Abstract

Tungsten is a naturally occurring metal that is increasingly used in industry and medical devices, and is labeled as an emerging environmental contaminant. Like many metals, tungsten accumulates in bone. Our previous data indicate that tungsten decreases differentiation of osteoblasts, bone-forming cells. Herein, we explored the impact of tungsten on osteoclast differentiation, which function in bone resorption. We observed significantly elevated osteoclast numbers in the trabecular bone of femurs following oral exposure to tungsten in male, but not female mice. In order to explore the mechanism(s) by which tungsten increases osteoclast number, we utilized in vitro murine primary and cell line pre-osteoclast models. Although tungsten did not alter the adhesion of osteoclasts to the extracellular matrix protein, vitronectin, we did observe that tungsten enhanced RANKL-induced differentiation into tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive mononucleated osteoclasts. Importantly, tungsten alone had no effect on differentiation or on the number of multinucleated TRAP-positive osteoclasts. Enhanced RANKL-induced differentiation correlated with increased gene expression of differentiated osteoclast markers Nfatc1, Acp5, and Ctsk. Although tungsten did not alter the RANK surface receptor expression, it did modulate its downstream signaling. Co-exposure of tungsten and RANKL resulted in sustained positive p38 signaling. These findings demonstrate that tungsten enhances sex-specific osteoclast differentiation, and together with previous findings of decreased osteoblastogenesis, implicate tungsten as a modulator of bone homeostasis.

Keywords: tungsten, bone, osteoclasts, metals, RANKL, trabecular bone, mice, osteoclastogenesis, differentiation, signaling

Tungsten is known for its strength and conductivity and is commonly found in electronics, industrial devices, and increasingly in the medical field (ATSDR, 2005; Lemus and Venezia, 2015; Shah Idil and Donaldson, 2018). Because of these properties, tungsten is replacing other metals, such as lead, in manufacturing. Some brands of “nontoxic” shot, required for use in hunting waterfowl, contain 95% tungsten (Thomas et al., 2009). Veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq after being involved in incidents with improvised explosive devices have significant levels of tungsten in their urine (Gaitens et al., 2017). The increased appearance of tungsten in the medical field, as drug-eluting stents, embolism coils, and radiotherapy shields, may identify a group of people potentially more exposed and at risk to tungsten toxicity (Shah Idil and Donaldson, 2018). There is limited knowledge on tungsten’s toxicology profile and its implications on human health, hence the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has classified tungsten as an emerging contaminant (EPA, 2008), and tungsten was nominated as a priority chemical for study (NTP, 2002).

Like many metals, tungsten preferentially accumulates within the bone (Guandalini et al., 2011). Upon oral exposure, tungsten rapidly accumulates in the bone within a week, while reaching a plateau after 4 weeks (Kelly et al., 2013). Tungsten accumulates more in young mice than older mice (Bolt et al., 2016), suggesting that tungsten incorporates into bone that is growing or remodeling. In mice given sodium tungstate (orthotungstate) orally, tungsten is heterogeneously incorporated into both cortical and cancellous bone tissue and bone marrow (BM) (VanderSchee et al., 2018). In bone, tungsten likely takes the form of a heteropolytungsate species, such as phosphotungstate (VanderSchee et al., 2018). Furthermore, bone accumulation of tungsten, or the “ON” rate, is much faster than removal or “OFF” rate (Kelly et al., 2013). Although the majority of tungsten is excreted through the kidneys, it is estimated when given a single dose of radiolabeled tungsten (181W), about 50% of the retained total body tungsten would accumulate in the bone after 1 month (Leggett, 1997). Extrapolate the model to 10 years after administration, and whole body tungsten is attributed to just the bone (Leggett, 1997). This suggests that even after cessation of exposure, the bone may provide an endogenous reservoir for tungsten exposure. Standard chelation therapy is ineffective at mobilizing tungsten (Bolt et al., 2015). Thus, it is important to define tungsten-induced changes to the bone and BM microenvironment.

