Abstract

Although the contribution of noncardiac complications to the pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) have been increasingly recognized, disease-related changes in peripheral vascular control remain poorly understood. We utilized small muscle mass handgrip exercise to concomitantly evaluate exercising muscle blood flow and conduit vessel endothelium-dependent vasodilation in individuals with HFpEF (n = 25) compared with hypertensive controls (HTN) (n = 25). Heart rate (HR), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), mean arterial pressure (MAP), brachial artery blood velocity, and brachial artery diameter were assessed during progressive intermittent handgrip (HG) exercise [15–30–45% maximal voluntary contraction (MVC)]. Forearm blood flow (FBF) and vascular conductance (FVC) were determined to quantify the peripheral hemodynamic response to HG exercise, and changes in brachial artery diameter were evaluated to assess endothelium-dependent vasodilation. HR, SV, and CO were not different between groups across exercise intensities. However, although FBF was not different between groups at the lowest exercise intensity, FBF was significantly lower (20–40%) in individuals with HFpEF at the two higher exercise intensities (30% MVC: 229 ± 8 versus 274 ± 23 ml/min; 45% MVC: 283 ± 17 versus 399 ± 34 ml/min, HFpEF versus HTN). FVC was not different between groups at 15 and 30% MVC but was ∼20% lower in HFpEF at the highest exercise intensity. Brachial artery diameter increased across exercise intensities in both HFpEF and HTN, with no difference between groups. These findings demonstrate an attenuation in muscle blood flow during exercise in HFpEF in the absence of disease-related changes in central hemodynamics or endothelial function.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The current study identified, for the first time, an attenuation in exercising muscle blood flow during handgrip exercise in individuals with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) compared with overweight individuals with hypertension, two of the most common comorbidities associated with HFpEF. These decrements in exercise hyperemia cannot be attributed to disease-related changes in central hemodynamics or endothelial function, providing additional evidence for disease-related vascular dysregulation, which may be a predominant contributor to exercise intolerance in individuals with HFpEF.

Keywords: blood flow, endothelium-dependent vasodilation, exercise hyperemia, small muscle mass handgrip exercise

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) affects over 5 million people in the U.S. alone (28), with health care costs surpassing $30 billion annually (33). While heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) has been studied extensively over the past three decades (86), much less is known about heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (7, 15), the ever-growing and predominant form of HF (55). While there are many differences in both the etiology and treatment of these HF phenotypes, the clinical presentation is remarkably similar, with both populations exhibiting the key characteristics of dyspnea upon exertion and severe exercise intolerance (40). Although cardiac abnormalities such as ventricular stiffening and elevated filling pressure in individuals with HFpEF may contribute to these symptoms, disease-related changes in the peripheral circulation may also play a significant role in this patient population. Indeed, the importance of noncardiac complications to HFpEF pathophysiology has been increasingly recognized (8, 20, 43, 44, 57), and evidence is accumulating that supports the link between disease-related changes in the peripheral circulation and exercise capacity in this patient group.

Given the well-defined relationship between exercising limb blood flow, O2 uptake, and exercise capacity (4, 64), it stands to reason that a disease-related change in the peripheral circulation could be an important contributor to exercise intolerance in individuals with HFpEF. While a small number of studies have been undertaken to evaluate the cardiovascular responses to exercise in HFpEF (11–13, 38), it is noteworthy that the majority of studies, to date, have utilized an upright cycling exercise paradigm, a large muscle mass exercise modality that imposes significant central hemodynamic stress that may amplify cardiac limitations and therefore mask potential dysfunction of the peripheral vasculature. To isolate central and peripheral contributions to exercising limb blood flow, we recently undertook a study in individuals with HFpEF using the knee-extensor model, a small muscle mass exercise modality that provokes minimal cardiopulmonary stress (67). In this study, we identified a 15–20% attenuation in leg blood flow in individuals with HFpEF compared with healthy controls in the face of similar changes in central hemodynamics (44), providing new evidence of a disease-related dysregulation in the exercising skeletal muscle vasculature that cannot be attributed to cardiac dysfunction. However, whether a similar impairment in blood flow regulation is also present during small muscle mass upper body exercise, a modality that is associated with exercise capacity and many activities of daily living in heart failure (36), has not been evaluated. Heterogeneity in vascular control between limbs has been well reported in both health and disease (51, 52, 68, 82, 83), supporting the value of utilizing multiple exercise modalities across different limbs to fully characterize the regulation of exercising muscle blood flow.

The handgrip exercise model further provides the unique opportunity to not only evaluate exercising limb blood flow (i.e., “exercise-induced hyperemia”) but also to concomitantly assess endothelium-dependent vasodilation in response to the sustained increase in brachial artery shear stress provoked by exercise. Our group (78, 84) and others (77) have developed the “sustained shear” approach as an alternative to the more traditional flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) test of vascular function to provide a more comprehensive, noninvasive assessment of brachial artery vasodilatory capacity. Given the established role of nitric oxide (NO) in governing brachial artery vasodilation during handgrip exercise (78, 84), this unique vascular test can inform the growing interest in how this pathway contributes to the pathophysiology of HFpEF (72). Furthermore, considering emerging evidence from our group (43) and others (1, 47) that disease-related changes in the peripheral vasculature may manifest differently in conduit and microvascular regions of the vascular tree, the combined assessment of brachial artery vasodilation and the exercise-induced hyperemic response may be particularly informative to the ongoing efforts aimed at better defining vascular regulation in individuals with HFpEF.

Therefore, utilizing handgrip exercise, which recruits on a small muscle mass, we sought to evaluate exercise-induced changes in peripheral hemodynamics and brachial artery vasodilation in individuals with HFpEF compared with individuals with hypertension (HTN) who were also matched for higher body mass index (BMI), since hypertension and obesity are two of the most common comorbid risk factors associated with HFpEF (10, 23, 42, 54, 79). There were two primary hypotheses: 1) we hypothesized that exercise-induced changes in central hemodynamics would not be different between groups but that exercising muscle blood flow would be attenuated in individuals with HFpEF compared with HTN, and 2) based on the emerging concept that conduit vessel function is preserved in HFpEF, we hypothesized that brachial artery flow-mediated dilation, stimulated by exercise-induced increases in shear stress, would not be different between individuals with HFpEF and HTN.

METHODS

Subjects.

All subjects were recruited from the Hypertension and HF clinics at the University of Utah, the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC), and the greater Salt Lake City community. Individuals with hypertension and with similar body mass index (BMI) were studied as control subjects in this investigation due to the high prevalence of hypertension and excessive adiposity being comorbidities associated with HFpEF (10, 23, 42, 54). With excess adiposity and hypertension being two modifiable risk factors associated with HFpEF, these comorbidities are often controlled for to identify differences specific to patients with HFpEF (41, 42, 49, 79). Control group inclusion criteria included 1) a clinical diagnosis of hypertension (seated blood pressure >140/90 mmHg), as determined by the participants primary care physician using the standard diagnostic algorithm according to the European Society of Cardiology (81), and 2) BMI between 25 and 45 kg/m2. HFpEF patient inclusion criteria were consistent with the TOPCAT trial (19), which are as follows: 1) HF defined by the presence of more than or at least one symptom at the time of screening (paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion) and one sign (edema, elevation in jugular venous distention) in the previous 12 mo; 2) left ventricular ejection fraction ≥45%; 3) controlled systolic blood pressure; and 4) either more than or at least one hospitalization in the previous 12 mo for which HF was a major component of hospitalization or an elevated (≥100 pg/mL) B-type natriuretic peptide in the previous 60 days. Exclusion criteria for the HFpEF group included significant valvular heart disease, acute atrial fibrillation, and any orthopedic limitations that would prevent performance of handgrip exercise. With recognition of the high prevalence of obesity that characterizes the HFpEF phenotype (54), we enrolled patients with a BMI between 25 and 45 kg/m2. Participants with a body mass index (BMI) >45 kg/m2 were excluded due to technical challenges associated with ultrasonography in morbidly obese subjects. All participants were nonsmokers. All procedures were approved by the University of Utah and the Salt Lake City VAMC Institutional Review Boards, and studies were performed at the VA Salt Lake City Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center in the Utah Vascular Research Laboratory following informed consent from participants.

