Abstract

Treatment of locoregionally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma involves a multidisciplinary approach that combines surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy. These curative strategies are associated with significant acute and long‐term toxicities. With the emergence of human papillomavirus (HPV) as an etiologic factor associated primarily with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, higher cure rates juxtaposed with substantial treatment‐related morbidity and mortality has led to interest in de‐escalated therapeutic strategies, with the goal of optimizing oncologic outcomes while reducing treatment‐related toxicity. Currently explored strategies include replacing, reducing, or omitting cytotoxic chemotherapy; reducing dose or volume of radiotherapy; and incorporation of less‐invasive surgical approaches. Potential biomarkers to select patients for treatment de‐escalation include clinical risk stratification, adjuvant de‐escalation based on pathologic features, response to induction therapy, and molecular markers. The optimal patient selection and de‐escalation strategy is critically important in the evolving treatment of locoregional head and neck cancer. Recently, two large phase III trials, RTOG 1016 and De‐ESCALaTE, failed to de‐escalate treatment in HPV‐associated head and neck cancer by demonstrating inferior outcomes by replacing cisplatin with cetuximab in combination with radiation. This serves as a cautionary tale in the future design of de‐escalation trials in this patient population, which will need to leverage toxicity and efficacy endpoints. Our review summarizes completed and ongoing de‐escalation trials in head and neck cancer, with particular emphasis on biomarkers for patient selection and clinical trial design.

Implications for Practice

The toxicity associated with standard multimodality treatment for head and neck cancer underscores the need to seek less‐intensive therapies with a reduced long‐term symptom burden through de‐escalated treatment paradigms that minimize toxicity while maintaining oncologic control in appropriately selected patients. Controversy regarding the optimal de‐escalation strategy and criteria for patient selection for de‐escalated therapy has led to multiple parallel strategies undergoing clinical investigation. Well‐designed trials that optimize multimodal strategies are needed. Given the absence of positive randomized trials testing de‐escalated therapy to date, practicing oncologists should exercise caution and administer established standard‐of‐care therapy outside the context of a clinical trial.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Human papillomavirus, Treatment de‐escalation, Multimodality therapy

Short abstract

This review summarizes completed and ongoing clinical trials evaluating treatment de‐escalation in head and neck cancer, with an emphasis on biomarkers for patient selection and trial design.

Introduction

Historically, head and neck cancer (HNC) treatment has represented an epitome of a multidisciplinary approach that generally includes surgery, radiotherapy (RT), and systemic therapy. Approximately two‐thirds of patients present with locoregionally advanced disease treated with some combination of these three therapeutic modalities [1]. Over the past 2 decades, human papillomavirus (HPV) has emerged as an etiologic factor associated primarily with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) [2]. HPV‐associated disease results in higher rates of cure compared with HPV‐negative disease with current treatment paradigms [3]. Significant acute and long‐term toxicities are associated with curative multimodality approaches for locoregionally advanced HNC [4]. The notably improved clinical outcomes in HPV‐associated head and neck cancer juxtaposed with significant treatment‐related morbidity and mortality has led to interest in the development of de‐escalated therapeutic strategies with the goal of maintaining or further improving oncologic outcomes while reducing short and long‐term toxicity.

Multiple distinct strategies for treatment de‐escalation are currently being investigated with this goal in mind. Broadly, these strategies can be considered in the context of reducing, replacing, or omitting cytotoxic chemotherapy, reducing dose or volume of RT, and reincorporating less‐invasive surgical approaches. Identification of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) who are candidates for treatment de‐escalation varies across trials, and is a critical differentiator among de‐escalation strategies. The heterogeneity of approaches demands a concerted effort to review evidence from emerging de‐escalation strategies with a look toward future investigation.

The Changing Face of Head and Neck Cancer

Head and neck cancer remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [5, 6]. Although HNSCCs attributable to tobacco and alcohol consumption have been decreasing in incidence since the 1980s, associated with reduced smoking rates in the U.S. [7], oropharynx cancer has initially remained constant and subsequently started to rise despite the reduction in tobacco use in the U.S. [8, 9] relating to an increasing fraction of oropharyngeal HNSCC associated with high‐risk HPV, in particular the HPV16 subtype [2, 8, 10]. Gillison et al. provided strong evidence of a causal relationship between HPV infection and oropharyngeal cancer [11].

HPV‐positive (HPV+) OPSCC has unique clinical and histopathologic characteristics such as early stage primary tumor and more advanced nodal disease [12, 13, 14]. Although historically associated with younger age, recently increased incidence in older adults has been observed [14]. Subset analyses of multiple large randomized controlled trials demonstrated that HPV+ OPSCC was associated with significantly higher cure rates compared with its HPV‐negative counterparts [3, 15, 16]. In the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 0129 trial in which 433 patients were randomized to RT with either accelerated fractionation with concomitant boost or standard fractionation with concurrent cisplatin, it was noted that of the 74.6% of patients who underwent testing for HPV (assessed based on p16 status), clinical outcomes were significantly better in the HPV+ compared with the HPV‐negative patients, with an 8‐year overall survival of 71% versus 30% respectively (hazard ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.22–0.52) [3].

These prognostic findings led to a reevaluation of staging HPV‐associated OPSCC [12], which has been adapted into the most recent Union for International Cancer Control and American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition staging manual to reflect the improved prognosis of this patient cohort [17]. To better prognosticate HPV+ disease, many patients previously categorized as seventh edition TNM stage III–IV are TNM stage I in the eighth edition staging [12]. Importantly, the eighth edition clinical staging paradigm for HPV+ disease was developed under historically intensive treatment regimens. As such, the modified clinical staging for HPV+ disease is not intended to guide clinical decision making. The trials discussed below are based on the seventh edition staging paradigm; however, as de‐escalation trials emerge for HPV+ disease, it will be critical to pay close attention to differences in staging systems used.

