Abstract

Objective:

To analyze the association between early audiometric age-related hearing loss (HL) and brain beta-amyloid, the pathologic hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

Methods:

Cross-sectional analysis of 98 participants in a cohort study of hearing and brain biomarkers of AD. The primary outcome was whole brain beta-amyloid standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) on positron emission tomography. The exposure was hearing, as measured by either pure tone average or word recognition score in the better ear. Covariates included age, gender, education, cardiovascular disease, and hearing aid use. Linear regression was performed to analyze the association between beta-amyloid and hearing, adjusting for potentially confounding covariates.

Results:

Mean age was 64.6 ± 3.5 (SD) years. In multivariable regression, adjusting for demographics, education, cardiovascular disease, and hearing aid use, whole brain beta-amyloid SUVR increased by 0.029 (95% CI = 0.003, 0.056) for every 10 dB increase in pure tone average (P=0.030). Similarly, whole brain beta-amyloid SUVR increased by 0.061 (0.009, 0.112) for every 10% increase in word recognition score (P=0.012).

Conclusion:

Worsening hearing was associated with higher beta-amyloid-burden, a pathologic hallmark of AD, measured in vivo with PET scans.

Keywords: age-related hearing loss, presbycusis, beta-amyloid, cognition, dementia

INTRODUCTION

Age-related hearing loss (HL) is a highly prevalent and undertreated condition. It is one of the most common disabilities affecting the elderly population, with almost two-thirds of those over the age of 70 years exhibiting HL.1 HL has received growing attention across medicine, public health, and politics due to its relationship with cognitive impairment and dementia.2–6 A recent prominent review calculated HL as the single greatest potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia, greater than education, smoking, and physical inactivity.7

Dementia is one of the biggest public health concerns, with over $221 billion in annual costs in the United States8 and no disease-modifying treatments. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia.

While there is no definitive evidence casually linking HL to dementia, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies adjusting for potential confounders have raised this possibility. Several studies have also linked HL specifically to AD.9,10 One theoretical model has suggested that HL may lead to dementia through measurable changes in brain structure.11,12 Several prior studies have illustrated that those with HL have decreased regional and whole brain volumes on MRI.13–15 Data linking HL to more specific brain biomarkers of dementia are largely lacking. The few studies that have been published are mostly null.16–18 To our knowledge, no study has shown an association between HL and brain beta-amyloid, the characteristic pathologic feature of AD.

Amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) has made it possible to non-invasively measure the accumulation of brain beta-amyloid plaques. Herein, we introduce a new cohort study designed to study potential mechanistic associations between HL and dementia using brain imaging biomarkers of dementia. We analyze the association between audiometric HL and the characteristic beta-amyloid plaque of AD. These data will help clarify the nature of how HL might be related to dementia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Cohort

The Northern Manhattan Study of Metabolism and Mind (NOMEM) is a community-based prospective study based out of Columbia University Irving Medical Center.19 The sampling frame includes northern Manhattan and surrounding regions of The Bronx in New York City. The original goal of NOMEM is to study the relation of diabetes and pre-diabetes with mental health outcomes, including cognition, in late-middle aged individuals. Enrollment, however, does not depend on diabetes status; thus, the prevalence of diabetes reflects that of the population at large. Inclusion criteria of the main NOMEM study include age between 55 and 69 years as well as the ability to undergo phlebotomy, neuropsychological assessments, MRI, and PET scans. All testing is conducted in English or Spanish, per subject preference.

A hearing sub-study was started in 2017 (NOMEM-Hearing) to examine the association between audiometric HL and both dementia and cognition. NOMEM-Hearing is longitudinal and ongoing. The additional inclusion criterion of the NOMEM-Hearing sub-study includes lack of open wounds on or near the auricle. We present the cross-sectional data of the first 98 participants.

Hearing (Exposure)

A brief hearing questionnaire inquired about history of ear disease, ear surgery, perceived HL, or wearing of hearing devices. If hearing devices were worn, the device type (hearing aid, cochlear implant, or other) and frequency (hours/week) was asked.

Hearing was assessed with a clinically-validated20, American National Standards Institute-conforming iPad-based portable audiometer (ShoeBox, Clearwater Clinical, Ontario, Canada). Subjects were brought to a quiet room with ambient noise <45 dB as measured by continuous decibel meter monitoring. Calibrated sound-attenuating professional headphones were placed. Hearing devices were removed. Air conduction pure tone thresholds were measured. The pure tone average (PTA) was calculated by the mean hearing threshold (in dB hearing level) at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz.

