Abstract

Background:

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder in fertile women, which seems to be adversely affected by associated thyroid dysfunction. Zinc methionine (ZM) has positive effects on PCOS, but its concerted effects on PCOS and thyroid function have not been investigated. We evaluated the effects of ZM on reproductive and thyroid hormones and the number of follicles in rats with PCOS.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted on 45 female rats, using sesame oil as control; PCOS animals administered with 0, 25, 75, and 175 mg/kg BW of ZM. Serum concentrations of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and thyroid function were investigated. Premature follicles (PMF), primary follicles (PF), preantral follicles (PAF), antral follicles (AF), corpus luteum (CL), and cystic follicles (CF) were assessed.

Results:

PCOS decreased the concentrations of FSH and free T4, but increased the levels of LH, TSH, and LH/FSH ratio (ALL P < 0.05). ZM at a dose of 75 and 175 mg increased the level of FSH, free T4, and decreased LH, TSH, and LH/FSH ratio (ALL P < 0.05). Induction of PCOS decreased PMF, PF, PAF, AF, and CL, but increased CF (P < 0.05). PCOS treated groups (75 and 175 mg/kg) increased these follicle numbers and decreased CF compared to ZM 25 mg/kg and PCOS groups (Both P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Although the induction of PCOS had a negative effect on reproductive and thyroid hormones and follicle numbers, ZM treatment (75 and 175 mg/kg) overcame the negative effects. A high dosage of ZM can alleviate the hormonal and cysts disturbances occurring in PCOS.

Keywords: Follicle stimulating hormone, hormones, ovarian follicle, polycystic ovarian syndrome, rats, thyroid hormones, zinc methionine

Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder in fertile women, which causes different reproductive abnormalities, such as ovulatory infertility, menstrual dysfunction, and hirsutism.[1] PCOS is commonly associated with an increased risk of metabolic abnormalities, such as obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and dyslipidemia.[2] It also seems to be adversely affected by the associated thyroid dysfunction.[3] The concentrations of adrenal androgens have been reported to be significantly higher in women with PCOS.[4] Hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis regulates the network responsible for reproductive competence and the survival of the species. PCOS is characterized by androgen excess, ovulatory dysfunction, and disruptions in the HPO axis function.[5] PCOS induces persistent hyper-androgenism that results in the faulted hypothalamic–pituitary feedback, luteinizing hormone (LH) hypersecretion, premature granulosa cell luteinization, aberrant oocyte maturation, and the premature arrest of activated primary follicles.[6] Jiayu et al. showed that PCOS increases luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone (LH/FSH) ratios.[7] In addition to the reproductive system, hypothyroidism is also observed in PCOS patients.[8] Shirsath et al. found that the hypothyroidism can lead to a reduction in sex hormone-binding globulin and an increase in free testosterone. Free testosterone is one of the factors contributing to PCOS symptoms.[9] PCOS women express hypothyroidism due to the insufficient secretion of thyroid hormone resulting from dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary ovarian axis.[8,10,11] Some strategies, such as nutritional strategy, are used for decreasing the adverse effects of PCOS.

Zinc (Zn) is an essential element in the reproductive system, which is associated with several regulating factors that regulate the metabolic activities in the body.[12] Zinc may have insignificant absorption and need carriers to increase absorption and bioavailability.[13] Recently, the concept of organic minerals has appeared in which mineral is in a chemically inert form, more stable and less prone to mineral and nutrient interactions, so absorbed and circulated to target tissues very efficiently.[14] Zn methionine (Zn-Met) is an organic source of Zn with methionine (amino acid) as the ligand. This is an easily absorbed resource that simply provides the bioavailability of zinc.[15] From the chemical point of view, the coordination form of the methionine to zinc is very clear in the literature,[16] with donor sites NH2 and COO-participating in the metal coordination. It was believed that the serum concentration of Zn might be decreased in PCOS patients.[17] Zinc deficiency might have a major role in the pathogenesis of PCOS due to its long-term metabolic consequences.[17] Zinc is an essential element for the production of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), which has an important role in binding T3 to its nuclear receptor. It is also imperative in the synthesis of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in the anterior pituitary, acting as a preventer or cofactor of type 1 and type 2 deiodinases.[18] Many organic sources of Zn are available; their efficiency has been tested in many livestock species in terms of growth, immunity, and reproduction.[14] Zn-Met had greater bioavailability than traditional zinc sources in some situations and appear to induce a faster growth and a better resistance to various diseases in comparison with simple inorganic salts.[15] Despite the positive effects of zinc on the reproductive and thyroid hormones, there have no studies to evaluate its beneficial effects in the organic source on both PCOS and thyroid function. Therefore, the present study was conducted to assess the effects of zinc methionine (ZM) as an organic source,on reproductive and thyroid hormones and follicle numbers in Sprague Dawley rats induced by estradiol valerate (EV).