Bone continuously undergoes remodeling, a process that incorporates the actions of osteoblasts, which form bone, and osteoclasts, which resorb bone, to maintain bone homeostasis. Osteoblasts produce several bone matrix proteins, and also regulate osteoclast function through direct interaction and secretion of soluble mediators, such as RANKL (Tanaka et al., 2005). Osteoblasts are derived from mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), however, MSCs can also differentiate into other cell types including myocytes, adipocytes, and fibroblasts in skin and connective tissue (Chen et al., 2016). In our previous study, we demonstrated in vitro that tungsten enhanced adipogenic differentiation of MSCs and decreased osteoblastogenesis in vitro (Bolt et al., 2016). Notwithstanding, we observed increased adipocytes in the BM of mice following tungsten exposure (Bolt et al., 2016).

Osteoclasts are derived from hematopoietic stem cells and typically reside within the trabecular regions of the bone. They are responsible for calcium resorption and do so by forming resorptive pits at the edges of trabecular bone (Vaananen et al., 2000). The master switch that regulated terminal differentiation of osteoclasts is the transcription factor NFATc1 (Park et al., 2017; Wada et al., 2006). Activation of NFATc1 is regulated by the ligand RANKL that binds to its receptor RANK to initiate a signaling cascade that includes the downstream activation of NF-κB and MAP kinases (MAPKs) (Park et al., 2017; Wada et al., 2006).

Although tungsten alters osteoblast differentiation, the effects of tungsten on osteoclast biology are unknown. In the current study, we found that in mice exposed to tungsten orally, the osteoclast number was significantly increased. Tungsten enhances RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation in vitro, although it had no effect added alone. Finally, we demonstrate that tungsten enhances the downstream signaling of RANK, increasing the differentiation of osteoclasts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tungsten Exposure

Sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na2WO4·2H2O, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri) was used in all tungsten exposure experiments in vivo and in vitro because orthotungstate (WO4) is shown as the most predominant form in solution at a neutral pH (Kelly et al., 2013). Fifteen parts per million (ppm) or 15 µg/ml of tungsten was calculated based on elemental weight of tungsten and not the compound itself. For example, sodium tungstate (Na2WO4·2H2O) has a molecular weight of 329.85 g/mol and elemental tungsten (W) has a molecular weight of 183.84 g/mol, thus to achieve 1 g of elemental tungsten, an equivalent of 1.795 g of sodium tungstate dihydrate would be used. For in vivo exposure, sodium tungstate dihydrate was dissolved directly in tap water. For tissue culture, a working stock of 5 µg/µl tungsten solution was made by dissolving 71.43 mg of sodium tungstate dihydrate in 8 ml autoclaved milliQ water and filter sterilized through a 0.2-µm filter. Tungsten stock solution was then aliquoted and stored at −20°C.

In Vivo Tungsten Exposure

All animal experiments were approved by the McGill University Animal Care Committee (Montréal, Quebec, Canada). All mice were housed and performed in the Lady Davis Institute animal facility (Montréal, Quebec, Canada) and were given food and water ad libitum. Five-week-old C57BL/6 male and female mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were exposed to either tap water or 15 ppm tungsten in tap water for 4 weeks. Tungsten water was changed every 2–3 days to prevent polyoxotungstate formation (Kelly et al., 2013). As observed previously, no apparent symptoms of overt toxicity, changes in animal weight, appearance, or water intake were observed throughout the 4-week exposure period (Kelly et al., 2013). At the end of study period, mice were then euthanized under isoflurane followed by cardiac puncture or CO2 asphyxiation in addition to cervical dislocation.