Protocols.

On the experimental day, participants reported to the laboratory ∼8 h postprandial and provided a venous blood sample. Subjects remained on their normal medication regimen. Height and weight were measured to calculate body surface area (BSA) using the Haycock method (30) as BSA (m2) = 0.024265 (height, m)0.3964 × (weight, kg)0.5378. Data collection took place in a thermoneutral environment, with participants in the supine position.

Handgrip exercise.

Subjects rested in the supine position for ∼20 min before the start of data collection with the right arm abducted at 90°. The elbow joint was extended at heart level to allow individuals to perform the handgrip (HG) exercise. First, maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) was established by taking the highest value of three maximal contractions using a handgrip dynamometer (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA). Intermittent isometric HG exercise was performed at three workloads based on each individual’s respective MVC (15, 30, and 45% of MVC, 1 Hz, 3 min per exercise stage), with force output displayed to provide visual feedback.

Central hemodynamic variables.

Heart rate (HR), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) were determined noninvasively using photoplethysmography (Finometer, Finapres Medical Systems BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Heart rate was monitored from a standard three-lead electrocardiogram recorded in duplicate on the data acquisition system (Biopac, Goleta, CA) and GE Ultrasound Doppler. SV was calculated using the Modelflow method, which includes age, sex, height, and weight in its algorithm (Beatscope version 1.1; Finapres Medical Systems BS, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) (9) and has been documented to accurately track SV during a variety of experimental protocols, including exercise (17, 18, 75). CO was calculated as CO (l/min) = HR × SV. Stroke index (SI; ml/m2) and cardiac index (CI; L·min·m2) were calculated relative to BSA (m2). MAP was calculated as MAP (mmHg) = diastolic arterial pressure + (pulse pressure × 0.33).

Ultrasound Doppler.

Brachial artery blood velocity and vessel diameter were determined in the right arm using an ultrasound Doppler system (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). The brachial artery was insonated approximately midway between the antecubital and axillary regions, medial to the biceps brachii muscle. Blood velocity was collected at a Doppler frequency of 5 MHz in high-pulsed repetition frequency mode (2–25 kHz). Sample volume was optimized in relation to vessel diameter and centered within the vessel. Vessel diameter was obtained during end diastole (corresponding to each R wave documented by the simultaneous ECG signal) using the same transducer at an imaging frequency ranging from 9 to 14 MHz. An angle of insonation of ≤60 degrees (45) was achieved for all measurements. Brachial artery vasodilation was determined offline from end-diastolic, ECG R-wave-triggered images collected from the ultrasound Doppler using automated edge-detection software (Medical Imaging Applications, Coraville, IA) (56). Ultrasound Doppler measurements were performed continuously, with the last 60 s of each exercise intensity used for the determination of limb blood flow. Forearm blood flow (FBF) was calculated with the formula: FBF (ml/min) = [Vmean × π (vessel diameter/2)2 × 60], and forearm vascular conductance (FVC) was calculated as FVC (ml·min−1·mmHg) = FBF/mean arterial pressure (MAP). Shear rate (SR) was calculated as SR (s−1) = 8 × Vmean/arterial diameter.

Statistical analyses.

Statistics were performed using commercially available software (SigmaStat 3.10; Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA). A 2 × 4 repeated-measures ANOVA (α < 0.05) (group, 2 levels: HTN versus HFpEF) (workload, 4 levels: rest, 15, 30, and 45% of MVC) was performed to compare the hemodynamic responses in HTN and HFpEF groups during exercise. The Holm-Sidak method was used for alpha adjustment and post hoc analysis. The slope of the shear rate over brachial artery diameter was compared between groups using a two-tailed t-test. Subject characteristics are expressed as means ± SD, and all other data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics.

Anthropometric data for subjects with HTN or HFpEF as well as clinical biomarkers for the subjects with HFpEF are reported in Table 1. Disease-specific characteristics and pharmacological therapeutic information for both groups are presented in Table 2. Echocardiographic information and circulating biomarkers commonly presented among heart failure severity assessments (26) for subjects with HFpEF are provided in Table 3. Importantly, handgrip maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) was not different between groups (20 ± 4 versus 18 ± 6 kg, HTN versus HFpEF), allowing the use of relative exercise intensities to evaluate hemodynamic responses to submaximal handgrip exercise. Among the female participants, 50% of the females (5 out of 10) in the HTN group were confirmed as postmenopausal while 93% of the females (13 out of 14) in the HFpEF group were confirmed as postmenopausal (P < 0.05, group difference). One female in the HFpEF group and two females in the HTN group could not be verified as pre-, peri-, or postmenopausal. Additionally, none of the females in the HTN group were on hormone replacement therapy, while one female in the HFpEF group was on hormonal replacement therapy.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and clinical biomarkers

| HTN | HFpEF | |

|---|---|---|

| n, M/F | 15/10 | 11/14 |

| Age, yr | 53 ± 7 | 69 ± 10* |

| Height, cm | 172 ± 9 | 168 ± 12 |

| Weight, kg | 91 ± 22 | 94 ± 23 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30 ± 6 | 33 ± 6 |

| BSA, m2 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| Handgrip MVC, kg | 20 ± 4 | 18 ± 6 |

Values are means ± SD. HTN, hypertension; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; F, females; M, males; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; MVC, Maximal voluntary contraction.

P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Disease characteristics and medications

| HTN (n, M/F) | HFpEF (n, M/F) | |

|---|---|---|

| Disease characteristics | ||

| NYHA class II | 7/7 | |

| NYHA class III | 2/7 | |

| NYHA class IV | 2/0 | |

| Diabetes | 0/0 | 4/4 |

| COPD | 0/0 | 2/0 |

| CAD | 1/1 | 2/4 |

| Hypertension | 15/10 | 7/11 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3/1 | 5/7 |

| Medications | ||

| Beta-blockers | 2/0 | 3/9 |

| ACEi | 3/2 | 3/7 |

| ARB | 1/1 | 3/3 |

| Loop diuretics | 0/0 | 9/14 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 1/1 | 7/12 |

| Statin | 1/1 | 5/11 |

| Nitrates | 0/1 | 2/3 |

| Ca2+ channel blocker | 0/1 | 1/2 |

| Rx types taken | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 1.3 |

Values for Rx types taken are means ± SD. HTN, hypertension; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; ACEi, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; NYHA class, New York Heart Association functional classification; Rx, prescription.

Table 3.

Echocardiogram and clinical biomarker characteristics specific to the group with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Echocardiogram | |

| Ejection fraction, % | 63 ± 7 |

| LV IVSD, cm | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| LV PWD, cm | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| LV ID diastole, cm | 4.5 ± 0.7 |

| LV ID systole, cm | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| Peak E wave, cm/s | 95 ± 26 |

| Peak A wave, cm/s | 99 ± 43 |

| E/A ratio | 1.2 ± 0.8 |

| E’ lateral wall, cm/s | 7 ± 2 |

| E/E’ lateral ratio | 16 ± 7 |

| Mitral E-wave deceleration time, ms | 248 ± 54 |

| Clinical biomarkers | |

| BNP, pg/ml | 64 ± 71 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 5783 ± 1462 |

| ST2, ng/ml | 52 ± 34 |

| Galectin-3, ng/ml | 15 ± 5 |

| Cystatin C, ng/ml | 18 ± 5 |

Values are means ± SD. LV, left ventricle; IVSD, interventricular septum thickness at end-diastole; PWD, posterior wall thickness; ID, internal dimension; E wave, peak velocity of early diastolic transmitral flow; A wave, peak velocity of late transmitral flow; E’, peak velocity of early diastolic mitral annular motion, BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; NT-proBNP, NH2-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; ST2, suppression of tumorigenicity.

