Abstract

We have investigated 44 crystal structures, found in the Cambridge Structural Database, containing the X3 synthon (where X = Cl, Br, I) in order to verify whether three type II halogen–halogen contacts forming the synthon exhibit cooperativity. A hypothesis that this triangular halogen–bonded motif is stabilized by cooperative effects is postulated on the basis of structural data. However, theoretical investigations of simplified model systems in which the X3 motif is present demonstrate that weak synergy occurs only in the case of the I3 motif. In the present paper we computationally investigate crystal structures in which the X3 synthon is present, including halomesitylene structures, that are usually described as being additionally stabilized by a synergic interaction. Our computations find no cooperativity for halomesitylene trimers containing the X3 motif. Only in the case of two other structures containing the I3 synthon a very weak or weak synergy, i.e. the cooperative effect being stronger than −0.40 kcal mol–1, is found. The crystal structure of iodoform has the most pronounced cooperativity of all investigated systems, amounting to about 10% of the total interaction energy.

Short abstract

The halogen−halogen bonded X3 motif present in a crystal structure is considered as consisting of three cooperative halogen−halogen contacts. The hypothesis of interaction cooperativity in the X3 synthons present in crystals is verified. The effect of the presence of other molecules on the cooperativity in a particular synthon is studied.

Introduction

There are two types of halogen–halogen (X···X) contacts occurring in molecular crystals. These two types vary in a mutual spatial arrangement of halogen atoms (Figure 1).1 The symmetrical type I contacts shown in Figure 1a mostly occur in the neighborhood of an inversion center and are attributed to close packing;2 when they are short, they are repulsive.3 Bent type II contacts (Figure 1b), in turn, are related to crystallographic screw axes or glide planes3 and are directly connected with the charge distribution anisotropy of a halogen atom, allowing for attraction between a positively charged equatorial region of one halogen atom and a negatively charged polar region of the other halogen atom (Xδ+···δ−X, Figure 1b).4

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of type I (a) and type II (b) halogen–halogen contacts.

Therefore, type II contacts are halogen bonds,5 since they fulfill a condition according to which the electrophilic site of a halogen atom attracts the nucleophilic site of the other entity.6,7 Type II contacts are exceptional among other halogen bonds because in this case halogen atoms serve not only as an electrophile but also as a nucleophile in the formation of a halogen bond. Thus, when a cyclic trimer or tetramer (Figure 2) consisting of type II contacts is formed, each halogen atom simultaneously plays the dual role of an electrophile and of a nucleophile. One may note here that this feature makes the type II contacts more diverse structurally than dihydrogen bonds Hδ+···δ−H; the lack of significant charge anisotropy makes the hydrogen atom unable to play such a dual role. Cyclic structural motifs consisting of type II contacts occur in crystals: for example, trimers can be found in the crystal structure of trihalomesitylenes8 and tetramers are present in the crystal structure of anti-α-bromoacetophenone oxime.9

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of a halogen–halogen bonded trimer (a) and tetramer (b).

Similarly to hydrogen-bonded systems, in the case of halogen-bonded systems, cooperativity also may play an important role in stabilizing a cluster; N-haloguanine quartets may serve as an example here,10 since in the case of the N-iodoguanine quartet the synergy amounts to about 25% of the total interaction energy.10 Cooperativity is even more pronounced in the case of the iodine cyanide chain, in which the synergy amplifies the interaction energy by 79%.11 Although interaction cooperativity may be manifested in various ways, for example in IR frequency shifts,12 its most fundamental meaning refers to some extra energetic stabilization in a system consisting of more than two subsystems, which results from multibody interactions or, in other words, does not stem from pairwise interactions between monomers. In the case of motifs consisting of several type II contacts, cooperativity was found in halogen–halogen bonded bromoamine and iodoamine tetramers.13 The cooperativity in halogen-bonded haloamine tetramers was traced to donor–acceptor and electrostatic interactions leading to additional stabilization in a stepwise formation of a tetramer.13

The triangular halogen–halogen bonded motif shown in Figure 2a is present in the crystal structures described more than 30 years ago, such as in crystals of 3,5-dibromo-1,2,4-triazole,14 as well as in recently described crystal structures such as the structure of pentachloropyridine N-oxide.15 The triangular halogen–bonded motif in crystal engineering is considered a synthon and is known as the X3 synthon;16 thus, it serves as a building block used in crystal design and engineering. At this point it is important to emphasize that the X3 synthon is present not only in crystals but also in self-assembled nanoarchitectures; there are two-dimensional structures stabilized by the halogen–halogen bonded Br3 and I3 motifs.17−19 Papers devoted to X-ray diffraction results obtained for crystal structures in which the X3 motif occurs postulate that the formation of the X3 synthon from three type II contacts results in cooperative effects.8,20−25 A recent study devoted to halogen–halogen bonded haloamine trimers revealed interaction synergy in bromoamine and iodoamine trimers, but in these systems the cooperativity was significantly reduced in comparison to the corresponding tetramers.26 However, the computational study performed for 16 other model systems consisting of simple molecules and containing the Br3 and I3 motifs showed that these model systems exhibited no or only weak cooperativity (the latter found only for three systems containing the I3 synthon).27 The aim of the present paper is to computationally verify the hypothesis, proposed on the basis of structural data, of cooperative effects occurring in X3 synthons8,20−25 present in crystal structures and, if there is a synergy between halogen–halogen bonds forming X3 motifs in crystals, to find the source of this cooperativity.

Experimental Section

CSD Search

In order to find crystal structures containing homonuclear X3 motifs (where X states for a chlorine, bromine, or iodine atom), a search of the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD version 5.39, February 2018)28 was performed. Systems containing the structurally similar F3 motif were not included in this study because the hypothesis of cooperativity was proposed only for the Cl3, Br3, and I3 motifs.8,20−25 Moreover, fluorine-centered halogen bonding has been proven to be weaker than in the cases of other halogen atoms29 and halogen-bonded systems containing fluorine atoms did not display cooperativity.10 The scheme presented in Figure 2a was used to find crystal structures containing X3 halogen-bonded motifs. During the search the following restrictions on geometric parameters were employed: distances between halogen atoms of the neighboring molecules (X···X) were limited to be smaller than or equal to the sum of the corresponding van der Waals atomic radii and angles θ1 and θ2 were in the range 110–180°. The search was limited to nonionic nondisordered organic crystal structures, where a monovalent X atom in the X3 motif is bonded to a carbon atom and X···X···X angle values are equal to 60.0 ± 5.0°. We found 64 hits in the CSD meeting the aforementioned criteria. Twenty were discarded from further computational investigation because they were the same crystal structures measured either at different temperatures or at different pressures. For each of the crystal structures, a corresponding set of atomic coordinates was collected.

