Abstract

Recently, the increasing emergency of traffic accidents and the unsatisfactory outcome of surgical intervention are driving research to seek a novel technology to repair traumatic soft tissue injury. From this perspective, decellularized matrix grafts (ECM-G) including natural ECM materials, and their prepared hydrogels and bioscaffolds, have emerged as possible alternatives for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Over the past decades, several physical and chemical decellularization methods have been used extensively to deal with different tissues/organs in an attempt to carefully remove cellular antigens while maintaining the non-immunogenic ECM components. It is anticipated that when the decellularized biomaterials are seeded with cells in vitro or incorporated into irregularly shaped defects in vivo, they can provide the appropriate biomechanical and biochemical conditions for directing cell behavior and tissue remodeling. The aim of this review is to first summarize the characteristics of ECM-G and describe their major decellularization methods from different sources, followed by analysis of how the bioactive factors and undesired residual cellular compositions influence the biologic function and host tissue response following implantation. Lastly, we also provide an overview of the in vivoapplication of ECM-G in facilitating tissue repair and remodeling.

Keywords: extracellular matrix grafts, decellularization protocols, tissue engineering, the host response

1. Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) derived from organs/tissues is a complex, highly organized assembly of macromolecules with an adequate three-dimensional (3D) organization (1). Dry ECM powders can be further processed to generate various injectable hydrogels by enzymatical digestion. To match tissue defects and improve therapeutic outcomes, these ECM-hydrogels have been combined with synthetic materials to fabricate electrospun nanofibers or 3D-printed scaffolds/conduits via electrospinning technology or 3D printing. The prepared hydrogels or solid scaffolds can seed with stem cells and/or incorporate with growth factors (GFs) to further enhance their bioactivity and repair function. These extracellular matrices and their final products are all termed as the decellularized matrix grafts (ECM-G) or the ECM preparations (ECM-P). In addition to regulating intracellular signaling pathways for inducing cell adhesion, these biologic ECM-P also provide a permissive environment for cell growth, proliferation, migration and differentiation, which have widely applied for the therapeutic reconstruction in heterologous tissue disorder (2). Commonly, ECM-P consists of a complex mixture of structural and functional proteins, including collagen, fibronectin, laminin, glycosaminoglycans, and growth factors (GFs). Besides abundant bioactive factors, its inherent cross-linked polymeric network and suitable mechanical property, not only provides physical support for tissue integrity and elasticity, but also modulates the wound healing response towards tissue remodeling (3,4). Additionally, ECM-P has been used in various forms, such as scaffold incorporated with stem cells and/or GFs, and even as a bioink for constructing 3D-printed conduits, which have been implanted in virtually every body system (5).

Injectable materials prepared from untreated raw ECM frequently invoke chronic inflammatory response and host foreign body reaction in a variety of body systems, due to residual immunogenicity components, such as Galactose-α(1,3)-galactose (α-gal), major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I), endotoxins and cell-derived nucleic acids (6). Additionally, some pathogenic contaminations contained in the biological ECM material may also provoke severe immune rejection and foreign body response in preliminary xenografts (7). They are divided into two major categories: Viral particles/elements and salmonella (8). The former is particularly problematic in terms of xenozoonoses, including brucellosis, leptospirosis, and tularellosis. The latter mainly refers to prions, which are derived from xenogeneic and allogeneic tissue sources (9). Thus, the objective on any decellularization process is maximizing the removal of these residual pathogenic contaminants or extracellular antigen molecules, while retaining the functional performance of non-immunogenic ECM and maintaining its native ultrastructure and mechanical strength. Currently, the most commonly utilized methods for decellularization of xenogeneic and allogeneic tissues involve physical, chemical, and enzymatic approaches (10). The choice of these decellularization approaches (single or combined method) depends on the complex intrinsic structure, composition, and mechanical properties of the raw ECM (11). Following the decellularization and solubilization of raw ECM, the resulting ECM-P should still retain the tissue-specific composition and nanostructure that are essential in contributing to ischemic injury repair, tissue regeneration or organ replacement.

The use of ECM grafts (ECM-G) for tissue engineering and drug delivery has already been broadly investigated (3). The ideal ECM-G for regenerative medicine should be clear of cell residues from the tissue source, and comprises a loosely organized nanofibrous architecture with interconnecting pores, which are essential for nutrient and gas exchange for healthy cell migration and growth (12). In addition to having biocompatible, biodegradable, and adequate biomechanical properties, the ECM-G should also display appropriate visco-elasticity and match the permeability property of the autologous homologous tissue (13). Moreover, the proteolytic turnover of grafted ECM should match the rate of new tissue formation in order to withstand mechanical stress from neighboring tissues during the regeneration period (14,15). Furthermore, ECM-G has been developed as a delivery vehicle for incorporating GFs and/or cells to enhance the repair and regeneration of the damaged tissues and holds promising potential for improving the therapy of traumatic diseases.

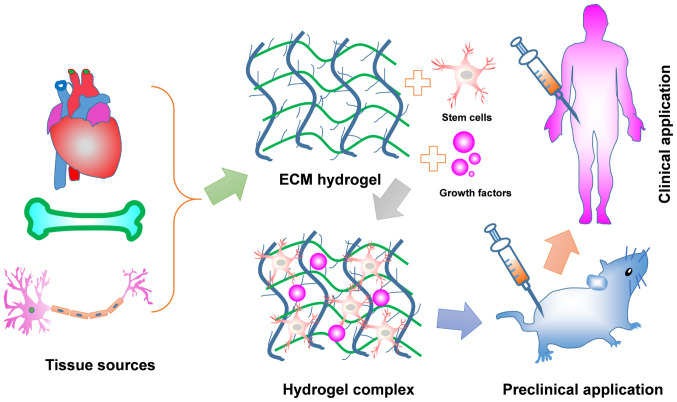

In this review, we firstly provide an overview of the unique properties of ECM-G and different decellularization methods for achieving sufficient cell removal from source tissues. Then, we discuss the effect of undesired residual cellular material invoking the degree of immune response. Finally, applying ECM-G for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine will be discussed, including current limitations and future directions (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of ECM hydrogel from preparation to application. The native tissues can achieve a diversity of ECM hydrogels via combination of physical, chemical and biological approaches together. The prepared ECM hydrogels themselves with/without incorporating growth factors and/or stem cells are used for tissue repair and regeneration, including spinal cord injury, peripheral nerve injury and myocardial infarction. Some of these may become a primary option for remodeling a variety of clinical tissues defects.

2. ECM-G characterization

ECM-G is a class of naturally derived proteinaceous biomaterials, with excellent biophysical, biomechanical, and biochemical properties, which can provide biological signals and maintain tissue microarchitecture for guiding on cell growth, differentiation, neovascularization and functional improvement (16). It has been shown that collagen and elastin, both of which are the most abundant proteins in the ECM-G, played a critical role in controlling tissue osmotic pressure and regulating intracellular signaling cascades that direct stem cell differentiation and function (17,18). Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are also regarded as important associated macromolecules found in the ECM-G, as they generally served as crosslinkers for carrying GFs because their binding sites are highly negatively charge, leading to high affinity to cationic GFs (19). Thus, ECM-G also serve as a drug delivery vehicle for the controlled release of GFs in a spatial and temporal manner when applied in pre-clinical research. Moreover, their thermo-responsive feature is suitable for injecting a cavity site of damage via a catheter or syringe. In addition, the three-dimensional cross-linked network of fibers is another feature that renders them capable of holding large amounts of water. Although the pore size, fiber diameter and fiber alignment of ECM-G vary from different source tissue, its typical nano-scale topography is enough to be sensed and manipulated by infiltrating cells (20). The viscoelastic property of ECM-G is another important parameter for evaluating stiffness and solid-like behavior, which can be accurately determined by turbidimetric gelation kinetics and rheology. A suitable viscosity of the pre-gel solution is favorable for supporting stem cell differentiation and proliferation for in vitro culture and promoting the constructive and functional outcome of tissues and organs. For example, the 3D meniscus-derived hydrogel with storage modulus (a typical index for reflecting viscosity) of 838±296 Pa (12 mg/ml) showed good cellular compatibility by facilitating the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into nucleus pulposus-like cells after culturing for 2 weeks (21). In vivo examination of a low viscosity ECM hydrogel derived from porcine spinal cord showed that it remained within the defect site at body temperature (37°C) condition which stimulates neovascularization and axonal outgrowth into the cavity site of the acute model of spinal cord injury (SCI) (22).

