This editorial refers to ‘Genetic lineage tracing reveals poor angiogenic potential of cardiac endothelial cells’, by T. Kocijan et al., pp. 256–270.

Ischaemic heart disease (IHD) remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide.1 The global burden of IHD remains extremely high with over 126 million people living with the disease and 8.9 million deaths in 2017.1 Efficient and rapid restoration of a functional blood vessel network is critical to prevent further cardiomyocyte death in patients following myocardial infarction (MI). The primary clinical revascularization strategies are percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting. Despite timely reperfusion of the myocardium in the majority of cases, the number of patients that will go on to develop heart failure as a consequence of left ventricular impairment following acute MI continues to rise worldwide.1 Hence, new therapeutic approaches to enhance myocardial perfusion and promote cardiac repair and regeneration are urgently required.

Formation of new vascular networks is a critical early step during cardiac regeneration in early neonatal mice,2 generating a functional framework for subsequent regeneration of the myocardium. However, in most adult mammals, regenerative ability in the heart rapidly declines in the days following birth.2 Despite this, even in adulthood, the heart post-MI has been shown to be an active site of angiogenesis, albeit at a level that is insufficient to support adequate tissue repair or regeneration.3 Therefore, significant research has aimed to understand and thereby intervene in order to facilitate endogenous neovascularization in the injured adult mammalian heart.

Vector-assisted gene delivery of pro-angiogenic factors holds therapeutic promise for enhancement of myocardial neovascularization. Pre-clinical studies have shown improved cardiac perfusion and function after administration of the pro-angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) after MI.4 However, human gene therapy clinical trials aiming to improve patient outcomes in IHD through VEGF delivery have reported mixed results so far.5 Therefore, a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that regulate myocardial neovascularization may help to explain previous disappointing outcomes in humans, and to identify strategies to improve future pro-angiogenic clinical strategies.

