Abstract

Endothelial cells (ECs) are sentinels of cardiovascular health. Their function is reduced by the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, and is regained once pathological stimuli are removed. In this European Society for Cardiology Position Paper, we describe endothelial dysfunction as a spectrum of phenotypic states and advocate further studies to determine the role of EC subtypes in cardiovascular disease. We conclude that there is no single ideal method for measurement of endothelial function. Techniques to measure coronary epicardial and micro-vascular function are well established but they are invasive, time-consuming, and expensive. Flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) of the brachial arteries provides a non-invasive alternative but is technically challenging and requires extensive training and standardization. We, therefore, propose that a consensus methodology for FMD is universally adopted to minimize technical variation between studies, and that reference FMD values are established for different populations of healthy individuals and patient groups. Newer techniques to measure endothelial function that are relatively easy to perform, such as finger plethysmography and the retinal flicker test, have the potential for increased clinical use provided a consensus is achieved on the measurement protocol used. We recommend further clinical studies to establish reference values for these techniques and to assess their ability to improve cardiovascular risk stratification. We advocate future studies to determine whether integration of endothelial function measurements with patient-specific epigenetic data and other biomarkers can enhance the stratification of patients for differential diagnosis, disease progression, and responses to therapy.

Keywords: Endothelial function, Cardiovascular

This manuscript was independently handled by Executive Deputy Editor Pasquale Maffia.

1. Defining endothelial function and dysfunction

1.1 What is endothelial dysfunction?

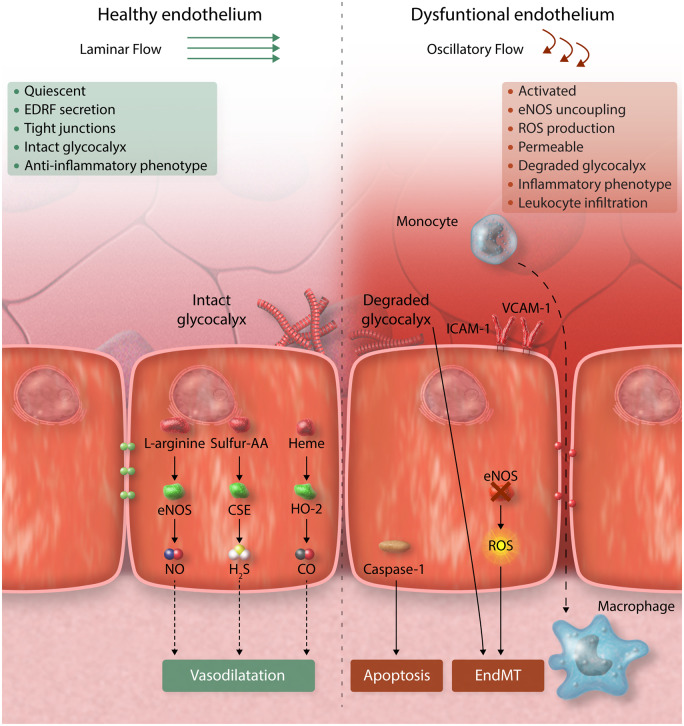

The vascular endothelium acts a semipermeable barrier to regulate an exchange of fluids, nutrients, and metabolites, and is critical to haemostasis and vascular health. In healthy arteries, endothelial cells (ECs) exist in a quiescent state that is maintained by laminar blood,1,2 and by circulating cytoprotective factors such as high-density lipoprotein.3 However, several stimuli including chronic disease states,4 metabolic conditions [e.g. type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), obesity, dyslipidemia], smoking,5 and disturbed blood flow6–8 interrupt the quiescent phenotype and drive EC dysfunction.9,10 In 1998, Hunt and Jurd10 defined dysfunctional ECs by five key characteristic mechanisms: (i) loss of vascular integrity, (ii) increased expression of adhesion molecules, (iii) pro-thrombotic phenotype, (iv) production of cytokines, and (v) upregulation of human leucocyte antigen molecules. It is now known that EC dysfunction is not a single-pathological state but instead represents a spectrum of phenotypes associated with pathophysiologically heterogeneous alterations in vascular tone, permeability, inflammation, and de-differentiation, leading to the loss of homeostatic functions of endothelium (Figure 1). Indeed, recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies have revealed multiple distinct EC subtypes for instance with aneurysms and atherosclerosis, thus emphasizing the heterogeneity of ECs in diseased tissues.11–14 Aside from tissue-resident endothelium, EC dysfunction also involves changes in circulating endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) and endothelial-derived micro-vesicles (EMVs) that have major roles in cardiovascular health and disease.

Figure 1.

Endothelial dysfunction describes multiple phenotypic states. Left panel: In homeostatic conditions, the healthy endothelium regulates the physiological vascular function and structure through multiple beneficial effects of nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen sulphide (H2S), and carbon monoxide (CO), as detailed in the text. Right panel: Dysfunctional endothelium is characterized by decreased production of NO and chronic increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) able to overwhelm the intra-cellular antioxidant defence leading to onset and progression of atherosclerosis. AA, amino acids; EndMT, endothelial–mesenchymal transition; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

1.2 Vascular tone, nitric oxide, and superoxide anion

In physiological conditions, maintenance of appropriate endothelial function provides vasorelaxant and protective properties through release of vasoactive substances such as nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin (PGI2), and/or endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor.4,9,10 For their discovery of NO as a signalling molecule in the cardiovascular system, Ferid Murad, Robert Furchgott, and Louis Ignarro earned the Nobel Prize for medicine in 1998. NO, a gaseous mediator produced by ECs, is generated from the nitrogen atom of L-arginine and O2,15 and catalysed by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS).16 While primarily defined through its regulation of vasorelaxation and vascular tone, NO exerts several atheroprotective effects including protection against oxidative stress, platelet activation and aggregation, inflammation, and smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation.17 However, the bioavailability of NO is reduced by numerous cardiovascular risk factors.18 eNOS dimer is the main contributor to homeostatic NO in healthy cells. In pathology, when important co-factors such as tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) are depleted, eNOS becomes uncoupled, and its monomers contribute to reactive oxygen species (ROS) production19 which is a driver of EC dysfunction. Reduced bioavailability of NO can also be due to oxidative inactivation. Indeed, loss of BH4 is often linked to vascular oxidative stress, characteristic for all major clinical risk factors for atherosclerosis, including diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and smoking.20 In human vasculature, endothelial and smooth muscle NADPH oxidases contribute to superoxide anion production.21–23 Rapid scavenging of NO by superoxide with generation of strongly prooxidant peroxynitrite (ONOO−) remains the principal mechanism of endothelial dysfunction in wide range of clinical conditions. ONOO− is in turn able to oxidize BH4 to BH2 contributing to eNOS uncoupling.24 In some cases, eNOS substrate L-arginine or co-factor NADPH bioavailability may be limited, or eNOS expression inhibited by epigenetic modifications, including miRNA. The relative importance of these distinct mechanisms of loss of NO bioavailability may differ in individual patients leading to the need for precision medicine approaches. These could be achieved by biomarker screening, such as plasma BH4, miRNA, L-arginine allowing for targeted approach to pathology underlying the dysfunction. Lack of bioavailability of other mediators, such as prostacyclin, can provide an important factor in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. For example, cardiovascular effects of Cox-2 inhibitors have been linked to loss of vascular PGI2 production which promoted development of endothelial dysfunction.25

1.3 Vascular permeability and inflammation

It is well recognized that pro-atherogenic stimuli and cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes, obesity, and smoking cause functional and structural changes in the permeability properties of the endothelium. These alterations are characterized by a rise in the movement of plasma across the vessel wall and into the surrounding tissues, comprehensively reviewed elsewhere.26 Numerous studies show that endothelial permeability, inflammation, and atherosclerosis are inextricably linked. Interleukin (IL)-1β is a cytokine that is activated by the NLRP3 inflammasome, a master regulator involved in innate immunity. Thus, as a result of NLRP3 inflammasome/IL1β activation by cholesterol crystals, lipids and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, pathogen-associated molecular patterns, and disturbed blood flow,27–34 ECs will be activated and express adhesion molecules (e.g. vascular adhesion molecule-1, inter-cellular cell adhesion molecule-1, E-selectin) to drive vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis initiation and progression. Mendelian randomization studies have now shown strong links between specific inflammatory proteins and lipid metabolism in patients with an inflammatory status, providing the impetus to develop novel systemic and vascular immunomodulatory approaches to address the public health challenge of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Thus, genetic screens linking metabolic and plasma proteomic profiles with causal effects are becoming an attractive approach in the cardiovascular precision medicine arena35,36 and may provide both novel targets and/or an improved prognostic tool for stroke, ischaemic heart disease, and T2DM.37

1.4 Phenotypic plasticity

The full details of EC plasticity are outside the scope of this ESC Position Paper but have been extensively reviewed elsewhere.38–40 It is now established that endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), a process characterized by loss of EC markers, gain of mesenchymal markers, activation, and delamination, is of particular relevance in atherosclerosis.40 Endothelial-lineage tracing studies from the Simons laboratory revealed that ECs activated in response to TGFβ signalling undergo EndMT leading to migration, de-differentiation, and contribution to plaque formation and progression.41 Kovacic et al.42 used endothelial-specific lineage-tracking, to show that EndMT-derived fibroblast-like cells are present in atherosclerotic lesions, and co-express endothelial and fibroblast/mesenchymal proteins, a recognized hallmark of EndMT. Further studies have revealed that EndMT is driven by disturbed flow, oxidative stress, and hypoxia42–44; all of which trigger progression of atherosclerosis. However, the contribution of EndMT-derived cells to plaque development is an area of ongoing investigation.

