Abstract

Inflammasomes are innate immune sensors that regulate caspase-1 mediated inflammation in response to environmental, host- and pathogen-derived factors. The NLRP3 inflammasome is highly versatile as it is activated by a diverse range of stimuli. However, excessive or chronic inflammasome activation and subsequent interleukin-1β (IL-1β) release are implicated in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and diabetes. Accordingly, inflammasome inhibitor therapy has a therapeutic benefit in these diseases. In contrast, NLRP3 inflammasome is an important defense mechanism against microbial infections. IL-1β antagonizes bacterial invasion and dissemination. Unfortunately, patients receiving IL-1β or inflammasome inhibitors are reported to be at a disproportionate risk to experience invasive bacterial infections including pneumococcal infections. Pneumococci are typical colonizers of immunocompromised individuals and a leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia worldwide. Here, we summarize the current limited knowledge of inflammasome activation in pneumococcal infections of the respiratory tract and how inflammasome inhibition may benefit these infections in immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors and pyrin domain containing receptor 3, inflammasome, pneumococcus (Streptococcus pneumoniae), respiratory infection, immune response

Introduction

The human innate immunity axis plays a pivotal role in detection of pathogen- or damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs) and contributes to a crucial inflammatory response. To sense PAMPs and DAMPs, innate immune cells express pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). PRRs are classified into five families: Toll-like receptors (TLRs), Nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), Retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG)-I-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors, and Absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptor (ALR) (1). Furthermore, other molecules such as cyclic GMP-AMP synthase can sense pathogen-derived DNA (2). Inflammasomes are one of the most recently discovered classes of NLRs (3).

To date, 22 human NLRs are described. Among them, NLR and pyrin domain containing receptor 3 (NLRP3) is by far the best characterized (4). A wide range of stimuli including bacterial pore forming toxins can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome (5). The subsequent release of interleukins (IL) IL-1β and IL-18 induces a diverse range of protective host pathways aiming to eradicate the pathogen (6). However, uncontrolled and excessive hyper-inflammation can be a driver of several inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (7, 8). Implication of the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases has provided new avenues for designing drugs which target the inflammasome and its signaling cascade. However, it is observed that patients who receive NLRP3 or IL-1β inhibitors are disproportionately susceptible to bacterial infections (9). Therefore, it is of high importance to understand the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in bacterial pathogenesis.

Canonical NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

NLRP3 inflammasome is a multi-protein complex comprising of a sensor NLRP3 protein, an adaptor apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC), and the zymogen procaspase-1 (10). The cytosolic NLRP3 protein contains an N-terminal Pyrin domain (PYD), a central NACHT domain, and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain. The NACHT domain possesses adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) activity and comprises of nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), helical domain 1 (HD1), winged helix domain (WHD) and helical domain 2 (HD2) (11). The ASC domain is a bipartite molecule that contains an N-terminal PYD domain and a C-terminal caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD). Procaspase-1 consists of an N-terminal CARD, a central large catalytic p20 subunit, and a C-terminal small catalytic p10 subunit (12).

In resting macrophages, the NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β concentrations are insufficient to initiate activation of the inflammasome (13). Therefore, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in a two-step process. The first, so called priming step, is initiated via the inflammatory stimuli which are detected by TLRs, tumor necrosis factor receptors (TNFR) or IL-1R. These actions activate downstream the transcription factor NF-κB. NF-κB, in turn, upregulates the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β. In contrast, the priming step does not affect the expression of ASC, procaspase-1 or IL-18 (14–16). Following priming, a second activation step is essential for the assembly of the inflammasome. NLPR3 is highly diverse in nature and a wide range of stimuli can activate it. Common activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome are pathogens (17), extracellular ATP (18), pathogen associated RNA, proteins and toxins (5, 19, 20), heme (21), endogenous factors (amyloid-β, cholesterol crystals, uric acid crystals) (22–24), and environmental factors (silica and aluminum salts) (24, 25). These activators do not directly interact with the inflammasome but rather cause various changes at the cellular level. These include changes in cell volume (26), ionic fluxes (27), lysosomal damage (28), ROS production, and mitochondrial dysfunction (29). The second activation step is essential for cells such as macrophages and epithelial cells. In contrast, human monocytes can release mature IL-1β already after priming (30, 31). Upon activation, oligomerization of the NLRP3 complex occurs via homotypic PYD-PYD interaction of the sensor and adaptor protein, and CARD-CARD interaction of the adaptor and procaspase-1 ( Figure 1 ). Following assembly, recruited procaspase-1 is converted to bioactive caspase-1 through proximity induced auto-proteolytic cleavage (32). Subsequently, caspase-1 cleaves the cytokine precursors pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into mature forms. Simultaneously, caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin-D (GSDMD). After proteolytic cleavage, the C-terminal GSDMD (GSDMD-C) remains in the cytosol, while GSDMD-N anchors the cell membrane lipid. The lipid binding allows GSDMD-N to enter the lipid bilayer. Subsequent GSDMD-N oligomerization within the membrane results in pore formation leading to cell swelling and lysis. The pores serve thereby as protein secretion channels for IL-1β and IL-18. This form of a programmed inflammatory cell death is called pyroptosis (33–35). However, lytic GSDMD-N dependent secretion of IL-1β does not apply universally to all cell types. Studies on neutrophils have shown that GSDMD-N does not localize at the plasma membrane. Instead, it co-localizes with membranes of azurophilic granules and LC3+ autophagosomes resulting in a non-lytic pathway dependent IL-1β secretion which depends on autophagy machinery (36). Alongside with IL-1β, other pro-inflammatory cytokines, eicosanoids, and alarmins are released into the extracellular space. These actions accentuate the inflammatory state by recruiting additional inflammatory immune cells of different lineages (37–39).

