Abstract

The diaphragmatic motor-evoked potential (MEP) induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) permits electrophysiological assessment of the cortico-diaphragmatic pathway. Despite the value of TMS for investigating diaphragm motor integrity in health and disease, reliability of the technique has not been established. The study aim was to determine within- and between-session reproducibility of surface electromyogram recordings of TMS-evoked diaphragm potentials. Fifteen healthy young adults participated (6 females, age = 29 ± 7 yr). Diaphragm activation was determined by gradually increasing the stimulus intensity from 60 to 100% of maximal stimulator output (MSO). A minimum of seven stimulations were performed at each intensity. A second block of stimuli was delivered 30 min later for within-day comparisons, and a third block was performed on a separate day for between-day comparisons. Reliability of diaphragm MEPs was assessed at 100% MSO using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and 95% limits of agreement (LOA). MEP latency (ICC = 0.984, P < 0.001), duration (ICC = 0.958, P < 0.001), amplitude (ICC = 0.950, P < 0.001), and area (ICC = 0.956, P < 0.001) were highly reproducible within-day. Between-day reproducibility was good to excellent for all MEP characteristics (latency ICC = 0.953, P < 0.001; duration ICC = 0.879, P = 0.002; amplitude ICC = 0.789, P = 0.019; area ICC = 0.815, P = 0.012). Data revealed less precision between-day versus within-day, as evidenced by wider LOA for all MEP characteristics. Large within- and between-subject variability in MEP amplitude and area was observed. In conclusion, TMS is a reliable means of inducing diaphragm potentials in most healthy individuals.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive technique to assess neural impulse conduction along the cortico-diaphragmatic pathway. The reliability of diaphragm motor-evoked potentials (MEP) induced by TMS is unknown. Notwithstanding large variability in MEP amplitude, we found good-to-excellent reproducibility of all MEP characteristics (latency, duration, amplitude, and area) both within- and between-day in healthy adult men and women. Our findings support the use of TMS and surface EMG to assess diaphragm activation in humans.

Keywords: diaphragm, motor-evoked potential, phrenic, reliability, transcranial magnetic stimulation

INTRODUCTION

The phrenic nerves provide the sole somatic motor innervation to the diaphragm and are activated automatically (brainstem) and behaviorally (cortical) via bulbospinal and corticospinal pathways, respectively (2, 39). Ponto-medullary networks contain respiratory rhythm and pattern generators that are modulated by descending (e.g., sleep, emotion, learning/memory) and ascending (e.g., chemical and mechanical sensory feedback) neurogenic and humoral regulation (12). Behavioral influences arise from the primary motor cortex and premotor regions, allowing for voluntary control of respiration (16, 33). Integration of ponto-medullary and cortical signals to phrenic motor neurons in the cervical cord is known as reciprocal modulation and facilitates the demands of many functions, including alveolar ventilation (blood-gas homeostasis), phonation, swallowing, breath-holding, and airway clearance. Neural impulse conduction along the cortico-diaphragmatic pathway can be assessed quantitatively by inspection of the motor-evoked potential (MEP) induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (30, 34, 60).

Magnetic stimulation is based on the principle that a time-varying magnetic field will induce an electrical current in any conductive tissue through which it passes (Faraday’s principle) (21). Thus principles of electromagnetic induction enable noninvasive examination of electrophysiological features of neuromuscular systems. Foerster (15) demonstrated that the primary motor cortex of humans contains a small diaphragmatic representation that when stimulated electrically during neurosurgery, elicits diaphragm muscle contraction. Guided by these observations and technological advancements in TMS (4), Maskill and colleagues provided a framework for TMS studies of the phrenic motor system in conscious humans (34).

Researchers have since utilized TMS to evaluate changes in cortical (49) and corticospinal (41) excitability (i.e., respiratory motor plasticity), interactions between automatic and behavioral ventilatory drive (37, 53), the presence of exercise-induced diaphragmatic fatigue (56), and the impact of pathology on diaphragm neural control (14, 32). Latencies and amplitudes of diaphragm MEPs may elucidate central causes of diaphragm dysfunction (e.g., reduced amplitudes in stroke and prolonged latencies in multiple sclerosis). Despite the wide-array of TMS applications, recently published European Respiratory Society guidelines on respiratory muscle testing note that insufficient data exist concerning diaphragm MEP reproducibility (27), thereby limiting interpretation of phrenic nerve conduction studies; a comprehensive assessment of diaphragm MEP reliability is needed. To this end, the purpose of the present study was to establish within- and between-session reliability of diaphragm MEPs induced by TMS.

METHODS

Subjects.

Experimental procedures were conducted in the Health Science Center at the University of Florida and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Approval No. IRB201901170), which conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki. Fifteen healthy volunteers provided written informed consent to participate in the study (6 females, age = 29 ± 7 yr, body mass index = 26 ± 5 kg/m2). Subjects were excluded upon a history of pulmonary, cardiovascular or neurological illness, seizures, migraines and/or epilepsy, or metal implants of the upper body.

Experimental design.

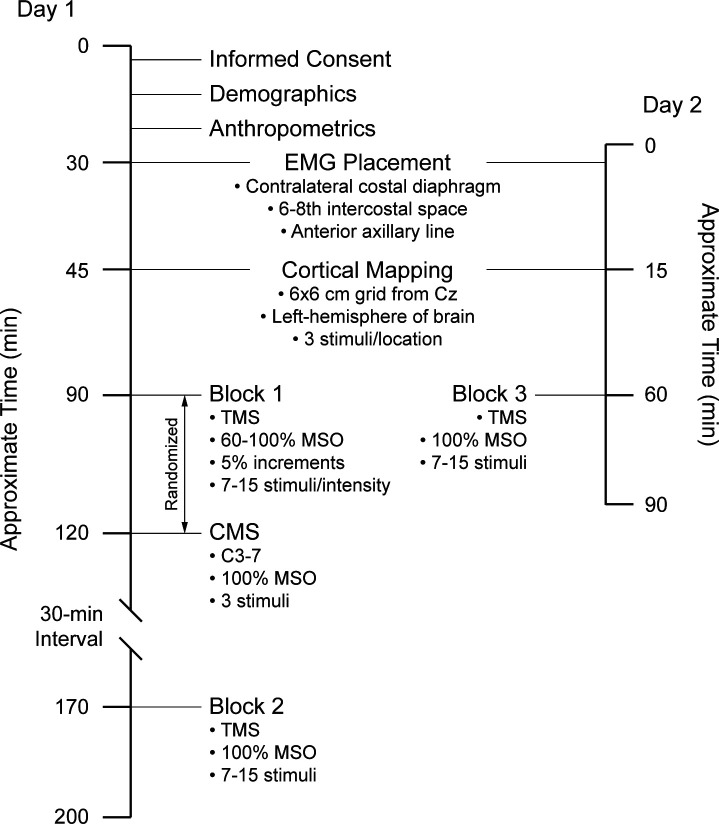

An overview of the experimental design is shown in Fig. 1. On day 1, participants completed a demographics questionnaire and anthropometrics were measured. After cortical mapping, two stimulation blocks were delivered 30 min apart to assess within-session reproducibility of diaphragm MEPs recorded by surface EMG. Peripheral nerve stimulation was performed before or after block 1 to obtain estimates of central motor conduction time. On day 2, 10 subjects returned to the laboratory (average = 6 ± 2 days later), where a third stimulation block was delivered for assessment of between-session reproducibility. Further details of study procedures follow.

