Abstract

Tuta absoluta is a major pest of tomato crops that causes high yield losses. Cultivated areas in Albania have reported high levels of infestations despite the application of control measures. The present study aims to describe population fluctuations of T. absoluta during tomato cultivation for three consecutive years in the winter–summer growing season under greenhouse conditions. Delta traps baited with pheromones were used to monitor the population fluctuations, and the appropriate treatment period was determined. The effectiveness of mass trapping, Indoxacarb and Bacillus thuringiensis treatments at maintaining the pest populations below the economic injury level was tested. Even under greenhouse conditions, the population levels were high during spring and peaked in summer. The infestation rate increased by up to 85% on leaves and fruit. The application of Bt, Indoxacarb, and mass trapping reduced the infestation rate on fruits by approximately 29%, 43% and 52%, respectively, which represented significant differences in effectiveness. In conclusion, the results indicate that performing an intervention that includes combined methods in the proper period might reduce the infestation rate from 80-95%.

Keywords: Tuta absoluta, Mass trapping, Bio-insecticides, Bacillus thuringiensis, Indoxacarb, Agricultural science, Crop protection, Crop yields, Insect pest management, Pesticide

Tuta absoluta; Mass trapping; Bio-insecticides; Bacillus thuringiensis; Indoxacarb; Agricultural science; Crop protection; Crop yields; Insect pest management; Pesticide.

1. Introduction

Tomato is a vegetable with high levels of production in the European Union (EU); the amount produced in 2018 was 16.7 million tons. Italy and Spain combined produce nearly two-third (62.9%) of the EU total (Eurostat, Agriculture, forestry and fishery statistics, 2019). Yield losses in tomato cultivation are caused by several pests, among which the tomato leaf miner Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Ghelechiidae) is a major pest. T. absoluta is spreading worldwide and has caused damage and losses in Mediterranean basin countries (EPPO, 2008; EPPO, 2009a; EPPO reporting service 2009b; Desneux et al., 2010; Abd El-Ghany et al., 2018). Young larvae (1st–2nd instar) bore into plants, and once mature (3rd–4th instar), they leave their bore holes and move to feed. If the food and climatic conditions are favorable, then the larvae feed almost continuously and generally do not enter diapause (Tropea Garzia et al., 2012). They attack leaves and flowers, mine stalks, apical buds, and green or ripe fruits, causing quality and yield losses of up to 100% if no control methods are applied (Apablaza, 1992; Viggiani et al., 2009). Indirect damage can often be manifested as a result of bacterial or fungal infections in organ galleries made by T. absoluta (Laore, 2018). Tomato may be attacked at any developmental stage in greenhouses or open fields, and infection may spread on different species of Solanaceae (EPPO, 2009c; Tropea Garzia et al., 2012). Chemical insecticides have been used to control T. absoluta, although because of their high reproductive capacity and short generation cycle, they have developed resistance to most of insecticides, as reported in other studies (Siqueira et al., 2000, 2001; Lietti et al., 2005). Moreover, the larval stage completes its development inside the leaf mesophyll; therefore, the larvae are not always directly exposed to insecticides. Indoxacarb is one of the few insecticides on registered lists, and it is used to control this pest in the EU (e.g., Spain and the Netherlands) (SEWG, 2008; Potting et al., 2013). This chemical is selectively effective at controlling outbreaks of T. absoluta (FERA, 2009; Sixsmith, 2009; USDA-APHIS, 2011). To our knowledge, in the Balkan region, no studies have been conducted on the field effectiveness of Indoxacarb against T. absoluta, although a study on its toxicity in tomato moth larvae was conducted by Roditakis et al. (2013).

Organic farming requires environmentally friendly strategies to control T. absoluta; therefore, bio-insecticides and other eco-friendly methods are being used. Bacillus thuringiensis formulations have been proven to be very efficacious against other Lepidopteran larvae (Lobesia botrana) in the central Albanian region (Shahini et al., 2010), and studies of their effectiveness against T. absoluta have been reported (Derbalah et al., 2012; Sabbour and Soliman, 2014; El-Aassar et al., 2015; Hashemitassuji et al., 2015; Abd El-Ghany et al., 2018). In addition to the use of Bt as an alternative to biological control, the use of parasitoids and predators (Trichograma spp. and mirids (N. tenuis & M. pygmaeus) are important control strategies in the context of IPM. However, construction of greenhouses (usually covered with plastic films) and climatic conditions in Mediterranean area, cause high diurnal temperature variation, thus resulting in a reduced activity of Trichogramma spp. parasites (Urbaneja et al., 2012; de Oliveira et al., 2017). Furthermore, application of insecticides affect the viability of these parasites (Fontes et al., 2018), making the latter unsuitable for inclusion in IPM programs. Usage of N. tenuis/M. pygmaeus with other biocontrol agents may reduce the application of chemical insecticides and therefore the selection of resistant populations but, this strategy is ineffective in greenhouses unscreened with insect proof net or in the presence of high level populations of T. absoluta (Giorgini et al., 2018). Delta traps baited with synthetic pheromone lures are used for male capture and accurately show whether the insect is present or when its seasonal flight period starts, and they are used to arrange the bio-pesticide application period (Witzgall et al., 2010; Caparros Medigo et al., 2013). Pheromones can also be used in pan traps and are particularly useful in the production of greenhouse tomatoes (Russell IPM, 2009; USDA-APHIS, 2011). Relevant studies about mass trapping effectiveness to control tomato leaf miner have been conducted by Filho et al. (2000), Goftishu et al. (2014), Braham (2014), Refki et al. (2016), and Abd El-Ghany et al. (2016).

