Abstract

Activatable theranostics, integrating high diagnostic accuracy and significant therapeutic effect, holds great potential for personalized cancer treatments; however, their chemodynamic modality is rarely exploited. Herein, we report a new in situ activatable chemodynamic theranostics PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB to specifically recognize and eradicate cancer cells with H2O2-catalyzed hydroxyl radical (•OH) burst cascade.

Methods: The nanomicelles PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB were constructed by self-assembly of acid-responsive copolymers incorporating ascorbates and acid-sensitive Schiff base-Fe2+ complexes as well as H2O2-responsive adjuvant Cy7QB.

Results: Upon systematic delivery of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB into cancer cells, the acidic microenvironment triggered disassembly of the nanomicelles. The released Fe2+ catalyzed the oxidation of ascorbate monoanion (AscH-) to efficiently produce H2O2. The released H2O2, together with the endogenous H2O2, could be converted into highly active •OH via the Fenton reaction, resulting in enhanced Fe-mediated T1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The synchronously released Cy7QB was activated by H2O2 to produce a glutathione (GSH)-scavenger quinone methide to boost the •OH yield and recover the Cy7 dye for fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging.

Conclusion: The biodegradable PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB designed for tumor-selective multimodal imaging and high therapeutic effect provides an exemplary paradigm for precise chemodynamic theranostic.

Keywords: chemodynamic theranostics, activatable, reactive oxygen species, Fenton reaction, multimodal imaging

Introduction

Nanotheranostics, the integration of multimodal diagnostic and therapeutic modalities into a single system, provides opportunities for nanomedicine-based personalized precision treatments 1-6. In contrast to the conventional nanotheranostics with “always-on” diagnostic signals and pharmacological effects 7-11, the activatable, in particular the stimuli-responsive, materials have attracted great focus for precision medicine 12-19. These nanomaterials can sense endogenous 20 or exogenous stimuli 21, such as pH changes 22, different enzyme levels 23-25, reactive oxygen species (ROS) 26, laser irradiation 27, 28, or temperature changes 29 and are relatively safe and usually non-toxic. Therefore, enhancement of the diagnostic accuracy towards tumor microenvironments as well as the latent therapeutic effects are essential requirements of these nanomaterials designed for the improved treatment efficacy 30, 31.

Among the tumor-related stimuli, ROS species have been viewed as targets for cancer diagnosis and therapy because of high ROS levels in cancer cells 32-36. Recently, chemodynamic therapy (CDT) that can generate highly cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals (•OH) from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) via the Fenton reaction (Fenton-like) by catalyzing ferrous ion (Fe2+) or other Fenton-like ions, has been demonstrated to have potential for cancer treatment 37-44. However, CDT's limitations lie in the poor tumor selectivity and low intratumoral •OH yields 45, 46. Furthermore, the efficacy of CDT is reduced because of the relatively low cellular concentrations of H2O2 and Fe2+, decreasing Fenton reaction efficiency and •OH yield 47-49 as well as clearance of •OH by glutathione (GSH)-abundant antioxidation systems 50-53. Therefore, supplementation of additional CDT agents or decreasing GSH concentration should be effective strategies for enhancing the Fenton reaction efficiency and accelerating toxic •OH generation. Despite significant improvement observed using inorganic nanotheranostic systems 54, 55, such as MnO2/GOX and Fe3O4/GOx 35, 38, 47, 49, the single CDT was still not effective against the localized solid tumors 56-58. In this context, engineered biodegradable chemodynamic theranostics with tumor-selective multimodal imaging and significant in-situ yield of •OH could indisputably enhance the treatment accuracy and efficacy.

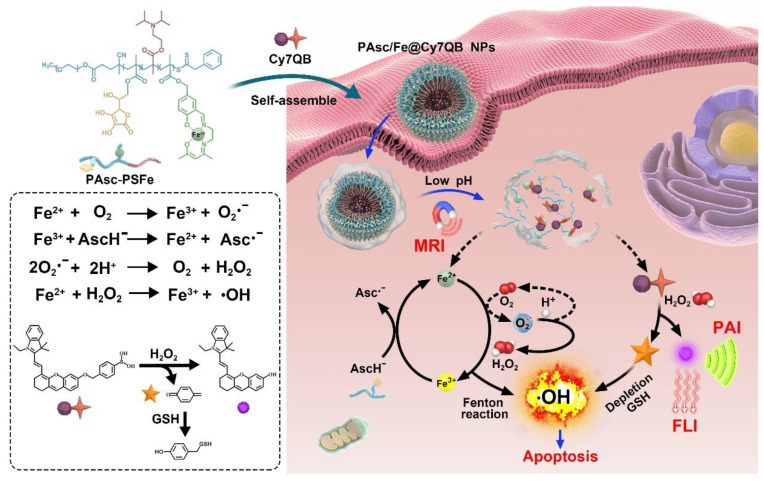

In view of the above concerns, herein, we developed theranostic nanomicelles (PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB) with tumor-selective imaging, affording precise and effective eradication of the localized solid tumor via an H2O2-catalyzed •OH burst cascade. Briefly, the polymeric matrix (PAsc-PSFe) was synthesized by copolymerization of ascorbate (polymerized ascorbic acid, PAsc) 59, pH-sensitive segments of Schiff base embedded with Fe2+ (polymerized Schiff base-Fe2+ complex, PSFe), and 2-(diisorpropylamino) ethyl methacrylate (polymerized diisorpropylamino, PDPA). This complex could be packed into a hydrophobic core due to its intrinsic hydrophobicity, and become hydrophilic after decomposition of the Schiff base and protonation of amine groups in an acidic environment 60, 61. The PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB nanomicelles were obtained after encapsulating a newly synthesized H2O2-responsive probe (Cy7QB, a Cy7 dye incorporated with the quinone methide-generating boronate ester) within the hydrophobic core of PAsc-PSFe.

As illustrated in Scheme 1, after systematic administration, the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB nanomicelles accumulated at the tumor site through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, then internalized and endocytosed by tumor cells. The acidic environment of endosomes/lysosomes could subsequently induce decomposition of the Schiff base and PDPA protonation, leading to free Fe2+, ascorbate monoanion (AscH-) and the adjuvant Cy7QB to the cytoplasm. At this stage, the Fe-mediated T1-magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) signal was enhanced dramatically along with the release of Fe2+. Notably, the Fe2+ could catalyze the oxidation of AscH- into ascorbate radical (Asc•-) to produce H2O2, which, along with the endogenous H2O2, could be efficiently converted into highly active •OH via the Fenton reaction. Further, the adjuvant Cy7QB could also be activated by H2O2 to generate the GSH-scavenger quinone methide and enhance •OH yield. The concomitantly generated dye Cy7 could be used as an imaging agent for fluorescence imaging (FLI) and photoacoustic imaging (PAI) to monitor the process. Thus, stimuli-activatable chemodynamic therapeutics are promising alternatives for tumor therapy, as they can significantly improve the bioavailability of therapeutic agents and inhibit tumor growth with high accuracy and minor side effects in vivo.

Scheme 1.

Fabrication procedure and scheme of the theranostic mechanism of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB for MRI/FLI/PAI multi-modal imaging and the H2O2-catalyzed •OH burst cascade.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals were of reagent grade and used without further purification. Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether (mPEG113-OH) and 2-(diisorpropylamino) ethyl methacrylate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (MO, USA). Diethyl ether, ethyl acetate and all other reagents were acquired from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific Co. Ltd (Beijing, China). Catalase (CAT) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent, Ltd (Shanghai, China). 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was acquired from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan), 4-nitrophthalonitrile fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), calcein-acetylmethoxylate (calcein-AM), and propidium iodide (PI) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (MO, USA). All aqueous solutions were prepared in ultrapure water, obtained from a Millipore MilliQ water purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA USA).

Characterizations

The optical characteristics of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB and Cy7QB were investigated using UV/visible absorption spectroscopy (Lambda-35 UV/visible spectrophotometer, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Fluorescence spectra of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB and Cy7QB were acquired on an LS-55 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were collected under a field emission high-resolution 2100 F transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) operating at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The size of the nanomicelles was measured using a ZEN3690 zetasizer (Malvern, USA).

