Summary:

The derivation of tissue-specific stem cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) would have broad reaching implications for regenerative medicine. Here we report the directed differentiation of human iPSCs into airway basal cells (“iBCs”), a population resembling the stem cell of the airway epithelium. Using a dual fluorescent reporter system (NKX2-1GFP;TP63tdTomato) we track and purify these cells as they first emerge as developmentally immature NKX2-1GFP+ lung progenitors and subsequently augment a TP63 program during subsequent proximal airway epithelial patterning. In response to primary basal cell medium, NKX2-1GFP+/ TP63tdTomato+ cells display the molecular and functional phenotype of airway basal cells, including the capacity to self-renew or undergo multilineage differentiation in vitro and in tracheal xenografts in vivo. iBCs and their differentiated progeny model perturbations that characterize acquired and genetic airway diseases including the mucus metaplasia of asthma, chloride channel dysfunction of cystic fibrosis, and ciliary defects of primary ciliary dyskinesia.

Keywords: basal cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, directed differentiation

Graphical Abstract

eTOC

Hawkins and colleagues report a directed differentiation protocol enabling the derivation of airway basal cells (“iBCs”) from human iPSCs. iBCs recapitulate hallmark stem cell properties of primary basal cells including self-renewal and multilineage differentiation, thus enabling modeling of airway diseases in vitro, and repopulation of tracheal xenografts in vivo.

Introduction:

Basal cells (BCs) of the adult mouse and human airways are capable of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation in vivo and after culture expansion ex vivo, thereby fulfilling the definition of a tissue-specific adult stem cell (Rock et al., 2009). An extensive literature has established that BCs can regenerate the airway epithelium by serving as precursors for essential specialized epithelial cell-types including secretory cells (SCs) and multiciliated cells (MCCs) (Montoro et al., 2018; Plasschaert et al., 2018; Rock et al., 2009). These stem cell properties make BCs a highly desirable cell type to generate ex vivo for modeling airway diseases and a leading candidate for cell-based therapies designed to reconstitute the airway epithelium.

In human airways, BCs are highly abundant in the pseudostratified epithelium extending from the trachea to the terminal bronchioles (Rock et al., 2010). Airway BCs can be identified based on their classic anatomic location along the basal lamina and by the expression of several markers including Tumor Protein 63 (TP63), cytoskeletal protein Keratin 5 (KRT5) and Nerve Growth Factor Receptor (NGFR) (Rock et al., 2010). TP63, a member of the p53 family of transcription factors, is essential to the BC program in the airway but also other organs (Yang et al., 1999). While airway BCs in adult lungs have been extensively studied, only recently has their developmental origin been examined. For example, lineage-tracing experiments in mice (Yang et al., 2018) reveal that a Tp63-program is already present early in lung development at the time of initial lung bud formation (embryonic day E9.5) within a subset of lung epithelial progenitors expressing the transcriptional regulator that marks all developing lung epithelial cells, NK2 homeobox 1 (Nkx2-1). Early Nkx2-1+/Tp63+ co-expressing cells are not BCs since they lack the BC morphology and molecular program. Rather these fetal cells function as multipotent progenitors of subsequent alveolar and airway epithelia (Yang et al., 2018). Tp63 expression is then gradually restricted to the developing airways where it is initially broadly expressed in immature airway progenitors and later restricted to a subset of tracheal cells that localize to the basement membrane and upregulate markers of adult BCs, including Krt5 and Ngfr. The signaling pathways that control BC specification and maturation in the lung are not precisely known; however, in-bred mouse models suggest a temporal role for FGF10/FGFR2b (Volckaert et al., 2013) and recent single-cell RNA-Sequencing (scRNA-Seq) of human fetal airways identified fetal BCs and a role for transient activation of SMAD signaling in BC specification (Miller et al., 2020). Although limited data are available regarding the developmental origins of BCs in humans, a similar pattern to that observed in mice has also been described (Nikolić et al., 2017).

Given the stem cell properties of airway BCs including their established proliferative capacity, well-established protocols have been developed to expand primary human BCs in vitro (Fulcher and Randell, 2013; Fulcher et al., 2005; Mou et al., 2016; Suprynowicz et al., 2017). These BCs, conventionally referred to as human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs), differentiate into a pseudostratified airway epithelium in air-liquid interface (ALI) culture that recapitulates aspects of in vivo airway biology. The understanding of acquired and genetic human airway diseases, including the mucus metaplasia of asthma, the chloride transport defects of cystic fibrosis, and the ciliary dysfunction of primary ciliary dyskinesia, has advanced through this model (Clancy et al., 2019; Horani et al., 2016; Seibold, 2018).

Several recent reports have demonstrated the successful directed differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into airway epithelial cell types, including those that express the canonical BC marker TP63 (Dye et al., 2015; Hawkins et al., 2017; Konishi et al., 2016; McCauley et al., 2017). These cultures contain cells with some markers found in BCs; however, the successful generation of bona-fide BCs with detailed characterization and demonstration of stem cell properties that are comparable to adult BCs has yet to be reported.

Here we successfully differentiate iPSCs in vitro into putative BCs that share transcriptional and functional similarities to their in vivo counterparts. The resulting approach recapitulates the sequence of key developmental milestones observed in mouse and human fetal lungs. Initially primordial lung progenitors identified by NKX2-1 expression are produced with only low levels of TP63 expression detectable in a minority of cells. Subsequently, a developing airway program is induced characterized by co-expression of NKX2-1 and TP63, with subsequent maturation into cells expressing the functional and molecular phenotype of BCs. As is observed in mature primary BCs, iPSC-derived BCs (“iBCs”) express the cell surface marker NGFR that enables their purification by flow cytometry. The resulting sorted cells display long-term, clonal self-renewal capacity, multi-lineage differentiation in ALI cultures in vitro and in tracheal xenografts. iBCs can be applied for disease modeling studies, exemplified here by recapitulating essential features of asthma, Cystic Fibrosis (CF), and primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). The ability to derive tissue-specific stem cells such as airway BCs from iPSCs, including capabilities to purify, expand, cryopreserve and differentiate these cells, overcomes many of the key hurdles that currently limit the more widespread application of iPSC technology and should accelerate the study of human lung disease.

Results:

A TP63 Fluorescent Reporter Allows Visualization, Purification, and Interrogation of iPSC-derived Airway Progenitors.

Since NKX2-1 is the earliest transcriptional regulator expressed in all developing lung epithelial cells and TP63 is a canonical transcription factor required for expression of the BC program, we sought to generate a tool that would allow visualization and purification of NKX2-1+/TP63+ putative lung BCs engineered in vitro from iPSCs while excluding any non-lung BCs (NKX2-1-/TP63+) (Figure 1A-B). Using our published, normal iPSC line (BU3) that carries a GFP reporter targeted to the endogenous NKX2-1 locus (Hawkins et al. 2017), we additionally targeted a tdTomato reporter coding sequence into one allele of the endogenous TP63 locus at exon 4 to ensure reporter expression reflects expression of the predominant known forms of TP63, DeltaN-type or TA-type at the N-terminus while avoiding bias to C-terminal splice forms, such as α, β, and γ-type (Figure 1B) (Levrero et al., 2000). Karyotypically normal, pluripotent clones with monoallelic targeting of the TP63 locus and biallelic targeting of the NKX2-1 locus were identified (Figure S1A-E), thus establishing a bifluorescent reporter iPSC line, BU3 NKX2-1GFP;P63tdTomato, hereafter “BU3 NGPT”. To test faithfulness and specificity of the reporters, we differentiated this iPSC line into lung epithelium employing our recently published airway directed differentiation protocol in which we previously identified a population of basal-like cells based on the expression of NKX2-1, TP63 and KRT5 (Figure 1C) (McCauley et al. 2017). As expected, NKX2-1GFP+ (hereafter “GFP+”) cells, a small fraction of which also expressed tdTomato (hereafter “TOM+”), emerged by day 15 of differentiation as detected by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy (18.1±19% GFP+, 0.4±0.8% TOM+, mean±SD). In the experiment shown in Figure 1E 45.4% of cells were GFP+ and 2.5% of cells were GFP+/TOM+ (Figure 1D-E). Almost all TOM+ cells identified at this time point expressed the lung epithelial lineage GFP reporter (Figure 1E). We previously determined that GFP+ cells at this stage of the differentiation are similar to primordial lung progenitors and do not express canonical markers of extra-pulmonary NKX2-1 domains, which include the forebrain and thyroid (Hawkins et al., 2017; Serra et al., 2017).

Figure 1: Generation of a dual fluorescent NKX2-1GFP;TP63tdTomato iPSC reporter to track and purify putative basal cells.

(A) Adult human airway immunolabeled with the antibodies indicated (DNA stained with Hoechst; scale bar=10μm).

(B) Schematic of gene-editing strategy to insert tdTomato sequence into one allele of the TP63 locus of NKX2-1GFP iPSCs. See supplemental Figure 1 for further details.

(C) Schematic of airway directed differentiation protocol. NKX2-1GFP+ cells are indicated in green, TP63tdTomato+ in red and co-expression in orange.

(D) Representative image of BU3 NGPT spheroid on day 36 of differentiation demonstrating GFP and tdTomato fluorescence (scale bar=50μm).

(E) Representative flow cytometry plots of NKX2-1GFP vs TP63tdTomato expression on days 0, 15 and 35 of directed differentiation.