Materials and Methods

Materials

ZM and EV were prepared from Zinpro Corporation, (Eden Prairie, MN 55344 USA) and (Aburaihan Co. Tehran, Iran), respectively. LH and FSH were assessed by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and commercial kits (Cloud-Clone Corp., Houston, TX, USA) under the protocols of kit manufacturers.

Animal

This study was conducted based on the Animal Research Committee Guidelines of Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). Female rats (Rattus norvegicus. Sprague Dawley), with three consecutive regular periods of the estrous cycle and body weight of 145 ± 5 g were prepared from the Pasteur Institute of Tehran, Iran. The rats were grouped in polycarbonate cages with paddy husk bedding, at a temperature of 22°C ± 3°C and a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle and had free access to water and feed. A 14-day period was considered as the adaption period. A 57-day period was considered, including 14 days adaption, 28 days induction of PCOS, and 15 days for the treatment with ZM.[12]

Experimental treatments

This study was conducted on 45 female rats that were weighted after adaptation and divided randomly into five groups (n = 9), as follows: Control group (1) Healthy rats that received the standard diet and were daily administrated by 0.4 ml of sesame oil through intraperitoneal route (control), (2) PCOS group in which animals were administrated with EV (4 mg EV in 0.4 ml sesame oil/rat) for 28 days through subcutaneous injection (PCOS), (3) PCOS + Zn Met groups that the animals were administrated with 25, 75, and 175 mg/kg BW pure zinc in the form of ZM through oral route, respectively (PCOS + Zn Met 25, PCOS + Zn Met 75 and PCOS + Zn Met 175).

Induction of polycystic ovarian syndrome

As previously reported, EV was used to induce PCOS.[19] To ensure the induction of PCOS, four animals in per PCOS group were sacrificed at the end of the injection period, and blood samples were collected through cardiac puncture, then hormonal studies and morphological were investigated. According to the previous study, after induction and confirmation of PCOS, treated groups received three levels of the organic supplement of ZM dissolved in distilled water for 15 days by gavage.[12]

Biochemical and histological studies

To assess biochemical parameters, the rats were fasted overnight, weighed by digital scales, ketamine + xylazine anesthetized, and blood samples (5 mL) were taken by cardiac puncture. Blood samples were taken by cardiac puncture and were centrifuged with 3000 rpm for 15 min; blood serum was separated and kept in −20°C until the measurement of hormones. Serum concentrations of FSH, and LH by specific commercial ELISA kits. The serum concentrations of free triiodothyronine (FT3), free thyroxine (FT4), and (TSH, RK-554A120901., Budapest, Magyarország) were assessed by a radioimmunoassay kit.[20]

The investigation of follicles

To investigate the follicles, ovaries were dissected apart, fixed in 10% formaldehyde, maintained in alcohol solutions for dehydration, cleared in xylene, and then embedded in paraffin. The samples were sectioned serially in 5μ thickness by microtome and finally stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Premature follicles (PMF), primary follicles (PF), preantral follicles (PAF), antral follicles (AF), corpus luteum (CL), and cystic follicles (CF) were investigated.

Statistical analyses

SPSS software version 23 (Stanford University, Chicago, USA) was used to analyze the data; data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD); One-way ANOVA, Duncan test was used for the comparison between groups; and t-test was used for comparison between two groups. Finally, the graphs were plotted by Graph Pad Prism software version 5.0a (Graph Pad Prism, San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The effects of the treatments on FSH, LH, and LH/FSH ratio.