Treatment‐Related Toxicity Following Chemoradiotherapy in the Treatment of Locoregional HNSCC

The treatment for locoregional HNSCC has evolved regarding the role of radiation, surgery, and systemic therapy. Historically, in the first half of the 20th century, radiation therapy was the primary treatment, which shifted to include surgery in the middle 20th century with or without adjuvant radiation [1]. This strategy demonstrated high locoregional failure and distant failure rates of approximately 30% and 20%, respectively, with 5‐year survival rates around 40% [18, 19]. In the 1990s, a shift toward functional outcomes and introduction of chemotherapy led to the development of organ preservation strategies [1, 20]. Subsequent randomized clinical trials demonstrated a role for concomitant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for the definitive treatment of locoregional HNSCC [21, 22]. This was further supported by the MACH‐NC meta‐analysis demonstrating a survival benefit with a concurrent rather than sequential strategy, which was greatest for platinum containing regimens [23]. The survival benefit noted with the addition of concomitant chemotherapy to radiation is predominantly through improved locoregional control [23]. Definitive therapy with concurrent CRT has thus become a standard treatment approach for locoregional HNSCC [24].

Despite these important advances, both acute and late complications of treatment with concurrent CRT remain a major concern. Late toxicities of CRT can have a significant impact on function and quality of life in long‐term survivors of HNSCC. Despite improvements in RT techniques, late toxicities such as xerostomia, long‐term poor dental and oral health, fibrosis, trismus, and esophageal stenosis greatly impact survivorship [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]. Ototoxicity secondary to cisplatin concurrent with radiation results in long‐term ototoxicity rates of approximately 20% [31] and is a limiting factor in delivering optimal cumulative doses of cisplatin. A pooled analysis from three RTOG trials of patients with locally advanced HNSCC treated with concurrent CRT suggested that 43% of patients had a severe late toxicity [4]. Taken together, studies of long‐term complications of treatment have a significant impact on quality of life in long‐term head and neck cancer survivors [27, 28, 32, 33, 34].

Current Landscape of Treatment De‐Escalation Strategies

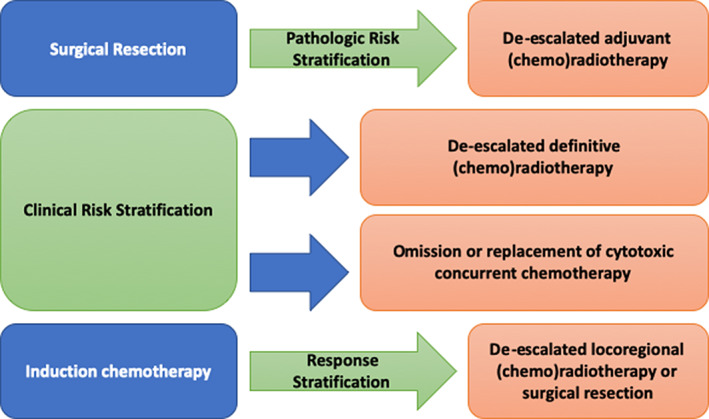

The emergence of HPV‐associated OPSCC as a highly curable malignancy, albeit at the cost of significant treatment‐related morbidity, has led to an interest in developing de‐escalated treatment strategies with the goal of maintaining oncologic outcomes while reducing short and long‐term toxicity. Broadly, strategies for deintensification of therapy include replacing, reducing, or omitting cytotoxic chemotherapy; reducing dose or volume of RT; and incorporation of less‐invasive surgical approaches (Fig. 1) [35, 36].

Figure 1.

Approaches to de‐escalation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Replacing, Reducing, or Omitting Cytotoxic Chemotherapy

One strategy of deintensification is combining RT with targeted therapy rather than cytotoxic chemotherapy [37, 40]. A large randomized phase III trial of concurrent cetuximab with RT versus RT alone demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in locoregional control of 24.4 months in the cetuximab arm compared with 14.9 months in the RT alone arm [37]. There was corresponding improvement in overall survival (OS) of 49 and 29.3 months in the cetuximab and RT alone arms, respectively (p = .03). This finding was also noted in subset analysis of the HPV‐positive subset of patients in this trial [38], which suggested the value of comparing the combination strategy of cetuximab with RT versus cisplatin with RT with the goal of maintaining high rates of disease control while reducing toxicity (Table 1) [39, 40].

Table 1.

Strategies to replace, reduce, or omit cytotoxic chemotherapy

| Trial Name | Patient population | n | Design | Outcome measure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replacing cytotoxic chemotherapy | |||||

| DeESCALaTE | T3–4N0 or T1–4N1–3, <10 PY smoking, HPV+ | 334 | CRT with cisplatin vs. cetuximab | 2‐yr OS (97.5% vs. 89.4%; p = .001) | Mehanna et al. [39] |

| RTOG 1016 | T3–4N0 or T1–4N1–3, HPV+ | 849 | CRT with cisplatin vs. cetuximab | 2‐yr OS 84.6% vs. 77.9%; | Gillison et al. [40] |

| Reducing cytotoxic chemotherapy | |||||

| RTOG 0129 | T3–4N0; T2‐4N2–3; ~64% HPV+ | 721 | CRT with standard vs. accelerated fractionation with cisplatin 100 mg/m2 for 3 vs. 2 cycles | No significant difference in OS | Nguyen‐Tan et al. [3] |

| UNC/UF study | T0–3N0–2c, minimal smoking hx | 44 | CRT with cisplatin 30 mg/m2 weekly with RT to 60 Gy | 3‐yr OS 95% | Chera et al. [43] |

| UNC/UF study LCCC1413 | T0–3, N0–2, minimal smoking hx | 114 | CRT with weekly cisplatin 30 mg/m2, or RT alone T0–2N0–1 | 2‐yr PFS 88% | Chera et al. [45] |

| Omitting definitive chemotherapy | |||||

| NRG‐HN002 | T1–3N1–2b, T3N0, <10 PY | 306 | 60 Gy of accelerated RT vs. 60 Gy with weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2 | 2‐year PFS 90.5% (cisRT) vs. 87.6% (RT alone) | Yom et al. [41] |

Abbreviations: cisRT, cisplatin radiotherapy; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; HPV, human papillomavirus; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; PY, pack‐years; RT, radiotherapy; UNC/UF, University of North Carolina and University of Florida.

