Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to perform a seroprevalence survey on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) among Danish healthcare workers to identify high-risk groups.

Methods

All healthcare workers and administrative personnel at the 7 hospitals, prehospital services, and specialist practitioner clinics in the Central Denmark Region were invited to be tested by a commercial SARS-CoV-2 total antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co, Ltd, Beijing, China).

Results

A total of 25 950 participants were invited. Of these, 17 971 had samples available for SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing. After adjustment for assay sensitivity and specificity, the overall seroprevalence was 3.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5%–3.8%). The seroprevalence was higher in the western part of the region than in the eastern part (11.9% vs 1.2%; difference: 10.7 percentage points [95% CI, 9.5–12.2]). In the high-prevalence area, the emergency departments had the highest seroprevalence (29.7%), whereas departments without patients or with limited patient contact had the lowest seroprevalence (2.2%). Among the total 668 seropositive participants, 433 (64.8%) had previously been tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, and 50.0% had a positive reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result.

Conclusions

We found large differences in the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in staff working in the healthcare sector within a small geographical area of Denmark. Half of all seropositive staff had been tested positive by PCR prior to this survey. This study raises awareness of precautions that should be taken to avoid in-hospital transmission. Regular testing of healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 should be considered to identify areas with increased transmission.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, serology, healthcare workers, antibody

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 seroprevalence among healthcare workers in the Central Denmark Region showed large geographical differences (1%–12%). The risk of infection was associated with workplace, rather than location of residence.

During the year 2020, a pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has affected most countries in the world. However, the pandemic has not affected all countries or areas evenly. Hence, in relatively small areas, large differences in incidence rates have been observed [1]. To mitigate the effects of the pandemic, health authorities have introduced interventions—for example, the closing of schools, public institutions, prohibition of group gatherings, and even curfews. Healthcare workers may be at increased risk of infection [1, 2], but differences in seroprevalence according to professional status and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) are present [1, 3–5]. Prevention of infection in healthcare workers is important not only to reduce morbidity and mortality in this population, but also to avoid secondary transmission and maintain the capacity of the healthcare system.

The objective of this study was to perform a seroprevalence survey among all healthcare and administrative personnel at hospitals, prehospital services, and specialist practitioners in the Central Denmark Region to identify high-risk groups employed in the healthcare system, to find hotspots in the region, and to clarify whether the precautions for the healthcare professionals are sufficient. The survey was requested by the Danish Health Authority and the Danish Administrative Regions as a quality assurance project. Additionally, serological test results were compared with available results from previous SARS-CoV-2 RNA tests.

This study population is, to our knowledge, one of the largest in the world to date, demonstrating SARS-CoV-2 antibody screening among healthcare and administrative personnel. Indeed, the study enables risk differentiation between hospitals and specific professions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and Sampling

All healthcare and administrative personnel at hospitals, prehospital services, and specialist practitioners in the Central Denmark Region were invited by email to be tested for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Seven hospitals are located in the region including Denmark’s largest hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, where more than half of all hospital staff in the region is employed. Blood sampling was performed and organized by the departments of clinical biochemistry at the hospitals. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) blood samples were collected from 18 May until 19 June 2020. The blood samples were transported to Aarhus University Hospital for centrifugation, and plasma was pipetted within 36 hours and stored at −30°C until analysis.

Serological Testing

Undiluted EDTA plasma was tested for immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin M, and immunoglobulin A antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain using a commercial SARS-CoV-2 total antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co, Ltd, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (see the Supplementary Materials, Serological testing, for details). The assay had a sensitivity of 96.7% and a specificity of 99.5%, and no cross-reactivity was observed [6].

Experienced staff at the Department of Clinical Immunology and the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Aarhus University Hospital, performed the tests.