Synthesis of compound PAsc-PSFe

FeCl2 (20.28 mg, 0.16 mmol) in 50 mL of ethanol was added dropwise to a solution of 150 mg PAsc-PS in 50 mL of ethanol, and stirred in a round-bottomed flask. To avoid oxidation of Fe2+, a few drops of glacial acetic acid were added. The resulting solution was magnetically stirred for 12 h under nitrogen at 40 °C, and then the solution was evaporated at 25 °C. The precipitated complex was filtered off, washed with ether, recrystallized from ice-cold ethanol, and dried in air. The optimized copolymer PDPA36-b-(PAsc0.82-PSFe0.18)65 (named PAsc-PSFe) was analyzed by 1H NMR in d6-DMSO. The copolymer PAsc53-PDPA36 (named PAsc-PDPA) with copolymerization of ascorbate and 2-(diisorpropylamino) ethyl methacrylate was synthesized according to a similar procedure and analyzed by 1H NMR in d6-DMSO. The copolymer PSFe12-PDPA36 (named PSFe-PDPA) with copolymerization of Schiff base-Fe2+ and 2-(diisorpropylamino) ethyl methacrylate was synthesized using a similar procedure and determined by 1H NMR in d6-DMSO.

Preparation of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB

The Cy7QB was synthesized according to a similar protocol previously described and successfully characterized by 1H NMR 62. Subsequently, Cy7QB (2 mg) dissolved in CH2Cl2 was added to deionized water (2 mL) solution of PAsc-PSFe (10 mg). The mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 4 h. PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was obtained after dialysis in a cellulose dialysis bag (MWCO 3500 Da) overnight. The resulting solution was freeze-dried for 6 h, and the dry product was re-dispersed in deionized distilled water (pH 7.4) to obtain the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB solution, which was passed through a 0.22 μm filter to sterilize the sample before use in cultured cells and mice.

H2O2 production in solution

The H2O2 concentration was measured by UV-vis absorbance of oxidized 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Briefly, HRP (150 mU/mL), and TMB (100 μM) were added to Fe2+ (0.16 mM)/ascorbate (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 mM), or only ascorbate (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 mM) solutions at pH 7.4 or 5.0, followed by incubation at 37 °C in the dark. Time-dependent UV-vis spectra were recorded. The characteristic absorbance of oxidized TMB at 370 nm was used to quantify the concentration of H2O2 based on the standard curve. Copolymers PAsc-PSFe, PAsc-PDPA and PSFe-PDPA were also treated similarly.

•OH production in solution

The amount of •OH was determined by the •OH-specific fluorescence turn-on probe benzoic acid (BA). Briefly, BA (10 µM), Fe2+ (0.16 mM) and ascorbate (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 mM) were added to PBS (pH 7.4 or 5.0) at 37 °C. Subsequently, the fluorescence spectra of the solution were recorded at determined time intervals and the emission intensity at 421 nm was plotted as a function of incubation time. PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, PAsc-PSFe, PAsc-PDPA and PSFe-PDPA were also treated similarly.

Cell culture and confocal fluorescence imaging

Human hepatoma cells (HepG2) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS (γ-irradiated and sterile-filtered) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% of CO2. HepG2 tumor cells were seeded in 35 mm confocal culture dishes and allowed to grow for 24 h. Cells were incubated for 2 h, the culture media were removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. Confocal fluorescence imaging analyses were performed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (ZEISS LSM 510 META, Germany). PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was excited at 680 nm and emission was recorded at 690-730 nm.

Cell uptake

Cell phagocytosis was assessed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). HepG2 cells were incubated with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (50 μg/mL) for various durations (0, 0.5, 1 and 2 h). The uninternalized nanomicelles were removed by washing several times with PBS.

Cellular ROS detection

The culture medium of HepG2 cells was replaced with fresh DMEM, followed by the addition of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, PAsc-PSFe, PSFe-PDPA and PAsc-PDPA (50 μg/mL). After 8 h, the medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS several times. Subsequently, 10 μM of the fluorescent probe 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was added for 30 min to react with ROS and generate the fluorescent product DCF, which could be observed by CLSM.

Cellular GSH levels

A group of HepG2 cells were treated with 0, 12.5, 25, 50 μg/mL of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB for 2 h. Another group was treated with catalase (CAT) before treatment with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (50 μg/mL). The cells were harvested, washed, and then lysed on ice in 40 μL of Triton X-100 lysis buffer. After 20 min, lysates were centrifuged and 10 μL of the supernatant was mixed with 50 μL of Ellman's reagent (0.5 mM DTNB). GSH concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm using a microplate reader. The levels of GSH in the treated cells were compared with the basal GSH levels in untreated cells.

In vitro cell viability assay

The cytotoxicity was studied by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. HepG2 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and cultured in 100 µL DMEM medium for 24 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the medium was replaced with 200 µL of fresh medium containing different concentrations of the PAsc-PDPA, PSFe-PDPA, PAsc-PSFe or PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB. After incubation for another 24 h, MTT (20 µL, 5 mg/mL) was added and incubated for 4 h to produce purple formazan. The supernatant was then replaced with 150 µL of DMSO. The optical density (OD) was monitored using a microplate reader at 570 nm. Cell viability (%) was determined by comparing the absorbance (570 nm) of the treated cells with that of untreated cells. Five independent experiments were performed for each test.

Tumor mouse model

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of South China Normal University, and the experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of South China Normal University. 4-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the Animal Experiment Center, Southern Medical University, and bred in an axenic environment. HepG2 tumor cells (1.0 × 106 cells) in PBS (100 μL) were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of each mouse. The animals were subjected to the treatments when the tumors reached approximately 100 mm3. The tumor volumes were calculated using the following formula: tumor volume = the greatest longitudinal diameter (length) × the greatest transverse diameter (width)2 × 0.5.

In vivo pH-responsive MRI

For in vivo T1-weighed MRI, PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (100 μL, 50 μg/mL) was intravenously injected into HepG2 tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice. After 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h, the MRI of tumor tissues was recorded by MRI BioSpin ICON 1T (Bruker) with a small animal specific body coil. The relative MRI signal intensity was measured using Image J software.

In vivo FLI and PAI imaging

PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (100 μL, 50 μg/mL) were injected into the tail veins of the HepG2 tumor-bearing mice, which were imaged and analyzed at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after injection with an NIR imaging system (Odyssey LI-COR, USA). The fluorescence signals were collected at λem = 710 nm under excitation with a 680 nm continuous laser. For PAI, the mice were pretreated with saline, catalase (CAT), or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 24 h. PAI was performed by a PA computed tomography system equipped with a 10 MHz, 10 mJ/cm2, 384 element ring ultrasound array, and an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) (Surelite II-20, Continuum, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 4-6 ns pulse duration and 20 Hz pulse repetition rate light source.

Blood circulation

The HepG2 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (100 μL, 50 μg/mL), and approximately 20 μL blood was collected at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h post-injection to which 980 μL of physiological saline containing 10 mM EDTA anticoagulant. Blood concentration of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was then determined by measuring the characteristic fluorescence of Cy7. The curve of blood terminal half-life of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was fitted based on the single-compartment pharmacokinetic model.

In vivo biodistribution

HepG2 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (100 μL, 50 μg/mL) for biodistribution measurement, and then the mice were sacrificed at various time points post-injection (each group contained three mice). The major organs of mice were collected at 8, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after the injection and were solubilized by tissue lysate for fluorescence measurement to determine Cy7 content.

In vivo excretion study

Mice were intravenously injected with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (100 μL, 50 μg/mL). Urine and feces of each mouse were then collected at various time points (12, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h) and solubilized in 10% DMSO in PBS. The absorbance at 710 nm was measured to determine the percentage of injected dose per gram of urine and feces.

Hemolysis tests

Whole blood was collected from mice in heparinized-tubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was washed three times with PBS by centrifugation and resuspended in the same buffer. This suspension of red blood cells was always freshly prepared and used within 48 h after collection. Subsequently, 500 mL of 2% erythrocytes (v/v) were mixed with 500 mL of 20, 40, 60, 80, or 100 μg/mL PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB solution and incubated at 37 °C for various times 63-65. Erythrocytes mixed with pure water were used as 100% hemolysis. The samples were centrifuged and the absorbance of the supernatants at 540 nm was measured. The percentage of hemolysis was calculated using the formula 66: Hemolysis (%) = (I/I0) × 100%, where I represents the absorbance of the supernatant for erythrocyte suspension with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, and I0 represents the absorbance of completely hemolyzed erythrocytes in pure water.

Antitumor activity

For the evaluation of the antitumor activity against HepG2 tumors, PBS, PAsc-PDPA (200 μL, 50 μg/mL), PSFe-PDPA (200 μL, 50 μg/mL), PAsc-PSFe (200 μL, 50 μg/mL), and PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (200 μL, 50 μg/mL) were intravenously injected after the tumor volume reached ~100 mm3. Tumor volumes were monitored every two days using a caliper to measure the perpendicular diameter of the tumors. The individual tumor volume (V) was calculated using the following equation: V = X × Y2/2, where X and Y represent the longest and shortest diameters of the tumors. Typical images of HepG2 tumors were obtained using a digital camera. The body weight of each mouse was recorded every two days.