Table 1 shows the results for the effects of treatments on the serum concentrations of FSH, LH, and LH/FSH ratio. According to these results, the induction of PCOS decreased the serum concentrations of FSH (P < 0.05), but it increased the serum concentration of LH (P < 0.05) and the LH/FSH ratio (P < 0.05) (Control vs. PCOS). Oral administration of ZM at the levels of 75 and 175 mg (PCOS + Zn Met 75 and PCOS + Zn Met 175) increased the serum concentration of FSH and decreased the serum concentration of LH, and the LH/FSH ratio (Both P < 0.05). In comparison with PCOS group, the treatment with ZM at the level of 25 mg/kg did not have a significant effect on LH, FSH, and its ratio (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

The effects of treatments on the serum concentration of follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and the luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone ratio

| Groups | FSH (IU/L) | LH (IU/L) | LH/FSH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.26±0.23 | 3.69±0.31 | 0.701±0.02 |

| PCOS | 2.07±0.34# | 5.25±0.49# | 2.61±0.69# |

| PCOS +Zn Met 25 | 2.11±0.23 | 5.22±0.39 | 2.49±0.40 |

| PCOS +Zn Met 75 | 5.44±0.33˟ | 4.56±0.27˟ | 0.76±0.02˟ |

| PCOS +Zn Met 175 | 5.74±0.34˟ | 4.16±0.38˟ | 0.79±0.10˟ |

| P | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD. #P<0.05; differences between control group and PCOS group, ˟P<0.05; differences between PCOS group and PCOS treated groups. LH/FSH: Luteinizing hormone/Follicle-stimulating hormone, PCOS: Polycystic ovarian syndrome, SD: Standard deviation

The effects of treatments on thyroid hormone levels

Table 2 demonstrates the results for the effects of treatments on the concentration of thyroid hormones. As the results show, that the serum concentration of FT3 was not influenced by the treatments (P > 0.05). Comparing the control and PCOS showed that the induction of PCOS increased the serum concentrations of TSH and decreased the FT4 levels (Both P < 0.05). The treatments of the rats with ZM at levels of 75 and 175 mg/kg decreased the concentrations of TSH and increased FT4 compared to the PCOS group (P < 0.05). The treatment with ZM at the level of 25 mg/kg did not have any significant effects on the thyroid hormones compared to the PCOS group (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

The effects of treatments on the serum concentrations of FT3, FT4, and thyroid-stimulating hormone

| Groups | FT3 (pmol/L) | FT4 (pmol/L) | TSH mIU/L |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.19±0.53 | 28.38±5.29 | 1.29±0.26 |

| PCOS | 3.27±0.79 | 21.29±5.87# | 2.92±0.38# |

| PCOS +Zn Met 25 | 3.32±0.89 | 22.40±4.48 | 2.82±0.40 |

| PCOS +Zn Met 75 | 3.80±0.82 | 35.99±3.17˟ | 1.96±0.29˟ |

| PCOS +Zn Met 175 | 4.27±0.79 | 39.76±3.55˟ | 1.60±0.27˟ |

| P | 0.180 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD. #P<0.05; differences between Control group and PCOS group, ˟P<0.05; differences between PCOS group and PCOS treated groups. TSH: Thyroid-stimulating hormone, PCOS: Polycystic ovarian syndrome, SD: Standard deviation

Number of follicles

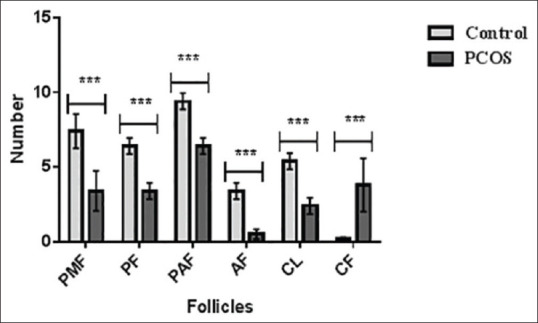

Figure 1 shows the effect of treatments on the number of follicles in PCOS and the control groups. The results showed that the induction of PCOS decreased PMF (7.40 vs. 3.40), PF (6.40 vs. 3.40), PAF (9.40 vs. 6.40), AF (3.40 vs. 0.50), and CL (5.40 vs. 2.40), but increased CF (0.20 vs. 3.80).

Figure 1.

