Abstract

Metabolic indices are the wide range of characteristic factors, which can be changed during several medical conditions such as metabolic syndrome. Nutrition and related behaviors are one of the main aspects of human lifestyle which recent investigations have recognized their roles in the development of metabolic disorders. According to the spread of risky nutritional habits/behaviors due to the changes in lifestyle, and its importance in the prevalence of metabolic disorders, the authors attempted to summarize these evidences in a systematic review. The present study is a systematic review that encompasses those studies investigating the association between metabolic indices and nutritional/dietary behaviors published in two international databases in recent 11 years. Twenty-nine related articles were considered and their data were extracted. The relation between food choices and metabolic indices is more frequent in studies. While, inhibition and abstinent and eating together were two behavioral sets with the smallest share of research. Anthropometric indices have the highest rate in the evaluations. Finding the links between nutritional behavior and metabolic indices will be the key point in selecting the different types of interventions. These results will guide therapists to the accurate recognition of metabolic effects in targeting behavior for their intervention.

Keywords: Behavior, feeding behavior, metabolism, nutrition assessment

Introduction

Metabolic indices are the wide range of characteristic factors, which can be changed during several medical conditions. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) as the main metabolic disorder with impaired metabolic indices is a set of signs and symptoms, including abdominal obesity, glucose intolerance, high blood pressure, and dyslipidemia, in which the insulin resistance is the most common pathophysiologic characteristic. In addition, MetS is one of the most important diseases with metabolic changes and the high proportion of research work on it. More than 1 per 3 American adults involve in MetS.[1] The prevalence of MetS among Middle East countries is reported up to 63%, according to some national surveys.[2,3,4] Regarding these studies, MetS is also correlated with the risk of other diseases, such as type II diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.[2,3,4]

Recent investigations have recognized the role of lifestyle in the development of chronic diseases such as diabetes and MetS. Nutrition and related behaviors are one of the main aspects of human lifestyle whose effects on metabolic indices have been shown in studies.[5,6,7,8,9] For instance, some researches have demonstrated that a healthy diet is associated with a decline in the prevalence of MetS.[6,7,10,11,12] Furthermore, the effect of emotional eating disorders on the weight control and its significant role in the development of MetS has been proven.[13,14,15,16] In fact, the “eating until feeling full” and “fast eating” are two abnormal habits, which are in relation with high blood pressure, impaired lipid profiles, and fatty liver.[17] As well as, evidences on behaviors such as the type of food and the number of daily meals, especially breakfast, demonstrate their association with metabolic indices.[8,18]

A closer look on the studies conducted so far reveals that nutritional issues and their metabolic correlates include the wide range of topics, such as nutritional habits, eating patterns, and food content; among them, the nutritional habits – metabolic axis – is the point of interest in recent years.[7,19,20,21]

According to the spread of risky nutritional habits/behaviors due to the changes in lifestyle, and its importance in changing metabolic indices and consequently the prevalence of metabolic disorders, the authors attempted to summarize these evidences by designing and running a systematic review to provide a general overview in this regard. Regarding the fact that the authors could not find the comprehensive research in this field, it seems that the current study could gather the results of existing research and show a future horizon for the next studies.

Materials and Methods

The present study is a systematic review that encompasses those studies investigating the association between metabolic indices and nutritional/dietary behaviors as the following.

Search strategy

Two valid databases, PubMed and Scopus, were searched using key words including Dietary, Eating, Nutrition, Habit, Behavior, and a combination of them to identify studies conducted until September 2019. The articles were limited to those human studies published in English since 2008. It should be noted that only original studies were included in the current research.

Study selection

After reading the titles, the articles were categorized as relevant and nonrelevant by two researchers, according to study objectives. The relevant ones were read in their full text in order to data extraction.

Quality assessment

Followed by determining the relevant studies in terms of titles and abstracts, the researchers used the STROBE checklist (i.e., strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) which is a standard checklist to evaluate the selected papers. Articles given at least score 40 points according to the checklist questions were entered into the research.

Data extraction

All articles were further evaluated in terms of the behaviors and metabolic indices. All data including title, year of publication, samples, measurements, measurement tools, and main findings of the selected papers were extracted and categorized in the form of a table.

Results

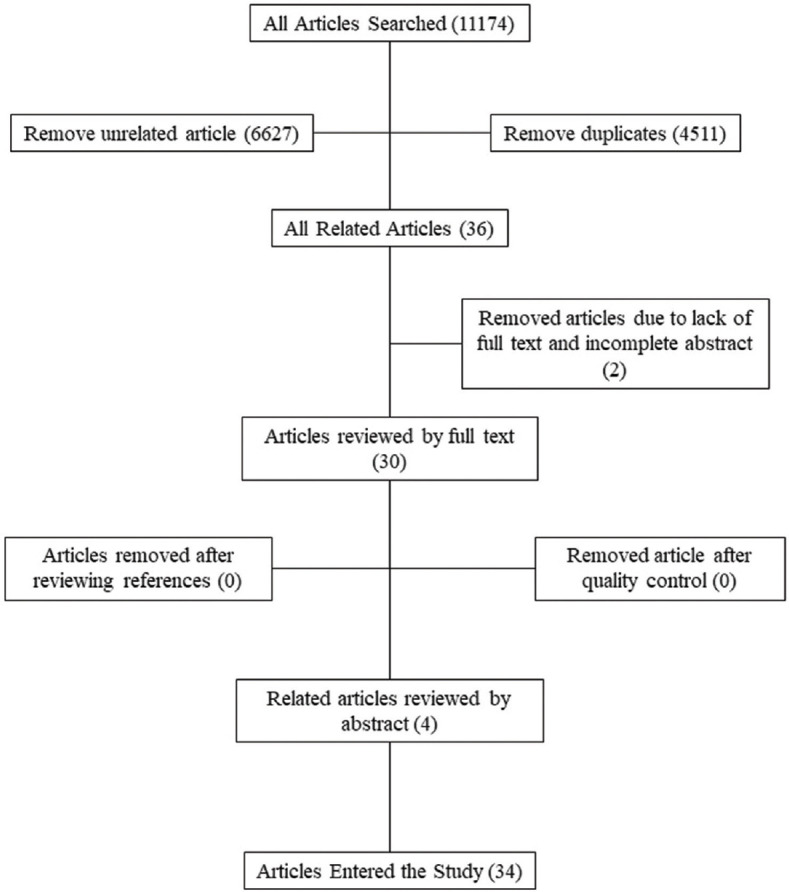

Totally, the 11,174 articles were found in initial search. Nearly 4511 articles were duplicates, and 6627 articles served as irrelevant after the evaluation. Finally, 34 related articles were considered and their data were extracted. A summary of the data of these papers is summarized in Figure 1. The five full texts were not available, so E-mails were sent to their authors to request the full text. Four authors did not respond after 2 weeks, but because of the lack of papers in this area, we tried to extract data from the abstracts in their full capacity.

