Abstract

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected intimate relationships? The existing literature is mixed on the effect of major external stressors on couple relationships, and little is known about the early experience of crises. The current study used 654 individuals involved in a relationship who provided data immediately before the onset of the pandemic (December, 2019) and twice during the early stages of the pandemic (March and April, 2020). Results indicate that relationship satisfaction and causal attributions did not change over time, but responsibility attributions decreased on average. Changes in relationship outcomes were not moderated by demographic characteristics or negative repercussions of the pandemic. There were small moderation effects of relationship coping and conflict during the pandemic, revealing that satisfaction increased and maladaptive attributions decreased in couples with more positive functioning, and satisfaction decreased and maladaptive attributions increased in couples with lower functioning.

Keywords: coronavirus pandemic, couples, COVID-19, interpersonal relationships, relationship quality

Major external stressors such as natural disasters or pandemics require individuals to immediately mobilize a response and tax the community-wide social-support resources that individuals typically turn to in times of stress. Accordingly, individuals rely heavily on the people closest to them for support in navigating these crises (e.g., Bonanno et al., 2010). However, reliance on intimate partners has been further heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals across the world were isolated at home with their families for weeks: Adults worked from home or were laid off, children were out of school, and physical contact with people outside of one’s household was discouraged or banned, raising questions about the impact of the pandemic on intimate relationships.

Existing research on the effect of major external stressors on couple relationships has relied on couples recruited and studied after experiencing a crisis and has yielded contradictory conclusions about whether the effects are positive or negative (e.g., Fredman et al., 2010; Harville et al., 2011; Lowe et al., 2012; Whisman, 2014). Though these studies provide limited ability to examine changes in relationship outcomes, they suggest that crises may have variable rather than uniform effects on relationships. Specifically, outcomes may differ along three key dimensions: demographic characteristics of the partners and relationships, such as their socioeconomic status or the length of the relationship; negative repercussions experienced during the stressor, such as financial strain or disruption of daily life; and relationship processes during the stressor, such as relationship conflict or positive coping.

Proper testing of the effects of a crisis on couples requires multiple waves of data on relationship functioning collected shortly before and shortly after the onset of the stressor (Bonanno et al., 2010). In the current study, I aimed to fill this critical gap by examining changes in couple relationships in the United States from several months before the COVID-19 pandemic to its initial stages. The degree to which relationship satisfaction and attributions changed on average over this period, as well as the extent to which the rate of change was moderated by demographic characteristics, experiences during the pandemic, and relationship processes, were tested.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited at Time 1 using the online research platform Prolific (www.prolific.co) from December 7 to December 9, 2019. All registered participants on Prolific who met the eligibility criteria (currently in a relationship, engaged, or married; residing in the United States; and age 18 years or more) were invited to take part in the study. The sample size was set at 1,200 because of availability of funding. A quota was placed that required 50% of participants to have a household income of $50,000 or less to ensure representation across a broad range of socioeconomic status. Participants took 15 min on average to complete the survey and were paid $2.50. The study was approved by the University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board.

Statement of Relevance.

The COVID-19 pandemic has called on couples to spend extended amounts of time together and rely primarily on each other for support during a major stressor that has upended nearly every aspect of daily life. In this study, individuals involved in a relationship were assessed before the start of the pandemic and again two times during the early stages of the pandemic to determine how their relationship changed. Overall, the results of this large national study indicate that, on average, people’s satisfaction with their relationship did not change, but they did become more forgiving and less blaming of their partner’s negative behaviors by attributing them less to their partner’s internal characteristics. These results were true irrespective of multiple characteristics, including demographics of the partners, preexisting characteristics of the relationship, and negative experiences resulting from the pandemic, but did vary on the basis of couple functioning during the pandemic.

