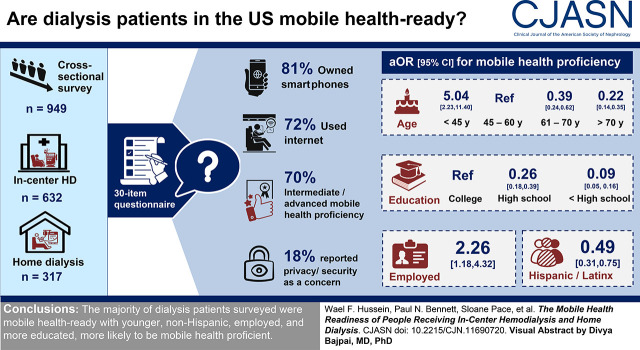

Visual Abstract

Keywords: end stage kidney disease, hemodialysis, mHealth, mobile health, telehealth, telemedicine

Abstract

Background and objectives

Mobile health is the health care use of mobile devices, such as smartphones. Mobile health readiness is a prerequisite to successful implementation of mobile health programs. The aim of this study was to examine the status and correlates of mobile health readiness among individuals on dialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A cross-sectional 30-item questionnaire guided by the Khatun mobile health readiness conceptual model was distributed to individuals on dialysis from 21 in-center hemodialysis facilities and 14 home dialysis centers. The survey assessed the availability of devices and the internet, proficiency, and interest in using mobile health.

Results

In total, 949 patients (632 hemodialysis and 317 home dialysis) completed the survey. Of those, 81% owned smartphones or other internet-capable devices, and 72% reported using the internet. The majority (70%) reported intermediate or advanced mobile health proficiency. The main reasons for using mobile health were appointments (56%), communication with health care personnel (56%), and laboratory results (55%). The main reported concerns with mobile health were privacy and security (18%). Mobile health proficiency was lower in older patients: compared with the 45- to 60-years group, respondents in age groups <45, 61–70, and >70 years had adjusted odds ratios of 5.04 (95% confidence interval, 2.23 to 11.38), 0.39 (95% confidence interval, 0.24 to 0.62), and 0.22 (95% confidence interval, 0.14 to 0.35), respectively. Proficiency was lower in participants with Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity (adjusted odds ratio, 0.49; 95% confidence interval, 0.31 to 0.75) and with less than college education (adjusted odds ratio for “below high school,” 0.09; 95% confidence interval, 0.05 to 0.16 and adjusted odds ratio for “high school only,” 0.26; 95% confidence interval, 0.18 to 0.39). Employment was associated with higher proficiency (adjusted odds ratio, 2.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.18 to 4.32). Although home dialysis was associated with higher proficiency in the unadjusted analyses, we did not observe this association after adjustment for other factors.

Conclusions

The majority of patients on dialysis surveyed were ready for, and proficient in, mobile health.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number: Dialysis mHealth Survey,

Introduction

Technology is constantly advancing, affecting all aspects of health care. The US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Healthy People 2020 Midcourse Review report highlighted the United States’ goal to “use health communication strategies and health information technology to improve population health outcomes and health care quality, and to achieve health equity” (1). Progress toward this goal has seen people with health care needs use mobile devices to access their medical information, track and receive reminders of their appointments and medications, and participate in virtual visits with their providers (2).

Mobile health, also known as mHealth, has been defined by the World Health Organization as medical and public health practice through the use of mobile devices, such as mobile phones, patient monitoring devices, personal digital assistants, and other wireless devices (3). In interventional studies, mobile health has demonstrated improvement in patient-reported outcome measures (4), reduced use of health resources (5), and cost savings to health care services (6). In dialysis care, mobile health has been used to assist diet monitoring (7–10), treatment and symptom monitoring (11), and lifestyle management (12–14). These uses are promising; however, what is not clear is how ready people on dialysis are to use mobile health for their everyday health care.

Mobile health readiness is a crucial prerequisite to the successful implementation of mobile health programs. Mobile health technological readiness has been most widely recognized through the Technology Acceptance Model of attitudes, usefulness, and ease of use (15). Khatun et al. (16) adapted these elements to the three domains of technological readiness, resource readiness, and motivational readiness. With this background, we adapted the work of Khatun et al. (16) to mobile health in the dialysis context, formulating three domains of mobile health readiness: (1) technological readiness, referring to availability of the infrastructure that would enable use of mobile health; (2) proficiency in using the technology; and (3) motivational readiness, referring to trust in the technology and the willingness to use mobile health.

Little is known about the status and correlates of technological readiness, proficiency, and motivational readiness in the US dialysis population. Studies in the general population have identified the willingness of people to use mobile health in the United States and across the world (17–20). A US non-nephrology study exploring mobile health readiness in older individuals receiving health care reported high levels of access to mobile health devices and the internet, with 60% of respondents using mobile devices and the internet for health information (21). In those with chronic health conditions, device ownership is high (22,23) and attitudes are positive (24), with a willingness to replace face-to-face physician visits with mobile health (25).

Two small US peritoneal dialysis surveys found that the majority of people on peritoneal dialysis reported owning a mobile phone (83%–94%), had internet access (90%), and were willing to use telehealth (73%–83%) (26,27). Similarly, in a small qualitative hemodialysis study of younger patients, the majority owned smartphones and were interested in using mobile health (14). An Australian survey of people with CKD reported that increased mobile health readiness was positively associated with education and negatively associated with age and identifying as indigenous (28). Similarly, in kidney transplant recipients, mobile health willingness is high and is lower with older age (29,30).

