Abstract

Implications

In this commentary, we describe the evidence-based approach used to identify the primary cause of EVALI and to curb the 2019 outbreak. We also discuss future research opportunities and public health practice considerations to prevent a resurgence of EVALI.

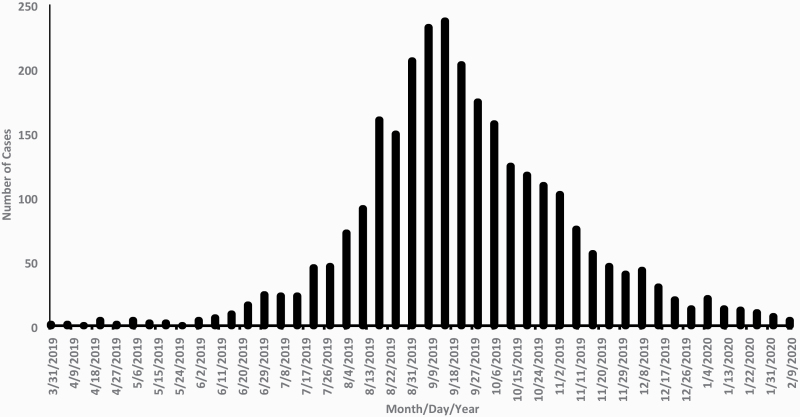

In August 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), state and local health departments, and other clinical and public health partners began investigating a multistate outbreak of severe lung injuries that were first identified in July 2019 in Wisconin and Illinois among persons with a reported history of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use.1 An ensuing investigation focused on understanding the extent, characteristics, and causes of this novel clinical syndrome, which was subsequently termed e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI). As of February 18, 2020, a total of 2807 hospitalized EVALI cases were reported to CDC from all 50 states, DC, and two US territories; 68 deaths were confirmed in 29 states and DC.2 National emergency department data and active case reporting from state health departments documented a sharp increase in EVALI cases in August 2019, with case counts peaking in September 2019 and then steadily declining through early 2020 (Figure 1).3,4 In this commentary, we describe the evidence-based approach used to identify the primary cause of EVALI and to curb the 2019 outbreak. We also discuss future research opportunities and public health practice considerations to prevent a resurgence of EVALI.

Figure 1.

Dates of symptom onset and hospital admission for patients with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury—United States, March 31, 2019–February 15, 2020.

Evidence-Based Approach to Identify the Primary Cause of EVALI

Following the identification of an initial cluster of cases, a comprehensive, systematic, and interdisciplinary approach was used to investigate EVALI—integrating clinical, epidemiologic, and laboratory data. Preliminary reports from state health department investigations and published case series described the clinical features of EVALI cases.1 According to these reports, the onset of respiratory symptoms appeared to occur over several days to several weeks before hospitalization; gastrointestinal and constitutional symptoms, such as fever, were also commonly reported.1,5,6 Patients frequently required respiratory support therapies ranging from supplemental oxygen to endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.1,5,6 All patients reported a history of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use, and there was no evidence of infectious etiology, suggesting the cause could be a chemical exposure.1

These clinical data subsequently helped inform the development of a standardized case definition and case report form by state health departments, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, and CDC, which enabled epidemiologic data to be collected on the characteristics of EVALI cases. These epidemiologic data indicated that approximately three quarters of EVALI patients were less than 35 years of age and more than 80% reported using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products with or without nicotine-containing products.5,7 Subsequent national and state-based studies reinforced that most EVALI patients reported using THC-containing products8; these products were primarily obtained from informal sources such as family, friends, or online or in-person dealers9; and that “dank vapes,” a class of largely counterfeit products, were the most commonly reported THC-containing branded products among EVALI patients.9,10 Analyses by geography showed that following the first reported cases of EVALI in Wisconsin and Illinois in July 2019, cases were subsequently reported in all 50 states, DC, and two US territories. There were minimal international cases, and geographically distal areas in the United States—including Alaska and Puerto Rico—were the last to report them domestically, indicating the outbreak likely originated in the contiguous United States.5,11,12

