Keywords: CTRP4, C1QTNF4, fasting refeeding, food intake, ingestive physiology, secreted hormone

Abstract

Central and peripheral mechanisms are both required for proper control of energy homeostasis. Among circulating plasma proteins, C1q/TNF-related proteins (CTRPs) have recently emerged as important regulators of sugar and fat metabolism. CTRP4, expressed in brain and adipose tissue, is unique among the family members in having two tandem globular C1q domains. We previously showed that central administration of recombinant CTRP4 suppresses food intake, suggesting a central nervous system role in regulating ingestive physiology. Whether this effect is pharmacological or physiological remains unclear. We used a loss-of-function knockout (KO) mouse model to clarify the physiological role of CTRP4. Under basal conditions, CTRP4 deficiency increased serum cholesterol levels and impaired glucose tolerance in male but not female mice fed a control low-fat diet. When challenged with a high-fat diet, male and female KO mice responded differently to weight gain and had different food intake patterns. On an obesogenic diet, male KO mice had similar weight gain as wild-type littermates. When fed ad libitum, KO male mice had greater meal number, shorter intermeal interval, and reduced satiety ratio. Female KO mice, in contrast, had lower body weight and adiposity. In the refeeding period following food deprivation, female KO mice had significantly higher food intake due to longer meal duration and reduced satiety ratio. Collectively, our data provide genetic evidence for a sex-dependent physiological role of CTRP4 in modulating food intake patterns and systemic energy metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

Caloric intake and energy expenditure are important components of a complex homeostatic mechanism that regulates body weight over short (days) and long (weeks and months) time scales. The orexigenic and anorexigenic neurocircuits within the hypothalamus and hindbrain play especially important roles in controlling food intake and energy metabolism (1, 18, 39). Neurons within these brain regions integrate metabolite and hormonal signals generated in peripheral tissues in response to altered nutritional cues and energetic demands (10, 15).

Our past efforts to understand tissue cross talk that underlies integrative control of metabolism have led to the identification and characterization of a family of 15 secreted plasma proteins, the C1q/TNF-related proteins (CTRPs) (44, 47, 57, 66, 67, 70–72). Consistent with their high degree of evolutionary conservation from fish to humans, each CTRP family member appears to have distinct but overlapping roles in regulating different aspects of sugar and fat metabolism (28, 31, 43, 45, 46, 53, 60, 65, 69). These proteins either act directly on metabolic tissues (liver, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and pancreas) or modulate tissue metabolism indirectly via their actions on immune cells and low-grade inflammatory responses within adipose tissue in the context of obesity (21, 22, 29). Recombinant protein infusion and loss-of-function mouse models also suggest a central nervous system (CNS) role for CTRP9 and CTRP13 in regulating food intake (8, 65).

Of the more than 30 distinct genes in the human and mouse genomes that encode secretory proteins with the signature complement C1q domain (62), CTRP4 is unique in having two tandem C1q domains connected by a short linker (7). Since our initial identification of CTRP4 (GenBank accession number AAY21929) (72), its regulation and function still remain largely unexplored. In humans, CTRP4 (encoded by C1QTNF4) is most prominently expressed in brain and adipose tissues (7). In mouse and zebrafish, brain tissue has the highest expression of the Ctrp4 transcript. Expression and circulating levels of CTRP4 are dynamic and responsive to the physiological state of an animal. For instance, leptin-deficient obese and diabetic mice have elevated circulating levels of CTRP4 compared with nondiabetic lean controls (7). Expression of Ctrp4 in the hypothalamus is also responsive to food availability: resumption of feeding following an overnight fast upregulates Ctrp4 transcript levels in the hypothalamus (7).

Consistent with a possible central role in modulating ingestive physiology, delivery of recombinant CTRP4 protein (made in mammalian cells) into the lateral ventricle of mice suppresses food intake and alters systemic energy balance (7). This central effect of CTRP4 on food intake is associated with reduced hypothalamic expression of orexigenic neuropeptide genes Npy and Agrp. Similarly, overexpressing CTRP4 in the hypothalamus using adenoviral methods also suppresses food intake and orexigenic neuropeptide gene expression (30). In addition to food intake, a potential role for human CTRP4 in modulating body weight has also been suggested by genomewide association studies (68). Single nucleotide polymorphisms located near the human CTRP4 (C1QTNF4) gene on chromosome 11 are associated with body mass index (68), and some of the variants can affect C1QTNF4 expression level (61).

Other potential functions of CTRP4 have also been noted. For example, a recent study used a transgenic overexpression mouse model to demonstrate anti-inflammatory properties of CTRP4 in a model of colitis (34). In another study, exome sequencing identified a rare variant (H198Q) in the human CTRP4 gene (C1QTNF4) from individuals with a severe form of the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (50). In vitro characterizations suggest that the H198Q variant, but not the wild type (WT) protein, can inhibit TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation and cell death (50).

Although our previous studies and those of others suggest that CTRP4 acts in the brain and peripheral tissues, it remains unclear whether the observed effects are pharmacological or physiological. In the present study, we used a loss-of-function mouse model to delineate the in vivo function of CTRP4 in a physiological context. Our results reaffirm our previous findings that CTRP4 indeed has a central role in modulating ingestive physiology in response to fasting and refeeding. Our data also uncover sex-dependent effects of CTRP4 deficiency on glucose tolerance, diet-induced weight gain, and fat mass accrual. Given the paucity of data on CTRP4, our results provide a foundation for future studies to determine the mechanism of action of this highly conserved but understudied secretory protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse model.

The CTRP4 (C1qtnf4tm1a(KOMP)Wtsi) mouse strain used for this research project was created from embryonic stem cell clone EPD0574_2_A09, obtained from the KOMP Repository (https://www.komp.org) and generated by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Targeting vectors were generated by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute as part of the Knockout Mouse Project (3U01HG004080). Methods used on the CSD-targeted alleles have been published (58). Ctrp4 heterozygous (+/−) mice were generated on a C57BL/6N genetic background. Ctrp4, located on mouse chromosome 2, contains two exons. To create a null allele, a LacZ(β-galactosidase) reporter with a splice site acceptor was inserted between exons 1 and 2, disrupting expression of the gene. Genotyping primers for the Ctrp4 WT allele were forward 5′-CTCAGGGCCTTTGGAAGGGCA-3′ (within intron 1) and reverse 5′-GGGAGGGCTTATCACAGCACC-3′ (within intron 1); the expected size of the WT band was 333 bp. Genotyping primers for the Ctrp4 knockout (KO) allele were forward (within LacZ) 5′-GGTAAACTGGCTCGGATTAGGG-3′ and reverse (within LacZ) 5′-TTGACTGTAGCGGCTGATGTTG-3′; the expected size of the KO allele was 211 bp.

To confirm that Ctrp4 mRNA expression was absent in KO mice, we performed quantitative real-time qPCR analysis on cDNA isolated from brain and white adipose tissue by use of the following primer pair spanning exons 1 and 2: 5′-CGTCCTCACCGAGCAGGATA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTACACCTTGTCGAAGGTCACC-3′ (reverse). The expected size of the amplicon was 224 bp. Expression of Ctrp4 mRNA in white adipose tissue was normalized to expression of 36B4 [encoding the acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 (RPLP0)]. Expression of Ctrp4 mRNA in brain was normalized to expression of 60S ribosomal protein L22 (RPL22). All mice were generated by intercrossing Ctrp4 +/− mice.

Ctrp4 KO and WT littermate controls were housed in polycarbonate cages on a 12-h:12-h light-dark photocycle with ad libitum access to water and food. Mice were fed a high-fat diet (HFD; 60% kcal derived from fat, no. D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or a matched control low-fat diet (LFD; 10% kcal derived from fat, no. D12450B, Research Diets). LFD was provided for 38–39 wk, beginning at 5 wk of age; HFD was provided for 23–24 wk, beginning at 6 wk of age. At termination of the study, HFD-fed mice were fasted for 2 h and euthanized. Tissues were collected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C until analysis. All mouse protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Body composition analysis.

Body composition analyses for total fat, lean mass, and water content were determined using a quantitative magnetic resonance instrument (Echo-MRI-100; Echo Medical Systems, Waco, TX) at the Mouse Phenotyping Core facility, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Complete blood count analysis.

A complete blood count on blood samples was performed at the Pathology Phenotyping Core at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Tail vein blood was collected using EDTA-coated blood collection tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) and analyzed using a Procyte Dx analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME).

Indirect calorimetry.

LFD-fed or HFD-fed WT and Ctrp4 KO male and female mice were used for simultaneous assessments of daily body weight change, food intake (corrected for spillage), physical activity, and whole body metabolic profile in an open-flow indirect calorimeter (Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System, CLAMS; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) as previously described (27). In brief, data were collected for 3 days to confirm mice were acclimatized to the calorimetry chambers (indicated by stable body weights, food intakes, and diurnal metabolic patterns), and data were analyzed from the 4th day. Meal pattern data were analyzed for average meal frequency and meal size; a meal was defined as being at least 0.04 g and having a post-meal intermeal interval of at least 10 min, as previously described (65, 74). A food intake event was considered a meal only when both criteria were met. Intermeal interval was defined as time between consecutive meals. Satiety ratio was defined as intermeal interval divided by meal size (min/g). Rates of oxygen consumption (o2; mL·kg−1·h−1) and carbon dioxide production (V̇co2; mL·kg−1·h−1) in each chamber were measured every 24 min throughout the studies. Respiratory exchange ratio (RER = V̇co2/V̇o2) was calculated by CLAMS software (version 4.02) to estimate relative oxidation of carbohydrates (RER = 1.0) versus fats (RER = 0.7), not accounting for protein oxidation. Energy expenditure (EE) was calculated as EE = V̇o2 × [3.815 + (1.232 × RER)] and normalized to body mass. Physical activities were measured by infrared beam breaks in the metabolic chamber. Average metabolic values were calculated per subject and averaged across subjects for statistical analysis by Student’s t test.

Glucose and insulin tolerance tests.

