Abstract

Successful sperm maturation and storage rely on a unique immunological balance that protects the male reproductive organs from invading pathogens and spermatozoa from a destructive autoimmune response. We previously characterized one subset of mononuclear phagocytes (MPs) in the murine epididymis, CX3CR1+ cells, emphasizing their different functional properties. This population partially overlaps with another subset of understudied heterogeneous MPs, the CD11c+ cells. In the present study, we analyzed the CD11c+ MPs for their immune phenotype, morphology, and antigen capturing and presenting abilities. Epididymides from CD11c-EYFP mice, which express enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) in CD11c+ MPs, were divided into initial segment (IS), caput/corpus, and cauda regions. Flow cytometry analysis showed that CD11c+ MPs with a macrophage phenotype (CD64+ and F4/80+) were the most abundant in the IS, whereas those with a dendritic cell signature [CD64− major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII)+] were more frequent in the cauda. Immunofluorescence revealed morphological and phenotypic differences between CD11c+ MPs in the regions examined. To assess the ability of CD11c+ cells to take up antigens, CD11c-EYFP mice were injected intravenously with ovalbumin. In the IS, MPs expressing macrophage markers were most active in taking up the antigens. A functional antigen-presenting coculture study was performed, whereby CD4+ T cells were activated after ovalbumin presentation by CD11c+ epididymal MPs. The results demonstrated that CD11c+ MPs in all regions were capable of capturing and presenting antigens. Together, this study defines a marked regional variation in epididymal antigen-presenting cells that could help us understand fertility and contraception but also has larger implications in inflammation and disease pathology.

Keywords: dendritic cell, immune cells, macrophage, male reproductive tract

INTRODUCTION

The male reproductive tract, like other human physiological systems, relies on a delicate and carefully regulated interaction between the reproductive organs themselves, the endocrine system, and the immune response. What is unique and fascinating about the male reproductive system, however, is its ability to produce and nurture spermatozoa that appear long after the establishment of self-tolerance and the maturation of the immune system without invoking a damaging immune response (14). The ability of the immune system to discriminate self-antigens from invading antigens relies on inducing tolerance, a principal function of the adaptive immune system. Whereas innate immunity acts in the protection of germ cells from infection or tumors, modulating adaptive immune mechanisms is crucial to a system that needs to minimize immune response against spermatogenic cell antigens in the testicular and posttesticular environments (25).

Posttesticular sperm cells travel through and are stored in the epididymis, a convoluted tubule whose long epithelium functions in a dynamic exchange of fluid, solutes, and protein with the lumen. This exchange is required for the proper maturation of spermatozoa and is in part a result of the close interaction between luminal sperm and specialized proton-secreting “clear cells” through newly described “nanotubules” (3, 8, 53). An infection or immune imbalance within the sensitive epididymal environment is therefore likely to have detrimental effects on fertility. Infertility is a prevalent, disheartening condition for couples and individuals worldwide, and many cases of male infertility are thought to stem from immunological causes (11, 42, 43, 46, 55) or are classified as idiopathic (32, 33). The male reproductive tract has also been recognized as a vulnerable site in which viruses, including HIV, Zika, and Ebola, are able to evade immune activation (38, 64). Additionally, preliminary evidence showed that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is detected in the semen of COVID-19 active and recovering patients (37). The virus targets angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is present in epithelial cells in the cauda, the most distal segment of the epididymis (3), and thus it may persist in this organ. More than half of people with COVID-19 are of reproductive age, and more attention should be paid to the effect of SARS-CoV-2 on the reproductive system, including its effect on semen and sperm quality (48). Because the male tract is connected to the external environment via the urethra, its ability to initiate an effective immune response against invading pathogens is crucial, as is understanding the cellular networks that allow for its specialized, privileged microenvironment.

The epididymis being exempt from autoimmune targeting would not be nearly as intriguing if there was zero immune activity in the reproductive organs; what is fascinating about the posttesticular environment is that there exists an immune tolerance for sperm cells despite the dynamic interaction between the reproductive and immune systems. The barrier between spermatozoa and potentially harmful immune cells is imperfect (36, 47), and a rich network of monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and B and T lymphocytes populates reproductive organs such as the epididymis (2, 6, 11, 16, 24, 25, 39, 49, 50, 62). A subset of these cells, called mononuclear phagocytes, or “MPs,” are located in the epithelium and are thus positioned to play a significant role in male reproductive physiology (2, 11, 12). Included within the MP designation are dendritic cells, whose role is to activate T cells and consequently regulate adaptive immune responses (56, 57), as well as macrophages, which alternatively clear debris and initiate the innate immune response following infection or injury (21, 29, 51). Although these cell types are specialized, their overlapping functional and molecular profiles have made them difficult to distinguish (18, 22).

Studies in reproductive immunology have recently focused on elucidating the specialized roles that these immune cells have in the maturation or protection of spermatozoa (2, 11, 23, 62). We have previously revealed a dense network of MPs in the epididymal epithelium and described the functional and morphological characteristics that make these cells optimal for regulating the balance between effector immune response and tolerance (2, 10, 11). Our latest studies have emphasized region specificity in this exploration: we have aimed to examine the differences between immune cells populating the most proximal or most distal segments of the epididymis, as these regions could play drastically different roles in the maturation, storage, and protection of sperm cells. In our previous publication, we characterized the subset of CX3CR1+ MPs by identifying the functional and transcriptomic signatures of these cells by epididymal region (2). Importantly, we have shown that CX3CR1+ MPs and CD11c+ MPs are both significant populations of immune cells in the epididymis (11, 12) and these two different subsets of epididymal MPs partially overlap (2). Therefore, in the present study we investigated more closely the CD11c+ subset of MPs, with the goal of expanding upon our knowledge of this uniquely tolerant microenvironment. In recent years, transgenic reporter mice in which expression of a fluorescent reporter is driven by the Itgax (CD11c) promoter have been used to identify potential dendritic cell populations in different tissues. It is known that CD11c is highly expressed by conventional dendritic cell subsets; however, it can also be expressed by other cell types including macrophages (29–31). In the present study, using transgenic CD11c-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) mice, we characterized distinct subsets of CD11c+ MPs in different epididymal regions, revealed morphological and functional differences among these cells, and demonstrated that CD11c+ MPs in the epididymis are able to partake in the capture and presentation of antigens and could therefore be key to helping us understand autoimmunity and tolerance in the male reproductive tract.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The transgenic CD11c-EYFP mice (12–15 wk) used in this study were a gift from the laboratory of M. C. Nussenzweig (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY). Adult wild-type (WT) mice (B6CBAF1/J; stock 100011, 12–15 wk) and OT-II transgenic mice [B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J; stock 004194, 5–6 wk] were both purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Subcommittee on Research Animal Care and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Isolation of EYFP+ MPs from CD11c-EYFP mice.

Transgenic CD11c-EYFP mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (2%, mixed with oxygen; flow rate of 2 L/min) followed by cervical dislocation. Epididymides were cleaned of fat and separated into initial segment (IS), caput/corpus, and cauda. The tissues were then submerged in dissociation medium (RPMI 1640; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, catalog no. 22400089) with 0.5 mg/mL collagenase type I and 0.5 mg/mL collagenase type II and cut into small pieces with scissors (2). Enzymatic digestion took place as the samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with gentle shaking and mixing, after which the cells were passed through a 70-μm nylon strainer and washed with a solution of PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM EDTA.

OVA injection.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (2%, mixed with oxygen; flow rate of 2 L/min; Baxter, Deerfield, IL). Intravenous tail vein injection of ovalbumin-Alexa 647 (OVA, 4 mg/kg; Life Technologies Corporation, Eugene, OR) was performed as previously described (3). Mice were euthanized 1 h after injection with isoflurane as above, followed by cervical dislocation after removal of organs for the flow cytometry preparation (3).

Flow cytometry analysis.

After epididymal single-cell suspensions were generated, they were incubated with a cocktail of anti-mouse antibodies including the following: BV711 CD45 (clone 30-F11; catalog no. 563709, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), APC/Cy7 CD11b (M1/711; catalog no. 101226, BioLegend, San Diego, CA), Alexa Fluor 647 CD64 (clone X54-5/7.1; catalog no. 558455, BD Biosciences), PE major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (Clone M5/114.15.2; catalog no. 12-5321-81, Thermo Fisher Scientific), PE/Cy7 F4/80 (clone BM8; catalog no. 123113, BioLegend), PE CD4 (clone RM4-5; catalog no. 100511, BioLegend), BV786 CD103 (clone M290; catalog no. 564322, BD Biosciences), and PE/Cy7 CD69 (clone H1.2F3; catalog no. 104511, BioLegend). Flow cytometry was performed at the HSCI-CRM Flow Cytometry Core (Boston, MA).

