Abstract

Background

Female sex is a known risk factor for drug-induced long QT syndrome (diLQTS). We recently demonstrated a sex difference in apamin-sensitive small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) current (IKAS) activation during β-adrenergic stimulation.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that there is a sex difference of IKAS in the rabbit models of diLQTS.

Methods

We evaluated the sex differences in ventricular repolarization from 15 male and 22 female Langendorff-perfused rabbit hearts with optical mapping techniques during atrial pacing. HMR1556 (IKs blocker), E4031 (IKr blocker) and sea anemone toxin (ATX-II, INaL activator) were used to simulate types 1-3 LQTS, respectively. Apamin, an IKAS blocker was then added to determine the magnitude of further QT prolongation.

Results

HMR1556, E4031 and ATX-II led to APD80 prolongation in both male and female ventricles at pacing cycle lengths (PCLs) of 300-400 ms. Apamin further lengthened APD80 (in PCL350 ms) from 187.8±4.3 to 206.9±7.1 (p=0.014) in HMR1556 treated, from 209.9±7.8 to 224.9±7.8 (p=0.003) in E4031 treated, and from 174.3±3.3 to 188.1±3.0 (p=0.0002) in ATX-II treated female hearts. In contrast, apamin did not further lengthen the APD80 in male hearts. Compared with the baseline, the Cai transient duration (CaiTD) was significantly increased in diLQTS but without sex differences. There were no significant effects of apamin on CaiTD.

Conclusion

We conclude that IKAS is abundantly increased in female but not in male ventricles with diLQTS. Increased IKAS helps preserve the repolarization reserve in female ventricles treated with IKs and IKr blockers or INaL activators.

Keywords: Calcium transient, ion currents, optical mapping, repolarization reserve, SK current

Introduction

Drug-induced long QT syndrome (diLQTS) is the most common reason that prevents a drug from reaching the market.1 The most common type of diLQTS is due to the inhibition of the rapid component of the delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr).2 Cardiac repolarization is controlled by the balance between outward and inward ionic conductances during the plateau phase of the action potential.3 Mutations of KCNQ1 (IKs), KCNH2 (IKr) and SCN5A (INaL) genes cause long QT syndrome (LQTS) types 1-3, respectively.4 However, family members with the same genetic mutations may have vastly different QT intervals,5, 6 indicating that other factors may potentially play a role in determining the QT interval in patients with congenital LQTS.6-8 Apamin-sensitive small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (SK) current (IKAS) is present but not active or only minimally active in the normal ventricles.9, 10 However, IKAS is abundantly present in heart failure, myocardial infarction and hypokalemia when repolarization reserve is reduced.11-13 We recently documented that β-adrenergic stimulation activates ventricular IKAS in females to a much greater extent than in males.14 We hypothesize that (1) IKAS is activated in rabbit ventricles in diLQTS, and (2) the magnitude of IKAS activation during diLQTS is greater in female than in male ventricles. We performed an optical mapping study in Langendorff-perfused normal rabbit ventricles to test these hypotheses.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Indiana University School of Medicine and the Methodist Research Institute and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Surgical preparations

Adult New Zealand White rabbits (N=37, 2.7-3.5 Kg) were euthanized by intravenous sodium pentobarbital overdose (160 mg/kg, i.v.). Hearts were harvested and Langendorff perfused with 37°C Tyrode solution (in mmol/L: NaCl 128.3, KCl 4.7, NaHCO3 20.2, NaH2PO4 0.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgSO4 1.2, glucose 11.1 and bovine serum albumin 40 mg/L) bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 to maintain a pH of 7.4. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Pseudo-electrocardiogram (pECG) was simultaneously recorded by placing widely spaced electrodes close to the right atrium (RA) and the apex of the left ventricle (LV), respectively, to determine the QT interval and ventricular rhythm. The signals were band-pass filtered between 0.5 Hz to 150 Hz with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz. The pECG traces and methods of QT measurements are shown in Figure 1.

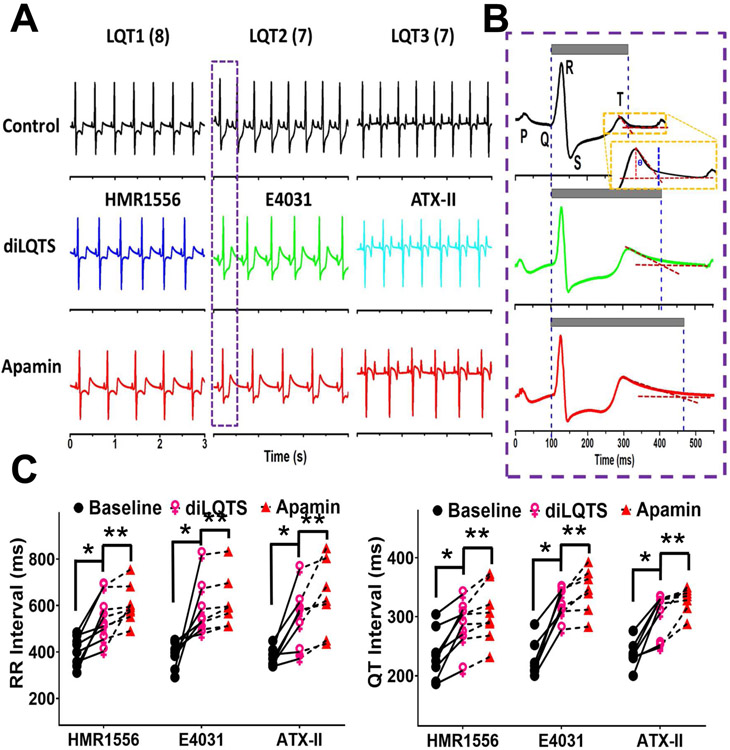

Figure 1.

