Hyperphosphatemia is a prevalent complication in patients with advanced CKD, affecting approximately 50% of those treated with maintenance hemodialysis (1,2). In the normal state, phosphate homeostasis is maintained through the interplay between intestinal absorption, bone deposition, soft tissue transport, and kidney excretion, along with regulation by hormones, including parathyroid hormone (PTH), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25[OH]2D), and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). However, in advanced CKD, decreased kidney excretion coupled with disordered mineral metabolism (increases in PTH and FGF23, reductions in 1,25[OH]2D synthesis and gastrointestinal calcium absorption) engender hyperphosphatemia, leading to vascular calcification and stiffness, altered cardiac structure and function, kidney osteodystrophy, and heightened mortality.

Dietary phosphate is the predominant source of hyperphosphatemia and is found in two forms (organic versus inorganic sources). Organic sources include animal- versus plant-based phosphate, which have varying degrees of bioavailability (40%–60% versus 20%–40%, respectively) (3). In addition to evidence suggesting salutary effects of plant-based diets (decreased CKD progression, uremic toxin modulation, reduced cardiovascular risk) (4), plant-based phosphate sources, which largely occur in the form of phytates, have lower bioavailability because of a lack of the degrading enzyme phytase in humans (3). In a crossover trial of patients with stage 3 and 4 CKD, 1 week of a vegetarian diet led to lower serum phosphate, phosphaturia, and FGF23 levels than meat-based protein diets (5). A crossover study in healthy adults, using a whole-foods approach, also found that habitual ingestion of low phosphatemic index foods largely from plant-based sources led to decreased PTH and FGF23 levels, and increased 1,25(OH)2D levels, compared with high phosphatemic index foods with equivalent amounts of phosphate (6). In contrast, inorganic phosphate sources, typically found in additives of processed foods, have >90% bioavailability (3). Although additives have a number of benefits, including enhancement of food shelf-life, color, flavor, and moisture, they are under-reported in food labels and disproportionately contribute to dietary phosphate burden.

The cornerstones of hyperphosphatemia management include dietary interventions, removal by dialysis, and pharmacotherapies (phosphate binders, calcimimetics). Conventional thrice-weekly hemodialysis provides limited phosphate removal relative to the dietary phosphate intake of patients on dialysis (6300–10,500 mg/wk, on average) (7). Furthermore, the high pill burden of patients on dialysis (median 19 pills/d, with phosphate binders accounting for half of daily pill burden [8]) has been associated with poor adherence, higher serum phosphate levels, and impaired health-related quality of life (8). Hence, dietary therapy plays a critical role in achieving target phosphate levels. The 2020 National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guidelines for Nutrition in CKD recommend that patients with stages 3A–5D CKD adjust their dietary phosphate intake to maintain serum phosphate in the normal range (GRADE evidence 1B), and to consider the bioavailability of phosphate sources (OPINION) (1). In lieu of recommending specific dietary phosphate ranges, they advise “individualiz[ing] treatments based on patient needs and clinical judgment,” and that implementation requires nutrition expertise, preferably from a kidney dietitian, to adequately evaluate patients’ daily intake and provide recommendations.