Computational Methods

To prepare geometries from the CSD for our quantum-chemical calculations, the hydrogen atom positions were normalized according to the values given in Table 2 of ref (30). All density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the structures containing the X3 motif were performed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level of theory31−38 using the Amsterdam Density Functional (ADF) program.39−41 Dispersion corrections with D3 formulation34,35 (coupled with the damping function of Becke and Johnson36) were employed; the D3(BJ) correction produces results that are free of basis set superposition errors (BSSE). The relativistic effects were included at this level of computation by applying the zeroth-order regular approximation (ZORA).37,38

The cooperativity in the X3 motifs has been quantified by the many-body method by considering the interaction energy (ΔEint) of a trimer as a sum (ΔEsum) of pairwise interactions (ΔEij, where i and j number the monomers, i, j = 1, 2, 3, and i < j to prevent repetition of terms) and a nonadditive term (the three-body component) or, in other words, cooperativity or synergy (ΔEsyn):

| 1 |

Furthermore, to rationalize interaction energy values obtained for studied systems and also to trace the reason for the cooperativity, we used the quantitative energy decomposition analysis (EDA) in the framework of the Kohn–Sham MO model.42 According to the canonical EDA scheme the interaction energy can be decomposed into the following physically meaningful terms: electrostatic interactions, ΔVelstat, attractive orbital interactions comprising polarization and charge transfer, ΔEoi, Pauli repulsive interactions, ΔEPauli, and the dispersion term, ΔEdisp. Thus, ΔEint can be written as eq 2:42

| 2 |

Results and Discussion

Interactions in Crystal Structures from the CSD

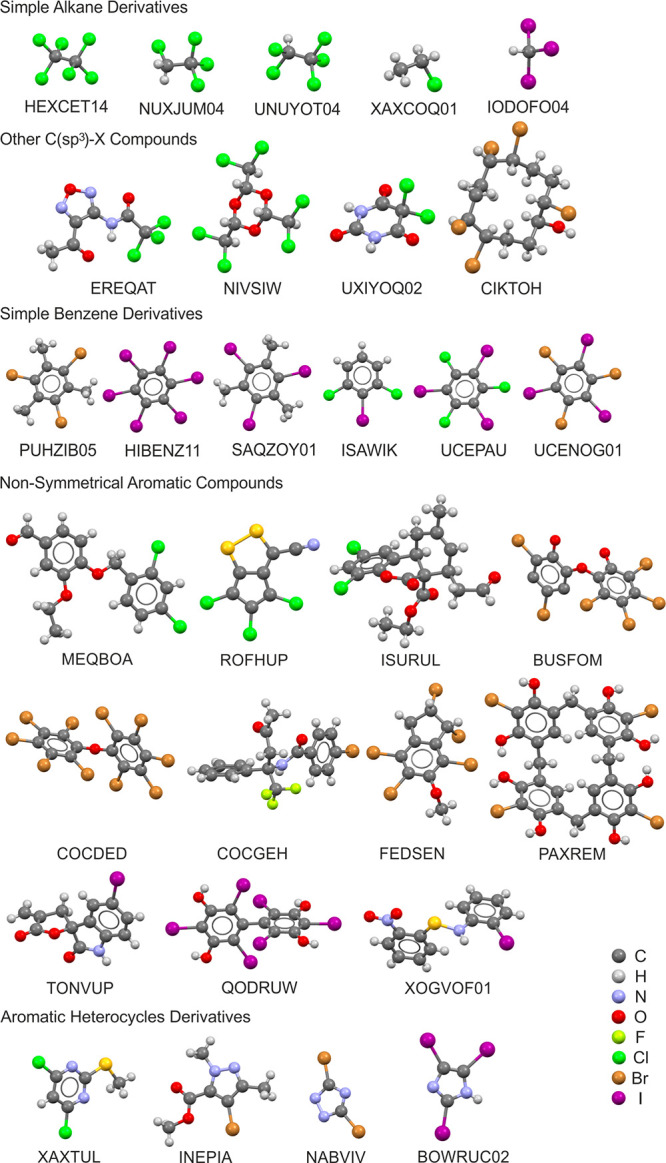

The monomers forming 44 independent structures from the CSD search, together with the corresponding refcodes are shown in Figures 3 (small- and medium-size molecules) and 4 (larger molecules).

Figure 3.

Small- and medium-size molecules forming crystal structures from the CSD search.

Figure 4.

Larger molecules forming crystal structures from the CSD search.

In order to facilitate further analysis, the set of 44 structures was divided into groups of systems of a similar chemical structure: namely, simple alkane derivatives, other compounds in which halogen atoms are bonded to an sp3 carbon atom, simple benzene derivatives, nonsymmetrical aromatic compounds, aromatic heterocycle derivatives, aromatic compounds of 3-fold symmetry, and fullerene derivatives (the last species were only chlorinated; brominated or iodinated fullerenes do not form X3 synthons fulfilling the criteria described in the Experimental Section). The studied crystal structures present various spatial arrangements: from halomesitylenes forming nearly planar sheets (e.g. the structure with refcode PUZHIB05,43 the Br3 motif shown in Figure 5a), through simple haloalkanes forming three-dimensional structures with relatively high symmetry (e.g. the structure with refcode IODOFO04,44 the I3 motif shown in Figure 5b), to chlorinated fullerenes (e.g. the structure with refcode CARROE,45 the Cl3 motif shown in Figure 5c), and many others. The X3 synthons from all 64 crystal structures found in the CSD are presented in Tables S1–S3 in the Supporting Information; X···X distances as well as X···X···X angle values for all structures are given in Tables S4–S6 in the Supporting Information.

Figure 5.

X3 motifs found in crystal structures of tribromomesitylene (a), iodoform (b), and docosachloro-Cs-C88 fullerene (c).

The results of an analysis of interaction energies, according to eq 1, for the 44 independent crystal structures are collected in Table 1 (the Cl3 motif), Table 2 (the Br3 motif), and Table 3 (the I3 motif). The results for the other 20 CSD hits (these of lower interaction synergy from among the same structures measured under different conditions) are gathered in Table S7 in the Supporting Information.

Table 1. Analysis of Interaction Energies in Cl3 Motifs Found in Crystal Structures from the CSD (in kcal mol–1)a.

| refcode | ΔEint | ΔVelstat | ΔEoi | ΔEPauli | ΔEdisp | ΔEsum | ΔEsyn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Alkane Derivatives | |||||||

| HEXCET1446 | –7.19 | –11.10 | –5.15 | 25.80 | –16.75 | –7.01 | –0.18 |

| NUXJUM0447 | –4.43 | –6.90 | –3.16 | 16.07 | –10.44 | –4.39 | –0.04 |

| UNUYOT0448 | –6.29 | –6.21 | –3.54 | 13.50 | –10.04 | –6.30 | 0.01 |

| XAXCOQ0149 | 1.16 | –2.19 | –2.41 | 10.17 | –4.41 | 1.26 | –0.10 |

| Other −C(sp3)–X | |||||||

| EREQAT50 | –7.92 | –8.32 | –4.40 | 17.79 | –12.98 | –7.80 | –0.12 |

| NIVSIW51 | –4.75 | –4.07 | –2.52 | 10.90 | –9.05 | –4.71 | –0.04 |

| UXIYOQ0252 | –5.13 | –4.64 | –2.48 | 10.05 | –8.06 | –5.17 | 0.04 |

| Aromatic Heterocycle Derivatives | |||||||

| XAXTUL53 | –5.97 | –5.28 | –3.09 | 13.83 | –11.43 | –5.57 | –0.40 |

| Nonsymmetrical Aromatic Derivatives | |||||||

| ISURUL54 | –8.49 | –7.27 | –3.62 | 16.64 | –14.23 | –8.49 | 0.00 |

| MEQBOA55 | –8.54 | –5.05 | –3.41 | 12.43 | –12.51 | –8.50 | –0.04 |

| ROFHUP56 | –8.56 | –5.83 | –4.28 | 13.86 | –12.31 | –8.49 | –0.07 |

| Aromatic Derivatives of 3-Fold Symmetry | |||||||

| VALQEE0116 | –2.78 | –2.37 | –1.76 | 6.64 | –5.28 | –2.72 | –0.06 |

| VEWJIQ24 | –2.72 | –2.85 | –2.02 | 7.67 | –5.52 | –2.64 | –0.08 |

| XEHMAY22 | –3.09 | –2.82 | –1.89 | 7.65 | –6.03 | –2.99 | –0.10 |

| Fullerene Derivatives | |||||||

| CARROE45 | –41.64 | –24.59 | –12.38 | 59.62 | –64.29 | –41.60 | –0.04 |

| VODWOB57 | –30.56 | –20.76 | –12.34 | 51.31 | –48.76 | –30.45 | –0.11 |

| YEFNII58 | –34.91 | –17.23 | –10.39 | 43.84 | –51.13 | –34.96 | 0.05 |

Computed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level.

