Abstract

The fungus “Fuling” has been used in Chinese traditional medicine for more than 2000 years, and its sclerotia have a wide range of biological activities including antitumour, immunomodulation, anti-inflammation, antioxidation, anti-aging etc. This prized medicinal mushroom also known as “Hoelen” is resurrected from a piece of pre-Linnean scientific literature. Fries treated it as Pachyma hoelen Fr. and mentioned that it was cultivated on pine trees in China. However, this name had been almost forgotten, and Poria cocos (syn. Wolfiporia cocos), originally described from North America, and known as “Tuckahoe” has been applied to “Fuling” in most publications. Although Merrill mentioned a 100 years ago that Asian Pachyma hoelen and North American P. cocos are similar but different, no comprehensive taxonomical studies have been carried out on the East Asian Pachyma hoelen and its related species. Based on phylogenetic analyses and morphological examination on both the sclerotia and the basidiocarps which are very seldomly developed, the East Asian samples of Pachyma hoelen including sclerotia, commercial strains for cultivation and fruiting bodies, nested in a strongly supported, homogeneous lineage which clearly separated from the lineages of North American Wolfiporia cocos and other species. So we confirm that the widely cultivated “Fuling” Pachyma hoelen in East Asia is not conspecific with the North American Wolfiporia cocos. Based on the changes in Art. 59 of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, the generic name Pachyma, which was sanctioned by Fries, has nomenclatural priority (ICN, Art. F.3.1), and this name well represents the economically important stage of the generic type. So we propose to use Pachyma rather than Wolfiporia, and subsequently Pachyma hoelen and Pachyma cocos are the valid names for “Fuling” in East Asia and “Tuckahoe” in North America, respectively. In addition, a new combination, Pachyma pseudococos, is proposed. Furthermore, it seems that Pachyma cocos is a species complex, and that three species exist in North America.

Keywords: Poria cocos, Daedalea extensa, Macrohyporia, Hoelen, phylogeny, nomenclature

Introduction

In the subkingdom Dikarya, many fungi can produce dense aggregations called sclerotia to survive challenging environmental conditions and to provide reserves for fungi to germinate (Coley-Smith and Cooke, 1971; Willets and Bullock, 1992; Smith et al., 2015). Sclerotia, as persistent fungal structures commonly contain biologically active secondary metabolites, are used as a functional food (Wong and Cheung, 2009; Lau and Abdullah, 2016). Large subterranean sclerotia of different mushroom species are traditionally consumed by indigenous people around the world (Oso, 1977; Aguiar and Sousa, 1981; Bandara et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2015). In North America, the hypogeous sclerotia of a mushroom species, know as “Tuckahoe” or “Indian bread,” are utilized as a traditional food by native Americans (Gore, 1881; Weber, 1929). The first valid scientific description of this fungal sclerotia was given by Schweinitz (1822), who named it Sclerotium cocos Schwein. This name was accepted by Fries (1822), when he proposed the genus Pachyma Fr. Subsequently, the name Pachyma cocos (Schwein.) Fr. became the most popular binomial of the Tuckahoe mushroom (e.g., Currey and Hanbury, 1860; Gore, 1881; Prilleaux, 1889; Elliott, 1922). However, the sexual stage of P. cocos had remained unknown for a 100 years, until its whitish resupinate poroid fruiting body was discovered by Wolf (1922). At that time, the generic name Poria Pers. was widely used for all light-colored and resupinate polypores (Murrill, 1920, 1923), thus the sexual stage was named as Poria cocos (Schwein.) F. A. Wolf by Wolf (1922). The classification of Poria cocos was revised by Johansen and Ryvarden (1979), who transferred this species to their new genus Macrohyporia I. Johans. & Ryvarden, typified by M. dictyopora (Cooke) I. Johans. & Ryvarden. Later, Ryvarden and Gilbertson (1984) established the genus Wolfiporia Ryvarden & Gilb. typified by Poria cocos, based on its different spore morphology similar to M. dictyopora. However, Ginns and Lowe (1983) placed Poria cocos in synonymy with the earlier teleomorphic name Daedalea extensa Peck, and transferred this species to Macrohyporia. Subsequently, Ginns (1984) accepted the generic revision of Ryvarden and Gilbertson (1984) and corrected the name of the species by publishing the binomial, Wolfiporia extensa (Peck) Ginns. Nevertheless, because of the research and the preference of the traditional medical community to continue using the familiar name “cocos,” Redhead and Ginns (2006) proposed to conserve the name Poria cocos (syn. Wolfiporia cocos) over Daedalea extensa (syn. Wolfiporia extensa). Finally, the conservation of Poria cocos was recommended by the Nomenclature Committee for Fungi (Norvell, 2008).

The name Poria cocos is also commonly applied to a fungal sclerotium, known as “Fuling” in China, which has been used in Chinese traditional medicine for more than 2000 years for relieving coughs, inducing diuresis, aleviating anxiety, relieving fever, antitumor; adjustment of intestinal bacterial flora, antihyperlipidemic activity, antioxidant, anti-hepatitis B virus, anti-inflammation, anti-metastasis, anti-tyrosinase, hypoglycemic activity, improvement of cardiac function, improvement of learning and memory abilities, improvement of liver fibrosis, prevention of diabetic nephropathy, and sedative and hypnotic activities (Wang et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2019). Pharmacological studies have confirmed these properties (e.g., Sun, 2014; Zhang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019). The edible sclerotia of “Fuling” is widely cultivated in China (Wang et al., 2013), and the products are exported to more than 40 countries (Chi et al., 2018). This prized medicinal mushroom is also known as “Hoelen” (e.g., Xu et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016), a name erected from a piece of pre-Linnean scientific literature published posthumously by Rumphius (1750). Fries (1822) mentioned “Hoelen” as a little-known medicinal species from China, under the genus Pachyma. Merrill (1917) noted that Pachyma hoelen Fr. was cultivated on pine trees in various parts of China and that it had been referred to as Poria cocos. In order to clarify the identity of P. hoelen, he sent a Chinese specimen (received from a drug store) for examination to W. A. Murrill. Murrill stated that the Chinese sclerotia showed similarity to the samples collected from different localities in America, but he thought “that Pachyma hoelen Fries is distinct from P. cocos Fries” (Merrill, 1917).

In recent years, molecular studies have shown that several traditionally used and widely cultivated East Asian medicinal mushrooms (e.g., Auricularia heimuer F. Wu, B.K. Cui & Y.C. Dai, Flammulina filiformis (Z.W. Ge, X.B. Liu & Zhu L. Yang) P.M. Wang, Y.C. Dai, E. Horak & Zhu L. Yang, Ganoderma lingzhi Sheng H. Wu, Y. Cao & Y.C. Dai) are different at the species level from their European or North American relatives (Cao et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014; Dai et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). Currently, “Fuling” is widely identified with Poria cocos (syn. Wolfiporia cocos, syn. Pachyma cocos), a species originally described from North America, and no comprehensive taxonomical studies have been carried out on the East Asian Pachyma hoelen since it was described by Fries almost 200 years ago. Therefore, in this study we aim to typify the forgotten species P. hoelen and clarify the taxonomy of the “Fuling” mushroom, based on morphological features and phylogenetic evidence.

Materials and Methods

Morphological Studies

Specimens and isolates of Pachyma “cocos” originating from East Asia (China, Japan) and North America were examined, including wild collections and commercially cultivated strains. Voucher specimens are deposited at the herbarium of the Institute of Microbiology, Beijing Forestry University (BJFC) and Herbarium Mycologium, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China (HMAS). The designated neotype of Pachyma hoelen (Dong 897, HMAS 248370) is registered in MycoBank (Robert et al., 2013). Macro-morphological descriptions are based on field notes and dry herbarium specimens. Microscopic measurements and drawings were made from slide preparations of dried specimens stained with Cotton Blue and Melzer's reagent following Dai (2010). In presenting spore size variation, 5% of measurements were excluded from each end of the range and this value is given in parentheses. The following abbreviations were used: KOH = 2% potassium hydroxide, CB– = acyanophilous, IKI– = neither amyloid nor dextrinoid in Melzer's reagent, L = mean spore length (arithmetic average of all spores), W = mean spore width (arithmetic average of all spores), Q = variation in the L/W ratios between specimens studied, n (a/b) = number of spores (a) measured from given number of specimens (b).

