Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether impaired plantar cutaneous vibration perception contributes to postural disturbance in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH).

Methods

Three different groups were tested: iNPH-patients (iNPH), iNPH-patients after surgical shunt therapy (iNPH shunt), and healthy subjects (HS). Postural performance was quantified during quiescent stance on a pressure distribution platform. Vibration perception threshold (VPT) was measured using a modified vibration exciter to apply stimuli to the plantar foot.

Results

Regarding postural performance, iNPH showed significantly higher values for all investigated center of pressure (COP)-parameters compared to HS, which suggests impaired postural control. Shunted patients presented a tendency towards better postural control in contrast to non-shunted patients. VPTs did not differ significantly between all investigated groups, which suggests comparable plantar cutaneous vibration perception.

Conclusion

Patients with iNPH suffer from poor postural stability, whereas shunting tends to affect postural performance positively. Plantar cutaneous vibration perception seems to be comparable between all investigated study groups. Consequently, postural disturbance in iNPH cannot clearly be ascribed to defective plantar cutaneous input.

Keywords: Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, Shunt, Plantar cutaneous vibration perception, Postural performance

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus; Shunt; Plantar cutaneous vibration perception; Postural performance.

1. Introduction

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) is a neurological disease with abnormal intracranial fluid dynamics and ventricular enlargement, which affects the functionality of various cortical and periventricular subcortical structures [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Consequently, iNPH manifests with three hallmark symptoms: dementia, urinary incontinence, and postural disturbance. The latter, being the earliest and most prevalent symptom, affects stance as well as gait [1, 7]. Neurosurgical therapy of iNPH with ventriculoperitoneal shunts (VP-shunts) generally normalizes intracranial fluid dynamics, and consequently eases postural disturbance [1, 8, 9].

Among other factors, postural disturbance can be caused by dysfunction of the visual, vestibular, and somatosensory systems and the defective integration of their afferent inputs [9, 10, 11]. Since both the visual [12, 13, 14] and the vestibular [15, 16] systems show deficiencies in iNPH, the somatosensory system might be affected as well. Surprisingly, only few studies have examined the somatosensory system in iNPH, presenting discordant results [8, 9, 11, 15]. While Lundin et al. [9] found significantly impaired postural performance for somatosensory-dominated balance test conditions in iNPH compared to healthy elderly subjects, Bäcklund et al. [8] reported comparable somatosensory functionality. Shunting did not reveal considerable effects for somatosensory-dominated balance test conditions [9]. These studies examined the contribution of the somatosensory system to postural performance as a whole. However, the somatosensory system comprises primarily two subsystems, namely proprioception and cutaneous perception [10, 17]. Since their relative input to postural performance is still unknown [18], previous studies could not distinguish whether dysfunction of both or just one subsystem contributes to symptomatic postural disturbance in iNPH. Therefore, it seems crucial to investigate the functionality of single subsystems individually. Given the fact that the soles of our feet are the only direct contact between the body and the ground while standing and walking, the relevance of plantar cutaneous mechanoreceptor input for postural performance has already been confirmed [18, 19, 20].

Since ventricular enlargement of iNPH and subsequent blood flow reduction affects the functionality of several cortical and periventricular structures [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 21], the pathophysiological mechanisms of iNPH could affect plantar cutaneous perception as well. Showing this might help to better understand the cause of postural disturbance in iNPH. Moreover, it could be beneficial for diagnosing and counselling patients about appropriate treatment, as well as differentiating between various disease states. Thinking ahead, impairments could potentially be treated by stimulating the foot sole, e.g. via textured insoles [22, 23] or vibration stimuli [24, 25] to normalize plantar cutaneous perception and consequently to enhance postural performance in iNPH.

The aim of this study was twofold:

First, we aimed to investigate postural performance in iNPH-patients, iNPH-patients with shunt, and healthy subjects. We hypothesized that postural performance in iNPH is impaired compared to healthy subjects. Furthermore, we hypothesized that shunting improves postural performance in iNPH.