Previous reports indicated that neither of the abovementioned methods when used alone led to the total control of T. absoluta, and IPM strategies are designed to maintain the pest within the economic injury level. Control practices in Mediterranean basin states affected by T. absoluta include different methods based on population densities. In Spain, mass trapping with pheromone-baited water traps is used at low population densities of 1–3 males/week; azadirachtin or Bt is applied for densities of 4–20 males/week; and Indoxacarb or Spinosad is recommended for high population densities of 30 males/week (SEWG, 2008). It is necessary to know the population fluctuation of T. absoluta (which varies based on climatic conditions and not only); therefore, the proper treatment period could be defined. While T. absoluta infest tomato cultivation worldwide, its population dynamics is strongly variable to different regions (depending on climatic conditions), thus requiring adaption of management protocols to respective areas (Giorgini et al., 2018).

Albania is part of the Mediterranean basin, and tomato is the most important cultivated vegetable in the country, accounting for up 25.2%, with the greenhouse-cultivated area larger than the field-cultivated area (Statistical Yearbook, Instat, 2017). Greenhouse surfaces account for approximately 1500 ha nationally, and they are mostly localized in the central-west region of the country (personal communication with the statistics office of Ministry of Food & Agriculture, Albania, 2018). Products are generally available in the market from April to December, with a peak in summer months. The first suspected symptoms of this pest were observed in 2008 by J. Tedeschini, although they were confirmed officially in 2009 in Durrës, Fier and Tirana County (EPPO Reporting Service, 2009d). The coastal area of Albania represents a medium-suitable region for the establishment of T. absoluta, with an Ecoclimatic Index of 25–50, depending on field locations along the shore (USDA-APHIS, 2011; Potting et al., 2013). These calculations were performed based on reports of Bentacourt et al. (1996) and Barrientos et al. (1998) and are linked to the temperatures required by the pest to progress to different life stages. Because temperature is the main limiting factor for the number of T. absoluta generations, greenhouses represent a more convenient environment for their development. Previous studies in similar climate conditions suggested that tomato leaf miner can reach 9–12 generations in plots with year-round tomato production (USDA-APHIS, 2011; Potting et al., 2013; (Laore, 2018). To control this pest, Albanian farmers have been routinely using chemical pesticides; however, significant improvements have not been made with regard to of pest control. Experiments have been carried out by the present authors, mostly in Durrës County, to provide insights on the population dynamics and help farmers intervene to prevent damage (Bërxolli and Shahini, 2017a; 2017b). To our knowledge, further studies have not been conducted on this pest in Albania, and no official control protocol exists.

The aim of the study was to understand the population fluctuations of T. absoluta inside tomato greenhouses under Albanian climatic conditions as well as to determine the treatment period. We also reported the effectiveness of the mass trapping method and Bt and Indoxacarb formulations for the direct reduction of damage caused by T. absoluta in leaves and fruits.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental site and greenhouse characteristics

The study was conducted in Imesht Village, Fier County (lat. 40ᵒ46′ N, long. 19ᵒ41’ E), and the study area was located near the central coastal region in an area of intensive greenhouse cultivation of tomato. The trials were carried out in three consecutive years from 2017–2019 in the tomato growing season (winter-summer). The area is characterized by a typical Mediterranean climate. The greenhouse was divided into two subdivisions, and the characteristics of the tomato cultivar in the greenhouse are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of greenhouse and tomato cultivars.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Greenhouse surface (m2) | 10.000 |

| Height above sea level (m) | 13 |

| Construction materials | Iron, plastic |

| Double door | No |

| Separation of subdivisions by net | Yes |

| Terrain | Silty clay, fertilized with manure |

| Tomato cultivar | Alamina RZ F1 (73–672) |

| Transplant date | January 20 |

| Plant density (plant/m2) | 2.8 |

| Previous culture | Tomato |

| Intercrop period (days) | 35 |

2.2. Bio-insecticides and pheromone traps

Indoxacarb formulations sold under the trade name Avaunt 15 EC were purchased from DuPont, USA. The concentration of the active ingredient was 15%, and the recommended application rate was 25 g/100 L water. The Bt var. kurstaki formulation sold under the trade name Delfin® WG was purchased from Syngenta. The concentration of the active ingredient was 53000 UC/mg at a dose of 75 g/hL/0.1 ha, and the recommended application rate was 100 g/100 L water. A mechanical pump sprayer with a capacity of 200 L (flat-fan nozzle, pressure of 5 atm, 0.5 mm in diameter) was used for the pesticide spray. Pheromone capsules used in the Delta traps and pan traps contained 0.5 mg (3E,8Z,11Z)-tetradecatrien-1-yl acetate and 0.024 mg (3E,8Z)-tetradecadien-1-yl acetate (production code: PH-937-1RR; Russell IPM). Delta traps were purchased from commercial sellers. Pan traps consisted of a plastic dish filled with water and a fixed pheromone bait.

