Introduction

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is the most abundant serum protein found in the human fetus, produced by the yolk sac and the liver [1]. The levels of maternal serum AFP reach a peak value at ∼28–32 weeks of gestation and decrease rapidly after birth and usually drop to the normal at 8–12 months of age. The normal serum AFP level for an adult is <20 ng/mL [2]. In contrast, liver-tumor cells usually synthesize and secrete an increased level of AFP. Abdominal ultrasound and AFP are generally recommended as the screening modality for HCC for patients at risk for development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. AFP-L3, an isoform of AFP that binds Lens culinaris agglutinin, can be particularly useful in the early identification of aggressive HCC [2]. These assays, however, can generate false-positive and false-negative AFP values. Of patients with advanced HCC, ∼20% had normal AFP levels, whereas some patients with liver diseases had significant AFP elevation without liver cancer in long-term surveillance [3]. Elevated AFP levels could be associated with active liver diseases with hepatocyte regeneration [4, 5]. In that setting, the AFP level will decline with improvement of the underlying liver condition. Our case illustrated the dilemma and uncertainties as a result of persistent abnormal AFP values after extensive clinical investigations.

Case presentation

The patient is a 53-year-old Chinese female with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and was antiviral-treatment-naive. She had a strong family history of hepatitis B but no liver cancer. Her only other past medical problems were childhood rheumatic fever and a uterine fibroid. She was first noted as having an asymptomatic elevation of AFP to 1,156 ng/mL when she had her blood tests performed in a new clinic. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not reveal any focal hepatic lesion. The patient was very depressed and anxious about the elevated AFP value and its clinical implications despite her normal MRI. She experienced epigastric pain but upper GI endoscopy was entirely normal. She was subsequently evaluated at our Liver Center and repeat AFP remained high at 1,028 ng/mL (Roche Cobas e601). Repeat abdominal MRI reported only a 6-mm hepatic hemangioma. Her serum-aminotransferases and liver-function tests were normal. Fibroscan estimated minimal stage 0/1 hepatic fibrosis. Embryonic, non-germ-cell tumors of the genitourinary tract and pregnancy were ruled out. CEA, CA19-9, CA125, and HCG were in the normal range.

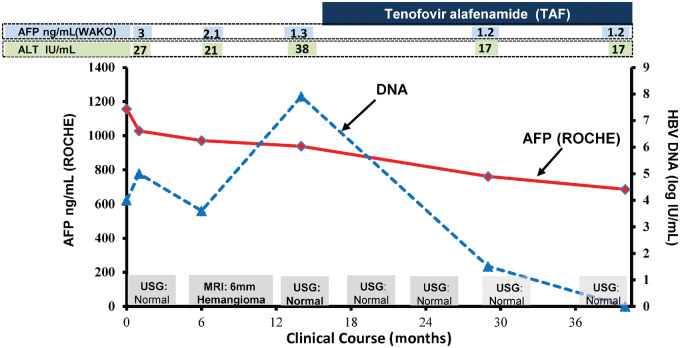

Interestingly, her same-day blood sample yielded a normal AFP value of 3 ng/mL by the Wako uTAS Assay performed at Quest Diagnostics. AFP-L3 was also normal. Repeat testing over 1 year continued to report significantly elevated AFP levels by the Roche assay and normal values by the Wako platform (Figure 1). Serial abdominal ultrasound examinations remained normal.

Figure 1.

Clinical course and AFP levels of the patient over 36 months. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; USG, ultrasonograph; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

At her 15-month follow-up visit, her HBV DNA increased to 7.8 from 4 log IU/mL with elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 38 IU/L. She was subsequently started on tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) 25 mg daily that resulted in optimal HBV DNA suppression to an undetectable level and her ALT normalized. Of note, her AFP pattern remained constant regardless of her hepatitis B disease states and antiviral therapy (Figure 1).

We further evaluated her stored serum samples by three other assay platforms and they again reported discordant results (Table 1). Abbott Architect and Beckman-Coulter Dxl yielded similar elevated AFP results as Roche. Siemens Immulite 2000 reported normal AFP as by the Wako instrument. Assay interference was systematically evaluated by both local and national laboratories but was not confirmed definitively.

Table 1.

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) results (ng/mL) based on different immunoassay platforms

| Time for sample testing | Immunoassay platform |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roche Cobas E601 | Wako UTAS | Abbott Architect | Beckman-Coulter Dxl | Siemens Immulite | |

| Baseline | 1,028 | 3 | – | 1,162 | 3.42 |

| 6 months | 971.2 | 2.1 | – | – | – |

| 12 months | 938.2 | 1.3 | – | – | – |

| 27 months | 761.1 | 1.2 | 802 | – | – |

| 39 months | 685.6 | 1.2 | – | – | – |

Discussion

There are a number of lessons to learn from this unusual case of elevated AFP. Elevated AFP may be associated with germ-cell or non-germ-cell tumors such as ovarian serous carcinoma, ovarian clear-cell carcinoma, fallopian-tube, endometrioid, vagina, and vulva carcinomas [6]. Some gastrointestinal tumors such as gastric cancers could secrete AFP and are associated with more aggressive growth [7]. In our case, we systematically ruled out all the possible conditions that can result in falsely elevated AFP.