A review of mobile health readiness literature reveals that US studies in the dialysis population have generally been small or did not include participants receiving in-center dialysis. Therefore, in this study, we examined the status and correlates of mobile health readiness among individuals receiving in-center dialysis and home dialysis.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We administered a cross-sectional survey in November and December 2019 to patients on dialysis from 21 in-center hemodialysis centers and 14 home dialysis centers in California, Texas, and Tennessee managed by one medium-sized nonprofit dialysis provider. Participants were English- and Spanish-speaking patients aged 18 years and older. Patients were excluded if they were cognitively impaired or suffering an active psychologic condition, asleep, or not on shift, or if the dialysis staff indicated to the surveyors to not approach them. For in-center hemodialysis facilities, surveyors targeted defined time periods that enabled access to all dialysis schedules.

Survey Development and Administration

We assessed mobile health technological readiness by adapting the previously developed survey of Bonner et al. (28) guided by the mobile health readiness conceptual model by Khatun et al. (16). Questions were developed to assess mobile health technological readiness, proficiency, and mobile health motivational readiness. The questionnaire was reviewed by ten dialysis professionals to assess suitability for purpose and appropriateness for target audience. The instrument was then pilot tested with a sample of ten patients to assess suitability before administration during the study. Minor revisions were made following expert and user recommendations. Translation and translation verification of the questionnaire from English to Spanish were provided by a certified native-speaking translator from an external professional translation organization. The final 30-item questionnaire is presented as Supplemental Material.

For surveys of patients on in-center hemodialysis, seven surveyors were trained on introducing the study, obtaining verbal consent, and administering the surveys. Reasons for nonparticipation were recorded. For patients on home dialysis, center clinical staff invited patients to complete the survey during the time that patients visited the center for regular monthly care. Waiver of signed consent was approved on the condition that limited personal and identifiable information was being collected. The study was approved by Aspire Independent Review Board and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04177277.

Study Variables and Definitions

We collected patient characteristics (age group; sex identity; whether Hispanic, Latinx, or not; whether Black or not; primary language; insurance; highest education level; employment status and dialysis modality [in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, or peritoneal dialysis]) to enable description of study participants and identification of factors associated with readiness for mobile health use. Primary language spoken was subsequently converted to English, Spanish, or other. Dialysis modality was converted to in-center hemodialysis or home dialysis (home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis). A minority of respondents indicating “currently student” are included in “currently employed” for a single variable “currently employed or student.”

We assessed mobile health readiness in three domains: (1) technological readiness, (2) proficiency in using the technology, and (3) motivational readiness. To assess technological readiness, the availability of internet and devices and the use of internet were evaluated. For those using the internet, we evaluated the frequency and whether assistance was required. For those not using the internet, we explored their reasons. Availability of devices necessary to access mobile health was evaluated by asking whether the participant owned or had access to a device. A binary (yes/no) “technological readiness” variable was constructed to indicate if the participant had a capable device and access to the internet.

We assessed various elements of internet or device users that we converted to three levels of proficiency: basic use (phone calls and text messages only), intermediate use (video calls, email, photos, videos, online media, social media, internet articles/news, alarms, reminders, maps, directions, or calendar), and advanced use (internet shopping, personal health information, planning and tracking, booking travel or entertainment, banking, or online payments). Each participant was assigned to the highest level of activity he or she reported performing. For those not able to use mobile health, we recorded the reasons of inability (literacy, eyesight, dexterity, or other). After data review, patients were grouped into two categories: the nonproficient group comprised basic users and nonusers, and the proficient group comprised intermediate and advanced users. We used this binary grouping of proficiency to study the associations with different factors using logistic regression.

We assessed motivational readiness by recording whether participants were currently performing different types of mobile health activities or if they had interest in undertaking these activities. For each activity, a binary “motivational readiness” variable was constructed to indicate whether a participant was currently using or interested in using any of the listed mobile health–related activities.

Statistical Analyses

We reported the distribution of baseline characteristics for the whole group, for patients on in-center dialysis, and for patients on home dialysis. Baseline characteristics of all patients in participating centers are provided as Supplemental Table 1. We reported descriptive statistics for variables in the technological readiness, proficiency, and motivation domains. We investigated the effect of demographic and social factors on proficiency using unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression. Independent variables for the regression analysis were identified a priori: state (California versus non-California), age groups, sex (woman versus man), ethnicity (Hispanic or Latinx versus not), race (Black versus not), educational level, employment (employed or student versus not), modality (home dialysis versus in-center dialysis), and insurance (commercial insurance versus not). We reported the odd ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each variable. We only performed complete patient analysis. The number of missing items was provided for each analysis. For sensitivity analysis, we fitted these regression models separately on cohorts for patients on in-center hemodialysis and for patients on home dialysis. Results were materially similar (not shown). Logistic regression models were fitted for the motivational readiness domain, and results are supplied in Supplemental Material. For all analyses, a P value of 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Study Population

