Abstract

Objective

We conducted a meta-analysis to compare major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in recent diabetes type 2 drugs cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) in the subgroups that used insulin at baseline to the subgroups that did not.

Methods

English publications from 2010 to 2019 were searched in PubMed and Google Scholar. We searched published clinical trials for CVOTs with new drugs for type 2 diabetes and found 12 publications, of which 8 provided outcomes according to insulin use. We compared the event rate of the primary outcome in the group taking insulin with the one not taking insulin. Data were extracted by 2 investigators independently, including CVOT drug, publication year, sample size, duration of diabetes, mean glycated hemoglobin A1c, mean age, and number of patients in each treatment group. We included 8 trials in the analysis: DECLARE, EMPA-REG, EXSCEL, HARMONY, LEADER, SUSTAIN-6, EXAMINE, and SAVOR-TIMI. The pooled relative risk was 1.52 (95% CI, 1.43 ~ 1.62) when comparing the treatment group with insulin at baseline with the treatment group of patients without insulin use.

Results

In recent CVOTs, patients on insulin regimen along with the new antidiabetic drug had a higher risk ratio of cardiovascular events than patients who used the new antidiabetic drug alone.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular outcomes, trials

In 2016, statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that 23 million adults in the United States were diagnosed with diabetes [1]. Diabetes carries a 2- to 3-fold increase in atherosclerotic disease both in men and women, including intermittent claudication, congestive heart disease, and coronary artery disease [2]. Multiple studies have confirmed that patients with diabetes have higher mortality rates due to cardiovascular disease compared to patients who did not have diabetes [3-6].

In 2008, the Food and Drug Administration mandated sponsors of new type 2 diabetes agents prove that therapy would not cause increased cardiovascular risk beyond a specified threshold based on findings of the RECORD trial [7, 8]. There were 12 published cardiovascular outcome clinical trials (CVOTs) comparing the new drugs for type 2 diabetes to placebo from 2013. These trials included 3 sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT-2), 6 glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1), and 3 dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4).

The CVOTs for SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists showed that patients who were treated with these drugs had a lower risk of cardiovascular events than patients treated with placebo [9-16], whereas CVOTs of patients treated with DPP-4 inhibitors did not show cardiovascular benefit or harm [17-19].

Most recent CVOTs have focused on cardiovascular outcomes when patients were taking the drugs vs placebo or compared different diabetes drugs; it is unclear how the cardiovascular health is affected when the patient regimen included insulin and other type 2 diabetes drugs. This is a very popular regimen and is often clinically used. Cosmi et al analyzed data to determine whether patients who used insulin had worse outcomes among heart failure patients, concluding that insulin was associated with higher risks of death and hospitalizations in heart failure patients [20]. Mendez et al conducted a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database to evaluate the relationship between insulin use and clinical outcomes including mortality, major cardiovascular outcome (MACE), and diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [21]. They concluded that insulin use was associated with higher mortality, MACE, and DKD in patients who had higher insulin resistance [21].

The CVOTs for the new type 2 diabetes drugs had good follow-up of participants and adjudication of events, and the trials included many patients taking insulin at baseline, which allowed us to examine the outcome when patients received the new diabetes agents along with insulin at baseline. To our knowledge, there has not been any previous analysis of CVOTs to examine the effect of an insulin and diabetes drug combination on cardiovascular events. This is a meta-analysis to assess the effect of combining new diabetes type 2 agents with insulin on cardiovascular outcomes among diabetes population in the CVOTs.

Materials and Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [22].

Data sources and searches

PubMed and Google Scholar were used to search for the published clinical trials. Key words used in the search were “diabetes type 2,” “cardiovascular,” “outcome,” and “trials.”

Study selection

Eligible studies were included if they were trials of antidiabetics within insulin. In addition, the primary outcome of these trials should be a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), such as cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or ischemic stroke. Trials were excluded if the primary outcome was not reported by insulin subgroup.

Data extraction

After removing all duplicated articles, each of the potential titles and abstract was screened. Full texts of potentially relevant studies were then retrieved and assessed to determine eligibility for inclusion according to established criteria detailed earlier (Fig. 1). Data extraction for each study included CVOT drug, publication year, sample size, duration of diabetes, mean glycated hemoglobin A1c, mean age, number of patients who were using insulin at baseline and were randomly assigned to the drug, number of patients who were not using insulin at baseline and were randomly assigned to the drug, number of patients who were using insulin at baseline and were randomly assigned to the placebo, number of patients who were not using insulin at baseline and were randomly assigned to the placebo, and number of primary outcome events in these subgroups. Any uncertainties or discrepancies between the 2 reviewers were resolved through consensus or consultation with another reviewer. Each study in this meta-analysis was assessed using Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies from the National Institutes of Health, which includes a series of criteria to rate quality. There was no attempt to contact authors during the study period.