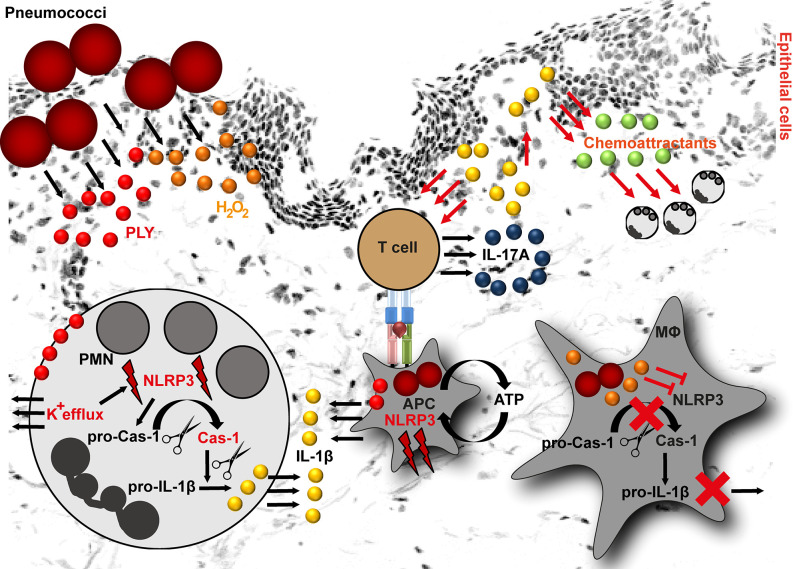

Figure 1.

NLRP3 inflammasome activation by pneumococci. Pneumococci secrete two major virulence determinants: pneumolysin (PLY) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). In neutrophils (PMN), PLY-mediated NLRP3 activation is a result of K+ efflux. K+ efflux activates NLRP3 inflammasome resulting in caspase-1 activation and subsequent cleavage of pro-IL-1β into mature form. In macrophages, PLY-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation is among others dependent on ATP. The released IL-1β stimulates epithelial cells. As a result, they release chemoattractants, including CXCL1 and CXCL2. Both chemokines are involved in processes resulting in neutrophil influx. Furthermore, IL-1β is involved in T helper type 17 cells differentiation and subsequent IL-17A release. In contrast to PLY, H2O2 suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages (MΦ) resulting in pro-IL-1β accumulation in these cells (APC, antigen presenting cell).

Apart from the canonical, non-canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation is described (40). Non-canonical inflammasome activation is triggered by caspases-4/5 in humans (41). However, the noncanonical form can sense only Gram-negative bacteria. Therefore, it potentially does not play a role in Gram-positive bacterial infections (40).

Approved IL-1β Inhibiting Drugs and Their Side-Effects in Patients

NLRP3 inflammasome signaling is implicated in the onset of a number of diseases, including gout (24), atherosclerosis (23), type ІІ diabetes (42, 43), Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS) (44), various types of cancer (45), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (46). In the following, we give just two examples of the role of NLRP3 in auto-inflammatory and auto-immune diseases.

CAPS summarizes three auto-inflammatory diseases caused by mutations in the NLRP3 gene. These include familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS), and neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID). In most cases, CAPS manifests during the childhood and is characterized by spontaneous NLRP3 activation and excessive IL-1β production resulting in frequent episodes of fever, skin rashes, joint and eye inflammation. In severe cases, children can suffer from periorbital edema, amyloidosis, polyarthralgia, growth retardation, and death (47, 48). In vivo studies with transgenic mice expressing the human disease-associated R258W (MWS) or A350V and L351P (FCAS) mutations in the NLRP3 gene demonstrated the detrimental role of IL-1β in these diseases (49, 50). Genetic deletion of the IL-1R efficiently rescued NLRP3A350V and partially NLRP3L351P mice from neonatal lethality (49).

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by persistent synovial inflammation and hyperplasia of the diarthrodial joints and progressive destruction of cartilage and bone (51). In particular, chondrocytes- and monocytes-derived TNF and IL-1β are associated with hyper-inflammatory processes in affected joints (52). At the local level, even low concentrations of IL-1β induce production and secretion of matrix metalloproteinases, which are mainly involved in destructive processes (53). Furthermore, IL‐1β assists in T helper type 17 (Th17) cells differentiation and subsequent IL-17A production. Both processes further contribute to the hyper-inflammatory state of RA (54). These data implicate NLRP3 inflammasome as one of the contributing factors to RA progression. In line with this, several studies have shown that NLRP3 and other inflammasome-related genes are highly upregulated in monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells of RA patients. Furthermore, NLRP3 gene polymorphisms (e.g., rs35829419, rs10754558, rs4612666) were associated with RA manifestation and pathogenesis [reviewed in (55)].

