Abstract

Tumor xenograft models can create a high capacity to study human tumors and discover efficient therapeutic approaches. Here, we aimed to develop the gamma-radiated immunosuppressed (GIS) mice as a new kind of tumor xenograft model for biomedical studies. First, 144 mice were divided into the control and treated groups exposed by a medical Cobalt-60 apparatus in 3, 4, and 5 Gy based on the system outputs. Then, 144 BALB/c mice were divided into four groups; healthy, xenograft, radiation, and radiation + xenograft groups. The animals in the xenograft and radiation + xenograft groups have subcutaneously received 3 × 106 MCF-7 cells 24 h post-radiation. On 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after cell injection, the animals were sacrificed. Then, the blood samples and the spleen and tumor tissues were removed for the cellular and molecular analyses. The whole-body gamma radiation had a high immunosuppressive effect on the BALB/c mice from 1 to 21 days post-radiation. The macroscopic and histopathological observations have proved that the created clusters' tumor structure resulted in the xenograft breast tumor. There was a significant increase in tumor size after cell injection until the end of the study. Except for Treg, the spleen level of CD4, CD8, CD19, and Ly6G was significantly decreased in Xen + Rad compared to the Xen alone group on 3 and 7 days. Unlike IL-4 and IL-10, the spleen level of TGF-β, INF-γ, IL-12, and IL-17 was considerably decreased in the Xen + Rad than the Xen alone group on 3 and 7 days. The spleen expressions of the VEGF, Ki67, and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio were dramatically increased in the Xen + Rad group compared to the Xen alone on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days. Our results could confirm a new tumor xenograft model via an efficient immune-suppressive potential of the whole-body gamma radiation in mice.

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Cancer, Cell biology, Developmental biology, Genetics, Immunology, Molecular biology, Diseases, Medical research, Molecular medicine, Oncology

Introduction

Several kinds of cancer animal models have been developed to study in the field of cancer research. Carcinogen-induced, syngeneic, xenograft, cell transplanted, and genetically engineered tumor are the main kinds of cancer animal models1. Administration of various types of carcinogens was the first strategy for establishing cancer animal models2,3. Although the carcinogen agents have shown the high efficiency to create animal cancers of human tumors, the lack of coordination between the tumor’s stage, size, and site, and the administration of their high doses are the main limitations of these models2,3.

Syngeneic cancer models are based on the inbred animal-derived cancer lines or tumor tissues into the same inbred animals4. In this context, the lack of orthologous human cancer lines into the inbred animal tumor is the most critical limitation to drug discovery4,5. Thus, several kinds of immune-suppressed and immunodeficient animals have been established to resolve the partial challenges1,5. It has been shown that the immune-suppressive drugs can also increase the immune system tolerance against the xenograft tissues through the inhibition of calcineurin phosphatase, which can prevent B and T lymphocyte maturation following enhance expression of IL-26,7. The cyclosporine A and tacrolimus are the most useful immune-suppressive agents to establish animal models of human tumors8. However, the long-term administration of these agents has undesirable side effects on the animals7,8. On the other hand, the high costs of care and the high mortality rate resulting in lack of effective immune-system response against the contact contaminations are the most important limitations to developing the application of immunodeficient animals in cancer research. In this respect, several studies have demonstrated the immune-destruction and immune-suppression of gamma radiation9,10.

Nowadays, using gamma radiation is an accepted strategy for bone marrow suppression and the destruction of malignant hematopoietic cells in patients with hematologic malignancies9,10. The study on the gamma-radiated bone-marrow-suppressed patients has clearly shown a decreasing immune-system activation rate dramatically after the radiation11. Some studies have shown that gamma radiation can disturb several biological activities of immune cells, including the inhibition of the INF-γ expression and the block of the STAT signaling pathways, which can directly inhibit splenocyte maturation and induce immune suppression10. It has been demonstrated the rate and function of the CD4+/CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg) as the most critical cells in the immune-system tolerance against the xenograft tissues after gamma radiation9. Treg cells' primary function is to promote the suppressive cascades of several T helpers (Th) by inhibiting the IL-17 expression and increasing the INF-γ secretion12. Moreover, increasing the rate of Treg cells can significantly increase the response of CD4+ T, CD8+ T, CD19+/CD20+ B cells, and macrophages against the xenografts13. Here, we first examined the various doses of gamma radiation on BALB/c mice to find the low toxicity of whole-body gamma radiation with maximum efficiency to suppress the immune system. Then, we examined the growth of the xenograft breast tumor and the immune system’s behavior on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after cell injection in the gamma-radiated BALB/c mice.

Results

The dosing procedure of the gamma radiation

The main toxicity signs of various gamma-radiation doses and their potential to immune suppression on 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 30 days after the whole-body radiation have been summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3. The whole-body gamma radiation showed a remarkable safety rate of 3 and 4 Gy doses (Table 1). None of the various doses of the whole-body gamma radiation (3, 4, and 5 Gy) have been accompanied by death. A significant decrease in the animals’ weight was observed on the 3rd day after radiation at 5 Gy dose compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 1.

The hematological and biochemical parameters in the effects of 3 Gy gamma radiation on 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 30 days post-radiation.

| Indexes | Control group | 3 Gy Gamma-radiation group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day | 3 day | 7 day | 14 day | 21 day | 30 day | ||

| Body Weight (g) | 22.5 ± 3 | 22.2 ± 2.1 | 22.6 ± 1.8 | 22.8 ± 2.7 | 23.2 ± 2.6 | 23.7 ± 2.8 | 24.4 ± 3.4 |

| WBC (1000/mm3) | 7.1 ± 1.5 | 7.2 ± 0.5 | 7.4 ± 0.5 | 7.9 ± 0.7 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 2.3 |

| RBC (Millin/mm3) | 9.2 ± 1.7 | 9.1 ± 1.5 | 9.0 ± 1.6 | 9.2 ± 2 | 8.9 ± 2.3 | 8.8 ± 3 | 8.7 ± 3 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 72.7 ± 5.5 | 72.2 ± 10 | 73.5 ± 4.2 | 72.2 ± 3 | 71.9 ± 5.5 | 71.1 ± 4.6 | 72.1 ± 5.5 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 21 ± 3.5 | 25.2 ± 8.3 | 23.5 ± 5.5 | 24.1 ± 8.5 | 22 ± 12 | 21 ± 9 | 21.5 ± 2.9 |

| Monocytes (%) | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 1.8 | 5.7 ± 1.4 | 6.4 ± 1.7 | 6.5 ± 1.7 |

| HCT (%) | 40.8 ± 3 | 40.2 ± 3.5 | 40.1 ± 3.6 | 40.4 ± 2.8 | 39.4 ± 2.9 | 39.3 ± 2.7 | 39.0 ± 3 |

| PLT (1000/mm3) | 1175 ± 110 | 1160 ± 135 | 1165 ± 138 | 1110 ± 205 | 1150 ± 220 | 1115 ± 155 | 1125 ± 129 |