Figure 1.

literature review flowchart.

Data synthesis and analysis

Studies only provided hazard ratios (HRs) for some comparison groups and there were no available data for us to calculate HRs for other interested comparison groups; therefore, we decided to calculate risk ratios (RRs) for all comparison groups based on the number of cases and noncases in each group provided in these studies for consistency. We reported RRs for 4 comparison groups to compare the associations between new diabetes medicine treatment with or without insulin usage and cardiovascular events. Four group sets were listed as the following: new drug treatment without baseline insulin vs placebo without baseline insulin, new drug treatment with baseline insulin vs new drug treatment without baseline insulin, new drug treatment with baseline insulin vs placebo with baseline insulin, and placebo with baseline insulin vs placebo without baseline insulin. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics, and a value greater than 50% was considered a measure of severe heterogeneity. Summary estimates of RRs and 95% CIs for the estimates were derived using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model to account for the interstudy differences because this model is often used for meta-analysis of clinical studies. For the sensitivity analysis, we conducted all the analyses again excluding clinical trials of DPP-4 because they did not demonstrate cardiovascular benefit. The meta-analysis was performed using Stata 15.1 software package.

Publication bias was not assessed because the number of trials (< 10) was inadequate to properly examine a funnel plot or to use more advanced regression-based assessments [23].

Results

We identified 12 cardiovascular outcome trials for type 2 diabetes drugs (Table 1); however, only 8 had all the data required to perform our analysis (Table 2). The CANVAS trial provided the number of cases but without the number of patients in each subgroup, therefore, we could not obtain the RR and compare it with RRs from other trials. The TECOS trial did not provide the event number in the placebo group with baseline insulin. REWIND did not provide number of events in the insulin at baseline subgroup, and last, the ELIXA trial did not provide the number of primary outcome events in the group taking insulin at baseline.

Table 1.

All published cardiovascular outcome trials for new diabetes mellitus type 2 drugs

| Trial | Drug | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|

| CANVASa [9] | Canagliflozin | SGLT-2 inhibitor |

| EMPA-REG [10] | Empagliflozin | SGLT-2 inhibitor |

| DECLARE–TIMI 58 [11] | Dapagliflozin | SGLT-2 inhibitor |

| ELIXAa [12] | Lixisenatide | GLP-1 receptor agonist |

| EXSCEL [13] | Exenatide | GLP-1 receptor agonist |

| HARMONY [14] | Albiglutide | GLP-1 receptor agonist |

| SUSTAIN-6 [15] | Semaglutide | GLP-1 receptor agonist |

| LEADER [16] | Liraglutide | GLP-1 receptor agonist |

| EXAMINE [17] | Alogliptin | DPP-4 inhibitor |

| SAVOR-TIMI 53 [18] | Saxagliptin | DPP-4 inhibitor |

| TECOSa [19] | Sitagliptin | DPP-4 inhibitor |

| REWIND [24] | Dalaglutide | GLP-1 receptor agonist |

Abbreviations: DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; SGLT-2, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors.

aTrials were excluded for lack of data.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Trial | Drug | Mean age, y | Duration of diabetes, y | No. of patients | Mean HgA1c, % | No. of patients on insulin at baseline | No. of patients not on insulin at baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMPA-REG [10] | Empagliflozin | 63 | 57% of patients > 10 y | 7028 | 8.1 | 3387 | 3633 |

| DECLARE–TIMI 58 [11] | Dapagliflozin | 64 | 11 | 17 160 | 8.3 | 7013 | 10 147 |

| EXSCEL [13] | Exenatide | 62 | 12 | 14 752 | 8.0 | 6836 | 7916 |

| HARMONY [14] | Albiglutide | 64 | 14 | 9463 | 8.7 | 5597 | 3866 |

| SUSTAIN-6 [15] | Semaglutide | 65 | 14 | 3297 | 8.7 | 1913 | 1384 |

| LEADER [16] | Liraglutide | 64 | 13 | 9340 | 8.7 | 4169 | 5171 |

| EXAMINE [17] | Alogliptin | 61 | 7.2 | 5380 | 8.0 | 1605 | 3775 |

| SAVOR-TIMI 53 [18] | Saxagliptin | 65 | 10 | 16 492 | 8.0 | 6832 | 9660 |

| Total patients | – | – | – | – | – | 37 352 (45%) | 45 552 (55%) |

Abbreviation: HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c.

