Abstract

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and most of AD patients suffer from vascular abnormalities and neuroinflammation. There is an urgent need to develop novel blood biomarkers capable of diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) at very early stage. This study was performed to find out new accurate plasma diagnostic biomarkers for AD by investigating a direct relationship between plasma contact system and AD.

Methods

A total 101 of human CSF and plasma samples from normal and AD patients were analyzed. The contact factor activities in plasma were measured with the corresponding specific peptide substrates.

Results

The activities of contact factors (FXIIa, FXIa, plasma kallikrein) and FXa clearly increased and statistically correlated as AD progresses. We present here, for the first time, the FXIIa cut-off scores to as: > 26.3 U/ml for prodromal AD [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.783, p < 0.001] and > 27.2 U/ml for AD dementia (AUC = 0.906, p < 0.001). We also describe the cut-off scores from the ratios of CSF Aβ1–42 versus the contact factors. Of these, the representative ratio cut-off scores of Aβ1–42/FXIIa were to be: < 33.8 for prodromal AD (AUC = 0.965, p < 0.001) and < 27.44 for AD dementia (AUC = 1.0, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The activation of plasma contact system is closely associated with clinical stage of AD, and FXIIa activity as well as the cut-off scores of CSF Aβ1–42/FXIIa can be used as novel accurate diagnostic AD biomarkers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40364-020-00258-5.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Biomarkers, Contact factor, FXIIa, Plasma

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60–80% of all dementia patients. However, the cause of AD is poorly understood and there are no treatments currently available. To date, the only way to take care of AD is to find out in advance the onset and prevent the progression [1, 2]. Over the past decades, there have been many efforts to develop blood biomarkers that can easily and reliably detect the onset of Alzheimer’s, but it has been delayed due to the lack of reproducibility and other problems related to clinical use [3, 4]. Nevertheless, the identification of novel blood biomarkers for predicting and monitoring disease progression that can reliably detect the onset of AD at the early stage is crucial.

AD is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposits in brain [5–7], and most of AD patients suffer from vascular abnormalities [8, 9] and neuroinflammation [10]. Both vascular abnormalities and inflammation can trigger neuronal death; however, the effect of Aβ on these pathologies has not been elucidated. However, a few recent reports have suggested that FXII–initiated contact system can trigger both vascular pathology and inflammation [11], and depletion of coagulation FXII can ameliorate brain pathology and cognitive impairment in AD mice [12].

The plasma contact system, which is composed of the intrinsic pathway of coagulation and the kallikrein-kinin system, plays an essential role in innate immunity [13–15]. Activation of the plasma contact system triggers several cascade systems that involve three serine protease zymogens [factor XII (FXII), factor XI (FXI), and pre-kallikrein (PKK)] and a non-enzymatic cofactor protein [high-molecular weight kininogen (HK)] [13]. The enzymatically active FXIIa activates PKK to plasma kallikrein (PK; KLKB1) that cleaves HK to release the vasoactive and proinflammatory nanopeptide, bradykinin (BK).

Several recent studies have shown a possible relationship between plasma contact system and AD. However, they did not provide any solid evidence, because of their uses of data from a very few human CSF samples or murine models [11, 12, 15–19]. Accordingly, there are still a variety of issues related to contact system and AD, including 1) Is there a close correlation between contact system and AD progression in fact?; and 2) Is it possible to obtain various cut-off scores and certain ratios for distinguishing accurately prodromal AD and AD dementia from normal subjects?

In this study, we addressed these issues and present, for the first time, the direct relationship between the contact system activation and AD progress, and the cut-off scores of FXIIa and CSF Aβ1–42/FXIIa ratio, which are capable of discriminating accurately prodromal AD and AD dementia from normal subjects.

Methods

Study participants

This study was conducted on participants in Gwangju and Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea, from August 2015 to October 2017. All participants in this study provided their written consents, and the study protocol was approved by Chosun University Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB file numbers 2013–12–018-068 and 2016–10–005-009). A total of 101 subjects included in the study were classified into three groups (50 normal elderly people, 23 patients with prodromal AD, and 28 patients with AD dementia) according to the clinical criteria proposed by the IWG-2 guidelines with amyloid PET [16]. However, PET positive group in normal subjects (preclinical stage of AD) and amyloid PET negative group in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) were excluded. Patients with AD dementia met the clinical criteria for Alzheimer’s disease dementia potential proposed by the NIA-AA or IWG-2 working group, and the diagnosis of MCI was also made according to the MCI criteria suggested by the NIA-AA or IWG-2 group [20, 21].