Table 2. Analysis of Interaction Energies in Br3 Motifs Found in Crystal Structures from the CSD (in kcal mol–1)a.

| refcode | ΔEint | ΔVelstat | ΔEoi | ΔEPauli | ΔEdisp | ΔEsum | ΔEsyn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other −C(sp3)–X | |||||||

| CIKTOH59 | –10.20 | –8.81 | –6.58 | 20.14 | –14.95 | –10.30 | 0.10 |

| Simple Benzene Derivatives | |||||||

| PUZHIB0543 | –8.69 | –5.60 | –4.59 | 13.64 | –12.15 | –8.83 | 0.14 |

| Aromatic Heterocycle Derivatives | |||||||

| INEPIA60 | –9.56 | –7.83 | –5.77 | 18.55 | –14.51 | –9.58 | 0.02 |

| NABVIV14 | –6.44 | –5.62 | –3.91 | 9.27 | –6.17 | –6.22 | –0.22 |

| Nonsymmetrical Aromatic Derivatives | |||||||

| BUSFOM61 | –12.38 | –12.58 | –8.97 | 25.94 | –16.77 | –12.56 | 0.18 |

| COCDED62 | –14.13 | –10.12 | –8.59 | 24.10 | –19.51 | –15.44 | 0.11 |

| COCGEH63 | –4.14 | –6.80 | –4.99 | 14.45 | –6.80 | –4.16 | 0.02 |

| FEDSEN64 | –15.08 | –10.49 | –7.14 | 20.80 | –18.25 | –15.21 | 0.13 |

| PAXREM65 | –12.17 | –11.21 | –8.09 | 24.07 | –16.95 | –12.16 | –0.01 |

| Aromatic Derivatives of 3-Fold Symmetry | |||||||

| DEMCEE66 | –6.79 | –5.23 | –3.16 | 10.86 | –9.25 | –6.60 | –0.19 |

| GAPCAC67 | –5.74 | –4.72 | –3.46 | 9.70 | –7.26 | –5.67 | –0.07 |

| PEHGEP68 | –5.29 | –8.66 | –5.69 | 16.50 | –7.44 | –5.25 | –0.04 |

| QOLWET69 | –5.58 | –7.06 | –4.74 | 14.24 | –8.02 | –5.47 | –0.11 |

| QOLWIX69 | –5.75 | –6.25 | –4.26 | 12.46 | –7.70 | –5.67 | –0.08 |

Computed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level.

Table 3. Analysis of Interaction Energies in I3 Motifs Found in Crystal Structures from the CSD (in kcal mol–1).a.

| refcode | ΔEint | ΔVelstat | ΔEoi | ΔEPauli | ΔEdisp | ΔEsum | ΔEsyn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Alkane Derivatives | |||||||

| IODOFO0444 | –10.91 | –17.62 | –11.92 | 34.99 | –16.36 | –9.86 | –1.05 |

| Simple Benzene Derivatives | |||||||

| HIBENZ1170 | –18.45 | –14.43 | –12.64 | 30.73 | –22.10 | –18.42 | –0.03 |

| ISAWIK71 | –10.18 | –10.82 | –8.24 | 21.21 | –12.33 | –9.98 | –0.20 |

| SAQZOY018 | –10.92 | –8.81 | –6.50 | 18.61 | –14.21 | –10.94 | 0.02 |

| UCENOG014 | –16.11 | –14.03 | –11.94 | 29.56 | –19.70 | –15.95 | –0.16 |

| UCEPAU4 | –12.79 | –11.97 | –9.01 | 24.20 | –16.01 | –12.59 | –0.31 |

| Aromatic Heterocycle Derivatives | |||||||

| BOWRUC0272 | –6.66 | –14.61 | –9.53 | 30.17 | –12.68 | –6.37 | –0.29 |

| Nonsymmetrical Aromatic Derivatives | |||||||

| QODRUW73 | –26.46 | –19.09 | –12.01 | 40.19 | –35.54 | –26.19 | –0.27 |

| TONVUP74 | –4.58 | –4.95 | –3.60 | 10.06 | –6.09 | –8.03 | 0.07 |

| XOGVOF0175 | –11.79 | –11.18 | –8.28 | 23.94 | –16.27 | –11.37 | –0.42 |

| Aromatic Derivatives of 3-Fold Symmetry | |||||||

| GANZUR67 | –7.95 | –9.62 | –6.29 | 17.66 | –9.71 | –7.65 | –0.30 |

| GAPBUV67 | –7.90 | –10.29 | –6.57 | 18.88 | –9.92 | –7.56 | –0.34 |

| LEFXEA76 | –15.23 | –12.54 | –8.92 | 24.51 | –18.28 | –15.09 | –0.14 |

Computed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level.

The interaction energies collected in Tables 1–3 exhibit a large variety in strengths from the 44 diverse crystal structures, as could be expected. For most of the structures (13 from among 17) containing the Cl3 motif, ΔEint values are in the interval −8.56 (ROFHUP56 refcode, a nonsymmetrical aromatic derivative) to −2.72 kcal mol–1 (VEWJIQ24 refcode, an aromatic derivative of 3-fold symmetry). Energy decomposition analysis (EDA)42 results reveal that these chlorine–chlorine bonded trimers of all types are stabilized mainly due to dispersion (ΔEdisp). Interaction energy values in polychlorinated fullerenes exhibit significantly lower interaction energies: from −41.64 kcal mol–1 (CARROE45 refcode) to −30.56 kcal mol–1 (VODWOB57 refcode). However, it is important to note that in polychlorinated fullerene trimers there are more Cl···Cl contacts than just the ones forming the Cl3 motif. As a consequence these numerous Cl···Cl interactions in chlorinated fullerenes lead to much stronger stabilization of such trimers than in systems of other types. This stabilization is particularly dominated by the dispersion term: e.g., in the case of the Cl3 motif present in the structure with CARROE45 refcode (ΔEint = −41.64 kcal mol–1) the value of the dispersion energy is −64.29 kcal mol–1, while other stabilizing components are ΔVelstat = −24.59 kcal mol–1 and ΔEoi = −12.38 kcal mol–1. Among structures containing the Cl3 motif, there is one (XAXCOQ0149 refcode, belonging to a group of simple alkane derivatives) in which Cl···Cl interactions are not stabilizing (ΔEint = 1.16 kcal mol–1). This is due to the fact that in the chloroethane trimer (XAXCOQ0149 refcode) Pauli repulsion (ΔEPauli = 10.17 kcal mol–1) surpasses the sum of stabilizing interactions (of which dispersion is the most meaningful, amounting to −4.41 kcal mol–1).

