Abstract

Eagle Syndrome (ES), also termed stylohyoid syndrome or styloid syndrome, is a rare condition characterised by a cluster of symptoms related to an elongation of the styloid process (SP) of the temporal bone. These may range from mild pharyngeal foreign body sensation and dysphagia to severe orofacial pain. High clinical suspicion is necessary owing to the unspecific clinical picture and limited diagnostic clues. Until a definitive diagnosis is achieved, these patients may develop symptoms which significantly impact their quality of life. The aim of this article is to report a case of ES in which a considerable length of SP was documented. Diagnosis was made years after the initial complaints and several medical workups by different specialties. Surgical resection of the elongated process by cervical approach was the adopted treatment modality. Patient recovery and follow-up was satisfactory, with remission of the afflicting symptoms.

Keywords: head and neck surgery, pain, oral and maxillofacial surgery

Background

This case was a diagnostic challenge as a refractory temporomandibular joint disease, a condition which could indeed explain most of the complaints, had already been assumed in this patient. The diagnosis could still be elusive to us to this day, had it not been for a strong clinical suspicion, leading to a more careful examination of the patient. This allowed for adequate surgical management of the condition with very satisfactory outcomes.

Such a case raises the question, as formerly suggested in other literature, as to whether the prevalence of this condition would be masked by an alternative more common diagnosis.

Case presentation

A 55-year-old woman was referred to our maxillofacial department with chronic right temporomandibular complaints with a serious impact on her quality of life for the last 5 years. She experienced intense episodic pain located in the right pre-auricular area with ipsilateral temporal radiation. Onset was sudden, unrelated to mastication, yawning or talking — but sometimes elicited by neck movement and auto-perception of stressful moments. Episodes lasted from several hours to a few days and recurred sporadically and unpredictably.

Her medical history included chronic migraines for the last 20 years. No previous surgeries were recorded.

Previous assessment by otorhinolaryngology found no disease that justified such temporal region complaints. The patient had also been investigated by neurology department with the diagnostic hypothesis of trigeminal neuralgia; however, proposed medical therapy failed to achieve pain control. Radiological control with CT scans of the head discarded any brain lesion.

A maxillofacial surgeon, 4 years prior, had also evaluated the patient. Complaints were attributed to right temporomandibular joint arthralgia and the patient diagnosed with temporomandibular joint dysfunction, based on physical examination (no radiological workup had been requested). Suggested treatment was conservative and comprised of prescription of oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and diazepam and occlusal splint therapy. Symptoms appeared to subside for a certain period and the patient was then discharged.

Later recurrence and progressive worsening of symptoms led to the repeated referral to our department. Patient examination was largely unremarkable, except for the palpation of the right posterior floor of the mouth, which was tender and revealed a hard prominence. No pain was elicited on the palpation of masticatory and neck muscles or the temporomandibular joint. No indirect signs of disc displacement were evident. Mouth opening was unlimited and without deviation. Neck palpation and lateralisation were not painful. There were no mucosal lesions or odontalgia on tooth percussion. Saliva secretion was normal bilaterally and the tonsils appeared to be of regular dimension.

Investigations

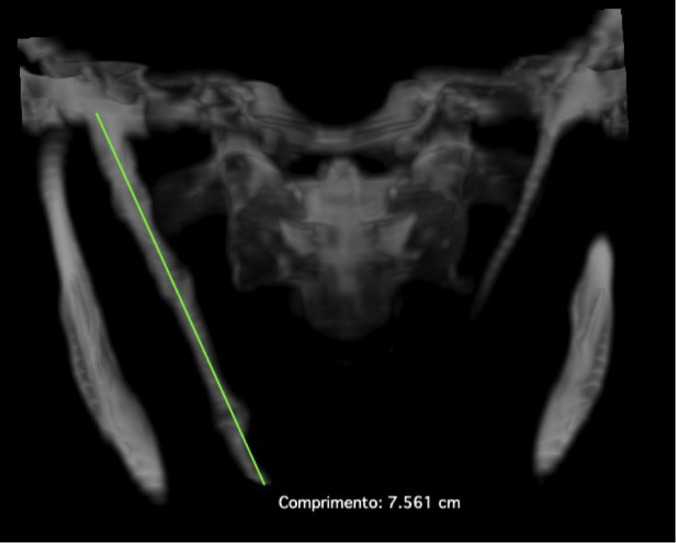

Open and closed mouth position panoramic radiographs were obtained, suggesting a marked elongation of the right styloid process (SP). No radiological indirect signs of arthropathy were found on either side (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Panoramic radiograph showing an elongated right styloid process (yellow arrowhead).