Molecular Phylogenetic Study

Total genomic DNA was extracted from dried specimens using a CTAB rapid plant genome extraction kit (Aidlab Biotechnologies Company, Limited, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To generate PCR amplicons, the following primer pairs were used: ITS4 and ITS5 (White et al., 1990) for the internal transcribed spacer (ITS), and 983F and 1567R (Rehner and Buckley, 2005) for a region of the translation elongation factor alpha-1 (tef1), LR0R and LR7 (Vilgalys and Hester, 1990) for the 28S gene region (LSU) and bRPB2-6F and bRPB2-7.1R (Matheny, 2005) for partial RNA polymerase II, second largest submit (rpb2). The PCR procedures followed Song and Cui (2017). PCR products were purified and sequenced at the Beijing Genomics Institute with the same primers. The sequences generated during this study are deposited in NCBI GenBank under the accession numbers MW251858-MW251879 (ITS and LSU), MW250253-MW250273 (tef1 and rpb2) and listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Taxa used in the phylogenetic analyses along with their GenBank accession numbers and references.

| Species name | Collection number | Origin | ITS | LSU | tef1 | rpb2 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antrodia serpens | Dai 7465 | China | KR605813 | KR605752 | KR610742 | KR610832 | Han et al., 2016 |

| Antrodia serpens | Rivoire 3576 (LY) | France | KC543169 | – | KC543191 | – | Spirin et al., 2013 |

| Antrodia tanakae | Kajander 270 (H) | Finland | KC543165 | – | KC543190 | – | Spirin et al., 2013 |

| Antrodia tanakae | Spirin 3968 (H) | Russia | KC543164 | – | KC543193 | – | Spirin et al., 2013 |

| Antrodia heteromorpha | Dai 12755 | USA | KP715306 | KP715322 | KP715336 | KR610828 | Chen and Cui, 2015 |

| Antrodia heteromorpha | Gaarder 1665 (O) | Norway | KC543150 | – | KC543186 | – | Spirin et al., 2013 |

| Antrodia heteromorpha | CBS 200.91 | Canada | DQ491415 | – | – | DQ491388 | Kim et al., 2007 |

| Fomitopsis betulina | Dai 11449 | China | KR605798 | KR605737 | KR610726 | KR610816 | Han et al., 2016 |

| Fomitopsis betulina | Miettinen 12388 | Finland | JX109856 | JX109856 | JX109913 | JX109884 | Binder et al., 2013 |

| Fomitopsis pinicola | Cui 10312 | China | KR605781 | KR605720 | KR610689 | KR610780 | Han et al., 2016 |

| Fomitopsis pinicola | AT-Fp-1 | Sweden | MK208852 | – | MK236359 | MK236362 | Haight et al., 2019 |

| Fomitopsis schrenkii | JEH-150, type | USA | KU169365 | – | MK236356 | MK208858 | Haight et al., 2019 |

| Fomitopsis schrenkii | JW24-525-0 | USA | MK208854 | – | MK236358 | MK208860 | Haight et al., 2019 |

| Fomitopsis durescens | Overholts 4215 | USA | KF937293 | KF937295 | – | – | Han, et al., 2014 |

| Fomitopsis durescens | O 10796 | Venezuela | KF937292 | KF937294 | KR610669 | KR610766 | Han et al., 2014 |

| Kusaghiporia usambarensis | J. Hussein 01/16 | Tanzania | – | MH010044 | MH048871 | MH048870 | Hussein et al., 2018 |

| Kusaghiporia usambarensis | J. Hussein 01/17 | Tanzania | – | MH010045 | MH048869 | – | Hussein et al., 2018 |

| Laetiporus gilbertsonii | JV 1109/31 | USA | KF951293 | KF951306 | KX354630 | KX354671 | Song and Cui, 2017 |

| Laetiporus gilbertsonii | CA 13 | USA | EU402549 | EU402527 | AB472666 | – | Lindner and Banik, 2008 |

| Laetiporus montanus | Dai 15888 | China | KX354466 | KX354494 | KX354619 | KX354662 | Song and Cui, 2017 |

| Laetiporus montanus | L17-LI | Austria | EU840553 | – | – | – | Vasaitis et al., 2009 |

| Laetiporus sulphureus | JV 1106/15 | Czech Republic | KF951296 | KF951303 | KX354609 | KX354654 | Song and Cui, 2017 |

| Laetiporus sulphureus | Cui 12388 | China | KR187105 | KX354486 | KX354607 | KX354652 | Song and Cui, 2017 |

| Pachyma cocos | CBS 279.55 | USA | MW251869 | MW251858 | MW250253 | MW250264 | This study |

| Pachmya cocos* | MD-106 | USA | EU402594 | EU402594 | – | – | Lindner and Banik, 2008 |

| Pachmya cocos** | JV0506_4J | USA | MN392911 | MN392911 | – | – | unpublished |

| Pachmya cocos** | JV1608_23J | USA | MN392912 | MN392912 | – | – | unpublished |

| Pachmya cocos* | CFMR:MD-275 | USA | KU668964 | – | – | – | unpublished |

| Pachmya cocos* | Batch3_14064_14098 | USA | KT693239 | – | – | – | Raja et al., 2017 |

| Pachmya cocos*** | MRM011 | USA | MT241733 | – | – | – | unpublished |

| Pachmya hoelen | CGMCC 5.908 | China | MW251870 | MW251859 | MW250254 | MW250265 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | Dai 20041 | China | MW251878 | MW251867 | MW250262 | MW250273 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | Dai 20036 | China | MW251877 | MW251866 | MW250261 | MW250272 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | Dai 20034 | China | MW251879 | MW251868 | MW250263 | – | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | Dong 750 | China | MW251873 | MW251862 | MW250257 | MW250268 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | Dong 830 | China | MW251874 | MW251863 | MW250258 | MW250269 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | Dong 829 | China | MW251875 | MW251864 | MW250259 | MW250270 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | Dong 897 | China | MW251871 | MW251860 | MW250255 | MW250266 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | Dong 906 | China | MW251872 | MW251861 | MW250256 | MW250267 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen | KCTC6480 | Japan | MW251876 | MW251865 | MW250260 | MW250271 | This study |

| Pachmya hoelen* | XJ-28 | China | KX268225 | – | – | – | unpublished |

| Pachmya hoelen* | Taikong | China | KX268226 | – | – | – | unpublished |

| Pachmya hoelen* | CBK-1 | China | KX354453 | KX354689 | KX354688 | KX354685 | Song and Cui, 2017 |

| Pachyma pseudococos | Dai 15269, type | China | KX354451 | – | – | – | Tibpromma et al., 2017 |

| Phaeolus schweinitzii | AFTOL-ID 702 | USA | – | AY629319 | DQ028602 | DQ408119 | Matheny et al., 2007 |

| Phaeolus schweinitzii | OKM-4435-T | USA | – | KC585199 | – | – | Ortiz-Santana et al., 2013 |

| Rhodofomes cajanderi | Cui 9879 | China | KC507157 | KC507167 | KR610663 | KR610763 | Han et al., 2016 |

| Rhodofomes cajanderi | JV 0410/14a,b-J | USA | KR605768 | KR605707 | KR610664 | – | Han et al., 2016 |

| Rhodofomes rosea | JV 1110/9 | Czech Republic | KR605783 | KR605722 | KR610694 | KR610785 | Han et al., 2016 |

| Rhodofomes rosea | Cui 10633 | China | KR605782 | KR605721 | KR610693 | KR610784 | Han et al., 2016 |

| Wolfiporia cartilaginea | Dai 3764 | China | KX354456 | – | – | – | unpublished |

| Wolfiporia cartilaginea | 13122 | Japan | KC585405 | – | – | – | Ortiz-Santana et al., 2013 |

| Wolfiporia cartilaginea | O 913120 | Japan | KX354455 | – | – | – | unpublished |

| Wolfiporia dilatohypha | S.D. Russell MycoMap 7010 | USA | MK564607 | – | – | – | unpublished |

| Wolfiporia dilatohypha | FP94089 | USA | EU402554 | EU402518 | – | – | Lindner and Banik, 2008 |

| Wolfiporia dilatohypha | CS-63 | USA | KC585400 | EU402516 | – | – | Lindner and Banik, 2008 |

| Wolfiporia dilatohypha | FP-94089-R | USA | KC585401 | KC585236 | – | – | Ortiz-Santana et al., 2013 |

| Wolfiporia dilatohypha | CS-63-59-13-A-R | USA | KC585400 | KC585234 | – | – | Ortiz-Santana et al., 2013 |

| Trametes suaveolens | Cui 11586 | China | KR605823 | KR605766 | KR610759 | KR610848 | Han et al., 2016 |

| Polyporus tuberaster | Dai 11271 | China | KU189769 | KU189800 | KU189914 | KU189983 | Zhou et al., 2016 |

as Wolfiporia cocos;

as Macrohyporia cocos;

as Wolfiporia aff. extensa.