1.5 Organ-specific EC specialization

ECs are specialized in different vascular beds, such as the unique vasculature of the kidneys or the blood–brain barrier. Specific subtypes of ECs have also been found in adipose tissue, gut, and other tissues, and multiple distinct EC subtypes have been revealed by single-cell sequencing in aorta13 and atherosclerotic plaques.11 Unravelling the as yet unknown molecular pathways that specify and sustain each organ functional and structural diversity will set the stage for deciphering the pathogenesis of several disorders, allowing future attempts at reversal of endothelial dysfunction and improved patient outcome. At the same time, while molecular mechanisms appear to differ between different vascular beds, clinically measured vascular dysfunction can correlate between different arterial beds45 as well as between arterial and venous endothelium46 suggesting that endothelial dysfunction can be systemic.

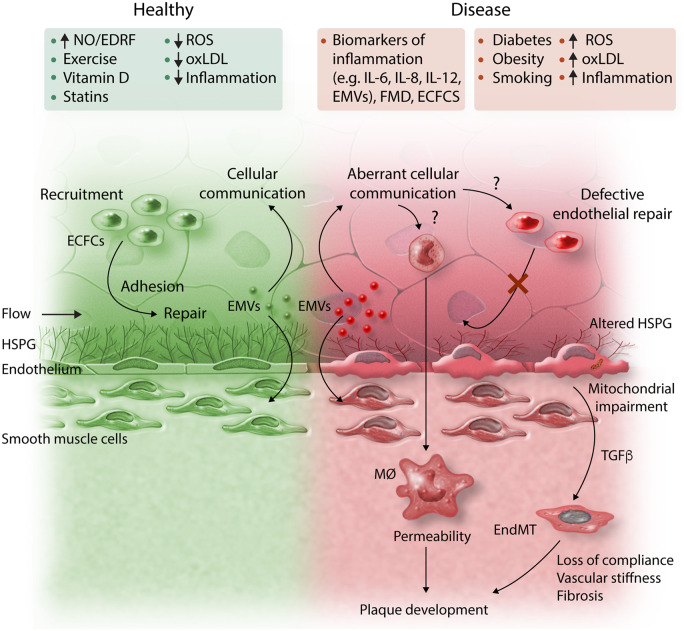

1.6 ECFCs and EMVs

ECFCs comprise a heterogeneous population of cells that have distinct roles in angiogenesis and vascular repair. A number of reports suggest their numbers increase with disease activity in patients with vasculitis and other vascular disorders and that progenitor repair cells become exhausted in disease (Figure 2).47,48 ECFCs can be cultured from patients and analysed for pathophysiological properties and epigenetic markers and this approach has the potential to inform precision cardiovascular medicine. EMVs are extracellular vesicles of 0.2–5 μm diameter that are produced by ECs in response to a variety of stimuli.49 They can exert paracrine and autocrine actions on vascular cells with the potential to modulate key intra-cellular signalling pathways, promoting disease progression via transfer of a range of bioactive molecules (growth factors, proteases, and microRNAs) to adjacent cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the endothelial factors underlying cardiovascular risk. ECFCs, endothelial colony-forming cells; EMVs, endothelial micro-vesicles; EndMT, endothelial–mesenchymal transition; FMD, flow-mediated dilatation; HSPG, heparan sulphate proteoglycans; IL, interleukin; MØ, macrophage; MR-proADM, mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin; NO, nitric oxide; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TGFβ, transforming growth factor beta.

1.7 Summary

Although a conventional definition of endothelial dysfunction has focused on NO dysregulation and an altered redox status,50 EC dysfunction involves a range of plastic phenotypic states with inflammation and enhanced permeability. Indeed, it is clear from recent studies that ECs assume multiple diverse phenotypes associated with various disease states including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and the development of heart failure (Figure 1). This is exemplified by fate mapping and single-cell RNAseq studies that have revealed multiple EC phenotypes associated with health and disease11–14 and recent insights into the function of ECFCs and EMVs in CVD (Figure 2). Together, these findings have led to growing interest in assessing endothelial function by a range of traditional and novel methods, discussed below, to inform about individual patient risk, to guide best therapy, clinical management, and ultimately to establish whether it is feasible to target endothelial dysfunction and attenuate CVD progression.51,52 This could enhance the field in applying novel endothelial function tests and endothelial damage biomarkers to innovate a more personalized approach to cardiovascular medicine.

2. Measuring endothelial function

The ideal method to assess endothelial function should be non-invasive, easy to use, prospectively validated in different cohorts and ethnic groups, with an incremental value over standard, clinically established risk markers, cost-effective, measured according to methodological consensus and providing reference values as a basis for treatment.53,54 Both invasive and non-invasive methods to assess vascular endothelial function have their advantages and disadvantages (Table 1). The basic principle of these methods, however, is similar. Healthy arteries dilate in response to reactive hyperaemia via increased shear stress (flow-mediated vasodilatation) or in response to endothelium-dependent vasodilators, such as acetylcholine (Ach), bradykinin, or serotonin, via release endothelium-derived vasoactive substances, for example, NO.55 In disease states, this process of endothelial-dependent dilatation may be reduced or absent. It should be noted that vascular responses are not only determined by local function at the point of measurement but also by the structure and physiology of resistance arteries and micro-vasculature. Furthermore, vascular dysfunction can also be endothelium-independent function via alterations in vascular structure and SMC function rather than changes in EC. Responses to exogenous NO donors (e.g. glycerol-trinitrate) or vasodilators acting directly on vascular smooth muscle (e.g. adenosine) can be compared to differentiate endothelium-dependent from endothelium-independent responses. This section focuses on methods which are already established and which have the perspective to be implemented in clinical practice. Research methods, such as infusion of NO synthase inhibitors, such as L-NMMA, are out of the scope of this paper and will not be discussed in detail. It should be noted that our assessment of the various methods for quantifying endothelial function should not be interpreted as a recommendation of any particular product or technology manufacturer.

Table 1.

Techniques used in to assess endothelial function

| Technique | Vascular bed | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary epicardial function |

|

|

|

| Coronary micro-vascular function |

|

Assessment in the coronary micro-vasculature |

|

| Venous plethysmography |

|

|

|

| Flow-mediated vasodilation of brachial artery |

|

|

|

| Finger plethysmography |

|

|

|

| Retinal endothelial function | Retinal arterioles |

|

|

2.1 Coronary circulation

2.1.1 Coronary epicardial function

Coronary endothelial function is assessed by performing measurements in both epicardial and resistance vessels. Although these methods are invasive, they have the advantage of measuring EC function directly in a clinically important vascular bed. Vasomotor responses of epicardial coronary arteries are measured using quantitative coronary angiography or intra-vascular ultrasound (IVUS) to quantify changes in vessel diameters in response to endothelium-dependent pharmacological interventions. Vessels and segments with an intact endothelium vasodilate in response to Ach and other endothelial-stimulating substances, whereas vessels with dysfunctional endothelium will exhibit reduced vasodilatation or vasoconstriction due to a direct activation of muscarinic receptors on vascular SMCs.56,57 The observation that endothelial-dependent flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) of coronary epicardial vessels is impaired in atherosclerosis58,59 inspired studies of responses to flow in the peripheral vasculature later as a potential surrogate indicator of coronary artery disease (CAD) (see below). Finally, it should be mentioned that this technique should be used with caution, as serious (although rare) side effects may occur that carry risks for the patient, such as severe coronary vasoconstriction or the induction of arrhythmias.

