Abstract

Conventional methods employed today for the synthesis of amides often lack of economic and environmental sustainability. Triazine-derived quaternary ammonium salts, e.g., 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM(Cl)), emerged as promising dehydro-condensation agents for amide synthesis, although suffering of limited stability and high costs. In the present work, a simple protocol for the synthesis of amides mediated by 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT) and a tert-amine has been described and data are compared to DMTMM(Cl) and other CDMT-derived quaternary ammonium salts (DMT-Ams(X), X: Cl− or ClO4−). Different tert-amines (Ams) were tested for the synthesis of various DMT-Ams(Cl), but only DMTMM(Cl) could be isolated and employed for dehydro-condensation reactions, while all CDMT/tert-amine systems tested were efficient as dehydro-condensation agents. Interestingly, in best reaction conditions, CDMT and 1,4-dimethylpiperazine gave N-phenethyl benzamide in 93% yield in 15 min, with up to half the amount of tert-amine consumption. The efficiency of CDMT/tert-amine was further compared to more stable triazine quaternary ammonium salts having a perchlorate counter anion (DMT-Ams(ClO4)). Overall CDMT/tert-amine systems appear to be a viable and more economical alternative to most dehydro-condensation agents employed today.

Keywords: CDMT, triazines, amide synthesis, sustainable dehydro-condensation agents

1. Introduction

The synthesis of amides is among the most important reactions in organic chemistry and biochemistry because of the widespread occurrence of amides in pharmaceuticals, peptides, biologically active compounds, industrial polymers, detergents, and lubricants [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Consequently, many different physical [7] and chemical protocols have been developed for the synthesis of amides by dehydro-condensation of a carboxylic acid and an amine [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Catalytic routes for the preparation of amides have also been reported with the intent to increase atom efficiency of the process [2,14]. An alternative metal-free synthetic route for the formation of amides has been recently proposed by Zhang et al. [15] by coupling reaction of formamide with different carboxylic acids.

Albeit the strategic importance of this class of compounds, most methods commonly employed for the synthesis of amides still lack both in economic and environmental sustainability, have low atom efficiency, generate large quantities of hazardous waste products, and require complicated purification steps [16,17,18].

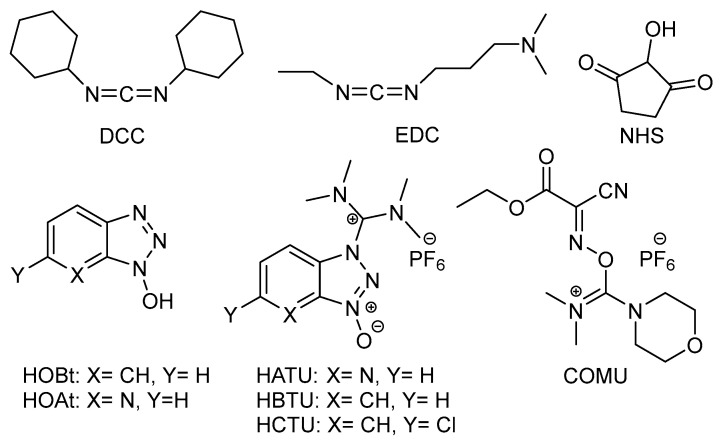

In this frame, dehydro-condensation reactions are a well-known and consolidated protocol for the synthesis of amides, although toxic dehydro-condensation agents are often used to promote the reaction [17,19]. For example, carbodiimides such as dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) or 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide chlorohydrate (EDC) employed in combination with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), have frequently been employed for the scope (Figure 1) [20,21,22,23].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of various dehydro-condensation agents.

Hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) [24,25,26], 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole (HOAt) [27,28,29], and uronium or guanidinium salt derivatives such as, e.g., hexafluorophosphate azabenzotriazole tetramethyl uronium (HATU), hexafluorophosphate benzotriazole tetramethyl uronium (HBTU), hexafluorophosphate chlorobenzotriazole tetramethyl uronium (HCTU), and 1-cyano-2-ethoxy-2-oxoethylidenaminooxy)-dimethylamino-morpholino-carbenium hexafluorophosphate (COMU) (Figure 1) have also been efficiently used to promote carbodiimide-mediated peptide coupling reactions [18,30], although with scarce environmental and economic sustainability [9,10,31]. In fact, DCC and EDC lead to the formation of toxic by-products [17], while uronium derivatives may contain highly harmful hydrazide impurities [19].

More stringent rules regulating the use and disposal of organic solvents and increasingly restrictive EU directives on hazardous substances make the quest for greener and more efficient products and processes increasingly important [17,18].

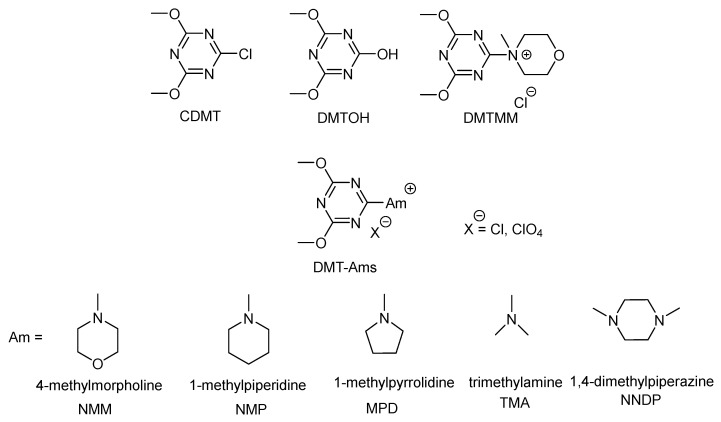

In this prospective, quaternary ammonium salts of 2-halo-4,6-dialkoxy-1,3,5-triazines, e.g., 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM(Cl)), (see Figure 2), represent a valid alternative for the formation of amide bonds both in organic and water solvent [20,21,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. In the last years, DMTMM(Cl), commonly known as DMTMM, has found many applications as dehydro-condensation agent for the synthesis of amides and esters [36,40], collagen cross-linking [7,21,38], preparation of carboxymethylcellulose based films [39], amine grafting on hyaluronan [20,40,41], and peptide synthesis [42]. Additionally, the synthesis of a library of 2-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazinyl)trialkyl ammonium salts (DMT-Ams(X), X: Cl− or ClO4−) and their activity as dehydro-condensation agents for the synthesis of amides, has been reported by Kunishima et al. [43] (Figure 2). This work is a milestone in the understanding of triazine based-condensation agents and their application in various fields of chemistry. Further interesting feature is that DMTMM and DMT-Ams(X) all degrade forming 2,4-dimethoxy-6-hydroxy-1,3,5-triazine (DMTOH) and the corresponding tertiary amine hydrochloric salt, which are nontoxic. Moreover, DMTOH can be recovered and recycled to produce 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT) or DMTMM (Figure 2) [37]. To date, one of the main limitations to large-scale use of DMTMM and DMT-Ams(X) remains their reduced stability in solution [43,44].

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT), 2,4-dimethoxy-6-hydroxy-1,3,5-triazine (DMTOH), 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM) and 2-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazinyl)trialkyl ammonium salts (DMT-Ams).