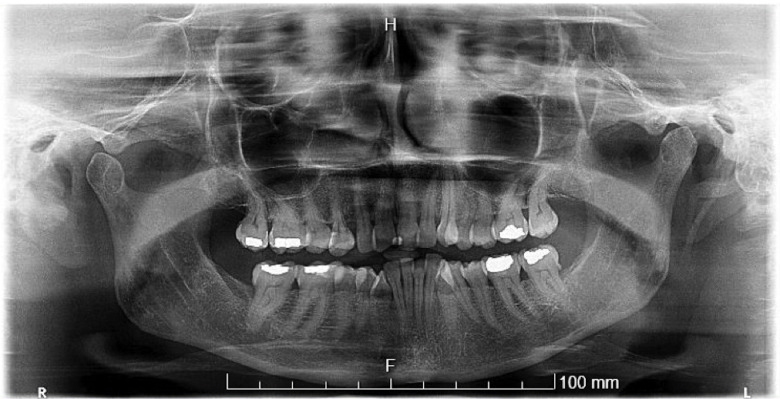

CT of the head and neck confirmed the previous findings by showing an elongated, pseudoarticulated SP touching the ipsilateral greater horn of the hyoid bone. Total length as calculated by the CT scans was 75.61 mm (figures 2 and 3). These radiological findings were consistent with the hard intra-oral projection previously palpated.

Figure 2.

CT scan (three-dimensional reconstruction) showing a pseudo-articulated elongated SP.

Figure 3.

Right styloid process (75.61 mm) as measured by CT scan (multiplanar reconstruction).

Since no other abnormal variables were found during clinical workup, the finding of an elongated SP in a patient presenting with orofacial pain prompted the diagnosis of Eagle Syndrome (ES).

Treatment

Surgical styloidectomy was the chosen treatment. A cervical transcutaneous approach was preferred based on the length of the SP and risk of iatrogenic neurovascular injury. Three-dimensional reconstructions of the head and neck CT scans aided in surgical planning.

An 8-cm skin incision was made using a pre-existing skin crease on the right side of the neck, 2 cm below the inferior border of the mandible. Other relevant surgical landmarks (the right mandibular angle, the hyoid bone and the elongated SP) had also been previously marked with a dermographic pen (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Preoperative markings — (A) right mandibular angle; (B) hyoid bone; (C) elongated styloid process; and (D) cervical incision.