| ALT (U/L) | 1190 ± 135 | 1185 ± 125 | 1133 ± 185 | 1156 ± 175 | 1168 ± 140 | 1176 ± 152 | 1145 ± 97 |

| AST (U/L) | 117 ± 15 | 110 ± 37 | 120 ± 27 | 124 ± 40 | 115 ± 27 | 133 ± 29 | 113 ± 36 |

| ALP (U/L) | 285 ± 35 | 255 ± 65 | 246 ± 77 | 244 ± 75 | 261 ± 65 | 256 ± 58 | 260 ± 44 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 65 ± 12 | 64 ± 15 | 65 ± 15 | 58 ± 18 | 56 ± 15 | 57 ± 17 | 68 ± 17 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.4 ± 0.05 | 0.3 ± 0.06 | 0.4 ± 0.06 | 0.3 ± 0.07 | 0.4 ± 0.07 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.3 ± 0.4 |

| T.P (mg/dL) | 5.8 ± 1.2 | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 1.2 | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 4.9 ± 2.4 | 5.3 ± 1.9 | 6.1 ± 2.3 |

| Glu (mg/dL) | 200 ± 28 | 228 ± 38 | 230 ± 55 | 240 ± 50 | 244 ± 65 | 217 ± 47 | 240 ± 50 |

| B.T (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| B.Direct (mg/dL) | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.45 ± 0.2 | 0.45 ± 0.5 | 0.40 ± 0.3 | 0.40 ± 0.2 | 0.50 ± 0.2 | 0.35 ± 0.1 |

| Alb (mg/dL) | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.9 |

Values are means ± SD. RBC = red blood cell, HCT = hematocrit, WBC = white blood cells, Plt = platelets, BUN = blood urea nitrogen, Cr = creatinine, Glu = glucose, AST = aspartate transaminase, ALT = alanine transaminase, ALP = alkaline phosphatase, Alb = albumin, T.P = total protein, B.T = Bilirubin Total, B.Direct = Bilirubin Direct.

Table 2.

The hematological and biochemical parameters in the effects of 4 Gy gamma radiation on 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 30 days post-irradiation.

| Indexes | Control group | 4 Gy gamma-radiation group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day | 3 day | 7 day | 14 day | 21 day | 30 day | ||

| Body Weight (g) | 21.5 ± 2 | 20.8 ± 2.5 | 20.6 ± 1.8 | 20.8 ± 2.1 | 21.9 ± 2.6 | 23.2 ± 2.2 | 26 ± 2.4 |

| WBC (1000/mm3) | 6.8 ± 1.7 | *2.7 ± 0.6 | *1.28 ± 0.4 | *2.93 ± 0.5 | *3.5 ± 0.6 | 8.8 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 2.2 |

| RBC (Millin/mm3) | 9.3 ± 1.8 | 9.1 ± 1.4 | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 8.1 ± 1.8 | 7.9 ± 2.3 | 8.87 ± 2.6 | 8.7 ± 2.7 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 72.8 ± 5.3 | *32.2 ± 10 | *32.5 ± 4.1 | *38.2 ± 3.2 | 56.9 ± 5.6 | 71.1 ± 4.6 | 84.1 ± 5 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 21 ± 3.2 | *65.2 ± 8 | *67.5 ± 5 | *52.1 ± 8 | 32 ± 12 | 23 ± 9 | 15 ± 2.9 |

| Monocytes (%) | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 1.7 | 6.4 ± 1.4 |

| HCT (%) | 40.8 ± 3 | 39 ± 3.4 | 35.5 ± 3.1 | 37.4 ± 2.2 | 38.4 ± 2.1 | 45.3 ± 2.6 | 39.8 ± 2.9 |

| PLT (1000/mm3) | 1172 ± 115 | 941 ± 120 | 954 ± 135 | 810 ± 118 | 1036 ± 211 | 827 ± 155 | 1266 ± 122 |

| ALT (U/L) | 1288 ± 125 | 1288 ± 115 | 956 ± 125 | 756 ± 125 | 768 ± 112 | 876 ± 102 | 987 ± 95 |

| AST (U/L) | 117 ± 15 | 130 ± 33 | 121 ± 25 | 144 ± 38 | 105 ± 27 | 122 ± 23 | 163 ± 36 |

| ALP (U/L) | 284 ± 34 | 246 ± 46 | 356 ± 57 | 344 ± 75 | 321 ± 45 | 356 ± 68 | 267 ± 44 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 64 ± 10 | 62 ± 12 | 63 ± 15 | 56 ± 8 | 56 ± 12 | 57 ± 11 | 58 ± 17 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.4 ± 0.05 | 0.3 ± 0.06 | 0.4 ± 0.07 | 0.3 ± 0.05 | 0.4 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| T.P (mg/dL) | 5.8 ± 1.2 | 5.6 ± 1.3 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 5.5 ± 1.4 | 4.7 ± 2.1 | 5.25 ± 1.6 | 6 ± 2.2 |

| Glu (mg/dL) | 195 ± 25 | 238 ± 33 | 243 ± 45 | 266 ± 48 | 274 ± 66 | 216 ± 44 | 248 ± 55 |

| B.T (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| B.Direct (mg/dL) | 0.39 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.46 ± 0.2 | 0.37 ± 0.1 | 0.46 ± 0.1 | 0.67 ± 0.2 | 0.25 ± 0.07 |

| Alb (mg/dL) | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

Values are means ± SD. RBC = red blood cell, HCT = hematocrit, WBC = white blood cells, Plt = platelets, BUN = blood urea nitrogen, Cr = creatinine, Glu = glucose, AST = aspartate transaminase, ALT = alanine transaminase, ALP = alkaline phosphatase, Alb = albumin, T.P = total protein, B.T = Bilirubin Total, B.Direct = Bilirubin Direct.

Table 3.

The hematological and biochemical parameters in the effects of 5 Gy gamma radiation on 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 30 days post-irradiation.

| Indexes | Control group | 5 Gy gamma-radiation group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day | 3 day | 7 day | 14 day | 21 day | 30 day | ||

| Body Weight (g) | 21.5 ± 2 | 19.7 ± 2.8 | *18.8 ± 2.4 | 19.8 ± 2.7 | 20.6 ± 2.2 | 21.6 ± 2.4 | 23 ± 2.1 |

| WBC (1000/mm3) | 6.8 ± 1.7 | *2.2 ± 0.4 | *0.98 ± 0.2 | *1.23 ± 0.5 | *2.9 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 2.5 | 8.9 ± 2.9 |

| RBC (Millin/mm3) | 9.3 ± 1.8 | 9.2 ± 2.1 | 8.5 ± 2.6 | 8.2 ± 2.5 | 8.4 ± 2.7 | 8.8 ± 2.2 | 9.3 ± 2.9 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 72.8 ± 5.3 | *22 ± 13 | *22.5 ± 8 | *28.2 ± 3.2 | *46 ± 9 | 65 ± 12 | 84 ± 8 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 21 ± 3.2 | *75.2 ± 15 | *77.5 ± 1.9 | *62.1 ± 2.8 | 52 ± 3.7 | 33 ± 2.3 | 11 ± 2.9 |

| Monocytes (%) | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 1.7 | 6.4 ± 1.4 |

| HCT (%) | 40.8 ± 2.5 | 38 ± 2.4 | 36.6 ± 3.7 | 38.3 ± 2.5 | 38.5 ± 2.8 | 43 ± 3.6 | 41 ± 3.9 |

| PLT (1000/mm3) | 1172 ± 115 | 1041 ± 131 | 934 ± 144 | 890 ± 145 | 1136 ± 260 | 954 ± 126 | 1111 ± 210 |