Mehanna and colleagues reported results of the DeESCALaTE HPV trial in which 334 patients with low‐risk HPV‐positive oropharyngeal SCC were randomized to cisplatin or cetuximab with RT [39]. They found that there was no difference in overall severe toxicity and that there was worse 2‐year OS in the cetuximab arm of 89.4% compared with the cisplatin arm of 97.5% (p = .0012), attributed to worse disease control (16.1% vs. 6.0% respectively; p = .0007). A similar finding was seen by Gillison and colleagues in the NRG Oncology RTOG 1016 trial [40]. In this trial, 849 patients were randomized to either cisplatin or cetuximab with standard RT. Although this trial was designed as a noninferiority trial, OS was significantly worse in the cetuximab arm compared with the cisplatin arm, with estimated 5‐year OS of 77.9% and 84.6%, respectively. There was an increased risk of locoregional failure seen in the cetuximab arm compared with the cisplatin arm, with 5‐year LRF of 17.3% versus 9.9%, respectively. In combination, the results of the DeESCALaTE HPV trial and the RTOG 1016 trial underscore the importance of caution in deintensification strategies in this disease cohort [42].

The reduction in cytotoxic chemotherapy concurrent with RT has also been evaluated. In the RTOG 0129 study [3], patients were randomized to either high‐dose cisplatin 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for 3 doses concurrent with standard fractionation of 70 Gy in 35 fractions over 7 weeks or cisplatin 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for 2 doses concurrent with accelerated fractionation of 72 Gy in 42 fractions over 6 weeks. No difference in overall survival was noted; however, because of variability in both radiation and cisplatin, definitive conclusions are limited but suggest the safety and feasibility of reducing total cisplatin dose. Chera and colleagues [43], in collaboration between University of North Carolina and University of Florida, treated low‐risk patients (minimal smoking history, T0–3, N0–2c) with weekly cisplatin 30 mg/m2 with concurrent radiation to 60 Gy, followed by biopsy of primary and lymph node dissection, demonstrating an 86% pathologic complete response rate. The 3‐year OS was excellent at 95%, and 39% of patients requiring a temporary feeding tube. A follow‐up study of an additional 114 patients demonstrated 2‐year progression‐free survival (PFS) of 88% [44].

Omission of concurrent cytotoxic chemotherapy was evaluated in the recently reported NRG‐HN‐002 study in which 306 patients with T1–3N1–2b disease or T3N0 disease were randomized to 60 Gy with accelerated radiation, compared with 60 Gy with standard fractionation concurrent with weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2 for 6 cycles [45]. This study demonstrated improved PFS in the concurrent cisplatin arm, with 2‐year PFS of 90.5% meeting the statistical noninferiority margin in the study, whereas PFS in the accelerated RT alone arm was 87.6% and did not meet the noninferiority margin. A subsequent NRG study, NRG‐HN005 study, randomizes patients to standard radiation to 70 Gy with concurrent cisplatin 100 mg/m2 for 2 cycles versus 60 Gy of radiation with concurrent cisplatin 100 mg/m2 for 2 cycles, and 60 Gy of radiation with concurrent nivolumab (NCT03952585) and is currently accruing.

These results further underscore the importance of caution in reducing, replacing, or omitting concurrent chemotherapy in the definitive management of locoregional HPV+ OPSCC. In particular, the RTOG 1016 and DeESCALaTE studies demonstrating inferior oncologic outcomes with concurrent cetuximab compared with cisplatin, as well as the results of the NRG‐HN‐002 study that demonstrates inferiority of radiation alone compared with concurrent cisplatin, further support that the favorable outcomes of HPV+ OPSCC in definitive chemoradiation trials is likely attributable at least in part to the increased chemotherapy and RT sensitivity of these diseases. Contribution to long‐term toxicity with definitive chemoradiation is in large part related to RT dose and volume [46, 47, 48], which is supported by comparable toxicity between arms in RTOG 1016 and DeESCALaTE.

Minimally Invasive Surgical Approaches with De‐Escalated Adjuvant (Chemo)radiotherapy

In recent years, minimally invasive surgical techniques have relaunched the discussion of risk/benefit considerations of upfront surgical versus chemoradiotherapeutic strategy. Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) is a minimally invasive surgical technique that permits resection of pharyngeal tumors through an open mouth, resulting in significantly improved surgical morbidity (Table 2) [49].

Table 2.

