Abstract

Background:

Opioids are essential medicines. Despite international and national laws permitting availability, opioid access remains inadequate, particularly in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia.

Aim:

To review evidence of perceptions and experiences of regulatory enablers and barriers to opioid access in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia.

Design:

Systematic review of post-2000 research according to PRISMA guidelines. Data were subjected to critical interpretive synthesis. International, national and sub-national barriers were organised developing a conceptual framework of opioid availability.

Data sources:

PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library. CINAHL, Complete and ASSIA from 2000 until 20th May 2019.

Results:

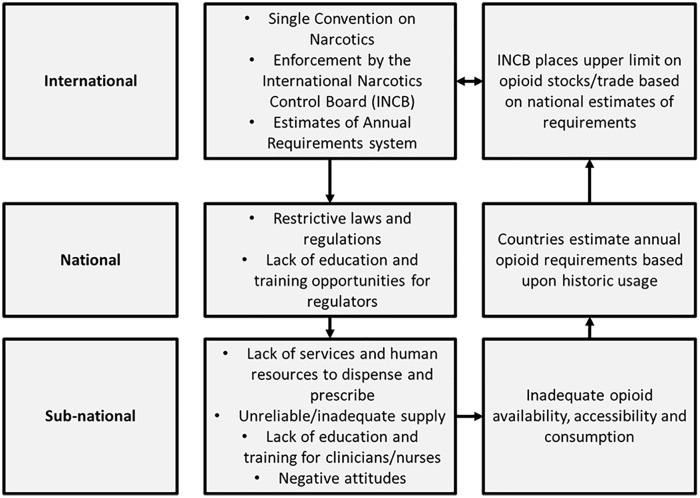

21/14097 studies included: quantitative n = 15, qualitative n = 3 and mixed-methods n = 3. Four barrier/enabler themes were developed: Legal, regulatory, socio-political; lack of laws explicitly enabling opioid access, restrictive international controls and clinician prescribing concerns. Opioid availability; limited availability, poor policymaker and clinician education regarding opioid benefits, poor continuity of supply. Opioid Accessibility; medicine costs, distance to prescribing centres. Prescribing; extensive bureaucratic barriers, lack of human resources for prescribing. We present a novel framework of a self-perpetuating model of inadequate opioid provision. The Single Convention on Narcotics provides the context of restrictive laws and negative attitudes amongst policymakers. A consequent lack of prescribers and clinicians’ negative attitudes at sub-national levels, results in inadequate access to and use of opioids. Data of inadequate consumption informs annual requirement estimates used by the International Narcotics Control Board to determine future opioid availability.

Conclusions:

Regulatory and socio-political actions unintentionally limit opioid access. International and national laws explicitly enabling opioid access are required, to assuage concerns, promote training and appropriate prescribing.

Keywords: Opioid analgesics, drug legislation, controlled substances, pain management, palliative care

What is already known about the topic?

Access to opioids is inadequate across South, Southeast, East and Central Asia.

Most existing literature on unmet need for opioids focusses upon estimates of need in a palliative care context and attitudes of clinicians towards opioids.

What this paper adds?

We show how barriers at international level raise further barriers at national and sub-national levels which limit accessibility of opioids, even when they are technically available.

The international opioid regulatory framework is revealed as a self-perpetuating model, where restrictive forces at international and national level reinforce negative attitudes and fears of prescribing opioids at sub-national level.

Data based upon inadequate levels of opioid consumption is then used to estimate opioid requirements for the following year, resulting in a cycle of inadequate opioid availability.

Implications for practice and policy

Global policies must focus upon enabling access to opioids based upon evidence-based assessments of population-level need for opioids.

Nations should implement legislation affirming governmental responsibility for ensuring access to opioids, to create a positive regulatory context and assuage concerns of clinicians relating to legal redress for prescribing opioids.

Improved education and training opportunities regarding the benefits of opioids and safe prescribing are essential to challenge negative perceptions of opioids and increase human resources for prescribing and clinical care.

Introduction

Globally, access to opioid treatments is inadequate.1 It is estimated that currently 61 million people who need opioids suffer due to lack of access, with the greatest unmet need in low and middle-income countries in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia.2

Therapeutic opioids are a key aspect of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) widely-used three-step cancer pain ladder.3 Opioids also are indicated for moderate to severe pain in common clinical scenarios such as childbirth,4 acute musculoskeletal pain,5 trauma,6 peri-operative care7 and, in low doses, for severe chronic breathlessness.8 Without appropriate access to opioids, physical and associated psychological suffering is severe. Untreated pain also has socio-economic consequences for families, for example, risk of poverty due to inability to work.9 Suffering incurred by those with unmanaged pain has led to calls for access to pain relief to be a basic human right.10

Most therapeutic opioids are controlled substances, regulated under international law. Production and distribution of controlled substances (e.g. Morphine) is subject to the terms of the Single Convention on Narcotics and subsequent international drug laws.11 Weaker opioids (e.g. Tramadol) recommended for Step 2 on the WHO pain ladder, are not internationally controlled substances and are regulated differentially at the national level.

The Single Convention on Narcotics has been in force since 1960 to prohibit production and supply of illegal narcotics and ensure access to opioids (narcotic formulations) for medical purposes. Nation states enact drug laws to implement the terms of the Convention. Yet, barriers to access to opioids medicines exist at international, national and sub-national levels.12 The Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief reports that “In most [low and middle-income countries], unduly restrictive laws and regulations hinder the availability of and access to opioids for people with legitimate needs.”2

In the context of laws and regulations which technically permit opioid availability, little is known regarding how laws and regulations interact between levels, to practically enable or limit access to opioids for patients with legitimate medical need. Of concern, the President of the International Narcotics Control Board, the international organisation charged with overseeing the implementation of the Single Convention worldwide, recently questioned the current utility of the Single Convention, first drawn up half a century ago:

“I think it is an appropriate time to look at whether those are still fit for purpose, or whether we need new alternative instruments and alternative approaches to deal with these problems [Cornelis P. de Joncheere, 2020].”13

As the most populous world region, most unmet need for opioids is in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia. We conducted a mixed-methods systematic review of the academic literature to explore perceptions and experiences of regulatory barriers and enablers to opioid access in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia in the context of international and national drug regulations.

Aim

We aimed to review and synthesise published evidence of perceptions and experiences of regulatory enablers and barriers to opioid access in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia.

Design

We conducted a systematic review with critical interpretive synthesis of post-2000 research relevant to our aim with reference to 2009 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare.14 The review was reported in accordance with recommendations in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines.15 Data were subjected to critical interpretive synthesis. International, national and sub-national barriers were organised to develop a conceptual framework of opioid availability. Our approach was selected as an appropriate method of identifying all relevant literature and synthesising qualitative and quantitative findings in to singular thematic categories.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

We developed a pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria] to identify articles relevant to our research aims (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| 1. Literature pertaining to human subjects 2. Peer reviewed publications published from 2000-present 3. Qualitative and quantitative primary research papers 4. Literature reporting use of opioids for pain management 5. Literature reporting perceptions and experiences of laws and regulations governing access to opioids in terms of one or more of the following: • Access to opioid therapeutics • Barriers to opioid availability and accessibility • Facilitators to opioid access 6. Literature fulfilling above criteria pertaining to one or more of the following: • Health system factors • Policy – international, national, regional or local • Legislation – international, national, regional or local • Models of care including availability, logistical organisation and delivery |

1. Conference abstracts, case studies, case reviews, reviews, systematic reviews, non-peer reviewed literature, grey Literature 2. Studies reporting data not pertaining to opioids for pain relief – such as those related to opioid dependence or withdrawal 3. Studies reporting data pertaining to individual clinical practice including patient characteristics, physician decision making and medication efficacy |

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted in two parts to identify articles ahead of applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The initial search was performed on 30th August 2017 on the following databases: PsycINFO, Medline and Embase via OVID, The Cochrane Library (including include Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials: CENTRAL and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: CDSR), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) Complete via EBSCOhost and ASSIA (Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts) via Proquest. A date restriction of published post-2000 was applied to ensure that findings were up-to-date and did not reflect historic and outdated issues. Search terms related to three main concepts which were combined with AND: Concept one included terms such as opioid OR opiate OR morphine, concept two included terms such as pain OR analgesi* OR palliat* and the third concept included terms such as access OR avail* OR prescrib*. The search terms for opioids included generic names and individual drug names. Search strategies for all database searches are available in online supplementary file 1. Results were downloaded into an EndNote library, duplicates were removed and references uploaded into the online Rayyan software (www.rayyan.com).