Second, we aimed to investigate plantar cutaneous perception within the same study groups. Based on the pathophysiological mechanisms of iNPH, we hypothesized that plantar cutaneous perception is affected in iNPH. Additionally, we hypothesized that shunting normalizes plantar cutaneous perception.

2. Participants & methods

2.1. Participants

Three different groups were investigated: iNPH-patients (iNPH), iNPH-patients after surgical shunt therapy (iNPH shunt), and healthy subjects (HS). Demographic and clinical data are presented in Table 1. Prior to data collection, all participants were briefed about the purpose of this study and provided written informed consent. All procedures were conducted according to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the local ethics committee (IRB number: 023/14-ff).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data (mean ± SD).

| iNPH | iNPH shunt | HS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 18 | 20 |

| gender | ♂ 7/♀ 5 | ♂ 15/♀ 3 | ♂ 12/♀ 8 |

| age [yrs] | 74.6 ± 4.1 | 72.0 ± 7.0 | 71.5 ± 3.6 |

| modified Kiefer-Score | 3.4 ± 2.6 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | - |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | 27.1 ± 1.9 | 27.9 ± 2.0 | - |

| post shunt measurement interval [yrs] | - | 1.5 ± 1.6 | - |

2.1.1. INPH-patients

All patients were tested during the iNPH consultation at the Department of Neurosurgery (University Hospital Leipzig). Patients were diagnosed based on clinical criteria for iNPH including invasive and non-invasive tests and ventricular enlargement using magnetic resonance imaging [6, 7, 26]. Implanted shunts were gravity-assisted VP-shunts (proGAV or GAV, Fa. Miethke, Potsdam, Germany). All enrolled iNPH shunt patients were positive shunt responders confirmed with clinical examination and were investigated at least three months after shunt surgery. Non-shunt-responding patients and patients suffering from severe cognitive deficits (Mini-Mental State Examination <21) were excluded from this study. Secondary pathologies involving the somatosensory system (e.g. diabetes mellitus, polyneuropathy) were ruled out.

2.1.2. Healthy subjects

Age-matched healthy subjects were examined in the laboratory of the Department of Human Locomotion (Chemnitz University of Technology). They neither suffered from any injuries or diseases, nor took medication with potential to interfere with postural performance, cognition, or cutaneous perception.

2.2. Equipment & testing procedures

2.2.1. Posturography

Postural performance was quantified using a pressure distribution platform (Zebris FDM 1.5; Isny, Germany). All participants were instructed to stand as still as possible in bipedal stance while barefoot, with upright posture, both arms hanging down loosely, and directing their gaze ahead. Stance width was chosen individually. All participants performed two consecutive trials lasting 30 s each, while data was collected at 100 Hz. Plantar skin temperatures were monitored, since alterations might affect postural performance [18, 19, 27].

2.2.2. Plantar vibration examination

A modified vibration exciter (Tira Vib, TV51075, Schalkau, Germany) was implemented to quantify vibration perception thresholds (VPT). An oscillating brass probe, protruding through a hole in an aluminum foot rest, applied vibration stimuli to the plantar foot (Figure 1). Vibration frequency was set to 30 Hz, a frequency which primarily innervates fast adapting (FA I) cutaneous afferents (Meissner corpuscles) [28]. Vibration frequency and amplitude were verified by an accelerometer, which was affixed to the probe. Since it has been shown that changes in skin temperature affect tactile perception, the foot rest was equipped with a thermal element, which was adjusted to approx. 20 °C to assure comparability [18, 19, 20]. Prior to the examination, all participants underwent an acclimatization period of approx. 10 min by placing their bare feet onto the aluminum plate. Subsequently, one of the two tested anatomical locations, center of the heel and the head of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (met I) of the right foot, was positioned onto the probe. Since alterations of the force applied to the probe may affect tactile perception, force was controlled using a sensor (Hottinger U9B) [29]. An incremental forced-choice algorithm, modified after Mildren et al. [30], was implemented to automatically detect the VPT. Therefore, participants had to push a handheld trigger as soon as they perceived a vibration stimulus at the tested anatomical location. The recorded VPT was defined as the smallest perceived vibration stimulus. One test trial and three main trials were executed for each participant and anatomical location, respectively.