| ALT (U/L) | 1288 ± 125 | 1345 ± 123 | *1543 ± 200 | 885 ± 233 | 853 ± 156 | 888 ± 132 | 1109 ± 164 |

| AST (U/L) | 117 ± 15 | 125 ± 25 | *148 ± 28 | *142 ± 23 | 126 ± 33 | 120 ± 29 | 125 ± 33 |

| ALP (U/L) | 284 ± 34 | 255 ± 52 | *455 ± 44 | *434 ± 32 | 333 ± 64 | 312 ± 65 | 295 ± 52 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 64 ± 10 | 75 ± 15 | 70 ± 18 | 66 ± 15 | 60 ± 12 | 65 ± 14 | 65 ± 17 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.4 ± 0.05 | 0.7 ± 0.09 | 0.4 ± 0.05 | 0.5 ± 0.07 | 0.4 ± 0.08 | 0.4 ± 0.06 | 0.4 ± 0.08 |

| T.P (mg/dL) | 5.8 ± 1.2 | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 5 ± 1.5 | 4.9 ± 2 | 5 ± 1.5 | 5.4 ± 2.5 |

| Glu (mg/dL) | 195 ± 25 | 210 ± 33 | 225 ± 44 | 234 ± 50 | 220 ± 55 | 235 ± 48 | 240 ± 65 |

| B.T (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.75 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.85 ± 0.2 | 0.85 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.4 |

| B.Direct (mg/dL) | 0.39 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.55 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Alb (mg/dL) | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 1 | 2.4 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.9 |

Values are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group. Values are means ± SD. RBC = red blood cell, HCT = hematocrit, WBC = white blood cells, Plt = platelets, BUN = blood urea nitrogen, Cr = creatinine, Glu = glucose, AST = aspartate transaminase, ALT = alanine transaminase, ALP = alkaline phosphatase, Alb = albumin, T.P = total protein, B.T = Bilirubin Total, B.Direct = Bilirubin Direct.

Generally, a significant reducing trend in white blood cells (WBC) and lymphocyte numbers and also a significant increasing trend in neutrophil numbers have observed on 1, 3, 7, and 14 post-radiation days at 4 and 5 Gy doses in comparison with the control group (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 2 and 3). Moreover, a significant increase in the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels at 5 Gy dose has been shown on the 3rd and 7th days post-radiation compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 3). Besides, the alanine transaminase (ALT) had a significant increase rate just on the 3rd day post-radiation compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 3). It is noteworthy that no significant change in other biochemical parameters, including blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), total protein, glucose (Glu), Bilirubin Total, Bilirubin Direct, and Albumin, was shown (Tables 2 and 3).

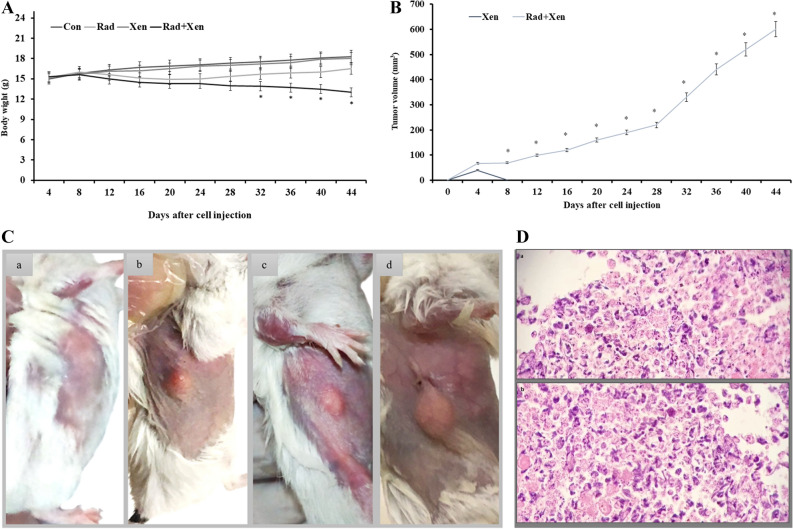

The breast tumor growth of the xenograft tissues

The breast carcinoma tumors in 6 BALB/c mice were monitored for several weeks (44 days). We evaluated the tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells by injecting 3 × 106 cells per mouse. A significant decrease in the animals’ weight was observed from the 33rd to 44th days after radiation in the Xen + Rad compared to the Xen alone group (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 1A). Two weeks after cell injection, the tumor size reached a volume of 100 mm3. There was a significant increase in tumor size after cell injection during 44 days (Fig. 1B,C).

Figure 1.

The macroscopic views of (A) the body weight, (B) the tumor volume, and (C) the tumor extension on days 10 (a), 20 (b), 30 (c), and 40 (d) after the gamma radiation in mice, and (D) the microscopic views of the xenograft breast tumor (× 20). Con: control, Xen: cell injection group, Rad: gamma radiation group, and Xen + Rad: gamma radiation plus cell injection group. Data were reported as mean ± SD. * P ≤ 0.05 compared to the Xen group.

The tumor light micrographs of stained Hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E) sections have been illustrated in Fig. 1D. Hyperchromatic nucleus cells and pleomorphism tumor cells have mainly been detected in the xenograft tumor regions. A number of the mitotic and proliferative cells were recognized in the tumor core areas. Moreover, the necrotic cells were mostly seen at the tumor margins. Accumulation of many tumor-inflammatory cells could activate an inflammation response into the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 1D).

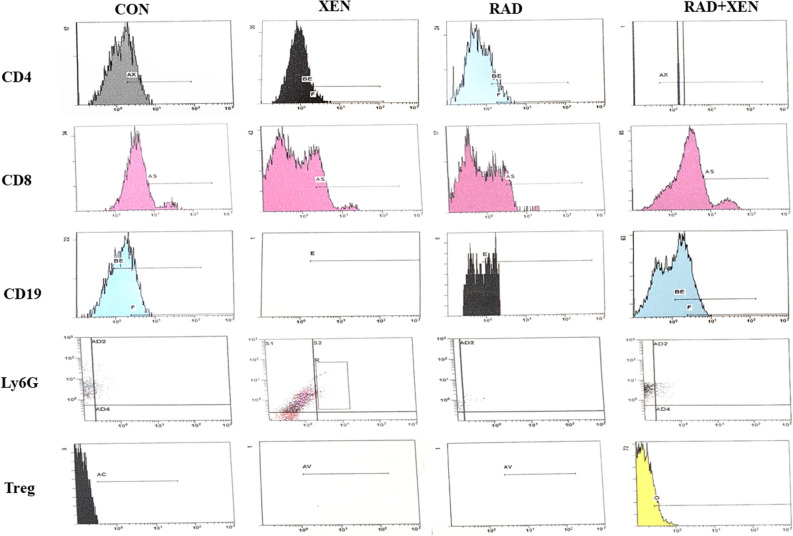

Flow cytometry (FC) results

The results of the flow cytometry have shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2. All numbers were calculated by counting lymphocytes between 5000 and 6000 cells. The spleen level of the CD4, CD8, CD19, Treg, and Ly6G has been compared in the Xen alone vs. the control group and the Xen + Rad group vs. the Xen alone. Except for Treg, the spleen level of CD4, CD8, CD19, and Ly6G was significantly increased in the Xen group compared to the control group on the 3rd day (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 2). Unlike the 3rd day, the spleen level of the CD4, CD8, CD19, Treg, and Ly6G was not meaningfully different between control and Xen groups on 7, 14, and 21 days. In contrast to Treg, the spleen level of CD4, CD8, CD19, and Ly6G was considerably decreased in the Xen + Rad than the Xen group on 3 and 7 days (P ≤ 0.05). However, their levels were not meaningfully different between Xen alone and Xen + Rad groups on 14 and 21 days after radiation.

