Abstract

Problem

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly challenged maternity provision internationally. COVID-19 positive women are one of the childbearing groups most impacted by the pandemic due to drastic changes to maternity care pathways put in place.

Background

Some quantitative research was conducted on clinical characteristics of pregnant women with COVID-19 and pregnant women’s concerns and birth expectations during the COVID-19 pandemic, but no qualitative findings on childbearing women’s experiences during the pandemic were published prior to our study.

Aim

To explore childbearing experiences of COVID-19 positive mothers who gave birth in the months of March and April 2020 in a Northern Italy maternity hospital.

Methods

A qualitative interpretive phenomenological approach was undertaken. Audio-recorded semi-structured interviews were conducted with 22 women. Thematic analysis was completed using NVivo software. Ethical approval was obtained from the research site’s Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study.

Findings

The findings include four main themes: 1) coping with unmet expectations; 2) reacting and adapting to the ‘new ordinary’; 3) ‘pandemic relationships’; 4) sharing a traumatic experience with long-lasting emotional impact.

Discussion

The most traumatic elements of women’s experiences were the sudden family separation, self-isolation, transfer to a referral centre, the partner not allowed to be present at birth and limited physical contact with the newborn.

Conclusion

Key elements of good practice including provision of compassionate care, presence of birth companions and transfer to referral centers only for the most severe COVID-19 cases should be considered when drafting maternity care pathways guidelines in view of future pandemic waves.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pandemic, Childbirth, Women, Experience, Maternity care, Midwifery

Statement of significance.

Problem or issue

COVID-19 positive women are one of the childbearing groups most impacted by the pandemic due to drastic changes to maternity care pathways put in place.

What is already known

The COVID-19 pandemic is having a negative emotional effect on pregnant women and mothers with significant impact on their childbirth expectations and experiences.

What this paper adds

Key elements of good practice that should be adopted across maternity care pathways to promote positive childbirth experiences in the context of a pandemic were identified. Compassionate care, effective communication and support, labour and birth guidelines allowing the presence of asymptomatic birth companions, and comprehensive transfer protocols shared among centers should be considered by healthcare professional and policy maker.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization [1] declared Coronavirus (COVID-19) to be a pandemic disease and a global public health emergency on the 11th of March 2020. Since the first case of COVID-19 pneumonia was reported in Wuhan in December 2019, the infection has spread rapidly to the rest of China and beyond [2,3]. At present, COVID-19 is affecting 213 countries and territories around the world, with a total of 31,343,430 cases, 965,250 deaths and 23,134,704 recovered patients [3]. The first Italian COVID-19 case was reported on the 21st of February 2020, leading to a chain of infections which has recorded a high rise in cases and deaths, ranking Italy as one of the most impacted countries outside the Asian region. Lombardy, a region in Northern Italy with a population of approximately 10 million people, was one of the areas hit the hardest by the pandemic. According to the Italian Ministry of Health’s COVID-19 dashboard [4], Lombardy had 114,800 cases and 16,994 deaths as of Oct 13, 2020, which is one third of all cases and half of all deaths in Italy. Since the beginning of March, strict lockdown measures were put in place in this geographic area, which entered a deceleration phase of the outbreak in mid-April 2020 and a new acceleration phase in mid-October 2020.

Within few days of the first COVID-19 diagnosis on the 21st of February 2020, specific guidelines were issued by the national Ministry of Health and the Lombardy Region Health Care Authority in order to organize hospital and territorial work and to contain viral spread [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. According to these guidelines, some hospitals in the Lombardy region were identified as a hub for managing COVID-19 positive individuals. As per maternity services, five centres were selected, including the research site. In-person visits were maintained only if deemed necessary, and remotely delivered services for visits and childbirth preparation classes were implemented. As a measure of viral spread control, birth companions and skin-to-skin were allowed only for COVID-19 negative women. Rooming-in was permitted in both non-infected and infected women with no or mild symptoms to facilitate bonding and breastfeeding initiation. All women admitted to hospital were given surgical masks and asked to wear them throughout their hospital stay and during labour. Testing for COVID-19 upon woman’s hospital admission by PCR on nasopharyngeal swab was initially performed if temperature above 37.5 °C, cough or gastrointestinal issues were identified. From the 16th of March 2020, an admission questionnaire was implemented and all women with a positive questionnaire were tested [9]. In agreement with a disposition of the Lombardy Region Health Care Authority [6], universal viral screening started on the 8th of April 2020.

The implementation of international, national and local safety measures such as lockdown, quarantine, borders’ closure, travel bans and physical distancing have resulted in a dramatic change of daily normal life [10]. Increased isolation, decreased access to social networks and changes in maternity care services may have a significant impact on the psychosocial wellbeing of childbearing women and their families. Negative feelings may come from the strict restrictions posed by antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care guidelines, including isolation, reduced appointments, birth partners not allowed in hospital and reduced contact between mother, family and neonate [5,7]. A cross-sectional online survey exploring the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Italian pregnant women found that whilst feelings of joy, safety and love characterised childbirth expectations before COVID-19, feelings of fear, loneliness, anxiety, danger and worry were dominant after the spread of the pandemic [11].

Although some quantitative research has been conducted on clinical characteristics of pregnant women with COVID-19 [12] and pregnant women’s concerns and birth expectations during the COVID-19 pandemic [11], no qualitative findings on childbearing women’s experiences during the pandemic have been published prior to our study. Some qualitative data were published following data collection and analysis, therefore these will be considered in the discussion section. The current research was undertaken in the light of COVID-19 cases rapidly rising again in some countries and of a potential second global pandemic in the coming months.

The aim of this study was therefore to explore childbearing experiences of mothers who tested positive to COVID-19 during pregnancy or in the intrapartum period who gave birth in the months of March and April 2020 in a Northern Italy maternity hospital.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design

A qualitative study using interpretive phenomenology was undertaken to explore lived experiences of the childbearing event from the perspective of mothers who tested positive to COVID-19 during the pandemic in Italy and gave birth during the months of March and April 2020.

2.2. Research setting

The research setting was a Northern Italy maternity hospital (MBBM Foundation at San Gerardo Hospital, Monza) in the Lombardy region, which was designated as a referral hub centre for managing COVID-19 positive women during the pandemic. Transfer of women to the research site always occurred after informed consent was given.

2.3. Sampling strategy, participants and recruitment

A purposive sampling strategy was adopted, with all mothers (n = 34) who tested positive to COVID-19 and gave birth in the research site or were transferred, after consent, in the postpartum period to the research site during the months of March and April 2020 being eligible to take part in the study. The exclusion criteria were COVID-19 negative women and mothers not able to undertake the interview in Italian. The recruitment process involved identifying eligible participants who were already enrolled in a quantitative cohort study on COVID-19 immunity being undertaken in the same research site. The research team had not been able to contact three women who did not answer the phone. Thirty-one potential participants were provided with information about the study and invited to take part by one of the researchers. A total of 22 women consented to participate, giving a 71% response rate.

