Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 global pandemic has seen rapid spread, disease morbidities and death associated with substantive social, economic and societal impacts. Treatments rely on re-purposed antivirals and immune modulatory agents focusing on attenuating the acute respiratory distress syndrome. No curative therapies exist. Vaccines remain the best hope for disease control and the principal global effort to end the pandemic. Herein, we summarize those developments with a focus on the role played by nanocarrier delivery.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 vaccine, Nanovaccine, mRNA vaccine

Graphical abstract

1. Overview: pathways toward an effective COVID-19 vaccine

In late 2019, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) first emerged and on March 11, 2020 it was declared a pandemic [1]. Clinical outcomes ranged from asymptomatic infection to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death. The World Health Organization (WHO) named the resultant disease complex coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [2,3]. COVID-19 has negatively impacted the global socioeconomic well-being of the world's population. Global lack of health care, infrastructure, and preparedness has intensified the pandemic's impact [4].

Viral detection, mobilization and control of person-to-person spread served as the primary means for containment. Induction of effective host antiviral immunity against SARS-CoV-2 comes secondary to infection [5,6]. An uncontrolled innate immune response is the signature of virus-induced pro-inflammatory responses for an ARDS. Alveolar macrophage inflammation disrupts cell and tissue homeostasis leading to end-organ lung disease [7,8]. In the absence of a vaccine, virus-induction of adaptive humoral immune responses can attenuate disease progression [9].

A vaccine can elicit protective antiviral responses against SARS-CoV-2. Short of containment it is the most effective means to prevent infection in susceptible people [10]. To this end, there are more than 137 vaccine candidates in development and 23 in Phase 2 or 3 trials [11,12]. One promising candidate BNT162b2 is already approved while several others are soon to be approved for prevention in the United States of America (USA) [13,14]. However, how long an induced immune response remains effective is in question. Final outcomes will depend, in part, on the continuance of a neutralizing antibody response, the limitations seen on viral mutations and the long-term induction of antiviral memory T cell responses [15,16]. The long term efficacy of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine requires limited boosting and divergent geographic, co-morbid and age-associated population efficacy [17]. Efficacy is defined as long-term prevention of viral infection and in halting transmission in broad populations [18].

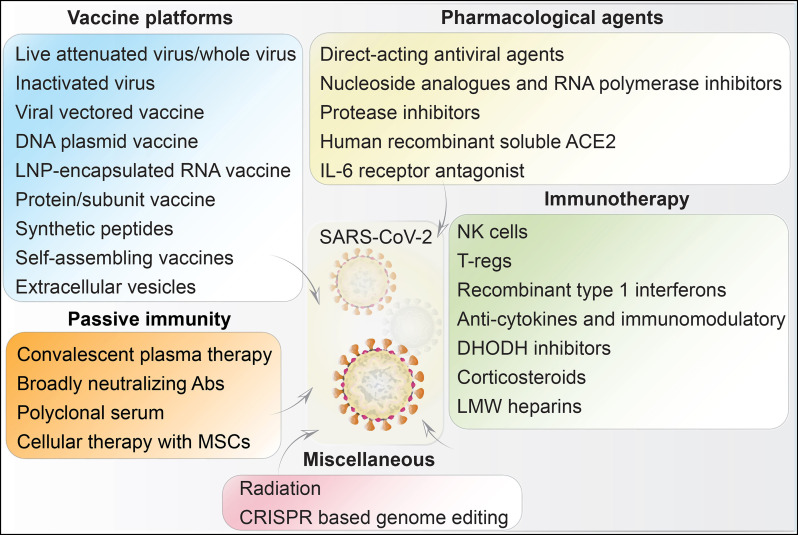

2. SARS-CoV-2 pharmacological agents

Currently, there are no potent effective antiviral therapies available for SARS-CoV-2 [19]. Nonetheless, the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) approvals have sped drug repurposing [20]. Medications now availalbe were developed to treat other viral infections [21,22]. However, newer drugs or drug formulations remain under development. Ongoing efforts are in producing drugs that not only combat viral infection but modulate antiviral immunity [15,23]. Pharmacological agents target parts of the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle [24,25]. In silico viral gene profiles have uncovered prospective medicines that inhibit the viral protease, the hemagglutinin esterase (HE), the spike (S)/envelop (E) proteins, and RNA-dependent polymerases [26]. These and drug candidates that target the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor are major candidates for COVID-19 treatment.

-

i.

Broad-spectrum antiviral drugs: Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is an anti-malarial drug used successfully to treat systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid disease [27]. It has anti-inflammatory activitiese with known control of interleukin 6, 17, and 22 (IL-6, IL-17, and IL-22) cytokines [28,29]. While HCQ received initial global attention based on symptom similarities between malaria and COVID-19, its use for COVI-19 remains controversial [30]. Its “putative” mechanisms of action include alkalization of intracellular pH, inhibition of lysosomal activity of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and effects on cathepsins, mitogen-activated protein kinases, and autophagosomal functions which results in structural damage to SARS-CoV-2 S proteins [[31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]]. HCQ can also attenuate cytokine production and autophagy [39,40]. However, based on variable clinical outcomes and toxicities, the US FDA revoked emergency-use authorization (EUA) for COVID-19 treatments on June 15th, 2020 [41,42].

-

ii.

Protease inhibitors: Lopinavir/ritonavir and other human immunodeficiency virus type one (HIV) proteases were approved by the US FDA for HIV-1 infection. Promising results as an inhibitor of the 3-chymotrypsin-like protease of SARS-CoV-2 were reported [43]. However, use of the drugs for COVID-19 are limited [44]. Darunavir is an inhibitor of HIV-1 protease and cobicistat is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 3A. All, regrettably, are limited against SARS-CoV-2 [45].

-

iii.

Nucleoside analogs and inhibitors: Remdesivir: Remdesivir (GS-5734), a broad-spectrum antiviral drug, acts on the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp) to suppress viral replication. It has activity against coronaviruses and was shown to be effective during the Ebola virus 2014–2016 outbreak and in some SARS-CoV-2 studies [46,47]. At the outset of the pandemic, remdesivir was used for COVID-19 treatments in late stage disease. Early successful reports were reinforced by a more extensive double-blind placebo-controlled study demonstrating shortened times on ventilator assistance precluding improvements in disease mortalities [48,49]. Soon remdesivir received a EUA by the US FDA for COVID-19 that included all age groups independent of disease severity [48,50]. However, on November 9, 2020, a follow on study concluded no clinical benefit for remdesivir in hospitalized patients [51]. Ribavirin: Ribavirin is a guanine nucleoside analog that prevents viral replication by acting on the viral RdRp. To date, there are no published reports on therapeutic efficacy for SARS-CoV-2 with only mild therapeutic benefit in MERS-CoV infections when used with interferon alpha (IFN-α) [52]. Favipiravir (T-705): Favipiravir is known to undergo intracellular activation to favipiravir ribofuranosyl-5-triphosphate (RTP); a purine nucleotide that inhibits viral replication by control of RNA polymerase. Favipiravir has antiviral activity against a spectrum of RNA viruses such as influenza H1N1 and Ebola [53]. Laboratory studies demonstrate antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 [54]. In June 2020, the Drug Controller General of India (DGCI) approved the drug during ongoing clinical trials [55,56]. Other drug candidates under development for SARS-CoV-2 include umifenovir (arbidol), an antiviral drug that interferes with the spike protein-ACE2 interactions. The drug acts by inhibiting cell membrane-SARS-CoV-2 envelope fusion [57].

-

iv.

Immunotherapeutics: Impaired immunity with compromised lung functions and pro-inflammatory cytokine levels are COVID-19 features [5,58]. Adaptive immune dysfunctions include lymphopenia and activation, granulocyte and monocyte dysfunction, and elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG) and total antibody levels [6,59]. These are present in blood and convalescent plasma of infected people [22,60,61]. Control of inflammation is achieved by immune modulation [22,62,63]. Convalescent plasma: Convalescent plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients contains antibodies that can neutralize viral infection [64]. However, adverse events have been reported that include fever, allergic reactions, transfusion-related lung injury, life-threatening bronchospasm and circulatory overload. These are present in patients with cardiorespiratory disorders [65]. A cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was used successfully for USA President Donald J. Trump which now received an EUA [66]. Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC): MSC-based therapy is being developed for treatment of pneumonia [67]. Transplantation of MSCs possesses self-renewal and anti-inflammatory properties resulting in pulmonary epithelial cell repair and defense against a cytokine storm and promotion of alveolar fluid clearance [68]. Regulatory T cells (Treg): The inflammatory processes seen during ARDS-asssociated COVID-19 may be linked to Treg dysfunction. Therefore, Treg therapy may serve to improve oxygenation and attenuate pro-inflammatory cytokines [69,70]. A novel allogeneic cell therapy (CK0802) developed by Cellenkos Inc. consists of Tregs administered to overcome immune dysfunction through resolving chronic inflammation in COVID-19 patients [71]. Such treatments serve to halt respiratory deterioration. IL-6 inhibitor: A key mediator in the COVID-19 cytokine storm is IL-6 [72], a driver of inflammatory responses. Targeting the IL-6/IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) signalling can halt inflammatory activities [73]. Tocilizumab and sarilumab, are humanized anti-IL-6R antibodies that inhibit IL-6 signalling [[74], [75], [76]]. Both are in Phase 3 clinical trials for COVID-19 [12]. Janus kinase (JAK) Inhibitors: Inhibition of the JAK signalling pathway together with IL-6 can ameliorate abnormal cytokine levels [77]. Baricitinib, fedratinib, and ruxolitinib are JAK inhibitors used for rheumatoid arthritis and myelofibrosis. COVID-19 patients treated with baricitinib in combination with lopinavir, ritonavir or remdesivir demonstrated reductions in viral and inflammatory activities [78,79]. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitors: While DHODH inhibitors can suppress viral replication and modulate cytokines they have a low therapeutic index [80]. Others: NK cell-based immunotherapy is less defined for COVID-19 [60,81]. PEGylated IFNα-2α and 2β, can stimulate innate antiviral responses for SARS-CoV-2 [19]. Clinical trial involving combination therapy of PEGylated IFN-α with ribavirin has been reported (ChiCTR2000029387). Camostat mesylate inhibits host transmembrane proteases restricting viral host cell entry [20]. The anti-vascular endothelial factor bevacizumab (used in cancer), the monoclonal antibody eculizumab (used in autoimmune conditions), and a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator fingolimod which sequesters lymphocytes are under study [20,58,82].