Although the above mentioned diseases affect different organs and are diverse in nature, they are also characterized by a common feature, namely elevated levels of IL-1β. It is of significance to mention that IL-1β release is not limited to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. A variety of mechanisms, including AIM2 inflammasome activation, which also plays a crucial role in bacterial detection, can result in production and release of IL-1β [reviewed in (56)]. Therefore, treatments target various components of the signaling cascade and particularly IL-1. Several strategies that combat IL-1 action have undergone substantial clinical trials. Some of them are summarized in Table 1 . Anakinra, Rilonacept, and Canakinumab are clinically approved IL-1 inhibiting drugs and the best studied agents (73). Anakinra is an IL-1 receptor antagonist and is used among others for the treatment of RA, acute gouty arthritis, and CAPS. It blocks the action of both IL-1α and IL-1β (74–76). Clinical trials with Anakinra reported elevated numbers of infectious episodes in Anakinra-treated patients as compared to the placebo-treated group during the first 6 months of treatment. Furthermore, the incidence of serious infections was increased. These infections comprised mainly of cellulitis, pneumonia, and bone and joint infections as well (57). Rilonacept is a dimeric fusion protein that contains two IL-1 receptors attached to the Fc portion of human IgG1. Similar to Anakinra, it blocks the activity of IL-1 isoforms but does not interact with the IL-1 receptor. Rilonacept is used to treat CAPS and the most reported side-effects include skin reactions and upper respiratory tract infections (58). Canakinumab is a monoclonal IgG1 that specifically targets IL-1β and is commonly used for treatment of Periodic Fever Syndromes, MWS, and acute gouty arthritis (59, 60). Among the various side effects, respiratory tract infections were the most reported side effect in clinical trials (60).

Table 1.

NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors used in clinics.

| Drug | Target | Inhibition mechanism | Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anakinra | IL-1 receptor | IL-1 receptor antagonist | Rheumatoid arthritis, Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome | (57) |

| Rilonacept | IL-1α and IL-1β | IL-1 blocker | Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome | (58, 59) |

| Canakinumab | IL-1β | Monoclonal IgG1 antibody | CAPS and other Periodic Fever Syndromes, active Still’s disease | (59–61) |

| Tranilast* | NACHT domain | Inhibits the NLRP3 oligomerization | Bronchial asthma, atypical dermatitis, allergic conjunctivitis, keloids, and hypertrophic scar | (62) |

| Gevokizumab# | IL-1β | Monoclonal anti-IL-1β antibody | Diabetes, autoimmune disease | (63, 64) |

| LY2189102# | IL-1β | Humanized monoclonal anti-IL-1β antibody | Rheumatoid arthritis, Type 2 diabetes | (65) |

| Glyburide# | ATP-sensitive K+ channels | Indirect inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome | Type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes | (66–68) |

| VX-740# (Pralnacasan) | Caspase-1 | Non-peptide caspase-1 inhibitor | Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis | (69) |

| VX-765# (Belnacasan) | Caspase-1 Caspase-4 | Peptidomimetic metaboliteCaspase-1/4 inhibitor | Rheumatoid arthritis | (70) |

| OLT1177# | NLRP3 ATPase | Blocks NLRP3 ATPase activity, restricts inflammasome activation | Osteoarthritis | (71) |

| AMG108 | IL-1R1 | Human monoclonal IL-1R1-antibody | Osteoarthritis | (72) |

*approved drug but not for NLRP3; #ongoing clinical trials.

All IL-1 inhibiting strategies are well tolerated in the majority of patients. The most common adverse effect is a dose-dependent skin irritation at the injection site. However, a substantially increased incidence of bacterial infections of the respiratory tract caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including pneumococci, Staphylococcus aureus (SA), and/or group A streptococci (GAS) are reported (77). Furthermore, IL-1 inhibiting therapies were associated with a higher incidence of fatal infections as compared to the placebo treated group. Therefore, treatment with IL-1 inhibiting drugs is not recommended for patients with an ongoing infection or with a history of severe infections (59, 77, 78).

Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Pneumococcal Infections

Pneumococci, SA, and GAS are frequent colonizers of the upper respiratory tract (79). Colonization is usually asymptomatic in healthy individuals. However, imbalances in the immune system can lead to severe, invasive and even life-threatening diseases such as pneumonia and sepsis. The occurrence of the more severe forms of infection is commonly found in children younger than 5 years of age, elderly, and immuno-compromised population (80). Due to the immunosuppressive nature of IL-1 inhibiting agents, patients undergoing treatment seem to be at higher risk to develop infections caused by these bacteria (77, 81). In general, inflammation plays a crucial role in infectious diseases. Impaired or insufficient inflammatory response can result in prolonged and/or recurrent infections. In contrast, excessive hyper-inflammation is associated with fatal outcome (82, 83).

Pneumococci colonize the nasopharyngeal cavity of 20%–50% of children and 8%–30% of adults. They have been implicated as the most common etiologic agent of community-acquired pneumonia (80, 84). However, only limited number of studies investigated the role of inflammasome in pneumococcal infections and contrary results are reported. For example, one murine model study reported that NLRP3−/− mice are more susceptible to pneumococcal pneumonia (85). In contrast, a study on pneumococcal meningitis showed that mice with an active NLRP3 signaling have higher clinical scores, suggesting that NLRP3 activation contributes to brain injury (86). Since the incidence of respiratory tract infections is elevated in patient receiving IL-1 inhibiting agent, we will solely focus on the role of NLRP3 in respiratory pneumococcal infections.

