Abstract

Introduction

Evidence specific for stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence is still lacking at present, and acupuncture may relieve the symptoms. We plan to conduct this multi-centre, three-armed, randomised controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of electroacupuncture among women with stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence.

Methods and analysis

The trial will be conducted at five hospitals in China. Two hundred thirty-two eligible women will be randomly assigned (2:1:1) to the electroacupuncture, sham electroacupuncture or waiting-list group to receive either 24-session acupuncture/sham acupuncture treatment over 8 weeks and 24-week follow-up or 20-week watchful waiting. The primary outcome is the proportion of participants with at least 50% reduction in mean 24-hour stress incontinence episode frequencies from baseline to week 8. The outcome will be analysed with the intention to treatpopulation (defined as participants randomised) with a two-sided p value of less than 0.05 considered significant.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by Guang’anmen Hospital Institutional Review Board (2019-241-KY). Detailed information of the trial will be informed to the participants, and written informed consent will be obtained from every participant. Results of the trial are expected to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov Registry (NCT04299932).

Keywords: urinary incontinences, bladder disorders, complementary medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first randomised controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of acupuncture on stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence.

Sham control and waiting-list control are designed to eliminate the influence of placebo effects and the disease’s natural course on the results.

Minimal electroacupuncture serves as a sham control to blind participants in the electroacupuncture and sham electroacupuncture groups.

One limitation is that acupuncturists and participants in the waiting-list group cannot be blinded.

Introduction

Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) is a complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with both physical exertion and urgency.1 It presents with more severe symptoms in comparison with pure urinary incontinence (UI) and thus puts greater burden on health of individuals and economy of the society.2 Approximately 21%–33% of females in the world3 and 9.4% of females in China4 are troubled with MUI, while less than 50% of such population reports it to doctors and receives treatment.5

Stress-predominant MUI constitutes mainly of stress component. It features leakage on increased abdominal pressure, which can be induced by exertion, sneeze, cough, etc. Despite the existence of leakage with urgency, stress incontinence episode frequencies (IEFs) outnumber 50% of total IEFs.6

Current European Association of Urology (EAU) guideline on incontinence recommends to initiate treatment for predominant component of MUI.7 However, no strong evidence supports that the interventions for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) are as effective when used to treat stress-predominant MUI.6 The effects of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), first-line therapy for pure SUI, decrease among MUI patients.8 About half of patients practising PFMT will seek help from surgery eventually in long-term follow-up,9 and surgery might be more useful than PFMT for moderate to severe symptoms.10 When surgery is considered for MUI, other therapies might need to be combined with to control the urgency component.11 In addition, the existence of urgency symptoms might be aggravated after surgery12 and even reduce the success rate of stress incontinence operation.13 Therefore, it is necessary to seek for interventions specific for stress-predominant MUI.

Previous studies indicate acupuncture may relieve the incontinence symptoms.14 15 It is proven effective in reducing leakage amount of pure SUI14 and total IEFs of MUI.15 Further analysis of the two trials suggests electroacupuncture (EA) might relieve the symptoms of stress-related UI.16 Since the two trials didn’t focus on stress-predominant MUI specifically, this multi-centre, three-armed, randomised controlled is designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of EA among participants with stress-predominant MUI.

Hypotheses

Our primary hypothesis is that the effects of EA are superior to sham electroacupuncture (SA) and waiting-list (WL) in improving proportion of stress-predominant MUI participants with at least 50% reduction of mean 24-hour stress IEFs from baseline to week 8.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This is a three-armed, randomised, SA-controlled and WL-controlled trial conducted at five recruitment sites, which are Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences; Hengyang Hospital affiliated to Hunan University of Chinese Medicine; Yantai Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine; the third affiliated hospital of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; and Jiangxi Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