Figure 1.

The flowchart shows the process of searching and selecting articles for the review

In the end, in all of these 34 remaining studies, 47 behavioral codes and 83 metabolic indices were measured in participants. The data extracted from these articles are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data extracted from selected articles, including: authors, year of publication, title, study participants, measurements, tools, and main findings

| Code | Author | Year | Title | Participants | Measurements | Measurement tools | Main finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ahn et al.[6] | 2013 | Rice-eating pattern and the risk of metabolic syndrome especially waist circumference in Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) | 26,006 participants enrolled in the Korean Genome | Central obesity Abnormal HDL-C Blood pressure Fasting glucose Weight Height Waist circumference Triglycerides Rice-eating pattern Kind of rice (white rice only/rice with other foods/mix two types) Consumption frequency and amount of cooked rice |

Questionnaire Blood sample |

The risk for MetS was lower in the rice with beans and rice with multigrain groups either in white rice group, particularly in postmenopausal women |

| 2 | Al-Daghri et al.[7] | 2013 | Selected dietary nutrients and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in adult males and females in Saudi Arabia: A pilot study | 185 adult Saudis aged 19-60 years (information was obtained from the existing database, 17,000 individuals) | Fluid and diet supplements during the day Food preparation methods, recipe ingredients The frequency of physical activity Fasting glucose Weight Height Waist circumference Blood pressure Hip circumference Lipid profile (HDL, LDL, triglyceride) |

Questionnaire | The qualification of the food (amount of Vitamins A, C, E, and K, calcium, zinc, and magnesium in food) has a great impact on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, especially in adult females |

| 3 | Alexandrov et al.[8] | 2014 | The specificity of schoolchildren’s eating habits in Moscow and Murmansk | 785 children 10-17 years old residing in two cities | Meal ratio per day Frequency of vegetables and fruit intake Fast food intake Hot meals, soft drinks, meat, fish and milk intake, usage of school cafeteria, regularity of breakfasts Weight Height BMI Overweight Obesity Waist circumference |

Questionnaire | Mothers’ education condition has a great impact on children’s eating behavior Eating breakfast could prevent obesity |

| 4 | Al-Haifi et al.[9] | 2013 | Relative contribution of physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and | 906 adolescents (463 boys and 443 girls) aged between 14 and 19 years, selected from school | Television viewing Playing video and computer games and Internet use How many times per typical week they consumed breakfast |

Questionnaire | Physical activity explains a greater proportion of variation in BMI than eating habits, particularly in boys |

| dietary habits to the prevalence of obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents | Sugar-sweetened drinks (soft beverages; milk and dairy products) Vegetable consumption Potato consumption Fruit consumption Doughnut or cake consumption Sweet consumption Energy drinks Fast food consumption Olive oil, nuts, cereal Meat consumption Carbohydrate consumption Total energy intake Protein consumption Total fat BMI Blood pressure |

Eating habits explain a greater proportion of variation in BMI than physical activity in girls |

|||||

| 5 | Alhakbany, et al.[22] | 2018 | Lifestyle Habits in Relation to Overweight and Obesity among Saudi Women Attending Health Science Colleges |

454 female students were randomly recruited | Age (y) Weight (kg) Height (cm) BMI (kg/m2) Overweight Obesity How many times per week they consume breakfast Vegetable (cooked and uncooked) consumption Fruit consumption Milk and dairy product consumption Sugar-sweetened drink consumption (including soft drinks) Fast food, donut/cake, sweet, and chocolate consumption Energy drink consumption |

Questionnaire | The present study showed that there was no significant difference between overweight/obese and nonoverweight/nonobese females in physical activity levels, screen time, sleep duration, or dietary habits |

| 6 | Almanza, et al.[23] | 2017 | Microbial metabolites are associated with a high adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern using a (1) H-NMR-based untargeted metabolomic approach | Study population included men (55-80 years) and women (60-80 years) without a previous history of CVD | BMI Food intake Dietary intake (Mediterranean) Carbohydrate intake Total energy intake Protein consumption Total fat intake 3-methylhistidine Alanine Anserine |

Questionnaire Urine samples | These dietary biomarkers shows the MedDiet intrigued several molecular mechanisms in cascade way with complex regulatory systems. Assessing these factors would improve dietary evaluation and molecular mechanisms at the same time. |

| Carnosine Creatine Creatinine Glycine Guanidoacetate Histidine Lysine N-acetylglutamine Proline betaine Gut microbiota metabolites 3-indoxyl sulfate 4-hydroxyhippurate 4-hydroxyphenylacetate Dimethylsulfone Hippurate Isobutyrate Phenylacetylglutamine Β-glucose Lactate Succinate Dimethylamine Betaine Tmao Scyllo-inositol N-methylnicotinamide Isopropanol Xanthosine Methylguanidine Malonate |

|||||||

| 7 | Almoosawi et al.[19] | 2013 | Time-of-day and nutrient composition of eating occasions: Prospective association with the metabolic syndrome in the 1946 British birth cohort |

1488 survey members, aged 43 years | Waist circumference Glycosylated hemoglobin Triacylglycerol Blood pressure Time of day eating: Breakfast, mid-morning, lunch, mid-afternoon, dinner, late evening, and extras |

Questionnaire blood sample | Increased carbohydrate intake in the morning while reducing fat, protected against long-term development of the metabolic syndrome and its components |

| 8 | Anderson et al.[20] | 2011 | Dietary patterns and survival of older adults | 3075 older adults | Dietary patterns (six clusters were identified: Healthy foods, high-fat dairy products, meat, fried foods and alcohol, breakfast cereal refined grains, and sweets and desserts) Total fat mass Weight Height |

