Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been shown to prolong cardiac action potential duration resulting in afterdepolarizations, the cellular basis of triggered arrhythmias. As previously shown, protein kinase A type I (PKA I) is readily activated by oxidation of its regulatory subunits. However, the relevance of this mechanism of activation for cardiac pathophysiology is still elusive. In this study, we investigated the effects of oxidation-activated PKA I on cardiac electrophysiology. Ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated from redox-dead PKA-RI Cys17Ser knock-in (KI) and wild-type (WT) mice and exposed to H2O2 (200 µmol/L) or vehicle (Veh) solution. In WT myocytes, exposure to H2O2 significantly increased oxidation of the regulatory subunit I (RI) and thus its dimerization (threefold increase in PKA RI dimer). Whole cell current clamp and voltage clamp were used to measure cardiac action potentials (APs), transient outward potassium current (Ito) and inward rectifying potassium current (IK1), respectively. In WT myocytes, H2O2 exposure significantly prolonged AP duration due to significantly decreased Ito and IK1 resulting in frequent early afterdepolarizations (EADs). Preincubation with the PKA-specific inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (10 µmol/L) completely abolished the H2O2-dependent decrease in Ito and IK1 in WT myocytes. Intriguingly, H2O2 exposure did not prolong AP duration, nor did it decrease Ito, and only slightly enhanced EAD frequency in KI myocytes. Treatment of WT and KI cardiomyocytes with the late INa inhibitor TTX (1 µmol/L) completely abolished EAD formation. Our results suggest that redox-activated PKA may be important for H2O2-dependent arrhythmias and could be important for the development of specific antiarrhythmic drugs.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Oxidation-activated PKA type I inhibits transient outward potassium current (Ito) and inward rectifying potassium current (IK1) and contributes to ROS-induced APD prolongation as well as generation of early afterdepolarizations in murine ventricular cardiomyocytes.

Keywords: arrhythmia, early afterdepolarization, oxidative stress, potassium currents, protein kinase A

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrhythmias are a major contributor to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. At the cellular level, triggered activity, which is a main driver of ventricular tachycardia (VT) (46, 47), results from early and delayed afterdepolarizations (EADs and DADs) (64). In heart failure (HF), it was shown that triggered activity may be a consequence of reduced repolarization reserve with significant prolongation of action potential duration partly due to reduced transient outward potassium current (Ito) and inward rectifying potassium current (IK1) (34). The mechanisms are incompletely understood but may involve reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent signaling (58, 59). Increased levels of ROS are frequently found in animal models (6, 10, 24) and human HF (4, 28, 36, 37) and have been shown to result in inhibition of IK1 (9, 32, 33, 56, 57) and Ito (11, 38, 45). ROS-dependent signaling may not only involve direct posttranslational modification (i.e., oxidation) of ion channels and transporters (12, 15) but may also be mediated by oxidative activation of second messengers (14, 59, 60).

Interestingly, recent evidence delineated a novel mechanism of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) activation by oxidation of cysteine 17 and 38 at the regulatory RIα subunit. This results in intermolecular disulfide bond formation (between cysteine 17 and 38) of two adjacent RI subunits consistent with dimerization (5), which disinhibits the catalytic subunits leading to increased PKA-dependent phosphorylation. This oxidative PKA activation has been shown to be important for angiogenesis (5) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-dependent signaling (13). However, its relevance for cardiac (patho-)physiology has not been characterized. Since PKA has been shown to regulate Ito and IK1, we tested the hypothesis that redox-dependent activation of PKA I may be important for arrhythmogenesis by inhibition of repolarizing potassium currents under conditions of increased oxidative stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study approval.

Experiments with murine cardiomyocytes conformed to Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament, to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed., 2011), and to local institutional guidelines.

Generation of Cys17Ser PKA RI mice.

Mice that constitutively express PKA RI Cys17Ser (knock-in or KI) were generated as previously described (5). The point mutation Cys17Ser, which renders PKA type I redox-dead, was introduced into exon 1 of the Prkar1a gene by site-directed mutagenesis. These mice behave normally under physiological conditions.

Isolation of murine cardiomyocytes.

Homozygous PKA RI Cys17Ser (KI) and wild-type (WT) littermates (male, aged 10–18 wk, BL/6J background, housed according to German animal laws, kindly provided by Prof. Philip Eaton) were anesthetized with isoflurane. After death by cervical dislocation, hearts were quickly excised, mounted on a Langendorff perfusion apparatus, and retrogradely perfused with nominally Ca-free solution containing (in mmol/L) 113 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 0.6 KH2PO4, 0.6 Na2HPO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 12 NaHCO3, 10 KHCO3, 10 HEPES, 30 taurine, 10 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM), 5.5 glucose, and 0.032 phenol red for 4 min at 37°C (pH 7.4). Then, 7.5 mg/mL liberase (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), trypsin 0.6%, and 0.125 mmol/L CaCl2 were added to the perfusion solution. Perfusion was continued for 3–4 min until the heart became flaccid. Ventricular tissue was collected in perfusion buffer supplemented with 5% bovine calf serum, cut into small pieces, and dispersed by repeatedly pipetting until no solid cardiac tissue was left. Ca reintroduction was performed by stepwise increasing [Ca] from 0.1 to 0.8 mmol/L (43).

Patch-clamp experiments.

A ruptured-patch whole cell voltage clamp was used to measure Ito and IK1. For these experiments, microelectrodes (2–3 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing (in mmol/L) 40 K-aspartate, 90 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 5 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Li-GTP, 0.1 niflumic acid, and 10 HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.2 using KOH. Bath solution contained (in mmol/L) 135 tetramethylammonium chloride as the substitute for Na, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, and 0.3 CdCl2 to block calcium channels (pH 7.4 with KOH). After patch rupture, the access resistance was typically <7 MΩ. Currents were elicited using a voltage step protocol (−130 mV to +90 mV, steps of 10 mV, holding potential of −90 mV, and duration of 300 ms for each step). Following each recording, cells were superfused with bath solution containing BaCl2 (200 µmol/L) to block IK1. The resulting trace was then digitally subtracted from the original trace to determine the Ba-sensitive current, which is hence referred to as IK1. Ito was defined as the difference between the peak outward current and the steady-state current. Time constants of Ito inactivation (τslow and τfast) were calculated from a triple exponential fit

where f(t) is the current at time t, n = 3, A is the respective current amplitude, τ is the time constant of inactivation, and C is the steady-state current.

For action potential measurements, the pipette solution contained (in mmol/L) 122 K-aspartic acid, 10 NaCl, 8 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Li-GTP, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2 with KOH). The bath solution contained (in mmol/L) 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 1 CaCl2, and 5 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH). APs were elicited using square current pulses of 1 nA and a duration of 1–4 ms at a frequency of 1 Hz. Cells with access resistance >15 MΩ, spontaneous activity under basal conditions, and need for injection of negative currents with amplitudes more negative than −40 pA were excluded from analysis to prevent factors like bad cell access, inclusion of damaged cells, and cells with increased leak currents to bias our results. Only cells with excellent membrane potential stability and adequate overshoot upon each electrical stimulus were included in the analysis.

To inhibit PKA and Ca/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), cells were preincubated in bath solutions containing Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (10 µM; Biolog, Bremen, Germany) and myristoylated autocamtide-2-related inhibitory peptide (AIP, 1 µM; AnaSpec, Fremont, California) for 10 min, respectively. For inhibition of late INa, tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 µM, Bristol, UK) was added to the superfusate. Oxidative stress was induced by preincubation with H2O2-containing bath solution (200 µM) for at least 4 min for current measurements or by continuous superfusion for AP recordings in a light-protected environment. The time points of patch-clamp registrations were selected based on our previous experience. We have previously shown that Ca spark frequency or late Na current was increased as early as 4 min after onset of H2O2 exposure in a CaMKII-dependent fashion (60). Moreover, EADs and DADs also occurred as early as 4–8 min after onset of H2O2 exposure (60). All experiments were conducted at room temperature (22°C–24°C).

Western blot analysis.

Murine cardiomyocytes were isolated as described earlier (Isolation of murine cardiomyocytes). Cells were then harvested and lysed in Tris buffer containing (in mmol/L) 20 Tris·HCl, 200 NaCl, 20 NaF, 1 Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 1 DTT (pH 7.4) and a complete protease inhibitor cocktail and a PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (both Roche Diagnostics) by trituration. Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Biotechnology). Denatured cell lysates (30 min, 37°C in 2% β-mercaptoethanol) were subjected to Western blot analysis (8% SDS polyacrylamide gels) using primary antibodies against Kir2.1 (polyclonal rabbit, 1:1,000, Alomone Laboratories) and GAPDH (monoclonal mouse, 1:20,000, BIOTREND). Primary antibodies were incubated at 4°C overnight. Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000, Amersham Biosciences) for GAPDH and HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000, Amersham Biosciences) for Kir2.1 (incubation for 1 h at room temperature). Incubation with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) for 5 min at room temperature enabled detection of the protein bands, which were developed onto Super XR-N X-ray films (Fujifilm) and scanned using ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad). ImageJ was used to analyze mean densitometric values.

PKA RI dimerization assay.