All this in mind, we believe that the use of isolated triazine quaternary ammonium salts could be overcome by direct addition of a 2-halo-4,6-dialkoxy-1,3,5-triazine and a tert-amine in the reaction mixture. This straightforward methodology would avoid the synthesis of isolated DMT-Ams(X), reduce production complexity, and solvent use and allow to achieve a library of dehydro-condensation agents, modulated according to specific requirements. Nowadays, a few data are available on dehydro-condensation reactions carried out with similar protocols [43,45] and often referring to very specific substrates in rather limited reaction conditions [46,47,48,49,50]. Only recently, Kitamura [34] and Kunishima [35] reported a similar protocol for amide condensation reactions, albeit in the presence of amido- or imido-chlorotriazines. To the best of our knowledge, no in-depth study has been reported on the advantages derived from the use of different CDMT/tert-amine systems compared to isolated DMT-Ams(X).

Our research group has long been involved in the study of innovative sustainable processes for fine chemistry [51,52,53,54]. Recently, our studies have focused on the development of new dehydro-condensation agents. Therefore, in this work we wish to report a systematic comparison between the efficiency of CDMT/tert-amine systems and isolated DMT-Ams(X) for the synthesis of amides.

Moreover, the possible advantages derived from the use of CDMT/tert-amine systems were also analyzed.

2. Results and Discussion

The activity of CDMT/tert-amine systems for dehydro-condensation reactions has been compared with the activity of the corresponding isolated DMT-Ams(X). DMT-Ams(X) have been synthesized according to the standard protocol reported in the literature [43,55,56,57]. For example, DMTMM was prepared by reaction of one equivalent of 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT) and 1.2 equivalents of N-methyl morpholine (NMM) in THF at room temperature for 1 h. After work up, DMTMM was recovered in 85–88% yield.

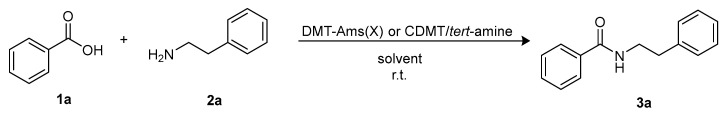

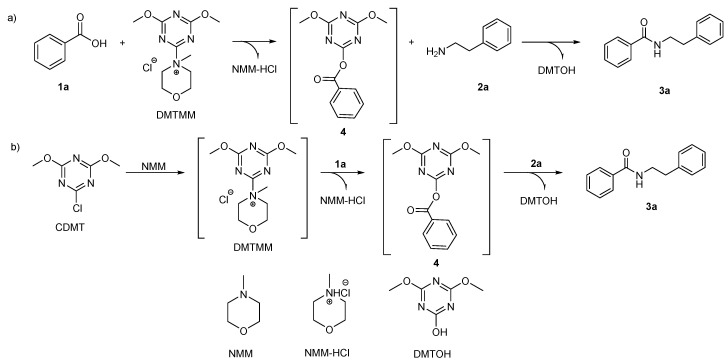

In the present work, the CDMT/tert-amine protocol foresees dissolution of 1.3 mmoles of an acid (e.g., 1a) in the reaction solvent, followed by addition (within a few seconds) of 1.3 mmoles of CDMT, 1.3 mmoles of a tert-amine, and 1.2 mmoles of an amine (e.g., 2a) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Dehydro-condensation reaction for the synthesis of amide 3a.

The yield in amide 3a was monitored by GLC after 15 min and 1 h (see e.g., entry 1 of Table 1). For a set of preliminary experiments, the reaction mixture was monitored by GLC also after 24 h; since no significant difference was observed between the yield in amide 3a after 1 and 24 h, unless otherwise stated, all further reactions were monitored within 1 h.

Table 1.

Dehydro-condensation reaction between 1a and 2a by 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT)/N-methyl morpholine (NMM) system or isolated 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium (DMTMM) in different solvents.

| Entry | Solvent | Coupling Agent [a] | Yield (%) [b] (15/60 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | THF | CDMT/NMM | 74/78 |

| 2 | THF | DMTMM | 80/89 |

| 3 | CH3OH | CDMT/NMM | 93/95 |

| 4 | CH3OH | DMTMM | 98/99 |

| 5 | EtOH | CDMT/NMM | 92/95 |

| 6 | EtOH | DMTMM | 98/99 |

| 7 | CH3CN | CDMT/NMM | 78/82 |

| 8 | CH3CN | DMTMM | 58/66 |

| 9 | Acetone | CDMT/NMM | 82/83 |

| 10 | Acetone | DMTMM | 73/97 |

| 11 | CH2Cl2 | CDMT/NMM | 86/93 |

| 12 | CH2Cl2 | DMTMM | 85/92 |

| 13 | Toluene | CDMT/NMM | 69/90 |

| 14 | Toluene | DMTMM | 65/72 |

| 15 | H2O | CDMT/NMM | 45/52 [c] |

| 16 | H2O | DMTMM | 49/53 [c] |

Reaction conditions: benzoic acid: 1.3 mmol, phenylethylamine: 1.2 mmol, Solvent: 6 mL, T: 25 °C. [a] Coupling agent: 1.3 mmol of CDMT and 1.3 mmol of NMM were added; for isolated DMTMM, 1.3 mmol were used. [b] Yield of 3a was measured by GLC using mesitylene as internal standard. [c] Yields were measured on weight of 3a recovered after workup.

2.1. Influence of the Solvent on Dehydro-Condensation Reactions

Preliminarily investigations on the CDMT/tert-amine system were carried out by using NMM as amine. The influence of the solvent on the CDMT/NMM dehydro-condensation activity was tested employing benzoic acid 1a and phenylethylamine 2a as standard substrates (Scheme 1). Relevant data are reported in Table 1 and compared with data from analogous reactions carried out in the presence of isolated DMTMM. All data reported in Table 1 are the mean values achieved for a set of at least three experiments monitored after 15 min and 1 h.

Interestingly, after 15 min, the CDMT/NMM system afforded, in most of the organic solvents used, the amide 3a in equivalent or even better yields compared to DMTMM. In CH3OH, almost quantitative yield of 3a was measured both with DMTMM (98%) and CDMT/NMM (93%) by 15 min (entries 3 and 4, Table 1). Noteworthy, the use of an alcohol (entries 3–6, Table 1) as reaction solvent achieved 3a (≥90%) with very high selectivity, both by CDMT/NMM system and isolated DMTMM, and only traces of the corresponding ester were detected. These data are in agreement with Kunishima work [58], where the rate of nucleophilic attack of 2-phenylethylamine to 3-phenylpropionic acid (aminolysis) was found to be approximately 2 × 104 times faster than methanolysis. This is a significant advantage compared to other dehydro-condensation agents such as EDC/NHS for which yields and selectivity in similar reaction conditions are known to be poor [6,20]. Moreover, the difference in reactivity of the amine functionality, compared to, e.g., -OH or -SH groups, allows to carry out chemoselective dehydro-condensation reactions for the synthesis of amides, starting from carboxylic acids or amines bearing also -OH or -SH functionalities, as widely reported in the literature [58,59,60,61]. Additionally, when the amine contains both a hydroxyl and an amine functional group, no ester by-product is observed confirming that the reactivity of the amine functional group is by far much higher than that of the -OH group so that no ester is formed in the presence of DMTMM [46,58,61] and other 1,3,5-triazine-based dehydro-condensation agents [57]. In comparison to catalytic amidation reactions, triazine-derived dehydro-condensation agents proceed well also in relatively nonpolar solvents, which still today limits wide application of catalytic amidation reactions [4].