The different matrix density of various hydrogels, including water content and macromolecular density, is mainly dependent on tissue sources and status (23). Generally, hydrogel composition and density play important roles in regulating cell activity and phenotype (24). The abundant water content filling the space between hydrogel crosslinks allows for the diffusion of solute molecules. Bio-activate molecules, such as GFs, proteoglycans and collagens, are necessary for the activation of intracellular signaling cascades through integrin receptors to induced cell adhesion, migration, proliferation and differentiation (1). Thus, an ideal natural hydrogel should retain several distinct ECM macromoleculars as much as possible and contain water with proper proportion in case of reduced mechanical force and viscoelastic property for the prepared hydrogel products. Preclinical rodent studies using porcine-derived urinary bladder matrix (UBM)-ECM hydrogel with the concentration of 8 mg/ml implanted into a 14-day-old stroke cavity induced a robust invasion of endothelial cells with neovascularization for brain regeneration (25). Further research will focus on optimizing the matrix density of various hydrogels to open new therapeutic avenues for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Overall, these topological, biochemical and mechanical properties of the ECM-G are essential for modulating diverse fundamental aspects of cell biology and functional outcomes in disease models. Generally, the intrinsic property of a specific ECM-G is mostly determined by the source of tissue type and species. However, the optimal decellularization method is critical for the resulting ECM quality concerning ultrastructure and molecular composition (26). Thus, successful procedures for ECM preparations must relate to the tissue of origin, comprehensively utilizing physical, chemical and biological methods to remove cellular material as much as possible, while retaining the ECM biopolymer components.

There are extensive molecular changes occurring in the ECM including post-translational modification (e.g., glycosylation), proteolytic processing, crosslinking, assembling into polymers and higher complex structures. All these processes are crucial for ECM properties and function, turnover and stability, as well as cellular interactions. These modifications solve the specific issue of different diseases. For instance, it has been shown that ECM proteins, such as collagen, contained in the subendothelial basement membrane could activate platelets, leading to thrombosis at the site of anastomosis during vascular surgery (27). To overcome this shortcoming, chemically modified vascular ECM was developed via covalently immobilizing anticoagulant heparin onto the ECM using collagen binding peptide (CBP) as an intermediate linker that selectively binds collagen within ECM. This heparin-modified ECM exhibits beneficial effects on reducing long-term thromboresistance and targeting VEGF to facilitate the adhesion and growth of endothelial cells (28). Another representative study by Li et al identified nanofiber-hydrogel modification for repairing SCI (29). They engineered an injectable nanofiber-hydrogel composite (NHC) by covalently conjugating hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel with electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL) fibers. This unique bonding resulted in a structure that possessed mechanical strength and porosity to prevent contused spinal cord collapse and induce cellular migration within the injury site. After injecting this NHC into the cavity region of an adult rat with spinal cord contusion, macrophage polarization, vascularization, neurogenesis and axonal growth became significantly ameliorated at 28 days treatment.

3. Methods of decellularization treatments

Decellularization has become a popular technique for transforming different organs, such as the skin, heart, liver, kidneys, muscle, sis mucosa, nerves, tendons, ligaments and blood vessel, into bioactive ECM-G through physical and/or chemical processing (30). Since different organs or tissues have their unique compositions and mechanical behavior which are closely associated with regulating cell behavior and tissue regeneration, these unique compositions and inherent property must be retained as much as possible during decellularization to obtain the biologic ECM-G (10). Several popular methods have been examined for performing decellularization, which can be mainly classified as physical, chemical and biological approaches (31). These decellularization methods require various decellularization agents that involve specific purpose, extent, influence factor and effect on ECM (Table I). A complete decellularization process should combine these approaches together, that is, firstly destroying the cell membrane via physical shaking or ionic detergents, followed by solubilization of cytoplasmic and nuclear cellular components using sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and sodium deoxycholate, and finally digestion of the extracellular matrix into a homogeneous gel by trypsin, dispase and phospholipase. Furthermore, this effective removal of cellular components is able to achieve further improvement through coupling with mechanical agitation. Nevertheless, it should be highlighted that the entire removal of cytoplasmic and nuclear components while preserving the entire/native extracellular matrix entities and structure is an extremely difficult task. The optimal recipe of decellularization agents is dependent upon different specific tissues, as well as the intended clinical application (32). Several decellularization methods have been developed for a variety of tissues (Table II) and these will be reviewed in the following sections.

Table I.

Selected agents and techniques for decellularizing tissue.

| Methods/Refs. | Characteristics | Effects on ECM |

|---|---|---|

| Snap freezing (103-105) | Decellularization of tendinous, ligamentous tissue and nerve tissue Usually combined with complement chemical and enzymatic techniques Affected by temperature |

Disruption of cellular membranes and inducing cell lysis |

| Mechanical sonication (106,107) | Tissues with hard structures Usually combined with complement chemical and enzymatic techniques Affected by mechanical frequency and amplitude |

Largely damage the ECM structure |

| Mechanical agitation (44,108) | Removal of cellular contents Usually combined with complement chemical and enzymatic techniques Affected by the speed and length of mechanical agitation |

Direct damage to ECM |

| Triton X-100 (109-111) | Removing nuclear and cytoplasmic waste Mixed results with efficacy Dependent on tissue Affected by exposure time, temperature, and concentration |

More effective cell removal from thin tissues Mild disruption of ultrastructure and removal of GAG |

| SDS (45,112,113) | Applying for retaining the overall matrix structure Very effective for removal of cellular components from tissue Affected by exposure time, temperature, and concentration |

Removes nuclear remnants and cytoplasmic proteins |

| Sodium deoxycholate (114-116) | Very effective for removing cellular remnants Causing disruption to the native tissue architecture Affected by exposure time, PH and concentration |

Damages the matrix, similar to the SDS |

| CHAPS (44,117) | Cell removal from thinner tissues, such as blood vessels and lung 95% removal efficiency of nuclear materials Affected by pH and concentration |

Effectively removes cells in thin tissues and mildly disrupts ultrastructure in thin tissues |

| Trypsin (47,48) | Specifically target ECM proteins Strongly damage the ECM proteins collagen laminin, and fibronectin Affected by exposure time, temperature, pH and concentration |

Digestion of the proteins in the ECM, in particular collagen laminin, and fibronectin |

| Pepsin (118,119) | Generally target ECM proteins Milld damage the ECM proteins collagen laminin, and fibronectin Affected by exposure time, temperature, pH and concentration |

Damage ECM proteins if digested too long |

| Lipase (120,121) | Specifically targets lipids Strongly efficiency Affected by exposure time, temperature, pH and concentration |

Hydrolyzing fat to derive adipose derived ECM |

| Collagenases (123) | Specifically targets collagen at early step Strongly efficiency Affected by exposure time, temperature, pH and concentration |

Effectively removes collagen in ECM; Prolonged expose will disrupt ECM ultrastructure |

| Nucleases (123,124) | Specifically break down DNA or RNA sequences Highly efficiency Affected by temperature, pH and concentration |

No function on ECM proteins; Only removal of nucleotides |

SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; CHAPS, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate; GAGs, glycosaminoglycans.

Table II.

