Abstract

There have been various systematic reviews on the significance of educational interventions as necessary components to encourage breast cancer screening (BCS) and reduce the burden of breast cancer (BC). However, only a few studies have attempted to examine these educational interventions comprehensively. This review paper aimed to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of various educational interventions in improving BCS uptake, knowledge, and beliefs among women in different parts of the world. Following the PRISMA guidelines, a comprehensive literature search on four electronic databases, specifically PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, was performed in May 2019. A total of 22 interventional studies were reviewed. Theory- and language-based multiple intervention strategies, which were mainly performed in community and healthcare settings, were the commonly shared characteristics of the educational interventions. Most of these studies on the effectiveness of interventions showed favorable outcomes in terms of the BCS uptake, knowledge, and beliefs among women. Educational interventions potentially increase BCS among women. The interpretation of the reported findings should be treated with caution due to the heterogeneity of the studies in terms of the characteristics of the participants, research designs, intervention strategies, and outcome measures.

Keywords: breast cancer, breast cancer screening, educational interventions, knowledge, beliefs

1. Introduction

The burden of breast cancer (BC) is enormous. Approximately 2.1 million female BC cases were diagnosed in 2018 alone. Apart from being the most diagnosed cancer globally, BC is believed to be the leading reason of cancer mortality in over 100 countries [1]. The mortality rates of BC have increased in certain countries which have historically had a lower rate, such as sub-Saharan Africa [1]. This trend is probably due to the increase in the incidence rates of BC with limited access to early detection and treatment, and late-stage diagnosis [2,3].

Early detection of the disease can save lives and increase the chances of being treated efficaciously [4]. The diagnosis of BC during the local stage (stage I and some stage II) has an overall 5-year relative survival rate of 99% while the diagnosis of BC during the regional stage (stage II or III) has a 5-year relative survival rate of 85%. However, the late stage (some stage III and all stage IV) diagnosis of BC has an overall 5-year relative survival rate of 27% [5]. Numerous methods have been assessed as breast cancer screening (BCS) approaches, such as breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE), and mammography (MMG) [6]. Getting regular screening examinations is the key strategy for detecting BC early and reducing the mortality rate of the disease [7]. However, a number of epidemiological studies on BCS behavioral uptake have been performed on community samples of various groups of women. Such studies have shown that the rate of BCS practice is low in various countries [8,9,10,11,12,13].

A good knowledge of BC and BCS is a prerequisite for the adherence to BCS among women [14]. A low level of knowledge among women in different parts of the world is linked to a low practice rate of BCS [8,15,16,17,18,19]. Various international studies and guidelines have stressed the significance of educational interventions as necessary components of effective BCS programs in order to encourage BCS and reduce the burden of the disease among women [8,17,18,20,21,22,23].

Demographic factors such as age, socio-economic status, and ethnicity are known to be associated with the use of health services and preventive health behaviors [24]. However, health education cannot modify demographic factors. Hence, developing efficient health education targeting modifiable individual characters is a challenge that in turn can predict preventive service usage and health behavior. Since beliefs are influenced by individual characteristics, they could provide an ideal target, as they affect behavior and are possibly modifiable. Beliefs distinguish individuals from the same background. However, at the same time, beliefs may reflect different socialization histories arising from demographic variation [25].

People’s participation in health promotion programs is predicted using health behavior theories [26]. Through such theories, remarkable progress in studying the determinants of a person’s health-related behavior in developing positive changes has been achieved [27]. Breast cancer screening is one behavior that is influenced by women’s health beliefs [28]. This behavior has been explained in studies conducted in accordance with a variety of theories. In such studies, the meaning of BC and BCS were described by one concept related to one behavior, or through a more compound framework. By far, the most commonly used theories in the promotion of BCS are the Transtheoretical Model (TTM), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the Health Promotion Model (HPM), the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), the Health Belief Model (HBM), and the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM).

Apart from BCS research, the effectiveness of health behavior theories has been proven to improve screening behaviors in other kinds of cancer. The Integrated Behavioral Model used by Serra et al. [29], for example, which involves constructs from the most commonly used theoretical models in health promotion (i.e., the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the SCT, the HBM, and the TPB) was found to be successful to improve colorectal cancer screening. Another study by Huang et al. [30] suggested that variables pertinent to the TPB could successfully predict colorectal cancer screening uptake. Further, the HBM was effective to improve colorectal cancer screening uptake in general [31]. Cervical cancer screening, on the other hand, was predicted by using the TPB [32,33]. Additionally, Shida et al. [34] and Aldohaian et al. [35] found that the HBM and the TRA have a positive effect on cervical cancer screening outcomes. Apart from that, the HBM could positively affect prostate cancer-preventive behaviors by improving individual knowledge level and leaving positive effects on their health beliefs [36].

Previous reviews on the effectiveness of educational interventions revealed improved screening rates with culturally relevant components, multiple strategies, language-appropriate interventions, multilevel interventions, personal and cognitive interventions, and model-based educational interventions [37,38,39,40,41,42]. However, these studies only sampled participants from specific countries or regions, which do not offer an international view [39,40,42,43]. Moreover, previous reviews focused on MMG uptake [39], knowledge of BC and BCS, and model-based intervention studies [38], while beliefs have not been explored [21,41,43,44]. Furthermore, the instruments used to evaluate the outcomes affect the quality of findings. The use of standardized, valid, and reliable tools assures high-quality data and simplifies the interpretation of the findings. However, previous reviews found that little is known about the tools used to measure outcomes. A good understanding of these points can help in the development of an effective BCS program for women. Although the program content, methods of delivery, and the person who delivers the intervention play a critical role in improving the knowledge and behavior towards BCS among women, these features have only been reviewed in brief. In this systematic review, these features are reviewed in further detail.

Overall, this systematic review primarily aims to evaluate the effectiveness of educational interventions on BCS uptake, knowledge, and beliefs among women in different parts of the world. A comprehensive assessment of these interventions potentially offers evidence on their efficacy for the development of future projects to address BC. This systematic review also presents valuable recommendations on the content and methods of delivery of such programs based on current evidence. Such programs are expected to promote BCS uptake and subsequently reduce the morbidity and mortality rates of BC in the long run.

2. Materials and Methods

The review was registered and conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines (Supplementary Table S1) with the registration number: CRD42020148423.

2.1. Literature Search

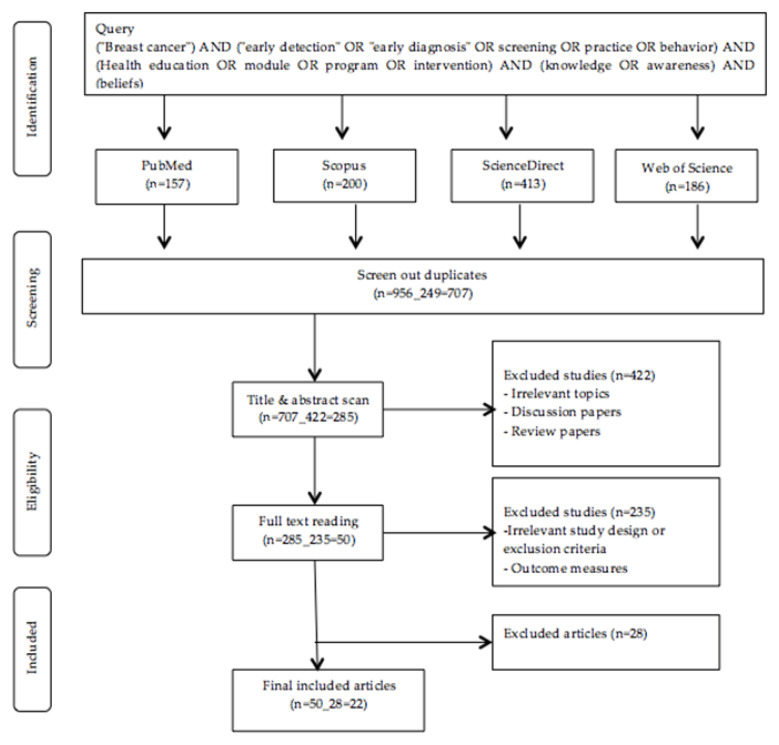

For this review, a comprehensive literature search on four electronic databases, specifically PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, was conducted in May 2019. In order to identify relevant articles, a combination of keywords was used (Figure 1). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to evaluate the gathered articles (Table 1). These criteria were executed in Figure 1. Two reviewers independently extracted data from the studies. Search strategy can be seen in the Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Types of Studies to Be Included | Types of Studies to Be Excluded |