All Time 1 participants were invited via a message to their Prolific account to participate in an unplanned follow-up that ran from March 26 to March 28, 2020 (Time 2). Of the 1,200 participants at Time 1, 825 participated at Time 2 (71%). Of these, 796 could be linked with their Time 1 data; the others could not be linked because they provided incomplete or incorrect ID numbers at either time point. Of the 796 participants with data at both time points, 14 participants indicated in response to a screening question that they were no longer in the same relationship (five were with a new partner, and nine were single). This left a sample of 782 participants at Time 2, who were invited 1 month later to participate at Time 3, which occurred from April 26 to April 29, 2020. Of the 782 eligible participants, 664 participated at Time 3, for a response rate of 85%. Of the 664, 10 participants indicated in response to a screening question that they were no longer in the same relationship (two were with a new partner, and eight were single), leaving a final analytic sample of 654. Both follow-ups took 10 min on average to complete, and participants were paid $2.00.

As context for the extent of the pandemic during data collection, note that the first case of COVID-19 in the United States was reported on January 22, 2020 (Harcourt et al., 2020), and at Time 2 data collection, the United States had the largest number of reported cases of COVID-19 in the world (81,321; McNeil, 2020). At Time 3 data collection, the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States had risen to more than 1 million, and COVID-19 deaths in the United States had surpassed the death toll of the Vietnam War (58,365; Welna, 2020). At Time 2 and Time 3, schools across the country had closed, and all states had issued orders limiting gatherings of individuals (National Governors Association, 2020).

Participants were 60% female, 38.5% male, and 1.5% other gender (including nonbinary and transgender) and primarily involved in different-sex relationships (92%). Forty-one percent of participants had children under the age of 18 living with them at Time 2 and Time 3; participants had 1.79 children on average (SD = 0.84), and the average age of the youngest child was 6.5 years (SD = 4.9). Participants were primarily White (82%); 5% were Black or African American, 5% were Hispanic/Latino, 4% were Asian/Asian American, 3% were mixed race, and less than 1% each were American Indian/Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and “other.”

Median household income was $50,000 to $59,999; 10% of households made less than $20,000 annually, 23% of households made $20,000 to $40,000, 20% of households made $40,000 to $60,000, 15% of households made $60,000 to $80,000, 12% of households made $80,000 to 100,000, and 20% of households made more than $100,000 at Time 1. Nine percent of participants had a high school degree or less, 30% had some college or an associate’s degree, 36% had a bachelor’s degree, and 25% had a graduate degree. At Time 2, 28% of participants were employed and still working at their workplace, 35% were employed but working from home because of the coronavirus, 22% were unemployed prior to the pandemic, 12% were unemployed because of the pandemic, and 3% were students. At Time 3, the employment status of all individuals remained the same, with the exception of 3% of individuals who changed from working at their workplace to working from home.

At Time 1, relationships averaged 13 years in duration (SD = 11 years); 64% percent of participants were married, 5% were engaged, and 31% were in dating relationships. At Time 2 and Time 3, 89% of couples were living together, 9% were not living together, and 2% did not normally live together but were living together because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Participants who did not participate in the Time 2 and Time 3 follow-ups did not significantly differ from those who participated in the baseline assessment on Time 1 relationship satisfaction, Time 1 responsibility and causal attributions, gender, race/ethnicity, and education (all ps > .10). Nonrespondents did significantly differ on household income, age, relationship length, and marital status (all ps < .001); respondents were approximately 5 years older, had been in the relationship approximately 4 years longer, had higher household income, and were more likely to be married.

Measures

Outcome variables

Relationship satisfaction

Global sentiment toward the relationship was measured at all time points with the four-item version of the Couples Satisfaction Index (Funk & Rogge, 2007). The items assess global satisfaction (e.g., “I have a warm and comfortable relationship with my partner”) and are rated on a 6-point scale (with the exception of one item that is rated on a 7-point scale); higher scores indicate higher levels of satisfaction. The four items were summed to form the scale score at each time point; the possible range was 0 to 25, and a total score less than 13.5 reflected relationship distress. Cronbach’s α was greater than .94 at all time points.