Fig. 1.

Overview of experimental design. Three cortical stimulation blocks were performed. Two blocks of stimuli were delivered on day 1, separated by 30 min to assess within-session reliability. Cervical stimulations were delivered before or after block 1 to calculate central motor conduction times only. A 3rd block of stimuli was delivered on day 2 to assess between-session reliability. Evoked potentials were recorded using surface electrodes placed on the chest wall and a cortical mapping procedure was performed before stimulation blocks. TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; CMS, cervical magnetic stimulation; Cz, vertex; MSO, maximal stimulator output.

Magnetic stimulation.

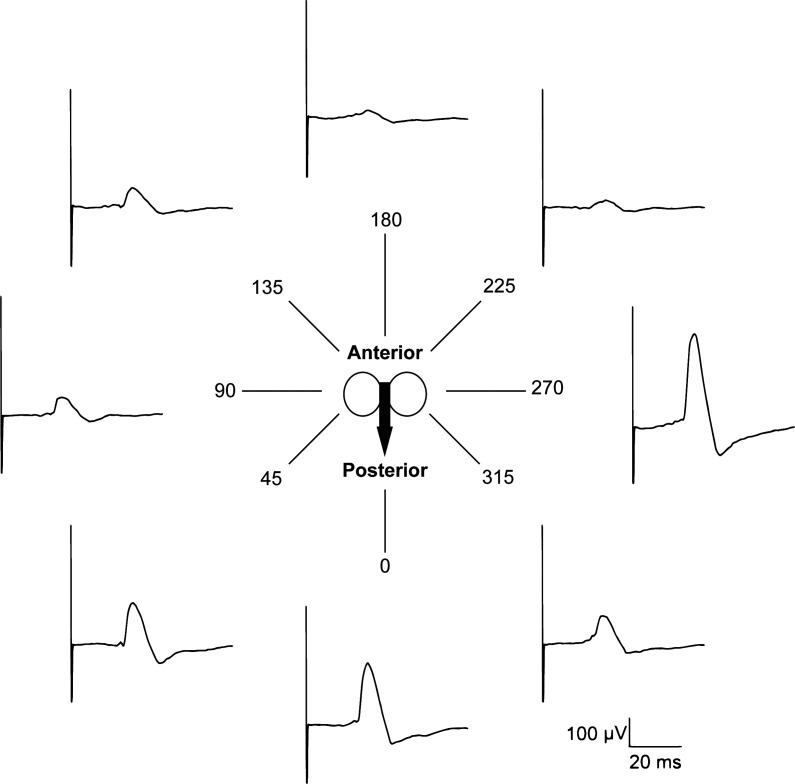

TMS was performed according to the methods described by Maskill et al. (34). The vertex (Cz, international 10–20 electroencephalogram electrode placement system) of the skull was identified by intersection between nasion to inion (sagittal plane) and tragus to tragus (coronal plane). Stimuli were delivered using a handheld 70-mm figure-of-eight coil (P/N 3190-00) powered by a magnetic stimulator (200-2, Magstim, Whitland, UK). The optimal coil position was identified for each individual by a cortical mapping procedure. This was achieved with the coil held tangentially over the left hemisphere of the brain with current flowing in the anteroposterior direction at 95% maximal stimulator output (MSO). The coil was moved from Cz in a grid-like fashion and rotated in 45° instalments until the largest MEP was observed (example shown in Fig. 2). This location was marked on a cloth treatment cap (MagVenture, Farum, Denmark) or directly on the scalp to ensure accurate coil positioning in future stimulations.

Fig. 2.

Example of cortical mapping. A figure-of-eight coil was used to elicit diaphragm motor-evoked potentials (MEP). Once the optimal stimulation site was identified, the coil was rotated in 45° instalments until the largest MEP was observed. Data shown are single raw evoked responses from 1 representative subject (S02).

Recruitment curves were plotted by gradually increasing the stimulus intensity from 60 to 100% MSO in 5% increments. Resting motor threshold was defined to the nearest 5% increment as the lowest stimulus intensity that elicited an evoked potential amplitude of ≥50 μV in three consecutive stimulations (45). The stimulation order was randomized to avoid any potential confounding influence of an incremental paradigm. A minimum of seven stimulations were delivered at each intensity separated by 20–30 s to prevent diaphragm potentiation. Stimuli were delivered at end-expiration, as determined using a piezoelectric respiration transducer (model 1132, Pneumotrace II, UFI, Morro Bay, CA) placed securely around the abdomen at the level of the umbilicus.

To further characterize cortico-diaphragmatic conduction, compound muscle action potentials were evoked by peripheral nerve stimulation [cervical magnetic stimulation (CMS)] using a 90-mm circular coil (P/N 9784-00) to estimate central motor conduction time only. Immediately before or after the first block of cortical stimulations, three stimuli were delivered at 100% MSO. Please see Welch, et al. (58) for further details of CMS procedures.

Electromyography.

Electrical activity of the contralateral costal diaphragm was recorded using self-adhesive surface Ag/AgCl electrodes (6801, The Prometheus Group, Dover, NH) placed on the chest wall in bipolar arrangement (∼3 cm apart) between the sixth and eighth intercostal spaces along the anterior-axillary line. The ground electrode was placed on the acromion process of the scapula. Skin was lightly abraded and cleaned before electrode placement. Surface recordings of diaphragm EMG in response to TMS have been previously validated (11), and the recording site has been shown to avoid major sources of signal contamination (57).

Data processing and analysis.

Signals were amplified and band-pass filtered (0.01–1 kHz; ML-132, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO), sampled at 10 kHz (PowerLab 8/35, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO), and monitored online using LabChart data acquisition software (version 8.1, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Evoked potentials were analyzed offline (MATLAB R2015a, MathWorks, Natick, MA) by an un-blinded investigator using a modified version of a previously detailed procedure (58). To objectively determine onset latency, EMG data were differentiated to generate an instantaneous slope profile and MEP onset was identified as the first data point when the EMG slope exceeded a mean ± 2 SD threshold (calculated over a 50-ms prestimulus window) and remained above this threshold for a minimum of 20 of the subsequent 30 data points. MEP offset was determined as the first data point of full wave-rectified (nondifferentiated) EMG that fell below the same threshold. MEP duration was calculated as the time difference between MEP onset and offset and peak-to-peak amplitude as the voltage difference between positive and negative EMG peaks. Integrated area (Eq. 1) was approximated from rectified EMG using the Riemann sum method (Eq. 2), where e = MEP offset time, o = MEP onset time, b = background noise, t = time, n = number of samples between o and e, i = index of summation, and Δt = sampling rate.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Central motor conduction time was calculated as the difference in onset latency between CMS- and TMS-evoked potentials. MEPs were excluded if the subject was not resting at functional residual capacity immediately preceding stimulation (visual inspection of abdominal displacements recorded by the respiration transducer).

Statistics.