2.1.2 Coronary micro-vascular function

Changes in coronary blood flow (CBF) have been suggested as a surrogate parameter for micro-vascular function.60 Coronary flow reserve (CFR) is defined as the ratio of maximal CBF during maximal coronary hyperaemia in response to a stimulus (such as adenosine infusion, pacing, or exercise), divided by the resting CBF. This maximal blood flow response (CFR) is both endothelium and non-endothelium dependent and a CFR <2.0 is considered abnormal.61 There are no invasive methods for measuring CBF directly in clinical practice. Instead, wire-based Doppler flow velocity or thermodilution techniques are used as surrogates but these are technically challenging and can lack reproducibility. Thus, there is a need for an accurate method for measurement of volumetric CBF. To determine endothelium-dependent micro-vascular function, the percentage increase in CBF in response to endothelial-dependent vasodilation is analysed. Non-invasive functional tests have also been developed to assess the coronary micro-vasculature, which include positron emission tomography,62 myocardial perfusion imaging,63 blood oxygen level-dependent MRI,64 and echocardiography.63

2.2 Peripheral techniques to assess endothelial function

The abovementioned invasive techniques may be suitable for patients requiring coronary angiography for other clinical indications. However, invasive functional coronary angiograms may not be indicated or feasible for assessment of vascular function in the asymptomatic patient. Because of this, non- or less-invasive surrogate techniques have been developed to quantify macro-vascular as well as micro-vascular endothelial function.65–67 While these techniques can be used to assess the general function of the vasculature, they do not provide information on local vascular dysregulation, for example, dysfunction at branch and bends exposed to disturbed shear stress.68–70

2.2.1 Plethysmography of the forearm circulation

This technique measures changes in forearm blood flow by plethysmography in both arms in response to vasoactive substances which are introduced via a cannulated brachial artery.71,72 An advantage is that responses to vasoactive hormones or drugs can be quantified therefore providing information on both endothelial-dependent and endothelial-independent vasodilation. The infused hormones and drugs have negligible systemic effects, and therefore, the contralateral limb can be used as an internal control. A disadvantage is that this technique is considered semi-invasive nature due to the reliance on arterial cannulation.

2.2.2 Flow-mediated vasodilation of brachial artery

Due to its non-invasive approach, flow-mediated vasodilatation (FMD) of the brachial artery has become the most widely used technique to evaluate endothelial function. The technique quantifies the ability of larger conduit arteries to dilate in response to reactive hyperaemia after a brief (5 min) suprasystolic occlusion of the brachial artery using a blood pressure cuff. The resultant reactive hyperaemia causes an increase in endothelial shear stress in upstream artery, which in turn stimulates release of NO. Celermajer et al.73 were the first to evaluate this response in vivo by measuring changes in the diameter of the brachial artery by ultrasound, later shown to be NO-dependent,74–76 although other vasodilator pathways may be involved.77 Of note, FMD assessment of peripheral endothelial function has been shown to correlate with coronary artery endothelial function.65,67 Although FMD may appear to be a simple technique, it is challenging and necessitates extensive training of operators and standardization.78–81 This is outlined in dedicated guidelines78,81–83 which highlight the critical importance of image acquisition and site selection, study preparation, cuff occlusion time, sphygmomanometer probe position, and application of edge-detection software. These guidelines are of critical importance, as they emphasize the need to standardize protocols and technology to improve reproducibility and data interpretation of FMD.84 The semi-automatic measurement of brachial FMD with self-adjusting ultrasound probes and automatic edge detection of the arterial wall will likely facilitate the usage in clinical practice and has already established reference values for a Japanese population.85 While FMD assesses the function of conduit arteries, the stimulus for FMD is an important parameter of peripheral micro-vascular function because reactive hyperaemia is dependent on maximal forearm resistance.86,87 Indeed, shear stress and velocity changes induced by hyperaemia have shown stronger correlations with cardiovascular risk factors than FMD88 and these parameters also predict cardiovascular outcomes.89,90 Moreover, baseline brachial artery diameter measurements per se have been shown to correlate with clinical outcomes.91,92 This finding reveals a significant limitation of the in vivo assessment of endothelium-dependent vasodilation. In contrast to the ex vivo situation, the baseline arterial tone cannot be standardized. Therefore, the amount of additional dilatation depends on the initial diameter of the vessel and could paradoxically show poor FMD in a situation of initial vasodilation due to a well-functioning endothelium (e.g. in pregnancy or in hyperthermia). These influencing factors strongly warrant a strict standardization of the measurement environment (e.g. room temperature, resting phase) and the consideration of clinical conditions that may influence baseline diameter and vasodilation.81

2.2.3 Finger plethysmography

Endothelial function measurement using peripheral arterial tonometry was first used by Bonetti et al.93,94 to identify patients with early coronary atherosclerosis. A device has been developed to quantify pulsatile arterial volume changes by finger plethysmography. Plethysmographic recordings of the finger arterial pulse wave amplitude are captured with pneumatic probes.94 In this technique, increased arterial blood volume in the fingertip leads to increased pulsatile arterial column changes, thereby increasing the measured signal. Similar to FMD, a pressure cuff is placed on the arm and used to induce reactive hyperaemia in one arm. It is notable that measurements in the contralateral arm serve as an internal control that can be used to correct for any changes in vascular tone that may occur during the test. An index between the two arms is, therefore, calculated as a marker for endothelial function. It should be noted however that pulse amplitude augmentation in response to reactive hyperaemia is a complex response because it integrates changes due to altered flow in addition to vessel dilatation and it is only partially NO-dependent.95 Further studies demonstrated that impaired digital EC function correlates with coronary micro-vascular function in patients with early atherosclerosis66 and that this parameter predicts cardiovascular events.96 In two large cross-sectional studies (>1900 patients in the Framingham cohort97,98 and >5000 individuals in the Gutenberg Heart Study99), vascular dysfunction measured by digital plethysmography was associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors but had little or no correlation with FMD, suggesting that these measurements provide information on different aspects of vascular biology. A disadvantage of the proprietary device is the high cost per measurement system, the lack of reusability, and the limited parameters offered for further analysis. Moreover, we recognize that technologies such as finger plethysmography that rely on a small number of device manufacturers may be more vulnerable to commercial factors.

2.2.4 Retinal endothelial function

For the assessment of the retinal endothelial function, several types of provocation are possible including flicker light.100 The vessel’s reactions are at least partially dependent on NO release and partially attributed to neurovascular coupling.100,101 Solid data for patient groups are still lacking, partly due to variation in the flicker response between individuals due to variation in the baseline diameter of retinal vessels.102,103 Moreover, a consensus on the protocol used in order to achieve a better comparability of study results, is still lacking.104 These concerns should be addressed, as should the study of larger and more representative groups of individuals and patient cohorts before recommendations for wider use in clinical practice and prevention can be made. Nevertheless, flicker-induced dilatation of retinal vessels has been shown to depend on age and gender in individuals free of major risk factor burden and prevalent disease.105 It is impaired in patients with obesity,104,106 renal disease,107 and diabetes compared to age-matched healthy controls.108,109 In hypertension, flicker-induced dilation is also reduced110,111 and it is associated with an increase of inflammatory biomarkers.110 Since many of the studies of retinal flicker rely on a single commercial device, it should be noted that retinal flicker measurement may be considered less resilient from a commercial perspective than those associated with multiple industry products.

2.3 Summary

There is not an ideal method for empirical measurement of endothelial function. Techniques to measure coronary epicardial and micro-vascular function are well established but they are invasive, time-consuming, and expensive. Several techniques are available for measurement of reactive hyperaemia in peripheral arteries, which provide a less-invasive assessment of endothelial function. FMD of the brachial arteries is the most commonly used, but it is technically demanding and requires a high degree of training and experience to ensure accurate measurements, but semi-automatic, easier to use tools are approaching. Techniques, such as finger plethysmography, are easier to use; however, the utility of newer methods is restricted because of a lack of methodological consensus, lack of reference values in healthy individuals, and limited validation in large clinical trials.

3. Endothelial dysfunction and arterial disease

3.1 Arterial hypertension

Hypertensive patients have impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilatation both in coronary arteries112 and in the forearm113 (see Supplementary material online, Table S1), and data from the Framingham offspring cohort suggest that the degree of endothelial dysfunction is positively associated with the severity of hypertension.114 However, in a cohort of 3500 ethnically diverse persons from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, until now the largest clinical study in the field, impaired FMD was not a significant independent predictor of hypertension development, after adjustment for co-variables.115 A possible explanation for these seemingly disparate observations is that the interaction between EC function and hypertension may vary between populations. This underscores the importance of developing reference FMD values for different populations. It is also plausible that stratification of patients (e.g. using omics/epigenetics data or via analysis of ECFCs or EMVs) may identify sub-groups where FMD values are more accurately coupled to disease risk116 (see Section 4).