Questionnaire | A dietary pattern consistent with high amounts of vegetables, fruit, whole grains, poultry, fish, and low-fat dairy products may be associated with superior nutritional status, quality of life, and survival in older adults |

| 9 | Angoorani, et al.[24] | 2016 | Dietary consumption of advanced glycation end products and risk of metabolic syndrome | 5848 adults, aged 19-70 years | Daily consumption of carboxymethyl lysine and advanced glycation end products Food frequency Lipid profile |

Questionnaire | AGE intake could be a practical approach to prevent metabolic abnormalities |

| 10 | Atkins et al.[10] | 2016 | Dietary patterns and the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality in older British men | 3226 older British men, aged 60-79 years and free from CVD | Lifestyle and medical history Alcohol consumption Physical examination Three interpretable dietary patterns (high fat/low fiber, prudent, and high sugar) HDL Glucose Two emerging cardiovascular risk CRP |

Questionnaire ultrasensitive Nephelometry and vWF, ELISA |

Avoiding “high-fat/low-fiber” and “high-sugar” dietary components may reduce the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in older adults |

| 11 | Bajaber et al.[25] | 2016 | Dietary approach and its relationship with metabolic syndrome components | Six hundreds of female teachers, aged 30-55 years | Food frequency Demographic medical history Blood pressure |

Questionnaire | Healthful dietary patterns were associated with a reduced risk for MS in Saudi women at middle age |

| 12 | Bajerska et al.[26] | 2014 | Eating patterns are associated with cognitive function in the elderly at risk of metabolic syndrome from rural areas | Polish elderly people 60 years | Body weight Height Waist circumference BMI HDL-C TG BG Resting seated blood pressure The consumption of milk and milk products, eggs and egg products Meat and meat products Fish Mollusks Reptiles Crustaceans and their products Oils, fats and their products Grains and grain products Pulses, seeds, kernels, nuts, and their products Vegetables and vegetable products Fruits and fruit products Sugar and sugar products Chocolate products and confectionery Beverages (nonmilk) Miscellaneous, soups Sauces, snacks, and products Products for special nutritional use |

Questionnaire blood sample | Greater adherence to MedDiet and frequency consumption of vegetables, fish, and olive or rapeseed oil with limitations in the intake of red meat, meat products, and full-fat dairy product in particular were associated with better scores in several CF tests |

| 13 | Barbaresko et al.[11] | 2014 | Comparison of two exploratory dietary patterns in association with the metabolic syndrome in a Northern German population | 905 participants, Northern German cohort (aged 25-82 years) | High potato intakes Vegetable consumption Red/processed meat consumption Fats, sauce/bouillon consumption Weight BMI Waist circumference Hip circumference Blood pressure Arithmetic was calculated TAG TC LDL HDL-C HbA1c levels Concentrations of glucose |

PCA RRR analysis Blood sample | The disease-related RRR pattern is likely to be present to some extent in the study population. Nevertheless, comparing simplified dietary patterns, individuals with higher RRR dietary pattern scores showed a higher likelihood of having the MetS compared with those with high PCA dietary pattern scores A pattern of concordant food groups in the PCA and RRR analysis consisting of legumes, beef, processed meat, and bouillon still showed a positive association with the prevalence of the MetS The application of both methods may be advantageous to estimate the similarity between real-world behavior- and disease-related patterns to obtain information for designing and realizing dietary guidelines |

| 14 | Bean et al.[27] | 2011 | 6-month dietary changes in ethnically diverse, obese adolescents participating in a multidisciplinary weight management program | n=67. Participants (75% African American, 66% female, mean age=13.7 years) | Physical activity Anthropometrics Fasting blood lipid Total energy Total fat Saturated fat Carbohydrate/sodium/sugar intakes Fiber, fruit/vegetable intake |

- | Participation in this multidisciplinary treatment helped participants make behaviorally based dietary changes, which were associated with improved dietary intakes and health status |

| 15 | Bloomer et al.[28] | 2012 | Impact of short-term dietary modification on postprandial oxidative stress | 10 men and 12 women, aged 35±3 years | Consumption of the milkshake (fat=0.8 g/kg; carbohydrate=1.0 g/kg; protein=0.25 g/kg) Heart rate Blood pressure Blood samples analyzed for TAG MDA lipid peroxidation (MDA) Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) AOPP Nitrate/Nitrite (NOx), TEAC Calorie intake Protein intake Carbohydrate intake Fiber, sugar, fat, saturated fat, omega 3-6, cholesterol, Vitamin A, C, E intake |

Blood sample Daniel fast |

21-day Daniel fast (this diet allows for ad libitum intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, legumes, and oil) does not result in a statistically significant reduction in postprandial oxidative stress |

| 16 | Burkert et al.[29] | 2014 | Nutrition and health: different forms of diet and their relationship with various health parameters among Austrian adults | The Austrian Health Interview Survey 2006/07 (n=15,474) | The SES BMI Eating a carnivorous diet less rich in meat | - | Vegetarian diet is associated with a better health-related behavior, a lower BMI, and a higher SES |

| 17 | Castro et al.[30] | 2016 | Examining associations between dietary patterns and metabolic CVD risk factors: A novel use of structural equation modeling |

417 adults of both sexes | Body weight Waist circumference High-sensitivity CRP Blood pressure TC: HDL-cholesterol ratio TAG: HDL-C ratio Fasting plasma glucose Serum leptin Food consumption |

Blood sample questionnaire | “Traditional” and “prudent” dietary patterns were negatively associated with metabolic cardiovascular risk factors among Brazilian adults |

| 18 | Chan et al.[31] | 2014 | A Cross-sectional Study to Examine the Association Between Dietary Patterns and Risk of Overweight and Obesity in Hong Kong Chinese Adolescents Aged 10-12 Years |

171 boys and 180 girls aged 10-12 years | Weight, height, and Tanner stage Dietary pattern calculation Peak oxygen consumption Association between dietary patterns and risk of overweight and obesity Vegetable-fruit consumption Snack-beverage consumption Animal-based food consumption Fat and condiment dominated consumption |

Questionnaire 3-min step test Multivariate logistic regression with adjustment for demographics, puberty, and physical activity |

Pubertal stage and physical activity, but not dietary patterns, were important factors contributing to the risk of overweight and obesity in this population |

| 19 | Chang et al.[32] | 2014 | Serum phosphorus and mortality in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III): effect modification by fasting | 12,984 participants 20 years or older in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | Serum phosphorus level Fasting duration (dichotomized as ≥12 or <12 h) |

