Visual Abstract

Keywords: kidney failure, conservative kidney management, global health, survey, capacity

Abstract

Background and objectives

People with kidney failure typically receive KRT in the form of dialysis or transplantation. However, studies have suggested that not all patients with kidney failure are best suited for KRT. Additionally, KRT is costly and not always accessible in resource-restricted settings. Conservative kidney management is an alternate kidney failure therapy that focuses on symptom management, psychologic health, spiritual care, and family and social support. Despite the importance of conservative kidney management in kidney failure care, several barriers exist that affect its uptake and quality.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

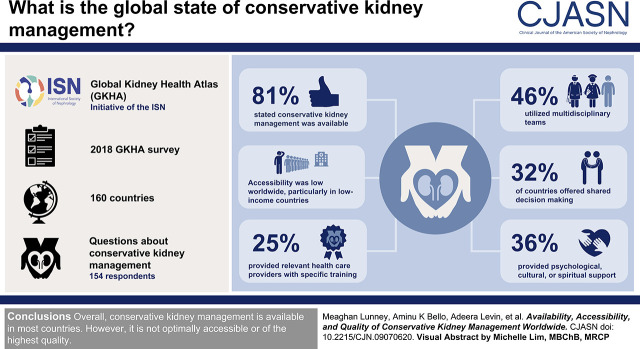

The Global Kidney Health Atlas is an ongoing initiative of the International Society of Nephrology that aims to monitor and evaluate the status of global kidney care worldwide. This study reports on findings from the 2018 Global Kidney Health Atlas survey, specifically addressing the availability, accessibility, and quality of conservative kidney management.

Results

Respondents from 160 countries completed the survey, and 154 answered questions pertaining to conservative kidney management. Of these, 124 (81%) stated that conservative kidney management was available. Accessibility was low worldwide, particularly in low-income countries. Less than half of countries utilized multidisciplinary teams (46%); utilized shared decision making (32%); or provided psychologic, cultural, or spiritual support (36%). One-quarter provided relevant health care providers with training on conservative kidney management delivery.

Conclusions

Overall, conservative kidney management is available in most countries; however, it is not optimally accessible or of the highest quality.

Introduction

The default medical decision for people with kidney failure (an eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2) is to offer them KRT, either dialysis or kidney transplantation. However, dialysis does not always improve outcomes, has several limitations, and may not be desirable for some patients, particularly older adults (1). Similarly, kidney transplantation is not always feasible or optimal for patients.

Even for those who would benefit most from KRT, this treatment is not always an option. Organ shortage and limitations in resources required for surgery or postoperative care (for example, immunosuppressants) often limit access to kidney transplantation. Dialysis is also an expensive modality and may not be widely available or accessible either because a country or region is unable to cover the costs to offer the service or because individuals are unable to pay the accompanying out-of-pocket expenses. Limitations in other economic and social resources required for dialysis, such as transportation fees, may further impose barriers to the accessibility of treatment for patients, possibly more common among older adults.

Therefore, selecting the most appropriate treatment for kidney failure requires careful consideration of the individual patient’s conditions, social circumstances, wishes, preferences, and life goals. Conservative kidney management focuses on supporting the needs of patients through symptom management, psychologic therapy, or family and social support (2) and is an alternative to patients unlikely to benefit from KRT (i.e., chosen or medically advised) or unable to access KRT (i.e., choice restricted). Recommendations on how to optimally deliver conservative kidney management, focused on the patient’s values and preferences, minimizing symptoms due to disease, and improving comfort and quality of life, are available to help guide practice (3,4).

Despite the potential of conservative kidney management as a therapy for kidney failure, its utilization across the globe is unknown. Limited evidence on health outcomes makes decision making for nephrologists a challenge (5) and may result in the exclusion of conservative kidney management from kidney care policies. Additionally, as the awareness of conservative kidney management is relatively low, limited health care provider training, public expectations of what is considered more active care, and remuneration for care may impede its adoption (6).

Our objective for this study was to identify the current availability and accessibility of conservative kidney management worldwide. Additionally, we were interested in the quality of delivery in countries that do offer conservative kidney management. We leveraged data from the second Global Kidney Health Atlas (GKHA) survey (7), which focused on kidney failure care, including KRT and conservative kidney management.

Materials and Methods

As described elsewhere (7–9), the GKHA is a project of the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) targeted at improving the global capacity of kidney care through an international survey of stakeholders. Details on the survey development and validation have previously been published (8,9). To date, two iterations of the survey have been conducted (2016 and 2018) (10). Survey items pertaining to conservative kidney management were not included in the 2016 survey but were added to the second iteration. Here, we utilize the 2018 version to report on items specific to conservative kidney management (Supplemental Material).