Sequences produced in this study are indicated in bold.

Two datasets were used in the phylogenetic analyses. The multigene dataset was used to gain information about the phylogenetic position of the genus. The second ITS dataset represented sequences of only Wolfiporia cocos-related specimens. In the multigene phylogenetic analyses, the highly divergent ITS regions of the Wolfiporia s. str. (syn. Pachyma) specimens were removed. Sequences were aligned with the online version of MAFFT v. 7 using the E-INS-i algorithm (Katoh and Standley, 2013), under default settings. Each alignment was checked separately and edited with SeaView 4 (Gouy et al., 2010). Subsequently, the concatenated ITS + LSU + tef1 + rpb2 dataset alignment was subjected to Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) phylogenetic analyses, which were performed in RaxmlGUI (Silvestro and Michalak, 2012) and MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003), respectively. ML analysis was done using 1,000 rapid ML bootstrap searches. Four partitions (ITS, LSU, tef1, rpb2) were set and the GTRGAMMA nucleotide substitution model was selected for each partition. Rapid bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates was applied for testing branch support. BI was performed with the GTR + Γ model of evolution. The same partition scheme was used as for the ML analysis (see above). The BI settings were: four Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) over 5 million generations, sampling every 1000th generation, two independent runs, and burn-in of 20% (the first 1,000 trees were discarded). Post burn-in trees were used to compute a 50% majority rule consensus phylogram. Phylogenetic trees from both ML and BI analyses resulted in largely congruent topologies. The best scoring ML tree from the RAxML analysis was edited with MEGA6 (Tamura et al., 2013). ML bootstrap values (BS) > 70% and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) > 0.9 were considered evidence for statistical branch support.

Results

Molecular Phylogeny

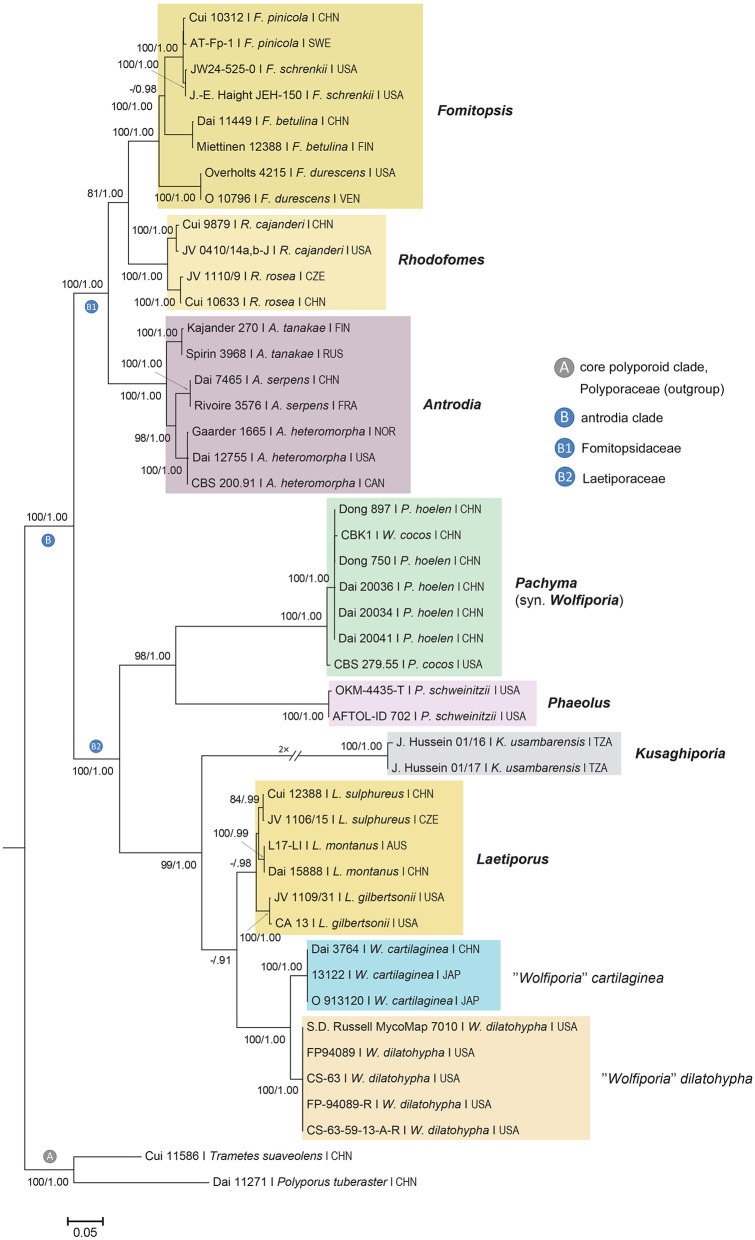

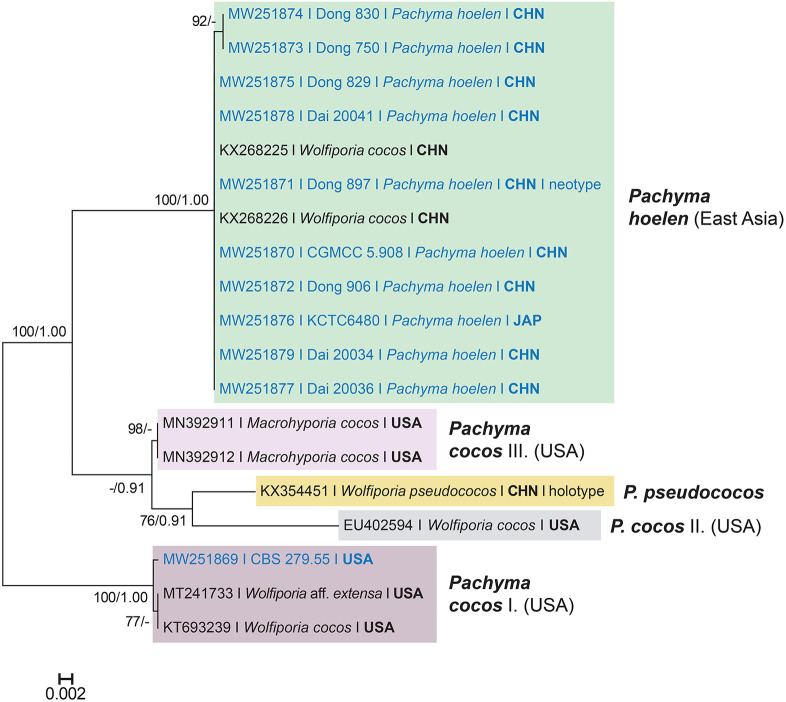

The multigene and ITS phylogenetic analyses were carried out using two datasets comprising 46 taxa and 3,160 characters, and 19 taxa and 1,698 characters including gaps, which were treated as missing data. The phylogenetic tree topology of the concatenated ITS-LSU-tef1-rpb2 dataset (Figure 1) is largely congruent with previously published phylogenies (e.g., Ortiz-Santana et al., 2013; Justo et al., 2017; Hussein et al., 2018) and the genus Pachyma (syn. Wolfiporia) clustered in the Laetiporaceae Jülich (syn. Phaeolaceae Jülich) within the antrodia clade. At the species level, the neotype of Pachyma hoelen (Dong 897, HMAS 248370) and other studied specimens from East Asia (incl. Dong 750, which is the widely cultivated strain now in China) represent a well-supported (ML/BA 100/1.00), relatively homogeneous clade. Analysis of ITS sequences (Figure 2) also shows that all newly sequenced strains from East Asia are nested in a strongly supported clade (ML/BA 100/1.00). This clade is clearly separated from the other clades in the phylogeny where P. cocos strains from North America and the holotype of W. pseudococos (GenBank no. KX354451) are nested (Figure 2). In the ITS phylogenetic tree, the Wolfiporia cocos and Macrohyporia cocos samples from the United States separated into three distinct clades and they are not closely related to Pachyma hoelen in phylogeny. Our phylogenetic reconstruction of the ITS sequences indicates that the North American samples identified as W. cocos and deposited in GenBank cover more than one species. The newly sequenced P. cocos isolate (CBS 279.55), originating from South Carolina (Southeastern United States), forms a well-supported (ML/BA 100/1.00) lineage with two sequences originating from the United States (GenBank no. MT241733 and KT693239). The W. cocos specimen collected from hardwood species (Alnus) from the United States (Lindner and Banik, 2008) formed a separate lineage within a moderately supported clade (ML/BA 63/0.91) and grouped with the type of W. pseudococos and two unpublished sequences of Macrohyporia cocos (GenBank no. MN392911 and MN392912). Based on the above single-locus and multigene molecular data, the forgotten East Asian species, Pachyma hoelen, which is widely cultivated in China and Japan, is not conspecific with the North American P. cocos (syn. Wolfiporia cocos).