In fact, in toluene as solvent, CDMT/NMM led to very good yield of 3a (90%) after 1 h, higher than in the presence of DMTMM (entries 13 and 14, Table 1). On the other hand, significantly lower yields in amide 3a where obtained in water as reaction solvent (entries 15 and 16 of Table 1) probably due to low water solubility of the substrates.

Thus, according to data reported in Table 1, activity and selectivity of CDMT/NMM system and isolated DMTMM were shown to be very similar. The use of alcohols promoted best performances for both dehydro-condensation systems tested, hence, further experiments were carried out in CH3OH.

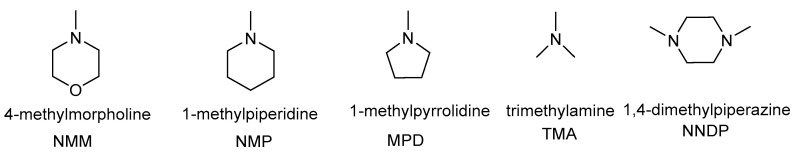

2.2. Influence of the Tert-Amine on Dehydro-Condensation Reactions

Spurred by the positive results obtained, further dehydro-condensation reactions for the synthesis of 3a were carried out in the presence of CDMT and different tertiary N-methyl-substituted aliphatic amines (see Figure 3) employing methanol as solvent. Since, the synthesis of quaternary ammonium salts prepared from CDMT and N-ethyl tertiary aliphatic or aromatic amines has been extensively studied in the literature [43], showing in most cases very unsatisfactory results, N-ethyl tert-amines were not investigated in this work.

Figure 3.

Tert-amines used in combination with CDMT.

Data collected for the synthesis of 3a in the presence of different CDMT/tert-amine systems were compared, when possible, with corresponding dehydro-condensation data achieved in the presence of isolated DMT-Ams(X) (see Table 2). In fact, comparison of the activity of DMT-Ams(X) and CDMT/tert-amine systems as dehydro-condensation agents was not always possible since, depending on the tert-amine used, the isolation of the DMT-Ams(X) may be problematic, due to instability of the corresponding quaternary ammonium salt and formation of a triazine derivative, which is totally inactive as dehydro-condensation agent (see Scheme 2) [57]. As a matter of fact, only DMTMM was isolated in good yield while all other DMT-Ams(Cl) were highly unstable and could not be isolated.

Table 2.

Dehydro-condensation reaction between 1a and 2a with CDMT/tert-amine system or isolated 2-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazinyl)trialkyl ammonium salts (DMT-Ams).

| Entry | Coupling Agent [a] | Counter Anion [b] | Yield (%) [c] (15/60 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CDMT/NMM | Cl− | 93/95 |

| 2 | DMTMM | Cl− | 98/99 |

| 3 | CDMT/NMM | ClO4− | 82/83 |

| 4 | DMTMM | ClO4− | 38/47 |

| 5 | CDMT/TMA | Cl− | 93/96 |

| 6 | DMTTMA [d] | Cl− | n.d. |

| 7 | CDMT/TMA | ClO4− | 87/91 |

| 8 | DMTTMA | ClO4− | 79/81 |

| 9 | CDMT/NMP | Cl− | 49/52 |

| 10 | DMTMP [d] | Cl− | n.d. |

| 11 | CDMT/NMP | ClO4− | 56/60 |

| 12 | DMTMP | ClO4− | 86/90 |

| 13 | CDMT/MPD | Cl− | 65/77 |

| 14 | DMTMPD [d] | Cl− | n.d. |

| 15 | CDMT/MPD | ClO4− | 68/80 |

| 16 | DMTMPD | ClO4− | 80/85 |

| 17 | CDMT/NNDP | Cl− | 93/96 |

| 18 | CDMT/NNDP [e] | Cl− | 92/95 |

| 19 | CDMT/NNDP [f] | Cl− | 79/90 |

| 20 | DMTDP [d] | Cl− | n.d. |

| 21 | CDMT/NNDP | ClO4− | 77/88 |

| 22 | DMTDP [d] | ClO4− | n.d. |

Reaction conditions: benzoic acid: 1.3 mmol, phenylethylamine: 1.2 mmol, solvent: CH3OH (6 mL), T: 25 °C. [a] Coupling agent: 1.3 mmol of CDMT and 1.3 mmol of tertiary amine were added, for isolated DMT-Ams, 1.3 mmol of were added. [b] For the CDMT/tert-amine/NaClO4 system, 1.3 mmol of CDMT, 1.3 mmol of NaClO4, and 1.3 mmol of tertiary amine were added, while of the isolated system, 1.3 mmol of DMT-Ams(ClO4) were added to the reaction mixture. [c] Yield in 3a was measured by GLC using mesitylene as internal standard. [d] Not determined since the isolated DMT-Ams(Cl) was not isolated. [e] For this, 0.75 eq of tert-amine used. [f] For this, 0.5 eq of tert-amine used.

Scheme 2.

The 2-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazinyl)trialkyl ammonium salts (DMT-Ams) demethylation.

All CDMT/tert-amine systems tested were active as dehydro-condensation agents, as reported in Table 2. Similarly to CDMT/NMM, the CDMT/TMA system allowed to obtain 3a with 96% yield in 1 h (entry 5, Table 2).

Moderately lower yields of amide 3a were obtained with CDMT/NMP (49%, entry 9, Table 2) or CDMT/MPD (65%, entry 13, Table 2). CDMT was also tested in combination with 1,4-dimethylpiperazine (NNDP, entries 17–19, Table 2) to verify if double quaternarization of the two tertiary amine functionalities present on NNDP could allow to reduce the amount of tert-amine required. In fact, when a 1/1 molar ratio of CDMT/NNDP was employed, yields in 3a achieved were comparable to the ones obtained with DMTMM and CDMT/NMM (compare entries 1, 2, and 17, Table 2). Notably, when the CDMT/NNDP molar ratio was decreased to 1/0.75 (entry 18, Table 2) and 1/0.5 (entry 19, Table 2), excellent yields of 3a were still achieved, reducing up to half the amount of tert-amine employed. Adversely, DMT-NNDP(X) could not be isolated either with Cl− or ClO4− counter anion (see below). From this first screening, higher versatility of CDMT/tert-amine system compared to isolated DMT-Ams(X) clearly appeared.

In order to compare the activity of CDMT/tert-amine systems with isolated DMT-Ams(X), stability problems, which strongly limited the library of isolated DMT-Ams(Cl) available, were partially overcome by counter anion exchange of the Cl− atom with ClO4−, BF4−, and PF6− [43,55]. Nevertheless, since BF4− and PF6− gave scantly soluble quaternary ammonium salts, only DMT-Ams(ClO4) were further synthesized and their activity for dehydro-condensation reactions was compared with CDMT/tert-amine systems. Data reported in Table 2 revealed that most of the isolated DMT-Ams(ClO4) tested for the dehydro-condensation reaction of 1a and 2a gave good yields in 3a, comparable to those achieved with the corresponding CDMT/tert-amine systems. Nevertheless, it should be considered that the synthesis of isolated DMT-Ams(ClO4) required the use of organic solvents (THF) and a stochiometric amount of a perchlorate salt, reducing their overall sustainability.