Determination of the concentrations of Aβ1–42, t-Tau, p-Tau181, and bradykinin

The collection and storage of CSF used in this study was performed in the same process as follows [22]. The concentrations of Aβ1–42, t-Tau, and p-Tau181 in CSF were measured using INNOTEST ELISA kit (Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium) and that of bradykinin (BK) was quantitated with Bradykinin ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) according to the protocols provided by the manufacturers.

Measurement of the activities of FXIIa, FXIa, FXa, and PK in plasma

Plasma used in this study was collected and stored from participants according to the Molecular Medicine Ireland (MMI) guidelines for standardized biobanking [23]. To measure and make the standard curves for FXIIa, FXIa, FXa, and PK activities, various concentrations of FXIIa (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 4 U/ml), FXIa (0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 U/ml), FXa (0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 U/ml), and PK (0, 0.02, 0.04, 0.08, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 U/ml) were serially diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.5). After the dilutions, 90 μl each of samples was mixed with 10 μl of corresponding synthetic peptide substrates (S-2302 for FXIIa, S-2366 for FXIa, S-2765 for FXa, and H-D-Val-Leu-Arg-AFC for kallikrein) dissolved in PBS (pH 7.5) at a final concentration of 4 mM and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, during which the increase in absorbance at 405 nm for chromogenic substrates or in fluorescence for fluorogenic substrate (excitation 400 nm/emission 505 nm) was recorded with a 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) as described previously [13]. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Using the data obtained, standard curves for the enzymes were then made using a sigmoidal 4 parameter curve fitting (Supplementary Fig. 1). To validate the measurement method, total 6 plasma samples and 3 different concentrations of contact factors (FXIIa, FXIa, and PK) and FXa were tested over different days.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the three groups (normal, prodromal AD, and AD dementia). Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to analyze the association between the activity of plasma contact system and the typical CSF AD biomarkers. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to calculate areas under the curves (AUCs) to determine the diagnostic abilities of the contact factors and the typical CSF AD biomarkers for prodromal AD and AD dementia. The standard deviations from the mean value of the quantitative analysis or activity of each protein in the cohort used in this study was calculated as the z-score.

