Abstract

Studies have demonstrated successful return to sport rates following Achilles tendon rupture and repair. The purpose of this study is to understand the subjective intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors influencing an athlete's return to pre-injury level of sport following Achilles tendon repair. Qualitative, semi-structured interviews of 23 athletes who had undergone Achilles tendon repair were conducted and analyzed to derive codes, categories, and themes. Three major themes affecting return to sport were elucidated from the interviews: personal motivation, shift in focus, and confidence in healthcare team. These findings can direct healthcare teams on how to better guide patients post-operatively.

Keywords: Qualitative interviews, Achilles tendon rupture, Achilles tendon repair, Return to sport

1. Introduction

Achilles tendon ruptures are most frequently acute injuries. One common mechanism is unexpected dorsiflexion and strong push-off of the foot in conjunction with calf contraction and knee extension.37 Recovery options for Achilles tendon rupture include open surgery, minimally invasive techniques, percutaneous repair such as Percutaneous Achilles Repair System (PARS), and nonsurgical treatment.31 PARS has been shown to have similar re-rupture rates relative to open surgery but has a lower likelihood of post-operative infection and sural neuritis and is therefore the preferred choice for many surgeons to help patients recover and return to sport.1,12,16,21,27,40

The discussion regarding recovery and return to sport is especially relevant as Achilles tendon rupture incidence has increased both in the general population and in specific sports such as major league baseball (MLB).15,19,22,23,38 Studies done on Achilles tendon repair show variable return to play rates ranging from 62% to 96%.13,20,38,45,48 It is important to note, however, that return to play is defined differently across studies and sometimes not at all. A systematic review by Zellers et al.48 estimated a return to sport rate of 77% or less due to this variation. Athletic performance post-surgery has also been researched with some studies reporting decreased ability in professional athletes the first year after repair followed by a rebound in athletic performance after two years.38,45

While quantitative research about Achilles tendon repair and return to sport has been growing,13,20,38,45,48 a qualitative assessment of athlete reasoning for return to sport has not yet been explored. Qualitative research on the subjective motivational factors influencing an athlete's decision to return to sport after other orthopaedic surgeries is a growing body of literature that has importantly informed what drives return to sport and players' versions of a “successful surgery.”5,10,33,44 With such varied return to sport rates, patients with Achilles tendon injuries may be misled by anecdotal information leading to confusion about their expected outcomes. Misunderstanding reasons why other athletes with Achilles tendon ruptures have or have not returned to sport may also cause patients to set inappropriate goals causing an unnecessarily negative experience. Thus, this study aimed to understand the subjective intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors influencing an athlete's return to pre-injury level of sport following Achilles tendon repair.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Patients between 18 and 60 years of age who had undergone primary Achilles tendon repair following rupture while participating in a sport were eligible for the study. Surgery was performed at a single university-associated hospital by a single fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeon between 2013 and 2018. All patients underwent surgery via PARS and had a minimum two-year follow up. Those who had been treated over seven years ago were excluded from the study to decrease recall bias. Approval from the university's Institutional Review Board was granted before study commencement.

2.2. Recruitment and data collection

This study followed a similar methodology to other qualitative assessments of return to sport.28,29,41, 42, 43, 44 Recruitment was performed in two phases. Eligible patients were initially contacted via mail and email, followed by a telephone inquiry. Informed consent was obtained from willing participants and interviews were scheduled. A single interviewer trained in qualitative methods (J.G.P.) conducted 30 to 45-minute audio-recorded telephone interviews using a study specific question guide derived from a review of sports medicine, psychology, and qualitative return to sport literature.4,34,36,42, 43, 44 Interviews employed the method of active passivity, meaning participants were not interrupted unless discussions deviated significantly from the aim of the interviews.25 Alphanumeric identifiers were assigned to each patient during interview transcription to preserve anonymity.

Semi-structured interviews were utilized to elucidate patient-derived themes and concepts regarding the decision to return to sport after Achilles tendon repair. The interviews consisted of open-ended questions with an iterative approach to the question guide, giving the interviewer freedom to probe deeper into patients’ responses and allowing patients to express their thoughts more thoroughly. The detailed information gathered from each interview was a unique feature of this qualitative study that could not be obtained via quantitative means alone.