Relationship attributions

Attributions that individuals make for their partner’s behavior were assessed at all time points using the Relationship Attributions Measure (Fincham & Bradbury, 1992). Participants were presented with two negative events that are likely to occur in all intimate relationships (“Your partner criticizes something you say” and “Your partner does not pay attention to what you are saying”). For each event, participants were asked to rate their agreement with each of six response options on 7-point scales (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = neutral, and 7 = strongly agree). There are two subscales. The causal-attribution subscale examines the perceived locus, globality, and stability of the cause of the negative partner behavior (i.e., “The reason my partner criticized me is not likely to change”). The responsibility-attribution subscale captures the extent to which participants consider their partners’ behaviors as intentional, selfishly motivated, and blameworthy (i.e., “My partner criticized me on purpose rather than unintentionally”). A composite score is computed for both subscales by averaging the items in that subscale; the possible range is 1 to 7. Higher scores indicate more maladaptive attributions. At all time points, Cronbach’s α was greater than .74 for causal attributions and greater than .82 for responsibility attributions.

Moderator variables

Household income

At Time 1, participants were asked, “What is your total household income per year, including all earners in your household (after tax) in USD?” and given 13 response options ranging from “less than $10,000” to “more than $150,000.”

Education

At Time 1, participants were asked, “What is the highest level of school you have completed or the highest degree you have received?” and given response options of “less than high school degree,” “high school degree or equivalent (e.g., GED),” “some college but no degree,” “associate degree,” “bachelor’s degree,” and “graduate degree.”

Relationship length

At Time 1, participants were asked, “How long have you been in your current romantic relationship (For example: 2 years and 3 months)?” and they provided values for years and months in open-ended numeric response boxes.

Relationship status

At all time points, participants were asked, “What is your relationship status?” and given the response options “single,” “in a relationship,” “engaged,” and “married.” Individuals who selected “single” were removed from analyses as detailed above.

Cohabitation

At Time 2, participants were asked, “Are you currently living with your partner?” and were given the response options “yes,” “no,” and “we don’t usually live together, but have been staying together during the pandemic.”

Children in home

At Time 2, participants were asked, “Do you currently have children under the age of 18 who live with you?” The response options were “yes” and “no.”

Negative experiences of pandemic

Negative experiences that participants had as a result of the pandemic were assessed at Time 2 and Time 3 with a 16-item index of yes/no questions. Sample items included “had a decrease in your salary or wages” and “had to cancel major plans like a planned trip or vacation.” Participants were coded as having experienced each event if they responded “yes” at either time point; the 16 items were then summed to form the index. The full list of items and their frequencies are provided in Table S1 in the Supplemental Material available online.

Stress level from pandemic

At Time 2 and Time 3, participants were asked,

Taking everything into consideration, how stressful overall would you say your experience with the coronavirus pandemic has been on a scale of 0-10, where 0 means not at all stressful and 10 means the most stressful thing you can imagine? You can use any number between 0 – 10.

Final scores for each participant were calculated by averaging their scores at Time 2 and Time 3. Scores at Time 2 and Time 3 were positively correlated, r(641) = .68, p < .001.

Relationship coping

This construct was assessed at Time 2 and Time 3 with a six-item scale. At Time 2, the questions were prefaced with the statement, “This section asks questions about how you and your partner have been doing since the coronavirus pandemic started. Throughout the last few weeks, since the pandemic made it to the U.S. . . .” At Time 3, the questions were prefaced with the statement, “This section asks questions about how you and your partner have been doing over the past month. Over the past month . . .” Participants were then asked questions such as, “How well did you think you and your spouse worked together as a team?” “How often have the two of you helped each other relax with pleasant activities?” and “How often have you felt that household chores/tasks have been shared fairly between you and your partner?” All items were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1, very rarely, to 5, very often. The six items were averaged at each time point to form Time 2 and Time 3 scores, which were then averaged to form the final score. Cronbach’s α was .88 and .87, respectively. Scores at Time 2 and Time 3 were positively correlated, r(652) = .74, p < .001.

Relationship conflict

This construct was assessed at Time 2 and Time 3 with a two-item scale. At Time 2, the questions were prefaced with the statement, “This section asks questions about how you and your partner have been doing since the coronavirus pandemic started. Throughout the last few weeks, since the pandemic made it to the U.S. . . .” At Time 3, the questions were prefaced with the statement, “This section asks questions about how you and your partner have been doing over the past month. Over the past month . . .” Participants were then asked, “How often have you become irritated or angry at your partner?” and “How often have you argued with your partner?” Both items were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1, very rarely, to 5, very often. The two items were averaged at each time point to form Time 2 and Time 3 scores, which were then averaged to form the final score. Cronbach’s α was .84 and .83, respectively. Scores at Time 2 and Time 3 were positively correlated, r(652) = .67, p < .001.