For glucose tolerance tests (GTTs), mice were fasted for 6 h before glucose injection. Glucose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was reconstituted in saline (0.9 g NaCl/L) and injected intraperitoneally (ip) at 1 mg/g body wt. Blood glucose was measured at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after glucose injection using a glucometer (NovaMax Plus, Billerica, MA). For insulin tolerance tests (ITTs), food was removed 2 h before insulin injection. Insulin was diluted in saline and injected at 1.0 U/kg body wt ip. Blood glucose was measured at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after insulin injection using the glucometer (NovaMax Plus).

Blood and tissue chemistry analysis.

Tail vein blood samples were allowed to clot on ice and then centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 g. Serum samples were stored at −80°C until analyzed. Serum triglycerides (TG) and cholesterol were measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions using an Infinity kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Middletown, VA). Nonesterified free fatty acids (NEFA) were measured using a Wako kit (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). Serum β-hydroxybutyrate (ketone) concentrations were measured with a StanBio Liquicolor kit (StanBio Laboratory, Boerne, TX). Serum insulin (Millipore, Burlington, MA) levels were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To measure liver TG content, frozen liver was weighed and homogenized in water, and an equal amount of homogenate was used for lipid extraction with a 2:1 solution of chloroform and methanol. The chloroform layer was dried in a SpeedVac and resuspended in a 3:1:1 solution of tert-butanol, methanol, and Triton X-100. TG measurements (Infinity kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were normalized to total protein content.

Adipose tissue histology and cell size quantification.

White adipose tissue (WAT) was fixed in formalin. Paraffin embedding, tissue sectioning, and staining with hematoxylin and eosin were performed at the Pathology Core facility at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Images were captured with a Keyence BZ-X700 All-in-One fluorescence microscope (Keyence Corp., Itasca, IL). Adipocyte cross-sectional area was measured on hematoxylin and eosin-stained adipose tissues slides using ImageJ software (55). All cells in one field of view at ×100 magnification per tissue section per mouse were analyzed. Analyses were performed on a total of 24 male (WT, n = 10; KO, n = 14) and 25 female (WT, n = 10; KO, n = 15) HFD-fed mice.

Statistical analyses.

All results are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed with two-tailed Student’s t tests or by repeated-measures ANOVA. For two-way ANOVA, we performed Bonferroni post hoc tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Generation of Ctrp4 loss-of-function mouse model.

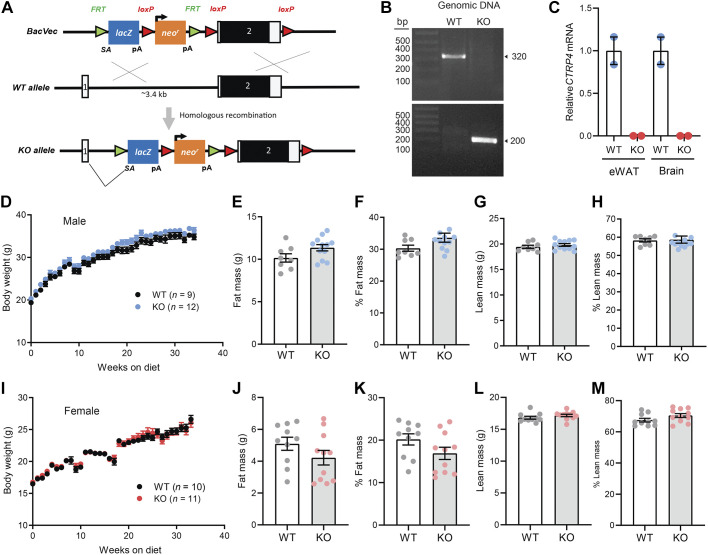

To disrupt expression of Ctrp4, a LacZ reporter with a splice site acceptor was inserted between exon 1 and 2 (Fig. 1A). Expression of the LacZ reporter is driven by the endogenous Ctrp4 gene promoter. Genotypes of the Ctrp4 WT+/+ and homozygous KO−/− alleles were confirmed by PCR (Fig. 1B). Quantitative real-time PCR showed the absence of Ctrp4 transcripts in adipose and brain (Fig. 1C), the two major tissues that express Ctrp4 mRNA, in KO mice (7). Ctrp4 KO mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio. Ctrp4 was not required for embryonic or postnatal development, as no gross developmental phenotypes were noted. Since recent studies have suggested an immune-related role for CTRP4 (34, 50), we performed a complete blood count analysis to determine whether CTRP4 deficiency alters circulating immune cell composition. With the exception of lower circulating eosinophil count in female KO compared with WT mice (P = 0.046), all the other blood cell counts (red blood cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, basophils) did not significantly differ between WT and KO mice of either sex (Table 1). Thus, CTRP4 is not required for normal immune cell development.

Fig. 1.

Body weights and composition of C1q/TNF-related protein-4 (Ctrp4) knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice fed a control low-fat diet (LFD). A: schematic of gene targeting strategy to generate Ctrp4 KO mice. A LacZ reporter with a splice site acceptor was inserted upstream of exon 2. FRT, flippase recognition target; LacZ, β-galactosidase; LoxP, sequence recognized by Cre recombinase; Neo, neomycin-resistant cassette. B: PCR-based genotyping of Ctrp4 KO and WT alleles. C: quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Ctrp4 mRNA expression in epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) and brain of WT and KO male mice (n = 2). D: body weights of Ctrp4 KO and WT male mice fed an LFD starting at 5 wk of age (WT, n = 9; KO, n = 12). E–H: body composition analysis of fat mass (E), %fat mass (relative to body weight; F), lean mass (G), and %lean mass (relative to body weight; H) of Ctrp4 KO and WT male mice fed an LFD at 38 wk of age (WT, n = 9; KO, n = 12). I: body weights of Ctrp4 KO and WT female mice fed an LFD starting at 5 wk of age (WT, n = 10; KO, n = 11). J–M: body composition analysis of fat mass (J), %fat mass (relative to body weight; K), lean mass (L), and %lean mass (relative to body weight; M) of Ctrp4 KO and WT female mice fed an LFD at 37 wk of age (WT, n = 10; KO, n = 11).

Table 1.

Complete blood count of Ctrp4 KO and WT mice (20 wk of age) fed a low-fat diet

| Male |

Female |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-fat diet | WT | KO | P | WT | KO | P |

| n | 8 | 12 | 10 | 11 | ||

| RBC, 106/μL | 9.55 ± 0.317 | 9.73 ± 0.48 | 0.357 | 9.57 ± 0.28 | 9.49 ± 0.65 | 0.714 |

| HGB, g/dL | 15.97 ± 0.49 | 16.24 ± 0.68 | 0.357 | 15.90 ± 0.41 | 15.7 ± 1.03 | 0.626 |

| HCT, % | 44.52 ± 1.25 | 45.47 ± 2.37 | 0.315 | 44.87 ± 1.53 | 44.08 ± 3.65 | 0.535 |

| MCV, fL | 46.62 ± 0.75 | 46.70 ± 0.62 | 0.790 | 46.88 ± 1.20 | 46.41 ± 1.29 | 0.400 |

| MCH, pg | 16.73 ± 0.18 | 16.70 ± 0.23 | 0.705 | 16.61 ± 0.23 | 16.57 ± 0.27 | 0.741 |

| MCHC, g/dL | 35.88 ± 0.56 | 35.74 ± 0.68 | 0.626 | 35.47 ± 0.87 | 35.74 ± 1.27 | 0.588 |

| RET, 103/μL | 448 ± 53 | 451 ± 117 | 0.945 | 382 ± 130 | 410 ± 82 | 0.557 |

| PLT, 103/μL | 1447 ± 224 | 1383 ± 166 | 0.473 | 1248 ± 177 | 1182 ± 175 | 0.398 |

| WBC, 103/μL | 12.34 ± 1.70 | 12.93 ± 1.70 | 0.464 | 10.05 ± 2.22 | 8.95 ± 2.34 | 0.285 |

| NEUT, 103/μL | 1.86 ± 0.82 | 2.11 ± 0.97 | 0.563 | 1.67 ± 0.50 | 1.75 ± 0.73 | 0.783 |

| LYMPH, 103/μL | 10.10 ± 1.67 | 10.37 ± 2.20 | 0.771 | 7.87 ± 1.88 | 6.81 ± 1.80 | 0.204 |

| MONO, 103/μL | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.256 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.18 ± 0.11 | 0.859 |

| EO, 103/μL | 0.26 ± 0.16 | 0.35 ± 0.15 | 0.203 | 0.33 ± 0.17 | 0.20 ± 0.09 | 0.046 |

| BASO, 103/μL | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.005 ± 0.007 | 0.268 | 0.008 ± 0.010 | 0.011 ± 0.011 | 0.548 |

Values are means ± SE. BASO, basophil count; CTRP4, C1q/TNF-related protein-4; EO, eosinophil count; HCT, hematocrit; HGB, hemoglobin; KO, knockout; LYMPH, lymphocyte count; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular (erythrocyte) volume; MONO, monocyte count; NEUT, neutrophil count; PLT, platelet count; RBC, red blood cell count; RET, reticulocyte count; WBC, white blood cell count; WT, wild type. Values in bold are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Loss of CTRP4 impairs glucose tolerance in male, but not female, mice fed a control LFD.

To determine the baseline requirement for CTRP4 in metabolic homeostasis, we monitored body weight gain in both male and female WT and Ctrp4 KO mice fed a control LFD. Body weight gain over time and absolute or relative (normalized to body weight) fat and lean mass based on quantitative magnetic resonance did not significantly differ between genotypes of both sexes (Fig. 1, D–M). For male mice, fasting body weight, blood glucose, serum TG, cholesterol, NEFA, and β-hydroxybutyrate (ketone) levels also did not differ between genotypes (Fig. 2, A–F). For female mice, fasting cholesterol levels were higher in KO mice relative to WT controls, whereas fasting body weight, blood glucose, serum TG, NEFA, and β-hydroxybutyrate levels did not significantly differ between genotypes (Fig. 2, G–L).

Fig. 2.