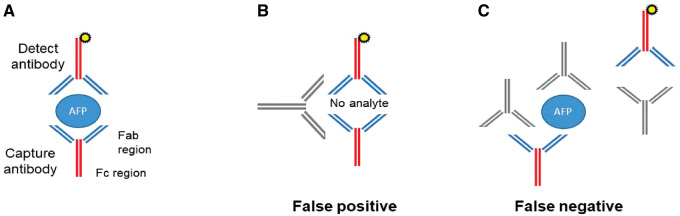

While diagnostic assays are valuable for medical practice, they have limitations. All five AFP assays we evaluated are immunoassays (Figure 2A) and thus susceptible to interference by heterophile antibodies [8]. Heterophilic antibodies can cause nonspecific false-positive results by bridging the capture and the detection of antibodies in immunoassays (Figure 2B). Extensive ancillary tests were performed to evaluate for heterophile antibodies in this case. The clinical samples were run with various Scantibodies heterophilic-blocking reagents as well as with serial dilutions using polyclonal total mouse serum in an attempt to remove or dilute potential interfering antibodies. The resulting AFP values, however, remained significantly elevated. The lack of correction with Scantibodies and mouse-serum experiments argues against false-positive results with heterophile antibodies but other interfering antibodies remain a possibility.

Figure 2.

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) assays are susceptible to interference by heterophile antibodies. (A) Conventional two-site sandwich ELISA measures AFP levels by detecting reactivity with two anti-AFP antibodies. (B) Interfering antibodies that bind capture and detect reagents can cause false-positive results. These interfering substances can be anti-mouse heterophilic antibodies directed against the Fc region of the capture and detect reagents. (C) Interfering antibodies can inhibit reactivity of the ELISA by binding to the analyte or capture and/or detect reagents, preventing the capture and detect antibodies from simultaneously interacting with the analyte and causing a false-negative result.

The AFP results were normal with the Wako uTAS and Siemens Immulite platforms. To evaluate a possible hook effect [9] that might cause a low AFP value in the setting of a high analyte concentration, the sample was diluted 100-fold and reanalysed using the Siemens instrument. The AFP level was undetectable in the diluted sample, thus ruling out a hook effect. The decreased AFP results could theoretically be secondary to endogenous anti-AFP antibodies [ 9,10] blocking the epitopes required for interaction between the capture and detect reagents (Figure 2C). The presence of anti-AFP antibodies, however, is unlikely, since two independent assay platforms yielded normal AFP values.

In summary, we presented an atypical case of a significantly elevated AFP level in a patient with chronic hepatitis B. It underscores the limitation of the AFP assay as a HCC screening tool. Even though the exact nature of the elevated AFP levels remains unknown, the uneventful prolonged follow-up beyond 3 years and lack of correlations with the patient’s HBV status argue strongly against a pathological etiology. In the setting of an unexplained diagnostic-test finding, it is informative to apply multiple test platforms to unmask potential discordant results in order to avoid unnecessary medical evaluations.

Authors’ contributions

D.T.Y.L. provided care and evaluation of the patient, key role in writing and editing the manuscript. P.A.S. played significant role in manuscript writing. A.O. and A.Z.H. provided systematic evaluations of the AFP assay and contributed to manuscript writing. R.I., M.H.M., K.J.C.R. assisted with manuscript writing, editing and detailed search of references. S.S.P. provide patient care and manuscript editing.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Gogel BM, Goldstein RM, Kuhn JA. et al. Diagnostic evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cirrhotic liver. Oncology (Williston Park) 2000;14:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leerapun A, Suravarapu SV, Bida JP. et al. The utility of Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive alpha-fetoprotein in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: evaluation in a United States referral population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Di Bisceglie AM, Sterling RK, Chung RT. et al. Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with advanced hepatitis C: results from the HALT-C Trial. J Hepatol 2005;43:434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Collier J, Sherman M.. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 1998;27:273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sterling RK, Wright EC, Morgan TR. et al. Frequency of elevated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) biomarkers in patients with advanced hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. El-Bahrawy M. Alpha-fetoprotein-producing non-germ cell tumours of the female genital tract. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:1317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bei R, Budillon A, Reale MG. et al. Cryptic epitopes on alpha-fetoprotein induce spontaneous immune responses in hepatocellular carcinoma, liver cirrhosis, and chronic hepatitis patients. Cancer Res 1999;59:5471–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sturgeon CM, Viljoen A.. Analytical error and interference in immunoassay: minimizing risk. Ann Clin Biochem 2011;48:418–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gilligan TD, Seidenfeld J, Basch EM. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline on uses of serum tumor markers in adult males with germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3388–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jassam N, Jones CM, Briscoe T. et al. The hook effect: a need for constant vigilance. Ann Clin Biochem 2006;43:314–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]