Figure 1.

Plantar vibration examination at the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

2.3. Data processing & statistical analysis

2.3.1. Posturography

Raw pressure data were imported into MATLAB R2017b (MathWorksTM, Natick, MA, USA) to apply a low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 15 Hz [1] and to calculate center of pressure (COP)-parameters. Subsequently, the mean was calculated over both collected trials for each participant and COP-parameter. Comparisons between groups were accomplished using Kruskal-Wallis-Tests followed by Dunn-Bonferroni posthoc-tests and Bonferroni adjustment to α = 0.0167. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for comparisons within groups, between anterior-posterior (AP) vs. medio-lateral (ML) directions.

2.3.2. Plantar vibration examination

The mean over three collected VPTs for each participant was used to compare between groups performing Kruskal-Wallis-Tests followed by Dunn-Bonferroni posthoc-tests. Due to three investigated study groups and two tested anatomical locations, the level of significance was Bonferroni adjusted to α = 0.0083. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for comparisons between both anatomical locations within groups.

3. Results

3.1. Posturography

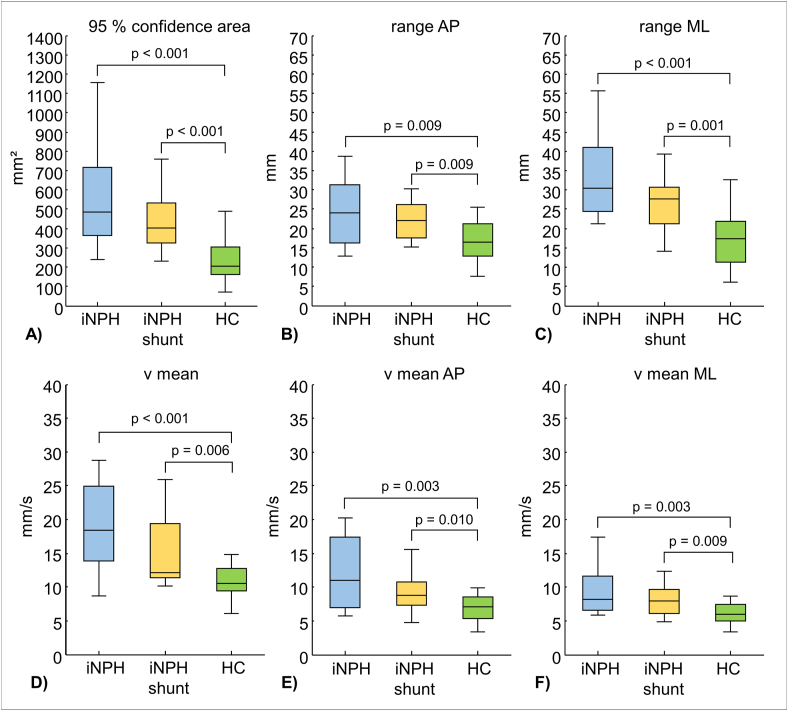

Self-selected stance width revealed broader stance for patients compared to healthy subjects: iNPH 16.2 cm ± 3.1 cm; iNPH shunt 13.7 cm ± 3.9 cm; HS 11.6 ± 3.1 cm. Differences in stance width between iNPH and HS were statistically significant (p = 0.002). Both iNPH and iNPH shunt revealed higher values for all investigated COP-parameters, which were statistically significant compared to HS (p < 0.0167) (Figure 2). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were found for any COP-parameter, when comparing iNPH and iNPH shunt. Within groups, no significant differences were found between COP-parameters range AP vs. range ML and v mean AP vs. v mean ML.

Figure 2.