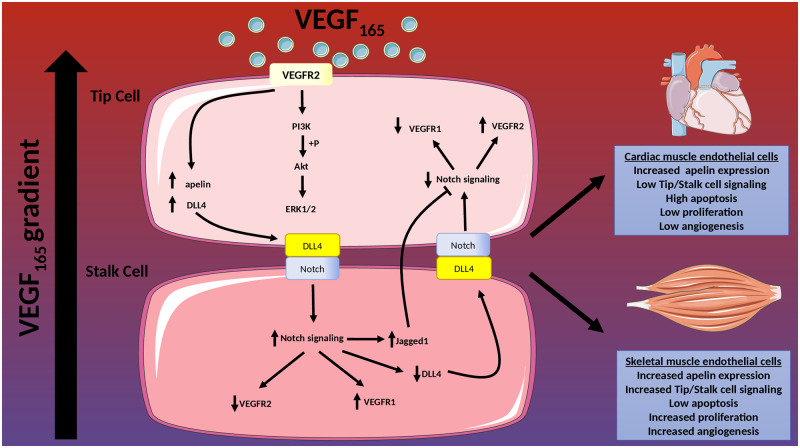

Kocijan et al.6 tackle the potential reasons underpinning insufficient endogenous angiogenesis in the adult heart. Previously, the authors have successfully promoted new blood vessel formation using delivery of VEGF in skeletal muscle after hindlimb ischaemia (HLI).7 However, when the same strategy was assessed in the ischaemic myocardium, no substantive angiogenic response was detected.8 In the current study, they aimed to understand whether restricted angiogenic responses in the adult heart could be enlightened through comparative analysis between responses in skeletal and cardiac muscle, together with mechanistic insight into tumour angiogenesis. They used a lineage tracing mouse model to label sprouting endothelial cells (EC), driven by apelin. Apelin expression is normally low in the adult vasculature but is increased in response to hypoxia and is associated with sprouting angiogenesis.9,10 As an angiogenic trigger, a gene therapy approach was used by directly injecting human AAV-VEGF165 into either the tibialis anterior or the left ventricular wall of uninjured adult mice. As a result, VEGF induced apelin expression in both heart and skeletal muscle ECs although in the heart, apelin-positive ECs largely remained quiescent and failed to proliferate sufficiently to form new vessels. Conversely, in skeletal muscle, apelin-expressing ECs proliferated and underwent effective angiogenesis. This was driven by Notch signalling, indicated by an increased expression of Notch target genes Hes1, Hey1, and Notch1, an effect that was not evident in the heart. This highlights important fundamental differences in the functional responses of the vascular endothelium to pro-angiogenic stimuli in diverse tissue settings. This is likely due to differences in environmental cues as well as inherent molecular and cellular heterogeneity in the endothelium between these tissues.11 Importantly, single-cell transcriptional profiling has been used to successfully delineate endothelial cell heterogeneity in multiple organs and tissues, and also in response to ischaemic injury in the adult mouse heart.11,12 To further understand the differential responses observed in vivo, the authors isolated cardiac and skeletal muscle ECs and, following exposure to VEGF, quantified proliferation and angiogenesis in an ex vivo spheroid model. Interestingly, despite VEGF inducing apelin expression in ECs from both tissues, only those from skeletal muscle were capable of forming angiogenic sprouts. Following interrogation of the well-characterized tip/stalk cell signalling pathway13 they showed differences in the expression of key genes such as DLL4 and Notch with cardiac ECs having reduced expression. Moreover, they showed reduced signalling activity of VEGFR2. This suggests that cardiac ECs may not be as proficient as skeletal muscle ECs at initiating tip/stalk cell-mediated angiogenesis, at least with VEGF serving as the sole angiogenic trigger (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Angiogenesis in response to VEGF differs between cardiac muscle endothelial cells and skeletal muscle endothelial cells. When exposed to VEGF as an angiogenic trigger, cardiac muscle endothelial cells are not able to elicit a sufficient angiogenic response via tip/stalk cell signalling and undergo proliferation when compared with skeletal muscle endothelial cells.

The observation that apelin+ ECs in the healthy heart fail to proliferate conflicts with previous studies showing that apelin+ cells are key mediators of vascular repair and can actively drive proliferation following MI and HLI.9,14 It is important to note that Kocijan et al. did not assess the response of apelin expressing ECs to ischemic injury in each tissue type, and it is conceivable that the reluctance of apelin-expressing cardiac ECs to undergo neovasculogenesis may be due to a lack of regenerative demand, and this warrants further study.

The authors turned their sights to cancer-associated angiogenesis with the postulation that poor neovasculogenic capacity may provide a potential reason as to why the heart rarely develops tumours. Lung cancer cells were implanted into the tibialis anterior or the left ventricle of adult mice over 3, 6, and 9 days using the apelin-driven lineage tracing mouse to label sprouting ECs. In tumours that were implanted in skeletal muscle, the number of ECs increased over time. Conversely, in the heart, despite ECs switching on apelin expression following cancer cell implantation, cell numbers gradually decreased due to apoptosis. As cell division is limited in the heart with most cardiomyocytes not exchanged during a normal lifespan15 it seems plausible that, in evolutionary terms, the heart may have fundamentally shed its angiogenic potential beyond development, unlike tissue systems with significant growth requirements like skeletal muscle.

In summary, this study by Kocijan et al. provides evidence that the skeletal muscle maintains a poised angiogenic response to a larger degree than the heart and expands our understanding on the dynamics of angiogenesis in response to VEGF in different vascular beds. Despite the urgent need to discover novel therapeutics to drive adult cardiac regeneration it is vital not to overlook the complexity of the processes underpinning angiogenesis in the pathological environment. Moreover, it is important to remember that despite the skeletal muscle retaining its angiogenic potential to a larger degree the majority of clinical trials aiming to revascularize peripheral tissues using delivery of pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF in conditions such as critical limb ischaemia have proven disappointing.5 Therefore, further insight should be gained on the fundamental biology of pathological ischaemia as well as in interactions between different cells within the complex milieu of the ischaemic tissue, incorporating accompanied biological processes like inflammation and fibrosis. Lessons learned from studies of the deeper molecular mechanisms associated with regeneration of the vasculature will be crucial to assist the development of tailored and tissue-specific novel therapeutics aimed at improving reperfusion and repair in ischaemic patients.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

E.S. is supported by British Heart Foundation Studentship (R44601), British Heart Foundation of Translational Cardiovascular Sciences and European Research Council Advanced Grant VASCMIR. M.B. is supported by the British Heart Foundation (FS/16/4/31831) and the BHF Centre for Vascular Regeneration (RM/17/3/33381).