Word recognition was measured as the percent of correctly repeated English or Spanish words presented at suprathreshold loudness (+35 dB for PTA <50 dB, +30 dB for PTA 50–59 dB, +20 dB for PTA 60–69 dB, +10 dB for PTA ≥70 dB). The test was performed without any background noise. Unlike cognitive tests that involve recalling words, the word recognition test used in audiometry only requires instant repeating of words and does not rely on memory.

The primary exposure (independent) variable was pure tone average in the better hearing ear (in dB hearing level). The secondary exposure (independent) variable was word recognition score (in % correct) in the better hearing ear.

Beta-Amyloid (Outcome)

Beta-amyloid deposition is a characteristic feature of AD. It is thought to lead to synaptic dysfunction and dementia.21,22 Global brain beta-amyloid was ascertained with 18F-florbetaben positron emission tomography/com puted tomography (PET/CT) scans (Siemens Biograph 64). Images were acquired over 20 minutes beginning 90 minutes post-injection. The static PET image was registered with the CT scan.

The standardized uptake value (SUV) was defined as the decay-corrected brain radioactivity concentration normalized for injected dose and body weight. The SUV ratio (SUVR) is the SUV at each voxel normalized to the SUV of the cerebellar gray matter. The primary outcome (dependent variable) was brain beta-amyloid burden ascertained as global standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) measured with 18F-Florbetaben PET. Overall mean beta-amyloid burden was calculated from voxel-based, individual region of interests (ROI), including lateral temporal cortex, parietal cortex, cingulate cortex, and frontal cortex.

Beta-amyloid SUVR was primarily analyzed continuously. In a sensitivity analysis, beta-amyloid was binarized into high and low levels, based on the median SUVR.

Covariates

Covariates included additional independent variables that could confound the relationship between the exposure and the outcome. This included age (years), gender (woman, man), education (years), cardiovascular disease, hearing aid use (yes/no), and ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic).

Cardiovascular disease was calculated as a composite score, from 0 to 4, where 1 point was added for each of the following conditions that were present: hypertensions (blood pressure >140/90), diabetes (self-reported), stroke (self-reported), heart attack (self-reported). This composite score was created to avoid multicollinearity in regression modeling.23 If only 1 of the 4 individual cardiovascular variables were missing, the missing value was imputed by taking the mean of the other 3 scores.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable linear regression (multiple linear regression) was used to examine the association between HL and continuous beta-amyloid SUVR, controlling for covariates. The unit of change for pure tone average was a 10 dB worsening (increase) in pure tone average, which is approximately equal to a half-category worsening (where categories are normal, mild, moderate, moderately-severe, and profound). The unit of change for word recognition score was a 10 percentage point worsening (decrease) in word recognition score. Standardized residuals were plotted against leverage to identify influential outliers.

In a sensitivity analysis, multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association between HL and binary beta-amyloid SUVR. Unless otherwise indicated, means are presented ± standard deviation (SD). Significance was defined at the p=0.05 level. Data analysis was performed in the R programming language v3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with RStudio 1.2 (RStudio, Inc, Boston, MA).

Regulatory

Institutional Review Board approval at Columbia University Irving Medical enter was attained for this study (#AAAQ2950, AAAI5156, AAAR5012)

RESULTS

Enrollment and Inclusion

There were 460 subjects in the Northern Manhattan Study of Metabolism and Mind (NOMEM). Of those, 118 had a hearing test as part of enrollment into the NOMEM-Hearing sub-study. Of those, 98 subjects had amyloid PET collected, comprising the analytic sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram indicating subject inclusion and exclusion.

Two subjects were missing 1 of the 4 individual cardiovascular variables. The missing value was imputed as detailed in the methods.