Minimally invasive surgical approaches with de‐escalated adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy

| Trial name | Patient population | Design | Clinical trial identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG 3311 [51] | Stage III/IV HPV+ OPSCC | (a) Low risk (T1–2/N0–1) → TORS alone. (b) Intermediate risk → randomized to RT to 50 vs 60 Gy (c) High risk (+ECE, +extensive nodal disease) → CRT with weekly cisplatin 40mg/m2 to 60–66Gy | NCT01898494 |

| PATHOS | HPV+ OPSCC | (a) Low risk → TORS alone. (b) Intermediate risk → randomized to RT to 50 or 60 Gy; (c) High risk (+margin or ECE) are randomized to RT to 60 Gy ± cisplatin (either 3 weekly or weekly according to local practice) | NCT02215265 |

| MC1273 [53] | Locally advanced HPV+ OPSCC | TORS → 30–36 Gy in 1.5–1.8 Gy b.i.d. fractions over 2 weeks with docetaxel 15 mg/m2 × 2 | NCT01932697 |

| DART‐HPV Mayo | Locally advanced HPV+ OPSCC | Randomization to MC1273 regimen (described above) versus 60 Gy/2 Gy daily fractions ± concurrent weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2 | NCT02908477 |

| Adjuvant de‐esc RT + nivo | HPV+ intermediate risk (>5+ LNs, N2c/3, +ECE > 1 mm, +margin) | TORS → 45–50Gy RT with concurrent and adjuvant nivolumab | NCT03715946 |

Abbreviations: +, positive; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; ECE, extracapsular extension; HPV, human papillomavirus; LN, lymph node; nivo, nivolumab; OPSCC, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma; RT, radiotherapy; TORS, transoral robotic surgery.

Performing surgical resection upfront leads to precise pathologic information that can be used for risk stratification in deintensification [36]. This was evaluated in the ECOG 3311 trial in which patients with HPV+ OPSCC undergo TORS and are stratified based on pathologic results. Low‐risk patients (negative margins, N0–1, no extracapsular extension [ECE]) are treated with surgical therapy alone, whereas high‐risk patients (positive margins, >1 mm ECE, or ≥5 positive nodes) are treated with adjuvant concurrent CRT to 66 Gy with weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2 [51]. Intermediate‐risk patients (close margins <3 mm, 2–4 positive lymph nodes, ≤1 mm ECE, perineural invasion/lymphovascular invasion) are then randomized to 50 Gy or 60 Gy adjuvant RT. Results of this trial were recently presented demonstrating that among 206 intermediate‐risk patients randomized to 50 Gy versus 60 Gy adjuvant RT, 2‐year PFS was 95.0% and 95.9%, respectively [51]. This informs de‐escalated adjuvant therapy in patients who undergo surgery, but this upfront surgical strategy will need to be compared with a de‐escalated definitive chemoradiotherapeutic approach in terms of oncologic and functional outcomes to clarify whether surgery is necessary. Similarly, the PATHOS trial in the U.K. is stratifying patients by pathologic risk group. Low‐risk patients receive surgery alone, intermediate‐risk patients (T3, N2a–b with perineural or vascular invasion or close margins) are randomized to two arms either 60 Gy or 50 Gy, and high‐risk patients (positive margins or ECE) are randomized to RT to 60 Gy with or without concurrent cisplatin (Table 2) [36]. Other deintensification strategies in HPV+ disease are evaluating the question of treatment implications for tumors with ECE on surgical resection, given controversial retrospective data suggesting lack of prognostic significance in HPV+ disease [52]. The Adjuvant De‐escalation, Extracapsular Spread, P16+, Transoral trial attempted to randomize HPV+ patients to adjuvant CRT or RT alone (NCT01687413) however, this trial unfortunately closed because of poor accrual. Ultimately for patients requiring postoperative (C)RT, the benefit of upfront surgical resection versus a de‐escalated definitive CRT approach remains an open question. As such, an adjuvant paradigm will need to be considered in the context of evolving definitive de‐escalated CRT.

A novel adjuvant de‐escalation approach from the Mayo Clinic group is investigating a substantial reduction in radiation dose and duration with concurrent docetaxel. This trial included patients with p16+ tumors with minimal smoking history and negative margins who underwent surgical resection. A total of 37 patients without ECE were treated with 30 Gy delivered in 1.5‐Gy fractions over 2 weeks with weekly docetaxel 15 mg/m2 for 2 weeks. An additional 43 patients with ECE were treated with a simultaneous integrated boost to nodal levels with ECE to 36 Gy in 1.8‐Gy twice‐daily fractions for 2 weeks with the same chemotherapy [53]. The 2‐year PFS was reported at 91.1% for this cohort overall, with a median follow‐up of 36 months. A follow‐up phase III trial is currently enrolling (NCT02908477) randomizing patients to this regimen versus standard adjuvant treatment of radiation with or without concurrent cisplatin. Results from this novel adjuvant approach are eagerly awaited as a strategy to optimize minimally invasive surgical approach while aggressively de‐escalating radiation dose. An ongoing trial is evaluating de‐escalated adjuvant therapy following minimally invasive surgery incorporating nivolumab, an anti–programmed death‐1 monoclonal antibody, both concurrent and following de‐escalated radiation (NCT03715946).

Reduction in Radiotherapy Dose Following Induction Chemotherapy

Response to induction therapy to select patients for subsequent de‐escalation is a strategy being investigated (Table 3). The ECOG 2399 study evaluated 96 patients with stage III or IV HNSCC treated with two cycles of induction paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by weekly concomitant paclitaxel with standard fractionation RT [54]. A total of 40% of patients had oncogenic HPV positivity detected. Patients with HPV‐positive HNSCC demonstrated higher response rates compared with HPV‐negative tumors, with response rates of 82% and 55%, respectively (p = .01). The 2‐year OS was also improved in the HPV‐positive cohort compared with the HPV‐negative cohort with 2‐year OS rates of 95% versus 62%, respectively (p = .005).

Table 3.