C1q/TNF-related protein-4 (Ctrp4) knockout (KO) male, but not female, mice fed a control low-fat diet (LFD) develop mild insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. A–F: overnight-fasted body weight (A), blood glucose (B), serum triglyceride (TG; C), serum cholesterol (D), serum nonesterified free fatty acids (NEFA; E), and serum β-hydroxybutyrate (F) of LFD-fed wild-type (WT; n = 9) and KO (n = 12) male mice at 14 wk of age (9 wk on LFD). G–L: overnight-fasted body weight (G), blood glucose (H), serum triglyceride (I), serum cholesterol (J), serum NEFA (K), and serum β-hydroxybutyrate (L) of LFD-fed WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 12) female mice at 14 wk of age (9 wk on LFD). M: fasting serum insulin levels of WT (n = 9) and KO (n = 12) male mice. N: blood glucose levels over time of WT (n = 9) and KO (n = 12) male mice in response to glucose tolerance tests (GTT). Mice were fed LFD for 14 wk. *P < 0.05 (2-way ANOVA). O: quantification of area under curve as shown in N. ***P < 0.001 (2-tailed Student’s t tests). P: fasting serum insulin levels of WT (n = 5) and KO (n = 8) female mice. Q: blood glucose levels over time of WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 12) female mice (on LFD for 14 wk) in response to GTT. R: blood glucose levels of WT (n = 9) and KO (n = 12) male mice (on LFD for 15 wk) in response to insulin tolerance test (ITT). S: blood glucose levels of WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 11) female mice (on LFD for 15 wk) in response to ITT.

Fasting insulin levels were significantly higher in Ctrp4 KO male mice relative to WT littermates (Fig. 2M), suggesting mild insulin resistance. Consistent with this, the ability of KO male mice to dispose of glucose in GTTs was significantly impaired relative to WT controls (Fig. 2, N and O). Although female KO mice trended to have higher fasting insulin levels compared with WT littermates (Fig. 2P), the rate of glucose disposal in response to GTTs was indistinguishable between genotypes (Fig. 2Q). When ITTs were performed to directly assess insulin action, no differences were noted in insulin-stimulated glucose disposal between genotypes of both sexes (Fig. 2, R and S).

Indirect calorimetry analyses on LFD-fed mice also did not uncover any differences in food intake, metabolic rate (V̇o2), EE, and total and ambulatory activity levels between genotypes of both sexes, regardless of the circadian cycle (light vs. dark) or metabolic status (ad libitum fed, overnight fasted, and refed) (Table 2). However, RER, reflecting carbohydrate versus fat oxidation, was significantly higher in KO female but not male mice compared with WT in the refeeding period following an overnight fast, indicating greater carbohydrate oxidation (Table 2). These data indicate that CTRP4 deficiency promotes mild insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in male mice but is otherwise dispensable for metabolic homeostasis under basal conditions when animals are fed a control LFD. With the exception of increased RER during fasting-refeeding, CTRP4 is not required for metabolic control under basal conditions in female mice.

Table 2.

Indirect calorimetry analysis of male (39 wk of age; on diet for 34 wk) and female (38 wk of age; on diet for 33 wk) Ctrp4 KO and WT littermates fed a control low-fat diet

| WT | KO | P | WT | KO | P | WT | KO | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-fat diet (male) | Ad libitum (dark cycle) | Ad libitum (light cycle) | Ad libitum (24-h) | ||||||

| n | 8 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 8 | 12 | |||

| Body weight, g | 35.21 ± 0.53 | 36.79 ± 0.56 | 0.070 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 2.996 ± 0.120 | 3.012 ± 0.083 | 0.909 | 1.157 ± 0.099 | 1.180 ± 0.100 | 0.876 | 4.153 ± 0.201 | 4.193 ± 0.158 | 0.863 |

| V̇o2, mL/kg/h | 2,751 ± 91 | 2,790 ± 67 | 0.733 | 2,375 ± 72 | 2,410 ± 47 | 0.680 | 2,559 ± 80 | 2,596 ± 55 | 0.703 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg/h | 2,834 ± 71 | 2,851 ± 69 | 0.868 | 2,207 ± 63 | 2,229 ± 55 | 0.804 | 2,514 ± 65 | 2,533 ± 58 | 0.829 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 1.032 ± 0.010 | 1.022 ± 0.006 | 0.365 | 0.927 ± 0.010 | 0.923 ± 0.010 | 0.779 | 0.979 ± 0.008 | 0.971 ± 0.006 | 0.487 |

| EE, kcal/kg/h | 13.98 ± 0.43 | 14.15 ± 0.34 | 0.762 | 11.78 ± 0.35 | 11.94 ± 0.24 | 0.705 | 12.86 ± 0.38 | 13.02 ± 0.28 | 0.730 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 23,404 ± 2,119 | 26,563 ± 2,398 | 0.367 | 10,438 ± 788 | 10,750 ± 626 | 0.759 | 33,842 ± 2,646 | 37,313 ± 2,957 | 0.422 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 11,920 ± 1,187 | 13,703 ± 1,519 | 0.408 | 4,271 ± 466 | 4,361 ± 467 | 0.899 | 16,192 ± 1,473 | 18,064 ± 1,874 | 0.481 |

| Fasting (dark cycle) | Fasting (light cycle) | Fasting (24-h) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 32.32 ± 0.51 | 33.82 ± 0.56 | 0.082 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – |

| V̇o2, mL/kg/h | 2,496 ± 68 | 2,562 ± 69 | 0.524 | 1,943 ± 52 | 2,003 ± 31 | 0.314 | 2,221 ± 59 | 2,285 ± 48 | 0.420 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg/h | 1,943 ± 47 | 1,991 ± 54 | 0.542 | 1,477 ± 36 | 1,524 ± 24 | 0.285 | 1,712 ± 41 | 1,760 ± 38 | 0.418 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 0.777 ± 0.003 | 0.776 ± 0.003 | 0.958 | 0.760 ± 0.002 | 0.761 ± 0.001 | 0.838 | 0.768 ± 0.003 | 0.769 ± 0.002 | 0.954 |

| EE, kcal/kg/h | 11.91 ± 0.31 | 12.22 ± 0.33 | 0.527 | 9.23 ± 0.24 | 9.52 ± 0.15 | 0.308 | 10.58 ± 0.27 | 10.88 ± 0.23 | 0.419 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 31,327 ± 2,727 | 36,948 ± 3,321 | 0.242 | 8,285 ± 1,010 | 9,342 ± 736 | 0.397 | 39,612 ± 3,566 | 46,290 ± 3,853 | 0.245 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 17,982 ± 1,665 | 20,956 ± 2,113 | 0.324 | 3,136 ± 321 | 3,981 ± 549 | 0.260 | 21,118 ± 1,903 | 24,938 ± 2,497 | 0.282 |

| Refeed (dark cycle) | Refeed (light cycle) | Refeed (24-h) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 34.37 ± 0.54 | 35.86 ± 0.64 | 0.122 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 3.201 ± 0.091 | 3.224 ± 0.083 | 0.858 | 1.132 ± 0.077 | 1.193 ± 0.095 | 0.653 | 4.333 ± 0.111 | 4.417 ± 0.104 | 0.599 |

| V̇o2, mL/kg/h | 2,646 ± 95 | 2,675 ± 51 | 0.769 | 2.242 ± 72 | 2,324 ± 36 | 0.280 | 2,456 ± 83 | 2,510 ± 42 | 0.532 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg/h | 2,645 ± 79 | 2,648 ± 48 | 0.968 | 2,206 ± 46 | 2,282 ± 27 | 0.150 | 2,438 ± 61 | 2,476 ± 35 | 0.576 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 1.001 ± 0.009 | 0.991 ± 0.005 | 0.357 | 0.987 ± 0.018 | 0.984 ± 0.011 | 0.867 | 0.994 ± 0.013 | 0.987 ± 0.007 | 0.645 |

| EE, kcal/kg/h | 13.35 ± 0.45 | 13.46 ± 0.25 | 0.811 | 11.27 ± 0.32 | 12.68 ± 0.16 | 0.235 | 12.37 ± 0.38 | 12.62 ± 0.20 | 0.536 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 24,055 ± 1,785 | 25,669 ± 1,450 | 0.491 | 8,116 ± 1,127 | 8,370 ± 351 | 0.803 | 32,171 ± 2,533 | 34,039 ± 1,724 | 0.534 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 11,791 ± 732 | 13,014 ± 959 | 0.367 | 3,114 ± 337 | 3,442 ± 378 | 0.551 | 14,906 ± 690 | 16,457 ± 1,267 | 0.363 |

| Low-fat diet (female) | Ad libitum (dark cycle) | Ad libitum (light cycle) | Ad libitum (24-h) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 | |||

| Body weight, g | 26.58 ± 0.61 | 26.05 ± 0.70 | 0.584 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 2.797 ± 0.129 | 3.108 ± 0.158 | 0.148 | 0.964 ± 0.106 | 1.167 ± 0.120 | 0.225 | 3.761 ± 0.196 | 4.274 ± 0.242 | 0.120 |

| V̇o2, mL/kg/h | 3640 ± 97 | 3624 ± 101 | 0.910 | 3075 ± 63 | 3082 ± 60 | 0.939 | 3361 ± 75 | 3357 ± 79 | 0.972 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg/h | 3654 ± 74 | 3712 ± 86 | 0.619 | 2802 ± 67 | 2887 ± 62 | 0.365 | 3232 ± 68 | 3305 ± 67 | 0.456 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 1.004 ± 0.015 | 1.026 ± 0.017 | 0.366 | 0.909 ± 0.011 | 0.936 ± 0.015 | 0.171 | 0.957 ± 0.011 | 0.982 ± 0.014 | 0.204 |

| EE, kcal/kg/h | 18.38 ± 0.44 | 18.39 ± 0.47 | 0.987 | 15.18 ± 0.31 | 15.31 ± 0.28 | 0.763 | 16.80 ± 0.36 | 16.88 ± 0.37 | 0.886 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 47,595 ± 5,060 | 45,117 ± 3,320 | 0.681 | 12,864 ± 903 | 15,088 ± 1,120 | 0.143 | 60,460 ± 5,073 | 60,205 ± 3,578 | 0.967 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 28,228 ± 3,874 | 25,223 ± 1,956 | 0.484 | 5,465 ± 292 | 7,127 ± 976 | 0.134 | 33,693 ± 3,811 | 32,351 ± 2,350 | 0.763 |

| Fasting (dark cycle) | Fasting (light cycle) | Fasting (24-h) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 23.87 ± 0.59 | 23.49 ± 0.70 | 0.694 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – |

| V̇o2, mL/kg/h | 3,074 ± 73 | 3,100 ± 110 | 0.852 | 2,312 ± 58 | 2,318 ± 57 | 0.945 | 2,703 ± 59 | 2,716 ± 80 | 0.896 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg/h | 2,372 ± 54 | 2,418 ± 75 | 0.635 | 1,790 ± 54 | 1,814 ± 42 | 0.729 | 2,088 ± 49 | 2,121 ± 56 | 0.664 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 0.770 ± 0.004 | 0.781 ± 0.004 | 0.109 | 0.772 ± 0.005 | 0.781 ± 0.004 | 0.190 | 0.771 ± 0.004 | 0.781 ± 0.004 | 0.131 |

| EE, kcal/kg/h | 14.65 ± 0.34 | 14.80 ± 0.51 | 0.810 | 11.03 ± 0.29 | 11.08 ± 0.26 | 0.898 | 12.88 ± 0.28 | 12.97 ± 0.37 | 0.850 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 57,742 ± 7,494 | 54,000 ± 4,052 | 0.657 | 12,092 ± 795 | 15,865 ± 1,716 | 0.068 | 69,834 ± 7,954 | 69,865 ± 5,071 | 0.997 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 37,977 ± 5,687 | 34,315 ± 2,799 | 0.559 | 6,241 ± 607 | 8,538 ± 1285 | 0.134 | 44,218 ± 6,106 | 42,853 ± 3,681 | 0.847 |

| Refeed (dark cycle) | Refeed (light cycle) | Refeed (24-h) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 25.59 ± 0.54 | 26.06 ± 0.76 | 0.629 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 3.781 ± 0.294 | 4.053 ± 0.143 | 0.401 | 1.056 ± 0.141 | 1.394 ± 0.115 | 0.077 | 4.837 ± 0.391 | 5.448 ± 0.240 | 0.191 |

| V̇o2, mL/kg/h | 3,419 ± 118 | 3,332 ± 120 | 0.613 | 2,901 ± 62 | 2,947 ± 76 | 0.648 | 3,193 ± 89 | 3,163 ± 96 | 0.825 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg/h | 3,488 ± 116 | 3,517 ± 105 | 0.852 | 2,853 ± 107 | 3,132 ± 60 | 0.032 | 3,211 ± 93 | 3,348 ± 73 | 0.257 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 1.019 ± 0.008 | 1.059 ± 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.982 ± 0.025 | 1.068 ± 0.017 | 0.011 | 1.003 ± 0.014 | 1.062 ± 0.013 | 0.007 |

| EE, kcal/kg/h | 17.34 ± 0.59 | 17.04 ± 0.58 | 0.727 | 14.58 ± 0.34 | 15.10 ± 0.35 | 0.306 | 16.13 ± 0.44 | 16.19 ± 0.45 | 0.929 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 46,678 ± 6,729 | 35,882 ± 4,677 | 0.196 | 9,557 ± 927 | 11,224 ± 813 | 0.190 | 56,235 ± 6,985 | 47,107 ± 4,628 | 0.281 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 27,328 ± 4,981 | 19,345 ± 3,039 | 0.178 | 4,135 ± 400 | 5,103 ± 653 | 0.232 | 31,463 ± 5,110 | 24,449 ± 3,194 | 0.250 |

Values are means ± SE. CTRP4, C1q/TNF-related protein-4; EE, energy expenditure; KO, knockout; V̇o2, rate of oxygen consumption; V̇co2, rate of carbon dioxide production; WT, wild type; RER, respiratory exchange ratio. Values in bold are significantly different (P < 0.05).

CTRP4 deficiency reduces body weight and adiposity in female mice fed an obesogenic HFD.

To determine the role of CTRP4 in modulating systemic metabolism in the context of metabolic stress, we measured body weight gain and other parameters in mice fed an obesogenic HFD. In male mice, loss of CTRP4 had no discernable impact on whole-body energy metabolism. Body weight gain over time, fat and lean mass, tissue (liver, heart, and kidney) weight, fasting blood glucose and serum insulin, TG, cholesterol, NEFA, and β-hydroxybutyrate levels, and GTTs and ITTs were indistinguishable between WT and KO male mice (Fig. 3, A–N and Table 3). In HFD-fed female mice, however, body weight was significantly lower in Ctrp4 KO relative to WT controls (Fig. 4, A and B). Lower body weight was due to significantly reduced fat mass but not lean mass, as assessed by quantitative magnetic resonance (Fig. 4, C–F). Of the two major fat depots [visceral: gonadal white adipose tissue (gWAT); and subcutaneous: inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT)] examined, relative visceral fat mass was significantly reduced in Ctrp4 KO female mice compared with WT controls (Table 3). Other tissue (liver, heart, and kidney) weights did not significantly differ between genotypes. Fasting blood glucose and serum TG, cholesterol, NEFA, and β-hydroxybutyrate levels did not significantly differ between WT and KO female mice (Fig. 4, G–K). Contrary to our expectation, despite reduced adiposity on an HFD compared with WT controls, female KO mice did not exhibit improved glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity: fasting insulin, GTTs, and ITTs did not significantly differ between genotypes (Fig. 4, L–N).

Fig. 3.

C1q/TNF-related protein-4 (CTRP4) deficiency does not affect metabolic phenotypes in male mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD). A: body weights over time of Ctrp4 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) male mice fed an HFD starting at 6 wk of age (WT, n = 9; KO, n = 15). B: total weight gained for WT and KO male mice after 14 wk on HFD. C–F: body composition analysis of fat mass (C), %fat mass (relative to body weight; D), lean mass (E), and %lean mass (relative to body weight; F) of Ctrp4 KO and WT male mice fed HFD (WT, n = 9; KO, n = 15). G–L: overnight-fasted blood glucose (G), serum triglyceride (TG; H), serum cholesterol (I), serum nonesterified free fatty acids (NEFA; J), serum β-hydroxybutyrate (K), and serum insulin (L) of HFD-fed WT (n = 9) and KO (n = 15) male mice. M and N: blood glucose levels over time of WT (n = 9) and KO (n = 15) male mice in response to glucose tolerance tests (GTT; M) and insulin tolerance tests (ITT; N). Mice were fed HFD for 15 wk.

Table 3.

Tissue weight of high fat diet-fed male and female mice (26 wk of age; fed diet for 17–18 wk) at termination of the study

| Variable | Male |

Female |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | KO | P | WT | KO | P | |

| n | 9 | 15 | 10 | 15 | ||

| Body weight, g | 46.24 ± 1.35 | 45.03 ± 1.14 | 0.521 | 36.49 ± 1.50 | 33.69 ± 1.15 | 0.042 |

| gWAT, g | 1.120 ± 0.053 | 1.118 ± 0.037 | 0.975 | 1.310 ± 0.125 | 0.986 ± 0.091 | 0.147 |

| gWAT/body weight | 2.54 ± 0.18 | 2.49 ± 0.13 | 0.852 | 3.52 ± 0.22 | 2.65 ± 0.28 | 0.038 |

| iWAT, g | 1.294 ± 0.080 | 1.226 ± 0.056 | 0.494 | 0.952 ± 0.087 | 0.766 ± 0.066 | 0.098 |

| iWAT/body weight | 2.85 ± 0.07 | 2.62 ± 0.08 | 0.129 | 2.56 ± 0.16 | 2.21 ± 0.15 | 0.160 |

| Liver weight, g | 1.972 ± 0.164 | 1.839 ± 0.119 | 0.513 | 1.145 ± 0.090 | 1.002 ± 0.030 | 0.094 |

| Liver weight/body weight | 4.28 ± 0.22 | 3.96 ± 0.18 | 0.311 | 3.14 ± 0.02 | 3.01 ± 0.43 | 0.540 |

| Heart weight, g | 0.184 ± 0.013 | 0.173 ± 0.006 | 0.396 | 0.173 ± 0.036 | 0.124 ± 0.002 | 0.114 |

| Kidney weight, g | 0.202 ± 0.004 | 0.190 ± 0.008 | 0.296 | 0.144 ± 0.003 | 0.137 ± 0.001 | 0.088 |

Values are means ± SE. gWAT, gonadal white adipose tissue; iWAT, inguinal white adipose tissue; KO, CTRP4 knockout; WT, wild type.

Fig. 4.

Loss of C1q/TNF-related protein-4 (CTRP4) reduces body weight and adiposity in female mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD). A: body weights over time of Ctrp4 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) female mice fed an HFD starting at 6 wk of age (WT, n = 10; KO, n = 15). B: total weight gained for WT and KO female mice after 13 wk on HFD. C–F: body composition analysis of fat mass (C), %fat mass (relative to body weight; D), lean mass (E), and %lean mass (relative to body weight; F) of HFD-fed Ctrp4 KO and WT female mice (WT, n = 10; KO, n = 15). G–K: overnight-fasted blood glucose (G), serum triglyceride (TG; H), serum cholesterol (I), serum nonesterified free fatty acids (NEFA; J), serum β-hydroxybutyrate (K), and serum insulin (L) of HFD-fed WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 15) female mice. M and N: blood glucose levels over time of WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 15) female mice in response to glucose tolerance tests (GTT; M) and insulin tolerance tests (ITT; N). Mice were fed HFD for 14 wk. * P < 0.05 (2-tailed Student’s t test).

CTRP4 deficiency does not affect hepatic lipid content and adipocyte cell size.

We next examined whether loss of CTRP4 affects lipid partitioning between adipose tissue and liver. Histological analyses as well as cell size quantification of gWAT and iWAT fat depots revealed no differences between genotypes of either sex (Fig. 5, A and B), despite female Ctrp4 KO mice being leaner with reduced adiposity compared with WT controls. In addition, WT and KO mice of either sex did not differ in circulating levels of adiponectin and leptin (Fig. 5, C and D). Because HFD-fed female KO mice had lower body weight, we expected these mice to have lower hepatic lipid content relative to WT animals; yet quantification of hepatic TG content did not reveal any differences between genotypes of either sex (Fig. 5, E and F).

Fig. 5.