Sinus bradycardia of diLQT1, diLQT2 and diLQT3 in ex vivo female rabbit hearts. A, representative pseudo ECG traces of diLQT1 (HMR1556, 100 nmol/L), diLQT2 (E4031, 50 nmol/L), and diLQT 3 (ATX-II, 20 nmol/L). Apamin (100 nmol/L) was then given during continued drug infusion. B, magnified figures showing the typical ECG traces from the box in (A), schematic illustration of the tangent method to define the T-wave end. The gray bars indicate the QT interval. C, Linkage graphs show the alterations of the RR and QT intervals in different types of diLQTS. There are significant (p<0.05) differences between baseline and diLQTS (*) as well as between diLQTS and post-apamin (**).

Optical mapping

Simultaneous optical mapping of intracellular calcium (Cai) and membrane potential (Vm) was performed using previously reported techniques.14 The hearts were stained with Rhod-2 AM (1.4 μmol/L, from Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for Cai mapping and RH237 (10 μmol/L, from Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for Vm mapping. Blebbistatin (15~20 μmol/L, from Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN) was used to inhibit contraction. The epicardial surfaces of the right and left ventricles were excited with a laser (Verdi G5, Coherent Inc., Santa Clara, CA) at a wavelength 532 nm, and the emitted fluorescence was filtered with a 715 nm long pass filter. The fluorescence was recorded with 100 x 100 pixels for a spatial resolution of 0.35 x 0.35 mm2 per pixel at a 2-ms/frame sampling rate. Optical signals were processed with both spatial and temporal filtering. A dynamic atrial pacing protocol was performed and the optical signals were recorded at different pacing cycle lengths (PCLs).15 When comparing action potential duration (APD) among baseline and after each treatment, we paced the right atrial at fixed PCL (S1S1) to avoid rate-dependent APD changes. The slowest pacing rate is limited by the competing sinus or escape rates of the Langendorff perfused hearts. We were unable to consistently pace with PCL longer than the sinus cycle length (250-400 ms). We started to acquire optical mapping signals after at least 30 paced beats at the same PCL. The PCLs were progressively shortened (400, 350, 300, 250, 200, and 170 ms) until the loss of 1:1 capture. APD at 80% repolarization (APD80) were used for data analyses. We did not use programmed stimulation to induce arrhythmias. In all protocols, the drugs were sequentially added and recirculated in the perfusate.

Protocol-I (diLQT1):

Epicardial optical signals were mapped sequentially at baseline, after adding HMR1556 (IKs blocker) to simulate type 1 LQTS, after adding apamin in the continued presence of HRM1556 and after washout. This study was performed in a total 5 male and 8 female rabbit hearts. The optical voltage signals were obtained from the anterior surface of the heart including both right ventricle (RV) and left ventricle (LV). The annotated RV/LV locations and image data acquisition procedures are shown in Online Supplement Figure 1. After baseline recording, HMR1556 (100 nmol/L) was added to the perfusate. APD measurement was performed 15 min after HMR1556 infusion. Apamin (100 nmol/L) was subsequently added in the continued presence of HMR1556. All drugs were washed out 15 min after apamin infusion. The APDs were measured at least twice in pharmacological steady-state. All experiments were completed within 1.5 hr to minimize phototoxicity induced by long-term laser exposure in these ex vivo ventricles.

Protocol-II (diLQT2):

Epicardial mapping of both the RV and the LV was conducted at baseline, after adding E4031 (IKr blocker, 50 nmol/L), after adding apamin (100 nmol/L) in the continued presence of E4031 and after washout. This protocol was performed in 6 male and 7 female hearts.

Protocol-III (diLQT3):

Epicardial mapping of both the RV and the LV was conducted at baseline, after adding sea anemone venom (ATX-II, 20 nmol/L), after adding apamin (100 nmol/L) in the continued presence of ATX-II and after washout. ATX-II is a specific late sodium channel (INaL) enhancer.16 This protocol was done in 4 males and 7 females.