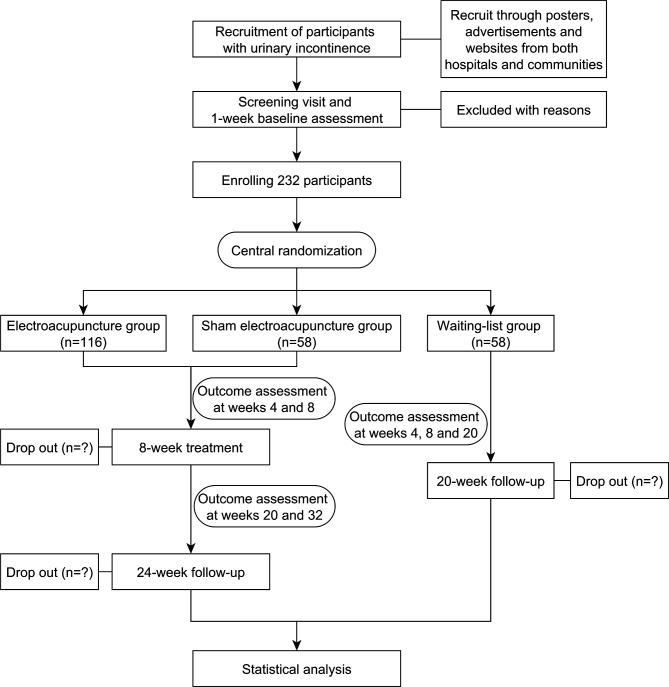

The study duration is 33 weeks for participants in the EA and SA groups, with 1-week baseline assessment, 8-week treatment and 24-week follow-up, while 21 weeks for participants in the WL group, with 1-week baseline assessment and 20-week watchful waiting (figure 1). The study will start recruitment on 9 October 2020 and is anticipated to finish the treatment and follow-up on 30 September 2023. Participations in the EA and SA groups, outcome assessors, data managers and statisticians will be blinded to the group allocation, while acupuncturists and participants in the WL group will not be blinded for obvious reasons.

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public are not involved in the design, conduct, report or dissemination of our research.

Inclusion criteria

Diagnosis of MUI by the coexistence of SUI and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) symptoms in accordance with EAU guideline.7

Female participants aged between 35 and 75.

Stress index > urge index in accordance with Medical, Epidemiologic, and Social Aspects of Aging Questionnaire.17

Symptom of MUI for at least 3 months and SUI episodes outnumber 50% of total IEFs documented in 3-day voiding diary.

Less than 12 micturition episodes in average of 24 hours documented in 3-day voiding diary.

Positive cough stress test.

Urine leakage >1 g in 1-hour pad test.18

Voluntary participation in the trial and signed written informed consent.

Participants meeting all these eight inclusion criteria might be able to be enrolled.

Exclusion criteria

Urgency-predominant MUI, pure SUI, pure UUI, overflow UI and neurogenic bladder.

Uncontrolled symptomatic urinary tack infection.

Tumour in urinary system and pelvic organ.

Pelvic organ prolapse ≥ degree II.

Residual urine volume ≥100 mL.

History of treatments specific for UI, such as acupuncture, PFMT and medications in the previous 1 month.

History of surgery specific for UI or in pelvic floor, including hysterectomy.

Uncontrolled diabetes or severe high blood pressure.

Nervous system diseases that may hamper the function of the urinary system, such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, cauda equina nerve injury or multiple system atrophy.

Severe heart, lung, brain, liver, kidney and mental illness; coagulation dysfunction; or obvious cognitive dysfunction.

Installed cardiac pacemaker.

Inconvenient or unable to walk, run and go up and down stairs.

Allergy to metal, dreadful fear of acupuncture needles or unbearable to EA.

Women who are pregnant at present, plan to conceive in future 1 year’s period, are at lactation period or gave birth in the previous 12 months.

Participants with either situation mentioned above will not be enrolled in the trial.

Randomisation and allocation concealment

The random sequence will be produced by a third independent party (Linkermed Technology Co., Beijing, China). Eligible participants will be randomly assigned into the EA, SA or WL group at 2:1:1 ratio, stratified by recruitment sites and using variable blocks. The random number and group allocation will be acquired by acupuncturists in each recruitment site by logging in the central randomisation system and typing in basic information of eligible participants.