2.4. Data collection

Data collection commenced mid-June 2020 and was completed by the end of June 2020, using audio-recorded semi-structured interviews conducted by telephone/video-call (n = 21) or face-to-face (n = 1) depending on the woman’s preference. The individual interviews were conducted by two members of the research team (AN/SF). Topics for the interview were developed from existing evidence and agreed by the research team and an external panel including 2 practicing midwives and 1 obstetrician prior to data collection. The topics explored included the experience of being pregnant during a pandemic; the impact of COVID-19 infection on maternal-fetal wellbeing and childbearing event; the experience of labour and birth in the light of restrictions and safety measures in place; the access and use of maternity services; the relationship with family, friends and healthcare professionals; concerns and reassuring factors. The following socio-demographic and clinical data were also collected for each participant to contextualise the women’s experiences: age; marital status; nationality; education; employment; parity; number of children; pregnancy risk level; gestational weeks at start of lockdown; birth date; gestational weeks at birth; type of birth; infant feeding information; date of first COVID-19 positive test; date of second COVID-19 positive test; interview date; transfer and admission of neonate to neonatal intensive care unit.

2.5. Data analysis

All recordings were transcribed verbatim and a thematic data analysis guided by an interpretive phenomenological approach was conducted using the NVivo software. Anonymised transcripts were read and coded independently by two members of the research team (AN/SF) in the first instance, to delineate units of meaning [13]. A second iteration of coding was reviewed by AN/SF/SB and the units of meaning were clustered to form themes and sub-themes. Quotes from each interview were identified to support the agreed themes/sub-themes and to allow exploration of contradicting data. The final coding framework was then reviewed and agreed by all authors.

2.6. Authors’ background

Three of the authors have backgrounds in midwifery (SF/SB/AN) and two of them have an obstetric background. Although bracketing was not implemented and a midwifery lens was applied to data gathering and analysis, there was a conscious effort to avoid the influence of existing views to maintain openness to data. The practicing healthcare professionals who were part of the external panel contributing ideas/feedback for the development of the interview topic guide helped in shaping the questions around the lived experiences of women and their families in the context of the ‘modified’ maternity care services during the pandemic.

2.7. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the research site’s Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study (3140/2020 Ethics Committee Brianza). Information sheets were made available for potential participants. Participation was voluntary and women were free to decline or withdraw at any time with no impact on the care received. Informed consent was gained from all participated women prior to the interview. Audio recordings were stored securely and pseudonyms were used to anonymise the scripts and disseminate findings. Due to the research topic being sensitive and having the potential of causing emotional discomfort, strategies were identified to prevent and limit participants’ distress including sensitive and open questioning; researchers’ self-disclosure; creation of a comfortable interview environment; flexibility in interview timing and potential interruption of interview [14].

3. Findings

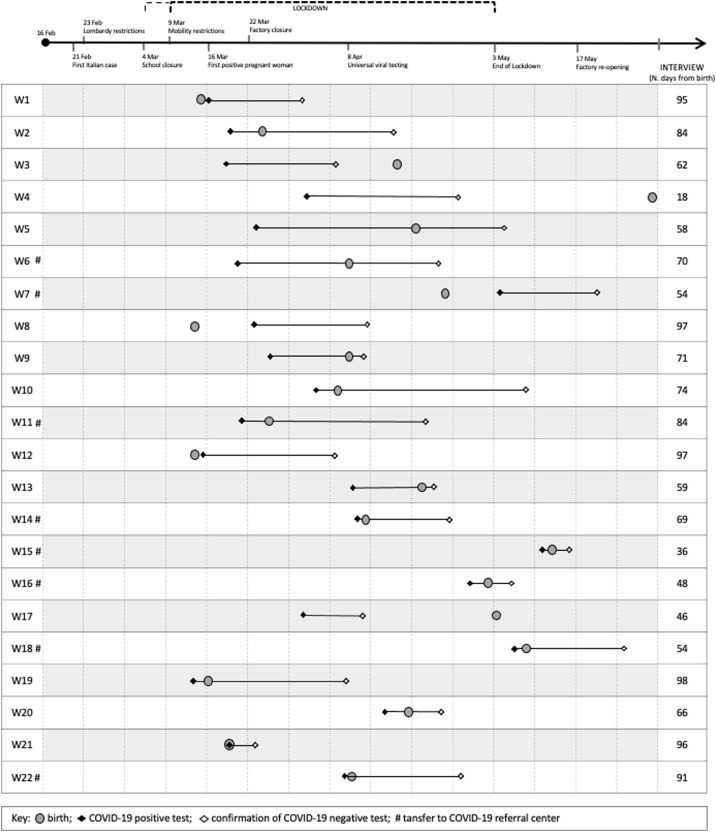

The participants’ demographic data are summarised in Table 1 . Fig. 1 represents the timeline of women’s experiences in the context of measures taken in Italy during COVID-19 pandemic. In tables, figures and quotes, participating women are referred to as W1, W2, W3 etc.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic data.

| Participant | Age | Country of birth | Educational level | Occupational status | Parity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | 33 | Peru | High school | Not working | Multiparous |

| W2 | 30 | Italy | High school | Working | Primiparous |

| W3 | 31 | Italy | Professional school | Working | Primiparous |

| W4 | 39 | Italy | Professional school | Working | Multiparous |

| W5 | 24 | Italy | High school | Working | Primiparous |

| W6 | 37 | Italy | University | Working | Primiparous |

| W7 | 33 | Italy | High school | Working | Primiparous |

| W8 | 38 | Italy | Professional school | Working | Multiparous |

| W9 | 45 | Italy | High school | Working | Multiparous |

| W10 | 30 | Italy | University | Working | Multiparous |

| W11 | 34 | Italy | University | Working | Multiparous |

| W12 | 39 | Italy | University | Working | Multiparous |

| W13 | 30 | Dominican Republic | High school | Working | Multiparous |

| W14 | 30 | Italy | High school | Working | Primiparous |

| W15 | 41 | Italy | High school | Working | Primiparous |

| W16 | 39 | Italy | University | Working | Multiparous |

| W17 | 35 | Italy | University | Working | Multiparous |

| W18 | 30 | Albania | University | Not working | Multiparous |

| W19 | 38 | Italy | High school | Working | Multiparous |

| W20 | 32 | Ukraine | High school | Working | Multiparous |

| W21 | 33 | Italy | University | Working | Multiparous |

| W22 | 33 | Italy | High school | Working | Multiparous |

Fig. 1.

Timeline of women’s experiences in the contest of measures taken in Italy during COVID-19 pandemic.

The findings include four main themes: 1) coping with unmet expectations; 2) reacting and adapting to the ‘new ordinary’; 3) ‘pandemic relationships’; 4) sharing a traumatic experience with long-lasting emotional impact. Themes and sub-themes are reported in Table 2 , including the number of participants and supporting quotes in which these are identified.

Table 2.