(F) Quantification of the percentage of cells, calculated by flow cytometry, co-expressing NKX2-1GFP and TP63tdTomato between days 15-16 and 40-42 of differentiation (n=6).

(G) qRT-PCR quantification of TP63 mRNA levels (2−ΔΔCt) in GFP+/TOM+, GFP−TOM−, and GFP+/TOM− populations sorted by FACS compared to presort levels on day 36 of directed differentiation.

(H) Immunolabeling of BU3 NGPT with antibodies against TP63 and RFP on day 30 of directed differentiation. The cells remained in 2D culture from day 15 to facilitate antibody labeling (DNA stained with DAPI; scale bar=50μm).

To induce proximal airway differentiation of lung progenitors, GFP+ cells (regardless of TOM expression) were sorted on day 15 of the protocol and suspended in droplets of Matrigel in our previously published “airway” serum-free medium, hereafter “FGF2+10+DCI+Y” (Figure 1C schematic) (McCauley et al. 2017). Between days 28-36, monolayered epithelial spheres emerged and 43.7±8.6% (mean±SD, 46.6% GFP+, 24.6% GFP+/TOM+ in the experiment shown in Figure 1E) of cells co-expressed NKX2-1GFP and TP63TOM, hereafter “GFP+/TOM+” (Figure 1E-F). A single input GFP+ cell on day 15 yielded 15.7±8.25 GFP+/TOM+ cells by day 30-35. After single-cell dissociation of epithelial spheres and expansion in 3D culture conditions, the percentage of cells GFP+/TOM+ increased further to 73.7±4.7% by day 42 (Figure 1F). Flow cytometry sorting on day 36 demonstrated enrichment of TP63 mRNA in GFP+/TOM+ cells and depletion in TOM− cells (Figure 1G). TP63 protein was detected in TOM+ cells, however, TOM− cells lacked TP63 protein (Figures 1H, S1F). These confirmed the specificity of the tdTomato reporter. In summary, we determined that NKX2-1GFP+/TP63TOM+ cells emerge and can be expanded in FGF2+10+DCI+Y medium. The early emergence of tdTomato expression in some cells beginning around day 15 is in keeping with our prior observations in vitro (Hawkins et al. 2017; McCauley et al. 2017; McCauley et al. 2018) and in vivo (Y. Yang et al. 2018; Nikolić et al. 2017) that Tp63 mRNA and nuclear protein are initially detected at this time point in a subset of early NKX2-1+ primordial lung epithelial progenitors soon after specification of the respiratory lineage even prior to airway differentiation (see schematic Figure 1C).

iPSC-derived Airway Progenitors Adopt a Molecular Phenotype Similar to Primary Adult Basal Cells.

We next sought to characterize NKX2-1GFP+/TP63TOM+ cells produced by the airway differentiation protocol in terms of capacity for self-renewal, multi-lineage differentiation, and expression of the canonical BC marker NGFR (Figures S2A-E). We sorted day 40-42 iPSC-derived GFP+/TOM+ cells and placed them in ALI 2D cultures for at least 2 weeks and observed differentiation into cells expressing markers of MCCs and SCs, although this differentiation appeared to be patchy (Figure S2A) and cells failed to maintain barrier function based on transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements (Figures S2A-B) in contrast to ALI-differentiated primary HBEC controls (Figures S2A-B). In keeping with these results, NGFR was expressed on only a small fraction, 1.9±1.8%, of GFP+/TOM+ cells on day 40-42 of differentiation, suggesting cells at this time point were unlikely to be mature BCs. Even after 3 additional months of serial sphere passaging of GFP+/TOM+ cells in 3D culture, NGFR expression did not significantly increase, although GFP and TOM co-expression was maintained in the majority of cells (Figures S2C-E) suggesting that increased culture time alone would not induce BC maturation of iPSC-derived NKX2-1+/TP63+ cells.

We reasoned that one possible explanation for the low expression of NGFR and inconsistent multi-lineage differentiation of iPSC-derived cells was that GFP+/TOM+ cells were more similar to immature TP63+/NKX2-1+/KRT5− airway progenitors observed in vivo during early airway patterning and were not yet mature BCs (Y. Yang et al. 2018). Thus, we next sought to identify culture conditions that would further differentiate GFP+/TOM+ cells into a more basal-like state, using NGFR expression as a readout. Recently, inhibition of SMAD and ROCK signaling was found to induce a proliferative state in primary BCs and significantly increase overall yield from serially passaged cultures while maintaining, to an extent, their differentiation capacity (Mou et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018). We tested whether GFP+/TOM+ iPSC-derived airway progenitors would selectively proliferate and possibly mature in media optimized for primary human BC culture. On day 30-32 of differentiation GFP+/TOM+ cells were sorted, replated in 3D Matrigel, and exposed to a commercially available BC medium (PneumaCult-Ex Plus) supplemented with small molecules inhibitors of SMAD signaling (TGFβ and BMP inhibition with A 83-01 and DMH1, respectively) and Y-27632 (hereafter “BC medium”) (Figures 2A-D). In response to BC medium, GFP+/TOM+ spheroids exhibited less distinct lumens (Figure 2A) with rapid and robust induction of NGFR in GFP+/TOM+ cells within 4 days of exposure to BC medium (Figures 2B-D and S2F-G). For example, between days 1 and 3, NGFR expression increased in frequency from ~1% to 35% in response to BC medium. By day 6, 71±5% (mean±SD) of cells expressed NGFR (Figure 2B), suggesting that the change in medium formulation, rather than selective expansion of rare NGFR+ cells, was inducing NGFR expression in previously NGFR− cells. In contrast, parallel aliquots of cells that continued in FGF2+10+DCI+Y (Figure 2B, D, and S2F) expressed little to no NGFR.

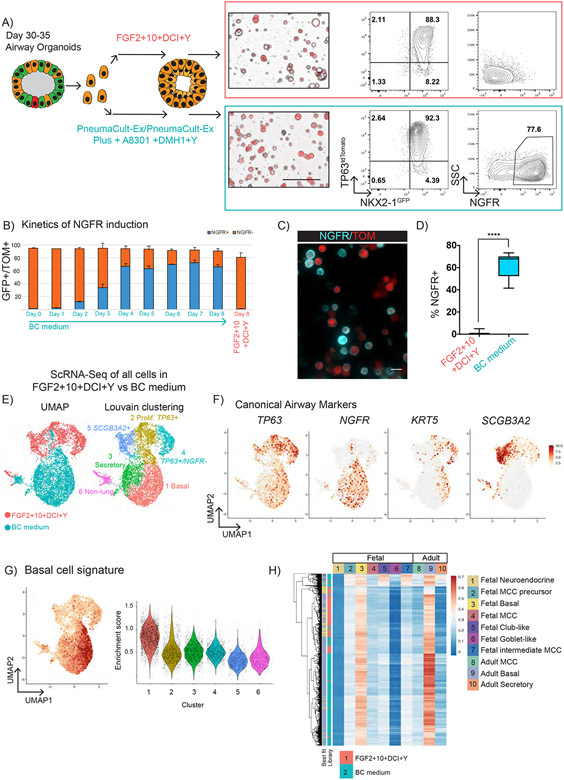

Figure 2: NKX2-1GFP+/TP63tdTomato+ cells adopt a molecular signature similar to primary basal cells.

(A) Schematic of experiment: GFP+/TOM+ sorted cells were suspended in 3D Matrigel between days 30-35 of differentiation in FGF2+FGF10+DCI+Y or primary BC media. After 12-14 days morphology and tdTomato fluorescence were assessed (left panel) and the expression of NKX2-1GFP, TP63tdTomato and NGFR quantified by flow cytometry (middle and right panel, representative plots). See supplemental Figure 2 for additional details.

(B) Kinetics of NGFR induction, quantified by flow cytometry in response to primary BC medium compared to continued FGF2+FGF10+DCI+Y over 8 days between day 33-41 (n=3).

(C) NGFR protein immunostaining (cyan) of BU3 NGPT cells in primary BC medium compared to TP63tdTomato fluorescence (scale bar=20μm).

(D) Percentage of NGFR+ cells quantified by flow cytometry between day 40-50 (n=12).

(E) ScRNA-Seq of day 46 cells from BC or FGF2+FGF10+DCI+Y media. UMAP (left panel) displays the distribution based on culture conditions used to treat cells. Louvain clustering (res = 0.25) identifies 6 clusters (1-6).

(F) UMAP of canonical BC (TP63, NGFR, KRT5) and SC (SCGB3A2) markers.

(G) UMAP of the expression of BC signature (left) and graph of BC gene signature enrichment score (“Basal”=0.84±0.24, “Proliferative TP63+”=0.52±0.24, “Secretory”= 0.51±0.18 “TP63+/NGFR−”=0.51±0.15, and “SCGB3A2+”=0.32±0.15, mean enrichment score±SD). See also Figures S3, S4.

(H) Heatmap showing all calculated pairwise Pearson’s correlation coefficients between freshly isolated primary human airway cells (without culturing) and all iPSC-derived cells on day 46 grown in either FGF2+FGF10+DCI+Y or BC medium. Ten fetal and adult primary airway epithelial cell types are shown. Colors of the best fit annotation represent the epithelial cell type with the highest PCCs for each iBC in each cultured sample.