2.3. Experimental design

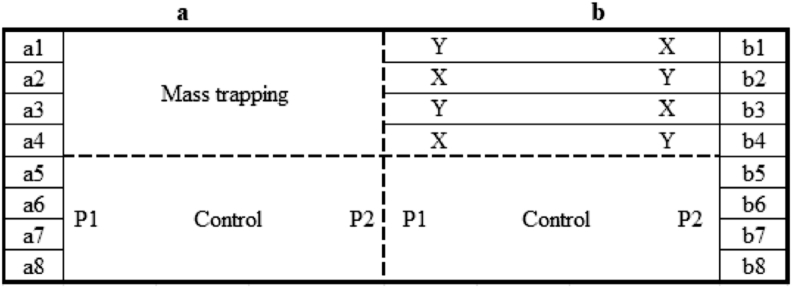

The main area of 1 ha was divided into two plots (split-plot), which were named subdivision a and subdivision b, and each had a surface of 0.5 ha. The two subdivisions (a and b) were divided into 8 strips (i.e., from a1-a8 and from b1-b8), and each had 3 rows (replicates) after the exclusion of side rows to eliminate border effects (Figure 1) (Shahini et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Experimental scheme (first year); X-Indoxacarb; Y-Bt; P1 and P2-Delta trap 1 and 2, respectively.

During the first year of the study, in a1-a4 strips, the mass trapping technique was used while the a5-a8 strips served as the control. The b1-b4 strips were treated with Bt var. kurstaki and Indoxacarb with randomization as indicated in Figure 1, while b5-b8 were left as the control strips. In the second year of the study, the a1-a4 strips were treated with Bt var. kurstaki and Indoxacarb with the same randomization inside the strips as in the first year, and a5-a8 were left as the controls. The b1-b4 strips used the mass trapping technique, and the b5-b8 strips served as the control. During the last year, the a1-a4 strips were left as the controls and the a5-a8 strips were treated with the mass trapping technique. Meanwhile, b1-b4 were used as a control and b5-b8 used Bt var. kurstaki and Indoxacarb formulations in the same randomization inside the strips as in other years. This method was performed to avoid the undesirable association between treatments and to minimize the carryover effect.

2.4. Installation of traps and bio-insecticide application

To detect the number of T. absoluta moths, four pheromone-baited Delta traps were installed at the same time seedlings were transplanted in the experimental area, and they were placed in different strips depending on the experiment year and always in the furthest of the treated plots (Figure 1, for the first year). These traps were checked and moths were counted on a regular weekly basis. When the first moths were observed in the Delta traps, baited pan traps with a density of 5 traps/0.25 ha were placed in a mass trapping plot (strips) as described by Caparros Medigo et al. (2013). Pan traps were uniformly distributed in the mass trapping plot at 0.3–0.8 m from the soil to prevent them from being covered by vegetation. Pheromone capsules were replaced every 4 weeks. To avoid the undesired effect of mass trapping adults from other treated strips, a distance of approximately 10 m separated the pan traps toward the border next to bio-insecticide-treated blocks of strips. To support noninterference, an insect-proof net was used to divide treatments (as indicated in Figure 1 with a dashed line).

In the first year, in the b1-b4 strips, 10 consecutive plants in each strip (in accordance with Figure 1) were treated with Avaunt 15 EC. The timing of the intervention for this pesticide was based on an economic threshold of 2 females per plant or 26 larvae per plant (Bajonero et al., 2008). For each pest generation, two treatments were performed, with application intervals of 14 days. The same procedure was performed in the following study years with randomization. In each of the b1-b4 strips, ten consecutive plants were treated with Bt var. kurstaki. For each pest generation, the first treatment was performed 4–5 days after the first flies were found on the Delta traps and the second was performed 8–10 days after the first treatment (SEWG, 2008; Shahini et al., 2010). The same protocol was followed in each of the study years. All treatments were applied in the morning (approximately 09:00) when the intensity of solar irradiation was low.

2.5. Damage evaluation and statistical analysis

To assess the damage caused by T. absoluta in tomato plantations, 100 leaves and fruits were randomly selected from the control and treatment strips and classified as damaged or healthy. This procedure was performed on a weekly basis from the time of the treatment and placement of pan traps to the uprooting time in July for each of the study years. Larvae may attack more than one fruit/leaf during their lifecycle; thus, the effectiveness of practical treatments was calculated using values of damaged/healthy fruits and leaves. Considering the direct economic damage, special attention is given to the fruit values. The corrected effectiveness (Ecorr) of the methods was calculated based on Abbott's formula (Abbott, 1925) and adapted for healthy or damaged fruits/leaves:

| (Ecorr) % = [1−(DL Treatment/DL Control)] x 100 | (1) |

| (Ecorr) % = [1−(DF Treatment/DF Control)] x 100 | (2) |

where DL is the mean number of damaged leaves and DF is the mean number of damaged fruits. The full dataset of the three years was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.20 for Windows, where the means were compared at the 0.05 probability level. An ANOVA and post hoc comparisons were performed to compare the mean effectiveness of treatments in the leaves and fruits.