The interviews were supplemented by Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) scores. PROMIS domains include Physical Function (PF) and Pain Interference (PI), administered as Computer Adaptive Tests (CATs).17,18 Data is reported as T-scores ranging between zero and 100 with 50 representing the physical function and pain interference of a healthy subset of the United States general population for reference. Functional improvement in patients has a positive correlation to PF T-scores while PI T-scores are inversely correlated with improvements in a patient's reported pain.11 PROMIS surveys were administered and collected using the REDCap electronic data capture tool.14

2.3. Data analysis

Sport participation was defined by three categories: type of sport, level of competition (i.e., recreational, varsity college/university, professional), and frequency of activity. Identical pre-injury and post-injury values were required in all three categories for a patient to classify as having returned to sport. Not returning to sport was defined as never achieving an equivalent status as described above at any post-operative timepoint. Sample size was determined when data saturation was obtained, meaning that collection stopped once new explanations, themes, and concepts no longer emerged from the interviews.26 Three members of the research team (J.G.P., V.K.T., M.P.M.) applied the method used by Strauss and Corbin39 of open coding, axial coding, and selective coding to each of the transcribed interviews.24 Specific phrases or ideas from the raw data were then grouped into commonalities that reflected categories. These categories were connected to classify them as broader themes. The themes generated from this analysis became the patient-generated factors influencing an athlete's decision to return to sport following Achilles tendon repair. Data analysis was performed using the R programing language (R Project for Statistical Computing; R Foundation). Welch's t-test and Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction were used to determine statistical significance of demographic data and PROMIS scores, defined as results with a p value less than 0.05.

3. Results

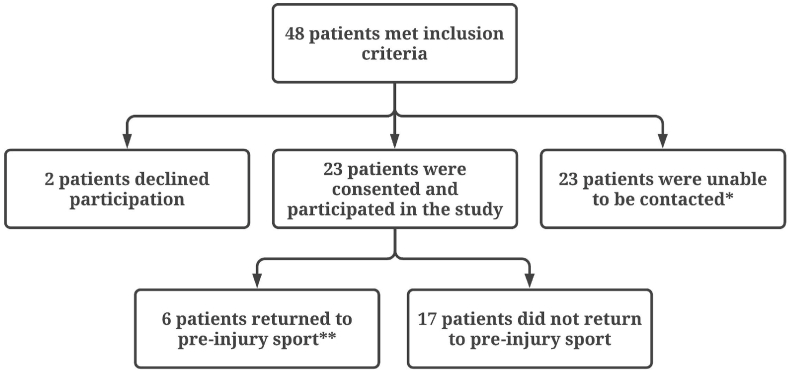

A total of 48 patients met the inclusion criteria for this study. Two patients declined participation, and 23 were unable to be contacted. Data saturation was reached after 23 patients were interviewed: Six (26%) returned to pre-injury level of sport as defined above (same type, level, and frequency of sport) while 17 (74%) did not. All patients participated in recreational-level sports. Study participation and patient demographics are outlined in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Study Participation *Wrong number, change of address, and no answer after repeated calls. **Patients with identical type of sport, level of competition, and frequency of activity before and after injury.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics. Data are reported as n (%) or as mean ± SD with p values calculated using Welch's t-test. Abbreviations: y is year(s), no. is number, mo is month(s).

| CHARACTERISTIC | PATIENTS WHO RETURNED TO PRE-INJURY SPORT (n = 6) | PATIENTS WHO DID NOT RETURN TO PRE-INJURY SPORT (n = 17) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 37.2 ± 12.2 | 38.9 ± 8.0 | 0.76 |

| Age group, no. of patients | 0.92 | ||

| 18-39 y | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | |

| 40-60 y | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | |

| Sex | 1 | ||

| Male | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | |

| Female | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | |

| Type of Sport | 0.90 | ||

| Basketball | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Soccer | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | |

| Paddle tennis/Tennis | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | |

| Working Out | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | |

| Other (Football, Gymnastics, Water Skiing, Volleyball, Warped Wall) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | |

| Length of post-surgery recovery, mo | 15.3 ± 6.9 | 13.3 ± 5.1 | 0.53 |

| Mean time since surgery, mo | 36.3 ± 12.1 | 60.4 ± 17.1 | <0.01 |

Three distinct themes were generated from the semi-structured interviews that described the motivators affecting return to sport after surgery: personal motivation, shift in focus, and confidence in healthcare team.