Results and discussion

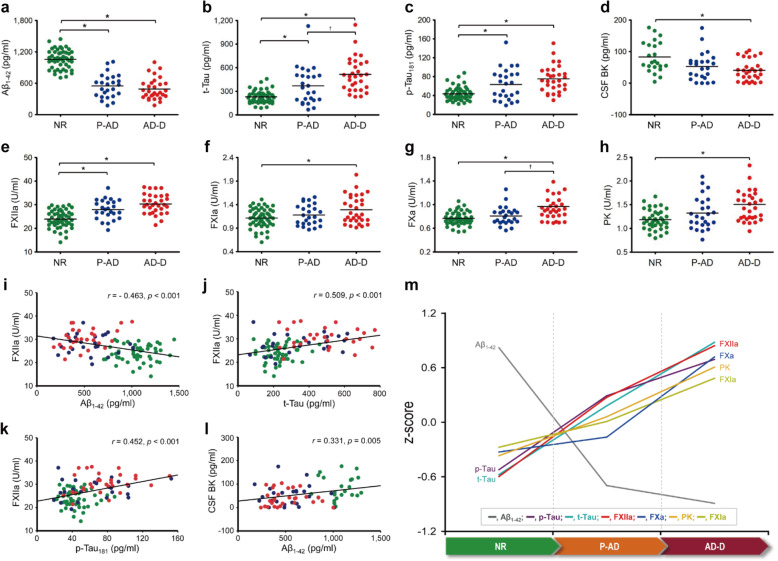

Concentration of CSF biomarkers in AD

The clinical characteristics of total 101 subjects (50 normal subjects, 23 patients with prodromal AD, and 28 patients with AD dementia) and the concentrations of typical AD biomarkers, including Aβ1–42, t-Tau, and p-Tau181 in CSF and contact factors (FXIIa, FXIa, PK, and BK) and FXa in plasma samples are summarized in Table 1. As reported previously [2, 5, 24, 25], Aβ1–42 level in CSF decreased, while t-Tau and p-Tau181 concentrations increased with AD progression (Figs. 1a, c). The concentrations of CSF Aβ1–42 were estimated to be 1059, 550 and 484 pg/ml in normal, prodromal AD, and AD dementia groups, respectively (Table 1). Contrary to these, the levels of t-Tau and p-Tau181 increased as AD progressed, in which the concentrations of t-Tau were found to be 230, 389, and 536 pg/ml, and those of p-Tau181 were 44, 66, and 78 pg/ml in normal, prodromal AD, and AD dementia groups, respectively (Table 1). These results were well in accordance with reported previous studies [2, 24, 25].

Table 1.

Demographic and biochemical characteristics of normal subjects, prodromal AD, and AD dementia

| Demographic data/molecules in CSF or plasma | Total numbers of subjects | Normal | Prodromal AD | AD dementia | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 101 | 50 | 23 | 28 | |

| Age | 101 | 72.0 (6.1) | 71.1 (8.6) | 69.4 (6.0) | 0.262 |

| Years of education | 101 | 9.5 (5.0) | 8.0 (4.7) | 6.70 (3.8) a | 0.033 |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 101 | 26.0 (52.0) | 12 (52.2) | 17.0 (60.7) | 0.736 |

| K-MMSE score | 101 | 26.8 (2.3) | 25.3 (3.9) | 17.9 (5.4) a, b | < 0.001 |

| CDR | 101 | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.0) a | 0.9 (0.4) a, b | < 0.001 |

| CDR sum of boxes | 101 | 0.5 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.6) | 5.1 (2.6) a, b | < 0.001 |

| GDS | 101 | 1.6 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.2) a | 4.1 (0.9) a, b | < 0.001 |

| B-ADL | 101 | 20.0 (0.0) | 20.0 (0.2) | 19.0 (1.8) a, b | < 0.001 |

| I-ADL | 101 | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.22 (0.14) a | 0.63 (0.20) a, b | < 0.001 |

| CSF biomarkers | |||||

| Aβ1–42, pg/ml | 101 | 1,059 (177) | 550 (223) a | 484 (192) a | < 0.001 |

| t-Tau, pg/ml | 101 | 230 (77) | 389 (236) a | 536 (209) a, b | < 0.001 |

| p-Tau181, pg/ml | 101 | 44 (14) | 66 (33) a | 78 (28) a | < 0.001 |

| BK, pg/ml | 72 | 83 (49) | 55 (45) | 39 (33) a | 0.002 |

| Plasma factors | |||||

| FXIIa, U/ml | 101 | 23.90 (3.70) | 28.0 (3.4) a | 30.6 (3.7) a | < 0.001 |

| FXIa, U/ml | 101 | 1.11 (0.21) | 1.18 (0.21) | 1.30 (0.30) a | 0.005 |

| FXa, U/ml | 101 | 0.77 (0.11) | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.97 (0.29) a, b | < 0.001 |

| Kallikrein, U/ml | 101 | 1.20 (0.25) | 1.35 (0.34) | 1.54 (0.39) a | < 0.001 |

| BK, pg/ml | 90 | 13,365 (9,305) | 13,497 (7,945) | 17,679 (21,186) | 0.406 |

Data are presented as mean (± standard deviation) or number (%). Abbreviations: K-MMSE Korean Mini-Mental State Examination, CDR Clinical Dementia Rating, GDS Global Deterioration Scale, B-ADL Barthel Activities of Daily Living, I-ADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, Aβ amyloid beta-protein, t-Tau total Tau protein, p-Tau phosphorylated Tau protein, AD Alzheimer’s disease, BK bradykinin. astatistically significant difference between the indicated group and the normal group; bstatically significant difference between prodromal AD and AD dementia groups

Fig. 1.