Histologic examination

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed according to the method provided by the vendor (BBC Biochemical). After the experiments were completed, the mice were sacrificed. The major organs (liver, lungs, kidneys, heart, and spleen) and tumor tissues from the mice of the five groups were retrieved, cut into 4-μm-thick sections, fixed in a 10% paraformaldehyde solution for 8 h at room temperature, followed by dehydration with ethanol, and then processed routinely into paraffin. The sliced tissues were stained with H&E and examined using an inverted fluorescence microscope system (Nikon E 200).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using the Prism GraphPad software (Version 7.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical analyses were performed according to a t-test. In all cases, * was used for p < 0.05, **for p < 0.01, and *** for p < 0.001. Values were expressed as the mean ± SD. All experiments were performed at least in triplicates. The samples/animals were randomly allocated to the experimental group.

Results and Discussion

Molecular design principle and preparation of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB nanomicelles

Ascorbate is recognized as an antioxidant or a pro-oxidant 67. Generally, the endogenous ascorbate is thought to be an excellent reducing agent by donating one or two electrons to protect biomolecules from oxidative damage 68. However, ascorbate could also widely exert pro-oxidant effects in the presence of transition metal ions 69-71. The combination of ascorbate and iron has been used as an oxidizing system for the hydroxylation of alkanes, aromatics, and other oxidants 70, 72. The mechanism 73, 74 is summarized in Scheme 1 and Figure S1: the oxidation of ascorbate is catalyzed by Fe2+ to produce the Asc·- and superoxide radical (O2·-), Reaction (1) + (2); the O2·- in turn results in H2O2 and O2 dismutation, Reaction (3); Fe2+ reacts with H2O2 to generate Fe3+ and •OH in the classic Fenton Reaction (4).

Herein, we designed an in situ activatable theranostic system for H2O2-catalyzed •OH burst cascade to selectively enhance CDT's efficacy against cancers. The all-in-one nanomicelles PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB were constructed from acid-responsive polymersomes incorporating ascorbate and Schiff base-Fe2+ complex and Cy7QB in the membranes and inner aqueous cavities, respectively. First, the optimal ratio of ascorbate and Fe2+ was determined using BA to monitor the production of •OH via the Fenton reaction (Figure S2) 74. Subsequently, the optimized copolymer PAsc-PSFe was synthesized via copolymerization of the ascorbate and Schiff base-Fe2+ complex from the mPEG113-OH as a micelle matrix for the self-produced H2O2 and acid-triggered Fe2+ release (Figure S3), and the degrees of polymerization were determined by 1H NMR (Figure S4). For comparison, copolymer PAsc-PDPA polymerized with ascorbate and copolymer PSFe-PDPA polymerized with Schiff base-Fe2+ complex were also synthesized and characterized by 1H NMR (Figure S5-6). To avoid the clearance of •OH by GSH, the H2O2-activatable probe (Cy7QB), a GSH-scavenging adjuvant was synthesized and characterized by incorporating the quinone methide-generating moiety boronate ester into Cy7 75 (Figure S7-8). The final nanomicelles were then successfully obtained by self-assembly of PAsc-PSFe and Cy7QB; the loading capacity was measured as 84.15% (Figure S9) and the critical micelle concentration (CMC) was 30.12 µg/mL 76, 77 (Figure S10).

Characterization of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB

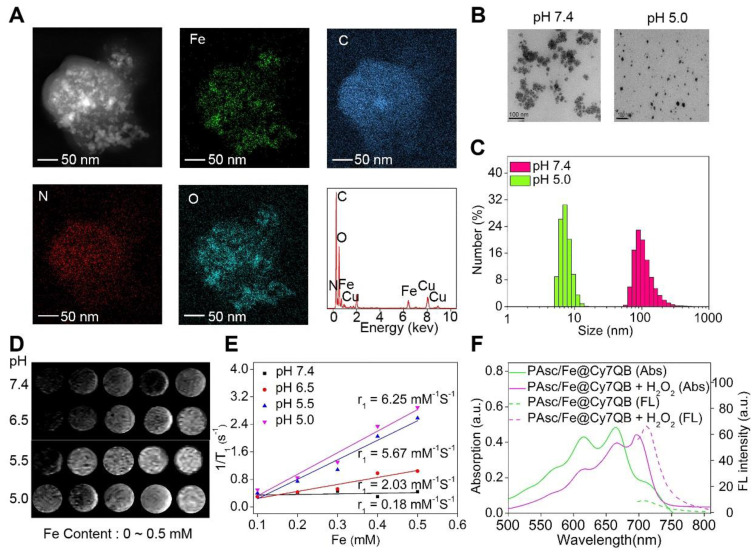

The energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS)-elemental mappings and spectrum revealed that PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB consisted of Fe, C, O, and N elements (Figure 1A), confirming the chemical composition of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB. TEM and dynamic light scattering (DLS) revealed that PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB had well-dispersed spherical morphology under physiological pH (pH 7.4) (Figure 1B-C). Under these conditions, the hydrodynamic size of the nanomicelles was almost unchanged in 48 h, indicating good stability (Figure S11). As a characteristic feature of solid tumors, high glycolytic activity facilitates lactate and H+ secretion, making the tumor microenvironment acidic 78. Under acidic conditions, the average hydrodynamic diameter of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was shortened from 110 ± 2 nm at pH 7.4 to 8 ± 2 at pH 5.0, apparent changes in their morphology were also observed due to the degradation of the acid-sensitive polymer (Figure 1B-C, S12-13). More importantly, T1-weighted MRI became gradually brighter from pH 7.4 to pH 5.0, and the longitudinal relativities r1 at pH 5.0 were 30-fold higher than at pH 7.4 because of the Fe2+ release from Schiff base under acidic conditions (Figure 1D-E). The release of Fe2+ from the PAsc-PSFe polymer under acidic conditions was confirmed using the standard potassium ferricyanide and potassium thiocyanate method (Figure S14).

Figure 1.

Characterization of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB. (A) EDS elemental mappings and corresponding spectra of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB. (B) TEM images and (C) Size distribution of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB at pH 7.4 and pH 5.0. (D) T1-weighted MRI of the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was recorded using MR scanner at different Fe concentrations (0 ~ 0.5 mM) and pH values (7.4, 6.5, 5.5, and 5.0). (E) Corresponding r1 value. (F) Absorption and fluorescence spectra of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (50 μg/mL, pH 5.0) in PBS at indicated varied concentrations of H2O2 (0 ~ 10 eq).

The synchronous release of Cy7QB was also confirmed by UV-vis absorption and emission spectra, consistent with the sensing performance with the free Cy7QB (Figure 1F). Due to the significant absorption responsiveness of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB towards H2O2, the fluorescence intensity gradually increased after the addition of H2O2 (Figure S15). The PA signal of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB also showed a positive linear correlation with H2O2 concentration (Figure S16). Altogether, our results indicated that the nanomicelles PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB could disassemble in an acidic microenvironment to release Fe2+, AscH-, and the molecular adjuvant Cy7QB, accompanied by remarkable enhancement of MR signals and recovery of the H2O2-sensitive fluorescent and photoacoustic signals, facilitating the multimodal imaging of the localized tumors.

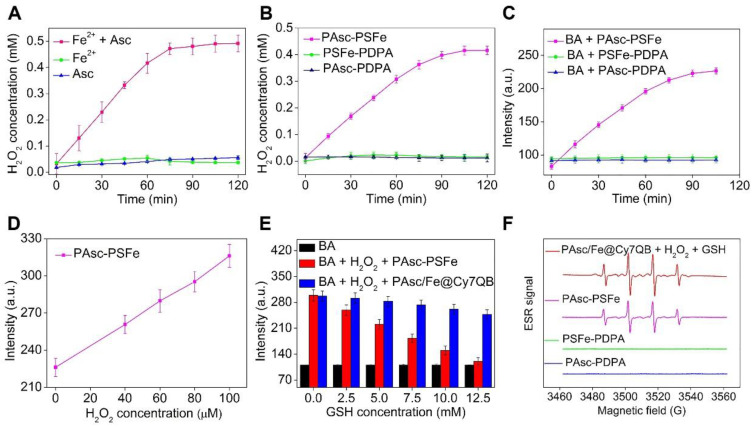

Generation of H2O2 and •OH in solution

After validation of the acid-triggered degradation of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, in situ production of H2O2 was investigated. We utilized TMB and HRP to quantify the H2O2 concentration by measuring the absorbance of oxidized TMB (Figure S17). H2O2 concentration reached up to 0.5 mM in the presence of free Fe2+ (0.16 mM) and ascorbate (0.8 mM) at pH 5.0 (Figure 2A), and the concentration further increased with the increase in ascorbate (Figure S18). However, H2O2 generation was negligible after treatment with ascorbate at both pH 7.4 and 5.0 (Figure S19). These results confirmed that the Fe2+ could catalyze the oxidation of ascorbate into Asc·- for in situ H2O2 production under acidic conditions 74, 79.