Table 4.

Flow cytometry assay on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after gamma radiation.

| Markers | Days | Con | Xen | Rad | Rad + Xen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | 3 | 33.6 ± 4.4 | 38.6 ± 0.5 * | 14.0 ± 1.7 | 16.3 ± 1.7 # |

| 7 | 33.3 ± 4.2 | 32.5 ± 0.1 | 16.3 ± 1.7 | 19.2 ± 0.5 # | |

| 14 | 33.2 ± 4.1 | 33.2 ± 2.1 | 21.9 ± 2.2 | 28.1 ± 3.6 | |

| 21 | 33.3 ± 4.2 | 32.4 ± 3.8 | 28.2 ± 3.6 | 30.0 ± 2.7 | |

| CD8 | 3 | 16.9 ± 1.4 | 21.3 ± 2.7 * | 11.8 ± 1.7 | 13.2 ± 1.5 # |

| 7 | 16.6 ± 1.3 | 18.1 ± 1.7 | 13.2 ± 1.1 | 14.2 ± 0.7 # | |

| 14 | 16.7 ± 1.3 | 16.1 ± 2.2 | 18.5 ± 0.1 | 15.5 ± 2.7 | |

| 21 | 16.6 ± 1.2 | 16.2 ± 1.9 | 19.5 ± 0.1 | 17.2 ± 2 | |

| Treg | 3 | 7.7 ± 2.0 | 4.3 ± 1.2 * | 12.1 ± 1.9 | 12.0 ± 3 # |

| 7 | 7.8 ± 1.9 | 7.9 ± 2 | 10 ± 3.2 | 12.8 ± 1 # | |

| 14 | 7.6 ± 2.0 | 7.6 ± 2 | 7.9 ± 2.1 | 9.1 ± 1.2 | |

| 21 | 7.5 ± 2.1 | 7.5 ± 0.9 | 7.5 ± 1.1 | 8.5 ± 2 | |

| CD19 | 3 | 50.9 ± 2.6 | 58 ± 5* | 45.1 ± 5.5 | 46.1 ± 2.8 # |

| 7 | 50.6 ± 2.4 | 54.5 ± 5 | 47.0 ± 13 | 46.2 ± 4 # | |

| 14 | 50.5 ± 2.5 | 50.1 ± 5 | 48.9 ± 2.0 | 46.2 ± 2.7 | |

| 21 | 50.6 ± 2.6 | 50.2 ± 2 | 52.3 ± 5.9 | 48.3 ± 2.5 | |

| Ly6G | 3 | 6.6 ± 1 | 9.7 ± 2 * | 3.8 ± 1 | 4.2 ± 1.6 # |

| 7 | 6.3 ± 1 | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.9 # | |

| 14 | 6.4 ± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 1 | |

| 21 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 1.2 |

Con: control, Xen: cell injection group, Rad: gamma radiation group, and Xen + Rad: gamma radiation plus cell injection group.

* P ≤ 0.05 compared to the control group.

# P ≤ 0.05 compared to the Xen group.

Figure 2.

Representative plots of the CD4 + , CD8 + , Treg, CD19, and Ly6G in the spleen tissue on the 3rd day after gamma radiation in mice. The plots were only shown in one sample.

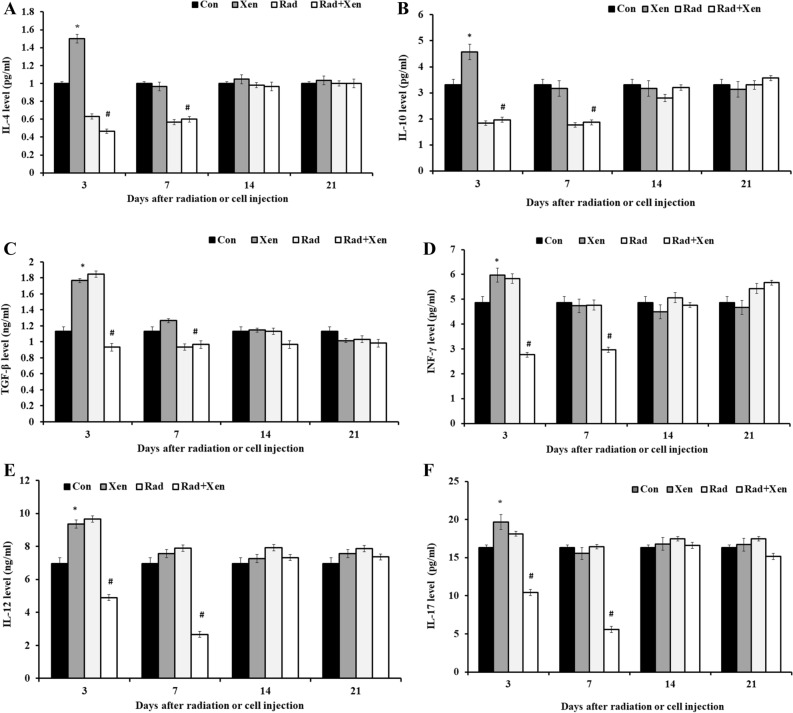

The cytokine assay

We used an ELISA method to assay the spleen level of anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-10, and the inflammatory cytokines, including TGF-β, INF-γ, IL-12, and IL-17, on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days post-radiation (Fig. 3). The spleen level of cytokines has been compared in the Xen alone vs. the control group and the Xen + Rad group vs. the Xen alone. The cytokine levels of the spleen, including IL-4 (Fig. 3A) and IL-10 (Fig. 3B), were significantly increased in the Xen alone group compared to the control group on the 3rd day (P ≤ 0.05). However, their levels were not meaningfully different between the control and Xen groups on 7, 14, and 21 days. The spleen level of IL-4 and IL-10 was considerably increased in the Xen + Rad than the Xen alone group on 3 and 7 days (P ≤ 0.05). However, their levels were not meaningfully different between the Xen alone and Xen + Rad groups on 14 and 21 days.

Figure 3.

The spleen levels of IL-4 (A), IL-10 (B), TGF-β (C), INF-γ (D), IL-12 (E), and IL-17 (F) on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after gamma radiation in mice. Con: control, Xen: cell injection group, Rad: gamma radiation group, and Xen + Rad: gamma radiation plus cell injection group. Data were reported as mean ± SD. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to the control group, #P ≤ 0.05 compared to the Xen group.

The cytokine levels of the spleen, including TGF-β (Fig. 3C), INF-γ (Fig. 3D), IL-12 (Fig. 3E), and IL-17 (Fig. 3F), were significantly increased in the Xen alone group compared to the control group on the 3rd day (P ≤ 0.05). However, their levels were not meaningfully different between the Xen alone and control groups on 7, 14, and 21 days. The spleen's cytokine levels, including TGF-β, INF-γ, IL-12, and IL-17, were dramatically decreased in the Xen + Rad group compared to the Xen alone group on 3 and 7 days (P ≤ 0.05). However, their levels were not meaningfully different between the Xen + Rad and Xen alone groups at 14 and 21 days after radiation.