Activation of plasma contact factors with clinical stage of AD and correlation strengths between biomarkers. Concentrations of typical AD biomarkers, including Aβ1–42 (a), t-Tau (b), p-Tau181 (c) and BK (d) in CSF were measured from normal (NR), prodromal AD (P-AD), and AD dementia (AD-D) groups by ELISA. The activities of plasma contact factors such as FXIIa (e), FXIa (f), FXa (g), and kallikrein (h) were measured in the presence of 0.4 mM each of corresponding specific synthetic peptide substrates as described in Study design. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for comparisons between the three groups (NR, P-AD, and AD-D). Data are presented as mean values for each group. *: statistically significant difference between the indicated group and the NR; †: statistically significant difference between the P-AD and the AD-D groups. Correlation plots of FXIIa versus Aβ1–42 (i), FXIIa versus t-Tau (j), FXIIa versus p-Tau181 (k), and CSF BK versus Aβ1–42 (l). Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlations between the activity of plasma contact factor and CSF AD biomarker as indicated, in which statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. In panels a to l, cyan, blue, and red colored circles represent NR, P-AD, and AD-D groups, respectively. Dynamics of biomarkers analyzed in AD pathological cascade (m). Lines show z-scores in mean values of normalized biomarker levels for each AD group

Activation of contact system in AD

To measure the activation of the contact system in plasma, the assay validation standard curves were created using the recombinant contact factor (FXIIa, FXIa, and PK) and FXa enzymes. As a result, the R2 values of standard curves were higher than 0.95 (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, the coefficients of variation (CV%) were analyzed to confirm the precision and reproducibility of the measurement method for contact factor activity. As a result, the inter-assay and intra-assay CVs (%) ranged for FXIIa from 3.2 to 4.5% and from 7.2 to 12.7%, which indicated the excellent reproducibility of this method (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of precision and reproducibility

| Biomarker | Sample | U/ml | Intra-assay variation (n = 6) | Inter-assay variation (n = 4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | CV (%) | Mean | SD | CV (%) | |||

| FXIIa | Sample 1 | 0.5 | 0.441 | 0.020 | 4.5 | 0.482 | 0.061 | 12.7 |

| Sample 2 | 1.5 | 1.458 | 0.047 | 3.2 | 1.521 | 0.165 | 10.9 | |

| Sample 3 | 2.5 | 2.469 | 0.091 | 3.7 | 2.668 | 0.193 | 7.2 | |

| FXIa | Sample 1 | 0.05 | 0.058 | 0.002 | 2.6 | 0.053 | 0.006 | 11.7 |

| Sample 2 | 0.1 | 0.095 | 0.004 | 4.2 | 0.100 | 0.010 | 10.1 | |

| Sample 3 | 0.2 | 0.199 | 0.008 | 4.1 | 0.197 | 0.019 | 9.4 | |

| FXa | Sample 1 | 0.1 | 0.103 | 0.010 | 9.4 | 0.103 | 0.010 | 10.2 |

| Sample 2 | 0.2 | 0.200 | 0.011 | 5.5 | 0.196 | 0.017 | 8.9 | |

| Sample 3 | 0.5 | 0.510 | 0.023 | 4.5 | 0.515 | 0.059 | 11.5 | |

| Plasma kallikrein | Sample 1 | 0.1 | 0.125 | 0.004 | 3.0 | 0.110 | 0.012 | 11.3 |

| Sample 2 | 0.2 | 0.191 | 0.013 | 6.9 | 0.190 | 0.017 | 8.8 | |

| Sample 3 | 0.4 | 0.418 | 0.037 | 8.8 | 0.421 | 0.049 | 11.8 | |

Both intra (n=6 replicates) and inter-assay (n=4 assays on different day) precision were determined by comparing the mean of triplicates of three deferent concentrations of samples. The % CV is the standard deviation divided by the mean and multiplied by 100. Abbreviations: SD standard deviation, CV coefficients of variation, FXIIa active coagulation factor XII, FXIa active coagulation factor XI, FXa active coagulation factor X