Due to heteroscedasticity of residuals, a one-way repeated measures ANOVA (stimulation intensity) was used to determine maximal phrenic nerve activation by comparing log-10 transformed MEP amplitudes at all submaximal stimulation intensities with MSO. To assess reliability, coefficients of variation were calculated between subsequent stimuli within and between blocks, and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC[3,k]) were calculated for all dependent measures (MEP latency, duration, amplitude, and area) between blocks 1 and 2 for within-day comparisons and blocks 1 and 3 for between-day comparisons. Reliability was also assessed using absolute metrics derived from the limits of agreement (LOA) method originally described by Altman and Bland (1). SE was calculated as . Minimal detectable change was calculated as . Only stimulations delivered at 100% MSO were used for assessment of MEP reliability. Interpretation of ICCs were based on the model proposed by Koo and Li (26) and defined as: poor (ICC < 0.50), moderate (ICC = 0.50–0.75), good (ICC = 0.75–0.90), or excellent (ICC > 0.90). Significance was set at P < 0.05 for all statistical comparisons (SigmaPlot v12.5, Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA; and R v3.4.2, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Results are expressed as means ± SD, unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Cortical mapping.

The optimal stimulation site of cortical evoked diaphragm potentials was ∼1 cm anterior and 3 cm lateral to Cz with the coil held between 270 and 0° (individual data shown in Table 1). Evoked potentials were obtained in all subjects. An average of 174 stimuli were delivered per subject.

Table 1.

Individual data for cortical mapping

| Subject No. | Sagittal Plane, cm from Cz | Coronal Plane, cm from Cz | Angle, ° | No. of Stimulations | Estimated Time, min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S01 | +1 | 1 | 270 | 132 | 44 |

| S02 | 0 | 1 | 270 | 168 | 56 |

| S03 | +4 | 5 | 270 | 215 | 72 |

| S04 | +2 | 3 | 0 | 256 | 85 |

| S05 | 0 | 1 | 270 | 149 | 50 |

| S06 | 0 | 3 | 270 | 172 | 57 |

| S07 | +1 | 1 | 270 | 142 | 47 |

| S08 | 0 | 0 | 270 | 154 | 52 |

| S09 | 0 | 4 | 270 | 218 | 73 |

| S10 | +1 | 4 | 270 | 188 | 63 |

| S11 | 0 | 0 | 270 | 186 | 62 |

| S12 | +1 | 1 | 270 | 134 | 45 |

| S13 | 0 | 0 | 270 | 161 | 54 |

| S14 | +1 | 1 | 270 | 155 | 52 |

| S15 | 0 | 1 | 270 | 179 | 60 |

Cz, vertex.

MEP characteristics.

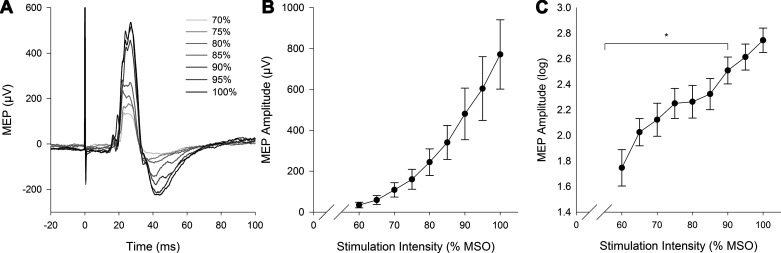

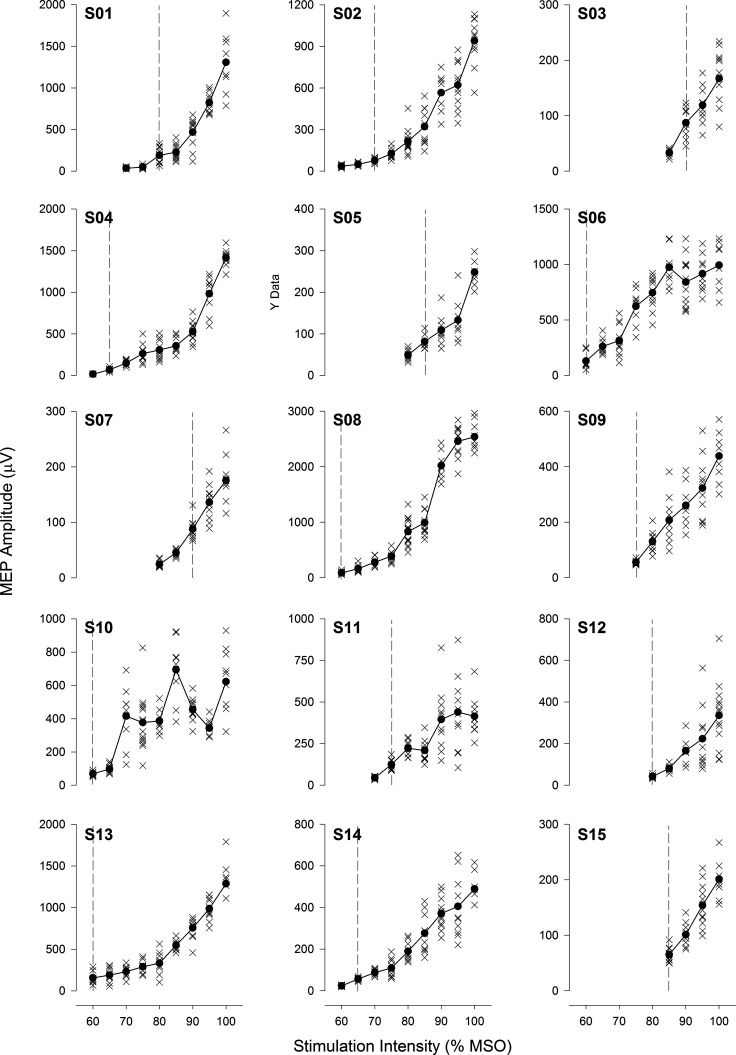

An exponential increase in MEP amplitude was observed across the stimulus response curve (Fig. 3). A main effect of stimulation intensity was found for MEP amplitude (P < 0.001), with no statistical difference between 95 and 100% MSO (P > 0.05). Individual stimulus response curves are shown in Fig. 4. On average, diaphragm resting motor threshold was 74% MSO (equal to 1.63 T). Central motor conduction time was 12.0 ± 2.7 ms. Full MEP characteristics (latency, duration, amplitude, and area) for blocks 1, 2, and 3 are provided in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Stimulus response curve. A: single raw evoked responses to increasing intensity of transcranial magnetic stimulation [gradient lines indicate stimuli delivered at varying intensities as a percent of the maximal stimulator output (MSO)] from 1 representative subject (S02). B: group means ± SE stimulus response curve for motor-evoked potential (MEP) amplitude. C: log-10 transformed MEP amplitudes. Statistical analyses were performed on log-10 transformed data due to heteroscedasticity. *Significant difference compared with 100% MSO (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Individual responses to transcranial magnetic stimulation. Individual stimulus response curves are presented for all 15 subjects (S1–S15). Vertical dashed gray line indicates stimulation intensity that evoked a response ≥50 μV in 3 or more consecutive stimulations (i.e., resting motor threshold). MEP, motor-evoked potential; MSO, maximal stimulator output.

Table 2.