Impact of C1q/TNF-related protein-4 (CTRP4) deficiency on adipocyte cell size, serum adipokine levels, and hepatic lipid contents of male and female mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD). A and B: quantification of adipocyte cell size in gonadal white adipose tissue (gWAT) and inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT) of wild-type (WT; n = 8–9) and knockout (KO; n = 15) male mice (A) and WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 14–15) female mice (B). C and D: serum adiponectin and leptin levels of WT (n = 9) and KO (n = 15) male mice (C) and WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 15) female mice (D). E and F: hepatic triglyceride levels in WT (n = 9) and KO (n = 15) male mice (E) and WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 15) female mice (F).

Loss of CTRP4 alters food intake, respiratory exchange ratio, and energy expenditure.

To better understand the possible physiological mechanism underlying reduced weight gain and adiposity in female but not male mice fed an HFD, we performed indirect calorimetry analyses on these animals. We found no significant differences in any of the parameters measured (food intake, metabolic rate, RER, EE, and physical activity) in the male HFD-fed mice irrespective of circadian cycle (light vs. dark) or metabolic status (ad libitum fed, overnight fasted, refed) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Indirect calorimetry analysis of male (23 wk of age; on diet for 17 wk) and female (24 wk of age; on diet for 18 wk) Ctrp4 KO and WT littermates fed a high-fat diet

| WT | KO | P | WT | KO | P | WT | KO | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-fat diet (male) | Ad libitum (dark cycle) | Ad libitum (light cycle) | Ad libitum (24-h) | ||||||

| n | 7 | 14 | 7 | 14 | 7 | 14 | |||

| Body weight, g | 40.4 ± 1.08 | 40.7 ± 0.90 | 0.825 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 1.98 ± 0.122 | 1.89 ± 0.093 | 0.547 | 0.473 ± 0.078 | 0.59 ± 0.029 | 0.1024 | 2.45 ± 0.190 | 2.47 ± 0.111 | 0.9237 |

| V̇o2, mL/kg body mass/h | 2,327 ± 101 | 2,326 ± 48 | 0.991 | 2,018 ± 82 | 2,025 ± 35 | 0.928 | 2,173 ± 90 | 2,176 ± 40 | 0.968 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg body mass/h | 1,958 ± 91 | 1,936 ± 42 | 0.799 | 1,657 ± 70 | 1,664 ± 30 | 0.912 | 1,807 ± 79 | 1,800 ± 35 | 0.925 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 0.841 ± 0.007 | 0.832 ± 0.003 | 0.223 | 0.820 ± 0.006 | 0.821 ± 0.002 | 0.875 | 0.830 ± 0.006 | 0.826 ± 0.002 | 0.510 |

| EE, kcal/kg body mass/h | 11.29 ± 0.49 | 11.26 ± 0.23 | 0.947 | 9.74 ± 0.40 | 9.78 ± 0.17 | 0.924 | 10.51 ± 0.44 | 10.51 ± 0.20 | 0.992 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 18,846 ± 2,081 | 18,909 ± 1,729 | 0.983 | 7,613 ± 328 | 6,057 ± 493 | 0.050 | 26,459 ± 2,129 | 24,966 ± 2,145 | 0.666 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 8,352 ± 1,184 | 9,067 ± 1,011 | 0.672 | 2,444 ± 277 | 1,955 ± 167 | 0.126 | 10,796 ± 1,168 | 11,023 ± 1,146 | 0.903 |

| Fasting (dark cycle) | Fasting (light cycle) | Fasting (24-h) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 38.3 ± 1.18 | 38.2 ± 0.89 | 0.970 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| V̇o2, mL/kg body mass/h | 2,094 ± 110 | 2,127 ± 42 | 0.739 | 1,740 ± 73 | 1,724 ± 37 | 0.823 | 1,919 ± 89 | 1,927 ± 38 | 0.924 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg body mass/h | 1,633 ± 90 | 1,652 ± 31 | 0.805 | 1,367 ± 58 | 1,353 ± 30 | 0.809 | 1,501 ± 72 | 1,503 ± 29 | 0.971 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 0.779 ± 0.002 | 0.777 ± 0.002 | 0.465 | 0.786 ± 0.002 | 0.785 ± 0.001 | 0.843 | 0.782 ± 0.002 | 0.781 ± 0.001 | 0.591 |

| EE, kcal/kg body mass/h | 10.00 ± 0.52 | 10.15 ± 0.20 | 0.752 | 8.33 ± 0.35 | 8.24 ± 0.18 | 0.819 | 9.17 ± 0.43 | 9.20 ± 0.18 | 0.933 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 25,105 ± 3,036 | 25,409 ± 1,610 | 0.923 | 7,030 ± 469 | 6,527 ± 821 | 0.685 | 32,135 ± 3,248 | 31,936 ± 2,145 | 0.959 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 12,507 ± 1,698 | 13,798 ± 971 | 0.486 | 2,433 ± 327 | 2,424 ± 351 | 0.988 | 14,940 ± 1,800 | 16,222 ± 1,056 | 0.520 |

| Refeed (dark cycle) | Refeed (light cycle) | Refeed (24-h) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 39.3 ± 3.26 | 39.4 ± 3.26 | 0.955 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 1.95 ± 0.040 | 2.08 ± 0.095 | 0.343 | 0.507 ± 0.042 | 0.491 ± 0.028 | 0.7438 | 2.45 ± 0.064 | 2.57 ± 0.110 | 0.476 |

| V̇o2, mL/kg body mass/h | 2,301 ± 85 | 2,269 ± 44 | 0.713 | 1,986 ± 68 | 1,944 ± 34 | 0.539 | 2,154 ± 77 | 2,117 ± 38 | 0.633 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg body mass/h | 1,899 ± 73 | 1,870 ± 41 | 0.717 | 1,670 ± 58 | 1,629 ± 30 | 0.494 | 1,791 ± 66 | 1,757 ± 35 | 0.617 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 0.825 ± 0.003 | 0.824 ± 0.003 | 0.753 | 0.840 ± 0.004 | 0.837 ± 0.003 | 0.582 | 0.832 ± 0.004 | 0.830 ± 0.003 | 0.648 |

| EE, kcal/kg body mass/h | 11.12 ± 0.41 | 10.96 ± 0.22 | 0.713 | 9.64 ± 0.33 | 9.42 ± 0.16 | 0.528 | 10.42 ± 0.37 | 10.24 ± 0.19 | 0.629 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 19,601 ± 2,249 | 19,001 ± 1,625 | 0.832 | 6,552 ± 542 | 5,306 ± 506 | 0.144 | 26,152 ± 2,287 | 24,307 ± 2,001 | 0.579 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 8,719 ± 1,288 | 8,933 ± 824 | 0.886 | 2,073 ± 190 | 1,827 ± 176 | 0.398 | 10,791 ± 1,262 | 10,760 ± 921 | 0.984 |

| High-fat diet (female) | Ad libitum (dark cycle) | Ad libitum (light cycle) | Ad libitum (24-h) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 13 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 13 | |||

| Body weight, g | 33.48 ± 1.45 | 29.46 ± 1.10 | 0.035 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 2.01 ± 0.102 | 2.05 ± 0.105 | 0.795 | 0.64 ± 0.095 | 0.66 ± 0.046 | 0.850 | 2.65 ± 0.156 | 2.71 ± 0.111 | 0.780 |

| V̇o2, mL/kg body mass/h | 3,045 ± 148 | 3,220 ± 104 | 0.332 | 2,565 ± 88 | 2,719 ± 65 | 0.166 | 2,805 ± 117 | 2,971 ± 83 | 0.248 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg body mass/h | 2,464 ± 111 | 2,642 ± 91 | 0.224 | 2,038 ± 67 | 2,193 ± 59 | 0.099 | 2,251 ± 88 | 2,419 ± 74 | 0.157 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 0.809 ± 0.006 | 0.8187 ± 0.004 | 0.255 | 0.794 ± 0.005 | 0.804 ± 0.003 | 0.112 | 0.802 ± 0.005 | 0.811 ± 0.003 | 0.158 |

| EE, kcal/kg body mass/h | 14.65 ± 0.70 | 15.54 ± 0.51 | 0.306 | 12.30 ± 0.42 | 13.08 ± 0.32 | 0.148 | 13.47 ± 0.55 | 14.31 ± 0.41 | 0.225 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 38,478 ± 5,979 | 37,229 ± 3,011 | 0.843 | 12,077 ± 1,161 | 13,662 ± 1,225 | 0.370 | 50,555 ± 6,630 | 50,891 ± 3,815 | 0.963 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 21,124 ± 4,566 | 19,121 ± 1,747 | 0.657 | 4,875 ± 630 | 5,702 ± 540 | 0.329 | 26,000 ± 5,052 | 24,824 ± 2,001 | 0.815 |

| Fasting (dark cycle) | Fasting (light cycle) | Fasting (24-h) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 30.93 ± 1.47 | 26.77 ± 1.12 | 0.033 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| V̇o2, mL/kg body mass/h | 2,800 ± 107 | 2930 ± 88 | 0.350 | 2,132 ± 57 | 2,162 ± 47 | 0.694 | 2,466 ± 79 | 2,546 ± 63 | 0.429 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg body mass/h | 2,104 ± 79 | 2,214 ± 69 | 0.306 | 1,617 ± 41 | 1,635 ± 37 | 0.745 | 1,861 ± 58 | 1,925 ± 49 | 0.402 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 0.752 ± 0.001 | 0.754 ± 0.002 | 0.291 | 0.758 ± 0.001 | 0.754 ± 0.002 | 0.209 | 0.755 ± 0.001 | 0.754 ± 0.001 | 0.697 |

| EE, kcal/kg body mass/h | 13.27 ± 0.50 | 13.91 ± 0.42 | 0.341 | 10.12 ± 0.27 | 10.26 ± 0.22 | 0.704 | 11.70 ± 0.37 | 12.09 ± 0.30 | 0.423 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 49,265 ± 6,043 | 58,851 ± 5,207 | 0.242 | 14,380 ± 1,933 | 14,891 ± 1,427 | 0.830 | 63,646 ± 6,712 | 73,743 ± 6,240 | 0.287 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 29,858 ± 4,438 | 36,756 ± 3,706 | 0.243 | 7,424 ± 1,968 | 7,386 ± 831 | 0.985 | 37,281 ± 5,465 | 44,142 ± 4,360 | 0.332 |

| Refeed (dark cycle) | Refeed (light cycle) | Refeed (24-h) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 32.20 ± 1.381 | 28.73 ± 0.989 | 0.048 | ||||||