|---|---|

|

|

| Participants Women aged eighteen years old and above, without history of BC. |

|

| Intervention Health promotion and behavioral program on BCS targeted women. |

|

| Control group Either usual care or no intervention, or minimal intervention or intervention other than the intervention groups. |

|

| Outcomes Any of the following: BCS uptake (BSE (breast self-examination), CBE (clinical breast examination), MMG (mammography)), knowledge of BC and screening, health beliefs about BC and screening. |

|

| Publication year From January 2014 to May 2019. |

|

| Language English. |

|

| Article type Original studies. |

The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) tool for intervention design studies was used to measure the quality of these studies. Using this tool, six domains, specifically research design, confounders, selection bias, blinding, data collection method, and dropouts and withdrawals, were evaluated. Each domain was valued as weak (one point), moderate (two points), or strong (three points). As for the total score, domain scores were averaged. As shown in Table 2, the quality of the studies was rated according to the following range of values: (1) weak quality: values of between 1.00 and 1.50; (2) moderate quality: values of between 1.51 and 2.50; (3) strong quality: values of between 2.51 and 3.00 [45,46]. Two reviewers independently evaluated the rating of these studies. Any arising disagreement on the rating was resolved with the involvement of a third reviewer.

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

| Study/Country | Study Design/EPHPP | Theory | Participants Characteristics/Sample size | Setting/Unit of Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RCT, Randomized control trials; TTM, The Transtheoretical Model; TPB, the Theory of Planned Behavior; HPM, the Health Promotion Model; SCT, the Social Cognitive Theory; HBM, the Health Belief Model; EM, the Ecological Model.

2.2. Data Synthesis

The characteristics and results of the studies are summarized in both narrative and tabular forms can be found in the Table 2.

3. Results

The literature search on four electronic databases yielded a total of 957 articles. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 422 articles were removed, resulting in a total of 50 full-text articles for further review. Following that, 28 articles were excluded after the application of the inclusion criteria. Hence, a total of 22 articles were retained (Figure 1).

3.1. Characteristics of Study

3.1.1. Participants and Setting

As shown in Table 2, the gathered studies were published between 2014 and 2019, and were conducted in Malaysia (n = 1) [16], Iran (n = 7) [19,47,48,49,50,51,52], United States (n = 6) [53,54,55,56,57,58], Turkey (n = 4) [10,11,59,60], Israel (n = 1) [9], United Arab Emirates (n = 1) [61], China (n = 1) [62], and India (n = 1) [63]. In addition, the participants were aged 18 years and above. With sample sizes of between 38 and 598, the participants were enrolled from communities (n = 12) [9,10,11,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] and healthcare settings (n = 6).

3.1.2. Conceptual Framework

As illustrated in Table 2, the conceptual framework was explained in 18 studies. Multiple models were used as a guide in the intervention development of five studies, where Fathollahi-Dehkordi and Farajzadegan [48], Lee-Lin et al. in 2015b [53], and Lee-Lin et al. in 2015a [57] employed the HBM and TTM, while Taymoori et al. [52] employed the HBM and The TPB and Tuzcu et al. [10] employed the HBM and the HPM.

The HBM was the most commonly used model (n = 10) [11,16,19,47,49,50,51,56,60,62]. The HBM theoretical framework incorporates six constructs, namely: (1) perceived susceptibility, (2) perceived severity, (3) perceived benefits, (4) perceived barriers, (5) cues to action, and (6) self-efficacy. This model emphasizes that threats from health problems can affect health behavior. Women who perceive susceptibility to BC risk or believe that the disease is a serious problem are more likely to do the screening test. Besides this, women who experience more benefits and fewer barriers to the screening test, have high health motivation, and can successfully perform a behavior are also more likely to do the screening test [64,65]. Diverse demographic factors and knowledge may also influence their perceptions and indirectly impact their health-related behaviors, as suggested by the model [66].

Meanwhile, the TTM framework explains health behavioral change as a continuum of stages. One would advance from pre-contemplation (the stage of not thinking about the behavioral change) to the stage of contemplation (thinking about the change) before advancing to the action stage (implement the behavior) and finally, maintaining that behavioral change [67]. On the other hand, according to TPB, one’s behavioral achievements are influenced by motivation (intention) and ability (behavioral control). This theory distinguishes three forms of beliefs, specifically behavioral belief, normative belief, and control belief [66]. Focusing on three points, specifically one’s features and experiences, behavior-specific cognition and affect, and behavioral outcomes [68], the HPM views health as a positive dynamic condition, rather than the absence of disease. The increase in the level of one’s well-being is directed by health promotion. The model explains the multidimensional nature of individuals, as they react within the environment to maintain health.

Apart from the above theories, Gondek et al. [58] and Goel and O’Conor [55] applied the SCT (n = 2) whereas Elder et al. [54] applied the EM (n = 1). The SCT explains that one’s health behaviors are influenced by personal experiences, environmental factors, and actions of others. In order to achieve a particular behavioral change, the theory provides ways for social support to achieve behavioral change by instilling expectations and self-efficacy and utilizing observational education and any other reinforcements [69]. Meanwhile, as for EM, multiple levels of effect are considered to explore the behavioral change that guides the evolution of further comprehensive interventions [70].

3.1.3. Intervention Strategies

As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, studies assigned the participants either into intervention or control groups individually (n = 13) [9,10,16,47,48,49,50,52,53,55,56,57,60] or through a unit-based approach (n = 3) [19. 51, 54]. The theory- and language-based approaches were the common characteristics of these educational interventions. With multiple intervention strategies, these programs were mostly performed in community and healthcare settings. All studies reported the utilization of linguistically appropriate methods in delivering interventions, of either spoken and written materials (n = 16) [9,10,16,19,47,49,51,52,53,54,56,57,59,60,61,62] or only spoken materials (n = 6) [11,48,50,55,58,63]. Furthermore, the program content in most of the studies mainly covered the key messages on normal breast anatomy, knowledge of BC and screening methods, knowledge on the significance and usefulness of screening methods, and health beliefs about BC and BCS. Table 3 shows intervention characteristics and findings in more detail.

Table 3.