Group comparisons including statistically significant p-values for COP-parameters: A) 95% confidence area (ellipse-shaped area, comprising 95 % of COP-data); B) range AP (range of captured COP-data along AP direction); C) range ML (range of captured COP-data along ML direction); D) v mean (mean velocity calculated over each frame); E) v mean AP (mean velocity calculated over each frame in AP direction); F) v mean ML (mean velocity calculated over each frame in ML direction); the level of significance was Bonferroni adjusted to α = 0.0167.

3.2. Plantar vibration perception

Due to 6 dropouts, data from 12 iNPH shunt patients were processed. The comparisons of VPT between all groups revealed no statistically significant differences for either anatomical location (Figure 3). Comparing data from both anatomical locations within each group showed higher values for met I than heel, though this was not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

VPT amplitude group comparison for both anatomical locations: A) heel, B) met I; the level of significance was Bonferroni adjusted to α = 0.0083. No significant differences could be found.

4. Discussion

4.1. Posturography

The first aim of this study was to investigate postural performance in iNPH. We hypothesized that postural performance in iNPH is impaired compared to healthy subjects. All investigated COP-parameters revealed significantly higher values for iNPH (Figure 2), which confirms our hypothesis.

Our results are in line with several studies [1, 8, 9, 15, 31, 32]. Although iNPH-patients chose to perform quiescent stance with significantly increased stance width, we found that postural disturbance in iNPH presents as significantly increased COP areas and greater sway displacements in the anterior-posterior and medio-lateral directions compared to HS. It is noteworthy that patients’ sway displacement in the medio-lateral direction seems to be more prevalent compared to the anterio-posterior direction. Similarly, Nikaido et al. also found distinct postural impairments in the medio-lateral direction [33]. Therefore, it seems that broad-based stance as well as gait are strategies to increase the base of support and consequently compensate for postural instability in the medio-lateral direction [8, 33, 34, 35]. Furthermore, iNPH-patients presented significantly increased COP velocities in both directions (medio-lateral, anterior-posterior) compared to HS. Likewise, Blomsterwall et al. found higher backward-directed velocities, which might be associated with the risk of falling backwards [13, 31].

This sway pattern may reflect the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of iNPH. Although iNPH was initially described by Salomón Hakim in 1965 [7], a variety of mechanisms are still under debate. Generally, it is presumed that enlarged ventricles and peak-like pressure waves affect the functionality of various cortical and periventricular subcortical structures and pathways [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 36]. Consequently, demyelination, brain atrophy, neurotransmitter signaling abnormalities, and cerebral blood flow depression accompanied by accumulation of toxic metabolites are presumed to cause postural disturbance and hypokinetic gait [5, 6]. Therefore, motor symptoms in iNPH seem to be caused by central dysfunctions and additionally by the defective integration of afferent inputs from the visual [12, 13, 14], vestibular [15, 16] and somatosensory systems [8, 9, 11, 15]. However, the fundamental mechanisms of defective afferent input, especially from the somatosensory system are still unclear.

Although the pathophysiology of iNPH is complex, inserting a ventriculoperitoneal shunt is considered the standard treatment [34, 37]. Since gait and postural disturbances generally respond to shunt surgery [1, 34, 37], we hypothesized that shunting improves postural performance in iNPH. However, we did not find significantly superior postural performance for shunted patients compared to non-shunted patients. Hence, our results do not support this hypothesis. Nevertheless, we found a tendency towards better postural performance for shunted patients (Figure 2).

The discrepancy between our results and other studies with significant postural improvements after shunting [1, 8, 9] might have several reasons. One reason might be our cross-sectional study design, which did not investigate pre vs. post shunt response for identical patients, but independent study groups. Moreover, since shunt-related improvements show a time dependent decline [37, 38], the highly variable post shunt measurement intervals of our shunted patients might be another reason for non-significant results. Finally, patients’ highly interindividual variable COP-data and the small sample size may have influenced our results.

4.2. Plantar cutaneous vibration perception

The second aim of this study was to investigate cutaneous perception in iNPH by applying vibration stimuli to the plantar foot. Since ventricular enlargement of iNPH affects the functionality of several cortical and periventricular structures [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 21], we hypothesized that plantar cutaneous vibration perception is affected in iNPH, whereas shunting normalizes plantar cutaneous vibration perception.