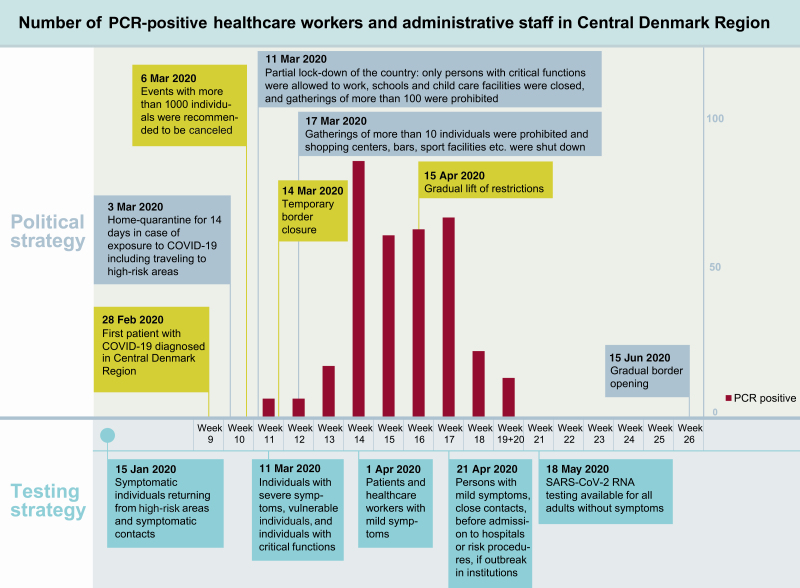

Polymerase Chain Reaction Testing

The SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in Denmark has been monitored nationally using reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)–based viral RNA detection. The testing strategy has been adjusted several times since the outbreak (Figure 1, epidemic timeline). Until now (data from 24 July 2020), 1 057 333 individuals in Denmark have been tested, 13 392 were detected positive, and 612 individuals with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have died [7].

Figure 1.

Epidemic timeline. Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Some of the healthcare and administrative personnel participating in the study had previously been tested with RT-PCR technique in case of relevant COVID-19 symptoms or relevant risk of exposure. Details about the PCR analysis are available in the Supplementary Materials, PCR testing.

Risk Groups and Hotspots

Healthcare and administrative personnel demographic information, job title, and workplace were obtained from the Central Denmark Region’s registration system of their employees.

Healthcare workers at the hospitals were grouped according to their geographical location: (1) Herning and Holstebro Regional Hospitals serving the western part of the region, Regional Hospital West Jutland (RHWJ); (2) Viborg and Silkeborg Regional Hospitals serving the central part, Regional Hospital Central Jutland (RHCJ); and (3) Randers Regional Hospital, Horsens Regional Hospital, and Aarhus University Hospital servicing the eastern part (East). Psychiatry and social services, pharmacies, information technology (IT) services, and administrative staff were grouped transregionally.

The seroprevalence among blood donors from the Central Denmark Region was also assessed. A total of 360 anonymized plasma samples from late June 2020 (180 from the western part and 180 from the eastern part of the region) were analyzed.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed in Stata/MP 16.1, RStudio 1.2, and R 3.6.0 software. Results were reported as percentages and percentage point (pp) differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Rogan-Gladen estimator was used to estimate the true prevalence based on the estimates of the sensitivity and the specificity. To address both the population uncertainty and the uncertainties of the sensitivity and the specificity, percentile bootstrapping was used to make CIs, sampling the test results, sensitivity, and specificity independently 108 times each. For comparing 2 populations, the same methods were applied to obtain a set of 108 samples of the estimated true prevalence for each population based on the same set of 108 sensitivity and specificity estimates. The difference was assessed using a 2-sided P value, that is, . Predictors of risk were also analyzed by multivariable logistic regression analysis and presented as odds ratios (ORs) with CIs.

Ethical Considerations

This study is approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (1-16-02-207-20) and by the Central Denmark Region. The regional scientific ethics committee of the Central Denmark Region concluded that this study did not require a scientific ethical approval (request number 127 on reference number 1-10-72-1-20).

The SARS-CoV-2 antibody screening was performed at the request of the Danish Health Authority and the Danish Administrative Regions. Only consenting staff were tested and informed about their result.

RESULTS

A total of 25 950 healthcare workers and administrative personnel at hospitals, prehospital services, and specialist practitioners in the Central Denmark Region were invited. Of these, 17 987 (69%) showed up for blood sampling, and 17 971 had samples available for SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing (see flowchart in Supplementary Figure 1).