Applications of different organ decellularization techniques to various organs.

| Organ | Decellularization agent | Solubilization protocol | Species | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | 10 U/ml heparinized water 5.0% SDS 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 |

10X PBS RT, 48 h |

Porcine | (125) |

| Lung | 0.0035% Triton-X 100 0.1% SDS 0.1% potassium laurate |

Perfusion 1.5 mg/ml pepsin |

Rat | (126) |

| Liver | 4% Triton X-100 10 mM Tris-HCl 0.25% trypsin |

Voytik-Harbin 10 mg pepsin |

Rat | (127) |

| Kidney | Gradient of SDS (0.5%-1.0%) 0.1% Triton X-100 |

Perfusion 0.1 M HCl |

Rat | (128) |

| Skin | 1% SDS and 0.5% pen/strep Isopropyl alcohol 0.001% Triton X-100 |

Perfusion 0.1 M HCl |

Murine | (30) |

| Nerve | 3.0% Triton X-100 4.0% SDS |

0.01 M HCl 0.1 M NaOH |

Porcine | (84) |

| Skeletal muscle | 0.7% NaCl 1% Triton X-100 70% ethanol |

Perfusion 0.02 M HCl 24 h |

Mouse | (129) |

Perfusion involved i) Triton X-100 + SDS; ii) stir plate, RT, at least 48 h; iii) neutralized to pH 7.4 and physiological salt with NaOH and 10X PBS.

Physical methods

A variety of physical methods, such as freezing, mechanical agitation and sonication, have been frequently applied to facilitate tissue decellularization. Snap freezing has been used to disrupt cell-cell and cell-matrix bonds via the formation of intracellular ice crystals (33). After rapidly reducing the temperature of a tissue to the freezing point, cell lysis occurred immediately, facilitating the removal of immunogenic material from the tissue. However, it should be noted that the rate of temperature change for special tissue must be carefully controlled to protect matrix integrity from ice crystals disruption. Similarly, mechanical agitation is another effective method for conducting cell lysis using a magnetic stir plate or an orbital shaker (34). However, for tissue from the small intestine and the urinary bladder, mechanical agitation alone is not sufficient to completely remove intracellular contents and immunogenic macromolecules due to the fragility of the organs and their internal structural complexity. Thus, this technology is only used at the beginning of the decellularization protocol to enhance the efficacy of further efforts to clear cellular debris from the tissue. Sonication is also commonly used to destroy cell membranes to achieve the goal of removing nuclear remnants and cytoplasmic proteins (35). Moreover, the optimal magnitude or frequency of sonication for breaking down cells is dependent on the composition, volume, and density of the tissue. Along with chemical or enzymatic methods, these mechanical methods have been used successfully in assistance of cell lysis and removal of cellular debris.

Chemical methods

Chemical methods involve the use of a variety of detergents to disrupt cell-cell and cell-matrix bonds, which have been regarded as the most extensive and robust method for decellularization (36,37). These detergents can be classified as four categories: Ionic (sodium dodecyl sulfate: SDS), nonionic (Triton X-100), zwitterionic (CHAPS), alkaline and acid. The mechanism of these detergents for decellularization includes facilitating cell lysis and solubilizing the released cellular components through the formation of micelles (38). The choice of decellularized detergents depends on tissue characteristics, such as cellular density, lipid content, and thickness. The following section will summarize the optimal recipe of decellularization agents for removing cellular components efficiently from the entire organ system.

Ionic detergents are subdivided into cationic and anionic solutions. Among them, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and sodium deoxycholate are representative examples for the removal of cellular debris from tissues (39). SDS is commonly used in the removal of nuclear remnants and cytoplasmic proteins, while sodium deoxycholate proved to be superior for solubilizing cytoplasmic and nuclear membranes. Thus, they are generally combined together to effectively eliminate cellular content in the medullary regions of dense organs, such as the kidney (40). However, there are some limitations when fusing ionic detergents for decellularization, such as the denaturation of ECM proteins and disruption of native tissue structure (41). Conversely, Triton X-100, a nonionic detergent, has the least negative impact on the protein structure and is therefore commonly used for decellularization protocols (42). When Triton X-100 is applied to decellularize a heart valve, a complete removal of nuclear remnants and maintenance of the native ECM structure and composition after 24 h immersion is observed (43). CHAPS is a zwitterionic detergent that has been confirmed to have a mild ability to retain mechanical strength when used for the decellularization of lungs (44). CHAPS-treated artery tissue is presented as an intact structure with native collagen and elastin morphology and the collagen content is approximately the same as the native artery (45). Acidic and alkaline solutions, including HCl and NaOH, are commonly used to disrupt cell membranes and solubilize the cytoplasmic component at low concentrations. Moreover, it has also been shown that pH change in ECM digestible solution to prepare porcine spinal cord tissue via sequentially adding NaOH and HCl, increased the rate of gelation (46). Regarding the types and concentrations of chemicals employed in the decellularization process, it is generally more advantageous to use different chemicals and form a proper combination to exert the optimum decellularization efficiency.

Enzymatic methods

Enzymatic technology for decellularization is frequently utilized to disrupt the interactions between the cells and the ECM, or to remove antigenic material to decrease immunogenicity (47). Generally, proteases (e.g., trypsin, pepsin), nucleases (e.g., DNase, RNase), lipase, heparinases and hyaluronidase are the most widely applied proteolytic enzymes in decellularization protocols for a variety of tissues. The advantages of using enzymatic treatments for efficient decellularization are listed as follows (48,49): i) Efficient decellularization via combining with other detergents; ii) maintaining the structural integrity of the ECM for complex organs; iii) targeting specific target molecules removal in tissues, such as Gal epitope and DNA. It has been shown that enzymatic methods for the removal of cell debris are through specifically targeting the proteins to disrupt cell-ECM adhesions. As one of the most commonly used proteolytic enzymes, trypsin inactivates cell surface receptors, apart from adhesion complexes. Moreover, it exerts the maximal enzymatic activity to disrupt cell-matrix interactions in tissues at the condition of 37°C and pH=8.0 (50). Although trypsin alone is able to decellularize a soft tissue entirely, efficiency in the removal of complex tissues is shown to be greater when it combines with other detergents, including EDTA, and NaCl (51). Pepsin in weak acetic acid increases the yield of highly crosslinked fibrillar collagen (e.g., type I from skin, bone or tendon) but decreases the stability of reconstituted gels at neutral pH. Nucleases, including DNases and RNases, are used to cleave nucleic acid sequences after cell lysis in tissues. Recent findings have shown that intervertebral discs subjected to treatment with 0.02 mg/ml DNase and 20 mg/ml RNAse, not only removed DNA residual at acceptable levels of less than 50 ng/mg dry weight, but also markedly reduced the total processing time of ECM digestion (52). Lipase specifically targets ester bond of triglycerides to hydrolyze lipase into glycerol and fatty acids. Thus, it is widely used for digesting lipase from fatty tissues, including intestinal mucosa, human nerve and heart. In addition, heparinases and hyaluronidase aid in releasing growth factors, exposing proteins such as surface receptors and decreasing the water binding capacity (happening also in arthritic conditions). Overall, adding enzyme as the final step for solubilizing decellularized tissue may be desirable or even necessary, particularly for complete removal of cell residues or undesirable ECM constituents from dense tissues.