Motor-evoked potential characteristics

| Variable |

Block 1 (n = 15) |

Block 2 (n = 15) |

Block 3 (n = 10) |

Within-Day (B1 and B2) |

Between-Day (B1 and B3) |

Range | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diff | % Delta | CV | SE | MDC | Diff | % Delta | CV | SE | MDC | ||||||

| Latency, ms | 17.2 ± 2.2 | 17.1 ± 2.5 | 17.5 ± 2.0 | −0.1 | −0.7 | 7.3 | 0.29 | 0.81 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 8.0 | 0.48 | 1.34 | 11.2–20.1 | |

| Duration, ms | 50.1 ± 8.0 | 49.2 ± 8.6 | 52.2 ± 6.4 | −0.9 | −1.7 | 13.0 | 1.67 | 4.62 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 15.7 | 2.68 | 7.42 | 35.3–68.8 | |

| Amplitude, μV | 772 ± 656 | 786 ± 566 | 691 ± 281 | 14.6 | 1.9 | 22.3 | 134 | 370 | −80.3 | −10.4 | 24.3 | 169 | 468 | 167–2540 | |

| Area, μV·ms | 6.3 ± 5.9 | 5.9 ± 5.6 | 5.5 ± 2.6 | −0.4 | −6.2 | 22.4 | 1.18 | 3.28 | −0.9 | −13.5 | 23.9 | 1.50 | 4.17 | 0.6–21.4 | |

CV, coefficient of variation; MDC, minimal detectable change.

Within- and between-session reliability.

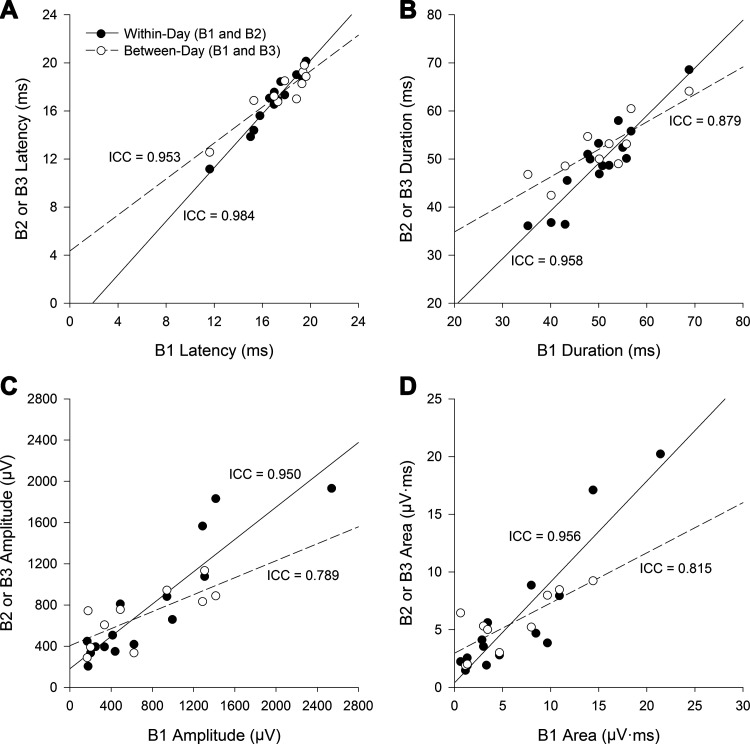

Within- and between-session reliability of diaphragm MEPs are shown in Fig. 5. Excellent reproducibility was observed for all MEP characteristics (latency ICC = 0.984, P < 0.001; duration ICC = 0.958, P < 0.001; amplitude ICC = 0.950, P < 0.001; area ICC = 0.956, P < 0.001) between blocks 1 and 2 (within-session comparisons). Between visits (blocks 1 and 3), temporal MEP characteristics demonstrated good to excellent reliability (latency ICC = 0.953, P < 0.001; duration ICC = 0.879, P = 0.002), while MEP amplitude (ICC = 0.789, P = 0.019) and area (ICC = 0.815, P = 0.012) demonstrated good reliability.

Fig. 5.

Reliability of diaphragmatic motor-evoked potentials. Scatter plot correlations for latency (A), duration (B), peak-to-peak amplitude (C), and total rectified area of evoked responses (D) to transcranial magnetic stimulation. Within-session data are shown by block 1 (B1) and block 2 (B2). Between-session data is shown by B1 and block 3 (B3). All data points are from stimuli delivered at 100% of the maximal stimulator output. ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

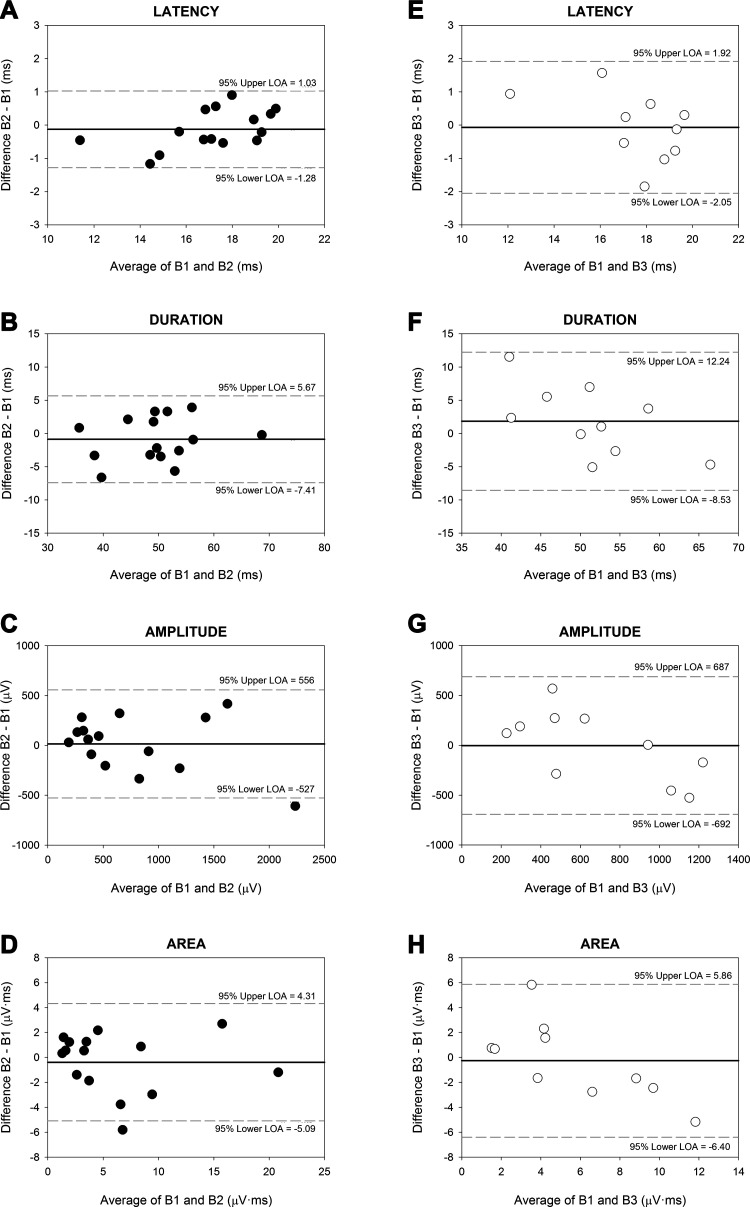

LOA for within- and between-day dependent variables are represented in Bland-Altman plots (Fig. 6). Greater data precision was found within-day compared with between-day, as evidenced by smaller upper and lower LOA for MEP latency (range = −1.28–1.03 vs. −2.05–1.92 ms), duration (range = −7.41–5.67 vs. −8.53–12.24 ms), amplitude (range = −527–556 vs. −692–687 μV), and area (range = −5.09–4.31 vs. −6.40–5.86 μV·ms).