Figure 2.

Generation of H2O2 and •OH in solution. (A-B) Time-dependent H2O2 production by Fe2-mediated Fenton reaction in different solutions. Ascorbate (0.8 mM), Fe2+ (0.16 mM). (C) Time-dependent increase in fluorescence using BA as the fluorescence probe for the detection of •OH production. The emission of fluorescence by oxidized BA at 426 nm was used to determine the levels of •OH at pH 5.0. (D) Detection of •OH in samples treated at indicated H2O2 concentrations with polymer PAsc-PSFe. (E) Fluorescence spectra of BA by •OH generated by different concentrations of GSH-treated with PAsc-PSFe + H2O2 and PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB + H2O2 at pH 5.0. (F) ESR spectra of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB + 100 μM H2O2 + 10 mM GSH, PAsc-PSFe, PAsc-PDPA, and PSFe-PDPA.

We then investigated the possibility of using PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB to produce H2O2, and PAsc-PDPA without Schiff base-Fe2+ and PSFe-PDPA without ascorbate were chosen as controls to accurately quantify H2O2 levels. A similar trend was observed for PAsc-PSFe containing ascorbate and Schiff base-Fe2+, suggesting that the ascorbate in PAsc-PSFe could induce H2O2 generation in situ at pH 5.0 (Figure 2B, S20). Subsequently, •OH generation with Fe2+ and ascorbate and the depletion effect of GSH on •OH at pH 7.4 or 5.0 were investigated. We found that BA's fluorescence intensity gradually increased with the addition of ascorbate in the presence of Fe2+ at pH 5.0 within 2 h (Figure S21), indicating efficient generation of •OH. However, the levels of •OH remained almost unchanged after the same treatment at pH 7.4 (Figure S22). PAsc-PSFe was also found to efficiently produce •OH under acidic conditions (Figure 2C, S23). The addition of exogenous H2O2 could also boost •OH generation (Figure 2D, S24-25), indicating ability of PAsc-PSFe to produce •OH by utilizing both the produced and endogenous cellular H2O2. However, further investigations showed that BA's fluorescence intensity in PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB at pH 5.0 was 3-fold stronger than PAsc-PSFe in the presence of 10 mM GSH (Figure S26), ascribed to the removal of GSH by PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB via the in situ generated quinone methide (Figure S27). Overall, acid-degradable PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, integrating self-catalytic Fenton reactions and the ability to eliminate GSH, could provide a cascade burst of •OH production in the tumor microenvironment for highly efficient and precise eradication of solid tumors (Figure 2E). Furthermore, electron spin resonance (ESR) was utilized to monitor the •OH signals by employing 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) as the spin-trapping agent. The results indicated that •OH was effectively generated by PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB that integrated self-catalytic Fenton reaction and the ability to eliminate GSH under acidic conditions (Figure 2F).

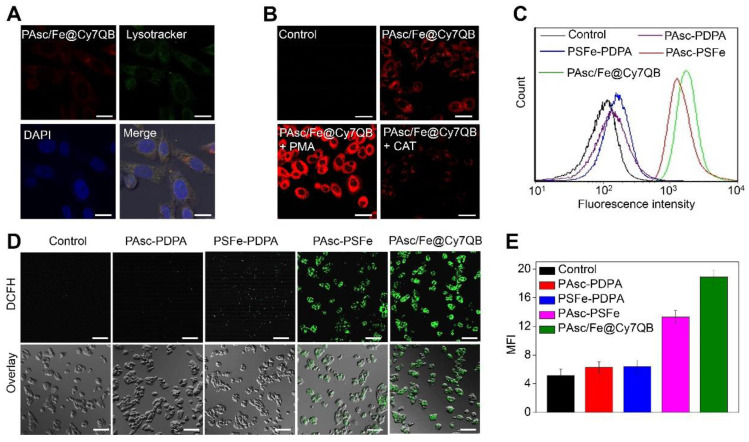

In vitro H2O2-selective bioimaging and intracellular ROS levels

Given the highly effective in vitro generation of •OH by PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB under acidic conditions, we explored their responsiveness to H2O2 and anticancer effects in tumor cells. The fluorescence intensity of HepG2 incubated with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB increased significantly over time and reached a maximum at 2 h (Figure S28). The appearance of merged yellow dots from green (Lysotracker) and red (PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB) pixels showed that PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB exhibited good colocalization with lysosomes (Figure 3A). The acidic environment of endosomes/lysosomes could induce decomposition and destabilization of the responsive nanomicelles 80, which might explain the disintegration of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB and release of Fe2+, AscH- and the adjuvant Cy7QB in a relatively acidic microenvironment. Subsequently, upregulation of H2O2 in HepG2 cells following treatment with PMA (1 mg/mL) led to brighter fluorescence imaging. In contrast, H2O2 depletion following treatment with CAT (10 U/mL) resulted in a decrease in fluorescence intensity, beneficial for monitoring the disintegration and visualizing movement of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (Figure 3B, S29).

Figure 3.

In vitro H2O2-selective bioimaging and intracellular ROS levels. (A) CLSM images showing the intracellular distribution of the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB. (B) CLSM images of HepG2 cells incubated with 50 μg/mL PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB in the presence or absence of PMA or CAT. (C) Flow cytometry analysis and (D) CLSM images of HepG2 cells after treatment with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, PAsc-PSFe, PSFe-PDPA, and PAsc-PDPA for 2 h and subsequent staining with the ROS fluorescence probe DCFH-DA. (E) Corresponding mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values in (D). All images have a scale bar of 20 μm.

To understand the intracellular H2O2-catalyzed toxicity of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, ROS levels were further monitored by the probe DCFH-DA 81-83, which can emit green fluorescence after oxidation by ROS. As shown in Figure 3C, flow cytometric analysis verified that •OH generation in the PAsc-PSFe group was higher than the control group, which was ascribed to the self-catalytic Fenton reaction. However, •OH generation in the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB group was higher than the control group due to the synergistic effect of self-catalytic Fenton reaction and GSH depletion. Similar results were observed by CLSM analysis, further verifying a significant H2O2-catalyzed •OH burst cascade by PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB treatment (Figure 3D-E). GSH quantification in HepG2 cells treated with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB confirmed that nanomicelles could decrease the cellular GSH concentration (Figure S30), consistent with the in vitro findings. Also, H2O2 elimination by CAT prevented PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB-induced H2O2 mediated boronate oxidation to generate quinone methide and recover GSH levels in the cells. Thus, PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB were effectively taken up by tumor cells, producing •OH with high efficiency in the acidic tumor microenvironment to induce significant localized toxicity and exert excellent anticancer effects.

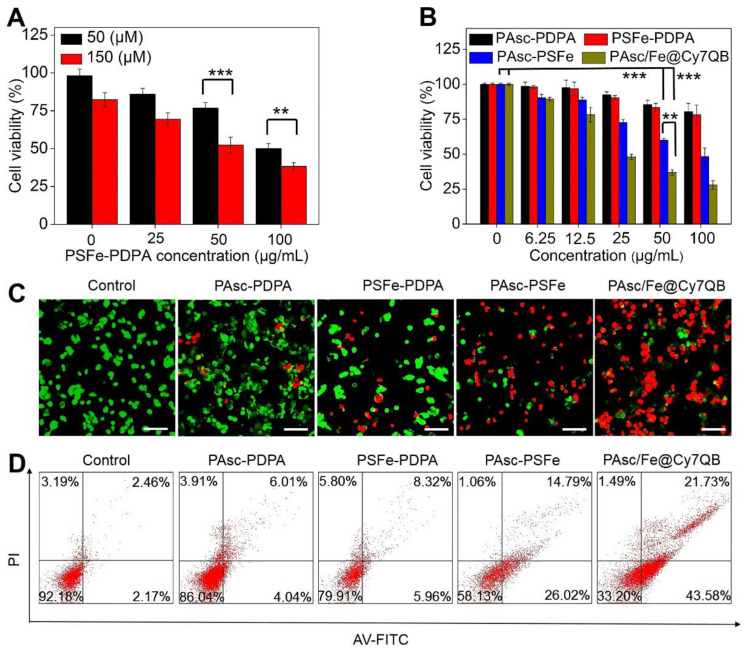

Assessment of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB-induced cytotoxicity