For our analysis, we included 8 CVOTs for the type 2 diabetes drug therapy: 2 studies of SGLT-2, 4 studies of GLP-1, and 2 studies of DPP-4.

The EXAMINE and SAVOR-TIMI 53 trials were removed for the sensitivity analysis, given that DPP-4 inhibitor drugs did not show cardiovascular benefit in their individual trials, so 6 CVOTs that consisted of 2 SGLT-2 inhibitors and 4 GLP-1 agonists were included.

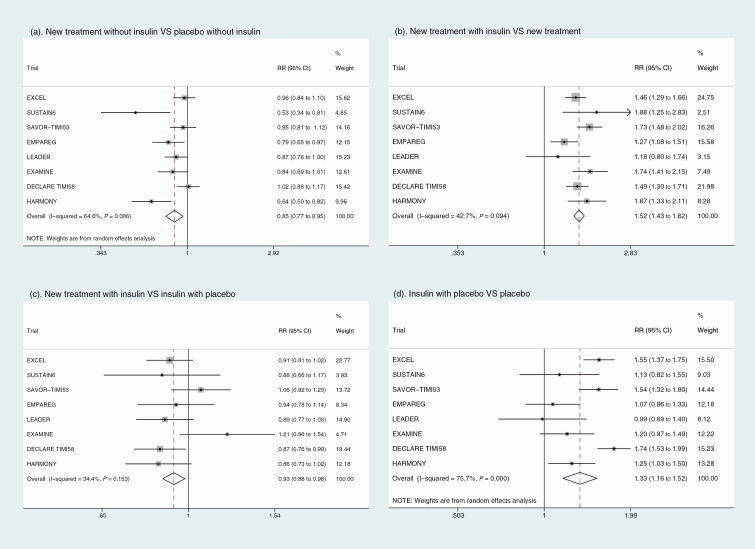

The main meta-analysis results of 4 forest plots with RRs (95% CIs) for 4 group sets are shown in Fig. 2. Plot A compares the investigational drug with the placebo, which was the primary objective of each of the individual trials. Plot B compares patients using the investigational drug with insulin at baseline with patients using the drug with no insulin at baseline. Plot C compares patients using insulin at baseline and the investigational drug with patients using insulin at baseline and placebo. Finally, plot D compares patients using insulin at baseline and placebo with patients not using insulin at baseline and also receiving placebo.

Figure 2.

Results of meta-analysis.

As shown in Fig. 2A, the pooled RR of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.77 ~ 0.95) indicated that treatment with any new antidiabetic drugs but without insulin for type 2 diabetes was significantly associated with cardiovascular benefit compared with patients in the placebo group without insulin treatment at baseline. In patients who received insulin treatment at baseline, there was still a significant benefit in cardiovascular risk reduction with the study drug with an RR of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.88 ~ 0.98) as shown in Fig. 2C. Adverse effects on cardiovascular outcomes were significantly associated with baseline insulin treatment in type 2 diabetes patients both for the drug treatment groups (Fig. 2B) and placebo groups (Fig. 2D) with an RR of 1.52 (95% CI, 1.43 ~ 1.62) and 1.33 (95% CI, 1.16 ~ 1.52), respectively. The random-effects model was applied in group A and group D separately because there was significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) for the association between diabetes treatment and risk of cardiovascular outcomes.

After excluding the 2 DPP-4 inhibitor studies, the associations of new treatment vs placebo were similar and statistically significant after the sensitivity analysis was performed, with an RR of 0.83 (95% CI, 0.72 ~ 0.96) as shown in Fig. 3A. There was a statistically significant association shown in Fig. 3C; patients who were treated with baseline insulin and the drug were less likely to experience cardiovascular events compared with those who received just baseline insulin and the placebo in trials, with an RR of 0.89 (95% CI, 0.84 ~ 0.95). We found a statistically significant RR for cardiovascular events, 1.46 (95% CI, 1.35 ~ 1.57), when comparing patients receiving the drug treatment and baseline insulin with those who received drug treatment alone (Fig. 3B. Comparing patients who received placebo treatment with insulin at baseline compared to placebo treatment only in Fig. 3D, the RR is also statistically significant at 1.30 (95% CI, 1.09 ~ 1.56).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis after excluding studies of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4).