Fig. 6.

Bland-Altman plots. Difference between means (y-axis) as a function of the average of 2 blocks of stimulations (x-axis). Within-day measures [blocks 1 (B1) and 2 (B2), filled black circles] are shown in A−D. Between-day measures [B1 and block 3 (B3), open white circles] are shown in E−H. Bias (the mean difference in values) is represented by the thick black horizontal line. The upper and lower 95% limits of agreement (LOA = mean bias ± 1.96 SD) are represented by thin gray horizontal dashed lines above and below the central bias line, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The diaphragmatic MEP provides important information regarding diaphragm neuromotor control; however, no data currently exist concerning methodological reliability. For the first time, we report diaphragm MEPs induced by TMS and recorded via surface EMG to be highly reproducible within a testing session and moderately reproducible between testing sessions conducted on separate days. Our findings support the use of TMS to assess cortico-diaphragmatic conduction in healthy humans.

Reproducibility and variability.

Test-retest reliability can be estimated using absolute (LOA) and relative (ICC) indexes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report within- and between-session reliability (absolute and relative) of diaphragm MEPs induced by TMS. We found all MEP characteristics to be highly reproducible within a testing session (ICC > 0.9). While no previous study has comprehensively examined the reliability of diaphragm MEPs, Sharshar et al. (49) reported no differences in the stimulus response curve between three separate blocks of stimuli performed on the same day, providing some evidence of within-session reproducibility. Our results compliment those of Sharshar, et al. (49) and add further insight into reliability of MEP characteristics within and between testing sessions.

Diaphragm potentials were reliably evoked between sessions performed on separate days (ICC >0.7); however, data revealed less precision versus within session, as indicated by wider LOA. Nevertheless, our ICC values for diaphragm MEPs are similar to those reported for swallowing musculature of the laryngopharynx (43) and other nonrespiratory muscles such as the tibialis anterior (54) and first dorsal interosseous (24). When these data are compared with the compound muscle action potential (or M-wave) evoked by peripheral nerve stimulation (i.e., CMS), diaphragm MEPs are less reliable and more variable (58). Critically, two subjects demonstrated a change in MEP amplitude above the minimal detectable change within and between sessions; therefore, in some individuals, diaphragm MEPs induced by TMS may not be considered reliable.

It is widely accepted that a high degree of variability in MEP amplitude exists under resting conditions for many skeletal muscles (13), even with careful control over stimulus timing, coil location, angulation, and stability (3). MEP amplitude is influenced by many factors, including stimulation intensity, accuracy of coil positioning, direction of current flow, adequacy of skin preparation, and underlying muscle activity. Some have reasoned that initial MEPs might be larger than subsequent evoked responses (6) and the increased variability may affect reliability (47). However, averaging a larger number of stimuli appears to be more effective in improving reliability than MEP removal (19). In our study, removing the first two MEPs from each stimulation block did not impact the ICC (data not shown). We performed a minimum of seven and maximum of 15 stimuli per intensity. Recent reports show an optimum of 20–30 stimulations to enhance reliability of TMS-evoked potentials (18); furthermore, neuro-navigation guidance systems allow greater coil precision (46). Thus reliability may have improved by performing a greater number of stimulations, in addition to the use of neuro-navigation.

Characteristics of the diaphragmatic MEP.

Our results confirm the originally held belief that the motor cortical representation of the diaphragm is within close proximity to the vertex of the skull. We found the optimal cortical stimulation site for diaphragm motor activation to be located ∼1 cm anterior and 3 cm lateral to Cz, with a coil orientation of 270° in the majority of subjects (see Table 1). In their seminal paper, Maskill et al. (34) examined the cortical motor representation of the diaphragm in humans using TMS. Directed by the observations of Foerster (15), the authors identified an optimal coil position of 2–3 cm anterior and 3 cm lateral to Cz, and future studies have substantiated this site (25, 48, 49). Typically, between 150 and 200 stimulations were performed during the cortical mapping procedure in the current study, which is less than the 350–400 stimulations reported by Maskill and colleagues (see Table 3 for comparative data).

Table 3.

Comparative data

| Author(s) | Sample Size (n) | Stimulation Parameters | Recording Parameters | Time of Stimulation | No. of Stimulations for Cortical Mapping | Approximate Time for Cortical Mapping | Recruitment Curves (Y/N) | Neuro-navigation (Y/N) | Sampling Frequency | MEP Amplitude Variability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 15 (6 F) 21–40 yr |

Coil: Figure-of-eight 70 mm (2.2 T) Location: 3 cm lateral, 1 cm anterior to Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 6–8th intercostal space, anterior axillary line |

End-expiration (respiration transducer) | 150–200 (95% MSO) |

58 min | Y (60–100% MSO) |

N | 10 kHz | 772 ± 656 μV |

| Spiesshoefer et al. 2019 (52) | 70 (45 F) 18–78 yr |

Coil: Circular 120 mm (2.0 T) Location: Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 7th intercostal space, costal margin |

End-expiration (expired flow) or inspiration (mouth pressure) | N/A | N/A | Y (60–100% MSO) |

N | N/A | 0.35 ± 0.29 mV |

| Niérat et al. 2014 (41) | 22 (13 F) 21–45 yr |

Coil: Double cone 90 mm Location: Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 8th intercostal space, anterior axillary line |

End-expiration (not defined) | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | 2 kHz | N/A |

| Laviolette et al. 2013 (28) | 12 (7 F) 25 ± 4 yr |

Coil: Double cone 90 mm or figure-of-eight 70 mm Location: Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 8th intercostal space, anterior axillary line |

End-expiration (respiration transducer) | N/A | N/A | N | Y | 10 kHz | 326 ± 160 μV |

| Mehiri et al. 2006 (37) | 5 (3 F) 25–35 yr |

Coil: Circular 90 mm (2.5 T) Location: Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 8th intercostal space, anterior axillary line |

End-expiration (diaphragm EMG and esophageal pressure) or inspiration (esophageal pressure) | N/A (100% MSO) |

N/A | N | N | 4 kHz | N/A |

| Straus et al. 2004 (53) | 13 (3 F) 22–35 yr |

Coil: Circular 90 mm (2.5 T) Location: Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 8th intercostal space, anterior axillary line |

Inspiration or expiration (esophageal pressure) | N/A (100% MSO) |

N/A | N | N | 10 kHz | N/A |

| Sharshar et al. 2004 (48) | 8 (3 F) 23–38 yr |

Coil: Double cone 110 mm Location: Cz (primary motor cortex) and 3 cm anterior to Cz (premotor cortex) |

Type: Surface and esophageal Location: Not defined |

End-expiration (esophageal and transdiaphragmatic pressure) | N/A (100% MSO) |

N/A | Y (40–100% MSO) |

N | N/A | 456 ± 462 μV |

| Sharshar et al. 2003 (49) | 10 (2 F) 29–69 yr |

Coil: Double cone 110 mm Location: Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 6–8th intercostal space |

End-expiration (esophageal pressure) | N/A (100% MSO) |

N/A | Y (40–100% MSO) |

N | 100 Hz | 333 ± 290 μV |

| Demoule et al. 2003 (11) | 9 (3 F) 24–39 yr |

Coil: Figure-of-eight 70 mm (2.0 T) or circular 90 mm (2.5 T) Location: 3 cm lateral, 2 cm anterior to Cz |