3.1. Personal motivation

All patients mentioned an inner drive helping them push through the challenges of rehab to return to physical activity. Though only six of 23 patients returned to their previous type, level, and frequency of sport participation, all 23 returned to physical activity (defined as any consistent form of exercise) and felt that their personal desire to do so was critical to their success. Patients referred to themselves as “positive, optimistic, and methodical to heal right” (patient A4), “resilient and passionate” (A10), “self-motivated” (B6), and “fully committed” (B11). Sports and physical fitness were key to the well-being and identity of many patients as they expressed, “I was determined with the number one goal to return to sport” (A12); “I remained active and competitive with staying in shape as a big priority” (B2); “I was dedicated and motivated to return to sport as it is important to my mental health” (B9); and “I never even considered the possibility of not returning to sport so I was patient, perseverant, and stayed in tune with my body” (B4). Others were also determined to continue physical activity but more open to adjusting as needed by saying, “I wanted to be active but also smart with a knowledge of my limits” (A7); “I am competitive and gained confidence over time” (A11); and “I trusted in the process and that I would be able to stay in shape” (B8). One unique example was a patient who works in the fitness industry. She stated, “As a manager, I wasn't required to return to physical activity for work, but fitness is my life, so I kept a positive attitude and knew I just had to do it to stay well and continue teaching classes I enjoy. I haven't done the specific exercise that injured me since, but I am still very active and enjoying my work” (B5).

3.2. Shift in focus

As mentioned previously, only six of 23 patients returned to their pre-injury level of sport even though all returned to athletic activity (which included any consistent exercise). The primary reason for this was a shift in focus which encompasses aging, moving to a new location, evolving life priorities, time constraints, and the realization that certain activities are not worth the possibility of reinjury. Patients that mentioned aging stated, “I am in my 40's now and have a kid and just wanted to back off” (A3); “I turned 40 and decided I couldn't compete anymore like when I was in college and it was time to give up soccer” (A6); “I'm in my 50's and my body just isn't what it used to be so I have no need to continue competing” (B6); and “I'm in a different stage of life now so I have less time for recreational sports” (A8). Other patients noted that they were injured doing something that they hadn't done before or never was important to them such as “I was trying to do 30 things before I turned 30 and a gymnastics class was the first one. I tore my Achilles and realized it was a bad idea for my body” (B4); “My teenage son was running up a warped wall (like on the show American Ninja Warrior) and I tried it against my better judgment; that never was something important to me” (B11); and “Basketball and other court sports simply aren't very significant to me so I didn't return” (A10). Another subset mentioned a lack of opportunity to participate in the sport they were injured in, so they shifted to other options. Examples include: “It is hard to find a court partner for squash and my work schedule doesn't line up well” (B9); “I moved to the suburbs where there are fewer people who play basketball, plus my wife doesn't want me playing competitive sports anymore with my injury history” (B8); and “I moved to Colorado where volleyball is less common, but I'm very involved in other sports such as trail running and skiing” (B7). A factor commonly involved in the shift in focus for patients is fear of injury, as 15 of 23 patients (65%) mentioned fear of reinjury and/or injuring their contralateral Achilles tendon. Interestingly, four of six patients (67%) who returned to sport expressed fear while 11 of 17 (65%) who did not return to sport expressed fear (P = 1). 19 of 23 patients (83%) said they met their recovery expectations: five of six (83%) who returned to sport (the one that did not said it took longer than expected to recover) and 14 of 17 (82%) who did not return to sport (two citing that they cannot jog like they expected to be able to and one citing an infection post-surgery) (P = 1).