Central hemodynamics.

The central hemodynamic responses to handgrip exercise in subjects with HTN and HFpEF are presented in Table 4. Generally, the central hemodynamic response to handgrip exercise was not different between subjects with HTN and HFpEF groups, although the HTN group had a higher diastolic blood pressure (group effect, P < 0.05). The groups had similar SV, SI, CO, and CI at rest and throughout exercise (P > 0.05). Heart rate increased slightly in both groups with the onset of exercise (interaction effect, P < 0.05) and was significantly greater than rest at 45% MVC in both groups (HTN: 8 ± 2 beats/min compared with rest; HFpEF: 10 ± 2 beats/min compared with rest; interaction effect, P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Cardiovascular responses to supine rhythmic handgrip exercise

| Relative Handgrip Intensity, %MVC |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest |

15% |

30% |

45% |

|||||

| HTN | HFpEF | HTN | HFpEF | HTN | HFpEF | HTN | HFpEF | |

| Systolic arterial pressure, mmHg | 146 ± 4 | 138 ± 6 | 160 ± 5 | 148 ± 7 | 154 ± 6 | 161 ± 6 | 171 ± 6† | 166 ± 7† |

| Diastolic arterial pressure, mmHg | 68 ± 3 | 55 ± 3* | 74 ± 3 | 61 ± 4* | 64 ± 3 | 62 ± 4* | 78 ± 3 | 68 ± 4*† |

| Pulse pressure, mmHg | 78 ± 5 | 83 ± 4 | 87 ± 5 | 86 ± 5 | 87 ± 5 | 92 ± 5 | 93 ± 6 | 98 ± 5 |

| Heart rate, beat/min | 64 ± 2 | 62 ± 2 | 67 ± 2 | 69 ± 2† | 68 ± 2 | 68 ± 2 | 71 ± 2† | 72 ± 2† |

| Stroke volume, ml/beat | 107 ± 6 | 127 ± 11 | 109 ± 7 | 126 ± 12 | 122 ± 12 | 112 ± 7 | 110 ± 6 | 121 ± 12 |

| Stroke index, ml/m2 | 51 ± 2 | 58 ± 4 | 51 ± 2 | 58 ± 5 | 52 ± 2 | 56 ± 5 | 52 ± 2 | 56 ± 5 |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 7.7 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 8.2 ± 0.7 | 7.5 ± 0.4 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 0.8 |

| Cardiac Index, L·min−1·m−2 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.3 |

Values are means ± SE. HTN, hypertension; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; MVC, maximal voluntary contraction. A 2 × 4 repeated-measures ANOVA (α < 0.05) (group, 2 levels: control vs. HFpEF) (workload, 4 levels: rest, 15, 30, and 45% of MVC) was performed to compare the hemodynamic responses in HTN and HFpEF groups during exercise.

Significant difference from control, P < 0.05.

Significant difference from rest, P < 0.05.

Peripheral hemodynamics.

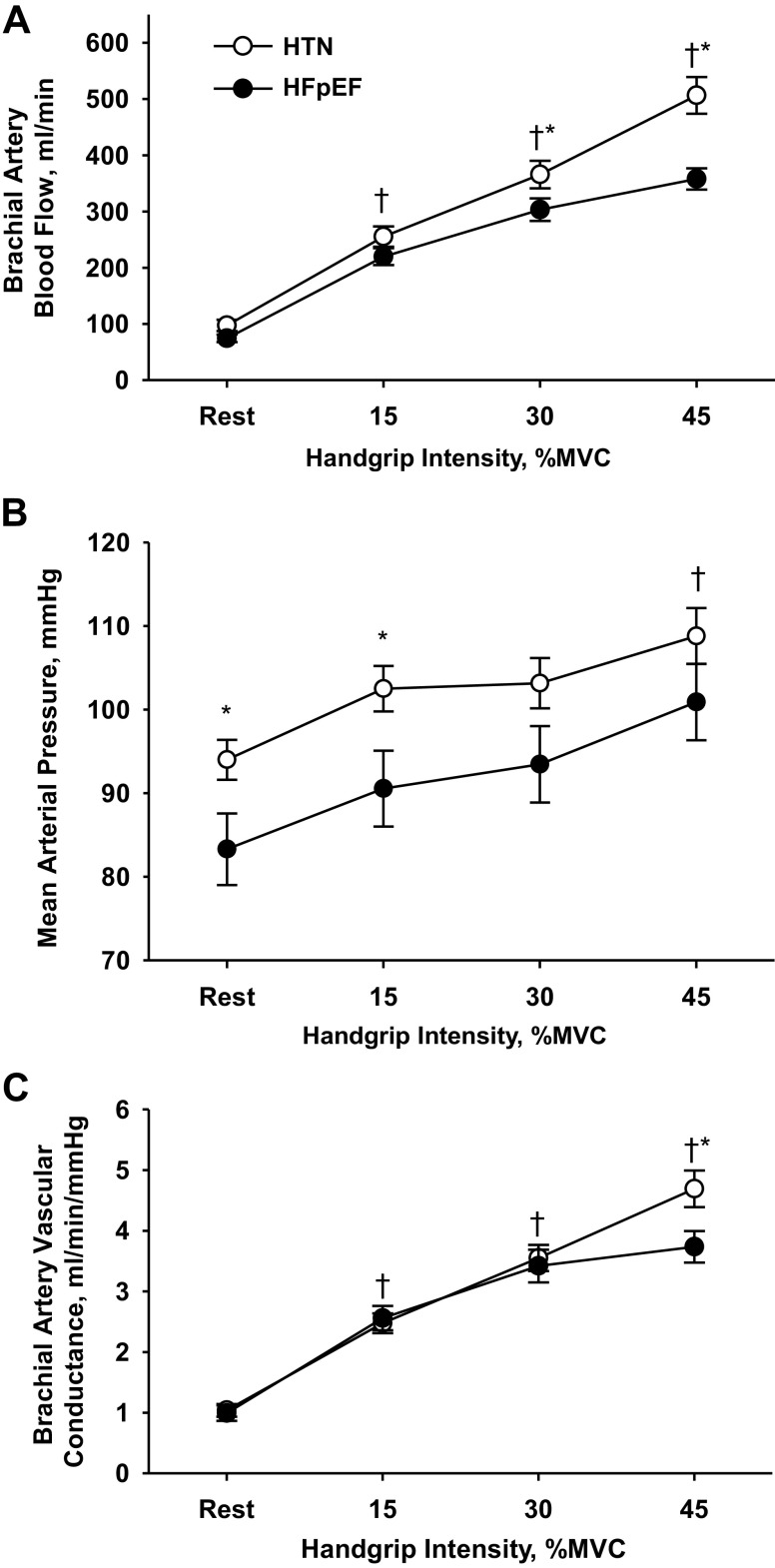

Forearm blood flow progressively increased across the increasing intensities of handgrip exercise for both groups, but was 20–40% lower in the patients with HFpEF compared with HTN at both 30% and 45% MVC (Fig. 1A). As anticipated, MAP was ∼11 mmHg higher at rest and ∼12 mmHg higher during the 15% exercise intensity in the HTN group, with similar MAP changes from rest to exercise in both groups (15%MVC: HTN: +9 ± 1 mmHg, HFpEF: +7 ± 2 mmHg, P = 0.63; 30%MVC: HTN: +9 ± 2 mmHg, HFpEF: +10 ± 2 mmHg, P = 0.72; 45%MVC: HTN: +15 ± 2 mmHg; and HFpEF: +18 ± 3 mmHg, P = 0.44; compared with baseline) (Fig. 1B). When forearm vascular conductance was calculated to normalize forearm blood flow for these differences in MAP, between-group differences were still evident at the highest (45%MVC) exercise intensity (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Forearm blood flow (A), mean arterial blood pressure (B), and forearm vascular conductance (C) during supine rhythmic handgrip exercise in individuals with hypertension (HTN) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). A 2 × 4 repeated-measures ANOVA (α < 0.05) (group, 2 levels: control vs. HFpEF) [workload, 4 levels: rest, 15, 30, and 45% of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC)] was performed to compare the hemodynamic responses in HTN and HFpEF groups during exercise. Data are presented as means ± SE.* Significant difference from control, P < 0.05. †Significant difference from rest, P < 0.05.