Key kidney care stakeholders (nephrology leaders, consumers, and health care policy makers) were invited to participate on the basis of their knowledge of kidney care and ability to accurately represent their country. In total, two to three representatives of 182 countries received an invitation to participate in the survey. We administered the survey online via REDCap Cloud (www.redcapcloud.com) from July to September 2018. We stored data in a centralized database and checked for inconsistencies within country responses. We asked ISN regional leaders to clarify discrepancies and, subsequently, updated the database. We imported the database into Stata 15 software (Stata Corporation). We analyzed data using descriptive statistics and reported findings as an overall aggregate score, stratified by ISN region (11) and by World Bank income group. Country was the unit of analysis. The chi-squared test was used to examine differences in conservative kidney management accessibility and quality in this study.

A definition of conservative kidney management was provided in the survey (Supplemental Material), following the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) recommendations. Conservative kidney management was defined as “planned, holistic, patient-centered care for patients with CKD stage 5, that includes interventions to delay progression of kidney disease and minimize complications but focuses predominantly on symptom management and psychological, social, cultural and spiritual support but does not include dialysis,” according to KDIGO (2). It was further described that conservative kidney management could be administered as a chosen or medically advised treatment (i.e., an appropriate treatment modality for patients who choose not to initiate KRT) or as a choice-restricted treatment (i.e., patients in whom resource constraints prevent or limit access to KRT).

Respondents were asked to report whether conservative kidney management was available in their country (yes, no, or unknown), and for those with conservative kidney management, the availability of chosen or medically advised and choice-restricted care. Further, respondents were asked to rank its accessibility across settings (for example, home, hospital, hospice, and nursing home). Lastly, respondents were asked to rate the quality of conservative kidney management as measured by the general availability of the following five domains: (1) multidisciplinary team approaches; (2) tools for shared decision making (i.e., practice guidelines for providers or patient decision aids); (3) systematic active recognition and management of symptoms associated with kidney failure; (4) psychologic, cultural, and spiritual support; and (5) additional training to health care providers for conservative kidney management (Supplemental Material).

The University of Alberta Research Ethics Committee approved this project (protocol no. PRO00063121), and all participants provided implied consent.

Results

Survey Response Rate

Of the 182 countries that received an invitation to participate in the 2018 survey, respondents from 160 (88%) participated. Of these, 311 respondents from 154 (96%) countries answered the survey item related to conservative kidney management availability (Supplemental Material, C.6.1). Of the 311 respondents, 82% were nephrologists, 7% were non-nephrologist physicians, 5% were administrators or policy makers, 2% were nonphysician health care providers, and 4% reported another profession. Countries across all income groups were represented: 22 of the 23 (96%) low-income countries responded to the survey question about conservative kidney management, as did 35 of 38 (92%) lower middle–income countries, 41 of 41 (100%) upper–income countries, and 56 of 58 (97%) of high-income countries.

Conservative Kidney Management Availability and Accessibility

Overall, respondents from 124 of 154 countries (81%) stated that conservative kidney management was available (Table 1). Income level was not associated with its availability. Of the 124 countries offering conservative kidney management, hemodialysis was available in all. Twenty-five countries (21%) do not have peritoneal dialysis available, and 34 (27%) do not have kidney transplantation available. Eighteen countries (15%) have neither peritoneal dialysis nor transplantation available: 14 in Africa, one in Latin America, two in Oceania and Southeast Asia, and one in North America and the Caribbean (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Global availability and accessibility of conservative kidney management worldwide

| ISN Region and World Bank Income Group | Availability: Is Conservative Kidney Management Available in Your Country? | Accessibility: Easy Access to Conservative Kidney Management across Settings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, N (%) | No, N (%) | Unknown, N (%) | Totala | Generally Available, N (%) | Generally Not Available, N (%) | Never, N (%) | Unknown, N (%) | No Response, N (%) | Total Countries with Conservative Kidney Management Available | |

| Overall | 124 (81) | 28 (18) | 2 (1) | 154 | 47 | 54 | 14 | 0 | 9 | 124 |

| ISN regions | ||||||||||

| Africa | 33 (80) | 8 (20) | 0 (0) | 41 | 5 (15) | 16 (48) | 8 (24) | 0 (0) | 4 (12) | 33 |

| E and C Europe | 18 (95) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 19 | 8 (44) | 10 (56) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 |

| Latin America | 8 (44) | 10 (56) | 0 (0) | 18 | 0 (0) | 7 (39) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 |

| Middle East | 9 (82) | 2 (18) | 0 (0) | 11 | 3 (33) | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 9 |

| NIS and Russia | 4 (57) | 3 (43) | 0 (0) | 7 | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 |

| NAC | 6 (67) | 3 (33) | 0 (0) | 9 | 5 (83) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 |