| Food intake, g | 2.67 ± 0.094 | 2.91 ± 0.073 | 0.051 | 0.68 ± 0.056 | 0.79 ± 0.047 | 0.137 | 3.34 ± 0.121 | 3.70 ± 0.095 | 0.029 |

| V̇o2, mL/kg body mass/h | 2,835 ± 99 | 2,991 ± 65 | 0.186 | 2,453 ± 72 | 2,663 ± 55 | 0.028 | 2,650 ± 83 | 2,832 ± 59 | 0.078 |

| V̇co2, mL/kg body mass/h | 2,338 ± 79 | 2,533 ± 64 | 0.068 | 2,031 ± 67 | 2,263 ± 59 | 0.017 | 2,189 ± 71 | 2,402 ± 61 | 0.033 |

| RER (V̇co2/V̇o2) | 0.825 ± 0.005 | 0.846 ± 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.826 ± 0.006 | 0.847 ± 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.825 ± 0.006 | 0.846 ± 0.005 | 0.016 |

| EE, kcal/kg body mass/h | 13.70 ± 0.47 | 14.53 ± 0.33 | 0.149 | 11.86 ± 0.36 | 12.95 ± 0.28 | 0.024 | 12.81 ± 0.40 | 13.77 ± 0.30 | 0.063 |

| Total activity (beam breaks) | 35,244 ± 3,010 | 29,018 ± 1,917 | 0.083 | 10,892 ± 1,201 | 1,2027 ± 972 | 0.466 | 46,136 ± 3,833 | 41,045 ± 2,692 | 0.275 |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 18,539 ± 2,212 | 14,066 ± 932 | 0.055 | 4,559 ± 575 | 4,790 ± 324 | 0.716 | 23,098 ± 2,607 | 18,856 ± 1,126 | 0.119 |

Values are means ± SE. CTRP4, C1q/TNF-related protein-4; EE, energy expenditure; KO, knockout; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; V̇co2, rate of carbon dioxide production; V̇o2, rate of oxygen consumption; WT, wild type. Values in bold are significantly different (P < 0.05).

In female KO mice with reduced body weight, however, energy expenditure trended higher, irrespective of circadian cycle or nutritional state (fed, fasted, refed) (Table 4). Other metabolic parameters (metabolic rate, RER, total and ambulatory activity levels) did not significantly differ between ad libitum-fed WT and KO female mice. Interestingly, when subjected to an overnight fast followed by refeeding, Ctrp4 KO female mice consumed significantly more food during the next 24 h of refeeding, driven largely by greater food intake during the dark cycle. Also, RER was consistently and significantly higher during the refed period in Ctrp4 KO female mice relative to WT controls in both the light and dark cycle (Table 4), indicating greater carbohydrate oxidation. In the light cycle of the refed period, female KO mice also had significantly higher EE relative to WT controls (P = 0.024).

CTRP4 deficiency affects food intake behaviors.

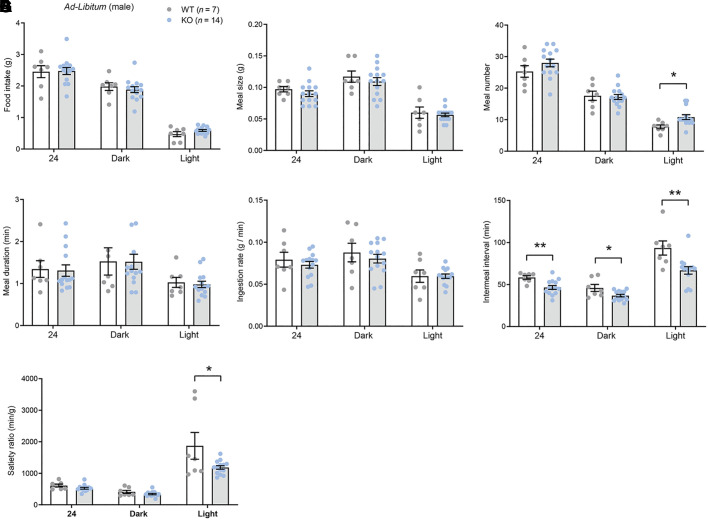

On the basis of our previous findings that CTRP4 might have a CNS role in regulating ingestive physiology (7), we examined in greater detail the food intake patterns and behavior during the ad libitum state and in response to fasting and refeeding. When food was freely available (ad libitum), male KO mice consumed similar amounts of food as the WT controls (Fig. 6A). Meal size, meal duration, and ingestion rate were also not different between genotypes (Fig. 6, B–E). However, meal number (or meal frequency) was higher, whereas intermeal interval and satiety ratio were significantly lower, in KO male mice relative to WT controls (Fig. 6, C, F, and G). In the refeeding period immediately following an overnight fast, male KO mice tended to consume more food during the first 4 h when food became available (Fig. 6H) but were otherwise not different from WT controls in cumulative food intake, meal size, meal number, meal duration, ingestion rate, intermeal interval, and satiety ratio irrespective of the circadian cycle (Fig. 6I–O).

Fig. 6.

C1q/TNF-related protein-4 (CTRP4)-deficient male mice fed ad libitum have greater meal number, shorter intermeal interval and reduced satiety ratio. A–F: food intake (A), meal size (B), meal number (C), meal duration (D), ingestion rate (E), intermeal interval (F), and satiety ratio (G) over a 24-h period or during the light or dark cycle for wild-type (WT; = 7) and knockout (KO; = 14) male mice fed ad libitum. H: food intake of WT (n = 7) and KO (n = 14) male mice during the first 4 h of refeeding after an overnight fast. I–O: food intake (I), meal size (J), meal number (K), meal duration (L), ingestion rate (M), intermeal interval (N), and satiety ratio (O) of WT (n = 7) and KO (n = 14) male mice over a 24-h period or during the light or dark cycle of refeeding following an overnight fast. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (2-tailed Student’s t test).

In ad libitum-fed female mice, none of the feeding parameters were significantly different between genotypes (Fig. 7, A–G). However, when subjected to an overnight fast followed by refeeding, Ctrp4 KO female mice consumed significantly more food compared with WT controls (Fig. 7, H and I), driven by increased meal duration (Fig. 7L) and reduced satiety ratio (Fig. 7O), without any significant differences in meal size, meal number, or intermeal interval (Fig. 7, J, K, and N). The ingestion rate was lower in KO female mice during the light cycle (Fig. 7M). These data indicate that loss of CTRP4 affects microstructures of food intake patterns and behaviors in male and female mice.

Fig. 7.

Female mice lacking C1q/TNF-related protein-4 (CTRP4) have increased food intake, greater meal duration, and reduced satiety ratio in response to fasting and refeeding. A–F: food intake (A), meal size (B), meal number (C), meal duration (D), ingestion rate (E), intermeal interval (F), and satiety ratio (G) over a 24-h period or during the light or dark cycle for wild-type (WT; = 10) and knockout (KO; = 12) female mice fed ad libitum. H: food intake of WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 12) female mice during the first 4 h of refeeding after an overnight fast. I–O: food intake (I), meal size (J), meal number (K), meal duration (L), ingestion rate (M), intermeal interval (N), and satiety ratio (O) of WT (n = 10) and KO (n = 12) female mice over a 24-h period or during the light or dark cycle of refeeding following an overnight fast. *P < 0.05 (2-tailed Student's t test).

DISCUSSION

These studies show that loss of CTRP4 affects systemic metabolism in a diet-dependent and sexually dimorphic manner. Under basal conditions when mice were fed a control LFD, only male KO mice developed mild insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. In the context of an obesogenic diet, only female KO mice had reduced weight gain and adiposity. Both obese male and female KO mice, however, had altered feeding patterns and behaviors during the refeeding period following food deprivation, suggestive of decreased within-meal satiety. These observations together provide the first evidence for a physiological role of CTRP4 in modulating ingestive physiology and systemic metabolism.

Sexual dimorphism in disease susceptibility and outcomes is commonly noted (3, 6, 13, 35, 41, 63, 64). It is often assumed that sex hormones affect metabolic physiology by acting differentially on metabolic tissues (35, 36, 41, 64). In mice and rats, significant differences in HFD-induced weight gain, adiposity, and insulin resistance are well documented (14, 16, 19, 24, 38, 40, 48). In general, when differences in metabolic phenotypes are observed between sexes, the outcomes could be that 1) only one sex is affected; 2) both males and females are affected but to different degrees; or 3) the sexes have opposite responses. When fed a control LFD, loss of CTRP4 affected only male mice. High-fat feeding, in contrast, only impacted female mice. Some of the obvious and potential mechanisms that could account for sexually dimorphic phenotypes include the following: 1) differences in plasma adipokine levels (e.g., leptin and adiponectin) between sexes (11, 20, 37, 54), although we observed no differences in serum leptin and adiponectin levels between genotypes of either sex fed an HFD; 2) sex hormones can have direct and indirect effects on metabolism (19, 35, 36), and we do not currently know whether circulating estradiol and/or testosterone differs between WT and Ctrp4 KO animals; and 3) sex-specific differences in sympathetic activation of adipose tissue lipolysis (32, 33, 42, 51, 52), with increased lipolysis in Ctrp4 KO female mice resulting in lower adiposity. However, measurements of fasting serum free fatty acids (a marker of adipose lipolysis) and β-hydroxybutyrate (ketones, a marker of hepatic fat oxidation) did not reveal any differences between genotypes of either sex. We thus rule out the potential contribution of leptin, adiponectin, and adipose lipolysis as a likely cause for the reduced weight gain seen in HFD-fed Ctrp4 KO female mice.

The higher fasting serum cholesterol and insulin levels as well as the reduced glucose tolerance of LFD-fed KO male mice cannot be attributed to differences in body weight or adiposity, as neither significantly differed between genotypes. Peripheral tissue-derived hormones such as leptin can regulate glucose output and uptake in peripheral tissues as well as lipid synthesis in liver via direct action in the CNS (2, 25). Because CTRP4 is most highly expressed in the brain, we cannot rule out that mild insulin resistance and glucose intolerance are due to deficit in CTRP4 action in the CNS. Hepatic gluconeogenesis plays a major role in regulating blood glucose levels during an overnight fast (49). We did not observe any differences in overnight fasting blood glucose between WT and KO male mice; intracerebroventricular injection of recombinant CTRP4 also does not affect glucose tolerance in chow- or HFD-fed WT male mice (7). These observations likely argue against a central role of CTRP4 in modulating insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. Since CTRP4 is also expressed in peripheral tissues (albeit at a lower level than in the brain) and circulates in blood (7), it is likely that CTRP4 exerts a paracrine and/or endocrine role in the periphery to regulate insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, and fasting plasma cholesterol levels. Further studies are needed to help uncover the target tissues of CTRP4 and its mode of action in peripheral tissues.