Intervention characteristics and findings.

| Study | Intervention Characteristics | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Akhtari Zavare et al., 2016 [16] | Content: Breast health awareness/normal breast/BC knowledge/screening methods/training on BSE performance. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. 2 h workshops with a group of 12–13, delivered by the study researchers (1 h lecture in the form of PPT + 1 h training on BSE and participant’s duplication on breast silicon model) + educational booklet. Control group: Received all materials after the completion of the education. |

|

| Heydari and Noroozi, 2015 [49] | Content: Breast anatomy/warning against BC/perceived susceptibility and severity/benefit and barriers of MMG/MMG performance. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. Delivered by the study researchers. Group education: Two training sessions lasting 45–60 min with a 1-week interval. In the form of group discussion/oral presentation/PPT slides/SMS reminder. Multimedia education group: Training through CD/educational SMS/SMS reminder. |

|

| Eskandari-Torbaghan et al., 2014 [47] | Content: BC symptoms/right time for MMG/preventive behaviors of BC including healthy diet and physical activity/perceived sensitivity and seriousness, barriers in performing BC preventive behaviors. Methods of delivery: Spoken/written materials. Three sessions, delivered by the main investigators, each about 1–1.5 h long in the form of lectures/questions and answers/PPT/videos/educational booklet. Control group: Received training after the education completing. |

|

| Goel and O’Conor, 2016 [55] | Content: Importance of MMG/experience of undergoing MMG/BC grows and spreads. Method of delivery: Spoken. Delivered by healthcare provider. A brief 30-s video meeting between the provider and the participants. Control: Usual care. |

|

| Kocaöz et al., 2017 [59] | Content: Breast anatomy/unusual changes in the breast/importance of BC/risk factors/early diagnosis/symptoms/treatment/BSE. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. Delivered by the study investigators, a session of 40 min in the form of visual presentation/participants’ performance of BSE/an education brochure on BC and its screening/participation in screening programs. |

|

| Elder et al., 2017 [54] | Content: Breast anatomy/importance of BC prevention/risk factors and treatment/prevention steps/myths on BC/perceived barriers. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. A 6-week series of classes for each 90–120 min delivered by a trained bilingual/bicultural community healthcare worker. The intervention is a multilevel model that includes: Individual-level: BC screening classes/handouts to participants. Interpersonal level: Two motivational interviewing (MI) calls/reminder calls. Organizational level: Cancer screening sessions were announced in the church brochure/churches assigned spaces for education sessions. Environmental Level: Through training, promotors give information about the services and the local clinics, and completed Affordable Care Act workshops. Control: Physical activity intervention. |

|

| Yılmaz et al., 2017 [11] | Content: Symptoms and risk factors of BC/screening approaches (BSE, CBE, MMG). Method of delivery: Spoken. A 60–90 min PPT delivered by the study researcher. |

|

| Freund et al., 2017 [9] | Content: General screening recommendations/BC facts/early detection procedures/screening barriers, cultural and religious beliefs. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. The education was designed to be tailored culturally and personally for each participant through interview/discussion. Control: No treatment. |

|

| Mirmoammadi et al., 2018 [51] | Content: HBM constructs/breast anatomy/physiological changes in the breast/symptoms and signs of BC/methods of BCS/treatment of BC. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials, in 4 weekly sessions, 90 min long, of BCS individual consulting in the form of Q&A/speech/slideshow/group discussion/practical training/oral and practical test/booklet. Control: Routine care. After the study completion, the training booklet was offered to them. |

|

| Khiyali et al., 2017 [50] | Content: Risk factors/complications/screening methods including BSE/when and how to correctly perform BSE. Method of delivery: Spoken. The training program included 5 one-hour training sessions delivered by the study researcher through group discussion/video demonstration/training sessions. Control: No treatment. |

|

| Masoudiyekta et al., 2018 [19] | Content: BC facts and figures/BC epidemiology/risk factors, symptoms of BC/importance of early detection/screening methods/guidelines for MMG/health motivation/susceptibility to BC/benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy/list of public hospitals that provide MMG. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. Four 90–120 min teaching sessions in the form of PPT/videos/performing BSE on the models/group discussion/Q&A session/pamphlets. Control: No treatment. |

|

| Lee-Lin et al., 2015b [53] | Content for the intervention group: BC incidence/risk factors/process and benefits of MMG/cultural barriers. Content for the control group: Brochure consists of the following: do you think you are at risk of BC, what is MMG screening, who should get MMG, why and how should I get MMG, how can I pay, and where can I find information. It also stressed taking care of oneself. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. The TBHEP 1 h intervention included 2 parts, group teaching delivered by the study researcher followed by individual counseling by trained staff/the materials covered cultural, graphic like photos of both old and young Chinese women, Asian landscapes, and some dialogs between a Chinese grandmother, mother, and daughter/PPT/group discussions/Q&A sessions/face-to-face interactions. Control: A brochure emphasized caring for self. Reminder of follow-up survey with telephone calls in 3 months. |

|

| Lee-Lin et al., 2015a [57] | Content for the intervention group: BC incidence/risk factors/process and benefits of MMG/cultural barriers. Content for the control group: Brochure consists of the following: do you think you are at risk of BC, what is MMG screening, who should get MMG, why and how should I get MMG, how can I pay, and where can I find information. It also stressed taking care of oneself. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. The TBHEP 1 h intervention included 2 parts, group teaching delivered by the study researcher followed by individual counseling by trained staff/the materials covered culturally graphics like photos of both old and young Chinese women, the Asian landscapes, and some dialogs between a Chinese grandmother, mother, and daughter/PPT/group discussions/Q&A sessions/face-to-face interactions. Control: A brochure emphasized caring for self. Reminder of follow-up survey with telephone calls in 3 months. |

|

| Fathollahi-Dehkordi and Farajzadegan, 2018 [48] | Content: BC risk factors, signs and symptoms/screening tests/benefits of early diagnosis/ways to improve sensitivity, and severity of BC, methods to increase motivation, and overcoming barriers. Method of delivery: Spoken. Three sessions, 2 h long, in 4 groups with 10 to 15 women in three weeks, delivered by a peer educator in the form of oral presentation/image presentation/group discussion/women shared knowledge and beliefs on BC and BCS. The educator talked about her experiences and beliefs/women were also encouraged to connect with each other after the completion of the education and share their new practices to help one another to overcome screening barriers. Control: Invited to contribute in training session at the completion of the follow-up and education was offered to them. A telephone number for consultations were also provided to them. |

|

| Taymoori et al., 2015 [52] | The HBM intervention: Content: Perceived threat, MMG benefits and barriers, and self-efficacy. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. Eight sessions in the form of slides, pamphlets, films, group discussions, and role modeling with BC survivors. Delivered by research staff in groups of 5–12 women. Individual sessions tailored to women’s specific needs. Each woman received eight 45–60 min group sessions, women were divided into groups based on their reported requirements. The HBM + TPB intervention:Content: In addition to HBM intervention content, participants received sessions focused on subjective norms and perceived behavioral control. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. In addition to HBM methods of delivery, participants received 4 sessions on subjective norms and perceived control. Regarding subjective norms, small groups were formed to encourage peer support and to raise exposure to positive interpersonal norms, and education about the importance of developing social networks. In individual counseling sessions, participants were also asked to provide information for 5 relatives to remind them about MMG. Relatives were invited to participate in a 60 min session. Regarding perceived control, participants were trained to resolve environmental challenges. Reminder messages on scheduling MMG appointments and telephone conversations on subjective norms were also used. Control group: Received pamphlets following the completion of the follow-up survey. |

|

| Rabbani et al., 2019 [61] | Content: General information on BC/signs and symptoms of BC/BC epidemiology, risk factors, anatomy, importance of early detection/BSE/MMG/screening procedures/treatment options. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. A 45 min session in the form of slide show + handouts. |