3.2 Diabetes

Diabetes is associated with a two- to four-fold increased risk of CVD, mainly attributable to hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, and oxidative stress.117 Endothelium-dependent vasodilation in peripheral118 and coronary119 arteries of patients with T2DM is blunted (see Supplementary material online, Table S2), principally due to loss or reduction of NO.120 The relationship between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction is complex and endothelial dysfunction probably precedes the onset of T2DM. Indeed, polymorphisms of eNOS are multivariable predictors of incidence of T2DM.121 Several mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction are proposed in the setting of DM including: increased oxidative stress,122 uncoupling of eNOS,123 pro-inflammatory activation of EC,124 mitochondrial dysfunction,125 impaired endothelial repair potential,126 and increased permeability.127,128 Although the role of endothelial dysfunction in pathogenesis of micro- and macro-vascular complications is well-documented, endothelium-dependent peripheral vascular tests do not appear to improve risk stratification in patients with T2DM.129,130 However, given the range of endothelial mediators and their multiple mechanisms of action which contribute to endothelial abnormalities, FMD may not represent the most appropriate measure of the early signs of endothelial metabolic disturbances.

3.3 Coronary artery disease

Multiple studies have addressed the hypothesis that endothelial dysfunction may improve risk stratification above well-established risk scores/factors for CAD (see Supplementary material online, Table S3), thereby offering the possibility of early and personalized therapy. Consistent with this concept, peripheral macro-vascular endothelial dysfunction, estimated by FMD91,131,132 or finger plethysmography133 was demonstrated to independently predict major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in several populations at risk for CAD. Moreover, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 35 FMD studies and 6 peripheral arterial tonometry studies found that these tests provided a similar prognostic value in predicting cardiovascular events.134 In contrast, three large prevention trials failed to confirm the predictive value of FMD (macro-vascular endothelial dysfunction), but instead found that markers of micro-vascular endothelial dysfunction (hyperaemic velocity in FATE89 and invasive forearm technique with Ach in PIVUS135) were associated with increased MACE risk and improved risk discrimination substantially, independent of established risk scores. The reason why FMD had prognostic value in some, but not in all populations is uncertain, but could be related to differences in the age and physical activity of the populations that were studied.89,131,132,136 It is also plausible that FMD may predict cardiovascular risk in a proportion of patients but not in others. It follows that integrating FMD measurements with patient-specific genetic and epigenetic characteristics may provide a personalized approach for predicting cardiovascular risk.

3.3.1 Ischaemia and no obstructive CAD

A substantial proportion of patients, especially women with anginal symptoms and myocardial ischaemia, have an absence of flow-limiting obstruction in the epicardial arteries at coronary angiography.137,138 This syndrome has been increasingly recognized and recently termed as Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Artery disease (INOCA) or Angina and No Obstructive Coronary Artery (ANOCA) disease. The pathophysiology of INOCA includes dysfunctionality in coronary macro-vascular (i.e. epicardial coronary arteries) and/or micro-vascular compartment (i.e. small intramural pre-arteriolar coronary arteries). Bairey Merz et al.139 have identified a series of investigations to define INOCA including measurement of endothelial dysfunction. A panel of invasive measurements includes coronary vasomotor testing with intra-coronary adenosine (to measure CFR that estimates endothelium-independent micro-vascular function), Ach (to measure endothelium-dependent coronary vasoreactivity) and nitroglycerin (to measure endothelium-independent macro-vascular function; see Supplementary material online, Table S4). Coronary endothelial dysfunction is defined as micro-vascular, if the change in CBF in response to Ach is <50%, and macro-vascular in case of Ach-induced epicardial vasoconstriction.140 The results of such testing should help to guide therapy in individual patients, for example, to determine whether micro-vascular endothelial dysfunction is involved.

3.3.2 Chronic coronary syndromes and progression to plaque instability

Coronary macro- and micro-vascular endothelial dysfunction can predict acute vascular events independently of conventional CAD risk factors and angiographically proven coronary atherosclerosis. For example, although patients with high-risk coronary anatomy (left main stenosis and three vessels with CAD) were excluded,141 the detection of micro-vascular endothelial dysfunction was associated with a 2.4-fold increase in event rates, while the detection of epicardial endothelial dysfunction was associated with a 1.4-fold elevation of event rates (independently from other risk factors and presence of CAD). These associations point to the importance of coronary endothelial dysfunction for the transition from a stable to unstable form of atherosclerotic disease. Furthermore, peripheral endothelial dysfunction (brachial plethysmography) distinguished subjects at a higher risk for cardiac and total vascular events in populations with documented CAD, highlighting the importance of systemic endothelial changes in plaque progression.142 Atherosclerosis is a focal disease143 and it is therefore noteworthy that coronary segments with a higher degree of endothelial dysfunction are associated with more vulnerable plaque containing a necrotic core (evaluated by IVUS70) suggesting that localized EC dysfunction may predict focal progression into culprit lesions and acute coronary syndromes.

3.3.3 Acute coronary syndromes (STEMI, NSTEMI, and MINOCA)

The pathophysiological mechanism underlying type 2 myocardial infarction (MI) is an acute mismatch between oxygen supply and demand, leading to acute ischaemic myocardial injury.144 Mechanisms include coronary artery spasm and/or coronary micro-vascular dysfunction.144 During the course of atherosclerosis, local inflammation and oxidative stress affect endothelial function and promote plaque vulnerability, with consequent platelet adhesion, vasospasm, stasis, and coronary thrombosis, leading to acute coronary syndrome.145 Importantly, endothelial dysfunction is present not only at the site of the culprit lesion but also in distant, non-culprit coronary arteries, even with normal angiographic appearance.146 Aggravation also occurs in peripheral endothelial dysfunction after acute coronary syndrome and its normalization predicts a lower risk of future events.147 Relatively few studies have correlated endothelial dysfunction with MI with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA) which arises, due to either atherosclerotic plaque disruption and coronary thrombosis (i.e. type 1 MI), or coronary vasospasm (i.e. type 2 MI), along with other possible causes. In the Stockholm Myocardial Infarction with Normal Coronaries (SMINC) study, peripheral micro-vascular endothelial function was normal in MINOCA patients compared to controls.148 Overall, although micro-vascular dysfunction is presumed to be a causal component in ACS, both in type 1 and even more frequently in type 2 MI, there are uncertainties whether it is a contributor or a biomarker of disease risk.

3.4 Summary

There is a wealth of evidence that endothelial dysfunction is a key player in the initiation of atherosclerosis and plaque progression. Endothelial dysfunction in coronary macro- or micro-vascular compartments may predict and/or drive disease progression into culprit lesions, acute coronary syndromes, and INOCA. Consistent with this, endothelial dysfunction has been demonstrated in asymptomatic individuals with risk factors for atherosclerosis (i.e. before clinical manifestation of the diseases) and, large clinical trials demonstrated that micro-vascular endothelial dysfunction can independently predict MACE in populations at risk for CAD. However, there are several examples in the literature where the correlation between EC dysfunction and disease risk varies considerably between studies. This can be partly attributed to technical considerations, thereby underlying the importance of methodological consistency, but may also be related to biological factors that vary between individuals and/or between populations therefore requiring a precision medicine approach.