PKA RI dimerization was assessed from isolated cardiomyocytes treated with H2O2 (100 µmol/L) for 10 min by Western blot analysis following protein separation by SDS-PAGE, with addition of maleimide (100 mmol/L) to the lysis buffer to prevent disulfide exchange by thiol alkylation. Immunoblots were probed with primary antibodies to PKARI (monoclonal mouse, 1:500, BD Transduction Laboratories). Secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000, Amersham Biosciences). PKA oxidation status was determined by the ratio of its dimeric (oxidized) (120 kD) RI subunit to GAPDH.

Data analysis and statistics.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed using one-way or two-way ANOVA with post hoc test (Holm–Sidak) or Student’s t test for unpaired data and mixed-effects analysis with post hoc test (Holm–Sidak or Tukey) for paired data as appropriate. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Dimerization of PKA regulatory subunit I by oxidative stress.

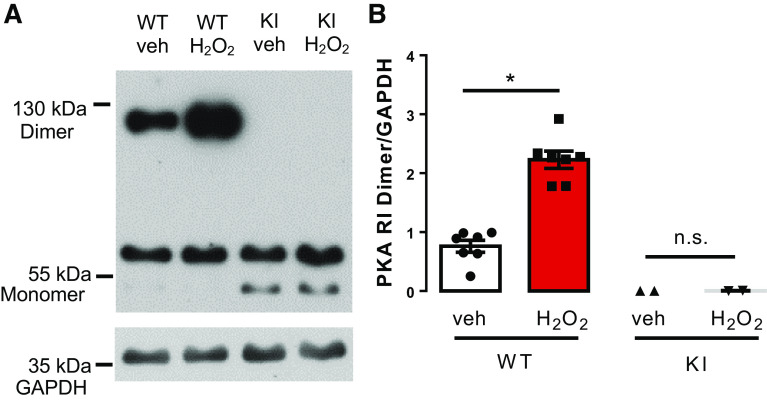

To test if exposure of isolated murine ventricular cardiomyocytes to H2O2 (100 µmol/L) results in oxidation of PKA RI subunits, we applied a PKA RI dimerization assay using Western blot analysis under nonreducing conditions. In WT, the PKA RI dimer and monomer were almost equally abundant in vehicle-treated cells. However, H2O2 exposure resulted in a significant increase in PKA RI dimer at the expense of RI monomer consistent with RI oxidation and disulfide bridge formation. The dimer/GAPDH ratio increased by approximately threefold from 0.7611 ± 0.1012 to 2.228 ± 0.1464 (N = 7 vs. 7 mice, P < 0.0001, Fig. 1, A and B). Importantly, in KI cardiomyocytes, formation of relevant amounts of RI dimers could not be observed under basal conditions or after addition of H2O2 (0.0017 ± 0.0012 vs. 0.0047 ± 0.0019, N = 2 vs. 2 mice, P = 0.99) (Fig. 1, A and B).

Fig. 1.

PKA RI dimerization assay in murine hearts. A: original Western blot for the assessment of dimerization of the PKA regulatory subunit RI upon exposure to H2O2 (100 µmol/L). B: analysis of mean densitometric values reveals a threefold increase in PKA RI dimer/GAPDH ratio in WT myocytes exposed to H2O2 (n= 5 vs. 5; *P = 0.0003 vs. control, unpaired two-tailed t test; values are means ± SE). In contrast, KI myocytes were devoid of any H2O2-dependent RI dimerization (n = 2 vs. 2). PKA, protein kinase; RI, regulatory subunit; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; WT, wild-type; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

H2O2 prolongs action potential duration by oxidative PKA activation.

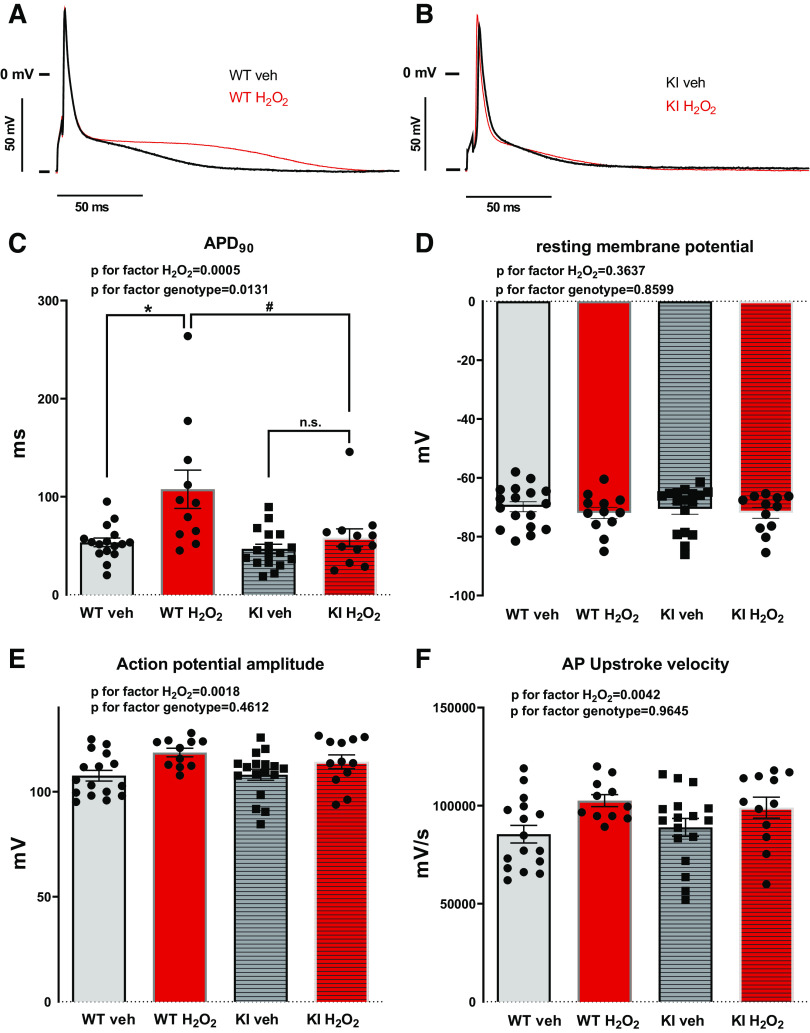

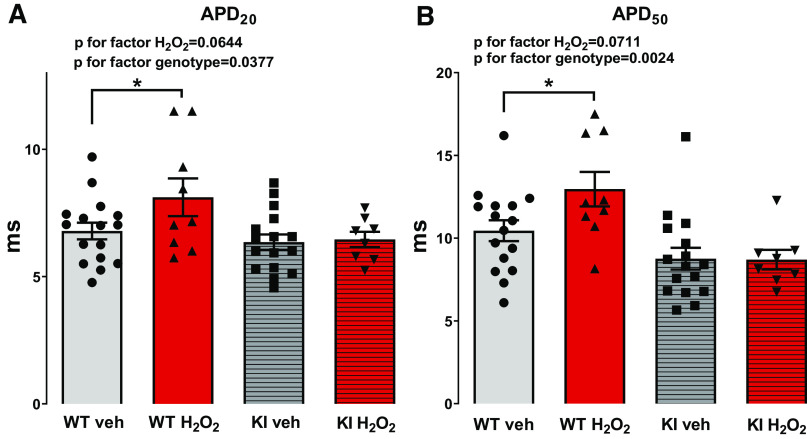

Action potentials (APs) were measured by whole cell voltage clamp. H2O2 exposure resulted in a marked increase in AP duration in WT cardiomyocytes. Compared with the baseline, 2 min after onset of H2O2 exposure, the AP duration at 90% repolarization (APD90) increased from 53.42 ± 4.44 ms to 107.6 ± 19.59 ms [N (n) = 9 (16) vs. 8 (11); P = 0.0006, Fig. 2, A and C]. In contrast, H2O2 did not increase APD90 in myocytes lacking oxidative PKA activation. In KI myocytes, APD90 was 46.81 ± 4.71 versus 58.13 ± 9.07 ms [N (n) = 6 (17) vs. 5 (12); P = 0.6686; Fig. 2, A and C], suggesting that redox-activated PKA may be important for regulation of the repolarization reserve. Importantly, in WT myocytes, APD20 significantly increased from 6.79 ± 0.33 ms to 8.12 ± 0.74 ms [WT Veh vs. WT H2O2, N (n) = 9 (16) vs. 8 (9), Holm–Sidak’s post hoc test for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2 P = 0.0407] and APD50 significantly increased from 10.45 ± 0.63 ms to 12.96 ± 1.04 ms [WT Veh vs. WT H2O2, N (n) = 9 (16) vs. 8 (9), Holm–Sidak’s post hoc test for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2 P = 0.0380] at 8 min of H2O2 superfusion, where significant differences in EAD frequency are observed (Fig. 3, A and B). Contrary to this, H2O2 had no effect on these parameters in KI myocytes [APD20: 6.36 ± 0.30 vs. 6.46 ± 0.30, KI Veh vs. KI H2O2, N (n) = 6 (16) vs. 5 (8), Holm–Sidak’s post hoc test for KI Veh vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.7764; APD50: 8.76 ± 0.65 vs. 8.70 ± 0.59, N (n) = 6 (16) vs. 5 (8), Holm–Sidak’s post hoc test for KI Veh vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.8586] (Fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 2.