Next, to determine whether the increase in NGFR expression in response to BC medium was coincident with a broader augmentation of a mature BC program, we performed single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-Seq). We differentiated BU3 NGPT iPSCs in our new protocol (Figure 2A), purifying GFP+/TOM+ cells on day 30-32 followed by replating for 3D culture in either BC medium vs continuing in FGF2+10+DCI+Y medium until scRNA-Seq analysis on day 46. After quality control, a total of 7331 cells were analyzed (Louvain clustering; Figure 2E), and six populations were identified based on the expression of canonical markers, cell-cycle, and differentially expressed genes (DEG): (1-6, in descending order of size); 1: “Basal”, 2: “Proliferative TP63+”, 3: “Secretory”, 4: “TP63+/NGFR−”, 5: “SCGB3A2+’’, 6: “Non-lung endoderm” (Figure 2E-F, S3A-C). Clusters 1, 2 and 4, with basal-like features, expressed key BC markers as well as TP63 and tdTomato, thus supporting the reporter specificity (Figure S3A-C). As expected, NGFR was only expressed in the basal-like population cultured in BC medium (cluster 1; Figure 2F). Notably, we have previously demonstrated that during lung directed differentiation cells can revert to non-lung endodermal lineages (Hurley et al., 2020; McCauley et al., 2018), however less than 0.05% of all cells were characterized as non-lung endoderm in this analysis (Figure S3B).

We next sought to quantify the transcriptomic similarities and differences of these iPSC-derived clusters compared to their human airway counterparts. We included freshly isolated adult and fetal airway epithelia to determine the transcriptomic profile of endogenous airway epithelial cells and also cultured human airway epithelium, the gold-standard in vitro platform of airway biology. First, we generated gene-signatures composed of the top 30 DEGs in BCs, SCs and MCCs from scRNA-Seq of cultured HBECs (“P0”; minimal culture) before and after ALI differentiation (Fulcher and Randell, 2013) (Table S1, Figure S4A-D). The validity of these signatures was confirmed by quantifying their expression in freshly isolated human airway epithelium from 6 adult individuals (Carraro et al., 2020b)(Figure S3D). The expression of each signature was then visualized on the UMAP projection of cells from BC medium and FGF2+10+DCI+Y and the enrichment score for BCs, SCs and MCCs measured in each of clusters 1-6. Cluster 1 (BC medium) had the highest BC enrichment score for the BC signature and expressed canonical BC markers including S100A2, CAV1 and COL17A1 in addition to TP63, KRT5, KRT17, and ITGB4 (Figure 2G, S3C) (Rock et al. 2009; Plasschaert et al. 2018).

In order to compare our iPSC-derived cells with adult and fetal lung cell types and exclude the potential confounding effects of in vitro culture on gene expression, we first integrated the dataset of freshly isolated adult airway epithelial cells with that of fetal airways at different developmental time-points (Carraro et al., 2020b; Miller et al., 2020). After identifying differentially expressed genes between adult airway cells and their iPSC-derived counterparts (Table S2), we selected primary cell comparators consisting of 7 fetal and 3 adult airway cell-types and identified 366 unique markers to quantify the transcriptomic similarities between iPSC-derived cells from FGF2+10+DCI+Y or BC medium and each of these primary cell-types using Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients (PCC) (Figure 2H) (Miller et al. 2020). For each iPSC-derived single cell, the primary epithelial cell-type exhibiting the maximum PCC was determined and indicated as “best fit”. Cells from FGF2+10+DCI+Y were best fit with either “Fetal Basal” or “Adult Basal”. On the other hand, the majority of cells in BC medium were most transcriptionally similar to “Adult Basal” cells. Consistent with this assignment, NGFR expression was infrequent in fetal BCs (1.4%) compared to adult BCs (40%) suggesting it marks more mature BCs. Furthermore, primary HBECs analyzed in the same manner also showed a best fit to “Adult Basal” cells, verifying the approach (Figure S3E). In view of their more basal-like transcriptional profile we designated GFP+/TOM+ cells in BC medium as iPSC-derived BCs (“iBCs”).

Next, to interrogate possible biological differences between iPSC-derived cells in BC medium and both fetal and adult primary BCs, we used Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (Figure S3F). Based on the observation that KRAS signaling, known to be downstream of FGF, was identified in both comparisons and data suggesting a role for FGF10 signaling in primary BC development in the airways (Ornitz and Itoh, 2015; Volckaert et al., 2013), we modulated FGF signaling between days 15 and 35 of iPSC differentiation and assessed changes in the yield of GFP+/TOM+ cells per input cell. GFP+/TOM+ cells were rare in the absence of FGFs, however, increased in a FGF dose-dependent manner (Figure S3G), suggesting that FGF plays a role in the differentiation of immature lung progenitors into NKX2-1+/TP63+ cells, findings in keeping with our GSEA results.

iBCs Exhibit Stem Cell Properties: Long-term Self-Renewal and Multi-lineage Differentiation.

We next asked to what extent iBCs share the key stem cell properties of primary BCs: long-term self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation (Figure 3A-G). In BC medium, iBCs were propagated for up to 10 passages (170 days) in 3D culture, while retaining GFP/TOM expression (Figure 3B, S5A), NGFR expression, and a normal karyotype (Figure S5B). One input iBC plated on day 45 yielded 6.9±1.7 x 106 cells (mean±SD) 78 days later with a doubling time of 1.1 days (Figure 3B). First, to assess the differentiation and self-renewal of individual cells we adapted the 3D tracheosphere assay previously published for primary BCs (Rock et al. 2009). We established a seeding density at which >95% of spheres were clonally derived from a single iBC (Figure S5C). At this clonal density, NGFR+ sorted iBCs were replated in either BC maintenance or differentiation “ALI” media. In both conditions spheres formed and were composed of a stratified-appearing layer of predominantly NKX2-1+ cells (Figure 3C). In BC medium, NKX2-1+/TP63+ cells were readily identified in the outermost cell layer of all spheres. In the differentiation medium, BCs, MCCs and SCs were identified in all spheres suggesting self-renewal and clonal multi-lineage differentiation of iBCs (Figure 3C, Figure S5D). In extended 3D culture in BC medium without passaging, some spontaneous differentiation of iBCs into secretory and MCCs was observed (Figure S5E). Next, to further study differentiation, we generated 2D ALI cultures from iBCs. On day 46, NGFR+ iBCs were sorted and plated on Transwell inserts in differentiation “ALI” medium and compared to presorted cells (Schematic Figure 3A). Without NGFR sorting, we observed patchy differentiation in Transwell cultures, evident as frequent areas devoid of staining for the above lung markers and some areas devoid of TOM expression (Figure 3D). In contrast, NGFR+ sorted iBCs initially formed a confluent TOM+ epithelial layer in submerged culture and after 16 days in air-phase culture, SCs (SCGB1A1+, MUC5AC+) and beating MCCs were distributed homogeneously across the entire Transwell (Figure 3E and Video S1). Confocal microscopy and transverse sections confirmed that NGFR+ sorted cells had formed pseudostratified epithelia composed of MCCs (ACT+, FOXJ1+) and SCs (SCGB1A1+, MUC5AC+) (Figure 3E-G). Importantly, after ALI differentiation, iBCs had also formed TP63+/KRT5+/NGFR+ cells with the expected “basal” location of bona-fide BCs, along the basal membrane (Figure 3G). When iBCs and primary HBECs were differentiated in identical ALI conditions, trilineage differentiation from both starting cell types was easily detected by immunostaining (TP63+ cells: 13.3±2.7% vs 27.9±6.1%, FOXJ1+ cells: 42.4±3.3% vs 19.6±2%, MUC5AC+ cells: 9.4±1.7% vs 16.3±4.5%, and SCGB1A1+ cells: 8.2±0.4% vs 18.8±2.1% [mean cell frequency±SD; iBC vs primary HBEC]). Both NGFR sorted and GFP+/TOM+ iBCs formed epithelial layers with similar TEER to primary controls and significantly higher TEER than ALI differentiations prepared in parallel from GFP+/TOM+ cells that had been maintained in FGF2+10+DCI+Y without BC medium maturation (Figure 3H). Next, we tested the extent to which the multi-lineage differentiation capacity of iBCs was maintained after extended in vitro expansion in BC medium. After 10 passages of expansion, iBCs retained their capacity to form trilineage, pseudostratified airway epithelium when transferred to ALI culture (Figures S5F). After cryopreservation and subsequent thaw, iBCs retained their expression of BC markers, proliferated in BC medium, and retained TEER and trilineage differentiation potential in ALI conditions (Figure 3I, S6A-E). Taken together these results indicated successful derivation from iPSCs of iBCs which exhibit the airway stem cell properties of self-renewal and multipotent differentiation.

Figure 3: iBCs undergo self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation.

(A) Schematic of experiment: GFP+/TOM+ cells sorted on approximately day 40 of differentiation expanded in BC medium and then characterized in terms of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation in ALI.

(B) Representative flow cytometry plots of NKX2-1GFP vs TP63tdTomato expression in cells at passage 7, following expansion in 3D culture with BC medium (left panel). Per input sorted GFP+/Tom+ cell on day 45 we calculated the yield up to 123 days of directed differentiation (right panel).

(C) Immunolabeling of representative spheroid on day 83 of differentiation in either BC medium (left and middle panel) or after 10 days in ALI differentiation medium (right panel) with antibodies indicated (DNA stained with Hoechst; scale bar=50μm). See also Figure S5D.