Encouraged by the high catalytic performance of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, we assessed the cell viability by using the standard MTT cell assay. First, treatment of HepG2 cells with PSFe-PDPA at the same concentration of H2O2 resulted in significant cytotoxicity compared to cells without PSFe-PDPA treatment, demonstrating the stronger cytotoxicity of •OH compared to H2O2 (Figure 4A). The cytotoxicity of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was then explored using PAsc-PSFe, PAsc-P DPA and PSFe-PDPA groups as controls. As shown in Figure 4B, the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB group exerted significant concentration-dependent cytotoxicity, and the percentage of cell survival following treatment with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (26%) was lower than that of PAsc-PDPA (84%) with insufficient intracellular ROS and PAsc-PSFe (49%) with only self-catalytic Fenton reaction. In particular, PSFe-PDPA caused only a slight reduction in cell viability due to the insufficient intracellular H2O2 levels to produce •OH, which was further confirmed by the negligible cytotoxicity of pure Fe2+ (Figure S31). The combination index (CI) value of PAsc-PSFe, and PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was determined to be 0.51 and 0.47, respectively (Table S1), suggesting that the combined effect led to a stronger inhibition compared with the single composition 84. The high cytotoxicity of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB was also verified by Calcein AM and propidium iodide (PI) double-staining of liver cells; live cells (green) and dead cells (red) (Figure 4C). Flow cytometric analysis with Annexin V-FITC together with PI as markers provided similar results (Figure 4D). These results confirmed the •OH burst cascade by the self-catalytic Fenton reaction and GSH depletion.

Figure 4.

Assessment of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB-induced cytotoxicity. (A) Cytotoxicity of PSFe-PDPA in the presence of H2O2 (50 μM or 150 μM). (B) Cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells at various concentrations. (C) The live/dead assay and (D) Annexin V/PI assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity after incubation with PBS, PAsc-PDPA, PSFe-PDPA, PAsc-PSFe, or PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (50 µg/mL). All images have a scale bar of 20 μm. P values were calculated by two-tailed Student's t-test (***p < 0.001, or *p < 0.05).

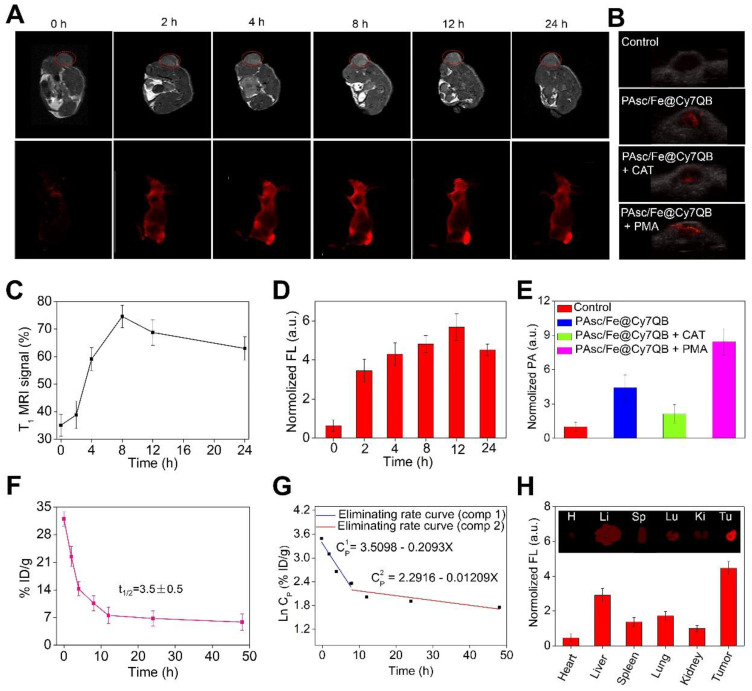

In vivo multimodal imaging

Multimodal imaging provides the advantages of various imaging methods, such as high-resolution MRI, highly sensitive FLI and high-depth PAI, to facilitate the screening of early micro-tumors and guide precision therapy 85-89. The excellent magnetic, fluorescence, and photoacoustic properties of the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB in vitro prompted us to apply multimodal imaging-guided tumor-targeted in vivo CDT. After intravenous (i.v.) injection of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (50 μg/mL, 100 μL) into the HepG2 tumor-bearing mouse, MRI of the tumor region was acquired over time and recorded at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h post-injection (Figure 5A). The T1-weighted MRI signal was substantially increased from 30% to 75% within 24 h (Figure 5C), confirming efficient tumor accumulation of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB. Next, NIR fluorescent imaging of HepG2 tumor-bearing mice following PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB injection was performed, as depicted in Figure 5A. The fluorescence in the tumor region was detectable at 2 h post-injection, and its intensity gradually increased reaching a maximum at 12 h post-injection (Figure 5D). After 12 h of i.v injection of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, the HepG2 tumor-bearing mice pretreated with saline, CAT, or PMA were monitored by PAI (Figure 5B, E). These results implied that H2O2 could selectively unlock imaging features of the nanomicelles in vivo.

Figure 5.

In vivo multimodal imaging. (A) In vivo MRI/FLI at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h i. v. post-injection of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (50 μg/mL, 100 μL). (B) PAI of each group at 12 h after PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB injection via the tail vein: PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB only; PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB + CAT; PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB + PMA. (C) Analysis of the tumor region by the MRI signals in (A). (D) Fluorescence intensity in mice after PAA/Fe@Cy7QB injection. (E) Analysis of the tumor region by the PAI signals in (B). (F) Blood level curve of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB in mice fluorescence measurement of Cy7 in blood at different time points post i.v. injection. (G) Eliminating rate curve of injected PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB in blood circulation according to the Ln (concentration)-time relationship. The two stage eliminating rates of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB are shown. (H) FLI of major organs and tumors of mice after 24 h i.v. injection PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB.

The biodistribution in the main organs and in blood circulation was also measured to determine the in vivo behavior of the nanomicelles. The results showed that the blood level of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB gradually decreased over time but remained at a relatively effective concentration even at 24 h post-injection (Figure 5F). The eliminating rate constants 38, 90 of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB were calculated to be -0.2093 μg/mL per hour in the first stage and decreased to -0.01209 μg/mL per hour in the second stage with a shifting time interval of 6.18 h (Figure 5G). The tumor as well as all main organs from HepG2 tumor-bearing mice treated with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB were harvested after 24 h (Figure 5H). FLI indicated that the theranostic PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB specifically accumulated in the tumor region via the multi-targeting effect of EPR and subsequent pH-triggered decomposition and H2O2-driven deboronation reaction. The rapid decrease in PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB levels within 72 h in various organs after post-injection further revealed its desirable good biodegradation (Figure S32).

Although the relatively high PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB accumulation was found in the liver due to the reticuloendothelial system (RES) 91, the tumor selectivity of the nanomicelles was significantly dominant and could be attributed to the multi-targeting effect. The feces and urine were also collected to study the possible clearance pathway of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (Figure S33). High levels of Cy7 were detected in both urine and feces, indicating good metabolic characteristics of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB that could be excreted through both the kidneys and gastrointestinal system. Very low levels of Cy7-species remained in the mouse body after 120 h. The results were consistent with the relatively high accumulation levels of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB in the liver, spleen and kidney. Taken together, these results indicated that PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB provided outstanding MR/FL/PA multimodal imaging for defining the tumor region and precise guidance for subsequent CDT.

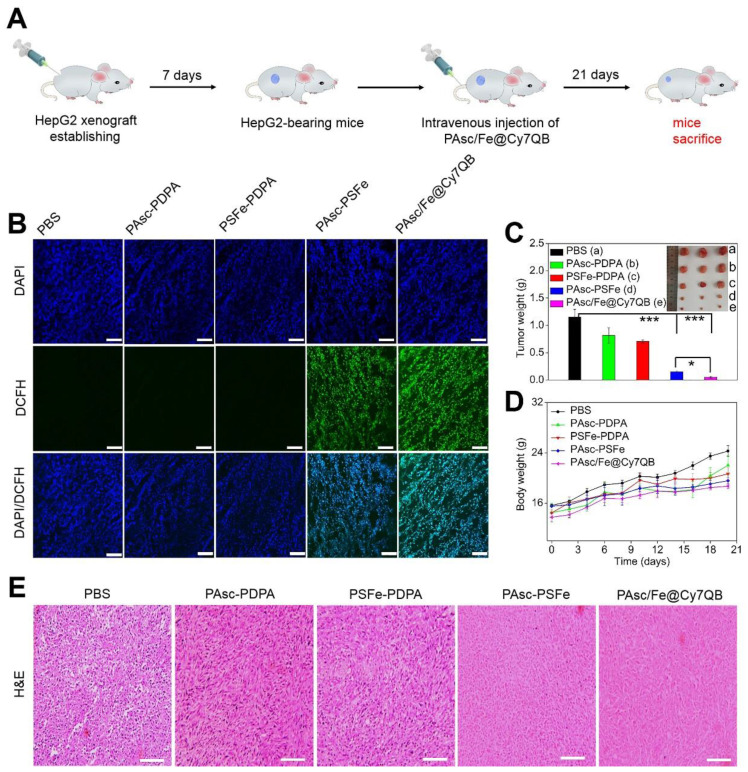

In vivo tumor therapeutic effects of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB

Based on the H2O2-catalytic substantial production of •OH and remarkable tumor-selective imaging in vitro and in vivo, PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB were injected into HepG2-bearing mice to investigate its anticancer efficacy (Figure 6A). The ROS levels in tumor tissues of treated mice were detected using the DCFH-DA probe. As shown in Figure 6B, bright green fluorescence was observed in the group that was injected with PAsc-PSFe due to the self-catalytic Fenton reaction. However, the group treated with PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB presented brighter imaging due to the combination of self-catalytic Fenton reaction and GSH elimination. To verify the therapeutic efficacy of the nanomicelles, mice bearing HepG2 tumors with initial volumes of 100-150 mm3 were chosen and randomly divided into five groups (n = 3 per group). One group was injected with saline and used as a control and the other four groups received PAsc-PDPA, PSFe-PDPA, PAsc-PSFe, or PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB i.v. injections and were then subjected to the indicated treatments. Mice in control, PAsc-PDPA and PSFe-PDPA groups exhibited rapid tumor growth, indicating that these agents had almost no therapeutic effect. The PAsc-PSFe group inhibited tumor growth due to the self-catalytic Fenton reaction, whereas the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB group exhibited the best tumor suppression effect, demonstrating the efficient and superior anticancer effect of the micelles (Figure 6C, S34). H&E staining was subsequently performed to evaluate the treatment effect, and the results demonstrated more necrosis and karyolysis in the PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB group (Figure 6E). No obvious loss in body weight was recorded in any of the experimental groups (Figure 6D), and the hemolysis test reflected the biosafety of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB even at high concentrations (Figure S35). H&E images of major organs in all treated groups revealed no abnormality or organ toxicity compared to the control group, indicating barely any side effects and good biocompatibility of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB (Figure S36). Therefore, the high biodegradability and biocompatibility with the efficient tumor-targeted pharmacological effects suggested great potential of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB for precise cancer therapy.

Figure 6.

In vivo antitumor efficacy against HepG2 tumors of intravenous injection of PBS, PAsc-PDPA, PSFe-PDPA, PAsc-PSFe, or PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB. (A) Schematic illustration of the establishment of the HepG2 tumor xenograft model and treatment process. (B) DCFH-staining of tumor tissues from different groups at 24 h post-injection. (C) Typical images and the relative tumor weight of HepG2 tumor-bearing mice in various groups after 21 days of treatment. (D) Bodyweight changes of HepG2 tumor-bearing mice in various groups after 21 days of treatment. (E) H&E-stained slices of tumor tissues from different groups collected after 21 days of treatment. Mean ± s.d, n = 3. Scale bar represents 20 μm. P values were calculated by two-tailed Student's t-test (***p < 0.001, or *p < 0.05).

Conclusion

We have successfully developed a novel in situ activatable PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB nanomicelles for the tumor-targeted chemodynamic theranostics to achieve effective eradication of localized solid tumors. The biodegradable nanomicelles featured optimized nanoparticle size, PEG surface, and high stability under physiological conditions and could persist for prolonged periods of times in the blood circulation to improve tumor accumulation. The tumor microenvironmental acidosis facilitated the selective disassembly of PAsc/Fe@Cy7QB, inducing the release of Fe2+, AscH- and the adjuvant Cy7QB. The released pharmaceutical components synergized to achieve the tumor-cell recognition with multimodal imaging as well as the burst cascade of •OH to selectively kill tumor cells. Our study provides a new paradigm for Fenton metal-based chemodynamic theranostics, demonstrating great potential for accurate tumor therapies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and table, experimental section.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21771065); the Guangdong Special Support Program (2017TQ04R138), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (2019050001); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (2019A1515012021), the Pearl River Nova Program of Guangzhou (201806010189), Guangdong Province, China.

Abbreviations

- Asc

ascorbate (ascorbic acid)

- AscH-

ascorbate monoanion

- Asc·-

ascorbate radical

- Cy7QB

Cy7 dye incorporated with quinone methide-generating boronate ester

- PDPA

poly(2-(diisorpropylamino) ethyl methacrylate)

- PAsc-PSFe

polymerized ascorbate, Schiff base-Fe2+ complex and 2-(diisorpropylamino) ethyl methacrylate

- PAsc-PDPA

polymerized ascorbate and 2-(diisorpropylamino) ethyl methacrylate

- PSFe-PDPA

polymerized Schiff base-Fe2+ complex and 2-(diisorpropylamino) ethyl methacrylate