GST-RANKL Production

The GST-RANKL plasmid was a gift from Dr Morris Manolson (Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada) (Voronov et al., 2005). For every pull-down, bacteria were freshly streaked on LB agar with 100 µg/ml carbenicillin, followed by inoculating 5 ml LB broth with 100 µg/ml carbenicillin overnight. The next day, 4–5 ml of the bacterial culture was expanded and grown to an optical density of 0.6 at an absorbance wavelength of 600 nm. A final concentration of 0.1 mM IPTG was used to induce GST-RANKL expression overnight at 16°C. The bacterial pellet was harvested and lysed in 20 mM TRIS pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1× protease inhibitor, and 1 mg/ml lysozyme Followed by sonication (45% amplitude, 15 s each, total of 5 rounds) and incubation with 10 µg/ml DNase 1 and 1% Triton X-100. Bacterial debris was then pelleted and the supernatant isolated for GST-RANKL pull-down using Pierce Glutathione Agarose beads (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts). After incubation, glutathione beads were washed with washing buffer (50 mM TRIS pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) with 0.1% Triton X-100 solution, twice, followed by washing buffer, twice. GST-RANKL was then eluted using 0.01 M reduced l-glutathione (Sigma) in washing buffer. GST-RANKL solution was then dialyzed using dialysis tubing (Spectrum Laboratories) against 2 litres of sterile PBS, overnight, at 4°C. GST-RANKL was then filter sterilized by passing through a 0.2-µm filter followed by concentrating using a 10-kDa MWCO column (Millipore, No. UFC801024). Bradford assay was used to determine the concentration of GST-RANKL and a working solution of 100 ng/µl GST-RANKL diluted in protein stabilizing buffer (ThermoFisher) was used. To verify the GST-RANKL pull-down, we electrophoresed the extracts through an SDS-PAGE, followed by either a Coomassie blue stain or an immunoblot for the GST fusion part of the protein. sRANKL by itself is 19.7 kDa in size whereas GST is 26 kDa, making the combined GST-sRANKL a total of about 46 kDa.

Cell Culture

RAW 264.7 (ATCC TIB-71) and COS-1 cells (ATCC CRL-1650) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Wisent, St Bruno, Quebec, Canada), 10% FBS (Wisent), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Wisent). RAW 264.7 cells were subcultured by scraping and re-plated at a ratio of 1:6 every 2 to 3 days. Cos-1 cells were subcultured with 0.05% trypsin (Wisent) at a ratio of 1:6 every 2–3 days.

Primary BM-derived osteoclasts were derived from BM cells were obtained by flushing the BM of femurs, tibiae, and humeri of age 8–10-week-old C57BL/6 male mice either by syringe or centrifugation. Cells were cultured using α-MEM (AMEM; Wisent), 10% FBS (Wisent), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Wisent). Myeloid progenitors were enriched by seeding 30 ×106 BM cells in a T75 flask with 25 ng/ml h-MCSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, New Jersey). After 24 h, the enriched myeloid suspension cells were then counted and seeded for downstream assays.

Adhesion Assay

Primary BM was isolated as above, and the enriched myeloid suspension cells were then seeded at 21 × 106 cells per non-tissue culture-treated 100 mm petri dish (VWR) with 50 ng/ml h-MCSF (PeproTech). For these assays, osteoclasts were differentiated on bacterial plates because mature osteoclasts tend to adhere strongly to tissue culture plastics and 0.25% trypsin (5× trypsin) was unable to lift off osteoclasts on tissue culture plates. In addition, we did not want to jeopardize the viability of these giant cells by mechanically scraping them, so differentiating on bacterial plates followed by 0.05% trypsin allowed lifting of viable osteoclasts. After 24 h, myeloid progenitors were then exposed to 15 ng/ml sRANKL (PeproTech) with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten. sRANKL and tungsten were replenished along with media change every 2 days. On day 8 of osteoclast differentiation, cells were harvested by 1× trypsin (Wisent), counted, and seeded at 50 000 cells in 500 µl media, on vitronectin-coated, 24-well plates (500 ng/ml, Sigma) with 50 ng/ml h-MCSF and with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten supplemented in the media. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 45 min and then unattached cells removed by PBS wash. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) followed by tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining as indicated below. Number of TRAP-positive cells were counted using ImageJ software.