The epidemiologic data informed the development of novel laboratory methods to identify potential toxicants of concern in THC-containing products that may be implicated in EVALI. Analyses of THC-containing product samples by FDA and state health laboratories identified potentially harmful constituents, such as vitamin E acetate, medium-chain triglyceride oil, and other lipids.2,13 To better characterize exposure among EVALI patients, CDC developed and validated isotope dilution mass spectrometry methods to analyze specific toxicants in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples at the site of injury. The first study employing this method detected vitamin E acetate in all 29 patient bronchoalveolar lavage samples.13 These findings were confirmed in a subsequent study, which found vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid obtained from 48 of 51 EVALI case patients from 16 states, but not in a control group without EVALI; no other priority toxicants were found in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients or controls, except for coconut oil and limonene, which were found in one patient each.14 This was the first reported identification of a potential toxicant of concern in biologic specimens obtained from EVALI patients and provided direct evidence of vitamin E acetate as the primary cause of EVALI. Additional support implicating vitamin E acetate as a primary cause of EVALI came from an animal model; mice exposed to inhaled vitamin E acetate were found to have numerous laboratory test markers consistent with EVALI.15

Although vitamin E acetate is strongly associated with EVALI, evidence is not sufficient to rule out the contribution of other chemicals of concern; specifically, epidemiologic data have continued to show that approximately 20% of EVALI patients report exclusive use of nicotine-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products,3,5,7,8 which might be due to multiple factors. For example, some patients might not accurately report, or know the content of, THC or other compounds in the products they have used; or some cases might be misclassified due to the broad EVALI case definition, which could lead to the inclusion of some patients who do not have EVALI. Alternatively, these patients might be accurately reporting exclusive use of nicotine-containing products. A study of 121 Illinois EVALI patients found that 17 (14%) reported using only nicotine-containing products, including nine (7%) with no indication of any THC use based on self-report and toxicology testing.16 Additionally, an analysis of emergency department visits associated with EVALI from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program found a gradual increase in the incidence of visits associated with EVALI from January 2017 to June 2019, especially among young people.3,4 This suggests an ongoing baseline level of lung injuries consistent with EVALI were occurring before the recognized outbreak in summer 2019; these emergency department visits could include sporadic cases related to vitamin E acetate before it became more commonly used, or alternatively, may be due to other substances, including those in non-THC-containing products.3,4 Taken together, these findings reinforce that vitamin E acetate is strongly linked with EVALI, although evidence is not sufficient to rule out the contribution of other chemicals of concern, including chemicals in either THC or non-THC-containing products, in some reported EVALI cases.2

Future Research Opportunities

Additional research can inform efforts to prevent future EVALI cases and to better understand the long-term impact of EVALI at the individual and population levels.17 National registries of EVALI patients have been proposed for researchers to identify those affected, along with longitudinal studies to assess both the short- and long-term health outcomes of EVALI patients.17 Additional studies to examine the aerosols and gases generated by EVALI case-associated product fluids, and the respiratory effect of inhaling aerosolized vitamin E acetate, are in progress. 14,17 It also remains important to better understand other potential causes of lung injury besides vitamin E acetate. For example, systemic and comprehensive laboratory-based studies into the toxicology and health effects of THC-containing products may provide additional insights into the etiology of EVALI-related outcomes. It is also possible that current or future toxicants used as additives in THC-containing products, aside from vitamin E acetate, could lead to EVALI-like lung injuries. The contributing cause or causes of EVALI for patients reporting exclusive use of nicotine-containing products also warrants further investigation.