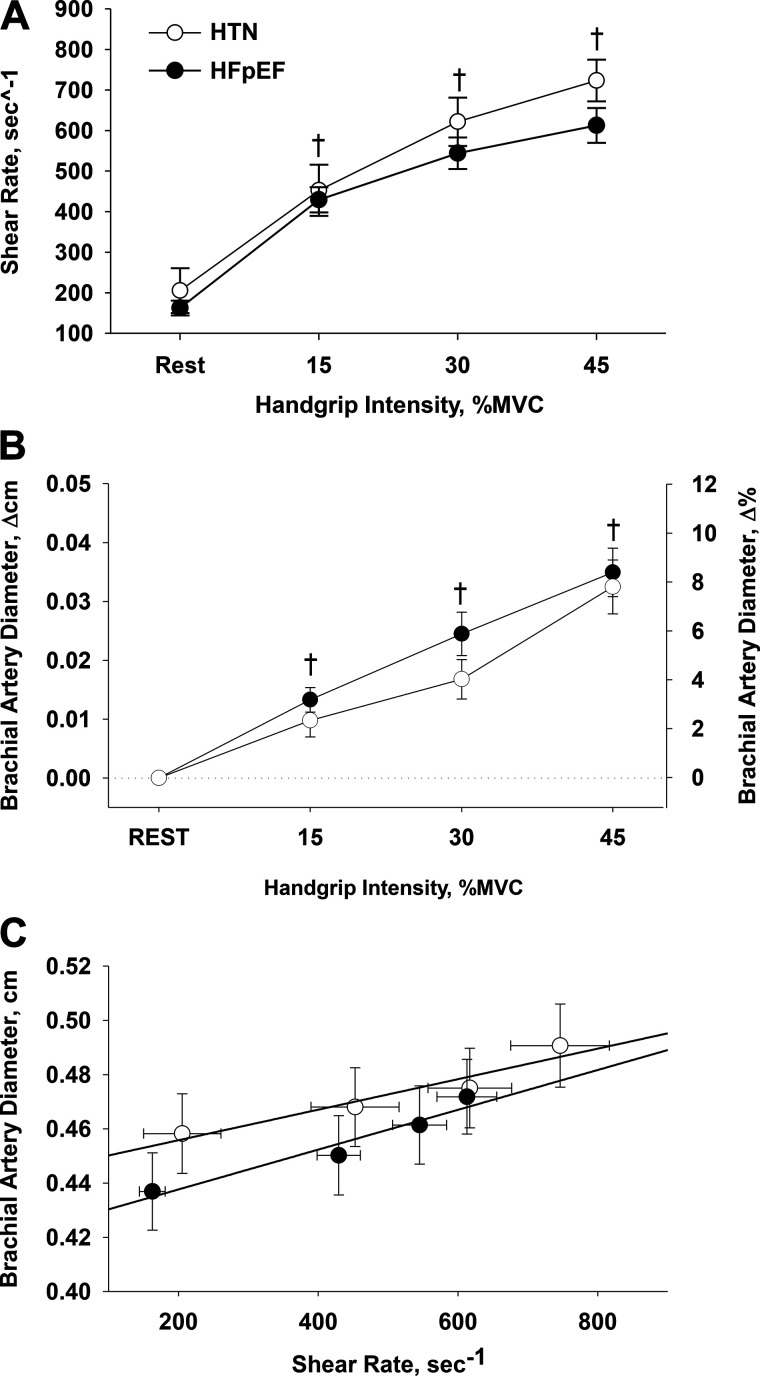

Brachial artery shear rate progressively increased across the increasing intensities of handgrip exercise for both groups (P < 0.05), with a tendency (P = 0.056) for a between-group difference at 45%MVC (Fig. 2A). Similarly, brachial artery dilation increased in a stepwise manner across the increasing intensities of handgrip exercise in both groups (Fig. 2B). When the relationship between shear rate and brachial artery diameter was assessed, similar slopes were observed between the HTN (5.4E-5 ± 9.2E-6) and HFpEF (8.5E-5 ± 1.5E-5) groups (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Brachial artery shear rate (A), brachial artery diameter (B), and the relationship between brachial artery shear rate and the associated brachial artery diameter (C) during supine rhythmic handgrip exercise in individuals with hypertension (HTN) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). A 2 × 4 repeated-measures ANOVA (α < 0.05) (group, 2 levels: HTN vs. HFpEF) [workload, 4 levels: rest, 15, 30, and 45% of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC)] was performed to compare the hemodynamic responses in control and HFpEF during exercise. Data are presented as means ± SE. †Significant difference from rest, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This study provides significant new insight regarding both exercising skeletal muscle blood flow and peripheral vascular function in subjects with HFpEF. Although FBF was not different between HTN and HFpEF groups at the lowest exercise intensity, it was attenuated by 20–40% in subjects with HFpEF compared with subjects with HTN at the two higher exercise intensities. FVC was not different between groups at 15 and 30% MVC but was ≈20% lower in HFpEF at the highest exercise intensity. The use of the handgrip exercise modality provoked only minimal changes in central hemodynamics, which were not different between groups, suggesting that the observed impairments in skeletal muscle blood flow and vascular conductance were not attributable to disease-related changes in cardiac function. This exercise model also exposes the brachial artery to step-wise increases in sustained shear stress, providing the additional opportunity to evaluate conduit vessel endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Interestingly, both the brachial artery shear rate and the associated vasodilation were similar between groups, suggesting an absence of overt vascular dysfunction in the conduit artery of subjects with HFpEF. Taken together, these findings suggest an impaired hyperemic response during small muscle mass exercise, but a preservation of conduit vessel endothelial function, in subjects with HFpEF even when controlling for two of the most common comorbidities in HFpEF, obesity, and hypertension.

Regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise in HFpEF.

Exercise intolerance is a defining symptom of HFpEF, with cardiac, pulmonary, autonomic, metabolic, and vascular factors all likely contributing to the multifactorial nature of the disease. While diastolic dysfunction is a hallmark feature of HFpEF, decrements in cardiac function do not appear to fully explain the degree of exercise intolerance in this patient group (14, 48, 62, 74, 88, 89), supporting the possibility of peripheral hemodynamic dysfunction as a contributor to the development of exertional symptoms. Using a submaximal seated cycling exercise modality, Borlaug et al. (11) identified an impairment in systemic vascular resistance in HFpEF, suggesting an alteration in “vasodilatory reserve” during exercise in this patient group (11). However, during this type of whole body exercise, disease-related impairments in both peripheral and central hemodynamics may contribute to exercise tolerance (59, 70, 71). Building on this previous study, we recently evaluated skeletal muscle blood flow in individuals with HFpEF using a small muscle mass, knee-extensor, exercise modality that evokes minimal cardiopulmonary stress and identified a 15–25% attenuation in leg blood flow in individuals with HFpEF compared with healthy, age-matched controls (43). However, these previous studies in the lower limbs left unanswered whether dysregulation in exercising skeletal muscle blood flow might also exist during upper body exercise as well as the contribution on conduit versus microvascular impairments, which may be an important distinction given the well-known heterogeneity in vascular regulation between limbs (51, 52, 68, 82, 83). Furthermore, our previous study (43) utilizing the knee-extensor exercise modality compared patients to healthy, age-matched controls, leaving some uncertainty regarding the impact of comorbidities on the observed decrement in blood flow in individuals with HFpEF. The current study thus extends these previous studies, identifying for the first time an attenuation in forearm blood flow (Fig. 1A) and vascular conductance (Fig. 1C) during higher intensity handgrip exercise in individuals with HFpEF compared with overweight, hypertensive controls.