3. Results

3.1. Population fluctuation

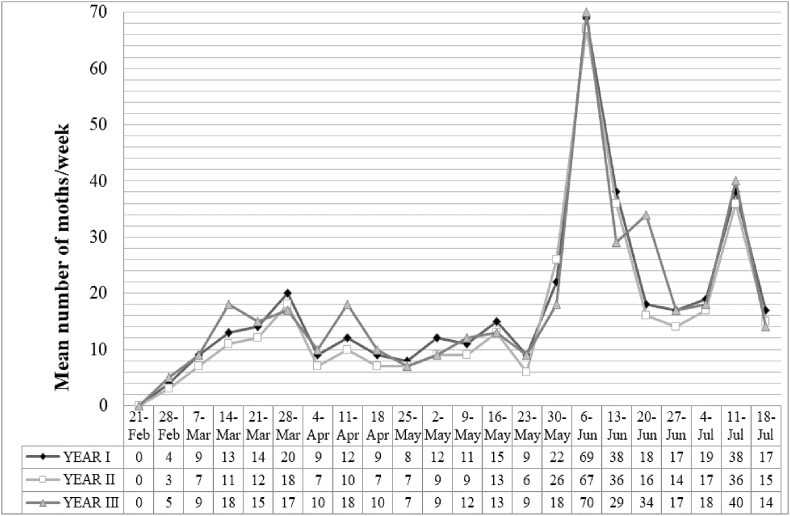

The data in Figure 2 were generated based on captured males in control strips on the Delta-type pheromone traps and show the evolution of population fluctuation during the period of tomato cultivation. Four generations were distinguished, with the primary generation starting at the third week of February (approximately one month after transplantation) and concluding before April 4. The peak of this generation was highest in the first year (20 moths), and in two of the three study years, it was reached between March 21 and 28. The second generation extended from the April 4 to the May 9, with the highest value recorded in the third year on the April 11. The third generation appeared after the May 9 and was characterized by a sharp increase to reach a high value of 70 males on the June 6. Subsequently, the number decreased rapidly over the last days of the generation (June 13). The fourth generation appeared from June 20 until July 18. The number of males captured rose gradually after June 27 and peaked for each of the years on July 11.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the T. absoluta population fluctuations in the greenhouse during the tomato cultivation period from February–July for three consecutive years.

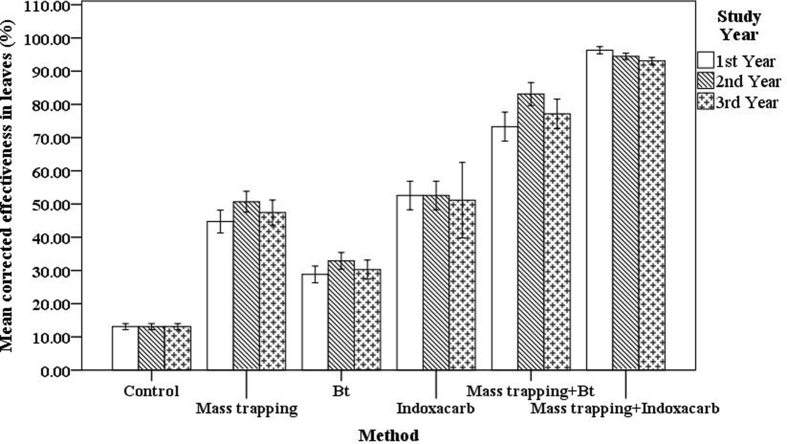

3.2. Effectiveness of the treatments on leaves

During the three consecutive study years, the level of infestation found in the leaves of control plants was higher than that in the treatments (Figure 3), and in every trial, the incidence of damage to leaves was significantly reduced by approximately 48%, 31% and 52% via mass trapping, Bt and Indoxacarb, respectively. Compared to the individual treatments, the theoretical combination of two methods (mass trapping + Bt) showed an increase in effectiveness from 1.5- to 2.5-fold (Figure 3). Compared to the individual treatments, the combination of mass trapping + Indoxacarb showed a 1.8-fold increase in effectiveness. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the effectiveness among the mass trapping, Bt, and Indoxacarb treatments and the combinations of mass trapping + Indoxacarb and mass trapping + Bt in with regard to the infestation level. Significant differences were observed between their effectiveness at the ∗P < 0.05 level for each of the study years: first year [F (5, 101) = 266.81, ∗∗∗P < 0.001]; second year [F (5, 101) = 307.54, ∗∗∗P < 0.001]; and third year [F (5, 98) = 103.27, ∗∗∗P < 0.001]. Post hoc comparisons of the first year using Tukey's HSD test indicated that the mean score for the mass trapping treatment (M = 44.7, SD = 7.5) was significantly different (∗∗∗P < 0.001) compared with the Bt treatment (M = 28.8, SD = 5.4) and Indoxacarb treatment (M = 52.6, SD = 9.1), and a significant difference was also observed between the latter two (∗∗∗P < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons of the second year using Tukey's HSD test indicated that the mean score for the mass trapping treatment (M = 50.6, SD = 6.9) was significantly different (∗∗∗P < 0.001) than that for the Bt treatment (M = 32.9, SD = 5.3) but was not different than that for the Indoxacarb treatment (M = 52.5, SD = 9.1) (∗P = 0.89); moreover, the Bt and Indoxacarb treatments were significantly different (∗∗∗P < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons of the third year using Tukey's HSD test indicated that the mean score for the mass trapping treatment (M = 47.4, SD = 8.3) was significantly different (∗∗∗P < 0.001) than that for the Bt treatment (M = 30.2, SD = 6.1) but was not different than that for the Indoxacarb treatment (M = 51.1, SD = 20.1) (∗P = 0.84); moreover, Indoxacarb was more effective than the Bt treatment (∗∗∗P < 0.001). Taken together, these results suggest that mass trapping is more effective than the Bt treatment but slightly less effective than Indoxacarb at reducing the incidence of leaf damage. Post hoc comparisons of the first year using Tukey's HSD test indicated that compared to mass trapping + Bt combination, the mean score for the theoretical combination of mass trapping + Indoxacarb (M = 96.28, SD = 2.36) was significantly higher (∗∗∗P < 0.001) (M = 73.29, SD = 9.35). Post hoc comparisons of the second year using Tukey's HSD test indicated that the mean score for the theoretical combination of mass trapping + Indoxacarb (M = 94.44, SD = 2.05) was significantly higher (∗∗∗P < 0.001) than that of mass trapping + Bt combination (M = 83.12, SD = 7.37). Post hoc comparisons of the third year using Tukey's HSD test indicated that the mean score for the theoretical combination mass trapping + Indoxacarb (M = 93.1, SD = 2.26) was significantly higher (∗∗∗P < 0.001) than that of the mass trapping + Bt combination (M = 77.13, SD = 9.51).