Figure 1.

Phylogeny of the genus Pachyma (syn. Wolfiporia) within the antrodia clade inferred from RAxML and MrBayes analyses of the combined ITS–LSU–tef1–rpb2 sequences. Topology is from the best scoring Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree. Polyporus tuberaster and Trametes suaveolens served as the outgroup. Bayesian Posterior Probabilities (BPP) > 0.9 and ML bootstrap values > 70% are shown above or below branches. The bar indicates 0.05 expected change per site per branch.

Figure 2.

Phylogeny of Pachyma hoelen and related taxa inferred from RAxML and MrBayes analyses of nrDNA ITS sequences. Topology is from the best scoring Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree. Bayesian Posterior Probabilities (BPP) > 0.9 and ML bootstrap values > 70% are shown above or below branches. The bar indicates 0.002 expected change per site per branch.

Taxonomy

Pachyma Fr., Syst. mycol. 2(1): 242 (1822)

Synonyms. Gemmularia Raf. per Steud., Nomencl. bot. P1. crypt.: 183 (1824); Tucahus Raf., Anal. Nat. Tabl. Univ. 2: 270 (1830) nom. illegit. (ICN; Art. 52.); Rugosaria Raf., Anal. Nat. Tabl. Univ. 1: 181 (1833) nom. illegit. (ICN; Art. 52.).

Wolfiporia Ryvarden and Gilb., Mycotaxon 19: 141 (1984)

Generic type species: Pachyma cocos (Schwein.) Fr., Syst. mycol. 2(1) 242 (1822) (Basionym. Sclerotium cocos Schwein., Schr. naturf. Ges. Leipzig 1: 56. 1822), selected by Donk (1962: 94).

Description. Sclerotia globose or irregularly shaped, when fresh, outer crust reddish brown, inner context white and corky; outer crust becomes hard corky and inner context becomes fragile when dry. Basidiocarp annual, resupinate; pore surface cream to ash gray when fresh; hyphal system dimitic, generative hyphae with simple septa, skeletal hyphae thick-walled, distinctly thicker than generative hypha; cystidia absent, but cystidioles occasionally present; basidia clavate, with four sterigmata and a simple basal septum; basidiospores cylindrical, ellipsoid, hyaline, thin-walled, IKI–, CB–. Rot type brown.

Nomenclatural remarks. Fries (1822) described the anamorphic genus Pachyma and distinguished three species. Later, Donk (1962) designeted the first species, P. cocos (Schwein.) Fr. (syn. Sclerotium cocos Schwein.) as the generic type of Pachyma. The teleomorphic genus Wolfiporia was typified with Poria cocos F. A. Wolf by Ryvarden and Gilbertson (1984), which was a species derived from Sclerotium cocos Schwein., hence it was cited as a basionym by Wolf (1922). Therefore, both Pachyma and Wolfiporia are typified with Sclerotium cocos Schwein., thus these genera are considered as synonyms. Based on the changes in Art. 59 of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN; Turland et al., 2018), all legitimate fungal names are treated equally for the purposes of establishing priority, regardless of the life history stage of the type (Art. F.8.1). In the case that the sexually typified generic name does not have priority it is recommended that it can either be formally conserved (e.g., Braun, 2013), or included on a list of protected names (Rossman, 2014). The generic names Pachyma and Wolfiporia are both listed by Kirk et al. (2013) for protection as a result of changes in Art. 59. However, the earlier name Pachyma is sanctioned by Fries (ICN, Art. F.3.1) and well represents the economically important stage of the generic type. For this reason, currently we consider that it is unnecessary to conserve the name Wolfiporia over Pachyma. Consequently, based on nomenclatural priority, the use of the earlier and sanctioned generic name Pachyma is recommended over Wolfiporia.

Pachyma hoelen Fr., Syst. mycol. (Lundae) 2(1): 243 (1822) (Figures 3, 4)

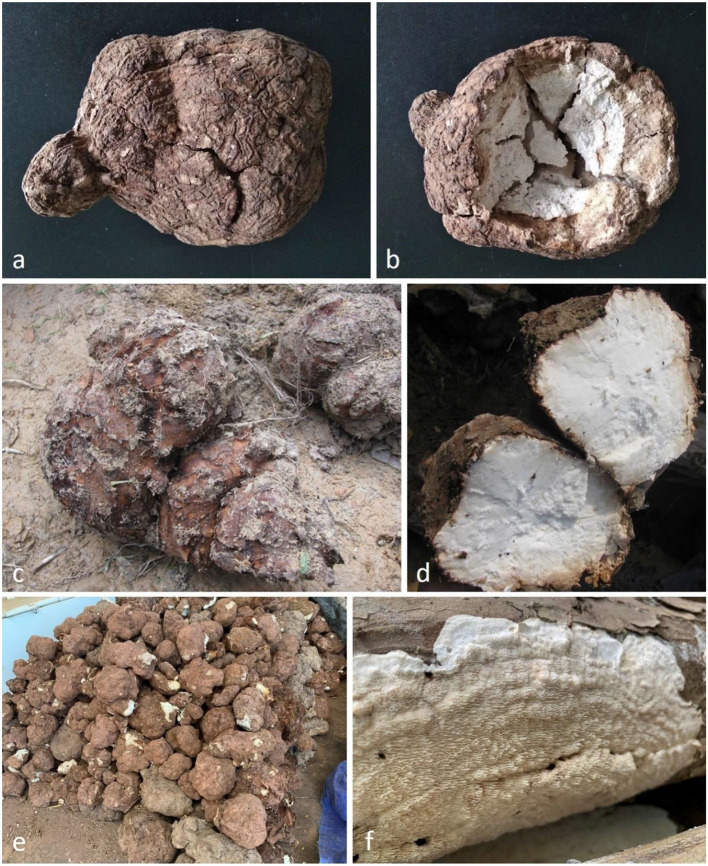

Figure 3.

Sclerotia and basidiome of Pachyma hoelen. (a,b) Dry sclerotium of P. hoelen (neotype Dong 897, HMAS 248370). (c–e) Fresh sclerotia of P. hoelen. f. Basidiome of P. hoelen (Dai 20036). Photos (a,b: SJ. Li, c–f: Y.C. Dai).

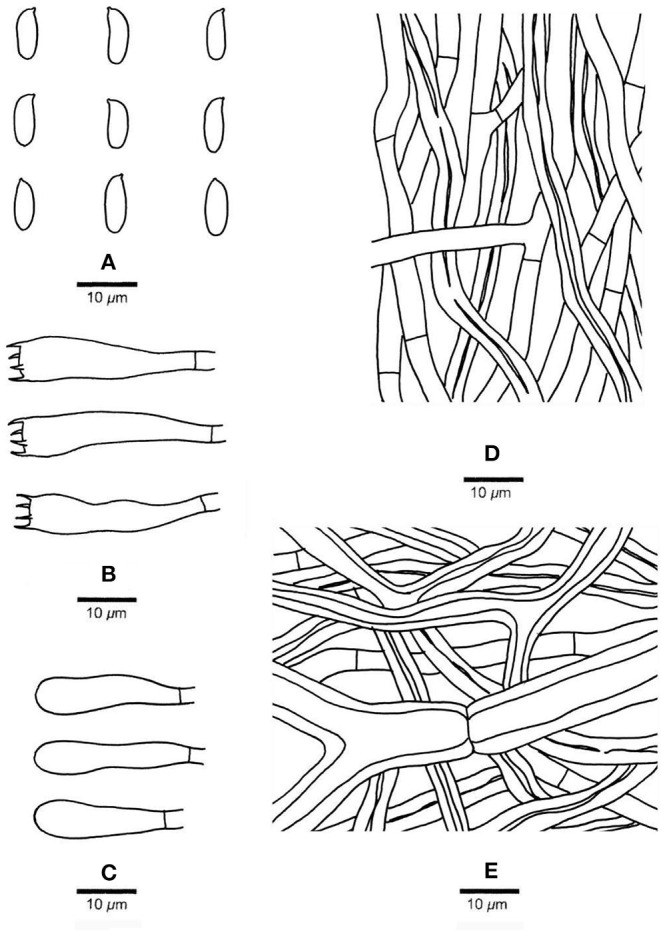

Figure 4.