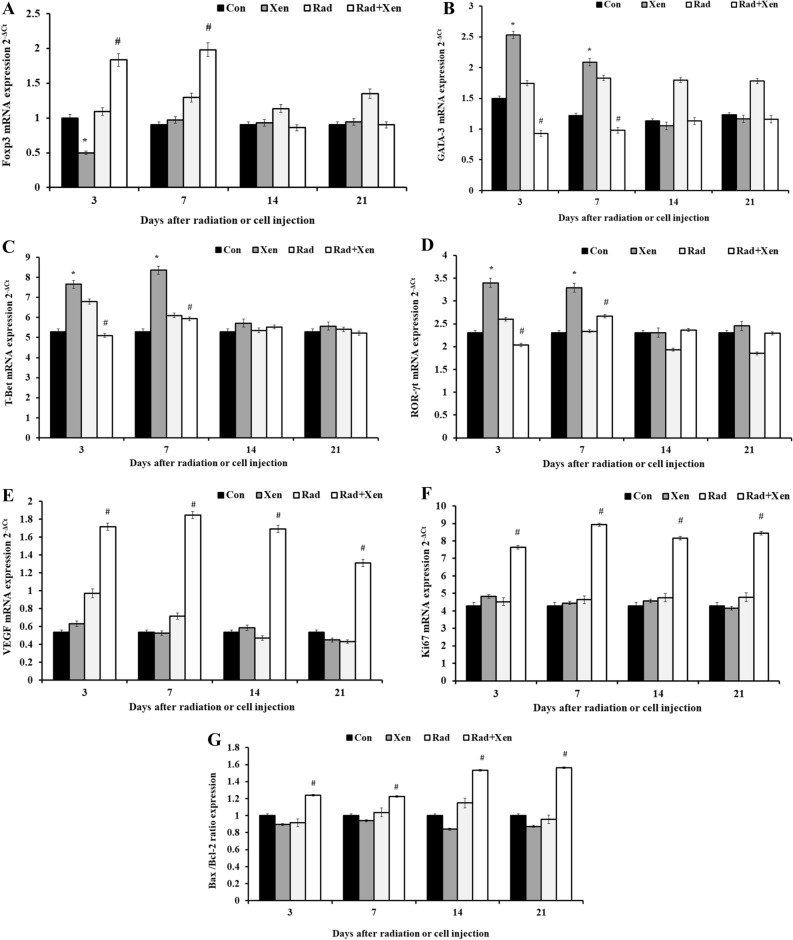

The results of the gene expression

The expression level of genes, including GATA-3, T-Bet, ROR-γt, VEGF, Foxp3, Ki67, Bax, and Bcl-2, was determined by the quantitative real-time PCR on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days post-radiation or cell injection (Fig. 4A–G). The mRNA’s spleen expression has been compared in the Xen alone vs. the control group and the Xen + Rad group vs. the Xen alone. The spleen expression of the Foxp3 (Fig. 4A) was significantly decreased in the Xen group compared to the control group on the 3rd day after cell injection (P ≤ 0.05). Unlike the 3rd day, its expression level was not meaningfully different between the control and Xen alone groups on 7, 14, and 21 days. The spleen expression of Foxp3 was considerably increased in the Xen + Rad group compared to the Xen alone group on 3 and 7 days (P ≤ 0.05). However, its expression level was not noticeable between the Xen + Rad and Xen alone groups at 14 and 21 days (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

The spleen expression of Foxp3 (A), GATA-3 (B), T-Bet (C), and ROR-γt (D), VEGF (E), Ki67 (F), and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (G) on days 1, 3, 7, and 14 after gamma radiation in BALB/c mice. Con: control, Xen: cell injection group, Rad: gamma radiation group, and Xen + Rad: gamma radiation plus cell injection group. Data were reported as mean ± SD. *P ≤ 0.05 compared to the control group, #P ≤ 0.05 compared to the Xen group.

The spleen expression of the GATA-3 (Fig. 4B), T-Bet (Fig. 4C), and ROR-γt (Fig. 4D) was significantly increased in the Xen alone group compared to the control group on the 3rd and 7th days after cell injection (P ≤ 0.05). However, their expression level was not pointedly different between the control and Xen alone groups on 14 and 21 days. Moreover, these genes' expression levels were considerably decreased in the Xen + Rad group compared to the Xen alone on the 3rd and 7th days (P ≤ 0.05). However, their expression level was not significantly different between the Xen + Rad and Xen alone groups on the 14th and 21st days (Fig. 4B-4D).

The spleen expression level of the VEGF (Fig. 4E), Ki67 (Fig. 4F), and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (Fig. 4G) was not significantly different between the control and Xen groups on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days. However, their expression levels were considerably increased in the Xen + Rad group compared to the Xen alone group on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days (P ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

The present study has been aimed to establish GIS mice as a new kind of human xenograft tumors for in vivo biomedical studies. So, the tumorigenicity potential of GIS mice and their immunological responses against the xenograft tissues were evaluated within three separate phases. The results of the first phase have proved that the whole-body gamma radiation in all 3, 4, and 5 Gy doses had a high immunosuppressive effect on mice from 1 to 14 days post-radiation. In contrast to 5 Gry, the animals in 3 or 4 Gy doses gamma radiation did not show any significant toxicity. Hence, the 4 Gy dose has been chosen as the maximum effective and safe dose of gamma radiation. The subcutaneous injection of 3 × 106 MCF-7 cells in the second phase of the present study has shown significant tumor formation and growth efficiency. The macroscopic and histopathological observations have proved the breast tumor structure. Identification of the pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines has confirmed a substantial suppression of the rejection-involved xenograft immune cells and an increase of the T-reg cells in the xenotransplanted GIS mice. The VEGF, Ki67, and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio have shown an increased expression rate in the splenocyte tissues of GIS mice. These data can confirm a new xenograft model via an efficient immune-suppressive potential of the whole-body gamma radiation in mice.

Within days after cell injection, the cellular xenograft rejection (CXR) is recognized as a primary barrier for the xenograft cell injection approaches14. The immune cells, including macrophages, lymphocytes, NK cells, and T-helpers, are introduced as the central-involved cells in the CXR12,14–17. In the way of CXR, the T-lymphocytes and the macrophages are the first responders against the xenograft cell injection. Here, there is a crosslink between the macrophages and T-lymphocytes, specifically CD4 + and CD8 + 15,16,18,19. Xenoreactive macrophages by the secretion of some pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1, can promote the injected cell death20–22. On the other hand, the numerous immunological alarms for the activation and recruitment of the different immune effector cells are produced by secreting some specific cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-12, and IL-17, and macrophage-activated CD4 + and CD8 + lymphocytes12,23–25. Under the stimulation with INF-γ and IL-17, T-helpers can also induce xenograft cell rejection through the production and secretion of the cytokines24, such as IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and IL-1316,26.