Effects of H2O2 on cardiac action potentials in WT and KI cardiomyocytes. A and B: superimposed original traces of APs in WT (A) and KI (B) cardiomyocytes under control conditions (Veh) and upon exposure to H2O2 (200 µmol/L). C: action potential duration at 90% of repolarization (APD90) is significantly prolonged upon exposure to H2O2 for 2 min in WT cardiomyocytes compared with control conditions and to H2O2-treated KI cardiomyocytes (ANOVA P for factor H2O2 = 0.0005, ANOVA P for factor genotype = 0.0131, Tukey’s post hoc test for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2 P = 0.0006 (*), WT H2O2 vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.0108 (#), and for KI Veh vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.6686). D: resting membrane potential remains unaltered upon H2O2 treatment (ANOVA P for factor H2O2 = 0.3637, ANOVA P for factor genotype = 0.8599, Tukey’s post hoc test for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2 P = 0.8586 and for KI Veh vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.9575). E: action potential amplitude (APA) is increased in WT and KI cardiomyocytes upon oxidative stress (ANOVA P for factor H2O2 = 0.0018, ANOVA P for factor genotype = 0.4612, Tukey’s post hoc test for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2 P = 0.0124 and for KI Veh vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.3639). F: H2O2 treatment results in an increase in AP upstroke velocity in both WT and KI cardiomyocytes (ANOVA P for factor H2O2 = 0.0042, ANOVA P for factor genotype = 0.9645, Tukey’s post hoc test for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2 P = 0.0316 and for KI Veh vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.4063). All values are means ± SE. The numbers of mice/cells were: WT (Veh), 9/16; WT (H2O2), 8/11; KI (Veh), 6/17; and KI (H2O2), 5/12. Mixed-effects analysis with Tukey’s post hoc correction. WT, wild-type; KI, knock-in; Veh, vehicle; AP, action potential.

Fig. 3.

Effects of H2O2 on APD20 and APD50 in WT and KI cardiomyocytes. In contrast to KI cardiomyocytes, APD20 (A) as well as APD50 (B) are significantly increased in WT cardiomyocytes upon exposure to H2O2 (200 µmol/L) for 8 min (APD20: ANOVA P for factor H2O2 = 0.0644, ANOVA P for factor genotype = 0.0377, Holm–Sidak’s post hoc test for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2 P = 0.0407 (*) and for KI Veh vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.7764; APD50: ANOVA P for factor H2O2 = 0.0711, ANOVA P for factor genotype = 0.0024, Holm–Sidak’s post hoc test for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2 P = 0.0380 (*) and for KI Veh vs. KI H2O2 P = 0.8586. Values are means ± SE. The numbers of mice/cells were: WT (Veh), 9/16; WT (H2O2), 8/9; KI (Veh), 6/16; and KI (H2O2), 5/8. APD, action potential duration; WT, wild-type; KI, knock-in; Veh, vehicle.

Interestingly, H2O2 treatment significantly increased the action potential amplitude (APA) and also the upstroke velocity (Vmax) in both WT and KI myocytes (ANOVA P for factor H2O2 0.0018 and 0.0042, respectively), with no difference between the genotypes (ANOVA P for factor genotype 0.4612 and 0.9645, respectively). This suggests that redox activation of PKA may not be required for H2O2-dependent stimulation of depolarizing ion currents like voltage-gated Na current. In WT in the presence of H2O2, APA increased from 107.6 ± 2.52 mV to 118.6 ± 2.03 mV [WT Veh vs. WT H2O2, N (n) = 9 (16) vs. 8 (11); Tukey’s post hoc test P = 0.0124, Fig. 2E] and Vmax increased from 85.469 ± 4.503 V/s to 102.564 ± 3.073 V/s [for WT Veh vs. WT H2O2, N (n) = 9 (16) vs. 8 (11); Tukey’s post hoc test P = 0.0316, Fig. 2F]. For KI Veh versus KI H2O2, APA was 108.1 ± 2.65 mV versus 114.2 ± 3.28 mV [N (n) = 6 (17) vs. 5 (12); Tukey’s post hoc test P = 0.364 and P = 0.561 for KI H2O2 vs. WT Veh] and Vmax was 88.947 ± 4.568 V/s versus 98.983 ± 5.340 V/s [N (n) = 6 (17) vs. 5 (12); Tukey’s post hoc test P = 0.406 and P = 0.323 for KI H2O2 vs. WT Veh, Fig. 2, E and F].

In contrast to AP duration, there were no differences in the resting membrane potential after exposure to H2O2 both in WT and KI myocytes [ANOVA P for factor H2O2 = 0.3637; ANOVA P for factor genotype = 0.8599, WT Veh vs. WT H2O2: −69.84 ± 1.71 mV vs. −71.93 ± 1.92 mV, N (n) = 9 (17) vs. 8 (12), Tukey’s post hoc test P = 0.8586; KI Veh vs. KI H2O2: −70.54 ± 1.84 mV vs. −71.88 ± 1.87 mV, N (n) = 6 (17) vs. 5 (12), Tukey’s post hoc test P = 0.9575] (Fig. 2, A and D).

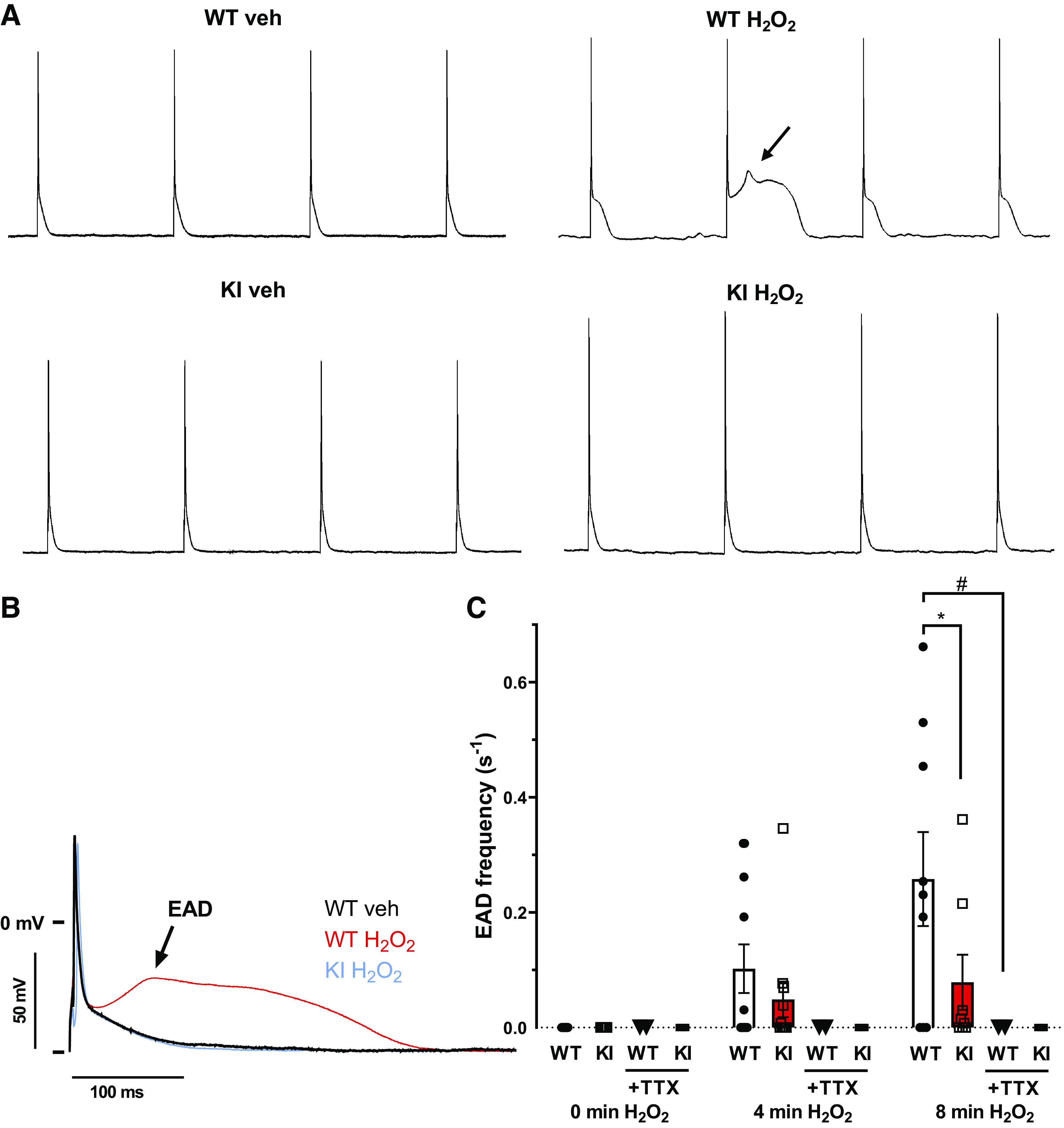

H2O2 enhanced early afterdepolarizations by oxidative activation of PKA.