Interventions

The acupuncture point regimen and administration protocol are both based on the results of previous studies and specialist consensus.14 15 Participants in the EA group will receive stimulation at bilateral Bladder Meridian 33 (BL33, Zhongliao), BL35 (Huiyang) and Spleen Meridian 6 (SP6, Sanyinjiao). BL33 is located in the third posterior sacral foramen; BL35, 0.5 proportional bone (skeletal) cun (B-cun) (≈10 mm) lateral to the extremity of the coccyx; and SP6, posterior to the medial border of the tibia, three B-cun superior to the prominence of the medial malleolus.19 Bilateral BL33 will be inserted by acupuncture needles (Huatuo, Suzhou Medical Appliance) of 0.30×75 mm size at an angle of 45°, inward and downward, until the depth of 60–70 mm. Bilateral BL35 will be inserted by needles of 0.30×75 mm size, slightly outward and upward, until the depth of 60–70 mm. Bilateral SP6 will be inserted by needles of 0.30×40 mm until the depth of 25–30 mm. All the needles will be lifted, thrusted and twisted evenly for three times, right after insertion, to induce the sensation of deqi. Electronic acupuncture apparatus (Yingdi KWD 808 I electro pulse acupuncture therapeutic apparatus, Changzhou Yingdi Electronic Medical Device Co.) will be connected to the three pairs of needles transversally, with a continuous wave of 20 Hz, electric current of 2–6.5 mA for BL33 and BL35 and 1–3.5 mA for SP6. The EA stimulation will last 30 min for each session, three sessions a week (ideally every other day) for a succession of 8 weeks.

Participants in the SA group will receive superficial insertion at bilateral sham BL33 (Zhongliao), sham BL35 (Huiyang) and sham SP6 (Sanyinjiao). Sham BL33 is in the area one B-cun (≈20 mm) horizontally outside of BL33; sham BL35, one B-cun (≈20 mm) horizontally outside of BL35; sham SP6, in the middle of SP6 and tendons. Acupuncture needles of 0.30×40 mm size will be inserted at a depth of 2–3 mm until the needles can stand still. No manipulation will be conducted, and the sensation of deqi will not be induced. Electronic acupuncture apparatus (Yingdi KWD 808 I electro pulse acupuncture therapeutic apparatus, Changzhou Yingdi Electronic Medical Device Co.) will be connected to the three pairs of needles transversally, with a continuous wave of 20 Hz and minimal electric current (ideally at a degree that participant can just perceive). In about 30 s, the electric current will be turned down, leaving the indicator light and ticking sound on. The treatment sessions are similar to those in the EA group.

Participants in the EA and SA groups will be blinded to the group allocation. Acupuncturists and research assistants will be instructed not to tell the group allocation to participants. Additionally, to avoid inadvertent unblinding, contact between participants and project staff will be reduced as much as possible during treatment. The manipulation of acupuncture, connecting to electronic apparatus and withdrawal of needles will be separately undertaken by acupuncturists and another research assistant. Participants will be treated separately with curtain drawn and their companions waiting outside the clinic, if any. Before manipulation, participants will be told they may feel the electrical stimulation fade down gradually, even to the degree that they cannot perceive, and that is because the body has built up a tolerance to the electrical stimulation during the treatment process. Within 5 min after either treatment session at week 8, participants will be told they may have received EA treatment with deep insertion or SA treatment with shallow insertion. Then, the participants will be asked to answer the question do you think you have received EA treatment and choose answer between the options of Yes or No.

Participants in the WL group will not receive active treatment. After the trial, they will receive 24-session EA treatment mentioned above as compensation.

Participants in all the three groups will receive handbook of advice on healthcare education and lifestyle modification, concerning exercise, fluid intake, weight loss, smoking and respiratory symptoms, constipation, heavy lifting and urinary tract infection. During the process of the trial, participants are not allowed to take other specialised medication or therapies for UI, such as PFMT or antimuscarinic agents; details should be recorded in case report form (CRF), if used. Any medications that might influence the function of lower urinary tract should also be documented in CRF.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the proportion of participants with at least 50% reduction in mean 24-hour stress IEFs from baseline to week 8, measured by 3-day voiding diary. Reduction of at least 50% in IEF is regarded as successful treatment in clinic,20 and 3-day voiding diary is a reliable and validated tool for UI in both clinic and research, without much burden placed on participants.21 In 3-day voiding diary, IEF of different types, micturition and nocturia episodes, fluid intake and pad consumptions will be documented.