Serum phosphorus measured in a central laboratory Fasting duration recorded as time since food or drink other than water was consumed |

Fasting but not no fasting serum phosphorus levels were associated with increased mortality Risk prognostication based on serum phosphorus may be improved using fasting levels |

| 20 | Choi et al.[33] | 2012 | Characteristics of diet patterns in metabolically obese, normal weight adults (Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 2005) | 3050 adults >20 years of age with a normal BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III | Dietary intake Information on health behaviors (carbohydrates [percentage of energy]/protein/fat) Frequency of snacks Regular diet Kind of snacks BMI (kg/m2) Waist circumference |

Recall Anthropometric measurements |

Reduced intake of carbohydrates and carbohydrate snacks were associated with a lower prevalence of MONW in females |

| 21 | Choi et al.[34] | 2014 | Development and application of a web-based nutritional management program to improve dietary behaviors for the prevention of metabolic syndrome | 29 employees (19 males, 10 females) with more than one metabolic syndrome risk factor | Eating snacks Eating out Dining with others The frequency of intake of foods such as whole grains, seaweed, fruit, and low-fat milk Height Weight Waist circumference BMI Body fat Blood pressure FBG TC HDL-C LDL-C TGs |

Web evaluation questionnaire | Subjects had a significant decrease in body weight, waist circumference, BMI (P<0.01 in males, P<0.05 in females), and body fat (P<0.01 in males) |

| 22 | Chung et al.[35] | 2015 | Soft drink consumption is positively associated with metabolic syndrome risk factors only in Korean women: Data from the 2007-2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | 13,972 participants (5432 men and 8540 women) aged <30 years, from the 2007-2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination | Dietary sugar intake soft drink consumption levels Waist circumference SBP and DBP HDL Cholesterol levels Women, triglyceride levels Fasting plasma glucose levels All anthropometric and clinical data, such as blood pressure and blood tests |

Questionnaire | High levels of soft drink consumption might constitute an important determinant of metabolic syndrome and its components only in Korean adult women |

| 23 | Daubenmier et al.[36] | 2011 | Mindfulness intervention for stress eating to reduce cortisol and abdominal fat among overweight and obese women: An exploratory randomized controlled study | Forty-seven overweight/obese women (mean BMI=31.2) | Mindfulness Psychological distress Eating behavior Weight Cortisol awakening response Abdominal fat |

By dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry Salivary cortisol |

Mindfulness training shows promise for improving eating patterns and the CAR, which may reduce abdominal fat |

| 24 | DiBello, et al.[12] | 2009 | Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic syndrome in adult Samoans | American Samoan (n=723) and Samoan (n=785) adults (> or=18 years) | Crab/lobster, coconut products, taro consumption Low intake of processed foods, including potato chips and soda | Questionnaire | Intake of processed foods high in refined grains and adherence to a neo-traditional eating pattern characterized by plant-based fiber, seafood, and coconut products may help to prevent growth in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the Samoan islands |

| 25 | Hsieh et al.[17] | 2011 | Eating until feeling full and rapid eating both increase metabolic risk factors in Japanese men and women | Men (n=8240) and women (n=2955) | Overweight Hypertension Hyperglycemia Hypertriacylglycerolemia Low HDL Cholesterol Hyperuricemia and fatty liver Not eating until feeling full/not eating rapidly (G1) Eating until feeling full only (G2); Eating rapidly only (G3) Eating both rapidly and until feeling full (G4) |

Questionnaire | Both eating until feeling full and eating rapidly increase metabolic risk factors Eating slowly and ending meals shortly before feeling full are important public health messages for reducing metabolic risk factor |

| 26 | Kant et al.[37] | 2009 | Patterns of recommended dietary behaviors predict subsequent risk of mortality in a large cohort of men and women in the United States | n=350,886, aged 50-71 years and disease free at baseline deaths, n=29,838 | Servings of vegetables (excluding salads and potatoes) consumed per week Servings of fruit (excluding juice) consumed per week Usual consumption of whole-grain cereals and breads as such or in sandwiches Usual consumption of lean meat and poultry without skin Usual consumption of low-fat dairy as a drink or in cereal Usual practice of addition of solid fat after cooking or at the table to a number of commonly consumed foods (pancakes, waffles, French toast, potatoes, rice, pasta, cooked vegetables, and gravy to meat) BMI DBS |

Questionnaire Cox proportional hazards regression methods DBS |

Nearly 12% of the covariate-adjusted population risk of mortality was attributable to nonconformity with dietary recommendations Adoption of recommended dietary behaviors was associated with lower mortality in both men and women independent of other lifestyle risk factors |

| 27 | Kim et al.[38] | 2018 | Eating Alone is Differentially Associated with the Risk of Metabolic Syndrome in Korean Men and Women | 8988 Korean adult participants, including 3624 men and 5364 women, aged 18-64 years. | BMI WC (cm) SBP (mmHg) DBP (mmHg) FBG (mg/dL) TC (mg/dL)) HDL-C (mg/dL) TG (mg/dL) Energy intake (kcal/d) Patterns of eating alone were categorized into: Eight groups based on the total frequency of eating alone on a daily basis in the past 1 year |

Questionnaire | Patterns of eating alone are differentially associated with the risk of MetS in a representative sample of Korean adults |

| 28 | Miguet et al.[39] | 2019 | Cognitive restriction accentuates the increased energy intake response to a 10-month multidisciplinary weight loss program in adolescents with obesity | Thirty-five adolescents (mean age: 13.4±1.2 years) with obesity | BMI Fat mass Fat-free mass Resting metabolic rate Respiratory quotient Restrained eating (individuals’ efforts to limit their food intake to control body weight or to promote weight loss; 10 items) Emotional eating (excessive eating in response to negative moods; 13 items) External eating (eating in response to food-related stimuli, regardless of the internal state of hunger or satiety; 10 items) |

The DEBQ | A 10-month multidisciplinary weight loss intervention induced an increase in 24-h ad libitum energy Intake compared to baseline, especially in cognitively restrained eaters Initially cognitively restrained eaters tended to lose less body weight compared to unrestrained ones Cognitive restriction may be a useful eating behavior characteristic to consider as a screening tool for identifying adverse responders to weight loss interventions in youth |

| 29 | Kruger et al.[13] | 2016 | Exploring the relationship between body composition and eating behavior using TFEQ in young New Zealand women |