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline subject characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 64.3 years (±3.5 SD) with a range of 51 to 72 years. The cohort was 65% women. Seventy-five (77%) subjects had normal hearing (≤25 dB pure tone average) and 23 (23%) of subjects had HL (>25 dB), an expected proportion given the community-based sample.1 Hearing aid use was 2% overall. No subjects had cochlear implants or other implanted hearing devices. The mean pure tone average in the better hearing ear was 20.4 dB (±8.9) with a range of 5 to 54 dB. The mean word recognition score in the better hearing ear was 98% (±5.1) with a range of 60 to 100%. (Supplemental Table S1) The median amyloid level was 1.14 (± 0.11).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Overall | Normal Hearing (≤25 dB) | Hearing Loss (>25 dB) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | 98 | 75 (77%) | 23 (23%) | N/A |

| Pure tone average, Mean ± SD | 20.4 ± .8.8 | 16.5 ± 4.8 | 33.0 ± 6.8 | <0.01 |

| Word recognition score, Mean ± SD | 98.3 ± 5.1 | 99.1 ± 2.2 | 95.4 ± 9.3 | 0.07 |

| Age, Mean ± SD | 64.3 ± 3.5 | 64.1 ± 3.6 | 65.0 ± 3.2 | 0.22 |

| Women, No. (%) | 64 (65%) | 56 (75%) | 8 (35%) | <0.01 |

| Hispanic Ethnicity, No (%) | 76 (78%) | 57 (76%) | 19 (83%) | 0.70 |

| Hearing Aid Use, No. (%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0.05 |

| Education, Years, Mean ± SD | 12.1 ± 3.3 | 12.4 ± 3.1 | 11.1 ± 3.8 | 0.15 |

| Global Amyloid SUVR, Mean ± SD | 1.16 ± 0.11 | 1.15 ± 0.11 | 1.17 ± 0.09 | 0.52 |

Fisher’s exact or chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables; t-tests were used for continuous variables.