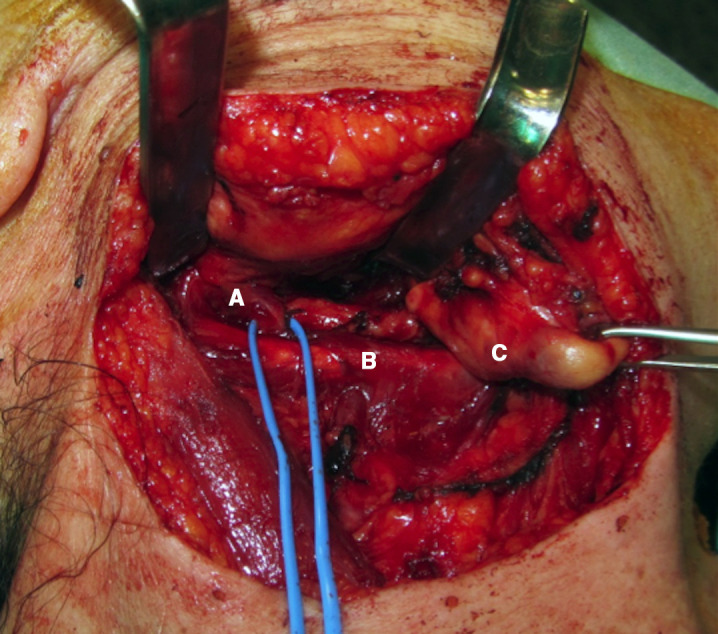

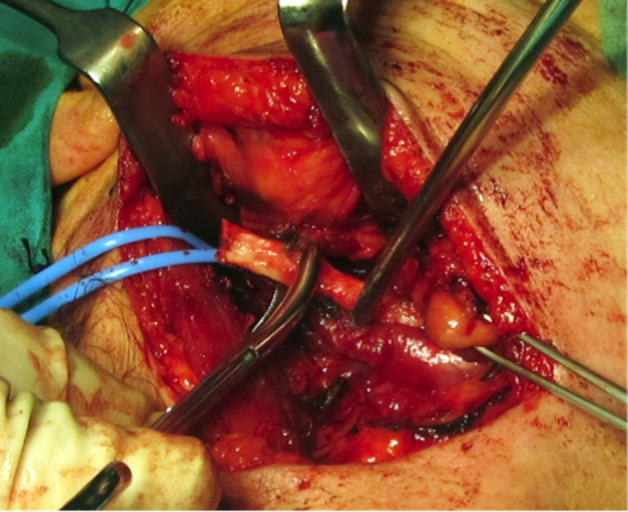

Dissection was performed through the platysma muscle and the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. The submandibular gland was identified and retracted; the sternocleidomastoid muscle was slightly retracted laterally and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle retracted inferiorly. Further dissection and palpation revealed the elongated SP; the hypoglossal nerve was found to be anterior to the SP (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Intraoperative dissection — (A) hypoglossal nerve (blue elastic); (B) elongated styloid process; and (C) right submandibular gland (retracted).

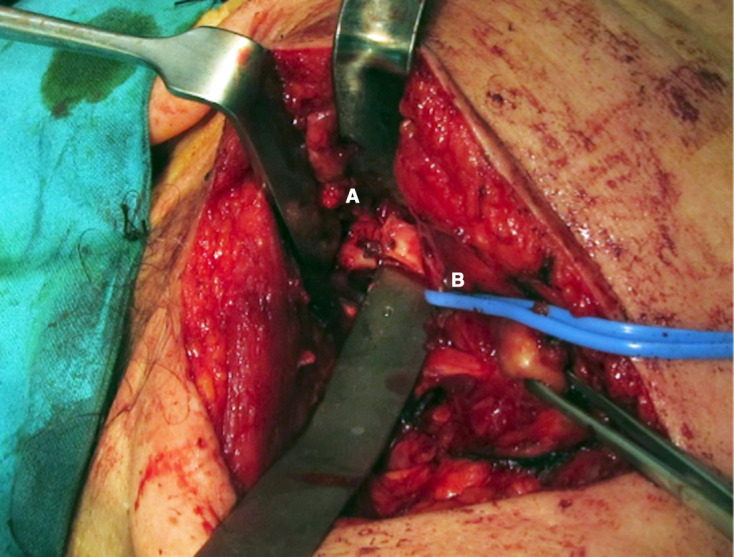

A styloidectomy was performed by combination of osteotome and bone saw osteotomies (figures 6 and 7). The excised portion of the SP was 62 mm in length, 7 mm width at the base and a diameter of 10 mm at the widest point (figures 8 and 9).

Figure 6.

(A) Osteotomy of the elongated styloid process at the base and (B) hypoglossal nerve (blue elastic, retracted).

Figure 7.

Completion of the styloidectomy procedure.

Figure 8.

Size comparison between (top to bottom) surgeon’s index finger, excised portion of the styloid process and number 15 scalpel blade.

Figure 9.

Styloidectomy specimen.

Wound closure was performed in layers and a suction drain was placed. Adjuvant medical therapy consisted of analgesics. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 3 days postoperation.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperation after a month period, the patient reported a significant improvement in symptoms, along with a marked decrease in headache occurrence. There were complaints of occasional, but less intense, episodes of oropharyngeal discomfort. A postoperative panoramic radiograph was also obtained (figure 10).

Figure 10.

Postoperative panoramic radiograph.

An element of right hypoglossal nerve neuropraxia was noted on tongue protrusion, as anticipated from the necessary manipulation of the nerve which had been in close proximity to the SP. Such paresis in this case did not affect deglutition, speech or upper airway ventilation. Six months after the procedure, these findings had gone into remission and the patient was conclusively discharged.

Discussion

ES is a cluster of symptoms related to an elongation of the SP of the temporal bone.1 2 This was initially described by the otorhinolaryngologist, Watts Weems Eagle, in 1937.3 Symptoms are rather unspecific and may range from throat pain (frequently radiating to the ipsilateral ear or the mastoid region), pharyngeal foreign body sensation, dysphagia, orofacial pain to headaches.1 3–7

The SP (‘styloid’, ie, ‘pen shaped’) is a bony projection embryologically originating from the second pharyngeal arch.2 5 It protrudes from the inferior part of the temporal bone1 5 8 and is an attachment site for three muscles (the stylopharyngeus, the styloglossus and the stylohyoid muscles) and two ligaments (the stylohyoid and the stylomandibular ligaments)4 5—also known as the ‘Riolan’s bouquet’.9

The distal tip lies between the internal and external carotid arteries, pointing medially and anteriorly.4 10 It is thus in close anatomic proximity to several important structures: the internal jugular vein, the internal carotid and occipital arteries and the glossopharyngeal, the vagus, the accessory and the hypoglossal nerves (respectively, the cranial nerves IX, X, XI and XII).5 7 An abnormally curved or elongated SP may injure any of these structures.