For phenotype analysis of immune cells, a negative control, where cells were incubated with no antibodies, and fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls, where cells were incubated with all of the experimental antibodies except one (28), were used to determine gating strategies. For the in vivo OVA injection assay, WT epididymis was used as a control tissue to determine the signal for negative events for EYFP and OVA. Likewise, WT epididymis from an animal injected with OVA was used to determine the signal for negative events for EYFP and positive events for OVA, and epididymis from transgenic CD11c-EYFP mice was used to determine the signal for positive events for EYFP and negative events for OVA. All flow cytometry procedures were performed similarly to those previously described (2).

Cell sorting and coculture.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was used to isolate CD11c+ cells from the IS, caput/corpus, cauda, and spleen of CD11c-EYFP mice, as previously described (2). The FACS was performed at the HSCI-CRM Flow Cytometry Core. AutoMACS cell separating columns (MACS Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany, catalog no. 130-104-454) were used to isolate naive CD4+ T cells from OT-II transgenic mice, as in the previously described protocol (11) and according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

CD11c+ and CD4+ T cells (1-to-5 ratio, respectively) were cocultured in complete medium (RPMI medium 1640; Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. 22400089) with 10% heat-activated fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. 15140122), 50 μM mercaptoethanol, 1% sodium pyruvate (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA, catalog no. S8636-100ML), and 1% nonessential amino acid solution (NEAA; Millipore Sigma, catalog no. M7145-100ML) for 48 h in the presence or absence of OVA peptide (OVA 257-264, 0.2 mg/mL; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). Cells were harvested and stained with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, 2.5 μM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then assessed for proliferation by flow cytometry.

In vitro experiment with OVA-Alexa 647.

CD11c+ MPs were isolated as described in the section Cell sorting and coculture from each epididymal region (IS, caput/corpus, and cauda). The cells were then plated and exposed to Alexa 647-labeled OVA in vitro (0.2 mg/mL). After 1 h of incubation, the cells were assessed for OVA uptake by flow cytometry as described in the section Flow cytometry analysis.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy.

Animals were euthanized with isoflurane (2%, mixed with oxygen; flow rate of 2 L/min) followed by cervical dislocation. Extracted epididymides were fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 4 h at room temperature, as previously described (2). Immunofluorescence (IF) was performed as previously published (2, 53) with the following antibody: PE rat antibody against MHC class II (2 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The antibody was diluted in DAKO medium (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), and slides were mounted with SlowFade Diamond Antifade Mounting Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing DAPI. Epididymis from WT mice was used to identify negative signals for EYFP and MHC class II. Images were captured with a Zeiss LSM800 Airyscan confocal microscope (Oberkochen, Germany).

Negative and positive controls.

For confocal microscopy images, epididymis from WT mice injected with OVA was imaged to determine negative signals for EYFP and positive signals for Alexa 647. Epididymis from CD11c-EYFP transgenic mice was analyzed to determine positive signals for EYFP and negative signals for Alexa 647. For MHC class II staining, we used the primary antibody Rat IgG2b kappa Isotype (PE, 2 μg/mL, clone B149/10H5; catalog 12-4031-82, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as a negative control. No staining was detected.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test and were expressed in scatter plots with bar graphs as means ± SEM. Significance was determined with a value of P < 0.05. GraphPad Prism (version 8; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for the analysis.

RESULTS

Immune phenotype of CD11c+ MPs varies across epididymal segments.

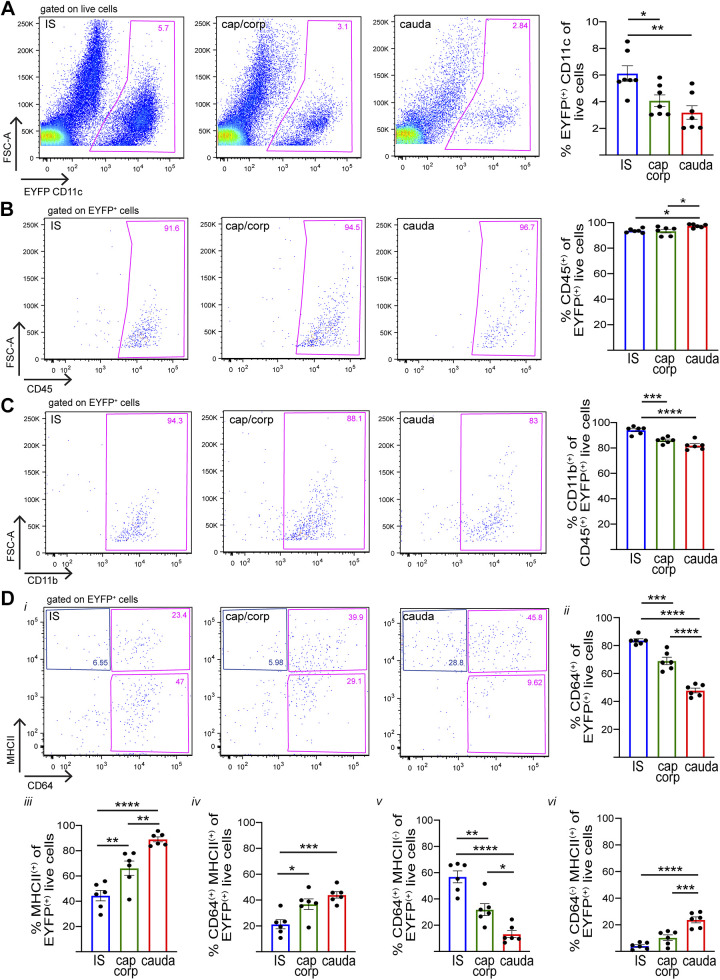

Epididymides from transgenic CD11c-EYFP mice, which specifically express EYFP in CD11c+ cells, were harvested and divided into three regions that included 1) the initial segment (IS); 2) the caput and corpus; and 3) the cauda. This segmentation was performed to reveal phenotypic signatures that may be associated with the unique morphological characteristics of CD11c+ MPs located in the IS, which send intraepithelial projections that reach out between epithelial cells toward the luminal compartment (10–12). Since the caput is structurally and functionally different from the cauda, we studied the MPs from these epididymal regions separately. The caput and corpus MPs were studied together to analyze enough cells by flow cytometry. These segments were then analyzed separately by flow cytometry to study their particular immune phenotypes. We found CD11c+ (EYFP+) cells in all three segments along the epididymis but in different quantities, being most abundant in the IS (Fig. 1A). Nearly all CD11c+ cells were positive for both the hematopoietic cell marker CD45 (Fig. 1B), known to be expressed in all immune cells (26, 60), and the myeloid-lineage marker CD11b (Fig. 1C), usually expressed in monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, and dendritic cells (51, 52, 54). Antibodies against other surface proteins, however, identified populations of MPs associated with different epididymal regions. CD64 is a surface receptor for IgG gamma chain FcγRI, expressed in macrophages (41). In the IS, most CD11c+ cells were found to be CD64+; CD64+ expression decreases for the more distal regions of the epididymis (Fig. 1D, i and ii), in agreement with reports of a greater abundance of macrophages in the caput than in the cauda (2, 62). F4/80 is also a macrophage marker (17, 18); we detected the highest abundance of CD11c+F4/80+ cells in the IS and decreasing for the caput/corpus and cauda (Supplemental Fig. S1A; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12783602.v1).

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometry analysis showing heterogeneous mononuclear phagocyte (MP) populations [CD11c-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)+] from different epididymal segments. A: flow cytometry analysis of CD11c (EYFP+) cells in the initial segment (IS), caput/corpus (cap/corp), and cauda epididymis of CD11c-EYFP+ transgenic mice that specifically express EYFP in MPs. B–D: expression of different immune markers [CD45 (B), CD11b (C), major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) and CD64 (D)] in CD11c (EYFP+) cells in the IS, caput/corpus, and cauda epididymis. In all 3 regions examined, most of the CD11c+ cells are CD45+CD11b+. Di: CD64 and MHCII expression in CD11c (EYFP+) cells in the IS, caput/corpus, and cauda epididymis. ii: % of CD64+ cells within the CD11c+ live cell population (sum of both pink boxes in i). iii: % of MHCII+ cells within the CD11c+ live cell population (sum of top right pink box and blue box in i). iv: % of CD64+MHCII+ cells within the CD11c+ live cell population (top pink box in i). v: % of CD64+MHCII− cells within the CE11c+ live cell population (bottom pink box in i). vi: % of CD64−MHCII+ cells within the CD11c+ live cell population (blue box in i). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test. Each dot represents 1 mouse.