Microscopic structures of Pachyma hoelen basidiome (Dai 20036). (A) Basidiospores. (B) Basidia. (C) Basidioles. (D) Hyphae from trama. (E) Hyphae from subiculum. Drawing by S. L. Liu.

Description. Sclerotia globose, subglobose, oval to irregularly shaped, up to 28 cm long and 22 cm wide, weighing up to 20 kg; when fresh, outer crust reddish brown, inner context white and corky; outer crust becomes hard corky and inner context becomes fragile when dry. Basidiocarp annual, resupinate, soft corky and without odor or taste when fresh, hard corky to fragile when dry, up to 20 cm long, 10 cm wide, 5.5 mm thick at center. Margin thin, usually pores extend to the very edge. Pore surface cream to ash gray when fresh, becoming pinkish buff to cinnamon buff when dry, not glancing; pores round, angular or sinuous, 1–2 per mm; dissepiments thick, slightly lacerate to distinctly dentate. Subiculum cinnamon buff, hard corky, up to 1.5 mm; tubes hard corky to fragile, buff, up to 4 mm long. Hyphal system dimitic in all parts, generative hyphae with simple septa, skeletal hyphae dominant, all hyphae IKI–, CB–, weakly inflated in KOH. Subicular hyphal structure homogeneous, hyphae strongly interwoven; generative hyphae occasionally present, hyaline, thin-walled, occasionally branched, frequently simple septate, 4–6 μm in diam.; skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline, thick-walled with a distinct wide lumen, usually flexuous, frequently branched, occasionally simple septate, 6–12 μm in diam. Tramal generative hyphae frequent, hyaline, thin-walled, occasionally branched, frequently simple septate, 3–5 μm in diam.; tramal skeletal hyphae frequent, hyaline, thick-walled with a wide lumen, flexuous, occasionally frequently branched and simple septate, 4–8 μm in diam. Cystidia and cystidioles absent; basidia clavate, with four sterigmata and a simple basal septum, 25–32 × 7–8 μm, basidioles in shape similar to basidia but slightly smaller. Basidiospores oblong-ellipsoid to cylindrical, tapering at apiculus, hyaline, thin-walled, IKI–, CB–, (6–)7–9.6(−11) × (2.5–)2.9–4(−4.1) μm, L = 8.24 μm, W = 3.2 μm, Q = 2.49–2.66 (n = 90/3). Rot type brown.

Specimens examined. China, Yunnan Province, Yongsheng County, Renhe, Yina, 21 Dec 2018, CH Dong 897 (HMAS 248370, neotype, designated here, MycoBank MBT394794); Guangxi Auto Region, Baise, Baise Park, on stump of Pinus massoniana 1 July 2019, Dai 20034 (BJFC031708), Dai 20036 (BJFC031710), Dai 20041 (BJFC031715).

Nomenclatural remarks. The name “Hoelen” is derived from Rumphius (1750), and frequently cited as Pachyma hoelen Rumph. in scientific literature (e.g., Saccardo et al., 1889; Hino and Katô, 1930; Takeda, 1934). In the work of Rumphius (1750) it is mentioned under the species Tuber regium Rumph. [nom. inval., Art. 32.1(a); current name is Pleurotus tuber-regium (Fr.) Singer], but without the name Pachyma, the genus which was introduced by Fries (1822). Although, Fries (1822) presumably adopted the description of P. hoelen from Rumphius (1750), this work was not cited by him. Therefore, the names P. hoelen Rumph. and P. hoelen Rumph. ex Fr. are incorrect interpretations. However, “Hoelen” formally was not clearly discussed by Fries (1822) as a binomial like the other two taxa, i.e., P. cocos (Schwein.) Fr. and P. tuber-regium Fr. (see also Donk, 1962). This nomenclatural uncertainty is supported by the index of the same work (Fries, 1822, p. 608), where P. hoelen was not listed under the genus Pachyma like the other two species. However, in his later work Fries (1832) clearly indicated that he accepted P. hoelen as a distinct species in the genus Pachyma. When Fries (1822) proposed the new genus Pachyma, he noted that “Hoelen” is a little-known species and marked it with a separate serial number (like the other two species) under the genus. Given that the epithet “Hoelen” can be assigned to the generic name Pachyma, and the species has a short diagnosis, the name Pachyma hoelen Fr. was published validly by Fries (1822) and sanctioned by the ICN (Art. F.3.1).

Pachyma pseudococos (F. Wu, J. Song & Y.C. Dai) F. Wu, Y.C. Dai & V. Papp, comb. nov.

Basionym. Wolfiporia pseudococos F. Wu, J. Song & Y.C. Dai, Fungal Diversity 83: 237 (2017)

MycoBank MB838018.

Description. For the description, see Tibpromma et al. (2017)

Specimen examined. CHINA, Hainan Province, Ledong County, Jianfengling Nature Reserve, on dead angiosperm tree, 1 June 2015, Dai 15269 (BJFC019380, holotype).

Remarks. New combination is proposed for Wolfiporia pseudococos in Pachyma based on molecular data and morphological features of the basidiocarp. Ecologically, P. pseudococos grows on angiosperm trees in tropical China, while P. hoelen has a distribution in temperate areas and usually grows on conifers. Phylogenetically, the two species are closely related, but P. pseudococos forms a separate lineage based on the analyses of ITS sequences (Figure 2). The basidiocarps of P. hoelen shares similar morphological characteristics with P. pseudococos, but differs by the absence of cystidioles, and longer and thinner basidia (25–32 × 7–8 μm vs. 16–25 × 10–14 μm in P. pseudococos).

Discussion

Before the introduction of the One Fungus-One Name (1F1N) concept, the correct name was the earliest legitimate name typified by the perfect state (= teleomorph). However, based on the changes in Art. 59 of the ICN (Turland et al., 2018), the legitimate generic names typified by anamorphic fungal stages are treated equally for the purposes of establishing priority. The generic names Pachyma and Wolfiporia have types that represent the same species and are thus synonyms. Since Pachyma is the earliest name and sanctioned by the ICN (Art. F.3.1), and has priority, we recommend Pachyma rather than Wolfiporia.

Based on molecular phylogenetic analysis, for the time being we accept two species in the genus Pachyma from China. We found that the tested wild specimens and commercial cultivars known as “Fuling” represent a single species and are not identical with the true Pachyma cocos (syn. Poria cocos) from North America. Based on a thorough study of the literature, the forgotten Friesian binomial Pachyma hoelen has proved to be the correct scientific name for this widely cultivated East Asian edible and medicinal mushroom. In addition, Pachyma hoelen grows in wood of Pinus exclusively in China, and it is cultivated on pine wood, too. Pachyma cocos sensu lato is widely distributed in North America, and both the sclerotia and basidiocarps grow on various angiosperm and gymnosperm hosts (Davidson and Campbell, 1954; Lowe, 1966). A few European locations of P. cocos have also been reported from France, Austria and Switzerland (Prilleaux, 1889; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2020). Based on the high variability observed in the sequenced ITS region of P. cocos samples from the Americas, three taxa seems to be existed in North America, but no voucher teleomorphic samples of these taxa were studied, so we currently treat them as Pachyma cocos I, Pachyma cocos II and Pachyma cocos III. Further studies are needed to clarify the taxonomy of this species.