Surprisingly, the VPTs did not differ significantly between all investigated groups, which suggests comparable functionality (Figure 3). Therefore, our results do not support these hypotheses. As our study is the first specifically investigating cutaneous perception in iNPH, it is challenging to explain our findings based on related literature. Only one older study has investigated the functionality and integration of proprioceptive and plantar tactile stimuli in patients suffering from low pressure hydrocephalus [11]. Estañol [11] found that proprioceptive stimuli induced by sudden ankle movements may trigger leg stiffening by increasing muscle tone. However, absent Babinski signs in the majority of the patients suggest that tactile stimuli are of no importance in eliciting perseveration of posture. Since Estañol's study enrolled only six patients suffering from low pressure hydrocephalus, which is a rare type of normal pressure hydrocephalus, those results might not be comparable with our study results [39].

Nevertheless, there are some physiological and methodological assumptions, which might help to explain our results:

First, cerebral and neuronal structures, which are involved in transmitting and processing afferent cutaneous stimuli of the plantar foot, like the ventrobasal complex of the thalamus and Brodmann areas 1 and 3b of the primary somatosensory cortex [17], might not be significantly affected by ventricular enlargement and subsequent cerebral blood flow reduction. The study of Sasaki et al. may support this hypothesis. By investigating 30 hydrocephalic patients via single photon emission computed tomography they revealed dominant blood flow reduction in cerebral and neuronal structures, which are not primarily responsible for plantar cutaneous perception [36].

Second, potentially disturbed pathophysiological integration and degeneration of epidermal nerve fibers and mechanoreceptors (Meissner corpuscles) in iNPH could be reweighted by recruiting inactive mechanoreceptors. This has been demonstrated at least for cutaneous nociceptors. So-called “sleeping nociceptors” only become active and responsive in the presence of specific conditions, like inflammation [40]. Hence, it is conceivable that additionally recruited inactive mechanoreceptors compensate potentially impaired processing and receptor activity and, we therefore, could not find any significant differences.

Methodological reasons might be the high variability of plantar vibration perception data, which can be even found in healthy subjects [41, 42]. As already mentioned, a higher number of patients may lead to clearer results. Moreover, since we only measured vibration perception at 30 Hz, which primarily stimulates Meissner corpuscles in glabrous skin, we do not know about the functionality of other mechanoreceptors, which are more sensitive to higher frequencies, e.g. Vater-Pacini corpuscles [28].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that patients with iNPH suffer from poor postural stability compared to healthy subjects, which is even noticeable in quiescent stance. Shunting tended to affect postural performance positively. Plantar vibration perception seems to be comparable between all investigated study groups. Hence, postural disturbance in iNPH cannot clearly be ascribed to defective plantar cutaneous input. Further research should aim to investigate postural performance under more challenging conditions, like controlled perturbation. Moreover, subsequent studies should focus on examining the functionality of various cutaneous receptors, which are sensitive to vibration stimuli at different frequencies, pressure, temperature or pain.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Tobias Heß: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Thomas L. Milani: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Jürgen Meixensberger: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Matthias Krause: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Tobias Heß was supported by the Sächsische Aufbaubank [grant number: 100235478]. The publication of this article was funded by Chemnitz University of Technology.

Data availability statement

Data included in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants attending this study and Lisa Peterson for proofreading the article as a native speaker.