Interestingly, the decrements in blood flow and vascular conductance during handgrip exercise are strikingly similar to our previously published results using the same modality in individuals with HFrEF compared with healthy, age-matched controls (5). Indeed, while handgrip strength of both the individuals with HFrEF and the age-matched controls was greater in this previous study than that of the current participants (≈26 versus ≈19 kg, respectively), it is noteworthy that the 20–25% decrement in forearm blood flow in HF patients compared with HTN is remarkably similar between HFrEF (5) and HFpEF (Fig. 1A) subject groups. Thus, while these two heart failure phenotypes have unique etiologies and divergent central hemodynamic responses to exercise, the two appear to share a similar disease-related attenuation in hyperemia during handgrip exercise. Furthermore, it is worth noting that individuals with HTN are known to have an impaired hemodynamic responses to exercise (53), suggesting that the decrement in blood flow in individuals with HFpEF observed in the present study represents a greater magnitude of impairment than what is present as a consequence of HTN per se and is therefore unlikely to be attributable solely to the presence of this comorbidity in the HFpEF group.

Although it is tempting to conclude that an exercise-induced attenuation in skeletal muscle hyperemia represents a categorically maladaptive process, such an assumption would be an oversimplification of the complex processes of O2 transport and utilization that take place within the exercising muscle bed. Indeed, in view of the well-known matching of O2 delivery to the metabolic demands of the contracting skeletal muscle (66), it is possible that the observed attenuation in exercising muscle blood flow could be offset by an increase in O2 extraction, such that O2 utilization actually remained unchanged. However, Zamani et al. have recently identified an impaired brachial arterial to venous O2 difference during handgrip exercise in individuals with HFpEF compared with age-matched controls as well as individuals with HTN when matched for exercising blood flow rather than handgrip intensity (87). Likewise, Hearon et al. have recently observed a lengthening in oxygen kinetics at the onset of exercise among females with HFpEF compared with healthy age-matched females (32), which may, in part, be due to the observed diminished convective blood flow delivery in the current investigation. In conjunction with the current findings (Fig. 1A), these results suggest individuals with HFpEF may indeed have both an O2 delivery as well as O2 extraction impairment, strengthening the evidence that disease-related changes in peripheral vascular and metabolic function play a central role in the decline in exercise capacity in this patient population (60). Furthermore, at the microvascular level, it is now understood that significant heterogeneity in O2 delivery and utilization is present within skeletal muscle, and this heterogeneity is not always indicative of vascular dysfunction (34). Thus identifying where in the vascular tree there may be impairments and to what extent this contributes to the development of exercise intolerance in this patient group requires further study.

Obesity and hypertension are two of the most common comorbidities in HFpEF (55), and thus inclusion of a group with these characteristics provided the opportunity to more carefully discern the significance of our observed differences in exercise hyperemia between groups within the “constellation of comorbidities” (58) that accompany the HFpEF phenotype. However, it is worth noting that this approach also introduces additional complexities in data interpretation. Specifically, given the known influence of perfusion pressure on limb blood flow, the presence of elevated arterial blood pressure in the HTN group compared with patients with HFpEF (Fig. 1B) may have exaggerated the observed between-group differences in blood flow during handgrip exercise. Indeed, when responses are expressed as FVC, which mathematically corrects blood flow for arterial blood pressure, individuals with HFpEF differ from controls at only the highest (45% MVC) exercise intensity. While the magnitude of this decrement in FVC (∼20%) is less than that which is apparent for limb blood flow, it nonetheless supports some manner of impairment in the hyperemic response to moderate intensity handgrip exercise in individuals with HFpEF and is consistent with that previously reported during knee-extensor exercise in this patient group (44).

Central hemodynamic response to handgrip exercise.

This study employed small muscle mass exercise to afford the unique opportunity to evaluate the regulation of blood flow in the exercising muscle in relative isolation from disease-related changes in cardiac function. Such an experimental approach is particularly important when evaluating hemodynamic responses in patients with HFpEF, as chronotropic incompetence is a well-described feature of HFpEF pathophysiology. Indeed, during low-intensity (25 W) upright cycling, Borlaug et al. (11) reported a 40% attenuation in the exercise-induced increase in HR and CO in individuals with HFpEF compared with comorbidity-matched controls, highlighting the potential of disease-related impairments in cardiac autonomic function to affect exercise intolerance in this cohort. In the present study, a similar increase in HR and CO was observed during handgrip exercise between HTN and HFpEF groups (Table 4), supporting the concept that the observed decrement in forearm blood flow (Fig. 1A) and vascular conductance (Fig. 1C) during exercise is most likely not the consequence of chronotropic incompetence.

Given the similar changes in SV, SI, CO, and CI between groups (Table 4), the attenuation in exercising blood flow observed in individuals with HFpEF may be indicative of an impairment in the redistribution of blood flow from inactive tissue to the exercising muscle, a response that is crucial for adequate perfusion of exercising muscle during prolonged periods of exercise (69). While it is well beyond the scope of the present study to determine the exact mechanism(s) responsible for this potential maldistribution of blood flow during exercise in individuals with HFpEF, it is possible that disease-related changes in some aspect of neural control may play a role. Evidence supporting this possibility comes from studies in individuals with HFrEF, where the “muscle hypothesis” has been proposed to describe how abnormalities in sensory reflex activity in skeletal muscle might contribute to exercise limitations in this patient group (16). Indeed, there is now convincing evidence from both human and animal models of HFrEF for derangements in both mechanoreflex and metaboreflex sensitivity due to disease-related skeletal muscle myopathy (73), and recent data from our group have demonstrated that skeletal muscle afferent nerve activity contributes, importantly, to the regulation of blood flow during exercise in individuals with HFrEF (3). However, the degree to which autonomic reflexes may be altered in HFpEF, and whether this may contribute to inadequate redistribution of blood flow during exercise, have yet to be explored in this patient group (76) and therefore represent an intriguing area for further study.

Endothelium-dependent vasodilation during handgrip exercise.

The use of the handgrip exercise modality in this study afforded the opportunity to evaluate the stimulus-response relationship between graded increases in shear stress and the subsequent brachial artery vasodilation to further evaluate the potential for disease-related changes in endothelium-dependent vasodilation. While FMD is typically studied by evaluating the increase in conduit vessel diameter following a period of circulatory occlusion and tissue ischemia, this approach provides only a single data point and, although possible, would require a lengthy protocol to evaluate brachial artery vasodilation across a range of occlusion times and associated shear stimuli. Furthermore, while the magnitude of brachial artery FMD was previously thought to be predominantly NO mediated (37), this concept has recently been called into question (63, 85), further exemplifying the need for alternate approaches for the assessment of endothelial function. Our group (21, 46, 65, 78) and others (77) have developed the use of rhythmic handgrip exercise as an experimental model to expose the brachial artery to step-wise increases in shear stress, which results in progressive brachial artery vasodilation as exercise intensity increases. The “sustained stimulus flow-mediated vasodilation” (SS-FMD) (77) assessment has, thus, emerged as an alternative approach to traditional FMD testing and importantly, appears to be a largely NO-dependent process (84). Given the evidence suggesting that transient and sustained shear may be transduced differently across the endothelium (25) and recent work suggesting an increased sensitivity of SS-FMD over traditional FMD testing to detect endothelial dysfunction in patient groups (6, 29), the current study utilized the SS-FMD to further evaluate endothelial function in patients with HFpEF.