Strategies involving induction followed by risk‐adapted locoregional therapy

| Trial name | Patient population | n | Design | Outcome measure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG 2399 | Stage III/IV oropharynx/larynx (40% HPV) | 96 | Carboplatin and paclitaxel ×2 cycles → CRT with weekly paclitaxel |

2‐yr OS 95% (HPV+) vs. 62% (HPV−) RR: 82% (HPV+) vs. 55% (HPV−) |

Fakhry et al. [54] |

| ECOG 1308 | HPV+ OPSCC | 90 | Cisplatin, paclitaxel, and cetuximab → CRT with concurrent cetuximab to 54 Gy (CR) or 69.3 Gy (<CR) | 2‐yr PFS 78%; 2‐yr OS 91% | Marur et al. [58] |

| RAVD | Locally advanced HNSCC (63% HPV+) | 94 | Cisplatin, paclitaxel, cetuximab ± everolimus → volume de‐escalation (>50% shrinkage) | G‐tube dependence at 6 mo (5.7% in de‐escalated vs. 32.6%; p = .005) | Villaflor et al. [59] |

| OPTIMA | Locally advanced HPV+ OPSCC | 62 | Carboplatin and nab‐paclitaxel ×3 cycles → (a) 50 Gy (low risk, >50% shrinkage) (b) CRT 45 Gy (low 30%–50%; high risk >50%) (c) CRT 75 Gy (high risk <30%) | 2‐year PFS 94% | Seiwert et al. [60] |

| Chen et al. | Locally advanced HNSCC | 45 | Carboplatin and paclitaxel ×2 cycles → CRT with paclitaxel to 54 Gy (PR/CR) or 60 Gy (<PR) | 2‐yr PFS 92% | Chen et al. [61] |

| OPTIMA 2 | Locally advanced HPV+ HNSCC | Carboplatin/nab‐paclitaxel/nivoumab ×3 cycles → risk and response‐adapted locoregional therapy | NCT03107182 | ||

| DEPEND | Locally advanced HPV‐ HNSCC | Carboplatin/nab‐paclitaxel/nivoumab ×3 cycles → risk and response‐adapted locoregional therapy | NCT03944915 |

Abbreviations: –, negative; +, positive; CR, complete response; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HPV, human papillomavirus; OPSCC, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; PR, partial response.

It has long been identified that response to induction chemotherapy is predictive of response to subsequent RT or CRT [55, 56, 57]. In the E1308 trial, 90 patients with HPV+ OPSCC were treated with 3 cycles of induction therapy with cisplatin, paclitaxel, and cetuximab followed by RT to 54 Gy with weekly cetuximab in patients with a primary‐site complete clinical response or 69.3 Gy with cetuximab in patients with less than complete clinical response. A total of 70% of patients achieved a clinical complete response (CR) and were treated to 54 Gy, whereas the remaining patients who did not achieve a CR were treated to 69.3 Gy, each with concomitant cetuximab. Patients treated to 54 Gy had 2‐year PFS and OS of 80% and 94%, respectively, and improved swallowing function and nutrition at 12 months [58, 62].

Our team at The University of Chicago has investigated beyond radiation dose de‐escalation, a role for radiation volume de‐escalation following induction therapy. A total of 94 patients with locally advanced HNSCC (63% HPV+) were treated with two cycles of induction chemotherapy followed by response‐adapted volume de‐escalation (elimination of elective nodal coverage) in patients with ≥50% tumor shrinkage following induction [59]. This strategy demonstrated reduced long‐term toxicity with significantly less G‐tube dependence at 6 months (5.7% versus 32.6%; p = .005), without compromising outcomes with >90% of locoregional failures developing within the radiation treatment volumes and occurring in the highest risk PTV1.

Subsequently, we built upon these published results with our institutional OPTIMA trial, a phase II dose and volume de‐escalation trial with risk stratification and response to induction therapy [60]. In this trial, 62 patients with HPV+ OPSCC were enrolled, of whom 28 were low risk (T1–3, N0–2b, and less than 10 pack‐years smoking history), and 34 were high risk (T4, N2c–N3, or greater than 10 pack‐years smoking history). All patients received induction with carboplatin and nab‐paclitaxel for 3 cycles. Patients with low‐risk disease with ≥50% response received de‐escalated radiation to 50 Gy; low‐risk patients with 30%–50% tumor shrinkage and high‐risk patients with ≥50% response were treated with de‐escalated concurrent CRT to 45 Gy with twice‐daily radiation and paclitaxel, 5‐fluorouracil, and hydroxyurea (TFHX) week‐on week‐off. Low‐risk patients with less than 30% shrinkage and high‐risk patients with less than 50% shrinkage were treated with standard‐dose concurrent CRT to 75 Gy with twice‐daily fractions concurrent with TFHX week‐on week‐off. Results of this trial demonstrated that in the low‐risk cohort, 2‐year PFS and OS were 95% and 100%, respectively. In the high‐risk cohort, 2‐year PFS and OS were 94% and 97%, respectively. Acute toxicities were significantly reduced in the de‐escalated cohorts, demonstrating significantly lower rates of grade 3+ mucositis, dermatitis, and need for enteral feeding.

A study evaluating a similar approach by Chen et al. evaluated 45 patients with locally advanced HNSCC who were treated with two cycles of induction with carboplatin plus paclitaxel, followed by reduced‐dose concurrent CRT with paclitaxel to 54 Gy in partial and complete responders, and 60 Gy in nonresponders [61]. The Mount Sinai group randomized patients to induction docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5‐FU with a favorable response to standard dose (70 Gy) versus dose reduced (56 Gy) with concurrent carboplatin (NCT01706939), which unfortunately closed because of poor accrual and lack of financial support. Other induction strategies have included neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by transoral surgery [50] and neoadjuvant immunotherapy followed by transoral surgery [63]; however, these trials were small (17 and 28 patients, respectively) and therefore limit definitive conclusions.