|

| Gondek et al., 2015 [58] | Content: BC statistics/risk factors, signs, symptoms of BC/myths of BC/methods of BCS (BSE, CBE, MMG). Method of delivery: Spoken. A health educator and/or project director delivered educational sessions. A 60–90 min breast health education program, evidence-informed, and community-based culturally competent. Session delivered in multiple languages, in the form of presentations/interactive breast model session/local BC survivor speaks about her personal experiences/a female physician to answer participants questions/women aged 40 years or older who were not currently practicing BCS were contacted and proposed one-on-one navigation assistance in completing BCS. |

|

| Ouyang and Hu, 2014 [62] | Content: Prevalence, characteristics, risk factors, and signs of BC/early detection methods/healthy diet and exercise guidance/importance and benefit of BSE/technique of BSE. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. The intervention delivered by the study researcher consisted of 1 h (20 min educational session, 30 min BSE training, 10 min discussion), in the form of PPT presentation/pictures/BSE color images/BSE diagrams/videos/booklet and shower card/monthly telephone follow-up. |

|

| Seven et al., 2014 [60] | Content: Both brochures provided information on BC early signs and symptoms, risk factors/importance of BSE, CBE, MMG/current recommendations on BSE, CBE, MMG. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. The primary investigator delivered the intervention in the participants’ homes. Individual education: Each participant received a one-on-one education + educational brochure. Individual education and husband brochure Each woman received one-on-one training and two educational brochures; one for her and another for her husband. Group education Some 60–90-min-long educational sessions + educational brochure/women invited to participate in free BCS services. |

|

| Tuzcu et al., 2016 [10] | Content: Breast anatomy/incidence, mortality rate, risk factors of BC/changes in the breast/BSE, CBE, MMG/instructions on doing BSE/importance of screening methods/susceptibility/benefits, barriers, confidence/benefits, barriers of MMG. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. One hour, 10-week-long training in groups of 8–12 individuals delivered by study team members, in the form of 20 min PPT for visual images/15 min film about BSE/20 min BSE training on a breast model/10 min delivery and explanation of the reminder cards/telephone consultations/telephone calls reminders in the 3rd month/invitation card for free MMG/screening behaviors cards. Control: Usual care. After the post-test, study team offered one-to-one education on BCS and reminder cards (BSE card, BCS approaches card) to the control group. |

|

| Vasishta et al., 2018 [63] | Content: Anatomy and physiology of the breast/risk factors for BC/steps and importance of BSE. Method of delivery: Spoken, through PPT. |

|

| Wu and Lin, 2016 [56] | Content for the intervention group: Knowledge of BC/risk factors/MMG screening guidelines/perceived barrier, benefits and self-efficacy. Content for the control group: MMG brochure on breast health. Method of delivery: Spoken/written materials. Individual telephone counseling delivered by research investigators, through 1 h telephone calls interview/application (computer program). Control: Brochure. |

|

The intervention methods of delivery varied across studies, where 19 studies reported multiple strategies in delivering the interventions, such as PowerPoint presentation (PPT), group discussion, video demonstration, training, relevant images, cards, and brochures [9,10,16,19,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Three studies delivered the interventions by a single strategy, either by PPT [11,63] or video demonstration [55].

Besides that, a total of 13 studies reported that the researcher(s) or main investigator(s) personally delivered the interventions [10,11,16,35,47,49,50,52,56,57,59,60,62]. Meanwhile, Gondek et al. [58] reported that a project director and/or health educator led the program delivery whereas Goel and O’Conor [55] reported that healthcare providers delivered the intervention. On the other hand, community healthcare workers provided the intervention in Elder et al. [54], while Mirmoammadi et al. [51] reported that a consultant delivered the intervention. In another study, Fathollahi-Dehkordi and Farajzadegan reported that a peer educator delivered the intervention [48]. However, four studies did not specify who delivered the intervention [9,19,61,63].

Other relevant strategies were also incorporated to handle the participants’ needs, which included the involvement of peer support (n = 1) [52], BC survivors (n = 2) [52,58], spouses (n = 1) [60], and female physicians (n = 1) [58] in the intervention. Furthermore, a personally and culturally tailored delivery was employed in four studies [9,53,57,60] and individual consultation was employed in five studies [10,51,53,56,57].

4. Outcome Measures and Study Results

Most of these studies assessed the effectiveness of the programs by measuring all three outcomes (i.e., BCS uptake, knowledge of BC, and beliefs about BC) (n = 14). Eight studies assessed the effectiveness of the programs by measuring only one or two outcomes from: (1) screening uptake (n = 1) [9]; (2) knowledge (n = 2) [61,63]; (3) knowledge and screening uptake (n = 1) [58]; (4) knowledge and beliefs (n = 1) [53]; (5) beliefs and screening uptake (n = 3) [10,52,57]. The common variables reported at baseline were age (in all studies), marital status (in all studies, except four studies [53,55,58,59]), educational level (in all studies, except one study [53]), and income (in 11 studies [9,10,16,48,52,54,55,56,57,59,62]). The family history of BC was reported in 10 studies [9,16,48,49,50,52,57,59,61,62]. Only one study did not specify any baseline variables [63]. Focusing on outcome measures, Table 3 displays the effects of the interventions, and Table 4 displays the details of the instruments.

Table 4.

Instrument details.

| Study and Outcome Measures | Data Collection Periods | Method of Evaluation and Content of Instrument | Psychometric Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

Akhtari Zavare et al., 2016 [16]

|

|

|

|

Heydari and Noroozi, 2015 [49]

|

|

|

|

Eskandari-Torbaghan et al., 2014 [47]

|

|

|

Accepted items had content validity ratio larger than 0.62 and content validity indices larger 0.79. Cranach’s alpha = 0.76. |

Goel and O’Conor, 2016 [55]

|

|

|

Psychometric properties were not reported. |

Kocaoz et al., 2017 [59]

|

|

|

|

Elder et al., 2017 [54]

|

|

|

Psychometric properties were not reported. |

Yilmaz et al., 2017 [11]

|

|

|

|

Freund et al., 2017 [9]

|

|

A telephone questionnaire of 22 items that included questions on socio-demographic factors, questions on adherence to MMG, CBE, and BSE screening, and questions on cultural health beliefs. |

|

Mirmoammadi et al., 2018 [51]

|

|

|

|

Khiyali et al., 2017 [50]

|

|

|

|

Masoudiyekta et al., 2018 [19]

|

|

|

|

Lee-Lin et al., 2015b [53]

|

|

|

|

Fathollahi-Dehkordi and Farajzadegan, 2018 [48]

|

|

|

Cronbach’s alpha for sensitivity = 0.82, severity = 0.84, barriers = 0.73, benefits = 0.72, and health motivation = 0.77. |

Taymoori et al., 2015 [52]

|

|

|

|

Rabbani et al., 2019 [61]

|

|

|

Psychometric properties were not reported. |

Gondek et al., 2015 [58]

|

|

|

Psychometric properties were not reported. |

Ouyang and Hu, 2014 [62]

|

|

|

|

Seven et al., 2014 [60]

|

|

|

|

Tuzcu et al., 2016 [10]

|

|

|

|

Vasishta et al., 2018 [63]

|

|

|

Tests of validity and reliability were conducted, but details of the psychometric properties were not reported in the article. |

Lee-Lin et al., 2015a [57]

|

|

Self-report questionnaire. | |

Wu and Lin, 2016 [56]

|

|

Self-report questionnaire. |

4.1. Breast Cancer Screening Uptake

A total of 18 studies employed different methods to assess the participants’ BCS uptake and revealed conflicting results. Apart from the self-reporting found in six studies [16,49,52,55,56,57], Taymoori et al. [52] and Goel and O’Conor [55] used medical reports and review charts. On the other hand, 12 other studies used different questionnaires to evaluate the participants’ BCS uptake [9,10,19,47,48,50,51,54,57,58,59,60,62].