For structures containing the Br3 motif, all interaction energy values are in the range −15.08 (FEDSEN64 refcode) to −4.14 kcal mol–1 (COCGEH63 refcode), both structures containing trimers of nonsymmetrical aromatic derivatives. There is no correlation between the group a system belongs to and the interaction energy value, but the interaction energy is connected with the number and type of interactions between monomers forming the X3 synthon. For example, the trimer of lowest interaction energy present in the structure with the FEDSEN64 refcode is stabilized not only due to three Br···Br contacts forming the Br3 motif but also due to another Br···Br type II contact (shown in Figure 6). Similarly to systems containing the Cl3 motif, also for trimers containing the Br3 motif, dispersion is an important stabilizing factor but is less pronounced in this case. Interestingly, in one of the structures, with PEHGEP68 refcode (an aromatic derivative of 3-fold symmetry), Coulomb attraction (ΔVelstat = −8.66 kcal mol–1) dominates the dispersion term (ΔEdisp = −7.44 kcal mol–1), the latter being stronger than the orbital interactions (ΔEoi = −5.69 kcal mol–1). It should be pointed that the structure with the PEHGEP68 refcode is an exception amidst all bromine-containing aromatic derivatives of 3-fold symmetry.

Figure 6.

X3 motif found in the crystal structure of 1,2,4,5,7-pentabromo-6-methoxyindane. The green dotted line denotes an additional Br ···Br contact.

Structures containing the I3 motif exhibit behavior similar to that found in the trimers with the Br3 motif. Interaction energy values for the I3 containing systems are in the range −26.46 kcal mol–1 (QODRUW73 refcode) to −4.58 kcal mol–1 (TONVUP74 refcode). Interestingly, both structures displaying these two outermost values belong to the same group of nonsymmetrical aromatic derivatives, but the I3 motif in the QODRUW73 structure is additionally stabilized by O–H···O hydrogen bonds between the neighboring monomers. Also in the case of simple benzene derivatives one finds differences between interaction energy values: e.g., −18.45 kcal mol–1 in HIBENZ1170 vs −10.18 kcal mol–1 in ISAWIK.71 Again, the better stabilization of HIBENZ1170 stems from additional interactions between the monomers: namely, additional halogen–halogen bonding occurring in this structure. In structures containing the I3 motif, dispersion is still important for the stability of the studied systems, but for most structures its values are comparable to the values of other stabilizing factors (the differences between these values are significantly smaller than in the case of the systems containing the Cl3 motif, for which the dispersion term appears crucial).

The variety of all 44 chemical compounds forming the X3 synthon in the crystal state is large, and this diversity is reflected in ΔEint values. However, when one takes into account ΔEsyn values, it appears that structures containing Cl3 and Br3 motifs have an important common feature: for all these trimers ΔEsyn values (Tables 1 and 2) are practically negligible, which means that there is no cooperativity when a triangular synthon is formed from three type II halogen–halogen contacts. In the case of the third group of compounds, these containing the I3 motif, the cooperativity is also negligible (ΔEsyn > −0.40 kcal mol–1) for all but two investigated structures; among the systems containing the I3 motif, there are two systems exhibiting weak cooperativity. These findings are in line with the results obtained previously for 16 simple model systems.27 At this point it is important to stress that neither tribromomesitylene (PUZHIB0543 refcode) nor triiodomesitylene (SAQZOY018 refcode) trimers, which have been described as “made up of three cooperative halogen–halogen interactions”,8 do not display any cooperativity according to our computations. Among the crystal structures containing the I3 synthon the iodoform trimer (crystal structure with IODOFO04 refcode44) is the one for which cooperativity is most pronounced (but still weak); for (CHI3)3 ΔEsyn amounts to −1.05 kcal mol–1, and this constitutes about 10% of the total interaction energy in the trimer. When considering the synergy in halogen–halogen bonded systems, one should remember that for these types of systems cooperativity was proven to stem mainly from orbital interactions. Moreover, a linear relationship between the HOMO–LUMO energy gap size diminishment and interaction cooperativity was found for halogen-bonded clusters of halomethanes and haloamines.13 The dependence of synergic effects on energy gaps between accepting and donating orbitals explains why the cooperativity occurs (or does not occur) in halogen–halogen bonded oligomeric systems.13

The I3 Motif in the Iodoform Crystal Structure—The System with the Strongest Interaction Synergy

The iodoform crystal structure with the IODOFO04 refcode44 was determined under nonstandard conditions. The X-ray measurements were performed at room temperature but at a high pressure of 2.15 GPa.44 As expected, under such conditions molecules are usually packed much closer than those under standard conditions, which results in much smaller interatomic distances and also the intramolecular distances (the C–I bond length amounts to 2.12 Å and the I···I distance is 3.738 Å for the IODOFO04 structure). A similar situation is observed for the IODOFO0344 structure determined at a pressure of 0.85 GPa (I···I distance of 3.818 Å). In turn, another iodoform crystal structure (IODOFO02) determined at the standard pressure but at low temperature (106 K)77 displays the longest interatomic distances (the C–I bond length equals 2.14 Å, and the I···I distance is 3.872 Å). In the cases of measurements carried out at lower temperatures, as well as at a lower pressure, the cooperative effects are weaker: −0.49 kcal mol–1 in the case of a model system of the IODOFO02 refcode and −0.69 kcal mol–1 in the case of the IODOFO03 refcode (more data for these two structures are available in Tables S6 and S7 in the Supporting Information). Therefore, the interaction synergy in these three cases is connected with the I···I interatomic distance: for IODOFO04 the distance amounts to 3.738 Å, for IODOFO02 the distance is 3.872 Å, and for IODOFO03 the distance is 3.818 Å, and so the shorter the distance, the stronger the cooperative effects.

Since the (CHI3)3 cluster (the IODOFO04 refcode) exhibits the largest cooperativity among structures found in the CSD, we decided to investigate this case in detail. To verify whether the presence of other molecules may affect cooperativity in a particular synthon (calculations in this study were carried out for isolated trimers), we performed calculations not only for (CHI3)3 but also for [(CHI3)3]3—a trimer formed from three trimers shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

I3 synthon (blue triangle), surrounded by three other I3 synthons (green triangles).

Because (CHI3)3 and [(CHI3)3]3 both have a 3-fold symmetry, the pairwise interactions in these systems, ΔEij, are equal to each other and one may introduce the term ΔEpair:

| 3 |

The results of analysis of interaction energies of (CHI3)3 and [(CHI3)3]3 are collected in Table 4. These two model systems do not exhibit any significant difference in cooperativity. This means that the presence of other iodoform molecules in [(CHI3)3]3 does not amplify the cooperative effects occurring in the considered I3 synthon.

Table 4. Analysis of Interaction Energies of (CHI3)3 and [(CHI3)3]3 (in kcal mol–1)a.

| system | ΔEint | ΔEsum | ΔEsyn | ΔEpair |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (CHI3)3 | –10.91 | –9.86 | –1.05 | –3.28 |

| [(CHI3)3]3 | –11.27 | –10.28 | –0.99 | –3.43 |

Refcode: IODOFO04. Computed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level.