When challenged with an obesogenic diet, Ctrp4 KO female mice gained significantly less body weight and adiposity than WT littermates. The reason for this is not obvious: reduced weight gain was not due to increased physical activity or decreased caloric intake when fed ad libitum, as these parameters did not differ between genotypes. EE data, while not significant, did consistently trend higher in Ctrp4 KO females compared with WT controls when fed ad libitum. Additionally, in the refed period after a fast, female KO mice displayed significantly higher EE in the light cycle compared with WT controls. We presume that, over time, modest differences in energy expenditure could potentially contribute in a biologically meaningful way to reduced weight gain and adiposity seen in HFD-fed KO female mice. Alternatively, loss of CTRP4 might adversely affect nutrient absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Overexpression of CTRP4 at high levels (driven by a ubiquitous cytomegalovirus promoter) in transgenic mice protects the gut from dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis (34). However, there are no available data demonstrating direct action of CTRP4 on enterocytes or the mesenteric nervous system. Additional studies are needed to rule out a role for CTRP4 in nutrient absorption in the gut.

In contrast to CTRP4-deficient mice, WT mice reduce EE when CTRP4 is centrally delivered through the lateral ventricle (7). Our data from Ctrp4 KO mice reaffirm the physiological relevance of our previous findings that CTRP4 acts in the CNS to modulate EE. Although RER did not differ when animals were fed ad libitum, it was significantly increased in KO female mice over a 24-h refeeding period (in both light and dark cycles) following an overnight fast, indicating greater carbohydrate oxidation. This phenomenon was independent of diet. In contrast to CTRP4-deficient mice, chow- or HFD-fed WT mice injected centrally with CTRP4 have significantly reduced RER, reflecting greater fat oxidation (7). These observations also underscore the physiological relevance of centrally acting CTRP4 in modulating substrate metabolism in peripheral tissues.

When mice were fed ad libitum with a control LFD, we did not observe any differences in food intake between genotypes of either sex. However, when fed an HFD, we noted differences in feeding patterns and behaviors between male and female KO mice relative to their WT counterparts. In male KO mice, ad libitum food intake was similar to that of WT controls. Despite similar meal size, meal duration, and ingestion rate as WT, the male KO mice had significantly greater meal number (or meal frequency) and reduced intermeal interval and satiety ratio, especially during the light cycle. When subjected to food deprivation followed by reintroduction of food, male KO mice tended to consume more food and had slightly larger meal number. In female mice fed ad libitum HFD, food intake patterns were not significantly different from those of WT controls. However, when subjected to an overnight fast followed by refeeding, Ctrp4 KO female mice consumed significantly more food, especially during the first 4 h, when food was reintroduced. Increased food intake following food deprivation was due to increased meal duration and reduced satiety ratio, especially in the light cycle. These results suggest a CNS role for CTRP4 in modulating fine structures of food intake patterns and behaviors in male and female mice that are contingent on the nutritional states (ad libitum vs. fasted/refed) and circadian cycle of the animals. Consistent with these findings, expression of Ctrp4 mRNA is upregulated in the hypothalamus in the refed state relative to the fasted state in WT mice, and central injection of CTRP4 into the lateral ventricle suppresses food intake (7). Suppression of food intake was seen only when CTRP4 was delivered centrally and not if the protein was delivered to the peripheral circulation via intraperitoneal injection. Together, our previous studies and current findings suggest that CTRP4 may play a central role in modulating food intake in the refed state to prevent overconsumption, especially following food deprivation.

The site of action and mechanism by which CTRP4 acts in the brain to modulate food intake patterns and behaviors are currently unknown. We (7) previously showed that neurons (and not astrocytes) express Ctrp4 transcripts and that expression within the CNS is widespread. The neurocircuitry governing food intake (1, 9, 15, 39), meal size, and meal patterns (4, 5, 17, 26, 56, 59, 73) is complex and involves cross talk among the hypothalamus, hindbrain, and other brain regions. Despite widespread expression in the brain, it is likely that CTRP4 acts on the hypothalamus (e.g., proopiomelanocortin and agouti-related protein neurons within the arcuate nucleus) and hindbrain (e.g., neurons of the nucleus of the solitary tract) to modulate food intake and meal size. These sites within the CNS play critical roles in controlling ingestive physiology (12, 23, 26, 73). Further studies are required to confirm the sites of action for CTRP4 in the brain.