3. Herd immunity

Whether the elimination of COVID-19 is possible through herd immunity and vaccines is uncertain [83,84]. Previously, two human influenza viruses (H1N1 and H2N2) disappeared after pandemics explained by herd immunity [85]. The prior pandemics led to global immunity through the aid of highly-effective vaccination. These led to viral elimination. Two pathogenic avian influenza viruses also disappeared through herd immunity and vaccination. However, human person-to-person passage led to viral mutation and an epidemic [86,87]. These events support the idea that SARS-CoV-2 elimination can occur through herd immunity [88] defined as the point at which the proportion of infection in susceptible individuals falls below the threshold needed for viral transmission [89]. When herd immunity begins to take effect, susceptible individuals benefit from indirect protection of infection [83]. For SARS-CoV-2, herd immunity would be determined by: (i) the percentage of the population immune to infection (herd immunity threshold (HIT); (ii) the length and effectiveness of the SARS-CoV-2 immune response; and (iii) the stability of the virus epitopes to mutation [90]. The HIT depends upon the basic reproduction number (R0), the average number of people spawned by the one infected person in fully succeptible mixed populations. The HIT is calculated using formula 1-1/R0 and different mathematical models predicted HIT for COVID-19 closer to 60 to 70% suggesting very high population need to be immune to the infection to achieve herd immunity [84,91]. As of December 10, 2020, 69 million people have been infected and 48 million people have recovered worldwide from the SARS-CoV-2 infection representing 0.90% and 0.62% of the world's population [92]. Therefore, it is far below a significant percentage of the world's population that could become immune to SARS-CoV-2 to confer herd immunity [88]. The Ferguson report estimated that with R0 2.4 the healthcare systems in the USA and the United Kingdom (UK) will incur more deaths then expected. The report suggested strict government interventions to prevent rapid viral spread which were soon implemented in different countries [93]. Sweden experienced rapid spread of COVID-19 without herd immunity and ten times greater number of deaths than neighboring Norway who implemented strict preventive measures. However, in a part of Sweden, Stockholm County, by April 11, 2020, the net hospital admissions decreased significantly when 17% of the population was infected, whether this was due to herd immunity is not clear [94]. To evaluate societal costs in achieving global SARS-CoV-2 herd immunity, the overall infection fatality rate (IFR) need be considered. Understandably, IFR will be lower than the reported case fatality rate (CFR) due to the numbers of asymptomatic individuals. If one combines infection fatality data with numbers of individuals needed to reach HIT, estimations of the expected number of deaths can be determined [83]. Achieving herd immunity remain theoretical [88,95].

Effective antiviral immunity rests in its durability. SARS-CoV immunity can decline over time in levels of IgG, IgM, and IgA neutralizing antibodies [96]. While SARS-CoV antigen-specific memory B-cells decline, memory antiviral T cell responses require sustenance [97]. T cell responses persist >10 years in those who recovered from MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV infections. Whether these are protective is not known [59]. It was demonstrated by computer modeling that immunity against SARS-CoV-2 could be transient. If operative, there is a likelihood that, like influenza A and B viruses, SARS-CoV-2 may lead to biennial or annual outbreaks. Therefore, a need exists to determine the extent and duration of immunity against SARS-CoV-2 [98]. This need is further complicated because the antibody response that is mounted against SARS-CoV-2 is not always accompanied by viral clearance [99]. Antibody levels vary based on age [100], re-infection rates [101], and length of illness. Cases with SARS-CoV-2 re-infection have been reported and virus strains with different genome sequences in a single person [102]. Re-infection is distinguished from relapse and prolonged viral shedding [103]. Although the number of re-infection is limited compared to new infections, re-infection is linked to how long-term neutralizing antibody titers are sustained [104]. Emergence of mutant strains of SARS-CoV-2 and viral epitope stability affect re-infections [105]. COVID-19 has a lower fatality rate than SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections but higher than flu (~3% versus 0.1%) [106]. However, since SARS-CoV-2 is more contagious than the flu, and has spread rapidly across the globe, the 1.5 million deaths from COVID-19 in the past 10 months has already exceeded the total number of deaths from the last five flu seasons [92,107,108]. Viral infections with low fatality rates enable the host to mount an immune response, that create selection pressure for the emergence of mutant virus strains [109]. Considering re-infection, limited immunity, virus mutations and need for herd immunity underlies the importance of vaccination.

4. Viral vaccines

Bacteria and viruses are pathogens that commonly elicit disease [110]. For a successful pathogen to survive and grow, it must have ability to: (i) inhabit the host; (ii) avoid or circumvent host immune responses; (iii) grow by affecting host biological machineries to its benefit; and (iv) transmit itself from one host to another [110,111]. Viral infections possess nucleic acids surrounded by a protein shield. Viruses can also be classified based on various criterias including genetic material, number of nucleic acid strands, envelope, shape, and structure [111,112]. Some viruses contain an envelop whereas some do not. For example, adenoviruses and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are non-enveloped viruses, whereas herpesvirus and coronavirus are enveloped. The viral envelope-membrane, when present, consists of lipid and glycoproteins and it is acquired during detachment of virus from the host cell [113]. Upon exposure, body's immune system mount a specific response enabling the host to be protected upon re-exposure [110,113]. Vaccines harness the body's immune responses providing protective immune responses against infection. Vaccines are broadly available against tuberculosis, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, Haemophilus Influenzae Type b, Haemophilus Influenzae Type b, cholera, typhoid, Streptococcus pneumoniae and viral infections that include influenza, hepatitis, diphtheria, measles, mumps, and polio. Efforts are still under development for chikangunya, dengue, malaria, cytomegalovirus and leishmaniasis [114].

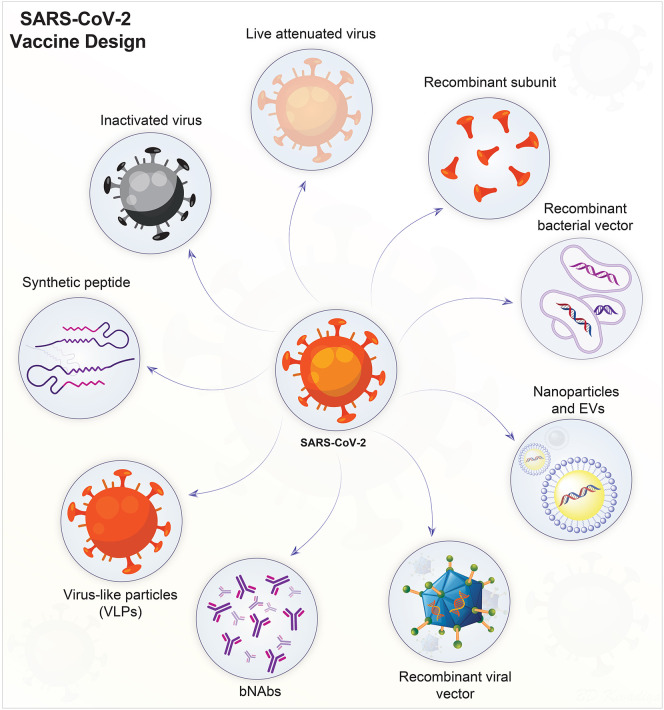

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development had now achieved US FDA approval [12]. What is now available is able to induce long-lasting viral neutralizing antibodies that prevent viral attachment (through a ACE2 receptor) to epithelial cells in the mucosal layers and type II pneumocytes [16,115]. Vaccine should also induce sustained humoral and cellular immune responses which would generate long-lasting memory T cell responses. Further features of an effective vaccine include ease of administration (single dose, mucosal), storage, production, and scale-up [15,116]. The spike (S), nucleocapsid (N), membrane (M), and envelope (E) glycoproteins are known immunogenic proteins for SARS-CoV-2. The spike S protein is the major target for vaccine development, as it is involved in the viral entry via ACE2 receptors [115,117]. Several COVID-19 vaccine candidates have or are being developed. Viral vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 include: (i) live and attenuated; (iii) inactivated; (iv) nucleic acids; (v) viral vectors (self- and non-replicating); and (vi) protein and subunits; (Fig. 1 ). These can be propagated in animals, chicken embryos, and cell cultures and tissues [118,119]. Currently vaccines are approved for marketing in different countries to control more than 30 infectious diseases [120]. Vaccines are monovalent, effective against a single antigen or a pathogen (Rotarix) and polyvalent/multivalent, effective against strains of the same pathogen (RotaTeq) [116,121].