Themes and sub-themes.

| Themes and sub-themes | N. of participants | N. of supporting quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: coping with unmet expectations | 22 | 312 |

| Chaos and uncertainty | 20 | 68 |

| Non-modifiable unmet expectations | 22 | 148 |

| Reassuring factors | 21 | 96 |

| Theme 2: adapting to the ‘new ordinary’ | 22 | 211 |

| Lockdown | 18 | 34 |

| Threat of potential virus transmission | 19 | 44 |

| Communication of positive test | 18 | 29 |

| Living with Covid-19 disease | 17 | 42 |

| The ‘new ordinary’ | 20 | 62 |

| Theme 3: ‘pandemic’ relashionships | 22 | 539 |

| Family separation and reunification | 22 | 148 |

| Maternity services and healthcare professionals | 21 | 135 |

| Relationships’ facilitators/barriers | 22 | 256 |

| Theme 4: sharing a traumatic experience with long-lasting emotional impact | 21 | 98 |

| Tragic and traumatic experience followed by resignation | 20 | 55 |

| Long-lasting emotional impact | 11 | 26 |

| Recounting the experience | 12 | 15 |

3.1. Theme 1: coping with unmet expectations

Women reported that their expectations on the childbearing event were unmet due to the unexpected changes in everyday life and maternity care pathways during the pandemic:

It wasn’t like I expected it. […] when I found out I was pregnant I would’ve never imagined to give birth this way, alone and positive to coronavirus. (W7)

3.1.1. Chaos and uncertainty

Being pregnant and the idea of giving birth during a pandemic shaped feelings of chaos and uncertainty. The women recognised an overall sense of chaos within the global, national and local macro-environments in terms of COVID-19 disease, symptomatology, transmission, treatment and maternal/neonatal outcomes:

When I tested positive everyone was still unsure of what would happen or how to approach the disease. Everyone’s uncertainty worried me a lot, especially the one of healthcare professionals. Potential vertical transmission and safety measures in case of COVID were still a doubt. (W21)

The confusion was amplified by the over-information, misinformation and disinformation provided by mass-media, mainly coming from TV news, newspapers and the internet. Some women described their need of searching and selecting reliable information on COVID-19 specifically related to childbirth, whilst others stopped following news as this was causing increased anxiety:

I was very scared and started to search for information but obviously the media weren’t helpful due to the overall alarmism. The news circulating were always uncertain and this uncertainty was terrifying. (W21)

Despite the persisting mass-media info infoemic, after giving birth the women’s attention shifted from the need of receiving up-to-date news to the care of the newborn and their maternal role. When the macro-level knowledge about the phenomenon progressively increased and clearer information were provided to the population, some women perceived an overall lower level of uncertainty:

It reassured me a little bit when they finally understood that in most cases COVID-19 positive women would not transmit the disease to the fetus. (W11)

When recounting their experiences, participants referred to the uncertainty on what actions to take in their personal micro-environment. Doubts were often related to the recognition of COVID-19 symptoms; the identification of confirmed cases within their family and social network; the review of maternity care pathways and what to expect in terms of the impact of the disease on their antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal continuum:

It was a big question mark. The world collapsed on me and I was like oh my God what now? What will happen now? How this will progress? A big question mark.(W12)

3.1.2. Non-modifiable unmet expectations

The interviewed women reported some non-modifiable unmet expectations of which they felt they had no control. These were being pregnant during a pandemic; timeline of events; testing positive to COVID-19 and transfer to a COVID-19 referral centre.

The expectations of a straightforward, calm and peaceful pregnancy were unmet and contrasted against the lived reality of a childbearing event characterised by social restrictions and isolation from public environments and social networks, with women being confined at home and not being able to ‘prepare’ properly for the newborn arrival. Living the experience of a ‘pandemic’ pregnancy was reported by women as strenuous and difficult, with one woman recalling frequent cries during the last month before birth. The worries were amplified by the fact that they felt having a ‘double responsibility’, not only for themselves but also for their child:

I was expecting to get to the end of pregnancy, relax and sort out the last few bits for the baby’s arrival and I found myself locked at home instead. (W10)

Definitely the wrong time to be pregnant… a difficult time. (W6)

Time was also considered as a non-modifiable factor. The timeline of events was seen as inescapable, unavoidable, relentless and inexorable, marked by continuous, drastic and rapid changes, for example from attending a routine antenatal appointment to testing positive, not being able to return home and being transferred immediately to an unfamiliar referral centre. The time spent in hospital was subjectively defined as a lonely and endless limbo with uncertain duration as women did not know when isolation would cease and normality would be resumed:

I went for an antenatal appointment and didn’t come back home anymore, plus I was COVID positive and got transferred to an unfamiliar place… let’s say it all happened in a blink of an eye. (W5)

Three days felt like a week […] time was dragging. (W4)

The COVID-19 test result confirming either virus susceptibility, positivity or recovery, represented the certainty of a factual reality within the uncertain limbo women were experiencing. Waiting for test results prompted feelings of anxiety and stress as women were aware that a positive/negative outcome would have determined their maternity care pathway and birthplace, with strong impact on individual decision-making and choice:

Those two weeks waiting to do the next test you are very stressed cause you think it may turn out to be positive again. (W18)

The mandatory transfer to an unfamiliar referral centre was described by women as generating anxiety. Despite the difficulty to accept the transfer, resignation to the required pathway was seen as the only option. Some women reported that their transfer felt frightening and lonely as it occurred via ambulance, with no accompanying person allowed and no pre-warning. The referral centre was often located in a far and unknown or unfamiliar area:

The ambulance arrived and transferred me, they didn’t let me take anything of mine, not even a suitcase […] and I was basically in my pajamas. (W15)

3.1.3. Reassuring factors

The women reported the following reassuring factors throughout their experience as COVID-19 positive mothers: feeling well; receiving compassionate support; use of personal protective equipment and implementation of social distancing measures; home and hospital as safe environments.

The participants were reassured by the fact they were feeling well, both in terms of maternal and neonatal general wellbeing during childbirth (e.g. normal findings at checks, cardiotocography, scans and tests) and in regard to COVID-19 disease (e.g. being classed as a population not at risk due to age and health history, not having severe symptoms, improvement of symptomatology and recovery):

I was reassured by the fact that the checks, scans and fetal monitoring were good. My baby was okay. And my symptoms were mild, I’ve never had severe symptoms (W2)

Compassionate support from the family, partner and healthcare professionals was also a reassuring factor. When women were self-isolating and no physical contact was allowed with their social network, emotional support provided ‘remotely’ by the family and partner played an important role in making them feel cared for:

I was reassured by the support of my parents, family and partner… even though there was no physical contact and we could not meet, I used to see them on videocall. (W6)

Professional support from healthcare professionals and especially from midwives was also seen by the women as essential for both their physical and psychosocial wellbeing. The competence of the multidisciplinary team in providing excellent care was praised by the women, with special mention to midwives’ exceptional compassion and emotional support. When well cared for, mothers felt more confident in caring for their baby, starting/continuing breastfeeding and establishing a routine regardless of the pandemic:

The professional competence of the people working in the [multidisciplinary hospital] team made me feel relieved. (W14)

Professionalism as a reassuring factor was acknowledged in the caregivers’ ability to provide specialist COVID-19 care alongside routine midwifery care, using personal protective equipment (PPEs) adequately and adapting swiftly to new emergency protocols. The increased competence of healthcare professionals in caring for COVID-19 positive women in the referral centres favored a more relaxed, welcoming, friendly and compassionate practice:

I arrived [at the referral centre] and found very smiling hospital staff welcoming me […] despite they had a mask on I saw they were smiling through their eyes. They told me don’t worry now you are safe here […] I saw very professional people and I perceived they were ready […] I perceived the difference from the other hospital [non referral centre] straight away. (W14)

The use of PPEs and the implementation of social distancing measures was perceived by the participants as a safe and reassuring measure put in place to protect women, newborns and the healthcare professionals. The caregivers’ appropriate use of PPEs reduced the women’s sense of guilt about their responsibility for potential transmission. Despite all the interviewed women tested positive to COVID-19, most of them reported they strictly followed the lockdown and social distancing measures in place to to protect themselves and minimise the risk of transmission during pregnancy:

The fact that she was protected [by PPEs] made me feel relieved when she was close to me, also because with the progression of labour and time going by she got closer and closer. (W14)

The women referred to their home as a physically and emotionally safe environment during the ‘pandemic’ pregnancy: physically safe in terms of feeling protected from potential contagion and emotionally safe in terms of sharing the childbearing event with their partner:

I was reassured by the fact we were all home together with no contact with the outside world. (W16)

Before testing positive, most women perceived the hospital as a frightening and dangerous place during pregnancy, when they were worried about COVID-19 transmission. For this reason, they were resistant to accessing healthcare facilities if not extremely necessary. Prior to testing positive a woman requested a home birth, as she feared hospitals during the pandemic emergency:

You go at the emergency department and if you dont have it [the virus] you risk to be infected, if you have it you risk to infect other people. (W14)

I asked to give birth at home […] I was afraid of the hospital because I had never been admitted to hospital before, I had to give birth and there was an ongoing global emergency. (W12)

Hospital was seen as a safe place during the pandemic if the woman was familiar with the environment (e.g. if they have already given birth there, attended antenatal classes and/or know the midwifery team). Healthcare facilities were also considered the safest place to be for women and their babies in case of COVID-19 positive test. Although they felt safe, the hospital stay was recalled as a difficult time and the hospital considered as a lonesome place:

I already knew the hospital because I gave birth to my first daughter and I had my antenatal appointments there, therefore I knew the staff. It’s a very small hospital. This reassured me because it felt like a familiar setting. (W11)

When I was admitted I thought okay I am here, they are safely taking care of me, so it’s okay. (W3)

I didn’t want to stay on the ward, I wanted to go away. After giving birth I didn’t want to stay there anymore with masks and gloves (W14)

3.2. Theme 2: reacting to the ‘new ordinary’

The second theme highlights how the women reacted and adapted themselves to the ‘new ordinary’ during childbirth, including their reactions to lockdown, the threat of virus transmission, the communication of COVID-19 positive test and experiencing the actual disease.

3.2.1. Lockdown

The participants modified their everyday habits and routine prior to the official implementation of lockdown measures, when news on COVID-19 cases in Italy were made public. Changes included working from home and staying home during pregnancy. When lockdown came into effect, the women reported they were leaving home exclusively for antenatal appointments:

I went out only for antenatal checks. I stayed at home for the rest of the time. (W1)

The reaction to isolation and social distancing rules was described by some women as calm and peaceful, taking uncertainties day by day towards a new ‘family balance’ and adaptation to the ‘new ordinary’. Having a garden was seen as a facilitator, especially in case of other children:

I was calm cause we have a small garden and my daughter could go out and have fun […] it was like a holiday at the beginning. (W16)

Other women claimed they perceived the lockdown period very hard, recounting feelings of anxiety and fear for potential contagion during pregnancy. Some practical strategies adopted to limit the possibility of virus transmission were the partner showering straight away when returning home from work and washing all the groceries bought at the supermarket:

Yeah we felt a bit anxious cause we couldn’t go out. When my husband came back from work, he used to shower straight away. We were also afraid of going grocery shopping cause it was inevitable to have contact with other people there. So I used to wash all the grocery shopping with alcohol. (W4)

3.2.2. Threat of potential virus transmission

The tense reaction to a potential COVID-19 transmission was amplified during pregnancy due to feeling susceptible to the virus, being worried for the fetus/newborn or other family members’ health and continuous revision of maternity care pathways causing uncertainty (e.g. issues related to birth partners being allowed or not in hospital and mother/newborn separation):

Thinking about what would follow [if testing COVID-19 positive], what could happen to the baby and the subsequent consequences was difficult. The separation from my partner would have made us feel even more isolated than what we already were. Not having a treatment available [for the virus]… entering something uncertain and unknown… (W15)

Some women reported not perceiving the potential transmission as a risk due to thinking COVID-19 was ‘fake’, living in a small town with few cases and being healthy and young, therefore not feeling exposed to COVID-19. Some women acknowledged they had a reduced perception of the disease spread before testing positive:

I wasn’t worried anyway cause we live in a small town where there have probably been 10 COVID cases with 2 hospitalisations in total. I wasn’t afraid [of catching the virus], we all felt a bit untouchable. (W16)

3.2.3. Communication of positive test

Depending on the perception of individual contagion risk, the women recalled the communication of a positive test as either predictable or unforeseeable news. A positive test was expected in case of a suspected case in the family and having had symptoms (even if mild) in the previous weeks. The positive test came as a shock in case of no symptomatology and if all the preventive measures were respected (e.g. social distancing and staying at home for months). Two women defined the communication of testing positive as a ‘cold shower’:

I was expecting it due to the family situation. (W10)

Yes it’s been a little bit of a cold shower… I immediately realised I would have had to self-isolate, I was worried for breastfeeding, I was worried. (W22)

3.2.4. Living with Covid-19 disease

Knowing they had been diagnosed with COVID-19 generated a feeling of apprehension in the women, who were concerned not so much for their condition but primarily for their fetus/newborn’s health, alongside worrying about healthcare professionals’ well-being. The level of worry for potential virus transmission to caregivers increased particularly when the women built a trusting relationship with midwives who shared with them personal information about their life and family, especially in case of prolonged hospital stay:

My main worry was if the baby was positive too. I entered an abyss from which I came out after a long time. (W14)

Chatting with the midwife… I have been in hospital for 40 days and you establish a strong relationship… some of them told me they went away from their own place and they lived with each others [midwives] due to the fear of infecting someone at home […]. When they shared these things, I was even more afraid of me being the person infecting them. (W5)

The women receiving the news of testing positive towards the end of pregnancy were particularly worried about giving birth as COVID-19 positive mothers without a birth companion and about breastfeeding and caring for the newborn without the physical presence of their partner:

My main fear was the baby and caring for her with this problem [having COVID-19]… the fear of not being able to breastfeed or holding her. I was also sad that my husband couldn’t be with me on labour ward so. I got discouraged. (W4)

One woman reported that she felt stronger that she thought during the hospital stay:

At the beginning I imagined myself crying from morning to evening during the hospital stay. I actually reacted well instead. (W10)

3.2.5. The ‘new ordinary’

All women reported to have respected the arrangements and strict rules in place including wearing appropriate PPE, the partner’s absence, isolation during the hospital stay and self-distancing when returning home. Despite these measures often causing feelings of loneliness and sadness, both in and out of hospital the mothers reacted and adapted to the ‘new ordinary’ which was seen as a situation beyond their control. The desire of meeting their baby empowered the women to see themselves as strong and competent mothers.