Originally, we planned to conduct a worldwide review of perceptions and experiences of laws and regulations governing access to opioids. However, during study selection after the initial search, it became apparent that the volume of relevant papers being identified, would not allow analysis with an appropriate level of detail and focus. South, Southeast, East and Central Asia was selected as the amended focus of the review due to several factors. First, a regional focus is consistent with how the INCB reports statistics related to consumption, implying a regional approach to international regulatory oversight.16 Secondly, South, Southeast, East and Central Asia is the world region with the greatest unmet need for therapeutic opioids and is known to face significant regulatory barriers to their availability.2 Third, narrowing our focus, allows for models of good or bad practice to be identified, which are likely to have contextual relevance within countries and across the region.17 Finally, a focus on Asia allows incorporation of data from low, middle and high income countries. We excluded papers focussed upon countries in the Middle East and Western Asia and the Caucasus, due to particular political challenges in the delivery of healthcare in these regions.

Following these changes during a period of reflection, an updated search was performed on 20th May 2019 by an experienced information specialist which repeated the initial search strategy for all databases but in addition, added in a fourth concept of South, Southeast, East and Central Asia as well as limiting the results to those published since the previous search. Search terms for Asia included the “exploded” indexed term for Asia for respective databases as well as a text word search for individual countries for example, China or India. Although countries in the Middle East were excluded from our analysis, we included the region in our search as the MeSH heading for the region includes Afghanistan as part of the Middle East, though it is widely considered to be part of Central Asia. Results from the second search were added to the original EndNote library to remove duplicates and overlapping references.

No language, publication type restrictions were applied to the search.

Study selection

Studies were included if they met our inclusion criteria and did not meet our exclusion criteria (Table 1). Following the described changes to our research aim and search strategy, included articles must be focussed on South, Southeast, East and Central Asia, or have extractable data relevant to these regions.

Two authors independently screened study titles and abstracts identified by the searches against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Full texts of studies were retrieved where necessary to assess eligibility. If a study was rejected at full text review, a reason for exclusion is reported. Disagreements were resolved through consensus, with the involvement of a third author. We included a further eligible study published outside of our search period which we only became aware of a further eligible study during background research for manuscript drafting published outside of our search period which we included.

Data extraction

Data extraction forms were developed to extract quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies. Two authors independently extracted data from each included paper regarding study aims, national setting, study design and key findings relevant to the aims of our review. Combined data extraction is presented in Supplementary File 2. Extracted data informed analysis and individually extracted studies were referred to at the conclusion of theme development and data synthesis, to ensure that analysis accurately reflected extracted data.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was undertaken using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), 2018 tool, which is appropriate for appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies.18 Appraisal was conducted in line with guidance for using the MMAT by two researchers; disagreements were resolved through discussions with a third researcher. The purpose of the MMAT is to gain an impression of overall methodological quality and it is discouraged to calculate a quality score for studies. The purpose of our appraisal was therefore not to develop individual scores for included studies, but to identify methodological issues that should be taken into consideration during interpretation.

Data analysis and synthesis

We conducted a critical interpretive synthesis of included studies, incorporating key processes recommended by Dixon et al.19 We refined our research question following initial searching, to focus specifically upon factors influencing opioid availability in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia, as the world region most likely to have challenges providing safe opioid access and availability to its population. Quantitative and qualitative data were extracted to a piloted extraction form in Microsoft Word v.16.0, 2016 by two researchers (JC, SGa). Data were then coded iteratively and organised in thematic areas (JC, SGa). Preliminary themes were then developed and reviewed, with further sub-themes were defined (JC, SGa, MJ). Data were synthesised within emergent themes using quantitative data with supporting qualitative data to develop analytic themes. A reflective analytical draft of results (JC) was drafted to produce a synthesised argument based upon findings extracted from included studies. This draft was reviewed by the study team and appropriate re-organisation of primary themes was undertaken, responsive to concerns and in the context of quality of included studies. As some data may be considered relevant to more than one theme, further minor modifications were made to developed themes during manuscript preparation in accordance with interpretive synthesis guidelines to use ongoing critical orientation.18

Following data synthesis, identified barriers were organised into international and sub-national levels to develop a conceptual framework of barriers to opioid availability in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia. We included a broad range of evidence to inform our emergent theory to ensure this was critically informed and plausible given the available evidence.

Results

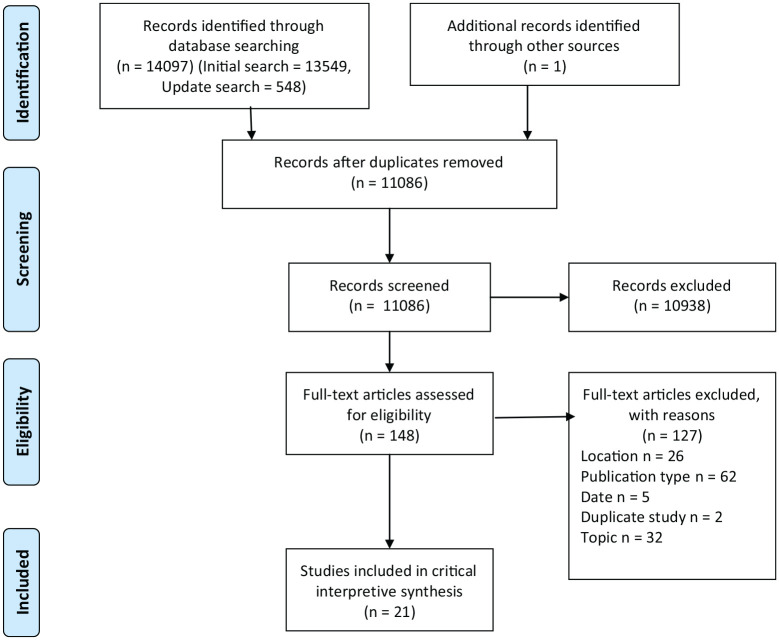

Over the two searches, 11,085 results were retrieved after deduplication, 10706 from the initial search [2017] and 379 from the more focussed update search [2019]) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection.PRISMA flow diagram.