Analytic plan

Analyses were conducted using multilevel modeling in Stata/IC (Version 14.2; StataCorp, 2015) to model the repeated measures nested within each participant. A series of models was estimated for each of the three outcome variables (relationship satisfaction, causal attributions, and responsibility attributions) to first determine whether a quadratic model or a linear model was a better fit to the data. Time was coded in weeks (Time 1 = 0, Time 2 = 16, and Time 3 = 20). For all three outcome variables, the quadratic time coefficient was nonsignificant (all ps > .25), indicating that the time trend was not curvilinear. Thus, a linear growth model was implemented to estimate the average degree of change in each construct over time. Random effects were examined to determine whether there was significant variability in the slope terms to support testing of moderators. Once significant variability in slopes was established, the 10 moderator variables were then examined individually. The Holm-Bonferroni correction procedure (Holm, 1979) was applied to the 10 tests of moderation within each of the three outcome variables to adjust the family-wise error rate for multiple tests. When significant moderation was indicated, simple slopes were analyzed at the mean and 1 standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderator variable.

Results

Descriptive statistics

At Time 1, there was a broad range of relationship functioning, as expected from a large, socioeconomically diverse community sample of couples across relationship stages. Participants’ relationship satisfaction was 15.48 on average (SD = 4.56), two points above the distress cutoff score of 13.5; causal attributions were 4.29 (SD = 1.06); and responsibility attributions were 3.72 (SD = 1.20).

At Time 2 and Time 3, participants had experienced a moderate level of negative experiences from the pandemic (M = 6.48, SD = 2.56, range = 0–15 out of 16 possible). The three most frequently endorsed items were “been worried about the health of members of your family” (91%), “felt isolated from other people” (77%), and “had difficulty obtaining the foods you usually eat” (68%). Notably, 41% of participants reported a decrease in their salary or wages, 22% reported not having enough food to eat, and 15% had lost their job. Participants also reported a broad range of stress levels because of the pandemic (M = 5.74, SD = 2.04, range = 0–10 out of 10 possible).

Autocorrelations (rs) between outcome variables at the three time points ranged from .58 to .85. Intercorrelations (rs) between the outcome variables were all significant and in the expected directions, ranging from |.40| to |.67|. A full correlation matrix of the nine outcome variables is given in Table S2 in the Supplemental Material.

Changes in relationship functioning over time

On average, relationship satisfaction and causal attributions did not significantly change over time (slope = −0.008, p = .171, 95% confidence interval, or CI = [−0.019, 0.003], r = −.05; slope = 0.001, p = .680, 95% CI = [−0.003, 0.004], r = .02, respectively). Responsibility attributions significantly decreased on average (slope = −0.010, p < .001, 95% CI = [−0.015, −0.006], r = −.20). For all three outcomes, there was significant variance in the slope terms (relationship satisfaction: random effect = 0.006, 95% CI = [0.004, 0.009]; causal attributions: random effect = 0.001, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.001]; responsibility attributions: random effect = 0.001, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.001]), indicating that there was significant variability in the degree of change over time across the sample and supporting the examination of potential moderating effects to better understand this variability.

Moderators of change in relationship functioning

There was an identical pattern of results for the three outcome variables (see Table 1 for test statistics). Demographic variables—income, education, relationship status, cohabitation status, relationship length, and the presence of children in the home—did not moderate slopes in relationship satisfaction, causal attributions, or responsibility attributions. Similarly, the index of negative experiences of the pandemic and stress level from the pandemic did not moderate change in the outcome variables. However, changes in relationship satisfaction, causal attributions, and responsibility attributions were significantly moderated by levels of relationship coping and relationship conflict; these moderation effects were small to medium in magnitude (rs = |.12| to |.27|).

Table 1.