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine designs. Live-attenuated viruses are produced by serial passage in relevant tissue culture systems. Virus inactivation is produced by radiation, heat, or chemical treatments. Both live-attenuated and inactivated viruses are capable of inducing protective antiviral immune responses. Viral vectors are employed to deliver specific antigens through the genome of another virus. DNA vaccines, carried by recombinant bacterial vectors, are generated in relevant microorganisms or in cell cultures. When injected into a host they provide relevant virus-specific protein synthesis needed to generate an immune response. Recombinant subunits are antigenic determinants of SARS-CoV-2, obtained by recombinant DNA technology. VLPs contain no genetic materials but resemble the SARS-CoV-2 virus by virtue of specific surface antigenic proteins. Broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) are capable of binding to multiple conserved sites on viral spike proteins obtained from different viral strains, and thereby prevent virus neutralization escape. They may also function to attenuate virus evolution. Synthetic peptides can be designed to inhibit the receptor-binding domain (RBD) on the spike protein that is crucial for SARS-CoV-2 to gain host cell entry. Nanoparticles and extracellular vesicles (EVs) are the emerging technologies for the degevelopment of safer vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Nanoparticles are decorated with antigenic molecules, while EVs serve as natural carrier of viral proteins, wherein both inducing antiviral immune responses.

4.1. Live attenuated

These use live viruses to elicit protective immune responses. India and China use a live virus vaccine to boost small pox immunization. They expose people to material obtained from patients infected with a mild virus form [121,122]. Live vaccine raises the possibility of viral virulence reversal [123]. Therefore, live virus vaccines need be developed by altering the viral genome and selecting non-pathogenic mutant strains incapable of causing disease [124]. Live virus vaccines can also be produced by viral attenuation. These are viruses weakened in their pathogenicity but can elicit antiviral immune responses without causing disease. One of the most widely used strategy is serial passages of virus in chick embryo fibroblasts and vero cells. This is a well accepted practice for the vaccine development [125,126].

As the virus replicates through each passage, it loses virulence [119]. Attenuated viral vaccines against measles, mumps, and chickenpox were developed [127]. Another means used to generate live attenuated vaccines involves deletion or viral gene mutation essential for viral growth. These defective viruses cannot replicate in a human host [128] but can induce immune responses [129]. The first replication-defective live viral vaccine was developed against herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) [130,131]. Replication-defective HSV-2 missing the genes essential for viral DNA synthesis was produced [132]. Another approach is to grow virus at reduced temperatures. Attenuated viruses can also be developed by inserting viral proteins into an attenuated cold-adapted virus [133]. Live attenuated virus induce no or limited infection [134]. However, these strains show an ability to induce herd immunity by shedding of viral particles and by host to host transmission. Live-attenuated vaccines are capable of eliciting illness in the immunosuppressed individuals [123]. To overcome this limitation, codon deoptimization is used. Codon deoptimization vaccines are completely safe due to substitution of several nucleotides from the virus coding sequence [135,136]. Recently, live attenuated vaccine was produced against Ebola and found to be >97% effective in 90,000 individuals [137]. Currently, Griffith University in collaboration with Indian Immunologicals Ltd. developed codon deoptimized live attenuated vaccine for SARS-CoV-2. The vaccine can induce long lasting protective immunity after single dose without cross reactivity to MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV [138]. Existing vaccine manufacturing facilities are capable to develop live attenuated vaccine for large scale production [139].

4.2. Inactivated viruses

These viruses are inactivated by radiation, heat, and chemicals such as binary ethyleneimine and formalin. This leads to an inability to cause illness. However, inactivated viruses maintain the ability to induce host immunity that recognize and destroy pathogens. This vaccine type contain viral particles from inactivated virus and hence do not develop pathogenicity [116,140]. The inactivated vaccine developed against poliovirus is an example, where virus is inactivated by formaldehyde treatment. Due to inactivated vaccine development, no new polio infection cases have been reported since 1999 and as a result disease eradication was declared in 2015 [141,142]. Another examples of an inactivated vaccine are those for typhoid, rabies, influenza and hepatitis A [120,143]. Such vaccines have set regulatory requirments for short-term protection as they, as a group, generate a weaker immune responses and require more frequent boosters for long-term immunity than other vaccine candidates. On balance, they are relatively stable and do not require refrigeration and can be freeze-dried and easily transported. Inactivated vaccines are boosted with adjuvants, such as saponins, alum, immune complexes and liposomes [124,144]. Currently, nine SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are being developed using this technology. Sinovac Biotech is developing inactivated vaccine PiCoVacc which is now known as CoronaVac against SARS-CoV-2 and this candidate induces broad neutralizing antibodies against ten different viral strains in multiple species that include primates. After three immunization of CoronaVac (6 μg per dose), complete protection was observed in macaques challenged with SARS-CoV-2 [145]. CoronaVac has already been tested in the human Phase 1/2 trials. 142 healthy volunteers were enrolled in Phase 1 while 600 healthy volunteers were enrolled in Phase 2 studies. CoronaVac was found safe and well tolerated in all studies. The neutralizing antibody titer rate was above 90%, confirming a robust protective immune response against SARS-CoV-2 [146]. Currently, Sinovac Biotech is studying CoronaVac in Brazil in collaboration with Instituto Butantan in a Phase 3 clinical trial where 90,000 healthy participants are or soon to be enrolled [147]. Another inactivated vaccine Covaxin is developed by the Indian Pharmaceutical company Bharat Biotech in collaboration with the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and National Institute of Virology (NIV). Preliminary results of a Phase 1/2 clinical trial showed that Covaxin is safe and effective. Currently, a Phase 3 trial with Covaxin is ongoing with 26,000 participants [148]. Other inactivated vaccine candidates are being developed by Beijing Institute of Biological Products in collaboration with Sinopharm and was found safe and able to generate a high antiviral antibody titer among participants as observed in a Phase 1/2 clinical trial [149]. Currently, a Phase 3 trial in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in 15,000 participants is ongoing [147].

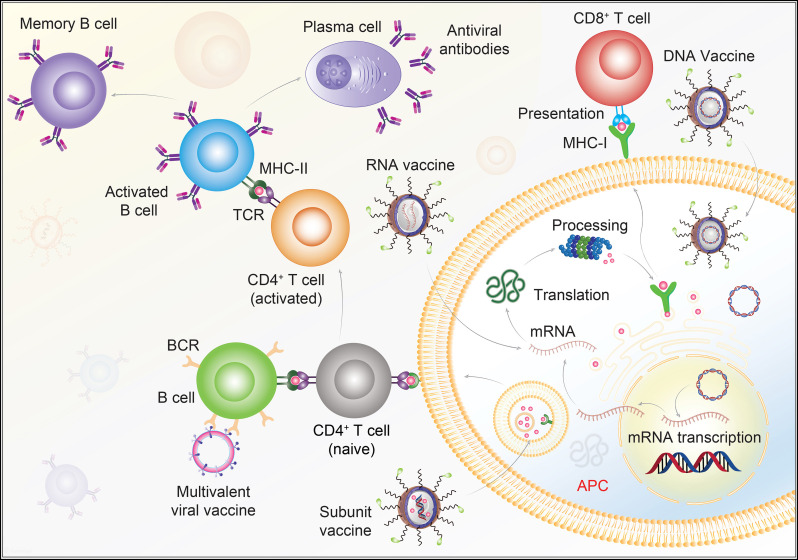

4.3. Nucleic acid – DNA

DNA vaccines are a harmless complement to conventional live- and inactivated-virus vaccines [120]. DNA vaccines are generally safe and stable compared to conventional vaccines because the vectors used are non-replicating and express only the antigen of interest. Therefore, unlike viral vector vaccines, they are not able to revert to the disease-causing form. DNA vaccines also lack vector induced immunity which allow their use with other vaccines in the same individual [150]. In short time intervals, DNA vaccines are produced in bulk quantities. Additionally, such types of vaccines can provoke both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses but at lower levels when compared to conventional vaccines. Maintaining high-level protein expression is challenging with this platform (Fig. 2 ) [151]. Under the transcriptional control of the CMV/R promoter, a West Nile virus DNA vaccine was shown to be safe and well tolerated [152]. A DNA vaccine against Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) [153] and Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) elicited strong immune responses that protected mice and non-human primates after viral challenge [154]. Recently, the EBOV-GP DNA vaccine was shown to induce long-term immune responses and neutralizing antibodies in nonhuman primates [155]. A HIV-1 DNA vaccine DNA-4, which encodes the Pol(rt), gp140, Nef, and Gag proteins of HIV-1, was found to be safe, well-tolerated and capable to induce robust immune responses [156]. DNA vaccines from the envelope (E), ectodomain (domains I, II, and III), and the non-structural 1 (NS1) protein of dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV2) protected against lethal DENV2 challenges [157]. A DNA vaccine encoding the SARS-CoV S-protein induced T cell and neutralizing antibody responses in animals [158]. Despite the encouraging preclinical outcomes, no DNA vaccines yet are approved for human use based on their regulatory uncertainty. A vaccine candidate developed in this platform must have to go through vigorous regulatory process that could delay approval. Currently, three DNA vaccine candidates are under investigation for COVID-19. Inovio Pharmaceuticals with the International Vaccine Institute and Korea National Institute of Health are developing the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine INO-4800, using a DNA-based platform. In Phase 1 clinical trial with 40 healthy voluenteers, 94% participants showed protective immune responses six weeks after two doses (1 and 2 mg) of INO-4800. After the early encouraging results, Inovio is now recruiting healthy participants for a Phase 2/3 trial [159]. The India-based pharmaceutical company Zydus Cadila is investigating a plasmid DNA vaccine candidate ZyCov-D for SARS-CoV-2. After seeing protective immmune responses in mice, rats, guinea pigs and rabbits, investigators are recruiting healthy voluenteers for a Phase 1/2 trial [160]. Genexine Inc. is developing DNA vaccine GX-19 for COVID-19 with the support of the Korean Government. Currently, recruitment of 120 healthy volunteers is under progress to initiate a Phase 1 clinical trial [161].

Fig. 2.