- CDT

chemodynamic therapy

- •OH

hydroxyl radicals

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- GSH

glutathione

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- EDS

energy dispersive spectrometer

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- FLI

fluorescence imaging

- PAI

photoacoustic imaging

- ESR

electron spin resonance

- BA

benzoic acid

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- TMB

3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- PMA

phorbol 1,2-myristate 1,3-acetate

- CAT

Catalase

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- CLSM

confocal fluorescence microscope images

- DCFH-DA

2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- FITC

4-nitrophthalonitrile fluorescein isothio-cyanate

- PI

propidium iodide

- RES

reticuloendothelial system

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HepG2

human hepatoma cells

References

- 1.Liu F, Lin L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Sheng S, Xu C. et al. A tumor-microenvironment-activated nanozyme-mediated theranostic nanoreactor for imaging-guided combined tumor therapy. Adv Mater. 2019;31:1902885. doi: 10.1002/adma.201902885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu J, Williams GR, Niu S, Gao F, Tang R, Zhu LM. A multifunctional biodegradable nanocomposite for cancer theranostics. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2019;6:1802001. doi: 10.1002/advs.201802001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan N, Wang X, Lin L, Song T, Sun P, Tian H. et al. Gold nanorods electrostatically binding nucleic acid probe for in vivo microrna amplified detection and photoacoustic imaging-guided photothermal therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28:1800490. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang D, Dai Y, Liu J, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Li C. et al. Ultra-small BaGdF5-based upconversion nanoparticles as drug carriers and multimodal imaging probes. Biomaterials. 2014;35:2011–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Z, Xu K, Fu C, Liu H, Lei M, Bao J. et al. Interfacial engineered gadolinium oxide nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging guided microenvironment-mediated synergetic chemodynamic/photothermal therapy. Biomaterials. 2019;219:119379. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhen X, Zhang J, Huang J, Xie C, Miao Q, Pu K. Macrotheranostic probe with disease-activated near-infrared fluorescence, photoacoustic, and photothermal signals for imaging-guided therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57:7804–8. doi: 10.1002/anie.201803321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni J, Li Y, Yue W, Liu B, Li K, Nanoparticle-based cell trackers for biomedical applications. Theranostics. 2020; 10: 1923-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Pei Q, Hu X, Zheng X, Liu S, Li Y, Jing X, Xie Z. Light-activatable red blood cell membrane-camouflaged dimeric prodrug nanoparticles for synergistic photodynamic/chemotherapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12:1630–41. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song XR, Li SH, Guo H, You W, Tu D, Li J. et al. Enhancing antitumor efficacy by simultaneous ATP-responsive chemodrug release and cancer cell sensitization based on a smart nanoagent. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2018;5:1801201. doi: 10.1002/advs.201801201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian Q, Li Y, Jiang S, An L, Lin J, Wu H. et al. Tumor pH-responsive albumin/polyaniline assemblies for amplified photoacoustic imaging and augmented photothermal therapy. Small. 2019;15:e1902926. doi: 10.1002/smll.201902926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao S, Yu X, Qian Y, Chen W, Shen J. Multifunctional magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: an advanced platform for cancer theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;10:6278–309. doi: 10.7150/thno.42564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogdanov AA Jr, Gupta S, Koshkina N, Corr SJ, Zhang S. et al. Gold nanoparticles stabilized with MPEG-grafted poly(l-lysine): in vitro and in vivo evaluation of a potential theranostic agent. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26:39–50. doi: 10.1021/bc5005087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi KY, Han HS, Lee ES, Shin JM, Almquist BD, Lee DS. et al. Hyaluronic acid-based activatable nanomaterials for stimuli-responsive imaging and therapeutics: beyond CD44-mediated drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2019;31:e1803549. doi: 10.1002/adma.201803549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du L, Qin H, Ma T, Zhang T, Xing D. In vivo imaging-guided photothermal/photoacoustic synergistic therapy with bioorthogonal metabolic glycoengineering-activated tumor targeting nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2017;11:8930–43. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b03226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang P, Rong P, Lin J, Li W, Yan X, Zhang MG. et al. Triphase interface synthesis of plasmonic gold bellflowers as near-infrared light mediated acoustic and thermal theranostics. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:8307–13. doi: 10.1021/ja503115n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang B, Fang L, Wu K, Yan X, Fan K. Ferritins as natural and artificial nanozymes for theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;10:687–706. doi: 10.7150/thno.39827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyu Y, Zeng J, Jiang Y, Zhen X, Wang T, Qiu S. et al. Enhancing both biodegradability and efficacy of semiconducting polymer nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12:1801–10. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi H, Sun Y, Yan R, Liu S, Zhu L, Liu S. et al. Magnetic semiconductor Gd-doping CuS nanoparticles as activatable nanoprobes for bimodal imaging and targeted photothermal therapy of gastric tumors. Nano Lett. 2019;19:937–47. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b04179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng J, Zeng Q, Zhang RJ, Xing D, Zhang T. Dynamic-reversible photoacoustic probe for continuous ratiometric sensing and imaging of redox status in vivo. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:19226–30. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Q, Bi H, Wang Z, Li C, Wang C, Xu J. et al. O2-generating metal-organic framework-based hydrophobic photosensitizer delivery system for enhanced photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:36347–58. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b11607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang C, Yan L, Wang X, Dong X, Zhou R, Gu Z. et al. Tumor microenvironment-responsive Cu2(OH)PO4 nanocrystals for selective and controllable radiosentization via the x-ray-triggered fenton-like reaction. Nano Lett. 2019;19:1749–57. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b04763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen D, Tang Y, Zhu J, Zhang J, Song X, Wang W. et al. Photothermal-pH-hypoxia responsive multifunctional nanoplatform for cancer photo-chemo therapy with negligible skin phototoxicity. Biomaterials. 2019;221:119422. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao S, Lin H, Zhang H, Yao H, Chen Y, Shi J. Nanocatalytic tumor therapy by biomimetic dual inorganic nanozyme-catalyzed cascade reaction. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2019;6:1801733. doi: 10.1002/advs.201801733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin T, Ma R, Yin Y, Miao X, Chen S, Fan K. et al. Catalytic inactivation of influenza virus by iron oxide nanozyme. Theranostics. 2019;9:6920–35. doi: 10.7150/thno.35826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi S, Wu S, Shen Y, Zhang S, Xiao Y, He X. et al. Iron oxide nanozyme suppresses intracellular salmonella enteritidis growth and alleviates infection in vivo. Theranostics. 2018;8:6149–62. doi: 10.7150/thno.29303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Z, Song J, Tian R, Yang Z, Yu G, Lin L. et al. Activatable singlet oxygen generation from lipid hydroperoxide nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:6492–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201701181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Lu Y, Jiang C, Zhu Y, Yang X, Hu X. et al. Actively targeted deep tissue imaging and photothermal-chemo therapy of breast cancer by antibody-functionalized drug-loaded x-ray-responsive bismuth Sulfide@Mesoporous silica core-shell nanoparticles. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28:1704623. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201704623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Q, He F, Bi H, Wang Z, Sun C, Li C. et al. An intelligent nanoplatform for simultaneously controlled chemo-, photothermal, and photodynamic therapies mediated by a single NIR light. Chem Eng J. 2019;362:679–91. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao C, Wang W, Wang P, Zhao M, Li X, Zhang F. Near-infrared upconversion mesoporous cerium oxide hollow biophotocatalyst for concurrent pH-/H2O2-responsive O2-evolving synergetic cancer therapy. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1704833. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao L, Fan K, Yan X, Iron oxide nanozyme. a multifunctional enzyme mimetic for biomedical applications. Theranostics. 2017;7:3207–27. doi: 10.7150/thno.19738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han X, Xu Y, Li Y, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Min H. et al. An extendable star-like nanoplatform for functional and anatomical imaging-guided photothermal oncotherapy. ACS Nano. 2019;13:4379–91. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b09607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma B, Wang S, Liu F, Zhang S, Duan J, Li Z. et al. Self-assembled copper-amino acid nanoparticles for in situ glutathione "and" H2O2 sequentially triggered chemodynamic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:849–57. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian X, Zhang J, Gu Z, Chen Y. Nanocatalysts-augmented Fenton chemical reaction for nanocatalytic tumor therapy. Biomaterials. 2019;211:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu W, Yu L, Jiang Q, Huo M, Lin H, Wang L. et al. Enhanced tumor-specific disulfiram chemotherapy by in situ Cu(2+) chelation-initiated nontoxicity-to-toxicity transition. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:11531–9. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b03503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu J, Zhao F, Gao W, Yang X, Ju Y, Zhao L. et al. Magnetic reactive oxygen species nanoreactor for switchable magnetic resonance imaging guided cancer therapy based on pH-sensitive Fe5C2@Fe3O4 nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2019;13:10002–14. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b01740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang F, Li F, Lu GH, Nie W, Zhang L, Lv Y. et al. Engineering magnetosomes for ferroptosis/immunomodulation synergism in cancer. ACS Nano. 2019;13:5662–73. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b00892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang C, Bu W, Ni D, Zhang S, Li Q, Yao Z. et al. Synthesis of iron nanometallic glasses and their application in cancer therapy by a localized fenton reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:2101–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng L, Xie R, Wang C, Gai S, He F, Yang D. et al. Magnetic targeting, tumor microenvironment-responsive intelligent nanocatalysts for enhanced tumor ablation. ACS Nano. 2018;12:11000–12. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b05042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ji X, Kang Y, Ouyang J, Chen Y, Artzi D, Zeng X. et al. Synthesis of ultrathin biotite nanosheets as an intelligent theranostic platform for combination cancer therapy. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2019;6:1901211. doi: 10.1002/advs.201901211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin LS, Huang T, Song J, Ou XY, Wang Z, Deng H. et al. Synthesis of copper peroxide nanodots for H2O2 self-supplying chemodynamic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:9937–45. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b03457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang T, Zhang H, Liu H, Yuan Q, Ren F, Han Y. et al. Boosting H2O2-guided chemodynamic therapy of cancer by enhancing reaction kinetics through versatile biomimetic fenton nanocatalysts and the second near-infrared light irradiation. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;30:1906128. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding B, Shao S, Jiang F, Dang P, Sun C, Huang S. et al. MnO2-disguised upconversion hybrid nanocomposite: an ideal architecture for tumor microenvironment-triggered UCL/MR bioimaging and enhanced chemodynamic therapy. Chem Mater. 2019;31:2651–60. [Google Scholar]