Across all exercise intensities, no differences in shear rate (Fig. 2A) or the associated change in brachial artery diameter (Fig. 2B) were evident between individuals with HTN and HFpEF. Furthermore, when this stimulus-response relationship was compared directly, there was no difference between the slope of the shear rate to brachial artery diameter assessments (Fig. 2C), further supporting the similarity of the response in the two groups. We have previously reported a very similar, 4–9% stepwise increase in brachial artery diameter during handgrip exercise of similar intensity in healthy, older individuals (78), further supporting a lack of overt conduit vessel dysfunction, as determined by SS-FMD, across the continuum from old age to the HFpEF clinical syndrome. This lack of obvious dysfunction at the level of the conduit artery is in agreement with previous studies reporting similar FMD values in both upper (31) and lower (35) limbs in individuals with HFpEF compared with old healthy individuals, although it is noteworthy that more recent studies have reported lower FMD values among individuals with HFpEF compared with healthy age-matched (39) or hypertensive (24, 47) individuals. These findings using the SS-FMD paradigm are also in agreement with recent work from our group reporting preserved conduit vascular function in individuals with HFpEF compared with healthy, age-matched controls, as described by FMD normalized for shear rate (43). Notably, in this previous study, a marked attenuation in reactive hyperemia was observed in the individuals with HFpEF, providing evidence of attenuated vascular function in the microvasculature, despite an apparent preservation of conduit artery function. The similar SS-FMD responses, viewed in conjunction with the observed attenuation in forearm blood flow (Fig. 1A) and vascular conductance (Fig. 1C) during exercise, confirm and extend this previous work (43), providing further evidence for a disease-related decline in vascular function at the level of the resistance vasculature, but not the conduit arteries, in individuals with HFpEF.

Experimental considerations.

There are several potential limitations in the present study. For the control group, we enrolled individuals with elevated BMI and hypertension, the most common comorbidities associated with HFpEF, and matched for handgrip MVC. However, we recognize that groups were not matched for age. Thus, while there is some evidence against an age-related decline in exercising muscle blood flow in the upper limbs (22, 61), we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed attenuation in both forearm blood flow and vascular conductance in individuals with HFpEF may be partially attributable to both chronologic age and disease status. Differences in age between groups also impacted menopausal status. Specifically, female participants in the HFpEF group were predominantly postmenopausal, while only half of the female participants in the HTN group were postmenopausal, raising the possibility that the absence or presence of sex hormones may have influenced results. While we recognize that HFpEF predominates among older female adults and may result in sex-specific differences (42), the current investigation was not properly powered to discern sex differences associated with exercising blood flow and endothelial function. By design, no prescribed medications were withheld on study days, which enabled the opportunity to study these patients in a “real‐world” setting. However, we cannot exclude the potential of this approach to influence the observed vascular responses, particularly given the known impact of targeted pharmacotherapies on FMD (2, 50). In the present study, we chose not to normalize limb blood flow for muscle mass, in part due to recent evidence from our group that failed to identify a significant relationship between muscle mass and limb blood flow during knee-extensor exercise (27), but we acknowledge that this approach may limit application of our findings in cohorts where large variations in limb volume are present. We also chose to focus on steady-state hemodynamics during handgrip exercise, which precludes investigation of potential differences in on- and off-kinetics of peripheral and central hemodynamics between groups. Finally, we recognize that the diagnostic criteria for Stage I hypertension utilized in the present study does not reflect more contemporary American Heart Association guidelines (80), which is attributable to a lengthy study enrollment period that predated this update in clinical classifications.

Conclusions.

This investigation has identified an attenuation in skeletal muscle blood flow and vascular conductance during dynamic handgrip exercise in individuals with HFpEF compared with individuals sharing two of the most common comorbidities associated with HFpEF, obesity and hypertension. Notably, this was despite the absence of disease-related changes in conduit vessel endothelial function.