Schematics for vaccine-induced antiviral immunity. DNA vaccines carry viral genes, which are released inside the target APCs. The inserted genes are transcribed, then translated to antigenic viral proteins that are either presented through the APC to CD8 T cells through MHC-I TCR interactions. Alternatively, the viral protein of interest is presented to CD4 T cells by MHC-II TCR interactions. Cytotoxic CD8 T cells kill infected cells and B cells make antibodies by CD4 T cell dependent activation. These released antibodies are directed to target specific viral antigens. RNA vaccines incorporate mRNA into target APCs and undergo parallel pathway events once the immunogenic proteins are synthesized. Subunit vaccine consists of the antigenic determinants of the viral pathogen, which enters the target cells and subsequently releases the specific viral subunits. The subunits are engulfed into endosomes, which when fused with the membranes, present the viral antigens to the CD4 T cells for both T- and B- cell mediated antiviral immunity. Multivalent viral vaccines are also designed to display multiple antigens in order to enhance immunogenicity. Abbreviations; Antigen presenting cells, APCs; class I major histocompatibility complex, MHC-I; class II major histocompatibility complex, MHC-II, T-cell receptor,TCR; B-cell receptor, BCR. The illustration is prepared in-house and schematic ideas and technical details were followed as presented in previous published report [17].

4.4. Viral vectors

Vector-based vaccines are kind of live attenuated vaccines which use available viral vectors with known safety profiles. Vectors deliver specific gene that encodes for a specific antigen. When viral vectors are injected, a gene of interest transcribes a specific antigenic protein, and thereby elicits immunity. Vectors do not require adjuvants and are capable of eliminating virus-infected cells by inducing a cytotoxic T cell (CTL) responses [[162], [163], [164]]. Existing viral vectros can be divided into two categories: replicating (replication-competent) and non-replicating (replication-deficient). The replicating viral vector produces infectious viruses capable of infecting target cells to produce viral antigens. The most widely used replicating vectors include the measles and the vesicular stomatitis virus, both are single-stranded, and antisense RNA viruses able to deliver heterologous antigens that can induce both cellular and humoral immune responses [165]. The major advantage of the measles virus vector (MVV) is that it elicits life-long cellular and humoral immunity. Due to helical structure of measles virus, vectors prepared from it can tolerate insertion of genes over a size of 6Kb and vectors are stable even after multiple passages [166].

The recombinant versions of replicating viral vectors have better safety profile and superior infectivity over their native form. Recombinant MVV can elicite broad neutralizing antibodies against multiple conserved epitopes of viral spike proteins of divergent strains and therefore precluding virus escape [167,168]. Recombinant MVV is also known for more specific targeted antigen delivery to the macrophages and can be used as multivalent vector for HIV-1, West Nile virus, and others [169,170]. In contrast, non-replicating viral vectors include adenovirus, adeno-associated virus (AAV), herpes virus, and alpha virus. Originally, they were developed from simian adenoviruses and some other pathogens such as Ebola virus, RVFV, and Zika virus [171]. Adenovirus-based viral vectors are most commonly used. The E1A and E1B genomic regions of adenovirus are replaced by genes encoding target viral antigens [172]. Adenoviral vectors can express gene inserts of size over 8Kb, and hence can be used to generate multivalent vaccines [173]. Adenoviral vector Ad5 can provoke CD8 T cells and strong antiviral responses and provide ease of large scale production [174,175]. Other adenovirus-based vectors (Ad26 and Ad35) are candidates for HIV-1 vaccine due for their abilities to infect functional memory T cells [176,177]. The key advantages of non-replicating adenovirus vectors include ease of genetic alterations, stability, safety, higher growth rate, strong immune response, and thermostability [178].

In spite of structural similarities, AAV display improved stability over adenoviruses. The protein coverings of a virus (capsid) and specific activating protein assembly facilitate their targeted delivery potential [179,180]. The recombinant AAV vectors (rAAV) are superior over native AVV where the Rep and Cap genes of AAV are replaced with the genes encoded for target antigens to elicit neutralizing antibodies [181]. AAV-based vectors are used as a tool in gene therapy for the treatment of various disorders like muscular atrophy, inherited blindness, and haemophilia [182]. Despite advantages, viral vectors have several limitations. Vector induced immunity is common with this technology that reduces the efficacy of the vaccine. Host genome integtation is another key limitation with viral vector leading to the risk of tumorigenesis. Also certain viral vectors like AAV have low titer production which become limiting step in bulk vaccine production. However, due to highly specific delivery and long lasting immune response after single administration, viral vector platform is still well accepted and in the past this technology has shown successful eradiation of smallpox [162]. Technological developments have increased host immune responses as well as the large-scale production of viral vectors that ease the regulatory requirements of this technology [116].

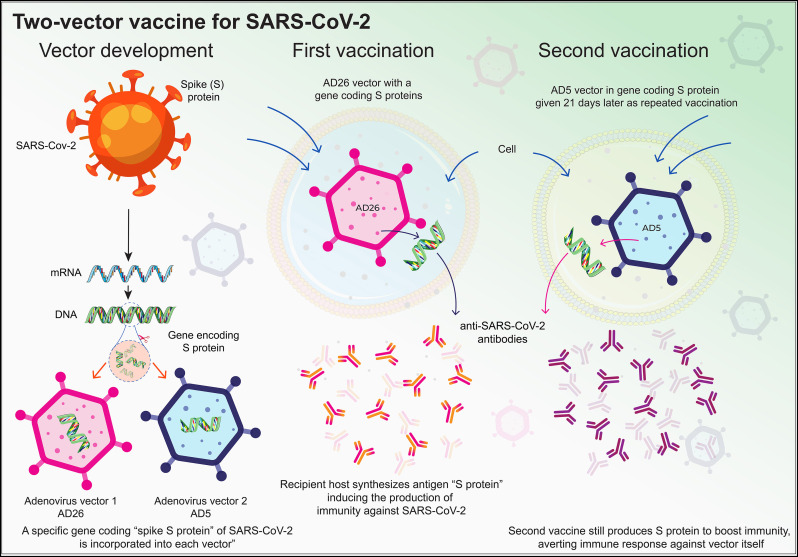

Currently, many COVID-19 vaccines are under development with this technology. AD26 associated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 showed complete protection in rhesus macaques after infection [183]. Thereafter, a series of AD26 vectors encoding different SARS-CoV-2 spike protein epitopes were developed with encouraging outcomes [184,185]. Recently, Russia approved a COVID-19 vaccine Sputnik V exhibiting two different adenovirus vectors (rAd26 and rAd5), both carrying the gene for SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein (rAd26-S and rAd5-S) (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Two-vector viral vaccines. Developed by Gamaleya Center in Russia, two-vector vaccine, as the name suggests, uses two different vectors (Ad5 and Ad26). Vector development involves the use of S-protein mRNA to generate the complementary DNA, followed by insertion of this S-protein encoding DNA into adenoviral vectors, Ad26 and Ad5. Ad26 vector encoding S-protein was administered as first vaccination followed by a booster dose of Ad5 vector encoding the same S-protein 21 days later. Inside the recipient, these vectors generate the S-proteins, which upon entering the circulation induces protective immunity. The illustration is prepared in-house and schematic ideas and technical details were followed as presented in previous published report [186,187].

The premature decision was made after the encouraging results of Sputnik V in Phase 1 and Phase 2 clinical trials, with just 38 participants in each study [186]. In Phase 1 study, both rAd5-S and rAd26-S vaccines were found safe and well tolerated for up to 28 days. In Phase 2 study, rAd26 was administered on day 1 followed by a booster dose of rAd5 on day 21 where 100% of the participants showed seroconversion and high SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer than COVID-19 convalescent plasma. Both antigen-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells were observed in all the participants [186]. However, large-scale Phase 2 clinical trial results are needed for US FDA approval and to vaccinate the general population with Sputnik V [187]. Other COVID-19 vaccines developed using this technology include Ad5-nCoV, AZD1222, aAPC, and LV-SMENP-DC. Ad5-nCoV, developed by CanSino Biologics Inc., is the first vaccine to reach Phase 2 clinical trial. In Phase 1 clinical trial, Ad5-nCoV was found well tolerated and immunogenic in 108 participants 28 days post vaccination [188]. In Phase 2 study, single immunization of Ad5-nCoV induced significant SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and immunogenic response in all 508 participants [189]. Ad5-nCoV has already been approved for the military use in the China and currently it is under Phase 3 clinical trial investigation in russia [190]. AZD1222, formerly known as ChAdOx1-S is being developed by the University of Oxford with AstraZeneca. Currently, Phase 2/3 clinical trila is ongoing but the interim results of Phase 2 study showed better tolerance of AZD1222 in older adults compared to the young adults with equivalent immunogenicity across different age groups 28 days after single booster immunization. To note, when tested in the animlas, no complete protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection was observed [191]. AZD1222 is the first vaccine candidate being investigated in the Phase 3 clinical trial. Previously, Phase 3 study of AZD1222 was put on hold after suspected serious adverse reactions in the UK trial participants which is now resumed after recommendations of the independent safety review committee and the United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency [192]. AstraZeneca has agreement with Europe's Inclusive Vaccines Alliance to supply 400 million doses of AZD1222 by the end of 2020 [193]. Vaccines aAPC and LV-SMENP-DC are made by Shenzhen Geno-Immune Medical Institute which are currently in Phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT04276896).