Comparison of follicles in control and polycystic ovarian syndrome groups (mean ± standard deviation). ***P < 0.001; control versus polycystic ovarian syndrome. PMF: Primordial follicle, PF: Primary follicle, PAF: Parenteral follicle, AF: Antral follicle, CL: Corpus luteum, CF: Cystic follicle

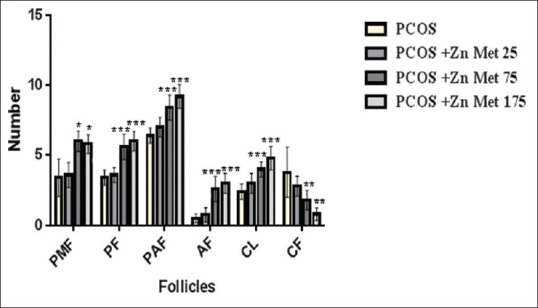

Figure 2 shows the results for the comparison of follicle numbers in PCOS groups. It reveals that the treatment with ZM at the concentrations of 75 and 175 mg/kg increased PMF, PF, PAF, AF, and CL: However, it decreased CF compared to ZM 25 mg/kg and PCOS groups (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between 75 and 175 mg/kg treatments (P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Comparison of follicle in polycystic ovarian syndrome groups (mean ± standard deviation). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; differences between polycystic ovarian syndrome group and polycystic ovarian syndrome treated groups; PMF: Primordial follicle, PF: Primary follicle, PAF: Parenteral follicle, AF: Antral follicle, CL: Corpus luteum, CF: Cystic follicle

Discussion

This study was conducted to evaluate the effects of ZM on the reproductive and thyroid hormones in rats with PCOS. The most common causes of female infertility are the ovulation problems often caused by PCOS. Thus, it has become the most common endocrine disorder among women in the reproductive age.[21] The results showed that PCOS increased the serum concentrations of LH; however, it decreased the serum concentration of FSH. The irregular production of estrogen may have a positive feedback on LH release and a negative effect on FSH production, which increases the ratio of LH/FSH in the blood.[12] It was reported that the increase of free estradiol through a decrease of SHBG, increases LH concentration in PCOS patients.[22] A faulted in androgen synthesis increases ovarian androgen production.[23] On the other hand, the increased levels of LH lead to cause the thickness of the theca cell layer. In fact, LH is necessary for the expression of gonadal steroidogenic enzymes and sex hormone secretion.[24] Furthermore, the elevated LH levels lead to androgen hypersecretion by increasing the expression of the key enzymes in androgen synthesis.[19] Furthermore, there is a positive correlation between the high levels of androgen and insulin resistance. In PCOS women, elevated insulin levels are common which bringing about an increase in LH-stimulated androgen production.[25] The production of progesterone by corpus luteum regulates the concentration of LH against the high level of FSH that has an important role for mature follicles for next bleeding. However, in the women suffering from PCOS disease, the abnormality of LH related to less response for progesterone and defect in the frequency of FSH can increase the ratio of LH/FSH.[26] High levels of LH and increased LH: FSH ratios are considered as the biomarkers for the diagnosis of PCOS in women.[21] The increased level of LH promotes the production of estrogen, testosterone and dihydroepiandrosterone sulphate that causes to develop the cyst in the ovary.[24] Increased LH during PCOS shows that pituitary gland has decreased the production of FSH and increased the production of LH.[26] The results showed that the higher levels of ZM increased FSH concentration and decreased LH concentration. It was reported that zinc deficiency reduces the production of FSH and LH.[27] Zinc is involved in reproductive hormones by improving gonadal activity and steroid feedback.[28] These observations indicated that the higher levels of ZM can have the positive effects on the endocrine system, whereas the lower levels (25 mg/kg BW) did not have any significant effects on LH and FSH. Simply put, the lower levels did not have enough efficiency to affect LH and FSH, which may be associated to insufficient bioavailability. The rats treated with 175 mg/kg of ZM showed higher efficiency in improving the reproductive performance that is probability related to the sufficient amount of zinc.

The results showed that the induction of PCOS decreased follicles and increased cyst number. The number of developed follicles and their morphology depend on the reduced levels of steroid hormones.[29] The decreased follicles and increased number of cyst may be associated with persistent hyperandrogenism that arrests oocyte maturation and the activation of PF.[6] As a follicle matures, androgens prevent proliferation and increase apoptosis.[30,31,32] PCOS also increased the cyst number. Follicular cysts had flattened epithelioid cell layers facing the antrum and thickened hyperplastic theca interna cells in the cyst walls.[33] It was also reported that prolactin prevented folliculogenesis and blocked granulosa cell aromatase activity that caused hypoestrogenism and anovulation.[34] In general, PCOS increases the concentration of LH and affects the follicle numbers and cysts. It can be stated that ZM affects the release of FSH and LH and contribute to normal follicular growth distribution, which leads to the lack of cystic follicles formation.