Early afterdepolarizations (EADs) were measured using a provocation protocol that was initiated at different time points after the start of H2O2 superfusion. In detail, the protocol consisted of three trains of 30 consecutive stimuli at a frequency of 1 Hz, with a 10-s rest interval in between trains 1 and 2, and a 30-s rest interval in between trains 2 and 3. EADs were defined as a positive voltage deflection of ≥5 mV following the initial repolarization (phase 1 of the action potential) of a stimulated AP (Fig. 4,A and B).

Fig. 4.

Early afterdepolarizations in WT and KI cardiomyocytes upon exposure to H2O2. A: original traces of action potentials elicited at a frequency of 1 Hz before and 8 min after onset of H2O2 (200 µmol/L) superfusion. In contrast to KI cardiomyocytes, H2O2 exposure induces frequent early afterdepolarizations (indicated by arrows) in WT myocytes. B: superimposed original traces of action potentials with and without early afterdepolarizations (EAD). C: summary data for EAD frequency. The time points refer to the time at the end of the respective acquisition train interval (90 s). APs were analyzed under basal conditions (0 min = from −130s to 0 s), 4 min after start of H2O2 superfusion (= from 120 s to 250 s) and again 8 min after start of H2O2 superfusion (= 360 s to 490 s). For calculation of EAD frequency, for each interval, the number of EADs was normalized to the interval duration. At 8 min after onset of H2O2 exposure, WT cardiomyocytes exhibited a significantly increased EAD frequency compared with redox-dead KI cardiomyocytes (*P = 0.0035, mixed-effects analysis with Tukey’s post hoc correction). Interestingly, treatment of WT as well as KI myocytes with TTX completely abolished EAD formation even after 8 min of H2O2 treatment (WT + H2O2 vs. WT + H2O2 + TTX, #P = 0.0126; KI + H2O2 vs. KI + H2O2 + TTX, P = 0.7045; mixed-effects analysis with Tukey’s post hoc correction). At the time points 0, 4, and 8 min, respectively, the number of mice/cells were: 8/16, 8/11, and 8/9, respectively, for WT; 2/2, 2/2, and 2/2, respectively, for WT + TTX; 5/16, 5/11, and 5/8, respectively, for KI; and 2/4, 2/4, and 2/3, respectively, for KI + TTX. The reduced number of cells at later time points is a function of H2O2-dependent cell death. Values are means ± SE. WT, wild-type; KI, knock-in; AP, action potential; TTX, tetrodotoxin.

Consistent with increased AP duration, H2O2 exposure resulted in significantly more EADs in WT compared with in KI myocytes. At 8 min after onset of H2O2 exposure, EAD frequencies were 0.258 ± 0.082/s in WT and 0.079 ± 0.048/s in KI myocytes [N (n) = 8 (9) vs. 5 (8); P = 0.0035] (Fig. 4,A and C). There were no significant differences between EAD take-off potentials or EAD delay between WT and KI cardiomyocytes, neither at 4 min nor at 8 min of treatment with H2O2 (Supplemental Fig. S2, A and B; all Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.5283/epub.41754). Importantly, when WT or KI myocytes were additionally treated with TTX to inhibit late INa, no EADs could be observed [WT: 0.258 ± 0.082/s vs. 0.0 ± 0.0/s; H2O2 vs. H2O2 + TTX N (n) = 8 (9) vs. 2 (2), P = 0.013; KI: 0.078 ± 0.048/s vs. 0.0 ± 0.0/s; N (n) = 5 (8) vs. 2 (3), H2O2 vs. H2O2 + TTX, P = 0.705] (Fig. 4C).

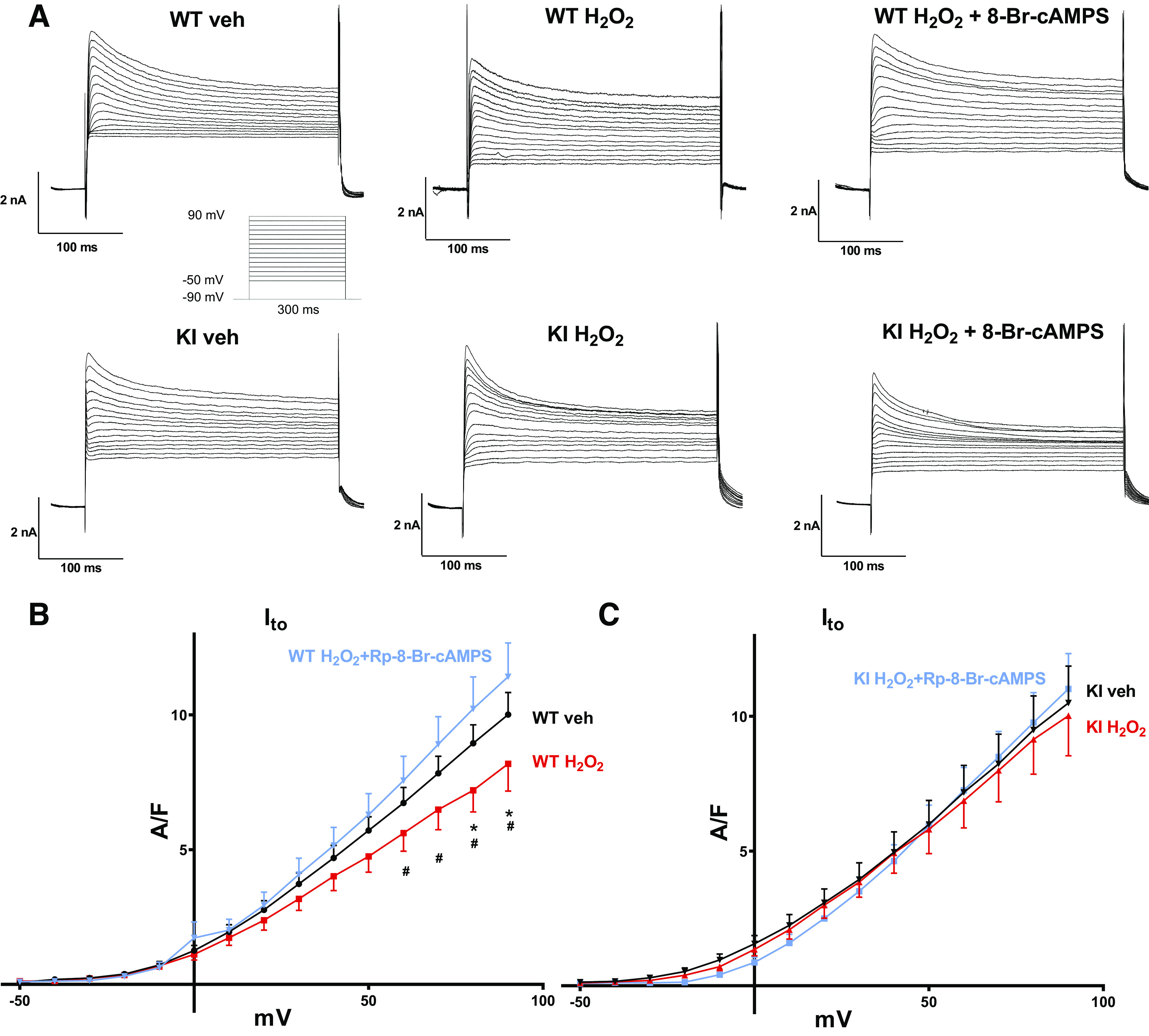

H2O2-dependent inhibition of Ito is mediated by oxidative activation of PKA.

Transient outward current (Ito), a major contributor to early repolarization of the action potential (phase 1), was measured by application of a voltage step protocol from −50 mV to +90 mV (10-mV steps) in ruptured whole cell voltage-clamp configuration. In WT cardiomyocytes, H2O2 treatment resulted in a significant decrease in Ito density from 10.01 ± 0.82 A/F to 8.19 ± 1.01 A/F [N (n) = 8 (16) vs. 8 (11); P = 0.02, Fig. 5, A and B]. Importantly, this decrease could be completely abolished by preincubation with the PKA-specific inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (10 µM), suggesting that PKA-dependent regulation of Ito may be involved. In the presence of H2O2 and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, Ito density was 11.42 ± 1.26 A/F [N (n) = 9 (12) vs. 8 (11); P < 0.0001 vs. WT + H2O2, Fig. 5, A and B].

Fig. 5.

Effect of H2O2 on transient outward potassium current (Ito) in WT and KI cardiomyocytes. A: original traces of outward currents in ventricular cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and redox-dead KI mice under basal conditions and after exposure to H2O2 (6–12 min) with or without pretreatment with the PKA-selective inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS. The inset shows the applied voltage protocol. B and C: I–V curves of Ito in WT (B) and KI (C) cardiomyocytes. B: in WT cardiomyocytes, H2O2 causes a marked decrease in Ito density, which could be completely abolished by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (*P < 0.05 vs. Veh, #P < 0.05 vs. H2O2 + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). Numbers of mice/cells were: 8/16 (Veh), 8/11 (H2O2), and 9/12 (H2O2 + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). C: in contrast, H2O2 did not affect Ito in KI cardiomyocytes. Numbers of mice/cells were: 7/12 (Veh), 5/10 (H2O2), and 6/13 (H2O2 + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). Values are means ± SE. Two-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s post hoc correction. WT, wild-type; KI, knock-in; PKA, protein kinase A.