And then in the end I said well, it is what it is, let’s move on and I resigned myself to it. Let’s look to the future. I concentrated on the baby who was due to arrive and that was it. (W11)

The women were very sympathetic and understanding towards the recommended care pathways to safeguard everyone’s health, despite this meant having a less satisfying birth experience:

I sympathised with the midwives’ struggling seeing me not being able to receive visits. Staying at the hospital for a month… you get used to it. I persuaded myself that it was the right thing cause I was [COVID-19] positive. (W2)

3.3. Theme 3: ‘pandemic’ relationships

Relationships are one of the most crucial aspects influencing COVID-19 women’s experiences of childbirth during the pandemic. These include family separation from the partner, newborn and other children followed by family reunification. The women discussed the relationships with healthcare professionals when accessing and using maternity services. Facilitators and barriers of relationships were also highlighted.

3.3.1. Family separation and reunification

Depending on when women tested positive and were quarantined, missing the partner’s physical presence occurred throughout the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal period, with culmination at birth.

I was sorry cause my partner has not seen the baby anymore during pregnancy after the anomaly scan. It’s a missing piece, you can’t fully share these moments without being together. (W10)

I regret the fact that my husband couldn’t be present at birth. He’s a very important figure and he would’ve been of support. And I would have liked to share this moment with him really. (W11And then there was all the sadness of going back home and not being able to see him [partner], he couldn’t touch the baby and all those things. (W22)

Some women described their labour and birth as unfulfilled, reporting feelings of bitterness and melancholy due to not having been able to share this experience with their partner. The separation from the partner at birth was lived as extremely distressing. A woman recounted she kept looking at the door in the hope her partner would enter the labour room. Women also expressed feelings of sadness and loneliness when empathising with their partner, forced down the mandatory route of not being allowed to be present at their child’s birth. Fathers were only involved in the parental relationship via technological means. Women reported the need to make up for the non-shared experience and lost time by telling events to the partner in every detail:

Goodness yes, yes, I remember the separation really well. It’s been like an abandonment and I was also sorry for him. (W6)

I arrived at the emergency department and I had to say goodbye to my husband and go in on my own […] so I went in and he stayed outside in the car park [woman cries]. He saw her [baby] only on video. (W17)

The relationship with the newborn was limited and influenced by the worry of a potential disease transmission. Despite washing hands regularly and use of appropriate PPEs (face mask and gloves), the women were concerned about holding their baby for more than what was absolutely necessary (e.g. breastfeeding time):

It was very hard cause when I was breastfeeding I was always afraid of holding her for a little longer for a cuddle despite the mask, gloves and washing hands… I wanted to avoid the contagion (W16)

The factor mostly feared by women was the physical separation from their baby advised by hospital protocols. Although the mothers suffered the lack of usual acts of love such as holding, cuddling, kissing, rocking and caressing, this was seen as unavoidable to protect the newborn. Two women whose neonates were admitted to neonatal intensive care unit felt guilty, ‘empty’ and not a good mother for not being able to see them for days. Whilst mothers were recounting the physical separation from the newborn during the interviews, their voice trembled with tears alternating to silences:

Touching her [baby] with gloves without feeling the skin, not being able to kiss her or do anything else… it’s like you can’t feel her […] that’s horrible. (W22)

They told me my baby was slightly [COVID-19] positive so they took him away from me. They took him away from me for two days and admitted him to the neonatal intensive care unit. I’ve been two days without my baby and it felt like a further abandonment. (W6)

Close relationships were formed between COVID-19 positive mothers sharing the same hospital room and going through a similar experience. Seeing another mother being able to take care of her baby (even though with PPEs’ use) emphasised the women’s pain in case of separation from their child. Conversely, seeing the other mother being separated from their baby often made them feel uncomfortable:

Then another mum arrived in the room with me […] it was a bit hard cause when she arrived I didn’t have my baby back with me yet so seeing another mum with her child was not great […]. I told the midwives ‘I am here without my baby and you bring here another mum with her baby’. It was psychologically strenuous. (W6)

I lived with her this thing of seeing her baby taken away and it’s an awful thing. (W19)

Multiparous women reported the difficulties in maintaining and managing the relationship with other kids at home, especially in the case of young children. The required prolonged separation amplified the common worries in case of a sibling’s birth, especially when the sudden hospitalisation was unexpected and not accompanied by any explanation or goodbye from the mothers to the children. Not being able to see other kids increased the women’s sense of loneliness:

I went out without even saying goodbye to my son cause I though I would go back home, then they actually admitted me to hospital straight away and I took it badly, I burst into tears as I thought all of a sudden my other child would not see me anymore. (W10)

My son asked me ‘mummy I miss you a lot, when are you coming back?’ […] He told his grandma “you can’t change the bed sheets cause then mummy’s scent goes away and I can’t smell it anymore when I go in her bed’. (W9)

The women described the experience of family reunification after a lengthy separation as emotionally intense, despite the initial self-distancing rules and mandatory use of PPEs until a negative COVID-19 test result. The places where the reunion happened were mainly the family home, hospital hall or neonatal intensive care unit. When they recovered from COVID-19, the women felt finally relieved when they could hug, touch and kiss their baby and partner without restrictions:

I remember it was a Friday, it was a beautiful Friday as all the four of us were [COVID-19] negative at home and I could hug them all, husband and child, without a mask on. That’s when our life as a family of four started. (W19)

I threw the mask, my partner threw the mask too and finally we were able to kiss this baby which was the thing we were waiting for the most. (W22)

3.3.2. Maternity services and healthcare professionals

The women reported amendments of antenatal services and visits offered by maternity units during the pandemic, with intrapartum and postnatal maternity pathways varying based on the COVID-19 test result. In the context of abrupt and continuous alterations to midwifery care, most women felt they had received clear and timely information from healthcare professionals, helping them adapt to and cope with chaotic changes:

Can’t fault them, information was good and they sent all the links to join the online antenatal classes. (W15)

A criticism identified by some interviewed mothers was the brief, rushed and superficial communication of transfer to a referral centre when they tested positive to COVID-19; this negatively influenced trust in the maternity unit. Conversely, women felt supported and safeguarded in the transfer process when relevant information were communicated and appropriate handover was observed:

I have been left from 10am to 11 pm on a chair, with no water or anything else, with giant breasts full of milk, to then tell me I was positive and that they were going to transfer me to the referral hospital. (W8)

Unquestionable kindness and professional manner. We made it even on time to let my husband know so he brought me the hospital bag. They’ve been kind but it’s still been a shock. (W16)

As anticipated in the first theme, the women recognised the importance of establishing professional and human relationships with the caregivers whilst experiencing a lonesome situation with a high bio-psycho-social impact. The mothers valued healthcare professionals using appropriate, welcoming and non-judgmental verbal language. The use of judgmental and accusatory language due to women’s COVID-19 infected status was perceived as non-professional and inappropriate, generating a sense of guilt:

On several occasions they told me ‘Stay away, stay away, keep the 1 meter distance, go to that corner in the lift […] When they came in the room to wake me up at 6am they used to open the door shouting ‘masks!’. It felt like being in a barrack […] It was very annoying. (W10)

The physical distance and presence of PPEs barriers compelled caregivers to resort to non-verbal body language, with gestures, looks and affinity being identified by women as key human factors when receiving midwifery care. The woman-midwife trusting relationship was seen as unique, exceptional and characterised by mutual solidarity, especially in such a vulnerable situation far from any expectations. One woman referred to the midwife as a ‘sister’:

They were so good and compassionate that the fact they were harnessed became less important. […] You could tell from their eyes that they were taking care of you. They were there no matter what. (W2)

She made me feel like she was my sister, she didn’t go away not even for a second. (W18)

Despite the mothers acknowledged and justified the reduction of contact with the midwife during the hospital stay, they identified this accentuated loneliness and had a negative impact on their overall experience.