Most CD11c+ cells in the cauda are major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII)+, with decreasing MHCII expression in the more proximal regions of the epididymis (Fig. 1D, i and iii). MHCII is a heterodimer involved in antigen presentation on the surface of immune cells. Although it is present in several different immune cell types, including proinflammatory macrophages (41), it has been previously used in combination with other markers to categorize dendritic cells (10, 13). Further analysis among the CD11c+ cell population revealed that CD64+MHCII+ cells are most concentrated in the distal epididymal regions (Fig. 1D, i and iv), whereas CD64+MHCII− cells are most concentrated in the proximal regions (Fig. 1D, i and v). Finally, cells with the signature CD11c+CD64−MHCII+ were found in the highest percentages in the cauda and in decreasing percentages in the caput/corpus and IS (Fig. 1D, i and vi). CD11c+CD64− is a characteristic signature usually used to define dendritic cells (41), especially in combination with an MHCII+ signature (10, 13). CD103, a marker for dendritic cells (CD64−) exhibiting tolerogenic properties in other organ systems (7, 11), was also expressed significantly more by CD11c+ cells in the caput/corpus and cauda than in the IS (Supplemental Fig. S1B; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12783602.v1). All of these results are summarized in Fig. 2.

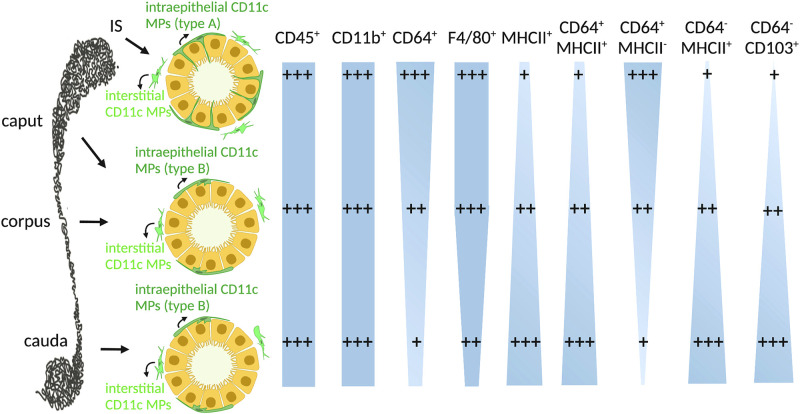

Fig. 2.

Heterogeneous CD11c+ mononuclear phagocyte (MP) populations from different epididymal regions: current model of the immune phenotypes of intraepithelial (dark green) and interstitial (light green) CD11c+ MPs in the initial segment (IS), caput/corpus, and cauda. In IS, intraepithelial CD11c+ MPs exhibit long luminal-reaching projections (type A). In the caput, corpus, and cauda, these cells have few and less developed peritubular projections (type B). Both CD45, an immune cell marker, and CD11b, a myeloid cell marker, are expressed in most of the CD11c+ MPs. CD64 and F4/80, expressed in macrophages, are present in most CD11c+ cells in the IS, and their expression decreases for the more distal regions of the epididymis. In addition, most CD11c+ MPs in the cauda are major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII)+, with decreasing expression in the more proximal regions of the epididymis. Further analysis among the CD11c+ MP population revealed that CD64+MHCII+ cells are most concentrated in the distal regions, whereas CD64+MHCII− cells are most concentrated in the proximal regions. Finally, cells expressing CD11c+CD64−MHCII+, a dendritic cell signature, are present in the highest percentages in the cauda and in decreasing percentages in the caput/corpus and IS. CD103, another marker for dendritic cells (CD64−), is expressed significantly more by CD11c+ cells in the caput/corpus and cauda than in the IS. Note that the width of the light blue shapes represents the abundance of the corresponding cell population.

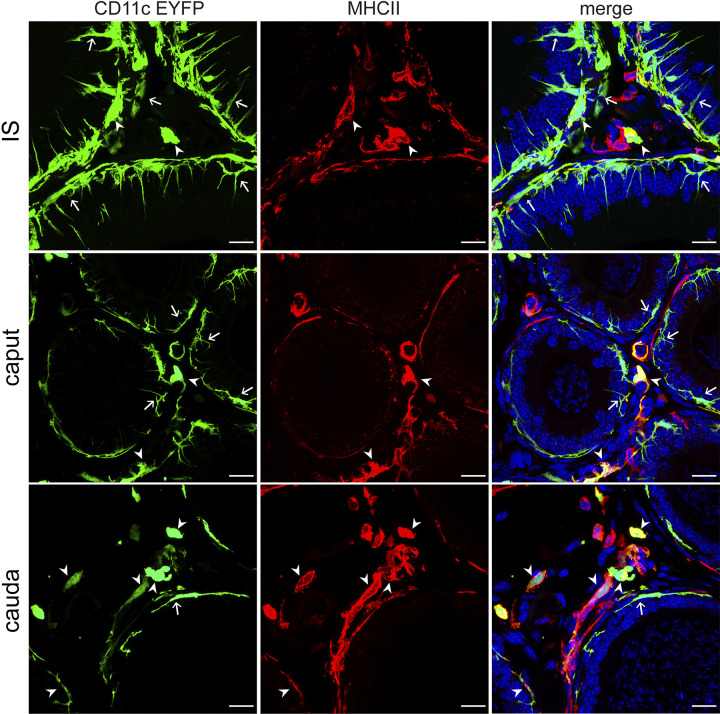

To visualize the localization of these MP populations in the epididymis, we used immunofluorescence (IF) in combination with confocal microscopy to label MHCII+ cells in CD11c-EYFP epididymal tissue, detecting more colocalization of CD11c and MHCII in the cauda than in the IS or the caput (Fig. 3), in agreement with our flow cytometry data (Fig. 1Diii). We also noted differences in the shape of MPs in each region, with CD11c+ MPs in the IS showing long projections through the epithelium toward the lumen, unlike those in the other regions. This finding further suggests that MPs have distinct phenotypes depending on their localization within the epididymis.

Fig. 3.

Localization of mononuclear phagocytes (MPs) that are CD11c and major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) positive: confocal microscopy images showing CD11c+ MPs (green) and MHCII+ cells (red) in IS, caput, and cauda. Double-positive MPs are shown by arrowheads, and CD11c+-only MPs are shown by arrows. The colocalization of CD11c and MHCII occurs more frequently among cells in the cauda (bottom) than in the initial segment (IS) (top) or the caput (middle). Nuclei are labeled with DAPI. Scale bars, 20 µm.

CD11c+ MPs take up and present circulatory antigens in the epididymis.