This result allows us to focus on interactions in the isolated iodoform trimer, since the presence of more iodoform monomers does not enhance the synergy in the particular I3 synthon. The source of cooperativity, as well as the source of pairwise interactions, can both be traced if the interaction energies are decomposed into physically meaningful terms according to eq 2. A stepwise formation of the trimer, when each time one monomer is added to the system, allows revealing the source of cooperativity and the nature of the I···I bond itself. The results of EDA collected in Table 5 refer to the situation in which first a dimer, (CHI3)2, is formed and then another iodoform molecule is added to the dimer to form a trimer, (CHI3)2 + (CHI3). Thus, ΔEint in the case of (CHI3)2 + (CHI3) describes a situation in which the iodoform dimer interacts with another iodoform molecule.

Table 5. Energy Decomposition Analysis for the Stepwise Formation of Iodoform Trimer (in kcal mol–1)a.

| (CHI3) + (CHI3) | (CHI3)2 + (CHI3) | ΔEsyn | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔEint | –3.28 | –7.62 | –1.05 |

| ΔVelstat | –5.87 | –11.55 | 0.19 |

| ΔEoi | –3.80 | –8.19 | –0.59 |

| ΔEPauli | 11.84 | 23.03 | –0.65 |

| ΔEdisp | –5.45 | –10.91 | –0.01 |

Refcode: IODOFO04. Computed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level.

The EDA results show that the weak cooperativity found in the I3 synthon present in the iodoform trimer stems equally from attractive orbital interactions and from a reduction in Pauli repulsion when the third iodoform molecule is added to the dimer. The pattern of energy decomposition components for synergy differs from that found in the case of halogen–halogen bonded haloamine tetramers, for which the cooperativity (substantially larger in the latter case) arose from orbital interactions and was additionally enhanced by electrostatic interactions.13 Also when one compares the results obtained for (CHI3)2 with the result for interaction synergy, it occurs that the source of cooperativity is different from the source of the interaction in a dimer (ΔEpair = −3.28 kcal mol–1). According to the results collected in Table 5, a pairwise I···I interaction arises almost equally from electrostatic (−5.87 kcal mol–1) and dispersion (−5.45 kcal mol–1) terms, and these terms are predominant in this case. Also the attractive orbital interactions stabilize the dimer, but stabilization due to polarization and charge-transfer interactions is weaker, amounting to −3.80 kcal mol–1.

Interactions in the X3 Synthon with the X···X Distance Set to the Sum of van der Waals Radii

As mentioned in the Experimental Section, the X···X distance in systems investigated in this study was shorter than the sum of van der Waals radii of the corresponding X atoms. And here the question occurs of how the X···X distance reflects in interaction energies (and their components) of the halogen–halogen bonded trimers and whether the short distance straightforwardly implies stronger bonding in the X3 synthon. We decided to calculate the interaction energies of the 44 studied model systems but with the X···X distance constrained to the sum of van der Waals radii (values estimated by Bondi78). The results of this analysis are presented in Tables 6–8.

Table 6. Analysis of Interaction Energies (in kcal mol–1)a in Cl3 Motifs Found in Crystal Structures from the CSD with Cl···Cl Distances Set to the Sum of van der Waals Radii.

| refcode | ΔEint | ΔVelstat | ΔEoi | ΔEPauli | ΔEdisp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Alkane Derivatives | |||||

| HEXCET1446 | –8.23 | –8.31 | –3.88 | 19.24 | –15.28 |

| NUXJUM0447 | –4.88 | –5.36 | –2.39 | 12.49 | –9.62 |

| UNUYOT0448 | –6.40 | –4.85 | –2.74 | 10.40 | –9.22 |

| XAXCOQ0149 | 0.14 | –0.53 | –1.51 | 5.98 | –3.80 |

| Other −C(sp3)–X | |||||

| EREQAT50 | –8.08 | –4.67 | –2.35 | 9.54 | –10.60 |

| NIVSIW51 | –4.83 | –2.85 | –1.84 | 8.03 | –8.18 |

| UXIYOQ0252 | –5.16 | –3.57 | –1.89 | 7.65 | –7.35 |

| Aromatic Heterocycle Derivatives | |||||

| XAXTUL53 | –6.00 | –5.18 | –3.04 | 13.58 | –11.37 |

| Nonsymmetrical Aromatic Derivatives | |||||

| ISURUL54 | –8.89 | –6.27 | –3.04 | 14.18 | –13.76 |

| MEQBOA55 | –8.30 | –3.79 | –2.66 | 9.50 | –11.35 |

| ROFHUP56 | –8.43 | –4.26 | –3.30 | 10.28 | –11.15 |

| Aromatic Derivatives of 3-Fold Symmetry | |||||

| VALQEE0116 | –2.81 | –2.08 | –1.61 | 6.01 | –5.13 |

| VEWJIQ24 | –2.83 | –2.09 | –1.61 | 6.01 | –5.14 |

| XEHMAY22 | –3.16 | –2.25 | –1.60 | 6.42 | –5.72 |

| Fullerene Derivatives | |||||

| CARROE45 | –41.36 | –20.19 | –10.22 | 49.21 | –60.15 |

| VODWOB57 | –30.10 | –14.20 | –8.36 | 35.13 | –42.67 |

| YEFNII58 | –33.07 | –9.81 | –6.03 | 25.89 | –43.11 |

Computed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level.

Table 8. Analysis of Interaction Energies in I3 (in kcal mol–1)a Motifs Found in Crystal Structures from the CSD with I···I Distances Set to the Sum of van der Waals radii.

| refcode | ΔEint | ΔVelstat | ΔEoi | ΔEPauli | ΔEdisp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Alkane Derivatives | |||||

| IODOFO0444 | –11.69 | –10.40 | –7.44 | 20.66 | –14.44 |

| Simple Benzene Derivatives | |||||

| HIBENZ1170 | –17.90 | –11.78 | –10.12 | 24.54 | –20.54 |

| ISAWIK71 | –9.86 | –6.42 | –5.20 | 12.53 | –10.77 |

| SAQZOY018 | –10.80 | –7.31 | –5.55 | 15.53 | –13.47 |

| UCENOG014 | –15.78 | –9.16 | –8.21 | 19.14 | –17.56 |

| UCEPAU4 | –12.68 | –8.90 | –6.79 | 17.79 | –14.78 |

| Aromatic Heterocycle Derivatives | |||||

| BOWRUC0272 | –7.57 | –6.10 | –4.49 | 13.28 | –10.26 |

| Nonsymmetrical Aromatic Derivatives | |||||

| QODRUW73 | –26.04 | –17.92 | –11.12 | 37.58 | –34.59 |

| TONVUP74 | –8.32 | –6.87 | –5.11 | 12.83 | –9.17 |

| XOGVOF0175 | –11.86 | –7.77 | –6.20 | 17.10 | –14.99 |

| Aromatic Derivatives of 3-Fold Symmetry | |||||

| GANZUR67 | –7.88 | –7.23 | –4.81 | 13.34 | –9.17 |

| GAPBUV67 | –7.95 | –7.29 | –4.82 | 13.28 | –9.13 |

| LEFXEA76 | –14.60 | –8.01 | –5.97 | 15.63 | –16.24 |

Computed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level.