Healthy, young women, aged between 18 and 44 years, were recruited (n=116) from Auckland, NZ (from the Human Nutrition Research Unit [HNRU] database) | Restrict food intake (refers to the ability of an individual to monitor their diet and employ restraint where required to maintain their weight) Disinhibition (overconsumption of food in response to a variety of stimuli, such as emotions or alcohol) Hunger (food intake in response to feelings and perceptions of hunger) Height Body weight Body composition |

Questionnaire Air displacement plethysmography |

In order to stem escalating rates of obesity in the Western world prevention, strategies need to improve By addressing the behaviors involved in the pathogenesis of obesity, we may improve the success of preventative interventions Disinhibition as being the strongest predictor of both BMI and BF percentage in women of healthy body weight Emotional disinhibition may be an important factor in weight gain as it predicts BF percentage as well as being associated with overweight status |

| 30 | Shin et al.[40] | 2009 | Dietary intake, eating habits, and metabolic syndrome in Korean men | A total of 7081 men aged 30 years and older (from the National Cancer Center in South Korea) | Height Weight BMI Cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol High-density lipoprotein cholesterol Fasting glucose Cereals, salty Foods, yellow vegetables, green leafy vegetables, seaweed Fruits, processed meat, protein-containing foods, dairy Foods, bonefish, oily foods, high-cholesterol foods, animal Fat, sweet foods, instant foods, and caffeinated drinks |

Questionnaire body composition analyzer | In this cross-sectional analysis of dietary factors and the risk of metabolic syndrome, eating oily foods or seaweed, eating fast, and frequent overeating were associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. Our findings suggest a possible involvement of dietary habits in metabolic syndrome development |

| 31 | Sierra-Johnson et al.[41] | 2008 | Eating meals irregularly: A novel environmental risk factor for the metabolic syndrome | 3,607 individuals (1686 men and 1921 women), aged 60 years, was conducted in Stockholm County, Sweden | Serum glucose Serum insulin levels Serum cholesterol and triglycerides HDL LDL γ-Glutamyltransferase Meal regularity |

Questionnaire and a medical examination | Eating meals regularly is inversely associated to the metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and (high) serum concentrations of γ-glutamyltransferase |

| 32 | Son et al.[42] | 2019 | Influence of living arrangements and eating behavior on the risk of metabolic syndrome: A National Cross-Sectional Study in South Korea | 16,015 South Koreans aged >19 years | Living alone Total energy intake (kcal/day) Total carbohydrate intake (g/day) Total protein intake (g/day) Total fat intake (g/day) Waist circumference TG (mg/dL) Blood pressure FBG (mg/dL) |

Questionnaire | Older adults (65 years) did not differ in dietary intake or prevalence of metabolic syndrome according to their living and eating situations. Younger adults living and eating alone may benefit from customized nutrition and health management programs to reduce their risk of metabolic syndrome. |

| 33 | Tao et al. [43] | 2018 | Association between self-reported eating speed and metabolic syndrome in a Beijing adult population: A cross-sectional study | 7972 adults who were 18-65 years old and who received health checkups | Central obesity Elevated TG Reduced HDL Elevated BP (hypertension) Elevated FPG Drinking status Excessive salt intake Excessive sugar intake Excessive fat intake Excessive meat intake A mainly vegetable diet Frequency of eating breakfast Grain consumption A history of antihypertensive Antidiabetic and hypolipidemic treatment Eating speed (slow, medium, fast) |

Questionnaire | Eating speed is positively associated with MetS and its components. |

| 34 | Thomas et al.[18] | 2015 | Usual breakfast eating habits affect response to breakfast skipping in overweight women | Healthy women of all ethnic groups, ages 25-40, with BMI 27-35 kg/m2, without eating disorders, and who were either habitual breakfast eaters (Easters) or breakfast skippers (skippers) | Insulin concentrations Leptin (Millipore) Serum PYY concentrations Total serum ghrelin concentrations Glucose, TG, and FFA Eating breakfast habit |

Questionnaire | Skipping breakfast (higher insulin and FFA responses to lunch, increased hunger, and decreased satiety) were found primarily in habitual breakfast eaters |

CVD: Cardiovascular disease, BMI: Body mass index, LDL: Low-density lipoprotein, HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, CRP: C-reactive protein, vWF: Von Willebrand factor, TG: Triacylglycerol, BG: Blood glucose, HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c, PCA: Principal component analysis, RRR: Relative risk reduction, MDA: Malondialdehyde, AOPP: Advanced oxidation protein products, TEAC: Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity, SES: Socioeconomic status, MONW: Metabolically obese normal weight, FBG: Fasting blood glucose, TC: Total cholesterol, DBS: Dried blood spot, SBP: Systolic blood pressure, DBP: Diastolic blood pressure, WC: Waist circumference, DEBQ: Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire, PYY: peptide YY, FFA: Free Fatty Acids, CF: Cognitive Function, TAG: Triacyl Glycerol

Behavioral codes extracting from the studies were classified and identified into eight categories by an expert panel including food choice, drinking habits, set meals, calorie intake, mindful eating, inhibition and abstinence, eating together, and food safety [Table 2]. Furthermore, the metabolic indices were classified into eight groups including protein and amino acid, glycemic profile, lipid profile, vital signs, anthropometric indices, hormones, diseases, and others by the same experts. These categorizations, mentioned in Table 2, could help a better understanding of research trends on behavior-metabolic relations.

Table 2.

Subcategorized nutritional behaviors based on expert panel discussion

| Behavioral categories | Behavioral codes (in the articles) |

|---|---|

| Food choice | Fast food intake |

| Recipe ingredients | |

| Servings of fruit (excluding juice) consumed per week | |

| The consumption of: Chocolate products and confectionery | |

| Eating a carnivorous diet less rich in meat | |

| Coconut products and taro intakes | |

| The consumption of: Crustaceans and their products | |

| Sodium intakes | |

| The consumption of: Eggs and egg products | |

| Dietary patterns: Prudent (high in poultry, fish, fruits, vegetables, legumes, pasta, rice, whole meal bread, eggs, and olive oil) | |