The midwives and other staff were always very kind and optimistic and this reassured me. They didn’t come in very often, I think they had to wear all the protective equipment every time they wanted to come in my room and the preparation was probably very long. So I noticed that the visits were made only when necessary. (W21)

One woman felt her needs had not been met intrapartum, reporting ineffective and non-compassionate caring relationships, which improved considerably during the postnatal hospital stay:

I was admitted in advanced labour and I honestly expected to be more pampered and supported given that I was there alone […]. The doctor was tired and was hot so he sat on a chair with his eyes closed. The midwife was busy writing. Apart when she visited me and asked routine questions, she didn’t really consider me and wasn’t present throughout […] I was alone. […] Then on the ward it’s been the opposite, they’ve all been extremely caring, from the first to the last midwife. (W10)

3.3.3. Relationships’ facilitators/barriers

The mothers identified the factors reported in Table 3 as having a dual meaning in terms of being relationships’ facilitators and barriers at the same time:

Table 3.

Relationships’ facilitators/barriers.

| Factor | Facilitator | Barrier |

|---|---|---|

| Use of technology | Virtual contact with loved ones when physical contact was not allowed | Screen-mediated relationship |

| I could show her [baby] to him [partner] only by video. (W17) | ||

| We have maintained the contact with videocalls and calls (W10) | ||

| Self-isolation and family separation | Opportunity to establish emotionally intense and life-saving relationships with the midwife | Obstacle to partner’s participation especially at birth |

| Postnatal period spent with close family + limited interference from others | Limiting postnatal support from social network | |

| Feeling alone in taking care of the newborn, with no breaks from it | ||

| She made me feel like she was my sister, she didn’t go away not even for a second. (W19) | ||

| During the hospital stay unfortunately you feel alone cause the contact with healthcare professionals is limited. You are in a room, you can’t go out and you’ve got to stay between those four walls. (W15) | ||

| Not having visits, you don’t even have a time during which you take a break, go to the toilet and have a shower. This aspect has been quite heavy. (W10) | ||

| Testing positive to Covid-19 | Increased acceptance of distancing rules and separation due to feeling responsible towards safeguarding others’ health (partner, child and professionals) | When used by others as discriminatory factor |

| Sense of guilty generated difficulties in establishing mother-newborn relationship | ||

| Despite all mine and other people’s protective equipment, I noticed them taking a step back yet again. And I also perceived this when I went back home from the hospital. (W11) | ||

| I still have a sense of guilty for my baby. Due to me being positive you were born in a horrible ward without shower, with a stinking mother and I couldn’t even put clothes on you. I felt discgusting. I had gloves and a mask on and he [baby] wasn’t even able to see my face, I feel so guilty. (W14) | ||

| Social distancing and use of PPEs | Protective measures | Limiting ‘physical’ relationships and contacts with newborn and healthcare professionals |

| Activation of alternative communication strategies (e.g. non-verbal language) | Limiting postnatal support from social network | |

| Mask and gloves allowed to have contact (even if limited) with newborn | Feeling alone in taking care of the newborn | |

| Postnatal period spent with close family + limited interference from others | ||

| You can’t even see the person who assists the birth of your baby. I can’t even remember her behind the mask, gown, hairnet, glasses and visor. I wouldn’t recognise her now, no. (W14) | ||

3.4. Theme 4: sharing a traumatic experience with long-lasting emotional impact

The interviewed women described their experience a posteriori, defining it as a tragic and traumatic experience followed by an eventual final positive resignation but with a long-lasting emotional impact. Sharing and recounting the lived experience was perceived as helpful in elaborating negative feelings.

3.4.1. Tragic and traumatic experience followed by resignation

The mothers described their overall childbearing experience as COVID-19 positive women using very strong and intense words such as ‘traumatic’, ‘tragic’, ‘difficult’, ‘strenuous’, ‘sad’, ‘disheartening’, ‘terrible’, ‘negative’, ‘odd’ and ‘unfortunate’. They reported this was one of the worst and unimaginable experiences of their lives. Some interviewees used the metaphors ‘nightmare’ and ‘war’ to give a better idea of the dreadful experience:

I’ve lived it all as a nightmare really. (W14)

Sometimes it looked like we were at war, there was lack of water, few essential aids, you asked things and they came after a while. They’ve not changed my sheets in hospital for a week. (W3)

It’s been very challenging fighting this pandemic war […] and who’s lived it in first person like me and my family knows it’s hard, it hurts. (W8)

Although all women highlighted negative feelings with long-lasting emotional impact, they recognised an eventual positive resignation after the birth of their baby and especially when the family was finally reunited:

It was what it was, but it ended well (W9)

It’s gone, thank goodness, for us it went well in the end (W4)

Thank God nothing bad happened (W1)

3.4.2. Long-lasting emotional impact

The women identified the lived experiences as having a long-lasting emotional impact on their present life, identifying negative memories as indelible and unforgettable. The grief and pain were accentuated by rethinking about events, looking at photos or returning to the hospital where they had been admitted:

Yes these things stay with you and leave scars (W19)

Even now, if I look at the photos taken at the hospital I feel like crying and down […] I’ve lived this experience really badly, just seeing a photo on my phone hurts me a lot [cries]. (W14)

This pandemic made me feel the greatest fear of my life. It consumes you not being able to kiss your kids cause you’re afraid of killing them, not being able to hug your mum after she’s been at home with your dead father for two days. It kills you seeing your kid not sleeping at night with panic attacks because he’s afraid his dad is gonna die. This pandemic has killed me. (W8)

At the time of the interviews, some mothers were in the process of reacting to the negative experience by: a) seeking professional psychological help to elaborate events; b) trying to ‘forget’ the past and build a new peaceful normality; c) desiring redemption from a ‘lost’ experience by having another child in the future:

Yes I have already contacted a psychologist. I’m not afraid of asking for help, I’m afraid of going out from home. (W14)

Now that he [baby] is here I must try and live the happiest that I can possibly be, otherwise we will never be able to fully live anymore in this situation really. (W3)

I am thinking I need to have a second one [child] to experience what I haven’t with this first child. (W14)