4. Endothelial function in precision medicine

4.1 Can endothelial function measurements be used to stratify patients for therapy?

Results from most clinical trials have documented that despite the successful control of cardiovascular risk factors achieved with cardiovascular drugs, the impact on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality reduction is limited (∼20–45%). Consequently, tools that might enable identification of those patients who develop future events, despite optimal treatment are urgently needed. Several findings support the possibility that endothelial function could be used to identify patients that remain at high cardiovascular risk. For example, among 251 Japanese men with newly diagnosed stable CAD and concurrent impaired brachial artery FMD, those whose endothelial function did not improve after 6 months of optimized pharmacological treatment showed a significant higher event rate of cardiovascular events (26%) in the 31 months follow-up compared to those with improved endothelial function (10%).149 On the other hand, EC function can also identify patients with favourable responses to lifestyle changes, such as increased exercise, or pharmacological interventions. For example, moderate aerobic physical exercise can improve endothelium-dependent vasodilation, not only in healthy middle-aged men150 but also in patients with arterial hypertension,151 CAD,152 and chronic heart failure.153 Endothelial function has also been improved by weight reduction either by diet154,155 or bariatric surgery,156 dietary interventions with foods rich in polyphenols (fruits, green tea, and cocoa)157,158 as well as smoking cessation.159 Beyond lifestyle interventions, the first finding that EC function measurements can be used to monitor pharmacological responses was obtained from controlled studies with statins.160,161 The mechanism is likely related to the documented anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of statins that result in improved availability of vascular NO.162 Endothelial function can also be used to monitor responses to other drugs with an effect on cardiovascular risk factors163 and some diabetes modulating drugs such as metformin164 or glitazones.164–166

4.2 Integrating endothelial functional measurements with biomarkers of vascular function

Genetic and epigenetic differences contribute to variation in endothelial function both in healthy individuals and in patients with CVD. Therefore, the ability to delineate patients at high cardiovascular risk and identify responders and non-responders to therapy can potentially be enhanced by integrating endothelial function measurements with genomic and epigenomic datasets. Non-coding RNAs are epigenetic markers of potential clinical use due to their high plasma stability and advances in experimental techniques used in their assessment. For example, the detection of specific circular RNAs and microRNAs in plasma has been linked to CAD and ACS167 and Sapp et al.168 found that alterations in miR-126-5p correlated with endothelial function in response to exercise in healthy individuals. There may also be value in quantitation of classical markers such as sICAM, sVCAM, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, hsCRP, and NO for integration with endothelial function assessment. There is also considerable interest in using circulating EMVs and ECFCs as a surrogate of endothelial health.169 For example, anti-inflammatory treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus simultaneously improved endothelial function and reduced EMV levels170 suggesting that EMV levels may report on vascular function. Of particular note, a recent study from Zacharia et al.171 found that endothelial function correlated with circulating micro-vesicles in patients with ACS. Moreover, studies of circulating ECFCs revealed that they correlate with enhanced micro-vascular function and repair in patients with acute MI.172,173 These tools will significantly contribute to the field of precision medicine and identify patients at high risk of developing both micro- and macro-vascular complications.174

4.3 Summary

Measurement of endothelial function can be used to monitor responses to lifestyle changes and pharmacological intervention, and can identify patients that remain at residual risk despite optimal therapy. The prognostic value of endothelial function measurement may be enhanced by integration with patient-specific information from omics and epigenetic studies and/or from analysis of the physiology of EMVs and ECFCs. These data may be combined through an algorithm that will enhance risk stratification and improve patient management.175,176

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Consensus statements

Endothelial dysfunction does not describe a single endothelial phenotype but is characterized by a spectrum of phenotypic states, exemplified by multiple EC subsets and plasticity in atherosclerosis. The vascular biology community should delineate the contribution of various EC dysfunctional states to CVD and develop new technologies to measure pathogenic EC subsets in the clinic.

FMD of the brachial arteries, the most commonly used measure of endothelial function, predicted cardiovascular risk in some large clinical trials but not others. Thus, we recommend that a consensus, semi-automated methodology is adopted in future studies to minimize technical variation, and that reference FMD values are established for different populations.

Newer techniques to measure endothelial dysfunction that are relatively easy to perform, such as finger plethysmography and the retinal flicker test, have the potential for increased clinical use provided a consensus is achieved on the measurement protocol used. In addition, larger clinical studies are needed to establish reference values and to assess their clinical utility.

Future work should determine whether the prognostic value of endothelial function measurement can be enhanced by integration with patient-specific information from omics and epigenetic studies and/or from analysis of patient-derived EMVs and ECFCs.

Writing Process

This Position Paper was written by the following ESC Working Groups: Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology, Aorta and Peripheral Vascular Diseases, Coronary Pathophysiology and Microcirculation, and Thrombosis. This topic was discussed at an ESC-sponsored session entitled ‘Endothelial Cell Dysfunction’ held at the European Vascular Biology Organisation meeting in 2016 (Maastricht, The Netherlands) which was Chaired by Prof. Paul Evans (Sheffield, UK) and Prof. Marie-Luce Bochaton-Piallat (Geneva, Switzerland). This session included talks from Prof. Arno Schmidt-Trucksäss (Basel, Switzerland), Dr Rosa Suades Soler (Karolinska Institutet, Sweden), Prof. Danijela Trifunovic (Belgrade, Serbia), Prof.Michael Shechter (Tel Aviv, Israel), Dr Elena Osto (Zürich, Switzerland) and Prof. Yvonne Alexander (Manchester, UK). It was followed by a writing meeting attended by the Chairs, speakers and Prof Dirk Duncker (Rotterdam, The Netherlands). Other worldwide experts in the field of endothelial function testing were subsequently recruited to the writing process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Anne Jomard, MSc, from the Institute of Clinical Chemistry, University and University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland for excellent support with text and image editing.

Conflict of interest: V.A. has received funding from Amgen, Bayer, Sanofi, Novartis, NovoNordisk, BMS, and Pfizer. M.S. is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board, Itamar Medical Inc., Israel. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation (Grant No. 20180571) awarded to M.B.; the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Competitiveness and Science -SAF2016-76819-R and Carlos III Institute of Health grants TERCEL—RD16/0011/0018 and CIBERCV awarded to L.B.; the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant No. 310030_185370/1) awarded to M.-L.B.-P.; the Swedish Research Council (VR 2016-02706) Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation (20170717) and Konung Gustav: Vs och Drottning Victorias Frimurarestiftelse awarded to F.C.; a grant from The Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative (CVON2014-11), an initiative with financial support from the Dutch Heart Foundation awarded to D.J.D.; grants from the British Heart Foundation awarded to P.C.E. and P.D.M.; a Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Career Development Fellowship to P.D.M. (214567/Z/18/Z); grants from National Institutes of Health Grants R35 HL140016 and Program Project Grant P01 HL129941 awarded to D.G.H.; grants from Fondazione Cariplo 2016-0852, Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research PRIN 2017K55HLC, European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD) and Fondazione Telethon GGP19146 awarded to G.D.N.; grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation Prima and Sinergia Grant (PR00P3_179861/1 and CRSII5_180317/1), the Swiss Card-Onco-Grant—Alfred and Annemarie von Sick Grant, the Hartmann Müller—Foundation and Jubilaeumsstiftung von SwissLife awarded to E.O.; a grant from the European Society of Cardiology Research Grant awarded to R.S.; a grant (PGC2018-094025-B-I00) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and funds FEDER ‘Una Manera de Hacer Europa’ awarded to G.V.; grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), SFB1123-A1/10/B4 and Excellence Cluster SyNergy; and by the European Research Council (ERC AdG No. 692511 awarded to C.W. and ERC CoG No. 726318-InflammaTENSION awarded to T.J.G.) and ERA-Net-CVD (PLAQUEFIGHT) 01KL1808 awarded to T.J.G.