4. Removal of residual cellular components and chemicals

It is well known that to prepare proper ECM hydrogel after decellularization and solubilization, it is required to ensure the removal of undesired materials and decellularization agents as much as possible, while mostly retaining the desired ECM components and native architectures as well (53). The undesirable residual cellular materials include cellular-derived DNA, endotoxins, xenoantigens and pathogenic contaminations, as well as the decellularization agents mentioned in the above chapter. The residual cellular-derived DNA can be regarded as undesirable remnants of decellularization rather than an accurate and reliable representative universal reporter of cellular contamination (54). Current reports of minimal criteria for acceptable amounts of residual DNA in biologic ECM hydrogel is less than 50 ng/mg of dry product with fragment length of less than 300 bp (55), which can be detected simply through commercial dye-based optometric assays or other histologic staining techniques. As contaminants in biologically derived materials, endotoxins have the potent ability to stimulate acute inflammatory responses for different cell types with varying threshold levels of contamination. Presently, the US FDA has stipulated that the detection limit of endotoxins in all medical devices, including hydrogels made from decellularized tissues, need to meet the requirement of less than 0.5 EU/ml (56). Based on the fact that endotoxin determinations are required for ECM-derived materials, the use of commercialized limulus amebocyte lysate test has been accepted as a highly sensitive and accurate method for assessing the safety of a wider range of ECM-P (57). Xenoantigens, including α-gal and MHC-I, are the two major extracellular components presented in the purified ECM-G. When applied in clinical studies, these two antigens could promote recruitment and activation of immune cells, such as T-cells and B-cells, to secrete a large number of cytokines and chemokines that strongly invoked implant rejection and a host response (58). Thus, these xenoantigens should be eliminated from the prepared ECM-G as much as possible. Besides xenogenic cellular antigens, residual chemicals in the decellularized materials is also an important concern.

The decellularization steps involve the utilization of a wide variety of chemical agents. These residual chemicals within the ECM-G are mainly various non-ionic and ionic solutions, including Triton X-100 and SDS (10). A high concentration of these residual chemicals within the ECM-G will most likely provoke an adverse host tissue response and lead to cytotoxicity (59). Thus, care must be taken to flush residual chemicals away from ECM-G after decellularization. As these residual chemicals have high affinity with ECM-related proteins, there is no optimal method for the complete removal of these residual chemicals, except for persistent washing steps with sterile water (59). As such, we need to create a useful detergent that has the capability of absorbing these residual chemicals and develop a standardized analytical technique that can accurately detect the presence of chemicals after decellularization.

5. Application of ECM-P in regenerative medicine

In recent years, the use of ECM-P for surgical applications has become increasingly prevalent, especially for the field of nerve regeneration and bone repair (60). It is well known that ECM-P contain a complex meshwork of proteins and polysaccharides, which provides biochemical support to the surrounding cells for promoting their survival, proliferation and differentiation (61). Moreover, they also possess an intact three-dimensional structure and a certain intrinsic mechanical property, which contribute to creating an optical microenvironment for wound healing and tissue remodeling (62). Additionally, they are used as in vitrocell culture platforms for seeding and differentiating stem cells into tissue- and organ-specific cells, or regarded as a bio-therapeutic vehicle capable of delivering GFs or cytokines to control their release in a steady manner at the local site of action (3,63). Thus, ECM-P have been used in different ways and combinations for guiding cell regrowth and tissue repair. The applications of ECM-P for numerous pre-clinical and clinical restoration of dysfunctional cells/tissues are described in the following subsections.

Cellular response to ECM-P

The ECM-P are composed of various distinct components that create a permissive environment for cell spreading, migration, proliferation, and differentiation. They also regulate cellular phenotype and behavior in various forms. Emerging researches and preliminary clinical studies have used this matrix for 3D cell culture. For instance, when human mesenchymal stem cells were encapsulated into a hydrogel with interpenetrating network to form a 3D culture model, the components of collagen and fibrillar could interact with the stem cell surface receptors, CD44 and RHAMM15, to support their spreading and focal adhesion formation (64). Furthermore, the combination of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells and umbilical vein endothelial cells in a 3D co-culture system formed by photocrosslinking GelMA hydrogel efficiently stimulated cell proliferation and differentiation as well as vascularization (65). Besides acting as the 3D culture platforms, ECM-P are also proposed for the construction of bioinks for tissue 3D printing. Lee and colleagues constructed a highly accurate human heart model which enabled rapid cellular infiltration and microvascularization using the freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels via 3D-bioprinting technique (66). Spatial organization of cardiac progenitor cells into porcine left ventricle tissue-derived decellularized extracellular matrix bioink using 3D cell printing method could effectively facilitate cell survival and differentiation, and improve cell-to-cell interactions, resulting in beneficial effects on reducing cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis along with improving cardiac function after patch transplantation (67). ECM hydrogels incorporated with stem cells hold great promise for the formation and growth of human organoids which can be applied as a therapeutic tool for various disease models. The earliest report identified intestinal organoid formation through expansion of mouse and human intestinal stem cell matrices in an appropriate 3D matrix hydrogel (68). Subsequently, the use of ECM hydrogels derived from decellularized porcine small intestine mucosa endodermal organoid has the advantage for providing a structural support and biochemical signals to enable formation and growth of endoderm-derived human organoids, including hepatic, pancreatic, and small intestine (2). Similarly, Saheli et al reported that a 3D sheep liver-derived ECM hydrogel has the capability to tailor the biochemical and biophysical microenvironment for inducing a functional liver organoids generation by co-culturing human hepatocarcinoma cells, human mesenchymal and endothelial cells at a 3:2:1 ratio (69). Therefore, hydrogel-based organoid morphogenesis has been employed for the construction of 3D tissue models in vitro to revolutionize biomedical research and drug development.

Although 3D organotypic construct has provided a suitable platform for potential applications in imitating disease modeling and organ development, as well as regenerative medicine, there are some obstacles that need to be over-come. One major issue is low reproducibility of organoids and limited capability of differentiation into special tissue and organ types (70). It is well known that cell expansion, differentiation and self-organization are mainly dependent on inherent genetic reprogramming and external microenvironmental cues, such as distinct biochemical and biophysical factors (71,72). To reproducibly and accurately recapitulate the expansion and differentiation of specific organoids, emerging solutions adopted gene reprogramming technology to directly alter specific gene of DNA in stem cells or utilized engineering approaches to precisely control cell-matrix inter-actions, nutrient supply and the local stiffness of the organoids formation (73,74). Another issue is the lack of vascular system during the generation of organoids (72). Neovascularization is of great importance for maintaining tissue oxygenation and fluid homeostasis. This problem may be solved by utilizing prevascularized scaffolds from matrix hydrogels modules via sacrificial printing (75).

It should be noted that ECM-P sourced from different tissues/organs contained some specific molecules that play an important role in cell phenotype and behavior (21). Logically, the native ECM-P of the homologous tissue or organ sources have superior biological property for inducing cell survival, proliferation and differentiation, as well as exerting multiple regenerative medicine therapies (3). It has been reported that the canine sciatic nerve-specific extracellular matrix-based hydrogel had the inherent ability to increase the M2 macro-phage ratio and enhance Schwann cell migration, leading to functional recovery and nerve repair in a rodent nerve gap defect model (76). In addition, results of a study by Keane et al showed that a homologous esophageal ECM-gel derived from small intestinal submucosa had more biological advantage in enhancing the migration of esophageal stem cells and the formation of 3D organoids than that of the non-homologous ECM-gel isolated from urinary bladder (77). These outcomes indicated that the site-specific or homologous ECM hydrogel could provide a set of tissue-specific matrix and cell-secreted molecules for promoting site-appropriate differentiation of stem cells and maintaining site appropriate phenotype in vitro.

ECM-P for preclinical applications

The decellularized tissue materials inherit various biochemical components that are favorable for organ development, tissue repair, and wound healing. Currently, ECM-P have been successfully used in a variety of pre-clinical animal model studies, such as spinal cord injury (SCI), peripheral nerve regeneration, myocardial repair, and so on (1,78). The reason for ECM-P serving as a suitable substitute for damaged tissue restoration is their ability to provide a native tissue microenvironment for coexisting and interacting with specific body tissues or physiological systems without provoking strong immune and toxicity responses. Besides these unique properties, numerous proteins including collagen, elastin, fibrillin, and fibulin in the ECM-P also activate a series of downstream signals of PI3K/AKT, MEK/ERK and/or Rho A/ROCK to exert their biological effect via binding to cell surface receptors (79-81). In additional, associated macromolecular non-protein glycosaminoglycans found in the ECM-P reversibly adsorb GFs and cytokines, expanding their application for tissue morphogenesis and organ development. Presently, we will discuss ECM-P for preclinical applications through two main aspects: The nerves and the heart.