Secondary outcomes

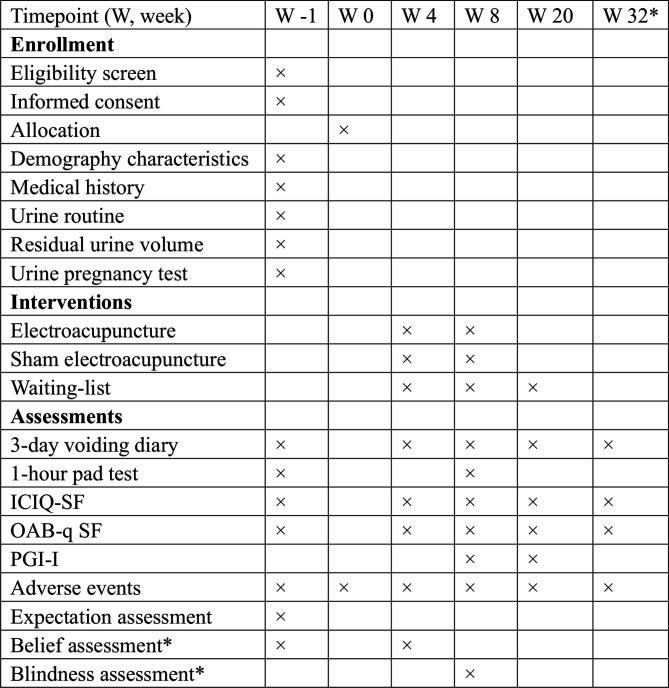

Secondary outcomes will be measured by 3-day voiding diary, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) and Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (OAB-q SF) at weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32; 1-hour pad test at week 8; and Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) at weeks 8 and 20 (figure 2). The specific secondary outcome measures and time frame are displayed in table 1 Secondary outcome measures.

Figure 2.

Study schedule. *Only for participants in electroacupuncture and sham electroacupuncture groups. ICIQ-SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form; OAB-q SF, Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form; PGI-I, Patient Global Impression of Improvement.

Table 1.

Secondary outcome measures

| No | Outcome measure | Time frame |

| 1 | Proportion of participants with at least 50% reduction of urinary leakage amount from baseline | Week 8 |

| 2 | Change of urinary leakage amount from baseline | Week 8 |

| 3 | Proportion of participants with at least 50% reduction of mean 24-hour stress incontinence episode frequencies (IEFs) from baseline | Weeks 4, 20 and 32 |

| 4 | Change of mean 24-hour IEF from baseline | Weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32 |

| 5 | Change of mean 24-hour stress IEF from baseline | Weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32 |

| 6 | Proportion of participants with at least 50% reduction of mean 24-hour IEF from baseline | Weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32 |

| 7 | Change of total score and subscore of International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) from baseline | Weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32 |

| 8 | Change of total score and subscore of Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (OAB-q SF) from baseline | Weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32 |

| 9 | Change of mean 24-hour pad consumption from baseline | Weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32 |

| 10 | Proportion of participants with adequate improvement assessed by Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) | Weeks 8 and 20 |

| 11 | Change of mean 24-hour urgency episodes from baseline | Weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32 |

| 12 | Change of mean 24-hour micturition episodes from baseline | Weeks 4, 8, 20 and 32 |

| 13 | Participants' expectations of improvement to urinary incontinence | Baseline |

| 14 | Participants’ belief that acupuncture might help | Baseline and week 4 |

| 15 | Blinding assessment | Week 8 |

ICIQ-SF is a validated tool to assess the frequency and severity of UI and its influence on quality of life (QoL) in the past 4 weeks.22 23 The total score of the questionnaire ranges from 1 to 21, with higher score indicating greater severity of symptoms.

OAB-q SF is used to assess the OAB symptom bother and the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in the past 4 weeks.24 25 The domains include coping, concern, sleep and emotional interactions. The scores are transformed to 0-point to 100-point scales, with higher scores on the symptom bother scale indicating severe symptoms and higher scores on the HRQOL indicating a better HRQOL.