Meanwhile, seven studies that explored the practice of BSE among women reported consistent results. There were five experimental studies that involved two groups [9,10,16,19,50] and revealed higher BSE among the participants in the intervention group, as compared to the participants in the control group (p < 0.05), after the intervention. Likewise, two pre–post studies found a significant improvement in the rate of BSE performance among the participants after the intervention [59,62]. However, six studies on the CBE uptake reported conflicting results. Freund et al. [9] and Masoudiyekta et al. [19] did not find any significant difference between the two groups after the interventions (p > 0.05), while four other studies showed that the intervention groups recorded significant levels of CBE performance, as compared to the control groups (p < 0.05) [10,48,51,54].

Additionally, a total of 13 studies assessed the changes in MMG uptake among the participants after they received education but reported contradictory results. Five studies revealed that the MMG uptake improved significantly among women in the intervention group after they received education, as compared to those in the control group (p < 0.05) [10,19,51,54,55]. In another study, Taymoori et al. [52] found that, after adjusting for marital status and healthcare centers, the participants of HBM (AOR = 5.11, CI = 2.26–11.52, p < 0.001) and TPB (AOR = 6.58, CI = 2.80–15.47, p < 0.001) groups were five and six times more likely, respectively, to obtain MMG relative to the participants of control groups. Likewise, Lee-Lin et al. in 2015a [57] revealed that, after controlling for age, marital status, and age when participants moved to the United States, women in the intervention group were nine times more likely to complete MMG than women in the control group (AOR = 9.10, CI = 3.50–23.62, p < 0.001). Wu and Lin [56] further implemented a sub-group analysis of age, length of residence in the United States, and insurance status to evaluate the intervention’s effect on MMG uptake. A significant difference between groups was observed in participants with insurance coverage for MMG (56% in the intervention group versus 34% in the control group) (p = 0.03) and elderly women (65 years or older) (51% in the intervention group versus 25% in the control group).

When it comes to comparing different educational interventions, Heydari and Noroozi [49] showed that, after the intervention, 80% of the participants in group training and 33% of the participants in the multimedia group practiced MMG (p = 0.003). Meanwhile, Seven et al. [60] did not find any statistically significant difference in the screening rate among the three methods of education (p = 0.067). However, women who were involved in a group had a higher rate of MMG screening than women who were educated individually (p = 0.034).

As for the ultra-Orthodox Jewish group, Freund et al. [9] found a significantly greater number of women from the intervention group performed MMG screening (p = 0.009) after the intervention, as compared to the non-intervention group. On the other hand, when it came to the Arab population group, there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups (p > 0.05). Apart from that, Gondek et al. [58] and Kocaöz et al. [59] employed a pre–post study design and reported that 33.0% and 28.4% of women in the respective post-intervention assessment completed MMG. The scores of BC behaviors were found to significantly improve among women in the intervention group, as compared to women in the control group, after the intervention (p < 0.05) [47].

4.2. Knowledge of Breast Cancer and Breast Cancer Screening

A total of 16 studies reported contradictory results on the changes in BC and BCS knowledge levels among the participants (before and after intervention). Different tools were used to evaluate the knowledge levels, where higher scores indicate greater knowledge. There were five studies that used valid and reliable knowledge tests [16,47,50,61,63]. Three studies reported that the participants in the intervention group recorded significantly higher knowledge scores than those in the control group [16,47,50]. Likewise, Vasishta et al. [63] and Rabbani et al. [61] employed pre–post study designs and observed a significant increase in BC knowledge (between the pre- and post-intervention).

Meanwhile, six studies reported on either the validity or reliability of the knowledge tests [19,49,51,53,60,62]. Although the knowledge scores of both intervention and control groups in the post-test in a study by Heydari and Noroozi [49] showed a significant increase (p < 0.001), no significant difference in the knowledge scores between both groups was reported (p = 0.128). Likewise, Seven et al. [60] reported a statistically significant improvement in the knowledge mean scores after intervention for each group of the three methods of education (p < 0.001) but no significant difference in the knowledge mean scores among the three groups (p > 0.05). Three studies showed that, after the intervention, the knowledge scores of the intervention group were significantly higher than that of the control group [19,51,53]. In addition, the participants’ knowledge scores in a study by Ouyang and Hu [62] increased significantly after the intervention (p < 0.013).

Besides that, five more studies assessed changes in the knowledge level but the psychometric properties of the instruments used in these studies were not reported [11,48,54,55,58]. Fathollahi-Dehkordi and Farajzadegan [48] showed a significant mean difference in the knowledge scores between the control and intervention groups following the intervention (p < 0.001). However, Goel and O’Conor [55] and Elder et al. [54] reported no significant differences in the knowledge scores of both groups after education (p > 0.05). Nevertheless, Goel and O’Conor [55] reported a significantly higher knowledge score among the participants in the intervention group (p = 0.04). Gondek et al. [58] and Yılmaz et al. [11] employed the pre–post study design and detected a significant improvement in the knowledge mean scores from the pre-test assessment to the post-test assessment (p < 0.05).

4.3. Health beliefs of Breast Cancer and Breast Cancer Screening

Inconsistent results were reported on modifications in the beliefs about BC and BCS (n = 15). A total of 14 studies applied the standard validated Champion’s HBM scale in different languages [10,11,16,19,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,59,60,62] using only certain model subscales or all model subscales to assess the changes in the health beliefs about BC and BCS, which are as follows: (1) perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers [53]; (2) perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and health motivation [48,49,60]; (3) perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy [19,47,50,52,62]; (4) perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, health motivation, and self-efficacy [10,11,16,51,59].

For instance, Lee-Lin et al. in 2015b [53] found that women in the education group recorded higher perceived susceptibility (p < 0.01) and lower perceived barriers to BC (p < 0.05) in the post-intervention than the control group. In another study, Heydari and Noroozi [49] found a significant decrease in the perceived barriers for both groups following the intervention (p < 0.05). As for the education group, health motivation (p = 0.01) and perceived benefits of MMG (p = 0.003) were found higher in the post-test but no statistically significant differences were reported in the multimedia group regarding perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits of MMG, and health motivation (p > 0.05). Conversely, the comparison of both education and multimedia groups showed no changes in the perceived barriers, perceived susceptibility, and perceived severity subscales (p > 0.05) but health motivation (p = 0.04) and perceived benefits (p = 0.029) were found higher in the education group as compared to the multimedia group.

Adding to that, Fathollahi-Dehkordi and Farajzadegan [48] found that all constructs of health beliefs were significantly impacted by time and time–group interaction (p < 0.001). The effect of the group factor was found to be significantly associated with perceived sensitivity, perceived benefits, and health motivation subscales (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, Seven et al. [60] reported no significant differences among the three educational groups in the scores of all subscales of health beliefs before and after education (p > 0.05), except for the scores of the health motivation subscale. Eskandari-Torbaghan et al. [47] found that, after the intervention, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers improved significantly among women in the intervention group, as compared to women in the control group (p < 0.05). However, no statistically significant differences between both groups for the subscales of perceived seriousness and self-efficacy (p > 0.05) were reported.