In contrast to WT, induction of ROS generation by H2O2 did not affect Ito density in myocytes lacking redox-dependent activation of PKA. In KI myocytes, Ito density was 10.50 ± 1.37 A/F (vehicle) versus 10.68 ± 1.58 A/F [H2O2; N (n) = 7 (12) vs. 5 (10); P = 0.91, Fig. 5, A and C].

In accordance, preincubation of the KI myocytes with Rp-8-Br-cAMPS did not alter Ito current density under oxidative stress [KI H2O2 + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS vs. KI H2O2: 11.02 ± 1.31 A/F vs. 10.68 ± 1.58 A/F, N (n) = 5 (10) vs. 5 (10), P = 0.78; KI vehicle vs. KI H2O2 + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS 10.50 ± 1.37 vs. 11.02 ± 1.31 A/F, N (n) = 7 (12) vs. 5 (10); P = 0.91] (Fig. 5, A and C).

It is worth noting that time constants of Ito inactivation (τslow and τfast) were not influenced by H2O2, neither in wild-type nor in knock-in myocytes (data not shown).

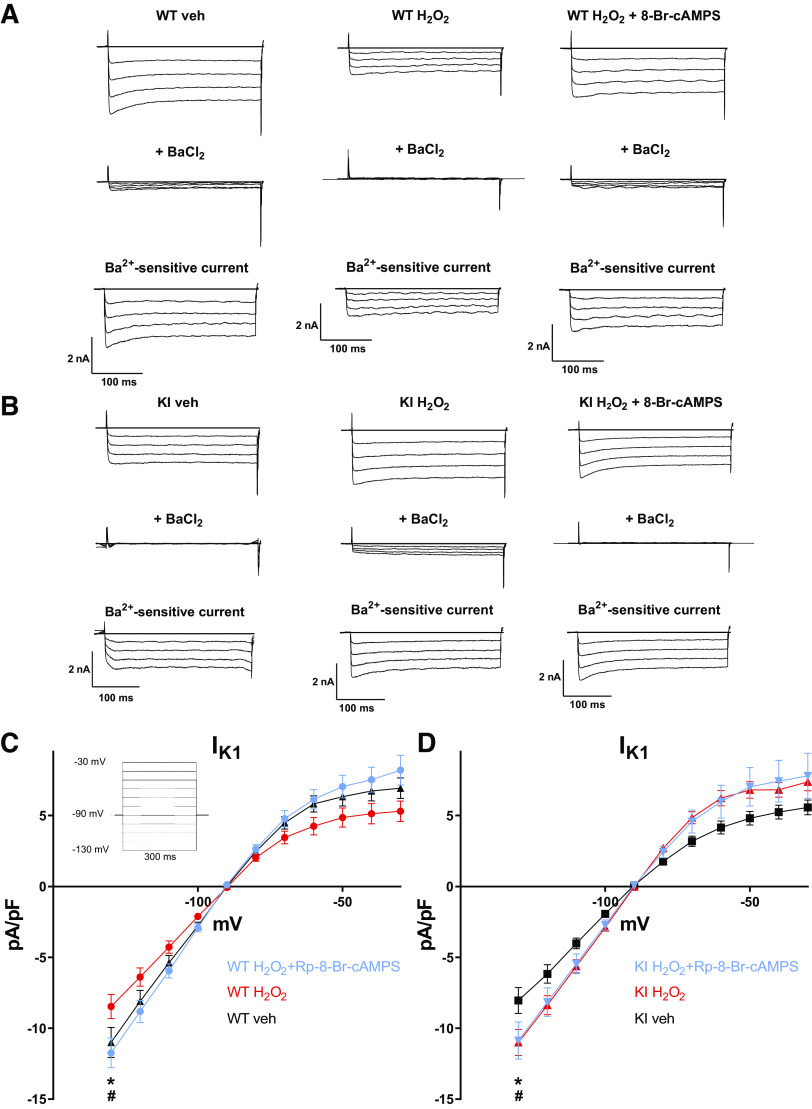

H2O2 causes inhibition of IK1 by oxidative activation of PKA.

Similar to Ito, inward rectifier potassium current (IK1) is a major contributor to cardiac repolarization. We measured IK1 by application of a voltage step protocol in ruptured whole cell patch clamp (from −130 mV to −30 mV, 10-mV steps). IK1 was blocked by exposure to BaCl2, and the Ba-sensitive current was used as a measure of IK1. Similar to inhibition of Ito, exposure of isolated WT cardiomyocytes to H2O2 resulted in a significant reduction of IK1 density. At −130 mV, compared with vehicle, H2O2 reduced IK1 from −11.67 ± 1.198 A/F to −8.47 ± 0.848 A/F [N (n) = 8 (16) vs. 8 (14); P = 0.007, Fig. 6, A and C]. This H2O2-dependent inhibition of IK1 could be prevented by preincubation with Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, pointing toward a PKA-dependent IK1 regulation. In the presence of H2O2 and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, IK1 density was 11.74 ± 1.049 A/F [N (n) = 8 (14) vs. 9 (15); P = 0.006 vs. WT + H2O2, Fig. 6, A and C].

Fig. 6.

Effect of H2O2 on inward rectifying potassium current (IK1) in WT and KI cardiomyocytes. A and B: original traces of inward currents before (top) and after (middle) BaCl2 superfusion. Digital subtraction results in the Ba2+-sensitive current IK1 (bottom). C: I–V curves of IK1 in WT cardiomyocytes reveal a significant inhibition of IK1 upon exposure to H2O2 (6–12 min) (*P < 0.05), which could be completely abolished by preincubation with the PKA-selective inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (#P < 0.05). Numbers of mice/cells were: 8/16 (Veh), 8/14 (H2O2), and 9/15 (H2O2 + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). The inset shows the applied voltage protocol. D: in contrast, IK1 increased in KI cardiomyocytes in response to H2O2, which could not be prevented by Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (*P < 0.05 vs. Veh). Numbers of mice/cells were: 7/11 (Veh), 5/10 (H2O2), and 6/13 (H2O2 + Rp-8-Br-cAMPS). Values are means ± SE. Two-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s post hoc correction. WT, wild-type; KI, knock-in; PKA, protein kinase A.

To further investigate the role of redox activation of PKA I in this context, we repeated the experiments in redox-dead PKA RI Cys17Ser knock-in mice. Interestingly, compared with WT, basal IK1 density was reduced in KI myocytes to −8.046 ± 0.915 A/F [at −130 mV N (n) = 8 (16); P < 0.05 vs. WT, Fig. 6, B and D] despite no difference in resting membrane potential or AP duration.

In accordance with reduced IK1 under basal conditions, Western blotting revealed that the expression of the main pore-forming subunit Kir2.1 was significantly diminished in KI versus WT myocytes (0.198 ± 0.014 vs. 0.323 ± 0.024 arbitrary units, N = 3 vs. 4, P = 0.0094, Supplemental Fig. S1).

Surprisingly, in contrast to WT cardiomyocytes, exposure to H2O2 caused a significant increase in IK1 to −11.000 ± 0.919 A/F in KI cardiomyocytes [at −130 mV, N (n) = 7 (11) vs. 5 (10); P = 0.01, Fig. 6, B and D]. This increase in IK1 density, however, was unaffected by preincubation with Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, suggesting that PKA is not involved. In the presence of H2O2 and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS, IK1 density was −10.866 ± 1.302 A/F [at −130 mV, N (n) = 7 (11) vs. 6 (13); P = 0.999 vs. KI + H2O2, Fig. 6, B and D].

In contrast, the H2O2-dependent increase of IK1 in KI myocytes was abolished by preincubation with the selective inhibitor of Ca/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (AIP). In the presence of H2O2 and AIP, IK1 density was −8.175 ± 0.711 A/F [N (n) = 7 (11) vs. 6 (10); P < 0.05 vs. KI + H2O2, data not shown]. Together with the lack of H2O2-dependent Ito inhibition, the H2O2-dependent increase of IK1 in KI myocytes may partly explain the lack of AP prolongation after H2O2 exposure.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the role of oxidative activation of PKA for action potentials and early afterdepolarizations in murine ventricular cardiomyocytes. We demonstrate that redox-activated PKA is involved in the ROS-induced inhibition of transient outward potassium current (Ito) and inward rectifying potassium current (IK1), which are crucial for membrane repolarization and stabilization of the resting membrane potential (41, 67, 68). Moreover, we showed that lack of oxidative PKA activation protected myocytes from H2O2-dependent APD prolongation and induction of EADs, further underscoring the pathophysiological relevance of this novel mechanism of PKA activation.

ROS signaling in the heart involves oxidative activation of PKA I.

ROS are centrally involved in cellular signaling processes mediating adaptive responses in the healthy heart (48, 50). However, under pathological conditions, for example, heart failure, ROS production exceeds the antioxidative capacity of cardiomyocytes resulting in oxidative stress, which is implicated in the development of contractile dysfunction and arrhythmias (25, 28, 60).