Two of the most important secreted pneumococcal virulence determinants are hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin, pneumolysin (PLY) (87). Both factors are implicated in inflammasome activating and suppressive processes. Based on the pneumococcal serotypes used for the infection, the NLRP3-dependent IL-1β secretion by human cells varies. Macrophages infected with serotypes that are associated with invasive diseases and express low/non-hemolytic PLY (serotypes 1, 7F and 8), release lower amounts of IL-1β as compared to macrophages infected with serotypes expressing a fully active PLY (serotypes 2, 3, 6B, 9N) (88, 89). Being poor activators of the inflammasome, the invasive serotypes are potentially less efficiently recognized by the innate immune system and therefore, are less susceptible to immuno-mediated clearance. However, the exact mechanism of NLRP3 activation by PLY is unknown. This process is most likely of indirect nature ( Figure 1 ). Studies on human neutrophils have shown that PLY-mediated NLRP3 activation is a result of potassium ion (K+) efflux. Experimental inhibition of K+ efflux in neutrophils resulted in impaired caspase-1 activation and subsequently in diminished IL-1β processing ( Figure 1 ). Furthermore, it was shown that lysosomal destabilization did not play a role in PLY-mediated IL-1β processing in neutrophils (90). In general, IL-1β induces the production of chemoattractants, such as CXCL1 and CXCL2 by lung epithelial cells, which enhance neutrophil influx (91) and subsequent bacterial clearance at the site of infection (92, 93). Studies on pneumococcal infections of mouse peritoneal neutrophils indicate that NLRP3 inflammasome is mainly responsible for IL-1β secretion, while the AIM2 and NLRC4 inflammasomes are dispensable in these type of immune cells (94). Furthermore, neutrophil-derived IL-1β is involved in activation of Th17 cells. Th17-derived IL-17A acts as an additional chemoattractant-stimulating agent (95, 96) and indirectly mediates neutrophilia in the infected organs ( Figure 1 ) (97). Nonetheless, neutrophil influx alone is not sufficient to clear pneumococci and macrophage influx is essential to ensure bacterial elimination (93, 98). A study by Hoegen and colleagues demonstrated that PLY was a key inducer of NRLP3 inflammasome and IL-1β expression in human differentiated THP-1 cells (86). In contrast to neutrophils, NLRP3 inflammasome activity was dependent on lysosomal destabilization, release of ATP, and cathepsin B activation (86). Furthermore, NLRP3 inflammasome activating synergistic effects of PLY and TLR agonists in dendritic cells and macrophages are reported (85, 88). However, this is rather a general inflammasome activating/priming effect. Apart from NLRP3, PLY can also activate AIM2 inflammasomes (99).

In contrast to PLY, only one study investigated the pneumococci-derived H2O2 and inflammasome interplay. By utilizing mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (mBMDMs), Ertmann and Gekara have shown that mBMDMs infected with pneumococci accumulate large amounts of pro-IL-1β and procaspase-1 (100). Detection of the processed forms of IL-1β and caspase-1 was highly delayed and remained undetectable until 12 h post infection. However, the ratio of processed IL-1β and caspase-1 to their precursors was still very low (100). In contrast, spxB-mutant strain, which lacked H2O2 production, showed an intrinsically increased capacity to activate the inflammasome. The authors suggested that pneumococci employ H2O2-mediated inflammasome inhibition as a colonization strategy (100). Although the study provides highly relevant new insights into pneumococci-host interplay, verification of these results in human host system is warranted. However, host factors upstream or downstream of NLRP3 inflammasome also play a crucial role in colonization and infection processes. Studies in aged mice have suggested that an increase in endoplasmic reticulum stress and enhanced unfolded protein responses contribute to diminished assembly and activation of the NLRP3 resulting in failed clearance of pneumococci (101). In support of this, Krone and colleagues demonstrated that aged mice shows a delayed clearance of pneumococci in the nasopharynx as compared to young mice (102). The authors attributed the observed phenotype to the impaired innate mucosal immune responses in aged mice, including NLRP3 and IL-1β suppression. Furthermore, Lemon and colleagues demonstrated a prolonged colonization of IL1R-/- adult mice as compared to wild-type mice (93). The prolonged colonization was linked to reduced numbers of neutrophils at early stages of infection and reduced macrophage influx at later time points of carriage in IL1R-/- mice (93).

Apart from the bacterial pore-forming toxins, microbial RNA has also been implicated as a direct NLRP3 inflammasome activator (19). Studies showed that even small fragments of staphylococcal or group B streptococcal (GBS) RNA are sufficient for inflammasome activation in human THP-1-derived and mouse macrophages (103, 104). Based on detailed analyses of GBS and mouse macrophages interplay, Gupta and colleagues proposed that bacteria-mediated activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes requires bacterial uptake, phagolysosomal acidification, and toxin-mediated leakage. Subsequently, the free accessible bacterial RNA interacts with NLRP3 and activates the inflammasome cascade (104). Whether such mechanism applies to pneumococcal infections, remains to be elucidated.

In general, tightly controlled inflammasome activation in pneumococcal pneumonia is one of many important host defense mechanisms contributing to bacterial clearance (56). However, excessive NLRP3 activation can also lead to uncontrolled pyroptosis. The disproportionate gasdermin-D mediated cell membrane rupture in a variety of lung cells may result in a release of plethora of alarmins, including processed antigens, ATP, HMGB1, reactive oxygen species, cytokines, and chemokines (105). These prompt an immediate reaction from resident and recruited immune cells leading to a pyroptotic chain reaction with subsequent excessive tissue pathology (106). Furthermore, pathogen-associated antigens might disseminate to other organs resulting in a severe systemic hyper-inflammatory response (105). Whether such actions apply to pneumococcal pneumonia remains to be shown.