As for the epidemiology of ES, multiple studies with different criteria have been published.2 In 2017, Badhey et al made a comprehensive review of such literature.2 They found that different authors would consider different radiological length of SP as the upper limit of normal (25 mm, 30 mm and 40 mm).2 Although ‘normal SP length’ is not constant in the literature (Eagle described normal SP length as between 25 mm and 30 mm3 6 11), more than 30 mm is usually considered to be excessive.1 5 8

Badhey et al found incidences of elongated SP varying from 4% to 7.3%.2 In studies which considered calcification of the stylohyoid complex, incidence was found to be higher (22%–84%).2 Regardless of all these findings, only a small fraction (4%–10%) of these patients would be symptomatic,2 meaning that the large majority of elongated SPs are asymptomatic.3 4 11

Consequently, an elongated SP in an asymptomatic patient does not constitute towards a diagnosis of ES.1 SP elongation is not pathognomonic of ES and might constitute only an incidental radiological finding.12 Neither does the length of the SP seem to correlate with the severity of symptoms.1

Radiological studies comprise the lateral view, the anterior view and panoramic radiographs, where one can eventually visualise SP elongation and deviation.12 However, CT-scan studies are very useful in complementing the imagiological investigation and are the preferred imaging modality.7 12

The diagnosis is made based on clinical findings (pain elicited on palpation of the tonsillar fossa and palpation of the SP on the tonsillar fossa) and confirmed by imaging studies.1 4 6 11–15 Palpation of the SP in the tonsillar fossa is an abnormal finding, in which case it is considered to be elongated.4 6 11–14 The clinical history will often include a previous tonsillectomy,6 although this is not a prerequisite for the development of ES.1

With such scarce diagnostic clues, there seems to be an under diagnosis of this condition,16 probably because it often presents with diverse clinical presentations and non-specific symptoms.2 17 Often this results in a diagnosis of exclusion.18 This might lead to protracted complaints with great emotional distress to the patient.8

As Har-El et al underlined almost 30 years ago, multiple cases of misdiagnosis have been reported and consequently mistreated for long periods by many medical and surgical specialties.19 It is thus legitimate to assume that in addition to these reports many more instances of unreported misdiagnosis must exist. For this reason, general practitioners, otolaryngologists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, dentists and maxillofacial surgeons need to be aware of this entity.19 Differential diagnosis might mislead the clinician as it might include a multitude of oro–maxillofacial and cervical entities. Among others, one would consider:

Cervical vertebral arthritis.18

Chronic pharyngotonsillitis.15 18 20

Cranial nerve neuralgia.10 15 18

Ernest’s syndrome.18

Oesophageal diverticula.18

Hyoid bone syndrome.18

Hyoid bursitis.18

Inner ear problems.18

Migraine, tension headache and cluster headache.18 20

Neoplastic conditions.15 18

Psychosomatic disease, myofascial pain syndrome and fibromyalgia syndrome.18 20

Salivary gland disease.20

Sluder’s syndrome.18

Superior pharyngeal constrictor syndrome.18

Temporal arteritis.10 18

Temporomandibular joint disease.10 15 18

Surgical styloidectomy is the preferred treatment7 17 and might be performed either transcervically or transorally.1 7 15 17 Eagle advocated surgery by intra-oral approach.3 4 6 11 It is less time consuming, has a lower risk of complications and produces less scar formation.1 Contamination of cervical spaces from oral tract bacteria is, conversely, a potential risk.13 Some authors will still prefer this approach today.13

Recently, Papadiochos et al presented a case of a transcervical approach in a patient where a transoral approach had previously been unsuccessfully attempted.21 In this report, the authors pointed out the longer operative time as well as the visible scar and possible facial nerve (mandibular branch) injury in the transcervical approach.21 On the other hand, they highlighted the wider surgical field and visibility, feasibility to manage/avoid the risk of iatrogenic neurovascular injury and access from a non-contaminated field in the latter.21 In contrast, the intra-oral approach may result in a limited surgical field, a higher risk of haemorrhage and nerve injury, limitations due to mouth opening, a greater risk of cervical infection and a limited resection of SP.21

Patient’s perspective.

Before the diagnosis I was in constant fear that the pain would appear, and how severe the pain would be that day. The fear of a yawn or a simple bite on bread or an apple. Even a simple squat would bring an enormous level of anxiety because that was how I was once rushed to the hospital’s emergency department with great pain.

After surgery, the fear of recovery is inevitable; but also a great feeling of relief after the diagnosis and treatment with definitive resolution of my problem, thus contributing to the end of my constant anxiety.

Learning points.