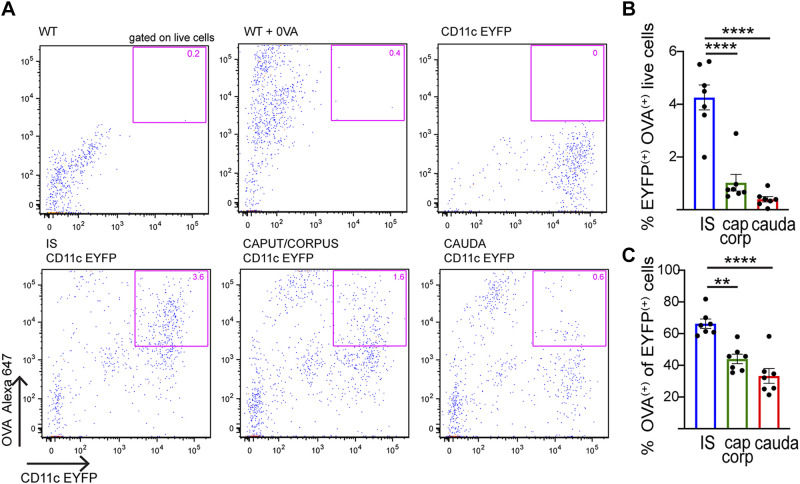

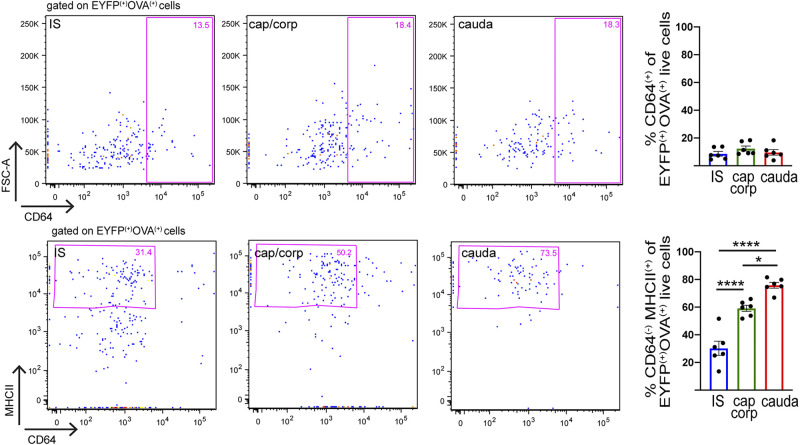

Intravenous (iv) injection of fluorescent ovalbumin (Alexa 647 OVA) was performed to assess the ability of CD11c+ cells from the different epididymal regions to take up circulatory antigens. One hour after injection, the epididymides were harvested and processed for flow cytometry analysis. WT noninjected mice, WT injected mice, and transgenic CD11c-EYFP noninjected mice were used to establish thresholds for positive OVA and EYFP fluorescence (Fig. 4A, top). These studies determined that the internalization of OVA was significantly higher in the IS than in the other regions (Fig. 4A, bottom), both among the total live cells (Fig. 4B) and among CD11c+ cells (Fig. 4C). CD11c+ cells that had internalized OVA were further characterized by their expression of CD64 and MHCII. Among CD11c+OVA+ cells, CD64 was present in all three segments along the epididymis at roughly the same percentage (Fig. 5, top). There was, however, a significant difference in the percentage of cells with the CD64−MHCII+ signature (Fig. 5, bottom). These CD11c+CD64−MHCII+ dendritic cells are more abundant in the cauda than in the other two segments, demonstrating the capture of OVA by dendritic cells in the distal regions of the epididymis. Alternatively, CD11c+OVA+ cells that expressed F4/80, a macrophage marker, were more concentrated in the proximal epididymis (Supplemental Fig. S2; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12786308.v1). Finally, most of the CD11c+ cells that took up OVA were not CD103+ (% CD103+ of CD11c+OVA+ live cells: IS 0.13 ± 0.08%, caput/corpus 5.72 ± 0.43%, cauda 1.82 ± 0.83%; n = 6 in each group), suggesting that OVA is not taken up by tolerogenic cells (7, 11). Taken together, our data demonstrate that CD11c+ MPs display distinct antigen capture activities and immune phenotypes depending on their localization within the epididymis. Moreover, in all regions there was a population of cells that took up OVA but did not express the CD11c marker. The analysis of these OVA+CD11c− cells revealed that most were immune cells (CD45+) and myeloid cells (CD11b+) (Supplemental Fig. S3, A and B; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12786335.v1). This myeloid population also presented the surface markers F4/80 (Supplemental Fig. S3C) and MHCII but did not express CD64 (Supplemental Fig. S3D).

Fig. 4.

Flow cytometry analysis of capture of circulatory antigens by epididymal mononuclear phagocytes (MPs). A: flow cytometry analysis of CD11c+ cells that internalized circulatory antigens [Alexa 647-labeled ovalbumin (OVA)] in initial segment (IS), caput/corpus, and cauda epididymis. Fluorescent OVA was injected via tail vein into wild-type (WT, control) or CD11c-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) mice. Top: gating parameters for CD11c+OVA+ cells were determined with WT mice, WT mice injected with OVA, and CD11c-EYFP mice (pink box). Bottom: subsets of CD11c+ cells that internalized fluorescent OVA in IS, caput/corpus, and cauda epididymis (pink box). B and C: quantification of CD11c+ cells with OVA in IS (blue), caput/corpus (green), and cauda (red). % of CD11c+OVA+ cells with respect to the total number of epididymal live cells analyzed (B) and within the CD11c+ cell population (C). Results are expressed as means ± SEM of experiments performed with samples from 7 mice and were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test. Each dot represents 1 mouse. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Fig. 5.

Characterization of region-specific mononuclear phagocyte (MP) populations that take up ovalbumin (OVA): flow cytometry analysis of CD64 and major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) immune markers in CD11c+ MPs in the initial segment (IS) (blue), caput/corpus (green), and cauda (red) epididymis of CD11c-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) mice injected with OVA. Representative flow cytometry plots for CD64 and MHCII within the CD11c+OVA+ cell population in IS, caput/corpus, and cauda epididymis. Pink boxes, top; % of CD64+ cells within the CD11c+OVA+ live cell population. Pink boxes, bottom: % of MHCII+CD64− cells within the CD11c+OVA+ live cell population. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001.

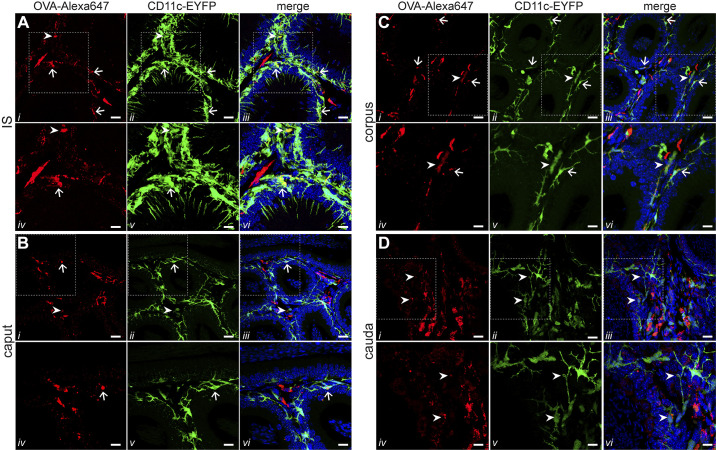

Confocal microscopy imaging detected the highest presence of double-positive CD11c+OVA+ cells in the IS (Fig. 6A), in agreement with our flow cytometry analyses. In this region, CD11c+OVA+ cells were located in the interstitium (Fig. 6A, arrowheads) and in close proximity with the epithelium (Fig. 6A, arrows). Although our previous study noted specifically that OVA had reached the luminal-reaching projections of CX3CR1+ MPs in the IS (2), we did not find that these structures had OVA in CD11c+ MPs (Fig. 6A). In the caput, we saw only a few intraepithelial MPs that internalized OVA inside the epithelia (Fig. 6B, arrows) and in the interstitium (Fig. 6B, arrowheads). Interestingly, the corpus was similar to IS in that the majority of CD11c+ cells that internalized OVA were located in close proximity to the basal side of the epithelium (Fig. 6C, arrows). In addition, there were some double-positive cells in the interstitium (Fig. 6C, arrowheads). In the cauda, we observed only a few double-positive interstitial cells (Fig. 6D, arrows). In all regions, several CD11c− cells that internalized OVA (red) were seen. These cells, which were more abundant in the cauda, were located exclusively in the interstitium and were not in close proximity to the epithelium. Moreover, in all regions, some CD11c+ cells did not take up OVA (green), in agreement with our flow cytometry analysis.

Fig. 6.

Localization of mononuclear phagocytes (MPs) that take up ovalbumin (OVA): confocal microscopy images showing CD11c+ MPs (green) and OVA peptide (red) in initial segment (IS) (A), caput (B), corpus (C), and cauda (D). iv–vi: Higher magnification of a portion of the image shown in i–iii. Arrows show double-positive intraepithelial MPs, and arrowheads show double-positive interstitial MPs. The colocalization of CD11c and OVA occurs more frequently among cells in the IS and corpus than in the caput or the cauda. In IS, we did not observe luminal projections with OVA. In contrast, the cells in the cauda that internalized OVA were located exclusively in the interstitium. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI. Scale bars, 20 μm (main images), 10 μm (magnifications).