The adult nervous system, classified into the central (CNS) and peripheral (PNS) regions, initiates a biological response via receiving internal and external stimuli on the neuronal membrane. As the longest and thickest nerve in the PNS, sciatic nerve arranges the movement and sensation of leg and foot muscle. If sciatic nerve suffered from traumatic injury, surgery or compression, the partial or total loss of motor, sensory, and autonomic functions are bound to happen, leading to restricted activity and affecting the quality of life for clinical patients (82). An established strategy for therapeutic interventions is using ECM-P, such as ECM-based conduit or scaffold incorporated with/without GFs or macromolecules, to implant into the lesion region (83). This technique, not only provides mechanical support for cell adhesion, but also produces insoluble microenvironmental cues for improving nerve functional recovery. Thus, this material is used widely for peripheral nerve regeneration. A decellularized porcine nerve matrix hydrogel could support SC proliferation in vitro and promote axon regeneration, myelination, and functional recovery when combined with electrospun conduits together to repair 15-mm rat sciatic nerve defect model in vivo (84). Shuai et al have successfully developed a human decellularized nerve scaffold via combining decellularized nerve matrix hydrogel and glial-derived neurotrophic factor together and applying it to bridge a 50 mm sciatic nerve defect in a beagle model. The result showed that this nerve scaffold had excel-lent effects on promoting motor function recovery and nerve tissue remodeling (85). Additionally, studies have confirmed that alginate/hyaluronic acid 3D scaffold was used successfully to direct the differentiation of encapsulated gingival mesenchymal stem cells towards neurogenic tissues for nerve regeneration therapies (86). Overall, these biological ECM-P derived from mammal sciatic nerve showed various structural and functional characteristics for enhancing peripheral nerve regeneration.

The CNS trauma, including traumatic brain injury (TBI) and SCI, initiates a cascade of changes at both cellular and molecular level, which disturbs the microenvironmental homeostasis, impairs axon regeneration and inhibits full functional recovery. Injectable hydrogel with appropriate mechanical properties has been applied most extensively for both injury models (22). It has been demonstrated that urinary bladder matrix hydrogel injection alone decreased lesion volume and myelin disruption, as well as improved neurobehavioral recovery following TBI (87). Further studies demonstrated that transplantation of proliferating neural stem cells in bioactive urinary bladder matrix hydrogel significantly ameliorated memory and cognitive impairments following TBI (88). Similarly, extensive findings also apply ECM-P for conducting SCI trial. It has been reported that injection of thermosensitive poly(organophosphazenes) hydrogel into the cystic cavities of injured spinal cord could support axon growth, reduce cavity volume and decrease locomotor deficit (89). Use of synthetic matrix materials, seen in a study by Hong et al, included PEGDA and GelMa been fabricated into a spinal cord scaffold via 3D printing (90). Their results showed significant improvements in motor functional outcome and axonal elongation from the lesion site into the distal host spinal cord.

Myocardial infarction (MI) is a term for an event of heart attack with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality (91). Porcine myocardial ECM hydrogel for treating progressive heart failure following MI has been investigated for recent regenerative therapy application, because this ECM material is capable of assembling into a nanofibrous network that allows cell migration and has tissue-specific cues that are in favor for appropriate cardiac tissue remodeling (92). For instance, decellularized myocardial matrix hydrogel has become an alternative option for MI treatment and achieved long-term functional stabilization and improvement in heart function (93). However, simple use of solubilized porcine myocardial ECM hydrogel for MI application has some problems, such as limited mechanical strength and rapid degradation (94). To overcome these limitations, Efraim et al presented a newly-developed injectable scaffold via cross-linking decellularized porcine cardiac extracellular matrix hydrogel with chitosan, which exhibited significant improvement for cardiac tissue regeneration when injected into rat hearts following acute and chronic MI (95). Moreover, use of nanocomposite hydrogel as a carrier for the delivery of the mesenchymal stem cells showed an efficient improvement in capillary density and myocardial regeneration, as well as reduction in scar area (96). Thus, incorporation of stem cell and/or cytokines within the myocardial ECM hydrogel represents a viable option for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction.

ECM-P for clinical applications

The use of allogeneic or xenogeneic ECM-P, which are commercially available for more than 20 years, have become a primary option for remodeling a variety of clinical tissues defects, such as the myocardium reconstruction, bone regeneration and nerve repair (3). Most commercial products from various ECM sources have been reviewed in depth elsewhere (97). Thus, we just list some of their therapeutic outcomes. One example for evaluating MI repair in clinical trials is myocardial ECM hydrogel (identifier: NCT02305602). This heterologous material had the ability to go through a cardiac injection catheter to enhance vascular cell infiltration and cardiomyocyte survival (98). In parallel, previous findings have shown that Avance® Nerve Graft (AxoGen Inc.) has been used to repair human sciatic nerve defect and achieve positive axon regrowth and motor functional recovery (99). Besides, a biocompatible hydrogel scaffold (Geistlich Pharma AG) isolated from the decellularized and demineralized bone has confirmed promising outcomes for repairing early and mid-term clinical osteochondral knee defects (100). The common features of these ECM-P for extensive applications of regenerative medicine can be categorized as follows: i) Preserving meshwork of native architecture and biologically active molecules; ii) excellent mechanical and structural profiles; iii) biodegradation and temperature-sensitive property; and iv) easily integrating with the native tissue by filling the irregular defects. In this sense, ECM-P have provided an efficient therapeutic approach to guide tissue regeneration and replacement.

6. Challenges and future outlook on ECM-P

Although ECM-P appear to have many advantages, there are some existing issues that need to be addressed. One problem is tissue homogeny. It has been shown that tissue sources, including the species, age, and specificity, can significantly alter tissue-specific cell phenotype and function (101). Therefore, selection of the proper hydrogel product is the precondition for clinical tissue reconstruction. Another issue is product size and shape. As the cavity region of damaged tissue is irregular, implantation of pre-formed scaffolds is usually inefficient (102). At this condition, injection of gelatinous liquid is probably more suitable for treating complex disease and injury models. Additionally, requirements may be completely different when ECM-P were used for replacing a heart valve or a piece of aorta, repairing wounds or defects in skin, mucosa, joints, or bones. Thus, the design of ECM-P needs to satisfy the specific requirements for different diseases. As ECM-P are becoming the alternative biomaterials for the regeneration and repair of damaged tissues, some of the current challenges can be overcome via developing international standards and good manufacturing practices.