Two studies revealed an increase in the mean scores for all HBM constructs for the experimental group, as compared to the control group, after the intervention (p < 0.05) [19,50]. Ouyang and Hu [62] employed a pre–post study design and found significant improvement in the perceived benefits, confidence, and perceived seriousness among the participants after the intervention (p < 0.05). However, no statistically significant differences for perceived susceptibility and perceived barriers (p > 0.05) were observed. The participants demonstrated substantial changes in all HBM and TPB constructs (p < 0.05) [52].

On the other hand, Akhtari-Zavare et al. [16] reported that the intervention group recorded significant changes in the scores of perceived benefits of BSE (p < 0.001), perceived barriers of BSE (p < 0.01), the confidence of doing BSE (p < 0.001), and total health beliefs (p = 0.04) after education compared to the control group. However, the study found no significant differences between the intervention and control groups for the remaining components (p > 0.05). On the other hand, Kocaöz et al. [59] reported significant improvements in health motivation (p = 0.03), perceived barriers of BSE (p = 0.007), confidence of doing BSE (p < 0.0001), perceived benefits of MMG (p = 0.008), and perceived barriers of MMG (p = 0.001) after the intervention. No significant improvement in perceived susceptibility, perceived seriousness, and perceived benefits of BSE (p > 0.05) was found.

In another study, Mirmoammadi et al. [51] found that the post-intervention assessment detected significant changes in the HBM constructs (p < 0.05) between the intervention and control groups, except for perceived susceptibility and perceived severity (p > 0.05). Tuzcu et al. [10] also found higher perceived susceptibility (p = 0.04), health motivation (p < 0.001), perceived benefits of BSE (p < 0.001), and self-efficacy (p < 0.001) but lower perceived barriers of BSE and MMG (p < 0.001) in the intervention group compared to the control group after education. The study also reported no significant differences in perceived seriousness (p = 0.400) and perceived benefits of MMG (p = 0.137) after education.

Furthermore, adopting a pre–post study design, Yılmaz et al. [11] found that the mean scores of all HBM subscales improved significantly (p < 0.05). Using the 1990 Tampa survey items [54], the cancer screening group recorded significantly lower scores in perceived barriers, as compared to the physical activity group (p = 0.008).

5. Discussion

The continuous increase of BC among women has prompted researchers to propose different educational interventions to improve knowledge and beliefs about BC and BCS and subsequently, promote BCS uptake among women. The current systematic review focused on published intervention studies to assess the effects of these programs on BCS uptake, knowledge, and beliefs and to provide information on the characteristics of these interventions.

A standardized and validated instrument, namely the HBM scale developed by Champion [64] and Champion [65], was found to be commonly used by studies to assess health beliefs. However, different instruments were used by these studies to measure the knowledge, beliefs, and screening uptake of BC. Although self-reporting is an easier means to evaluate the BCS uptake, over-reporting may occur. Women may give socially desirable responses, rather than revealing their actual practice [42]. A medical report is believed to be a reliable method in terms of data accuracy to verify the BCS uptake accuracy. However, retrieving these records can be rather difficult.

Meanwhile, a linguistically convenient approach is commonly adopted as an effective intervention strategy to promote understanding among women. Multiple health models and theories (HBM, EM, HPM, SCT, TTM, and TPB), which were adopted in most of these studies, revealed health beliefs, knowledge of BC, and screening as mediators as well as the final target screening behavior. Hence, no positive behavior may take place without addressing and observing these mediators properly during the intervention design. In this systematic review, secondary outcome variables (knowledge and health beliefs about BC and BCS) were included since one or a combination of these variables can potentially affect the screening uptake change. Most of these studies found that HBM-based educational interventions successfully improved screening rates. Similar findings were reported in another review based in Turkey [40]. The current review is consistent with the previous review that explored the efficiency of theory-based interventions in elevating the BCS uptake [38].

Furthermore, most of the studies revealed favorable outcomes after the educational intervention, which were in line with another review by Agide et al. [21]. The reviewed studies used either single or multiple health behavior models or theories to improve BCS uptake, where the approach of multiple models appears to be more efficient in meeting the multidimensional needs of women [10,48,52,57]. These findings are consistent with the previous systematic reviews conducted by Naz et al. [38] and Secginli et al. [40]. Furthermore, the intervention content plays an essential role in achieving the target outcome. The current review provides detailed information on intervention content, which is consistent with previous work by Chan and So [42].

Suitable instrument selection to measure outcomes can assist in producing high-quality data. The adoption of the same instrument can help to facilitate comparisons of these studies. The variation in the instrument content may create difficulties in comparing these studies. Moreover, certain studies did not report the reliability and/or validity of their instruments, which makes the quality of their data questionable. Thus, the interpretation of the findings must be taken with caution.

Nonetheless, the strength of this systematic review is the inclusion of experimental studies that were conducted in high- and middle-income countries. However, several limitations of this systematic review are also identified. Firstly, only published articles from 2014 to 2019 were gathered for the review. Secondly, the variation in the study designs and methods utilized in the included studies made pooling of results impossible. Thirdly, the variation in the follow-up length in these studies also limited the ability to compare the efficiency of interventions across studies. Apart from the varying validity and reliability of instruments used, the use of different instruments to assess outcomes was also another limitation.

6. Conclusions

Despite the observed improvements in women’s knowledge, beliefs, and screening practices following educational interventions, the current systematic review revealed a difficulty in proving the effectiveness of such programs given the inconsistencies in the reported findings. These discrepancies imply the need for more research. The implementation of a future comprehensive program that links the most effective intervention characteristics, mediators, and factors that influence BCS outcomes is suggested. Additionally, the discussed findings of this review present significant implications for researchers, healthcare workers, and intervention planners to produce BCS health educational interventions that target women. The knowledge obtained from this review can be used to design comprehensive BCS programs, which can help to strengthen the existing healthcare systems with the purpose of disseminating proper knowledge to wider communities.

7. Recommendations

As a result of the current systematic review, we present several significant recommendations on the development of educational interventions for higher BCS uptake. Firstly, it is recommended for future research to comprehensively examine educational interventions in order to provide strong evidence on their effectiveness. Additionally, to produce high-quality data, more reliable resources to evaluate screening practices are recommended, such as medical reports and the use of standardized validated instruments, such as the CHBM scales to assess health beliefs, rather than relying on questionnaires.

Furthermore, we recommend the implementation of theoretically based interventions to promote women’s BCS behaviors. Theoretical and model-based programs are more successful than programs that are not based on theories or models since these programs are based on an accurate understanding of the health behavior mechanism changes which result in successful plans. Moreover, we suggest that the multiple model based educational intervention approach is to be utilized as guidance for interventions to understand the cultural and psychosocial factors that influence BCS behaviors. Educational interventions that employ a multiple models method have been found to be more effective in meeting women’s’ multidimensional needs [52]. Such models account for social, cultural, and economic barriers which may promote women’s health beliefs.

Besides that, the intervention content should include key messages on knowledge and beliefs related to BC and BCS, and information on the importance and effectiveness of screening tests. Moreover, the intervention programs with the use of live demonstration (such as videos and printed materials) can be implemented individually or with in-group sessions by healthcare providers or lay instructors. Powerful and well-designed RCTs that provide a detailed description of the study and intervention are necessary.