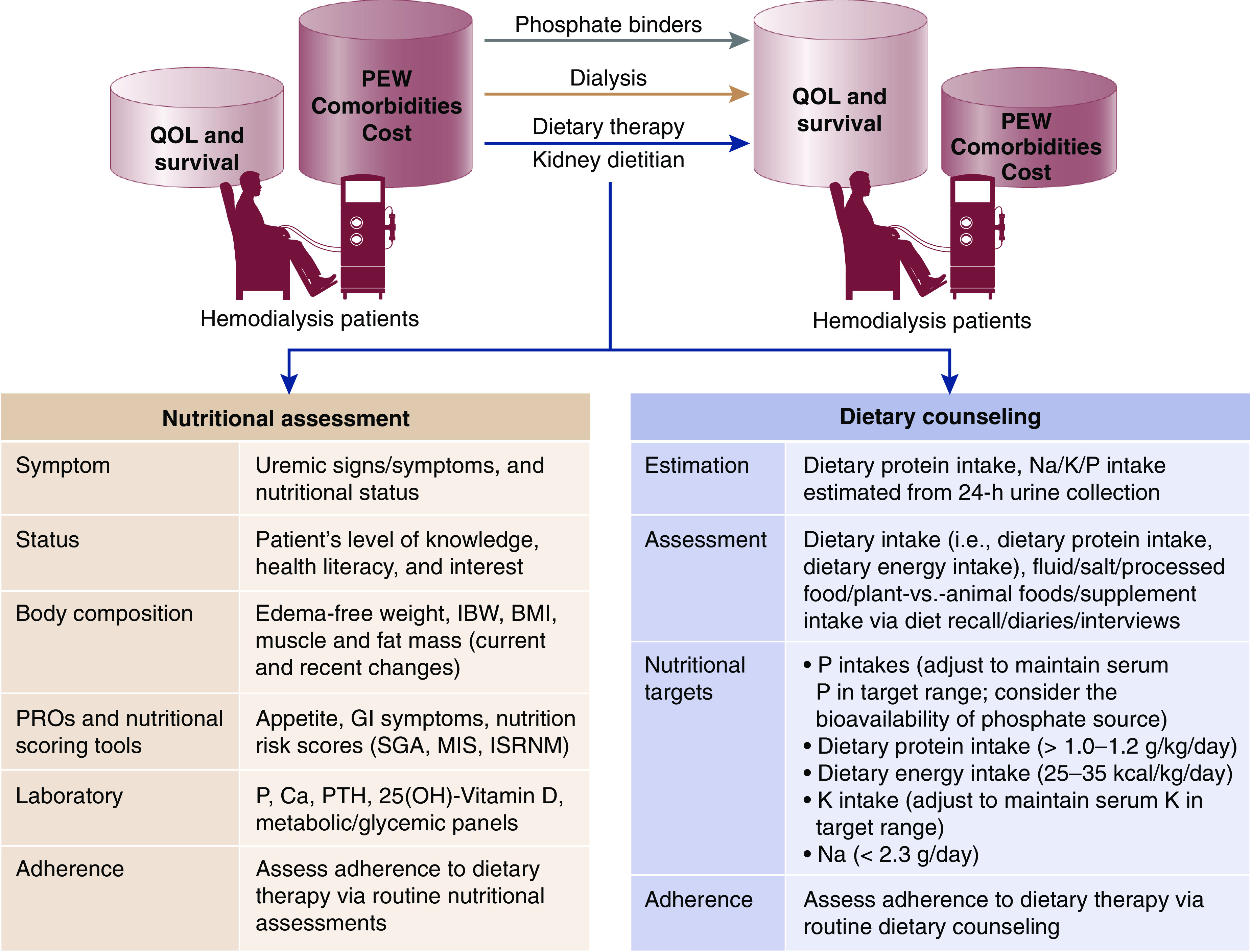

Currently, dialysis units in the United States are mandated to provide medical nutrition therapy (MNT) services, which encompass individualized nutrition assessment, care planning, and dietary education provided by a registered dietitian nutritionist (9). Dietary interventions, including routine dietary assessment, dietary phosphate restriction, education on reading food labels, and meal preparation with demineralization methods, are core components of hyperphosphatemia management (Figure 1). Although dietitians contribute substantial time and effort in providing tailored nutrition therapy to patients on hemodialysis, the efficacy and safety of phosphate-specific dietary interventions delivered by dietitians on hyperphosphatemia management has remained unclear.

Figure 1.