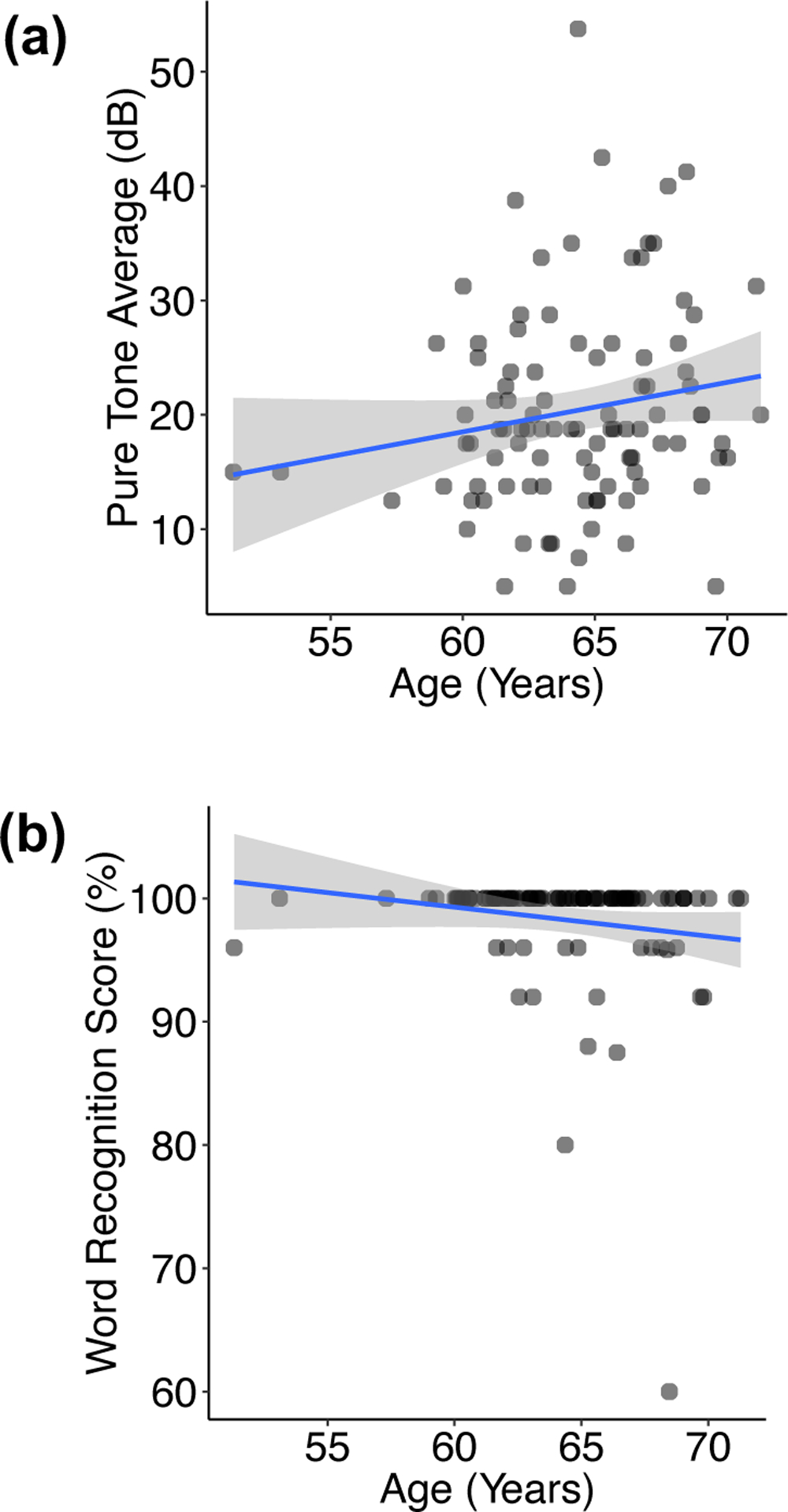

The distribution and relationship of the hearing and age variables appear in Figure 2. Because the study cohort is of late-middle age adults, there is a relatively narrow age range and corresponding narrow distribution of HL severity.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots depicting the distribution and relationship of hearing versus age. Points represent individual subjects, with overlapping points indicated by darker coloration. A univariable regression line (blue) and 95% confidence interval (gray shading) are overlaid. (a) Pure tone average in the better hearing ear versus age. (b) Word recognition score in the better hearing ear versus age.

Regression Analyses

There was a near-significant relationship between hearing measured by pure tone average and global amyloid SUVR in univariable regression (P=0.054). (Figure 3a and Table 2) Once covariates were controlled for in multivariable regression, the relationship became significant. For every 10 dB worsening (increase) in pure tone average, the global amyloid SUVR increased by 0.028 (95% CI = 0.002, 0.053), on average, adjusting for age and gender. When education and cardiovascular disease were additionally added to the model, the relationship was strengthened. When hearing aid use was additionally added to the model, the relationship was slightly attenuated. In the fully adjusted model, controlling for age, gender, education, cardiovascular disease, and hearing aid use, every 10 dB worsening in pure tone average was associated with an increase in the global amyloid SUVR of 0.029 (0.003, 0.056; P=0.030), on average. (Table 2)

Figure 3.

Univariable linear regression models of global brain beta-amyloid standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) based on hearing. The univariable regression line (blue) and 95% confidence interval (gray shading) are overlaid. (a) Global brain beta-amyloid versus pure tone average in the better ear. (b) Global brain beta-amyloid versus wore recognition score in the better rear.

Table 2.

Regression Models for Global Amyloid Standardized Uptake Value Ratio (SUVR) Based on Pure Tone Average Hearing

| Model | Global Amyloid SUVR Difference per 10 dB Worsening in Pure Tone Average (95% CI)2 | P |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Univariable (pure tone average1) | 0.024 (0.00, 0.049) | 0.054 |

| 2. Multivariable (model 1 + age, gender) | 0.028 (0.002, 0.053) | 0.032* |

| 3. Multivariable (model 2 + education, cardiovascular disease) | 0.032 (0.006 0.058) | 0.015* |

| 4. Multivariable (model 3 + hearing aid use) [Fully adjusted model] | 0.029 (0.003 0.056) | 0.030* |

Pure tone average indicates hearing in the better ear

Positive coefficients indicate greater amyloid burden with greater pure tone average (worse hearing)

significant, p<0.05

There was a significant relationship between hearing measured by word recognition score and global amyloid SUVR in univariable regression. For every 10% worsening (decrease) in word recognition score, the global amyloid SUVR increased by 0.059 (0.017, 0.101; P=0.006), on average. (Figure 3b and Table 3) This relationship was maintained as covariates were added in multivariable regression. In the fully adjusted model, controlling for age, gender, education, cardiovascular disease, and hearing aid use, every 10% worsening in word recognition score was associated with an increase in the global amyloid SUVR of 0.061 (0.009, 0.112; P=0.021), on average. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Regression Models for Global Amyloid Standardized Uptake Value Ratio (SUVR) Based on Word Recognition Score Hearing

| Model | Global Amyloid SUVR Difference per 10% Worsening in Word Recognition Score (95% CI)2 | P |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Univariable (word recognition score1) | 0.059 (0.017, 0.101) | 0.006* |

| 2. Multivariable (model 1 + age, gender) | 0.062 (0.019, 0.104) | 0.005* |

| 3. Multivariable (model 2 + education, cardiovascular disease) | 0.063 (0.018, 0.105) | 0.006* |

| 4. Multivariable (model 3 + hearing aid use) [Fully adjusted model] | 0.061 (0.009, 0.112) | 0.021* |