- 43.He T, Qin X, Jiang C, Jiang D, Lei S, Lin J. et al. Tumor pH-responsive metastable-phase manganese sulfide nanotheranostics for traceable hydrogen sulfide gas therapy primed chemodynamic therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10:2453–62. doi: 10.7150/thno.42981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tian Q, An L, Tian Q, Lin J, Yang S. Ellagic acid-Fe@BSA nanoparticles for endogenous H2S accelerated Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion and photothermal synergistically enhanced chemodynamic therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10:4101–15. doi: 10.7150/thno.41882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan JX, Peng MY, Wang H, Zheng HR, Liu ZL, Li CX. et al. Engineered bacterial bioreactor for tumor therapy via fenton-like reaction with localized H2O2 generation. Adv Mater. 2019;31:e1808278. doi: 10.1002/adma.201808278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao J, Zhang G, Xu R, Chen H, Wang H, Tian G. et al. A pH-responsive platform combining chemodynamic therapy with limotherapy for simultaneous bioimaging and synergistic cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2019;216:119254. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ke W, Li J, Mohammed F, Wang Y, Tou K, Liu X. et al. Therapeutic polymersome nanoreactors with tumor-specific activable cascade reactions for cooperative cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2019;13:2357–69. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b09082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang S, Wang Z, Yu G, Zhou Z, Jacobson O, Liu Y. et al. Tumor-specific drug release and reactive oxygen species generation for cancer chemo/chemodynamic combination therapy. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2019;6:1801986. doi: 10.1002/advs.201801986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L, Wan SS, Li CX, Xu L, Cheng H, Zhang XZ. An adenosine triphosphate-responsive autocatalytic fenton nanoparticle for tumor ablation with self-supplied H2O2 and acceleration of Fe (III)/Fe (II) conversion. Nano Lett. 2018;18:7609–18. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gong F, Cheng L, Yang N, Jin Q, Tian L, Wang M. et al. Bimetallic oxide MnMoOX nanorods for in vivo photoacoustic imaging of GSH and tumor-specific photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 2018;18:6037–44. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b02933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu Y, Lv T, Ma Y, Xu J, Zhang Y, Hou Y. et al. Nanoscale coordination polymers for synergistic NO and chemodynamic therapy of liver cancer. Nano Lett. 2019;19:2731–8. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin LS, Song J, Song L, Ke K, Liu Y, Zhou Z. et al. Simultaneous fenton-like ion delivery and glutathione depletion by MnO2-based nanoagent to enhance chemodynamic therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57:4902–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201712027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wan SS, Cheng Q, Zeng X, Zhang XZ. A Mn (III)-sealed metal-organic framework nanosystem for redox-unlocked tumor theranostics. ACS Nano. 2019;13:6561–71. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b00300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang A, Pan S, Zhang Y, Chang J, Cheng J, Huang Z. et al. Carbon-gold hybrid nanoprobes for real-time imaging, photothermal/photodynamic and nanozyme oxidative therapy. Theranostics. 2019;9:3443–58. doi: 10.7150/thno.33266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao J, Gao W, Cai X, Xu J, Zou D, Li Z. et al. Nanozyme-mediated catalytic nanotherapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Theranostics. 2019;9:2843–55. doi: 10.7150/thno.33727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao Z, Zhang L, Liang K, Cheong S, Boyer C, Gooding JJ. et al. Biodegradable 2D Fe-Al hydroxide for nanocatalytic tumor-dynamic therapy with tumor specificity. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2018;5:1801155. doi: 10.1002/advs.201801155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang M, Wang M, Wang M, Shu M, Ding B, Li C. et al. A multifunctional cascade bioreactor based on hollow-structured Cu2MoS4 for synergetic cancer chemo-dynamic therapy/starvation therapy/phototherapy/immunotherapy with remarkably enhanced efficacy. Adv Mater. 2019;31:e1905271. doi: 10.1002/adma.201905271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai Y, Yang Z, Cheng S, Wang Z, Zhang R, Zhu G. et al. Toxic reactive oxygen species enhanced synergistic combination therapy by self-assembled metal-phenolic network nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1704877. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Q, Espey MG, Sun AY, Lee JH, Krishna MC, Shacter E. et al. Ascorbate in pharmacologic concentrations selectively generates ascorbate radical and hydrogen peroxide in extracellular fluid in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8749–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lü W, Sun C, Lu Q, Li N, Wu D, Yao Y. et al. Synthesis and photoactivity of pH-responsive amphiphilic block polymer photosensitizer bonded zinc phthalocyanine. Sci China Chem. 2012;55:1108–14. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang P, Liu J, Wang W, Li C, Zhou J, Wang X. et al. Zwitterionic nanoparticles constructed with well-defined reduction-responsive shell and pH-sensitive core for "spatiotemporally pinpointed" drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:14631–43. doi: 10.1021/am503974y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yuan L, Lin W, Zhao S, Gao W, Chen B, He L. A unique approach to development of near-infrared fluorescent sensors for in vivo imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13510–23. doi: 10.1021/ja305802v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischer D, Li YX, Ahlemeyer B, Krieglstein J, Kissel T. In vitro cytotoxicity testing of polycations: influence of polymer structure on cell viability and hemolysis. Biomaterials. 2003;24:1121–31. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jeong H, Hwang J, Lee H, Hammond PT, Choi J, Hong J. In vitro blood cell viability profiling of polymers used in molecular assembly. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10169-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoshida Y, Miyata T, Matsumoto M, Shirotani-Ikejima H, Uchida Y, Ohyama Y. et al. A novel quantitative hemolytic assay coupled with restriction fragment length polymorphisms analysis enabled early diagnosis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and identified unique predisposing mutations in Japan. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu B, Wang W, Fan J, Long Y, Xiao F, Daniyal M. et al. RBC membrane camouflaged prussian blue nanoparticles for gamabutolin loading and combined chemo/photothermal therapy of breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2019;217:119301. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buettner GR, Jurkiewicz BA. Catalytic metals, ascorbate and free radicals: combinations to avoid. Radiat Res. 1996;145:532–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barry HW. Vitamin C: poison, prophylactic or panacea? Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01418-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davies MB. Reaction of L-ascorbic acid with transition metal complexes. Polyhedron. 1992;11:285–321. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khan MM, Martell AE. Metal ion and metal chelate catalyzed oxidation of ascorbic acid by molecular oxygen. II. Cupric and ferric chelate catalyzed oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:7104–11. doi: 10.1021/ja01002a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frei B. and Lawson S, Vitamin C and cancer revisited. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11037–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806433105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Udenfriend S, Clark CT, Axelrod J, Brodie BB. Ascorbic acid in aromatic hydroxylation. I. A model system for aromatic hydroxylation. J Biol Chem. 1954;208:731–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Du J, Cullen J J, Buettner G R. Ascorbic acid: chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826:443–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou P, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liang J, Liu B. et al. Generation of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical resulting from oxygen-dependent oxidation of l-ascorbic acid via copper redox-catalyzed reactions. RSC Adv. 2016;6:38541–7. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zeng Q, Zhang R, Zhang T, Xing D. H2O2-responsive biodegradable nanomedicine for cancer-selective dual-modal imaging guided precise photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2019;207:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fluksman A, Benny O. A robust method for critical micelle concentration determination using coumarin-6 as a fluorescent probe. Anal Methods. 2019;11:3810–8. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dom´ınguez A, Fern´andez A, Gonz´alez N, Iglesias E, Montenegro L. Determination of critical micelle concentration of some surfactants by three techniques. J Chem Educ. 1997;74:1227–31. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Allinen M, Beroukhim R, Cai L, Brennan C, Lahti-Domenici J, Huang H. et al. Molecular characterization of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaushik N, Uddin N, Sim GB, Hong YJ, Baik KY, Kim CH. et al. Responses of solid tumor cells in DMEM to reactive oxygen species generated by non-thermal plasma and chemically induced ros systems. Sci Rep. 2015;5:08587. doi: 10.1038/srep08587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sun H, Zhang Y, Zhong Z. Reduction-sensitive polymeric nanomedicine: an emerging multifunctional platform for targeted cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;132:16–32. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lebel CP, Ischiropoulos H, Bondy SC. Evaluation of the probe 2',7' dichlorofluorescin as an indicator of reactive oxygen species formation and oxidative stress. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:227–31. doi: 10.1021/tx00026a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lin LS, Cong ZX, Li J, Ke KM, Guo SS, Yang HH. et al. Graphitic-phase C3N4 nanosheets as efficient photosensitizers and pH-responsive drug nanocarriers for cancer imaging and therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2:1031–7. doi: 10.1039/c3tb21479f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Ju E, Liu Z, Cao F, Chen Z. et al. Biomimetic nanoflowers by self-assembly of nanozymes to induce intracellular oxidative damage against hypoxic tumors. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3334. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05798-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang L, Jiang Y, Chen Y. Predicting drug combination index and simulating the network-regulation dynamics by mathematical modeling of drug-targeted EGFR-ERK signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40752. doi: 10.1038/srep40752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cheng Y, Tan X, Wang J, Wang Y, Song Y, You Q. et al. Polymer-based gadolinium oxide nanocomposites for FL/MR/PA imagined guided and photothermal/photodynamic combined anti-tumor therapy. J Control Release. 2018;277:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dai Y, Xiao H, Liu J, Yuan Q, Ma P, Yang D. et al. In vivo multimodality imaging and cancer therapy by near-infrared light-triggered trans-platinum pro-drug-conjugated upconverison nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:18920–9. doi: 10.1021/ja410028q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rong P, Yang K, Srivastan A, Kiesewetter DO, Yue X, Wang F. et al. Photosensitizer loaded nano-graphene for multimodality imaging guided tumor photodynamic therapy. Theranostics. 2014;4:229–39. doi: 10.7150/thno.8070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fan W, Yung B, Huang P, Chen X. Nanotechnology for multimodal synergistic cancer therapy. Chem Rev. 2017;117:13566–638. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao Y, Peng J, Li JJ, Huang L, Yang JY, Huang K. et al. Tumor-targeted and clearable human protein-based MRI nanoprobes. Nano Lett. 2017;17:4096–100. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b00828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huo M, Wang L, Chen Y, Shi J. Tumor-selective catalytic nanomedicine by nanocatalyst delivery. Nat Commun. 2017;8:357. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00424-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:615–27. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and table, experimental section.