The cornerstones of hyperphosphatemia management in hemodialysis patients include dietary interventions, dialytic removal, and pharmacotherapies. Core components of tailored dietary therapy in hemodialysis patients include routine nutritional assessment and dietary counseling administered by dietitians. BMI, body mass index; Ca, Calcium; GI, gastrointestinal; IBW, ideal body weight; ISRNM, International Society of Renal Nutrition and Metabolism; K, potassium; MIS, malnutrition-inflammation score; Na, sodium; P, phosphate; PTH, parathyroid hormone; PEW, protein energy wasting; PROs, patient-reported outcomes; QOL, quality of life; SGA, subjective global assessment.

In this issue of CJASN, St-Jules et al. (2) conducted the first systematic review and meta-analysis examining the effects of phosphate-specific diet therapy provided by dietitians and/or providers with equivalent qualifications versus standard of care on nutrition outcomes in adult patients on hemodialysis. Studies deemed eligible for synthesis included 12 clinical trials (11 randomized and one nonrandomized) conducted over 2000–2019 across an international catchment (United States, South America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East), which were categorized according to (1) intervention focus (multicomponent versus targeted interventions), and (2) intervention “dose” (frequency of sessions) in the multicomponent studies. Across nine studies examining multicomponent interventions, two trials of low-dose (single session) diet therapy demonstrated nonsignificant decreases in serum phosphate (mean difference −0.45 mg/dl), whereas two out of three moderate-dose (one session every 1 to 1.5 months) and three out of four high-dose (more than one session per month) trials showed significant decreases in serum phosphate (mean differences −0.87 mg/dl and −0.78 mg/dl, respectively), although these reductions were unlikely to be sustained if discontinued. Among three studies examining targeted interventions, two trials that focused on avoidance of phosphate additives demonstrated significant decreases in serum phosphate (mean difference −1.18 mg/dl), whereas one trial that focused on meal preparations did not observe significant differences. Pooled analysis of 11 trials with adequate data showed that diet therapy significantly decreased serum phosphate versus controls (mean difference −0.77 mg/dl). Notably, no ill effects of diet therapy on patients’ nutritional and protein indices, body composition, physical function, or health-related quality of life were observed.

This study adds important knowledge to the field by (1) demonstrating the efficacy of phosphate-specific diet therapy administered by dietitians in lowering serum phosphate, and (2) confirming the safety of these interventions on nutritional and patient-centered end points. In addition to affirming the critical importance of dietitians in multidisciplinary hyperphosphatemia management, this study also underscores the need for frequent, ongoing administration of individualized diet therapy to achieve and maintain improvements in persistent phosphate control. Although the authors acknowledged the heterogeneity of the interventions across trials, this study emphasizes the value of utilizing combinations of dietary strategies (low-phosphate diet, avoidance of phosphate additives, training in meal preparation) with nondietary strategies (binder and dialysis adherence, pharmacist consultation) in achieving phosphate control. As epidemiologic data have not shown that dietary phosphate restriction per se improves survival in patients on hemodialysis (10), using multicomponent approaches may also avert concerns and risk of excessively limiting dietary phosphate intake at the cost of dietary protein intake.

Several limitations should also be considered when interpreting the study’s findings. First, although practice guidelines recommend routine dietary assessment in the nutritional management of CKD (1), availability of information on the methods of assessment and the effects of the interventions on participants’ phosphate intake were sparsely reported across the trials. Second, variable serum phosphate enrollment criteria across the trials (such that several trials enrolled patients with normal baseline serum phosphate levels) may have diluted the potential observed effect of the dietary interventions on phosphate improvement. Third, although the effects of the interventions on serum phosphate levels and adverse events were followed for up to a maximum of 12 and 3 months, respectively, in the included trials, further studies examining the long-term efficacy/effectiveness and safety of phosphate-specific dietary therapy are needed.