Various (surface and needle) | End-expiration (respiration transducer) | N/A (100% MSO) |

N/A | N | N | 10 kHz | N/A |

| Khedr et al. 2001 (25) | 30 (0 F) 18–64 yr |

Coil: Figure-of-eight 90 mm (1.5 T) Location: 4 cm lateral, 1 cm anterior to Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 6–7th intercostal space, anterior axillary line |

Inspiration (visual observation of abdominal displacement) | N/A | N/A | Y (60–100% MSO) |

N | N/A | 1064 ± 880 μV |

| Zifko et al. 1996 (60) | 35 (17 F) 20–76 yr |

Coil: Circular 90 mm (2.0 T) or figure-of-eight 70 mm (2.2 T) Location: Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 7th intercostal space, costal margin |

End of forceful inspiration (visual observation of abdominal displacement) | N/A (95% MSO) |

N/A | N | N | N/A | 269 ± 144 μV |

| Lissens 1994 (30) | 10 (5 F) 20–30 yr |

Coil: Circular 125 mm (2.5 T) Location: 2 cm anterior to C3/C4 (international EEG system) |

Type: Surface Location: Xiphoid process and lower border of ribcage at midclavicular line |

Maximal deep inspiration (not defined) | N/A (100% MSO) |

N/A | Y (40–100% MSO) |

N | N/A | 3.52 ± 2.40 mV |

| Maskill et al. 1991 (34) | 5 (0 F) 32–61 yr |

Coil: Figure-of-eight 90 mm (2.1 T) Location: 3 cm lateral, 2 cm anterior to Cz |

Type: Surface Location: 7–8th intercostal space, anterior axillary line |

Inspiration (integrated EMG activity) | 350–400 (90% MSO) |

120 min | N | N | N/A | N/A |

Comparison of results obtained from the current and previous studies in healthy humans reporting the following information: sample size, stimulation and recording parameters, estimated number of stimulations and time for cortical mapping, sampling frequency, motor-evoked potential (MEP) amplitude variability, and use of recruitment curves and neuro-navigation. Table is not a comprehensive summary of all transcranial magnetic stimulation studies. MSO, maximal stimulator output; Cz, vertex; F, female.

In contrast to some authors (28, 41, 48, 49), we were able to evoke a resting potential in all subjects using a figure-of-eight coil. Due to the small cortical diaphragmatic motor site and inherent limitations of magnetic stimulation, the double cone coil has been preferred in some instances (51). However, it is also acknowledged that this device is less focal and more painful at higher intensities (49) and therefore should only be used if the experimenter is unable to obtain a response with the figure-of-eight coil.

Congruent with previous literature, the latency of diaphragm MEPs were 17.2 ms with a central motor conduction time of 12.0 ms (25, 30, 41, 48, 49, 52). Latency provides some insight into the neural pathways activated by TMS. It is posited that TMS activates corticofugal neurons (corticospinal and corticobulbar) that synapse with spinal phrenic motor neurons innervating the diaphragm. Direct projections from the primary motor cortex (15) and supplemental motor areas (48) have been identified. However, as with previous studies (34), we cannot be certain whether the former or latter regions were activated by TMS; indeed, simultaneous coactivation of both motor areas may have occurred in some instances (e.g., S03 and S04, Table 1). The short latencies of diaphragm MEPs, combined with a central motor conduction time (motor cortex to spinal motor neurons), that is comparable to deltoid muscles (which innervates at the same spinal segments) (16) suggest a rapidly conducting mono- or oligosynaptic pathway that may bypass ponto-medullary respiratory control centers (44). Nonetheless, several lines of evidence signify an interaction between automatic and behavioral control systems.

For example, when a cat is conditioned to breathe to a tone (short inspiration, prolonged expiration), medullary inspiratory neurons are coupled to that behavioral task, particularly during apnea’s (42). These experiments indicate that “behavioral” control does involve cells normally considered part of the “automatic” system. Inhibition of brainstem inspiratory neurons during electrical cortical stimulation in cats (5), in addition to confirmation of active ponto-medullary networks (via magnetic resonance imaging) during voluntary hyperpnea in humans (35), is consistent with behavioral modulation of brainstem respiratory circuits. While we favor this viewpoint, available evidence does not support brainstem influences on TMS-evoked diaphragm potentials, exemplified by the absence of MEP amplitude depression during hypocapnia (a surrogate to suppress brainstem respiratory neuron activity) (9). Hence, diaphragm MEPs likely reflect the summation of descending corticospinal volleys that directly activate spinal phrenic motor neurons.

Our values of MEP amplitude (average = 772 μV) and variability (average = 22.3%), conform to published normative data (52). Due to the large variability between subjects, we observed no statistical difference in MEP amplitude between 95 and 100% MSO. Others have reported similar findings (30). The linear exponential shape of the stimulus response curve is also in line with previous work (48, 49). A sigmoid function, commonly achieved in other muscle groups (10, 55), is evidence of supramaximal stimulation and rarely observed for the diaphragm, possibly due to the distance between stimulating coil and cortical motor site (23). The large variability in evoked responses led to a minimal detectable change value that was 48% of the maximum MEP amplitude, which limits the use of TMS to detect small treatment effects.

Clinical applications.

The diaphragm is the primary inspiratory pump muscle, contributing significantly to convection of gas from the atmosphere to alveoli through the production of mechanical work (i.e., a change in pressure and volume of a system). Should the diaphragm fail, alveolar hypoventilation may ensue, leading to respiratory acidosis. TMS combined with surface EMG recordings of diaphragm potentials have considerable potential in the diagnosis, management, and treatment of diverse neurological disorders contributing to diaphragm dysfunction, including: stroke, Guillain-Barré syndrome, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and cervical spinal cord injury (50, 59). It is imperative therefore, that the method be adequately tested and reliability established.

Examination of diaphragm MEPs induced by TMS may be helpful in identifying patients suitable for phrenic nerve pacing, a promising substitute for positive pressure ventilation in those with cervical lesions (31). Because MEP latency is reproducible with low variability when analyzed objectively, it can be used to monitor disease-related changes in diaphragm activation. Conversely, MEP amplitude demonstrates significant variability between subsequent stimuli within and between sessions, notwithstanding good reliability; therefore, changes over time must be interpreted carefully. The diaphragm MEP may also be used to assess supraspinal contributions to muscle fatigue. Specifically, a reduction in MEP amplitude is observed following repetitive muscle activation to task failure (7), indicative of impaired cortical motor drive. It has recently been demonstrated that activation of spinal central pattern generators can reset respiratory rhythm in paralyzed cats, implying an interaction between spinal and brainstem oscillators via descending cortical commands (38): TMS may shed light on this purported mechanism in humans.

Technical considerations.