Word recognition score indicates hearing in the better ear

Positive coefficients indicate greater amyloid burden with lower word recognition score (worse hearing). The direction of the word recognition is reversed compared to Figure 3.

significant, p<0.05

Assumptions of linear regression were assessed and met. In a sensitivity analysis, ethnicity was added to the above fully adjusted models. There was no meaningful difference in the associations (≤0.001 change in coefficients). In an additional sensitivity analysis, regressions were run examining beta-amyloid binary categories (high or low, depending on a median value of 1.14 ± 0.11) as an outcome on the fully adjusted models. For every 10 dB increase in pure tone average, the odds of high beta-amyloid SUVR levels increased 2.11 times (1.18, 4.15), on average. There was no significant association between word recognition score and binary amyloid SUVR (P=0.066). Finally, no influential outliers were identified on regression diagnostics.

In supplemental analyses by region of interest, there were significant associations between hearing, whether by pure tone average or word recognition score, and amyloid SUVR in most brain regions. This included the right temporal lobe, both parietal lobes, both frontal lobes, and both cingulate cortices. (Supplemental Table S2) For example, every 10 dB worsening in pure tone average was associated with an increase in right temporal lobe amyloid SUVR of 0.027 (0.005, 0.050), on average, adjusting for confounders. Interestingly, there was no association between hearing and left temporal lobe amyloid SUVR.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study of nearly 100 individuals, audiometric HL was independently associated with brain beta-amyloid measured on PET scan. The association was robust to the adjustment of multiple confounders, including demographics, education, cardiovascular disease, and hearing aid use. The association was robust to whether hearing was defined by the pure tone average or word recognition score. Because beta-amyloid is the hallmark pathologic feature of AD, these results raise questions about how HL may be mechanistically related to dementia. To our knowledge, this is the first report to find an association between HL and brain beta-amyloid. It is also one of the largest studies to examine the association between audiometric HL and a brain biomarker of cognition.

Multiple prior studies have shown an association between HL and both dementia7,9–11,24–26 and impaired cognition26–30, raising the important question of the mechanistic explanation. Hearing may be related to dementia through a causal pathway, confounding, or a reverse causal pathway. Three mechanistic pathways have been proposed for a causal pathway, which may not be mutually exclusive.11,12 First, hearing may lead to social isolation, which in turn, may lead to chronically reduced cognitively stimulating input, and subsequent cognitive decline and dementia. Second, hearing may increase cognitive load such that efforts normally used to create working memories are instead diverted to decoding speech. This could reduce the threshold for clinical dementia. Third, hearing may induce measurable changes in brain structure through its efferent connections.

The main neuropathologic constructs examined with in vivo brain imaging studies of AD are amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration. Previous studies analyzing volumetric brain MRI data as a measure of neurodegeneration have supported the hypothesis that hearing is associated with alterations in brain anatomic structure. Individuals with audiometric HL have accelerated volume declines in the whole brain as well as the temporal lobe, which contains the auditory cortex.13–15 Similar cross-sectional associations have also been found.31,32 Several of these prior studies have shown an association between hearing and right, but not left, temporal lobe volume.13,32 Likewise, we found an association between hearing and right, but not left, temporal lobe amyloid levels. Language is predominantly processed in the left temporal lobe, which makes these findings initially seem counterintuitive. In fact, we found associations between every analyzed region of the brain except the left temporal lobe. It is theoretically possible that greater processing requirements in the face of a degraded peripheral auditory signal may actually maintain function in the left temporal lobe at the expense of other regions of the brain. This agrees with the “cognitive load” theory, whereby those with HL divert cognitive resources to decoding words at the expense of working memory and other cognitive functions.