Statistical analysis

APD80 was optically measured at the level of 80% repolarization. Calcium transient duration at the level of 80% (CaiTD80) were used as the index of total Cai duration. We averaged the APD in the region of interests and presented them in summary data. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SEM. Paired t-tests were used to compare two different treatments in the same rabbit ventricle. One-way repeated measures ANOVA with post-hoc tests were used to compare the means among three or more different variables. We used the correlation of variance generated from the optically imaged region to quantify APD heterogeneity.17 A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

diLQTS is associated with IKAS activation in female ventricles

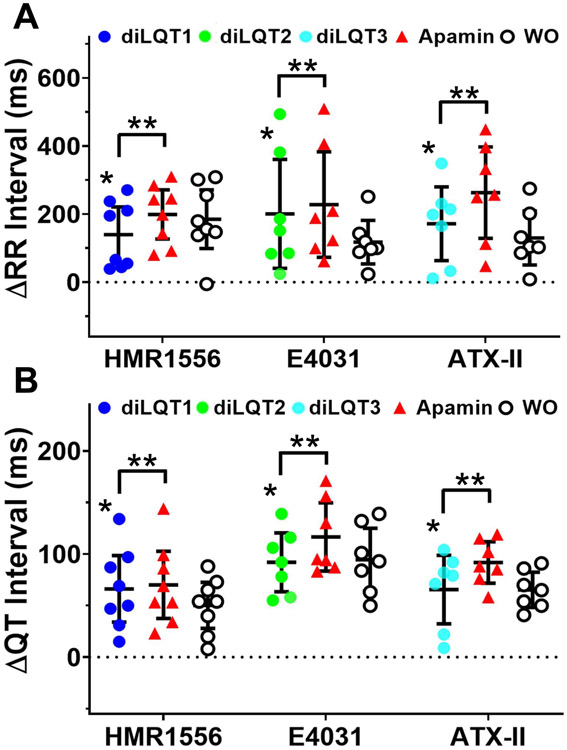

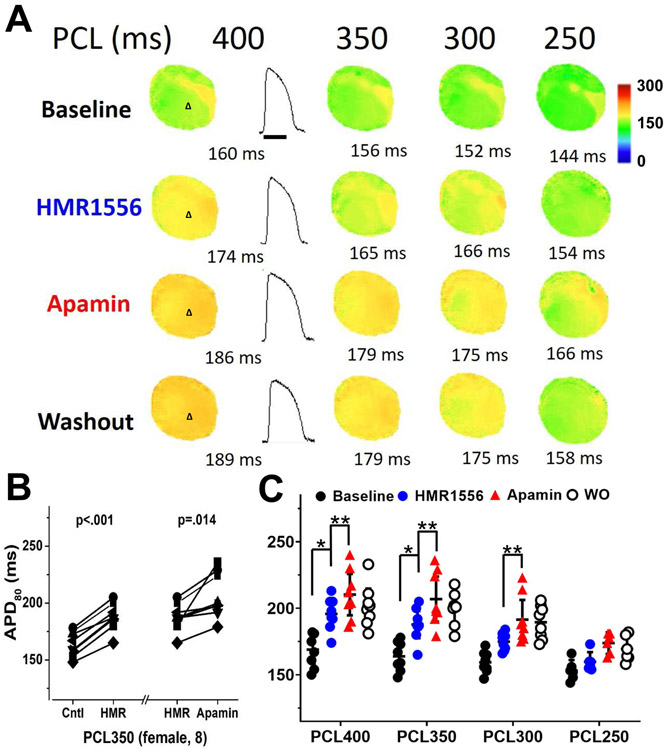

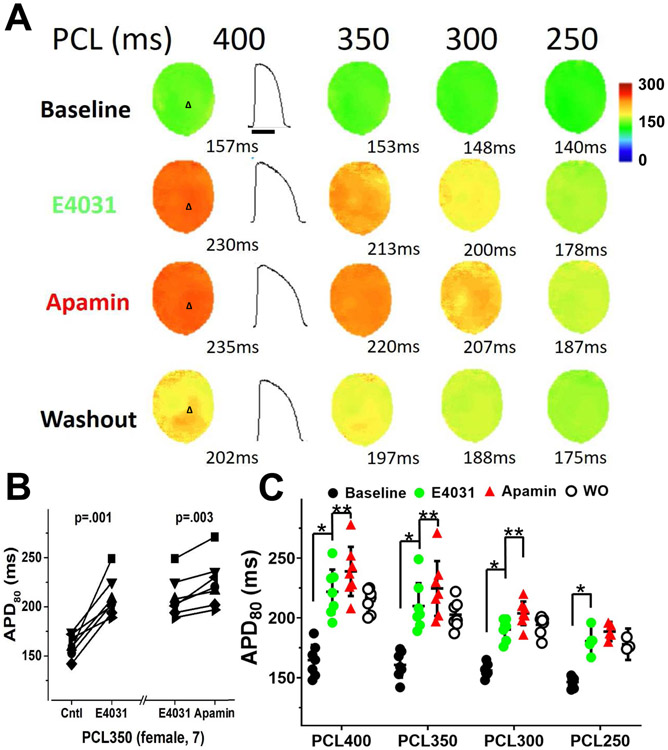

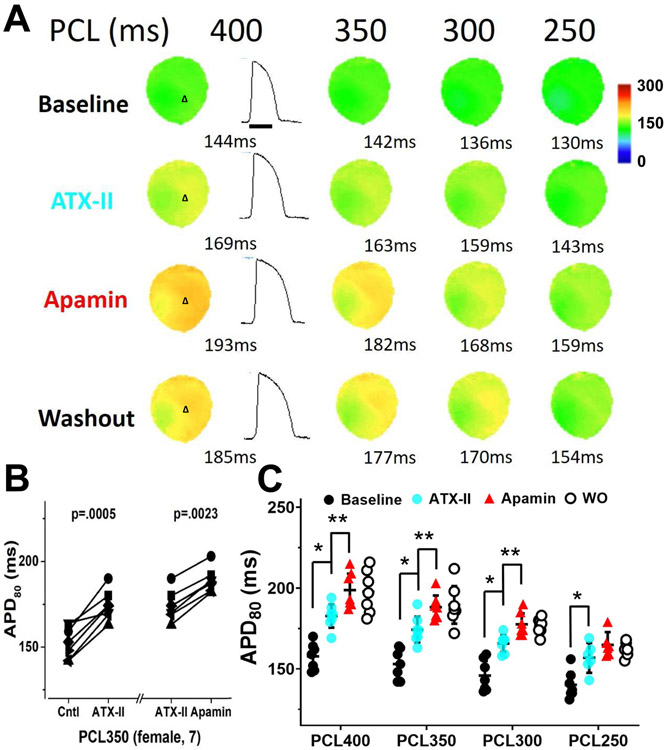

We were unable to measure heart rate-controlled QT intervals at a fixed pacing cycle lengths (PCLs) because of the superimposition of the atrial pacing artifacts with the terminal portion of the preceding T wave. Representative examples of pECG recordings and QT interval measured during sinus rhythm are shown in Figure 1A and Figure 1B, respectively. HMR1556, E4031 and ATX-II all significantly prolonged RR interval (reduced sinus heart rate) in these female hearts. Figure 1C shows that all 3 drugs significantly increased the average RR intervals and the sinus QT intervals. T-wave end was determined by tangent method as shown in Figure 1B.18 Apamin further prolonged sinus QT intervals, indicating the diLQT 1-3 were associated with the increased IKAS. However, apamin failed to prolong QT intervals in male hearts (Online Supplement Figure 2). The other sinus rhythm parameters (P, PR, and QRS) were not changed by drug treatments. Figure 2 shows the changes (delta) of RR and QT intervals from baseline in female hearts, showing significant increments after drugs and further increase after apamin. Table 1A shows the actual QT intervals of male and female hearts measured during sinus rhythm. We have removed 2 (1 male and 1 female) hearts with diLQT1, 2 (both female) from diLQT2 and 2 (both male) from diLQT3 groups due to third degree AV block. The data from those hearts were