References

- 1. Kalucka J, Bierhansl L, Conchinha NV, Missiaen R, Elia I, Bruning U, Scheinok S, Treps L, Cantelmo AR, Dubois C, de Zeeuw P, Goveia J, Zecchin A, Taverna F, Morales-Rodriguez F, Brajic A, Conradi LC, Schoors S, Harjes U, Vriens K, Pilz GA, Chen R, Cubbon R, Thienpont B, Cruys B, Wong BW, Ghesquiere B, Dewerchin M, De Bock K, Sagaert X, Jessberger S, Jones EAV, Gallez B, Lambrechts D, Mazzone M, Eelen G, Li X, Fendt SM, Carmeliet P.. Quiescent endothelial cells upregulate fatty acid beta-oxidation for vasculoprotection via redox homeostasis. Cell Metab 2018;28:881–894.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shah AV, Birdsey GM, Peghaire C, Pitulescu ME, Dufton NP, Yang Y, Weinberg I, Osuna Almagro L, Payne L, Mason JC, Gerhardt H, Adams RH, Randi AM.. The endothelial transcription factor ERG mediates angiopoietin-1-dependent control of Notch signalling and vascular stability. Nat Commun 2017;8:16002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cardner M, Yalcinkaya M, Goetze S, Luca E, Balaz M, Hunjadi M, Hartung J, Shemet A, Kränkel N, Radosavljevic S, Keel M, Othman A, Karsai G, Hornemann T, Claassen M, Liebisch G, Carreira E, Ritsch A, Landmesser U, Krützfeldt J, Wolfrum C, Wollscheid B, Beerenwinkel N, Rohrer L, von Eckardstein A.. Structure-function relationships of HDL in diabetes and coronary heart disease. JCI Insight 2020;5:e131491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li X, Sun X, Carmeliet P.. Hallmarks of endothelial cell metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab 2019;30:414–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dikalov S, Itani H, Richmond B, Arslanbaeva L, Vergeade A, Rahman SMJ, Boutaud O, Blackwell T, Massion PP, Harrison DG, Dikalova A.. Tobacco smoking induces cardiovascular mitochondrial oxidative stress, promotes endothelial dysfunction, and enhances hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2019;316:H639–H646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miao H, Hu YL, Shiu YT, Yuan S, Zhao Y, Kaunas R, Wang Y, Jin G, Usami S, Chien S.. Effects of flow patterns on the localization and expression of VE-cadherin at vascular endothelial cell junctions: in vivo and in vitro investigations. J Vasc Res 2005;42:77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Souilhol C, Serbanovic-Canic J, Fragiadaki M, Chico TJ, Ridger V, Roddie H, Evans PC.. Endothelial responses to shear stress in atherosclerosis: a novel role for developmental genes. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17:52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thoumine O, Nerem RM, Girard PR.. Oscillatory shear stress and hydrostatic pressure modulate cell-matrix attachment proteins in cultured endothelial cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 1995;31:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cai H, Harrison DG.. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res 2000;87:840–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hunt BJ, Jurd KM.. Endothelial cell activation. A central pathophysiological process. BMJ 1998;316:1328–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen P-Y, Qin L, Li G, Wang Z, Dahlman JE, Malagon-Lopez J, Gujja S, Cilfone NA, Kauffman KJ, Sun L, Sun H, Zhang X, Aryal B, Canfran-Duque A, Liu R, Kusters P, Sehgal A, Jiao Y, Anderson DG, Gulcher J, Fernandez-Hernando C, Lutgens E, Schwartz MA, Pober JS, Chittenden TW, Tellides G, Simons M.. Endothelial TGF-β signalling drives vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Nat Metab 2019;1:912–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kalluri AS, Vellarikkal SK, Edelman ER, Nguyen L, Subramanian A, Ellinor PT, Regev A, Kathiresan S, Gupta RM.. Single-cell analysis of the normal mouse aorta reveals functionally distinct endothelial cell populations. Circulation 2019;140:147–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li Z, Solomonidis EG, Meloni M, Taylor RS, Duffin R, Dobie R, Magalhaes MS, Henderson BEP, Louwe PA, D’Amico G, Hodivala-Dilke KM, Shah AM, Mills NL, Simons BD, Gray GA, Henderson NC, Baker AH, Brittan M.. Single-cell transcriptome analyses reveal novel targets modulating cardiac neovascularization by resident endothelial cells following myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2507–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lukowski SW, Patel J, Andersen SB, Sim SL, Wong HY, Tay J, Winkler I, Powell JE, Khosrotehrani K.. Single-cell transcriptional profiling of aortic endothelium identifies a hierarchy from endovascular progenitors to differentiated cells. Cell Rep 2019;27:2748–2758.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Palmer RM, Ashton DS, Moncada S.. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine. Nature 1988;333:664–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shimokawa H, Godo S.. Nitric oxide and endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization mediated by hydrogen peroxide in health and disease. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tousoulis D, Kampoli AM, Tentolouris C, Papageorgiou N, Stefanadis C.. The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2012;10:4–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kojda G, Cheng YC, Burchfield J, Harrison DG.. Dysfunctional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression in response to exercise in mice lacking one eNOS gene. Circulation 2001;103:2839–2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ.. Endothelial function and dysfunction: testing and clinical relevance. Circulation 2007;115:1285–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guzik TJ, West NEJ, Black E, McDonald D, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Channon KM.. Vascular superoxide production by NAD(P)H oxidase – association with endothelial dysfunction and clinical risk factors. Circ Res 2000;86:E85–E90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guzik TJ, Chen W, Gongora MC, Guzik B, Lob HE, Mangalat D, Hoch N, Dikalov S, Rudzinski P, Kapelak B, Sadowski J, Harrison DG.. Calcium-dependent NOX5 nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase contributes to vascular oxidative stress in human coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1803–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guzik TJ, Mussa S, Gastaldi D, Sadowski J, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Channon KM.. Mechanisms of increased vascular superoxide production in human diabetes mellitus role of NAD(P)H oxidase and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 2002;105:1656–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guzik TJ, Sadowski J, Guzik B, Jopek A, Kapelak B, Przybyłowski P, Wierzbicki K, Korbut R, Harrison DG, Channon KM.. Coronary artery superoxide production and nox isoform expression in human coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006;26:333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, McCann L, Fukai T, Holland SM, Mitch WE, Harrison DG.. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest 2003;111:1201–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ruan CH, So SP, Ruan KH.. Inducible COX-2 dominates over COX-1 in prostacyclin biosynthesis: mechanisms of COX-2 inhibitor risk to heart disease. Life Sci 2011;88:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mundi S, Massaro M, Scoditti E, Carluccio MA, van Hinsbergh VWM, Iruela-Arispe ML, De Caterina R.. Endothelial permeability, LDL deposition, and cardiovascular risk factors-a review. Cardiovasc Res 2018;114:35–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caplan BA, Gerrity RG, Schwartz CJ.. Endothelial cell morphology in focal areas of in vivo Evans blue uptake in the young pig aorta. I. Quantitative light microscopic findings. Exp Mol Pathol 1974;21:102–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Jager SCA, Meeuwsen JAL, van Pijpen FM, Zoet GA, Barendrecht AD, Franx A, Pasterkamp G, van Rijn BB, Goumans MJ, den Ruijter HM.. Preeclampsia and coronary plaque erosion: manifestations of endothelial dysfunction resulting in cardiovascular events in women. Eur J Pharmacol 2017;816:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dewey CF Jr, Bussolari SR, Gimbrone MA Jr, Davies PF.. The dynamic response of vascular endothelial cells to fluid shear stress. J Biomech Eng 1981;103:177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gerrity RG, Richardson M, Caplan BA, Cade JF, Hirsh J, Schwartz CJ.. Endotoxin-induced vascular endothelial injury and repair. II. Focal injury, en face morphology, (3H)thymidine uptake and circulating endothelial cells in the dog. Exp Mol Pathol 1976;24:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Norata GD, Grigore L, Raselli S, Redaelli L, Hamsten A, Maggi F, Eriksson P, Catapano AL.. Post-prandial endothelial dysfunction in hypertriglyceridemic subjects: molecular mechanisms and gene expression studies. Atherosclerosis 2007;193:321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Norata GD, Grigore L, Raselli S, Seccomandi PM, Hamsten A, Maggi FM, Eriksson P, Catapano AL.. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins from hypertriglyceridemic subjects induce a pro-inflammatory response in the endothelium: molecular mechanisms and gene expression studies. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2006;40:484–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reynolds J, Ray D, Alexander MY, Bruce I.. Role of vitamin D in endothelial function and endothelial repair in clinically stable systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet 2015;385:S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reynolds JA, Ray DW, Zeef LAH, O’Neill T, Bruce IN, Alexander MY.. The effect of type 1 IFN on human aortic endothelial cell function in vitro: relevance to systemic lupus erythematosus. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2014;34:404–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chong M, Sjaarda J, Pigeyre M, Mohammadi-Shemirani P, Lali R, Shoamanesh A, Gerstein HC, Paré G.. Novel drug targets for ischemic stroke identified through Mendelian randomization analysis of the blood proteome. Circulation 2019;140:819–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li M, Kwok MK, Fong SSM, Schooling CM.. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and ischemic heart disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep 2019;9:8491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Caruso P, Dunmore BJ, Schlosser K, Schoors S, Dos Santos C, Perez-Iratxeta C, Lavoie JR, Zhang H, Long L, Flockton AR, Frid MG, Upton PD, D’Alessandro A, Hadinnapola C, Kiskin FN, Taha M, Hurst LA, Ormiston ML, Hata A, Stenmark KR, Carmeliet P, Stewart DJ, Morrell NW.. Identification of microRNA-124 as a major regulator of enhanced endothelial cell glycolysis in pulmonary arterial hypertension via PTBP1 (polypyrimidine tract binding protein) and pyruvate kinase M2. Circulation 2017;136:2451–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dejana E, Hirschi KK, Simons M.. The molecular basis of endothelial cell plasticity. Nat Commun 2017;8:14361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kovacic JC, Dimmeler S, Harvey RP, Finkel T, Aikawa E, Krenning G, Baker AH.. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition in cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:190–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Souilhol C, Harmsen MC, Evans PC, Krenning G.. Endothelial-mesenchymal transition in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 2018;114:565–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen P-Y, Qin L, Baeyens N, Li G, Afolabi T, Budatha M, Tellides G, Schwartz MA, Simons M.. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition drives atherosclerosis progression. J Clin Invest 2015;125:4514–4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Evrard SM, Lecce L, Michelis KC, Nomura-Kitabayashi A, Pandey G, Purushothaman KR, d’Escamard V, Li JR, Hadri L, Fujitani K, Moreno PR, Benard L, Rimmele P, Cohain A, Mecham B, Randolph GJ, Nabel EG, Hajjar R, Fuster V, Boehm M, Kovacic JC.. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition is common in atherosclerotic lesions and is associated with plaque instability. Nat Commun 2016;7:11853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mahmoud MM, Serbanovic-Canic J, Feng S, Souilhol C, Xing RY, Hsiao S, Mammoto A, Chen J, Ariaans M, Francis SE, Van der Heiden K, Ridger V, Evans PC.. Shear stress induces endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via the transcription factor Snail. Sci Rep 2017;7:3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moonen J-R, Lee ES, Schmidt M, Maleszewska M, Koerts JA, Brouwer LA, Van Kooten TG, van Luyn MJA, Zeebregts CJ, Krenning G, Harmsen MC.. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to fibro-proliferative vascular disease and is modulated by fluid shear stress. Cardiovasc Res 2015;108:377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shi Y, Vanhoutte PM.. Macro- and microvascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. J Diabetes 2017;9:434–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guzik TJ, Sadowski J, Kapelak B, Jopek A, Rudzinski P, Pillai R, Korbut R, Channon KM.. Systemic regulation of vascular NAD(P)H oxidase activity and nox isoform expression in human arteries and veins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:1614–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fadini GP, Mehta A, Dhindsa DS, Bonora BM, Sreejit G, Nagareddy P, Quyyumi AA.. Circulating stem cells and cardiovascular outcomes: from basic science to the clinic. Eur Heart J 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Medina RJ, Barber CL, Sabatier F, Dignat-George F, Melero-Martin JM, Khosrotehrani K, Ohneda O, Randi AM, Chan JKY, Yamaguchi T, Van Hinsbergh VWM, Yoder MC, Stitt AW.. Endothelial progenitors: a consensus statement on nomenclature. Stem Cells Transl Med 2017;6:1316–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sluijter JPG, Davidson SM, Boulanger CM, Buzas EI, de Kleijn DPV, Engel FB, Giricz Z, Hausenloy DJ, Kishore R, Lecour S, Leor J, Madonna R, Perrino C, Prunier F, Sahoo S, Schiffelers RM, Schulz R, Van Laake LW, Ytrehus K, Ferdinandy P.. Extracellular vesicles in diagnostics and therapy of the ischaemic heart: Position Paper from the Working Group on Cellular Biology of the Heart of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Res 2018;114:19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flammer AJ, Anderson T, Celermajer DS, Creager MA, Deanfield J, Ganz P, Hamburg NM, Luscher TF, Shechter M, Taddei S, Vita JA, Lerman A.. The assessment of endothelial function: from research into clinical practice. Circulation 2012;126:753–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Premer C, Kanelidis AJ, Hare JM, Schulman IH.. Rethinking endothelial dysfunction as a crucial target in fighting heart failure. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2019;3:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. SchäChinger V, Britten MB, Zeiher AM.. Prognostic impact of coronary vasodilator dysfunction on adverse long-term outcome of coronary heart disease. Circulation 2000;101:1899–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hlatky MA, Greenland P, Arnett DK, Ballantyne CM, Criqui MH, Elkind MSV, Go AS, Harrell FE, Hong Y, Howard BV, Howard VJ, Hsue PY, Kramer CM, McConnell JP, Normand S-LT, O’Donnell CJ, Smith SC, Wilson PWF; American Heart Association Expert Panel on Subclinical Atherosclerotic Diseases and Emerging Risk Factors and the Stroke Council. Criteria for evaluation of novel markers of cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009;119:2408–2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Aboyans V, Brodmann M, Cífková R, Cosentino F, De Carlo M, Gallino A, Landmesser U, Laurent S, Lekakis J, Mikhailidis DP, Naka KK, Protogerou AD, Rizzoni D, Schmidt-Trucksäss A, Van Bortel L, Weber T, Yamashina A, Zimlichman R, Boutouyrie P, Cockcroft J, O’Rourke M, Park JB, Schillaci G, Sillesen H, Townsend RR.. The role of vascular biomarkers for primary and secondary prevention. A position paper from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripheral circulation: endorsed by the Association for Research into Arterial Structure and Physiology (ARTERY) Society. Atherosclerosis 2015;241:507–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Flammer AJ, Luscher TF.. Human endothelial dysfunction: EDRFs. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol 2010;459:1005–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ludmer PL, Selwyn AP, Shook TL, Wayne RR, Mudge GH, Alexander RW, Ganz P.. Paradoxical vasoconstriction induced by acetylcholine in atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med 1986;315:1046–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Puri R, Liew GY, Nicholls SJ, Nelson AJ, Leong DP, Carbone A, Copus B, Wong DT, Beltrame JF, Worthley SG, Worthley MI.. Coronary beta2-adrenoreceptors mediate endothelium-dependent vasoreactivity in humans: novel insights from an in vivo intravascular ultrasound study. Eur Heart J 2012;33:495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cox DA, Vita JA, Treasure CB, Fish RD, Alexander RW, Ganz P, Selwyn AP.. Atherosclerosis impairs flow-mediated dilation of coronary arteries in humans. Circulation 1989;80:458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nabel EG, Selwyn AP, Ganz P.. Large coronary arteries in humans are responsive to changing blood flow: an endothelium-dependent mechanism that fails in patients with atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;16:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Beltrame JF, Crea F, Camici P.. Advances in coronary microvascular dysfunction. Heart Lung Circ 2009;18:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Camici PG, Crea F.. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2007;356:830–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schindler TH, Schelbert HR, Quercioli A, Dilsizian V.. Cardiac PET imaging for the detection and monitoring of coronary artery disease and microvascular health. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;3:623–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Leung DY, Leung M.. Non-invasive/invasive imaging: significance and assessment of coronary microvascular dysfunction. Heart 2011;97:587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Utz W, Jordan J, Niendorf T, Stoffels M, Luft FC, Dietz R, Friedrich MG.. Blood oxygen level-dependent MRI of tissue oxygenation: relation to endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent blood flow changes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:1408–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Anderson TJ, Uehata A, Gerhard MD, Meredith IT, Knab S, Delagrange D, Lieberman EH, Ganz P, Creager MA, Yeung AC, Selwyn AP.. Close relation of endothelial function in the human coronary and peripheral circulations. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26:1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bonetti PO, Pumper GM, Higano ST, Holmes DR Jr, Kuvin JT, Lerman A.. Noninvasive identification of patients with early coronary atherosclerosis by assessment of digital reactive hyperemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:2137–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Takase B, Uehata A, Akima T, Nagai T, Nishioka T, Hamabe A, Satomura K, Ohsuzu F, Kurita A.. Endothelium-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation in coronary and brachial arteries in suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:1535–1539, A7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH.. Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling: molecular, cellular, and vascular behavior. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:2379–2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gimbrone MA, Topper JN, Nagel T, Anderson KR, Garcia-Cardeña G.. Endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic forces, and atherogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;902:230–239; discussion 239–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lavi S, Bae JH, Rihal CS, Prasad A, Barsness GW, Lennon RJ, Holmes DR Jr, Kuvin JT, Lerman DR. Segmental coronary endothelial dysfunction in patients with minimal atherosclerosis is associated with necrotic core plaques. Heart 2009;95:1525–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Linder L, Kiowski W, Buhler FR, Luscher TF.. Indirect evidence for release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor in human forearm circulation in vivo. Blunted response in essential hypertension. Circulation 1990;81:1762–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Petrie JR, Ueda S, Morris AD, Murray LS, Elliott HL, Connell JM.. How reproducible is bilateral forearm plethysmography? Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998;45:131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Miller OI, Sullivan ID, Lloyd JK, Deanfield JE.. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet 1992;340:1111–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Joannides R, Haefeli WE, Linder L, Richard V, Bakkali EH, Thuillez C, LüScher TF.. Nitric oxide is responsible for flow-dependent dilatation of human peripheral conduit arteries in vivo. Circulation 1995;91:1314–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Joannides R, Richard V, Haefeli WE, Linder L, LüScher TF, Thuillez C.. Role of basal and stimulated release of nitric oxide in the regulation of radial artery caliber in humans. Hypertension 1995;26:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lieberman EH, Gerhard MD, Uehata A, Selwyn AP, Ganz P, Yeung AC, Creager MA.. Flow-induced vasodilation of the human brachial artery is impaired in patients <40 years of age with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1996;78:1210–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Parker BA, Tschakovsky ME, Augeri AL, Polk DM, Thompson PD, Kiernan FJ.. Heterogenous vasodilator pathways underlie flow-mediated dilation in men and women. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011;301:H1118–H1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Charakida M, Masi S, Luscher TF, Kastelein JJ, Deanfield JE.. Assessment of atherosclerosis: the role of flow-mediated dilatation. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2854–2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, Creager MA, Deanfield J, Drexler H, Gerhard-Herman M, Herrington D, Vallance P, Vita J, Vogel R; International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Deanfield J, Donald A, Ferri C, Giannattasio C, Halcox J, Halligan S, Lerman A, Mancia G, Oliver JJ, Pessina AC, Rizzoni D, Rossi GP, Salvetti A, Schiffrin EL, Taddei S, Webb DJ; Working Group on Endothelin and Endothelial Factors of the European Society of Hypertension. Endothelial function and dysfunction. Part I: methodological issues for assessment in the different vascular beds: a statement by the Working Group on Endothelin and Endothelial Factors of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens 2005;23:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Thijssen DHJ, Bruno RM, van Mil A, Holder SM, Faita F, Greyling A, Zock PL, Taddei S, Deanfield JE, Luscher T, Green DJ, Ghiadoni L.. Expert consensus and evidence-based recommendations for the assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2534–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Harris RA, Nishiyama SK, Wray DW, Richardson RS.. Ultrasound assessment of flow-mediated dilation. Hypertension 2010;55:1075–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Thijssen DH, Black MA, Pyke KE, Padilla J, Atkinson G, Harris RA, Parker B, Widlansky ME, Tschakovsky ME, Green DJ.. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: a methodological and physiological guideline. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011;300:H2–H12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Donald AE, Halcox JP, Charakida M, Storry C, Wallace SM, Cole TJ, Friberg P, Deanfield JE.. Methodological approaches to optimize reproducibility and power in clinical studies of flow-mediated dilation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1959–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tomiyama H, Kohro T, Higashi Y, Takase B, Suzuki T, Ishizu T, Ueda S, Yamazaki T, Furumoto T, Kario K, Inoue T, Koba S, Watanabe K, Takemoto Y, Hano T, Sata M, Ishibashi Y, Node K, Maemura K, Ohya Y, Furukawa T, Ito H, Ikeda H, Yamashina A.. Reliability of measurement of endothelial function across multiple institutions and establishment of reference values in Japanese. Atherosclerosis 2015;242:433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mitchell GF, Parise H, Vita JA, Larson MG, Warner E, Keaney JF Jr, Keyes MJ, Levy D, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ.. Local shear stress and brachial artery flow-mediated dilation: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 2004;44:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mitchell GF, Vita JA, Larson MG, Parise H, Keyes MJ, Warner E, Vasan RS, Levy D, Benjamin EJ.. Cross-sectional relations of peripheral microvascular function, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and aortic stiffness: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2005;112:3722–3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Philpott AC, Lonn E, Title LM, Verma S, Buithieu J, Charbonneau F, Anderson TJ.. Comparison of new measures of vascular function to flow mediated dilatation as a measure of cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Cardiol 2009;103:1610–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Anderson TJ, Charbonneau F, Title LM, Buithieu J, Rose MS, Conradson H, Hildebrand K, Fung M, Verma S, Lonn EM.. Microvascular function predicts cardiovascular events in primary prevention: long-term results from the Firefighters and Their Endothelium (FATE) study. Circulation 2011;123:163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Huang AL, Silver AE, Shvenke E, Schopfer DW, Jahangir E, Titas MA, Shpilman A, Menzoian JO, Watkins MT, Raffetto JD, Gibbons G, Woodson J, Shaw PM, Dhadly M, Eberhardt RT, Keaney JF Jr, Gokce N, Vita JA.. Predictive value of reactive hyperemia for cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral arterial disease undergoing vascular surgery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007;27:2113–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yeboah J, Crouse JR, Hsu FC, Burke GL, Herrington DM.. Brachial flow-mediated dilation predicts incident cardiovascular events in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 2007;115:2390–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yeboah J, Folsom AR, Burke GL, Johnson C, Polak JF, Post W, Lima JA, Crouse JR, Herrington DM.. Predictive value of brachial flow-mediated dilation for incident cardiovascular events in a population-based study: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation 2009;120:502–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kusche-Vihrog K, Callies C, Fels J, Oberleithner H.. The epithelial sodium channel (ENaC): mediator of the aldosterone response in the vascular endothelium? Steroids 2010;75:544–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kuvin JT, Patel AR, Sliney KA, Pandian NG, Sheffy J, Schnall RP, Karas RH, Udelson JE.. Assessment of peripheral vascular endothelial function with finger arterial pulse wave amplitude. Am Heart J 2003;146:168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Nohria A, Gerhard-Herman M, Creager MA, Hurley S, Mitra D, Ganz P.. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of digital pulse volume amplitude in humans. J Appl Physiol 2006;101:545–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Rubinshtein R, Kuvin JT, Soffler M, Lennon RJ, Lavi S, Nelson RE, Pumper GM, Lerman LO, Lerman A.. Assessment of endothelial function by non-invasive peripheral arterial tonometry predicts late cardiovascular adverse events. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1142–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hamburg NM, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Schnabel R, Pryde MM, Mitchell GF, Sheffy J, Vita JA, Benjamin EJ.. Cross-sectional relations of digital vascular function to cardiovascular risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117:2467–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hamburg NM, Palmisano J, Larson MG, Sullivan LM, Lehman BT, Vasan RS, Levy D, Mitchell GF, Vita JA, Benjamin EJ.. Relation of brachial and digital measures of vascular function in the community: the Framingham Heart study. Hypertension 2011;57:390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Schnabel RB, Schulz A, Wild PS, Sinning CR, Wilde S, Eleftheriadis M, Herkenhoff S, Zeller T, Lubos E, Lackner KJ, Warnholtz A, Gori T, Blankenberg S, Munzel T.. Noninvasive vascular function measurement in the community: cross-sectional relations and comparison of methods. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Newman EA. Functional hyperemia and mechanisms of neurovascular coupling in the retinal vasculature. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:1685–1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kondo M, Wang L, Bill A.. The role of nitric oxide in hyperaemic response to flicker in the retina and optic nerve in cats. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2009;75:232–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Houben A, Martens RJH, Stehouwer C.. Assessing microvascular function in humans from a chronic disease perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28:3461–3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sharifizad M, Witkowska KJ, Aschinger GC, Sapeta S, Rauch A, Schmidl D, Werkmeister RM, Garhofer G, Schmetterer L.. Factors determining flicker-induced retinal vasodilation in healthy subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:3306–3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kotliar KE, Lanzl IM, Schmidt-Trucksass A, Sitnikova D, Ali M, Blume K, Halle M, Hanssen H.. Dynamic retinal vessel response to flicker in obesity: a methodological approach. Microvasc Res 2011;81:123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Seshadri S, Ekart A, Gherghel D.. Ageing effect on flicker-induced diameter changes in retinal microvessels of healthy individuals. Acta Ophthalmol 2016;94:e35–e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Patel SR, Bellary S, Karimzad S, Gherghel D.. Overweight status is associated with extensive signs of microvascular dysfunction and cardiovascular risk. Sci Rep 2016;6:32282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Günthner R, Hanssen H, Hauser C, Angermann S, Lorenz G, Kemmner S, Matschkal J, Braunisch MC, Küchle C, Renders L, Moog P, Wassertheurer S, Baumann M, Hammes H-P, Mayer CC, Haller B, Stryeck S, Madl T, Carbajo-Lozoya J, Heemann U, Kotliar K, Schmaderer C.. Impaired retinal vessel dilation predicts mortality in end-stage renal disease. Circ Res 2019;124:1796–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Nguyen TT, Kawasaki R, Wang JJ, Kreis AJ, Shaw J, Vilser W, Wong TY.. Flicker light-induced retinal vasodilation in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2009;32:2075–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Sorensen BM, Houben AJ, Berendschot TT, Schouten JS, Kroon AA, van der Kallen CJ, Henry RM, Koster A, Sep SJ, Dagnelie PC, Schaper NC, Schram MT, Stehouwer CD.. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes are associated with generalized microvascular dysfunction: the Maastricht study. Circulation 2016;134:1339–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]