4.5. Protein and subunits

These vaccines utilize viral proteins or protein fragments and able to elicit strong humoral and cellular CD4 and CD8 T cell antiviral responses (Fig. 2). Currently, many vaccines are under development which are based on the protein subunit technology. Such vaccines devoid of using infectious virus and instead use purified specific antigenic component, therefore eliminate isssues of virus attenuation/inactivation or virulence reversal to offer better safety profile compared to the other viral vaccines [194]. However, like other viral vaccines, protein subunit vaccines have limitations, major one is limited efficacy. In this technology, the isolated antigenic fragment of the pathogen likely denatured that conjugate with untargeted antibodies leading to the diminished efficacy [195]. Hovever, recombinant DNA technologies have successfully overcome such limitations as evidenced by the approval of first recombinant protein subunit vaccine against hepatitis B which has now controlled the disease to near elimination [196]. It has also open the way for regulatory relaxations for the vaccines developed by this technology [197]. Furhther advancements made in this vaccine technology make them more suitable for the immunocompromised individuals. For the production of recombinant proteins, E.coli [[198], [199], [200]] and yeasts are used [200,201].

Several protein subunit vaccines are marketed against diseases including influenza, HPV, and hepatitis B [202]. To improve immunogenic action of such vaccines, diverse formulations of vaccines with potent adjuvants have been employed [144]. The subunit vaccine for hepatitis B is an example of a single antigen-containing subunit vaccines, whereas influenza vaccine is an example of a subunit vaccine that contains two antigens (haemagglutinin and neuraminidase) [124,197,198,203]. Large scale production of purified antigenic protein is also challenging which can be improved by various expression systems including plant-based [204]. Envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) were expressed in insect cells as well as in bacterial expression systems to develop subunit vaccines effective against CHIKV [205]. The subunit vaccines developed from the capsid protein (CP) of astrovirus, protected mink litters against astrovirus infection better than the whole CP [206]. Recombinant subunit vaccines against herpes zoster showed significant reduction in the risk of post therapeutic neuralgia [207,208]. Currently, several vaccine candidates have been developed using this technology against COVID-19 focused on the SARS-CoV-2 S protein or specific domain within the S protein such as receptor binding domain (RBD). The University of Queensland in collaboration with GSK and Dynavax is developing stabilized pre-fusion recombinant protein subunit vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 using its Molecular Clamp technology that lock the SARS-CoV-2 specific protein in the three-dimentional shape with ability to develop humoral immune response against appropriate viral epitopes [12]. Novavax has developed a protein subunit vaccine, NVX-CoV2373 by combining its nanoparticle technology. The recombinant pre-fusion SARS-CoV-2 S protein is expressed in the Baculovirus system and uses Matrix-M adjuvant to enhance the protective immune response against SARS-CoV-2 S protein. Novavax is planning to initate Phase 1 clinical trial after encouraging observations in the animal studies where NVX-CoV2373 induced high levels of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 S protein [209]. MigVax Ltd. has developed oral subunit vaccine technology against poultry coronaviruses and now it is developing COVID-19 vaccine with this technology [210].

5. Cell-based

Deployment of CTL is a promising vaccine approach for different pathologies. T cell's unique T cell receptors (TCRs) recognize and activate against viral-specific antigens which drive immune responses [211,212]. Adoptive transfer of virus epitope-specific T cells showed protective immune responses against various viral infections including adenovirus [213], Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [214], human cytomegalovirus (CMV), etc [215]. Antigen-targeted TCRs have limitations of cross-reactivity and induction of autoimmunity [216]. To overcome such limations, recently combination immunotherapy has been applied for the treatment of various cancers and chronic viral infections where antigen targeted cells are delivered along with other immunemodulators [217]. During viral infection, activated T cells express the programmed death (PD-1) and other inhibitory receptors that make T cells dysfunctional. To overcome such problems, antigen-targeted T cells should be administered alongside the anti-PD1 antibody, otherwise inhibitory receptors are genetically ablated to better control the viral infection [[218], [219], [220], [221], [222]]. Another cell-based vaccine approach uses whole cells or cell lysates as a source of antigen or as a platform to deliver antigens. Virus infected cells are irradiated or healthy cells are transfected with a virus to provoke humoral and cellular immune responses where endogenous dendritic cells (DCs) play a vital role in the development of neutralizing antibodies [223]. DCs are potential candidate for the cell-based vaccine. DCs play an intermediate role between the innate and adptive immunity. DCs sense foreign antigens, processs and represent them to the T cells to contribute protective immune responses [211]. Like T cells, DCs can be manipulated ex vivo to confirm antigen specificity. DCs can be modified by different technologies such as loading of DCs with the immunogenic viral protein, transfection with viral protein, or loading with viral mRNA, each strategy induce vaccine of different potency. DC-based vaccines can also be incorporated with the immunomodulatory agents or their gene to improve therapeutic outcomes [224,225]. DC-based vaccine PROVENGE (sipuleucel-T), loaded with a prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP)-granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) fusion protein has proven effective in patients with prostate cancer [226] and became the first US FDA approved DC-based vaccine for prostate cancer [227]. Because of such favourable immunotherapeutic activities, DCs have been targeted for the development of vaccines against a range of infectious diseases. However, cell-based vaccine development is complex, labor-intensive, and expensive. Large scale production is challenging compared to the traditional viral vaccines to fulfill the global demand in case of COVID-19. FLUCELVAX is the only cell-based vaccine approved by the US FDA for the influenza infection. The FLUCELVAX produces better protection in the people above 65 years of age compared to the traditional flue vaccines. Effective cell banking ensures adequate supply of cells to scale-up FLUCELVAX in case of emergency [228]. University of Manitoba is developing DC-based vaccine for COVID-19 which is currently under preclinical development [229].

6. Adjuvants

COVID-19 containment can only be achieved using effective vaccine strategy. Different technologies used for COVID-19 vaccine development have their own limitations. The inactivated and subunit vaccines often exhibit low immunogenicity therefore frequent booster dose administration is required. Also the effectiveness of the nucleic acid vaccines is questionable due to lack of any licensed vaccines for the human use [230,231]. The globally spread COVID-19 has affected a large population of all the ages due to lack of appropriate prophylactic measures. To fullfill the overwhelming demand in COVID-19 pandemic, a vaccine with high immuniogenicity, faster onset of action, low toxicity, and minimal dose injection is primary requiremet. All outcomes can be achieved by incorporating suitable adjuvants. [232]. A formulation or an immunostimulatory reagent which is designed to improve the performance of a vaccine is adjuvant. Adjuvants enhances antigen-specific protective immune responses and targeted antigen delivery of a vaccine and therefore reduce vaccine dose and associated toxicities [233,234]. An ideal adjuvant should offer heterologous antibody response, potential to kill or neutralize diverse pathogens, and effective T cell responses [235,236]. Moreover, adjuvants should be cheap and widely available with good biodegradable and biocompatible properties [237]. Strategies developed specifically for viral vaccine adjuvants are broadly classified based on formulation and composition which include Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, aluminium formulations, and emulsions, all have been tested preclinically in the coronavirus vaccines as discussed below.

6.1. Toll-like receptor agonists

APCs recognize viral antigenic peptide which serve as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) through various pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Toll like receptors (TLRs) of different subtypes are known as PRRs. Activation of TLR lead to induction of robust humoral and cellular immune responses against invading pathogen. Therefore, use of small molecules that activate TCRs on the APCs are frequently incorporated in the vaccine to improve immune responses [238]. Due to ability to directly interact with the APCs and B cells, TLR agonists amplify the innate and adaptove immune responses [239]. Few examples of the TLR agonists are monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL, a derivative of Salmonella Minnesota R959) (TLR4), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (TLR4), bacterial DNA (TLR7/8), and cysteine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) oligonucleotide (TLR9) which serve as PAMPs [240]. MPL is effective in eliciting both humoral and cell-based immunogenicity and capable of inducing Th1 and Th2 type responses, has been approved in the human vaccines for hepatitis (Fendrix®), HPV (Cervarix™), and malaria (Mosquirix) [241]. SARS-CoV RBD subunit vaccine (S318-510) elicited immune responses were potentiated by incorporating adjuvant alum inducing Th2 cells mediated immune responses. Addition of CpG oligonucleotide in the alum adjuvanted vaccine added Th1 responses and offered dual immune arm activation [242]. Similar dual immune induction was observed with the MERS-CoV N terminal domain (NTD) vaccine upon incorporation of CpG oligonucleotide with aluminium [243]. UV-inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine has reported to induce systemic proinflammation leading to eosinophil infiltration in the animal lungs. Such limitations of inactivated vaccines can be successfully overcome by addition of TLR agnist LPS [244].

6.2. Aluminium

Aluminium hydroxide or alum is the most commonly used adjuvant in the vaccine formulations. Alum adjuvant has been used in the licensed vaccines for the human use against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and hepatitis [245]. Insoluble aluminium salts were the first generation of vaccine adjuvants founded on the discovery of an alum-precipitated diphtheria toxoid suspension. They show improved immunogenicity compared to soluble toxoid [246,247]. The performance of aluminium adjuvant, in part, depends on the composit concentration and absorption of the antigen on a preformed aluminium gel [248]. Alum adjuvants form depot at the injection site followed by slow release of the target antigen to enable its prolonged interactions with the APCs. Alum adjuvants also facilitate antigen uptake of the APCs to activate T cell responses [249]. A SARS-CoV viral vaccine sequencialy inactivated by formaldehyde and UV induced high antibody titer against S protein and neutralizing antibodies in the mice whereas the protective effects were improved by the adjuvant aluminium hydroxide [250]. A SARS-CoV inactivated vaccine induced dose dependent neutralizing antibody responses in the mice and protected them from the viral infection. Such protective effects of vaccine were further improved upon addition of alum adjuvant [251]. Alum in combination with CpG oligonucleotide had demonstrated enhanced humoral and cellular responses in the mice immunized with either inactived or S-based or RBD-based MERS-CoV vaccines [252,253].