One-hour pad test is the only tool standardised with a set protocol to measure the urinary leakage.18 Participants will be instructed to drink 500-mL sodium-free water and perform a series of activities including standing and sitting, coughing, running, picking up a coin and putting hands under water. The leakage amount in 1 hour will be measured via pad.26

PGI-I is a global index, with only one item, used to rate the participants’ subjective perception on symptom improvement. Participants will describe their impression from very much better to very much worse.27 Improvement was considered to be clinically significant if the participant’s response is ‘Much better’ or ‘Very much better’.

To assess participants’ expectations of improvement in UI, at baseline, participants will be asked how do they expect the UI to be in 2 months. They will choose the answer form the options of ‘Much better’, ‘Better’, ‘Don’t know’, ‘Same’ and ‘Worse’.

To assess participants’ belief that acupuncture might help, both at baseline and week 4, participants in the EA and SA groups will answer how do they think their incontinence problem may be helped by acupuncture. They will choose the answer from the options of ‘Very ineffective’, ‘Fairly ineffective’, ‘Can’t decide’, ‘Effective’ and ‘Very effective’.

Safety assessment

Adverse events (AEs), associated with the intervention or not, will be monitored and documented by participants and research assistants in Adverse Event Record Form and CRF throughout the trial. Whether the events are related to the treatments will be decided by acupuncturists and related specialists in each site within 24 hours of occurrence. Acupuncture-related AEs are defined as following: broken needle, needle phobia, intense pain that is unbearable, bleeding, haematoma, infection or abscess at the needling site and other discomfort induced by acupuncture, such as pain, nausea, vomiting, palpitation, dizziness, headache, loss of appetite or insomnia that lasts for 1 hour or longer after treatment.

Quality control

To ensure consistency of the study, personnel in recruitment sites will receive extensive training from the principal investigator (Z Liu) concerning the protocol, manipulating methods of acupuncture and blinding of participants, etc.

At least two certified acupuncturists (with no less than 2-year clinical experience) are needed for rotation in each site, while the 24-session treatment of each participant should be completed by one specific acupuncturist. Additionally, the same participants should be taken charge of by the same research assistant/outcome assessor throughout the trial. They will instruct participants to complete voiding diary, explain the contents of handbook if necessary and remind the participants of their schedule by phone or WeChat.

To promote the adherence on lifestyle modification, the research assistants will remind the participants to adjust their lifestyle per the suggestions and record the changes of condition and lifestyle on Lifestyle Record Form every week. On each outcome assessment visit, the forms will be collected and examined by outcome assessors and recorded in CRF in time.

All the data collected will be documented in paper CRF first and typed into Electronic Data Capture (EDC) system within 1 week by clinical research coordinator. This rule is set to ensure the date is traced back, monitored by the system automatically and clinical research associate and supplemented without delay, if missing or inaccurate. In follow-up period, missing data in voiding diary can be asked by phone rather than in person. The database will be protected by a password, and only the principal investigator will have access to the final dataset. Data are available on reasonable request to the principal investigator, excluding the private information of patients.

Sample size

Based on our previous study,14 15 we assume that 25% of participants in the SA group will have at least 50% reduction of mean stress IEF from baseline to week 8. To detect a difference of 23% between the EA and SA group, a sample size of 232 participants will need to provide the trial with 80% power with a two-sided significance level of 0.05% and 10% dropouts.

Statistical analysis

For the primary hypothesis, we will compare the proportion of participants with at least 50% reduction in mean 24-hour stress IEF at week 8 among the three groups. The primary outcome analysis will use the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test to compare the rate of participants with at least 50% reduction in stress IEF at week 8 between the EA group and the WL group. If this analysis is significant, the hierarchical testing will be used in the EA group versus the SA group.

For other categorical variables, comparisons between treatment groups will be assessed using the Fisher’s exact test or Χ2 test as appropriate. We will use the t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test to analyse change of urinary leakage amount from baseline, change of mean 24-hour IEF from baseline, change of total score and subscore of ICIQ-SF from baseline, change of 24-hour urgency episodes from baseline and other continuous variables. Χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests will be used to compare the frequency of AEs between groups.