The results showed that the induction of PCOS increased the serum concentrations of TSH and decreased the FT4 levels. PCOS and thyroid disorder were two of the most common endocrine disorders in PCOS patients.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] There is an interconnection between genetic and environmental factors, which can influence thyroid disorders in PCOS, known as PCOS-like ovaries and overall worsening of PCOS and insulin resistance.[36] Furthermore, Shirsath et al. reported that hypothyroidism can decrease sex hormone-binding globulin and increase free testosterone.[9] Abnormalities in thyroid hormones for the peripheral tissue are related to the changes in a number of metabolic processes.[8] The results showed that PCOS increased TSH. On the other hand, in comparison with the PCOS group, the treatment of PCOS rats with ZM (75 and 175 mg/kg BW) led to the improvement of thyroid hormones. However, lower levels did not have any significant effects on thyroid hormones, which may be attributed to an insufficient level. Zinc has a vital role in the metabolism of thyroid hormones through regulating deiodinase enzymes activity, TRH and TSH synthesis, and involvement in the structures of essential transcription factors in the synthesis of thyroid hormones. It was reported that serum concentrations of zinc affect the levels of serum T3, T4, and TSH due to its role in the hypothalamus, pituitary, and thyroid, but their functions remain unknown.[18]

Conclusion

In general, the induction of PCOS increased the serum concentration of LH and decreased FSH concentration. It also decreased the follicles in different stages of growth, increased the number of cysts, and affected thyroid hormones adversely. The treatment with ZM in higher levels could decrease the adverse effects of PCOS. The results showed that ZM may be a useful treatment for improving the PCOS through the reduction of LH, LH/FSH ratio, TSH, and the number of cystic follicles, and the increase in the number of active follicles and subsequently improved of the ovulation. In fact, these effects are dose dependent, and the therapeutic potential of ZM in the higher levels (75 and 175 mg/kg BW) are more effective.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The results presented in this article were part of a Ph.D. student thesis. This study has been performed in the Laboratory Complex of the Science and Research Branch of Islamic Azad University, Tehran.