| N and E Asia | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 | 1 (14) | 6 (86) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 |

| OSEA | 14 (93) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 15 | 7 (50) | 3 (21) | 4 (29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 |

| South Asia | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 | 1 (14) | 3 (43) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (43) | 7 |

| Western Europe | 18 (90) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 20 | 16 (89) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 |

| World bank income group | ||||||||||

| Low | 18 (82) | 4 (18) | 0 (0) | 22 | 0 (0) | 10 (56) | 5 (28) | 0 (0) | 3 (17) | 18 |

| Lower middle | 26 (74) | 9 (26) | 0 (0) | 35 | 6 (23) | 12 (46) | 4 (15) | 0 (0) | 4 (15) | 26 |

| Upper middle | 33 (80) | 8 (20) | 0 (0) | 41 | 9 (27) | 18 (55) | 5 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 33 |

| High | 47 (84) | 7 (13) | 2 (3) | 56 | 32 (68) | 14 (30) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 47 |

Row % totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding. ISN, International Society of Nephrology; E and C Europe, Eastern and Central Europe; NIS, newly independent states; NAC, North America and the Caribbean; N and E Asia, North and East Asia; OSEA, Oceania and South East Asia.

Total countries that responded to questions related to conservative kidney management (160 in total responded to the 2016 Global Kidney Health Atlas questionnaire).

Respondents from 28 of the 154 countries reported that conservative kidney management was not available (Table 2). Of these 28 countries, all provide hemodialysis services, 23 (82%) offer peritoneal dialysis, and 21 (75%) offer kidney transplantation. The majority of countries that lacked conservative kidney management fund KRT either exclusively by the government with no fees (n=10) or through a mix of public and private sources (n=10) (Table 2). Four countries funded KRT through the government, with some fees at the point of delivery. Two countries funded KRT exclusively through private sources (i.e., out of pocket). One country funded KRT through multiple sources (i.e., programs provided by government, nongovernment organizations, and communities). One country selected “Other” as the funding structure for KRT.

Table 2.

Availability of KRTs and funding sources among countries reporting an absence of conservative kidney management

| International Society of Nephrology Region and Country | World Bank Income Group | Hemodialysis | Peritoneal Dialysis | Kidney Transplantation | KRT Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||||

| Botswana | Upper middle | ✓ | ✓ | X | Mix (govt + private) |

| Ethiopia | Low | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Mauritania | Lower middle | ✓ | X | X | Govt (no fees) |

| Sierra Leone | Low | ✓ | X | X | Other |

| Sudan | Lower middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple |

| Swaziland | Lower middle | ✓ | ✓ | X | Govt (some fees) |

| Tanzania | Low | ✓ | X | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Zimbabwe | Low | ✓ | ✓ | X | Govt (some fees) |

| Eastern and Central Europe | |||||

| Lithuania | High | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| Latin America | |||||

| Bolivia | Lower middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Brazil | Upper middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| Chile | High | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (some fees) |

| El Salvador | Lower middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Guatemala | Lower middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Mexico | Upper middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (some fees) |

| Peru | Upper middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Puerto Rico | High | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Uruguay | High | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Venezuela | Upper middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| Middle East | |||||

| Syrian Arab Republic | Lower middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| West Bank and Gaza | Lower middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| NIS and Russia | |||||

| Belarus | Upper middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| Kazakhstan | Upper middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| Russian Federation | Upper middle | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| North America and the Caribbean | |||||

| Antigua and Barbuda | High | ✓ | X | ✓ | Govt (no fees) |

| St. Kitts and Nevis | High | ✓ | ✓ | X | Private |

| Trinidad and Tobago | High | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mix (govt + private) |

| Oceania and Southeast Asia | |||||

| Cambodia | Lower middle | ✓ | X | X | Private |

Eight countries that do not have conservative kidney management available also do not offer peritoneal dialysis: Ethiopia (Africa), Mauritania (Africa), Sierra Leone (Africa), Tanzania (Africa), Syrian Arab Republic (Middle East), West Bank and Gaza (Middle East), Antigua and Barbuda (North America and the Caribbean), and Cambodia (Oceania and Southeast Asia). Seven countries that do not have conservative kidney management available also do not offer kidney transplantation: Botswana (Africa), Mauritania (Africa), Sierra Leone (Africa), Swaziland (Africa), Zimbabwe (Africa), St. Kitts and Nevis (North America and the Caribbean), and Cambodia (Oceania and Southeast Asia). KRT includes dialysis and transplantation but excludes conservative kidney management. ✓, available; X, not available; Mix (govt + private), mix of government (public) and private; Govt (no fees), government (no fees at point of delivery); Other, other funding sources; Multiple, multiple sources (programs provided by government, nongovernment organizations, and communities); Govt (some fees), government (some fees at point of delivery); NIS, newly independent states; Private, private (solely out of pocket).