3.3. Confidence in healthcare team

The majority of patients cited confidence in their surgeon and physical therapist, along with other members of the healthcare team, as an important factor in their recovery. Those who felt total trust in the skill and experience of their surgeon said, “I really trust my surgeon – I feel that he is the best one out there” (B1); “My surgeon gave me outstanding care and got me in very quickly” (B7); “The doctor supported me with an aggressive recovery” (B5); and “Because I trusted my doctor and he helped me set appropriate expectations, I felt I could do my part as well” (A9). Patients also felt encouraged and helped by their physical therapists, stating, “Physical therapy was very valuable to me so I never missed an appointment and worked hard throughout” (B2); “I told my physical therapist my goal was to completely return to physical activity and they helped me continue until I was no longer limping at all” (B5); “I set my expectations with my therapist from the beginning that I wanted to get back to sports rather than just be able to walk again and they helped me stay engaged and work hard to reach that goal” (B6); and “I went to a therapist I had worked with for other injuries and through aggressive and personalized rehab I was able to get way ahead of schedule such that I was completely functional 12 weeks out. I was very happy with the result” (B7). When asked what advice they would give patients who ruptured their Achilles tendon and were considering surgery, 17 of 23 patients (74%) focused on the importance of getting the best surgeon and physical therapist and completely committing to the full treatment regimen.

3.4. Secondary outcomes

Table 2 summarizes the secondary outcome measures. In comparing the cohorts that did and did not return to sport, there was no significant difference in PROMIS PF pre-operative (P = 0.27), PF 12-month post-operative (P = 0.81), PI pre-operative (P = 0.81), or PI 12-month post-operative (P = 0.12) scores. Each group saw both scores trend toward or past 50, with mean changes in PF (P = 0.30) and PI (P = 0.16) greater in those who did not return to sport, though this was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

PROMIS Scores. Data are reported as mean T-scores ± SD with p values calculated using Welch's t-test. Abbreviations: PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System; PF, Physical Function; PI, Pain Interference; Δ, Delta. *Three participants from the qualitative portion of the study who did not return to sport did not complete a follow-up survey and were excluded from the PROMIS score analysis.

| DESCRIPTION | OVERALL (n = 20)* | PATIENTS WHO RETURNED TO PRE-INJURY SPORT (n = 6) | PATIENTS WHO DID NOT RETURN TO PRE-INJURY SPORT (n = 14)* | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative PROMIS PF Score | 47.7 (18.4) | 54.4 (16) | 44.8 (19.2) | 0.27 |

| 12-Month Post-operative PROMIS PF Score | 58.4 (8.5) | 57.5 (11.4) | 58.7 (7.4) | 0.81 |

| Mean Δ in PROMIS PF Score | 10.7 (20.8) | 3.1 (19.7) | 13.9 (21.2) | 0.30 |

| Pre-operative PROMIS PI Score | 53.1 (11.7) | 52.2 (10.6) | 53.5 (12.5) | 0.81 |

| 12-Month Post-operative PROMIS PI Score | 48.8 (5.9) | 46.4 (6.2) | 41.3 (5.2) | 0.12 |

| Mean Δ in PROMIS PI Score | −10.2 (11.1) | −5.8 (6.9) | −12.2 (12.3) | 0.16 |

4. Discussion

Three themes affecting return to sport after Achilles tendon repair were derived from patient interviews in this study: personal motivation, shift in focus, and confidence in healthcare team.

4.1. Personal motivation

A unique finding in this study is that while only six of 23 patients returned to their previous type, level, and frequency of sport, all returned to physical activity and cited personal motivation as a major driving factor. Qualitative studies on return to sport following ACL reconstruction have found that many who did not return to sport felt they had a more cautious personality type, while most who did return classified themselves as self-motivators and very competitive.5,44 This difference may be due to the nature of the injuries in that the ACL is a deep ligament providing knee stability while the Achilles tendon is crucial to power in any lower limb movement by nature of attaching the calf muscles to the calcaneus. Another factor may be a discrepancy in age at time of rupture, as patients tend to rupture their Achilles tendon at an older age on average. Because of this, many patients with an Achilles tendon rupture may reset their expectations for future athletic activity and still feel very motivated while measuring success differently. Another study by Conti et al.8 interviewed professional basketball players who felt that motivation was essential to them returning to their prior physical conditions after injury. They said motivation is “fundamental in managing the challenges, setbacks and difficulties associated with the rehabilitation time-frame.” Patients recovering from Achilles Tendon tears similarly felt that there were various hurdles to overcome during the recovery process and that their determination and competitiveness helped them return to physical fitness.