TRAP Staining

In vitro

Primary enriched myeloid suspension cells were seeded at 250 000 cells in a 24-well plate with 50 ng/ml h-MCSF. Twenty-four hours after seeding, 15 ng/ml recombinant sRANKL (Peprotech), 15 µg/ml tungsten, or the combination was introduced in the media. RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at 10 000 cells/well in a 24-well plate. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with 15 ng/ml of GST-RANKL, 15 µg/ml tungsten, or the combination. RANKL and tungsten were replenished along with media change every 2 days. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA on day 8 (primary culture) or day 5 (RAW 264.7 cells) of culture and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100. Incubation with 0.025% Napthol AS-BI phosphate substrate (Sigma) in incubation buffer (112 mM sodium acetate anhydrous, 49 mM l-(+)-tartaric acid disodium salt, 0.28% glacial acetic acid, pH 4.7–5.0) at 37°C for 30 min allows TRAP enzymatic activity to occur. The resulting napthol product reacts with 0.125% pararosaniline dye (Sigma) and 0.1% sodium nitrite (Sigma) incubated in incubation buffer with 50 mM HCl for 10 min at 37°C. Cells are then washed twice with PBS and counterstained with activated hematoxylin. TRAP-positive primary cell cultures were counted using ImageJ and the size of multinucleated osteoclast was analyzed using Aperio ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems, Concord, Ontario, Canada), whereas RAW 264.7 cultures were then analyzed using the Gelcount Plate Scanner (Oxford-Optronix). The plate was scanned at 2400 dpi image resolution using the software’s auto well-mask detection and default charm settings. TRAP-positive colonies were counted using refined optimization settings, where edge detection sensitivity was set to 32, colony diameter range set to 50–632 µm, center detection sensitivity set to 14, and the minimum colony threshold set to 5 µm.

In vivo

Femurs sections were harvested from in vivo tungsten-exposed mice, tissue was formalin fixed and decalcified in 10% EDTA. Following decalcification, tissue was embedded in paraffin and 5-μm sections were prepared on glass slides by McGill Bone Center. Sections were then deparaffinized in Histo-Clear (ThermoFisher Scientific) followed by sequential alcohol rehydration to distilled water. Sections were subjected to TRAP staining. Briefly, sections were incubated in incubation buffer solution containing napthol-ether substrate for 1 h at 37°C followed by incubation in a sodium nitrite-pararosaniline solution for 12 min. Sections were washed in distilled water followed by counterstaining in 0.05% Fast Green for 90 s. Sections were rinsed in distilled water followed by dehydration in sequential alcohol concentrations and Histo-Clear. Sections were mounted in Permount mounting medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). TRAP-positive osteoclasts were counted on ImageJ software.

RNA Harvest and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Primary enriched myeloid suspension cells were seeded at a density of 3 million cells per 2 ml in a 6-well plate with 50 ng/ml h-MCSF (PeproTech). Twenty-four hours after seeding, 15 ng/ml recombinant sRANKL (Peprotech), 15 µg/ml tungsten, or the combination was introduced in the media. sRANKL and tungsten were replenished along with media change every 2 days and RNA was harvested on day 7 of culture.

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at 50 000 cells/well in a 6-well plate with 2 ml of growth media. After 24 h, cells were treated with 15 ng/ml of GST-RANKL, 15 µg/ml tungsten, or the combination. RNA was harvested after 24 h of GST-RANKL induction.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed as described previously (Wu et al., 2019). A final concentration of 500 nM for each forward and reverse primer was used (see Table 1 for sequences). qPCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (ThermoFisher Scientific), with the annealing temperature set at 60°C for 40 amplification cycles. The 2-ΔΔCT method was used to analyze qPCR data. Primers obtained from IDT (Coralville, Iowa) were validated to have a standard slope of −3.3 ± 0.1 and no primer dimers observed during the melt curve.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences for qPCR

| Gene (GenBank Accession Number) | mRNA Forward Primer | mRNA Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| Nfatc1 (NM_001164112) | 5′-CCC TTT AAA AAT GAG GAC AAT AGC TTT-3′ | 5′-TTG CTG CCC TTT CAC TGA TG-3′ |