Interestingly, a novel cAMP-independent mechanism of PKA I activation via oxidation of its regulatory subunits (RIα) has been delineated (5). The relevance of this pathway has been confirmed in ischemia-dependent angiogenesis (5) and in PDGF-dependent signaling (13). Here, we show that ROS, which are generated by external application of H2O2, are capable of oxidizing PKA RIα subunits with a consequent increase in RI dimerization (Fig. 1) in isolated murine ventricular cardiomyocytes, suggesting a potential relevance of this pathway also in cardiac pathophysiology. It is worth noting that in contrast to KI cardiomyocytes, there was a detectable level of RI dimerization also in untreated WT cells (vehicle), probably owing to an intrinsic steady-state ROS generation in these healthy ventricular myocytes. This suggests that there may be a potential role of oxidation-activated PKA also for physiological ROS signaling.

Redox-activated PKA regulates cardiac action potential and contributes to arrhythmogenesis.

Since PKA is involved in the regulation of several ion channels, we next sought to analyze the impact of oxidation-activated PKA on the cardiac action potential. Therefore, we induced oxidative stress in WT ventricular cardiomyocytes, which, in contrast to the redox-dead KI myocytes, resulted in a marked increase in action potential duration at 90% of repolarization. Furthermore, also APD20 and APD50 were significantly increased in WT cardiomyocytes upon H2O2 treatment, pointing to alterations in ionic currents, which shape the early phase of cardiac action potential (e.g., Ito). In contrast, this H2O2-dependent effect was not observed in KI myocytes.

Importantly, H2O2 treatment significantly increased the action potential amplitude and also the upstroke velocity in both WT and KI myocytes (ANOVA P for factor H2O2 0.0018 and 0.0042, respectively), with no difference between the genotypes (P for factor genotype 0.4612 and 0.9645, respectively). Consequently, although regulation of the phase I action potential depolarization could affect AP duration, it is unlikely to explain the lack of APD prolongation in KI myocytes and may thus be a consequence of lacking oxPKA-dependent regulation of K currents.

Intriguingly, APD prolongation in WT cardiomyocytes was associated with an increased occurrence of early afterdepolarizations (EADs), as compared with in KI cardiomyocytes. EADs are defined as positive voltage deflections during repolarization of the cardiac action potential (phases 2 and 3) (62) and constitute substantial proarrhythmic events at the cellular level (64). To date, afterdepolarizations induced by oxidative stress were mainly explained by CaMKII-mediated augmentation of the late Na current (late INa) with consequent dysregulation of Na+ and Ca2+ homeostasis via Na-Ca exchanger (NCX) activity (53, 61, 69). In the present article, we tested the contribution of ROS-dependent enhancement of late INa to the generation of EADs. Interestingly, both WT and KI myocytes exposed to the selective late INa inhibitor TTX did not show any H2O2-dependent EAD formation, suggesting that late INa is critical for ROS-induced generation of EADs. There are only few and discrepant data regarding PKA-dependent regulation of late INa, suggesting that PKA is either not involved in the regulation of this current (1, 16, 27, 52) or that it may directly stimulate late INa early during the AP plateau at most positive membrane potentials (23). However, our EADs occur at much more negative membrane potentials, where late INa has been shown to be regulated by CaMKII (23). Furthermore, whether these data from rabbit myocytes can be transferred to rodent models that lack AP plateau remains elusive. Thus, oxPKA probably facilitates EAD formation by reducing the repolarization reserve, which would favor late INa-dependent EAD formation. These data are in accordance with previous publications, suggesting that redox-enhanced late INa (by oxidation of CaMKIIδ) is a major proarrhythmogenic mechanism in situations of increased ROS formation (60). Consequently, other mechanisms are likely to be involved in the PKA-dependent induction of early afterdepolarizations.

Of note, β-adrenergic signaling has been shown to stimulate EADs mainly by activation of L-type Ca2+ current (LTCC) in the setting of concomitant slow activation of the delayed rectifier potassium current IKs (35, 66). Importantly, H2O2 treatment of cardiomyocytes has been shown to rather decrease LTCC (18, 19), possibly by direct thiol-oxidation of its α1C subunit (7, 15). In parallel, the β-adrenergic responsiveness of these channels is mitigated upon oxidative stress downstream of cAMP (26), making a specific contribution of PKA-dependent dysregulation of LTCC to EAD formation in our model unlikely. Furthermore, although data on LTCC in heart failure are discrepant, most studies suggest LTCC current density to be unaltered in failing cardiomyocytes (22, 34, 40), but failing cardiomyocytes show a huge increase in the propensity for EAD formation. This suggests that a direct LTCC dysregulation by PKA is unlikely to be the main contributor to EAD formation in our model. A lack of LTCC dysregulation, however, does not prevent the LTCC-dependent generation of EADs. In contrast, since EAD take-off potential and the time of reactivation from the initial stimulus (EAD delay) are in the range of the LTCC window current (Supplemental Fig. S2, A and B), it is very likely that LTCC is involved in the EAD formation in our model.

Besides increased depolarizing currents (e.g., late INa), a reduced repolarization reserve has been found in HF and conditions of increased ROS generation (3, 34, 42). It is widely accepted that the dysregulated transient outward current Ito is critically involved in EAD formation (8, 20, 62, 65).

In accordance, our data demonstrate that PKA mediates a ROS-dependent impairment of repolarization reserve by inhibition of Ito and IK1. In consequence, depolarizing currents are more likely to induce early afterdepolarizations, especially since AP duration was also prolonged. A PKA-dependent inhibition of Ito has been described in several studies (17, 44, 49). Intriguingly, several consensus PKA phosphorylation sites were identified within the Kv4.2 and Kv1.4 α subunits, constituting Ito,fast and Ito,slow channels, respectively, with PKA-dependent phosphorylation verified in heterologous expression systems and neurons (2, 21, 44, 49, 55).

However, an A-kinase-anchoring protein targeting PKA type I to the channel subunits has not been detected to date. Of note, the fact that PKA-dependent regulation of Ito was abolished in our KI myocytes argues for a cAMP-independent mechanism involving oxidative activation of PKA.

Noteworthy, it is still heavily debated whether a decrease in Ito resulting in APD prolongation with reactivation of L-type Ca current (LTCC) and late INa or an increase in Ito, which lowers AP plateau voltage into LTCC window current range (71), is more arrhythmogenic. Importantly, species differences must be taken into account. In murine ventricular cardiomyocytes, where the contribution of Ito to membrane repolarization is much more pronounced than in rabbit or human ventricular myocytes, resulting in a more negative plateau voltage, inhibition of Ito rather than its stimulation might set the AP plateau voltage into LTCC window current range and thus facilitate EAD formation, as seen in our model.

Besides inhibition of Ito, we show here that oxidative stress also inhibits IK1 in a PKA-dependent manner, which is in accordance with several prepublished studies (9, 32, 33, 56, 57). Interestingly, Kir2.x subunits exhibit only one PKA consensus site (Ser425 and Ser430 for Kir2.1 and Kir2.2, respectively). Although PKA-dependent phosphorylation of Ser425 of Kir2.1 subunits with consequent marked inhibition of IK1 was demonstrated in a heterologous expression system (COS-7 cells) (63), there is evidence that the respective consensus site of Kir2.2 is not relevant for its PKA-dependent regulation (72), suggesting an indirect effect, for example, by phosphorylation of associated molecules within a macromolecular complex to which PKA could be targeted via A-kinase-anchoring proteins (AKAPs) (51). Importantly, the ROS-induced inhibition of IK1 was abolished in our KI myocytes lacking oxidation-sensitive RI subunits, again pointing to a direct oxidative activation of PKA instead of a cAMP-dependent pathway. Interestingly, reduced IK1 is also encountered in heart failure (3, 30, 34). Although IK1 is critical for stabilization of the resting membrane potential, it also substantially contributes to action potential repolarization (39, 68). Consequently, in a Kir2.1 knockout mouse model, action potential duration was markedly increased with an enhanced propensity for EADs (39). Noteworthy, although IK1 density was reduced by almost 95% in these ventricular myocytes, resting membrane potential was unaltered compared with wild-type (39), which is in parallel to our action potential data.

Limitations.

Although our data show a significant reduction of IK1 and Ito as well as a concomitant increase in EAD frequency, all of which are mediated by oxidation-activated PKA, we cannot preclude a possible contribution of other pathways to increased formation of EADs upon oxidative stress. EAD generation first requires a substrate, that is, APD prolongation, which renders the AP plateau phase vulnerable to the “second hit,” which is the trigger that actually induces the EAD. A simple APD prolongation alone, due to decreased potassium currents, is not sufficient to trigger EADs (31). On the other hand, any APD shortening will suppress EAD formation. We show here that the AP duration can be prolonged by oxPKA due to inhibition of repolarizing potassium currents such as Ito and IK1. If, however, oxPKA also influences the second hit—that is, the trigger—which manifests as enhanced activity of the depolarizing currents late INa, LTCC, INCX, or a combination is unclear and merits further investigation. Importantly, H2O2 exposure does not result in a selective oxidation of PKA. There are many other targets for ROS-dependent oxidation including CaMKII, which is proarrhythmic via stimulation of late INa and dysregulation of cellular Ca handling (54, 59, 60), as well as ryanodine receptors (70) with consequent increase in sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca leak, which all can contribute to EAD formation. In accordance, our data underscore the importance of late INa in the generation of EADs, as they are completely abolished in both WT and KI myocytes upon treatment with TTX. Furthermore, LTCC, which also has been shown to be critically involved in EAD formation, might also play a role in our experimental setup, since all the observed EADs take place in the LTCC window current range.