The other two validly described species formerly discussed in Pachyma are excluded from the genus, namely P. tuber-regium Fr. and P. woermannii J. Schröt. (Fries, 1822; Cohn and Schröter, 1891). The current name of the former species is Pleurotus tuber-regium (Fr.) Singer, a well-known edible and medicinal mushroom (Dai et al., 2009, 2010; Wu et al., 2019) native to the tropics, including Africa, Asia, and Australasia (Karunarathna et al., 2016). Pachyma woermannii presumably represents the same species and is identical with Pleurotus tuber-regium. The sclerotia (as Pachyma woermannii) and the lamellate basidiocarps (as Lentinus woermannii Cohn and J. Schröt.) of the same fungus were described at the same time by Cohn and Schröter (1891), based on specimens collected from Cameroon (Central Africa). Further study is needed to confirm if the both are interspecific.

The teleomorphic genus Wolfiporia contains eight legitimate names (Index Fungorum 2020), from which six species are accepted (He et al., 2019; Wijayawardene et al., 2020). However, amongst these, only two species (Pachyma hoelen and P. pseudococos) are confirmed in Pachyma by phylogenetic data so far (Figures 1, 2). Therefore, further phylogenetic and type studies are needed to clarify the systematic position of those Wolfiporia species, which are currently not accepted in Pachyma. Wolfiporia castanopsis Y.C. Dai was described by Dai et al. (2011) from Southwest China (Yunnan Province, Zixishan Nature Reserve), based on a specimen growing on the wood of Castanopsis orthacantha Franch. Morphologically, this species is closely related to Pachyma cocos, the type species of the genus Pachyma. The two species have similar poroid and resupinate basidiocarps, but Wolfiporia castanopsis has broadly ellipsoid basidiospores (7.6–10 × 5–7 μm, Dai et al., 2011). Wolfiporia curvispora Y. C. Dai was described from Northeast China (Jilin Province), based on a single collection growing on Pinus koraiensis Siebold & Zucc. Morphologically, W. curvispora differs from other species in Wolfiporia by its biennial habit, small pores (4–5 per mm), small, curved and cylindrical basidiospores (3.3–4.1 × 1.2–1.8 μm, Dai, 1998). Wolfiporia cartilaginea Ryvarden was described from Northeast China (Jilin Province, Changbaishan National Nature Reserve) (Ryvarden et al., 1986) and phylogenetically found to be closely related to W. dilatohypha Ryvarden & Gilb. (syn. Poria inflata Overh.); these two species formed a separate lineage that is closely related to, but distinct from the core Laetiporus clade (Banik et al., 2010; Hussein et al., 2018; Figure 1). Wolfiporia sulphurea (Burt) Ginns (syn. Merulius sulphureus Burt) has similar morphological characteristics to Pachyma cocos, but it causes a white rot (Ginns, 1968; Ginns and Lowe, 1983).

The primary fungal barcoding marker, ITS, is quite useful to separate most fungal species (Xu, 2016), but it is not enough for some groups if we only use ITS in their phylogeny (Lücking et al., 2020). Unusually, the ITS sequence of Pachyma is at least twice as long as the sequences for most taxa in the antrodia clade, which is presumably due to the insertions in the ITS1 and ITS2 regions (Lindner and Banik, 2008). Although, in general the thresholds ranging from 97.0 to 99.5% sequence similarity were the most optimal values for delimiting species in the Agaricomycetes (Blaalid et al., 2013; Garnica et al., 2016; Nilsson et al., 2019), Raja et al. (2017) believed that a larger threshold value (<97%) is acceptable in the case of P. cocos specimens, due to the presence of introns. The difference in the sequences of the neotype of P. hoelen compared with the P. cocos specimen from the USA (CBS 279.55) was 8.0% for ITS. In the comparison of P. hoelen and P. cocos secondary barcoding markers (incl. protein-coding genes) we found moderate, but significant differences between the two species: tef1 (97.8%), rpb2 (98%). Therefore, both nuclear ribosomal RNA genes (ITS) and protein-coding genes (tef1, rpb2) showed remarkable differences between P. cocos and P. hoelen with low intragroup heterogeneity in the later. This confirms the separation of the two species and suggests that the inclusion of additional markers (i.e., protein-coding genes) should be necessary for further studies on the genus Pachmya.

In conclusion, Poria cocos (syn. Wolfiporia cocos) has been applied to the prized Chinese medicinal mushroom “Fuling,” according to changes in Art. 59 of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants, its correct binomial name is Pachyma hoelen Fr. which was validly published by Fries and sanctioned by the ICN. The wild teleomorphic stage (basidiocarps) of Pachyma hoelen is found and collected as the first time in China, and both tested wild specimens and commercial cultivars known as “Fuling” represent a single species. The illustrated description of Pachyma hoelen is given based on wild fruiting bodies and cultivated sclerotia, and its neotype is designated. The Chinese “Fuling” Pachyma hoelen is different from North American “Tuckahoe” Pachyma cocos (syn. Wolfiporia cocos), and Pachyma is recommended over Wolfiporia because it is the earliest and sanctioned generic name. Accordingly, Pachyma cocos (Schwein.) Fr. is the valid name for “Tuckahoe” in North America, and three taxa are existed among Pachyma cocos sensu lato. Currently five taxa are accepted in Pachmya: P. hoelen, P. pseudococos, P. cocos I, P. cocos II and P. cocos III. The phylogeny of other taxa previously described or combined in Wolfiporia are not analyzed, and their taxonomy is uncertain without molecular data.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repositories and accession numbers can be found in the article materials.

Author Contributions

Y-CD and VP designed the experiments. FW, S-JL, and CH-D prepared the samples. VP conducted the molecular experiments and analyzed the data. FW, S-JL, CH-D, Y-CD, and VP revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Shi-Liang Liu (Beijing, China) for the line drawings.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (2019QZKK0503), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC1703003), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 31530002).

References

- Aguiar I. J. A., Sousa M. A. (1981). Polyporus indigenus I. Araújo and M.A. Sousa, nova espécie da Amazônia. Acta Amazônica 11, 449–455. 10.1590/1809-43921981113449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandara A. R., Rapior S., Bhat D. J., Kakumyan P., Chamyuang S., Xu J., et al. (2015). Polyporus umbellatus, an edible-medicinal cultivated mushroom with multiple developed health-care products as food, medicine and cosmetics: a review. Cryptogam. Mycol. 36, 3–42. 10.7872/crym.v36.iss1.2015.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banik M. T., Lindner D. L., Ota Y., Hattori T. (2010). Relationships among North American and Japanese Laetiporus isolates inferred from molecular phylogenetics and single-spore incompatibility reactions. Mycologia 102, 911–917. 10.3852/09-044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernicchia A., Gorjón S. P. (2020). Polypores of the Mediterranean Region. Romar: Segrate, 904. [Google Scholar]