Styloid process length is variable and sometimes elongated processes will cause an array of unspecific symptoms owing to their relation to nearby anatomical structures.

Eagle Syndrome is often underdiagnosed, sometimes with a protracted course of disease and important patient distress until it is ultimately managed.

Diagnosis is of exclusion and various differentials must be considered.

Different specialties need to be aware of this entity: general practitioners, otolaryngologists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, dentists and maxillofacial surgeons.

The treatment of choice is surgical styloidectomy, either with intra-oral or trans-cervical techniques.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank: (a) Dr Nuno Pereira da Silva (Radiology Resident, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, EPE) for helping us with CT reconstructions; (b) Dr Linda Pereira for her kind and thorough grammar and language revision of the manuscript; (c) as well as all the medical and non-medical staff in the maxillofacial surgery department, who directly or indirectly helped with this case.

Footnotes

Contributors: LAB was the main surgeon performing the described surgical procedure, and encouraged JFdB and MVR to investigate specific aspects of this entity. The manuscript was written by JFdB and MVR with input of all the authors. LAB and ICA supervised the findings of this work and consulted on the theoretical framework. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Li S, Blatt N, Jacob J, et al. Provoked Eagle syndrome after dental procedure: a review of the literature. Neuroradiol J 2018;31:426–9. 10.1177/1971400917715881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badhey A, Jategaonkar A, Anglin Kovacs AJ, et al. Eagle syndrome: a comprehensive review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2017;159:34–8. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid processes: report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol 1937;25:584–7. 10.1001/archotol.1937.00650010656008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process; symptoms and treatment. AMA Arch Otolaryngol 1958;67:172–6. 10.1001/archotol.1958.00730010178007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abuhaimed AK, Menezes RG, Abuhaimed AK, et al. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Styloid Process : StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Treasure Island (FL), 2019: 1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eagle WW. Symptomatic elongated styloid process; report of two cases of styloid process-carotid artery syndrome with operation. Arch Otolaryngol 1949;49:490–503. 10.1001/archotol.1949.03760110046003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santini L, Achache M, Gomert R, et al. Transoral surgical treatment of Eagle's syndrome: case report and review of literature. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol 2012;133:141–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ettinger RL, Hanson JG. The styloid or “Eagle” syndrome: An unexpected consequence. Oral Surgery, Oral Med Oral Pathol 1975;40:336–40. 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90416-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouviere H, Delmas A. Anatomía Humana Descriptiva, topográfica Y funcional. Tomo 1. Cabeza Y cuello. 11th edn, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chase DC, Zarmen A, Bigelow WC, et al. Eagle’s syndrome: A comparison of intraoral versus extraoral surgical approaches. Oral Surgery, Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986;62:625–9. 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90253-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process; further observations and a new syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol 1948;47:630–40 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18894764 10.1001/archotol.1948.00690030654006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G. CT findings associated with Eagle syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol 2001;22:1401–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babad MS. Eagle's syndrome caused by traumatic fracture of a mineralized stylohyoid ligament--literature review and a case report. Cranio 1995;13:188–92. 10.1080/08869634.1995.11678067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gokce C, Sisman Y, Ertas ET, et al. Prevalence of styloid process elongation on panoramic radiography in the turkey population from cappadocia region. Eur J Dent 2008;2:18–22. 10.1055/s-0039-1697348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss M, Zohar Y, Laurian N. Elongated styloid process syndrome: intraoral versus external approach for styloid surgery. Laryngoscope 1985;95:976–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilgüy M, Ilgüy D, Güler N, et al. Incidence of the type and calcification patterns in patients with elongated styloid process. J Int Med Res 2005;33:96–102. 10.1177/147323000503300110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann E, Räder C, Fuhrmann H, et al. Styloid-carotid artery syndrome treated surgically with Piezosurgery: a case report and literature review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2013;41:162–6. 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costantinides F, Vidoni G, Bodin C, et al. Eagle's syndrome: signs and symptoms. Cranio 2013;31:56–60. 10.1179/crn.2013.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Har-El G, Weisbord A, Sidi J. Ossified segments of the stylohyoid ligament. A case of radiological misdiagnosis. J Laryngol Otol 1987;101:516–8. 10.1017/S0022215100102117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han MK, Kim DW, Yang JY. Non Surgical Treatment of Eagle's Syndrome - A Case Report -. Korean J Pain 2013;26:169–72. 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.2.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papadiochos I, Papadiochou S, Sarivalasis E-S, et al. Treatment of Eagle syndrome with transcervical approach secondary to a failed intraoral attempt: surgical technique and literature review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017;118:353–8. 10.1016/j.jormas.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]