The role of immunotherapy in the paradigm for treatment de‐escalation is evolving. The REACH study is randomizing patients to avelumab, an anti‐programmed death ligand 1 monoclonal antibody, with cetuximab and RT versus cisplatin or cetuximab and RT (NCT02999087). The JAVELIN head and neck study is randomizing patients to avelumab, with CRT versus CRT alone (NCT02952586). EMD‐Serono and Pfizer announced that the JAVELIN study will be terminated as the study is unlikely to show a statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint of PFS based on a preplanned interim analysis [64]. The KEYNOTE 412 study is randomizing patients to pembrolizumab with CRT versus CRT alone (NCT03040999). At the University of Chicago, our team is incorporating immunotherapy both as a component of an induction chemoimmunotherapy regimen and in the adjuvant setting both for HPV+ disease (OPTIMA II; NCT03107182) and HPV‐negative disease (DEPEND; NCT03944915). Early results of our institutional OPTIMA II trial of patients treated with induction carboplatin, nab‐paclitaxel, and nivolumab followed by TORS or RT (50 Gy) alone demonstrated favorable results with excellent oncologic outcomes with reduced toxicity [65].

Novel Strategies for Selecting Patients for Treatment De‐Escalation

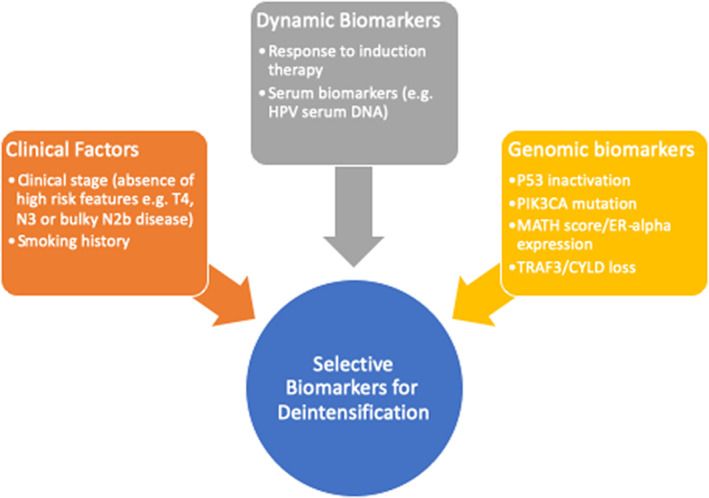

The heterogeneity of deintensification clinical trials in head and neck cancer include variability in strategies for patient selection for de‐escalation. HPV positivity has clearly been established as a favorable prognostic and predictive biomarker and, as a result, has been the major focus of deintensification efforts. Clinical factors that have been identified as high‐risk features include staging factors such as T4 tumor stage, bilateral nodal disease, or N3 nodal conglomerate. Significant smoking history has been identified as a high‐risk feature in HPV+ OPSCC and has been identified as an exclusion for multiple deintensification trials. Response to induction therapy as a biomarker for treatment de‐escalation is being applied in multiple trials as well. Improved predictive and prognostic biomarkers are needed to enhance the next generation of biomarker selected de‐escalation trials in head and neck cancer (See Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Biomarker selection for treatment deintensification in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; HPV, human papillomavirus; MATH, mutant allele tumor heterogeneity.

Recently, genomic biomarkers have become of interest to further characterize tumor biology. Mutations in PIK3CA, which is commonly mutated in HPV+ OPSCC and has been associated with worse disease‐free survival compared with PIK3CA wild‐type tumors in de‐escalation trials, suggests a potential role as a genomic biomarker [66]. Mutations in p53 have been associated with smoking‐related HPV‐negative cancer and likely characterize tumors driven by smoking oncogenesis and may identify a poor risk population [67]. Other molecular biomarkers have included mutant allele tumor heterogeneity (MATH), which is a quantitative measure of intratumor genetic heterogeneity and is associated with worse outcomes, and estrogen receptor (ER)‐α expression was found to be a favorable prognosis. Using composite biomarker of high MATH score, low ER‐α expression, and HPV negative, hazard ratio was 28.2 (p = .0001). TRAF3 and CYLD loss by inactivating mutations or deletions have been associated with a favorable prognosis among HPV+ OPSCC and is associated with episomal HPV and activation of NF‐kB [68].

Other biomarkers under active investigation include serum HPV circulating tumor DNA assays. Serum‐based biomarkers are of substantial interest in selecting patients not only for upfront prognostication but also as a dynamic biomarker of treatment response and risk of recurrence following treatment [69, 70]. A prospective clinical trial of 115 patients with HPV+ OPSCC treated with definitive concurrent CRT assessed the role of a plasma‐based circulating tumor HPV DNA biomarker [70]. Plasma‐circulating tumor HPV DNA demonstrated a negative predictive value of 100% (95% CI, 96%–100%), and two consecutively positive circulating tumor HPV DNA had a positive predictive value of 94% with a median lead‐time of HPV DNA positivity to biopsy proven recurrence of 3.9 months. These promising biomarkers will need to be validated in larger cohorts and in different patient populations and treatment paradigms for broader application, in particular with respect to HPV de‐escalation protocols.

Conclusion

The multitude of novel therapeutic approaches in patients with head and neck cancer continues to grow as we refine our therapeutic strategies with the goal of maximizing oncologic control while minimizing toxicity. The heterogeneity of de‐escalation approaches with patient selection and clinical trial design have limited the broader application of de‐escalated treatment for HPV+ OPSCC and thus remains investigational. Well‐designed, large, randomized, multicenter clinical trials are needed to refine, optimize, and establish a treatment paradigm for HPV+ OPSCC that optimizes oncologic outcomes while reducing acute and chronic toxicities.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Ari J. Rosenberg, Everett E. Vokes

Collection and/or assembly of data: Ari J. Rosenberg

Data analysis and interpretation: Ari J. Rosenberg, Everett E. Vokes

Manuscript writing: Ari J. Rosenberg, Everett E. Vokes

Final approval of manuscript: Ari J. Rosenberg, Everett E. Vokes

Disclosures

Ari J. Rosenberg: EMD Serono (C/A); Everett E. Vokes: C/A: AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Sqibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron (C/A).