excluded from analyses. Figure 3A shows that the APD80 was increased by HMR1556 (100 nmol/L) at all PCLs. However, the increases were more apparent at longer PCL (350 ms) than at shorter PCLs (300 and 250 ms). The APD80 was further increased by apamin (100 nmol/L) (Figure 3B and 3C). Table 1B shows HMR1556 prolonged the APD80 in female ventricles. These results indicated that IKAS is functionally elevated during the diLQT1 at longer PCLs. Similar results were demonstrated in the diLQT2 model as shown in Figure 4. E4031 (50 nmol/L), the IKr blocker, significantly prolonged APD80. While female ventricles had greater prolongation than male ventricles, the difference was statistically insignificant (Table 1B). Subsequent addition of apamin further increased the APD80. The numeric results are displayed in Table 1B. Figure 4C shows that APD80 was significantly lengthened by E4031 at PCLs longer than 250 ms.

Figure 2.

Effects of drugs and apamin on RR and QT intervals in female hearts. A, differences (delta) in RR intervals between treatments and baseline. The delta between RR interval and baseline was statistically significant both after drug and after apamin. B, the delta QT interval at different stages of the experiment. The delta QT interval was increased by the drugs and by apamin. The RR and QT intervals were only partially reduced after attempted washout (WO). Asterisks (*diLQTS compared with baseline; **diLQTS compared with post-apamin) represent significant differences (p<0.05, each n=7-8).

Table 1.

Effects of apamin on repolarization and calcium transients

| A. ECG QT intervals during sinus rhythm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Sex | Sinus QT | QT (diLQTS) | QT (apamin) | n |

| IKs (HMR1556) | Male | 229.8 ± 11.6 | 295.4 ± 17.1 * | 303.4 ± 18.9 | 5 |

| Female | 220.8 ± 7.8 | 284.5 ± 14.9 * | 304.6 ± 18.1 ** | 8 | |

| IKr (E4031) | Male | 235.7 ± 8.6 | 319.2 ± 12.3 * | 325.8 ± 11.7 | 6 |

| Female | 228.0 ± 11.7 | 320.0 ± 9.4 * | 344.6 ± 14.2 ** | 7 | |

| INa,L (ATX-II) | Male | 221.3 ± 11.3 | 287.3 ± 8.4 * | 293.5 ± 6.6 | 4 |

| Female | 234.4 ± 6.3 | 302.1 ± 13.8 * | 328.7 ± 8.1 ** | 7 | |

| *p<0.05 compared with baseline; **p<0.05 compared with diLQTS; time scale: ms. | |||||

| B. Optical mapping APD during atrial pacing with cycle length of 350 ms | |||||