| The consumption of: Products for special nutritional use | |

| The consumption of: Miscellaneous, soups, sauces, snacks, and products | |

| Frequency and kind of the snack intake | |

| The consumption of: Meat and meat products | |

| Dietary patterns: High fat/low fiber | |

| Dietary patterns: High sugar | |

| Dietary pattern: Healthy foods, high-fat dairy products, and meat | |

| Dietary pattern: Fried foods and alcohol | |

| Dietary pattern: Breakfast cereal refined grains and sweets and desserts | |

| Kind of rice (white rice only/rice with other foods/mix two types) | |

| Milk and dairy products | |

| Doughnuts or cakes | |

| The consumption of: Sugar and sugar products | |

| The consumption of: Vegetables and vegetable products | |

| The consumption of: Fruits and fruit products | |

| Increase of fiber consumption | |

| The consumption of: Grains and grain products | |

| The consumption of: Oils, fats, and their products | |

| The consumption of: Fish | |

| The consumption of: Bouillon | |

| The consumption of: Pulse seeds, kernels, nuts, and their products (dry beans, peas, chickpeas, and lentils) | |

| Usual practice of addition of solid fat after cooking or at the table to a number of commonly | |

| Drinking | Intakes of soft drinks |

| Consumption of energy drink | |

| The frequency of intake low-fat milk | |

| Consumption of the milkshake | |

| The consumption of: Beverages (no milk) | |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Caffeinated drinks | |

| Set meals | Consumption frequency |

| Time of day eating: Breakfast, mid-morning, lunch, mid-afternoon, dinner, late evening, and extras | |

| Dietary intake of participants with low and high adherence to Mediterranean diet | |

| Consumption of breakfast | |

| Regularity of breakfasts | |

| Meals ratio per day | |

| Food preparation methods | |

| Fluid and diet supplements during the day | |

| Calorie intake | Major type of ages |

| Daily consumption of carboxymethyl-lysine | |

| Calorie intake | |

| Protein intakes | |

| Amount of cooked rice | |

| Total fat intake | |

| High potato intakes | |

| Carbohydrate intakes | |

| Total energy intake | |

| Fasting duration (dichotomized as≥12 or<12 h) | |

| Mindful eating | Mindfulness |

| Eating out | |

| Eating both rapidly and until feeling full | |

| Eating rapidly only | |

| Not eating rapidly | |

| Psychological distress | |

| Emotional eating | |

| Food safety | Usage of school cafeteria |

| Hot meal intakes | |

| Inhibition and abstinent | Hunger |

| Eating until feeling full only | |

| Not eating until feeling full | |

| Dietary restraint | |

| External based | |

| Consumed foods (pancakes, waffles, French toast, potatoes, rice, and pasta) | |

| Eating together | Dining with others |

As shown in Table 3, the relation between food choices and metabolic indices is more frequent in studies. While, inhibition and abstinent and eating together were two behavioral sets with the smallest share of research. Anthropometric indices have the highest rate in the evaluations, namely 11%–100% of studies assessed at least one anthropometric index. Food choice as one of the behavioral categories, with the highest relative frequency, gets 26% of anthropometric indices.

Table 3.

The absolute and relative frequency of metabolic indices measured in dietary/nutritional behavior categories

| Nutritional behavior | Metabolic indices (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein and acid amine | Glycemic profile | Lipid profile | Vital signs | Anthropometric indices | Hormones | Diseases | Other | Total | |

| Food choice | 99 (19.5) | 40 (8) | 90 (17.5) | 39 (7.5) | 135 (26.5) | 12 (2.3) | 5 (1) | 90 (17.5) | 510 (100) |

| Drinking | 2 (3) | 5 (8) | 16 (26) | 8 (13) | 23 (38) | 0 | 2 (3) | 5 (8) | 61 (100) |

| Set meals | 34 (28) | 9 (7.5) | 17 (14) | 7 (6) | 26 (21.5) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (1.6) | 24 (20) | 121 (100) |

| Calorie intake | 68 (31) | 14 (6) | 27 (12) | 15 (7) | 28 (12.5) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (1) | 64 (29) | 221 (100) |

| Mindful eating | 0 | 1 (2) | 11 (24) | 5 (11) | 15 (32.5) | 2 (4.34) | 9 (19.5) | 3 (6.5) | 46 (100) |

| Food safety | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (100) |

| Inhibition and abstinent | 0 | 1 (3) | 4 (13) | 2 (6.5) | 13 (42) | 2 (6.5) | 6 (19) | 3 (10) | 31 (100) |

| Eating together | 0 | 2 (12.5) | 6 (37.5) | 1 (6.25) | 7 (44) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (100) |

| Total count | 203 | 72 | 171 | 77 | 259 | 21 | 26 | 189 | |

Discussion

In this study, the authors investigated all the 10-year relevant original articles in the field of nutrition/dietary behavior-metabolic axis. The literature overview shows that the majority of the researchers have focused on the nutritional contents and its other aspects such as nutritional/dietary behaviors, which can affect metabolic status, have been less considered.

Nutritional behaviors more relevant to the type of food choice behaviors such as eating fast food, cooking with available ingredients, meat-only diet, the consumption of crustaceans, and the family of Lobsters and crabs were placed in this category.

Several studies have focused on these behaviors and their metabolic effects. In some studies, healthy food choice was associated with a reduction in the risk of developing metabolic diseases and normal body mass index (BMI).[17,31,32,34] In a study by Ahn et al., the consumption of rice among 26,006 Korean volunteers was examined, and the results showed that rice consumption with green vegetables, especially in postmenopausal women, has a role in reducing the risk of developing MetS.[6] However, there are some controversies in these relations. In a study done by Bloomer et al. on the Daniel's diet (rich in whole vegetables and fruits), no statistically significant reduction was shown on the oxidative stress.[28]

The behaviors included in drinking category are nonalcoholic and alcoholic beverage intake, milk consumption, etc., These behaviors have been studied in five researches; withal mostly, their impact on lipid and glycemic profile was assessed.