Acknowledgments

We would like to forward great and deepest gratitude to Bilal Bahaa Zaidan and Abdullah Hussein Abdullah Al-Amoodi for their assistance and guidance in the design of the search strategy and the screening process.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/1/263/s1. Table S1: PRISMA checklist; Table S2: Search strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N. and H.A.R., data curation: S.N. and M.A.; formal analysis: S.N., H.K.S., M.A. and M.A.A.-J.; investigation: S.N., H.K.S., H.A.R. and S.I.; methodology: S.N., H.K.S., H.A.R., S.I., M.A. and M.A.A.-J.; project administration: S.N.; supervision: S.N., H.K.S. and H.A.R.; validation: S.N., H.A.R. and M.A.; writing—original draft: S.N. and H.A.R.; writing—review and editing: S.N., H.A.R., H.K.S., S.I., M.A. and M.A.A.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferly J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre L.A., Islami F., Siegel R.L., Ward E.M., Jemal A. Global Cancer in Women: Burden and Trends. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;26:444–457. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Youlden D.R., Cramb S.M., Yip C.H., Baade P.D. Incidence and Mortality of Female Breast Cancer in the Asia-Pacific Region. Cancer Biol. Med. 2014;11:101–115. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2015–2016. American Cancer Society, Inc.; Atlanta, GA, USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R., Miller K., Jemal A. Cancer Statistics 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Breast Cancer. [(accessed on 29 December 2018)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/breast-cancer/en/