Through some observations, it has been proved that splenocytes, particularly T-helpers, are affected by the gamma radiation26,27. Similar to our results, Kajioka et al. (1999) have evaluated the responses of CD19 + B cells, CD4 + , and CD8 + lymphocytes against the whole-body radiation on the 3 Gry gamma-radiated mice. Their observations showed significantly less change in the rate of CD19 + B cells and CD4 + and CD8 + lymphocytes in the gamma-radiated mice28. Likewise, a more radiosensitive from CD19 + B cells was observed compared to CD4 + and CD8 + lymphocytes29. Moreover, Han et al. (2006) have shown that the cytokine network of splenocytes is affected by 5 Gy gamma radiation30. Similar to our observations, they detected a significantly decreased rate of the IFN-γ mRNA after radiation30. Consonant with GATA-3 gene expression, we showed a substantial reduction in the rate of the pro-inflammatory IL-4 and INF-γ cytokines in the radiated mice. However, our results have shown a reverse fact about GATA-3 gene expression and the spleen levels of IL-4, IL-10, and IL-12. Inconsistency in the consequences might be due to differences in the administrated radiation method.

It has been recognized that the T-reg cells have a determinative role in xenograft cell-injected tolerance26. The T-reg cells, via the expression of IL-10 and TGF-β, can actively protect xenotransplanted cells within immune system responses29,31. Consonant with the Foxp3 up-regulation, we have here shown a significant increase in the rate of IL-17. It seems that the Foxp3, as a ‘master switch’ gene for the Treg cells, has a vital role in the immunosuppressive activity31. In a TGF-β-dependent manner, the T-reg cells can actively inhibit the NK cells and decline their cytotoxicity and anti-graft activity32. Our results have clearly shown that the T-reg cells are one of the primary targets of gamma radiation. Undertaken a 4 Gy the whole-body gamma radiation, our data illustrated a significant increase in the T-reg cells' numbers. Moreover, a substantial increase in the expression of the Foxp3 and TGF-β related to gamma exposure was detected. In this respect, T-reg cells have shown a high resistance from the gamma radiation compared to the other T lymphocytes in the study of QU et al. (2010)9. They proved that the rate of two CD4 + CD25 high Foxp3 + and CD4 + CD25 high types of the T-reg cells could significantly raise in the lymph nodes, spleens, thymuses, and the blood samples after gamma radiation9. Likewise, our study highlighted that by enhancing T-reg cells' rate and activity after radiation, the Ly6G, INF-γ, and in turn, NK cells had significantly reduced. These results strangely support our hypothesis that the GIS mice can be a new well-tolerated animal for xenotransplantation studies by suppressing immune responses and improving anti-inflammatory and inflammatory networks in the xenotransplanted cells.

Additionally, death and infection have not been seen during our study for some reason:

A: Using the safe dosages of the gamma radiation.

B: The activity of the GIS mouse's innate immune system during the study.

C: Complete improvement of the immune system three weeks after cell injection.

Surprisingly, all the gamma-radiated animals have completely survived into the ordinary and unclean animal room. Thus, the features mentioned above can be crucial in developing GIS mice for a wide range of biomedical cancer studies. With the different types of immune-deficient animals, selecting a suitable and sufficient xenograft animal model to advance the experimental studies can be introduced as the primary step for designing in in vivo cancer studies. The remarkable xenograft growth in the GIS mice refers to a high potential for applying this model to generate the different types of xenograft mice models. Based on our observation, the MCF7 xenograft tumor volume was at a suitable level (> 90 mm3) to manage and start in vivo cancer studies. Therefore, the breast-tumor growth evaluation until 44 days post-injection has shown that the xenograft tumor proliferation was developed with a higher speed in the GIS mice. On the contrary, the development of the MCF7 cells in the nude mice was established by implanting the 5 × 106 cells for 35 days at the best possible33. With a brief look at the high cost and complexity of creating the conventional xenograft models and applying them to cancer immunotherapy studies, it can be suggested our model may remove all the economic and technical berries in the field of cancer immunotherapy studies.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that an increase in the immune system's tolerance against the xenograft tumor could raise the chance of the survival and growth of the MCF7 cells into the GIS mice. Increasing the immune cells' level and function and the related cytokines' activity may activate the mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory and anti-xenograft rejections. We can claim that the new tumor xenograft model can manage the xenograft tumor growth by increasing immune system tolerance and suppressing its mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Materials

MCF-7 cells were purchased from the Pasture Institute of Iran (Tehran, Iran). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Life Technologies Co. (Gibco Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Ketamine and xylazine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). The Cobalt-60 facility was provided by the Cancer Institute of Imam Khomeini hospital Complex of Iran (Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran). Mouse monoclonal antibodies of anti-CD19, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8 were purchased from Abcam CO. INF-γ Mouse ELISA Kit (Abcam; ab46081), IL-4 Mouse ELISA Kit (Abcam; ab100710), and IL-17 Mouse ELISA Kit (Abcam; ab100702) were used for IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 serum level assessment. Total RNA was isolated with a Total RNA extraction kit (GRM1002, VIOGENE, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Template cDNAs were synthesized using SuperScript III (18080-051, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with a quantitative PCR mix (QPK-201T, Toyobo, Osaka, Honshu, Japan) using a real-time PCR detection system (CFX96; Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Animals

Animals were housed in pens exceeding the stipulated size requirements. All inbred female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks) were maintained in large group houses under 12-h dark and light cycles and were given access to food and water ad libitum.

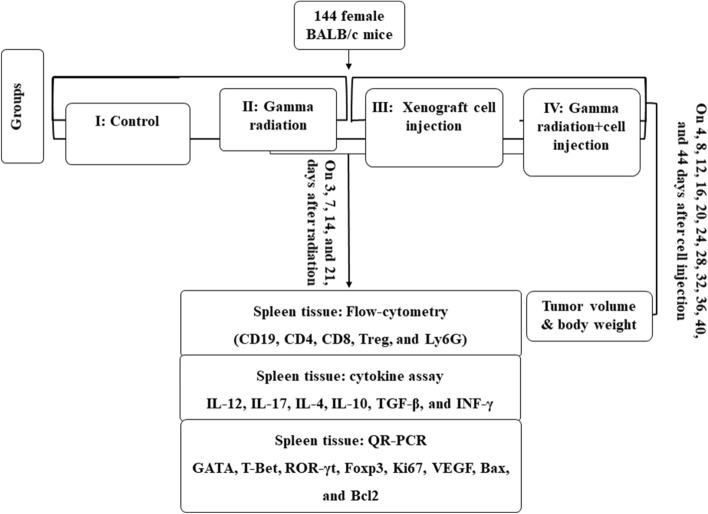

The study design

The present study was designed in three separate phases. First, 144 BALB/c mice were used to find an optimum dose of gamma radiation with maximum efficiency to suppress the immune system. Second, 144 female BALB/c mice were used to study the growth of the xenograft breast tumor, and at last, the immune system's behavior on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after cell injection in the gamma-radiated BALB/c mice34.