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

References

- 1. Cognetti DM, Weber RS, Lai SY. Head and neck cancer: An evolving treatment paradigm. Cancer 2008;113(7 Suppl):1911–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM et al. Human Papillomavirus and Rising Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4294–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nguyen‐Tan PF, Zhang Q, Ang KK et al. Randomized phase III trial to test accelerated versus standard fractionation in combination with concurrent cisplatin for head and neck carcinomas in the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0129 trial: Long‐term report of efficacy and toxicity. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3858–3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A et al. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: An RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3582–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer Clin 2019;69:7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sturgis EM, Ang KK. The epidemic of HPV‐associated oropharyngeal cancer is here: Is it time to change our treatment paradigms? J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2011;9:665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vokes EE, Agrawal N, Seiwert TY. HPV‐associated head and neck cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107;djv344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M et al. Trends in human papillomavirus‐associated cancers ‐ United States, 1999‐2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:918–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haraf DJ, Nodzenski E, Brachman D et al. Human papilloma virus and p53 in head and neck cancer: Clinical correlates and survival. 1996;2(4):755‐62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:709–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV‐related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON‐S): A multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:440–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gillison ML, D'Souza G, Westra W et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16–positive and human papillomavirus type 16–negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Windon MJ, D'Souza G, Rettig EM et al. Increasing prevalence of human papillomavirus‐positive oropharyngeal cancers among older adults. Cancer 2018;124:2993–2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Posner MR, Lorch JH, Goloubeva O et al. Survival and human papillomavirus in oropharynx cancer in TAX 324: A subset analysis from an international phase III trial. Ann Oncol 2011;22:1071–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rischin D, Young RJ, Fisher R et al. Prognostic significance of p16INK4A and human papillomavirus in patients with oropharyngeal cancer treated on TROG 02.02 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4142–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Amin MB, Edge S, Green F et al, eds. American Cancer Society . AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th ed Chicago, IL: American Joint Committee on Cancer, Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tupchong L, Scott CB, Blitzer PH et al. Randomized study of preoperative versus postoperative radiation therapy in advanced head and neck carcinoma: Long‐term follow‐up of RTOG study 73‐03. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;20:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kramer S, Gelber RD, Snow JB et al. Combined radiation therapy and surgery in the management of advanced head and neck cancer: Final report of study 73‐03 of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Head Neck Surg 1987;10:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group ; Wolf GT, Fisher SG, Hong WK et al. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1685–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brizel DM, Albers ME, Fisher SR et al. Hyperfractionated irradiation with or without concurrent chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1798–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Milicic B, Nikolic N et al. Hyperfractionated radiation therapy with or without concurrent low‐dose daily cisplatin in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:1458–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pignon JP, Maître Al, Maillard E et al. Meta‐analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH‐NC): An update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol 2009;92:4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Head and Neck Cancers (Version 2.2020) Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf. Accessed July, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Lin A, Kim HM, Terrell JE et al. Quality of life after parotid‐sparing IMRT for head‐and‐neck cancer: A prospective longitudinal study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003;57:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Givens DJ, Karnell LH, Gupta AK et al. Adverse Events associated with concurrent chemoradiation therapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;135:1209–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen AM, Daly ME, Farwell DG et al. Quality of life among long‐term survivors of head and neck cancer treated by intensity‐modulated radiotherapy. JAMA Otalaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. El‐Deiry M, Funk GF, Nalwa S et al. Long‐term quality of life for surgical and nonsurgical treatment of head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;131:879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang JJ, Goldsmith TA, Holman AS et al. Pharyngoesophageal stricture after treatment for head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2012;34:967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Barringer DA et al. Late dysphagia after radiotherapy‐based treatment of head and neck cancer. Cancer 2012;118:5793–5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zuur CL, Simis YJ, Lansdaal PE et al. Ototoxicity in a randomized phase III trial of intra‐arterial compared with intravenous cisplatin chemoradiation in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3759–3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duke RL, Campbell BH, Indresano AT et al. Dental status and quality of life in long‐term head and neck cancer survivors. Laryngoscope 2005;115:678–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Funk GF, Karnell LH, Christensen AJ. Long‐term health‐related quality of life in survivors of head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;138:123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Payakachat N, Ounpraseuth S, Suen JY. Late complications and long‐term quality of life for survivors (>5 years) with history of head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2013;35:819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oosthuizen JC, Doody J. De‐intensified treatment in human papillomavirus‐positive oropharyngeal cancer. Lancet 2019;393:5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mirghani H, Blanchard P. Treatment de‐escalation for HPV‐driven oropharyngeal cancer: Where do we stand? Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2018;8:4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous‐cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2006;354:567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosenthal DI, Harari PM, Giralt J et al. Association of human papillomavirus and p16 status with outcomes in the imcl‐9815 phase III registration trial for patients with locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with radiotherapy with or without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 2015;34:1300–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mehanna H, Robinson M, Hartley A et al. Radiotherapy plus cisplatin or cetuximab in low‐risk human papillomavirus‐positive oropharyngeal cancer (De‐ESCALaTE HPV): An open‐label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;393:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gillison ML, Trotti AM, Harris J et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab or cisplatin in human papillomavirus‐positive oropharyngeal cancer (NRG Oncology RTOG 1016): A randomised, multicentre, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2019;393:40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yom SS, Torres‐Saavedra P, Caudell J et al. NRG‐HN002: A randomized phase II trial for patients with p16‐positive, non‐smoking‐associated, locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2019;105:684–685. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mehanna H, Rischin D, Wong SJ, Gregoire V, Ferris R, Waldron J, et al. De‐escalation after DE‐ESCALATE and RTOG 1016: A head and neck cancer intergroup framework for future de‐escalation studies. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:2552–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chera BS, Amdur RJ, Tepper JE et al. Mature results of a prospective study of deintensified chemoradiotherapy for low‐risk human papillomavirus‐associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2018;124:2347–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chera BS, Amdur RJ, Green R et al. Phase II trial of de‐intensified chemoradiotherapy for human papillomavirus‐associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2661–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chera BS, Amdur R, Shen CJ et al. Mature results of the LCCC1413 phase II trial of de‐intensified chemoradiotherapy for HPV‐associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Onco 2019;37(15 suppl):6022a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Foster CC, Seiwert TY, MacCracken E et al. Dose and volume de‐escalation for human papillomavirus‐positive oropharyngeal cancer is associated with favorable posttreatment functional outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;107:662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Curran D, Giralt J, Harari PM et al. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients after treatment with high‐dose radiotherapy alone or in combination with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2191–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fu KK, Pajak TF, Trotti A et al. A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) phase III randomized study to compare hyperfractionation and two variants of accelerated fractionation to standard fractionation radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: First report of RTOG 9003. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;48:7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Holsinger FC, Ferris RL. Transoral endoscopic head and neck surgery and its role within the multidisciplinary treatment paradigm of oropharynx cancer: Robotics, lasers, and clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3285–3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sadeghi N, Li NW, Taheri MR et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and transoral surgery as a definitive treatment for oropharyngeal cancer: A feasible novel approach. Head Neck 2016;38:1837–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ferris RL, Flamand Y, Weinstein GS et al. Transoral robotic surgical resection followed by randomization to low‐ or standard‐dose IMRT in resectable p16+ locally advanced oropharynx cancer: A trial of the ECOG‐ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E3311). J Clin Oncol 2020;38(15suppl):6500a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sinha P, Lewis JS Jr, Piccirillo JF et al. Extracapsular spread and adjuvant therapy in human papillomavirus‐related, p16‐positive oropharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer 2012;118:3519–3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ma DJ, Price KA, Moore EJ et al. Phase II evaluation of aggressive dose de‐escalation for adjuvant chemoradiotherapy in human papillomavirus–associated oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:1909–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus‐positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(4):261‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ensley JF, Jacobs JR, Weaver A et al. Correlation between response to cisplatinum‐combination chemotherapy and subsequent radiotherapy in previously untreated patients with advanced squamous cell cancers of the head and neck. Cancer 1984;54:811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hong WK, Bromer RH, Amato DA et al. Patterns of relapse in locally advanced head and neck cancer patients who achieved complete remission after combined modality therapy. Cancer 1985;56:1242–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Urba S, Wolf G, Eisbruch A et al. Single‐cycle induction chemotherapy selects patients with advanced laryngeal cancer for combined chemoradiation: A new treatment paradigm. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:593–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Marur S, Li S, Cmelak AJ et al. E1308: Phase II trial of induction chemotherapy followed by reduced‐dose radiation and weekly cetuximab in patients with HPV‐associated resectable squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx— ECOG‐ACRIN Cancer Research Group. J Clin Oncol 2016;35:490–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Villaflor VM, Melotek JM, Karrison TG et al. Response‐adapted volume de‐escalation (RAVD) in locally advanced head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol 2016;27:908–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Seiwert TY, Foster CC, Blair EA et al. OPTIMA: A phase II dose and volume de‐escalation trial for human papillomavirus‐positive oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol 2018;30:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chen AM, Felix C, Wang PC et al. Reduced‐dose radiotherapy for human papillomavirus‐associated squamous‐cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: A single‐arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cmelak A, Li S, Marur S et al. Symptom reduction from IMRT dose deintensification: Results from ECOG 1308 using the Vanderbilt Head and Neck Symptom Survey version 2 (VHNSS V2). J Clin Oncol 2015;33(15 suppl):6021a. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ferrarotto R, Bell D, Rubin ML et al. Checkpoint inhibitors assessment in oropharynx cancer (CIAO): Safety and interim results. J Clin Oncol 2019;37(15 suppl):6008a. [Google Scholar]