For instance, Korean researchers conduct an investigation on adult women and found that the high levels of soft drink consumption can be important for the risk of Met.[34] In another study conducted by Al-Haifi et al., the association of sweet and nonalcoholic beverages with BMI was examined, and the findings shows that controlling this behavioral pattern has a more effective role on BMI than physical activity.[9]

The set of nutritional behaviors included the hours during a day spent on eating, the number of meals, eating breakfast or not, and so on, which have been considered as set meals. These behaviors and their impact on 34 metabolic indices related to protein and amino acid have been studied so far. Most of these researches show the positive effect of recommended proper set meals (e. g., eating all three daily meals, especially breakfast) on metabolic indices. Eating breakfast is one of the most effective behaviors, and there are several works in this issue.[11,19,24,25,26] This behavior has a significant effect on the reduction of BMI and the risk of developing MetS. Furthermore, avoidance of eating breakfast, which increases insulin resistance, can also increase hunger and reduce the feeling of satiety.[8,18] Thomas et al. detected that a short-term change in set meal habits would have a negative effect on metabolic indices.[18] Beside, Alexandrove et al. led an investigation on 10–17 youths, and their work showed that eating breakfast (as a primer meal) could prevent obesity.[8] In another study, it is found that eating habits (such as skipping or eating breakfast) have a greater impact on changes in body mass in contrast with physical activity.[9]

The majority of the investigations focus on calorie intake. This behavior category consists of the total sugar, carbohydrate and fat consumption, and related topics. Studies in this area have found that controlling the input calorie can help to reduce harmful metabolic parameters.[25,28,29] In these studies, the change in nutritional behaviors for the control of calorie intake would help to improve overall health. It also plays an important role in the regulation of intestinal microbes, which is theoretically related to the probability of developing future chronic diseases.

Mindful eating behavior is only addressed by three studies. This category involves fast eating, eating consciously (avoid doing something else while eating and being fully focused on eating) and eating emotionally. These studies have suggested that eating consciously as a behavior helps to reduce abdominal fat and metabolic risk factors as well as a great influence on the individual weight gain.[19,20,30]

Food safety is another set of nutritional behaviors which only one research runs with this concept. This set of behaviors includes avoiding the hot food and the school cafeteria. The results showed a significant effect of these behaviors on the reduction of metabolic risk factors.[8]

Inhibition and abstinent behaviors include habits that help the individual control their appetite and behaviors that somehow play a role in inhibitory functions. Hunger, dietary restraint, eating until feeling full, and external based (responding to exogenous stimuli), such as the smell and appearance of food, are among those behaviors that fall into this set. In studies that examined these behaviors, it has been observed that adopting a proper pattern of inhibition and abstinent has a significant effect on the reduction of the risk of metabolic diseases and their risk factors.[20,30,31]

Eating together consists of several behaviors such as eating with friends, eating with family, sharing food, and eating in parties. Nevertheless, there are few evidences in this set of behaviors. In a study conducted by Choi et al., 29 participants with more than one metabolic risk factor were dining with others, and the participants were found to have a significant reduction in weight, wrist size, and BMI during 16 weeks. However, other interventions have been designed in addition to eating together in their study.[33,37]

It could be concluded that most of the studies have focused on investigating the association between food choices and anthropometric indices, and the least studies have been done on the relationship between the concentration of nutritional hormones and behaviors such as drinking and eating habits. Although it was expected that the association of calorie intake with all metabolic indices has been checked out, only half of the studies examined this nutritional behavior. The authors could not find more related literatures considering the associations of metabolic diseases and “making safe food choices” as well as “eating together” behaviors, and the association of inhibition and abstinent eating behaviors has been investigated in few studies. Furthermore, there is a dearth in research on glycemic, lipid, and amino acid profiles, and behaviors such as eating together and eating safe food (for example, refusing to consume hot foods) are among the areas that have been less explored by researchers.

Conclusion

Assessing the relation between nutritional behavior/eating habits and metabolic indices leads to new search fields in behavioral interventions. The essential goal in these interventions is to promote metabolic status and decrease metabolic disorder incidences. Accordingly, finding the links between nutritional behavior and metabolic indices will be the key point in selecting the different types of interventions. The results of these studies will guide therapists to the accurate recognition of metabolic effects in targeting behavior for their intervention. In addition, these results will be a proper field for boosting metabolic health.

Furthermore, detecting the relations between nutritional behaviors and metabolic indices will be a vital point for policymaking and designing social interventions. Finding these relations could prioritize the selected behaviors for interventions in population level. As may be expected, the selected behaviors for population-wide interventions should have the maximum effect on metabolic indices. In addition, the result will help to find the effective behaviors in this regard.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute (grant no. 1396-02-98-2186), Tehran University of Medical Science.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mrs. Ghobadi and other staff of Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute for their nice cooperation in this project.