Other studies on ACL reconstruction have shown that self-confidence, motivation, and optimism affect surgical outcomes.2,10,33 Everhart et al.10 goes on to surmise that “assessment of these factors to gauge a patient's psychological “readiness” for sports-related knee surgery has the potential to help guide individualized treatment recommendations.” This idea that surgical success is intricately tied to personality traits of the patient and that physicians can assist patients in their recovery process before a procedure is performed is one that should be further studied to empower patients of all personality types to return to the physical form they desire. Research on hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement and ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) reconstruction have also demonstrated the crucial role of self-efficacy in return to sport.28,42 The current study strengthens the notion that self-efficacy and motivation are important in the successful return to athletic activity following a wide array of injuries, though also demonstrates that one can possess these attributes and feel that they have succeeded in their physical recovery even if they have not returned to sport as previously defined.

4.2. Shift in focus

A shift in focus was the primary reason the patients of this study cited for not returning to sport. As previously stated, 83% of patients felt that they met their recovery expectations with no significant difference (P = 1) between those who did and did not return to sport. This may suggest that patients were satisfied with their outcome even if they did not return to their pre-injury type, level, and frequency of sport because they adjusted their expectations early on. Some patients in this study changed sports simply due to lack opportunity, moving to a new location, or new time constraints but were still pleased with their ability to return to physical activity and participate in sports. With this information, surgical success for an athlete may depend on their personal goals and intentions rather than if they returned to the sport that they were injured in. Helping athletes set appropriate expectations for their age, priorities, and lifestyle can help increase patient satisfaction. This same idea has been expressed in returning to sport after ACL reconstruction, with a focus on goal-reprioritization and decreasing negative emotions to keep patients satisfied with rehab and help them maintain a positive outlook on their progress toward returning to physical activity.6

Change in priorities is also a common theme in athletes not returning to sport across many injuries including knee, elbow, hip, and shoulder surgeries.28,42, 43, 44 Said changes for ACL reconstruction include an emphasis on education, change in career paths, lack of time, and family commitments.5,32,44 Athletes returning from shoulder injury have noted that aging largely prevented them from returning to sport, recognizing that their bodies simply aren't what they used to be.43 This was supported by the many athletes in this study stating that turning 30, 40, or 50 caused them to realize that they could no longer do what they used to. Another common factor leading to reprioritization after recovery from an injury is fear of reinjury.30,32,44 65% of participants in the current study mentioned that they are wary of reinjury or injury to the contralateral Achilles tendon, however there was not a significant difference (P = 1) between those that did and did not return to sport. These results suggest that fear did not affect whether athletes returned to their prior type/level/frequency of sport. A final example of adjusting expectations explained by Ardern et al.3 is that athletes recovering from ACL reconstruction who ended up returning to sport had pre-operatively estimated that they would return significantly faster than those who did not. This once again demonstrates that differing priorities and expectations often factor into return to sport. It is also of note that this study showed a much lower return to sport rate (26%) than seen in the literature (77%).48 This may be due to the strict definition of return to play that this study employed, the small sample size, and the cohort of patients that included only recreational athletes with an average age of 38.43 years.

4.3. Confidence in healthcare team

Another important recovery factor cited by the majority of patients was having confidence in their healthcare team with an emphasis on their orthopaedic surgeon and physical therapist. As previously stated, when asked what specific advice they would give other patients who ruptured their Achilles tendon and were considering surgery, 74% of participants emphasized the importance of finding the best orthopaedic surgeon and physical therapist and committing to the full treatment regimen. This parallels findings in similar studies in patients who underwent ACL reconstruction.5,33 Several participants in the study by Burland et al.5 felt that establishing good rapport with their physical therapist was paramount in their recovery. One participant in that study remarked, “If you don't have a relationship with them, I don't think you'd actually put in the work, and they wouldn't put in the work with you”. Paterno et al.33 helped to establish the importance of the patient-physical therapist relationship in recovery from ACL reconstruction. They defined some of the specific roles that a physical therapist can play in a patient's successful recovery: motivator, guide, booster of confidence, fosterer of perseverance, and coordinator of care.