Moreover, counter anion exchange in the presence of DMTMM strongly reduced the activity of the corresponding isolated perchlorate salt, and the yield in 3a decreased from 99% with DMTMM (entry 2, Table 2) to 47% with DMTMM(ClO4), by 1 h (entry 4, Table 2). This behavior may be attributed to two different but correlated phenomena: substitution of the counter anion generally increased the stability of the isolated ammonium salt but at the same time, it decreased the solubility of the quaternary ammonium salt and consequently its reactivity as dehydro-condensation agent [55]. Thus, by counter anion exchange, DMTMM(ClO4) could be isolated but, in CH3OH as solvent, had reduced solubility and reactivity as dehydro-condensation agent.

In principle, counter anion exchange should not influence the activity of CDMT/tert-amine systems, used according to the procedure reported in this work, since no isolation of DMT-Ams(X) was required and thus stability problems should not be encountered. In fact, in agreement with this hypothesis and according to data reported in Table 2, the addition of NaClO4 in most cases did not significantly alter the activity of the CDMT/tert-amine system. Comparing CDMT/TMA (entries 5 and 7, Table 2), CDMT/NMP (entries 9 and 11, Table 2), and CDMT/MPD (entries 13 and 15, Table 2) systems with Cl− or ClO4− anion, yields in 3a were approximately equivalent.

However, for CDMT/NMM/NaClO4 system, the activity in dehydro-condensation reaction of 1a and 2a significantly decreased and yield of 3a were lower than the ones achieved with CDMT/NMM, even after 1 h (entries 1 and 3, Table 2).

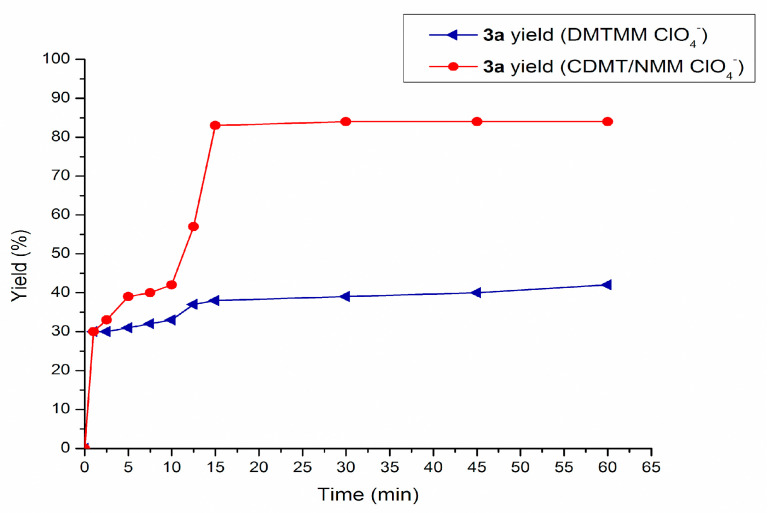

Since data reported in Table 1 and Table 2 showed in most cases very small differences in yields of 3a after 15 min and 1 h, in order to better compare the reactivity of the CDMT/tert-amine system to the DMT-Ams(X) one, a kinetic study was carried out (Figure 4). Data reported in Figure 4 show the kinetic profile for the yield in 3a, monitored by GLC over a period of 1 h at room temperature, in the presence of CDMT/NMM/ClO4 system or isolated DMTMM(ClO4) (entries 3–4, Table 2).

Figure 4.

Kinetic profile of dehydro-condensation reaction between 1a and 2a in the presence of CDMT/N-methyl morpholine (NMM)/ClO4 and DMTMM(ClO4).

Notably, formation of 3a was already evidenced after 1 min from the start of the reaction with both dehydro-condensation systems, and after 5 min significant differences in the rate of formation of 3a were evident between CDMT/NMM/ClO4 system and isolated DMTMM(ClO4). The second considerable gap occurred after 10 min, as the CDMT/NMM/ClO4 system proceeded with an exponential type trend, while DMTMM(ClO4) maintained an approximately linear trend. Finally, in both cases, a plateau was reached after 15 min.

Data gathered in Table 2 and Figure 4 contributed to give deeper insight into the activity and versatility of CDMT/tert-amine system compared to isolated DMT-Ams(X) for carboxylic acid-amine dehydro-condensation reactions, according to the protocol reported in this work. Counter anion experiments evidenced differences between isolated DMT-Ams(X) and CDMT/tert-amine systems, possibly ascribable to differences in the reaction pathway. According to the literature [56,57,62] when isolated DMTMM is employed as condensation agent, the reaction mechanism initially foresees the reaction between the carboxylic acid and DMTMM, forming an activated ester (4), which then undergoes attack by an amine to give the corresponding amide as illustrated in Scheme 3 pathway a. Alternatively, literature data report a two steps protocol, foreseeing reaction of CDMT/tert-amine in the reaction solvent in the presence of a carboxylic acid for approximately 1 h, followed by addition of a primary amine (Scheme 3 pathway b) [43]. According to literature data, it is generally assumed that, in these reaction conditions, once CDMT and the tert-amine are added to the reaction solvent, the corresponding quaternary ammonium salt is formed prior to dehydro-condensation reaction.

Scheme 3.

Possible known pathways for amidation of 1a and 2a in the presence of 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM) (a) or 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT) (b) /N-methyl morpholine (NMM) system.

Preliminary experimental evidences collected by 1H NMR spectroscopy (see Supporting Information) seem to indicate that the protocol reported in this work for the use of CDMT/tert-amine systems differs from previously reported mechanisms and may not lead to the formation of DMT-Ams(X) as reported in Scheme 3, but possibly to the straightforward formation of the intermediate active ester (4), which according to the literature is supposed to be the rate-determining step, thus boosting the efficacy of the derived dehydro-condensation agents [58,63]. Further experiments are ongoing to gain deeper insight into this reaction mechanism.

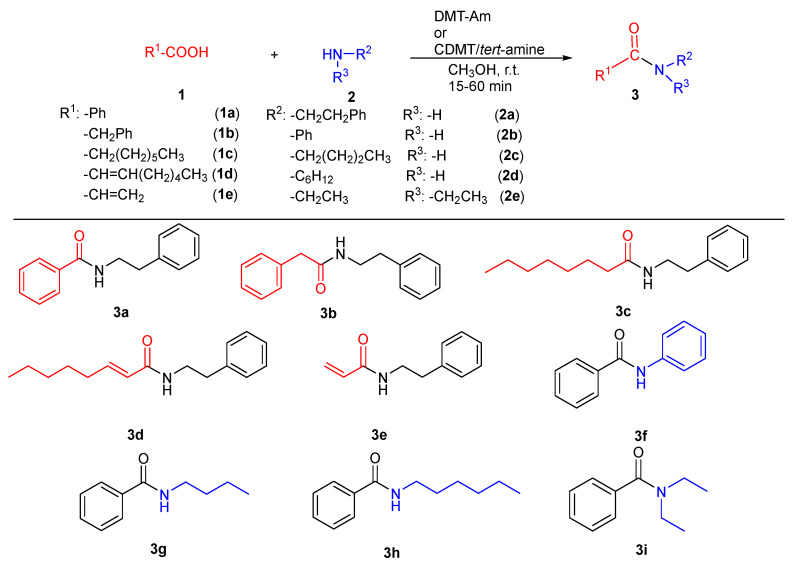

2.3. CDMT/Tert-Amine Activity for the Dehydro-Condensation of Various Primary Amines and Carboxylic Acids

To widen the scope of the CDMT/tert-amine system, dehydro-condensation reactions for the synthesis of different amides were tested (see Figure 5) ranging from aliphatic, aromatic, sterically hindered, and α,β-unsaturated acids.