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of observed effectiveness on the leaves of control, single treatment plots and theoretical cumulative effectiveness of the combined methods (mass trapping + Bt and mass trapping + Indoxacarb). Control, single treatments and combinations were significantly different between them, by analysis of variance (P < 0.05) measures in each of the study year.

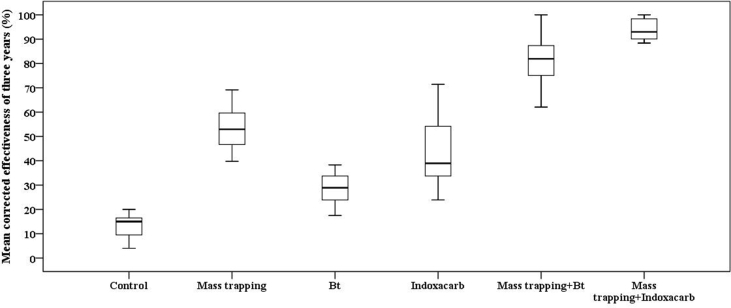

3.3. Effectiveness of treatments on fruits

Prior to comparing the means of the three-year analysis for the effectiveness of treatments in reducing infestations on fruits, one-way ANOVA tests were conducted to compare the year effect on the method effectiveness. Significant effects of study year on method effectiveness were not observed at the ∗P < 0.05 level: mass trapping: [F (2, 44) = 2.129, P = 0.131]; Bt: [F (2, 42) = 0.475, P = 0.625]; and Indoxacarb: [F (2, 42) = 0.295, P = 0.746]. The data in Figure 4 show the compared values of the mean effectiveness for the three treatments and the theoretical cumulative effectiveness of the two methods combined. A one-way ANOVA test was conducted to compare the effectiveness of different treatments in preventing fruit infestations. Significant differences were observed in treatment effectiveness at the ∗P < 0.05 level for the three treatments and two combinations [F (5, 286) = 799.4, ∗∗∗P < 0.001]. Post hoc comparisons using Tukey's HSD test indicated that compared to Indoxacarb (M = 42.75, SD = 12.43), the mean score of mass trapping (M = 52.76, SD = 7.8) for preventing fruit infestation was higher (∗∗∗P < 0.001), which is inconsistent with the results of the leaf analysis (Figure 4; Figure 3). Conversely, the Bt treatment showed the lowest level of effectiveness (∗∗∗P < 0.001) among the treatments (M = 28.96, SD = 5.62). The theoretical combination of methods showed that mass trapping + Indoxacarb (M = 93.64, SD = 4) was more effective (∗∗∗P < 0.001) than mass trapping + Bt (M = 81.77, SD = 10).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of observed three-year mean effectiveness on fruits of the control, single-treatment plots and theoretical cumulative effectiveness of the combined methods (mass trapping + Bt and mass trapping + Indoxacarb). Control, single treatments and combinations were significantly different between them, by analysis of variance (P < 0.05) measures.

4. Discussion

Semiochemicals are important tools in control strategies of various insects and include monitoring, mating disruption, luring and killing, mass trapping and push-pull strategies. Pheromones are considered promising and important components of IPM programs. They can be applied individually or integrated with other control agents for the monitoring and control of various insect pests (Abd El-Ghany, 2019). In the present study, Delta traps baited with pheromones were successfully used to monitor moths, and the treatment produced promising results. In a study from January to July, this pest had 4 generations, with an average days/generation of 34 ± 3 days. The data show that compared to the second generation, the first generation had a longer development period, and the development period was progressively shorter from generation to generation. As a result of rising temperatures, the insect progressed faster through its biological stages because of the accumulation of degree-day values. Similar results regarding the number of generations have been reported in Lebanon and Egypt by El Hajj et al. (2017) and Tabikha and Hassan (2015), who recorded shorter average generation periods (31.5 and 28.5 days/generation, respectively). This difference is possibly attributed to the warmer climate of these countries, where this pest concludes its cycle in a shorter period. The number of males captured in our study was highest in summer. With average temperatures ranging between 20 and 35 ᵒC in this season, a higher number of larvae hatch from eggs to progress to further development. These results are in agreement with those reported by Tabikha and Hassan (2015) and El Hajj et al. (2017). Introduced species generally have fewer natural enemies compared with native species (Torchin and Mitchell, 2004), and recent cases of invasive pests indicate that local antagonists need time to adapt to the invader, which leads to loss of production during this period (Giorgini et al., 2018).