References

- 1.Czerwosz L., Szczepek E., Blaszczyk J.W., Sokolowska B., Dmitruk K., Dudzinski K., Jurkiewicz J., Czernicki Z. Analysis of postural sway in patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus: effects of shunt implantation. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2009;14(Suppl 4):53. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-S4-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bateman G.A. The pathophysiology of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: cerebral ischemia or altered venous hemodynamics? AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008;29(1):198–203. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuba H., Inamura T., Ikezaki K., Inoha S., Nakamizo A., Shono T., Fukui K., Fukui M. Gait disturbance in patients with low pressure hydrocephalus. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2002;9(1):33–36. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pindrik J., Bastian A., Rigamonti D. Pathophysiology of gait dysfunction in normal pressure hydrocephalus. In: Rigamonti D., editor. Adult Hydrocephalus. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2014. pp. 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Relkin N., Katzen H. In: The Pathophysiologic Basis of Cognitive Dysfunction in Idiopathic normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. Rigamonti D., editor. Cambridge University Press; 2014. pp. 70–79. (Adult Hydrocephalus). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Relkin N., Marmarou A., Klinge P., Bergsneider M., Black P.M. Diagnosing idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(3 Suppl):S4–S16. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000168185.29659.c5. discussion ii-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakim S., Adams R.D. The special clinical problem of symptomatic hydrocephalus with normal cerebrospinal fluid pressure. J. Neurol. Sci. 1965;2(4):307–327. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(65)90016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bäcklund T., Frankel J., Israelsson H., Malm J., Sundström N. Trunk sway in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus-Quantitative assessment in clinical practice. Gait Posture. 2017;54:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundin F., Ledin T., Wikkelso C., Leijon G. Postural function in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus before and after shunt surgery: a controlled study using computerized dynamic posturography (EquiTest) Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2013;115(9):1626–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sturnieks D.L., St George R., Lord S.R. Balance disorders in the elderly. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2008;38(6):467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estañol B.V. Gait apraxia in communicating hydrocephalus. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1981;44(4):305–308. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.4.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wikkelsö C., Blomsterwall E., Frisén L. Subjective visual vertical and Romberg's test correlations in hydrocephalus. J. Neurol. 2003;250(6):741–745. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blomsterwall E., Svantesson U., Carlsson U., Tullberg M., Wikkelso C. Postural disturbance in patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2000;102(5):284–291. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.102005284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asensio-Sánchez V.M., Martín-Prieto A. Colour vision abnormality as the only manifestation of normal pressure hydrocephalus. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2018;93(1):35–37. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abram K., Bohne S., Bublak P., Karvouniari P., Klingner C.M., Witte O.W., Guntinas-Lichius O., Axer H. The effect of spinal tap test on different sensory modalities of postural stability in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra. 2016;6(3):447–457. doi: 10.1159/000450602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Böttcher N., Bremova T., Feil K., Heinze C., Schniepp R., Strupp M. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: increase of utricular input in responders to spinal tap test. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016;127(5):2294–2301. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnitzler A., Seitz R.J., Freund H.-J. 2000. The Somatosensory System; pp. 291–329. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Germano A.M.C., Schmidt D., Milani T.L. Effects of hypothermically reduced plantar skin inputs on anticipatory and compensatory balance responses. BMC Neurosci. 2016;17(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12868-016-0279-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Germano A.M.C., Heß T., Schmidt D., Milani T.L. Effects of plantar hypothermia on quasi-static balance: two different hypothermic procedures. Gait Posture. 2018;60:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Germano A.M.C., Schlee G., Milani T.L. Effect of cooling foot sole skin receptors on achilles tendon reflex. Muscle Nerve. 2016;53(6):965–971. doi: 10.1002/mus.24994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nutt J.G. Higher-level gait disorders: an open frontier. Mov. Disord. 2013;28(11):1560–1565. doi: 10.1002/mds.25673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu F., Cole M.H., Davids K.W., Hennig E.M., Silburn P.A., Netscher H., Kerr G.K., van Beers R.J. Effects of textured insoles on balance in people with Parkinson’s disease. PloS One. 2013;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Morais Barbosa C., Barros Bértolo M., Zonzini Gaino J., Davitt M., Sachetto Z., de Paiva Magalhães E. The effect of flat and textured insoles on the balance of primary care elderly people: a randomized controlled clinical trial. CIA. 2018;13:277–284. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S149038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kavounoudias A., Roll R., Roll J.-P. Specific whole-body shifts induced by frequency-modulated vibrations of human plantar soles. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;266(3):181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kavounoudias A., Roll R., Roll J.-P. Foot sole and ankle muscle inputs contribute jointly to human erect posture regulation. J. Physiol. 2001;532(3):869–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0869e.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahr C.V., Dengl M., Nestler U., Reiss-Zimmermann M., Eichner G., Preuss M., Meixensberger J. Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: diagnostic and predictive value of clinical testing, lumbar drainage, and CSF dynamics. J. Neurosurg. 2016;125(3):591–597. doi: 10.3171/2015.8.JNS151112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eils E., Behrens S., Mers O., Thorwesten L., Völker K., Rosenbaum D. Reduced plantar sensation causes a cautious walking pattern. Gait Posture. 2004;20(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(03)00095-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toma S., Nakajima Y. Response characteristics of cutaneous mechanoreceptors to vibratory stimuli in human glabrous skin. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;195(1):61–63. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11776-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagander L.G., Midani H.A., Kuskowski M.A., Parry G.J.G. Quantitative sensory testing: effect of site and pressure on vibration thresholds. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2000;111(6):1066–1069. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mildren R.L., Strzalkowski N.D.J., Bent L.R. Foot sole skin vibration perceptual thresholds are elevated in a standing posture compared to sitting. Gait Posture. 2016;43:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blomsterwall E., Frisén L., Wikkelsö C. Postural function and subjective eye level in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J. Neurol. 2011;258(7):1341–1346. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5943-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soelberg Sørensen P., Jansen E.C., Gjerris F. Motor disturbances in normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Special reference to stance and gait. Arch. Neurol. 1986;43(1):34–38. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520010030016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikaido Y., Akisue T., Kajimoto Y., Tucker A., Kawami Y., Urakami H., Iwai Y., Sato H., Nishiguchi T., Hinoshita T., Kuroda K., Ohno H., Saura R. Postural instability differences between idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and Parkinson's disease. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018;165:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stolze H., Kuhtz-Buschbeck J.P., Drücke H., Jöhnk K., Diercks C., Palmié S., Mehdorn H.M., Illert M., Deuschl G. Gait analysis in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus – which parameters respond to the CSF tap test? Clin. Neurophysiol. 2000;111(9):1678–1686. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J.-W., Kwon Y., Jeon H.-M., Bang M.-J., Jun J.-H., Eom G.-M., Lim D.-H. Feet distance and static postural balance: implication on the role of natural stance. Bio Med. Mater. Eng. 2014;24(6):2681–2688. doi: 10.3233/BME-141085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki H., Ishii K., Kono A.K., Miyamoto N., Fukuda T., Shimada K., Ohkawa S., Kawaguchi T., Mori E. Cerebral perfusion pattern of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus studied by SPECT and statistical brain mapping. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2007;21(1):39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF03033998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torsnes L., Blafjelldal V., Poulsen F.R. 2014. Treatment and Clinical Outcome in Patients with Idiopathic normal Pressure Hydrocephalus-Aa Systematic Review. Denmark. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meier U.a.L.J. Brain Edema XIII. Springer Vienna; Vienna: 2006. Clinical outcome of patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus three years after shunt implantation; pp. 377–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalani M.Y.S., Turner J.D., Nakaji P. Treatment of refractory low-pressure hydrocephalus with an active pumping negative-pressure shunt system. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2013;20(3):462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woolf C.J., Ma Q. Nociceptors--noxious stimulus detectors. Neuron. 2007;55(3):353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zippenfennig C., Niklaus L., Karger K., Milani T.L. Subliminal electrical and mechanical stimulation does not improve foot sensitivity in healthy elderly subjects. Clin. Neurophysiol. Prac. 2018;3:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cnp.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holowka N.B., Wynands B., Drechsel T.J., Yegian A.K., Tobolsky V.A., Okutoyi P., Mang'eni Ojiambo R., Haile D.W., Sigei T.K., Zippenfennig C., Milani T.L., Lieberman D.E. Foot callus thickness does not trade off protection for tactile sensitivity during walking. Nature. 2019;571(7764):261–264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article.