Of the 124 countries with conservative kidney management available, 47 (38%) offer services that are easily accessible across settings (for example, at the patient’s home, hospital, hospice, or nursing home) (Table 1). Accessibility to conservative kidney management services was significantly different across the four income levels (χ2=33.2, P<0.001): high-income (32 of 47; 68%), upper middle–income (nine of 33; 27%), lower middle–income (six of 26; 23%), and low-income (zero of 18; 0%) countries.

Chosen or Medically Advised Conservative Kidney Management

Among countries with conservative kidney management available, respondents from 77 (62%) reported that chosen or medically advised conservative kidney management was generally available. This was highest in North America (six of six) and Western Europe (18 of 18). Less than half of countries in South Asia (one of seven), the Middle East (two of nine), Latin America (three of eight), and Oceania and Southeast Asia (six of 14) reported that it was selected by choice or following medical advice. The availability of chosen or medically advised conservative kidney management was higher with increasing income level: 33% of low-income, 39% of lower middle–income, 64% of upper middle–income, and 85% of high-income countries reported availability. Of the 77 countries that generally offered chosen or medically advised conservative kidney management, 39 (51%) funded KRT publicly with no fees to patients at the point of care delivery, 15 (19%) funded KRT publicly with some fees to patients, 16 (21%) funded KRT through a mix of public and private sources, three (4%) funded through multiple sources (i.e., government, nongovernment organizations, and communities), three (4%) funded solely through private sources, and one country (1%) reported an “Other” type of funding model for KRT.

Quality of Conservative Kidney Management Services

Five indicators were used to assess the quality of conservative kidney management services (Table 3). Of the countries that offered services, respondents from 57 (46%) reported that multidisciplinary teams were generally available among centers. Forty (32%) incorporated shared decision making; 80 (65%) had processes in place to systematically recognize and manage symptoms; 45 (36%) provided psychologic, cultural, or spiritual support; and 31 (25%) provided relevant health care providers with additional training on how to deliver conservative kidney management (Table 3). Across every indicator, high-income countries reported a greater presence of quality metrics, and low-income countries reported they generally were not available, particularly for provider training (0%), shared decision making (11%), and psychologic, cultural, and spiritual support (17%) (Supplemental Table 2). Among countries offering conservative kidney management, respondents from 33 (27%) reported that no quality indicators were generally available, and respondents from 26 (21%) reported that all five were generally available.

Table 3.

Number of countries with conservative kidney management available and components of care that are generally available

| ISN Region and World Bank Income Group | Countries with Conservative Kidney Management Available, N | Quality Indicators,a N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary Teams | Shared Decision Making | Symptom Management | Psychologic, Cultural, Spiritual Support | Health Care Provider Training | ||

| Overall | 124 | 57 (46) | 40 (32) | 80 (65) | 45 (36) | 31 (25) |

| ISN regions | ||||||

| Africa | 33 | 11 (33) | 9 (27) | 17 (52) | 7 (21) | 4 (12) |

| E and C Europe | 18 | 9 (50) | 6 (33) | 14 (78) | 6 (33) | 6 (33) |

| Latin America | 8 | 3 (34) | 0 (0) | 4 (50) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Middle East | 9 | 2 (22) | 1 (11) | 7 (78) | 1 (11) | 1 (11) |

| NIS and Russia | 4 | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) |

| NAC | 6 | 5 (83) | 4 (67) | 6 (100) | 3 (50) | 2 (33) |

| N and E Asia | 7 | 5 (71) | 1 (14) | 5 (71) | 2 (29) | 1 (14) |

| OSEA | 14 | 7 (50) | 5 (36) | 6 (43) | 7 (50) | 6 (43) |

| South Asia | 7 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | 4 (57) | 1 (14) |

| Western Europe | 18 | 13 (72) | 13 (72) | 17 (94) | 12 (67) | 9 (50) |

| World bank income group | ||||||

| Low | 18 | 4 (22) | 2 (11) | 9 (50) | 3 (17) | 0 (0) |

| Lower middle | 26 | 6 (23) | 7 (27) | 12 (46) | 8 (31) | 6 (23) |

| Upper middle | 33 | 16 (48) | 8 (24) | 18 (55) | 10 (30) | 7 (21) |

| High | 47 | 31 (66) | 23 (49) | 41 (87) | 24 (51) | 18 (38) |

Generally available means in 50% or more centers (hospitals or clinics). Other response options (not shown) included generally not available (in <50% of centers), never, or unknown. Row totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding. ISN, International Society of Nephrology; E and C Europe, Eastern and Central Europe; NIS, newly independent states; NAC, North America and the Caribbean; N and E Asia, North and East Asia; OSEA, Oceania and South East Asia.