The results indicated that in plots where pan traps were placed, the infestations of leaves and fruits were significantly reduced compared to the control plots. Furthermore, the mass trapping technique showed an approximately 1.5-fold higher effectiveness in the leaves and 1.8-fold higher effectiveness in the fruits compared with the Bt treatment. Its effect was slightly less than that of Indoxacarb with regard to reducing leaf damage, although it demonstrated a higher effectiveness in fruits. Indoxacarb acts through direct contact with larvae; therefore, the longer it stays on the organs, the higher the efficacy. Because of the organs' physical form, it persists longer in leaves than in fruits, which may partially explain the differences between the two treatments’ efficacy in different plant organs. These results are not uncommon. Regarding the different results in leaves and fruits, Balzan and Moonen (2012) reported that there was no correlation between the numbers of galleries in leaves and damaged fruits.

Indoxacarb and Bt are both included in lists of protocols approved for T. absoluta control (SEWG, 2008 in Spain; IRAC, 2009 in Argentina; Mallia, 2009 in Malta; FREDON, 2009 in France; USDA-APHIS, 2011). Reports from various authors present contradictory results regarding the effectiveness of Indoxacarb and Bt. Derbalah et al. (2012) reported that Indoxacarb had higher efficacy than Bt, while a study conducted by Nazarpour et al. (2016) reported the opposite results. In the present study, Indoxacarb was more effective than Bt at reducing the infestation in tomato leaves/fruits. Although Indoxacarb has good efficacy, it is an insecticide; therefore, its application is recommended for high population densities.

Control through mass trapping alone cannot keep the damage level below that of economic injury; thus, it must be combined with other measures, such as double doors or nets (Chermiti et al., 2009; Harbi et al., 2012). Moreover, males are captured in pan traps while females can reproduce parthenogenetically (Caparros Medigo et al., 2012). On the other hand, Bt and Indoxacarb have limited efficacy, which is likely because the larval stage proceeds for a time within the plant tissue, and direct contact does not occur. Moreover, Bt and Indoxacarb may also be biodegraded over time, which limits their efficacy when used alone. The infestation rate (fruits) in each of the single treatments varied between 30 and 50%, which led to high yield losses. The theoretical cumulative effectiveness of mass trapping + Bt and mass trapping + Indoxacarb ranged between 80 and 100% in leaves and fruits; therefore, these treatments could be considered potential strategies under field or greenhouse conditions based on the period of application. Moreover, we suggest that they be included in country protocols to control this pest. The application of IPM strategies that include the augmentation of parasitoids, application of mirids, and usage of pheromones and bio-insecticides constitutes an effective basis for the control of T. absoluta. Moreover, certain strategies, such as parasitoids and predators, are effective under specific conditions (climatic conditions, low-density populations and insect-proof net cover). To integrate various techniques and methods, the compatibility must be ensured and the population density of the pest must be considered.

5. Conclusions

Experimental trials conducted over three years showed that T. absoluta has a high population density and can cause serious damage in protected areas of tomato cultivation in Albania. Infestations are persistent over time, and greenhouse conditions are suitable for pest development in the country. Mass trapping, Bt and Indoxacarb significantly reduced infestations in the leaves and fruits but could not maintain the population below the economic injury level when used individually. Indoxacarb was more effective than Bt but less effective than mass trapping in reducing infestation in fruits. We recommend the use of mass trapping in combination with a bio-insecticide, insect-proof net and/or double doors. To ensure maximal effectiveness, IPM strategies must always be applied based on the population dynamics.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Shpend Shahini, Ajten Bërxolli, Frans Kokojka: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Agricultural University of Tirana, Faculty of Agriculture and Environment, Plant Protection Department, Albania, Eco Green sh.p.k. and Meldi sh.p.k., Tirana, Albania, Albaseed, Lushnje Albania & Sakaj Export.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abbott W.S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925;18:265–267. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Ghany N.M., Abdel-Wahab E.S., Ibrahim S.S. Population fluctuation and evaluation the efficacy of pheromone-based traps with different color on tomato leafminer moth, Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Egypt. Res. J. Pharmaceut. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:1533–1539. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Ghany N.M., Abdel-Razek A.S., Djelouah K., Moussa A. Efficacy of some eco-friendly biopesticides against Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) Biosci. Res. 2018;15:28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Ghany N.M. Semiochemicals for controlling insect pests. J. Plant Protect. Res. 2019;59:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Apablaza J. La polilla del tomate y su manejo Tattersal. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 1992;79:12–13. (In Spanish with English summary) [Google Scholar]

- Bajonero J., Cordoba N., Cantor F., Rodriguez D., Cure J.R. Biologıa y ciclo reproductivo de Apanteles gelechiidivoris (Hymenoptera: braconidae), parasitoide de Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Agro. Colomb. 2008;26:417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Balzan M.V., Moonen A.C. Management strategies for the control of Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) damage in open field cultivations of processing tomato in Tuscany (Italy) Bull. OEPP/EPPO Bull. 2012;42:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos Z.R., Apablaza H.J., Norero S.A., Estay P.P. Threshold temperature and thermal constant for development of the South American tomato moth Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) Cienc. Investig. Agrar. 1998;25:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bentacourt C.M., Scatoni I.B., Rodriguez J.J. Influence of temperature on reproduction and development of Scrobipalpuloides absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) Rev. Bras. Biol. 1996;56:661–670. [Google Scholar]