The overall unadjusted seroprevalence was 3.7% (95% CI, 3.5%–4.0%). After adjusting for assay sensitivity and specificity including their CIs, the overall seroprevalence was 3.4% (95% CI, 2.5%–3.8%).

Predictors of Risk

For age- and sex-stratified seroprevalence of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Age- and Sex-stratified Seroprevalence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Antibody

| Female | Male | Total | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonreactive | Reactive | Nonreactive | Reactive | Nonreactive | Reactive | |||||||

| Age, y |

No. | No. | Unadjusted, % (95% CI) | Adjusteda, % (95% CI) | No. | No. | Unadjusted, % (95% CI) | Adjusteda, % (95% CI) | No. | No. | Unadjusted, % (95% CI) | Adjusteda, % (95% CI) |

| ≤29 | 1669 | 97 | 5.49 (4.53–6.66) | 5.20 (3.89–6.46) | 247 | 19 | 7.14 (4.64–10.9) | 6.92 (4.09–10.8) | 1916 | 116 | 5.71 (4.78–6.80) | 5.42 (4.09–6.59) |

| 30–39 | 3189 | 115 | 3.48 (2.91–4.16) | 3.11 (2.00–3.87) | 605 | 29 | 4.57 (3.21–6.49) | 4.24 (2.52–6.21) | 3794 | 144 | 3.66 (3.11–4.29) | 3.29 (2.20–4.02) |

| 40–49 | 3971 | 159 | 3.85 (3.31–4.48) | 3.49 (2.40–4.22) | 589 | 16 | 2.64 (1.64–4.25) | 2.24 (.81–3.88) | 4560 | 175 | 3.70 (3.20–4.27) | 3.33 (2.26–4.01) |

| 50–59 | 3980 | 143 | 3.47 (2.95–4.07) | 3.09 (2.02–3.79) | 525 | 18 | 3.31 (2.12–5.18) | 2.94 (1.35–4.84) | 4505 | 161 | 3.45 (2.96–4.01) | 3.08 (2.01–3.74) |

| ≥60 | 2041 | 60 | 2.86 (2.23–3.66) | 2.46 (1.31–3.32) | 464 | 12 | 2.52 (1.46–4.35) | 2.11 (.64–3.97) | 2505 | 72 | 2.79 (2.23–3.50) | 2.39 (1.28–3.18) |

| Total | 14 850 | 574 | 3.72 (3.43–4.03) | 3.36 (2.38–3.84) | 2430 | 94 | 3.72 (3.05–4.54) | 3.36 (2.19–4.24) | 17 280 | 668 | 3.72 (3.45–4.01) | 3.36 (2.38–3.82) |

Seroprevalences are presented as percentages with 95% CIs. Inconclusive antibody results (n = 23 [0.1%]) were not included in this table.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

aAdjusted for assay sensitivity and specificity.