Discussion

This meta-analysis of CVOTs demonstrates that prior insulin treatment may attenuate the benefit seen with GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors when used in combination with insulin. Recent trials have shown that canagliflozin, an SGLT-2 inhibitor, lowered the risk of cardiovascular events [9], while empagliflozin and dapagliflozin had lower rates of cardiovascular outcomes and death [10, 11]. GLP-1 agonists trials showed that lixisenatide and exenatide did not have a significant difference in cardiovascular outcome when they were compared to placebo [12, 13]. Meanwhile, albiglutide was shown to have cardiovascular benefit [14], while semaglutide decreased the rates of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke [15]. Another CVOT showed that the rate of first occurrence of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke was lower in the group that took liraglutide [16].

For those participants without baseline insulin, participants who received the investigational drug treatment had a lower risk of suffering from cardiovascular events. This result was expected given that most of these drugs provided cardiovascular benefit in their trials.

The cardiovascular events in the group that used insulin at baseline with the diabetes type 2 drugs had fewer events, with an RR of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.88-0.98), compared to the placebo group that used insulin at baseline. When the sensitivity analysis was conducted, this result was still statistically significant, with an RR of 0.89 (95% CI, 0.84-0.95). There were fewer MACE outcomes in the groups that were treated with insulin at baseline with the drugs added, showing that the benefit of GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT-2 inhibitors remains evident in insulin-treated patients, although the benefit is less than in patients who never received insulin. It is also important to note that not all GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors have similar benefits.

Next, we compared cardiovascular outcomes in the group that used insulin with the investigational drugs vs the group that used the drugs without insulin at baseline, which was the primary objective of this meta-analysis. The group that used insulin and the drugs had more cardiovascular events than those that did not use insulin at baseline, with an RR of 1.52 (95% CI, 1.43-1.62). Results were consistent in the sensitivity analysis, with an RR of 1.46 (95% CI, 1.35-1.57). The results of comparing the event rate in the group that used placebo with insulin vs the group that used placebo only was also consistent; it showed the group that used both insulin and placebo had more cardiovascular events, with an RR of 1.33 (95% CI, 1.16-1.52). The result in the sensitivity analysis was still significant and comparable, with an RR of 1.30 (95% CI, 1.09-1.56).

These results show that patients using insulin had more cardiovascular events whether or not they used the new diabetes drugs. Our hypothesis for explaining the trend was that patients who were using insulin at baseline had diabetes for a longer duration, probably had worse control and severer disease requiring insulin treatment, and therefore were at higher risk for diabetes complications including cardiovascular disease.

Cosmi et al analyzed 2 data sets that included 24 012 heart failure patients; this data were obtained from 4 large, randomized trials and an administrative database of 4 million patients [20]. Patients who had diabetes and were treated with insulin had more severe heart failure than patients who were not taking insulin. Patients who were taking insulin had higher rates of mortality and heart failure hospitalizations. The survival was also lower in this group. The authors proposed the rationale behind the results was that insulin causes sodium and water retention, and hypoglycemia was also more common, which caused adrenergic activations, myocardial ischemia leading to lethal arrythmia, and causing a prothrombotic state [20]. However, the study was performed in the highest-risk patients and the results may not apply to a less severe disease state.

Mendez and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional to evaluate the insulin effect on clinical outcomes including mortality, MACE, and DKD. They analyzed 3124 diabetes patients using the NHANES database from 2001 to 2010, segregating the patients into high or low Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) groups. Results showed that there was a significant association between insulin use and increased mortality, MACE, and DKD in the high HOMA-IR group, but this relationship was not significant in low HOMA-IR group [21]. Although the lack of randomization and interaction with insulin sensitivity makes the data less useful in clinical practice, this study suggested that insulin therapy may be less beneficial and potentially harmful for patients with high insulin resistance. Cardioprotective drugs might be deployed earlier to prevent the adverse effect of insulin resistance.

It is critical that we clarify we are not advising against the use of insulin. Multiple randomized controlled trials have provided evidence that insulin is necessary to achieve glycemic control and is not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. A literature review of all randomized clinical trials (20) analyzing insulin against diabetes type 2 drugs between 1950 and 2013 showed that insulin had no effect on all-cause mortality, with an RR of 0.99 (95% CI, 0.92-1.06) or cardiovascular mortality, with an RR of 0.99 (95% CI, 0.77-1.18) [25].