A fundamental limitation of TMS in the present study is the inability to guarantee maximal activation of the phrenic nerve and unavoidable stimulation of nondiaphragmatic muscles. Steps were taken to reduce contamination from nondiaphragmatic muscles to the surface EMG. For instance, thorough cortical mapping procedures were performed on each subject and electrodes were placed at more medial, anterior and lower sites to avoid the major sources of cross talk, such as latissimus dorsi, serratus anterior, and pectoralis major. Furthermore, interelectrode distance was kept to a minimum, thereby abating the influence of electrical activity from nearby muscles. Although we cannot guarantee a “pure” diaphragmatic signal, several pieces of evidence support the validity of our recording site. First, latencies are within normal limits based on phrenic nerve length (22, 36) and conduction velocity (10a, 20) and do not differ from needle diaphragmatic EMG recordings (11). Second, no differences in evoked responses (latency and amplitude) are observed between surface and esophageal EMG using cortical stimulation (17). Third, surface recordings correlate well with esophageal-derived measures of neural respiratory drive (29). Fourth, activity is absent in those with phrenic nerve palsy (8).

Reliability assessments were performed exclusively at 100% MSO. Therefore, stimuli were delivered at different fractions of each individuals resting motor threshold, which may limit generalizability of our findings. A final limitation of the present study is the lack of precise coil control with respect to individual cortical anatomy. Previous investigations have implemented computer-assisted neuro-navigation techniques to improve coil accuracy (46). Such systems may reduce variability between subsequent stimuli and improve methodological reliability.

In conclusion, our findings support the use of TMS and chest wall surface EMG to assess diaphragm neural activation. TMS is an effective and reliable means of inducing diaphragmatic MEPs in healthy humans within and between testing sessions. Within a testing session, TMS yields highly reproducible results between stimulus blocks for all MEP characteristics. Caution should be taken with comparisons between testing sessions conducted on separate days (particularly MEP amplitude and area) since MEPs are variable and demonstrate weaker, albeit good reproducibility. It is hoped that this analysis will inform future studies and extend consistent methodological standards across laboratories.