6.3. Emulsions

A decade after the discovery of alum-based formulations, emulsion adjuvants were developed by Freund [254]. Emulsions are a dispersion of two or more immiscible liquids composed of oil, emulsifiers, and excipients [255]. Emulsions are broadly categorized into two types: water-in-oil and oil-in-water. Both emulsion adjuvants are similar in physical structure, dimensions, follow an extended time of presence at the injection site and prolonged antigen release. Emulsion adjuvants have been demonstrated to activate APCs and improve their antigen uptake. They also promote APCs migration to the target tissue to induce robust CD4 and CD8 T cell responses [256]. MF59 is an oil-in-water emulsion adjuvant, consists squalene and Tween 80 and Span 85 surfactants. In 1997, the Fluad® vaccine adjuvanted with MF59 was first approved for seasonal flu in Europe. Other marketed influenza vaccines consist MF59 as an adjuvant are Focetria® and Celtura® [257]. MF59 when used with the cationic lipid 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) has improved the antibody responses offered by different DNA vaccines compared to the unadjuvanted DNA vaccines [258,259]. SARS-CoV inactivated vaccine induced S protein specific antibodies and Th2 biased immune responsese were potentiated by the adjuvant MF59 leading to improved viral protection of mice [260]. A SARS-CoV inactivated vaccine induced neutralizing antibody and T cell responses were boosted by the MF59 but not CD8 T cell responses [261]. A MERS-CoV RBD subunit vaccine (S377-588-Fc, S377-588 protein fused with Fc of human IgG) induced detectable neutralizing antibodies and T cell responses in the mice. When vaccine efficacy assessed in the presence of different emulsion adjuvants, Freund's adjuvant, aluminium, montanide ISA51, MF59, and monophosphoryl lipid A; MF59 was found as the most potent adjuvant to substantially improve immune responses [262]. W805EC is an oil-in-water nanoemulsion which is formulated without squalene can substantially improve the protective spectrum of influenza vaccine [263]. Hemagglutinin influenza vaccine with glucopyranosyl lipid A (GLA) oil-in-water emulsion showed improved immune responses in mice [264]. AF03 is a squalene-based emulsion adjuvant present in the marketed influenza vaccine Humenza® [265]. AS01 and AS03 are oil-in-water emulsions developed by GlaxoSmithKline. AS01 consists of MPL and a saponin-based molecule (QS-21) while AS03 consists of α-tocopherol, squalene, and polysorbate 80. The influenza vaccine Pandemrix® is adjuvanted with AS03 to induce antigen-specific immune responses [266]. An inactivated SARS-CoV whole virus vaccine induced high neutralizing antibody titer in the mice after two dose administration. However, vaccine adjuvanted with either AS01 or AS03 showed early and robust antiviral responses where AS01 performed slightly better compared to the AS03. Additionally adjuvanted vaccine offered complete protection of hamsters against wild-type SARS-CoV infection [267]. Montanide series emulsions (ISA-51, −206, −720, etc) are metabolizable squalene-based water-in-oil emulsions. Such adjuvants eliminate the cytotoxic effects of Freund's adjuvant due to their biodegradability [268,269]. A SARS-CoV DNA vaccine expressing recombinant NTD induced antigen-specific CD8 T cell responses and neutralizing antibodies in mice. Co-administration of adjuvants montanide and CpG further improved vaccine performance [270]. MERS-CoV RBD vaccine induced high neutralizing antibody titer and protcted mice against viral challenge when adjuvated with montanide ISA-51 [271].

Few COVID-19 vaccine studies have discussed the adjuvant used in their formulation. NVX-CoV2373 is a recombinant (SARS-CoV-2) S protein nanoparticle vaccine uses Matrix-M, a saponin-based adjuvant, in the formulation. Matrix-M improved the recruitment of APCs at the site of injection and thereby increase T cell activation in the nearby lymph nodes [272]. A COVID-19 vaccine developed by the molecular modeling approaches, COVAX-19 is formulated with the Advax adjuvant which is a novel microcrystalline polysaccharide particle engineered from the delta inulin, potentiated the immunostimulatory potential of co-delivered antigen recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S protein [273]. In BNT162b1, an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, mRNA itself serve as an adjuvant and therefore allow synchronized delivery of antigen and adjuvant [274]. The lipid nanocarriers used in the formulation of vaccines can also serve as adjuvant. The dicetyl phosphate when incorporated into the nonovaccine against diphtheria toxoid improved the protective immune responses by serving as an adjuvant [275]. Overall, the adjuvants with desired properties are critical for effective vaccine delivery.

7. Nanovaccines

Nanoparticles share size distribution with the viruses and therefore like viruses, nanoparticles can enter the virus targeted cells. Nanoparticles can be loaded with the antigen in the form of nucleic acids (DNA and mRNA) or the protein subunits and therefore allow targeted expression or direct delivey of viral antigen. Recently nanoparticles have gained significant attention for the development of effective vaccines against various pathogens including SARS-CoV-2. For effective vaccine responses both innate and adptive immune system should be activated synchronizely which has now successfully achieved with the help of innovative nanovaccine formulations such as solid-lipid nanoparticles, liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, protein nanoparticles, and virus-like particles (VLP) [17,276]. Adjuvants pay a vital role in the nanovaccine mediated desired immune responses by assisting antigen delivery to the target APCs and reduce off-target side effects. Targeted antigen delivery reduces the dose of vaccine required to elicite effective immune response which is very essential consideration for the development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to achieve global demand [276,277,278]. Following approaches are used for antigens and adjuvants codelivery, (i) direct conjugation of antigen and adjuvant, (ii) encapsulation within or decorated onto the nanoparticle, and (iii) use of delivery vehicle as adjuvant. Nanovaccine formulations can enhance antigen stability by maintaining native confirmation and protect them from proteolytic degradation [279]. In the promising mRNA based COVID-19 nanovaccine BNT162b, the trimerized confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 RBD and pre-fused confirmation of S protein are maintained and secreted from the nanoformulation to allow induction of broadly neutralizing antibodies [280]. Nanovaccines further offer advantage of sustained release of target antigen due to their enhanced lipophilicity [281]. In addition to the unique physicochemical characteristics, nanoparticles allow flexibility of surface engineering by incorporating cell-targeting peptides, proteins or polymers on their surface (Fig. 4 ) [282,283]. Delivery of the antigen to the lymphatic system is the frontmost requirement for vaccine efficacy. Nanovaccines have ability to cross the intestinal space and reach the lymphatic tissue. Intranasal delivery of nanovaccine can easilty target the lymph nodes nearby the lung which would be advantageous for fighting against COVID-19 [283,284]. Such properties make nanovaccines a versatile delivery vehicle for the treatment of COVID-19.

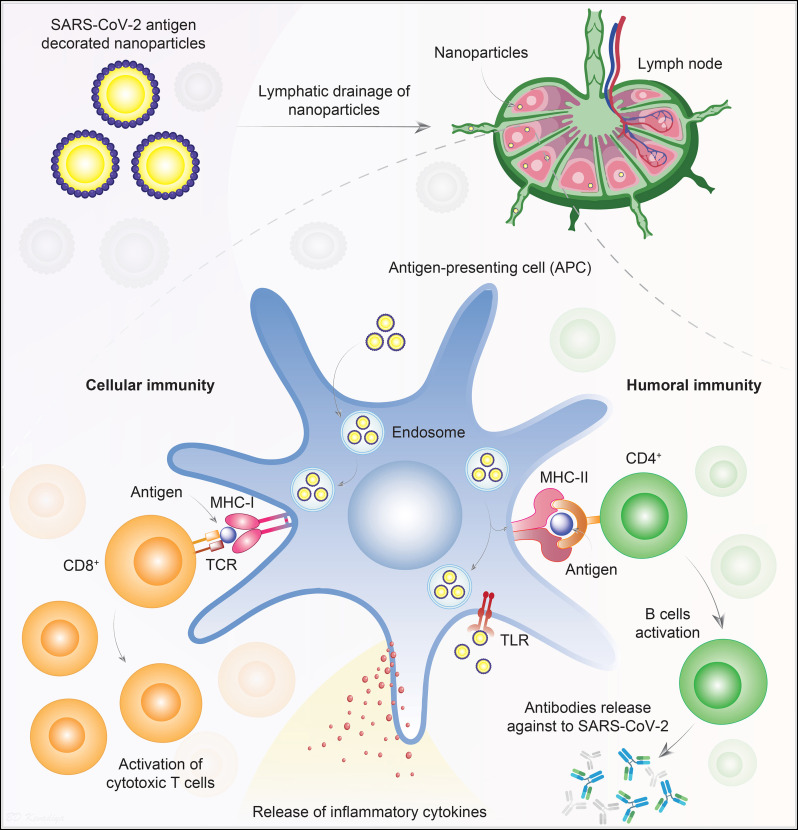

Fig. 4.

Targeted delivery of SARS-CoV-2 antigens. Nanoparticles are decorated on the surface to present SARS-CoV-2 antigens to efficiently enter APCs. Lymphatic drainage of the nanoparticles brings them in close proximity to the immune cells, particularly the APCs. Nanoparticles stimulate the APCs in different ways. APCs engulf the nanoparticles into endosomes and then presents the NP's surface engineered antigen to CD8 T lymphocytes via membrane-bound MHC-I and TCR interactions. Also, nanoparticles are ligands for the TLRs, which activates the APCs and induce secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Following the interaction between MHC-I and TCR, in the presence of co-stimulatory molecules and cytokines, the activated CD8 T cells kill the infected cells by inducing cytotoxicity. Nanoparticles surface engineered antigens can also be presented to helper CD4 T cells via MHC-II. Subsequently, CD4 T cells activate the B cells to produce protective antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 antigen. Abbreviations; Antigen presenting cells, APCs; class I major histocompatibility complex, MHC-I; class II major histocompatibility complex, MHC-II; T-cell receptor,TCR; Toll-like receptor, TLR.