A recent study found an association between age-related HL and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tau, another marker seen in AD. However, no association between HL and either beta-amyloid in CSF on brain amyloid PET were seen.18 Another recent paper did not find an association between HL and neuropathologic findings of AD on brain autopsies; however, the lack of an objective hearing measure may have limited sensitivity.17 A study similar to ours that used a different radioisotope (18F-florbetapir) in an older population did not find an association been audiometric HL and beta-amyloid on PET.16 The reason for the differing findings from our study are unclear. Our results deserve replication in future cohorts and until then should be considered preliminary.

The relation of hearing to dementia could be explained by confounding. In other words, a third factor could cause both HL and dementia, in which case there is no causal relationship (in either direction) between hearing and dementia. To eliminate this possibility, a randomized controlled trial (of reducing dementia by treating HL) would need to be performed. This study controlled for a variety of potential confounders, which could cause (or prevent) both HL and dementia. This included demographic factors, education level, cardiovascular disease, or hearing aid use. However, other confounders, either unmeasured or as-yet unknown, could still account for the relationship between hearing and dementia.

Finally, dementia could cause HL. However, neuropathologic findings of AD have not been found in the peripheral auditory pathway before.33,34 In addition, longitudinal studies associating HL and dementia have shown that the HL temporally preceded dementia.9,10,24

In a sensitivity analysis, a binary variable of amyloid was utilized. A relationship between pure tone average and odds of high amyloid was found. While nearly-significant, there was no relationship between word recognitions score and odds of high amyloid. The latter could be related to the loss of data resolution with a binary outcome in a relatively small cohort size of 98 individuals. With a larger cohort, we anticipate a relationship would be seen.

This study has limitations. While the NOMEM-Hearing study is longitudinal, only one wave of data was available. Thus, a baseline cross-sectional analysis was performed. Causal inference is thus not possible. Because the population drew largely from Northern Manhattan and included primarily Hispanics, results may not be generalizable to the larger population. Results should be replicated in other cohorts.

While the majority of subjects had normal hearing, reflecting the community-based middle age sample, associations between both hearing and cognition27 as well as hearing and brain volumes14 have been found previously in this age group. This argues against the need to oversample subjects with HL. The lack of subjects with moderately-severe to profound HL makes it difficult to generalize our findings to this group. Future studies should also include subjects with marked HL

This study has strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has found an association between HL and the characteristic beta-amyloid pathology of AD. We analyzed results with continuous and binary outcomes and also used two different hearing measures. We also studied primarily Hispanics, an ethnic group that is historically neglected in research despite growing in population in the US.35 Finally, our subjects were from the community and thus results may be less biased than a convenience-based sample at a tertiary care otologic practice.

CONCLUSION

Early audiometric HL was independently associated with the presence of brain beta-amyloid, the hallmark of Alzheimer’s pathology. Future longitudinal and randomized controlled studies should examine whether HL is causally related to AD and related dementias.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table S1. Scattergram of Hearing Levels

Supplemental Table S2. Regression Models for Regional Amyloid Standardized Uptake Value Ratio (SUVR) Based on Hearing

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Jessica Campbell for performing the hearing assessments and administrative duties, Nicholas S. Reed, AuD, PhD for the ShoeBox audiometry protocol, and Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD for mentorship.

Grant Support: National Institute on Aging K23AG057832, L30AG060513, Triological Society Career Development Award, Triological Society/American College of Surgeons Clinician-Scientist Award, Gerstner Scholar Award (JSG), R01AG050440, RF1AG051556, R01AG055299, R56AG061817, K24AG045334 (JAL), UL1TR001873 (Columbia CTSA)

Conflicts of Interest/Financial Disclosures: Justin S. Golub: travel expenses for industry-sponsored meetings (Cochlear, Advanced Bionics, Oticon Medical), consulting fees or honoraria (Oticon Medical, Auditory Insight, Optinose, Abbott, Decibel Therapeutics), department received unrestricted educational grants (Storz, Stryker, Acclarent, 3NT, Decibel Therapeutics). José A Luchsinger: editor-in-chief stipend (Alzheimer’s Disease & Associated Disorders), consulting fees (vTv Therapeutics)