It also bears mention that diet is a modifiable factor in the health and survival of patients with CKD, which may be delivered at low cost. Although MNT administered by a registered dietitian nutritionist is cost-effective in the management of diabetes, hypertension, and the elderly population, there have been a paucity of studies examining the potential cost-savings of MNT in patients with CKD (9). Given the high prevalence of mineral bone disease contributing to the disproportionate burden of cardiovascular disease, skeletal complications, and death in patients on hemodialysis, this study is an important contribution to summarizing existing evidence on the nutritional management of hyperphosphatemia and the essential role of dietitians in caring for this population, as well as the need for future rigorous research in this area.

Disclosures

C.M. Rhee reports receiving research funding from Dexcom Inc.; receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Fresenius, Nutricia, Ostuka, Reata, and Roche; and serving as a scientific advisor or member of BMC Nephrology, CardioRenal, CJASN, Hemodialysis International, Journal of Renal Nutrition, and Kidney International. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

The authors are supported by the Uehara Memorial Foundation for Overseas Postdoctoral Fellowships (Y. Narasaki), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases research grants R03-DK114642 (C.M. Rhee), R01-DK122767 (C.M. Rhee), and R01-DK124138 (C.M. Rhee).

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the author(s) and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related article, “Effect of Phosphate-Specific Diet Therapy on Phosphate Levels in Adults Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” on pages 107–120.

References

- 1.Ikizler TA, Burrowes JD, Byham-Gray LD, Campbell KL, Carrero JJ, Chan W, Fouque D, Friedman AN, Ghaddar S, Goldstein-Fuchs DJ, Kaysen GA, Kopple JD, Teta D, Yee-Moon Wang A, Cuppari L: KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in CKD: 2020 update [published correction appears in Am J Kidney Dis S0272-6386(20): 31125–2, 2020 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.11.004]. Am J Kidney Dis 76[Suppl 1]: S1–S107, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.St-Jules DE, Rozga MR, Handu D, Carrero JJ: Effect of phosphate-specific diet therapy on phosphate levels in adults undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 107–120, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Gutekunst L, Mehrotra R, Kovesdy CP, Bross R, Shinaberger CS, Noori N, Hirschberg R, Benner D, Nissenson AR, Kopple JD: Understanding sources of dietary phosphorus in the treatment of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 519–530, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Joshi S, Schlueter R, Cooke J, Brown-Tortorici A, Donnelly M, Schulman S, Lau WL, Rhee CM, Streja E, Tantisattamo E, Ferrey AJ, Hanna R, Chen JLT, Malik S, Nguyen DV, Crowley ST, Kovesdy CP: Plant-dominant low-protein diet for conservative management of chronic kidney disease. Nutrients 12: 1931, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moe SM, Zidehsarai MP, Chambers MA, Jackman LA, Radcliffe JS, Trevino LL, Donahue SE, Asplin JR: Vegetarian compared with meat dietary protein source and phosphorus homeostasis in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 257–264, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narasaki Y, Yamasaki M, Matsuura S, Morinishi M, Nakagawa T, Matsuno M, Katsumoto M, Nii S, Fushitani Y, Sugihara K, Noda T, Yoneda T, Masuda M, Yamanaka-Okumura H, Takeda E, Sakaue H, Yamamoto H, Taketani Y: Phosphatemic index is a novel evaluation tool for dietary phosphorus load: A whole-foods approach. J Ren Nutr 30: 493–502, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waheed AA, Pedraza F, Lenz O, Isakova T: Phosphate control in end-stage renal disease: Barriers and opportunities. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2961–2968, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu YW, Teitelbaum I, Misra M, de Leon EM, Adzize T, Mehrotra R: Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1089–1096, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer H, Jimenez EY, Brommage D, Vassalotti J, Montgomery E, Steiber A, Schofield M: Medical nutrition therapy for patients with non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease: Barriers and solutions. J Acad Nutr Diet 118: 1958–1965, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch KE, Lynch R, Curhan GC, Brunelli SM: Prescribed dietary phosphate restriction and survival among hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 620–629, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]