References

- 1.Sherling DH, Perumareddi P, Hennekens CH. Metabolic syndrome. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2017;22:365–7. doi: 10.1177/1074248416686187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansarimoghaddam A, Adineh HA, Zareban I, Iranpour S, HosseinZadeh A, Kh F. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Middle-East countries: Meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Suwaidi J, Zubaid M, El-Menyar AA, Singh R, Rashed W, Ridha M, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with acute coronary syndrome in six middle eastern countries. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2010;12:890–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00371.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashraf H, Rashidi A, Noshad S, Khalilzadeh O, Esteghamati A. Epidemiology and risk factors of the cardiometabolic syndrome in the Middle East. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;9:309–20. doi: 10.1586/erc.11.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pérez-Martínez P, Mikhailidis DP, Athyros VG, Bullo M, Couture P, Covas MI, et al. Lifestyle recommendations for the prevention and management of metabolic syndrome: An international panel recommendation. Nutr Rev. 2017;75:307–26. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn Y, Park SJ, Kwack HK, Kim MK, Ko KP, Kim SS. Rice-eating pattern and the risk of metabolic syndrome especially waist circumference in Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) BMC Public Health. 2013;13:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Daghri NM, Khan N, Alkharfy KM, Al-Attas OS, Alokail MS, Alfawaz HA, et al. Selected dietary nutrients and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in adult males and females in Saudi Arabia: A pilot study. Nutrients. 2013;5:4587–604. doi: 10.3390/nu5114587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexandrov AA, Poryadina GI, Kotova MB, Ivanova EI. The specificity of schoolchildren's eating habits in Moscow and Murmansk. Voprosy Pitaniia. 2014;83:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Haifi AR, Al-Fayez MA, Al-Athari BI, Al-Ajmi FA, Allafi AR, Al-Hazzaa HM, et al. Relative contribution of physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and dietary habits to the prevalence of obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34:6–13. doi: 10.1177/156482651303400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkins JL, Whincup PH, Morris RW, Lennon LT, Papacosta O, Wannamethee SG. Dietary patterns and the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality in older British men. Br J Nutr. 2016;116:1246–55. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516003147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbaresko J, Siegert S, Koch M, Aits I, Lieb W, Nikolaus S, et al. Comparison of two exploratory dietary patterns in association with the metabolic syndrome in a Northern German population. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:1364–72. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514002098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiBello, Julia R, Stephen T. McGarvey, Peter Kraft, Robert Goldberg, Hannia Campos, et al “Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic syndrome in adult Samoans”. The Journal of nutrition 139. 2009;10:1933–43. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.107888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruger R, De Bray JG, Beck KL, Conlon CA, Stonehouse W. Exploring the relationship between body composition and eating behavior using the three factor eating questionnaire (TFEQ) in young New Zealand Women. Nutrients. 2016;8:(386–397). doi: 10.3390/nu8070386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardi V, Leppanen J, Treasure J. The effects of negative and positive mood induction on eating behaviour: A meta-analysis of laboratory studies in the healthy population and eating and weight disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;57:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Strien T, Konttinen H, Homberg JR, Engels RC, Winkens LH. Emotional eating as a mediator between depression and weight gain. Appetite. 2016;100:216–24. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vartanian LR, Porter AM. Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite. 2016;102:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh SD, Muto T, Murase T, Tsuji H, Arase Y. Eating until feeling full and rapid eating both increase metabolic risk factors in Japanese men and women.Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:1266–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas EA, Higgins J, Bessesen DH, McNair B, Cornier MA. Usual breakfast eating habits affect response to breakfast skipping in overweight women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:750–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almoosawi S, Prynne CJ, Hardy R, Stephen AM. Time-of-day and nutrient composition of eating occasions: Prospective association with the metabolic syndrome in the 1946 British birth cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:725–31. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson AL, Harris TB, Tylavsky FA, Perry SE, Houston DK, Hue TF, et al. Dietary patterns and survival of older adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammadi H, Karimifar M, Heidari Z, Zare M, Amani R. The effects of wheat germ supplementation on metabolic profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2020;34:879–85. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alhakbany MA, Alzamil HA, Alabdullatif WA, Aldekhyyel SN, Alsuhaibani MN, Al-Hazzaa HM. Lifestyle habits in relation to overweight and obesity among Saudi women attending health science Colleges. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2018;8:13–9. doi: 10.2991/j.jegh.2018.09.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almanza-Aguilera E, Urpi-Sarda M, Llorach R, Vázquez-Fresno R, Garcia-Aloy M, Carmona F, et al. Microbial metabolites are associated with a high adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern using a 1H-NMR-based untargeted metabolomics approach. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;48:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angoorani P, Ejtahed HS, Mirmiran P, Mirzaei S, Azizi F. Dietary consumption of advanced glycation end products and risk of metabolic syndrome. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2016;67:170–6. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2015.1137889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajaber AS, Abdelkarem HM, El-Mommten AM. Dietary approach and its relationship with metabolic syndrome components. Int J Pharm Technol Res. 2016;9:237–46. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bajerska J, Woźniewicz M, Suwalska A, Jeszka J. Eating patterns are associated with cognitive function in the elderly at risk of metabolic syndrome from rural areas. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:3234–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bean MK, Mazzeo SE, Stern M, Evans RK, Bryan D, Ning Y, et al. Six-month dietary changes in ethnically diverse, obese adolescents participating in a multidisciplinary weight management program. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011;50:408–16. doi: 10.1177/0009922810393497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bloomer RJ, Trepanowski JF, Kabir MM, Alleman RJ, Jr, Dessoulavy ME. Impact of short-term dietary modification on postprandial oxidative stress. Nutr J. 2012;11:16. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burkert NT, Freidl W, Großschädel F, Muckenhuber J, Stronegger WJ, Rásky E. Nutrition and health:Different forms of diet and their relationship with various health parameters among Austrian adults. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2014;126:113–8. doi: 10.1007/s00508-013-0483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro MA, Baltar VT, Marchioni DM, Fisberg RM. Examining associations between dietary patterns and metabolic CVD risk factors: A novel use of structural equation modelling. Br J Nutr. 2016;115:1586–97. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan R, Chan D, Lau W, Lo D, Li L, Woo J. A cross-sectional study to examine the association between dietary patterns and risk of overweight and obesity in Hong Kong Chinese adolescents aged 10-12 years. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33:450–8. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2013.875398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang AR, Grams ME. Serum phosphorus and mortality in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III): Effect modification by fasting. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:567–73. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi J, Se-Young O, Lee D, Tak S, Hong M, Park SM, et al. Characteristics of diet patterns in metabolically obese, normal weight adults (Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 2005) Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22:567–74. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi Y, Lee MJ, Kang HC, Lee MS, Yoon S. Development and application of a web-based nutritional management program to improve dietary behaviors for the prevention of metabolic syndrome. Comput Inform Nurs. 2014;32:232–41. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung S, Ha K, Lee HS, Kim CI, Joung H, Paik HY, et al. Soft drink consumption is positively associated with metabolic syndrome risk factors only in Korean women: Data from the 2007-2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Metabolism. 2015;64:1477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht FM, Maninger N, Kuwata M, Jhaveri K, et al. Mindfulness intervention for stress eating to reduce cortisol and abdominal fat among overweight and obese women: An exploratory randomized controlled study. J Obes. 2011;2011:651936. doi: 10.1155/2011/651936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kant AK, Leitzmann MF, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Patterns of recommended dietary behaviors predict subsequent risk of mortality in a large cohort of men and women in the United States. J Nutr. 2009;139:1374–80. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim CK, Kim HJ, Chung HK, Shin D. Eating alone is differentially associated with the risk of metabolic syndrome in korean men and women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1020–1034. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15051020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miguet M, Masurier J, Chaput JP, Pereira B, Lambert C, Dâmaso AR, et al. Cognitive restriction accentuates the increased energy intake response to a 10-month multidisciplinary weight loss program in adolescents with obesity. Appetite. 2019;134:125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin A, Lim SY, Sung J, Shin HR, Kim J. Dietary intake, eating habits, and metabolic syndrome in Korean men. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:633–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sierra-Johnson J, Undén AL, Linestrand M, Rosell M, Sjogren P, Kolak M, et al. Eating meals irregularly: A novel environmental risk factor for the metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1302–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Son H, Kim H. Influence of living arrangements and eating behavior on the risk of metabolic syndrome: A national cross-sectional study in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:919–929. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16060919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tao L, Yang K, Huang F, Liu X, Li X, Luo Y, et al. Association between self-reported eating speed and metabolic syndrome in a Beijing adult population: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:855. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5784-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]