7.1. mRNA nanovaccine

The mRNA-based nanovaccines have benefits over other technologies which include short development time, simple manufacturing and purification processes regardless of the antigen, and most importantly, mimic natural infection to promote potent cellular and humoral immunity by eliciting CD4 and CD8 T cell responses (Fig. 2) [285,286]. Multiple mRNAs can be combined into a single vaccine to deliver mRNA transcripts of interest into the host cell cytosol, which allows the encoding of one or more antigen(s). Such favourable properties designate mRNA vaccine as a forefront runner for the development against COVID-19 [21]. To note, no commercial vaccine is available till date developed with this technology which mandate strict regulatory requirements to undergo the candidate before approval for the general public.

Mainly two types of mRNA constructs have been evaluated: self-amplifying mRNA and non-replicating mRNA [286]. Both types of mRNAs are synthetically produced, encoding target antigens' 5′ and 3′ untranslated region, cap structure, and open-reading frame, through the use of a cell-free enzymatic transcription reaction. Self-amplifying mRNA vaccines possess genetically-engineered replication machinery that is obtained from the positive-stranded mRNA viruses [286]. Delivery of the intact mRNA vaccine from the injection site to the target cell cytosol for the initiation of protein translation is as important as manufacturing of the mRNA construct. mRNA is labile and prone to degradation primarily from nuclease activity within the cells; hence, efficient protection of the mRNA is critical during administration [285]. Lipid nanoparticles could serve as safe and compatible intracellular delivery platform for the development of successful mRNA vaccine. Lipid nanoparticles offer (i) sustained mRNA confirmation (iii) protection of mRNA cargos against nuclease degradation and; (ii) efficient cellular uptake for targeted mRNA delivery [17,276]. In the past, lipid nanocarrier system has delivered RNA for the therapeutic applications. In 2018, the first lipid nanoparticle formulated siRNA product Onpattro® was approved by the US FDA for the treatment of polyneuropathy caused by hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, which established the standard for the clinical safety of lipid nanoparticle-based siRNA formulations [287]. Lipid nanoparticles are generally composed of ionizable lipids, cholesterol, PEGylated lipids, and phospholipids to deliver an mRNA construct. The ionizable cationic lipids create a lipid bilayer shell that allow mRNA encapsulation within an aqueous core for endosomal escape [288]. New-generation cationic lipids and lipoids are developed that maintain neutral or mild cationic charge at physiological pH to reduce nonspecific lipid-protein interactions [289]. Cholesterol provides stability to the lipid bilayer membrane and facilitates cellular transfection. PEGylated lipids serve to sterically stabilize the nanoparticles and reduce nonspecific protein bindings. Decoration of the outer surface with targerting moieties and encapsulation of multiple antigens for tailor-made immunization are additional advantages with lipid nanoparticles [290]. Several companies have used nanovaccine technology for the development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Moderna, an mRNA-based biotechnology company, initiated the first mRNA nanovaccine using their patented nanovaccine technology (WO2017070626 and WO2018115527). Moderna first developed an mRNA vaccines that encodes the MERS-CoV antigens: (i) S or its fragment (S1); (ii) E, (iii) membrane (M); or (iii) nucleocapsid (N) protein. These vaccines are effective in inducing antigen-specific immune responses. Moderna encapsulated the mRNA mixture into the cationic lipid nanoparticles and intradermally injected the vaccine into mice, which lead to the encoding MERS-CoV S proteins' translation in vivo for the subsequent induction of humoral immune responses. The MERS-CoV mRNA nanovaccine encoding the full-length S protein reduced more than 90% of the viral load in the lungs and induced a significant amount of neutralizing antibody against MERS-CoV in the New Zealand white rabbits [291]. Research on MERS-CoV vaccines led to funding from CEPI (Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) to manufacture an mRNA nanovaccine against SARS-CoV-2 (mRNA-1273). This led to the first mRNA nanovaccine to enter clinical trial (NCT04283461) for SARS-CoV-2. In mRNA-1273 vaccine, two proline amino acids were substituted at 986 and 987 positions in the S2 cleavage site to maintain stability of the prefused S mRNA [291]. The findings from the Moderna SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trial raised optimism. In the preliminary Phase 1 clinical trial, Moderna investigated a dose-escalation study of mRNA-1273 in 45 healthy adults (18 to 55 years of age), who were vaccinated at two time points, 28 days apart, with three different doses (25 μg, 100 μg or 250 μg). Commensurately, antibody responses were highest with the higher dose after the first vaccination and titers were increased after the second vaccination. Serum-neutralizing activity was detected using pseudotyped lentivirus reporter single-round-of-infection neutralization assay (PsVNA) and live wild-type SARS-CoV-2 plaque-reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) assay. No participant had measurable neutralizing antibody responses before vaccination however all participants showed higher antibody responses after second vaccination in both PsVNA and PRNT assays. mRNA-1273 stimulated Th1-biased CD4 T cell responses in all participants. From the lower dose groups (50 μg and 100 μg), all the participants showed mild or moderate side effects. However, one or more adverse events were reported in few participants from the 250 μg dose group. Similar adverse events were presented in clinical trials with high dose of avian influenza mRNA vaccine (influenza A/H10N8 and influenza A/H7N9) manufactured by Moderna's lipid nanoparticle technology [292]. The Phase 1 clinical trial was expanded to included 40 older adults of 56 to 70 years or ≥ 71 years of age who received two doses of mRNA-1273 vaccine (50 μg and 100 μg). In this study, 100 μg dose induced higher antigen-binding and neutralizing antibodies in all the older participants while the associated side effects were mainly mild or moderate [293]. In Phase 2 clinical trial, Moderna is demonstrating safety and immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 in 600 healthy participants across all age groups (above 18 years) where participants will receive either 50 μg or 100 μg dose twice at 28 days interval with follow-up for 12 months after the second vaccination (NCT04405076). Moderna has already initiated a Phase 3 clinical trial in collaboration with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in 30,000 young adult participants to test mRNA-1273 at 100 μg dosage. The primary endpoint of this study is prevention of symptomatic COVID-19 disease while the secondary endpoints include prevention of severe COVID-19 disease and infection by SARS-CoV-2 (NCT04470427) [292]. On November 15, 2020, the interim results of mRNA-1273 Phase 3 clinical trial were released that comprised 95 cases of symptomatic COVID-19 where 90 cases belongs to the placebo group and 5 cases from the vaccinated group. The vaccine was found safe and well-tolerated and showed 94.5% efficacy in studied candidates with statistical significance [294]. Based upon the promising interim results of Phase 3 trial, Moderna received the US FDA EUA of mRNA-1273 for COVID-19 treatment [295].

BioNTech and Pfizer have jointly developed BNT162(b1,b2,b3) vaccines for COVID-19 (NCT04368728). BNT162b1 is a nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine that encodes trimerized SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) which is a key target for viral neutralizing antibodies. BNT162b2 is mRNA vaccine that encodes a membrane-anchored SARS-CoV-2 full-length S protein stabilized in the prefusion confirmation. Nucleotide modifications in the RBD and S pretein sequences increase RNA stability from enzymatic degradation and protect RNA confirmations in the native form to improve immunogenicity. Both vaccines are encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles for more efficient mRNA delivery into the target cells after intramuscular injection. The Phase 1/2 clinical trial results of BNT162b1 were available in August 2020 from 45 healthy adults of 18–55 years of age. Dose ascalation study was performed using 10 μg, 30 μg or 100 μg of BNT162b1. 10 μg and 30 μg doses were given twice at 21 days interval while 100 μg dose was given once due to increased risk of reactogenicity. Dose dependant RBD-binding IgG levels and SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing titers in the sera were detected at 21 days after the first dose that substantially increased after the second dose suggested robust immunogenicity in all participants. Geometric mean neutralizing titer levels were 1.8 to 2.8 fold higher than of COVID-19 convalescent human sera [296,297]. The extended results of the BNT162b1 Phase 1/2 clinical trial showed higer titers of broadly neutralizing antibodies in all participants with concurrent induction of RBD-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells. Surprisingly, all the participants showed Th1 biased SARS-CoV-2 immune responses after BNT162b1 immunization [298]. In a separate Phase 1 clinical trial, BNT162b2 was assessed with BNT162b1 in 195 healthy young (18 to 55 years of age) and older adults (65 to 85 years of age) at four dose levels (10 μg, 20 μg, 30 μg, and 100 μg), each injected twice 21 days apart except the highest dose. Both, BNT162b1 and BNT162b2 elicited identical dose dependant SARS-CoV-2 nutralizing antibody titers higher than the COVID-19 convalescent serum. However, BNT162b2 was associated with lower incidences and severity of adverse reactions in both young and older adults compared to the BNT162b1. Therefore, BNT162b2 was selected for the advancement in the Phase 2/3 clinical safety and efficacy assessment trials [280]. Recently, BioNTech and Pfizer concluded the Phase 3 clinical trial results with BNT162b2. The study enrolled more than 43,000 young and older adult participants in approximately 150 clinical sites across different corners of the world. The results indicated 95% efficacy of the BNT162b2 vaccine in the study participant with or without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection including adults over 65 years of age without any serious adverse reactions [299]. After the positive Phase 3 clinical trial conclusion, BNT162b2 vaccine recently received emergency approval from UK's healthcare regulator the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for the treatment of COVID-19 [300]. BNT162b2 has also been approved for marketing in the Bahrain, Canada and USA for the COVID-19 treatment [14,301].