- Berxolli A., Shahini Sh. Population dynamic of tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelichiidae) Albanian J. Agric. Sci. 2017:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Berxolli A., Shahini Sh. Friendly using methods for controlling of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelichiidae) J. Multi. Sci. Tech. 2017;4:8171–8175. [Google Scholar]

- Braham M. Sex pheromone traps for monitoring the tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta: effect of colored traps and field weathering of lure on male captures. Res. J. Agri. Environ. Manag. 2014;3:290–298. [Google Scholar]

- Caparros Megido R., Haubruge E., Verheggen F.J. First evidence of deuterotokous parthenogenesis in the tomato leafminer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lep., Gelechiidae) J. Pest. Sci. 2012;85:409–412. [Google Scholar]

- Caparros Medigo R., Haubruge E., Verheggen F.J. Pheromone-based management strategies to control the tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). A review. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2013;17:475–482. [Google Scholar]

- Chermiti B., Abbes K., Aoun M., Ben Othmane S., Ouhibi M., Gamoon W., Kacem S. First estimate of the damage of Tuta absoluta (Povolni) (Lepidoptera: Ghelechiidae) and evaluation of the efficiency of sex pheromone trap in greenhouses of tomato crops in the Bekalta region, Tunisia. Afr. J. Plant Sci. Biotechnol. 2009;1:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Desneux N., Wajnberg E., Wyckhuys K., Burgio G., Arpaia S., Narva´ez-Va´squez C., Gonza´lez-Cabrera J., Ruescas D.C., Tabone E., Frandon J., Pizzol J., Poncet C., Cabello T., Urbaneja A. Biological invasion of european tomato crops by Tuta absoluta: ecology, history of invasion and prospects for biological control. J. Pest. Sci. 2010;83:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira C.M., Vargas, de Oliveira J., Rafael D., Barbosa S., Oliveira Breda M., de França S.M., Ribeiro Duarte B.L. Biological parameters and thermal requirements of Trichogramma pretiosum for the management of the tomato fruit borer (Lepidoptera: crambidae) in tomatoes. Crop Protect. 2017;99:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Derbalah A.S., Morsey S.Z., El-Samahy M. Some recent approaches to control Tuta absoluta in tomato under greenhouse conditions. Afr. Entomol. 2012;20:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- El-Aassar M.R., Soliman M.H.A., Abd Elaal A.A. Efficiency of sex pheromone traps and some bio and chemical insecticides against tomato borer larvae, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) and estimate the damages of leaves and fruit tomato plant. Ann. Agric. Sci. (Cairo) 2015;60:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- El Hajj A.K., Rizk H., Gharib M., Houssein M., Talej V., Taha N., Aleik S., Mousa Z. Management of Tuta absoluta Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) using biopesticides on tomato crop under greenhouse conditions. J. Agric. Sci. 2017;9:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO [European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization] EPPO Reporting Service; 2008. Additional Information provided by Spain on EPPO A1 pests. (ESTa/2008-01) [Google Scholar]

- EPPO [European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization] EPPO Reporting Service; 2009. First Report of Tuta absoluta in France. 2009/003. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO [European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization] EPPO Reporting Service; 2009. Tuta absoluta Reported for First Time from Lazio Region Italy. 2009/106. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO [European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization] Tuta absoluta found on Phaseolus vulgaris in Sicilia (IT) EPPO Rep. Service. 2009;8:3. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO [European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization] 2009. Reporting Service No. 09 – 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat, Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Statistics. 2019. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- FERA [Food and Environment Research Agency] Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs; 2009. South American Tomato Moth Tuta absoluta.http://www.fera.defra.gov.uk/plants/plantHealth/pestsDiseases/documents/ppnTutaAbsoluta.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Filho M.M., Vilela E.F., Attygalle A.B., Meinwald J., Svatosˇ A., Jham G.N. Field trapping of tomato moth, Tuta absoluta with pheromone traps. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000;26:875–881. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes J., Sanchez Roja I., Tavares J., Oliveira L. Lethal and sublethal effects of various pesticides on Trichogramma achaeae (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2018;111:1219–1226. doi: 10.1093/jee/toy064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDON-Corse [Fédération Régionale de Défense Contre les Organismes Nuisibles de Corse] 2009. Mesures de Lutte Contre Tuta absoluta.http://www.fredoncorse.com/standalone/1/CE5Bk98q7hNOOAd4qo4sD67a.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Giorgini M., Guerrieri E., Cascone P., Gontijo L. Current strategies and future outlook for managing the Neotropical tomato pest Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) in the Mediterranean Basin. Forum Paper. Neotrop, Entomol. 2018;48:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s13744-018-0636-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goftishu M., Seid A., Dechassa N. Occurrence and population dynamics of tomato leaf miner [Tuta absoluta (Meyrick), (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae)] in Eastern Ethiopia. East Afr. J. Sci. 2014;8:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Harbi A., Abbes K., Chermiti B. Evaluation of two methods for the protection of tomato crops against the tomato leaf miner Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) under greenhouses in Tunisia. EPPO Bull. 2012;42:317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemitassuji A., Safaralizadeh M.H., Aramideh Sh., Hashemitassuji Z. Effects of Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki and Spinosad on three larval stages 1st, 2nd and 3rd of tomato borer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in laboratory conditions. J. Archi. Phyto. Plant Protec. 2015;48:377–384. [Google Scholar]