Davison et al. (2).

Of the 33 countries that did not report any quality indicators, eight were low-income (44% of the region), 11 were lower middle–income (42%), ten were upper middle–income (30%), and four were high-income (9%) countries. Of the 26 countries that reported that all five quality indicators were generally available, zero were low income, three were lower middle–income (12% of region), six were upper middle–income (18%), and 17 were high income (36% of region). There was a statistically significant difference in quality reporting among the four income groups (χ2=21.1, P<0.001).

Discussion

The 2018 GKHA survey identified that most countries offer conservative kidney management in some form. However, it was not clear whether it was offered because it was medically advised or because KRT was not possible (i.e., choice restricted). Only 38% of countries with conservative kidney management offer easily accessible services. The quality of care delivery across countries varied but was poor overall. Respondents from high-income countries reported higher quality of conservative kidney management compared with those from countries of lower economic standing. KRT was available in all 28 countries that did not offer conservative kidney management.

Compared with other treatment options for kidney failure, conservative kidney management is a relatively new treatment modality, and there are still several unknowns with respect to how it should be adopted in practice and optimally delivered (12). In 2015, the KDIGO organization hosted a conference to review evidence and develop recommendations for managing advanced CKD, including addressing conservative kidney management (2). Only last year, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence published a document to expand awareness and understanding about the various components of conservative kidney management (13). Efforts to disseminate these guidelines internationally to promote a standard practice in delivering conservative kidney management may help reduce the variability of care for people with kidney failure who do not receive KRT.

The quality of conservative kidney management varies not only across countries but, likely, will vary within countries and even within centers depending on individual nephrologist beliefs, attitudes, and ability or willingness to communicate about conservative kidney management and prognosis. Efforts to reduce this variability through appropriate guidelines, communication, and training are, therefore, important to ensure not only high quality but also equity of conservative kidney management care. Establishing conservative kidney management programs that address elements prioritized by patients, families, and health care providers (14) is important to ensure that patients receive the best quality of care possible.

The decision to choose between KRT and conservative kidney management is complex for both health care providers and patients. A significant reason behind the difficulty in making a decision is likely related to the limited evidence regarding patients who would benefit more from, or prefer, conservative kidney management compared with dialysis. To date, all research exploring nondialysis care has utilized observational studies and therefore is potentially vulnerable to performance bias because people who opt for dialysis may have different characteristics than those who choose conservative kidney management (12). Also, most studies do not report on the same outcome, and the outcomes chosen for reporting may not be those that are most important to patients (12). Most studies focus on survival as the main outcome measure, which may miss the fact that quality of life and symptom control may be more important measures from patients’ points of view. Pragmatic, realist, randomized controlled trials, such as the Prepare for Kidney Care trial (15), that involve a number of clinical and patient-centered outcomes may help improve the quality of the evidence and, subsequently, guide health care providers and patients with decision making.

Utilizing processes to support patients, families, and health care providers make decisions may also help patients receive the most appropriate care. Decision aids (16,17) that inform patients about different options for treatment of kidney failure may encourage shared decision making and help identify the most appropriate pathway. Although there are a number of decision aids targeted at KRT, few focus on the decision between dialysis and nondialysis care (18). Currently, the few decision aids available with a specific focus on choosing dialysis or conservative kidney management include the Conservative Kidney Management Patient Decision Aid, the Ottawa tool, OPTIONS (18), and one developed by the Renal Team at St. George and Sutherland Hospitals in Australia (19). These should offer a helpful resource for providers, patients, and families in the future.

There are several gaps in conservative kidney management delivery worldwide. To increase the adoption of high-quality care around the world, a number of actions will likely be required (Box 1).

Box 1.

Recommendations for how to improve conservative kidney management accessibility and quality worldwide (Davison et al. [2])

| Increase the awareness of conservative kidney management as a viable treatment modality among patients and families, health care providers, and policy makers and clarify its definition and standard of care. |

| Identify the barriers to conservative kidney management availability, accessibility, and quality so that strategies can be developed to increase capacity. |

| Develop policies to ensure that conservative kidney management is optimal and is not seen as solely palliative care for those who cannot receive KRT. |

| Expand the evidence to provide better information regarding the outcomes associated with conservative kidney management as well as characteristics of patients who are most suitable for this treatment option. |

| Disseminate guidelines that are accessible globally and adaptable to each local context. |

| Support shared decision making among health care providers, patients, and families. |

| Understand the current barriers that countries are experiencing with conservative kidney management delivery. |

| Provide government-funded services essential for conservative kidney management, such as health care provider training, symptom management, and psychologic support. |

Additionally, ISN is developing a kidney failure strategic plan as a follow-up to the paper by Harris et al. (20) on integrated kidney failure care. This 5- to 10-year strategy will use working groups to design activities and deliverables related to monitoring, dialysis, resources, and support (21). More information will be available over the coming year. Additionally, ISN is collaborating with the World Health Organization to develop a technical package for setting up maintenance dialysis programs suitable for low-resource settings, which also includes discussion of conservative kidney management.