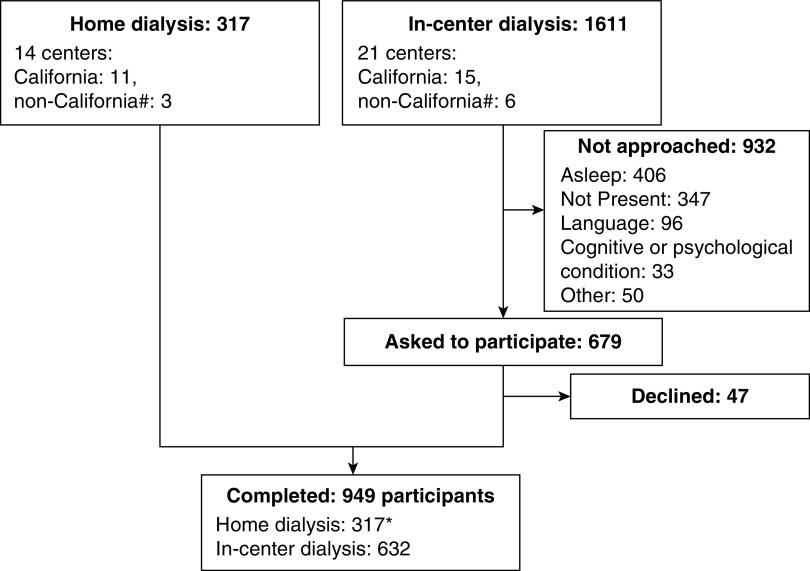

Surveys were completed by 949 patients, consisting of 632 on in-center hemodialysis and 317 on home dialysis. For in-center hemodialysis, 1611 individuals were identified as candidates for the survey. Of those, 679 were approached to participate, and 632 (93%) completed the survey. The majority of patients not approached were asleep or were not present at the center during the time of the survey. Forty-seven individuals declined the invitation to participate (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart: Number of patients in participating centers, individuals approached for participation, and individuals who participated in the survey. *Home dialysis incompletions were not recorded (home dialysis includes peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis); #non-California = Texas and Tennessee.

The most prevalent age group was between 45 and 60 years of age, and 37% of respondents were women. The majority of patients spoke English (80%), and most were publicly insured patients (70%). The majority of patients had some college education (57%), with a large proportion not employed (82%). Compared with the in-center hemodialysis respondents, home dialysis participants had higher proportions of younger patients, employment, and higher education and a lower proportion of Hispanic patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients on dialysis survey participants

| Characteristic | Overall (%) | In-Center Hemodialysis (%) | Home Dialysis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants (row %) | 949 (100) | 632 (67) | 317 (33) |

| California | 770 (81) | 510 (81) | 260 (82) |

| Age group, yr | |||

| Under 45 | 146 (15) | 80 (13) | 66 (21) |

| 45–60 | 305 (32) | 191 (30) | 114 (36) |

| 61–70 | 241 (26) | 180 (29) | 61 (19) |

| Over 70 | 254 (27) | 181 (29) | 73 (23) |

| Women | 348 (37) | 230 (36) | 118 (37) |

| Hispanic or Latinx = yes (“no” group not shown) | 302 (32) | 216 (34) | 86 (27) |

| Black = yes (“no” group not shown) | 181 (19) | 119 (19) | 62 (20) |

| Primary spoken languagea | |||

| English | 758 (80) | 515 (82) | 243 (77) |

| Spanish | 150 (16) | 110 (17) | 40 (13) |

| Other | 77 (8) | 39 (6) | 38 (12) |

| Insurance coverageb | |||

| Medicare | 661 (70) | 445 (70) | 216 (68) |

| Medicaid | 177 (19) | 129 (20) | 48 (15) |

| Commercial | 288 (30) | 209 (33) | 79 (25) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school diploma | 140 (15) | 109 (17) | 31 (10) |

| High school diploma | 261 (28) | 185 (29) | 76 (24) |

| Some college or more | 541 (57) | 337 (53) | 204 (64) |

| Currently employed or student = yes (“no” group not shown) | 171 (18) | 72 (11) | 99 (31) |

Percentages do not add up to 100% as some patients reported more than one primary spoken language.

Percentages do not add up to 100% as some patients have more than one type of coverage. n (column percentage) is shown except for number of participants, where percentage is row percentage. Number of missing values: age group, three; sex, 31; ethnicity, nine; race, 27; and educational level, seven.

Domain 1: Mobile Health Technological Readiness

A high proportion of respondents reported using the internet (72%). Among them, the majority reported using it daily (74%), and 89% of users reported not requiring assistance. Among the small group of nonusers, the most common cause for not using the internet was lack of interest (44%), followed by not knowing how (38%). Respondents from the home dialysis cohort had a higher proportion of internet users compared with in-center dialysis and used it more frequently. The majority of participants reported having a smartphone (81%), with 52% and 51% reporting availability of a laptop computer and a tablet device, respectively. Ten percent of participants had access to a wearable device, such as a watch. More patients on in-center dialysis than patients on home dialysis reported no access to an internet-capable device (10% versus 4%). Seventy percent of patients reported mobile health technological readiness (access to the internet and a capable device). Significantly more of the home dialysis respondents were technologically mobile health ready (78% versus 67%, P<0.001) compared with the in-center group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mobile health technological readiness (in-center hemodialysis and home dialysis)

| Characteristic | Overall | In-Center Hemodialysis | Home Dialysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internet use (yes)a | 686 (72%) | 426 (68%) | 260 (83%) |

| Frequency of internet useb | |||

| Daily | 505 (74%) | 298 (70%) | 207 (80%) |

| More than once weekly | 112 (16%) | 84 (20%) | 28 (11%) |

| Less often | 62 (9%) | 44 (10%) | 18 (7%) |

| Requires assistance to use the internet (yes) | 73 (11%) | 50 (12%) | 23 (9%) |

| Reason for not using the internet,c n | 263 | 206 | 57 |

| Don’t know how | 100 (38%) | 83 (40%) | 17 (30%) |

| Don’t want to | 116 (44%) | 91 (44%) | 25 (44%) |

| No internet-capable device | 28 (11%) | 21 (10%) | 7 (12%) |

| No internet access | 26 (10%) | 19 (9%) | 7 (12%) |

| Other | 14 (5%) | 13 (6%) | 1 (2%) |

| Device availabilitya | |||

| Smartphone | 764 (81%) | 513 (81%) | 251 (79%) |

| Tablet | 481 (51%) | 320 (51%) | 161 (51%) |

| Laptop | 489 (52%) | 321 (51%) | 168 (53%) |

| Desktop | 357 (38%) | 227 (36%) | 130 (41%) |

| Wearable | 94 (10%) | 61 (10%) | 33 (10%) |

| None | 78 (8%) | 65 (10%) | 13 (4%) |

| Technological readiness | 667 (70%) | 421 (67%) | 246 (78%) |

Percentages in this section are from all respondents.