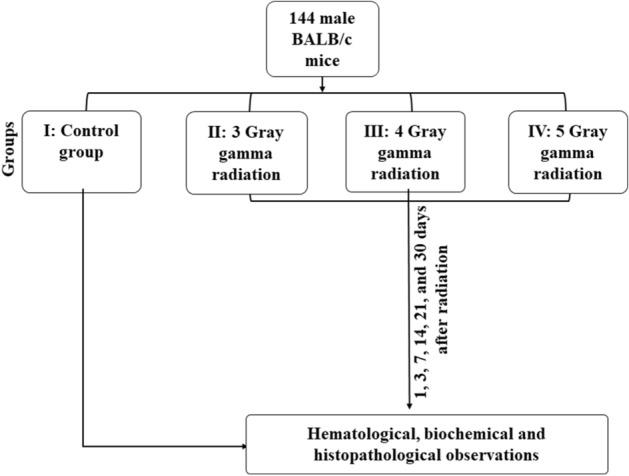

The dosing procedure of the gamma radiation

One hundred forty-four BALB/c mice have equally divided into four groups, including (I) the health animals without any intervention (N = 36), (II) the gamma radiation with 3 Gy (N = 36), (III) the gamma radiation with 4 Gy (N = 36), and (IV) the gamma radiation with 5 Gy (N = 36). Animals in groups 2 to 4 have received the whole-body gamma radiation by Cobalt-60 at 3, 4, and 5 Gy doses, respectively. All animals were weighed before and after radiation at days 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 30. Immediately following each weighing, six mice were sacrificed, and the blood samples were taken for the hematological and blood biochemical analyses35 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic design of the dosing procedure of the gamma radiation.

The whole-body gamma radiation

The cobalt-60 facility at the doses of 3, 4, and 5 Gy was used for radiation (Cancer Institute of Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran). Animals were intraperitoneally anesthetized by a mixture of Xylazine and Ketamine (110 mg/kg). The animals were exposed to 3, 4, and 5 Gy of whole-body gamma radiation using a Cobalt 60 machine, producing two gamma rays with energies of 1.17 and 1.33 meV (Theratron 780; Phoenix Company, Ottawa, Canada). The animals were placed in the center of the 30 × 30 cm2 field size and 80 cm from the irradiator so that the beam was homogenized34.

Hematology and blood biochemistry assays

Blood samples were taken at 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 30 days after radiation under general anesthesia. The hematological and biochemical parameters were measured by using an animal blood counter (Celltac; Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan), a CCX System (CCX WB; Nova Biomedical, USA), and an Autoanalyser System (Autoanalyser Model Biotecnica, BT 3500, Rome, Italy)36.

The development of the xenograft breast tumor

We examined the human xenograft's breast tumor growth potential and studied the immune system’s behavior against the xenograft tissues in the GIS mice. One hundred forty-four female mice have equally been divided into four groups. (I) The control, the healthy mice without any intervention. (II) The cell implantation (Xen), the animals have subcutaneously received 3 × 106 MCF-7 breast cancer cells. (III) The gamma radiation (Rad), the animals were radiated by Cobalt-60 (4 Gy). (IV) The gamma radiation plus the cell injection (Xen + Rad), the animals were radiated by Cobalt-60 (4 Gy) and subcutaneously received 3 × 106 MCF-7 cells 24 h post-radiation. The animals in II and III groups were re-radiated (2 Gy) 9 days after cell injection. All animals were weighed once every three days after radiation, and six mice were sacrificed at 3, 7, 14, and 21 post-radiation, and the blood and spleen samples were taken for more assessments (Fig. 6)36.

Figure 6.

Schematic design to develop gamma-irradiated immunosuppressed mice.

The cell culture

Human breast MCF-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin mixture. The cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C (Sanyo CO2 Incubator; Sanyo, Kitanagoya, Aichi)37.

Cell injection and tumorigenicity

The cultured cells were trypsinized and resuspended in a tenfold excess culture medium. The cells were then resuspended in PBS, and 3 × 106 cells were injected (0.1 ml, s.c) using a 21-gauge needle in the right flank of mice 24 h after radiation under ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) anesthesia37.

Tumor volume measuring

Animals were weighted weakly by using a digital scale, and the tumor volume was measured every four days by a Digital Vernier Caliper (Mitutoyo, Japan) through the following formula34,36.

V = 1/6 (π L W D), where V = volume, L = Length, W = Width, and D = Depth.

The histopathological observations

The tumors were fixed and preserved in 10% buffered formaldehyde for at least 24 h, then passaged and embedded in the paraffin, then sectioned by 3–5 μm thickness for hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining. The slides were studied at the microscopic level (OLYMPUS-BX51 microscope) and then graded by the Scharff-Bloom- Richardson Scale38,39.

Flow cytometry assay

The flow cytometry was used on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days post-radiation in each group. Spleens were crushed in a 40-µm nylon strainer. Single-cell suspensions were treated with Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium (ACK) lysis buffer (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) to lyse red blood cells and washed in PBS that contained 10% FBS. Splenocytes were then treated with FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and GolgiStop (Protein Transport Inhibitor, Becton Dickinson, Franklin, NJ) to inhibit protein secretion. Cell surface markers were immunolabeled with F4/80 (Anti-F4/80 PE, Miltenyi Biotec), CD11c (CD11c-PE, Miltenyi Biotec), or CD115 (CD115-PE, Miltenyi Biotec), washed, and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. The cells were resuspended and stained for 15 min on ice with anti-mice CD19 (B cells), CD4 (T helper cells), CD8 (Cytotoxic T cells), Ly6G (neutrophil cells), and CD4/CD8 conjugated monoclonal antibodies. FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton–Dickinson, CA) system used for percentage of the CD19 + , CD4 + , CD8 + , and CD4 + /CD8 + cell detection40.

ELISA assay

The IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 levels of the spleen at 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after cell injection were measured using ELISA kits under the manufacturer’s instructions. The diluent buffer was used as a negative control. After incubation, 100 µl of biotin antibody was added to each well and incubated for one h at 37 °C. Then, horseradish peroxidase–avidin (100 µl) was added to each well for one h at 37 °C. At last, 90 µl of the supplied chromogen was added and incubated for 30 min in the dark at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped with 50 µl of the Supplied Stop Solution, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a spectrophotometer41.

Quantitative real-time PCR

The mRNA expression of the GATA-3, T-Bet, ROR-γt, VEGF, Foxp3, Ki67, Bax, and Bcl2 genes on 3, 7, 14, and 21 days post-radiation was assayed by Real-Time quantitative PCR. First, total RNA was extracted from the spleens using TRIzols reagent (Life Technologies), followed by the DNase I digestion (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Complementary DNA was synthesized by the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Fermentas, Germany). The list of primers, including GATA-3, T-Bet, ROR-γt, VEGF, Foxp3, Ki67, Bax, Bcl2, and GAPDH, have been indicated in Table 5. Real-time PCR was performed using the SYBRs Premix Ex Taq II (Takara). Relative gene expression was calculated as 2-ΔΔCt41.

Table 5.

The list of the primers’ sequences.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| GATA3 | GGGGCCTCTGTCCGTTTAC | TCCAGCTTCATGCTATCTGGC |

| T-bet | AGCAAGGACGGCGAATGTT | GTGGACATATAAGCGGTTCCC |

| Foxp3 | CACCTATGCCACCCTTATCCG | CATGCGAGTAAACCAATGGTAGA |

| RORγt | CGCGGAGCAGACACACTTA | CCCTGGACCTCTGTTTTGGC |

| Ki67 | CGCAGGAAGACTCGCAGTTT | CTGAATCTGCTAATGTCGCCAA |

| Bax | GATGATTGCTGACGTGGAC | ACGGAGGAAGTCCAGTGTC |

| Bcl2 | CTGCACCTGACGCCCTTCACC | CACATGACCCCACCGAACTCAAAGA |

| GAPDH | AGGCCGGTGCTGAGTATGTCGTG | TCACAAACATGGGGGCATCGG |

Data analysis

Data analysis was done using SPSS statistical software version 18. Fisher's exact test was used to analyze differences in % of animals with breast tumors. Tukey's post hoc and analysis of variance (ANOVA) assessments were used for comparison among groups. Data were represented as mean ± S.D. P-value < 0.05 considered being statistically significant.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were conducted within the international guidelines of the Weatherall report and also the national guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences has approved the project under the tenses of the Helsinki Declaration and the national ethical guideline for medical research (IR.TUMS.REC.1394.1391).