Similar to other questionnaires, our survey has the potential for subjectivity (social desirability bias) and was highly dependent on respondents’ knowledge, expertise, and perceptions. However, respondents were informed their identity would remain confidential in an attempt to reduce the potential for bias. The survey questions were assessed for face validity; however, the accuracy of our findings depends on how correctly respondents represented the status of services in their country. We, therefore, worked closely with ISN’s Regional Boards to select respondents with a range of kidney care knowledge and expertise while ensuring adequate regional representation, and we corroborated findings with regional leaders. Regardless, there are risks that survey items were unclear. For example, just over 80% of countries in our survey reported that conservative kidney management was available. Even though the survey provided a definition of conservative kidney management, it is possible that the availability of services was overestimated if conservative kidney management was understood to mean simply managing kidney failure in the absence of dialysis or transplantation. Additionally, the type of conservative kidney management offered (i.e., choice restricted or chosen/medically advised) was presented as independent items instead of a mutually exclusive option and therefore was likely difficult to interpret. Lastly, only countries with available stakeholders were invited to complete the survey. It is possible that excluding countries that did not respond to the survey might have contributed to an overestimation of capacity if the reason they did not participate was due to limited information or resources or political focus on kidney care. However, we received representation of 98% of the global population, and therefore, the proportion of the global population excluded from these 36 countries was likely minimal.

Overall, most countries offer conservative kidney management, but it was not always clear whether it was selected because it was medically advised or because KRT was not possible (i.e., choice restricted). Several gaps were reported across most quality indicators, including limited health care provider training for conservative kidney management delivery; shared decision making; psychologic, cultural, or spiritual support; and the use of multidisciplinary teams. These gaps were particularly notable in low-income countries. Efforts to increase the awareness, standardization, and uptake of practices recommended for conservative kidney management are needed to ensure high quality of care.

Disclosures

A.K. Bello reports receiving honoraria from Amgen, Janssen, and Otsuka; serving as an associate editor of Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease; and serving as cochair of ISN GKHA. M. Benghanem Gharbi reports receiving honoraria from Amgen. E.A. Brown reports receiving personal fees from AWAK for serving on an advisory board, speaker and consultancy fees from Baxter Healthcare, and personal fees from LiberDi for serving on an advisory board, outside the submitted work. F. Caskey reports receiving honoraria from Baxter Healthcare and research grants from Kidney Research UK and National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study. Y. Cho reports receiving grants from Amgen, grants and speaker’s honoraria from Baxter Healthcare, and grants from Fresenius Medical Care and is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship. D.C. Harris reports grant support from the National Health and Medical Research Council. H. Htay reports receiving consultancy fees and travel sponsorships from AWAK Technologies Pte. Ltd. and speaker’s honoraria and travel sponsorships from Baxter Healthcare, outside the submitted work. K.J. Jager reports receiving grants from European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association during the conduct of the study. V. Jha reports personal fees from AstraZeneca (paid to the organization), grants from Baxter Healthcare (paid to the organization), grants from Biocon (paid to the organization), grants from GSK (paid to the organization), and personal fees from NephroPlus (paid to the organization), outside the submitted work. K.K. Jindal reports receiving research funding from Amgen and Rockwell and receiving honoraria from Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Lily. D.W. Johnson reports receiving travel sponsorship from Amgen; consultancy fees from AstraZeneca; consultancy fees from AWAK; consultancy fees, speaker’s honoraria, and a Clinical Evidence Council grant from Baxter Healthcare; research grant, speaker’s honoraria, and consultancy fees from Fresenius Medical Care; grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia during the study; support from the Practitioner Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia; and speaker’s honoraria from Ono, outside the submitted work. R.T. Kazancioglu reports receiving honoraria from Baxter and having other interests/relationships with the board of Turkish Kidney Foundation. E. Rondeau reports consultancy agreements with Alexion; receiving research funding from Alexion, Astellas, and Novartis; receiving honoraria from Alexion; serving as a scientific advisor or member of Alexion; serving as a member of the council of ISN; and serving as cochair of the Declaration of Istanbul Custodian Group. L. Sola reports employment with Centro de Asistencia del Sindicato Médico del Uruguay-Institución de Asistencia Medica Privada de Profesionales (CASMU-IAMPP). V. Tesar reports consultancy agreements with Abbvie, Amgen, Baxter, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Calliditas, Chemocentryx, Fresenius Medical Care, Novartis, Omeros, Otsuka, Pfizer, Retrophin, and Sanofi; receiving honoraria for consultancy with Abbvie, Amgen, Baxter, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Calliditas, Chemocentryx, Fresenius Medical Care, Novartis, and Retrophin; and serving as a member of Abbvie, Amgen, Baxter, Calliditas, Chemocentryx, Fresenius Medical Care, Novartis, and Retophin. M. Tonelli reports consultancy agreements with Retrophin. Daichi Sankyo awarded a grant to M. Tonelli’s institution in lieu of a personal honorarium for a lecture at a scientific meeting in 2017. The lecture topic was not related to the topic of this article. M. Tonelli also received a lecture fee from B. Braun in 2019; the fee was donated to charity. The lecture topic was not related to the topic of this article. M. Tonelli reports serving as a scientific advisor or member of American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Kidney Diseases, and Kidney International and having other interests/relationships with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and KDIGO. K. Tungsanga reports other interests/relationships with the Asia-Pacific Society of Nephrology, the Bhumirajanagarindra Kidney Institute, ISN, the Kidney Foundation of Thailand, the Medical Association of Thailand, the Nephrology Society of Thailand, and the Royal College of Physicians of Thailand. A. Zemchenkov reports consultancy agreements with Amgen, Baxter, and Fresenius Kabi and receiving honoraria from Pfizer. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by International Society of Nephrology grant RES0033080 (to the University of Alberta).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Sandrine Damster (Research Project Manager at ISN) and Alberta Kidney Disease Network staff (Ms. Ghenette Houston, Ms. Sue Szigety, and Ms. Sophanny Tiv) for helping to organize and conduct the survey and providing project management support; Ms. Jo-Ann Donner (Awards, Endorsements, ISN-American Nephrologists of Indian Origin [ANIO] Programs Coordinator) for helping with the manuscript management and submission process; Dr. Charu Malik (ISN Executive Director) for her support; and the GKHA steering committee, the executive committee of ISN, ISN regional leadership, and the leaders of the ISN Affiliate Societies at the regional and country levels for their help, particularly with identification of survey respondents and data acquisition, which ensured the success of this initiative. None of the persons acknowledged received compensation for their role in the study.