- Binder M., Justo A., Riley R., Salamov A., Lopez-Giraldez F., Sjokvist E., et al. (2013). Phylogenetic and phylogenomic overview of the Polyporales. Mycologia 105, 1350–1373. 10.3852/13-003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaalid R., Kumar S., Nilsson R. H., Abarenkov K., Kirk P. M., Kauserud H. (2013). ITS1 versus ITS2 as DNA metabarcodes for fungi. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 13, 218–224. 10.1111/1755-0998.12065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun U. (2013). (2210-2232) Proposals to conserve the teleomorph-typified name Blumeria against the anamorph-typified name Oidium and twenty-two teleomorph-typified powdery mildew species names against competing anamorph-typified names (Ascomycota: Erysiphaceae). Taxon 62, 1328–1331. 10.12705/626.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Wu S. H., Dai Y. C. (2012). Species clarification of the prize medicinal Ganoderma mushroom “Lingzhi”. Fungal Divers. 56, 49–62. 10.1007/s13225-012-0178-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Y., Cui B. K. (2015). Phylogenetic analysis and taxonomy of the Antrodia heteromorpha complex in China. Mycoscience 57, 1–10. 10.1016/j.myc.2015.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi X. L., Yang G., Ma S., Cheng M., Que L. (2018). Analysis of characteristics and problems of international trade of Poria cocos in China. China J. Chinese Materia Medica 43, 191–196. [in Chinese] 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20171030.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn F., Schröter J. (1891) Untersuchungen über Pachyma und Mylitta, Vol. 11 Abhandlungen des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Coley-Smith J. R., Cooke R. C. (1971). Survival and germination of fungal sclerotia. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 9:65e92. 10.1146/annurev.py.09.090171.000433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Currey F., Hanbury D. (1860). Remarks on Sclerotium stipitatum, Berk. et Curr., Pachyma cocos, Fries, and some similar productions. Trans. Linnean Soc. Lond. 23, 93–97. 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1860.tb00122.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C. (1998). Changbai wood-rotting fungi 9. Three new species and other species in Rigidoporus, Skeletocutis and Wolfiporia (Basidiomycota, Aphyllophorales). Ann. Bot. Fenn. 35, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C. (2010). Hymenochaetaceae (Basidiomycota) in China. Fungal Divers. 45, 131–343. 10.1007/s13225-010-0066-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C., Yang Z. L., Cui B. K., Yu C. J., Zhou L. W. (2009). Species diversity and utilization of medicinal mushrooms and fungi in China (Review). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 11, 287–302. 10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v11.i3.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C., Zhou L. W., Steffen K. (2011). Wood-decaying fungi in eastern Himalayas 1. Polypores from Zixishan Nature Reserve, Yunnan Province. Mycosystema 30, 674–679. [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C., Zhou L. W., Yang Z. L., Wen H. A., Bao T., Li T. H. (2010). A revised checklist of edible fungi in China. Mycosystema 29, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C., Zhou L. W., Hattori T., Cao Y., Stalpers J. A., Ryvarden L., et al. (2017). Ganoderma lingzhi (Polyporales, Basidiomycota): the scientific binomial for the widely cultivated medicinal fungus Lingzhi. Mycol. Progress 16, 1051–1055. 10.1007/s11557-017-1347-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R. W., Campbell W. A. (1954). Poria cocos, a widely distributed wood-rotting fungus. Mycologia 46, 234–237. 10.1080/00275514.1954.12024360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donk M. A. (1962). The generic names proposed for Hymenomycetes. XII. Deuteromycetes. Taxon 11, 75–104. 10.2307/1216021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. A. (1922). Some characters of the southern tuckahoe. Mycologia 14, 222–227. 10.1080/00275514.1922.12020383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fries E. M. (1822). Systema Mycologicum, Vol. 2, Sumtibus Emesti Mauritii: Gryphiswaldiae, 275. [Google Scholar]

- Fries E. M. (1832). Index Alphabeticus Generum, Specierum et Synonymorum in Eliae Fries Systemate Mycologico ejusque Supplemento ‘Elencho Fungorum’ Enumeratorum. Griefswald, 202. [Google Scholar]

- Garnica S., Schön M. E., Abarenkov K., Riess K., Liimatainen K., Niskanen T., et al. (2016). Determining threshold values for barcoding fungi: lessons from Cortinarius (Basidiomycota), a highly diverse and widespread ectomycorrhizal genus. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92:fiw045. 10.1093/femsec/fiw045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginns J. (1968). The genus Merulius. I. Species proposed by Burt. Mycologia 60, 1211–1231. 10.1080/00275514.1968.12018688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ginns J. (1984). New names, new combinations and new synonymy in the Corticiaceae, Hymenochaetaceae and Polyporaceae. Mycotaxon 21, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ginns J., Lowe J. L. (1983). Macrohyporia extensa and its synonym Poria cocos. Can. J. Bot. 61, 1672–1679. 10.1139/b83-180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gore J. H. (1881). Tuckahoe or Indian bread. Ann. Rep. Smithson. Inst. 687–701. [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M., Guindon S., Gascuel O. (2010). SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 221–224. 10.1093/molbev/msp259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight J. E., Nakasone K. K., Laursen G. A., Redhead S. A., Taylor D. L., Glaeser J. A. (2019). Fomitopsis mounceae and F. schrenkii —two new species from North America in the F. pinicola complex. Mycologia 111, 339–357. 10.1080/00275514.2018.1564449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M. L., Chen Y. Y., Shen L. L., Song J., Vlasák J., Dai Y. C., et al. (2016). Taxonomy and phylogeny of the brown-rot fungi: Fomitopsis and its related genera. Fungal Divers. 80, 343–373. 10.1007/s13225-016-0364-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han M. L., Song J., Cui B. K. (2014). Morphology and molecular phylogeny for two new species of Fomitopsis (Basidiomycota) from South China. Mycol. Prog. 13, 905–914. 10.1007/s11557-014-0976-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He M. Q., Zhao R. L., Hyde K. D., Begerow D., Kemler M., Yurkov A. M., et al. (2019). Notes, outline and divergence times of Basidiomycota. Fungal Divers. 99, 105–367. 10.1007/s13225-019-00435-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hino I., Katô H. (1930). Notes on the 'bukuryô', sclerotia of Pachyma hoelen, Rumph. Bull. Miyazaki Coll. Agric Forest. 2, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein J. M., Tibuhwa D. D., Tibell S. (2018). Phylogenetic position and taxonomy of Kusaghiporia usambarensis gen. et sp. nov. (Polyporales). Mycology 9, 136–144. 10.1080/21501203.2018.1461142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen I., Ryvarden L. (1979). Studies in the Aphyllophorales of Africa 7. Some new genera and species in the Polyporacea. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 72, 189–199. 10.1016/S0007-1536(79)80031-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Justo A., Miettinen O., Floudas D., Ortiz-Santana B., Sjökvist E., Lindner D., et al. (2017). A revised family-level classification of the Polyporales (Basidiomycota). Fungal Biol. 121, 798–824. 10.1016/j.funbio.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunarathna S. C., Mortimer P. E., Chen J., Li G. J., He M. Q., Xu J., et al. (2016). Correct names of two cultivated mushrooms from the genus Pleurotus in China. Phytotaxa 260, 36–46. 10.11646/phytotaxa.260.1.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. M., Lee J. S., Jung H. S. (2007). Fomitopsis incarnatus sp. nov. based on generic evaluation of Fomitopsis and Rhodofomes. Mycologia 99, 833–841. 10.1080/15572536.2007.11832515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk P. M., Stalpers J. A., Braun U., Crous P. W., Hansen K., Hawksworth D. L., et al. (2013). A without-prejudice list of generic names of fungi for protection under the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants. IMA Fungus 4, 381–443. 10.5598/imafungus.2013.04.02.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau B. F., Abdullah N. (2016). Sclerotium-forming mushrooms as an emerging source of medicinals: current perspectives, in Mushroom Biotechnology, Developments and Applications, ed Petre M. (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; ), 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lau B. F., Abdullah N., Aminudin N., Lee H. B., Tan P. J. (2015). Ethnomedicinal uses, pharmacological activities, and cultivation of Lignosus spp. (tiger's milk mushrooms) in Malaysia – a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 169, 441–458. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., He Y., Zeng P., Liu Y., Zhang M., Hao C., et al. (2019). Molecular basis for Poria cocos mushroom polysaccharide used as an antitumour drug in China. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23, 4–20. 10.1111/jcmm.13564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang J., Zhao Y., Liu H., Wang Y., Jin H. (2016). Exploring geographical differentiation of the Hoelen medicinal mushroom, Wolfiporia extensa (Agaricomycetes), using fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy combined with multivariate analysis. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 18, 721–731. 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.v18.i8.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner D. L., Banik M. T. (2008). Molecular phylogeny of Laetiporus and other brown rot polypore genera in North America. Mycologia 100, 417–430. 10.3852/07-124R2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. L. (1966). Polyporaceae of North America. The Genus Poria. Technical Publication of the State University College of Forestry at Syracuse University, Vol. 90, Syracuse, NY: Technical Publication of the State University College of Forestry at Syracuse University, 1–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lücking R., Aime M. C., Robbertse B., Miller A. N., Ariyawansa H. A., Aoki T., et al. (2020). Unambiguous identification of fungi: where do we stand and how accurate and precise is fungal DNA barcoding? IMA Fungus 11:14. 10.1186/s43008-020-00033-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny P. B. (2005). Improving phylogenetic inference of mushrooms with RPB1 and RPB2 nucleotide sequences (Inocybe, Agaricales). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 35, 1–20. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny P. B., Wang Z., Binder M., Curtis J. M., Lim Y. W., Nilsson R. H., et al. (2007). Contributions of rpb2 and tef1 to the phylogeny of mushrooms and allies (Basidiomycota, Fungi). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 43, 430–451. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill E. D. (1917). An Interpretation of Rumphius's Herbarium Amboinense. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 595. [Google Scholar]