(D-E) GFP+/TOM+ cells were expanded in BC medium until day 46 and plated on Transwells with (E) or without (D) GFP/TOM/NGFR sorting. Representative images of the endogenous TP63tdTomato fluorescence during culture of BU3 NGPT-derived ALI. Stitched image of whole Transwell insert (Ø =6.5mm) (1st column) and zoom-in (2nd column). Immunolabeling with antibodies indicated after 16 days of ALI culture. (3rd and 4th columns) (DNA stained with DRAQ5; scale bar =100μm).

(F) Confocal microscopy of BU3 NGPT-derived ALI cultures shown in E and immunolabeled with antibodies indicated (DNA stained with DRAQ5; scale bar =100μm).

(G) Transverse section of BU3 NGPT-derived ALI cultures shown in E and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or antibodies indicated (DNA stained with DAPI; scale bar=100μm).

(H) TEER measurements of Transwell ALI cultures, comparing GFP+/TOM+ from FGF2+10+DCI+Y (n=5), BC medium with (N=4) or without (n=5) NGFR sorting and primary HBEC controls (n=21).

(I) TP63tdTomato fluorescence in BU3 NGPT iBCs after cryopreservation and thaw (scale bar=200μm) (left panel). Immunolabeling of ALI cultures generated from cryopreserved iBCs with antibodies indicated (scale bar=100μm).

Single-cell RNA Sequencing of iBC-derived Airway Epithelium

To more completely assess the molecular phenotypes of the differentiated cell types generated from iBCs, we performed scRNA-sequencing of ALI cultures from NGFR sorted cells (Figure 4A). Louvain clustering identified five clusters (1-5) with gene expression profiles reminiscent of airway epithelial cell types and one proliferative cluster (6) (Figure 4A-E, S7A-B). We found no discrete cluster of non-lung endoderm cells (low to undetectable CDX2, AFP, ALB). We compared the top 20 DEGs in each cluster to the scRNAseq dataset of differential gene expression in primary airway epithelial cell types (Figure 4B, S4 and Table S1) and published datasets (Plasschaert et al. 2018) and annotated the cell types as follows: “Secretory” (cluster 2, DEGs: SCGB1A1, SCGB3A2, MUC5B, C3, XBP1, CEACAM6, CXCL1), “Basal” (cluster 6, DEGs: KRT5, KRT17, S100A2), “Intermediate” (cluster 1, DEGs: KRT4, KRT12,KRT13, and KRT15), “Immature MCC” (cluster 3, DEGs: CCNO, CDC20b, NEK2) and “MCC” (cluster 4, DEGs: TUBB4B, TUB1A1, TPP3 and CAPS) (Figures 4A-E, S7A-B). Enrichment scores for gene-signatures of primary BCs, SCs and MCCs correlated with these annotated clusters with enrichment scores of 0.77±0.16, 0.54±0.26 and 1.54±0.27 (mean enrichment score±SD), respectively (Figures 4D, S7A). FOXJ1, a key transcription factor expressed in MCCs, was found enriched in both ciliated cell clusters (Figure 4C); however, FOXN4, recently identified as a marker of immature primary human airway MCCs, was found only in the immature iPSC-derived MCCs (Figure S7A) (Plasschaert et al. 2018). There was no evidence to suggest the presence of ionocytes, neuroendocrine or alveolar epithelial cells amongst the 3,500 iPSC-derived cells analyzed (data not shown). To quantify the transcriptomic similarities of iPSC-derived SCs and MCCs to fetal and adult MCCs and SCs we used PCC and the 10 fetal and adult airway cell types as shown in 2H (Figure S7C). Similar to HBEC derived ALI (Figure S3E) we detected cells with gene-expression patterns consistent with BCs, SCs and MCCs. iPSC-derived MCCs were transcriptionally distinct and best fit with “Fetal MCC” or “Fetal MCC precursor” cell types. The remaining cells were predominantly best fit with “Fetal Basal” or “Fetal Club-like” cell types. The expression levels of key airway epithelial markers in iBC-derived ALI cultures was confirmed using qRT-PCR and directly compared to primary controls cultured in identical conditions (Figure 4F). In both primary and iPSC derived samples there was robust upregulation of FOXJ1, MUC5AC and SCGB1A1. FOXJ1 expression was significantly higher and MUC5AC expression lower in iPSC-derived ALI cultures (Figure 4F). SCGB3A2 was expressed in iPSC-derived ALI cultures but not detected at significant levels in primary HBEC-derived ALI cultures, whereas SCGB1A1 expression was similar between both samples (Figure 4F). We note that iBCs yielded pseudostratified airway epithelium composed of BCs, MCCs, and SCs, irrespective of whether PneumaCult-ALI or UNC-ALI media were utilized in ALI cultures (Figure S7D-E).

Figure 4: scRNA-Seq profiling of iBCs and their differentiated progeny.

(A) Schematic of scRNA-Seq experiment and UMAP with Louvain clustering (clusters 1-6) of iBC-derived ALI. See also Figures S4 and S7.

(B) Top 20 differentially expressed genes (DEG) per cluster.

(C) UMAPs of primary BC, SC and MCC gene-signatures applied to iBC-derived ALI (upper row). Violin plots of the enrichment score of clusters 1-6 for BC, SC and MCC gene signatures (lower panel).

(D) UMAPs of the canonical BC, SC, and MCC markers across clusters 1-6.

(E) Violin gene-expression plots of same panel of markers shown in (D).

(F) qRT-PCR validation of key airway markers in iBC-derived ALI (iBC-ALI) compared to primary HBEC-derived ALI (HBEC-ALI) in PneumaCult ALI medium. Fold change is 2−ΔΔCt normalized to undifferentiated iPSCs. (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01)

iBCs form a Differentiated Airway Epithelium in a Tracheal Xenograft

Engraftment and regeneration in vivo after transplantation is a critical measure of stem cell function that has been successfully tested for several non-lung tissues, such as the hematopoietic system, but remains a major challenge for lung epithelia, with only limited success reported to date in the airways (Ghosh et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2018; Nichane et al., 2017). We sought to determine if iBCs could establish an airway epithelium in vivo using the tracheal xenograft model (Everitt et al., 1989). Rat tracheas were completely decellularized by repeated freeze thaws, seeded with NGPT-derived iBCs, implanted subcutaneously into the flanks of Foxn1nu immune-compromised mice and then followed for three weeks after transplantation (Figure 5A). Air exposure through the trachea was maintained in vivo using open-ended tubing. After three weeks, a stratified or pseudostratified epithelial layer of cells had formed (Figure 5B). Using antibodies against canonical markers we identified BCs (KRT5+) occupying the expected positions along the basement membrane and SCs (SCGB1A1+, MUC5AC+, MUC5B+) and MCCs (ACT+) oriented towards the air-filled tracheal lumen (Figure 5C). NKX2-1GFP and TP63tdTomato expression were detected throughout the sections of epithelium analyzed confirming its origin from transplanted rather than endogenous cells (Figure 5C). In summary, in the tracheal xenograft model iBCs form an airway epithelium similar in structure and composition to in vivo airways.

Figure 5: iBCs establish pseudostratified, well-differentiated airway epithelium in vivo in tracheal xenografts.

(A) Schematic of experimental procedure used to generate tracheal xenografts.

(B) Magnified image (left panel, scale bar = 50μm) of xenograft epithelium established from BU3 NGPT iBCs stained with hematoxylin and eosin; the location of this region within the transverse section of the xenograft is shown in the right panel. White arrows indicate examples of MCCs.

(C) Immunolabeling of the xenograft epithelium with the indicated antibodies. Anti-GFP and anti-RFP antibodies were used to detect the expression of each fluorochrome reporter that had been targeted to the donor human cell loci, NKX2-1GFP and TP63tdTomato respectively. DAPI staining indicates DNA (scale bar = 50μm).

Selection of iBCs from Non-reporter iPSCs Lines using Antibodies Directed Against Surface Markers.

To expand the application of iBCs for disease modeling we first sought to adapt our approach so that a diversity of normal or patient-specific iPSC lines could be differentiated into iBCs without requiring the use of knock-in fluorochrome reporters. We found through repeating our protocol with the BU3 NGPT line, we could replace GFP+/TOM+ sorting with antibody-based sorting of NGFR+ cells to prospectively isolate putative iBCs (Figure 6). For example, cells grown until days 40-42 with our protocol (Figure 6A-C), were 73.7±5.9% (mean±SD) GFP/TOM double positive, and gating on NGFR+/EpCAM+ cells yielded a population of cells highly enriched in GFP/TOM co-expressing cells (94.3±1.1%, mean±SD) (Figure 6B). A representative experiment is shown in Figure 6B: 73.6% of cells were GFP+/TOM+, 55.3% NGFR+/EPCAM+, and 94.5% of sorted NGFR+/EPCAM+ cells were GFP+/TOM+. Sorting solely on NGFR+ or NGFR+/EpCAM+ and replating cells in ALI cultures resulted in successful derivation of a TOM+ pseudostratified airway epithelium, similar to sorting GFP+/TOM+/NGFR+ cells and in contrast to unsorted controls (Figure 6C). Four additional iPSC lines (DD001m, PCD1, 1566, 1567) and an ESC line (RUES2) were also differentiated, recapitulating our BC differentiation protocol while completely replacing the need for fluorescent reporters through the use of CD47hi/CD26neg sorting on day 15 to purify NKX2-1+ progenitors as we have published (Hawkins et al. 2017), followed by NGFR+ sorting after day 40 to purify candidate iBCs (see methods and schematic Figure 6A). NGFR+ cells from all five iPSC/ESC lines differentiated into pseudostratified epithelia composed of MCCs, SCs and BCs (Figure 6D-G).