Conclusion

Besides the crucial role of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in inflammation, many studies implicate NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathology of several autoimmune and auto-inflammatory disorders. Currently, the most common therapy for such diseases involves the use of immuno-suppressive, cytokine inhibiting therapies, such as IL-1 inhibitors. The immuno-suppression of patients by these agents results in side effects that often include respiratory tract infections caused by pneumococci. However, only a limited number of studies investigated the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in pneumococcal respiratory infections. Future studies, especially those considering the complex interplay of human genetics, immuno-suppressive status, and age with pneumococcal colonization are needed to better understand the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in such infections.

Author Contributions

SS and NS conceived the concept for this review article. SS, FC, and NS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research is supported by the Federal Excellence Initiative of Mecklenburg Western Pomerania and European Social Fund (ESF) Grant KoInfekt (ESF_14-BM-A55-0001_16).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell (2010) 140:805–20. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ruiz-Moreno JS, Hamann L, Jin L, Sander LE, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Cambier J, et al. The cGAS/STING Pathway Detects Streptococcus pneumoniae but Appears Dispensable for Antipneumococcal Defense in Mice and Humans. Infect Immun (2018) 86. 10.1128/IAI.00849-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell (2002) 10:417–26. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saxena M, Yeretssian G. NOD-Like Receptors: Master Regulators of Inflammation and Cancer. Front Immunol (2014) 5. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greaney AJ, Leppla SH, Moayeri M. Bacterial Exotoxins and the Inflammasome. Front Immunol (2015) 6. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Storek KM, Monack DM. Bacterial recognition pathways that lead to inflammasome activation. Immunol Rev (2015) 265:112–29. 10.1111/imr.12289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mangan MSJ, Olhava EJ, Roush WR, Seidel HM, Glick GD, Latz E. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov (2018) 17:588–606. 10.1038/nrd.2018.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Z, Zhang S, Xiao Y, Zhang W, Wu S, Qin T, et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longevity (2020) 2020:4063562. 10.1155/2020/4063562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. LaRock CN, Todd J, LaRock DL, Olson J, O’Donoghue AJ, Robertson AAB, et al. IL-1β is an innate immune sensor of microbial proteolysis. Sci Immunol (2016) 1:eaah3539–eaah. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aah3539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JPY. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol (2019) 19:477–89. 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharif H, Wang L, Wang WL, Magupalli VG, Andreeva L, Qiao Q, et al. Structural mechanism for NEK7-licensed activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Nature (2019) 570:338–43. 10.1038/s41586-019-1295-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lavrik IN, Golks A, Krammer PH. Caspases: pharmacological manipulation of cell death. J Clin Invest (2005) 115:2665–72. 10.1172/JCI26252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kelley N, Jeltema D, Duan Y, He Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20. 10.3390/ijms20133328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knop J, Spilgies LM, Rufli S, Reinhart R, Vasilikos L, Yabal M, et al. TNFR2 induced priming of the inflammasome leads to a RIPK1-dependent cell death in the absence of XIAP. Cell Death Dis (2019) 10:700. 10.1038/s41419-019-1938-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xing Y, Yao X, Li H, Xue G, Guo Q, Yang G, et al. Cutting Edge: TRAF6 Mediates TLR/IL-1R Signaling-Induced Nontranscriptional Priming of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2017) 199:1561–6. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, et al. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2009) 183:787–91. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Modulation of inflammasome pathways by bacterial and viral pathogens. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2011) 187:597–602. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amores-Iniesta J, Barberà-Cremades M, Martínez CM, Pons JA, Revilla-Nuin B, Martínez-Alarcón L, et al. Extracellular ATP Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Is an Early Danger Signal of Skin Allograft Rejection. Cell Rep (2017) 21:3414–26. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eigenbrod T, Dalpke AH. Bacterial RNA: An Underestimated Stimulus for Innate Immune Responses. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2015) 195:411–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang W, Li G, De W, Luo Z, Pan P, Tian M, et al. Zika virus infection induces host inflammatory responses by facilitating NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and interleukin-1β secretion. Nat Commun (2018) 9:106. 10.1038/s41467-017-02645-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erdei J, Tóth A, Balogh E, Nyakundi BB, Bányai E, Ryffel B, et al. Induction of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Heme in Human Endothelial Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longevity (2018) 2018:4310816. 10.1155/2018/4310816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakanishi A, Kaneko N, Takeda H, Sawasaki T, Morikawa S, Zhou W, et al. Amyloid β directly interacts with NLRP3 to initiate inflammasome activation: identification of an intrinsic NLRP3 ligand in a cell-free system. Inflammation Regeneration (2018) 38:27. 10.1186/s41232-018-0085-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature (2010) 464:1357–61. 10.1038/nature08938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature (2006) 440:237–41. 10.1038/nature04516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol (2008) 9:847–56. 10.1038/ni.1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Compan V, Baroja-Mazo A, López-Castejón G, Gomez AI, Martínez CM, Angosto D, et al. Cell volume regulation modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity (2012) 37:487–500. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gong T, Yang Y, Jin T, Jiang W, Zhou R. Orchestration of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Ion Fluxes. Trends Immunol (2018) 39:393–406. 10.1016/j.it.