References

- 1.Huang W, Li S, Luo N, Lu K, Ban S, Lin H. Dynamic analysis of the biochemical changes in rats with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) using urinary 1H NMR-based metabonomics. Horm Metab Res. 2020;52:49–57. doi: 10.1055/a-1073-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang HL, Yi M, Li D, Li R, Zhao Y, Qiao J. Transgenerational inheritance of reproductive and metabolic phenotypes in PCOS rats. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:144. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha U, Sinharay K, Saha S, Longkumer TA, Baul SN, Pal SK. Thyroid disorders in polycystic ovarian syndrome subjects: A tertiary hospital based cross-sectional study from Eastern India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:304–9. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.109714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez Paris V, Bertoldo MJ. The Mechanism of Androgen Actions in PCOS Etiology. Med Sci (Basel) 2019;7:89–100. doi: 10.3390/medsci7090089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witchel SF, Oberfield SE, Peña AS. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment with emphasis on adolescent girls. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3:1545–73. doi: 10.1210/js.2019-00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palomba S, Daolio J, La Sala GB. Oocyte competence in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28:186–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang J, Liu L, Chen C, Gao Y. PCOS without hyperandrogenism is associated with higher plasma trimethylamine N-oxide levels. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20:3. doi: 10.1186/s12902-019-0486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elslimani FA, Elhasi M, Elmhdwi MF. The relation between hypothyroidism and polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pharm Appl Chem. 2016;2:197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirsath A, Aundhakar N, Kamble P. Does the thyroid hormonal levels alter in polycystic ovarian disease.A comparative cross sectional study? Indian J Basic Appl Med Res. 2015;4:265–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethi P. Evaluation of serum prolactin, FSH and LH levels in women with thyroid disorders: A hospital based study. Indian J Appl Res. 2016;6:460–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabersˇcˇek S, Zaletel K, Schwetz V, Pieber T, Pietsch BO, Lerchbaum E. Thyroid and polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172:R9–21. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fazel Torshizi F, Chamani M, Khodaei HR, Sadeghi AA, Hejazi SH, Majidzadeh Heravi R. Therapeutic effects of organic zinc on reproductive hormones, insulin resistance and mTOR expression, as a novel component, in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2020;23:36–45. doi: 10.22038/IJBMS.2019.36004.8586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang D, Hu Q, Fang S, Feng J. Dosage effect of zinc glycine chelate on zinc metabolism and gene expression of zinc transporter in intestinal segments on rat. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016;171:363–70. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagalakshmi D, Sridhar K, Parashuramulu S. Replacement of inorganic zinc with lower levels of organic zinc (zinc nicotinate) on performance, hematological and serum biochemical constituents, antioxidants status, and immune responses in rats. Vet World. 2015;8:1156–62. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2015.1156-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Souza AR, Martins LP, De Faria LC, Martins ME, Fereira RN, De Silva AM, et al. Studies on the bioavailability of zinc in rats supplementated with two different zinc-methionine compounds. Lat Am J Pharm. 2007;26:825–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koppa NA, Jatmika C. Synthesis and analysis of zinc-methionine, zinc-tryptophan, copper-lysine, and copper-isoleucine complexes using atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Int J App Pharm. 2018;10:416–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guler I, Himmetoglu O, Turp A, Erdem A, Erdem M, Onan MA, et al. Zinc and homocysteine levels in polycystic ovarian syndrome patients with insulin resistance. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;158:297–304. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-9941-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Severo JS, Morais JB, de Freitas TE, Andrade AL, Feitosa MM, Fontenelle LC, et al. The role of zinc in thyroid hormones metabolism. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2019;89:80–8. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pournaderi PS, Yaghmaei P, Khodaei H, Noormohammadi Z, Hejazi SH. The effects of 6-Gingerol on reproductive improvement, liver functioning and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in estradiol valerate-Induced polycystic ovary syndrome in wistar rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;484:461–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pohlenz J, Maqueem A, Cua K, Weiss RE, Van Sande J, Refetoff S. Improved radioimmunoassay for measurement of mouse thyrotropin in serum: Strain differences in thyrotropin concentration and thyrotroph sensitivity to thyroid hormone. Thyroid. 1999;9:1265–71. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bednarska S, Siejka A. The pathogenesis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: What's new? Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:359–67. doi: 10.17219/acem/59380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbott DH, Dumesic DA, Franks S. Developmental origin of polycystic ovary syndrome-a hypothesis. J Endocrinol. 2002;174:1–5. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1740001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soni A, Singla S, Goyal S. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Pathogenesis, treatment and secondary diseases. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2018;8:107–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenfield RL, Ehrmann DA. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): The hypothesis of PCOS as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. Endocr Rev. 2016;37:467–520. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teede HJ, Hutchison S, Zoungas S, Meyer C. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease risk in women with PCOS. Endocrine. 2006;30:45–53. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:30:1:45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Juaifari B, Al-Jumaili E. Correlation of body mass index and some hormones (estradiol, luteinizing, follicle stimulating hormones) with polycystic ovary syndrome among young females [20-35 years] Biomed Pharmacol J. 2020;13:193–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauer AK, Hagmeyer S, Grabrucker AM. Zinc deficiency. In: Erkekoglu P, Kocer-Gumusel B, editors. Nutritional Deficiency. London, UK: InTechOpen; 2016. pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakheet M, Almarshad H. Improving effect of zinc supplementation in pituitary gonadotropins secretion in smokers.Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;8:81–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baravalle C, Salvetti NR, Mira GA, Pezzone N, Ortega HH. Microscopic characterization of follicular structures in letrozole-induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in the rat. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:830–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harlow CR, Shaw HJ, Hillier SG, Hodges JK. Factors influencing follicle-stimulating hormone-responsive steroidogenesis in marmoset granulosa cells: Effects of androgens and the stage of follicular maturity. Endocrinology. 1988;122:2780–7. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-6-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice S, Ojha K, Whitehead S, Mason H. Stage-specific expression of androgen receptor, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor, and anti-Müllerian hormone type II receptor in single, isolated, human preantral follicles: Relevance to polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1034–40. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franks S, Hardy K. Androgen action in the ovary. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:452. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang H, Lee SY, Lee SR, Pyun BJ, Kim HJ, Lee YH, et al. Therapeutic effect of ecklonia cava extract in letrozole-induced polycystic ovary syndrome rats. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1325. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murugesan MB, Muralidharan P, Hari R. Effect of ethanolic seed extract of Caesalpinia bonducella on hormones in mifepristone induced PCOS rats. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2020;10:72–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanmugham D, Natarajan S, Karthik A. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome: A cross sectional study. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2018;7:3055–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moustafa MM, Jamal MY, Al-Janabi RD. Thyroid hormonal changes among women with polycystic ovarian syndrome in Baghdad-a case-control study. F1000esearch. 2019;8:1–14. [Google Scholar]