| Type | Sex | Baseline APD80 | ΔAPD80 (diLQTS) | ΔAPD80 (apamin) | n |

| IKs (HMR1556) | Male | 162.0 ± 3.6 | 23.8 ± 3.0 * | −0.2 ± 1.8 | 5 |

| Female | 163.9 ± 3.9 | 23.9 ± 1.9 * | 19.1 ± 5.9 ** | 8 | |

| IKr (E4031) | Male | 166.3 ± 4.8 | 37.0 ± 6.0 * | −2.3 ± 2.8 | 6 |

| Female | 160.7 ± 4.3 | 49.1 ± 8.0 * | 14.7 ± 2.9 ** | 7 | |

| INa,L (ATX-II) | Male | 161.8 ± 5.5 | 22.3 ± 3.9 * | −0.8 ± 1.5 | 4 |

| Female | 158.0 ± 3.5 | 21.3 ± 2.9 * | 13.9 ± 1.6 ** | 7 | |

| *p<0.05 compared with baseline; **<0.05 compared with males; time scale: ms. | |||||

| C. Optical mapping CaiTD during atrial pacing with cycle length of 350 ms | |||||

| Type | Sex | Baseline CaiTD80 | ΔCaiTD80 (diLQTS) | ΔCaiTD80 (apamin) | n |

| IKs (HMR1556) | Male | 185.0 ± 1.6 | 29.4 ± 3.3 * | −0.6 ± 4.1 | 5 |

| Female | 184.5 ± 2.6 | 26.5 ± 1.8 * | 1.6 ± 3.4 | 8 | |

| IKr (E4031) | Male | 185.3 ± 2.6 | 41.0 ± 4.1 * | −0.2 ± 2.9 | 6 |

| Female | 182.7 ± 1.7 | 48.4 ± 4.1 * | 3.3 ± 3.1 | 7 | |

| INa,L (ATX-II) | Male | 181.5 ± 3.6 | 35.5 ± 5.5 * | −1.5 ± 1.8 | 4 |

| Female | 181.3 ± 2.1 | 33.7 ± 3.0 * | 2.6 ± 3.2 | 7 | |

| *p<0.05 compared with baseline; time scale: ms. | |||||

Figure 3.

Changes in APD80 in female ventricles treated with HMR1556 followed by apamin and washout in a female heart. A, the color maps show epicardial APD distribution at different pacing cycle lengths (PCLs). HMR1556 (100 nmol/L) increased APD80. Apamin (100 nmol/L) further increased the APD80, and after washout (Protocol I, diLQT1). B, HMR1556 prolonged APD80. Addition of apamin further increased the APD80. APD80 is persistently prolonged after washout (WO). C, summary of these studies at different PCLs. The magnitude of APD prolongation by HMR1556 was more prominent at long PCLs than at short PCLs. The apamin further prolonged APD80 at multiple PCLs. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Asterisks (*diLQTS compared with baseline; **diLQTS compared with post-apamin) represent significant differences (p<0.05, n=8).

Figure 4.

Changes in APD80 in female ventricles treated with E4031 followed by apamin and washout. A, representative membrane potential traces and APD80 maps at baseline and in the presence of E4031 (50 nmol/L), after apamin (100 nmol/L), and after washout (Protocol II, diLQT2). B, at 350 ms PCL, E4031 (50 nmol/L) significantly prolonged APD80 and apamin further increased the APD80. APD80 is persistently prolonged after washout (WO). C, summary of apamin effects on APD80 at different PCLs. Significant effects of apamin were observed at all but 250 ms PCLs. Asterisks (*diLQTS compared with baseline; **diLQTS compared with post-apamin) represent significant differences (p<0.05, n=7).

Figure 5A shows a representative example of optical mapping and APD traces at baseline, after infusion of ATX-II (20 nmol/L), after apamin and after washout. At PCL 350 ms, ATX-II significantly prolonged APD and subsequent addition of apamin (100 nmol/L) in the continued presence of ATX-II in the perfusate further lengthened APD80 at the long, but not short, PCLs (Figure 5B and 5C).

Figure 5.

Changes in APD80 in female ventricles treated with ATX-II followed by apamin and washout. A, representative membrane potential traces and APD80 maps at baseline and in the presence of ATX-II (20 nmol/L), after apamin (100 nmol/L), and after washout (Protocol III, diLQT3). B, at 350 ms PCL, ATX-II significantly prolonged APD80 and apamin then further increased the APD80. APD80 is persistently prolonged after washout (WO). C, summary of apamin effects on APD80 at different PCLs in normal rabbit ventricles. The apamin effects were observed at multiple PCLs but not in 250 ms PCL. Asterisks (*diLQTS compared with baseline; **diLQTS compared with post-apamin) represent significant differences (p<0.05, n=7).