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of Cardiovascular Research or of the European Society of Cardiology.

References

- 1. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longenecker CT, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Martin SS, Matsushita K, Moran AE, Mussolino ME, Perak AM, Rosamond WD, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Shay CM, Spartano NL, Stokes A, Tirschwell DL, VanWagner LB, Tsao CW, Wong SS, Heard DG; On behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020;141:E139–E596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Sadek HA.. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science 2011;331:1078–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cochain C, Channon KM, Silvestre JS.. Angiogenesis in the infarcted myocardium. Antioxidants Redox Signal 2013;18:1100–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bulysheva AA, Hargrave B, Burcus N, Lundberg CG, Murray L, Heller R.. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A gene electrotransfer promotes angiogenesis in a porcine model of cardiac ischemia. Gene Ther 2016;23:649–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ylä-Herttuala S, Baker AH.. Cardiovascular Gene Therapy: past, present, and future. Mol Ther 2017;25:1095–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kocijan T, Rehman M, Colliva A, Groppa E, Leban M, Vodret S, Volf N, Zucca G, Cappelletto A, Piperno GM, Zentilin L, Giacca M, Benvenuti F, Zhou B, Adams RH, Zacchigna S. Genetic lineage tracing reveals poor angiogenic potential of cardiac endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 2021;117:256–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. Tafuro S, Ayuso E, Zacchigna S, Zentilin L, Moimas S, Dore F, Giacca M.. Inducible adeno-associated virus vectors promote functional angiogenesis in adult organisms via regulated vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Cardiovasc. Res 2009;83:663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zentilin L, Puligadda U, Lionetti V, Zacchigna S, Collesi C, Pattarini L, Ruozi G, Camporesi S, Sinagra G, Pepe M, Recchia FA, Giacca M.. Cardiomyocyte VEGFR‐1 activation by VEGF‐B induces compensatory hypertrophy and preserves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. FASEB J 2010;24:1467–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu Q, Hu T, He L, Huang X, Tian X, Zhang H, He L, Pu W, Zhang L, Sun H, Fang J, Yu Y, Duan S, Hu C, Hui L, Zhang H, Quertermous T, Xu Q, Red-Horse K, Wythe JD, Zhou B.. Genetic targeting of sprouting angiogenesis using Apln-CreER. Nat Commun 2015;6:6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tempel D, de Boer M, van Deel ED, Haasdijk RA, Duncker DJ, Cheng C, Schulte-Merker S, Duckers HJ.. Apelin enhances cardiac neovascularization after myocardial infarction by recruiting Aplnr+ circulating cells. Circ Res 2012;111:585–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalucka J, de Rooij LPMH, Goveia J, Rohlenova K, Dumas SJ, Meta E, Conchinha NV, Taverna F, Teuwen LA, Veys K, García-Caballero M, Khan S, Geldhof V, Sokol L, Chen R, Treps L, Borri M, de Zeeuw P, Dubois C, Karakach TK, Falkenberg KD, Parys M, Yin X, Vinckier S, Du Y, Fenton RA, Schoonjans L, Dewerchin M, Eelen G, Thienpont B, Lin L, Bolund L, Li X, Luo Y, Carmeliet P.. Single-cell transcriptome atlas of murine endothelial cells. Cell 2020;180:764–779.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li Z, Solomonidis EG, Meloni M, Taylor RS, Duffin R, Dobie R, Magalhaes MS, Henderson BEP, Louwe PA, D’Amico G, Hodivala-Dilke KM, Shah AM, Mills NL, Simons BD, Gray GA, Henderson NC, Baker AH, Brittan M.. Single-cell transcriptome analyses reveal novel targets modulating cardiac neovascularization by resident endothelial cells following myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J 2019;40:2507–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carmeliet P, Jain RK.. Molecular Mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011;473:298–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Masoud AG, Lin J, Azad AK, Farhan MA, Fischer C, Zhu LF, Zhang H, Sis B, Kassiri Z, Moore RB, Kim D, Anderson CC, Vederas JC, Adam BA, Oudit GY, Murray AG.. Apelin directs endothelial cell differentiation and vascular repair following immune-mediated injury. J Clin Invest 2019;130:94–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabé-Heide F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisén J.. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 2009;324:98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]