Figure 5.

Reaction between different acids (1a–e) and different amines (2a–e) in the presence of various CDMT/tert-amine systems.

Only tert-amines that gave best results, as reported in Table 2, were further investigated (NMM, NNDP, and TMA). Primary and secondary aliphatic amines as well as aniline could be condensed to give the corresponding amides (see Table 3). Best yields in 3b were obtained with CDMT/NMM (87% in 1 h, entry 4, Table 3), although with slightly lower yield than for 3a (95%, entry 1, Table 3) probably due to reduced nucleophilicity of the carboxyl group of 1b compared to 1a, which disfavors the formation of the active ester.

Table 3.

Dehydro-condensation reaction of 2a and a carboxylic acid (1a–1e) by CDMT/tert-amine system.

| Entry | Acid | Coupling Agent [a] | Amide | Yield (%) [b] (15/60 min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a | CDMT/NMM | 3a | 93/95 |

| 2 | CDMT/NNDP | 92/95 | ||

| 3 | CDMT/TMA | 93/96 | ||

| 4 | 1b | CDMT/NMM | 3b | 82/87 |

| 5 | CDMT/NNDP | 69/71 | ||

| 6 | CDMT/TMA | 45/51 | ||

| 7 | 1c | CDMT/NMM | 3c | 71/75 |

| 8 | CDMT/NNDP | 65/74 | ||

| 9 | CDMT/TMA | 12/15 | ||

| 10 | 1d | CDMT/NMM | 3d | 88/92 |

| 11 | CDMT/NNDP | 70/86 | ||

| 12 | CDMT/TMA | 18/21 | ||

| 13 | 1e | CDMT/NMM | 3e | 34/38 |

Reaction conditions: phenethylamine 2a: 1.2 mmol, carboxylic acid (1a–1e): 1.3 mmol, solvent: CH3OH (6 mL), T: 25 °C. [a] Coupling agent: 1.3 mmol of CDMT and 1.3 mmol of tertiary amine. [b] Yields were measured by GLC using mesitylene as internal standard.

Similar charge effects were observed for the synthesis of 3c and 3d (see entries 7 and 10, Table 3). 1e was tested only with CDMT/NMM system giving very low yields (38% in 1 h, entry 13, Table 3).

Further dehydro-condensation reactions of 1a and amines 2b–2e are reported in Table 4. When amine 2b was used, a specular behavior to the one reported for 3b was observed, since the presence of a phenyl ring vicinal to the amine functionality increases electron density on the nitrogen atom reducing the overall dehydro-condensation yield in 3f.

Table 4.

Dehydro-condensation reaction of 1a and an amine (2b–2e) by CDMT/tert-amine system.

| Entry | Amine | Coupling Agent [a] | Amide | Yield (%) [b] (15/60 min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2b | CDMT/NMM | 58/74 | |

| 2 | CDMT/NNDP | 3f | 49/65 | |

| 3 | CDMT/TMA | 52/67 | ||

| 4 | 2c | CDMT/NMM | 77/93 | |

| 5 | CDMT/NNDP | 3g | 59/64 | |

| 6 | CDMT/TMA | 72/78 | ||

| 7 | 2d | CDMT/NMM | 61/70 | |

| 8 | CDMT/NNDP | 3h | 55/58 | |

| 9 | CDMT/TMA | 19/30 | ||

| 10 | 2e | CDMT/NMM | 56/66 | |

| 11 | CDMT/NNDP | 3i | 50/55 | |

| 12 | CDMT/TMA | 34/35 |

Reaction conditions: benzoic acid 1a: 1.3 mmol, amine 2b–2e: 1.2 mmol, solvent: CH3OH (6 mL), T: 25 °C. [a] Coupling agent: 1.3 mmol of CDMT and 1.3 mmol of tertiary amine. [b] Yields were measured by GLC using mesitylene as internal standard.

Aliphatic amine 2c gave very good dehydro-condensation yields in 3g, above 75%, both with CDMT/NMM and CDMT/TMA (entries 4 and 6, Table 4).

Sterical hindrance was supposed to be the cause of moderately lower yields in 3h. Secondary aliphatic amines (2e) are known to be less reactive and, in fact, yields in the corresponding amide (3i) were lower (entries 10–12, Table 4).

3. Materials and Methods

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). GC analyses were carried out on an Agilent 6850A Gas chromatograph (HP1 capillary column). GC–MS analyses were performed on an Agilent MS Network 5937 (HP5 capillary column). Mesitylene was used as internal standard. 1H and 13C {1H} NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 300 spectrometer operating at 300.21 and 75.44 MHz. The chemical shift values of the spectra are reported in δ units with reference to the residual solvent signal.

Unless otherwise reported, DMT-Ams(ClO4) were synthesized from CDMT with the corresponding tertiary amine and NaOCl4 according to the synthetic procedure reported in the literature [43,53]. All products, 3a-3i, were characterized and purity was confirmed by comparison to the literature data [64,65,66,67,68,69,70].

3.1. Synthesis of DMTTMA(ClO4)

TMA (75 mg, 1.27 mmol) was added to a solution of CDMT (200 mg, 1.14 mmol) and NaClO4 (155 mg, 1.27 mmol) in THF (4 mL) at 25 °C. After stirring for 1 h, the precipitate was collected, washed with THF, and dried under reduced pressure to give DMTTMA(ClO4)− as a white solid (340 mg, yield 99%). m.p. 163–168 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, D2O, 25 °C): δ = 4.21 (s, 6H), 3.65 ppm (s, 9H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, D2O, 25 °C): δ = 175.2, 173.6, 58.6, 55.7 ppm; IR (KBr): ṽ = 1606, 1531, 1485, 1375, 1052, 825, 624 cm−1.

3.2. General Procedure for Dehydro-Condensation Reactions with CDMT/Tert-Amine System

Acid 1a (158.7 mg, 1.3 mmol) was dissolved in a solvent (MeOH, 6 mL) and subsequently CDMT (228.2 mg, 1.3 mmol), NMM (131.5 mg, 1.3 mmol), and amine 2a (145.4 mg, 1.2 mmol) were added. After 15 min and 1 h, yield in amide 3a was monitored by GLC using mesitylene as internal standard. To isolate 3a, the reaction mixture was filtered and the yellowish solid recovered was dissolved in CH2Cl2 and extracted with water (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic phases were dried over MgSO4 filtered and concentrated in vacuo to give 3a as a white solid.