Figure 6: A surface marker strategy for purifying iBCs using NGFR replaces the need for fluorescent reporters.

(A) Schematic of NKX2-1GFP/TP63tdTomato reporter vs surface marker iBC protocols.

(B) Representative flow cytometry plots of BU3 NGPT iBCs on day 40 of differentiation and labeled with antibodies against NGFR and EpCAM. Red arrow indicates sorted NGFR+/EpCAM+ cells are 94.5% GFP+/TOM+. Enrichment is quantified in the right panel (n=3).

(C) Representative images of the endogenous TP63tdTomato fluorescence in whole Transwell filters (Ø =6.5mm) seeded with sorted (NGFR+/EpCAM+) or unsorted cells during submerged culture and after ALI culture.

(D) Representative flow cytometry plot of a non-reporter iPSC line (DD001m) stained for NGFR is shown.

(E) Representative image of sorted NGFR+ cells plated on Transwell filters and after 7 days immunolabeled with an anti-TP63 antibody (DNA stained with Hoechst; scale bar=100μm).

(F) Confocal microscopy of DD001m iPSC-derived ALI cultures immunolabeled with antibodies indicated (scale bar=200μm).

(G) Representative image of RUES2 ESC-derived ALI immunolabeled with an anti-ACT antibody (DNA stained with DRAQ5; scale bar=200μm) (upper left) and confocal microscopy of it immunolabeled with antibodies indicated (DNA stained with DRAQ5; scale bar=100μm).

iBCs Model Biological Features of the Airway Diseases: Asthma, CF and PCD

Human airway epithelium has diverse biologic and physiologic roles, some of which are uniquely affected by disease. We tested whether iBC-derived ALI cultures could recapitulate features of the three airway disorders with distinct epithelial characteristics: (1) mucus cell metaplasia in asthma; (2) abnormal ion-flux seen in cystic fibrosis (CF); and (3) defective ciliary beating seen in primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). First, we tested whether iBC-derived ALI cultures could recapitulate the mucus cell metaplasia seen in asthma. IL-13 is an inflammatory cytokine in asthma and can induce mucus metaplasia. A number of studies, in mice and primary human airway epithelial cell cultures, have found IL-13 leads to increased MUC5AC+ cell numbers, via the activation of STAT6 and SPDEF, at the expense of MCCs and MUC5B+ cell frequencies (Kondo et al., 2002; Seibold, 2018; Woodruff et al., 2009). In response to IL-13 added on day 10 of ALI differentiation of iBCs, we found a significant 1.75 fold increase in numbers of MUC5AC+ cells (p=0.002), increased expression of the goblet cell transcriptional regulator SPDEF, and a decrease in MUC5B expression (Figures 7A-C). Next, we applied our antibody-based iBC purification protocol for modeling the genetic airway diseases CF and PCD (Figure 7D). We identified a CF patient homozygous for the most common CFTR mutation (c.1521_1523delCTT, p.Phe508del) and a PCD patient homozygous for one of the most common mutations in DNAH5 (c.12617G>A, p.Trp4206Ter), and generated iPSCs from these individuals (see methods and Figure S1). For CF modeling we first used gene-editing to correct the F508del CFTR mutation and then differentiated pre- and post-gene corrected paired syngeneic iPSC clones (hereafter CF and Corr CF) in our protocol using our antibody-only based sorting methods generated ALI cultures composed of BCs, SCs and MCCs (Figure 6A, S7F). CFTR-dependent current, representing ion-flux regulated by apically-localized CFTR, was measured using the gold-standard Ussing chamber approach. As expected, Ussing chamber analysis indicated minimal CFTR-dependent current in CF ALI cultures (Forskolin ΔIsc=0.8μA/cm2, CFTRInh-172 ΔIsc=−0.8μA/cm2). In marked contrast, correction of the F508del mutation led to restoration of CFTR-dependent current (Forskolin ΔIsc=35.1±1.8μA/cm2, CFTRInh-172 ΔIsc=−43.2±2.5μA/cm2, Figure 7E-F). Similar results were obtained from 2 additional CF iPSC lines following CFTR gene correction (data not shown). A limitation of primary HBECs in CF studies is the decrease in CFTR-dependent current with extended passage of primary HBECs (Gentzsch et al., 2016). To address this possibility in iPSC-derived airway epithelium, we performed Ussing chamber analysis on ALI cultures generated from the NGPT line before and after cryopreservation of iBCs and after in vitro expansion of iBCs up to day 87 and found CFTR-dependent current was retained (Figure S6F).

Figure 7: iBCs enable in vitro modeling of asthma, cystic fibrosis, and primary ciliary dyskinesia.

(A) Representative images of BU3 NGPT iBC-derived ALI cultures, with or without IL-13 treatment, immunolabeled with antibodies indicated (DNA stained with Hoechst; scale bar=200μm).

(B) Quantification of the number of MUC5AC+ cells per high power field for IL13 treated vs untreated wells (n=3).

(C) qRT-PCR quantification of mRNA expression levels of MUC5AC, SPDEF and MUC5B in IL-13 treated (+IL-13) vs untreated cells (No IL-13) (n=3). Data are preselected as fold change over untreated iBC-derived ALI cultures (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001).

(D) Schematic of CF and PCD disease modeling experiments, relying on surface markers. See also Figures S7F-G.

(E) Representative electrophysiological traces from Ussing chamber analysis of ALI cultures generated from CF iPSCs and corrected CF iPSCs (Corr CF).

(F) Mean and SD of electrophysiological values from E (n=3).

(G) Immunolabeling of MCCs in ALI cultures generated from DNAH5 mutant nasal epithelial cells, iPSCs, non-diseased primary HBECs and BU3 NGPT iPSCs with antibodies indicated (DNA stained with DAPI; scale bar=10μm). Transmission electron microscopy of cilia (right column).

H-I) The number of outer dynein arms detected in cross sections of cilia (H) or ciliary beat frequency (I) from the samples detailed in G. (***=p<0.001).

To develop a model for PCD, we differentiated our PCD iPSC line carrying the DNAH5 mutation and generated ALI cultures containing MCCs. We compared these cells to control ALI cultures from BU3 NGPT iBCs, primary nasal epithelium from the PCD donor, and normal primary HBECs. Cilia motility was not detected in the MCCs generated from either the DNAH5 mutant iPSC line or from DNAH5 mutant primary cells, in contrast to normal controls (Video S2). The possibility that DNAH5 mutant iPSCs had failed to produce cilia was excluded by immunofluorescent staining with antibodies against ACT, which confirmed the widespread presence of normal appearing cilia in all samples (Figure 7G,S7F-G). In addition, increased tethering of MUC5AC+ mucus strands was observed on the apical surface of the differentiated epithelium generated from the mutant iPSCs (Figure S7F).

In MCCs generated from normal iPSCs and normal HBECs, DNAH5 protein was present and colocalized with ACT along the length of cilia while DNAH5 protein was not detected in either PCD iPSC-derived or primary nasal-derived MCCs cells (Figure 7G). In contrast DNALI1, an inner dynein arm (IDA) protein, was detectable by immunostaining, suggesting an intact IDA complex (Figure S7G). Transmission electron microscopy of DNAH5 mutant iPSC-derived MCCs cells showed lack of the ODA, identical to the defect in cilia of nasal cells obtained from the patient, and in contrast to MCCs obtained from control iPSC and normal HBEC (Figure 7G-H). Ciliary beat frequency (CBF) was not detected in DNAH5 mutant MCCs from the patient or from mutant iPSCs, whereas CBF was similar between normal HBECs and BU3 NGPT-derived MCCs (Figure 7I). Taken together these results indicate that iPSC-derived airway epithelium shares key physiologic and biologic features with human airway epithelium. In addition, patient-specific iBCs purified without using fluorescent protein reporters can be successfully applied to model a variety of airway epithelial diseases, including CF and PCD.

Discussion

Here we report the differentiation of iPSCs into iBCs, cells that are molecularly and functionally similar to the predominant stem cell of human airways, the basal cell. We demonstrate the potential of these iBCs to model human development and disease and provide evidence of their capacity to regenerate airway epithelium in vivo in a tracheal xenograft model.