Results of Multilevel Models Testing Moderators of Changes in Relationship Satisfaction and Attributions

| Variable | Relationship satisfaction | Causal attributions | Responsibility attributions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator × Time Coefficient | r | 95% CI | Moderator × Time Coefficient | r | 95% CI | Moderator × Time Coefficient | r | 95% CI | |

| Household income | 0.01 | .02 | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.01 | −.03 | [0.00, 0.01] | −0.01 | −.01 | [−0.01, 0.00] |

| Education | |||||||||

| High school | 0.03 | .01 | [−0.14, 0.19] | 0.02 | .03 | [−0.04, 0.08] | 0.01 | −.01 | [−0.07, 0.05] |

| Some college | 0.03 | .01 | [−0.13, 0.19] | 0.03 | .03 | [−0.03, 0.08] | −0.01 | .01 | [−0.05, 0.07] |

| Associate’s degree | 0.01 | .00 | [−0.16, 0.18] | 0.03 | .03 | [−0.03, 0.08] | 0.01 | .00 | [−0.06, 0.06] |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.01 | .01 | [−0.15, 0.18] | 0.02 | .03 | [−0.04, 0.08] | 0.00 | .01 | [−0.05, 0.07] |

| Graduate degree | 0.03 | .01 | [−0.13, 0.19] | 0.02 | .03 | [−0.03, 0.08] | 0.01 | .01 | [−0.05, 0.07] |

| Relationship status | |||||||||

| Engaged | 0.01 | .00 | [−0.05, 0.05] | 0.01 | .01 | [−0.07, 0.02] | 0.01 | −.02 | [−0.02, 0.01] |

| Married | 0.01 | .03 | [−0.02, 0.03] | 0.01 | .01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.01 | −.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] |

| Cohabitation | |||||||||

| Not cohabiting | 0.01 | .00 | [−0.04, 0.04] | 0.01 | .01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.01 | .02 | [−0.01, 0.02] |

| Cohabiting because of the pandemic | 0.02 | .02 | [−0.06, 0.09] | −0.03* | −.08 | [−0.06, 0.00] | 0.01 | .00 | [−0.03, 0.03] |

| Relationship length | 0.01 | .06 | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.01* | .09 | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.01 | .01 | [0.00, 0.01] |

| Children in home | 0.01 | −.01 | [−0.02, 0.02] | 0.01* | .08 | [0.00, 0.02] | 0.01 | .01 | [−0.01, 0.01] |

| Negative experiences of pandemic | −0.01* | −.10 | [−0.01, 0.00] | 0.01* | −.09 | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.01 | −.06 | [0.00, 0.01] |

| Stress level from pandemic | 0.01 | −.03 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.01* | −.09 | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.01** | −.11 | [0.00, 0.01] |

| Relationship coping | 0.05*** | .27 | [0.03, 0.06] | −0.01*** | −.20 | [−0.02, −0.01] | −0.01*** | −.21 | [−0.02, −0.01] |

| Relationship conflict | −0.03*** | −.17 | [−0.04, −0.02] | 0.01*** | .14 | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.01** | .12 | [0.01, 0.01] |

Note: N = 654. Coefficients are unstandardized. Ten moderator variables were tested for each of the three dependent variables. Education, relationship status, and cohabitation were tested as categorical variables with “less than high school degree,” “dating,” and “cohabiting” used as the respective reference groups. Coefficients in boldface remained significant after a Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple tests was applied to the coefficients within each dependent variable. Effect-size r is equal to Z/√N. CI = confidence interval.