3.3. General Procedure for Dehydro-Condensation Reaction with Isolated DMTMM

Acid 1a (158.7 mg, 1.3 mmol) was dissolved in solvent (MeOH, 6 mL) and subsequently DMTMM (359.7 mg, 1.3 mmol) and amine 2a (145.4 mg, 1.2 mmol) was added. After 15 min and 1 h, yield in amide 3a was monitored by GLC using mesitylene as internal standard. The procedure to isolate 3a was the same as abovementioned.

NMR Characterization of Products 3a–3i

N-phenylethyl-benzamide (3a): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.79–7.60 (m, 2H), 7.57–7.08 (m, 8H), 6.10 (bs, 1H), 3.73 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.95 ppm (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 167.4, 138.4, 134.5, 132.0, 128.8, 128.6, 127.7, 126.5, 125.9, 41.1, 34.9 ppm.

N-phenethyl-2-phenylacetamide (3b): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.35–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.28–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.21–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.06–7.02 (m, 1H),5.52 (bs, 1H), 3.54 (s, 2H), 3.47 (c, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.75 ppm (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 171.2, 138.9, 135.1, 129.6, 129.2, 128.2,128.2, 127.1, 126.4, 43.8, 40.9, 35.6 ppm.

N-Phenethyloctanamide (3c) 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.30 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.25–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.21–7.14 (m, 2H), 5.57 (br. s, 1H), 3.51 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.81 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.11 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.62–1.53 (m, 2H), 1.31–1.20 (m, 8H), 0.87 ppm (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 173.3, 139.1, 128.9, 128.7, 126.6, 40.6, 36.9, 35.8, 31.8, 29.3, 29.1, 25.9, 22.7, 14.2 ppm.

N-(2-phenylethyl)oct-2-enamide (3d) 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.30 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.25–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.21–7.14 (m, 2H), 5.57 (br. s, 1H), 3.51 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.81 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.11 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.62–1.53 (m, 2H), 1.31–1.20 (m, 8H), 0.87 ppm (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 173.3, 139.1, 128.9, 128.7, 126.6, 40.6, 36.9, 35.8, 31.8, 29.3, 29.1, 25.9, 22.7, 14.2 ppm.

2-phenylethyl acrylamide (3e) 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.27–7.20 (m, 5H), 6.92–6.87 (m, 1H), 6.18–6.12 (m, 1H), 3.44(t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 2.72 (t, J = 5 Hz, 2H), 2.22–2.18 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.38–1.25 (m, 6H). 0.90 ppm (m, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 166.8, 142.1, 138.8, 128.7, 128.6, 125.4,122.1, 40.6, 35.6, 33.8, 32.9, 31.8, 28.5, 22.7, 14.3 ppm.

Phenylbenzamide (3f) 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.13–7.87 ppm (m, 10H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 165.8. 138.0 135.0 131.9, 129.1, 128.8, 127.1, 124.6, 120.3 ppm.

N-Butylbenzamide (3g) 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.74–7.78 (m, 2H), 7.47–7.51 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.45 (m, 2H), 6.14 (br s, 1H), 3.46 (dt, 2H, J = 6.8, 6.4 Hz), 1.61 (tt, 2H, J = 7.2, 7.2 Hz), 1.42 (qt, 2H, J = 7.2, 7.6 Hz), 0.96 ppm (t, 3H, J = 7.4 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 167.6, 134.9, 131.3, 128.5, 126.8, 39.8, 31.8, 20.2, 13.8 ppm.

N-Hexylbenzamide (3h) 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.77–7.75 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.47 (m, 3H), 6.42 (br s, 1H, NH), 3.43 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 1.60 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 1.36 (s, 2H), 1.31(d, J = 2.5 Hz, 4H), 0.88 ppm (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 167.5, 134.8, 131.2, 128.4, 126.8, 40.1, 31.5, 29.6, 26.6, 22.5, 14.0 ppm.

N,N-Diethylbenzamide (3i). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 7.46−7.30 (m, 5H), 3.40 (br s, 4H), 1.17 ppm (br s, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 171.3, 137.3, 129.1, 128.4, 126.3, 43.2, 39.2, 14.1, 12.9 ppm.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a library of CDMT/tert-amine systems was investigated and their activity as dehydro-condensation agents for the production of amides compared to similar isolated quaternary ammonium salts synthesized by reaction of CDMT with a tert-amine (DMT-Ams(X), with X: Cl− or ClO4−) was studies. In most cases, the CDMT/tert-amine systems prepared by simultaneous addition of a carboxylic acid, an amine, CDMT, and a tert-amine in the reaction solvent gave comparable or higher yields than the corresponding isolated DMT-Ams(X) species, both with Cl− or ClO4− as counter anion. In the presence of Cl− as counter anion, only DMTMM could be synthesized and employed for dehydro-condensation reaction of 1a and 2a, while all corresponding CDMT/tert-amine system tested gave high yields in amide 3a. Further studies are ongoing to gain deeper insight into the possible mechanistic differences between the two families of dehydro-condensation agents.

Moreover, CDMT/tert-amine may be used in alcohols or even water without any influence on the selectivity in the desired amide, adversely to other amidation protocols, which require less environmentally friendly and more expensive aprotic solvents.

The possibility to use CDMT/tert-amine systems allowed to achieve a library of easy and sustainable dehydro-condensation agents. Consequently, tert-amines could be chosen according to specific requirements such as availability, cost and risk assessment, and features, which may be crucial for industrial applications [71]. Additionally, amines such as NNDP, having two reactive tert-amine groups, allowed to reduce the consumption of the tert-amine up to 50%. Further advantage of both CDMT/tert-amine systems and DMTMM, compared to other dehydro-condensation agents commonly used today, is that triazine by-product formed during the reaction (DMTOH) is nontoxic and can be recovered and recycled to produce CDMT or DMTMM [26]. In summary, CDMT/tert-amine systems, formulated according to the specific protocol reported in this work, have been demonstrated to be very active, versatile, simple, and environmentally sustainable alternatives to many conventional dehydro-condensation agents employed today.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplementary Materials are available online, Chapter I contains the NMR and FT-IR spectra of DMTTMA(ClO4) and Chapter II contains the 1H NMR of the dehydro-condensation reaction products and triazine derivatives monitored in time.