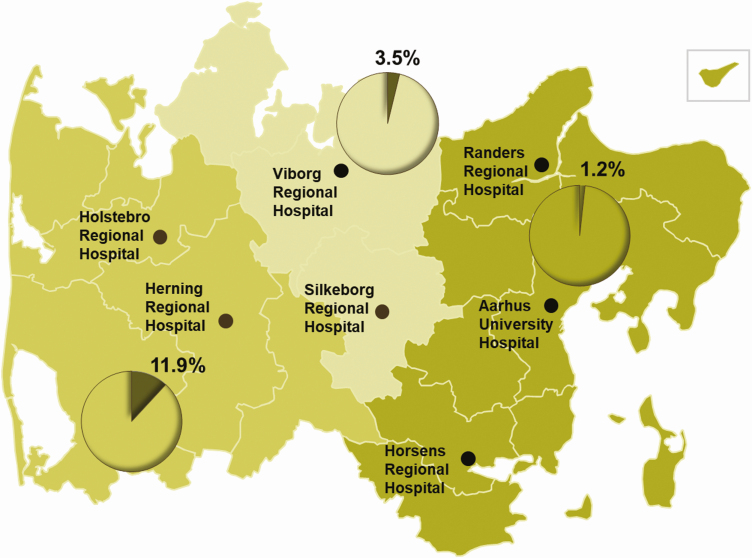

There was no difference in seroprevalence according to sex. The youngest age group (<30 years) had the highest seroprevalence (Supplementary Table 1). The seroprevalence among hospital employees was higher in RHWJ than in RHCJ (11.9% vs 3.5%; difference, 8.5 pp [95% CI, 7.1–10.0]) and East (11.9% vs 1.2%; difference, 10.7 pp [95% CI, 9.5–12.2]) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of adjusted seroprevalence according to geographical area in the Central Denmark Region. The Central Denmark Region covers an area of 13 000 km2. Herning and Holstebro Regional Hospitals serve the western part; Viborg and Silkeborg Regional Hospitals serve the central part; Randers and Horsens Regional Hospitals and Aarhus University Hospital serve the eastern part.

Psychiatry and social services, pharmacies, and IT and administrative departments had a low adjusted seroprevalence (psychiatric departments: 1.0% [95% CI, .0%–1.8%]; pharmacies, IT, and administration departments: 1.7% [95% CI, .4%–3.0%]).

The high seroprevalence in the RHWJ was analyzed separately. The emergency departments had the highest adjusted seroprevalence (29.7%), while departments with no or limited patient contact had the lowest seroprevalence (1.8%) (see Table 2 for seroprevalence and pairwise comparisons of seroprevalence between groups). Risk of infection also depended on profession. In RHWJ, nursing staff (18.2%), medical doctors (12.8%), and biomedical laboratory scientists (12.9%) had higher seroprevalence compared to medical secretaries (2.5%), while no differences by profession were seen for RHCJ and East (see Table 3 for seroprevalence and Supplementary Table 2 for comparisons of seroprevalence according to profession).

Table 2.

Distribution of Adjusted Seroprevalence According to Affiliation in Regional Hospital West Jutland and Pairwise Comparisons of Seroprevalence Between Departments

| Seroprevalence |

Emergency Departments (n = 165) | Medical Departmentsa (n = 829) | Surgical Departmentsb (n = 556) | Department of Biochemistry (n = 150) | Service Sectionc (n = 286) | Anesthesiology (n = 300) | Radiology and Nuclear Medicine (n = 153) | Departments With Limited Patient Contactd (n = 362) | Othere (n = 125) | Total (N = 2926) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Seroprevalence | 29.7 (23.1–37.6) | 15.0 (12.5–17.8) | 12.8 (10.0–16.0) | 12.0 (7.39–18.4) | 11.1 (7.68–15.5) | 9.89 (6.69–14.0) | 6.69 (3.54–12.4) | 1.79 (.31–3.90) | 6.97 (3.31–13.1) | 12.0 (10.5–13.4) |

| Difference | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) | pp (95% CI) |

| Other | 22.8 (13.7–31.3) | 8.07 (1.51–12.6) | 5.79 (−.87 to 10.5) | 4.99 (−2.56 to 12.2) | 4.15 (−2.79 to 9.72) | 2.91 (−3.90 to 8.27) | −0.01 (−6.88 to 6.37) | −5.19 (−11.4 to −1.07) | … | … |

| Departments with limited patient contact | 28.0 (21.0–35.9) | 13.3 (10.1–16.3) | 11.0 (7.60–14.4) | 10.2 (5.20–16.7) | 9.34 (5.40–13.8) | 8.10 (4.38– 12.3) | 5.18 (1.26–10.7) | … | … | … |

| Radiology and nuclear medicine | 22.8 (14.2–31.2) | 8.08 (2.19–12.4) | 5.80 (−.20 to 10.4) | 5.00 (−1.99 to 12.2) | 4.16 (−2.15 to 9.58) | 2.92 (−3.26 to 8.13) | … | … | … | … |

| Anesthesiology | 19.9 (12.1–28.3) | 5.15 (.46–9.27) | 2.88 (−1.96 to 7.29) | 2.08 (−3.96 to 9.18) | 1.24 (−4.00 to 6.55) | … | … | … | … | … |

| Service section | 18.6 (10.7–27.1) | 3.92 (−1.02 to 8.22) | 1.64 (−3.44 to 6.23) | 0.84 (−5.39 to 8.05) | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Department of biochemistry | 17.8 (8.55–26.8) | 3.08 (−3.77 to 8.33) | 0.80 (−6.15 to 6.29) | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Surgical departments | 17.0 (9.64–25.2) | 2.28 (−1.67 to 6.08) | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Medical departments | 14.7 (7.55–22.9) | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