Table 7. Analysis of Interaction Energies (in kcal mol–1)a in Br3 Motifs Found in Crystal Structures from the CSD with Br···Br Distances Set to the Sum of van der Waals Radii.

| refcode | ΔEint | ΔVelstat | ΔEoi | ΔEPauli | ΔEdisp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other −C(sp3)–X | |||||

| CIKTOH59 | –10.78 | –6.24 | –5.10 | 14.89 | –14.33 |

| Simple Benzene Derivatives | |||||

| PUZHIB0543 | –8.63 | –4.69 | –4.05 | 11.63 | –11.52 |

| Aromatic Heterocycle Derivatives | |||||

| INEPIA60 | –9.62 | –7.01 | –5.30 | 16.69 | –14.01 |

| NABVIV14 | –6.38 | –4.59 | –3.15 | 7.13 | –5.76 |

| Nonsymmetrical Aromatic Derivatives | |||||

| BUSFOM61 | –12.55 | –10.80 | –7.88 | 22.17 | –16.03 |

| COCDED62 | –15.28 | –8.72 | –7.14 | 19.18 | –18.61 |

| COCGEH63 | –4.83 | –3.39 | –2.85 | 7.15 | –5.73 |

| FEDSEN64 | –14.71 | –8.49 | –6.02 | 16.96 | –17.17 |

| PAXREM65 | –12.07 | –7.35 | –5.93 | 16.12 | –14.91 |

| Aromatic Derivatives of 3-Fold Symmetry | |||||

| DEMCEE66 | –6.83 | –4.60 | –2.87 | 9.60 | –8.96 |

| GAPCAC67 | –5.72 | –3.99 | –3.07 | 8.31 | –6.97 |

| PEHGEP68 | –5.75 | –4.15 | –3.08 | 7.66 | –6.17 |

| QOLWET69 | –5.73 | –3.99 | –3.09 | 8.33 | –6.98 |

| QOLWIX69 | –5.79 | –4.07 | –3.07 | 8.27 | –6.92 |

Computed at the ZORA-BLYP-D3(BJ)/TZ2P level.

A comparison between the corresponding interaction energy values collected in Tables 5–8 and those in Tables 1–3 indicates that there is no straightforward relation between the change in X···X distances and the interaction energies of the halogen–halogen bonded trimers. For most of the studied systems, elongation of the X···X distance does not make any significant change either in the interaction energy or in its components (e.g., the structure with the GAPCAC67 refcode). A few structures displaying larger stabilization at halogen–halogen distances being a sum of van der Waals radii (the effect is close to 1.00 kcal mol–1 for four structures with the following refcodes: XAXCOQ01,49 HEXCET14,46 BOWRUC02,72 and IODOFO0444) were measured at high pressure. These results suggest that a short distance (shorter than the sum of van der Waals radii) between halogen atoms is not a simple indicator of a significantly increased interaction strength in the X3 synthon. However, it should be noted that the differences between interaction energies in most of the trimers do not exceed 0.50 kcal mol–1.

Conclusions

The hypothesis, based on the structural data, that cooperativity of interactions occurs in the halogen–halogen bonded X3 synthon was proposed in papers devoted to crystal structures containing the X3 motif. The interaction energy analysis performed in this study revealed the lack of cooperativity in Cl3 and Br3 synthons present in crystal structures. All but two systems containing the I3 halogen-bonded motif also did not exhibit any synergy in the interaction energy; only a (very) weak cooperativity occurred in two I3 motifs. From among the systems exhibiting any synergy the iodoform trimer, found in the crystal structure measured at high pressure (2.15 GPa), was the one in which the cooperativity was most pronounced but it amounted only to −1.05 kcal mol–1 (about 10% of the total interaction energy). This value was traced back to an equal amount of increased orbital interactions and to a reduction in Pauli repulsion when a trimer is formed. This value remained practically constant for a particular synthon when other iodoform molecules were added to the system, and so the presence of more iodoform molecules did not enhance interaction cooperativity in the I3 synthon.

In the iodoform dimer with the geometry of the studied trimer (taken from the crystal structure), pairwise interactions of the two molecules were stabilized mainly by electrostatic and dispersion components. Attractive orbital interactions also increased the stability of iodoform pairs, but this effect was weaker than in the case of electrostatic and dispersive interactions.

Interestingly, an interaction energy analysis of the trimers revealed that short halogen–halogen contacts (shorter than the sum of van der Waals radii) were not a straightforward indicator of a significantly increased stability of the X3 motif. For structures measured at high pressure this stability was slightly (about 1 kcal mol–1) decreased with a shorter distance.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported within the Project HPC-EUROPA3 (INFRAIA-2016-1-730897), with the support of the EC Research Innovation Action under the H2020 Programme (contract ID HPC17QP0HF, J.D.), by the National Science Centre of Poland (OPUS grant no. 2015/19/B/ST4/01773; A.J.R.-P.), and by The Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (NWO-CW, NWO-EW; C.F.G.). Calculations were carried out using the computer resources and technical support provided by the SARA centre and by the Wrocław Centre for Networking and Supercomputing (grant no. 118). Access to HPC machines and licensed software is gratefully acknowledged by J.D.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.cgd.0c01410.