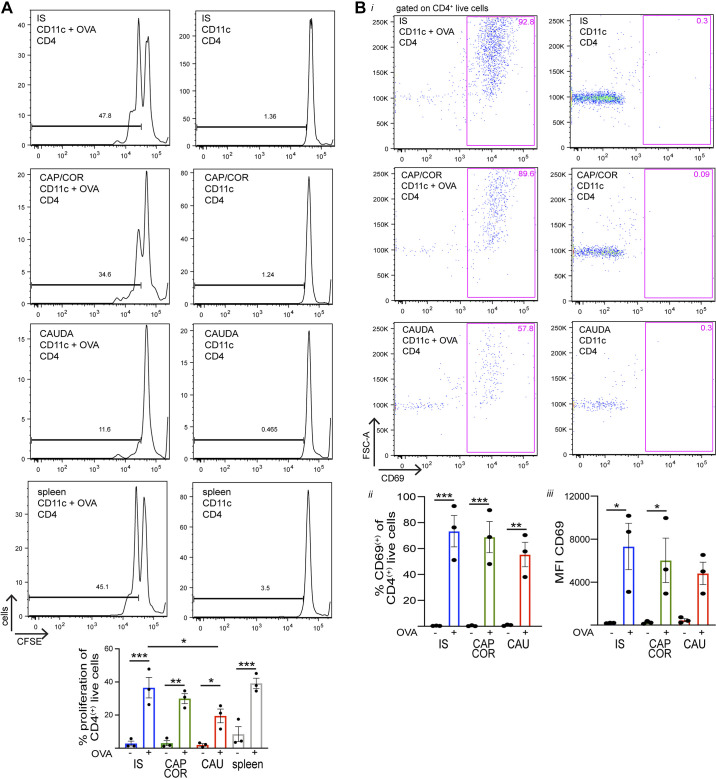

To assess their antigen-presenting properties, CD11c+ cells were isolated from the different epididymal regions and the spleen (positive control) by FACS, using the same gating strategy shown in Fig. 1A. Epididymides were divided again into three regions: IS, caput/corpus, and cauda. The rationale for using three regions (with the caput and corpus combined) is the same as for the flow cytometry experiments. It is important to note that although the IS is smaller in size, it has a higher percentage of CD11c+ cells than the other regions (Fig. 1A). Therefore, large enough numbers of CD11c+ MPs could be analyzed and isolated from the IS alone. CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleen of OT-II mice by magnetic beads and stained with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE), a proliferation marker. CD11c+ cells and CD4+ T cells were cocultured for 48 h in the presence or absence of OVA peptide (OVA257–264). T cells were then assessed by flow cytometry for the dilution of CFSE. CD11c+ MPs that successfully captured and processed OVA were expected to present the OVA257–264 at the cell surface, which would then be recognized by OT-II CD4+ T cells, inducing the activation and proliferation of these cells, as detected by CFSE dilution. This process would generate a new population of cells with a lower fluorescence intensity and present as multiple peaks in the histogram. Importantly, most CD11c+ MPs across all regions were capable of taking up OVA after 1 h of incubation during in vitro experiments (% OVA+ of CD11c+ live cells: IS 79.2 ± 2.5%, caput/corpus 68.4 ± 9.8%, cauda 88.9 ± 1.6%; n = 2, with each sample comprised of 6 epididymides from 3 mice); however, cells from the different segments had varying presenting abilities. The analysis revealed that CD11c+ cells from the IS and caput/corpus have the greatest presenting ability, followed by the cauda (Fig. 7A). As a positive control, spleen CD4+ T cells showed cell division indicated by two peaks after coculture with spleen CD11c+ cells in the presence of OVA (Fig. 7A, bottom left). After the coculture, CD69 expression was analyzed for CD4+ live T cells from each condition by flow cytometry to determine the effect of T-cell activation by antigen presentation. The analysis revealed CD69 upregulation in all epididymal regions following treatment with OVA (Fig. 7B, i and ii), confirming activation of T cells after antigen presentation by CD11c+ cells. Moreover, in the presence of OVA we detected a trend toward a higher mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD69 within the CD4+ live cell population in the IS and caput/corpus than in the cauda (Fig. 7Biii), suggesting more activation of these cells in the proximal and middle regions. Figure 8 illustrates a summary of the immune phenotype of CD11c+ MPs that had internalized OVA and their antigen presentation activity in the different regions examined.

Fig. 7.

In vitro antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells by epididymal and splenic mononuclear phagocytes (MPs). A: CD11c+ cells were isolated from initial segment (IS), caput/corpus (CAP/COR), cauda, and spleen by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using CD11c-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) mice, and CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleen of OT-II mice isolated by magnetic beads and stained with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE). CD11c+ and CFSE-labeled T cells were cocultured for 2 days in the presence (left) or absence (right) of ovalbumin (OVA)257–264 peptide. Bottom: proliferation of CD4+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry in the presence (+) or absence (-) of OVA257–264 peptide. B: after the coculture, CD4+ live cells were assessed for CD69 expression. i: Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+ live cells in the IS (top), caput/corpus (middle), and cauda (bottom) from cultures in the presence (left) or absence (right) of OVA257–264 peptide. ii: % of CD69+ cells within the CD4+ live cell population (pink boxes) in the presence (+) or absence (-) of OVA257–264 peptide. iii: Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD69+ within the CD4+ live cell population (pink boxes) in the presence (+) or absence (-) of OVA257–264 peptide. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Data are shown as means ± SEM and were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test. Each dot represents 1 experiment, and each experiment represents cells from a pool of 2 mice.

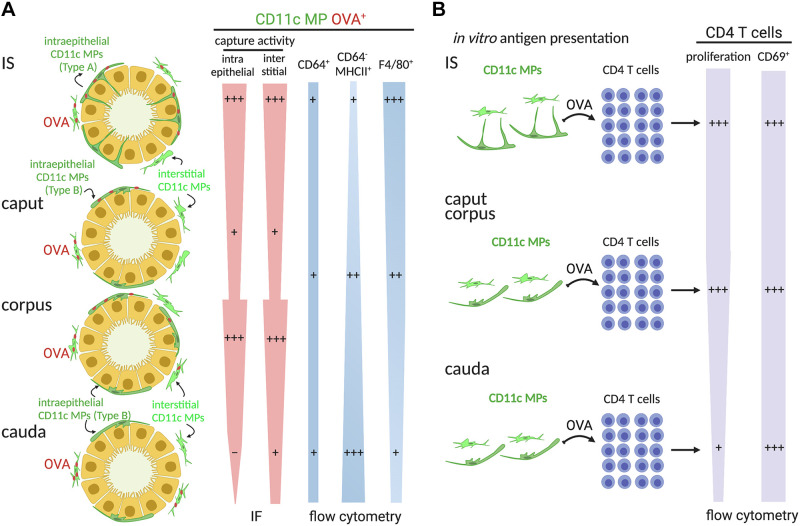

Fig. 8.

Distinct immune phenotypes and antigen capture activity of CD11c+ mononuclear phagocytes (MPs) depending on their localization within the epididymis. A: current model of the immune phenotypes of intraepithelial (dark green) and interstitial (light green) CD11c+ MPs that take antigen [ovalbumin (OVA)] in the initial segment (IS), caput, corpus, and cauda. In IS, intraepithelial CD11c+ MPs exhibit long luminal-reaching projections (type A). In the caput, corpus, and cauda, these cells have few and less developed peritubular projections (type B). The internalization of OVA is higher in the IS and corpus than in the caput and cauda by immunofluorescence (IF). By flow cytometry, among CD11c+OVA+ cells, CD64 was present, at a lower proportion, in all 3 segments along the epididymis; CD64− major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII)+ dendritic cells are more abundant in the cauda than in the other regions. Alternatively, CD11c+OVA+ cells that expressed F4/80, a macrophage marker, are more concentrated in the IS. Note that the width of the shapes represents the abundance of the corresponding cell population. B: in vitro antigen presentation assay: CD11c+ cells isolated from IS, caput/corpus, cauda and CD4+ T cells were cocultured in the presence of OVA. CD11c+ MPs that successfully captured and processed OVA were expected to present the OVA at the cell surface, which would then be recognized by CD4+ T cells, inducing the activation and proliferation of these cells. CD11c+ cells from the IS and caput/corpus generate more CD4+ T cell proliferation, suggesting greatest presenting ability, than those isolated from the cauda. Moreover, CD69, an activation marker, is expressed in CD4+ T cells after coculture with CD11c+ MPs from all epididymal regions after treatment with OVA.