A qualitative return to sport study of professional basketball players further noted the vital role of athletic trainers and other sports medicine professionals.8 The study defined specific types of assistance provided by these individuals including informational, emotional, and motivational support. They showed the benefit of sports medicine professionals informing patients of and elucidating potential return to sport scenarios during the recovery period. This is supported by the current study, as many patients commented on how helpful it was to discuss their current situation and goals for future athletic activity with their surgeon and physical therapist. Various other studies have also exhibited the positive influence, both psychological and physical, that medical professionals can have on athletes as they recover from injury. This includes increasing resilience and adherence to rehab, meeting psychological needs via open communication, providing a better understanding of the big picture to motivate patients to work hard, and getting patients actively involved in recovering from their injury to help them address relevant psychological aspects.3,7,9,35,46 One example of the power of a solid patient-therapist relationship from this study was the patient who cited working with a physical therapist who had already helped him recover from various injuries. He was very appreciative of the aggressive and personalized rehab plan his therapist provided him and was the quickest patient to return to athletics. With this wealth of evidence, it is apparent that building rapport with patients is critical for healthcare teams to effectively bring them towards satisfying recovery.

4.4. Secondary outcomes

The lack of statistical significance between the cohorts that did and did not return to sport supports the assertion that factors other than physical function and pain can affect return to sport following Achilles tendon repair. This demonstrates that while quantitative measures are important to assess, qualitative factors motivating return to sport play a key role in players’ decisions and are critical to evaluate. As previously stated, the most common reason for patients not returning to sport in this study was a shift in focus including aging, moving to a new location, lack of opportunity, and differing priorities. These factors affect both patients who do and do not return to sport. The greater change in both physical function and pain interference in those who did not return to sport is intriguing because, though not statistically significant, it could suggest that their greater overall improvement helped them meet their expectations at the same rate as those who did return to sport.

4.5. Limitations

Despite the strength of qualitative methods obtaining in-depth answers from patients, there were several limitations to this study. The patient population was restricted to a single academic surgeon and had sampling biases. The study population only included recreational athletes, making it less generalizable to varsity and professional athletes. Participation bias also is present as patients who agreed to be interviewed may hold different views from those who declined or could not be contacted. The lack of patient sex diversity could isolate the results to the male athlete; however, a study by Vosseller et al.47 demonstrated that at one institution the male to female ratio of Achilles tendon ruptures was 5.39:1 which is comparable to the 4.75:1 ratio of the current study. Recall bias and social desirability bias, in which patients want to appear stronger or more confident than in reality, may have also been involved because of the nature of interviews. The small sample size required to reach data saturation also diminishes PROMIS score statistical strength. Further investigations would benefit from adding validated surveys regarding psychological factors affecting return to sport in conjunction with a larger sample size and multiple standardized follow up PROMIS score timepoints to demonstrate change in PI and PF over time.

5. Conclusion

This study delineates personal motivation, shift in focus, and confidence in healthcare team as three main themes influencing a patient's return to pre-injury level of sport following Achilles tendon repair. Helping patients set appropriate expectations for return to sport and encouraging them through the challenges of rehab to reach their goals are critical to facilitating a positive experience. The study brings to light how an athlete may not return to pre-injury type, level, and frequency of sport after surgery while still meeting their expectations and feeling satisfied with their care and recovery if given appropriate tools, assistance, and advice. These findings can also help healthcare teams better educate patients throughout their post-operative journey.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Joshua G. Peterson: Writing - original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Project administration. Vehniah K. Tjong: Methodology, Resources, Conceptualization, Supervision. Mitesh P. Mehta: Investigation, Validation, Writing - original draft, Formal analysis. Bailey N. Goyette: Investigation, Writing - original draft. Milap Patel: Supervision, Investigation, Resources. Anish R. Kadakia: Supervision, Investigation, Resources.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

No outside funding or grants were received that assisted in this study. No authors have proprietary interests in the materials described in this study. Informed consent was obtained from subjects for this study.

Northwestern University IRB: STU00209802.