Seroprevalences are adjusted for assay sensitivity and specificity and presented as percentages with 95% CIs. Differences between affiliations are presented as percentage point with 95% CI; significant differences after Bonferroni correction are shown in bold. Inconclusive results in the antibody test (n < 5) were not included in this table.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; pp, percentage point.

aInternal medicine, pediatrics, oncology, and neurology.

bAll surgical departments, obstetrics and gynecology, otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery, and ophthalmology.

cCleaning services, hospital porters, clothing and waste management, depot and archive, telephone switchboard, guidance for patients, relatives, and staff.

dOccupational and social medicine, physiotherapy and occupational therapy, administration, department of technical services, and kitchen.

eParticipants without affiliation (eg, students and participants on call, wage subsidy, and hourly wage workers).

Table 3.

Distribution of Seroprevalence According to Profession in Hospital Employees in the Central Denmark Region (n = 15 261)

| Location | Nursing Staffa, % (95% CI) |

Medical Doctors, % (95% CI) |

Biomedical Laboratory Scientists, % (95% CI) |

Medical Secretaries, % (95% CI) |

Other, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHWJ | 18.2 (15.9–20.7) | 12.8 (9.67–16.6) | 12.9 (8.21–19.4) | 2.52 (.74–5.31) | 5.77 (4.03–7.62) |

| RHCJ | 5.22 (3.76–6.60) | 2.99 (1.21–5.47) | 2.01 (.21–5.71) | 1.57 (.10–3.89) | 1.62 (.37–2.91) |

| East | 1.24 (.22–1.78) | 1.89 (.70–2.91) | 1.43 (.18–2.75) | 1.09 (.00–2.26) | 0.80 (.00–1.45) |

| Total No. | 7011 | 2066 | 1017 | 1351 | 3796 |

Seroprevalences are adjusted for assay sensitivity and specificity. Inconclusive results in the antibody test (n = 20) were not included in this table.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; East, Randers and Horsens Regional Hospitals, and Aarhus University Hospital serving the eastern part; RHCJ, Regional Hospital Central Jutland; RHWJ, Regional Hospital West Jutland.

aNurses, social and healthcare assistants, and radiographers.

The risk of infection was associated with workplace rather than place of living. The adjusted seroprevalence in participants working in RHWJ but living in the central or eastern part of the region was 10.7% (95% CI, 8.0%–13.7%), whereas the adjusted seroprevalence in participants living in the western part of the region, but working in East or RHCJ, was 2.6% (95% CI, .7%–5.8%; difference, 8.1 pp [95% CI, 4.1–11.7]).

To allow for multivariable analysis, a logistic regression analysis was performed. In this analysis, however, we did not adjust for the assay sensitivity and specificity. The analysis confirmed that nursing staff, medical doctors, and biomedical laboratory scientists had a higher risk of testing positive than medical secretaries, who served as reference (ORs, 7.3 [95% CI, 3.5–14.9]; 4.0 [95% CI, 1.8–8.9]; and 5.0 [95% CI, 2.1–11.6], respectively), while adjusting for age group and sex. The analysis also showed that individuals younger than 30 years had a higher risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies than the other age groups combined (OR, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.4–2.6]). The analysis showed no effect of sex.

Seroprevalence Among Blood Donors

The adjusted seroprevalence among 360 blood donors was low in both the western part (1.2% [95% CI, .0%–4.4%]) and the eastern part of the region (0.6% [95% CI, .0%–3.5%]; difference, 0.6 pp [95% CI, −2.4 to 3.6]).