DISCUSSION

The successful maturation and storage of viable male gametes within the male reproductive tract rely on the establishment of a protective luminal environment in the epididymis. Among the different physiological steps required for this to occur is a unique and fascinating immunological balance that protects the reproductive organs from invading pathogens while protecting spermatozoa from a destructive autoimmune response. Although male infertility is common, and a significant portion of these problems are thought to be rooted in immunological causes (11, 42, 43, 46, 55), the role of immune and autoimmune responses in the posttesticular environment is still not well understood. To elucidate the interaction between the immune and reproductive systems, we previously described an extensive network of a heterogeneous subset of MPs that populate the epididymis, characterized by CX3CR1 expression, and showed that their localization within the epididymis correlated to microenvironment-specific phenotypic and functional characteristics (2, 10–12). In that study, we determined that the CX3CR1+ population partially overlaps with the CD11c+ population (4), another subset of MPs that is not well defined. Consequently, in the present study we further characterized CD11c+ MPs, which populate specific regions within the epididymis, and aimed to categorize them into cells with a dendritic cell or macrophage phenotype. We found that CD11c+ cells represent a heterogeneous population exhibiting features that strongly depend on their location in the epididymis.

The male reproductive tract is contiguous with the external environment, and it is therefore susceptible to infection by pathogens that can indirectly cause transient or permanent infertility via their retrograde ascent through the urethra (3, 9, 11, 44). Understanding the specialized role of distinct MP subsets in the epididymis could illuminate the unique immunological balance within the posttesticular reproductive environment. Until recent developments in flow cytometry methodologies, it has been challenging to distinguish and characterize monocyte, dendritic cell, and macrophage subsets within the MP network (22, 62). So far, there have been relatively few studies dedicated to the relationship between the immune and reproductive systems. In this study, we revealed distinct MP populations within each examined epididymal region, as well as identifying trends when comparing the proximal versus distal regions. We characterized dendritic cells with the signature CD11c+CD64−MHCII+ and macrophages with both the CD64+ signature (41, 59) and the F4/80+ signature (17, 18). Notably, the coexpression of F4/80 and CD11c has also been found in MPs from other tissues. Although some authors define these populations as dendritic cells, others categorize them as macrophages. The phenotypical and functional characteristics of these cell types significantly overlap in other organs (17). Our results revealed that most CD11c+ cells in the IS are CD64+ and F4/80+ macrophages, whereas these percentages decrease in the more distal regions of the epididymis. These findings are in agreement with a study showing an abundance of macrophages in the caput compared with the cauda (62) and with our previous study that found a similar trend in CX3CR1+ cells (2). In contrast, cells with the dendritic cell signature CD11c+CD64−MHCII+ were found in the highest percentages in the cauda and in decreasing percentages in the caput/corpus and IS. The colocalization of CD11c and MHCII was most evident among cells in the cauda, which was consistent with the flow cytometry analysis. These results, which indicate a higher concentration of dendritic cells in the distal epididymis, when taken together with our previous study (2) confirm that the population of CD11c+ cells follows the same trends as the population of CX3CR1+ cells. This study also utilizes a more specific marker, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, which is required for antigen presentation to T cells (44). The localization of dendritic cells in the cauda, which is the site of sperm storage, may indicate that they are specialized to monitor and protect sperm cells from the immune system before ejaculation. Alternatively, since bacteria are most likely to be introduced to the cauda epididymis, these cells could also be important components in the immune response against invading pathogens threatening the reproductive system.

We have previously shown that MPs within the epididymis are distinguishable not only by surface markers but also by their morphology when visualized with microscopic methods (2, 11). IF images showed greater diversity in physical shape among MPs in the IS, where CD11c+ cells exhibit long luminal-reaching projections through the epithelium. These observations are consistent with our previous studies describing similar morphologies in both CX3CR1+ cells and CD11c+ cells (2, 11, 12). It has been suggested that macrophages in the proximal epididymis may function to maintain the mucosa in a resting state, rather than to initiate an immune response (11), similar to what was previously suggested for MPs in other systems (18). Using transcriptomic profile analysis of CX3CR1+ cells, we have shown that although MPs in all regions express genes related to phagocytic activity and antigen processing, there are significant differences in the specific transcripts expressed depending on localization within the epididymis (2). The unique structure and function of CD11c+ MPs (this study) and CX3CR1+ MPs (2) in the proximal epididymis, and in the IS especially, may be characteristics crucial to establishing an immune privileged environment in which sperm are protected from both pathogens as well as autoimmune responses as they enter and start to mature within the epididymis. These cells may accomplish this by participating in luminal sampling (35), with their projections positioned strategically to capture antigens passing through the lumen.

Establishment of peripheral tolerance requires antigen uptake, processing, and presentation. As was similarly shown in other systems (4) and for CX3CR1+ MPs in the epididymis (2), CD11c+ cells in this study were able to rapidly take up circulatory antigens (OVA). Most CD11c+ MPs across all epididymal regions were capable of taking up OVA in vitro; however, in our in vivo experiment involving intravenous injection, we found that a higher percentage of CD11c+ MPs in the IS had captured OVA than in the more distal epididymal regions. We had observed this same trend in our previous study of CX3CR1+ MPs, and we believe that these results are logical and consistent given the enriched vascularization and prevalence of fenestrated blood vessels within the IS (1, 23, 40, 58). However, we noted that, unlike in CX3CR1+ MPs, OVA did not reach the luminal-reaching projections of CD11c+ MPs, suggesting differences in the uptake activity between these subsets of MPs. Interestingly, IF showed similar numbers of CD11c+ MPs that captured antigens in the corpus and IS, a discrepancy with the flow cytometry analysis. Importantly, this difference could be due to the fact that caput and corpus segments were studied together to analyze a sufficiently high number of cells by flow cytometry. These results highlight the importance of using complementary methodologies to analyze the complexity of the epididymal immune system. Moreover, in the cauda region, only cells located in the interstitium were positive for OVA, indicating that they provide an efficient protective barrier by taking up antigens in the bloodstream, thus preventing them from reaching the epithelial lining. Importantly, blood capillaries are also abundant in the cauda (27). In addition, most interstitial cells that had captured OVA were not CD11c+ (this study) or CX3CR1+ (2) in the cauda. We previously showed that the majority of these cells are F4/80+ by immunofluorescence (2). Altogether, these observations indicate that the epithelial lining of the proximal epididymis is more likely to be affected by blood-borne pathogens, compared with the more distal epididymal regions.

In this study, CD11c+CD64+ cells that had taken up OVA were present in small quantities in all segments. CD11c+F4/80+OVA+ cells were most concentrated in the proximal epididymis. We found that CD11c+CD64−MHCII+ dendritic cells that internalized OVA, however, exist in a significantly higher percentage in the cauda than in the other two segments. These results demonstrate the ability of dendritic cells in the distal regions of the epididymis to successfully capture circulatory antigens. These cells present characteristics similar to conventional dendritic cells—highly phagocytic cells that express high levels of MHCII and are endowed with potent antigen-presenting cell function (51). We have, however, identified some CX3CR1+ cells that took up antigens and also expressed CD103, a dendritic cell marker (2, 13). In the present study, a significant percentage of CD11c+ cells in the caput/corpus and cauda also expressed CD103, although this marker is not expressed in CD11c+ cells that had taken up OVA. We further characterized the CD11c− cells that took up OVA. Flow cytometry analysis showed that these cells are myeloid cells expressing F4/80 and MHCII markers but lacking CD64. A similar population of cells located in the gut, which express the signature CD11clowMHCII+CD11b+, was previously defined as “CD11clow serosal macrophages” (17). These findings provide more evidence of the heterogeneity of MPs in the epididymis.

Postprocessing antigen presentation is the final, crucial step in adaptive immunity, while the presentation of self-antigens is essential for self-tolerance. Our functional antigen-presenting in vitro study revealed that CD11c+ cells from the IS and the caput/corpus have the greatest presenting ability and that this function decreases in the more distal regions of the epididymis. Altogether, our results confirm that CD11c+ MPs in the epididymis are capable of capturing, processing, and presenting antigens, important features of immune activation. This is particularly interesting because we observed a greater quantity of dendritic cells in the cauda by flow cytometry, strongly suggesting that MPs may function in a different capacity in the different epididymal regions. The capabilities demonstrated here by cells in the IS allow them to be active in the capture and processing of luminal antigens, where they could potentially perform luminal sampling, as described in other tissues (35), to control the luminal microenvironment and maintain immune tolerance for the maturing sperm. The luminal-reaching projections of MPs in the IS described earlier, and in this study, would be positioned appropriately for this very function (2). Our results also revealed that CD69 is significantly upregulated after T-cell activation following OVA uptake by CD11c+ MPs, similar to what we would expect from conventional dendritic cells (51). These results are consistent with the role of CD69 as an early activation marker, known for the recruitment and differentiation of T cells in other organ systems (5, 34). CD69 is also upregulated after the activation of regulatory T cells (5, 34), which are found in the testis and epididymis and are necessary for the suppression of inflammatory diseases in the male reproductive tract, such as orchitis and epididymitis (49, 61).