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kinnunen K, Piippo N, Loukovaara S, Hytti M, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Lysosomal destabilization activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). J Cell Commun Signaling (2017) 11:275–9. 10.1007/s12079-017-0396-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heid ME, Keyel PA, Kamga C, Shiva S, Watkins SC, Salter RD. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species induces NLRP3-dependent lysosomal damage and inflammasome activation. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2013) 191:5230–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gritsenko A, Yu S, Martin-Sanchez F, del Olmo ID, Nichols E-M, Davis DM, et al. Priming is dispensable for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human monocytes. bioRxiv (2020) 2020.01.30.925248. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.565924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Netea MG, Nold-Petry CA, Nold MF, Joosten LA, Opitz B, van der Meer JH, et al. Differential requirement for the activation of the inflammasome for processing and release of IL-1beta in monocytes and macrophages. Blood (2009) 113:2324–35. 10.1182/blood-2008-03-146720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Elliott JM, Rouge L, Wiesmann C, Scheer JM. Crystal structure of procaspase-1 zymogen domain reveals insight into inflammatory caspase autoactivation. J Biol Chem (2009) 284:6546–53. 10.1074/jbc.M806121200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature (2015) 526:660–5. 10.1038/nature15514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli VG, Wu H, et al. Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature (2016) 535:153–8. 10.1038/nature18629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. He WT, Wan H, Hu L, Chen P, Wang X, Huang Z, et al. Gasdermin D is an executor of pyroptosis and required for interleukin-1beta secretion. Cell Res (2015) 25:1285–98. 10.1038/cr.2015.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karmakar M, Minns M, Greenberg EN, Diaz-Aponte J, Pestonjamasp K, Johnson JL, et al. N-GSDMD trafficking to neutrophil organelles facilitates IL-1β release independently of plasma membrane pores and pyroptosis. Nat Commun (2020) 11:2212. 10.1038/s41467-020-16043-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lamkanfi M, Sarkar A, Vande Walle L, Vitari AC, Amer AO, Wewers MD, et al. Inflammasome-dependent release of the alarmin HMGB1 in endotoxemia. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2010) 185:4385–92. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schiraldi M, Raucci A, Muñoz LM, Livoti E, Celona B, Venereau E, et al. HMGB1 promotes recruitment of inflammatory cells to damaged tissues by forming a complex with CXCL12 and signaling via CXCR4. J Exp Med (2012) 209:551–63. 10.1084/jem.20111739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. von Moltke J, Trinidad NJ, Moayeri M, Kintzer AF, Wang SB, van Rooijen N, et al. Rapid induction of inflammatory lipid mediators by the inflammasome in vivo. Nature (2012) 490:107–11. 10.1038/nature11351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang Y, Wang H, Kouadir M, Song H, Shi F. Recent advances in the mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its inhibitors. Cell Death Dis (2019) 10:128. 10.1038/s41419-019-1413-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baker PJ, Boucher D, Bierschenk D, Tebartz C, Whitney PG, D'Silva DB, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation downstream of cytoplasmic LPS recognition by both caspase-4 and caspase-5. Eur J Immunol (2015) 45:2918–26. 10.1002/eji.201545655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Masters SL, Dunne A, Subramanian SL, Hull RL, Tannahill GM, Sharp FA, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL-1β in type 2 diabetes. Nat Immunol (2010) 11:897–904. 10.1038/ni.1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee HM, Kim JJ, Kim HJ, Shong M, Ku BJ, Jo EK. Upregulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes (2013) 62:194–204. 10.2337/db12-0420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Booshehri LM, Hoffman HM. CAPS and NLRP3. J Clin Immunol (2019) 39:277–86. 10.1007/s10875-019-00638-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee C, Do HTT, Her J, Kim Y, Seo D, Rhee I. Inflammasome as a promising therapeutic target for cancer. Life Sci (2019) 231:116593. 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhen Y, Zhang H. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Immunol (2019) 10:276. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet (2001) 29:301–5. 10.1038/ng756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hoffman HM, Wanderer AA, Broide DH. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome: phenotype and genotype of an autosomal dominant periodic fever. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2001) 108:615–20. 10.1067/mai.2001.118790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brydges SD, Mueller JL, McGeough MD, Pena CA, Misaghi A, Gandhi C, et al. Inflammasome-mediated disease animal models reveal roles for innate but not adaptive immunity. Immunity (2009) 30:875–87. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Meng G, Zhang F, Fuss I, Kitani A, Strober W. A mutation in the Nlrp3 gene causing inflammasome hyperactivation potentiates Th17 cell-dominant immune responses. Immunity (2009) 30:860–74. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. New Engl J Med (2011) 365:2205–19. 10.1056/NEJMra1004965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brennan FM, McInnes IB. Evidence that cytokines play a role in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest (2008) 118:3537–45. 10.1172/JCI36389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dayer JM. The pivotal role of interleukin-1 in the clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford) (2003) 42 Suppl 2:ii3–10. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang H, Huang Y, Wang S, Fu R, Guo C, Wang H, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to bone erosion in collagen-induced arthritis by differentiating to osteoclasts. J Autoimmun (2015) 65:82–9. 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li Z, Guo J, Bi L. Role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in autoimmune diseases. BioMed Pharmacother (2020) 130:110542. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rabes A, Suttorp N, Opitz B. Inflammasomes in Pneumococcal Infection: Innate Immune Sensing and Bacterial Evasion Strategies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol (2016) 397:215–27. 10.1007/978-3-319-41171-2_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Kineret (anakinra) Initial U.S. Approval. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/103950s5136lbl.pdf.