Author Contributions

All authors: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing; V.B., R.S., and V.G.: data analysis; V.B., R.S., V.G., S.C., N.B. and A.M.: writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Albericio F., El-Faham A. Choosing the right coupling reagent for peptides: A twenty-five-year journey. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018;22:760–772. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajput P., Sharma A. Synthesis and biological importance of amide analogues. J. Pharmacol. Med. Chem. 2018;2:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krause T., Baader S., Erb B., Goossen L.J. Atom-economic catalytic amide synthesis from amines and carboxylic acids activated in situ with acetylenes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanigan R.M., Sheppard T.D. Recent developments in amide synthesis: Direct amidation of carboxylic acids and transamidation reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013;33:7453–7465. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201300573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M.Y., Gang H.Z., Zhou L., Liu J.F., Mu B.Z., Yang S.Z. A high yield method for the direct amidation of long-chain fatty acids. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2020;52:99–108. doi: 10.1002/kin.21334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Faham A., Albericio F. Peptide couplig reagents, more than a letter soup. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:6557–6602. doi: 10.1021/cr100048w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarecki A.P., Kolanowski J.L., Markiewicz W.T. Microwave-assisted catalytic method for a green synthesis of amides directly from amines and carboxylic acids. Molecules. 2020;25:1761. doi: 10.3390/molecules25081761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo L., Jia S., Diercks C.S., Yang X., Alshmimri S.A., Yaghi O.M. Amidation, esterification, and thioesterification of a carboxyl-functionalized covalent organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:2023–2027. doi: 10.1002/anie.201912579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philipova I., Stavrakov G., Dimitrov V., Vassilev N. Galantamine derivatives: Synthesis, NMR study, DFT calculations and application in asymmetric catalysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1219:128568. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Faham A., Albericio F. Morpholine-based immonium and halogenoamidinium salts as coupling reagents in peptide synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:2731–2737. doi: 10.1021/jo702622c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massolo E., Pirola M., Benaglia M. Amide bond formation strategies: Latest advances on a dateless transformation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020;30:4641–4651. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.202000080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma S., Das J., Braje W.M., Dash A., Handa S. A Glimpse into green chemistry practices in the pharmaceutical industry. ChemSusChem. 2020;13:2859–2875. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumari S., Carmona A.V., Tiwari A.K., Trippier P.C. Amide bond bioisosteres: Strategies, synthesis, and successes. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:12290–12358. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sole R., Bortoluzzi M., Spannenberg A., Tin S., Beghetto V., de Vries J.G. Synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of novel ruthenium complexes bearing NNN click based ligands. Dalton Trans. 2019;48:13580–13588. doi: 10.1039/C9DT01822K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang F., Li L., Zhang J., Gong H. Metal–and solvent-free synthesis of amides using substitute formamides as an amino source under mild conditions. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:2787. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39240-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheldon R.A. Green chemistry and resource efficiency: Towards a green economy. Green Chem. 2016;18:3180–3183. doi: 10.1039/C6GC90040B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Musaimi O., de la Torre B.G., Albericio F. Greening Fmoc/tBu solid-phase peptide synthesis. Green Chem. 2020;22:996–1018. doi: 10.1039/C9GC03982A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma S., Buchbinder N.W., Braje W.M., Handa S. Fast amide couplings in water: Extraction, column chromatography, and crystallization not required. Org. Lett. 2020;22:5737–5740. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treitler D.S., Marriott A.S., Chadwick J., Quirk E. Mutagenic impurities in 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019;23:2562–2566. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.9b00376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Este M., Eglin D., Alini M. A systematic analysis of DMTMM vs EDC/NHS for ligation of amines to Hyaluronan in water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014;108:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beghetto V., Gatto V., Conca S., Bardella N., Scrivanti A. Polyamidoamide dendrimers and cross-linking agents for stabilized bioenzymatic resistant metal-free bovine collagen. Molecules. 2019;24:3611. doi: 10.3390/molecules24193611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adamiak K., Sionkowska A. Current methods of collagen cross-linking: Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;161:550–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borke T., Winnik F.M., Tenhu H., Hietala S. Optimized triazine-mediated amidation for efficient and controlled functionalization of hyaluronic acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;116:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan Y.T., Pharmar T.H., Sangani C.B., Shah A.S., Ameta R.K. 1-[Bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo-[4,5-b] pyridinium3-oxide Hexafluorophosphate (HATU)/Hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT)-based one-pot cyclization of N-substituted 2-arylbenzimidazole derivatives. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2020;56:856–862. doi: 10.1134/S107042802005019X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albericio F. Developments in peptide and amide synthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vokkaliga S., Jeong J., LaCourese R., Kalivretenos A. Synthesis of amide libraries with immobilized HOBt. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:2722–2724. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.03.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itoh H., Miura K., Kamiya K., Yamashita T., Inoue M. Solid-phase total synthesis of Yaku’amide B enabled by traceless staudinger ligation. Angew. Chem. 2020;132:4594–4601. doi: 10.1002/ange.201916517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carpino L.A., Xia J., Zhang C., El-Faham A. Organophosphorus and nitro-substituted sulfonate esters of 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole as highly efficient fast-acting peptide coupling reagents. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:62–67. doi: 10.1021/jo0300183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpino L.A., El-Faham A. The diisopropylcarbodiimide/1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole system: Segment coupling and stepwise peptide assembly. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:6813–6830. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(99)00344-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carpino L.A., Imazumi H., El-Faham A., Ferrer F.J., Zhang C., Lee Y., Foxman B.M., Henklein P., Hanay C., Mügge C., et al. The uronium/guanidinium peptide coupling reagents: Finally the true uronium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:441–445. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<441::AID-ANIE441>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou X.M., Liang T.M., Guo Z.Y., Wang C.Y., Shao C.L. Discovery, absolute assignments, and total synthesis of asperversiamides A–C and their potent activity against mycobacterium marinum. Chem. Commun. 2019;55:1104–1107. doi: 10.1039/C8CC09347D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noguchi M., Nakamura M., Ohno A., Tanaka T., Kobayashi A., Ishihara M., Fujita M., Tsuchida A., Mizuno M., Shoda S. A dimethoxytriazine type glycosyl donor enables a facile chemo-enzymatic route toward α-linked N-acetylglucosaminyl-galactose disaccharide unit from gastric mucin. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:5560–5562. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30946g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamiński Z.J. Triazine-based condensing reagents. Biopolymers. 2000;55:140–164. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000)55:2<140::AID-BIP40>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura M., Sasaki S., Nishikawa R., Yamada K., Kunishima M. Imido-substituted triazines as dehydrative condensing reagents for the chemoselective formation of amides in the presence of free hydroxy groups. RSC Adv. 2018;8:22482–22489. doi: 10.1039/C8RA03057J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitamura M., Komine S., Yamada K., Kunishima M. Triazine-based dehydrative condensation reagents bearing carbon-substituents. Tetrahedron. 2020;76:130900. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2019.130900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scrivanti A., Bortoluzzi M., Sole R., Beghetto V. Synthesis and characterization of yttrium, europium, terbium and dysprosium complexes containing a novel type of triazolyl–oxazoline ligand. Chem. Pap. 2018;72:799–808. doi: 10.1007/s11696-017-0174-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kunishima M., Hioki K., Wada A., Kobayashi H., Tani S. Approach to green chemistry of DMT-MM: Recovery and recycle of coproduct to chloromethane-free DMT-MM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:3323–3326. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00546-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beghetto V., Agostinis L., Gatto V., Samiolo R., Scrivanti A. Sustainable use of 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride as metal free tanning agent. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;220:864–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beghetto V., Gatto V., Conca S., Bardella N., Buranello C., Gasparetto G., Sole R. Development of 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride cross-linked carboxymethyl cellulose films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;249:116810. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scrivanti A., Sole R., Bortoluzzi M., Beghetto V., Bardella N., Dolmella A. Synthesis of new triazolyl-oxazoline chiral ligands and study of their coordination to Pd (II) metal centers. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2019;498:119129. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2019.119129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petta D., Eglin D., Grijpma D.W., D’Este M. Enhancing hyaluronan pseudoplasticity via 4-(4, 6-dimethoxy-1, 3, 5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride-mediated conjugation with short alkyl moieties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;151:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.05.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hawkins P.M.E., Tran W., Nagalingam G., Cheung C.Y., Giltrap A.M., Cook G.M., Britton W.J., Payne R.J. Total synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of ohmyungsamycin A, deoxyecumicin, and ecumicin. Chem. Eur. J. 2020;66:15200–15205. doi: 10.1002/chem.202002408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunishima M., Ujigawa T., Nagaoka Y., Kawachi C., Hioki K., Shiro M. Study on 1,3,5-Triazine chemistry in dehydrocondensation: Gauche effect on the generation of active triazinylammonium species. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:15856–15867. doi: 10.1002/chem.201202236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamiński Z.J., Kolesińska B., Kamińska J.E., Góra J. A novel generation of coupling reagents. Enantiodifferentiating coupling reagents prepared in situ from 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT) and chiral tertiary amines. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:6276–6281. doi: 10.1021/jo0101499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamiński Z.J., Paneth P., Rudziński J. A study on the activation of carboxylic acids by means of 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine and 2-chloro-4,6-diphenoxy-1,3,5-triazine. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:4248–4255. doi: 10.1021/jo972020y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garret C.E., Jiang X., Prasad K., Repič O. New observations on peptide bond formation using CDMT. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4161–4165. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00754-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnett C.J., Wilson T.M., Kobierski M.E. A practical synthesis of multitargeted antifolate LY231514. Org. Process Res. Dev. 1999;3:184–188. doi: 10.1021/op9802172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker A.J., Adolph S., Connell R.B., Laue K., Roeder M., Rueggeberg C.J., Hahn D.U., Voegtli K., Watson J. Implementation of a High-Temperature Claisen Approach for Early Phase Delivery of a Benzopyran Derivative. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2010;14:85–91. doi: 10.1021/op900193v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villahuer E.B., Shieh W.C., Du Z., Vargas K., Ciszewki L., Lu Y., Girgis M., Lin M., Prashad M. Facile and practical synthesis of a cannabinoid-1 antagonist viaregio-and stereoselective ring-opening of an aziridinium ion. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:9067–9074. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.09.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kallman N.J., Liu C., Yates M.H., Linder R.J., Ruble J.C., Kogut E.F., Patterson L.E., Laird D.L.T., Hansen M.M. Route design and development of a MET kinase inhibitor: A copper-catalyzed preparation of an N1-methylindazole. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014;18:501–510. doi: 10.1021/op400317z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paganelli S., Alam M.M., Beghetto V., Scrivanti A., Amadio E., Bertoldini M., Matteoli U. A pyridyl-triazole ligand for ruthenium and iridium catalyzed C = C and C = O hydrogenations in water/organic solvent biphasic systems. Appl. Catal. A. 2015;503:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beghetto V., Scrivanti A., Bertoldini M., Aversa M., Zancanaro A., Matteoli U. A practical, enantioselective synthesis of the fragrances canthoxal, and silvial, and evaluation of their olfactory activity. Synthesis. 2015;47:272–278. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1379254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matteoli U., Beghetto V., Scrivanti A., Aversa M., Bertoldini M., Bovo S. An alternative stereoselective synthesis of (R)-and (S)-rosaphen via asymmetric catalytic hydrogenation. Chirality. 2011;23:779–783. doi: 10.1002/chir.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sole R., Taddei L., Franceschi C., Beghetto V. Efficient chemo-enzymatic transformation of animal biomass waste for eco-friendly leather production. Molecules. 2019;24:2979. doi: 10.3390/molecules24162979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raw S.A. An improved process for the synthesis of DMTMM-based coupling reagents. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:946–948. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.12.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunishima M., Kawachi C., Morita J., Terao K., Iwasaki F., Tani S. 4-(4,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methyl-morpholinium chloride: An efficient condensing agent leading to the formation of amides and esters. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:13159–13170. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(99)00809-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamiński Z.J. 2-Chloro-4,6-disubstituted-1,3,5-triazines a novel group of condensing reagents. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:2901–2904. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98867-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kunishima M., Kawachi C., Hioki K., Terao K., Tani S. Formation of carboxamides by direct condensation of carboxylic acids and amines in alcohols using a new alcohol- and watersoluble condensing agent: DMT-MM. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:1551–1558. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(00)01137-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirano N., Saijyo M. (Tokuyama Corporation), Method for Storing Quaternary Ammonium Salt. EP1178043A1. 2002 Feb 6;

