wang T, Park YB, Cosgrove DJ, Hong M. Water-polysaccharide interactions in the primary cell wall of Arabidopsis thaliana from polarization transfer solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(29):10399–10409. doi: 10.1021/ja504108h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takahashi H, Hediger S, De Paepe G. Matrix-free dynamic nuclear polarization enables solid-state NMR C-13-C-13 correlation spectroscopy of proteins at natural isotopic abundance. Chem Commun. 2013;49(82):9479–9481. doi: 10.1039/c3cc45195j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandez-de-Alba C, Takahashi H, Richard A, Chenavier Y, Dubois L, Maurel V, Lee D, Hediger S, De Paepe G. Matrix-free DNP-enhanced NMR spectroscopy of liposomes using a lipid-anchored biradical. Chem Eur J. 2015;21(12):4512–4517. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viger-Gravel J, Lan W, Pinon AC, Berruyer P, Emsley L, Bardet M, Luterbacher J. Topology of pretreated wood fibers using dynamic nuclear polarization. J Phys Chem C. 2019;123(50):30407–30415. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b09272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirui A, Dickwella Widanage MC, Mentink-Vigier F, Wang P, Kang X, Wang T. Preparation of fungal and plant materials for structural elucidation using dynamic nuclear polarization solid-state NMR. J Vis Exp. 2019;144:e59152. doi: 10.3791/59152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lesage A, Auger C, Caldarelli S, Emsley L. Determination of through-bond carbon-carbon connectivities in solid-state NMR using the INADEQUATE experiment. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119(33):7867–7868. doi: 10.1021/ja971089k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lesage A, Bardet M, Emsley L. Through-bond carbon−carbon connectivities in disordered solids by NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121(47):10987–10993. doi: 10.1021/ja992272b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aluas M, Tripon C, Griffin JM, Filip X, Ladizhansky V, Griffin RG, Brown SP, Filip C. CHHC and 1H–1H magnetization exchange: Analysis by experimental solid-state NMR and 11-spin density-matrix simulations. J Magn Reson. 2009;199(2):173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kobayashi T, Slowing II, Pruski M. Measuring long-range 13C–13C correlations on a surface under natural abundance using dynamic nuclear polarization-enhanced solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. J Phys Chem C. 2017;121:24687–24691. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b08841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teymoori G, Pahari B, Stevensson B, Eden M. Low-power broadband homonuclear dipolar recoupling without decoupling: Double-quantum C-13 NMR correlations at very fast magic-angle spinning. Chem Phys Lett. 2012;547:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.07.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong M, Gross JD, Rienstra CM, Griffin RG, Kumashiro KK, Schmidt-Rohr K. Coupling amplification in 2D MAS NMR and its application to torsion angle determination in peptides. J Magn Reson. 1997;129(1):85–92. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mentink-Vigier F, Mathies G, Liu Y, Barra AL, Caporini M, Lee D, Hediger S, Griffin RG, De Paepe G. Efficient cross-effect dynamic nuclear polarization without depolarization in high-resolution MAS NMR. Chem Sci. 2017;8:8150. doi: 10.1039/C7SC02199B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhai W, Lucini Paioni A, Cai X, Narasimhan S, Medeiros-Silva J, Zhang W, Rockenbauer A, Weingarth M, Song Y, Baldus M, et al. Postmodification via thiol-click chemistry yields hydrophilic trityl-nitroxide biradicals for biomolecular high-field dynamic nuclear polarization. J Phys Chem B. 2020;124:9047–9060. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c08321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jaudzems K, Bertarello A, Chaudhari SR, Pica A, Cala-De Paepe D, Barbet-Massin E, Pell AJ, Akopjana I, Kotelovica S, Gajan D, et al. Dynamic nuclear polarization-enhanced biomolecular NMR spectroscopy at high magnetic field with fast magic-angle spinning. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2018;57(25):7458–7462. doi: 10.1002/anie.201801016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berruyer P, Bjorgvinsdottir S, Bertarello A, Stevanato G, Rao Y, Karthikeyan G, Casano G, Quari O, Lelli M, Reiter C, et al. Dynamic nuclear polarization enhancement of 200 at 21.15 T enabled by 65 kHz magic angle spinning. J Phys Chem Lett. 2020;11:8386–8391. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c02493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Torchia DA. Measurement of proton-enhanced 13C–T1 values by a method which suppresses artifacts. J Magn Reson. 1978;30:613–616. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Massiot D, Fayon F, Capron M, King I, Le Calve S, Alonso B, Durand JO, Bujoli B, Gan ZH, Hoatson G. Modelling one- and two-dimensional solid-state NMR spectra. Magn Reson Chem. 2002;40:70–76. doi: 10.1002/mrc.984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kang X, Zhao W, Dickwella Widanage MC, Kirui A, Ozdenvar U, Wang T. CCMRD: a solid-state NMR database for complex carbohydrates. J Biomol NMR. 2020;74:239–245. doi: 10.1007/s10858-020-00304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Fit parameters of 13C CP spectrum of wild-type (WT) sample. Table S2. Fit parameters of 13C CP spectrum of ctl1 ctl2 double mutant. Table S3. Peak numbers of INADEQUATE spectra shown in Fig. 4. Table S4. 13C-T1 and 1H-T1ρ relaxation times of cellulose and xylan in WT and ctl1 ctl2 samples. Figure S1. Lignin has increased methyl ether substitution in the double mutant. Figure S2. Additional dataset of samples prepared using different protocols. Figure S3. Timesaving by DNP on carbohydrate signals in unlabeled rice stems. Figure S4. DNP polarization is uniform across the cell wall. Figure S5. The experimental and simulated spectra have a good match. Figure S6. 1D cross sections of DNP-enabled 2D CHHC spectrum. Figure S7. 2D PDSD spectra of 13C-labeled rice stems. Figure S8. NMR relaxation curves of polysaccharides in unlabeled rice stems.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.