We identified 11086 potentially relevant studies. After study selection, 21 studies met our inclusion criteria: quantitative (n = 15), qualitative (n = 3) and mixed-methods (n = 3). Most included were internationally focussed (n = 9), other studies came from India (n = 4), Thailand (n = 3), Bangladesh (n = 2), China (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1) and the Philippines (n = 1). Characteristics and key findings of included studies are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Included studies characteristics and key findings.

| Quantitative studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (s)/year of publication | Aims | Study design | Study population | Setting | Key findings | |

| 1 | Duthey et al.20 | To analyse the adequacy of consumption of opioid analgesics for countries and World Health Organization regions in 2010 as compared with 2006 | Adequacy of Consumption Measure using data for 2010 based on a method established by Seya et al. This method calculates the morbidity-corrected needs per capita for relevant strong opioid analgesics and the actual use for the top 20 Human Development Index countries. It determines the adequacy of the consumption for each country, World Health Organization region, and the world by comparing the actual consumption with the calculated need | Global macro datasets | Global (Asian data extracted) | • Study shows a global trend towards an increase in opioid adequacy in countries and world regions between 2006 and 2010 • Most of the increase in global consumption of opioids resulted from increases in high-income countries not in Asia • For World Health Organization Region Southeast Asia, three countries showed an increase in adequacy of consumption and four a decrease between 2006 and 2010 |

| 2 | Majeed et al.21 | (1) To identify and describe data for adequacy of the pain management in patients with advanced cancer; (2) to establish a relationship between analgesics prescribed and pain control; and (3) to examine the implementation of the WHO analgesic guidelines in these patients | Cross-sectional (survey) | Sample size: 136 patients with cancer-related pain ⩾5 on an 11 point Numerical Rating Scale for pain | Pakistan | • Study highlights the serious practice gaps in effective pain management in patients with advanced stage cancer in Pakistan • Identified evidence about failure to implement the WHO guidelines for cancer pain management in an overwhelming majority of the patients in this study leading to under-prescribing of opioids |

| 3 | Onishi et al.22 | To compare opioid prescribing patterns in the United States and Japan: primary care physicians’ attitudes and perceptions | Cross-sectional (survey) | Sample size: 461 Japanese clinicians and 198 from the United States | Japan (and United States) | • Overall, 24.1% of Japanese respondents reported that they would “never” or “seldom” use opioids for acute or chronic pain, compared with 1.0% of US physicians (p < .001) • US respondents were twice as likely as Japanese physicians to indicate that opioid treatment was a legal expectation (17.6% US vs 8.6% Japan; aOR, 2.03; p = .026) |

| 4 | De Lima et al.23 | To provide information on access to pain treatment, as measured by the availability and dispensed price of five opioids in 13 formulations, and the affordability of oral immediate-release (IR) Morphine | Cross-sectional (survey) | 30 pharmacists from 26 countries | Global (Asian data extracted) | • Identified affordability of opioids as a barrier, based upon the mean number of days’ wages required by the lowest-paid worker to purchase a 30 day treatment of morphine oral solid IR – 29.48 (Philippines) and 20.75 (India) • Found a significant positive correlation between a country’s gross national income and the availability of opioids |

| 5 | Cleary et al.24 | To describe opioid availability and accessibility for cancer patients in Asia | Cross-sectional (survey) | Representatives from 20 countries submitted reports on formulary availability and regulators barriers | Asia and the Middle East (Asian data extracted) | • Most included countries reported that opioids were only available in hospital pharmacies • Only in Afghanistan were pharmacists allowed to prescribe in emergency situations • In approximately half of included countries (11 of 20), medicines were provided to patients at no cost or <25% of the cost. Patients paid full cost of all medications in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Nepal and the Philippines |

| 6 | Srisawang et al.25 | To assess the knowledge and attitudes physicians and policy makers/regulators have regarding use of opioids for cancer pain management. Barriers to opioid availability also studied | Cross-sectional (survey) | Sample size: 266 (219 physicians + 47 policy makers/regulators) | Thailand | • Policymakers/regulators, perceived shortages or interruptions in opioid manufacture or distribution as the greatest barriers to opioid availability • Lack of education and training opportunities were the greatest barriers to prescribing amongst physicians • Lack of education/understanding about pain management identified amongst health policy makers and drug regulators |

| 7 | Gilson et al.26 | To examine government and health-care system influences on opioid availability for cancer pain and palliative care, as a means to identify implications for improving appropriate access to prescription opioids | A multivariate regression of 177 countries’ consumption of opioids (in milligrams/death from cancer and AIDS) contained country-level predictor variables related to public health, including Human Development Index, palliative care infrastructure, and health system resources and expenditures | NA | Global (Asian data extracted) | • Countries had greater opioid consumption when palliative care was more fully integrated into the country’s health-care infrastructure (p = 0.001), and when both consumption statistics and estimates were submitted to INCB consistently over the last 5 years (p = 0.004) • Extent of government spending positively predicted the aggregate consumption of opioids indicated for treating severe pain • The higher a country’s human development ranking, the greater its Total Morphine Equivalent consumption value (p < 0.0001) |

| 8 | Javier and Calimag27 | To find out if opioid usage has improved in the Philippines 20 years after the introduction of the WHO analgesic ladder | Cross-sectional (survey) | Sample size: 211 physicians | Philippines | • Identified very good awareness amongst clinicians of the WHO analgesic ladder (72%) • Majority of the respondents were aware of opioids being available in their hospitals (89.57%), 4.27% commented that opioids are not available, whilst 6.16% are not sure about opioid availability in their hospitals • Two-thirds of the respondents (60.19%) had a Dangerous Drug (S2 licence) • Amongst those who do not have the licence, many respondents (60.66%) attribute this to the fact that their hospitals do not provide them with the necessary S2 licence and yellow prescription form even when they are in government practice |

| 9 | Khan et al.28 | The objective of the study was to gather pertinent Bangladeshi information to assist health professionals, policy makers and the community in the development of programs to improve the care of patients with moderate to severe pain | Cross-sectional (survey) | Sample size: 1000 physicians with pain management responsibilities in 47 districts in Bangladesh. Response rate 58.3% | Bangladesh | • Sixty-seven percent of included physicians reported no regulatory investigation about their opioid prescribing practices, 10% knew someone who had been investigated and 23% did not know regarding the matter • Distribution of the total knowledge, attitude and perceived barrier of the study physicians in relation to the practice setting • The majority of the physicians showed inadequate knowledge regarding opioid analgesic prescription • Amongst responding physicians only 31% believe that legitimate prescription of narcotic pain-relieving drugs in cancer patients do not cause addiction |

| 10 | De Lima et al.29 | This study addressed retail prices and availability of potent opioids in the developing countries of Argentina, Colombia, India, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia, and compared this to similar data for the developed countries of Australia, Canada, Denmark, Italy, Japan, Spain, and the United States | Cross-sectional (survey) | Pain and Palliative Care specialists collected data on the retail cost of a 30 day supply of 15 different opioid preparations | 5 developing and 7 developed countries.– see “aims” (Asian data extracted) | • In US dollars, the median cost of opioids differed between developed and developing countries ($53 and $112, respectively) • The median costs of all opioid preparations as a percentage of GNP per capita per month were 36% for developing and 3% for developed nations • In developing countries, 23 of 45 (51%) of opioid dosage forms cost more than 30% of the monthly GNP per capita, versus only three of 76 (4%) in developed countries |

| 11 | Thongkhamcharoen et al.30 | To provide an up-to-date overview of the role of multidisciplinary teams in the regulation of opioids in Thai government hospitals | Cross-sectional (survey) | Questionnaire distributed to government hospitals in Thailand and all private hospitals in Bangkok. There were 975 hospitals, including 93 private hospitals in Bangkok and 882 government hospitals. (NB: it is not reported who completed the questionnaires) | Thailand | • Respondents mentioned that community hospitals did not have enough doctors for opioid prescribing • Need for doctors to sign a special form for every single patient visit • Majority of hospitals have no specific regulation of opioid amount per prescription |