Percentages in this section are from those who reported using the internet.

Percentages in this section are from those who reported not using the internet. N (column percentage) is shown except for internet use (yes), where percentage is row percentage. Number of missing values: internet use, three; frequency of use, ten; need for assistance, ten; and other variables, zero.

Domain 2: Mobile Health Proficiency

Of the patients who used mobile devices, 98% were able to both read and type on their devices. The reported reasons for not being able to read or type included poor eyesight (n=11), literacy (n=1), and dexterity (n=1); 57% of respondents reported advanced mobile health proficiency, with 13% reporting intermediate proficiency and 30% having basic or no proficiency. Home dialysis respondents reported a higher proportion of proficient users (those with intermediate or advanced proficiency as opposed to basic or none) compared with those in the in-center hemodialysis group (77% versus 66%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mobile health proficiency (in-center hemodialysis and home dialysis)

| Characteristic | Overall (%) | In-Center Hemodialysis (%) | Home Dialysis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of proficiency | |||

| None or basic | 289 (30) | 216 (34) | 73 (23) |

| Intermediate or advanced | 660 (70) | 416 (66) | 244 (77) |

Domain 3: Mobile Health Motivation

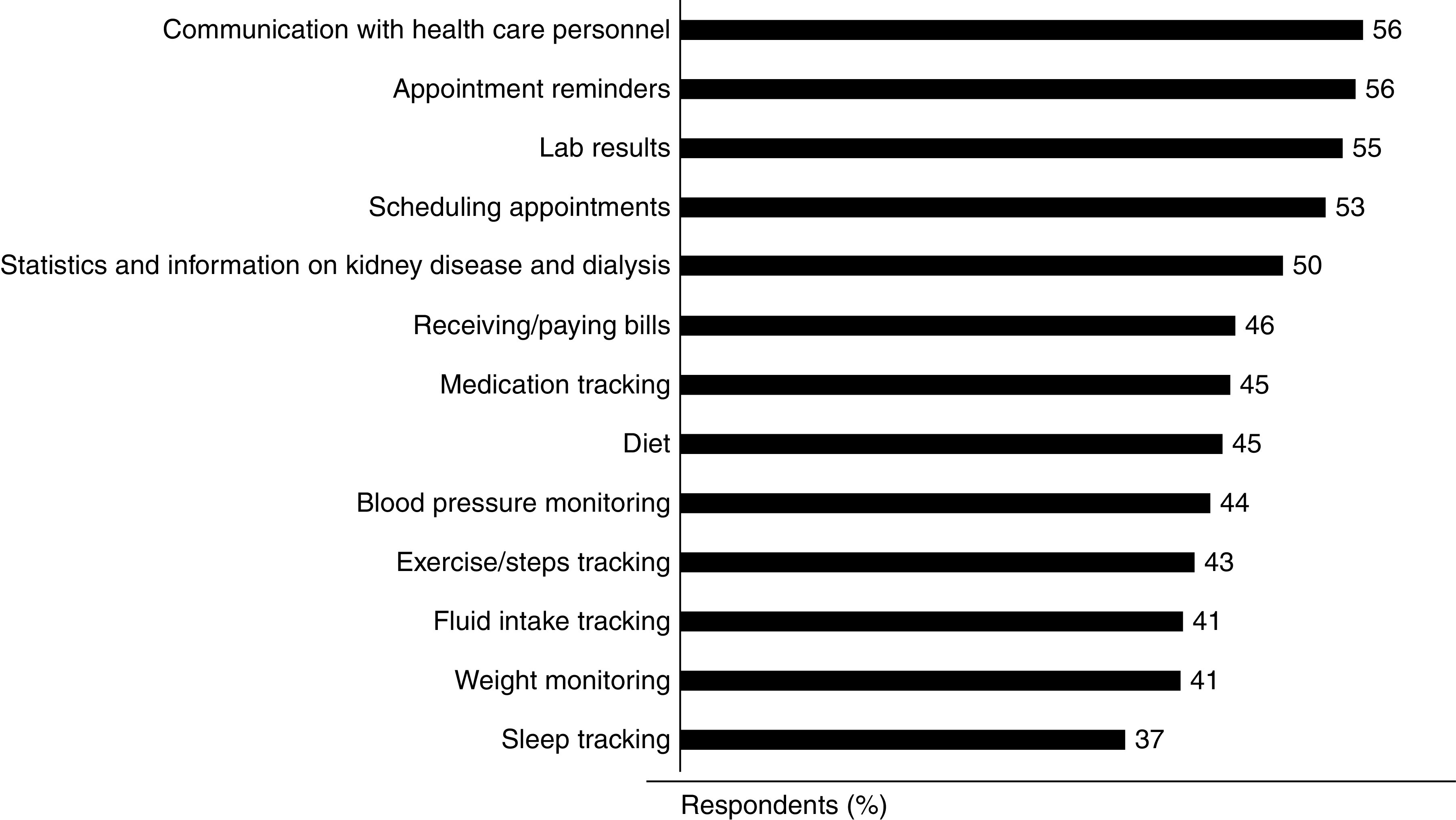

From the total survey respondents, 548 (60%) expressed an interest in using mobile health to learn or engage with their health care. A greater percentage of patients on home dialysis than patients on in-center dialysis expressed this interest (67% versus 56%). Participants reported the most common reasons for mobile health–related activities were health care personnel communication (56%), appointment reminders (56%), laboratory result access (55%), scheduling appointments (53%), statistics and information on kidney disease and dialysis (50%), billing purposes (46%), and medication tracking (45%) (Figure 2). A number of respondents had concerns with privacy and security (18%), cost (6%), and effectiveness (3%).