The enzymatic activities of the plasma contact factors (FXIIa, FXIa, and PK) and FXa clearly increased with AD progression. The enzymatic activities for the normal, prodromal AD, and AD dementia groups were as follows: 23.9, 28.0, and 30.6 U/ml for FXIIa; 1.11, 1.18, and 1.30 U/ml for FXIa; 0.77, 0.81, and 0.97 U/ml for FXa; 1.20, 1.35, and 1.54 U/ml for PK, respectively (Table 1). Taken as a whole, the activities of contact factors (FXIIa, FXIa, or PK) and FXa had a statically difference between the three groups (normal, prodromal AD, and AD dementia groups) (Fig. 1e, h). As for BK, which is a final product of the kallikrein/kinin system [26], its concentration increased in plasma as expected, but rather decreased in CSF with the progression of AD (Table 1; Fig. 1d). The concentrations of BK in plasma were 13,365, 13,497, and 17,679 pg/ml and those in CSF were 83, 55, and 39 pg/ml in normal, prodromal AD, and AD dementia groups, respectively. These results are consistent with the those of recent reports [27] and also seemed to be related, in part, to the fact that BK can evoke blood–brain barrier (BBB) leakage and neuro-inflammation, resulting in CSF BK efflux [15, 28]. All these results suggest that the activation of plasma contact system and AD progression are obviously related, and the activities of contact factors can be used for discriminating prodromal AD and AD from normal groups.

Analysis of correlation between AD biomarker in CSF and contact factor activity in plasma

To examine further the strength of a link between the typical CSF AD biomarkers and the contact factors, we performed correlation analyses (Fig. 1i - l; Supplementary Table 1). As for the typical CSF AD biomarkers, the Pearson’s correlation coefficients of Aβ1–42 versus t-Tau and p-Tau181 were to be - 0.445 and - 0.359, respectively, at their r-values, indicating that these biomarkers are moderately correlated, under the guidelines of correlation strength [29]. In cases of contact factors, the r-values of FXIIa versus FXIa, FXa, and PK were to be 0.8, 0.692, and 0.59, respectively, suggesting that these factors are correlated statistically in significant level (Supplementary Table 1). Prominently, FXIIa was negatively correlated to CSF Aβ1–42 (r = − 0.463) and positively to both t-Tau (r = 0.509) and p-Tau181 (r = 0.452) in all moderate relationships (Fig. 1i - l; Supplementary Table 1). All these results suggest that the activation of contact system is certainly correlated to AD progression as reported previously [17].

The changes in the z-values of typical CSF AD biomarkers and plasma contact factors as AD progresses were also analyzed (Fig. 1m). As expected [5, 12, 16, 30], the z-score of Aβ1–42 decreased, whereas those of t-Tau and p-Tau181 increased in the order of normal, prodromal AD, and AD dementia groups (Fig. 1m). As for plasma contact factors, the scores of FXIIa, FXIa, FXa, and PK noticeably increased (Fig. 1m), whereas CSF BK decreased (data not shown) in the AD pathological cascade. These results strongly suggest that plasma contact system is closely associated with AD progression, and its degree of activation can reflect the disease progression.