The derivation of a tissue-resident stem cell from human iPSCs has considerable implications for regenerative medicine research as it overcomes several important hurdles currently limiting progress in this field. For example, despite significant progress in recent years, directed differentiation protocols are often lengthy, complex, and yield immature and heterogeneous cells (Dye et al., 2015; Firth et al., 2014; Gotoh et al., 2014; Hawkins et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2014; Jacob et al., 2017; McCauley et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2018). Frequently these issues are due to lack of precise knowledge regarding developmental roadmaps associated with cellular embryonic origin. TP63+ populations have previously been observed stochastically in iPSC directed differentiation protocols and their characterization was based only on the expression of a handful of canonical markers limiting any conclusions as to whether basal-like cells had been produced (Hawkins et al. 2017; McCauley et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017; Konishi et al. 2016; Dye et al. 2015). Without the ability to purify these cells from the heterogeneous mix of other iPSC-derived lineages, little progress has been made in phenotyping or testing their functional potential. Here we report several advances that culminate in the efficient derivation and purification of BCs from iPSCs. Using a dual fluorescence BC reporter iPSC line, we recapitulated in vitro the milestones of in vivo airway development and BC specification (Y. Yang et al. 2018). First, during the emergence of the earliest detectable lung epithelial program, rare TP63+ cells were detected. Next, in response to the withdrawal of Wnt signaling and in the presence of FGF2 and FGF10, an immature airway program with upregulation of TP63 and SCGB3A2 was evident. In response to primary BC medium and inhibition of SMAD signaling, these TP63+ cells adopted molecular and functional phenotypes similar to adult BCs, including the capacity for extensive self-renewal for over 150 days in culture and multi-lineage airway epithelial differentiation both in vitro and in vivo. We conclude that the resulting cells fulfill the criteria to be termed iPSC-derived BCs or iBCs.

From a practical perspective, insight and methodologies developed herein should expand the application of iPSC technology. The shared properties of primary BCs and iBCs for expansion and differentiation in ALI culture makes them attractive for a variety of in vitro or in vivo applications. Specifically, the ability to purify iBCs based on the surface marker NGFR, expand the resulting cells in 3D culture, and cryopreserve cells should minimize variability associated with directed differentiation and can potentially offset the cost and time required for these protocols.

In terms of the utility of this platform for disease modeling, we selected diseases with unique research challenges. In asthma, the epithelium plays a sentinel role in pathogenesis and there is significant interest in understanding epithelial dysfunction and the contribution of genetic variants to asthma susceptibility (Loxham et al., 2014). Here we demonstrate that a mucus metaplasia phenotype is induced in iPSC-derived airway epithelium in response to stimulation with the Th-2 cytokine IL-13. In CF, where many mutations in one gene necessitate individual models of disease for predicting personalized therapeutics, we demonstrated that patient-specific iPSCs or their gene-edited progeny can be differentiated into iBCs and give rise to airway epithelia exhibiting quantifiable CFTR-dependent currents of sufficient magnitude for disease modeling using the gold-standard Ussing chamber assay of CFTR function. While we did not detect airway ionocytes in our scRNA-Seq profiles of iPSC-derived cells, given the known rarity of this cell type in vivo or in cultured HBEC preparations, further work is required to determine if ionocytes, which are known to be rich in CFTR (Plasschaert et al., 2018), occur at low frequencies in our cultures or contribute in any way to the currents we measured. For PCD, where many mutations in many genes controlling ciliogenesis can contribute to the disease, we determined that iBC-derived MCCs model both the functional and ultrastructural defects observed in DNAH5 mutant primary donor derived cells. These proof-of-concept experiments suggest that the iPSC platform may be helpful in determining mechanisms of pathogenicity for genetic airway diseases and may serve as a platform to develop novel therapeutics.

Limitations of the Study

While we conclude that iBCs share essential features with their endogenous counterparts, several questions remain including the maturity status, regionality, genetic stability, and in vivo competence of iBCs. Typically, iPSC-derived specialized cell types are at fetal stages of development (Studer et al., 2015). While the transcriptomes of iBCs were most similar to adult BCs in our analysis, their differentiated progeny (SCs and MCCs) were more similar to fetal equivalent cell-types than to freshly isolated adult cells. This may indicate differences in maturity, reflect the limited duration of in vitro differentiation from the BC state, or regional differences not represented in sc-RNA-Seq adult airway samples.

We note differences in the pattern of expression of two secretoglobins, SCGB3A1 and SCGB3A2, in iPSC-derived cells compared to primary cells. SCGB3A1, predominantly expressed in the larger airway, is the most highly expressed gene in primary BC-derived SCs while SCGB3A2 is expressed at very low levels. iBC-derived SCs express high SCGB3A2 and low/absent SCGB3A1. These differences further raise the question of immaturity and/or proximal/distal patterning (Reynolds et al., 2002) of iBCs.

Finally, we provide evidence of the potential of iBCs to regenerate an airway epithelium in vivo in a tracheal xenograft. This approach does not recapitulate the ultimate clinical goal of orthotopic transplantation of cells for in vivo airway reconstitution. Limited progress has been made to date in engrafting cells in the airways (Ghosh et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2018; Nichane et al., 2017). As this field advances, determining the extent to which transplanted iBCs might engraft and integrate with endogenous airway epithelium will be required as a first step towards future therapies whereby autologous gene-edited iBCs may eventually be employed therapeutically for in vivo reconstitution of airway epithelial function for individuals with genetic airway disease (Berical et al., 2019). That said, efficient derivation of an identifiable, tissue-specific stem cell, capable of long-term self-renewal, cryopreservation capacity, and retained multilineage differentiation overcomes many of the hurdles that face iPSC technology for studies of respiratory mucosa and diseases of pulmonary epithelium.

Star Methods:

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to, and will be fulfilled by, the Lead Contact, Darrell Kotton (dkotton@bu.edu).

Materials Availability

Induced pluripotent stem cell lines generated in this study are available from the CReM Biobank at Boston University and Boston Medical Center and can be found at http://www.bu.edu/dbin/stemcells/. The embryonic stem cell line RUES2 was received from Dr. Ali Brivanlou, Rockefeller University, NY.

Data and Code Availability

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al., 2002) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE142246 as well on the Kotton Lab’s Bioinformatics Portal at http://www.kottonlab.com. The scRNA-Seq data of primary fetal airway (Miller et al., 2020) and primary adult airway (Carraro et al., 2020) were previously deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Human subjects

The Institutional Review Board of Boston University approved the generation and differentiation of human iPSCs with documented informed consent obtained from participants. The generation of CF iPSCs was approved by Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. Human airway tissue and primary HBECs were received from the CF Center Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core (Dr. Scott Randell) at the University of North Carolina. Human lung tissue was procured under the University of North Carolina Office of Research Ethics Biomedical Institutional Review Board Protocol No. 03-1396. For PCD studies, human protocols were approved by the institutional review board at Washington University in St. Louis. Subjects with known mutations causative of PCD were recruited from the PCD and Rare Airway Disease clinic at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and Washington University. Informed consent was obtained from individuals (or their legal guardians). All human samples were de-identified. Details of procurement and isolation of airway epithelial cells from fetal and adult human lungs were previously described (Carraro et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2020).

Human iPSC reprogramming and iPSC/ESC maintenance

All iPSC and ESC lines were maintained in feeder-free conditions on hESC-qualified Matrigel (Corning) in StemFlex Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) or mTeSR1 medium (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) and passaged with Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (Stemcell Technologies) or ReLeSR (Stemcell Technologies). All human ESC/iPSC lines used were characterized for pluripotency and were found to be karyotypically normal. The reprogramming and gene-editing methods to derive BU3 iPSCs and target the NKX2-1 locus to generate BU3 NKX2-1GFP iPSCs were previously described (Hawkins et al., 2017). PCD1 iPSC line (DNAH5 mutation) was generated by reprogramming peripheral blood mononuclear cells with the human EF1a-STEMCCA-loxp lentiviral vector followed by Cre-mediated vector excision, according to our detailed protocol (Sommer et al., 2012). DD001m iPSCs were generated from “DD001m” P0 primary HBECs by modifying a Sendai virus based reprogramming protocol to substitute the base medium for bronchial epithelial growth medium (Park and Mostoslavsky, 2018). Homozygous F508del (p.Phe508del) iPSCs were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells at Boston Children’s Hospital Stem Cell Program by Sendai virus using the Cytotune 2 kit (Thermo Fisher), yielding clones 791 and 792 (“CF”). Clone 792 was selected for correction of the p.Phe508del deletion and the experiments in Figure 7. The RUES2 human embryonic stem cell line was a generous gift from Dr. Ali H. Brivanlou of The Rockefeller University, New York City, NY. Standard immunolabeling for pluripotency markers and G-band karyotyping was performed to ensure pluripotency and normal karyotype in clones selected for these experiments (as shown in Figure S1). For BU3 NGPT iPSCs spontaneous differentiation into mesoderm, endoderm and ectodermal lineages was demonstrated by generating embryoid bodies with iPSC medium in ultra-low attachment plate (Corning) and then replacing with base medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in adherent culture. The cell types from each lineage were identified with standard immunolabeling (as shown in Figure S1) using anti-bodies listed in Key Resources Table. Primocin (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) was routinely added to prevent mycoplasma contamination and all iPSC and ESC lines screened negative for mycoplasma contamination and were routinely tested and remained negative.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-FOXJ1 (2A5) | Invitrogen | Cat.# 14996580 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Acetylated Tubulin (ACT) (6-11B-1) | Millipore-Sigma | Cat.# T7451 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Acetyl-α-Tubulin (Lys40) (D20G3) | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat.# 5335S |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-TP63 (4A4) | Biocare | Cat.# CM163A |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-MUC5AC (E309I) | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat.# 61193 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-MUC5AC (45M1) | Invitrogen | Cat.# MA5-12178 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-MUC5B (A-3) | Santa Cruz | Cat.# Sc-393952 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-KRT5 (D4U8Q) | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat.# 25807 |