7. Conclusions

Overall, this review sought to highlight the selection of an appropriate decellularized technique for improving biocompatibility and biomimetic properties in the ECM-P that are suitable for applying in regenerative medicine research. With regards to structural and compositional diversity, each kind of ECM-P from specific tissue or organ have their unique microenvironments and biochemical cues for inducing site-appropriate cellular growth and tissue regeneration. In the future, with the development of 3D bioprinting approach and computer-aided design technology, biocompatible ECM products are emerging as a promising artificial tissue substitutes with suitable mechanical and morphological characteristics for restoring damaged tissues or organ.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was partially supported by a research grant from the National Natural Science Funding of China (81802238), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LWQ20H170001).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YL, RL and H were involved in the conception of the study. RL, CH and LH were involved in the literature search and critical reviewing of the manuscript. YJ and RL were involved in the preparation of the draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors confirm this article has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrm3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giobbe GG, Crowley C, Luni C, Campinoti S, Khedr M, Kretzschmar K, De Santis MM, Zambaiti E, Michielin F, Meran L, et al. Extracellular matrix hydrogel derived from decellularized tissues enables endodermal organoid culture. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5658. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spang MT, Christman KL. Extracellular matrix hydrogel therapies: In vivo applications and development. Acta Biomater. 2018;68:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraehenbuehl TP, Zammaretti P, Van der Vlies AJ, Schoenmakers RG, Lutolf MP, Jaconi ME, Hubbell JA. Three-dimensional extracellular matrix-directed cardiopro-genitor differentiation: Systematic modulation of a synthetic cell-responsive PEG-hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2757–2766. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Y, Ji Y, Huang G, Ling K, Zhang X, Xu F. Bioprinting 3D cell-laden hydrogel microarray for screening human periodontal ligament stem cell response to extracellular matrix. Biofabrication. 2015;7:044105. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/7/4/044105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aamodt JM, Grainger DW. Extracellular matrix-based biomaterial scaffolds and the host response. Biomaterials. 2016;86:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vincent AT, Schiettekatte O, Goarant C, Neela VK, Bernet E, Thibeaux R, Ismail N, Mohd Khalid MKN, Amran F, Masuzawa T, et al. Revisiting the taxonomy and evolution of pathogenicity of the genus Leptospira through the prism of genomics. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szalewski DA, Hinrichs VS, Zinniel DK, Barletta RG. The pathogenicity of Aspergillus fumigatus, drug resistance, and nanoparticle delivery. Can J Microbiol. 2018;64:439–453. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2017-0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zilelidou EA, Skandamis PN. Growth, detection and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes in the presence of other microorganisms: Microbial interactions from species to strain level. Int J Food Microbiol. 2018;277:10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert TW, Sellaro TL, Badylak SF. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3675–3683. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi JS, Yang HJ, Kim BS, Kim JD, Kim JY, Yoo B, Park K, Lee HY, Cho YW. Human extracellular matrix (ECM) powders for injectable cell delivery and adipose tissue engineering. J Control Release. 2009;139:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sackett SD, Tremmel DM, Ma F, Feeney AK, Maguire RM, Brown ME, Zhou Y, Li X, O'Brien C, Li L, et al. Extracellular matrix scaffold and hydrogel derived from decellularized and delipidized human pancreas. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10452. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28857-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lv S, Bu T, Kayser J, Bausch A, Li H. Towards constructing extracellular matrix-mimetic hydrogels: An elastic hydrogel constructed from tandem modular proteins containing tenascin FnIII domains. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:6481–6491. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao N, Agmon G, Tierney MT, Ungerleider JL, Braden RL, Sacco A, Christman KL. Engineering an injectable muscle-specific microenvironment for improved cell delivery using a nanofibrous extracellular matrix hydrogel. ACS Nano. 2017;11:3851–3859. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seif-Naraghi SB, Horn D, Schup-Magoffin PJ, Christman KL. Injectable extracellular matrix derived hydrogel provides a platform for enhanced retention and delivery of a heparin-binding growth factor. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:3695–3703. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidov T, Efraim Y, Dahan N, Baruch L, Machluf M. Porcine arterial ECM hydrogel: Designing an in vitro angiogenesis model for long-term high-throughput research. FASEB J. 2020;34:7745–7758. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosso F, Giordano A, Barbarisi M, Barbarisi A. From cell-ECM interactions to tissue engineering. J Cell Physiol. 2004;199:174–180. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Divya P, Krishnan LK. Glycosaminoglycans restrained in a fibrin matrix improve ECM remodelling by endothelial cells grown for vascular tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:377–388. doi: 10.1002/term.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SH, Lee SH, Lee JE, Park SJ, Kim K, Kim IS, Lee YS, Hwang NS, Kim BG. Tissue adhesive, rapid forming, and sprayable ECM hydrogel via recombinant tyrosinase cross-linking. Biomaterials. 2018;178:401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J, Ding Q, Dutta A, Wang Y, Huang YH, Weng H, Tang L, Hong Y. An injectable extracellular matrix derived hydrogel for meniscus repair and regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2015;16:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tukmachev D, Forostyak S, Koci Z, Zaviskova K, Vackova I, Vyborny K, Sandvig I, Sandvig A, Medberry CJ, Badylak SF, et al. Injectable extracellular matrix hydrogels as scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair. Tissue Eng Part A. 2016;22:306–317. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2015.0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahearne M. Introduction to cell-hydrogel mechanosensing. Interface Focus. 2014;4:20130038. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vats K, Benoit DS. Dynamic manipulation of hydrogels to control cell behavior: a review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2013;19:455–469. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2012.0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghuman H, Mauney C, Donnelly J, Massensini AR, Badylak SF, Modo M. Biodegradation of ECM hydrogel promotes endogenous brain tissue restoration in a rat model of stroke. Acta Biomater. 2018;80:66–84. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black C, Kanczler JM, de Andres MC, White LJ, Savi FM, Bas O, Saifzadeh S, Henkel J, Zannettino A, Gronthos S, et al. Characterisation and evaluation of the regenerative capacity of Stro-4+ enriched bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells using bovine extracellular matrix hydrogel and a novel biocompatible melt electro-written medical-grade polycaprolactone scaffold. Biomaterials. 2020;247:119998. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Gallant RC, Ni H. Extracellular matrix proteins in the regulation of thrombus formation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2016;23:280–287. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang B, Suen R, Wertheim JA, Ameer GA. Targeting heparin to collagen within extracellular matrix significantly reduces thrombogenicity and improves endothelialization of decellular-ized tissues. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:3940–3948. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Zhang C, Haggerty AE, Yan J, Lan M, Seu M, Yang M, Marlow MM, Maldonado-Lasunció I, Cho B, et al. The effect of a nanofiber-hydrogel composite on neural tissue repair and regeneration in the contused spinal cord. Biomaterials. 2020;245:119978. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrokhi A, Pakyari M, Nabai L, Pourghadiri A, Hartwell R, Jalili R, Ghahary A. Evaluation of detergent-free and deter-gent-based methods for decellularization of murine skin. Tissue Eng Part A. 2018;24:955–967. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2017.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta SK, Mishra NC, Dhasmana A. Decellularization methods for scaffold fabrication. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1577:1–10. doi: 10.1007/7651_2017_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isidan A, Liu S, Li P, Lashmet M, Smith LJ, Hara H, Cooper DKC, Ekser B. Decellularization methods for developing porcine corneal xenografts and future perspectives. Xenotransplantation. 2019;26:e12564. doi: 10.1111/xen.12564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson DW, Grood ES, Arnoczky SP, Butler DL, Simon TM. Freeze dried anterior cruciate ligament allografts. Preliminary studies in a goat model. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:295–303. doi: 10.1177/036354658701500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson DW, Grood ES, Wilcox P, Butler DL, Simon TM, Holden JP. The effects of processing techniques on the mechanical properties of bone-anterior cruciate ligament-bone allografts. An experimental study in goats. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:101–105. doi: 10.1177/036354658801600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mardhiyah A, Sha'ban M, Azhim A. Evaluation of histological and biomechanical properties on engineered meniscus tissues using sonication decellularization. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2017;2017:2064–2067. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2017.8037259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hrebikova H, Diaz D, Mokry J. Chemical decellularization: A promising approach for preparation of extracellular matrix. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2015;159:12–17. doi: 10.5507/bp.2013.