Figure 2.

Participants indicated they used or intended to use mobile health for a variety of tasks related to health management.

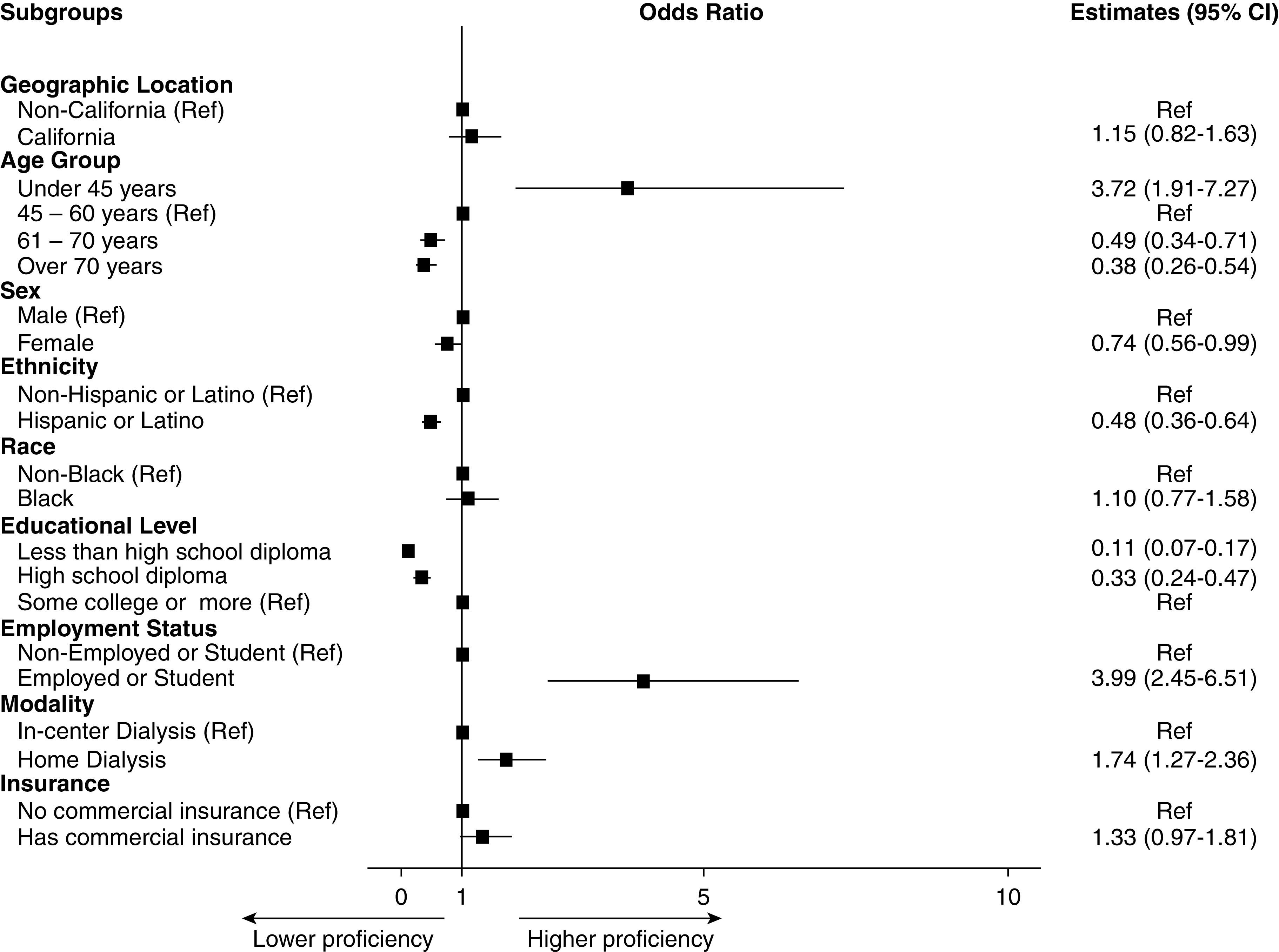

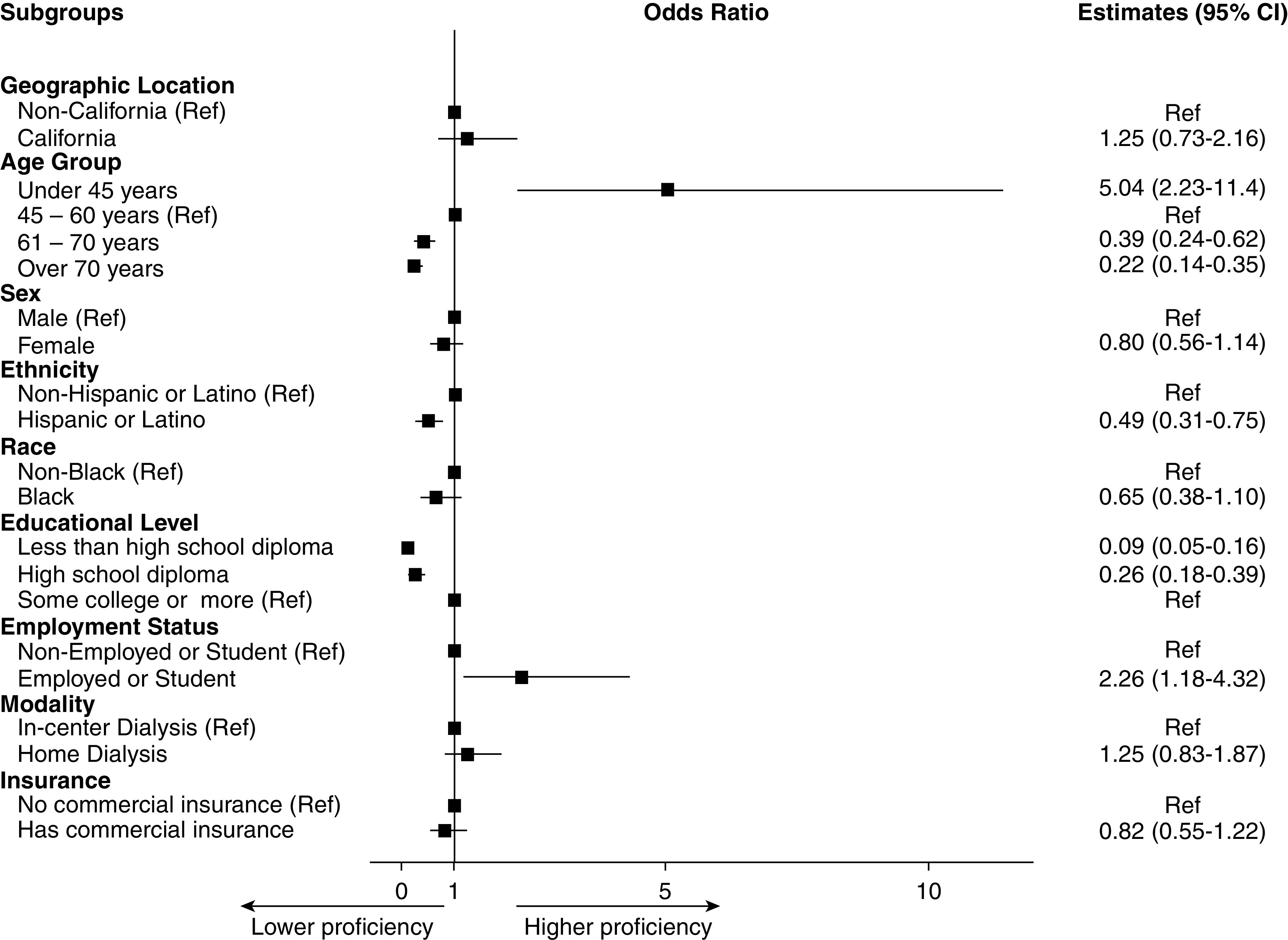

Factors Associated with Level of Proficiency

Figures 3 and 4 show the results of unadjusted and adjusted analyses of correlates of proficiency, respectively (intermediate or advanced level versus none or basic). In unadjusted analysis, age under 45 years, being employed or a student, and being on home dialysis were associated with proficiency, whereas the older age group, women, and being Hispanic or Latinx were associated with low proficiency. In the adjusted model, age group, Hispanic or Latinx, educational level, and employed or student continued to show significant correlation. Sex and dialysis modality were no longer significantly associated with proficiency in the adjusted model. Geographic location (California versus non-California), Black race, and insurance (commercial insurance versus not) were not significantly correlated with proficiency in either analysis.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted associations are shown between participant characteristics and mobile health proficiency. n=949 except for age group (three missing), sex (31 missing), ethnicity (nine missing), race (27 missing), and educational level (seven missing). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref, reference.

Figure 4.

Multivariable associations are shown between participant characteristics and mobile health proficiency. Complete patient analysis, n=891. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref, reference.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study assessing the technological readiness of patients on in-center dialysis and patients on home dialysis in the United States. Among this cohort of 949 adults receiving dialysis, the vast majority reported mobile health readiness, proficiency, and motivation. The majority reported the ability to use mobile devices and to access the internet independently and were currently using or interested in using mobile health–related activities. These findings are consistent with smaller US (14,26) and Australian surveys that found high ownership of mobile phones with mobile health readiness potential (28). The mobile health readiness reflects the recent boom in US mobile phone ownership and internet usage (31), the increased independent use in older adults (32), the increased use in health care (2), and an increase in use in the US kidney disease population over the past 15 years (33,34).