GRANTS

The study was supported by University of Florida (UF) McKnight Brain Institute; Craig H. Neilsen Foundation; U.S. Department of Defense (SCIRP); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-147554; Brooks Rehabilitation; and Brooks/UF-College of Public Health and Health Professions (PHHP) Research Collaboration.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.F.W. conceived and designed research; J.F.W. and P.J.A. performed experiments; J.F.W. analyzed data; J.F.W., G.S.M., and E.J.F. interpreted results of experiments; J.F.W. prepared figures; J.F.W. drafted manuscript; J.F.W., P.J.A., G.S.M., and E.J.F. edited and revised manuscript; J.F.W., P.J.A., G.S.M., and E.J.F. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Professors Paul Davenport (University of Florida) and Thomas Similowski (Sorbonne Université) and Dr. Marie-Cécile Niérat (Sorbonne Université) for discussions of study procedures. We also thank Dr. Raphael Perim (University of Florida) for consultation of statistical analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman DG, Bland JM. Measurement in medicine: the analysis of method comparison studies. Statistician 32: 307–317, 1983. doi: 10.2307/2987937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aminoff MJ, Sears TA. Spinal integration of segmental, cortical and breathing inputs to thoracic respiratory motoneurones. J Physiol 215: 557–575, 1971. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker AT, Freeston IL, Jalinous R, Jarratt JA. Magnetic stimulation of the human brain and peripheral nervous system: an introduction and the results of an initial clinical evaluation. Neurosurgery 20: 100–109, 1987. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198701000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker AT, Jalinous R, Freeston IL. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex. Lancet 325: 1106–1107, 1985. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bassal M, Bianchi AL. Effets de la stimulation des structures nerveuses centrales sur les activites respiratoires efferentes chez le chat. J Physiol (Paris) 77: 741–757, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasil-Neto JP, Cohen LG, Hallett M. Central fatigue as revealed by postexercise decrement of motor evoked potentials. Muscle Nerve 17: 713–719, 1994. doi: 10.1002/mus.880170702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brasil-Neto JP, Pascual-Leone A, Valls-Solé J, Cammarota A, Cohen LG, Hallett M. Postexercise depression of motor evoked potentials: a measure of central nervous system fatigue. Exp Brain Res 93: 181–184, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF00227794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chokroverty S, Shah S, Chokroverty M, Deutsch A, Belsh J. Percutaneous magnetic coil stimulation of the phrenic nerve roots and trunk. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 97: 369–374, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0924-980X(95)00159-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corfield DR, Murphy K, Guz A. Does the motor cortical control of the diaphragm ‘bypass’ the brain stem respiratory centres in man? Respir Physiol 114: 109–117, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5687(98)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darling WG, Wolf SL, Butler AJ. Variability of motor potentials evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation depends on muscle activation. Exp Brain Res 174: 376–385, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Davis JN Phrenic nerve conduction in man. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 30: 420–426, 1967. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.30.5.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demoule A, Verin E, Locher C, Derenne JP, Similowski T. Validation of surface recordings of the diaphragm response to transcranial magnetic stimulation in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 94: 453–461, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00581.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dempsey JA, Vidruk EH, Mitchell GS. Pulmonary control systems in exercise: update. Fed Proc 44: 2260–2270, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellaway PH, Davey NJ, Maskill DW, Rawlinson SR, Lewis HS, Anissimova NP. Variability in the amplitude of skeletal muscle responses to magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 109: 104–113, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0924-980X(98)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elnemr R, Sweed RA, Shafiek H. Diaphragmatic motor cortex hyperexcitability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 14: e0217886, 2019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foerster O Motorische Felder und Bahen In Handbook der Neurologie, edited by Bumke O, Foerster O. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 1936, p. 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandevia SC, Rothwell JC. Activation of the human diaphragm from the motor cortex. J Physiol 384: 109–118, 1987. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gea J, Espadaler JM, Guiu R, Aran X, Seoane L, Broquetas JM. Diaphragmatic activity induced by cortical stimulation: surface versus esophageal electrodes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 74: 655–658, 1993. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.2.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldsworthy MR, Hordacre B, Ridding MC. Minimum number of trials required for within- and between-session reliability of TMS measures of corticospinal excitability. Neuroscience 320: 205–209, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashemirad F, Zoghi M, Fitzgerald PB, Jaberzadeh S. Reliability of motor evoked potentials induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation: the effects of initial motor evoked potentials removal. Basic Clin Neurosci 8: 43–50, 2017. doi: 10.15412/J.BCN.03080106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinbecker P, Bishop GH, O’Leary JL. Functional and histological studies of somatic and autonomic nerves of man. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 35: 1233–1255, 1936. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1936.02260060075007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ilmoniemi RJ, Ruohonen J, Karhu J. Transcranial magnetic stimulation--a new tool for functional imaging of the brain. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 27: 241–284, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang S, Xu WD, Shen YD, Xu JG, Gu YD. An anatomical study of the full-length phrenic nerve and its blood supply: clinical implications for endoscopic dissection. Anat Sci Int 86: 225–231, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s12565-011-0114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julkunen P, Säisänen L, Danner N, Awiszus F, Könönen M. Within-subject effect of coil-to-cortex distance on cortical electric field threshold and motor evoked potentials in transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neurosci Methods 206: 158–164, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamen G Reliability of motor-evoked potentials during resting and active contraction conditions. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36: 1574–1579, 2004. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000139804.02576.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khedr EM, Trakhan MN. Localization of diaphragm motor cortical representation and determination of corticodiaphragmatic latencies by using magnetic stimulation in normal adult human subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol 85: 560–566, 2001. doi: 10.1007/s004210100504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med 15: 155–163, 2016. [Erratum in J Chiropr Med 16: 346, 2016]. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laveneziana P, Albuquerque A, Aliverti A, Babb T, Barreiro E, Dres M, Dubé BP, Fauroux B, Gea J, Guenette JA, Hudson AL, Kabitz HJ, Laghi F, Langer D, Luo YM, Neder JA, O’Donnell D, Polkey MI, Rabinovich RA, Rossi A, Series F, Similowski T, Spengler CM, Vogiatzis I, Verges S. ERS statement on respiratory muscle testing at rest and during exercise. Eur Respir J 53: 1801214, 2019. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01214-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laviolette L, Niérat MC, Hudson AL, Raux M, Allard E, Similowski T. The supplementary motor area exerts a tonic excitatory influence on corticospinal projections to phrenic motoneurons in awake humans. PLoS One 8: e62258, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin L, Guan L, Wu W, Chen R. Correlation of surface respiratory electromyography with esophageal diaphragm electromyography. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 259: 45–52, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lissens MA Motor evoked potentials of the human diaphragm elicited through magnetic transcranial brain stimulation. J Neurol Sci 124: 204–207, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(94)90327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lissens MA, Vanderstraeten GG. Motor evoked potentials of the respiratory muscles in tetraplegic patients. Spinal Cord 34: 673–678, 1996. doi: 10.1038/sc.1996.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locher C, Raux M, Fiamma MN, Morélot-Panzini C, Zelter M, Derenne JP, Similowski T, Straus C. Inspiratory resistances facilitate the diaphragm response to transcranial stimulation in humans. BMC Physiol 6: 7, 2006. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macefield G, Gandevia SC. The cortical drive to human respiratory muscles in the awake state assessed by premotor cerebral potentials. J Physiol 439: 545–558, 1991. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maskill D, Murphy K, Mier A, Owen M, Guz A. Motor cortical representation of the diaphragm in man. J Physiol 443: 105–121, 1991. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKay LC, Evans KC, Frackowiak RSJ, Corfield DR. Neural correlates of voluntary breathing in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 95: 1170–1178, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00641.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKenzie DK, Gandevia SC. Phrenic nerve conduction times and twitch pressures of the human diaphragm. J Appl Physiol (1985) 58: 1496–1504, 1985. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.5.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehiri S, Straus C, Arnulf I, Attali V, Zelter M, Derenne JP, Similowski T. Responses of the diaphragm to transcranial magnetic stimulation during wake and sleep in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 154: 406–418, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meza R, Huidobro N, Moreno-Castillo M, Mendez-Fernandez A, Flores-Hernandez J, Flores A, Manjarrez E. Resetting the respiratory rhythm with a spinal central pattern generator. eNeuro 6: ENEURO.0116-19.2019, 2019. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0116-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nathan PW The descending respiratory pathway in man. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 26: 487–499, 1963. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.26.6.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niérat MC, Similowski T, Lamy JC. Does trans-spinal direct current stimulation alter phrenic motoneurons and respiratory neuromechanical outputs in humans? A double-blind, sham-controlled, randomized, crossover study. J Neurosci 34: 14420–14429, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1288-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orem J, Netick A. Behavioral control of breathing in the cat. Brain Res 366: 238–253, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plowman-Prine EK, Triggs WJ, Malcolm MP, Rosenbek JC. Reliability of transcranial magnetic stimulation for mapping swallowing musculature in the human motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol 119: 2298–2303, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rikard-Bell GC, Bystrzycka EK, Nail BS. The identification of brainstem neurones projecting to thoracic respiratory motoneurones in the cat as demonstrated by retrograde transport of HRP. Brain Res Bull 14: 25–37, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(85)90174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossini PM, Barker AT, Berardelli A, Caramia MD, Caruso G, Cracco RQ, Dimitrijević MR, Hallett M, Katayama Y, Lücking CH, Maertens de Noordhout AL, Marsden CD, Murray NM, Rothwell JC, Swash M, Tomberg C. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application. Report of an IFCN committee. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 91: 79–92, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruohonen J, Karhu J. Navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurophysiol Clin 40: 7–17, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt S, Cichy RM, Kraft A, Brocke J, Irlbacher K, Brandt SA. An initial transient-state and reliable measures of corticospinal excitability in TMS studies. Clin Neurophysiol 120: 987–993, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.02.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharshar T, Hopkinson NS, Jonville S, Prigent H, Carlier R, Dayer MJ, Swallow EB, Lofaso F, Moxham J, Polkey MI. Demonstration of a second rapidly conducting cortico-diaphragmatic pathway in humans. J Physiol 560: 897–908, 2004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharshar T, Ross E, Hopkinson NS, Dayer M, Nickol A, Lofaso F, Moxham J, Similowski T, Polkey MI. Effect of voluntary facilitation on the diaphragmatic response to transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 95: 26–34, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00918.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Similowski T, Mehiri S, Duguet A, Attali V, Straus C, Derenne JP. Comparison of magnetic and electrical phrenic nerve stimulation in assessment of phrenic nerve conduction time. J Appl Physiol (1985) 82: 1190–1199, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.4.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Similowski T, Straus C, Coïc L, Derenne JP. Facilitation-independent response of the diaphragm to cortical magnetic stimulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 154: 1771–1777, 1996. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spiesshoefer J, Henke C, Herkenrath S, Randerath W, Schneppe M, Young P, Brix T, Boentert M. Electrophysiological properties of the human diaphragm assessed by magnetic phrenic nerve stimulation: normal values and theoretical considerations in healthy adults. J Clin Neurophysiol 36: 375–384, 2019. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Straus C, Locher C, Zelter M, Derenne JP, Similowski T. Facilitation of the diaphragm response to transcranial magnetic stimulation by increases in human respiratory drive. J Appl Physiol (1985) 97: 902–912, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00989.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Hedel HJ, Murer C, Dietz V, Curt A. The amplitude of lower leg motor evoked potentials is a reliable measure when controlled for torque and motor task. J Neurol 254: 1089–1098, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Kuijk AA, Anker LC, Pasman JW, Hendriks JCM, van Elswijk G, Geurts ACH. Stimulus-response characteristics of motor evoked potentials and silent periods in proximal and distal upper-extremity muscles. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 19: 574–583, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verin E, Ross E, Demoule A, Hopkinson N, Nickol A, Fauroux B, Moxham J, Similowski T, Polkey MI. Effects of exhaustive incremental treadmill exercise on diaphragm and quadriceps motor potentials evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 96: 253–259, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00325.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verin E, Straus C, Demoule A, Mialon P, Derenne JP, Similowski T. Validation of improved recording site to measure phrenic conduction from surface electrodes in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 92: 967–974, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00652.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Welch JF, Mildren RL, Zaback M, Archiza B, Allen GP, Sheel AW. Reliability of the diaphragmatic compound muscle action potential evoked by cervical magnetic stimulation and recorded via chest wall surface EMG. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 243: 101–106, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zifko U, Chen R, Remtulla H, Hahn AF, Koopman W, Bolton CF. Respiratory electrophysiological studies in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 60: 191–194, 1996. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.60.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zifko U, Remtulla H, Power K, Bolton CF, Harker L. Transcortical and cervical magnetic stimulation with recording of the diaphragm. Muscle Nerve 19: 614–620, 1996. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]