Refcodes, X3 motifs, and compound names for 64 hits from the CSD search, X···X distances and X···X···X angle values for 64 CSD hits, and interaction energy analysis results for 20 crystal structures which are not included in the main body of the article (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Desiraju G. R.; Parthasarathy R. The nature of halogen··· halogen interactions: are short halogen contacts due to specific attractive forces or due to close packing of nonspherical atoms?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 8725–8726. 10.1021/ja00205a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A.; Tothadi S.; Desiraju G. R. Halogen bonds in crystal engineering: like hydrogen bonds yet different. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2514–2524. 10.1021/ar5001555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui T. T. T.; Dahaoui S.; Lecomte C.; Desiraju G. R.; Espinosa E. The nature of halogen···halogen interactions: a model derived from experimental charge-density analysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3838–3841. 10.1002/anie.200805739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy C. M.; Kirchner M. T.; Gundakaram R. C.; Padmanabhan K. A.; Desiraju G. R. Isostructurality, Polymorphism and Mechanical Properties of Some Hexahalogenated Benzenes: The Nature of Halogen···Halogen Interactions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2006, 12, 2222–2234. 10.1002/chem.200500983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrangolo P.; Resnati G. Type II halogen···halogen contacts are halogen bonds. IUCrJ 2014, 1, 5–7. 10.1107/S205225251303491X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju G. R.; Ho P. S.; Kloo L.; Legon A. C.; Marquardt R.; Metrangolo P.; Politzer P.; Resnati G.; Rissanen K. Definition of the halogen bond (IUPAC Recommendations 2013). Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 1711–1713. 10.1351/PAC-REC-12-05-10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo G.; Metrangolo P.; Milani R.; Pilati T.; Priimagi A.; Resnati G.; Terraneo G. The Halogen Bond. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (4), 2478–2601. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch E.; Barnes C. L. Triangular Halogen-Halogen-Halogen Interactions as a Cohesive Force in the Structures of Trihalomesitylenes. Cryst. Growth Des. 2002, 2, 299–302. 10.1021/cg025517w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherington J. B.; Moncrief J. W. The crystal and molecular structure of anti- α-bromoacetophenone oxime. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1973, 29, 1520–1525. 10.1107/S056774087300484X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters L. P.; Smits N. W. G.; Fonseca Guerra C. Covalency in resonance-assisted halogen bonds demonstrated with cooperativity in N-halo-guanine quartets. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 1585–1592. 10.1039/C4CP03740E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J.; Deringer V. L.; Dronskowski R. Cooperativity of Halogen, Chalcogen, and Pnictogen Bonds in Infinite Molecular Chains by Electronic Structure Theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 3193–3200. 10.1021/jp5015302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatyev I. S.; Partal F.; González J. J. L. Effect of the Silyl Substitution on Structure and Vibrational Spectra of Hydrogen-Bonded Networks in Dimers, Cyclic Trimers, and Tetramers. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 11644–11652. 10.1021/jp0217233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dominikowska J.; Bickelhaupt F. M.; Palusiak M.; Fonseca Guerra C. Source of Cooperativity in Halogen-Bonded Haloamine Tetramers. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 474–480. 10.1002/cphc.201501130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkonen J.; Pitkänen I.; Pajunen A. Molecular and Crystal Structure and IR Spectrum of 3,5-Dibromo-1,2,4-triazole. Acta Chem. Scand. 1985, 39a, 711–716. 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.39a-0711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wzgarda-Raj K.; Rybarczyk-Pirek A. J.; Wojtulewski S.; Palusiak M. N-Oxide-N-oxide interactions and Cl···Cl halogen bonds in pentachloropyridine N-oxide: the many-body approach to interactions in the crystal state. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2018, 74, 113–119. 10.1107/S2053229617017922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony A.; Desiraju G. R.; Jetti R. K. R.; Kuduva S. S.; Madhavi N. N. L.; Nangia A.; Thaimattam R.; Thalladi V. R. Crystal Engineering: Some Further Strategies. Cryst. Eng. 1998, 1, 1–18. 10.1016/S0025-5408(98)00031-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silly F. Concentration-Dependent Two-Dimensional Halogen-Bonded Self-Assembly of 1,3,5-Tris(4-iodophenyl)benzene Molecules at the Solid-Liquid Interface. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 10413–10418. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b02091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrot D.; Silly M. G.; Silly F. Temperature-Triggered Sequential On-Surface Synthesis of One and Two Covalently Bonded Porous Organic Nanoarchitectures on Au(111). J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 26815–26821. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b08296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrot D.; Silly M. G.; Silly F. X3 synthon geometries in two-dimensional halogen-bonded 1,3,5-tris(3,5-dibromophenyl)-benzene self-assembled nanoarchitectures on Au(111)-(22× 3). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 3918–3924. 10.1039/C7CP06488H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezgunova M. E.; Aubert E.; Dahaoui S.; Fertey P.; Lebègue S.; Jelsch C.; Ángyán J. G.; Espinosa E. Charge Density Analysis and Topological Properties of Hal3-Synthons and Their Comparison with Competing Hydrogen Bonds. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 5373–5386. 10.1021/cg300978x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy C. M.; Kirchner M. T.; Gundakaram R. C.; Padmanabhan K. A.; Desiraju G. R. Isostructurality, Polymorphism and Mechanical Properties of Some Hexahalogenated Benzenes: The Nature of Halogen···Halogen Interactions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2006, 12, 2222–2234. 10.1002/chem.200500983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broder C. K.; Howard J. A. K.; Keen D. A.; Wilson C. C.; Allen F. H.; Jetti R. K. R.; Nangia A.; Desiraju G. R. Halogen trimer synthons in crystal engineering: low-temperature X-ray and neutron diffraction study of the 1:1 complex of 2,4,6-tris(4-chloro-phenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine with tribromobenzene. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 2000, 56, 1080–1084. 10.1107/S0108768100011551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetti R. K. R.; Xue F.; Mak T. C. W.; Nangia A. 2,4,6-tris-4-(bromophenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine: a hexagonal host framework assembled with robust Br···Br trimer synthons. Cryst. Eng. 1999, 2, 215–224. 10.1016/S1463-0184(00)00020-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jetti R. K. R.; Thallapally P. K.; Xue F.; Mak T.C. W.; Nangia A. Hexagonal Nanoporous Host Structures Based on 2,4,6-Tris-4-(halo-phenoxy)-1,3,5-triazines (Halo = Chloro, Bromo). Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 6707–6719. 10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00491-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha B. K.; Aitipamula S.; Banerjee R.; Nangia A.; Jetti R. K. R.; Boese R.; Lam C.-K.; Mak T. C. W. Hexagonal Host Framework of sym-Aryloxytriazines Stabilised by Weak Intermolecular Interactions. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2005, 440, 295–316. 10.1080/15421400590958601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dominikowska J. Halogen-bonded haloamine trimers - modelling the X3 synthon. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 21938–21946. 10.1039/D0CP03352A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.; Zou J.; Wang H.; Yu Q.; Zhang H.; Jiang Y. Triangular Halogen Trimers. A DFT Study of the Structure, Cooperativity, and Vibrational Properties. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 11956–11961. 10.1021/jp0547360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groom C. R.; Bruno I. J.; Lightfoot M. P.; Ward S. C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171–179. 10.1107/S2052520616003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters L. P.; Bickelhaupt F. M. Halogen Bonding versus Hydrogen Bonding: A Molecular Orbital Perspective. ChemistryOpen 2012, 1, 96–105. 10.1002/open.201100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen F. H.; Bruno I. J. Bond lengths in organic and metal-organic compounds revisited: X—H bond lengths from neutron diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 2010, 66, 380–386. 10.1107/S0108768110012048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 1988, 38, 3098–3100. 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miehlich B.; Savin A.; Stoll H.; Preuss H. Results obtained with the correlation energy density functionals of Becke and Lee, Yang and Parr. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989, 157, 200–206. 10.1016/0009-2614(89)87234-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Anthony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D.; Johnson E. R. A density-functional model of the dispersion interaction. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 154101. 10.1063/1.2065267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G. Relativistic total energy using regular approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 9783–9792. 10.1063/1.467943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; van Leeuwen R.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G. Relativistic regular two-component Hamiltonians. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1996, 57, 281–293. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ADF 2018; SCM, Theoretical Chemistry, Vrije Universiteit: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; http://www.scm.com.