Importantly, our findings suggest that even though the majority of patients on dialysis are mobile health ready, a one-size-fits-all approach to mobile health is unlikely to be successful. Our findings that mobile health readiness is independently associated with younger age, higher education, employment, and ethnicity support previous findings in nondialysis contexts (16,21,35,36). In people with kidney disease, Bonner et al. (28) found that greater mobile health readiness was associated with younger age, higher education, and decreased indigeneity. Targeting mobile health interventions in accordance with the characteristic demographics of the dialysis population is likely to be most effective.

The majority of dialysis mobile health readiness research has focused on people receiving home dialysis. We found higher mobile health readiness and proficiency in our patients on home dialysis compared with patients on in-center dialysis. This important finding can stimulate the use of mobile health in home dialysis given that the vast majority of home dialysis nurses believe that its use would improve care, decrease travel time, and enhance patient-centered care in patients on home dialysis (37).

The use of mobile health for patients on in-center hemodialysis has received less attention than home dialysis, even though technology is highly pervasive in in-center hemodialysis (38). The capacity to improve treatment adherence; address patient-reported symptoms in real time; and encourage the use of nutrition, activity, and mental health apps could assist in empowering patients to reverse the predominantly one-way care delivery system and place the patient on dialysis at the center of his or her own health care.

Although the majority of in-center patients are mobile health ready and proficient, clinicians need to be mindful to assess rather than assume mobile health readiness and take an individual approach in providing mobile health applications and tools (21). This is particularly important given the low quality and low sustainability of some mobile health applications (39–41) and the varied mobile health readiness of older and less educated patients (23,28,29). Furthermore, the knowledge that most users stop mobile health application usage soon after initial use (42–44) suggests a need for additional health care professional education and support to help ensure that mobile health communications can lead to significant improvements in patient experience with home dialysis care (11).