| Chicken polyclonal anti-KRT5 (Poly9059) | BioLegend | Cat.# 905901 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NGFR (NGFR5) | Invitrogen | Cat.# MA5-13314 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-p75NTR/NGFR (D4B3) | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat.# 8238 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-CC10 (E-11) | Santa Cruz | Cat.# Sc-365992 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-RFP | Rockland Immunochemicals | Cat.# 600-401-379 |

| Chicken polyclonal anti-GFP | Invitrogen | Cat.# A10262 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-NKX2-1 (EP1584Y) | Abcam | Cat.# ab76013 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ZO-3 (D57G7) | Cell Signaling Technologies | Cat.# 3704S |

| APC-mouse monoclonal anti-CD47 (CC2C6) | Biolegend | Cat.# 323123 |

| PE-mouse monoclonal anti-CD26 (BA5b) | Biolegend | Cat.# 302705 |

| APC/Fire750-mouse monoclonal anti-EpCAM (9C4) | Biolegend | Cat.#324234 |

| APC-mouse monoclonal anti-human CD271/NGFR (ME20.4) | Biolegend | Cat.# 345108 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-EpCAM (AUA1) | Abcam | Cat.#ab20160 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-SOX17 | R&D system | Cat.# AF1924 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NESTIN (Clone 25) | BD | Cat.# 611658 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti- Tubulin β3 (TUJ1) | Biolegend | Cat.# 801201 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-Brachyury | R&D system | Cat.# AF2085 |

| Mouse IgG1kappa isotype control, APC-conjugated | Biolegend | Cat.# 400122 |

| Mouse IgG1 isotype control, PE-conjugated | Biolegend | Cat.# 400113 |

| Mouse IgG1 isotype control, PerCP/Cy5.5-conjugated | Biolegend | Cat.# 400149 |

| Rabbit anti-DNAH5 | Millipore-Sigma | Cat.#HPA037470 |

| Rabbit anti-DNALI1 | Millipore-Sigma | Cat.# HPA028305 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| pHAGE-EF1alphaL-eGFP-W | Addgene | Plasmid# 126686 |

| pHAGE- EF1alphaL-TagBFP-W | Addgene | Plasmid# 126687 |

| pHAGE-CMV-DsRED-W | This paper. | |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Paraffin-embedded section of human trachea | The MLI Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core, University of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| SB431542 | Tocris | Cat.# 1614 |

| Dorsomorphin | Stemgent | Cat.# 04-0024 |

| CHIR99021 | Tocris | Cat.# 4423 |

| Recombinant human BMP4 | R&D Systems | Cat.# 314-BP |

| Retinoic acid | Sigma | Cat.# R2625 |

| Y-27632 dihydrochloride | Tocris | Cat.# 1254 |

| Recombinant human FGF10 | R&D Systems | Cat.# 345-FG-025 |

| Recombinant human FGF2 | R&D Systems | Cat.# 233-FB |

| Dexamethasone | Sigma | Cat.# D4902 |

| 8-bromoadenosine 30,50-cyclic monophosphate sodium salt (cAMP) | Sigma | Cat.# B7880 |

| 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) | Sigma | Cat.# I5879 |

| A83-01 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat.# 293910 |

| DMH1 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat.# 412610 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| RNeasy Mini Kit | Qiagen | Cat. #74104 |

| QIAzol Lysis Reagent | Qiagen | Cat.#79306 |

| TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (2XX), no AmpErase UNG | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat.#4364103 |

| Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3’ Kit v3.1 | 10C Genomics | 1000269 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Sc-RNA-Seq data of iBCs and iBC-derived ALI and primary HBECs and HBEC-ALI | Kotton/Hawkins Labs | GEO: GSE142246 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Human: Normal donor iPSC line targeted with NKX2-1GFP and P63tdTomato (BU3-NGPT) | Kotton Lab (this paper) | www.bumc.bu.edu/stemcells |

| DD001 iPSC | Hawkins Lab (this paper) | |

| Human: Normal donor iPSC line targeted with NKX2-1GFP (BU3-NG) | Kotton Lab (Hawkins et al. 2017) | www.bumc.bu.edu/stemcells |

| Human: Primary ciliary dyskinesia donor iPSC line | Generated in the CReM, BU. | |

| Human: Cystic fibrosis donor iPSC line | Generated at Boston Children’s Hospital. | |

| Human: Corrected cystic fibrosis donor iPSC line | Generated at Boston Children’s Hospital. | |

| Human: RUES2 embryonic stem cell line | Gift from Dr. Ali H. Brivanlou, Rockefeller University | |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Rat: Crl:NIH-Foxn1rnu | Charles river | Strain Code: 118 |

| Mouse: Nu/Nu:Foxn1nu | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX stock #002019 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Primer/Probe Sets (Table S3) | ThermoFisher Scientific | See Table S3 per gene |

| Primers for characterization of the integrated reporter, see Table S4 | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| P63-tdTomato donor | GenScript, This paper | N/A |

| P63gRNA-CAG-Cas9-2A-GFP plasmid | DNA2.0, ATUM This paper | See target sequence in the method |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | National Institutes of Health | https://Imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Prism Software, version 7 | Graphpad Software | Graphpad.com |

| FlowJo software | Becton, Dickinson & Company | Flowjo.com |

| Cell Ranger version 3.0.2 | 10X Genomics | |

| Seurat version 3.1.0 | Satija Lab, NYU | https://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| Other | ||

| mTeSR1 | StemCell Technologies | Cat.# 05850 |

| StemDiff Definitive Endoderm Kit | StemCell Technologies | Cat.# 05110 |

| PneumaCult ALI Medium | StemCell Technologies | Cat.# 05001 |

| PneumaCult ExPlus Medium | StemCell Technologies | Cat.# 05040 |

| StemFlex medium | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat.# A3349401 |

| Matrigel Growth Factor Reduced | Corning | Cat.# 356230 |

| Matrigel hESC-Qualified Matrix | Corning | Cat.# 354277 |

| UNC-ALI | The MLI Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core, University of Chapel Hill, North Carolina | N/A |

| BEGM | The MLI Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core, University of Chapel Hill, North Carolina | N/A |

Basal cell reporter iPSC

The dual reporter, NKX2-1GFP and P63tdTomato, iPSC lines (BU3 NGPT) were derived from the published single reporter, NKX2-1GFP, iPSC line (BU3 NG), a normal donor iPSC carrying homozygous NKX2-1GFP reporters (Hawkins et al., 2017). The BU3 NG line was targeted and integrated with a P63tdTomato fluorescent reporter using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. A gRNA was designed to target exon 4 of the endogenous TP63 (target sequence TGCGCGTGGTCTGTGTTATA) and a donor template was constructed to contain the tdTomato sequence and removable antibiotic selection cassette via Cre recombination flanked by arms of homology. In this report we used the clone BU3 NGPT c5-cre22, where P63tdTomato fluorescent reporter-integrated clone 5 was further cre-excised to remove selection cassette (sub-clone 22).

Gene corrected CF-iPSCs

Monoallelic correction of homozygous F508del CF iPSC, clone 792, was performed by nucleofecting 1M TrypLE-Select dissociated cells with 5μg Cas9-GFP plasmid (Addgene, 44719), 5 μg of a U6 promoter driven sgRNA plasmid (target sequence ACCATTAAAGAAAATATCAT), 10μg of a plasmid containing a 1.4kb piece of the WT CFTR that includes the exon encoding F508. Repaired clones were identified by ddPCR and Sanger sequencing of long-range PCR products. Clones 1566 (CFTR WT/ F508del) and 1567 (CFTR F508del / F508del) were confirmed by DNA STR fingerprint (match with donor) and karyotype analysis (no abnormalities).

Primary HBECs and human airway tissue

De-identified, cryopreserved human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) were received from the CF Center Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core, Marsico Lung Institute, University of North Carolina where they were harvested and cultured as previously described in detail. Paraffin-embedded sections of de-identified human airway tissue were also received. These samples are exempt from regulation by HHS regulation 45 CFR Part 46. Freshly isolated P0 HBECs were expanded in culture on collagen type I/III-coated tissue culture plates in non-proprietary bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM). At 70-90% confluence HBECs were dissociated with Accutase (Sigma), counted and transferred to human placental type IV collagen-coated membranes (Transwell, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) at a density of 100,000-150,000 cells per 6.5mm insert and differentiated using air-liquid interface conditions in either a non-proprietary medium, “UNC-ALI” medium, or PneumaCult-ALI for 2-3 weeks or longer before analysis. Frequency of each epithelial cell-type was assessed 14 days after establishing ALI culture for both iBC and HBEC samples previously expanded in Basal Cell medium described below. Figure 4F analysis was performed 21 days after establishing ALI culture for both iBC and HBEC samples. Figure S7D analysis was performed 30 days after establishing ALI culture.

Animals

All animal procedures were performed at an AAALAC accredited facility and in accordance with National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Adult mice (Foxn1nu, The Jackson Laboratory) and rats (NIH-Foxn1rnu, Charles River) used for these experiments were housed in the barrier facility of the Brown Institute of Molecular Medicine at the UTHealth. Animals were group housed in autoclaved, individually ventilated cages (IVC), and provided irradiated corncob bedding with cotton square nestlets for enrichment. Animals were fed ad libitum a commercially available, irradiated, balanced mouse diet (no. 5058, LabDiet, St Louis, MO) and had free access to acidified water. A mouse received xenografts was single housed. Rooms were maintained at 21-23°C and under a 12:12-h light:dark cycle. All animals were maintained specific pathogen free (the list of tested pathogens is available upon a request).