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

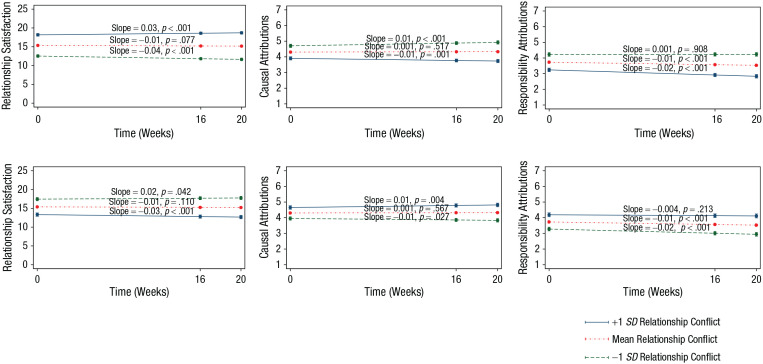

Simple slopes (shown in Fig. 1) indicated that among individuals with higher levels of coping, relationship satisfaction increased and causal and responsibility attributions decreased, whereas among individuals with lower levels of coping, relationship satisfaction decreased, causal attributions increased, and responsibility attributions remained stable. In practical terms, among individuals who were 1 standard deviation above the sample mean on relationship coping, relationship satisfaction increased from a mean score of 18.17 to 18.77 (on a 26-point scale), causal attributions decreased from a mean score of 3.91 to 3.71 (on a 7-point scale), and responsibility attributions decreased from 3.24 to 2.84 (on a 7-point scale) over the 20 weeks. Among individuals who were 1 standard deviation below the sample mean on relationship coping, relationship satisfaction decreased from 12.53 to 11.73 (on a 26-point scale), causal attributions increased from a score of 4.70 to 4.90 (on a 7-point scale), and responsibility attributions remained stable over the 20 weeks. Notably, these participants entered the study with a relationship-satisfaction score that was already below the distress cutoff of 13.5 and exhibited further declines over the early months of the pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Changes in relationship satisfaction (left column), causal attributions (center column), and relationship attributions (right column) across the three time points of the study, separately for individuals high, low, and at the mean of relationship coping (top row) and relationship conflict (bottom row). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Conversely, among individuals with lower levels of conflict, relationship satisfaction increased and causal and responsibility attributions decreased, whereas among individuals with higher levels of conflict, relationship satisfaction decreased, causal attributions increased, and responsibility attributions remained stable. In practical terms, among individuals who were 1 standard deviation below the sample mean on relationship conflict, relationship satisfaction increased from a mean score of 17.44 to 17.84 (on a 26-point scale), causal attributions decreased from 3.95 to 3.75 (on a 7-point scale), and responsibility attributions decreased from 3.28 to 2.88 (on a 7-point scale) over the 20 weeks. Among individuals who were 1 standard deviation above the sample mean on relationship conflict, relationship satisfaction decreased from a score of 13.33 to 12.73 (on a 26-point scale), causal attributions increased from a score of 4.65 to 4.85 (on a 7-point scale), and responsibility attributions remained stable over the 20 weeks. As with coping, individuals whose conflict scores were 1 standard deviation above the sample mean entered the study with a relationship-satisfaction score that was already below the distress cutoff of 13.5 and exhibited further declines over the early months of the pandemic.

Discussion

Bowlby (1973) observed that family members stay in close proximity for days or weeks after a disaster because the affiliation is comforting during a crisis. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, close proximity to family members was not a choice because of government orders to socially isolate, raising questions about how relationships fared during this time. Overall, the results of this large, well-powered national study indicate that the experience of the early weeks of a global pandemic did not erode relationship satisfaction on average, and people even became more forgiving and less blaming of their partner’s negative behaviors by attributing them less to their partner’s internal characteristics. The high salience of the pandemic as a stressor likely increased people’s ability to see it as a potential driver for their partner’s behaviors, compared with smaller daily stressors that are often overlooked as a source of partners’ behavior (Tesser & Beach, 1998). These results were true irrespective of multiple characteristics, including demographics of the partners, preexisting characteristics of the relationship, and negative experiences resulting from the pandemic. However, there were small moderation effects based on relationship behaviors during the early months of the pandemic. Individuals who engaged in positive coping efforts and were able to avoid conflict with their partner during this time experienced a small increase in relationship satisfaction and adaptive attributions, modestly enhancing already high functioning, whereas individuals who reported poor coping and high conflict experienced a small decrease in relationship satisfaction and adaptive attributions, modestly decreasing already distressed functioning.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, more research is needed to understand its impact on couple relationships, including whether the short-term changes in attributions observed here will be maintained and whether changes in relationship satisfaction will arise as couples deal with the pandemic’s increasing toll. Additionally, the extent to which the pandemic will have broader effects on couples’ decisions to marry, have a child, or divorce (e.g., Cohan & Cole, 2002) remains to be seen. Finally, for couples who are experiencing difficulties in their relationships during this stressful period, the availability of evidence-based online relationship interventions (e.g., Doss et al., 2020) has become more important than ever in overcoming barriers to treatment. Future research should examine whether uptake of these interventions increased during this time and whether couples present for treatment with different levels of distress or qualitatively different problems than in the past (e.g., Roddy et al., 2019).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Williamson_Supplemental_Material_rev for Early Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Relationship Satisfaction and Attributions by Hannah C. Williamson in Psychological Science