This study has important limitations and strengths. The main limitation is that this is a cross-sectional design, and we cannot propose causal relationship between patient variables and mobile health readiness or proficiency. Convenience sampling, particularly with the large proportion of patients who were asleep or were not available in the center at the time of surveying, is a source of bias. Because we did not have a tracking system to indicate respondents from nonrespondents, we could not compare characteristics of those not included in the study. We, however, provide a table with the baseline characteristics of all patients at participating centers at the time of the study (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). To increase the response rate, we did not include a question about financial status. Further, we did not have access to the data on the participants’ community type (e.g., suburban, urban, or rural). The survey was developed by the researchers, and no instrument psychometric validation process has been undertaken. For home dialysis, we were not able to record invitations to participate or response rate. Our study, however, has multiple strengths. This is the largest survey of its kind exploring mobile health readiness in a contemporary cohort of patients on dialysis across three states in the United States. We examined readiness in terms of infrastructure availability, skill, and interest to engage the tools for health care use. An additional strength is the breadth of patients surveyed, including patients on in-center hemodialysis, patients on home dialysis, and English and Spanish language patients.

In conclusion, the majority of patients on dialysis surveyed across three states in the United States were mobile health ready. Participants who were younger, were non-Hispanic, were employed, or had more education were more likely to be proficient.

Disclosures

J. Atwal, P.N. Bennett, S. Chen, W.F. Hussein, V. Legg, and S. Sun are employees of Satellite Healthcare. B. Schiller is an employee of Satellite Healthcare and also reports consultancy agreements with Akebia and speakers bureau with AstraZeneca. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashley Jiang, Catherine Gray, Sara Oliver, Anna Carrasco, Rebekah McAulay, Dr. Kerstin Leuther, Ian Farwell, Emily Watson, Rory Pace, and Keith Lester for their technical assistance, advice, manuscript preparation, including editorial or clerical assistance from individual persons (e.g., individuals who helped type or proofread the manuscript), and critical review of the manuscript.

J. Atwal, W.F. Hussein, V. Legg, and S. Sun provided the research idea and study design; J. Atwal, V. Legg, and S. Pace provided data acquisition; P.N. Bennett, S. Chen, W.F. Hussein, and S. Sun provided data analysis/interpretation; S. Chen, W.F. Hussein, and S. Sun provided statistical analysis; P.N. Bennett, W.F. Hussein, and B. Schiller provided supervision and mentorship; and all authors provided final manuscript approval.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11690720/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Material. Mobile health technological readiness survey.

Supplemental Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants and the total population in participating centers.