All the outcomes will be analysed in intention to treat population (defined as participants randomised). Analysis will be performed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute) with a two-sided p value of less than 0.05 considered significant.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by Guang’anmen Hospital Institutional Review Board (2019-241-KY). The trial will be conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization E6 Guidance for Good Clinical Practice. Detailed information of the trial will be informed to the participants, and written informed consent will be obtained from every participant. Participants in the WL group will receive 24-session EA treatment for compensation. Results of the trial are expected to be published on a peer-reviewed journal.

Discussion

MUI is a condition frustrating almost 30% of women globally, while about half of them feel embarrassed to report it.3 5 The physiology underlying MUI remains unclear. UUI is closely associated with physiological perturbations to bladder function, such as detrusor overactivity, poor detrusor compliance and bladder hypersensitivity,11 while urethral hypermobility resulting from weak pelvic floor or poorly supported urethral sphincter or intrinsic urethral sphincter deficiency has been proposed as the main pathophysiology of SUI.28 Electroacupuncture may relieve the symptoms of MUI by modulating the function of related nerves. Acupuncture points of BL 33, BL35 and SP6 are located in the lumbosacral region and posterior tibial region, in the distribution area of sacral plexus and pudendal nerves. Either by direct stimulation or by indirect stimulation via the sacral roots or plexus, the pudendal afferent can be activated to induce a strong inhibition of the detrusor hyperreflexia and cause detrusor relaxation.29 Additionally, stimulation of pudendal nerves can contract the pelvic floor muscle and simulate PFMT,30 which can improve urethral function and relieve SUI symptoms.31

Since a lot of Chinese have received acupuncture before, superficial insertion at non-acupuncture point area with minimal and transient electric current is applied as sham control to eliminate placebo effects. The superficial insertion enables participants to perceive the stimulation and electric current promptly, and the transient electric current can enhance the blinding even if it lasts only about 30 s. It is argued that minimal acupuncture may evoke physiological effects,32 especially for pain and depression.33 34 However, the pathology of MUI is mainly sphincter insufficiency and detrusor overactivity. Studies indicate that the rheobase of the normal bladder was 1–5 mA.35 The transient and minimal current output may not produce effects on the function of the bladder. In the WL group, participants only receive healthcare education and lifestyle modification. The WL control is applied to eliminate the influence of disease’s natural cause.

Limitation also exists in the design of this trial. Participants in the WL group and acupuncturists cannot be blinded, which might induce performance and detection bias. However, large bias is unlikely to be attached to the results since the primary outcome of stress IEF is objective. In addition, the outcome assessors will be blinded to group allocation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Appreciation to every participant in the trial and every personnel in recruitment sites for their contributions.

Footnotes

YS and YL contributed equally.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it first published. The provenance and peer review statement has been included.

Contributors: ZL conceived the study, initiated the design and revised the manuscript; YL is responsible for statistical analysis plan and drafted the manuscript; YS participated in the design and drafted the manuscript; HC participated in the design and revised the manuscript; YY helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by ‘The 13th Five-year’ National Science and Technology Pillar Program (grant number 2017YFC1703602) by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. They have no role in study design and will have no role in collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design or conduct or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 2010;29:4–20. 10.1002/nau.20798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minassian VA, Devore E, Hagan K, et al. Severity of urinary incontinence and effect on quality of life in women by incontinence type. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1083–90. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31828ca761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dooley Y, Lowenstein L, Kenton K, et al. Mixed incontinence is more bothersome than pure incontinence subtypes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:1359–62. 10.1007/s00192-008-0637-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu L, Li L, Lang J, et al. Epidemiology of mixed urinary incontinence in China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;109:55–8. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thom DH, van den Eeden SK, Ragins AI, et al. Differences in prevalence of urinary incontinence by race/ethnicity. J Urol 2006;175:259–64. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00039-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers DL. Female mixed urinary incontinence: a clinical review. JAMA 2014;311:2007–14. 10.1001/jama.2014.4299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkhard FC, Bosch J, Cruz F. EAU guidelines on urinary incontinence in adults. Available: https://uroweb.org/guideline/urinary-incontinence [Accessed 4 Nov 2017].