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation: This manuscript corresponds to an oral presentation at the Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting January 23–25, 2020 in Coronado, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goman AM, Lin FR. Prevalence of Hearing Loss by Severity in the United States. Am J Public Health 2016; 106:1820–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yaffe K Modifiable Risk Factors and Prevention of Dementia: What Is the Latest Evidence? JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178:281–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taljaard DS, Olaithe M, Brennan-Jones CG, Eikelboom RH, Bucks RS. The relationship between hearing impairment and cognitive function: a meta-analysis in adults. Clin Otolaryngol 2016; 41:718–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters R, Booth A, Rockwood K, Peters J, D’Este C, Anstey KJ. Combining modifiable risk factors and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019; 9:e022846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller G, Miller C, Marrone N, Howe C, Fain M, Jacob A. The impact of cochlear implantation on cognition in older adults: a systematic review of clinical evidence. BMC Geriatr 2015; 15:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loughrey DG, Kelly ME, Kelley GA, Brennan S, Lawlor BA. Association of Age-Related Hearing Loss With Cognitive Function, Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018; 144:115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alzheimer’s A 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2016; 12:459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golub JS, Luchsinger JA, Manly JJ, Stern Y, Mayeux R, Schupf N. Observed Hearing Loss and Incident Dementia in a Multiethnic Cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65:1691–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol 2011; 68:214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chern A, Golub JS. Age-related Hearing Loss and Dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2019; 33:285–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin FR, Albert M. Hearing loss and dementia - who is listening? Aging Ment Health 2014; 18:671–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin FR, Ferrucci L, An Y et al. Association of hearing impairment with brain volume changes in older adults. Neuroimage 2014; 90:84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong NM, An Y, Doshi J et al. Association of Midlife Hearing Impairment With Late-Life Temporal Lobe Volume Loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckert MA, Cute SL, Vaden KI Jr., Kuchinsky SE, Dubno JR. Auditory cortex signs of age-related hearing loss. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2012; 13:703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker T, Cash DM, Lane C et al. Pure tone audiometry and cerebral pathology in healthy older adults. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neff RM, Jicha G, Westgate PM, Hawk GS, Bush ML, McNulty B. Neuropathological Findings of Dementia Associated With Subjective Hearing Loss. Otol Neurotol 2019; 40:e883–e893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu W, Zhang C, Li JQ et al. Age-related hearing loss accelerates cerebrospinal fluid tau levels and brain atrophy: a longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY) 2019; 11:3156–3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luchsinger JA, Cabral R, Eimicke JP, Manly JJ, Teresi J. Glycemia, Diabetes Status, and Cognition in Hispanic Adults Aged 55–64 Years. Psychosom Med 2015; 77:653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson GP, Sladen DP, Borst BJ, Still OL. Accuracy of a Tablet Audiometer for Measuring Behavioral Hearing Thresholds in a Clinical Population. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 153:838–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings JL. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mucke L, Selkoe DJ. Neurotoxicity of amyloid beta-protein: synaptic and network dysfunction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2:a006338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Honig LS, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R. Aggregation of vascular risk factors and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2005; 65:545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deal JA, Betz J, Yaffe K et al. Hearing Impairment and Incident Dementia and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: The Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017; 72:703–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurgel RK, Ward PD, Schwartz S, Norton MC, Foster NL, Tschanz JT. Relationship of hearing loss and dementia: a prospective, population-based study. Otol Neurotol 2014; 35:775–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loughrey DG, Kelly ME, Kelley GA, Brennan S, Lawlor BA. Association of Age-Related Hearing Loss With Cognitive Function, Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2018; 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golub JS, Brickman AM, Ciarleglio AJ, Schupf N, Luchsinger JA. Association of Subclinical Hearing Loss With Cognitive Performance. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golub JS, Brickman AM, Ciarleglio AJ, Schupf N, Luchsinger JA. Audiometric Age-Related Hearing Loss and Cognition in the Hispanic Community Health Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin FR, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ, An Y, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Hearing loss and cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychology 2011; 25:763–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian ZJ, Chang PD, Moonis G, Lalwani AK. A novel method of quantifying brain atrophy associated with age-related hearing loss. Neuroimage Clin 2017; 16:205–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peelle JE, Troiani V, Grossman M, Wingfield A. Hearing loss in older adults affects neural systems supporting speech comprehension. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2011; 31:12638–12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin FR. Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011; 66:1131–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinha UK, Hollen KM, Rodriguez R, Miller CA. Auditory system degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1993; 43:779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores A How the U.S. Hispanic population is changing Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/18/how-the-u-s-hispanic-population-is-changing/. Accessed May 8, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table S1. Scattergram of Hearing Levels

Supplemental Table S2. Regression Models for Regional Amyloid Standardized Uptake Value Ratio (SUVR) Based on Hearing