Supplemental Table 2. Logistic regression for motivation to use mobile health among study participants.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics : Health communication and health information technology Healthy People 2020 Midcourse Review, edited by National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics, 2016, pp 17-1-17–14 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramirez V, Johnson E, Gonzalez C, Ramirez V, Rubino B, Rossetti G: Assessing the use of mobile health technology by patients: An observational study in primary care clinics. JMIR mHealth uHealth 4: e41, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization: Global Diffusion of eHealth: Making Universal Health Coverage Achievable. Report of the Third Global Survey on eHealth, Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle N, Murphy M, Brennan L, Waugh A, McCann M, Mellotte G: The “Mikidney” smartphone app pilot study: Empowering patients with chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care 45: 133–140, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dey V, Jones A, Spalding EM: Telehealth: Acceptability, clinical interventions and quality of life in peritoneal dialysis. SAGE Open Med 4: 2050312116670188, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin T: Assessing mHealth: Opportunities and barriers to patient engagement. J Health Care Poor Underserved 23: 935–941, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imtiaz R, Atkinson K, Guerinet J, Wilson K, Leidecker J, Zimmerman D: A pilot study of OkKidney, a phosphate counting application in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 37: 613–618, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olivares-Gandy HJ, Domínguez-Isidro S, López-Domínguez E, Hernández-Velázquez Y, Tapia-McClung H, Jorge de-la-Calleja: A telemonitoring system for nutritional intake in patients with chronic kidney disease receiving peritoneal dialysis therapy. Comput Biol Med 109: 1–13, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch JL, Astroth KS, Perkins SM, Johnson CS, Connelly K, Siek KA, Jones J, Scott LL: Using a mobile application to self-monitor diet and fluid intake among adults receiving hemodialysis. Res Nurs Health 36: 284–298, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stark S, Snetselaar L, Piraino B, Stone RA, Kim S, Hall B, Burke LE, Sevick MA: Personal digital assistant-based self-monitoring adherence rates in 2 dialysis dietary intervention pilot studies: BalanceWise-HD and BalanceWise-PD. J Ren Nutr 21: 492–498, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiberd J, Khan U, Stockman C, Radhakrishnan A, Phillips M, Kiberd BA, West KA, Soroka S, Chan C, Tennankore KK: Effectiveness of a web-based eHealth portal for delivery of care to home dialysis patients: A single-arm pilot study. Can J Kidney Health Dis 5: 2054358118794415, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han M, Williams S, Mendoza M, Ye X, Zhang H, Calice-Silva V, Thijssen S, Kotanko P, Meyring-Wösten A: Quantifying physical activity levels and sleep in hemodialysis patients using a commercially available activity tracker. Blood Purif 41: 194–204, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi A, Yamaguchi S, Waki K, Fujiu K, Hanafusa N, Nishi T, Tomita H, Kobayashi H, Fujita H, Kadowaki T, Nangaku M, Ohe K: Testing the feasibility and usability of a novel smartphone-based self-management support system for dialysis patients: A pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc 6: e63, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sieverdes JC, Raynor PA, Armstrong T, Jenkins CH, Sox LR, Treiber FA: Attitudes and perceptions of patients on the kidney transplant waiting list toward mobile health-delivered physical activity programs. Prog Transplant 25: 26–34, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Q, Liu L: The technology acceptance model: A meta-analysis of empirical findings. J Organ End User Comput 16: 59–72, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khatun F, Heywood AE, Ray PK, Hanifi SM, Bhuiya A, Liaw ST: Determinants of readiness to adopt mHealth in a rural community of Bangladesh. Int J Med Inform 84: 847–856, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Zeev D, Fathy C, Jonathan G, Abuharb B, Brian RM, Kesbeh L, Abdelkader S: mHealth for mental health in the Middle East: Need, technology use, and readiness among Palestinians in the West Bank. Asian J Psychiatr 27: 1–4, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung L, Chen C: e-Health/m-Health adoption and lifestyle improvements: Exploring the roles of technology readiness, the expectation-confirmation model, and health-related information activities Proceedings from the 14th International Telecommunications Society Asia-Pacific Regional Conference, Kyoto, Japan, International Telecommunications Society, 2017, pp 1–37 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy MM, Thekkur P, Majella G, Selvaraj K, Ramakrishnan J, Kar SS: Use of mobile phone in healthcare: Readiness among urban population of Puducherry, India. Int J Med Pub Hlth 6: 94–97, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apolinário-Hagen J, Hennemann S, Fritsche L, Drüge M, Breil B: Determinant factors of public acceptance of stress management apps: Survey study. JMIR Ment Health 6: e15373, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon NP, Hornbrook MC: Older adults’ readiness to engage with eHealth patient education and self-care resources: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 18: 220, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bommakanti KK, Smith LL, Liu L, Do D, Cuevas-Mota J, Collins K, Munoz F, Rodwell TC, Garfein RS: Requiring smartphone ownership for mHealth interventions: Who could be left out? BMC Public Health 20: 81, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rai A, Chen L, Pye J, Baird A: Understanding determinants of consumer mobile health usage intentions, assimilation, and channel preferences. J Med Internet Res 15: e149, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treskes RW, Koole M, Kauw D, Winter MM, Monteiro M, Dohmen D, Abu-Hanna A, Schijven MP, Mulder BJ, Bouma BJ, Schuuring MJ: Adults with congenital heart disease: Ready for mobile health? Neth Heart J 27: 152–160, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbasi R, Zare S, Ahmadian L: Investigating the attitude of patients with chronic diseases about using mobile health. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 36: 139–144, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lew SQ, Sikka N: Telehealth awareness in a US urban peritoneal dialysis clinic: From 2018 to 2019. Perit Dial Int 40: 227–229, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lew SQ, Sikka N: Are patients prepared to use telemedicine in home peritoneal dialysis programs? Perit Dial Int 33: 714–715, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonner A, Gillespie K, Campbell KL, Corones-Watkins K, Hayes B, Harvie B, Kelly JT, Havas K: Evaluating the prevalence and opportunity for technology use in chronic kidney disease patients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 19: 28, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browning RB, McGillicuddy JW, Treiber FA, Taber DJ: Kidney transplant recipients’ attitudes about using mobile health technology for managing and monitoring medication therapy. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 56: 450–454.e1, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGillicuddy JW, Gregoski MJ, Weiland AK, Rock RA, Brunner-Jackson BM, Patel SK, Thomas BS, Taber DJ, Chavin KD, Baliga PK, Treiber FA: Mobile health medication adherence and blood pressure control in renal transplant recipients: A proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2: e32, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor K, Silver L: Smartphone Ownership Is Growing Rapidly around the World, but Not Always Equally, Washington, DC, Pew Research Center, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Knearem T, Carroll J: Learning flows: Understanding how older adults adopt and use mobile technology. Presented at the 12th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, New York, May 21–24, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schatell D, Wise M, Klicko K, Becker BN: In-center hemodialysis patients’ use of the internet in the United States: A national survey. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 285–291, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seto E, Cafazzo JA, Rizo C, Bonert M, Fong E, Chan CT: Internet use by end-stage renal disease patients. Hemodial Int 11: 328–332, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krebs P, Duncan DT: Health app use among US mobile phone owners: A national survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth 3: e101, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minatodani DE, Chao PJ, Berman SJ: Home telehealth: Facilitators, barriers, and impact of nurse support among high-risk dialysis patients. Telemed J E Health 19: 573–578, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett PN, Eilers D, Yang F, Rabetoy CP: Perceptions and practices of nephrology nurses working in home dialysis: An international survey. Nephrol Nurs J 46: 485–495, 2019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennett PN: Technological intimacy in haemodialysis nursing. Nurs Inq 18: 247–252, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh K, Diamantidis CJ, Ramani S, Bhavsar NA, Mara P, Warner J, Rodriguez J, Wang T, Wright-Nunes J: Patients’ and nephrologists’ evaluation of patient-facing smartphone apps for CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 523–529, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siddique AB, Krebs M, Alvarez S, Greenspan I, Patel A, Kinsolving J, Koizumi N: Mobile apps for the care management of chronic kidney and end-stage renal diseases: Systematic search in app stores and evaluation. JMIR mHealth uHealth 7: e12604, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis RA, Lunney M, Chong C, Tonelli M: Identifying mobile applications aimed at self-management in people with chronic kidney disease. Can J Kidney Health Dis 6: 2054358119834283, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaghefi I, Tulu B: The continued use of mobile health apps: Insights from a longitudinal study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 7: e12983, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Depatie A, Bigbee JL: Rural older adult readiness to adopt mobile health technology: A descriptive study. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care 15: 150–184, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Veen T, Binz S, Muminovic M, Chaudhry K, Rose K, Calo S, Rammal JA, France J, Miller JB: Potential of mobile health technology to reduce health disparities in underserved communities. West J Emerg Med 20: 799–802, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.