- 58. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Arcalyst (Rilonacept) Initial U.S. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125249s045lbl.pdf.

- 59. Dubois EA, Rissmann R, Cohen AF. Rilonacept and canakinumab. Br J Clin Pharmacol (2011) 71:639–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03958.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Ilaris (Canakinumab) Initial U.S. Approval. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125319s100lbl.pdf.

- 61. Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Leslie KS, Hachulla E, Quartier P, et al. Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med (2009) 360:2416–25. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jiang H, He H, Chen Y, Huang W, Cheng J, Ye J, et al. Identification of a selective and direct NLRP3 inhibitor to treat inflammatory disorders. J Exp Med (2017) 214:3219–38. 10.1084/jem.20171419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cavelti-Weder C, Babians-Brunner A, Keller C, Stahel MA, Kurz-Levin M, Zayed H, et al. Effects of gevokizumab on glycemia and inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care (2012) 35:1654–62. 10.2337/dc11-2219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Knickelbein JE, Tucker WR, Bhatt N, Armbrust K, Valent D, Obiyor D, et al. Gevokizumab in the Treatment of Autoimmune Non-necrotizing Anterior Scleritis: Results of a Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Am J Ophthalmol (2016) 172:104–10. 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bihorel S, Fiedler-Kelly J, Ludwig E, Sloan-Lancaster J, Raddad E. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of LY2189102 after multiple intravenous and subcutaneous administrations. AAPS J (2014) 16:1009–17. 10.1208/s12248-014-9623-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lamkanfi M, Mueller JL, Vitari AC, Misaghi S, Fedorova A, Deshayes K, et al. Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J Cell Biol (2009) 187:61–70. 10.1083/jcb.200903124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, Herman WH, Holman RR, Jones NP, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med (2006) 355:2427–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa066224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Langer O, Conway DL, Berkus MD, Xenakis EM. Gonzales O. A comparison of glyburide and insulin in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med (2000) 343:1134–8. 10.1056/NEJM200010193431601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rudolphi K, Gerwin N, Verzijl N, van der Kraan P, van den Berg W. Pralnacasan, an inhibitor of interleukin-1beta converting enzyme, reduces joint damage in two murine models of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage (2003) 11:738–46. 10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00153-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wannamaker W, Davies R, Namchuk M, Pollard J, Ford P, Ku G, et al. (S)-1-((S)-2-{[1-(4-amino-3-chloro-phenyl)-methanoyl]-amino}-3,3-dimethyl-butanoyl)-pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid ((2R,3S)-2-ethoxy-5-oxo-tetrahydro-furan-3-yl)-amide (VX-765), an orally available selective interleukin (IL)-converting enzyme/caspase-1 inhibitor, exhibits potent anti-inflammatory activities by inhibiting the release of IL-1beta and IL-18. J Pharmacol Exp Ther (2007) 321:509–16. 10.1124/jpet.106.111344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Marchetti C, Swartzwelter B, Gamboni F, Neff CP, Richter K, Azam T, et al. OLT1177, a β-sulfonyl nitrile compound, safe in humans, inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome and reverses the metabolic cost of inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2018) 115:E1530–9. 10.1073/pnas.1716095115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Cohen SB, Proudman S, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, Donohue JP, Burstein D, et al. A randomized, double-blind study of AMG 108 (a fully human monoclonal antibody to IL-1R1) in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Res Ther (2011) 13:R125. 10.1186/ar3430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pile KD, Graham GG, Mahler SM. “Interleukin 1 Inhibitors”. In: Parnham M, editor. Encyclopedia of Inflammatory Diseases. Basel: Springer Basel; (2015). p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ottaviani S, Moltó A, Ea H-K, Neveu S, Gill G, Brunier L, et al. Efficacy of anakinra in gouty arthritis: a retrospective study of 40 cases. Arthritis Res Ther (2013) 15:R123. 10.1186/ar4303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mertens M, Singh JA. Anakinra for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol (2009) 36:1118–25. 10.3899/jrheum.090074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, Vølund A, Ehses JA, Seifert B, et al. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med (2007) 356:1517–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa065213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Fleischmann RM, Schechtman J, Bennett R, Handel ML, Burmester GR, Tesser J, et al. Anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (r-metHuIL-1ra), in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A large, international, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatism (2003) 48:927–34. 10.1002/art.10870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bettiol A, Lopalco G, Emmi G, Cantarini L, Urban ML, Vitale A, et al. Unveiling the Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Anti-Interleukin-1 Treatment in Monogenic and Multifactorial Autoinflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20. 10.3390/ijms20081898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Siemens N, Oehmcke-Hecht S, Mettenleiter TC, Kreikemeyer B, Valentin-Weigand P, Hammerschmidt S. Port d’Entree for Respiratory Infections - Does the Influenza A Virus Pave the Way for Bacteria? Front Microbiol (2017) 8:2602. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev (2006) 19:571–82. 10.1128/CMR.00058-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ozen G, Pedro S, England BR, Mehta B, Wolfe F, Michaud K. Risk of Serious Infection in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated With Biologic Versus Nonbiologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs. ACR Open Rheumatol (2019) 1:424–32. 10.1002/acr2.11064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yau B, Hunt NH, Mitchell AJ, Too LK. Blood–Brain Barrier Pathology and CNS Outcomes in Streptococcus pneumoniae Meningitis. Int J Mol Sci (2018) 19. 