References

- 1.Alcelik I., Diana G., Craig A., Loster N., Budgen A. Minimally invasive versus open surgery for acute achilles tendon ruptures A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2017;83(3):387–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardern C.L. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction-not exactly a one-way ticket back to the preinjury level: a review of contextual factors affecting return to sport after surgery. Sport Health. 2015;7(3):224–230. doi: 10.1177/1941738115578131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardern C.L., Taylor N.F., Feller J.A., Whitehead T.S., Webster K.E. Psychological responses matter in returning to preinjury level of sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1549–1558. doi: 10.1177/0363546513489284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauman J. Returning to play: the mind does matter. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(6):432–435. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000186682.21040.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burland J.P., Toonstra J., Werner J.L. Decision to return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, Part I: a qualitative investigation of psychosocial factors. J Athl Train. 2018;53(5):452–463. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-313-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burland J.P., Toonstra J.L., Howard J.S. Psychosocial barriers after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical review of factors influencing postoperative success. Sport Health. 2019;11(6):528–534. doi: 10.1177/1941738119869333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clement D., Arvinen-Barrow M., Fetty T. Psychosocial responses during different phases of sport-injury rehabilitation: a qualitative study. J Athl Train. 2015;50(1):95–104. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conti C., di Fronso S., Pivetti M. Well-come back! Professional basketball players perceptions of psychosocial and behavioral factors influencing a return to pre-injury levels. Front Psychol. 2019;10:222. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covassin T., Crutcher B., Bleecker A. Postinjury anxiety and social support among collegiate athletes: a comparison between orthopaedic injuries and concussions. J Athl Train. 2014;49(4):462–468. doi: 10.4085/1062-6059-49.2.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everhart J.S., Best T.M., Flanigan D.C. Psychological predictors of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction outcomes: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(3):752–762. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilley J., Bell R., Lima M. Prospective patient reported outcomes (PRO) study assessing outcomes of surgically managed ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41(2):206–210. doi: 10.1177/1071100719891157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grassi A., Amendola A., Samuelsson K. Minimally invasive versus open repair for acute achilles tendon rupture: meta-analysis showing reduced complications, with similar outcomes, after minimally invasive surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(22):1969–1981. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grassi A., Rossi G., D'Hooghe P. Eighty-two per cent of male professional football (soccer) players return to play at the previous level two seasons after Achilles tendon rupture treated with surgical repair. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(8):480–486. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holm C., Kjaer M., Eliasson P. Achilles tendon rupture-treatment and complications: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(1):e1–10. doi: 10.1111/sms.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu A.R., Jones C.P., Cohen B.E. Clinical outcomes and complications of percutaneous achilles repair system versus open technique for acute achilles tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(11):1279–1286. doi: 10.1177/1071100715589632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hung M., Baumhauer J.F., Latt L.D. Validation of PROMIS ® Physical Function computerized adaptive tests for orthopaedic foot and ankle outcome research. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(11):3466–3474. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung M., Clegg D.O., Greene T., Weir C., Saltzman C.L. A lower extremity physical function computerized adaptive testing instrument for orthopaedic patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(4):326–335. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huttunen T.T., Kannus P., Rolf C., Felländer-Tsai L., Mattila V.M. Acute achilles tendon ruptures: incidence of injury and surgery in Sweden between 2001 and 2012. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2419–2423. doi: 10.1177/0363546514540599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack R.A., 2nd, Sochacki K.R., Gardner S.S. Performance and return to sport after achilles tendon repair in national football league players. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(10):1092–1099. doi: 10.1177/1071100717718131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kołodziej L., Bohatyrewicz A., Kromuszczyńska J., Jezierski J., Biedroń M. Efficacy and complications of open and minimally invasive surgery in acute Achilles tendon rupture: a prospective randomised clinical study--preliminary report. Int Orthop. 2013;37(4):625–629. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1737-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lantto I., Heikkinen J., Flinkkilä T., Ohtonen P., Leppilahti J. Epidemiology of Achilles tendon ruptures: increasing incidence over a 33-year period. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(1):e133–138. doi: 10.1111/sms.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leppilahti J., Puranen J., Orava S. Incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67(3):277–279. doi: 10.3109/17453679608994688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lingard L., Albert M., Levinson W. Grounded theory, mixed methods, and action research. BMJ. 2008;337:a567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39602.690162.