GRANTS

This work was funded in part by American Heart Association Grant 14SDG18850039; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-118313 (to D.W.W.) and T32-HL-139451 (to R.S.R.); and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Grants I01RX001311 (to D.W.W.), I01RX001697 (to R.S.R.), I01RX002323 (to R.S.R.), I21RX001433 (to R.S.R.), I01RX000182 (to R.S.R.), and IK2RX001215 (to J.D.D.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.M.R., R.S.R., D.W.W., H.L.C., J.J.R., P.N.H., J.B.W., and J.D.T. conceived and designed research; S.M.R., D.W.W., H.L.C., D.L., R.M.B., J.F.L., and J.D.T. performed experiments; S.M.R., H.L.C., D.L., R.M.B., J.F.L., and J.D.T. analyzed data; S.M.R., R.S.R., D.W.W., R.M.B., J.J.R., P.N.H., and J.D.T. interpreted results of experiments; S.M.R. and D.W.W. prepared figures; S.M.R. drafted manuscript; S.M.R., R.S.R., D.W.W., H.L.C., D.L., R.M.B., J.F.L., J.J.R., P.N.H., J.B.W., and J.D.T. edited and revised manuscript; S.M.R., R.S.R., D.W.W., H.L.C., D.L., R.M.B., J.F.L., J.J.R., P.N.H., J.B.W., and J.D.T. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyama E, Sugiyama S, Matsuzawa Y, Konishi M, Suzuki H, Nozaki T, Ohba K, Matsubara J, Maeda H, Horibata Y, Sakamoto K, Sugamura K, Yamamuro M, Sumida H, Kaikita K, Iwashita S, Matsui K, Kimura K, Umemura S, Ogawa H. Incremental prognostic significance of peripheral endothelial dysfunction in patients with heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 1778–1786, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altun I, Oz F, Arkaya SC, Altun I, Bilge AK, Umman B, Turkoglu UM. Effect of statins on endothelial function in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a prospective study using adhesion molecules and flow-mediated dilatation. J Clin Med Res 6: 354–361, 2014. doi: 10.14740/jocmr1863w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann M, Venturelli M, Ives SJ, Morgan DE, Gmelch B, Witman MA, Jonathan Groot H, Walter Wray D, Stehlik J, Richardson RS. Group III/IV muscle afferents impair limb blood in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 174: 368–375, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen P, Saltin B. Maximal perfusion of skeletal muscle in man. J Physiol 366: 233–249, 1985. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett-O’Keefe Z, Lee JF, Berbert A, Witman MA, Nativi-Nicolau J, Stehlik J, Richardson RS, Wray DW. Hemodynamic responses to small muscle mass exercise in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1512–H1520, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00527.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellien J, Costentin A, Dutheil-Maillochaud B, Iacob M, Kuhn JM, Thuillez C, Joannides R. Early stage detection of conduit artery endothelial dysfunction in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res 7: 158–166, 2010. doi: 10.1177/1479164109360470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, Austin PC, Fang J, Haouzi A, Gong Y, Liu PP. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med 355: 260–269, 2006. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhella PS, Prasad A, Heinicke K, Hastings JL, Arbab-Zadeh A, Adams-Huet B, Pacini EL, Shibata S, Palmer MD, Newcomer BR, Levine BD. Abnormal haemodynamic response to exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 13: 1296–1304, 2011. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogert LW, van Lieshout JJ. Non-invasive pulsatile arterial pressure and stroke volume changes from the human finger. Exp Physiol 90: 437–446, 2005. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.030262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borlaug BA The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol 11: 507–515, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Russell SD, Kessler K, Pacak K, Becker LC, Kass DA. Impaired chronotropic and vasodilator reserves limit exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 114: 2138–2147, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CS, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 3: 588–595, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.930701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, Redfield MM. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 56: 845–854, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burkhoff D, Maurer MS, Packer M. Heart failure with a normal ejection fraction: is it really a disorder of diastolic function? Circulation 107: 656–658, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000053947.82595.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bursi F, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Pakhomov S, Nkomo VT, Meverden RA, Roger VL. Systolic and diastolic heart failure in the community. JAMA 296: 2209–2216, 2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.18.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coats AJ The “muscle hypothesis” of chronic heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 28: 2255–2262, 1996. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Vaal JB, de Wilde RB, van den Berg PC, Schreuder JJ, Jansen JR. Less invasive determination of cardiac output from the arterial pressure by aortic diameter-calibrated pulse contour. Br J Anaesth 95: 326–331, 2005. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Wilde RB, Geerts BF, Cui J, van den Berg PC, Jansen JR. Performance of three minimally invasive cardiac output monitoring systems. Anaesthesia 64: 762–769, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai AS, Lewis EF, Li R, Solomon SD, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Clausell N, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, McKinlay S, O’Meara E, Shaburishvili T, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA. Rationale and design of the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist trial: a randomized, controlled study of spironolactone in patients with symptomatic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am Heart J 162: 966–972.e10, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhakal BP, Malhotra R, Murphy RM, Pappagianopoulos PP, Baggish AL, Weiner RB, Houstis NE, Eisman AS, Hough SS, Lewis GD. Mechanisms of exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the role of abnormal peripheral oxygen extraction. Circ Heart Fail 8: 286–294, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Bailey DM, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: effects of antioxidants and exercise training in elderly men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H671–H678, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00761.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Wray DW, Nishiyama S, Lawrenson L, Richardson RS. Differential effects of aging on limb blood flow in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H272–H278, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00405.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunlay SM, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol 14: 591–602, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrero M, Blanco I, Batlle M, Santiago E, Cardona M, Vidal B, Castel MA, Sitges M, Barbera JA, Perez-Villa F. Pulmonary hypertension is related to peripheral endothelial dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 7: 791–798, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frangos JA, Huang TY, Clark CB. Steady shear and step changes in shear stimulate endothelium via independent mechanisms–superposition of transient and sustained nitric oxide production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 224: 660–665, 1996. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaggin HK, Januzzi JL Jr. Biomarkers and diagnostics in heart failure. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832: 2442–2450, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garten RS, Groot HJ, Rossman MJ, Gifford JR, Richardson RS. The role of muscle mass in exercise-induced hyperemia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 1204–1209, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00103.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 129: e28–e292, 2014. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grzelak P, Olszycki M, Majos A, Czupryniak L, Strzelczyk J, Stefańczyk L. Hand exercise test for the assessment of endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in subjects with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 12: 605–611, 2010. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haycock GB, Schwartz GJ, Wisotsky DH. Geometric method for measuring body surface area: a height-weight formula validated in infants, children, and adults. J Pediatr 93: 62–66, 1978. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(78)80601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haykowsky MJ, Herrington DM, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Hundley WG, Kitzman DW. Relationship of flow-mediated arterial dilation and exercise capacity in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68: 161–167, 2013. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hearon CM Jr, Sarma S, Dias KA, Hieda M, Levine BD. Impaired oxygen uptake kinetics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart 105: 1552–1558, 2019. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-314797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, Ikonomidis JS, Khavjou O, Konstam MA, Maddox TM, Nichol G, Pham M, Piña IL, Trogdon JG; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Stroke Council . Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 6: 606–619, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinonen I, Koga S, Kalliokoski KK, Musch TI, Poole DC. Heterogeneity of muscle blood flow and metabolism: influence of exercise, aging, and disease states. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 43: 117–124, 2015. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hundley WG, Bayram E, Hamilton CA, Hamilton EA, Morgan TM, Darty SN, Stewart KP, Link KM, Herrington DM, Kitzman DW. Leg flow-mediated arterial dilation in elderly patients with heart failure and normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1427–H1434, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00567.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Izawa KP, Watanabe S, Oka K, Hiraki K, Morio Y, Kasahara Y, Watanabe Y, Katata H, Osada N, Omiya K. Upper and lower extremity muscle strength levels associated with an exercise capacity of 5 metabolic equivalents in male patients with heart failure. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 32: 85–91, 2012. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31824bd886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joannides R, Haefeli WE, Linder L, Richard V, Bakkali EH, Thuillez C, Lüscher TF. Nitric oxide is responsible for flow-dependent dilatation of human peripheral conduit arteries in vivo. Circulation 91: 1314–1319, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.91.5.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaye DM, Silvestry FE, Gustafsson F, Cleland JG, van Veldhuisen DJ, Ponikowski P, Komtebedde J, Nanayakkara S, Burkhoff D, Shah SJ. Impact of atrial fibrillation on rest and exercise haemodynamics in heart failure with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 19: 1690–1697, 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kishimoto S, Kajikawa M, Maruhashi T, Iwamoto Y, Matsumoto T, Iwamoto A, Oda N, Matsui S, Hidaka T, Kihara Y, Chayama K, Goto C, Aibara Y, Nakashima A, Noma K, Higashi Y. Endothelial dysfunction and abnormal vascular structure are simultaneously present in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol 231: 181–187, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, Anderson RT, Hundley WG, Marburger CT, Brosnihan B, Morgan TM, Stewart KP. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA 288: 2144–2150, 2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kraigher-Krainer E, Shah AM, Gupta DK, Santos A, Claggett B, Pieske B, Zile MR, Voors AA, Lefkowitz MP, Packer M, McMurray JJ, Solomon SD, Investigators P; PARAMOUNT Investigators . Impaired systolic function by strain imaging in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 63: 447–456, 2014. [Erratum in J Am Coll Cardiol 64: 335, 2014]. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lam CS, Chandramouli C. Fat, female, fatigued: features of the obese HFpEF phenotype. JACC Heart Fail 6: 710–713, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JF, Barrett-O’Keefe Z, Garten RS, Nelson AD, Ryan JJ, Nativi JN, Richardson RS, Wray DW. Evidence of microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart 102: 278–284, 2016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JF, Barrett-O’Keefe Z, Nelson AD, Garten RS, Ryan JJ, Nativi-Nicolau JN, Richardson RS, Wray DW. Impaired skeletal muscle vasodilation during exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol 211: 14–21, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Logason K, Bärlin T, Jonsson ML, Boström A, Hårdemark HG, Karacagil S. The importance of Doppler angle of insonation on differentiation between 50-69% and 70-99% carotid artery stenosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 21: 311–313, 2001. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Machin DR, Clifton HL, Garten RS, Gifford JR, Richardson RS, Wray DW, Frech TM, Donato AJ. Exercise-induced brachial artery blood flow and vascular function is impaired in systemic sclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H1375–H1381, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00547.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maréchaux S, Samson R, van Belle E, Breyne J, de Monte J, Dédrie C, Chebai N, Menet A, Banfi C, Bouabdallaoui N, Le Jemtel TH, Ennezat PV. Vascular and microvascular endothelial function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Card Fail 22: 3–11, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA, Rosen B, Hay I, Ferruci L, Morell CH, Lakatta EG, Najjar SS, Kass DA. Cardiovascular features of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction versus nonfailing hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy in the urban Baltimore community: the role of atrial remodeling/dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 198–207, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mordi IR, Singh S, Rudd A, Srinivasan J, Frenneaux M, Tzemos N, Dawson DK. Comprehensive echocardiographic and cardiac magnetic resonance evaluation differentiates among heart failure with preserved ejection fraction patients, hypertensive patients, and healthy control subjects. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 11: 577–585, 2018. [Erratum in JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 12: 576, 2019]. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakamura T, Uematsu M, Yoshizaki T, Kobayashi T, Watanabe Y, Kugiyama K. Improvement of endothelial dysfunction is mediated through reduction of remnant lipoprotein after statin therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiol 75: 270–274, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newcomer SC, Leuenberger UA, Hogeman CS, Proctor DN. Heterogeneous vasodilator responses of human limbs: influence of age and habitual endurance training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H308–H315, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01151.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nishiyama SK, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Aging affects vascular structure and function in a limb-specific manner. J Appl Physiol (1985) 105: 1661–1670, 2008. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90612.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nyberg M, Jensen LG, Thaning P, Hellsten Y, Mortensen SP. Role of nitric oxide and prostanoids in the regulation of leg blood flow and blood pressure in humans with essential hypertension: effect of high-intensity aerobic training. J Physiol 590: 1481–1494, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Obokata M, Reddy YN, Pislaru SV, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA. Evidence supporting the existence of a distinct obese phenotype of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 136: 6–19, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 355: 251–259, 2006. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Padilla J, Johnson BD, Newcomer SC, Wilhite DP, Mickleborough TD, Fly AD, Mather KJ, Wallace JP. Normalization of flow-mediated dilation to shear stress area under the curve eliminates the impact of variable hyperemic stimulus. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 6: 44, 2008. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pandey A, Parashar A, Kumbhani D, Agarwal S, Garg J, Kitzman D, Levine B, Drazner M, Berry J. Exercise training in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Circ Heart Fail 8: 33–40, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 62: 263–271, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pawelczyk JA, Hanel B, Pawelczyk RA, Warberg J, Secher NH. Leg vasoconstriction during dynamic exercise with reduced cardiac output. J Appl Physiol (1985) 73: 1838–1846, 1992. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Poole DC, Behnke BJ, Musch TI. The role of vascular function on exercise capacity in health and disease. J Physiol. In press. doi: 10.1113/JP278931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Proctor DN, Parker BA. Vasodilation and vascular control in contracting muscle of the aging human. Microcirculation 13: 315–327, 2006. doi: 10.1080/10739680600618967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Puntawangkoon C, Kitzman DW, Kritchevsky SB, Hamilton CA, Nicklas B, Leng X, Brubaker PH, Hundley WG. Reduced peripheral arterial blood flow with preserved cardiac output during submaximal bicycle exercise in elderly heart failure. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 11: 48, 2009. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pyke K, Green DJ, Weisbrod C, Best M, Dembo L, O’Driscoll G, Tschakovsky M. Nitric oxide is not obligatory for radial artery flow-mediated dilation following release of 5 or 10 min distal occlusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H119–H126, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00571.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richardson RS Oxygen transport: air to muscle cell. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30: 53–59, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199801000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richardson RS, Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Wray DW, Lawrenson L, Nishiyama S, Bailey DM. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: role of free radicals. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1516–H1522, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Richardson RS, Harms CA, Grassi B, Hepple RT. Skeletal muscle: master or slave of the cardiovascular system? Med Sci Sports Exerc 32: 89–93, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Richardson RS, Saltin B. Human muscle blood flow and metabolism studied in the isolated quadriceps muscles. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30: 28–33, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richardson RS, Secher NH, Tschakovsky ME, Proctor DN, Wray DW. Metabolic and vascular limb differences affected by exercise, gender, age, and disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38: 1792–1796, 2006. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000229568.17284.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rowell LB Neural control of muscle blood flow: importance during dynamic exercise. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 24: 117–125, 1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saltin B Hemodynamic adaptations to exercise. Am J Cardiol 55: 42D–47D, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)91054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Secher NH, Clausen JP, Klausen K, Noer I, Trap-Jensen J. Central and regional circulatory effects of adding arm exercise to leg exercise. Acta Physiol Scand 100: 288–297, 1977. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb05952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh P, Vijayakumar S, Kalogeroupoulos A, Butler J. Multiple avenues of modulating the nitric oxide pathway in heart failure clinical trials. Curr Heart Fail Rep 15: 44–52, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11897-018-0383-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith SA, Mitchell JH, Garry MG. The mammalian exercise pressor reflex in health and disease. Exp Physiol 91: 89–102, 2006. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Solomon SD, Verma A, Desai A, Hassanein A, Izzo J, Oparil S, Lacourciere Y, Lee J, Seifu Y, Hilkert RJ, Rocha R, Pitt B; Exforge Intensive Control of Hypertension to Evaluate Efficacy in Diastolic Dysfunction Investigators . Effect of intensive versus standard blood pressure lowering on diastolic function in patients with uncontrolled hypertension and diastolic dysfunction. Hypertension 55: 241–248, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sugawara J, Tanabe T, Miyachi M, Yamamoto K, Takahashi K, Iemitsu M, Otsuki T, Homma S, Maeda S, Ajisaka R, Matsuda M. Non-invasive assessment of cardiac output during exercise in healthy young humans: comparison between Modelflow method and Doppler echocardiography method. Acta Physiol Scand 179: 361–366, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Toschi-Dias E, Rondon MU, Cogliati C, Paolocci N, Tobaldini E, Montano N. Contribution of Autonomic Reflexes to the Hyperadrenergic State in Heart Failure. Front Neurosci 11: 162, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tremblay JC, Pyke KE. Flow-mediated dilation stimulated by sustained increases in shear stress: a useful tool for assessing endothelial function in humans? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 314: H508–H520, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00534.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trinity JD, Wray DW, Witman MA, Layec G, Barrett-O’Keefe Z, Ives SJ, Conklin JD, Reese V, Richardson RS. Contribution of nitric oxide to brachial artery vasodilation during progressive handgrip exercise in the elderly. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R893–R899, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00311.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsioufis C, Georgiopoulos G, Oikonomou D, Thomopoulos C, Katsiki N, Kasiakogias A, Chrysochoou C, Konstantinidis D, Kalos T, Tousoulis D. Hypertension and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: connecting the dots. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 16: 15–22, 2017. doi: 10.2174/1570161115666170414120532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 71: 1269–1324, 2018. [Errata in Hypertension 71: e136–e139, 2018; Hypertension 72: e33, 2018]. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GY, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V, Desormais I; Authors/Task Force Members . 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens 36: 1953–2041, 2018. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wray DW, Richardson RS. Aging, exercise, and limb vascular heterogeneity in humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38: 1804–1810, 2006. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000230342.86870.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wray DW, Uberoi A, Lawrenson L, Richardson RS. Heterogeneous limb vascular responsiveness to shear stimuli during dynamic exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 99: 81–86, 2005. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01285.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wray DW, Witman MA, Ives SJ, McDaniel J, Fjeldstad AS, Trinity JD, Conklin JD, Supiano MA, Richardson RS. Progressive handgrip exercise: evidence of nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation and blood flow regulation in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1101–H1107, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01115.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wray DW, Witman MA, Ives SJ, McDaniel J, Trinity JD, Conklin JD, Supiano MA, Richardson RS. Does brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation provide a bioassay for NO? Hypertension 62: 345–351, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 128: 1810–1852, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zamani P, Proto EA, Mazurek JA, Prenner SB, Margulies KB, Townsend RR, Kelly DP, Arany Z, Poole DC, Wagner PD, Chirinos JA. Peripheral determinants of oxygen utilization in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: central role of adiposity. JACC Basic Transl Sci 5: 211–225, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part I: diagnosis, prognosis, and measurements of diastolic function. Circulation 105: 1387–1393, 2002. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zile MR, Gaasch WH, Carroll JD, Feldman MD, Aurigemma GP, Schaer GL, Ghali JK, Liebson PR. Heart failure with a normal ejection fraction: is measurement of diastolic function necessary to make the diagnosis of diastolic heart failure? Circulation 104: 779–782, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.094226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]