IKAS was not significantly activated in male diLQTS hearts

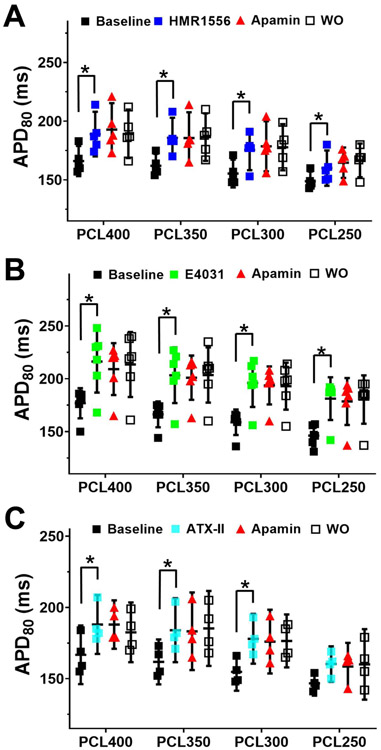

We applied the same protocol in male hearts but failed to observe APD prolongation after apamin administration in diLQTS (PCL 350 ms). No apamin effects were observed in the diLQT1, diLQT2, and diLQT3 models of male rabbit hearts (Figure 6). Table 1A shows the numeric values of the QT interval changes. Online Supplement Figures 3-5 show typical examples of experiments in male rabbit hearts. They showed that while all 3 drugs prolonged APD80 especially at longer PCLs, addition of apamin failed to further prolong APD80. The numeric values are summarized in Table 1B. These results indicated that IKAS is magnified in female but not in male ventricles of diLQTS. Apamin did not induce further changes of the APD heterogeneity in female diLQTS ventricles (PCL350 ms) (Online supplement Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Apamin did not prolong APD80 in male ventricles with diLQT1 (A), diLQT2 (B) and diLQT3 (C). There were significant APD80 prolongations after drug administration, especially at longer PCLs. However, no further prolongation was observed after apamin, indicating absence of IKAS activation in male diLQTS model. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.05, each n=4-6).

Apamin had little effects on intracellular calcium transient duration (CaiTD)

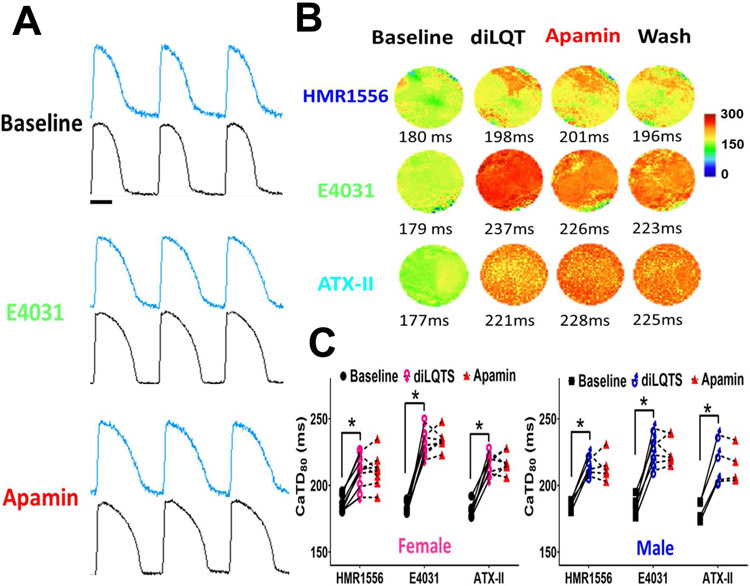

Cai mapping was simultaneously performed and analyzed (Figure 7). Compared with baseline, HMR1556 (100 nmol/L), E4031 (50 nmol/L) and ATX-II (20 nmol/L) markedly prolonged Cai transient duration. The numeric values are summarized in Table 1C. These findings indicate that CaiTD was significantly prolonged in diLQT1, diLQT2 and diLQT3. The E4031 prolonged CaiTD to a greater extent in female than in male ventricles, but the difference was statistically insignificant. Apamin (100 nmol/L) had a minimal further effect on CaiTD prolongation. The sex differences of IKAS activation could not be explained by the differential prolongation of CaiTD in male and female ventricles.

Figure 7.

Effects of IKAS blockade on CaiTD in diLQTS models. A, representative Cai (blue) and Vm (black) traces at baseline, during E4031, and after apamin (Protocol-II) at 350 ms PCL in a female heart. Compared with baseline, E4031 (50 nmol/L) markedly prolonged CaiTD80. Apamin (100 nmol/L) only slightly prolonged CaiTD, but the prolongation was statistically insignificant. B, representative CaiTD distribution maps of diLQT1 (top), diLQT2 (middle) and diLQT3 (bottom) with female hearts treated with HMR1556 (100 nmol/L), E4031 (50 nmol/L) or ATX-II (20 nmol/L), respectively, at 350 ms PCL. Addition of apamin (100 nmol/L) did not further prolong the CaiTD. C, linkage graphs show the alterations of the CaiTD80 in different types of diLQTS, neither male nor female ventricles showed CaiTD80 prolongation after adding apamin at 350 ms PCL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.05, each n=4-8).

Discussion

We found that IKAS is abundantly increased in female but not in male rabbit ventricles with diLQTS. IKAS activation helps preserve the repolarization reserve in female ventricles treated with IKs and IKr blockers or INaL activators. A clinical implication is that IKAS blockers may be proarrhythmic in female ventricles.