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tchoukalova YD, Hintze JM, Hayden RE, Lott DG. Tracheal decellularization using a combination of chemical, physical and bioreactor methods. Int J Artif Organs. 2017 Sep 28; doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000648. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang WC, Cheng YH, Yen MH, Chang Y, Yang VW, Lee OK. Cryo-chemical decellularization of the whole liver for mesenchymal stem cells-based functional hepatic tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3607–3617. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCrary MW, Vaughn NE, Hlavac N, Song YH, Wachs RA, Schmidt CE. Novel sodium deoxycholate-based chemical decellularization method for peripheral nerve. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2020;26:23–36. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2019.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tebyanian H, Karami A, Motavallian E, Aslani J, Samadikuchaksaraei A, Arjmand B, Nourani MR. Histologic analyses of different concentrations of tritonX-100 and Sodium dodecyl sulfate detergent in lung decellularization. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2017;63:46–51. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2017.63.7.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vafaee T, Thomas D, Desai A, Jennings LM, Berry H, Rooney P, Kearney J, Fisher J, Ingham E. Decellularization of human donor aortic and pulmonary valved conduits using low concen-tration sodium dodecyl sulfate. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:e841–e853. doi: 10.1002/term.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu BT, Li WT, Song BQ, Wu YL. Comparative study of the triton X-100-sodium deoxycholate method and detergent-enzymatic digestion method for decellularization of porcine aortic valves. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2179–2184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varhac R, Robinson NC, Musatov A. Removal of bound triton X-100 from purified bovine heart cytochrome bc1. Anal Biochem. 2009;395:268–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahl SL, Koh J, Prabhakar V, Niklason LE. Decellularized native and engineered arterial scaffolds for transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2003;12:659–666. doi: 10.3727/000000003108747136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen RN, Ho HO, Tsai YT, Sheu MT. Process development of an acellular dermal matrix (ADM) for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2679–2686. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goissis G, Suzigan S, Parreira DR, Maniglia JV, Braile DM, Raymundo S. Preparation and characterization of collagen-elastin matrices from blood vessels intended as small diameter vascular grafts. Artif Organs. 2000;24:217–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2000.06537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gamba PG, Conconi MT, Lo Piccolo R, Zara G, Spinazzi R, Parnigotto PP. Experimental abdominal wall defect repaired with acellular matrix. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:327–331. doi: 10.1007/s00383-002-0849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McFetridge PS, Daniel JW, Bodamyali T, Horrocks M, Chaudhuri JB. Preparation of porcine carotid arteries for vascular tissue engineering applications. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;70:224–234. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teebken OE, Bader A, Steinhoff G, Haverich A. Tissue engineering of vascular grafts: Human cell seeding of decellularised porcine matrix. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2000;19:381–386. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1999.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahman S, Griffin M, Naik A, Szarko M, Butler PEM. Optimising the decellularization of human elastic cartilage with trypsin for future use in ear reconstruction. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3097. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20592-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warwick RM, Magee JG, Leeming JP, Graham JC, Hannan MM, Chadwick M, Crook DW, Yearsley CP, Rayner A, Parker R. Mycobacteria and allograft heart valve banking: An international survey. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hensley A, Rames J, Casler V, Rood C, Walters J, Fernandez C, Gill S, Mercuri JJ. Decellularization and characterization of a whole intervertebral disk xenograft scaffold. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2018;106:2412–2423. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crapo PM, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3233–3243. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong ML, Griffiths LG. Immunogenicity in xenogeneic scaffold generation: Antigen removal vs. Decellularization Acta Biomater. 2014;10:1806–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagata S, Hanayama R, Kawane K. Autoimmunity and the clearance of dead cells. Cell. 2010;140:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dullah EC, Ongkudon CM. Current trends in endotoxin detection and analysis of endotoxin-protein interactions. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017;37:251–261. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2016.1141393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ogikubo Y, Norimatsu M, Noda K, Takahashi J, Inotsume M, Tsuchiya M, Tamura Y. Evaluation of the bacterial endotoxin test for quantification of endotoxin contamination of porcine vaccines. Biologicals. 2004;32:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang YG, Sykes M. Xenotransplantation: Current status and a perspective on the future. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:519–531. doi: 10.1038/nri2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aurora A, McCarron J, Iannotti JP, Derwin K. Commercially available extracellular matrix materials for rotator cuff repairs: State of the art and future trends. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(Suppl 5):S171–S178. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ercan H, Durkut S, Koc-Demir A, Elçin AE, Elçin YM. Clinical applications of injectable biomaterials. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1077:163–182. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-0947-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmadian Z, Correia A, Hasany M, Figueiredo P, Dobakhti F, Eskandari MR, Hosseini SH, Abiri R, Khorshid S, Hirvonen J, et al. A hydrogen-bonded extracellular matrix-mimicking bactericidal hydrogel with radical scavenging and hemostatic function for pH-responsive wound healing acceleration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020 Oct 26; doi: 10.1002/adhm.202001122. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ha DH, Chae S, Lee JY, Kim JY, Yoon J, Sen T, Lee SW, Kim HJ, Cho JH, Cho DW. Therapeutic effect of decellularized extra-cellular matrix-based hydrogel for radiation esophagitis by 3D printed esophageal stent. Biomaterials. 2021;266:120477. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beachley V, Ma G, Papadimitriou C, Gibson M, Corvelli M, Elisseeff J. Extracellular matrix particle-glycosaminoglycan composite hydrogels for regenerative medicine applications. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2018;106:147–159. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lou J, Stowers R, Nam S, Xia Y, Chaudhuri O. Stress relaxing hyaluronic acid-collagen hydrogels promote cell spreading, fiber remodeling, and focal adhesion formation in 3D cell culture. Biomaterials. 2018;154:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang X, Li J, Ye P, Gao G, Hubbell K, Cui X. Coculture of mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial cells enhances host tissue integration and epidermis maturation through AKT activation in gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel-based skin model. Acta Biomater. 2017;59:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee A, Hudson AR, Shiwarski DJ, Tashman JW, Hinton TJ, Yerneni S, Bliley JM, Campbell PG, Feinberg AW. 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Science. 2019;365:482–487. doi: 10.1126/science.aav9051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jang J, Park HJ, Kim SW, Kim H, Park JY, Na SJ, Kim HJ, Park MN, Choi SH, Park SH, et al. 3D printed complex tissue construct using stem cell-laden decellularized extracellular matrix bioinks for cardiac repair. Biomaterials. 2017;112:264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gjorevski N, Sachs N, Manfrin A, Giger S, Bragina ME, Ordóñez-Morán P, Clevers H, Lutolf MP. Designer matrices for intestinal stem cell and organoid culture. Nature. 2016;539:560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saheli M, Sepantafar M, Pournasr B, Farzaneh Z, Vosough M, Piryaei A, Baharvand H. Three-dimensional liver-derived extracellular matrix hydrogel promotes liver organoids function. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:4320–4333. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Broguiere N, Isenmann L, Hirt C, Ringel T, Placzek S, Cavalli E, Ringnalda F, Villiger L, Züllig R, Lehmann R, et al. Growth of epithelial organoids in a defined hydrogel. Adv Mater. 2018;30:e1801621. doi: 10.1002/adma.201801621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Augsornworawat P, Velazco-Cruz L, Song J, Millman JR. A hydrogel platform for in vitro three dimensional assembly of human stem cell-derived islet cells and endothelial cells. Acta Biomater. 2019;97:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu H, Wang Y, Cui K, Guo Y, Zhang X, Qin J. Advances in hydrogels in organoids and organs-on-a-chip. Adv Mater. 2019;31:e1902042. doi: 10.1002/adma.201902042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chuang W, Sharma A, Shukla P, Li G, Mall M, Rajarajan K, Abilez OJ, Hamaguchi R, Wu JC, Wernig M, Wu SM. Partial reprogramming of pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes into neurons. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44840. doi: 10.1038/srep44840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garreta E, Prado P, Tarantino C, Oria R, Fanlo L, Martí E, Zalvidea D, Trepat X, Roca-Cusachs P, Gavaldà-Navarro A, et al. Fine tuning the extracellular environment accelerates the derivation of kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Mater. 2019;18:397–405. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0287-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gong J, Schuurmans CCL, Genderen AMV, Cao X, Li W, Cheng F, He JJ, López A, Huerta V, Manríquez J, et al. Complexation-induced resolution enhancement of 3D-printed hydrogel constructs. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1267. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14997-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prest TA, Yeager E, LoPresti ST, Zygelyte E, Martin MJ, Dong L, Gibson A, Olutoye OO, Brown BN, Cheetham J. Nerve-specific, xenogeneic extracellular matrix hydrogel promotes recovery following peripheral nerve injury. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2018;106:450–459. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Keane TJ, DeWard A, Londono R, Saldin LT, Castleton AA, Carey L, Nieponice A, Lagasse E, Badylak SF. Tissue-specific effects of esophageal extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:2293–2300. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2015.0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schnellmann R, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Preparation and application of a decellularized extracellular matrix for identification of ADAMTS substrates. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2043:275–284. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9698-8_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li R, Li Y, Wu Y, Chen H, Yuan Y, Xu K, Zhang H, Lu Y, Wang J, Li X, et al. Heparin-poloxamer thermosensitive hydrogel loaded with bFGF and NGF enhances peripheral nerve regeneration in diabetic rats. Biomaterials. 2018;168:24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Slivka PF, Dearth CL, Keane TJ, Meng FW, Medberry CJ, Riggio RT, Reing JE, Badylak SF. Fractionation of an ECM hydrogel into structural and soluble components reveals distinc-tive roles in regulating macrophage behavior. Biomater Sci. 2014;2:1521–1534. doi: 10.1039/C4BM00189C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Panorchan P, Lee JS, Kole TP, Tseng Y, Wirtz D. Microrheology and ROCK signaling of human endothelial cells embedded in a 3D matrix. Biophys J. 2006;91:3499–3507. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sjöberg J, Kanje M. The initial period of peripheral nerve regeneration and the importance of the local environment for the conditioning lesion effect. Brain Res. 1990;529:79–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90812-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grinsell D, Keating CP. Peripheral nerve reconstruction after injury: A review of clinical and experimental therapies. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:698256. doi: 10.1155/2014/698256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin T, Liu S, Chen S, Qiu S, Rao Z, Liu J, Zhu S, Yan L, Mao H, Zhu Q, et al. Hydrogel derived from porcine decellularized nerve tissue as a promising biomaterial for repairing peripheral nerve defects. Acta Biomater. 2018;73:326–338. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qiu S, Rao Z, He F, Wang T, Xu Y, Du Z, Yao Z, Lin T, Yan L, Quan D, et al. Decellularized nerve matrix hydrogel and glial-derived neurotrophic factor modifications assisted nerve repair with decellularized nerve matrix scaffolds. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2020;14:931–943. doi: 10.1002/term.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ansari S, Diniz IM, Chen C, Sarrion P, Tamayol A, Wu BM, Moshaverinia A. Human periodontal ligament- and gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote nerve regeneration when encapsulated in alginate/hyaluronic acid 3D scaffold. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6:10. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang L, Zhang F, Weng Z, Brown BN, Yan H, Ma XM, Vosler PS, Badylak SF, Dixon CE, Cui XT, Chen J. Effect of an inductive hydrogel composed of urinary bladder matrix upon functional recovery following traumatic brain injury. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:1909–1918. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang JY, Liou A, Ren ZH, Zhang L, Brown BN, Cui XT, Badylak SF, Cai YN, Guan YQ, Leak RK, et al. Neurorestorative effect of urinary bladder matrix-mediated neural stem cell trans-plantation following traumatic brain injury in rats. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12:413–425. doi: 10.2174/1871527311312030014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buckenmeyer MJ, Meder TJ, Prest TA, Brown BN. Decellularization techniques and their applications for the repair and regeneration of the nervous system. Methods. 2020;171:41–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hong LT, Kim YM, Park HH, Hwang DH, Cui Y, Lee EM, Yahn S, Lee JK, Song SC, Kim BG. An injectable hydrogel enhances tissue repair after spinal cord injury by promoting extracellular matrix remodeling. Nat Commun. 2017;8:533. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00583-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jiang X, Yang Z, Dong M. Cardiac repair in a murine model of myocardial infarction with human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:297. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01811-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Farnebo S, Woon CY, Schmitt T, Joubert LM, Kim M, Pham H, Chang J. Design and characterization of an injectable tendon hydrogel: A novel scaffold for guided tissue regeneration in the musculoskeletal system. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:1550–1561. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Curley CJ, Dolan EB, Otten M, Hinderer S, Duffy GP, Murphy BP. An injectable alginate/extra cellular matrix (ECM) hydrogel towards acellular treatment of heart failure. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s13346-018-00601-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grover GN, Rao N, Christman KL. Myocardial matrix-poly-ethylene glycol hybrid hydrogels for tissue engineering. Nanotechnology. 2014;25:014011. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/25/1/014011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Efraim Y, Sarig H, Cohen Anavy N, Sarig U, de Berardinis E, Chaw SY, Krishnamoorthi M, Kalifa J, Bogireddi H, Duc TV, et al. Biohybrid cardiac ECM-based hydrogels improve long term cardiac function post myocardial infarction. Acta Biomater. 2017;50:220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Waters R, Alam P, Pacelli S, Chakravarti AR, Ahmed RP, Paul A. Stem cell-inspired secretome-rich injectable hydrogel to repair injured cardiac tissue. Acta Biomater. 2018;69:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guruswamy Damodaran R, Vermette P. Tissue and organ decellularization in regenerative medicine. Biotechnol Prog. 2018;34:1494–1505. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seif-Naraghi SB, Salvatore MA, Schup-Magoffin PJ, Hu DP, Christman KL. Design and characterization of an injectable pericardial matrix gel: A potentially autologous scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2017–2027. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Karabekmez FE, Duymaz A, Moran SL. Early clinical outcomes with the use of decellularized nerve allograft for repair of sensory defects within the hand. Hand (NY) 2009;4:245–249. doi: 10.1007/s11552-009-9195-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pipino G, Risitano S, Alviano F, Wu EJ, Bonsi L, Vaccarisi DC, Indelli PF. Microfractures and hydrogel scaffolds in the treatment of osteochondral knee defects: A clinical and histological evaluation. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fitzpatrick LE, McDevitt TC. Cell-derived matrices for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Biomater Sci. 2015;3:12–24. doi: 10.1039/C4BM00246F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Loh QL, Choong C. Three-dimensional scaffolds for tissue engineering applications: Role of porosity and pore size. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2013;19:485–502. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2012.0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Defrere J, Franckart A. Freeze-dried fascia lata allografts in the reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament defects. A two- to seven-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;303:56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mahirogullari M, Ferguson CM, Whitlock PW, Stabile KJ, Poehling GG. Freeze-dried allografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26:625–637. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jackson DW, Grood ES, Cohn BT, Arnoczky SP, Simon TM, Cummings JF. The effects of in situ freezing on the anterior cruciate ligament. An experimental study in goats. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:201–213. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199173020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Freytes DO, Badylak SF, Webster TJ, Geddes LA, Rundell AE. Biaxial strength of multilaminated extracellular matrix scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2353–2361. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lin P, Chan WC, Badylak SF, Bhatia SN. Assessing porcine liver-derived biomatrix for hepatic tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1046–1053. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schenke-Layland K, Vasilevski O, Opitz F, Opitz F, König K, Riemann I, Halbhuber KJ, Wahlers T, Stock UA. Impact of decellularization of xenogeneic tissue on extracellular matrix integrity for tissue engineering of heart valves. J Struct Biol. 2003;143:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: Using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213–221. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Uygun BE, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yagi H, Izamis ML, Guzzardi MA, Shulman C, Milwid J, Kobayashi N, Tilles A, Berthiaume F, et al. Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix. Nat Med. 2010;16:814–820. doi: 10.1038/nm.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brown BN, Valentin JE, Stewart-Akers AM, McCabe GP, Badylak SF. Macrophage phenotype and remodeling outcomes in response to biologic scaffolds with and without a cellular component. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1482–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Reing JE, Brown BN, Daly KA, Freund JM, Gilbert TW, Hsiong SX, Huber A, Kullas KE, Tottey S, Wolf MT, Badylak SF. The effects of processing methods upon mechanical and biologic properties of porcine dermal extracellular matrix scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8626–8633. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Elder BD, Kim DH, Athanasiou KA. Developing an articular cartilage decellularization process toward facet joint cartilage replacement. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:722–727. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000367616.49291.9F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]