In the attempt of readapting to a new normal, the women were annoyed, offended and hurt by other people’s disrespect when not observing the safety measures in place e.g. social distancing and use of face masks. They also felt not totally understood by members of the public who had not direct experience of the disease:

The day they’ve discharged me I saw an awful lot of people out and I cried cause I thought ‘why are all these people out, don’t they know what happen if you get the virus?’. (W5)

3.4.3. Recounting the experience

The women appreciated the opportunity to participate in the current research study. Although the interviews were emotionally intense and characterised by struggles, cries, touching voices, pauses and silences, the mothers acknowledged the benefits of sharing feelings and experiences. Despite some women had already recounted events to the partner and/or significant others, most women had never shared their experience in detail due to it being emotionally distressing. Over the course of time, the women perceived that recalling and sharing events was increasingly helpful in order to elaborate and positively react to the emotionally strong lived experience. Some women felt the duty of sharing their experiences with the community to help other people understand the importance of preserving everyone’s safety:

Yes, I am not a very chatty person and I must say I am sharing this experience with everyone. It’s useful to talk about it cause it’s a trauma, we’ve lived some traumatic moments so it’s important to vent somehow. (W11)

I’m starting now to talk about it cause until the last few days it’s not been easy […]. It’s true it’s all gone now but it’s still difficult. (W15)

4. Discussion

This study explored the childbearing experiences of COVID-19 positive women during the pandemic in Northern Italy. The findings highlighted how the mothers coped with unmet expectations, including their reaction and adaptation to a ‘new pandemic ordinary’. The relationships highly influenced the women’s lived experiences and were strongly impacted by the general safety measures and re-organisation of maternity services during the pandemic.

The uncertainties, unmet expectations and worries typical of childbirth [15,16] were evidently exacerbated by the pandemic. A recently published qualitative study conducted in Turkey exploring COVID-19 negative pregnant women’s concerns, problems and attitudes during the pandemic found similar findings to the present study in regard to potential anxiety, adversity and fear with negative emotional effects on pregnant women [17]. A cross sectional online survey by Ravaldi et al. (2020) similarly reported that women’s expectations and concerns regarding childbirth changed significantly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy, with the need to provide effective emotional support, in particular to women with a history of psychological disorders as they seem to experience higher levels of concern [11].

What our study adds is a specific focus on COVID-19 positive women and the consideration of their whole childbearing event from pregnancy to the postnatal period. COVID-19 positive women are one of the childbearing groups most impacted by the pandemic due to strict safety measures and drastic changes to maternity care pathways put in place for them.

It was noted that the woman’s status (pregnant vs postpartum) at the moment of positive test result was one of the main elements influencing the childbearing experience. Women with confirmed COVID-19 positivity during pregnancy were generally more negatively affected than women who received a positive result after birth.

As highlighted by our findings, the most traumatic elements of these women’s experiences were the sudden family separation, self-isolation, the partner not allowed to be present at birth and the use of masks and gloves in the physical interaction with the newborn. A mixed-method cohort study by Bender et al. (2020) similarly identifies neglect, isolation and neonatal separation as difficult aspects of COVID-19 positive women’s experiences of birth [18]. The theme named ‘pandemic relationships’ is the one to which the interviewed women gave most attention when recounting their experiences. A number of authors highlight the importance of mothers receiving continuous support from an effective social network, family, significant others, birth companions and healthcare professionals throughout childbirth [[19], [20], [21]]. Although the women interviewed for our study praised the midwives’ providing not only professional and competent care but also emotional, compassionate and family-like support, they highly suffered from the absence of a birth companion. Labour companionship is a key component of providing respectful maternity care and makes a significant difference to the safety and wellbeing of women during childbirth [22]; as such, it is recommended by WHO as one of the standards for improving quality of intrapartum care [23].

Alongside the theme “pandemic relationships”, transfer to a referral centre was identified as an additional traumatic element although it always occurred after informed consent was given by the woman. Scant information on COVID-19 related problems in pregnant women and their newborns at the beginning of the pandemic as well as the need of prioritising the safety of this particular population dictated the Regional decision of creating referral centres in order to improve management. Increasing effective communication of transfer by caregivers and providing continuous support and information throughout the transfer process could allow women to live the transfer experience less negatively [24].

Our findings regarding traumatic elements of women’s experiences, alongside existing evidence on COVID-19 in pregnant women and newborns [25], should be taken into consideration by healthcare policy makers when refining updated maternity care pathways during future pandemic waves. When drafting regional, national and international guidelines, asymptomatic partners of COVID-19 positive women should be allowed to act as birth companion [22] and transfer to referral centers should be considered only for the most severe COVID-19 cases.

Recounting and sharing experiences is already valued by women in a ‘normal’ childbirth context [26,27], but is even more needed during a pandemic through the elaboration of negative feelings/memories and the adaptation to a ‘new normal’ as highlighted by the findings of the present research. The interviewed women described their experience a posteriori, defining it as tragic and traumatic, followed by an eventual final positive resignation but with a long-lasting emotional impact. In support to this, The White Ribbon Alliance (2011) states: ‘women’s experiences with caregivers can empower and comfort or inflict lasting damage and emotional trauma. Either way, women’s memories of their childbearing experiences stay with them for a lifetime and are often shared with other women, contributing to a climate of confidence or doubt around childbearing’ [28]. As suggested by Zanardo et al. (2020), pregnant women giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic represent a highly vulnerable population that needs to be carefully followed up to improve psychosocial wellbeing [29]. This can be achieved through the screening and evaluation of factors affecting pregnant and postpartum women’s psychological status to decrease postpartum depression rates and improve maternal-infant bonding [30].

5. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the research include the novelty of topic and participants in the context of the recent COVID-19 pandemic. The rigorous and systematic approach to data collection and analysis increases study validity and credibility. A limitation of the study was that some interviews were conducted via phone and audio-recorded only, resulting in the interviewers being unable to account for any non-verbal cues. The findings are transferable to similar local, national and international settings needing urgent improvements in the provision of maternity care currently facing a second or subsequent pandemic emergency.

6. Conclusions and implications for practice

This study explored the childbearing experiences of mothers in the context of a non-ordinary pandemic situation where emergency restrictive policies were put in place to lower the spread of the disease, with significant impact on the care provided and received. Critical elements identified by the interviewed women suggest the following key components of good practice that should be adopted across the whole maternity care pathway in the context of a pandemic:

-

•

support and follow-up women and families’ socio-psychological wellbeing, giving the opportunity to share and recount experiences, uncertainties and concerns throughout the childbearing event;

-

•

allow asymptomatic birth companions of COVID-19 positive women to stay with them throughout labour and birth with provision of appropriate PPEs;

-

•

draft comprehensive and shared transfer guidelines, with a focus on effective communication and support;

-

•

consider transfer to COVID-19 referral centers only for women with severe COVID-19 symptoms;

-

•

provide compassionate care at all times, especially during the critical test results’ waiting time with a focus on the individual's loneliness and isolation;

-

•

provide comprehensive communication of information, including maternity care pathways (e.g. in case of COVID-19 positive or negative test result), potential transfer to a referral centre and safety measures in place. Women should be given the opportunity to ask questions and share concerns/doubts;

-

•

implement alternative ways of communication and information provision such as virtual (or social-distanced and with use of PPEs if allowed by government rules) antenatal/postnatal classes and visits;

-

•

offer antenatal and postnatal home visiting from community midwives following a continuity of care model when possible;

-

•

support women in drafting a birth plan in order to decrease unmet expectations and increase awareness of different care pathways;

-

•

implement supporting measures to balance shortfalls caused by the birth companion not able to be physically present during labour, birth and in the postpartum period;

-

•

provision of professional, competent, emotional and compassionate support from caregivers, with healthcare professionals maintaining adequate contact with women and newborns using PPEs.