Significance of IKAS activation in female diLQTS

As compared with men, women have longer rate-corrected QT intervals and are more prone to QT interval prolongation and Torsade de Pointes (TdP) ventricular arrhythmias after treatment with drugs that inhibit K+ channels.19-21 A detailed understanding of proarrhythmic potential of ionic channel blockade is an important step towards the development of better antiarrhythmic strategy in female patients. The diLQTS is the single most common cause for withdrawal or restriction of the use of drugs already marketed.1 Common mechanisms of diLQTS include IKs and/or IKr blockade 2, 3 as well as INaL activation,22 although many other mechanisms also play a role.7 In rabbit models of diLQT2, adult females had significantly lower IKr and, perhaps, inward rectifying K+ current, which contributed to their longer QT interval and greater arrhythmia vulnerability compared with male rabbit counterpart.23 The present consensus is that normal female hearts express fewer functional K+ channels, resulting in longer APD.24 When treated with agents that inhibit IKr, adult females have a greater vulnerability to early afterdepolarizations (EAD) and TdP. More recent studies showed that rare variations in genes responsible for congenital arrhythmia syndromes are frequently found in diLQTS.7, 8 In addition to genetic variations, disease states such as heart failure are also a prominent risk factor of diLQTS.1

IKAS blockade and QT prolongation

Heart failure is a disease condition associated with significant SK channel upregulation. While IKAS is inactive or only minimally active in normal ventricles,9, 25 it is increased in heart failure.12, 26, 27 Failing ventricles have decreased K+ currents, increased INaL, reduced repolarization reserve and increased QT interval.28 In the meantime, it activates IKAS to preserve the repolarization reserve. Sex-specific IKAS activation in the female ventricle helps to preserve repolarization reserve when other K+ channels are suppressed or INaL is activated by drugs. Therefore, drugs that block IKAS may be more proarrhythmic in women than in men. One of the known cardiac IKAS blocker is ondansetron.29 Consistent with the importance of IKAS in female ventricles, female sex is a major risk factor for QT prolongation induced by ondansetron in patients with cardiovascular diseases.30

Cai prolongation accompanied with diLQTS as a factor for IKAS activation

Cardiac repolarization alternans often precedes life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. In alternans, Cai and Vm are coupled either positively (large Cai transient prolongs APD of the same beat) or negatively (large Cai transient shortens APD of the same beat).31 Vm and Cai are coupled via calcium sensitive currents, such as ICaL, INCX, IKs and IKAS.31, 32 The results of our study showed positive Cai-Vm coupling in diLQTS. The increased APD resulted in increased CaiTD, which in turn may contribute to the activation of calcium sensitive potassium currents, such as IKs and IKAS. In diLQT1 when IKs is inhibited, the IKAS may help maintain the repolarization reserve. However, CaiTD prolongation occurred both in male and female ventricles and the magnitudes of prolongation were not different between sexes. These findings indicate that sex-specific IKAS elevation is not secondary to differential prolongation of CaiTD.

IKAS blockade enhanced sinus bradycardias in diLQTS

Apamin is known to slow diastolic depolarization and reduce pacemaker rate in isolated sinoatrial node cells and intact tissue.33 We found that apamin amplified the diLQT-induced heart rate slowing. The effects of apamin on APD80 was greater in slower heart rates than in faster heart rates. The rate-dependent increase of IKAS suggests that IKAS is particularly important during bradycardia to maintain repolarization reserve. IKAS blockade might increase the arrhythmic risk in women with bradycardia.

Study limitations

Our findings imply that IKAS is activated in female but not in male ventricles during diLQTS. A possible contributing factor is that the subtype-2 SK channel protein expression was significantly higher in female than male rabbit ventricles.14 Furthermore, ICa,L is approximately 30% higher in female than male rabbit ventricles.24 The increased ICa,L could facilitate the activation of the IKAS.34 A limitation of the present study is that we did not directly measure the ICa,L in males and females to test the latter hypothesis. Apamin does not block any known major cardiac potassium currents.35 However, because of molecular diversity of potassium channel genes in the myocardium,36 the specificity of apamin cannot be determined until all cardiac potassium channel genes are completely characterized.