Acknowledgments

This study was co-funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (grant number: 29383) and Kashan University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 12342).

Author contributions

H.K., S.K., and S.K.: study conception and sample processing. A.T., M.T., A.P.: data analysis and sample processing. H.N., G.A.H., and H.N.: sample processing. M.R.K.: sample collection and sample.

Funding

None of the funding sources had any role in study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46583-1

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hamid Khodayari and Saeed Khodayari.

Change history

11/15/2023

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: 10.1038/s41598-023-46583-1

References

- 1.Cook N, Jodrell DI, Tuveson DA. Predictive in vivo animal models and translation to clinical trials. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irigaray P, Belpomme D. Basic properties and molecular mechanisms of exogenous chemical carcinogens. Carcinogenesis. 2009;31:135–148. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemp CJ. Animal models of chemical carcinogenesis: driving breakthroughs in cancer research for 100 years. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2015;10:865–874. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top069906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson B, Li Y, Lin Y, Liu ET, Patnaik A. Mouse models for cancer immunotherapy research. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1358–1365. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frese KK, Tuveson DA. Maximizing mouse cancer models. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:654–658. doi: 10.1038/nrc2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higuchi M, et al. Expression of a conditional AML1-ETO oncogene bypasses embryonic lethality and establishes a murine model of human t (8; 21) acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell A, Hersey P, MacLennan I, Kay H, Pike M. The Medical Research Council’s Working Party on Leukemia in Childhood: Immunosuppressive consequences of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Br. Med. J. 1973;2:385–388. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5863.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuda S, Koyasu S. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine. Immunopharmacology. 2000;47:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qu Y, et al. Gamma-ray resistance of regulatory CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T cells in mice. Radiat. Res. 2010;173:148–157. doi: 10.1667/RR0978.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han S-K, Song J-Y, Yun Y-S, Yi S-Y. Gamma irradiation-reduced IFN-gamma expression, STAT1 signals, and cell-mediated immunity. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;35:583–589. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baranov A, et al. Bone marrow transplantation after the Chernobyl nuclear accident. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;321:205–212. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907273210401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin ML, et al. NK cells promote peritoneal xenograft rejection through an IFN-γ-dependent mechanism. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:536–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quezada SA, et al. Tumor-reactive CD4+ T cells develop cytotoxic activity and eradicate large established melanoma after transfer into lymphopenic hosts. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu A, Yamada K. Pathology of renal xenograft rejection in pig to non-human primate transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2006;20:46–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallgren AC, Karlsson-Parra A, Korsgren O. The main infiltrating cell in xenograft rejection is a CD4+ macrophage and not a T lymphocyte. Transplantation. 1995;60:594–601. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199509270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scalea J, Hanecamp I, Robson SC, Yamada K. T-cell-mediated immunological barriers to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2011.00687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itescu S, et al. Role of natural killer cells, macrophages, and accessory molecule interactions in the rejection of pig-to-primate xenografts beyond the hyperacute period. Hum. Immunol. 1998;59:275–286. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(98)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meier RP, et al. Xenotransplantation: back to the future? Transpl. Int. 2018;31:465–477. doi: 10.1111/tri.13104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dujovny N, et al. Acute xenograft rejection mediated by antibodies produced independently of TH1/TH2 cytokine profiles. Am. J. Transplant. 2002;2:526–534. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Ouaghlidi A, et al. Cytokine mRNA expression in peripheral blood cells of immunosuppressed human islet transplant recipients. J. Mol. Med. 1999;77:115–117. doi: 10.1007/s001090050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steeve KT, Marc P, Sandrine T, Dominique H, Yannick F. IL-6, RANKL, TNF-alpha/IL-1: interrelations in bone resorption pathophysiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parameswaran N, Patial S. Tumor necrosis factor-α signaling in macrophages. Crit. Rev. Eukaryotic Gene Expr. 2010;20:87–103. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v20.i2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szabo SJ, et al. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-γ production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang HK, et al. Differential role of B cells and IL-17 versus IFN-γ during early and late rejection of pig islet xenografts in mice. Transplantation. 2017;101:1801–1810. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonomura N, et al. Pig islet xenograft rejection in a mouse model with an established human immune system. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang S, Lechler RI, He X-S, Huang J-F. Regulatory T cells and transplantation tolerance. Hum. Immunol. 2006;67:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrington N, Chambers K, Ross W, Filion L. Radiation damage and immune suppression in splenic mononuclear cell populations. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1997;107:417–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1997.272-ce1158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beauford SS, Kumari A, Garnett-Benson C. Ionizing radiation modulates the phenotype and function of human CD4+ induced regulatory T cells. BMC Immunol. 2020;21:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12865-020-00349-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porter CM, Bloom ET. Human CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress anti-porcine xenogeneic responses. Am. J. Transplant. 2005;5:2052–2057. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han S-K, Song J-Y, Yun Y-S, Yi S-Y. Effect of gamma radiation on cytokine expression and cytokine-receptor mediated STAT activation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2006;82:686–697. doi: 10.1080/09553000600930699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorantla VS, et al. T regulatory cells and transplantation tolerance. Transplant. Rev. 2010;24:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghiringhelli F, et al. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells inhibit natural killer cell functions in a transforming growth factor-β-dependent manner. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1075–1085. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arteaga CL, Holt JT. Tissue-targeted antisense c-fos retroviral vector inhibits established breast cancer xenografts in nude mice. Can. Res. 1996;56:1098–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khalighfard S, et al. Evaluation of the treatment strategies on patient-derived xenograft mice of human breast tumor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020;889:173605. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohsenikia M, et al. Therapeutic effects of dendrosomal solanine on a metastatic breast tumor. Life Sci. 2016;148:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kavosi A, et al. The toxicity and therapeutic effects of single-and multi-wall carbon nanotubes on mice breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:8375. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26790-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37.Soleymani M, et al. Effects of multiple injections on the efficacy and cytotoxicity of folate-targeted magnetite nanoparticles as theranostic agents for MRI detection and magnetic hyperthermia therapy of tumor cells. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58605-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amat S, et al. Scarff-Bloom-Richardson (SBR) grading: a pleiotropic marker of chemosensitivity in invasive ductal breast carcinomas treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int. J. Oncol. 2002;20:791–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alizadeh AM, et al. Chemoprotection of MNNG-initiated gastric cancer in rats using Iranian propolis. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2015;18:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taheri RA, et al. The effect of lipopolysaccharide on the expression level of immunomodulatory and immunostimulatory factors of human amniotic epithelial cells. BMC Res. Notes. 2018;11:343. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3411-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alizadeh AM, et al. Oxytocin mediates the beneficial effects of the exercise training on breast cancer. Exp. Physiol. 2018;103:222–235. doi: 10.1113/EP086463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]