| 12 | Yu et al.31 | To assess the current status of cancer pain management, and physicians’ attitudes in China towards cancer pain management | Cross-sectional (survey) | A survey of 427 physicians and 387 cancer pain patients from one Chinese general hospital | China | • 62.8% of clinicians had concerns about regulatory investigation for prescribing narcotics • 72.8% of clinicians felt medical school training with regard to cancer pain management was inadequate leading to a reluctance to prescribe opioids |

| 13 | Berterame et al.32 | To provide up-to-date worldwide, regional, and national data for changes in opioid analgesic use, and to analyse the relation of impediments to use of these medicines | Cross-sectional (survey) | 214 countries | Worldwide, regional, and national study (Asian data extracted) | • Study reports impediments to the availability of opioid analgesics in East and Southeast Asia as: “Absence of awareness or training in use of opioid drugs in members of the medical profession” 3 (33%), “Restricted financial resources” 5 (56%), “Issues in sourcing from industry or imports” 3 (33%), “Fear of diversion to illicit channels” 6 (67%), “Control measures applicable to international trade such as need for import or export authorisation” 1 (11%), “Fear of criminal prosecution or sanction” 3 (33%), and “Onerous regulatory framework for prescription of narcotic drugs for medical use” 1 (11%) |

| 14 | Vijayan et al.33 | To obtain a clearer picture of the current role and clinical use of Tramadol in Southeast Asia | Cross-sectional (survey) | Pain specialists from seven countries in the region were invited to participate in a survey of their individual use and experience of Tramadol | Southeast Asia | • Respondents from India, Indonesia and Pakistan also stated that there is limited or no availability of controlled opioid analgesics in their countries • Every one of the respondents considered tramadol to be either significant or highly significant in the treatment of moderate to severe non-cancer pain in their home country, specifically mentioning acute indications such as labour pain, postoperative and post-traumatic pain, and chronic indications such as low back pain and osteoarthritis • Respondents strongly agreed that tighter regulation would lead to a significant reduction in the medical availability of tramadol, especially in the outpatient setting • In total, 72% of responders (33 of 46 countries) expressed concern that the introduction of control measures would limit accessibility to tramadol and make doctors more reluctant to prescribe it |

| 15 | Singh et al.34 | To assess current knowledge, attitude, prescribing practices, and barriers perceived by the Indian medical practitioners in three tertiary care hospitals towards the use of opioid analgesics | Cross-sectional (survey) | Sample size: 308 medical practitioners at three tertiary hospitals in New Delhi | India | • Two-thirds of the participants (61.7%) reported that they had never received any formal training in pain management, whilst 38.5% of the participants had • Seventy-eight percent (78.6%) of the participants reported that they had never faced any unwanted attention from the authorities as a result of prescribing opioids • Those who felt that addiction potential was a barrier to prescribing opioid analgesics were not more likely to report that they have not received adequate training in pain management |

| Qualitative studies | ||||||

| Author (s)/year of publication | Aims | Study design | Study population | Setting | ||

| 16 | LeBaron et al.35 | To examine barriers to opioid availability and cancer pain management in India, with an emphasis on the experiences of nurses, who are often the front-line providers of palliative care | Ethnography | 59 oncology nurses affiliated with 37 South Indian Cancer Hospitals and 22 others who interacted closely with nurses | Cancer hospitals in South India | • Morphine is more available at study site than in most of India, but access is limited to patients seen by the palliative care service, and significant gaps in supply still occur • Systems to measure and improve pain outcomes are largely absent • Key barriers related to pain management include the role of nursing, opioid misperceptions, bureaucratic hurdles, and sociocultural/infrastructure challenges |

| 17 | Husain et al.36 | To determine whether national drug control laws ensure that opioid drugs are available for medical and scientific purposes, as intended by the 1972 Protocol amendment to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs | Policy analysis of a sample of national drug laws | Laws from 15 countries | India, Nepal, Philippines, Vietnam (Asia data extracted) | • No country in Asia had a drug control law that recognised that the medical use of opioid drugs continues to be indispensable for the relief of pain and suffering • Only in India and Vietnam, did laws in Asian countries specifically declare an intention to implement the Single Convention on Narcotics • No Asian country declared adequate provision of opioids |

| 18 | Dehghan et al.37 | To investigate the use of Morphine in advanced cancer in palliative care setting in Bangladesh, in order to inform clinical practice and fledgling service development | Single semi-structured qualitative interview study | 20 cancer patients, family members and palliative care specialists in two medical settings | Bangladesh | • Lack of availability of morphine was identified as the main barrier to pain control • Low awareness amongst clinicians of therapeutic benefits of opioids and concerns about addition/side-effects limit prescribing • Families encounter irregularity of supply, meaning that prescriptions are not fulfilled • High cost of opioids (fentanyl) limit access • Patients face logistical challenges in accessing centralised prescribing centres |

| Mixed methods studies | ||||||

| Author (s)/year of publication | Aims | Study design | Study population | Setting | ||

| 19 | McDermott et al.38 | To assess the current state of palliative care in India, mapping the existence of services state by state, and documenting the perspectives and experiences of those involved | A multimethod review and synthesis of published and grey literature findings, ethnographic field visits, interviews, with existing public health data | 87 interviews with key in-country experts and palliative care activist from 12 states | India | • Opioid accessibility is a constant problem for the providers of hospice and palliative care in India • Identified a range of barriers to morphine availability, including: stringent central government legislation, state government reluctance to implement/ignorance regarding simplified narcotics regulations, difficulties with some state bureaucracy, fears about morphine addiction amongst state officials, health professionals, patients and their families, pharmaceutical companies unwilling to produce morphine, products prohibitively expensive, few dispensing services, health professionals’ lack of experience of prescribing morphine, fear of side effects in patients, and little training/education about morphine provided to health professionals and the general public |

| 20 | Joranson et al.39 | To develop an initiative to improve availability and patient access to opioids for palliative care | Implementation research methods including developing cooperation with government and non-government organisations, identifying regulatory barriers to Morphine availability through analysis of national narcotics control policies according to the principle of “balance,” proposing changes in policy, developing workshops to support and implement policy change, and monitoring the effects on availability and patient access to Morphine | NA | India | • State narcotic rules, which varied from state to state, were complex, requiring that medical institutions obtain a number of licences to possess opioids such as morphine • Bureaucratic procedures can delay for months and even years the approval of all the necessary licences for obtaining morphine, because the excise officers in charge may not be familiar with the medical subject of pain relief, and are likely to have a view of narcotic drugs that is limited to concern about addiction. When the last of the licenses is finally issued, it is likely that one or more of the other licences have expired • Simplified narcotic regulations in Kerala improve opioid availability |

| 21 | Kitreerawutiwong et al.40 | To develop a community-based palliative care model in a district health system based on the form of action and evaluation | Three-step action research | Stakeholders were patients and families undergoing palliative care health professionals, and social workers in the district | Thailand | • District Health Service does not prescribe morphine to be used in the community/at home due to a lack of regulatory guidelines • Lack of trained morphine prescribers, in context of concerns regarding abuse |

The quality of studies varied. Key issues identified with the quantitative studies related to poor justification of sample sizes and reporting of non-responders, making conclusions regarding the representativeness of findings difficult to draw. Quality of qualitative studies was mixed. Instances of poor reporting of methods, particularly relating to data collection methods, made overall quality difficult to appraise. Mixed-methods studies were generally of high quality, although, limited reporting made it difficult to assess whether the different components of the studies adhered to quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved. Overall, study quality made potential bias within studies difficult to assess.