Conclusions

We conclude that IKAS is abundantly increased in female but not in male ventricles with diLQTS. Increased IKAS helps preserve the repolarization reserve in female ventricles treated with IKs and IKr blockers or INaL activators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01 (HL139829, R42DA043391, TR002208-01), the American Heart Association grant (18TPA34170284), a Charles Fisch Research Award endowed by Dr Suzanne B. Knoebel, a Medtronic-Zipes Endowment, and the Indiana University Health-Indiana University School of Medicine Strategic Research Initiative. We thank Nicole Courtney, Chris Corr, and David Adams for their assistances.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Roden DM. Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitcheson JS, Chen J, Lin M, Culberson C, Sanguinetti MC. A structural basis for drug-induced long QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:12329–12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollard CE, Abi Gerges N, Bridgland-Taylor MH, Easter A, Hammond TG, Valentin JP. An introduction to QT interval prolongation and non-clinical approaches to assessing and reducing risk. Br J Pharmacol 2010;159:12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1932–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehtonen A, Fodstad H, Laitinen-Forsblom P, Toivonen L, Kontula K, Swan H. Further evidence of inherited long QT syndrome gene mutations in antiarrhythmic drug-associated torsades de pointes. Heart Rhythm 2007;4:603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaab S, Crawford DC, Sinner MF, et al. A large candidate gene survey identifies the KCNE1 D85N polymorphism as a possible modulator of drug-induced torsades de pointes. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2012;5:91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramirez AH, Shaffer CM, Delaney JT, et al. Novel rare variants in congenital cardiac arrhythmia genes are frequent in drug-induced torsades de pointes. Pharmacogenomics J 2013;13:325–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weeke P, Mosley JD, Hanna D, et al. Exome sequencing implicates an increased burden of rare potassium channel variants in the risk of drug-induced long QT interval syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1430–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagy N, Szuts V, Horvath Z, et al. Does small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel contribute to cardiac repolarization? J Mol Cell Cardiol 2009;47:656–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang XD, Lieu DK, Chiamvimonvat N. Small-conductance Ca2+ -activated K+ channels and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:1845–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang PC, Chen PS. SK channels and ventricular arrhythmias in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2015;25:508–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua SK, Chang PC, Maruyama M, et al. Small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel and recurrent ventricular fibrillation in failing rabbit ventricles. Circ Res 2011;108:971–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YS, Chang PC, Hsueh CH, et al. Apamin-sensitive calcium-activated potassium currents in rabbit ventricles with chronic myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2013;24:1144–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen M, Yin D, Guo S, et al. Sex-specific activation of SK current by isoproterenol facilitates action potential triangulation and arrhythmogenesis in rabbit ventricles. J Physiol 2018;596:4299–4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koller ML, Riccio ML, Gilmour RF Jr. Dynamic restitution of action potential duration during electrical alternans and ventricular fibrillation. Am J Physiol 1998;275:H1635–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.el-Sherif N, Fozzard HA, Hanck DA. Dose-dependent modulation of the cardiac sodium channel by sea anemone toxin ATXII. Circ Res 1992;70:285–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin D, Yang N, Tian Z, et al. Ondansetron effects on apamin-sensitive small conductance calcium-activated potassium currents in pacing induced failing rabbit hearts. Heart Rhythm 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Postema PG, Wilde AA. The measurement of the QT interval. Curr Cardiol Rev 2014;10:287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makkar RR, Fromm BS, Steinman RT, Meissner MD, Lehmann MH. Female gender as a risk factor for torsades de pointes associated with cardiovascular drugs. JAMA 1993;270:2590–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke JH, Ehlert FA, Kruse JT, Parker MA, Goldberger JJ, Kadish AH. Gender-specific differences in the QT interval and the effect of autonomic tone and menstrual cycle in healthy adults. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:178–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drici MD, Knollmann BC, Wang WX, Woosley RL. Cardiac actions of erythromycin: influence of female sex. JAMA 1998;280:1774–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang T, Chun YW, Stroud DM, et al. Screening for acute IKr block is insufficient to detect torsades de pointes liability: role of late sodium current. Circulation 2014;130:224–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu XK, Katchman A, Drici MD, et al. Gender difference in the cycle length-dependent QT and potassium currents in rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998;285:672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sims C, Reisenweber S, Viswanathan PC, Choi BR, Walker WH, Salama G. Sex, age, and regional differences in L-type calcium current are important determinants of arrhythmia phenotype in rabbit hearts with drug-induced long QT type 2. Circ Res 2008;102:e86–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuteja D, Xu D, Timofeyev V, et al. Differential expression of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels SK1, SK2, and SK3 in mouse atrial and ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;289:H2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonilla IM, Long VP 3rd, Vargas-Pinto P, et al. Calcium-activated potassium current modulates ventricular repolarization in chronic heart failure. PLoS One 2014;9:e108824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu CC, Corr C, Shen C, et al. Small conductance calcium-activated potassium current is important in transmural repolarization of failing human ventricles. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:667–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nattel S The heart on a chip: the role of realistic mathematical models of cardiac electrical activity in understanding and treating cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 2007;4:779–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ko JS, Guo S, Hassel J, et al. Ondansetron blocks wild-type and p.F503L variant small-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018;315:H375–H388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hafermann MJ, Namdar R, Seibold GE, Page RL 2nd. Effect of intravenous ondansetron on QT interval prolongation in patients with cardiovascular disease and additional risk factors for torsades: a prospective, observational study. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 2011;3:53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss JN, Karma A, Shiferaw Y, Chen PS, Garfinkel A, Qu Z. From pulsus to pulseless: the saga of cardiac alternans. Circ Res 2006;98:1244–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy M, Bers DM, Chiamvimonvat N, Sato D. Dynamical effects of calcium-sensitive potassium currents on voltage and calcium alternans. J Physiol 2017;595:2285–2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torrente AG, Zhang R, Wang H, et al. Contribution of small conductance K+ channels to sinoatrial node pacemaker activity: insights from atrial-specific Na+ /Ca2+ exchange knockout mice. J Physiol 2017;595:3847–3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang XD, Coulibaly ZA, Chen WC, et al. Coupling of SK channels, L-type Ca(2+) channels, and ryanodine receptors in cardiomyocytes. Sci Rep 2018;8:4670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu CC, Ai T, Weiss JN, Chen PS. Apamin does not inhibit human cardiac Na+ current, L-type Ca2+ current or other major K+ currents. PLoS One 2014;9:e96691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of functional voltage-gated K+ channel diversity in the mammalian myocardium. J Physiol 2000;525 Pt 2:285–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.