- Murrill W. A. (1920). The genus Poria. Mycologia 12, 47–51. 10.2307/3753406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murrill W. A. (1923). Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf. Mycologia 15, 105–106. 10.2307/3753175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson R. H., Larsson K. H., Taylor A. F. S., Bengtsson-Palme J., Jeppesen T. S., Schigel D., et al. (2019). The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark 758 taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D259–D264. 10.1093/nar/gky1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norvell L. (2008). Report of the Nomenclature Committee for Fungi: 14. Taxon 57, 637–639. 10.5248/110.487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Santana B., Lindner D. L., Miettinen O., Justo A., Hibbett D. S. (2013). A phylogenetic overview of the antrodia clade (Basidiomycota, Polyporales). Mycologia 105, 1391–1411. 10.3852/13-051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oso B. A. (1977). Pleurotus tuber-regium from Nigeria. Mycologia 69, 271–279. 10.1080/00275514.1977.12020058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prilleaux M. É. (1889). Le Pachyma Cocos en France. Bull. Soc. Botinique France 36, 433–436. 10.1080/00378941.1889.10830499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raja H. A., Baker T. R., Little J. G., Oberlies N. H. (2017). DNA barcoding for identification of consumer-relevant mushrooms: a partial solution for product certification? Food Chem. 214, 383–392. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redhead S. A., Ginns J. (2006). (1738) Proposal to conserve the name Poria cocos against Daedalea extensa (Basidiomycota). Taxon 55, 1027–1052. 10.2307/25065702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rehner S. A., Buckley E. (2005). A Beauveria phylogeny inferred from nuclear ITS and EF1-a sequences: evidence for cryptic diversification and links to Cordyceps teleomorphs. Mycologia 97, 84–98. 10.3852/mycologia.97.1.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert V., Vu D., Amor A. B. H., Wiele N., van de Brouwer, C., Jabas B., et al. (2013). MycoBank gearing up for new horizons. IMA Fungus 4, 371–379. 10.5598/imafungus.2013.04.02.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman A. Y. (2014). Lessons learned from moving to one scientific name for fungi. IMA Fungus 5, 81–89. 10.5598/imafungus.2014.05.01.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumphius G. E. (1750). Herbarium amboinense, in ed Burmann J. (Amsterdam: Fransicum Changuion and Hermannum Uytwerf; ). [Google Scholar]

- Ryvarden L., Gilbertson R. L. (1984). Type studies in the Polyporaceae. 15. Species described by L.O. Overholts, either alone or with J.L. Lowe. Mycotaxon 19, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ryvarden L., Xu L. W., Zhao J. D. (1986). A note of the Polyporaceae in the Chang Bai Shan forest reserve in Northeastern China. Acta Mycol. Sin. 5, 226–234. [Google Scholar]

- Saccardo P. A., Paoletti G., Berlese A., De-Toni G. B., Trevisan V. B. A. (1889). Sylloge Fungorum Omnium Hucusque Cognitorum, Vol. 8 Padua, 1143. [Google Scholar]

- Schweinitz L. D. (1822). Synopsis fungorum Carolinae superioris. Schriften Naturforschenden Gesellschaft Leipzig 1, 20–131. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestro D., Michalak I. (2012). raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org. Divers. Evol. 12, 335–337. 10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. E., Henkel T. W., Rollins J. A. (2015). How many fungi make sclerotia? Fungal Ecol. 13, 211–220. 10.1016/j.funeco.2014.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Cui B. K. (2017). Phylogeny, divergence time and historical biogeography of Laetiporus (Basidiomycota, Polyporales). BMC Evol. Biol. 17:102. 10.1186/s12862-017-0948-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirin V., Vlasak J., Niemelä T., Miettinen O. (2013). What is Antrodia sensu stricto? Mycologia 105, 1555–1576. 10.3852/13-039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Zhang J., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Li W. (2016). Determination and multivariate analysis of mineral elements in the medicinal hoelen mushroom, Wolfiporia extensa (Agaricomycetes), from China. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 18, 433–444. 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.v18.i5.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. C. (2014). Biological activities and potential health benefits of polysaccharidesfrom Poria cocos and their derivatives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 68, 131–134. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K. (1934). Chemical studies on “Bukuryo”, sclerotia of Pachyma hoelen Rumph. J. Agric. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 10, 103–104. 10.1271/bbb1924.10.103a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibpromma S., Hyde K. D., Jeewon R., Maharachchikumbura S. S. N., Liu J. K., Bhat D. J., et al. (2017). Fungal diversity notes 491–602: taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 83, 1–261. 10.1007/s13225-017-0378-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turland N. J., Wiersema J. H., Barrie F. R., Greuter W., Hawksworth D. L., Herendeen P. S., et al., (eds.) (2018). International code of nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017, in Regnum Vegetabile (Glashütten: Koeltz Botanical Books; ). 10.12705/Code.2018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasaitis R., Menkis A., Lim Y. W., Seok S., Tomsovsky M., Jankovsky L., et al. (2009). Genetic variation and relationships in Laetiporus sulphureus s. lat., as determined by ITS rDNA sequences and in vitro growth rate. Mycol. Res. 113, 326–336. 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R., Hester M. (1990). Rapid genetic identification and map- ping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 172, 4238–4246. 10.1128/JB.172.8.4238-4246.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. M., Liu X. B., Dai Y. C., Horak E., Steffen K., Yang Z. L. (2018). Phylogeny and species delimitation of Flammulina: taxonomic status of winter mushroom in East Asia and a new European species identified using an integrated approach. Mycol. Progress 17, 1013–1030. 10.1007/s11557-018-1409-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Z., Zhang J., Zhao Y. L., Li T., Shen T., Li J. O., et al. (2013). Mycology, cultivation, traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Wolfiporia cocos (Schwein.) Ryvarden et Gilb.: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 147, 265–276. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber G. F. (1929). The occurrence of Tuckahoes and Poria cocos in Florida. Mycologia 21, 113–130. 10.1080/00275514.1929.12016943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White T. J., Bruns T. D., Lee S., Taylor J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, in PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., White T. J. (New York, NY: Academic Press; ), 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayawardene N. N., Hyde K. D., Al-Ani L. K. T., Tedersoo L., Haelewaters D., Rajeshkumar K. C., et al. (2020). Outline of fungi and fungus-like taxa. Mycosphere 11, 1060–1456. 10.5943/mycosphere/11/1/8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willets H. J., Bullock S. (1992). Developmental biology of sclerotia. Mycol. Res. 96, 801–816. 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)81027-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf F. A. (1922). The fruiting stage of the tuckahoe Pachyma cocos. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 38, 127–137. 10.1038/scientificamerican0722-38 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K. H., Cheung P. C. K. (2009). Sclerotia: emerging functional food derived from mushrooms, in Mushrooms as Functional Foods, ed Cheung P. C. K. (Hoboken: JohnWiley & Sons, Inc.), 111–146. [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Yuan Y., Malysheva V. F., Du P., Dai Y. C. (2014). Species clarification of the most important and cultivated Auricularia mushroom “Heimuer”: evidence from morphological and molecular data. Phytotaxa 186, 241–253. 10.11646/phytotaxa.186.5.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhou L. W., Yang Z. L., Bau T., Li T. H., Dai Y. C. (2019). Resource diversity of Chinese macrofungi: edible, medicinal and poisonous species. Fungal Divers. 98, 1–76. 10.1007/s13225-019-00432-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. P. (2016). Fungal DNA barcoding. Genome 59, 913–932. 10.1139/gen-2016-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Meng H., Xiong H., Bian Y. (2014). Biological characteristics of teleomorph and optimized in vitro fruiting conditions of the Hoelen medicinal mushroom, Wolfiporia extensa (higher Basidiomycetes). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 16, 421–429. 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.v16.i5.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Chen L., Li P., Zhao J., Duan J. (2018). Antidepressant and immunosuppressive activities of two polysaccharides from Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 120, 1696–1704. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. L., Zhu L., Chen H., Cui B. K. (2016). Taxonomy and phylogeny of Polyporus group Melanopus (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) from China. PLoS ONE 11:E0159495. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repositories and accession numbers can be found in the article materials.