Analysis of potential as a plasma biomarker for AD diagnosis

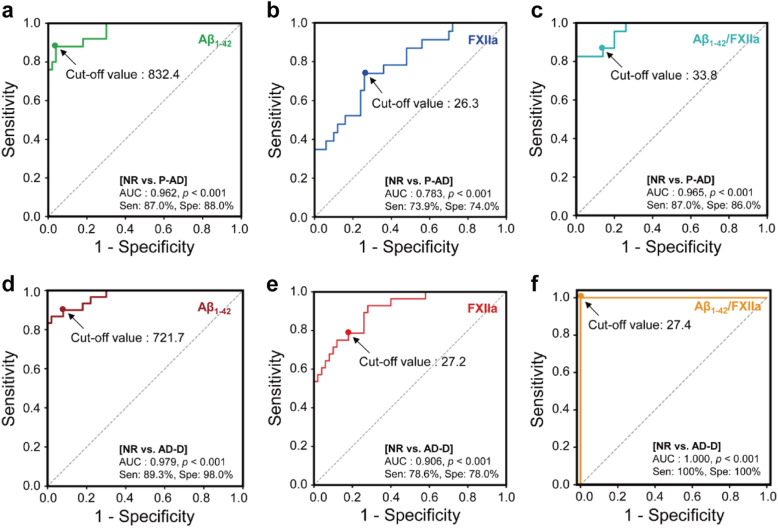

We generated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to analyze the potential of each protein for use as a new biomarker for AD diagnosis (Fig. 2 and Table 3). The ROC curves and the areas under the curves (AUCs) [28, 31] showed that Aβ1–42 can discriminable in highly accurate for both prodromal AD (AUC = 0.962; cut-off value = < 832.4 pg/ml) and AD dementia (AUC = 0.979; cut-off value = < 721.7 pg/ml) from normal (Fig. 2a, d; Table 3). Among the contact factors, only FXIIa seemed to have a capability able to discriminate both prodromal AD (AUC = 0.783; cut-off value = > 26.3 U/ml) and AD dementia (AUC = 0.906; cut-off value = > 27.2 U/ml) from normal (Fig. 2b,e; Table 3). These results indicate that the contact factor FXIIa can be a new plasma biomarker for diagnosing prodromal AD in acceptable and AD dementia in very accurate from normal.

Fig. 2.

Representative cut-off values of contact factors and CSF Aβ1–42/contact factor ratios. Cut-off values of Aβ1–42 (a), FXIIa (b), and CSF Aβ1–42/FXIIa ratio (c) capable of discriminating prodromal AD from normal. Cut-off values of Aβ1–42 (d), FXIIa (e), and CSF Aβ1–42/FXIIa ratio (f). ROC curves are shown for each marker, in which arrows indicate cut-off values capable of distinguishing P-AD and AD-D groups from NR

Table 3.

Cut-off scores and sensitivity/specificity values of fluid biomarkers for discriminating the prodromal AD or AD dementia from normal subjects

| Characteristics | Normal (n = 50) vs. Prodromal AD (n = 23) groups | Normal (n = 50) vs. AD dementia (n = 28) groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC | p value | Cut-off | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC | p value | |

| Plasma factors | ||||||||||

| FXIIa activity, U/ml | > 26.3 | 73.9 | 74.0 | 0.783 | < 0.001 | > 27.2 | 78.6 | 78.0 | 0.906 | < 0.001 |

| FXIa activity, U/ml | > 1.13 | 52.2 | 52.0 | 0.566 | 0.367 | > 1.17 | 57.1 | 58.0 | 0.659 | 0.020 |

| FXa activity, U/ml | > 0.76 | 56.5 | 54.0 | 0.573 | 0.316 | > 0.82 | 71.4 | 70.0 | 0.779 | < 0.001 |

| Kallikrein activity, U/ml | > 1.21 | 56.5 | 56.0 | 0.609 | 0.138 | > 1.29 | 64.3 | 64.0 | 0.772 | < 0.001 |

| CSF biomarkers | ||||||||||

| Aβ1–42 levels, pg/ml | < 832.4 | 87.0 | 88.0 | 0.962 | < 0.001 | < 721.7 | 89.3 | 98.0 | 0.979 | < 0.001 |

| t-Tau levels, pg/ml | > 252.6 | 65.2 | 66.0 | 0.701 | 0.006 | > 315.3 | 85.7 | 86.0 | 0.954 | < 0.001 |

| p-Tau181 levels, pg/ml | > 46.1 | 65.2 | 64.0 | 0.690 | 0.009 | > 46.1 | 78.6 | 78.0 | 0.870 | < 0.001 |

| BK levels, pg/ml | > 46.1 | 54.5 | 56.5 | 0.656 | 0.073 | > 52.8 | 74.1 | 73.9 | 0.783 | 0.001 |

| Ratios | ||||||||||

| Aβ1–42 / FXIIa | < 33.8 | 87.0 | 86.0 | 0.965 | < 0.001 | < 27.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1.000 | < 0.001 |

| Aβ1–42 / FXIa | < 742.5 | 82.6 | 82.0 | 0.930 | < 0.001 | < 635.4 | 96.4 | 96.0 | 0.993 | < 0.001 |

| Aβ1–42 / FXa | < 1,091 | 82.6 | 82.0 | 0.933 | < 0.001 | < 941.8 | 96.4 | 96.0 | 0.994 | < 0.001 |

| Aβ1–42 / Kallikrein | < 680.9 | 87.0 | 86.0 | 0.943 | < 0.001 | < 584.8 | 96.4 | 96.0 | 0.994 | < 0.001 |