Critical integrative synthesis18 led to the development of a model of overarching domains and sub-themes. Our model of key determinants (Table 3) encompassed four domains with 10 sub-themes.

Table 3.

Key determinants of opioid availability in Asia.

| Domain | Sub-theme |

|---|---|

| Legal, regulatory and socio-political | International and national law Political and socio-economic context |

| Opioid availability | Formulary Continuity of supply |

| Opioid accessibility | Bureaucracy and dispensing Affordability of medicine Logistical challenges |

| Prescribing | Attitudes and knowledge Clinical guidelines Human resources for prescribing (physicians, nurses, pharmacists) |

In the text below, we report a synthesis of qualitative and quantitative findings. Supporting quantitative and qualitative data were selected to illustrate concepts represented.

Legal, regulatory and socio-political

This domain incorporates factors at international and national levels perceived to influence opioid availability in Asian countries. There is limited evidence that nations in Asia acknowledge legal responsibility for enabling access to opioids as an essential aspect of healthcare. As part of an international review into drug laws, none of the included Asian countries had laws which established the government’s responsibility to ensure adequate provision of opioid drugs for medical and scientific purposes.37 No qualitative studies elicited views on legal, regulatory and socio-political factors affecting access to opioids.

Participants within an Asia-wide survey identifying factors affecting opioid availability report control measures applicable to international trade, such as need for import or export authorisations, as barriers in six countries in west and south Asia. Respondents in a survey into the use of Tramadol in southeast Asia, strongly agreed that tighter regulation would lead to a significant reduction in the medical availability of Tramadol, raising particular concerns about subsequent lack of appropriate medication for cancer pain.32 Historically, in India, physicians reported how a law in 1985 which aimed to quell abuse and trafficking of narcotics was responsible for the medical profession becoming hesitant to use Morphine and, in the months and years following the law, pharmacies all over the country stopped stocking Morphine.39 This law was superseded in 2014 by the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Amendment Bill which aimed to reduce bureaucracy to ensure continuity of supply of opioids. However, in spite of this, a recent survey of clinicians found that 61% of clinicians had concerns about administrative burden and 56% feared possible scrutiny of records by regulating bodies or law enforcement agencies for prescribing opioids.33 Another cross-sectional study found that over half the country reporters identified “negative language in existing drug laws” and half had laws forbidding driving whilst on opioids.23

Countries which have greater integration of palliative care in to the health system reported that higher opioid usage and the extent of government expenditure on healthcare predicted opioid usage.25 In a comparative study, US respondents were twice as likely as Japanese physicians to indicate that opioid treatment was a legal expectation.21 Whilst no Asian country has laws which prohibit opioid availability, a lack of legal obligation to enable access to opioids creates a regulatory climate where clinicians may fear criminal accountability for mis-prescribing. A cross-sectional study in China, found that 62.8% of clinicians had concerns about regulatory investigation for prescribing opioids.30

Opioid availability

In the context of the barriers identified above, opioid availability refers to permitted opioid formulations as well as issues relating to continuity of supply. Contradictory findings were identified, with different studies affirming and denying the availability of opioids, particularly Morphine, in Asian countries. In Thailand, Codeine and Morphine were reported as the most commonly available drugs, whilst an Asia-wide study reported that Tramadol is commonly the only strong analgesic available for treating cancer pain.32 Seven countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Kazakhstan and Laos) were identified by a cross-sectional study as not having oral immediate release (IR) Morphine available.23

Many included studies identified issues related to availability in terms of continuity of supply. In Thailand, limits are set on the amount prescribed by health insurance types and the amount of oral opioids in the pharmacy’s stock.24 Issues in sourcing from industry or imports 3 (33% participants) in east and southeast, 6 (29%) in south and west reported as barriers in a cross-sectional survey as barriers to continuity of supply. In this context, clinicians report serious problems treating their patients.

“The pain wasn’t coming under control if he didn’t take Morphine. And later [Palliative Care doctor] had to increase the initial dose. Then it became very difficult to get Morphine. There was no supply.” [Bangladeshi clinician (p5)]37

“Sometimes, [the gap in supply] may be 1 month, then it is very terrible job to handle the patients.” – [Registered Nurse 7, palliative care nurse, India (519)]34

Opioid accessibility

Opioid accessibility refers to practical factors influencing access to opioids when opioids are technically available within a country. Several included studies report bureaucratic barriers to accessing opioids, at national policy level and due to hospital pharmacies at local level, with onerous regulatory frameworks for prescription of opioids reported across Asia.31 For example, an ethnographic study of a cancer hospital in South India reports the difficulties of accessing opioids, even when they are technically available within a pharmacy:

“Right now, it [Morphine] has come, but the Drug Inspector has to come and open [the package] and then we will distribute. Today is the 3rd day, Friday, Saturday, and Monday; 3 days’ gap. Patients came. I told to the patients, “wait till Monday or you can take weak opioid. . . and you can take steroid . . . and then we will write for Voveran (diclofenac) and Rantac (ranitidine)”. . . Sometimes, they beg from other people that are rich in their family, because, [they say] ‘without this tablet, I cannot reduce my pain, I can’t reduce my breathlessness, I can’t reduce my cough’.” [palliative care nurse, India (p519)]34

In spite of low cost options, the cost of opioids was identified as a barrier to access in several studies. In China, 16.5% of clinicians reported patient inability to pay for analgesics as a barrier.30 A review of the affordability of opioids found a negative correlation between a days’ wages and the country income category: the lower the income, the more working days required to pay for the treatment.22 Patients paid the full cost of all medications in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Nepal and the Philippines.23 This revealed inequities in access in Bangladesh, whereby more affluent patients are able to afford expensive formulations such as fentanyl transdermal patches, whilst more deprived patients struggled to pay for any opioid.37

Permitted prescribing centres identified by this review were commonly cancer centres, in urban areas. Evidence suggests practical challenges of travel to prescribing centres as barriers to opioid accessibility:

“Morphine is more available at South India Cancer Hospital (SICH) than most of India. . . The typical patient was financially destitute, illiterate, suffering from metastatic disease, and had travelled hundreds of kilometres to seek care.” [field observation, research ethnographer, India (p517)]34

“They want access to health care which is very difficult in our country, because the national cancer Hospital is in Dhaka. There are not well organised places in other hospitals . . .It’s again a bit of financial constraint that causes the problem because they can’t travel so much and we cannot go to them.” [S3, Physician, Bangladesh (p6)]37

Prescribing

Even when technically available and accessible from pharmacies further barriers were faced by clinicians to prescribing opioids. Several Asian countries require physicians and other clinicians to have a special authority/licence to prescribe opioids.23 Cambodia, China, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines and Thailand had restrictive access to these forms, whilst Cambodia, Mongolia, Pakistan and the Philippines required payment for these prescription forms.23 In spite of such regulatory precaution, in Bangladesh this does not ensure patients and adequate supply of medicine and limitations are commonly placed upon prescriptions:24

“Availability is an issue . . . we do have to put our seal and our name and registration number and send it. Patients need, say, for one month-if they need thirty, they are given ten.” [S3, Physician, Bangladesh (p5)]37

Nurses are allowed to prescribe with special authority in Bhutan and the Philippines, and in emergency situations in Afghanistan, and are particularly identified as an enabler of access in Thailand. Yet, only ten community hospitals in Thailand (out of 257 hospitals overall) permitted nurse prescribing. In India in particular, availability of clinician and nurse human resources was reported as a barrier to pain management:

With rare exception, Morphine (oral and intravenous) was prescribed exclusively by two or three physicians in the palliative care outpatient clinic [field observation, research ethnographer, India (p517)].34

In part, the nurses’ lack of engagement with pain assessment and management related to nurse-to-patient ratios that sometimes exceeded 1 nurse for more than 60 patients, negating the ability to provide individualized care [field observation, research ethnographer, India (p518)].34

In South India, access to Morphine was said to be largely limited to patients seen by the palliative care service (20% of total patients).34 Another study in India found that only 61% of clinicians within the study felt that it is appropriate both legally and clinically to prescribe opioids in acute pain due to trauma.33

In Thailand, for palliative care patients who could not go to the hospital due to poor physical status, caregivers were permitted to obtain opioids on behalf of patients in nearly 80% of hospitals. However, models of emergency prescribing (defined as one when there is an immediate need for relieving strong cancer pain but the physician is not able to physically provide a prescription) were scarce across Asia. Only five states allowed emergency prescribing by fax or phone, namely Bhutan, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia and Pakistan.23 In Thailand, limits are set on the amount (of Morphine) prescribed by health insurance types and the amount of oral opioids in the pharmacy’s stock.29

Across many studies, negative attitudes, concerns and knowledge of prescribers limited provision of opioid medications. In India, “Some nurses felt that even Morphine was ineffective in treating cancer pain, as they viewed opioid side effects as offsetting any benefit”34 and in spite of pain management provided by palliative care services, uptake was commonly limited due to patients’ negative perceptions of palliative care. Negative attitudes are perhaps associated with a lack of knowledge of the benefits of opioids. One study of 300 physicians and 58 policymakers/regulators reported that 62.1% of physicians and 74.5% of policymakers/regulators had inadequate knowledge of the benefits of opioids for cancer pain and lack of training opportunities were perceived as a barrier to opioid availability.24

Finally, in spite of positive initiatives to enable provision in Thailand, clinicians report personal concerns:

“Prescribing Morphine to be used at home is new for this District Health Service (DHS). I am concerned about the drug abuse; therefore, this DHS does not prescribe Morphine to be used in the community/at home. We need to set a guideline first.” [PHAR1 (p343)]40

Clinical guidelines for pain relief are reported within included studies as enablers of access to opioids. In the Philippines, a survey of clinicians found that 72% were aware of the WHO Ladder for Pain Control.26 In South Asia more generally, the inclusion of Tramadol on step two of the WHO ladder, as an enabler of access to pain relief. However, a study from Bangladesh reported frustration that Tramadol was the only available option, reporting:

We are compensating with various other drugs for stage two, three . . . of the [WHO] step ladder. We cannot get sufficient Morphine [Medical Director, Bangladesh (p5)].37

Discussion

Our study is the first to systematically review evidence of enablers and barriers of access to opioids in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia and how these manifest in practice. Our review highlights how legal, regulatory and socio-political actions intended to enable availability of opioids, unintentionally limit availability and practical access to opioids within countries. We demonstrate how barriers at international, national and sub-national levels, interact to limit opioid availability, opioid accessibility and potential for appropriate prescribing of opioids. The consequence of these interrelated factors is inadequate supply and consumption of opioids, resulting in avoidable patient suffering. Of concern, inadequate consumption at sub-national levels due to identified barriers, provides data to inform estimates of future requirements for opioids at national level, for submission to international level (INCB). Thus, a self-reinforcing model of inadequate opioid availability and consumption is perpetuated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A framework of legal and regulatory barriers to opioid availability.

We structure our discussion in terms of key messages for stakeholders at international, national and national levels in context of thematic findings.

Legal, regulatory and socio-political

There is evidence that international and national laws foster a policy environment, where opioids are technically permitted, but access is not positively enabled for patients in need. International drug law aims to ensure balance in national policies on controlled substances in terms of availability and accessibility of controlled medicines. Although all Asian countries are signatories of the Single Convention on Narcotics, few Asian countries have laws specifically noting governments’ obligations to enable access to controlled substances for medical and scientific purposes. Along with “negative language” reported in laws, such factors may explain findings relating to clinicians fearing legal repercussions from prescribing opioids, as opposed to feeling a legal expectation to do so within clinical guidelines. National lawmakers should legislate to acknowledge governmental obligation to ensure safe access to controlled substances. This would be consistent with the aims of the Single Convention and may help allay clinician concerns regarding redress for prescribing opioids and promote appropriate access.

Opioid availability

A lack of continuous supply of opioids combines issues relating to availability and accessibility. Sourcing from industry and issues relating to importing opioids were reported as barriers to adequacy of supply. Health systems across Asia should consider streamlining bureaucratic processes aimed at increasing safety of opioid regulations, which paradoxically limit availability and cause patient suffering. India for example, passed the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Amendment Bill, 2014 aimed at reducing bureaucracy to ensure continuity of supply of opioids, although the practical effects of this law are yet to be evaluated.41 All nations in Asia should ensure that bureaucratic processes enable, rather than limit, continuity of supply of opioids. Increased education and training opportunities for regulators, and clinicians are also required, to both change negative perceptions of opioids and increase human resources for prescribing.

The finding that Codeine and Tramadol were the most readily available opioids supports suggestions that layers of legal and regulatory process are removed for substances not under international control. Clinicians, who use Tramadol as part of WHO guidelines appear to be justified in their concerns that greater regulation may limit practical access to Tramadol and remove their only appropriate medication for cancer pain relief. This is supported by a survey conducted by the INCB itself which confirmed the negative impact of an international scheduling on the availability of Tramadol. In total, 72% of responders (33 of 46 countries) expressed concern that the introduction of control measures would limit accessibility to Tramadol and make doctors more reluctant to prescribe it.42 Yet, there are ongoing reports that due to misuse and abuse of Tramadol due to over-availability in Asia, the International Narcotics Control Board is still currently reviewing whether to bring Tramadol under international control.43 Doing so would make Tramadol subject to many of the structural barriers to accessible medicines identified by this review and limit the availability of the only practical pain medication currently available to many clinicians in Asia.

Opioid accessibility

In circumstances where appropriate prescribing is possible, patients across Asia face further barriers to accessing opioids due to barriers imposed by health services and the cost of medicine. Opioids are currently less affordable in Asia than in western countries.28 International and national regulators have an obligation to ensure that essential opioids are made available at an affordable price in accordance with the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (the TRIPS Agreement) to make it easier for poorer countries to obtain cheaper generic versions of patented medicines.44 In particular, low-cost formulations, (e.g. oral Morphine) should be prioritised to ensure that cost does not limit the prospects of patients in medical need of pain relief.

Health facilities licensed to prescribe opioids are scarce across Asia, presenting logistical challenges to seriously ill patients in presenting at an appropriate centre. Well-functioning opioid prescribing centres were identified by this review, commonly Cancer Hospitals and palliative care centres. However, such centres are commonly centralised around urban areas. Coverage of prescribing centres should be prioritised as a key aspect of efforts to achieve Universal Health Coverage in line with nations’ commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals. One approach to doing this would be to identify locally appropriate, safe and effective prescribing models in the Asian context, and considering how such models may be transferrable to other settings, to promote opioid availability and accessibility, outside of urban centres.