- te Velde G.; Bickelhaupt F. M.; van Gisbergen S. J. A.; Fonseca Guerra C.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G.; Ziegler T. Chemistry with ADF. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 931–967. 10.1002/jcc.1056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca Guerra C.; Snijders J. G.; Te Velde G.; Baerends E. J. Towards an order-N DFT method. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1998, 99, 391–403. 10.1007/s002140050353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bickelhaupt F. M.; Baerends E. J. In Reviews in Computational Chemistry; Lipkowitz K. B., Boyd D. B., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2000; Vol. 15, pp 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Saraswatula V. G.; Saha B. K. A thermal expansion investigation of the melting point anomaly in trihalomesitylenes. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 9829–9832. 10.1039/C5CC03033A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti F.; Curetti N.; Benna P.; Gervasio G. The effects of P-T changes on intermolecular interactions in crystal structure of iodoform. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1041, 106–112. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2013.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.; Wei T.; Kemnitz E.; Troyanov S. I. The Most Stable IPR Isomer of C88 Fullerene, Cs-C88 (17), Revealed by X-ray Structures of C88Cl16 and C88Cl22. Chem. - Asian J. 2012, 7, 290–293. 10.1002/asia.201100759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujak M.; Podsiadło M.; Katrusiak A. Loose crystals engineered by mismatched halogen bonds in hexachloroethane. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 328–333. 10.1039/C7CE01980G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bujak M.; Katrusiak A. Molecular association in low-temperature and high-pressure polymorphs of 1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 1263–1268. 10.1039/B918360D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bujak M.; Podsiadło M.; Katrusiak A. Halogen and hydrogen bonds in compressed pentachloroethane. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 5393–5397. 10.1039/C6CE01025C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadło M.; Bujak M.; Katrusiak A. Chemistry of density: extension and structural origin of Carnelley’s rule in chloroethanes. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 4496–4500. 10.1039/c2ce25097g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seregin I. V.; Ovchinnikov I. V.; Makhova N. N.; Lyubetsky D. V.; Lyssenko K. A. An unexpected transformation of 3,4-diacylfuroxans into 3-acyl-4-acylaminofurazans in the reaction with nitriles. Mendeleev Commun. 2003, 13, 230–232. 10.1070/MC2003v013n05ABEH001811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G.; Gadhe C. G.; Park S.-W.; Kim K. S.; Kang J.; Seema H.; Singh N. J.; Cho S. J. Novel Ionophores with 2n-Crown-n Topology: Anion Sensing via Pure Aliphatic C-H···Anion Hydrogen Bonding. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 334–337. 10.1021/ol402819m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelbrich T.; Rossi D.; Griesser U. J. Tetragonal polymorph of 5,5-dichloro-barbituric acid. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2012, 68, o235–o236. 10.1107/S1600536811054626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch D. E.; McClenaghan I. 4,6-Di-chloro-2-(methyl-thio)-pyrimidine. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2000, 56, e536 10.1107/S0108270100014190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht A.; Skrzynska A.; Pietrzak A.; Bojanowski J.; Albrecht L. Asymmetric Aminocatalysis in the Synthesis of δ-Lactone Derivatives. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5, 1115–1119. 10.1002/ajoc.201600272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen X.-L.; Han J.-R.; Wang Q.-T.; Tian X.; Liu S.-X. 4-(2,4-Dichlorobenzyloxy)-3-methoxybenzaldehyde. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2006, 62, o5794–o5795. 10.1107/S1600536806049671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rakitin O. A.; Rees C. W.; Williams D. J.; Torroba T. Cyclopenta-1,2-dithioles, Cyclopenta-1,2-thiazines, and Methylenoindenes from New Molecular Rearrangements. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 9178–9185. 10.1021/jo9612234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonov K. S.; Amsharov K. Yu.; Krokos E.; Jansen M. An Epilogue on the C78-Fullerene Family: The Discovery and Characterization of an Elusive Isomer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6283–6285. 10.1002/anie.200801922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.; Wei T.; Kemnitz E.; Troyanov S. I. Four isomers of C96 fullerene structurally proven as C96Cl22 and C96Cl24. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8239–8242. 10.1002/anie.201201775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeb N. V.; Zindel D.; Schweizer W. B.; Lienemann P. 2,5,6,9,10-Pentabromocyclododecanols (PBCDOHs): A new class of HBCD transformation products. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 655–662. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo F.; Yin C.; Guo W.; Xia C.; Yang P. Methyl 4-bromo-1,3-di-methyl-pyrazole-5-carboxyl-ate. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2003, 59, o2013–o2014. 10.1107/S160053680302525X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan M. M.; Wanas A. S.; Fronczek F. R.; Jacob M. R.; Ross S. A. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers from the marine organisms Lendenfeldia dendyi and Sinularia dura with anti-MRSa activity. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 3398–3404. 10.1007/s00044-015-1386-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson J.; Eriksson L.; Jakobsson E. Deca-bromodi-phenyl ether. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1999, 55, 2169–2171. 10.1107/S0108270199008884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sukach V. A.; Golovach N. M.; Pirozhenko V. V.; Rusanov E. B.; Vovk M. V. Convenient enantioselective synthesis of β-trifluoromethyl-β-aminoketones by organocatalytic asymmetric Mannich reaction of aryl trifluoromethyl ketimines with acetone. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 761–764. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akkurt M.; Celik I.; Berkil K.; Tutar A.; Ersanli C. C.; Cakmak O.; Buyukgungor O. (1RS,2SR)-1,2,4,5,7-Penta-bromo-5-meth-oxy-Indane. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2005, 61, o475–o477. 10.1107/S160053680500111X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois J.-M.; Stoeckli-Evans H. Synthesis of New Resorcinarenes Under Alkaline Conditions. Helv. Chim. Acta 2005, 88, 2722–2730. 10.1002/hlca.200590211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Jiang H.-Q.; Li X.-M.; Zhang S.-S. 2,4,6-Tris(2,4,6-tri-bromo-phen-oxy)-1,3,5-triazine. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2006, 62, o3303–o3304. 10.1107/S1600536806026134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha B. K.; Jetti R. K. R.; Reddy L. S.; Aitipamula S.; Nangia A. Halogen Trimer-Mediated Hexagonal Host Framework of 2,4,6-Tris(4-halophenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine. Supramolecular Isomerism from Hexagonal Channel (X = Cl, Br) to Cage Structure (X = I). Cryst. Growth Des. 2005, 5, 887–899. 10.1021/cg049691r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naydenov B.; Spudat C.; Harneit W.; Suss H. I.; Hulliger J.; Nuss J.; Jansen M. Ordered inclusion of endohedral fullerenes N@C60 and P@C60 in a crystalline matrix. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 424, 327–332. 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.04.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jetti R. K. R.; Nangia A.; Xue F.; Mak T. C. W. Polar host-guest assembly mediated by halogen···π interaction: inclusion complexes of 2,4,6-tris(4-halophenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine (halo = chloro, bromo) with trihalobenzene (halo = bromo, iodo). Chem. Commun. 2001, 919–920. 10.1039/b102150h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S.; Reddy C. M.; Desiraju G. R. Hexa-iodo-benzene: a redetermination at 100 K. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2007, 63, o910–o911. 10.1107/S1600536807002279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein T.; Hoffmann F.; Wenzel F.; Froba M.. 1,3-Dichloro-2-iodobenzene. CSD Communication, 2016.

- Rajewski K. W.; Andrzejewski M.; Katrusiak A. Competition between Halogen and Hydrogen Bonds in Triiodoimidazole Polymorphs. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 3869–3874. 10.1021/acs.cgd.6b00436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anelli P. L.; Brocchetta M.; Maffezzoni C.; Paoli P.; Rossi P.; Uggeri F.; Visigalli M. Syntheses and X-ray crystal structures of derivatives of 2,2’,4,4’,6,6’-hexaiodobiphenyl. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 10, 1175–1181. 10.1039/b009666k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M.; Murata Y.; Yagishita F.; Sakamoto M.; Sengoku T.; Yoda H. Catalytic Enantioselective Amide Allylation of Isatins and Its Application in the Synthesis of 2-Oxindole Derivatives Spiro-Fused to the α-Methylene-γ-Butyrolactone Functionality. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 11091–11100. 10.1002/chem.201403357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howie R. A.; Wardell J. L.. 2-Nitrophenylthio-2-iodophenylamine. CSD Communication, 2008.

- Barba V.; Villamil R.; Luna R.; Godoy-Alcantar C.; Hopfl H.; Beltran H. I.; Zamudio-Rivera L. S.; Santillan R.; Farfan N. Boron Macrocycles Having a Calix-Like Shape. Synthesis, Characterization, X-ray Analysis, and Inclusion Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 2553–2561. 10.1021/ic051850o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti F.; Gervasio G. Crystal structure of iodoform at 106 K and of the adduct CHI3·3(C9H7N). Iodoform as a building block of co-crystals. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1036, 305–310. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi A. Van der Waals Volumes and Radii. J. Phys. Chem. 1964, 68, 441–451. 10.1021/j100785a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.