In summary, our study identified and categorized distinct subsets of CD11c+ MPs in different epididymal regions, revealed morphological differences in these cells, and demonstrated the ability of epididymal MPs to partake in the capture and presentation of antigens, tasks crucial to adaptive immunity. Our recent publication characterized the subset of CX3CR1+ MPs by identifying the functional and transcriptomic signatures of these MPs by epididymal region (2). Our present results complement this earlier publication by demonstrating that the same trends can be observed by studying MPs with the marker CD11c and strengthen our characterization of dendritic cells and macrophages in the epididymis by using additional markers, such as MHCII. Furthermore, this study expands upon our prior understanding of the MPs’ immune capabilities by investigating and confirming their ability to present captured antigens in the epididymis. In other organ systems that also rely on a delicate balance between immune activation and self-tolerance, such as within the intestine, disruption of this balance can contribute to the development of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders (45). The incidence of such disorders in the epididymis is detrimental to reproductive health and may contribute to male infertility cases (15). To better understand and protect this immunological balance, more experiments are needed to characterize the mucosal network, elucidate if and how MPs in the epididymis partake in luminal sampling, and continue studying the role that cell-cell communication has in establishing this environment. Another unresolved question is how epididymis-resident MPs are originated and maintained. Epididymal CD11c+ MPs may be derived from embryonic precursors and then maintained locally and/or may be differentiated from circulating monocytes, similar to what is known in other tissues (19, 20, 22).

A more comprehensive understanding of the immune regulation within the different epididymal regions would provide invaluable knowledge toward the prevention of disorders such as epididymitis or male infertility, as well as toward the identification of targets for immunocontraception. Additional studies will be required to determine whether CD11c+ MPs change their expression of surface markers at different physiopathological states. Also interesting is that, because of its unique immunosuppressive capacity, the male reproductive tract has been recognized as a vulnerable site in which viruses are able to escape immunosurveillance and remain transmissible (38, 64). The epididymis also has a natural resistance to tumorigenicity and is rarely affected by cancer (63), and although the basis of its exception is unknown, understanding these mechanisms could offer insights into the prevention or treatment of cancer more broadly. These studies of the highly specialized epididymal environment demonstrate that a greater knowledge of the interaction between the immune and male reproductive systems could have implications in medicine well beyond fertility and contraception.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Lalor Foundation Fellowship (to M. A. Battistone) and NIH Grants DK-121848 (to D. Brown), HD-040793 (to S. Breton), and HD-069623 (to S. Breton). The Microscopy Core facility of the MGH Program in Membrane Biology receives support from Boston Area Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center Grant DK-57521 and Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Grant DK-43351. The Zeiss LSM800 microscope was acquired with NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10-OD-021577-01.

DISCLOSURES

S. Breton is a cofounder of Kantum Pharma (previously Kantum Diagnostics, Inc.), a company developing a diagnostic and therapeutic combination to prevent and treat acute kidney injury. S. Breton and her spouse own equity in the privately held company. S. Breton and D. Brown are inventors on a patent (US Patent 10,088,489) covering technology that has been licensed to the company through the MGH but is unrelated to the present study. S. Breton’s and D. Brown’s interests were reviewed and are managed by MGH and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.B. and M.A.B. conceived and designed research; A.C.M. and M.A.B. performed experiments; L.M.S., R.G.S., and M.A.B. analyzed data; D.B., S.B., and M.A.B. interpreted results of experiments; A.C.M. and M.A.B. prepared figures; A.C.M., S.B., and M.A.B. drafted manuscript; A.C.M., L.M.S., R.G.S., D.B., F.J.Q., S.B., and M.A.B. edited and revised manuscript; A.C.M., L.M.S., R.G.S., D.B., F.J.Q., S.B., and M.A.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the HSCI-CRM Flow Cytometry Facility [Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston, MA], in particular Maris Handley and Gloria Lima, for guidance and assistance in sorting and flow cytometry analysis. We also thank the laboratory of M. C. Nussenzweig (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY) for gifting us the transgenic CD11c-EYFP mice used in this study.