Prescribing

Our review found evidence from Asia suggesting that a lack of human resources for prescribing is a key barrier to opioids availability. It is also of concern that we identified reluctance amongst clinicians to prescribe for medical problems (e.g. trauma), not accounted for by the WHO pain ladder.33 Opioid training courses are available across Asia, and physicians at all levels of health systems should be encouraged to attend. However, it should be noted that most training courses are for the purpose of prescribing opioids for cancer pain only, and programs are urgently required which teach appropriate prescribing for other conditions that opioids are indicated for, e.g. trauma.

When opioid treatments do reach hospital pharmacies, a further layer of bureaucratic and regulatory delays limit the chances of patients with legitimate need from receiving appropriate treatment. Our review also found evidence that due to shortages of medicines, patients legitimately prescribed opioids do not receive their full prescriptions, leading to inadequate dosing. Furthermore, regulations which do not permit pharmacists to correct errors on prescriptions, create a further potential barrier to patients receiving their opioid prescriptions, even when they are technically “available.” Other Asian nations may consider following the example of Thailand, which has removed this layer of bureaucracy for patients with a legitimate prescriptions, with minor completion errors (e.g. a spelling mistake). Health systems should further consider enabling nurse-prescribing of opioids, which was identified as an enabler of access in Thailand as part of a strategy to improve the coverage of opioid prescribing to enhance availability and reduce logistical challenges faced by patients in need of opioid treatments.

Impact of COVID-19

Since our analysis was conducted, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased morbidity and need for opioids in Asia.45 In response, the INCB has encouraged governments worldwide to avail of flexibility within their regulations in the context of acute emergencies, which allow simplified control procedures for the export, transportation and supply of medicinal products containing controlled substances.46 We endorse the leadership from the INCB in this regard. However, it remains unclear whether Asian governments will utilise this flexibility to meet the need for opioids of COVID-19 patients. Additionally, this approach would appear to place the emerging needs of COVID-19 patients ahead of those with more predictable needs for opioids. Given the legal and regulatory barriers to opioid availability and accessibility identified by our review in context of the estimates system, we reiterate our call for amended international laws and regulations of controlled substances aimed at meeting the needs of all patients who urgently require appropriate pain treatment.

What this study adds

Our study reveals how barriers at international level result in overly restrictive laws and regulations at national level. A lack of education amongst policymakers regarding the benefits of opioids allows uncritical continuity an absence of training opportunities and restrictive laws and regulations which limit overall stocks and trades in controlled substances. The consequences of such barriers at international and national level are to reinforce negative perceptions of opioids at sub-national level, leaving an inadequate prescribing workforce, working within a context of bureaucratic barriers.

Overall, systemic barriers at international, national and sub-national levels, interact to perpetuate a cycle of inadequate opioid availability and accessibility, leading to inadequate consumption (Figure 2). Perversely, data relating to inadequate consumption are then used by nations to estimate their requirements for opioids for the following year for submission to the International Narcotics Control Board, which then places an upper limit on stocks and trades for nations based on inadequate assessments of requirements.

International and national leadership is urgently required, to “re-frame” discourse relating to opioids to create a positive obligation to health systems to enable availability and accessibility of opioids.47 Doing so may help streamline bureaucratic process relating to opioid access and create a positive obligation amongst prescribers to prescribe opioids based on present patient problems, supported by clinical guidelines, not restricted by overly prohibitive drug laws.

Finally, access to palliative care was identified as an enabler of access to opioids. This may be accounted for by the tireless advocacy undertaken by many palliative care activists to promote access to palliative care as a basic human right. Worryingly, negative patient perceptions of care are reported as a barriers to accessing palliative care and associated pain treatment. Of further concern, our review identified no evidence regarding access to opioids for purposes other than cancer pain, for example, trauma. Focussed advocacy from health lobbies including, notably, emergency medicine and maternal health, is required to promote access to opioids as a key aspect of good healthcare at all levels of health systems.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this review is that it uses empirical evidence to highlight how barriers to safe opioid availability at international, national and national levels interact to limit the prospects of patients in need of opioid treatments at sub-national level. By drawing upon empirical evidence of how legal and regulatory barriers manifest at sub-national levels, we identify the inadequacy of global opioid policy, from whence national and sub-national barriers emerge.

Our review used robust methods, adheres to standard guidelines, and critically appraises and reviews included studies and the evidence derived. We aimed to locate all available peer reviewed published evidence. We searched six databases including trial registries, however, grey literature was not specifically searched and therefore potentially relevant policy documents may have been missed. However, the focus of our review was on how policies and regulations manifest in practice based upon research evidence.

A weakness of the study is that we included English language papers only, due to resource constraints, therefore studies published in local languages which may have been relevant have not been identified or included. However, from our search strategy, no studies were excluded for language reasons and studies from Asia-based journals are included. Included studies were also of mixed quality, the conclusions of our review should therefore be interpreted in the context of varying quality of evidence identified. Finally, most included papers related to South Asia, Southeast and East Asia with only a few identified and included from Central Asia. Our conclusions reflect composite findings from available evidence, but we would recommend studies to be further studies conducted in Central Asia to identify legal and regulatory barriers. We would also encourage researchers to adopt our methods to conduct analyses of other world regions.

Conclusion

Legal and regulatory barriers at international, national and sub-national levels create and reinforce a system of inadequate availability and accessibility of opioids in Asia. The Single Convention on Narcotics imposes a mandate to restrict access to opioids on national governments and contributes to negative perceptions of the benefits of opioids. However, after 60 years of the Single Convention, national drug laws and regulations appear overly restrictive. Education on the benefits of opioids is urgently needed at national and sub-national levels, to reduce negative attitudes and increase human resources for prescribing. However, global policy reform is urgently required to end the cycle of inadequate availability of opioids which is endemic across Asia.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_file_1 for Perceptions and experiences of laws and regulations governing access to opioids in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia: A systematic review, critical interpretative synthesis and development of a conceptual framework by Joseph Clark, Sam Gnanapragasam, Sarah Greenley, Jessica Pearce and Miriam Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, Supplementary_File_2 for Perceptions and experiences of laws and regulations governing access to opioids in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia: A systematic review, critical interpretative synthesis and development of a conceptual framework by Joseph Clark, Sam Gnanapragasam, Sarah Greenley, Jessica Pearce and Miriam Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, Supplementary_File_3 for Perceptions and experiences of laws and regulations governing access to opioids in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia: A systematic review, critical interpretative synthesis and development of a conceptual framework by Joseph Clark, Sam Gnanapragasam, Sarah Greenley, Jessica Pearce and Miriam Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lucia Crowther for assistance with quality appraisal of included studies and copy-editing and Professor David Currow, for thoughtful reflections upon our project throughout.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Authors have contributed to the following categories for authorship: (1a) study conception and design: JC, SG, and MJ (1b) acquisition of data: JC, SG, SG, JP (1c) analysis and interpretation of data: JC, SG, JP, LC, MJ, drafting the article: JC, SG, SG, critical revision: all. All authors have approved the final article and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Joseph Clark  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1410-0996

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1410-0996

Sarah Greenley  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3788-6437

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3788-6437

Miriam Johnson  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6204-9158

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6204-9158

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Manjani D, Kunnumpurath S, Kaye AD. Availability and utilization of opioids for pain management: global issues. Ochsner J 2014; 14: 208–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2018; 391: 1391–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. 2019. https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/ (accessed 19 December 2019).