Acuitas Therapeutics (Vancouver) and Imperial College (London) developed a self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) lipid nanoparticles encapsulated with the pre-fusion stabilized SARS-CoV-2 S protein. They characterized both the humoral and cellular immune response, as well as the neutralization capacity of a pseudo-typed SARS-CoV-2. The mice were immunized with two injections, one month apart, at doses ranging from 0.01 μg to 10 μg. After 6 weeks, robust SARS-CoV-2 S protein specific IgG antibodies were seen in animals in a dose-dependent manner. Even at the lowest dose, saRNA nanovaccine induced higher neutralizing antibody teters in mice compared to the recovered COVID-19 patients or from other reported subunit vaccines for the MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2. Higher viral neutralization, cellular responses, and antibody titers were demonstrated with saRNA nanovaccine in comparision to the electroporated plasmid DNA, the positive control, suggesting success of lipid nanoformulation for saRNA delivery [302].

Vaccines must be stored in a narrow temperature range to maintain their stability and efficacy. Cold shipment chain for the vaccine, consumes almost 80% of the total vaccine development cost which limit vaccine access in the countries with low and emerging economies [303]. To overcone these challenges, a thermostable mRNA nanovaccine was developed by the Suzhou Abogen Biosciences in collaboration with Walvax Biotechnology and People's Liberation Army Academy of Military Sciences in China for COVID-19. The vaccine candidate ARCoV was developed by encapsulating an mRNA encoding the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein in the lipid nanoparticles using a preformed vesicle method [304,305]. After intramuscular injection in mice, ARCoV (30 μg) readily biodistributed in the upper abdomen 6 h post injection. At the injection site, expression of target SARS-CoV-2 RBD was colocalized with CD11b-positive monocytes, CD163-positive macrophages, and CD103-positive dendritic cells with no local inflammation, suggesting vaccine ability to recruit key APCs. ARCoV induced robust SARS-CoV-2 RBD specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies and antigen-specific T cell responses which were further elevated by ARCoV booster administration. Similar protective immune responses were also observed in non-human primates (cynomolgus monkeys) after ARCoV immunization [306,307]. ARCoV was found stable at different temperatures including 4 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C upto a week confirming its thermostability [308].

An alphavirus-derived replicating RNA vaccine encoding the SARS-CoV-2 S protein, repRNA-CoV2S, was developed using lipid inorganic nanoparticles to enhance vaccine stability, immunogenicity, and targeted delivery. After a single or multiple intramuscular injections, repRNA-CoV2S induced robust SARS-CoV-2 S protein IgG antibodies and antigen-specific T cell responses in rodents and monkeys. Additionally, the neutralizing antibody responses were comparable to the COVID-19 convalescent plasma. The repRNA-CoV2S also induced robust immune responses in aged mice suggesting its potential for the elderly population. repRNA-CoV2S should be further evaluated in clinical studies to confirm its immunogenicity in humans [309].

7.2. Protein and subunit nanovaccine

Novavax Inc. is developing multiple nanoparticle vaccines for the COVID-19 treatment [310]. A promising candidate, recombinant SARS-CoV-2 full length S protein nanoparticle vaccine NVX-CoV2373 was generated by incorporating mutations at the S1 and S2 cleavage site to protect from proteolytic degradation and at the heptad repeat 1 site to maintain pre-fusion confugarations. NVX-CoV2373 was evaluated in Phase 1/2 clinical trials at two different dosages (5 μg and 25 μg) in 131 healthy participants, for each dose two intramuscular injections were administered 21 days apart. NVX-CoV2373 was found to be safe and elicited strong immune responses, with SARS-CoV-2 S protein specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies that exceeded the levels of COVID-19 convalescent serum. The immunogenicity was improved by the sponin-based Matrix-M1 adjuvant, which induced Th1 biased immune responses [272]. A Phase 3 clinical trial of NVX-CoV2373 in combination with influenza nanoparticles vaccine NanoFlu™, initiated in the UK after enrolling 10,000 elderly participants from 18 to 84 years of age. The study has now extended to include 30,000 participants from different parts of the world to reach better conclusions [311]. Novavax Inc. is collaborating with Takeda Pharmaceutical to establish the infrastructure and scale-up manufacturing with the aim of developing 250 million doses of the NVX-CoV2373 vaccine to fulfill global demand [312].

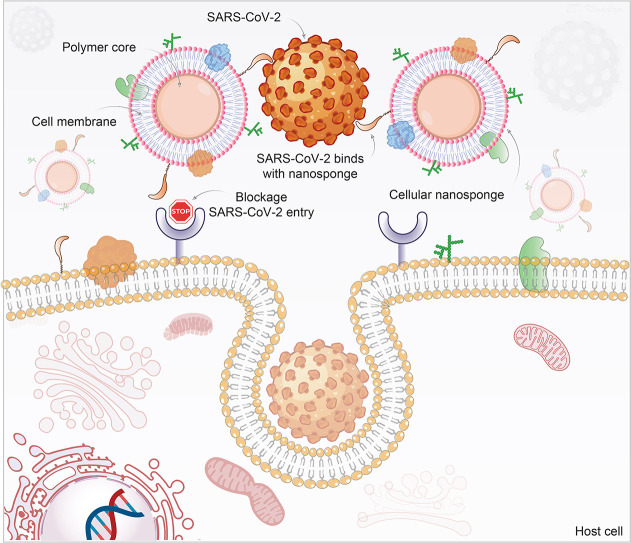

During the past months, researchers have realized challenges in the development of therapeutics and preventive measures against SARS-CoV-2 mutations [313]. To overcome virus mutations associated complications, a novel cellular nanosponge concept was introduced as an active cellular entry-level neutralizing agent against SARS-CoV-2 [314]. In this technology, nanoparticle cores were synthesized (<100 nm size) using biodegradable polymer, poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), followed by their coating with the plasma membrane derived from either human lung epithelial type II cells or human macrophages. Developed nanosponges (~100 nm size) display the same protein RBD required by SARS-CoV-2 for cellular entry. Both epithelial-nanosponge and macrophage-nanosponge showed SARS-CoV-2 neutralization and protected Vero E6 cells against infection in a concentration-dependent manner. As long as the SARS-CoV-2 target remains the identified host cell, the nanosponge can neutralize the infection, thereby such platform offers (i) broad-acting countermeasures against SARS-CoV-2 mutations and (ii) protection against other emerging coronavirus species (Fig. 5 ). Both nanosponges were found safe upon intratracheal administration (300 μg) which is very important to treat respiratory diseases including COVID-19. Overall, the nanosponge platform offers significant benefits over other therapies to fight against the rapidly mutating SARS-CoV-2 [314].

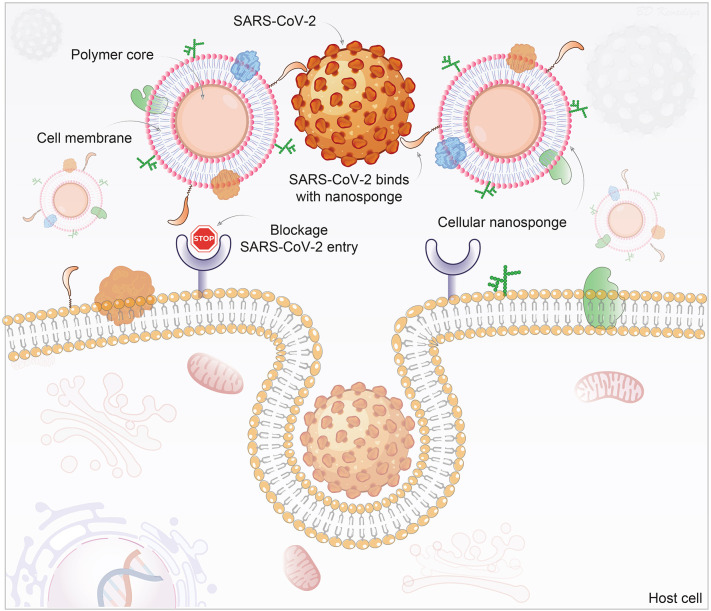

Fig. 5.

Schematic of nanoparticles used as a decoy to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Polymeric nanoparticle cores are wrapped with cell membranes derived from SARS-CoV-2 target cells, human lung epithelial type II cells, or macrophages. The inheritance of the surface antigenic profiles of the target cells allows the nanosponges to act as decoys to the circulating viruses and be independent of the status of mutation and strain. They serve to prevent virus entry to the host's natural target cells. The illustration is prepared in-house and schematic ideas and technical details were followed as presented in previously published report [314].

A recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S1 subunit nanovaccine with two different adjuvants, amphiphilic adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) and CpG oligiodeoxynucleotides (ODN) is developed. In mice, it induced robust humoral immune responses and strong CD4 and CD8 T cell activation compared to the free S1 subunit vaccine with traditional alum adjuvant.

Further studies are required to assess safety and clinical translatability of this nanovaccine for the COVID-19 treatment [315]. University of Washington School of Medicine researchers are developing a novel nanovaccine platfrom where viral antigen(s) is fused on the surface of self-assembling de novo designed nanoparticles that allow unprecedented molecular configuration control of the resulting vaccine [316]. Researchers tailored self-assembling nanoparticles by presenting the ectodomains of influenza, HIV, and RSV viral glycoprotein trimers with the aim to induce better protective immune responses compared to direct antigen delivery [316]. Administration of HIV Env trimer-expressing nanoparticles in rhesus macaques showed accumulation of nanoparticles in the B cell follicles of the draining lymph nodes within two days after immunization, leading to enhanced protective immune responses [317]. As SARS-CoV-2 also exhibits trimeric S protein-like influenza, HIV, and RSV, researchers are developing a nanovaccine against COVID-19 using this technology [316].

8. Virus like particles (VLPs)