- 64.EMD Serono and Pfizer Provide Update on Phase III Javelin Head and Neck 100 Study 2020. Pfizer website; 2020. Available at: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/emd_serono_and_pfizer_provide_update_on_phase_iii_javelin_head_and_neck_100_study.

- 65. Rosenberg AJ, Agrawal N, Pearson A et al. Low risk HPV‐associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with induction chemoimmunotherapy followed by TORS or radiotherapy. Presented at: the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancers Symposium; February 27–29, 2020; Scottsdale, AZ.

- 66. Beaty BT, Moon DH, Shen CJ et al. PIK3CA mutation in HPV‐associated OPSCC patients receiving deintensified chemoradiation. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;112:855–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Carlos de Vicente J, Junquera Gutiérrez LM, Zapatero AH et al. Prognostic significance of p53 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma without neck node metastases. Head Neck. 2004;26:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hajek M, Sewell A, Kaech S et al. TRAF3/CYLD mutations identify a distinct subset of human papillomavirus‐associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2017;123:1778–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Routman DM, Chera BS, Jethwa KR et al. Detectable HPV ctDNA in post‐operative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients is associated with progression. Int J Radiat Biol Phys 2019;105:682–683. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chera BS, Kumar S, Shen C et al. Plasma circulating tumor HPV DNA for the surveillance of cancer recurrence in HPV‐associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020:38:1050–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]