- 4. World Health Organization. Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience, https://extranet.who.int/rhl/guidelines/who-recommendations-intrapartum-care-positive-childbirth-experience (2018, accessed 19 December 2019). [PubMed]

- 5. Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Schneider CH. The global burden of musculoskeletal pain—where to from here? Am J Public Health 2019; 109(1): 35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anderson JE, Cocanour CS, Galante JM. Trauma and acute care surgeons report prescribing less opioids over time. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2019; 4: e000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miskovic A, Lumb AB. Postoperative pulmonary complications. Br J Anaesth 2017; 118(3): 317–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Currow D, Ekstrom M, Abernethy AP. Opioids for chronic refractory breathlessness: right patient, right route? Drugs 2014; 74(1): 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anderson RA, Grant L. What is the value of palliative care provision in low-resource settings? BMJ Glob Health 2017; 2(1): e000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brennan F. Palliative care as an international human right. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 33(4): 494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. International Narcotics Control Board. Single convention on narcotic drugs, 1961, https://www.incb.org/incb/en/narcotic-drugs/1961_Convention.html (2020, accessed 27 February 2020).

- 12. Clark J, Johnson M, Fabowale B, et al. Does the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) sufficiently prioritise enablement of access to therapeutic opioids? A systematic critical analysis of six INCB annual reports, 1968–2018. JOGHR 2020; 4: e2020042. [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Joncheere CP. Launch of the 2019 annual report of the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) [video file]. 2020 Feb 27 [cited 2020 Mar 11], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gT-6fLvLrTc&t=2426s (accessed 11 March 2020).

- 14. Systematic Reviews. CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Centre for reviews and dissemination, York, UK: University of York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009: 6(7): e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. International Narcotics Control Board. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2019, https://www.incb.org/incb/en/publications/annual-reports/annual-report-2019.html (2020, accessed 19 August 2020).

- 17. Clark J, Gardiner C, Barnes A. International palliative care research in the context of global development: a systematic mapping review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018; 8: 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552). Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Method 2006; 6(1): 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duthey B, Scholten W. Adequacy of opioid analgesic consumption at country, global, and regional levels in 2010, its relationship with development level, and changes compared with 2006. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 47(2): 283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Majeed MH, Nadeem R, Kokar MA, et al. Adequacy of pain control in patients with advanced cancer in Pakistan. J Palliat Care 2019; 34(2): 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Onishi E, Kobayashi T, Dexter E, et al. Comparison of opioid prescribing patterns in the United States and Japan: primary care physicians’ attitudes and perceptions. Fam Med World Persp 2017; 30(2): 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Lima L, Pastrana T, Radbruch L, et al. Cross-sectional pilot study to monitor the availability, dispensed prices, and affordability of opioids around the globe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 48(4): 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cleary J, Radbruch L, Torode J, et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Asia: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Annals of Oncol 2013; 24(Suppl 11): 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Srisawang P, Rashid H, Hirosawa T, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and barriers of physicians, policy makers/regulators regarding use of opioids for cancer pain management in Thailand. Nagota J Med Sci 2013; 75: 201–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gilson AM, Maurer MA, LeBaron V, et al. Multivariate analysis of countries’ government and health-care system influences on opioid availability for cancer pain relief and palliative care: more than a function of human development. Palliat Med 2013; 27(2): 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Javier MO, Calimag MP. Opioid use in the Philippines–20 years after the introduction of the WHO analgesic ladder. Eur J Pain 2007; 1 (Suppl 1): 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khan F, Ahmad N, Iqbal I, et al. Physicians knowledge and attitude of opioid availability, accessibility and use in pain management in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull 2014; 40: 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Lima L, Sweeney C, Palmer JL, et al. Potent analgesics are more expensive for patients in developing countries. J Pain Pharmacother 2004; 18(1): 59–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thongkhamcharoen R, Phungrassami T, Atthakul N. Regulation of opioid drugs in Thai government hospitals: Thailand national survey 2012. Indian J Palliat Care 2014; 20(1): 6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu S, Wang XS, Heng Y, et al. Special aspects of cancer pain management in a Chinese general hospital. Eur J Pain 2001; 5(Suppl 1): 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Berterame S, Erthal J, Thomas J, et al. Use of and barriers to access to opioid analgesics: a worldwide, regional, and national study. Lancet 2016; 387(10028): 1644–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vijayan R, Afshan G, Bashir K, et al. Tramadol: a valuable treatment for pain in Southeast Asian countries. J Pain Res 2018; 11: 2567–2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Singh S, Prasad S, Bhatnagar S, et al. A cross-sectional web-based survey of medical practitioners in India to assess their knowledge, attitude, prescription practices, and barriers toward opioid analgesic prescriptions. Ind J Palliat Care 2019; 25(4): 567–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. LeBaron V, Beck SL, Maurer M, et al. An ethnographic study of barriers to cancer pain management and opioid availability in India. Global Health Cancer 2014; 19: 515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Husain SA, Brown MS, Maurer MA. Do national drug control laws ensure the availability of opioids for medical and scientific purposes? Bull World Health Organ 2014; 92: 108–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dehghan R, Ramakrishnan J, Ahmed N, et al. The use of morphine to control pain in advanced cancer: an investigation of clinical usage in Bangladesh. Palliat Med 2010; 24(7): 707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McDermott E, Selman S, Wright M, et al. Hospice and palliative care development in India: a multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 35(6): 583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Joranson DE, Rajagopal MR, Gilson AM. Improving access to opioid analgesics for palliative care in India. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002; 24(2): 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kitreerawutiwong N, Mekrungrengwong S, Keeratisiroj O. The development of the community-based palliative care model in a district health system, Phitsanulok Province, Thailand. Ind J Palliat Care 2018; 24(4): 436–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaur G, Kaur G, Bajwa SS. Inside preview of procuring narcotic license. Ind J Anaesth 2015; 59(6): 386–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. International Narcotics Control Board. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2013. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- 43. International Drug Policy Consortium. What the INCB June alerts tell us on human rights & Tramadol, https://idpc.net/incb-watch/updates/2018/06/incb-new-alerts-from-the-board-june-2018 (2018, accessed 10 February 2020).

- 44. United Nations. Access to affordable medicine, https://developmentfinance.un.org/access-affordable-medicines (2020, accessed 2 March 2020).

- 45. Radbruch L, Knaul FM, De Lima L, et al. The key role of palliative care in response to the COVID-19 tsunami of suffering. Lancet 2020; 395(10235): 1467–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. International Narcotics Control Board. INCB, WHO and UNODC statement on access to internationally controlled medicines during COVID-19 pandemic, https://www.incb.org/incb/en/news/news_2020/incb-who-and-unodc-statement-on-access-to-internationally-controlled-medicines-during-covid-19-pandemic.html (2020, accessed 21 August 2020).

- 47. Clark J, Barnes A, Gardiner C. Reframing global palliative care advocacy for the sustainable development goal era: a qualitative study of the views of international palliative care experts. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 56(3): 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_file_1 for Perceptions and experiences of laws and regulations governing access to opioids in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia: A systematic review, critical interpretative synthesis and development of a conceptual framework by Joseph Clark, Sam Gnanapragasam, Sarah Greenley, Jessica Pearce and Miriam Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, Supplementary_File_2 for Perceptions and experiences of laws and regulations governing access to opioids in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia: A systematic review, critical interpretative synthesis and development of a conceptual framework by Joseph Clark, Sam Gnanapragasam, Sarah Greenley, Jessica Pearce and Miriam Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, Supplementary_File_3 for Perceptions and experiences of laws and regulations governing access to opioids in South, Southeast, East and Central Asia: A systematic review, critical interpretative synthesis and development of a conceptual framework by Joseph Clark, Sam Gnanapragasam, Sarah Greenley, Jessica Pearce and Miriam Johnson in Palliative Medicine