Another limitation of our study is the fact that there is apparently no significant difference in IK1 current density in the voltage range where all of the observed EADs occur. Although there is a clear trend to a reduction of IK1 in WT cardiomyocytes treated with H2O2, which cannot be detected in KI cardiomyocytes, these results do not reach statistical significance. This could in part be a result of the artificial protocol using BaCl2 to inhibit IK1. It has been shown that Ba2+-induced block of IK1 is voltage dependent, resulting in a smaller degree of block at more positive membrane potentials (29). In combination with the relatively small Ba2+ concentration used to avoid off-target effects (in other studies, concentrations of up to 1 mM are used), this could lead to an underestimation of IK1 especially at more positive membrane potentials, possibly concealing the clear effect shown at more negative potentials.

SUMMARY

Our data indicate that oxidation-activated PKA type I is critically involved in the ROS-dependent regulation of IK1 and Ito and thus contributes to APD prolongation and potentially facilitates early afterdepolarizations under conditions of oxidative stress, making it a potential target for antiarrhythmic therapy in patients with heart failure.

GRANTS

The German Cardiac Society (DGK) funded a research grant to M. Trum. S. Wagner is funded by DFG Grants WA 2539/4-1, 5-1, 7-1, and 8-1. L. S. Maier is funded by DFG grants MA 1982/5-1 and 7-1. L. S. Maier. and S. Wagner are also funded by the DFG SFB 1350 grant (Project number 387509280, TPA6). L. S. Maier and S. Wagner are supported by the ReForM C program of the faculty of medicine of the University of Regensburg.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.T. and S.W. conceived and designed research; M.T., M.M.T.I., S.L., M.B., and P.H. performed experiments; M.T. and S.W. analyzed data; M.T. and S.W. interpreted results of experiments; M.T., and S.W. prepared figures; M.T. and S.W. drafted manuscript; M.T., M.M.T.I., P.E., L.S.M., and S.W. edited and revised manuscript; all authors approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of T. Sowa and F. Radtke (both from Department of Internal Medicine II, University Hospital, Regensburg, Germany).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba T, Hesketh GG, Liu T, Carlisle R, Villa-Abrille MC, O’Rourke B, Akar FG, Tomaselli GF. Na+ channel regulation by Ca2+/calmodulin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 85: 454–463, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson AE, Adams JP, Qian Y, Cook RG, Pfaffinger PJ, Sweatt JD. Kv4.2 phosphorylation by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 275: 5337–5346, 2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beuckelmann DJ, Näbauer M, Erdmann E. Alterations of K+ currents in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circ Res 73: 379–385, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.73.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgoyne JR, Mongue-Din H, Eaton P, Shah AM. Redox signaling in cardiac physiology and pathology. Circ Res 111: 1091–1106, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgoyne JR, Rudyk O, Cho HJ, Prysyazhna O, Hathaway N, Weeks A, Evans R, Ng T, Schröder K, Brandes RP, Shah AM, Eaton P. Deficient angiogenesis in redox-dead Cys17Ser PKARIα knock-in mice. Nat Commun 6: 7920, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cesselli D, Jakoniuk I, Barlucchi L, Beltrami AP, Hintze TH, Nadal-Ginard B, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P. Oxidative stress-mediated cardiac cell death is a major determinant of ventricular dysfunction and failure in dog dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 89: 279–286, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hh1501.094115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiamvimonvat N, O’Rourke B, Kamp TJ, Kallen RG, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Marban E. Functional consequences of sulfhydryl modification in the pore-forming subunits of cardiovascular Ca2+ and Na+ channels. Circ Res 76: 325–334, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.76.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi B-R, Li W, Terentyev D, Kabakov AY, Zhong M, Rees CM, Terentyeva R, Kim TY, Qu Z, Peng X, Karma A, Koren G. Transient outward K+ current (Ito) underlies the right ventricular initiation of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in a transgenic rabbit model of long-QT syndrome type 1. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 11: e005414, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coetzee WA, Opie LH. Effects of oxygen free radicals on isolated cardiac myocytes from guinea-pig ventricle: electrophysiological studies. J Mol Cell Cardiol 24: 651–663, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)91049-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhalla AK, Hill MF, Singal PK. Role of oxidative stress in transition of hypertrophy to heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 28: 506–514, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drum BML, Yuan C, Li L, Liu Q, Wordeman L, Santana LF. Oxidative stress decreases microtubule growth and stability in ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 93: 32–43, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eager KR, Dulhunty AF. Activation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor by sulfhydryl oxidation is modified by Mg2+ and ATP. J Membr Biol 163: 9–18, 1998. doi: 10.1007/s002329900365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisel F, Boosen M, Beck M, Heide H, Wittig I, Beck K-F, Pfeilschifter J. Platelet-derived growth factor triggers PKA-mediated signalling by a redox-dependent mechanism in rat renal mesangial cells. Biochem Pharmacol 85: 101–108, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O’Donnell SE, Aykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham AJ, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell 133: 462–474, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fearon IM, Palmer AC, Balmforth AJ, Ball SG, Varadi G, Peers C. Modulation of recombinant human cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel alpha1C subunits by redox agents and hypoxia. J Physiol 514: 629–637, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.629ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frohnwieser B, Chen LQ, Schreibmayer W, Kallen RG. Modulation of the human cardiac sodium channel alpha-subunit by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and the responsible sequence domain. J Physiol 498: 309–318, 1997. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallego M, Setién R, Puebla L, Boyano-Adánez MC, Arilla E, Casis O. α1-Adrenoceptors stimulate a G αs protein and reduce the transient outward K + current via a cAMP/PKA-mediated pathway in the rat heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C577–C585, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00124.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill JS, McKenna WJ, Camm AJ. Free radicals irreversibly decrease Ca2+ currents in isolated guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 292: 337–340, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(95)90042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldhaber JI, Liu E. Excitation-contraction coupling in single guinea-pig ventricular myocytes exposed to hydrogen peroxide. J Physiol 477: 135–147, 1994. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo W, Li H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Functional consequences of elimination of i(to,f) and i(to,s): early afterdepolarizations, atrioventricular block, and ventricular arrhythmias in mice lacking Kv1.4 and expressing a dominant-negative Kv4 alpha subunit. Circ Res 87: 73–79, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond RS, Lin L, Sidorov MS, Wikenheiser AM, Hoffman DA. Protein kinase a mediates activity-dependent Kv4.2 channel trafficking. J Neurosci 28: 7513–7519, 2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1951-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He J, Conklin MW, Foell JD, Wolff MR, Haworth RA, Coronado R, Kamp TJ. Reduction in density of transverse tubules and L-type Ca(2+) channels in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 49: 298–307, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00256-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegyi B, Bányász T, Izu LT, Belardinelli L, Bers DM, Chen-Izu Y. β-adrenergic regulation of late Na+ current during cardiac action potential is mediated by both PKA and CaMKII. J Mol Cell Cardiol 123: 168–179, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill MF, Singal PK. Antioxidant and oxidative stress changes during heart failure subsequent to myocardial infarction in rats. Am J Pathol 148: 291–300, 1996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill MF, Singal PK. Right and left myocardial antioxidant responses during heart failure subsequent to myocardial infarction. Circulation 96: 2414–2420, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.7.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hool LC, Arthur PG. Decreasing cellular hydrogen peroxide with catalase mimics the effects of hypoxia on the sensitivity of the L-type Ca2+ channel to beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 91: 601–609, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000035528.00678.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horvath B, Bers DM. The late sodium current in heart failure: pathophysiology and clinical relevance. ESC Heart Fail 1: 26–40, 2014. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ide T, Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Suematsu N, Hayashidani S, Ichikawa K, Utsumi H, Machida Y, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Direct evidence for increased hydroxyl radicals originating from superoxide in the failing myocardium. Circ Res 86: 152–157, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.86.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imoto Y, Ehara T, Matsuura H. Voltage- and time-dependent block of iK1 underlying Ba2+-induced ventricular automaticity. Am J Physiol 252: H325–H333, 1987. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.2.H325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kääb S, Nuss HB, Chiamvimonvat N, O’Rourke B, Pak PH, Kass DA, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Ionic mechanism of action potential prolongation in ventricular myocytes from dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circ Res 78: 262–273, 1996. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.78.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koleske M, Bonilla I, Thomas J, Zaman N, Baine S, Knollmann BC, Veeraraghavan R, Györke S, Radwański PB. Tetrodotoxin-sensitive Navs contribute to early and delayed afterdepolarizations in long QT arrhythmia models. J Gen Physiol 150: 991–1002, 2018. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201711909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koumi S, Backer CL, Arentzen CE, Sato R. beta-Adrenergic modulation of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel in isolated human ventricular myocytes. Alteration in channel response to beta-adrenergic stimulation in failing human hearts. J Clin Invest 96: 2870–2881, 1995. doi: 10.1172/JCI118358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koumi S, Wasserstrom JA, Ten Eick RE. Beta-adrenergic and cholinergic modulation of inward rectifier K+ channel function and phosphorylation in guinea-pig ventricle. J Physiol 486: 661–678, 1995. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li G-R, Lau C-P, Ducharme A, Tardif J-C, Nattel S. Transmural action potential and ionic current remodeling in ventricles of failing canine hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1031–H1041, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00105.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu G-X, Choi B-R, Ziv O, Li W, de Lange E, Qu Z, Koren G. Differential conditions for early after-depolarizations and triggered activity in cardiomyocytes derived from transgenic LQT1 and LQT2 rabbits. J Physiol 590: 1171–1180, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.218164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maack C, Kartes T, Kilter H, Schäfers H-J, Nickenig G, Böhm M, Laufs U. Oxygen free radical release in human failing myocardium is associated with increased activity of rac1-GTPase and represents a target for statin treatment. Circulation 108: 1567–1574, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091084.46500.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallat Z, Philip I, Lebret M, Chatel D, Maclouf J, Tedgui A. Elevated levels of 8-iso-prostaglandin F2alpha in pericardial fluid of patients with heart failure: a potential role for in vivo oxidant stress in ventricular dilatation and progression to heart failure. Circulation 97: 1536–1539, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.16.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthias K, Seifert G, Reinhardt S, Steinhäuser C. Modulation of voltage-gated K(+) channels Kv11 and Kv1 4 by forskolin. Neuropharmacology 43: 444–449, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(02)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLerie M, Lopatin AN. Dominant-negative suppression of I(K1) in the mouse heart leads to altered cardiac excitability. J Mol Cell Cardiol 35: 367–378, 2003. [Erratum in J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 423, 2005]. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2828(03)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mewes T, Ravens U. L-type calcium currents of human myocytes from ventricle of non-failing and failing hearts and from atrium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 26: 1307–1320, 1994. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miake J, Marbán E, Nuss HB. Functional role of inward rectifier current in heart probed by Kir2.1 overexpression and dominant-negative suppression. J Clin Invest 111: 1529–1536, 2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI200317959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Näbauer M, Kääb S. Potassium channel down-regulation in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 37: 324–334, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neef S, Sag CM, Daut M, Bäumer H, Grefe C, El-Armouche A, DeSantiago J, Pereira L, Bers DM, Backs J, Maier LS. While systolic cardiomyocyte function is preserved, diastolic myocyte function and recovery from acidosis are impaired in CaMKIIδ-KO mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol 59: 107–116, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niwa N, Nerbonne JM. Molecular determinants of cardiac transient outward potassium current (I(to)) expression and regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 12–25, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piedras-Rentería ES, Sherwood OD, Best PM. Effects of relaxin on rat atrial myocytes. I. Inhibition of I(to) via PKA-dependent phosphorylation. Am J Physiol 272: H1791–H1797, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pogwizd SM, Hoyt RH, Saffitz JE, Corr PB, Cox JL, Cain ME. Reentrant and focal mechanisms underlying ventricular tachycardia in the human heart. Circulation 86: 1872–1887, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.86.6.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pogwizd SM, McKenzie JP, Cain ME. Mechanisms underlying spontaneous and induced ventricular arrhythmias in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 98: 2404–2414, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.22.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhee SG. Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science 312: 1882–1883, 2006. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schrader LA, Anderson AE, Mayne A, Pfaffinger PJ, Sweatt JD. PKA modulation of Kv4.2-encoded A-type potassium channels requires formation of a supramolecular complex. J Neurosci 22: 10123–10133, 2002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10123.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sena LA, Chandel NS. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell 48: 158–167, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seyler C, Scherer D, Köpple C, Kulzer M, Korkmaz S, Xynogalos P, Thomas D, Kaya Z, Scholz E, Backs J, Karle C, Katus HA, Zitron E. Role of plasma membrane-associated AKAPs for the regulation of cardiac IK1 current by protein kinase A. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 390: 493–503, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00210-017-1344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shryock JC, Song Y, Rajamani S, Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L. The arrhythmogenic consequences of increasing late INa in the cardiomyocyte. Cardiovasc Res 99: 600–611, 2013. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song Y, Shryock JC, Wagner S, Maier LS, Belardinelli L. Blocking late sodium current reduces hydrogen peroxide-induced arrhythmogenic activity and contractile dysfunction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 318: 214–222, 2006. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swaminathan PD, Purohit A, Soni S, Voigt N, Singh MV, Glukhov AV, Gao Z, He BJ, Luczak ED, Joiner ML, Kutschke W, Yang J, Donahue JK, Weiss RM, Grumbach IM, Ogawa M, Chen PS, Efimov I, Dobrev D, Mohler PJ, Hund TJ, Anderson ME. Oxidized CaMKII causes cardiac sinus node dysfunction in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 3277–3288, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI57833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tao Y, Zeng R, Shen B, Jia J, Wang Y. Neuronal transmission stimulates the phosphorylation of Kv1.4 channel at Ser229 through protein kinase A1. J Neurochem 94: 1512–1522, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaidyanathan R, Taffet SM, Vikstrom KL, Anumonwo JMB. Regulation of cardiac inward rectifier potassium current (I(K1)) by synapse-associated protein-97. J Biol Chem 285: 28000–28009, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vega AL, Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ, Makielski JC. Protein kinase A-dependent biophysical phenotype for V227F-KCNJ2 mutation in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2: 540–547, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.872309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner S, Dantz C, Flebbe H, Azizian A, Sag CM, Engels S, Möllencamp J, Dybkova N, Islam T, Shah AM, Maier LS. NADPH oxidase 2 mediates angiotensin II-dependent cellular arrhythmias via PKA and CaMKII. J Mol Cell Cardiol 75: 206–215, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wagner S, Rokita AG, Anderson ME, Maier LS. Redox regulation of sodium and calcium handling. Antioxid Redox Signal 18: 1063–1077, 2013. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wagner S, Ruff HM, Weber SL, Bellmann S, Sowa T, Schulte T, Anderson ME, Grandi E, Bers DM, Backs J, Belardinelli L, Maier LS. Reactive oxygen species-activated Ca/calmodulin kinase IIδ is required for late I(Na) augmentation leading to cellular Na and Ca overload. Circ Res 108: 555–565, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wagner S, Seidler T, Picht E, Maier LS, Kazanski V, Teucher N, Schillinger W, Pieske B, Isenberg G, Hasenfuss G, Kögler H. Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchanger overexpression predisposes to reactive oxygen species-induced injury. Cardiovasc Res 60: 404–412, 2003. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiss JN, Garfinkel A, Karagueuzian HS, Chen P-S, Qu Z. Early afterdepolarizations and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 7: 1891–1899, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wischmeyer E, Karschin A. Receptor stimulation causes slow inhibition of IRK1 inwardly rectifying K+ channels by direct protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 5819–5823, 1996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wit AL. Afterdepolarizations and triggered activity as a mechanism for clinical arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 41: 883–896, 2018. doi: 10.1111/pace.13419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Workman AJ, Marshall GE, Rankin AC, Smith GL, Dempster J. Transient outward K+ current reduction prolongs action potentials and promotes afterdepolarisations: a dynamic-clamp study in human and rabbit cardiac atrial myocytes. J Physiol 590: 4289–4305, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.235986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xie Y, Grandi E, Puglisi JL, Sato D, Bers DM. β-adrenergic stimulation activates early afterdepolarizations transiently via kinetic mismatch of PKA targets. J Mol Cell Cardiol 58: 153–161, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu H, Li H, Nerbonne JM. Elimination of the transient outward current and action potential prolongation in mouse atrial myocytes expressing a dominant negative Kv4 alpha subunit. J Physiol 519: 11–21, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0011o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zaritsky JJ, Redell JB, Tempel BL, Schwarz TL. The consequences of disrupting cardiac inwardly rectifying K(+) current (I(K1)) as revealed by the targeted deletion of the murine Kir2.1 and Kir2.2 genes. J Physiol 533: 697–710, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00697.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zeitz O, Maass AE, Van Nguyen P, Hensmann G, Kögler H, Möller K, Hasenfuss G, Janssen PML. Hydroxyl radical-induced acute diastolic dysfunction is due to calcium overload via reverse-mode Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchange. Circ Res 90: 988–995, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000018625.25212.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y, Qi Y, Li J-J, He W-J, Gao X-H, Zhang Y, Sun X, Tong J, Zhang J, Deng X-L, Du X-J, Xie W. Stretch-induced sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak is causatively associated with atrial fibrillation in pressure-overloaded hearts. Cardiovasc Res in press: cvaa163, 2020. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao Z, Xie Y, Wen H, Xiao D, Allen C, Fefelova N, Dun W, Boyden PA, Qu Z, Xie L-H. Role of the transient outward potassium current in the genesis of early afterdepolarizations in cardiac cells. Cardiovasc Res 95: 308–316, 2012. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zitron E, Kiesecker C, Lück S, Kathöfer S, Thomas D, Kreye VAW, Kiehn J, Katus HA, Schoels W, Karle CA. Human cardiac inwardly rectifying current IKir2.2 is upregulated by activation of protein kinase A. Cardiovasc Res 63: 520–527, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]