Statistically-derived optimal cut-off value was determined with the best balance between sensitivity (Sen) and specificity (Spe) values. Discrimination of prodromal AD and AD dementia from normal group was evaluated by receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curve analysis and quantified by the area under the curve (AUC) using SPSS software version 24.0

In particular, the CSF Aβ1–42/FXIIa ratio showed very accurate for prodromal AD (AUC = 0.965; cut-off value = < 33.8) and perfect diagnostic abilities for AD dementia (AUC = 1.0; cut-off value = < 27.44) (Fig. 2c, f; Table 3). Taken together, these results suggest that, 1) FXIIa can be used as a plasma biomarker for early diagnosis of prodromal AD, and 2) use of the Aβ1–42/FXIIa ratio improves diagnostic accuracy.

Conclusions

Based on the results, we conclude that 1) activation of plasma contact system is not only correlated with AD progression, but also is available for AD diagnosis; 2) the degree of AD progress can be quickly determined by measuring the activities of contact factors in blood plasma; 3) among the contact factors, FXIIa can be used as a new plasma biomarker for diagnosing prodromal AD and AD dementia at early stage, and 4) the use of Aβ1–42/FXIIa ratio improves diagnostic accuracy for discriminating prodromal AD and AD dementia from normal.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. The standard curves for contact factors activities (FXIIa, FXIa, Fxa, and plasma kallikrein). The curves were fitted by sigmoidal 4 parameter curve of data points.

Additional file 2:: Supplementary Table 1. Correlation of CSF AD biomarkers and plasma contact factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants and the Gwangju Alzheimer’s disease and related Dementias cohort center (Chosun University, Gwangju, Republic of Korea) for provide all the clinical data.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- FXIIa

Factor XIIa

- Aβ,

Amyloid-beta

- FXI

Factor XI

- PKK

Prekallikrein

- HK

High-molecular weight kininogen

- PK

Plasma kallikrein

- BK

Bradykinin

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

Authors’ contributions

JEP conducted the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; DSL and YHC performed the research; KYC and JJL analyzed the data; KHL provided clinical information; BCK diagnosed study participants; and JSL designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (2016M3C7A1905469). This study was also supported in part by a research fund from Chosun University, 2015.

Availability of data and materials

For original data, please contact jsplee@chosun.ac.kr. Detailed data on correlation and cut-off scores may be found in “Supplemental Table 1” available with the online version of this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants in this study provided their written consents, and the study protocol was approved by Chosun University Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jung Eun Park, Email: jepark@chosun.ac.kr.

Do Sung Lim, Email: lds9509@gmail.com.

Yeong Hee Cho, Email: kdsinichi@naver.com.

Kyu Yeong Choi, Email: khaser@gmail.com.

Jang Jae Lee, Email: jjjlee21@gmail.com.

Byeong C. Kim, Email: byeong.kim7@gmail.com

Kun Ho Lee, Email: leekho@chosun.ac.kr.