- 8.Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;10:CD005654. 10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bo K, Kvarstein B, Nygaard I. Lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic floor muscle exercise adherence after 15 years. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:999–1005. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157207.95680.6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labrie J, Berghmans BLCM, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1124–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1210627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoki Y, Brown HW, Brubaker L, et al. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17042. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JK-S, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, et al. Persistence of urgency and urge urinary incontinence in women with mixed urinary symptoms after midurethral slings: a multivariate analysis. BJOG 2011;118:798–805. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02915.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richter HE, Litman HJ, Lukacz ES, et al. Demographic and clinical predictors of treatment failure one year after midurethral sling surgery. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:913–21. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820f3892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z, Liu Y, Xu H, et al. Effect of electroacupuncture on urinary leakage among women with stress urinary incontinence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:2493–501. 10.1001/jama.2017.7220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu B, Liu Y, Qin Z, et al. Electroacupuncture versus pelvic floor muscle training plus solifenacin for women with mixed urinary incontinence: a randomized Noninferiority trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:54–65. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Liu Y, Su T, et al. Comparing the effect of electroacupuncture treatment on obese and non-obese women with stress urinary incontinence or stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence: a secondary analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract 2019:e13435. 10.1111/ijcp.13435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herzog AR, Diokno AC, Brown MB, et al. Two-year incidence, remission, and change patterns of urinary incontinence in noninstitutionalized older adults. J Gerontol 1990;45:M67–74. 10.1093/geronj/45.2.M67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krhut J, Zachoval R, Smith PP, et al. Pad weight testing in the evaluation of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2014;33:507–10. 10.1002/nau.22436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific . WHO standard acupuncture point locations in the Western Pacific region. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yalcin I, Peng G, Viktrup L, et al. Reductions in stress urinary incontinence episodes: what is clinically important for women? Neurourol Urodyn 2010;29:344–7. 10.1002/nau.20744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bright E, Cotterill N, Drake M, et al. Developing and validating the International consultation on incontinence questionnaire bladder diary. Eur Urol 2014;66:294–300. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang L, Zhang S-wen, Wu S-liang, et al. The Chinese version of ICIQ: a useful tool in clinical practice and research on urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2008;27:522–4. 10.1002/nau.20546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, et al. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2004;23:322–30. 10.1002/nau.20041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKown S, Abraham L, Coyne K, et al. Linguistic validation of the N-QOL (ICIQ), OAB-q (ICIQ), PPBC, OAB-S and ICIQ-MLUTSsex questionnaires in 16 languages. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:1643–52. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02489.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyne KS, Thompson CL, Lai J-S, et al. An overactive bladder symptom and health-related quality of life short-form: validation of the OAB-q SF. Neurourol Urodyn 2015;34:255–63. 10.1002/nau.22559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abrams P, Blaivas JG, Stanton SL, et al. Standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. Neurourol Urodyn 1988;7:403–27. 10.1002/nau.1930070502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viktrup L, Hayes RP, Wang P, et al. Construct validation of patient global impression of severity (PGI-S) and improvement (PGI-I) questionnaires in the treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. BMC Urol 2012;12:30. 10.1186/1471-2490-12-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshimura N, Miyazato M. Neurophysiology and therapeutic receptor targets for stress urinary incontinence. Int J Urol 2012;19:524–37. 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.02976.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosch JLHR. Electrical neuromodulatory therapy in female voiding dysfunction. BJU Int 2006;98:43–8. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, Zhang S. Simultaneous perineal ultrasound and vaginal pressure measurement prove the action of electrical pudendal nerve stimulation in treating female stress incontinence. BJU Int 2012;110:1338–43. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng K, Balog BM, Lin DL, et al. Daily bilateral pudendal nerve electrical stimulation improves recovery from stress urinary incontinence. Interface Focus 2019;9:20190020. 10.1098/rsfs.2019.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lund I, Näslund J, Lundeberg T. Minimal acupuncture is not a valid placebo control in randomised controlled trials of acupuncture: a physiologist's perspective. Chin Med 2009;4:1. 10.1186/1749-8546-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith CA, Armour M, Lee MS, et al. Acupuncture for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;3:CD004046. 10.1002/14651858.CD004046.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1444–53. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katona F. Stages of vegatative afferentation in reorganization of bladder control during intravesical electrotherapy. Urol Int 1975;30:192–203. 10.1159/000279979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.