10.3390/ijms19113555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Geldhoff M, Mook-Kanamori BB, Brouwer MC, Troost D, Leemans JC, Flavell RA, et al. Inflammasome activation mediates inflammation and outcome in humans and mice with pneumococcal meningitis. BMC Infect Dis (2013) 13:358. 10.1186/1471-2334-13-358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Weiser JN, Ferreira DM, Paton JC. Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat Rev Microbiol (2018) 16:355–67. 10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. McNeela EA, Burke A, Neill DR, Baxter C, Fernandes VE, Ferreira D, et al. Pneumolysin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and promotes proinflammatory cytokines independently of TLR4. PLoS Pathog (2010) 6:e1001191. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hoegen T, Tremel N, Klein M, Angele B, Wagner H, Kirschning C, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to brain injury in pneumococcal meningitis and is activated through ATP-dependent lysosomal cathepsin B release. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2011) 187:5440–51. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kadioglu A, Weiser JN, Paton JC, Andrew PW. The role of Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors in host respiratory colonization and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol (2008) 6:288–301. 10.1038/nrmicro1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Witzenrath M, Pache F, Lorenz D, Koppe U, Gutbier B, Tabeling C, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is differentially activated by pneumolysin variants and contributes to host defense in pneumococcal pneumonia. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2011) 187:434–40. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fatykhova D, Rabes A, Machnik C, Guruprasad K, Pache F, Berg J, et al. Serotype 1 and 8 Pneumococci Evade Sensing by Inflammasomes in Human Lung Tissue. PloS One (2015) 10:e0137108. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Karmakar M, Katsnelson M, Malak HA, Greene NG, Howell SJ, Hise AG, et al. Neutrophil IL-1β processing induced by pneumolysin is mediated by the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome and caspase-1 activation and is dependent on K+ efflux. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2015) 194:1763–75. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Biondo C, Mancuso G, Midiri A, Signorino G, Domina M, Lanza Cariccio V, et al. The Interleukin-1β/CXCL1/2/Neutrophil Axis Mediates Host Protection against Group B Streptococcal Infection. Infect Immun (2014) 82:4508–17. 10.1128/IAI.02104-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Matsumura T, Takahashi Y. The role of myeloid cells in prevention and control of group A streptococcal infections. Biosafety Health (2020) 2:130–4. 10.1016/j.bsheal.2020.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lemon JK, Miller MR, Weiser JN. Sensing of interleukin-1 cytokines during Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization contributes to macrophage recruitment and bacterial clearance. Infect Immun (2015) 83:3204–12. 10.1128/IAI.00224-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zhang T, Du H, Feng S, Wu R, Chen T, Jiang J, et al. NLRP3/ASC/Caspase-1 axis and serine protease activity are involved in neutrophil IL-1β processing during Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2019) 513:675–80. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV, Cua DJ. The IL-23–IL-17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat Rev Immunol (2014) 14:585–600. 10.1038/nri3707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Onishi RM, Gaffen SL. Interleukin-17 and its target genes: mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunology (2010) 129:311–21. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03240.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hassane M, Demon D, Soulard D, Fontaine J, Keller LE, Patin EC, et al. Neutrophilic NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent IL-1beta secretion regulates the gammadeltaT17 cell response in respiratory bacterial infections. Mucosal Immunol (2017) 10:1056–68. 10.1038/mi.2016.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zhang Z, Clarke TB, Weiser JN. Cellular effectors mediating Th17-dependent clearance of pneumococcal colonization in mice. J Clin Invest (2009) 119:1899–909. 10.1172/JCI36731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Fang R, Tsuchiya K, Kawamura I, Shen Y, Hara H, Sakai S, et al. Critical roles of ASC inflammasomes in caspase-1 activation and host innate resistance to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2011) 187:4890–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Erttmann SF, Gekara NO. Hydrogen peroxide release by bacteria suppresses inflammasome-dependent innate immunity. Nat Commun (2019) 10:3493. 10.1038/s41467-019-11169-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Cho SJ, Rooney K, Choi AMK, Stout-Delgado HW. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in aged macrophages is diminished during Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol (2018) 314:L372–l87. 10.1152/ajplung.00393.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Krone CL, Trzciński K, Zborowski T, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. Impaired innate mucosal immunity in aged mice permits prolonged Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization. Infect Immun (2013) 81:4615–25. 10.1128/IAI.00618-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sha W, Mitoma H, Hanabuchi S, Bao M, Weng L, Sugimoto N, et al. Human NLRP3 inflammasome senses multiple types of bacterial RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111:16059–64. 10.1073/pnas.1412487111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Gupta R, Ghosh S, Monks B, DeOliveira RB, Tzeng TC, Kalantari P, et al. RNA and β-hemolysin of group B Streptococcus induce interleukin-1β (IL-1β) by activating NLRP3 inflammasomes in mouse macrophages. J Biol Chem (2014) 289:13701–5. 10.1074/jbc.C114.548982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Yap JKY, Moriyama M, Iwasaki A. Inflammasomes and Pyroptosis as Therapeutic Targets for COVID-19. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2020) 205:307–12. 10.4049/jimmunol.2000513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Snall J, Linner A, Uhlmann J, Siemens N, Ibold H, Janos M, et al. Differential neutrophil responses to bacterial stimuli: Streptococcal strains are potent inducers of heparin-binding protein and resistin-release. Sci Rep (2016) 6:21288. 10.1038/srep21288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]