- IRAC [Insecticide Resistance Action Committee] IRAC Newsletter; 2009. Tuta absoluta on the move.http://www.irac-online.org/documents/connectionissue20a.pdf Connection (20) [Google Scholar]

- Laore . Guida al riconoscimento e lotta alla Tignola del pomodoro Tuta absoluta. 2018. Agenzia regionale per lo sviluppo in agricoltura; pp. 2–4.http://www.sardegnaagricoltura.it/documenti/14_43_20180507164728.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lietti M.M.M., Botto E., Alzogaray R.A. Insecticide resistance in Argentine populations of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) Neotrop. Entomol. 2005;34:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Mallia D. Plant Health Department; Malta: 2009. Guidelines for the Control and Eradication of Tuta absoluta. Ministry of Resources and Rural Affairs.http://www.agric.gov.mt/plant-health-deptprofile [Google Scholar]

- Nazarpour L., Yarahmadi F., Saber M., Rajabpour A. Short and long-term effects of some bio-insecticides on Tuta absoluta Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) and its coexisting generalist predators in tomato fields. J. Crop Protec. 2016;5:331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Potting R., van der Gaag D.J., Loomans A., van der Straten M., Anderson H., MacLeod A., Castrillón J.M.G., Cambra G.V. Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Plant Protection Service of the Netherlands; 2013. Tuta absoluta, Tomato leaf miner moth or South American tomato moth. [Google Scholar]

- Refki E., Sadok B.M., Ali B.B., Faouzi A., Jean V.F., Caparros Medigo R. Effectiveness of pheromone traps against Tuta absoluta. J. Entomol. and Zool. Studies. 2016;4:841–844. [Google Scholar]

- Roditakis E., Skarmoutsou C., Staurakaki M., Mart´ınez-Aguirre M.R., Garc´ıa-Vidal L., Bielza P. Determination of baseline susceptibility of European populations of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) to indoxacarb and chlorantraniliprole using a novel dip bioassay method. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013;69:217–227. doi: 10.1002/ps.3404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IPM Ltd . 2009. Tuta absoluta-insect Profile Russell IPM Ltd.http://www.tutaabsoluta.com/insectprofile.php?lang=en [Google Scholar]

- Sabbour M.M., Soliman N. Evaluations of three Bacillus thuringiensis against Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Egypt. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014;3:2067–2073. [Google Scholar]

- SEWG . 2008. Spanish Expert Working Group in Plant Protection of Horticultural Crops. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira H.Á.A., Guedes R.N.C., Picanço M.C. Insecticide resistance in populations of Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) Agric. For. Entomol. 2000;2:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira H.A.A., Guedes R.N.C., Fragoso D.B., Magalhães L.C. Abamectin resistance and synergism in Brazilian populations of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) Int. J. Pest Manag. 2001;47:247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Shahini Sh., Kullaj E., Ҫakalli A., Ҫakalli M., Lazarevska S., Pfeiffer D.G., Gumeni F. Population dynamics and biological control of European grapevine moth (Lobesia botrana) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) in Albania using different strains of Bacillus thuringiensis. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2010;56:281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sixsmith R. Horticulture; 2009. Call for Integrated Pest Management as Mediterranean Tomato Pests Spread to UK.http://www.hortweek.com/news/search/943628/Call-integrated-pest-management-%20Mediterranean-tomato-pests-spread-UK/ Week (October 9, 2009) [Google Scholar]

- Statistical yearbook, Instat. 2017. pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Tabikha R.M.M., Hassan A.-N.T. Annual generations and population fluctuation of tomato leaf miner moth Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in El-Behera Governorate, Egypt. Egypt. Acad. J. Biolog. Sci. 2015;8:141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Torchin M.E., Mitchell C.E. Parasites, pathogens, and invasions by plants and animals. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004;2:183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Tropea Garzia G., Siscaro G., Biondi A., Zappalà L. Tuta absoluta, a South American pest of tomato now in the EPPO region: biology, distribution and damage. Bull. OEPP/EPPO Bull. 2012;42:205–210. [Google Scholar]

- USDA-APHIS . United States Department of Agriculture; Washington, DC: 2011. New Pest Response Guidelines Tomato Leaf Miner (Tuta absoluta)https://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/plants/manuals/emergency/downloads/Tuta-absoluta.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Urbaneja A., González-Cabrera J., Arnó J., Gabarra R. Prospects for the biological control of Tuta absoluta in tomatoes of the Mediterranean basin. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012;68:1215–1222. doi: 10.1002/ps.3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viggiani G., Filella F., Delrio G., Ramassini W., Foxi C. Tuta absoluta, nuovo lepidottero segnalato anche in. Italia. L’Informat. Agr. 2009;65:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Witzgall P., Kirsch P., Cork A. Sex pheromones and their impact on pest management. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010;36:80–100. doi: 10.1007/s10886-009-9737-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.