The strength of our meta-analysis lies in the large population of 82 904 patients; of these, 37 352 used insulin at baseline, whereas 45 552 did not. The trials were well conducted with robust adjudications of events. The weakness of our analysis is mostly that we were unable to include all the CVOTs, and inaccessibility to patient level data. We also attempted to stratify patients by insulin use duration and diabetes severity; however, most of the studies did not provide the data needed. Some attempts were made to obtain patient-level data; however, no data were obtained. We did not try to contact the authors directly for the missing data. The lack of patient-level data also limited the adjustment for patient characteristics. In addition, most of these trials attempted to achieve glycemic equipoise between treatment group and placebo group by adding medication. We are unable to gauge the confounding effect of this postrandomization treatment on our results.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis shows that in the recent CVOTs for diabetes type 2 drugs, the use of these drugs (GLP-1 agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors) led to a reduction in cardiovascular events; this was seen whether or not patients were using insulin at baseline. The cardiovascular benefit was significantly less though when patients were using insulin at baseline. We believe that as the disease progresses the benefit is attenuated, therefore it may be important to use these drugs early on in the disease before it progresses, and even in insulin-treated patients, there is still a cardiovascular benefit gained when a GLP-1 or an SGLT-2 inhibitor is added to the treatment regimen. The need for insulin may serve as a surrogate marker of likelihood of lower benefit.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this work was presented orally at the American Diabetes Association 79th Scientific Sessions; June 7-11, 2019, in San Francisco, California.

Author Contributions: J.E.K. performed most of the database search, data collection, and writing of the manuscript. Y.S. conducted the data analysis under L.S.’s supervision and wrote the “Materials and Methods” and “Results” sections. V.A.F. is the guarantor of this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CVOTs

cardiovascular outcome trials

- DKD

diabetic kidney disease

- DPP-4

dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin A1c

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance

- HR

hazard ratio

- MACEs

major adverse cardiovascular events

- RR

risk ratio

- SGLT-2

sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors

Additional Information

Disclosures: J.E.K., Y.S., and L.S. have nothing to disclose. V.A.F. is supported in part by the Tullis—Tulane Alumni Chair in Medicine, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant No. U54 GM104940), which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. V.A.F. discloses research support (to Tulane) from grants from Bayer and Boehringer Ingelheim; honoraria for consulting and lectures from Takeda, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli, Abbott, Astra-Zeneca, Intarcia, and Asahi; stock options from Microbiome Technologies, Insulin Algorithms, and BRAVO4Health; and stock in Amgen.

Data Availability

Some or all data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Bullard KM, Cowie CC, Lessem SE, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in adults by diabetes type—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(12):359-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study. JAMA. 1979;241(19):2035-2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(4): 229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abbott RD, Donahue RP, Kannel WB, Wilson PW. The impact of diabetes on survival following myocardial infarction in men vs women. The Framingham Study. JAMA. 1988;260(23):3456-3460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herlitz J, Karlson BW, Edvardsson N, Emanuelsson H, Hjalmarson A. Prognosis in diabetics with chest pain or other symptoms suggestive of acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 1992;80(3-4):237-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miettinen H, Lehto S, Salomaa V, et al. Impact of diabetes on mortality after the first myocardial infarction. The FINMONICA Myocardial Infarction Register Study Group. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(1):69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGuire DK, Marx N, Johansen OE, Inzucchi SE, Rosenstock J, George JT. FDA guidance on antihyperglyacemic therapies for type 2 diabetes: one decade later. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(5):1073-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holman RR, Sourij H, Califf RM. Cardiovascular outcome trials of glucose-lowering drugs or strategies in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;383(9933):2008-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. ; CANVAS Program Collaborative Group Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):644-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. ; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. ; DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):347-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. ; ELIXA Investigators Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2247-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. ; EXSCEL Study Group Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1228-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hernandez AF, Green JB, Janmohamed S, et al. ; for the Harmony Outcomes committees and investigators Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Harmony Outcomes): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1519-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marso SP, Holst AG, Vilsbøll T. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):891-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. ; LEADER Steering Committee; LEADER Trial Investigators Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, et al. ; EXAMINE Investigators Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1327-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. ; SAVOR-TIMI 53 Steering Committee and Investigators Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1317-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, et al. ; TECOS Study Group Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):232-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cosmi F, Shen L, Magnoli M, et al. Treatment with insulin is associated with worse outcome in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(5):888-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mendez CE, Walker RJ, Eiler CR, et al. Insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes and high insulin resistance is associated with increased risk of complications and mortality. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:376-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. ; PRISMA-P Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higgins JPT, Green S.. Recommendations on Testing for Funnel Plot Asymmetry. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. ; REWIND Investigators Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Erpeldinger S, Rehman MB, Berkhout C, et al. Efficacy and safety of insulin in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Endocr Disord. 2016;16(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.