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall M.N. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam Pract. 1996;13(6):522–525. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.6.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGee R., Watson T., Eudy A. Anatomic relationship of the sural nerve when performing Achilles tendon repair using the percutaneous Achilles repair system, a cadaveric study. Foot Ankle Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta M.P., Tjong V.K., Peterson J.G., Christian R.A., Gryzlo S.M. A qualitative assessment of return to sport following ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in baseball players. J Orthop. 2020;21:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2020.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan A.M., Fernandez C.E., Terry M.A., Tjong V. A qualitative assessment of return to sport in collegiate athletes: does gender matter? Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9689. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nwachukwu B.U., Adjei J., Rauck R.C. How much do psychological factors affect lack of return to play after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(5) doi: 10.1177/2325967119845313. 2325967119845313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel M.S., Kadakia A.R. Minimally invasive treatments of acute achilles tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Clin. 2019;24(3):399–424. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel N.K., Sabharwal S., Hadley C., Blanchard E., Church S. Factors affecting return to sport following hamstrings anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in non-elite athletes. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2019;29(8):1771–1779. doi: 10.1007/s00590-019-02494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paterno M.V., Schmitt L.C., Thomas S. Patient and parent perceptions of rehabilitation factors that influence outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and clearance to return to sport in adolescents and young adults. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(8):576–583. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2019.8608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Podlog L., Dimmock J., Miller J. A review of return to sport concerns following injury rehabilitation: practitioner strategies for enhancing recovery outcomes. Phys Ther Sport. 2011;12(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podlog L., Dionigi R. Coach strategies for addressing psychosocial challenges during the return to sport from injury. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(11):1197–1208. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.487873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podlog L., Eklund R.C. Returning to competition after a serious injury: the role of self-determination. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(8):819–831. doi: 10.1080/02640411003792729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose N.G.W., Green T.J. vol. 9. Elsevier; 2018. Ankle and foot; pp. 634–658. (Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice [Internet]). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saltzman B.M., Tetreault M.W., Bohl D.D. Analysis of player statistics in major league baseball players before and after achilles tendon repair. HSS J. 2017;13(2):108–118. doi: 10.1007/s11420-016-9540-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strauss A., Corbin J. 1. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. Basis of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tejwani N.C., Lee J., Weatherall J., Sherman O. Acute achilles tendon ruptures: a comparison of minimally invasive and open approach repairs followed by early rehabilitation. Am J Orthoped. 2014;43(10):E221–E225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tjong V.K., Baker H.P., Cogan C.J. Concussions in ncaa varsity football athletes: a qualitative investigation of player perception and return to sport. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2017;1(8) doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-17-00070. e070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tjong V.K., Cogan C.J., Riederman B.D., Terry M.A. A qualitative assessment of return to sport after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(11) doi: 10.1177/2325967116671940. 2325967116671940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tjong V.K., Devitt B.M., Murnaghan M.L., Ogilvie-Harris D.J., Theodoropoulos J.S. A qualitative investigation of return to sport after arthroscopic bankart repair: beyond stability. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(8):2005–2011. doi: 10.1177/0363546515590222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tjong V.K., Murnaghan M.L., Nyhof-Young J.M., Ogilvie-Harris D.J. A qualitative investigation of the decision to return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: to play or not to play. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):336–342. doi: 10.1177/0363546513508762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trofa D.P., Miller J.C., Jang E.S. Professional athletes' return to play and performance after operative repair of an achilles tendon rupture. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(12):2864–2871. doi: 10.1177/0363546517713001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Truong L.K., Mosewich A.D., Holt C.J. Psychological, social and contextual factors across recovery stages following a sport-related knee injury: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(19):1149–1156. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vosseller J.T., Ellis S.J., Levine D.S. Achilles tendon rupture in women. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(1):49–53. doi: 10.1177/1071100712460223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zellers J.A., Carmont M.R., Grävare Silbernagel K. Return to play post-Achilles tendon rupture: a systematic review and meta-analysis of rate and measures of return to play. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(21):1325–1332. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]