Present address of A. C. Mendelsohn: Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe K, Takano H, Ito T. Microvasculature of the mouse epididymis, with special reference to fenestrated capillaries localized in the initial segment. Anat Rec 209: 209–218, 1984. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092090208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battistone MA, Mendelsohn AC, Spallanzani RG, Brown D, Nair AV, Breton S. Region-specific transcriptomic and functional signatures of mononuclear phagocytes in the epididymis. Mol Hum Reprod 26: 14–29, 2020. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaz059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battistone MA, Spallanzani RG, Mendelsohn AC, Capen D, Nair AV, Brown D, Breton S. Novel role of proton-secreting epithelial cells in sperm maturation and mucosal immunity. J Cell Sci 133: jcs233239, 2019. doi: 10.1242/jcs.233239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang SY, Song JH, Guleng B, Cotoner CA, Arihiro S, Zhao Y, Chiang HS, O’Keeffe M, Liao G, Karp CL, Kweon MN, Sharpe AH, Bhan A, Terhorst C, Reinecker HC. Circulatory antigen processing by mucosal dendritic cells controls CD8+ T cell activation. Immunity 38: 153–165, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cibrián D, Sánchez-Madrid F. CD69: from activation marker to metabolic gatekeeper. Eur J Immunol 47: 946–953, 2017. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Com E, Bourgeon F, Evrard B, Ganz T, Colleu D, Jégou B, Pineau C. Expression of antimicrobial defensins in the male reproductive tract of rats, mice, and humans. Biol Reprod 68: 95–104, 2003. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med 204: 1757–1764, 2007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornwall GA. New insights into epididymal biology and function. Hum Reprod Update 15: 213–227, 2009. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham KA, Beagley KW. Male genital tract chlamydial infection: implications for pathology and infertility. Biol Reprod 79: 180–189, 2008. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.067835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Da Silva N, Barton CR. Macrophages and dendritic cells in the post-testicular environment. Cell Tissue Res 363: 97–104, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2270-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Da Silva N, Cortez-Retamozo V, Reinecker HC, Wildgruber M, Hill E, Brown D, Swirski FK, Pittet MJ, Breton S. A dense network of dendritic cells populates the murine epididymis. Reproduction 141: 653–663, 2011. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Da Silva N, Smith TB. Exploring the role of mononuclear phagocytes in the epididymis. Asian J Androl 17: 591–596, 2015. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.153540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenbarth SC. Dendritic cell subsets in T cell programming: location dictates function. Nat Rev Immunol 19: 89–103, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0088-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fijak M, Meinhardt A. The testis in immune privilege. Immunol Rev 213: 66–81, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fijak M, Pilatz A, Hedger MP, Nicolas N, Bhushan S, Michel V, Tung KS, Schuppe HC, Meinhardt A. Infectious, inflammatory and ‘autoimmune’ male factor infertility: how do rodent models inform clinical practice? Hum Reprod Update 24: 416–441, 2018. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flickinger CJ, Bush LA, Howards SS, Herr JC. Distribution of leukocytes in the epithelium and interstitium of four regions of the Lewis rat epididymis. Anat Rec 248: 380–390, 1997. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S, Helft J, Chow A, Elpek KG, Gordonov S, Mazloom AR, Ma’ayan A, Chua WJ, Hansen TH, Turley SJ, Merad M, Randolph GJ; Immunological Genome Consortium . Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat Immunol 13: 1118–1128, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geissmann F, Gordon S, Hume DA, Mowat AM, Randolph GJ. Unravelling mononuclear phagocyte heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol 10: 453–460, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nri2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gentek R, Molawi K, Sieweke MH. Tissue macrophage identity and self-renewal. Immunol Rev 262: 56–73, 2014. doi: 10.1111/imr.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity 44: 439–449, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 953–964, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guilliams M, Ginhoux F, Jakubzick C, Naik SH, Onai N, Schraml BU, Segura E, Tussiwand R, Yona S. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages: a unified nomenclature based on ontogeny. Nat Rev Immunol 14: 571–578, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nri3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guiton R, Voisin A, Henry-Berger J, Saez F, Drevet JR. Of vessels and cells: the spatial organization of the epididymal immune system. Andrology 7: 712–718, 2019. doi: 10.1111/andr.12637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall SH, Hamil KG, French FS. Host defense proteins of the male reproductive tract. J Androl 23: 585–597, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedger MP. Immunophysiology and pathology of inflammation in the testis and epididymis. J Androl 32: 625–640, 2011. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.111.012989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hermiston ML, Xu Z, Weiss A. CD45: a critical regulator of signaling thresholds in immune cells. Annu Rev Immunol 21: 107–137, 2003. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirai S, Naito M, Terayama H, Ning Q, Miura M, Shirakami G, Itoh M. Difference in abundance of blood and lymphatic capillaries in the murine epididymis. Med Mol Morphol 43: 37–42, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00795-009-0473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hulspas R, O’Gorman MR, Wood BL, Gratama JW, Sutherland DR. Considerations for the control of background fluorescence in clinical flow cytometry. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 76: 355–364, 2009. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hume DA. Differentiation and heterogeneity in the mononuclear phagocyte system. Mucosal Immunol 1: 432–441, 2008. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hume DA. Macrophages as APC and the dendritic cell myth. J Immunol 181: 5829–5835, 2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Immig K, Gericke M, Menzel F, Merz F, Krueger M, Schiefenhövel F, Lösche A, Jäger K, Hanisch UK, Biber K, Bechmann I. CD11c-positive cells from brain, spleen, lung, and liver exhibit site-specific immune phenotypes and plastically adapt to new environments. Glia 63: 611–625, 2015. doi: 10.1002/glia.22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jose-Miller AB, Boyden JW, Frey KA. Infertility. Am Fam Physician 75: 849–856, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jungwirth A, Giwercman A, Tournaye H, Diemer T, Kopa Z, Dohle G, Krausz C; European Association of Urology Working Group on Male Infertility . European Association of Urology guidelines on Male Infertility: the 2012 update. Eur Urol 62: 324–332, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura MY, Hayashizaki K, Tokoyoda K, Takamura S, Motohashi S, Nakayama T. Crucial role for CD69 in allergic inflammatory responses: CD69-Myl9 system in the pathogenesis of airway inflammation. Immunol Rev 278: 87–100, 2017. doi: 10.1111/imr.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee M, Lee Y, Song J, Lee J, Chang SY. Tissue-specific role of CX3CR1 expressing immune cells and their relationships with human disease. Immune Netw 18: e5, 2018. doi: 10.4110/in.2018.18.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy S, Robaire B. Segment-specific changes with age in the expression of junctional proteins and the permeability of the blood-epididymis barrier in rats. Biol Reprod 60: 1392–1401, 1999. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.6.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li D, Jin M, Bao P, Zhao W, Zhang S. Clinical characteristics and results of semen tests among men with coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 3: e208292, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu W, Han R, Wu H, Han D. Viral threat to male fertility. Andrologia 50: e13140, 2018. doi: 10.1111/and.13140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malm J, Nordahl EA, Bjartell A, Sørensen OE, Frohm B, Dentener MA, Egesten A. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein is produced in the epididymis and associated with spermatozoa and prostasomes. J Reprod Immunol 66: 33–43, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markey CM, Meyer GT. A quantitative description of the epididymis and its microvasculature: an age-related study in the rat. J Anat 180: 255–262, 1992. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGovern N, Schlitzer A, Janela B, Ginhoux F. Protocols for the identification and isolation of antigen-presenting cells in human and mouse tissues. Methods Mol Biol 1423: 169–180, 2016. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3606-9_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLachlan RI. Basis, diagnosis and treatment of immunological infertility in men. J Reprod Immunol 57: 35–45, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0378(02)00014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meinhardt A, Hedger MP. Immunological, paracrine and endocrine aspects of testicular immune privilege. Mol Cell Endocrinol 335: 60–68, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michel V, Pilatz A, Hedger MP, Meinhardt A. Epididymitis: revelations at the convergence of clinical and basic sciences. Asian J Androl 17: 756–763, 2015. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.155770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niess JH, Reinecker HC. Dendritic cells: the commanders-in-chief of mucosal immune defenses. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 22: 354–360, 2006. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000231807.03149.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pattinson HA, Mortimer D. Prevalence of sperm surface antibodies in the male partners of infertile couples as determined by immunobead screening. Fertil Steril 48: 466–469, 1987. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)59420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pelletier RM. Blood barriers of the epididymis and vas deferens act asynchronously with the blood barrier of the testis in the mink (Mustela vison). Microsc Res Tech 27: 333–349, 1994. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070270408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perry MJ, Arrington S, Neumann LM, Carrell D, Mores CN. It is currently unknown whether SARS-CoV-2 is viable in semen or whether COVID-19 damages spermatozoa. Andrology andr.12831, 2020. doi: 10.1111/andr.12831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pierucci-Alves F, Midura-Kiela MT, Fleming SD, Schultz BD, Kiela PR. Transforming growth factor beta signaling in dendritic cells is required for immunotolerance to sperm in the epididymis. Front Immunol 9: 1882, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pöllänen P, Cooper TG. Immunology of the testicular excurrent ducts. J Reprod Immunol 26: 167–216, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quintana FJ, Yeste A, Mascanfroni ID. Role and therapeutic value of dendritic cells in central nervous system autoimmunity. Cell Death Differ 22: 215–224, 2015. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanchez-Madrid F, Nagy JA, Robbins E, Simon P, Springer TA. A human leukocyte differentiation antigen family with distinct alpha-subunits and a common beta-subunit: the lymphocyte function-associated antigen (LFA-1), the C3bi complement receptor (OKM1/Mac-1), and the p150,95 molecule. J Exp Med 158: 1785–1803, 1983. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shum WW, Da Silva N, Brown D, Breton S. Regulation of luminal acidification in the male reproductive tract via cell-cell crosstalk. J Exp Biol 212: 1753–1761, 2009. doi: 10.1242/jeb.027284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solovjov DA, Pluskota E, Plow EF. Distinct roles for the alpha and beta subunits in the functions of integrin alphaMbeta2. J Biol Chem 280: 1336–1345, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stedronska J, Hendry WF. The value of the mixed antiglobulin reaction (MAR test) as an addition to routine seminal analysis in the evaluation of the subfertile couple. Am J Reprod Immunol 3: 89–91, 1983. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1983.tb00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J Exp Med 137: 1142–1162, 1973. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.5.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steinman RM, Inaba K. Myeloid dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol 66: 205–208, 1999. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki F. Microvasculature of the mouse testis and excurrent duct system. Am J Anat 163: 309–325, 1982. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001630404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamoutounour S, Henri S, Lelouard H, de Bovis B, de Haar C, van der Woude CJ, Woltman AM, Reyal Y, Bonnet D, Sichien D, Bain CC, Mowat AM, Reis e Sousa C, Poulin LF, Malissen B, Guilliams M. CD64 distinguishes macrophages from dendritic cells in the gut and reveals the Th1-inducing role of mesenteric lymph node macrophages during colitis. Eur J Immunol 42: 3150–3166, 2012. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas ML. The leukocyte common antigen family. Annu Rev Immunol 7: 339–369, 1989. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tung KS, Harakal J, Qiao H, Rival C, Li JC, Paul AG, Wheeler K, Pramoonjago P, Grafer CM, Sun W, Sampson RD, Wong EW, Reddi PP, Deshmukh US, Hardy DM, Tang H, Cheng CY, Goldberg E. Egress of sperm autoantigen from seminiferous tubules maintains systemic tolerance. J Clin Invest 127: 1046–1060, 2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI89927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voisin A, Whitfield M, Damon-Soubeyrand C, Goubely C, Henry-Berger J, Saez F, Kocer A, Drevet JR, Guiton R. Comprehensive overview of murine epididymal mononuclear phagocytes and lymphocytes: unexpected populations arise. J Reprod Immunol 126: 11–17, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeung CH, Wang K, Cooper TG. Why are epididymal tumours so rare? Asian J Androl 14: 465–475, 2012. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeng X, Blancett CD, Koistinen KA, Schellhase CW, Bearss JJ, Radoshitzky SR, Honnold SP, Chance TB, Warren TK, Froude JW, Cashman KA, Dye JM, Bavari S, Palacios G, Kuhn JH, Sun MG. Identification and pathological characterization of persistent asymptomatic Ebola virus infection in rhesus monkeys. Nat Microbiol 2: 17113, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]