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Justin Lavner for helpful comments while preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Hannah C. Williamson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4816-3621

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4816-3621

Supplemental Material: Additional supporting information can be found at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/0956797620972688

Transparency

Action Editor: Lisa Diamond

Editor: Patricia J. Bauer

Author Contributions

H. C. Williamson is the sole author of this article and is responsible for its content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: Funding for this study was provided by the Russell Sage Foundation (1904-14297); the College of Natural Sciences at The University of Texas at Austin; and Grant P2CHD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Open Practices: Data and materials for this study have not been made publicly available, and the design and analysis plans were not preregistered.

References

- Bonanno G. A., Brewin C. R., Kaniasty K., Greca A. M. L. (2010). Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 11(1), 1–49. 10.1177/1529100610387086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Volume 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cohan C. L., Cole S. W. (2002). Life course transitions and natural disaster: Marriage, birth, and divorce following Hurricane Hugo. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(1), 14–25. 10.1037//0893-3200.16.1.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss B. D., Knopp K., Roddy M. K., Rothman K., Hatch S. G., Rhoades G. K. (2020). Online programs improve relationship functioning for distressed low-income couples: Results from a nationwide randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(4), 283–294. 10.1037/ccp0000479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham F. D., Bradbury T. N. (1992). Assessing attributions in marriage: The relationship attribution measure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(3), 457–468. 10.1037/0022-3514.62.3.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman S. J., Monson C. M., Schumm J. A., Adair K. C., Taft C. T., Resick P. A. (2010). Associations among disaster exposure, intimate relationship adjustment, and PTSD symptoms: Can disaster exposure enhance a relationship? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(4), 446–451. 10.1002/jts.20555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk J. L., Rogge R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt J., Tamin A., Lu X., Kamili S., Sakthivel S., Murray J., Queen K., Tao Y., Paden C., Zhang J., Li Y., Uehara A., Wang H., Goldsmith C., Bullock H., Wang L., Whitaker B., Lynch B., Gautam R., Schindewolf C., . . . Thornburg N. (2020). Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 from patient with coronavirus disease, United States. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 26(6), 1266–1273. 10.3201/eid2606.200516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville E. W., Taylor C. A., Tesfai H., Xu X., Buekens P. (2011). Experience of Hurricane Katrina and reported intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(4), 833–845. 10.1177/0886260510365861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6(2), 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe S. R., Rhodes J. E., Scoglio A. A. J. (2012). Changes in marital and partner relationships in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: An analysis with low-income women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36(3), 286–300. 10.1177/0361684311434307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil D. G. (2020, March 26). The U.S. now leads the world in confirmed coronavirus cases. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/26/health/usa-coronavirus-cases.html

- National Governors Association. (2020). Coronavirus state actions chart. April 14, 2020. https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CoronavirusStateActionsChart_14April2020.pdf

- Roddy M. K., Rothman K., Cicila L. N., Doss B. D. (2019). Why do couples seek relationship help online? Description and comparison to in-person interventions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(3), 369–379. 10.1111/jmft.12329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata statistical software: Version 14 [Computer software]. College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Tesser A., Beach S. R. H. (1998). Life events, relationship quality, and depression: An investigation of judgment discontinuity in vivo. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 36–52. 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welna D. (2020, April 28). Coronavirus has now killed more Americans than Vietnam War. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/28/846701304/pandemic-death-toll-in-u-s-now-exceeds-vietnam-wars-u-s-fatalities

- Whisman M. A. (2014). Dyadic perspectives on trauma and marital quality. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(3), 207–215. 10.1037/a0036143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Williamson_Supplemental_Material_rev for Early Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Relationship Satisfaction and Attributions by Hannah C. Williamson in Psychological Science