Association Between SARS-CoV-2 RNA and Total Antibodies

During 28 February–23 June 2020, 4803 (26.7%) of the participants in the seroprevalence initiative (n = 17 971) had been tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in an oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal swab or tracheal aspirate by RT-PCR (Table 4). A total of 341 (7.1%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, and among these, 334 (98.0%) were subsequently seropositive. Among the total 668 seropositive participants, 433 (64.8%) had been tested for viral RNA and 50.0% had a positive result.

Table 4.

Association Between Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 RNA by Reverse-transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction and Total Antibodies

| SARS-CoV-2 Total Antibodies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Total | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 PCR | No. | (%) | No. | (%) | No. |

| Negative | 4358 | (97.8) | 99 | (2.2) | 4457 |

| Positive | 6 | (1.8) | 334 | (98.2) | 340 |

| Total No. | 4364 | 433 | 4797a | ||

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

aInconclusive results in the antibody test (n = 6) were not included in this table.

Only 23.1% of the staff tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA were employed in RHWJ, but they accounted for 66.6% of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA–positive participants. Among 351 seropositive participants employed at RHWJ, 270 were at some point additionally tested for viral RNA and 224 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA (63.8% of seropositives).

DISCUSSION

The adjusted seroprevalence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare workers and administrative personnel at hospitals, prehospital services, and specialist practitioners in the Central Denmark Region was 3.4%. There were, however, sizable differences in seroprevalence between hospitals ranging from <2% in East to almost 12% in the RHWJ, even though the distance between the hospitals situated farthest apart is only 120 km. In RHWJ, the risk was highest in the emergency departments and higher in departments and professions with frequent patient contact, while no such pattern was seen in the central or eastern parts.

Among the seropositive staff, 65% had previously been tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, and 50% of the seropositives had already been confirmed SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive. This percentage was particularly high in the RHWJ where 64% of all seropositives had a prior positive test for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. This indicates that personnel suspected of COVID-19, to a high degree, are being referred for PCR testing. We would expect to have found a higher percentage of concomitant seropositive and PCR-positive staff if the early test strategies (prior to 1 April 2020) had allowed for PCR testing of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic personnel.

The combination of serological and molecular findings also allowed us to verify the sensitivity of the serological assay used: 98% of employees previously tested positive for viral RNA had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Large differences in seroprevalence in healthcare workers have been reported (1%–43%) [1, 2, 8] similar to the large differences in severity of the COVID-19 epidemic between countries [7]; however, comparison to the background population level has not been reported.

In Denmark, the seroprevalence in blood donors differs between areas with low prevalence in the Central Denmark Region [9]. However, similar to findings from Italy, large geographical differences within the Central Denmark Region have been shown in this study but within an even smaller geographical area [1, 4]. While there is evidence of a high number of infected individuals during March and April among staff working at RHWJ and a higher incidence of infection in patients from the hospital’s service area [7], this does not translate into a high seroprevalence in the background population of the area: First, the seroprevalence in blood donors from the area tested during April was 1% [9]. Second, the seroprevalence in 180 anonymized blood donations given in June in the RHWJ service area was 1.2%. Third, the seroprevalence was low in departments and professions with no patient contact. Fourth, we found that staff living but not working in the western part of the region had a low seroprevalence, whereas staff working but not living in the western part of the region had a high prevalence of antibodies, suggesting in-hospital transmission.

A recently published study among healthcare workers in the Capital Region of Denmark reported a similar seroprevalence of 4.0% [10]. However, we found much greater differences between hospitals and departments and used an antibody test with a higher sensitivity. In healthcare personnel in the United States, differences in seroprevalence between hospitals were even higher (0.8%–31.2%) with the lowest seroprevalence among personnel who reported always wearing a face covering [5].