Jung Sup Lee, Email: jsplee@chosun.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Bronzuoli MR, Iacomino A, Steardo L, Scuderi C. Targeting neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Inflamm Res. 2016;9:199–208. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S86958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blennow K. A review of fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: Moving from CSF to blood. Neurol Ther. 2017;6(Suppl 1):15–24. doi: 10.1007/s40120-017-0073-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thambisetty M, Lovestone S. Blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: challenging but feasible. Biomark Med. 2010;4(1):65–79. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Bryant SE, Mielke MM, Rissman RA, Lista S, Vanderstichele H, Zetterberg H, et al. Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer disease: current state of the science and a novel collaborative paradigm for advancing from discovery to clinic. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(1):45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anoop A, Singh PK, Jacob RS, Maji SK. CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;2010:606802. doi: 10.4061/2010/606802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mari D, Parnetti L, Coppola R, Bottasso B, Reboldi GP, Senin U, et al. Hemostasis abnormalities in patients with vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Thromb Haemost. 1996;75(2):216–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta A, Watkins A, Thomas P, Majer R, Habubi N, Morris G, et al. Coagulation and inflammatory markers in Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(1):52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamolodchikov D, Chen ZL, Conti BA, Renne T, Strickland S. Activation of the factor XII-driven contact system in Alzheimer’s disease patient and mouse model plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(13):4068–4073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423764112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen ZL, Revenko AS, Singh P, MacLeod AR, Norris EH, Strickland S. Depletion of coagulation factor XII ameliorates brain pathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease mice. Blood. 2017;129(18):2547–2556. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-753202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JE, Park JW, Lee W, Lee JS. Pleiotropic effects of a vibrio extracellular protease on the activation of contact system. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2014;450(2):1099–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y. Contact pathway of coagulation and inflammation. Thromb J. 2015;13:17. doi: 10.1186/s12959-015-0048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maas C, Govers-Riemslag JW, Bouma B, Schiks B, Hazenberg BP, Lokhorst HM, et al. Misfolded proteins activate factor XII in humans, leading to kallikrein formation without initiating coagulation. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(9):3208–3218. doi: 10.1172/JCI35424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merlini M, Akassoglou K. Alzheimer disease makes new blood contacts. Blood. 2017;129(18):2462–2463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-772087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto-Imoto H, Zamolodchikov D, Chen Z-L, Bourne SL, Rizvi S, Singh P, et al. A novel detection method of cleaved plasma high-molecular-weight kininogen reveals its correlation with Alzheimer's pathology and cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;10:480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh PK, Chen Z-L, Strickland S, Norris EH. Increased Contact System Activation in Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients with Impaired Short-Term Memory. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;77(1):59–65. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z-L, Singh P, Wong J, Horn K, Strickland S, Norris EH. An antibody against HK blocks Alzheimer’s disease peptide β-amyloid− induced bradykinin release in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(46):22921–22923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914831116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):614–629. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings JL, Khachaturian ZS. Clinical diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease. 2007. Definitions and diagnostic criteria. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim HJ, Park JE, Kim BC, Choi S-M, Song M-K, Cho SH, et al. Comparison of Two Analytical Platforms in Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers for the Classification of Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum with Amyloid PET Imaging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(3):949–58. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerin JS, Murray DW, McGrath MM, Yuille MA, McPartlin JM, Doran PP. Molecular medicine Ireland guidelines for standardized biobanking. Biopreserv Biobank. 2010;8(1):3–63. doi: 10.1089/bio.2010.8101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slemmon JR, Meredith J, Guss V, Andreasson U, Andreasen N, Zetterberg H, et al. Measurement of Aβ1–42 in cerebrospinal fluid is influenced by matrix effects. J Neurochem. 2012;120(2):325–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parnetti L, Chiasserini D, Eusebi P, Giannandrea D, Bellomo G, De Carlo C, et al. Performance of abeta1-40, abeta1-42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau as predictors of dementia in a cohort of patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29(1):229–238. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J, Akaike T, Hayashida K, Miyamoto Y, Nakagawa T, Miyakawa K, et al. Identification of bradykinin receptors in clinical cancer specimens and murine tumor tissues. Int J Cancer. 2002;98(1):29–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh PK, Chen Z-L, Ghosh D, Strickland S, Norris EH. Increased plasma bradykinin level is associated with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s patients. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;139:104833. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcos-Contreras OA, Martinez de Lizarrondo S, Bardou I, Orset C, Pruvost M, Anfray A, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis increases blood-brain barrier permeability by a plasmin- and bradykinin-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2016;128(20):2423–2434. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-705384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukaka MM. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24(3):69–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu WT, Watts KD, Shaw LM, Howell JC, Trojanowski JQ, Basra S, et al. CSF beta-amyloid 1-42 - what are we measuring in Alzheimer's disease? Ann Clin Transl Neur. 2015;2(2):131–139. doi: 10.1002/acn3.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greiner M, Pfeiffer D, Smith RD. Principles and practical application of the receiver-operating characteristic analysis for diagnostic tests. Prev Vet Med. 2000;45(1–2):23–41. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(00)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. The standard curves for contact factors activities (FXIIa, FXIa, Fxa, and plasma kallikrein). The curves were fitted by sigmoidal 4 parameter curve of data points.

Additional file 2:: Supplementary Table 1. Correlation of CSF AD biomarkers and plasma contact factors.

Data Availability Statement

For original data, please contact jsplee@chosun.ac.kr. Detailed data on correlation and cut-off scores may be found in “Supplemental Table 1” available with the online version of this article.