METHOD DETAILS

Differentiation of hPSCs into airway organoids

This protocol is based on previously described approaches to derive airway organoid from hPSCs (Hawkins et al., 2017; McCauley et al., 2017) including a detailed step-by-step protocol prior to basal cell medium (McCauley et al., 2018). NKX2-1+ lung progenitors were generated from hPSCs first by inducing definitive endoderm with STEMdiff Definitive Endoderm Kit (Stemcell Technologies) for 60-72 hours. Endoderm-stage cells were dissociated and passaged in small clumps to hES-qualified Matrigel-coated (Corning) tissue culture plates (Corning) in a complete serum free differentiation medium (cSFDM) consisting of a base medium of IMDM (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and Ham’s F12 (Thermo Fisher) with B27 Supplement with retinoic acid (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), N2 Supplement (Invitrogen), 0.1% bovine serum albumin Fraction V (Invitrogen), monothioglycerol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), Glutamax (Thermo Fisher), ascorbic acid (Sigma), and antibiotics. To pattern endoderm into anterior foregut the cSFMD base medium was supplemented with 10 μM SB431542 (Tocris, Bristol, United Kingdom) and 2 μM Dorsomorphin (Stemgent, Lexington, MA) for 72 hours (Green et al., 2011). Cells were then cultured for 9-11 additional days (typically, 144 hr - day 15) in cSFDM containing 3 μM CHIR99021 (Tocris), 10 ng/mL recombinant human BMP4 (rhBMP4, R&D Systems), and 50-100 nM retinoid acid (Millipore-Sigma) to induce NKX2-1 primordial lung progenitors (Serra et al., 2017). NKX2-1+ lung progenitors were sorted by NKX2-1GFP expression for BU3 NGPT or enriched based on the expression of cell surface markers CD47hi/CD26− for non-reporter iPSC (see below) and then were resuspended in three-dimensional growth factor reduced Matrigel (Corning) at a density of 400 cells per μl and pipetted in 25-50 μl droplets onto the base of tissue culture plates (Hawkins et al., 2017). After 10-15 minutes at 37°C to allow gelling of Matrigel airway medium composed of cSFDM containing 250ng/ml FGF2 (rhFGFbasic; R&D Systems), 100ng/ml FGF10, 50nM dexamethasone, 100nM 8-Bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate sodium salt (cAMP; Millipore-Sigma), 100μM 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; Millipore-Sigma), and 10μM Y-27632 (Y; Tocris) (FGF2+10+DCI+Y) was added.

Sorting of PSC-derived lung and airway progenitors

To facilitate directed differentiation from hPSCs, NKX2-1+ lung progenitors and airway progenitors of iBCs were purified by cell sorting. This sorting protocol is further detailed in previous publications (Hawkins et al., 2017; McCauley et al., 2018). On ~ day 15, cells were harvested by incubation with 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA for 15-20 min at 37°C. Trypsin was neutralized and cells were washed with medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher.) Harvested cells were spun at 300 RCF for 5 min and resuspended in the buffer containing Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (Thermo Fisher), 2% FBS, 25mM HEPES 2mM EDTA (FACS buffer) supplemented with 10μM Y-27632 and stained with propidium iodide (PI, ThermoFisher) or calcein blue AM (Thermo Fisher) for live cell selection during flow cytometry. Live cells were sorted based on NKX2-1GFP expression for BU3 NGPT or by staining for CD47 (Biolegend) and CD26 (Biolegend) for non-reporter PSCs and gating for CD47hi/CD26−. Airway progenitors were sorted on ~ day 30 of directed differentiation. Organoids cultured in 3D Matrigel were harvested by incubation with 1 U/mL Dispase (Stemcell technologies) or 2mg/ml Dispase (Thermo Fisher) for ~ 60 min at 37C until Matrigel was fully dissolved. Dissociated organoids were collected with a 1000μl pipette, transferred to a 15ml conical and and centrifuged at 200 RCF for 3 min. The cells were resuspended and incubated in 0.05% trypsin at 37°C for approximately 10min until a single cell suspension was achieved. Trypsin was inactivated by adding 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) in DMEM (Gibco). Cells were then centrifuged at 300 RCF for 5 min at 4°C, counted and resuspended in FACS buffer. 10μM of the cell viability dye Calcein blue (ThermoFisher) was added and Calcein Blue+/NKX2-1GFP+/TP63tdTomato+ or PI−/NKX2.1GFP+/TP63tdTomato+ cells were sorted and replated at 400 cells per μl of density in Matrigel (Corning) and cultured in FGF2+10+DCI+Y medium.

Generation, purification and maintenance of iBCs

The iPSC-derived basal cells (iBCs) were generated from airway organoids in FGF2+10+DCI+Y described above. For BU3 NGPT, one day after (unless indicated) sorting and replating NKX2-1GFP+/TP63tdTomato+ on ~ day 30 of directed differentiation, culture medium was switched to Pneumacult ExPlus (Stemcell Technologies) supplemented with 1μM A83-01 (Tocris), 1μM DMH1 (Tocris), and 10μM Y-27632 (Basal cell medium). In some cases, Pneumacult Ex (Stemcell technologies) supplemented with 1μM A83-01, 1μM DMH1, and 10μM Y-27632 was used as indicated in figures. For non-reporter iPSCs, single cells dissociated from airway organoids in FGF2+10+DCI+Y were replated without a sorting step and changed to basal cell medium as above. Viable iBCs at ~ Day 40 of directed differentiation or later were sorted based by dissociating organoids to a single-cell suspensions as above and flow sorting based NKX2-1GFP+/TP63tdTomato+/NGFR+ cells for BU3 NGPT, or by labelling with mouse monoclonal anti-NGFR (Cat.# 345108, Biolegend) and mouse monoclonal anti-EpCAM (Cat.# 24234, Biolegend) with isotype controls (mouse monoclonal IgG1k APC-conjugated, Cat.#400122, Biolegend). Both anti-NGFR and anti-EpCAM antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:100 in a suspension of 1x106 cells per 50 or 100μl on ice for 30 min. For these sorting experiments a MoFlo Astrios Cell sorter (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) was used at Boston University Medical Center Flow Cytometry Core Facility or BD FACSMelody (BD biosciences) was used at the UTHealth Flow Cytometry Service Center. Sorted iBCs were either replated in ALI culture (see below) or resuspended in Matrigel (Corning) droplets at 400 cells/ul, plated and cultured in basal cell medium as above for expansion of iBCs. iBCs in 3D Matrigel droplets were fed with basal cell medium every 2-3 days and required passaging every ~ 10-14 days. iBCs were cryopreserved by first dissociating organoids to single-cells as above and resuspending in basal cell medium supplemented with 10% dimethylsulfoxide (ThermoFisher) and transferred to cryovials. Cryovials were placed in cryostorage containers in a −80°C freezer to cool at −1°C /min for 24 hours and then transferred to −150°C freezer or into liquid nitrogen the following day for long-term storage. iBCs were thawed by warming to 37°C in a water or bead bath, diluting in 5-10ml of basal cell medium (37°C) added dropwise and centrifuged at 300 RCF for 5min. The cell pellet was then resuspended in Matrigel at 1000cells/μl, plated in tissue culture plates and after 10-15 min at 37°C basal medium was added to the well. Expanded or cryopreserved cells-derived organoids in 3D Matrigel were dissociated and sorted for iBC makers prior to replating in ALI culture.

ALI culture of iBCs or other iPSCs-derived AECs

To differentiate iBCs in Air Liquid Interface (ALI) culture we adapted existing, detailed protocols for primary HBECs (Fulcher and Randell, 2013). iPSCs-derived airway epithelial cells (AECs) including iBCs were seeded on 6.5 mm Transwells with 0.4 μm pore polyester membrane inserts (Corning Inc., Corning, NY), coated with Matrigel diluted in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) according to the recommended dilution factor from the lot-specific certificate of analysis, at 150,000-200,000 cells per insert with a medium used to culture each cell culture (e.g. iBCs cultured in Basal cell medium were plated on Transwells and cultured in Basal cell medium) for 3 to 7 days. Once visual inspection confirmed the Transwell membranes were covered by a confluent sheet of cells the culture medium was switched to PneumaCult-ALI medium (Stemcell Technologies) or non-proprietary “UNC-ALI medium (Fulcher and Randell, 2013) in both apical and basal chambers. The following day, the medium from top chamber was removed and the cells were further differentiated in air-liquid interface conditions for 2-3 weeks or longer before analysis. ScRNA-Seq (Figure 4A-E), qRT-PCR (Figure 4F, S7E) were analyzed 21 days after establishing ALI culture.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry analysis was performed as described above. NKX2-1GFP, TP63tdTomato expression or fluorochrome-conjugated primary antibodies (listed in the Key Resources Table) were detected using a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences), Stratedigm S1000 EXi (Stratedigm Inc, San Jose, CA) or MoFlo Astrios (Beckman Coulter) at Boston University Medical Center or with BD FACSMelody and BD FACSChorus software (BD Biosciences) at the UTHealth Flow Cytometry Service Center. Calcein blue or PI was used to identify viable cells depending on the flow cytometer used. FlowJo software (BD biosciences) was used for further analysis.

Histological analysis