Public Health Practice Considerations

EVALI cases have declined considerably since peaking in September 2019.2 This decrease is likely driven by multiple factors, including increased public awareness of the risks associated with THC-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, product use following the nationwide public health response and its communication; removal of vitamin E acetate from some products; and law enforcement actions related to illicit products.2 Additionally, some states with legal marijuana markets established laws to limit the use of additives in THC-containing products.18 EVALI also prompted numerous public health advisories at the national, state, and local levels, as well as some state-level restrictions on the sale of certain types of e-cigarette, or vaping, products.19

The focus and scope of actions needed to address EVALI must be grounded in science and target the underlying drivers of the outbreak.20 Importantly, the factors driving EVALI are distinct from those driving the concurrent youth e-cigarette use epidemic in the US. EVALI has primarily occurred among young adults and is largely driven by the use of THC-containing products from informal sources, most notably those containing vitamin E acetate.20 In contrast, the youth e-cigarette use epidemic has occurred among those less than 18 years and is driven by the use of nicotine-containing products from formal sources (eg, commercial retailers), which has been fueled by multiple factors that enhance the appeal and availability of these products to young people.20

Strategies for continuing to address EVALI include timely diagnosis and treatment by health care providers, public health messages to raise awareness about the risks, and ensuring that chemicals of concern are not introduced into the supply chain. Continued surveillance of EVALI cases is also critical and presently underway, including through existing platforms such as CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance Program. Taken together, these efforts can help clinicians, researchers, and public health practitioners promptly identify, prevent, and respond to future outbreaks of EVALI or similar illnesses.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Funding

None declared.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Schier JG, Meiman JG, Layden J, et al. Severe pulmonary disease associate with electronic cigarette product use – interim guidance. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(36):787–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-cigarette, or Vaping, Products www.cdc.gov/EVALI. Accessed August 24, 2020.

- 3. Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force Update: Characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury – United States, August 2019–January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(3):90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, Patel MT, et al. Syndromic surveillance for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):766–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, Kimball A, Layer M, et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin – final report. N Eng J Med. 2020;382;903–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siegel DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group Update: Interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury – United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(41):919–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perrine CG, Pickens CM, Boehmer TK, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group Characteristics of a multistate outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping – United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(39):860–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moritz ED, Zapata LB, Lekiachvili A, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force Update: Characteristics of patients in a national outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injuries – United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(43):985–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Navon L, Jones CM, Ghinai I, et al. Risk factors for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) among adults who use e-cigarette, or vaping, products – Illinois, July-October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghinai I, Pray IW, Navon L, et al. E-cigarette product use, or vaping, among persons with associated lung injury – Illinois and Wisconsin, April–September 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(39):865–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lozier MJ, Wallace B, Anderson K, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force Update: Demographic, product, and substance-use characteristics of hospitalized patients in a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injuries – United States, December 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(49):1142–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ellington S, Salvatore PP, Ko J, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force Update: Product, substance-use, and demographic characteristics of hospitalized patients in a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury – United States, August 2019–January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(2):44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Morel-Espinosa M, et al. Evaluation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients in an outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury – 10 States, August–October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1040–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Laboratory Working Group Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhat TA, Kalathil SG, Bogner PN, Blount BC, Goniewicz ML, Thanavala YM. An Animal model of inhaled vitamin E acetate and EVALI-like lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1175–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghinai I, Navon L, Gunn JKL, et al. Characteristics of persons who report using only nicotine-containing products among interviewed patients with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury – Illinois, August–December 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(3):84–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crotty Alexander LE, Ware LB, Calfee CS, Callahan S, Eissenberg, et al. NIH Workshop Report: E-Cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI): Developing a research agenda. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(6):795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Conference on State Legislatures. State Medical Marijuana Laws https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx. Accessed August 25, 2020.

- 19. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. States & Localities that Have Restricted the Sale of Flavored Tobacco Products https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0398.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2020.

- 20. King BA, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Briss PA. The EVALI and youth vaping epidemics – implications for public health. N Eng J Med. 2020:382;689–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.