Possible explanations for transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to the staff in RHWJ are higher levels of population transmission in the service area of RHWJ (cumulative incidence of 210 per 100 000 inhabitants vs 85 per 100 000 in the eastern part) [7]. Moreover, older hospital buildings with less space, fewer single-bed rooms, and less-optimal facilities for isolation of patients with infectious diseases may have added to the risk. Whether inadequate access to proper PPE and/or insufficient training may also play a role cannot be answered by this study. However, the finding that frequent patient exposure is a key risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion may be less significant today, due to a more rigorous and systemic use of PPE and other strategies to minimize SARS-CoV-2 transmission in most hospitals compared to the start of the pandemic. In the eastern part of the region, contact tracing and testing were performed more aggressively at Aarhus University Hospital early in the epidemic, which could have reduced the burden of disease.

Studies have shown that risk factors for COVID-19 among healthcare workers include working at a clinical department, working in a high-risk vs general department, suboptimal hand hygiene before or after patient contact, longer work hours, improper PPE use, working as a medical doctor, contact with COVID-19 patients, contact with “superspreader” patients, and staff of younger age developing more severe disease perhaps as a sign of more intense exposure [4, 11–14]. In line with this, we found that younger staff were more likely to be seropositive. Frequent shifts and closer contact to newly admitted and yet undiagnosed patients among young employees and staff working at the emergency department may lead to higher risk of exposure. The high risk of infection among biomedical laboratory scientists reflects that in Denmark this group of staff has frequent patient contact as they are responsible for drawing blood.

Half of the staff with a positive serological test had been tested positive by PCR prior to the antibody testing. Since 30%–40% of COVID-19 patients may be asymptomatic [15], this indicates that a thorough and targeted testing activity has been performed. However, it also raises the case whether healthcare workers should be screened for SARS-CoV-2 on a regular basis since transmission can occur even in the absence of symptoms [16–18].

Strengths and Limitations

This is one of the largest studies assessing the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among healthcare workers to date, and the study was performed with an assay with a proven sensitivity of 97%. The participation rate was 69%. Healthcare workers not able to work (due to, eg, sick leave, maternity leave) were also invited to participate but were not expected to be tested. Participation may have depended on exposure or suspicion of infection (Supplementary Figure 1). On the other hand, healthcare workers who had already been diagnosed with COVID-19 may have been less likely to participate since they were expecting to test positive. We may therefore, either over- or underestimate the true prevalence. Information about original job title and workplace was retrieved from the employer’s registration system. However, due to the epidemic and subsequent closing or partial closing of some departments, some employees were transferred to departments treating COVID-19 patients. Since information about use of PPE or specific tasks were not available, more detailed information about risk factors could not be assessed.

This study was done after the epidemic had slowed down in Denmark in a time period with few new infections. The median time from symptom onset to detection of total SARS-CoV-2 antibodies is 11 days [19], meaning that most infected staff would already have seroconverted when this survey was done. The dynamics of antibody concentrations and whether they wane over time is still unknown, but from our own experience with a small group (n = 12) of convalescent plasma donors, serological test results and virus neutralizing antibody titers remain unchanged during 3 months of follow-up. Among PCR-confirmed COVID-19 cases, 98% were antibody-positive individuals, which is consistent with the results of the validation of the assay. Even though the specificity of the Wantai assay was acceptable at 99.5%, the low seroprevalence in most hospitals implies a low positive predictive value of the test. Since we do not have a gold standard to confirm positive or negative results, we estimated the CI with a method that took both the sample variation and the uncertainty in the sensitivity and specificity into account adjusting for the test performance. Finally, cross-reactivity with other pathogens (eg, other coronaviruses) could result in false-positive antibody test results.

Taking these limitations into account, this study should raise awareness of means to avoid in-hospital transmission by improving institutional infection control measures including training on infection control procedures and ensuring compliance with PPE use [20], as well as considering testing of both symptomatic and asymptomatic healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 on a regular basis [18, 21].