ISN provided administrative support for the design and implementation of the study and data collection activities. The authors were responsible for data management, analysis, and interpretation, as well as manuscript preparation, review, and approval and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

A.K. Bello, D.C. Harris, D.W. Johnson, A. Levin, and M. Tonelli contributed to the study concept and design; A.K. Bello, S.N. Davison, and M. Lunney drafted the manuscript; F. Ye and M. Lunney conducted the statistical analyses; A.K. Bello, D.W. Johnson, and A. Levin obtained funding; F. Ye, M.A. Osman, and M. Lunney provided administrative, technical, and material support; all of the authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; cochairs A.K. Bello and D.W. Johnson of ISN’s GKHA supervised the study; A.K. Bello and D.W. Johnson had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; M. Lunney attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted; and A.K. Bello is the guarantor.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.09070620/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Material. Survey items from the 2018 Global Kidney Health Atlas relating to conservative kidney management.

Supplemental Table 1. Availability of KRTs and funding sources among countries offering conservative kidney management.

Supplemental Table 2. Number of quality indicators of conservative kidney management delivery reported overall and by country income level.

References

- 1.Anand S, Kurella Tamura M, Chertow GM: The elderly patients on hemodialysis. Minerva Urol Nefrol 62: 87–101, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, Jha V, Brown EA, Brennan F, Murtagh FE, Naicker S, Germain MJ, O’Donoghue DJ, Morton RL, Obrador GT; Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes : Executive summary of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes controversies conference on supportive care in chronic kidney disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Available at: https://kdigo.org/. Kidney Int 88: 447–459, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MA, Crail SM, Masterson R, Foote C, Robins J, Katz I, Josland E, Brennan F, Stallworthy EJ, Siva B, Miller C, Urban AK, Sajiv C, Glavish RN, May S, Langham R, Walker R, Fassett RG, Morton RL, Stewart C, Phipps L, Healy H, Berquier I: ANZSN renal supportive care 2013: Opinion pieces [corrected] [published correction appears in Nephrology (Carlton) 19: 175, 2014]. Nephrology (Carlton) 18: 401–454, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison SN, Tupala B, Wasylynuk BA, Siu V, Sinnarajah A, Triscott J: Recommendations for the care of patients receiving conservative kidney management: Focus on management of CKD and symptoms. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 626–634, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, Loke R, Oskoui T, Perrone RD, Meyer KB, Weiner DE, Wong JB: Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD: An interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 627–635, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA: System-level barriers and facilitators for foregoing or withdrawing dialysis: A qualitative study of nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 602–610, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bello AK, Levin A, Lunney M, Osman MA, Ye F, Ashuntantang GE, Bellorin-Font E, Benghanem Gharbi M, Davison SN, Ghnaimat M, Harden P, Htay H, Jha V, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kerr PG, Klarenbach S, Kovesdy CP, Luyckx VA, Neuen BL, O’Donoghue D, Ossareh S, Perl J, Rashid HU, Rondeau E, See E, Saad S, Sola L, Tchokhonelidze I, Tesar V, Tungsanga K, Turan Kazancioglu R, Wang AY, Wiebe N, Yang CW, Zemchenkov A, Zhao MH, Jager KJ, Caskey F, Perkovic V, Jindal KK, Okpechi IG, Tonelli M, Feehally J, Harris DC, Johnson DW: Status of care for end stage kidney disease in countries and regions worldwide: International cross sectional survey. BMJ 367: l5873, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bello AK, Johnson DW, Feehally J, Harris D, Jindal K, Lunney M, Okpechi IG, Salako BL, Wiebe N, Ye F, Tonelli M, Levin A: Global Kidney Health Atlas (GKHA): Design and methods. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 7: 145–153, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bello AK, Levin A, Tonelli M, Okpechi IG, Feehally J, Harris D, Jindal K, Salako BL, Rateb A, Osman MA, Qarni B, Saad S, Lunney M, Wiebe N, Ye F, Johnson DW: Assessment of global kidney health care status. JAMA 317: 1864–1881, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Society of Nephrology : Global Kidney Health Atlas. Available at: https://www.theisn.org/in-action/research/global-kidney-health-atlas/. Accessed August 26, 2019

- 11.International Society of Nephrology : Regional Boards. Available at: https://www.theisn.org/about-isn/governance/regional-boards/. Accessed February 14, 2020

- 12.Murtagh FE, Burns A, Moranne O, Morton RL, Naicker S: Supportive care: Comprehensive conservative care in end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1909–1914, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Renal replacement therapy and conservative management. NICE guideline [NG107], 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng107. Accessed September 17, 2019 [PubMed]

- 14.Harrison TG, Tam-Tham H, Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Sinnarajah A, Thomas CM: Identification and prioritization of quality indicators for conservative kidney management. Am J Kidney Dis 73: 174–183, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.University of Bristol: Prepare for kidney care trial. Available at: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/population-health-sciences/projects/prepare-kc-trial/. Accessed September 17, 2019

- 16.Alberta Health Services : Conservative Kidney Management (CKM), 2016. Available at: https://www.ckmcare.com. Accessed September 17, 2019

- 17.Fortnum D, Smolonogov T, Walker R, Kairaitis L, Pugh D: ‘My kidneys, my choice, decision aid’: Supporting shared decision making. J Ren Care 41: 81–87, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis JL, Davison SN: Hard choices, better outcomes: A review of shared decision-making and patient decision aids around dialysis initiation and conservative kidney management. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 26: 205–213, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.St. George and Sutherland Hospitals, Renal Department: Information for patients about advanced kidney disease: Dialysis and non-dialysis treatments, 2017. Available at: https://stgrenal.org.au/sites/default/files/upload/Predialysis/Patient information about dialysis 2018_V2.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2020

- 20.Harris DCH, Davies SJ, Finkelstein FO, Jha V, Donner JA, Abraham G, Bello AK, Caskey FJ, Garcia GG, Harden P, Hemmelgarn B, Johnson DW, Levin NW, Luyckx VA, Martin DE, McCulloch MI, Moosa MR, O’Connell PJ, Okpechi IG, Pecoits Filho R, Shah KD, Sola L, Swanepoel C, Tonelli M, Twahir A, van Biesen W, Varghese C, Yang CW, Zuniga C; Working Groups of the International Society of Nephrology’s 2nd Global Kidney Health Summit: Increasing access to integrated ESKD care as part of universal health coverage. Kidney Int 95: S1–S33, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hole B, Hemmelgarn B, Brown E, Brown M, McCulloch MI, Zuniga C, Andreoli SP, Blake PG, Couchoud C, Cueto-Manzano AM, Dreyer G, Garcia G, Jager KJ, McKnight M, Morton RL, Murtagh FEM, Naicker S, Obrador GT, Perl J, Rahman M, Shah KD, Van Biesen W, Walker RC, Yeates K, Zemchenkov A, Zhao MH, Davies SJ, Caskey FJ: Supportive care for end-stage kidney disease: An integral part of kidney services across a range of income settings around the world. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 10: e86–e94, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.