- 60.Kameta N., Shiroishi H. PEG-nanotube liquid crystals as templates for construction of surfactant-free gold nanorods. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:4665–4668. doi: 10.1039/C8CC02013B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loebel C., D’Este M., Alini M., Zenobi-Wong M., Eglin D. Precise tailoring of tyramine-based hyaluronan hydrogel properties using DMTMM conjugation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;115:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamiński Z.J. 2-Chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine. A new coupling reagent for Peptide Synthesis. Synthesis. 1987;10:917–920. doi: 10.1055/s-1987-28122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamada K., Kota M., Takahashi K., Fujita H., Kitamura M., Kunishima M. Development of triazinone-based condensing reagents for amide formation. J. Org. Chem. 2019;84:15042–15051. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.9b01261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beghetto V. (Crossing Srl), Method for the Industrial Production of 2-halo-4,6-dialkoxy-1,3,5-triazine and Their Use in the Presence of Amines. EP 3237390B1. 2019 May 8;

- 65.Daa Funder E., Trads J.B., Gothelf K.V. Oxidative activation of dihydropyridine amides to reactive acyl donors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:185–198. doi: 10.1039/C4OB01931H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katarzyna J., Małolepsza J., Kusy D., Maniukiewicz W., Błażewska K.M. The McKenna reaction–Avoiding side reactions in phosphonate deprotection. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020;16:1436–1446. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.16.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu J.W., Wu Y.D., Dai J.J., Xu H.J. Benzoic acid-catalyzed transamidation reactions of carboxamides, phthalimide, ureas and thioamide with amines. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014;356:2429–2436. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201400068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fraczyk J., Kaminski Z.J., Katarzynska J., Kolesinska B. 4-(4,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium Toluene-4-sulfonate (DMT/NMM/TsO) universal coupling reagent for synthesis in solution. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2018;101:e1700187. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201700187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iqbal N., Cho E.J. Visible-light-mediated synthesis of amides from aldehydes and amines via in situ acid chloride formation. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:1905–1911. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li J., He S., Fu H., Chen X., Tang M., Zhang D., Wang B. An efficient procedure for chemoselective amidation from carboxylic acid and amine (ammonium salt) under mild conditions. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2018;44:2289–2303. doi: 10.1007/s11164-017-3229-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Álvarez-Pérez A., Esteruelas M.A., Izquierdo S., Varela J.A., Saá C. Ruthenium-catalyzed oxidative amidation of alkynes to amides. Org. Lett. 2019;21:5346–5350. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.