In summary, we provide the first detailed analyses of metabolic phenotypes resulting from a loss of CTRP4. Our study also represents the first functional dissection of CTRP4 in a physiological context, overcoming some of the caveats associated with previous studies employing recombinant protein infusion or transgenic overexpression. The impact of CTRP4 deficiency on metabolic outcomes is sex and diet dependent, underscoring the complexity of gene–environment interactions influencing metabolic health. One limitation of the study is the use of a whole body KO mouse model from conception, where one cannot rule out potential physiological compensation; this issue can be addressed in future studies using a conditional KO model in adult animals. In light of the dearth of information concerning CTRP4, our study provides an important foundation and context to further unravel its biological function and relevance to pathophysiology.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK-084171 to G.W.W.), a predoctoral fellowship from the Ford Foundation (to A.N.S), a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Diabetes Association (1-18-PMF-022 to S.R.), and a predoctoral fellowship from NIH (F31 DK-116537 to H.C.L.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.C.S., A.N.S., and G.W.W. conceived and designed research; D.C.S., A.N.S., S.R., H.C.L. and S.A. performed experiments; D.C.S., A.N.S. and S.A. analyzed data; D.C.S., A.N.S., S.A., and G.W.W. interpreted results of experiments; D.C.S. and A.N.S. prepared figures; G.W.W. drafted manuscript; D.C.S., S.R., H.C.L., S.A., and G.W.W. edited and revised manuscript; D.C.S., A.N.S., S.R., H.C.L., S.A., and G.W.W. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andermann ML, Lowell BB. Toward a wiring diagram understanding of appetite control. Neuron 95: 757–778, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asilmaz E, Cohen P, Miyazaki M, Dobrzyn P, Ueki K, Fayzikhodjaeva G, Soukas AA, Kahn CR, Ntambi JM, Socci ND, Friedman JM. Site and mechanism of leptin action in a rodent form of congenital lipodystrophy. J Clin Invest 113: 414–424, 2004. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babapour Mofrad R, van der Flier WM. Nature and implications of sex differences in AD pathology. Nat Rev Neurol 15: 6–8, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berthoud HR, Sutton GM, Townsend RL, Patterson LM, Zheng H. Brainstem mechanisms integrating gut-derived satiety signals and descending forebrain information in the control of meal size. Physiol Behav 89: 517–524, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blevins JE, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG. Evidence that paraventricular nucleus oxytocin neurons link hypothalamic leptin action to caudal brain stem nuclei controlling meal size. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R87–R96, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00604.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Böhm C, Benz V, Clemenz M, Sprang C, Höft B, Kintscher U, Foryst-Ludwig A. Sexual dimorphism in obesity-mediated left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305: H211–H218, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00593.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byerly MS, Petersen PS, Ramamurthy S, Seldin MM, Lei X, Provost E, Wei Z, Ronnett GV, Wong GW. C1q/TNF-related protein 4 (CTRP4) is a unique secreted protein with two tandem C1q domains that functions in the hypothalamus to modulate food intake and body weight. J Biol Chem 289: 4055–4069, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.506956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byerly MS, Swanson R, Wei Z, Seldin MM, McCulloh PS, Wong GW. A central role for C1q/TNF-related protein 13 (CTRP13) in modulating food intake and body weight. PLoS One 8: e62862, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemmensen C, Müller TD, Woods SC, Berthoud HR, Seeley RJ, Tschöp MH. Gut-brain cross-talk in metabolic control. Cell 168: 758–774, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coll AP, Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S. The hormonal control of food intake. Cell 129: 251–262, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Combs TP, Berg AH, Rajala MW, Klebanov S, Iyengar P, Jimenez-Chillaron JC, Patti ME, Klein SL, Weinstein RS, Scherer PE. Sexual differentiation, pregnancy, calorie restriction, and aging affect the adipocyte-specific secretory protein adiponectin. Diabetes 52: 268–276, 2003. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cone RD, Cowley MA, Butler AA, Fan W, Marks DL, Low MJ. The arcuate nucleus as a conduit for diverse signals relevant to energy homeostasis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25, Suppl 5: S63–S67, 2001. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Florio DN, Sin J, Coronado MJ, Atwal PS, Fairweather D. Sex differences in inflammation, redox biology, mitochondria and autoimmunity. Redox Biol 31: 101482, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Akoum S, Lamontagne V, Cloutier I, Tanguay JF. Nature of fatty acids in high fat diets differentially delineates obesity-linked metabolic syndrome components in male and female C57BL/6J mice. Diabetol Metab Syndr 3: 34, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-3-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gautron L, Elmquist JK, Williams KW. Neural control of energy balance: translating circuits to therapies. Cell 161: 133–145, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goren HJ, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR. Glucose homeostasis and tissue transcript content of insulin signaling intermediates in four inbred strains of mice: C57BL/6, C57BLKS/6, DBA/2, and 129X1. Endocrinology 145: 3307–3323, 2004. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grill HJ Leptin and the systems neuroscience of meal size control. Front Neuroendocrinol 31: 61–78, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grill HJ, Kaplan JM. The neuroanatomical axis for control of energy balance. Front Neuroendocrinol 23: 2–40, 2002. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grove KL, Fried SK, Greenberg AS, Xiao XQ, Clegg DJ. A microarray analysis of sexual dimorphism of adipose tissues in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice. Int J Obes 34: 989–1000, 2010. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gui Y, Silha JV, Murphy LJ. Sexual dimorphism and regulation of resistin, adiponectin, and leptin expression in the mouse. Obes Res 12: 1481–1491, 2004. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta R, Nguyen DC, Schaid MD, Lei X, Balamurugan AN, Wong GW, Kim JA, Koltes JE, Kimple ME, Bhatnagar S. Complement 1q-like-3 protein inhibits insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells via the cell adhesion G protein-coupled receptor BAI3. J Biol Chem 293: 18086–18098, 2018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han S, Park JS, Lee S, Jeong AL, Oh KS, Ka HI, Choi HJ, Son WC, Lee WY, Oh SJ, Lim JS, Lee MS, Yang Y. CTRP1 protects against diet-induced hyperglycemia by enhancing glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation. J Nutr Biochem 27: 43–52, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes MR, Skibicka KP, Leichner TM, Guarnieri DJ, DiLeone RJ, Bence KK, Grill HJ. Endogenous leptin signaling in the caudal nucleus tractus solitarius and area postrema is required for energy balance regulation. Cell Metab 11: 77–83, 2010. [Erratum in Cell Metab 23:744, 2016]. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingvorsen C, Karp NA, Lelliott CJ. The role of sex and body weight on the metabolic effects of high-fat diet in C57BL/6N mice. Nutr Diabetes 7: e261, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2017.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamohara S, Burcelin R, Halaas JL, Friedman JM, Charron MJ. Acute stimulation of glucose metabolism in mice by leptin treatment. Nature 389: 374–377, 1997. doi: 10.1038/38717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanoski SE, Zhao S, Guarnieri DJ, DiLeone RJ, Yan J, De Jonghe BC, Bence KK, Hayes MR, Grill HJ. Endogenous leptin receptor signaling in the medial nucleus tractus solitarius affects meal size and potentiates intestinal satiation signals. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 303: E496–E503, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00205.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei X, Liu L, Terrillion CE, Karuppagounder SS, Cisternas P, Lay M, Martinelli DC, Aja S, Dong X, Pletnikov MV, Wong GW. FAM19A1, a brain-enriched and metabolically responsive neurokine, regulates food intake patterns and mouse behaviors. FASEB J 33: 14734–14747, 2019. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901232RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei X, Rodriguez S, Petersen PS, Seldin MM, Bowman CE, Wolfgang MJ, Wong GW. Loss of CTRP5 improves insulin action and hepatic steatosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 310: E1036–E1052, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00010.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lei X, Seldin MM, Little HC, Choy N, Klonisch T, Wong GW. C1q/TNF-related protein 6 (CTRP6) links obesity to adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. J Biol Chem 292: 14836–14850, 2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.766808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Ye L, Jia G, Chen H, Yu L, Wu D. C1q/TNF-related protein 4 induces signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathway and modulates food intake. Neuroscience 429: 1–9, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little HC, Rodriguez S, Lei X, Tan SY, Stewart AN, Sahagun A, Sarver DC, Wong GW. Myonectin deletion promotes adipose fat storage and reduces liver steatosis. FASEB J 33: 8666–8687, 2019. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900520R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Löfgren P, Hoffstedt J, Rydén M, Thörne A, Holm C, Wahrenberg H, Arner P. Major gender differences in the lipolytic capacity of abdominal subcutaneous fat cells in obesity observed before and after long-term weight reduction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 764–771, 2002. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lönnqvist F, Thörne A, Large V, Arner P. Sex differences in visceral fat lipolysis and metabolic complications of obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 1472–1480, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.17.7.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo Y, Wu X, Ma Z, Tan W, Wang L, Na D, Zhang G, Yin A, Huang H, Xia D, Zhang Y, Shi X, Wang L. Expression of the novel adipokine C1qTNF-related protein 4 (CTRP4) suppresses colitis and colitis-associated colorectal cancer in mice. Cell Mol Immunol 13: 688–699, 2016. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauvais-Jarvis F Sex differences in metabolic homeostasis, diabetes, and obesity. Biol Sex Differ 6: 14, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0033-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayes JS, Watson GH. Direct effects of sex steroid hormones on adipose tissues and obesity. Obes Rev 5: 197–216, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montague CT, Prins JB, Sanders L, Digby JE, O’Rahilly S. Depot- and sex-specific differences in human leptin mRNA expression: implications for the control of regional fat distribution. Diabetes 46: 342–347, 1997. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morselli E, Frank AP, Palmer BF, Rodriguez-Navas C, Criollo A, Clegg DJ. A sexually dimorphic hypothalamic response to chronic high-fat diet consumption. Int J Obes 40: 206–209, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW. Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature 443: 289–295, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nature05026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishikawa S, Yasoshima A, Doi K, Nakayama H, Uetsuka K. Involvement of sex, strain and age factors in high fat diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J and BALB/cA mice. Exp Anim 56: 263–272, 2007. doi: 10.1538/expanim.56.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. The sexual dimorphism of obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 402: 113–119, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedersen SB, Kristensen K, Hermann PA, Katzenellenbogen JA, Richelsen B. Estrogen controls lipolysis by up-regulating alpha2A-adrenergic receptors directly in human adipose tissue through the estrogen receptor alpha. Implications for the female fat distribution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 1869–1878, 2004. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petersen PS, Lei X, Wolf RM, Rodriguez S, Tan SY, Little HC, Schweitzer MA, Magnuson TH, Steele KE, Wong GW. CTRP7 deletion attenuates obesity-linked glucose intolerance, adipose tissue inflammation, and hepatic stress. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 312: E309–E325, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00344.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peterson JM, Aja S, Wei Z, Wong GW. C1q/TNF-related protein-1 (CTRP1) enhances fatty acid oxidation via AMPK activation and ACC inhibition. J Biol Chem 287: 1576–1587, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson JM, Seldin MM, Wei Z, Aja S, Wong GW. CTRP3 attenuates diet-induced hepatic steatosis by regulating triglyceride metabolism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305: G214–G224, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00102.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson JM, Wei Z, Seldin MM, Byerly MS, Aja S, Wong GW. CTRP9 transgenic mice are protected from diet-induced obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R522–R533, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00110.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson JM, Wei Z, Wong GW. C1q/TNF-related protein-3 (CTRP3), a novel adipokine that regulates hepatic glucose output. J Biol Chem 285: 39691–39701, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettersson US, Waldén TB, Carlsson PO, Jansson L, Phillipson M. Female mice are protected against high-fat diet induced metabolic syndrome and increase the regulatory T cell population in adipose tissue. PLoS One 7: e46057, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pilkis SJ, Granner DK. Molecular physiology of the regulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycolysis. Annu Rev Physiol 54: 885–909, 1992. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.54.030192.004321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pullabhatla V, Roberts AL, Lewis MJ, Mauro D, Morris DL, Odhams CA, Tombleson P, Liljedahl U, Vyse S, Simpson MA, Sauer S, de Rinaldis E, Syvänen AC, Vyse TJ. De novo mutations implicate novel genes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Mol Genet 27: 421–429, 2018. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richelsen B Increased alpha 2- but similar beta-adrenergic receptor activities in subcutaneous gluteal adipocytes from females compared with males. Eur J Clin Invest 16: 302–309, 1986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1986.tb01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richelsen B, Pedersen SB, Møller-Pedersen T, Bak JF. Regional differences in triglyceride breakdown in human adipose tissue: effects of catecholamines, insulin, and prostaglandin E2. Metabolism 40: 990–996, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(91)90078-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodriguez S, Lei X, Petersen PS, Tan SY, Little HC, Wong GW. Loss of CTRP1 disrupts glucose and lipid homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 311: E678–E697, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00087.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saad MF, Damani S, Gingerich RL, Riad-Gabriel MG, Khan A, Boyadjian R, Jinagouda SD, el-Tawil K, Rude RK, Kamdar V. Sexual dimorphism in plasma leptin concentration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82: 579–584, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 671–675, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz GJ, Salorio CF, Skoglund C, Moran TH. Gut vagal afferent lesions increase meal size but do not block gastric preload-induced feeding suppression. Am J Physiol 276: R1623–R1629, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.6.R1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seldin MM, Peterson JM, Byerly MS, Wei Z, Wong GW. Myonectin (CTRP15), a novel myokine that links skeletal muscle to systemic lipid homeostasis. J Biol Chem 287: 11968–11980, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skarnes WC, Rosen B, West AP, Koutsourakis M, Bushell W, Iyer V, Mujica AO, Thomas M, Harrow J, Cox T, Jackson D, Severin J, Biggs P, Fu J, Nefedov M, de Jong PJ, Stewart AF, Bradley A. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature 474: 337–342, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith GP The direct and indirect controls of meal size. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 20: 41–46, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00038-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan SY, Lei X, Little HC, Rodriguez S, Sarver DC, Cao X, Wong GW. CTRP12 ablation differentially affects energy expenditure, body weight, and insulin sensitivity in male and female mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 319: E146–E162, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00533.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tewhey R, Kotliar D, Park DS, Liu B, Winnicki S, Reilly SK, Andersen KG, Mikkelsen TS, Lander ES, Schaffner SF, Sabeti PC. Direct identification of hundreds of expression-modulating variants using a multiplexed reporter assay. Cell 172: 1132–1134, 2018. [Erratum in Cell 165: 1519–1529, 2016]. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tom Tang Y, Hu T, Arterburn M, Boyle B, Bright JM, Palencia S, Emtage PC, Funk WD. The complete complement of C1q-domain-containing proteins in Homo sapiens. Genomics 86: 100–111, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Townsend EA, Miller VM, Prakash YS. Sex differences and sex steroids in lung health and disease. Endocr Rev 33: 1–47, 2012. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varlamov O, Bethea CL, Roberts CT Jr. Sex-specific differences in lipid and glucose metabolism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5: 241, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wei Z, Lei X, Petersen PS, Aja S, Wong GW. Targeted deletion of C1q/TNF-related protein 9 increases food intake, decreases insulin sensitivity, and promotes hepatic steatosis in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306: E779–E790, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00593.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei Z, Peterson JM, Wong GW. Metabolic regulation by C1q/TNF-related protein-13 (CTRP13): activation OF AMP-activated protein kinase and suppression of fatty acid-induced JNK signaling. J Biol Chem 286: 15652–15665, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]