CONCLUSIONS

We found large intraregional differences in the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among staff working in the healthcare sector within a small geographical area of Denmark. The seroprevalence in the western part of the region was significantly higher among healthcare workers with patient contact than among the background population, suggesting in-hospital transmission. Half of all seropositive staff had already been tested positive by PCR prior to this survey, indicating a targeted testing strategy but also highlighting a need for PCR test screening in healthcare workers.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. S. J., S. M., T. G., K. N., L. Ø., M. K. T., H. J. M., and C. E. planned the study. S. J., S. M., A. M. A., J. K. B., J. D. R., T. G., and C. E. analyzed and interpreted the data. S. J., S. M., C. E., and K. A. K. drafted the manuscript. S. M., C. E., T. G., M. K. T., and H. J. M. were responsible for the laboratory analyses. All authors were involved in critically revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the following people for their exceptional work in coordinating the study and technical assistance: all the involved staff from the Department of Clinical Immunology, Department of Clinical Biochemistry, and Department of Clinical Microbiology at Aarhus University Hospital; staff from the Department of Clinical Biochemistry at Regional Hospital West Jutland, Regional Hospital Central Jutland, Horsens Hospital, and Randers Hospital; and Grenå Sundhedshus.

Disclaimer. The funders had no role in analyzing the results of this study.

Financial support. This work was supported by The Central Denmark Region. The Wantai tests were donated by The Danish Health Authority requisitioned through Statens Serum Institut.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. Sandri MT, Azzolini E, Torri V, et al. IgG serology in health care and administrative staff populations from 7 hospital representative of different exposures to SARS-CoV-2 in Lombardy, Italy. medRxiv [Preprint]. Posted online 26 May 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.24.20111245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mansour M, Leven E, Muellers K, Stone K, Mendu DR, Wajnberg A. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among healthcare workers at a tertiary academic hospital in New York City. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35:2485–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Comar M, Brumat M, Concas MP, et al. COVID-19 experience: first Italian survey on healthcare staff members from a mother-child research hospital using combined molecular and rapid immunoassays test. medRxiv [Preprint]. Posted online 22 April 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.19.20071563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Self WH, Tenforde MW, Stubblefield WB, et al. CDC COVID-19 Response Team; IVY Network Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among frontline health care personnel in a multistate hospital network—13 academic medical centers, April–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1221–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harritshøj L, Gybel-Brask M, et al. Comparison of sixteen serological SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays in sixteen clinical laboratories. medRxiv [Preprint]. Posted online 2 August 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.30.20165373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Statens Serum Institut. Overvågning af COVID-19 [in Danish]. 2020. Available at: https://www.ssi.dk/sygdomme-beredskab-og-forskning/sygdomsovervaagning/c/covid19-overvaagning. Accessed 10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Behrens GMN, Cossmann A, Stankov MV, et al. Perceived versus proven SARS-CoV-2-specific immune responses in health-care professionals. Infection 2020; 48:631–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erikstrup C, Hother CE, Pedersen OBV, et al. Estimation of SARS-CoV-2 infection fatality rate by real-time antibody screening of blood donors [manuscript published online ahead of print 25 June 2020]. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iversen K, Bundgaard H, Hasselbalch RB, et al. Risk of COVID-19 in health-care workers in Denmark: an observational cohort study [manuscript published online ahead of print 3 August 2020]. Lancet Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30589-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chu J, Yang N, Wei Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 54 medical staff with COVID-19: a retrospective study in a single center in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol 2020; 92:807–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Response Team. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19—United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:477–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ran L, Chen X, Wang Y, Wu W, Zhang L, Tan X. Risk factors of healthcare workers with coronavirus disease 2019: a retrospective cohort study in a designated hospital of Wuhan in China [manuscript published online ahead of print 17 March 2020]. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020; 323:1061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173:362–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, et al. Public Health–Seattle and King County and CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:2081–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:970–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Black JRM, Bailey C, Przewrocka J, Dijkstra KK, Swanton C. COVID-19: the case for health-care worker screening to prevent hospital transmission. Lancet 2020; 395:1418–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019 [manuscript published online ahead of print 28 March 2020]. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xiao J, Fang M, Chen Q, He B. SARS, MERS and COVID-19 among healthcare workers: a narrative review. J Infect Public Health 2020; 13:843–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rivett L, Sridhar S, Sparkes D, et al. Screening of healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 highlights the role of asymptomatic carriage in COVID-19 transmission. eLife 2020; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.