- 7.Smith R.A., Andrews K.S., Brooks D., Fedewa S.A., Manassaram-Baptiste D., Saslow D. Cancer Screening in the United States, 2018: A Review of Current American Cancer Society Guidelines and Current Issues in Cancer Screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:297–316. doi: 10.3322/caac.21446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Sakkaf K.A., Basaleem H.O. Breast Cancer Knowledge, Perception and Breast Self- Examination Practices among Yemeni Women: An Application of the Health Belief Model. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016;17:1463–1467. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.3.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freund A., Cohen M., Azaiza F. A Culturally Tailored Intervention for Promoting Breast Cancer Screening among Women from Faith-Based Communities in Israel: A Randomized Controlled Study. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2017;29:375–388. doi: 10.1177/1049731517741197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuzcu A., Bahar Z., Gözüm S. Effects of Interventions Based on Health Behavior Models on Breast Cancer Screening Behaviors of Migrant Women in Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:40–50. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yılmaz M., Sayın Y., Cengiz H.Ö. The Effects of Training on Knowledge and Beliefs about Breast Cancer and Early Diagnosis Methods among Women. Eur. J. Breast Health. 2017;13:175–182. doi: 10.5152/tjbh.2017.3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed B.A. Awareness and Practice of Breast Cancer and Breast-Self Examination among University Students in Yemen. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2010;11:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bawazir A., Bashateh N., Jradi H., Breik A.B. Breast Cancer Screening Awareness and Practices among Women Attending Primary Health Care Centers an the Ghail Bawazir District of Yemen. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2019;19:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Champion V., Menon U. Predicting Mammography and Breast Self- Examination in African American Women. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20:315–322. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temel A.B., Dağhan Ş., Kaymakçı Ş., Dönmez R.Ö., Arabacı Z. Effect Of Structured Training Programme on the Knowledge and Behaviors of Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening among the Female Teachers in Turkey. BMC Women’s Health. 2017;17:123. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0478-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akhtari-Zavare M., Juni M.H., Said S.M., Ismail I.Z., Latiff L.A., Eshkoor S.A. Result of Randomized Control Trial to Increase Breast Health Awareness among Young Females in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:738. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3414-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alice T.E., Philomena O. Breast Self-Examination among Secondary School Teachers in South-South, Nigeria: A Survey of Perception and Practice. JPHE. 2014;6:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alameer A., Mahfouz M.S., Alamir Y., Ali N., Darraj A. Effect of Health Education on Female Teachers’ Knowledge and Practices Regarding Early Breast Cancer Detection and Screening in the Jazan Area: A Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Cancer Educ. 2019;34:865–870. doi: 10.1007/s13187-018-1386-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masoudiyekta L., Rezaei-Bayatiyani H., Dashtbozorgi B., Gheibizadeh M., Malehi A.S., Moradi M. Effect of Education Based on Health Belief Model on the Behavior of Breast Cancer Screening in Women. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018;5:114–120. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_36_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebell M.H., Thai T.N., Royalty K.J. Cancer Screening Recommendations: An International Comparison of High Income Countries. Public Health Rev. 2018;39:7. doi: 10.1186/s40985-018-0080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agide F.D., Sadeghi R., Garmaroudi G., Tigabu B.M. A Systematic Review of Health Promotion Interventions to Increase Breast Cancer Screening Uptake: From the Last 12 Years. Eur. J. Public Health. 2018;28:1149–1155. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marzo R.R., Salam A. Teachers’ Knowledge, Beliefs and Practices of Breast Self-Examination in a City of Philippine: A Most Cost-Effective Tool for Early Detection of Breast Cancer. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2016;6:16–21. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2016.60203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alabi M.A., Abubakar A., Olowokere T., Okeyode A.A., Mustapha K., Ayoola S.A. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Breast Self- Examination among Female Teachers from Selected Secondary Schools in Ogbomosho, Oyo State. Niger. J. Exp. Clin. Biosci. 2018;6:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenstock I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974;2:328–335. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conner M., Norman P. Predicting Health Behaviour. 2nd ed. Open University Press. Maidenhead; Berkshire, UK: 2005. pp. 28–80. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawal O., Murphy F., Hogg P., Nightingale J. Health Behavioural Theories and Their Application to Women’s Participation in Mammography Screening. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2017;48:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmadian M., Samah A.A. Application of Health Behavior Theories to Breast Cancer Screening among Asian Women. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013;14:4005–4013. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.7.4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ersin F., Gözükara F., Polat P., Erçetin G., Bozkurt M.E. Determining the Health Beliefs and Breast Cancer Fear Levels of Women Regarding Mammography. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2015;45:775–781. doi: 10.3906/sag-1406-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serra Y.A., Colón-López V., Savas L.S., Vernon S.W., Fernández-Espada N., Vélez C., Ayala A., Fernández M.E. Using Intervention Mapping to Develop Health Education Components to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening in Puerto Rico. Front. Public Health. 2017;5:324. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J., Wang J., Pang T.W.Y., Chan M.K.Y., Leung S., Chen X., Leung C., Zheng Z.J., Wong M.C.S. Does Theory of Planned Behaviour Play a Role in Predicting Uptake of Colorectal Cancer Screening? A Cross-Sectional Study in Hong Kong. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e037619. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau J., Lim T.Z., Wong G.J., Tan K.K. The Health Belief Model and Colorectal Cancer Screening in the General Population: A Systematic Review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020;20:101223. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roncancio A.M., Ward K.K., Sanchez I.A., Cano M.A., Byrd T.L., Vernon S.W., Fernandez-Esquer M.E., Fernandez M.E. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Cervical Cancer Screening among Latinas. Health Educ. Behav. 2015;42:621–626. doi: 10.1177/1090198115571364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abamecha F., Tena A., Kiros G. Psychographic Predictors of Intention to Use Cervical Cancer Screening Services among Women Attending Maternal and Child Health Services in Southern Ethiopia: The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) Perspective. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:434. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6745-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shida J., Kuwana K., Takahashi K. Behavioral Intention to Prevent Cervical Cancer and Related Factors among Female High School Students in Japan. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018;15:375–388. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aldohaian A.I., Alshammari S.A., Arafah D.M. Using the Health Belief Model to Assess Beliefs and Behaviors Regarding Cervical Cancer Screening among Saudi Women: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19:6. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0701-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zare M., Ghodsbin F., Jahanbin I., Ariafar A., Keshavarzi S., Izadi T. The Effect of Health Belief Model-Based Education on Knowledge and Prostate Cancer Screening Behaviors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery. 2016;4:57–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bashirian S., Barati M., Mohammadi Y., Moaddabshoar L., Dogonchi M. An Application of the Protection Motivation Theory to Predict Breast Self-Examination Behavior among Female Healthcare Workers. Eur. J. Public Healt. 2019;15:90–97. doi: 10.5152/ejbh.2019.4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naz M.S.G., Simbar M., Fakari F.R., Ghasemi V. Effects of Model-Based Interventions on Breast Cancer Screening Behavior of Women: A Systematic Review. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018;19:2031–2041. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.8.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Copeland V.C., Kim Y.J., Eack S.M. Effectiveness of Interventions for Breast Cancer Screening in African American Women: A Meta-Analysis. Health Serv. Res. 2018;53:3170–3188. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Secginli S., Nahcivan N.O., Gunes G., Fernandez R. Interventions Promoting Breast Cancer Screening among Turkish Women with Global Implications: A Systematic Review. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2017;14:316–323. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donnelly T.T., Hwang J. Breast Cancer Screening Interventions for Arabic Women: A Literature Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 2015;17:925–939. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9902-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan D.N., So W.K. A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials Examining the Effectiveness of Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Interventions for Ethnic Minority Women. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015;19:536–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan T.M., Leong J., Ming L.C., Khan A.H. Association of Knowledge and Cultural Perceptions of Malaysian Women with Delay in Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015;16:5349–5357. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.13.5349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Mahony M., Comber H., Fitzgerald T., Corrigan M.A., Fitzgerald E., Grunfeld E.A., Flynn M.G., Hegarty J. Interventions for Raising Breast Cancer Awareness in Women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011396.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armijo-Olivo S., Stiles C.A., Hagen N.D., Biondo P., Cummings G. Assessment of Study Quality for Systematic Reviews: A Comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological Research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012;18:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas B., Ciliska D., Dobbins M., Micucci S. A Process for Systematically Reviewing the Literature: Providing the Research Evidence for Public Health Nursing Interventions. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eskandari-Torbaghan A., Kalan-Farmanfarma K., Ansari-Moghaddam A., Zarei Z. Improving Breast Cancer Preventive Behavior among Female Medical Staff: The Use of Educational Intervention Based on Health Belief Model. MJMS. 2014;21:44–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fathollahi-Dehkordi F., Farajzadegan Z. Health Education Models Application by Peer Group for Improving Breast Cancer Screening among Iranian Women with a Family History of Breast Cancer: A Randomized Control Trial. MJIRI. 2018;32:51. doi: 10.14196/mjiri.32.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heydari E., Noroozi A. Comparison of Two Different Educational Methods for Teachers’ Mammography Based on the Health Belief Model. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015;16:6981–6986. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.16.6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khiyali Z., Aliyan F., Kashfi S.H., Mansourian M., Jeihooni A.K. Educational Intervention on Breast Self-Examination Behavior in Women Referred to Health Centers: Application of Health Belief Model. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017;18:2833–2838. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.10.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mirmoammadi A., Parsa P., Khodakarami B., Roshanaei G. Effect of Consultation on Adherence to Clinical Breast Examination and Mammography in Iranian Women: A Randomized Control Trial. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018;19:3443–3449. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2018.19.12.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taymoori P., Molina Y., Roshani D. Effects of a Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase Repeat Mammography Screening in Iranian Women. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:288–296. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee-Lin F., Pedhiwala N., Nguyen T., Menon U. Breast Health Intervention Effects on Knowledge and Beliefs over Time among Chinese American Immigrants—A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Cancer Educ. 2015;30:482–489. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elder J., Haughton J., Perez L., Martínez M., De la Torre C., Slymen D.J., Arredondo E.M. Promoting Cancer Screening among Churchgoing Latinas: Fe En Accion/Faith in Action. Health Educ. Res. 2017;32:163–173. doi: 10.1093/her/cyx033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goel M.S., O’Conor R. Increasing Screening Mammography among Predominantly Spanish Speakers at a Federally Qualified Health Center Using a Brief Previsit Video. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016;99:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu T.-Y., Lin C. Developing and Evaluating an Individually-Tailored Intervention to Increase Mammography Adherence among Chinese American Women. Cancer Nurs. 2016;38:40–49. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee-Lin F., Nguyen T., Pedhiwala N., Dieckmann N., Menon U. A Breast Health Educational Program for Chinese-American Women: 3-To 12-Month Post intervention Effect. Am. J. Health Promot. 2015;29:173–181. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130228-QUAN-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gondek M., Shogan M., Saad-Harfouche F.G., Rodriguez E.M., Erwin D.O., Griswold K., Mahoney M.C. Engaging Immigrant and Refugee Women in Breast Health Education. J. Cancer Educ. 2015;30:593–598. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0751-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kocaöz S., Özçelik H., Talas M.S., Akkaya F., Özkul F., Kurtuluş A., Ünlü F. The Effect of Education on the Early Diagnosis of Breast and Cervix Cancer on the Women’s Attitudes and Behaviors Regarding Participating in Screening Programs. J. Cancer Educ. 2017;33:821–832. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seven M., Akyüz A., Robertson L.B. Interventional Education Methods for Increasing Women’s Participation in Breast Cancer Screening Program. J. Cancer Educ. 2014;30:244–252. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0709-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rabbani S.A., Al Marzooqi A.M.S.K., Srouji A.E.M., Hamad E.A., Mahtab A. Impact of Community-Based Educational Intervention on Breast Cancer and its Screening Awareness among Arab Women in The United Arab Emirates. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2019;7:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2019.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ouyang Y.Q., Hu X. The Effect of Breast Cancer Health Education on the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice: A Community Health Center Catchment Area. J. Cancer Educ. 2014;29:375–381. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0622-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vasishta S., Ramesh S., Babu S., Ramakrishnegowda A.S. Awareness about Breast Cancer and Outcome of Teaching on Breast Self Examination in Female Degree College Students. India J. Med. Spec. 2018;9:56–59. doi: 10.1016/j.injms.2018.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Champion V.L. Revised Susceptibility, Benefits, and Barriers Scale for Mammography Screening. Res. Nurs. Health. 1999;22:341–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199908)22:4<341::AID-NUR8>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Champion V.L. Instrument Refinement for Breast Cancer Screening Behaviors. Res. Nurs. Health. 1993;42:139–143. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glanz K., Rimer B.K., Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prochaska J.O., Velicer W.F. The Transtheoretical Model of health behavior change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pender N.J., Murdaugh C., Parsons M. The Health Promotion Model. Health Promot. Pract. 2002;4:59–79. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rimer B.K., Glanz K. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kerr J., Rosenberg D.E., Nathan A., Millstein R.A., Carlson J.A., Crist K., Wasilenko K., Bolling K., Castro C.M., Buchner D.M., et al. Applying the Ecological Model of Behavior Change to a Physical Activity Trial in Retirement Communities: Description of the Study Protocol. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2012;33:1180–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the Supplementary Materials.