The suggested implications for practice can provide midwives and healthcare professionals currently facing a second pandemic wave with useful tools to improve the management of maternity care pathways for COVID-19 positive mothers, with the ultimate aim of facilitating a more positive childbirth experience for these women and their families [31,32]. Some of the practices highlighted above could also be implemented when caring for COVID-19 negative women who are experiencing similar challenges due to the overall radical changes to maternity services on care provision during the pandemic.

The research team’s research is currently also focusing on other groups experiencing the childbearing event directly or indirectly during the pandemic, including COVID-19 negative women, birth companions, families, midwives and healthcare professionals. Future recommendations for research may include medium and long-term psychosocial effects of giving birth and becoming a parent during the pandemic.

Author agreement

The article is the authors’ original work, it has not received prior publication and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript for submission. The authors abide by the copyright terms and conditions of Elsevier and the Australian College of Midwives.

Author contributions

S.F. S.O., S.B., P.V. and A.N. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the research site’s Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study.

Approval number: 3140/2020 EC Brianza.

Date of approval: 18/06/2020.

Funding

This project was self-funded.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. C. Callegari, Dr. F. Brunetti, Dr. L. La Milia, and Dr. M. Vasarri for their help in the recruitment of women.

We would also like to thank all women involved in the study.

References

- 1.WHO Director – General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University: Coronavirus COVID‐19 Global Cases. [Accessed 22 September 2020].

- 4.Dipartimento della Protezione Civile: COVID-19 Italia – Monitoraggio della situazione. Accessed on October 13, 2020.

- 5.Comitato Percorso Nascita e Assistenza Pediatrica-Adolescenziale di Regione Lombardia, SLOG, SIMP, AOGOI, SIN, SYRIO, e SISOGN: Infezione da SARS-CoV-2: indicazioni ad interim per gravida-partoriente, puerpera-neonato e allattamento. March 7, 2020.

- 6.COVID-19 Indicazioni Valide per la Lombardia. https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/portal/istituzionale/HP/DettaglioRedazionale/servizi-e-informazioni/cittadini/salute-e-prevenzione/prevenzione-e-benessere/red-coronavirusnuoviaggiornamenti.

- 7.Societa’ Italiana di Neonatologia: Allattamento e Infezione da SARS-CoV-2. Indicazioni ad interim. March 22, 2020.

- 8.Poon L.C., Yang H., Kapur A., Melamed N., Dao B., Divakar H., David McIntyre H., Kihara A.B., Ayres-de-Campos D., Ferrazzi E.M., et al. Global interim guidance on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during pregnancy and puerperium from FIGO and allied partners: information for healthcare professionals. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ornaghi S., Callegari C., Milazzo R., La Milia L., Brunetti F., Lubrano C., Tasca C., Livio S., Savasi V.M., Cetin I., et al. Performance of an extended triage questionnaire to detect suspected cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in obstetric patients: experience from two large teaching hospitals in Lombardy, Northern Italy. PLoS One. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Usher K., Bhullar N., Jackson D. Life in the pandemic: social isolation and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020;29(15–16):2756–2757. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravaldi C., Wilson A., Ricca V., Homer C., Vannacci A. Pregnant women voice their concerns and birth expectations during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Women Birth. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L., Li Q., Zheng D., Jiang H., Wei Y., Zou L., Feng L., Xiong G., Sun G., Wang H., et al. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(25) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groenewald T. A phenomelogical research design illustrated. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2004;3(1):42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmir R., Schmied V., Jackson D., Wilkes L. Interviewing people about potentially sensitive topics. Nurse Res. 2011;19(1):12–16. doi: 10.7748/nr2011.10.19.1.12.c8766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrelli S.E., Walsh D., Spiby H. First-time mothers’ expectations of the unknown territory of childbirth: uncertainties, coping strategies and ‘going with the flow’. Midwifery. 2018;63:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlen H.G., Barclay L., CS Homer. ‘Reacting to the unknown’: experiencing the first birth at home or in hospital in Australia. Midwifery. 2010;26(4):415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizrak Sahin B., Kabakci E.N. The experiences of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey: a qualitative study. Women Birth. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bender W.R., Srinivas S., Coutifaris P., Acker A., Hirshberg A. The psychological experience of obstetric patients and health care workers after implementation of Universal SARS-CoV-2 testing. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020;37(12):1271–1279. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1715505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohren M.A., Berger B.O., Munthe-Kaas H., Tunçalp Ö. Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;3(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012449.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohren M.A., Hofmeyr G.J., Sakala C., Fukuzawa R.K., Cuthbert A. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017;7(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradfield Z., Hauck Y., Kelly M., Duggan R. "It’s what midwifery is all about": Western Australian midwives’ experiences of being’ with woman’ during labour and birth in the known midwife model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Midwives TRCo . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in Pregnancy. Information for Healthcare Professionals. Version 12. [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee . World Health Organization. Copyright © World Health Organization 2018; Geneva: 2018. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grigg C.P., Tracy S.K., Schmied V., Monk A., Tracy M.B. Women’s experiences of transfer from primary maternity unit to tertiary hospital in New Zealand: part of the prospective cohort evaluating maternity units study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:339. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yee J., Kim W., Han J.M., Yoon H.Y., Lee N., Lee K.E., Gwak H.S. Clinical manifestations and perinatal outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):18126. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75096-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastos M.H., Furuta M., Small R., McKenzie-McHarg K., Bick D. Debriefing interventions for the prevention of psychological trauma in women following childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007194.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baxter J. Postnatal debriefing: women’s need to talk after birth. Br. J. Midwifery. 2019;27(9):563–571. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The White Ribbon Alliance . 2011. Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanardo V., Manghina V., Giliberti L., Vettore M., Severino L., Straface G. Psychological impact of COVID-19 quarantine measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020;150(2):184–188. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oskovi-Kaplan Z.A., Buyuk G.N., Ozgu-Erdinc A.S., Keskin H.L., Ozbas A., Moraloglu Tekin O. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic and social restrictions on depression rates and maternal attachment in immediate postpartum women: a preliminary study. Psychiatr. Q. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09843-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee . World Health Organization. Copyright © World Health Organization 2016; Geneva: 2016. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lazzaretto E., Nespoli A., Fumagalli S., Colciago E., Perego S., Locatelli A. Intrapartum care quality indicators: a literature review. Minerva Ginecol. 2018;70(3):346–356. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4784.17.04177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]