| Ctsk (NM_007802.4) | 5′-GTT GTA TGT ATA ACG CCA CGG C-3′ | 5′-CTT TCT CGT TCC CCA CAG GA-3′ |

| Acp5 (NM_001102405.1) | 5′-CCA TTG TTA GCC ACATAC GG-3′ | 5′-ACT CAG CAC ATA GCC CAC AC-3′ |

| Dcstamp (NM_029422.3) | 5′-TCC TCC ATG AAC AAA CAG TTC CAA-3′ | 5′-AGA CGT GGT TTA GGA ATG CAG CTC-3′ |

| Itgav (NM_008402.3) | 5′-CAC GTC CTC CAG GAT GTT TCT C-3′ | 5′-CAA ACT CAA TGG GCT GGC AC-3′ |

| Itgb3 (NM_016780.2) | 5′-GTC GTC AGC CTT TAC CAG AAT-3′ | 5′-CCA CAG GCT TGA TAG TGA AAG A-3′ |

| Rn18s | Purchased from Qiagen, No. QT02448075 | |

| Tbp (NM_013684.3) | 5′-CCA ATG ACT CCT ATG ACC CCT A-3′ | 5′-CAG CCA AGA TTC ACG GTA GAT-3′ |

Luciferase Assay

Luciferase assays were performed in COS-1 cells as described previously (Bolt et al., 2016) using equal amounts (0.625 µg) of NF-ĸB-Luciferase (Gift from Dr Rongtuan Lin, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec) and pRL-TK Renilla plasmid (Promega). The luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) following manufactures protocol and quantified using the default settings on the GloMax 20/20 Luminometer (Promega). The level of NF-ĸB-Luciferase luminescence activity was normalized to the level of Renilla luminescence of each well.

Immunoblotting

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 106 cells per 100-mm tissue culture plates. After 24 h, cells were switched to 2.5% FBS with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten overnight (16–18 h). Cultures were then induced with 15 ng/ml GST-RANKL with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten in 2.5% serum and harvested at defined time points by scraping. Cell pellets were washed twice with ice-cold PBS followed by immediate lysing with Szak’s RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40) supplemented with 1× phosphostop (Roche) and 1× protease inhibitors (Roche). Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto 10% homemade acrylamide gels. Gels typically ran at 85 V for about 2 h, followed by overnight (16–18 h) transfer at 35 V, 4°C, onto activated PVDF membranes. Successful transfer and equal loading was confirmed by brief Ponceau staining. Blots were then blocked in 5% BSA (Sigma) in TBS-T for 1 h. Primary antibody was incubated at 4°C overnight (20–22 h), with constant agitation on a rotor (see Table 2 for primary antibody list). Blots were washed 3 times with TBS-T for 5 min, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated, secondary antibody for 1 h. Secondary antibody was diluted in 5% milk in TBS-T at 1:3000 or 1:5000 for either mouse (Amersham ECL, No. NA931V) or rabbit (Amersham ECL, No. NA934V), but for goat secondary (Santa Cruz sc-2020), a dilution of 1:2000 was used. Blots were then washed twice with TBS-T followed by a TBS wash before revealing with either enhanced chemiluminescene (GE Healthcare, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) or Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Sigma).

Table 2.

Primary Antibodies

| Primary Antibody | Company and Catalog No. | Dilution | Buffer | Amount of Protein Loaded (µg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phospho-p38 | Cell Signaling, No. 4511S | 1:1000 | Primary antibody buffer | 20 |

| Total p38a | Santa Cruz, No. sc-535-G | 1:500 | Primary antibody buffer | 50 |

| Phopho-p65 | Cell Signaling, No. 3033S | 1:1000 | Primary antibody buffer | 100 |

| Total p65 | Cell Signaling, No. 3034 | 1:1000 | Primary antibody buffer | 50 |

| Phospho-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204) | Cell Signaling, No. 9101L | 1:5000 | 5% milk-TBST | 40 |

| Total ERK 2 | Santa Cruz, No. sc-154 | 1:1000 | 5% milk-TBST | 40 |

| Phospho-SAPK/JNK (T183/Y185) | Cell Signaling, No. 9251S | 1:1000 | Primary antibody buffer | 40 |

| Total JNK 2 | Santa Cruz, No. sc-827 | 1:1000 | Primary antibody buffer | 40 |

| Phospho-mTOR (S2448) | Cell Signaling, No. 5536 | 1:1000 | Primary antibody buffer | 20 |

| Total mTOR | Cell Signaling, No. 2972S | 1:1000 | Primary antibody buffer | 50 |

| B-actin | Sigma, No. A5441 | 1:10,000 | 5% milk-TBST | 10–20 |

| GAPDH | Cell Signaling, No. 2118 | 1:10,000 | 5% milk-TBST | 10–20 |

| GST | Santa Cruz, No. sc-459 | 1:5000 | 5% milk-TBST | 1 |

Flow Cytometry

Cells were washed once in cold PBS and stained with Live/Dead Fixable Aqua Dead cell stain kit (Life Technologies, No. L34966) for 30 min. After washing with FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 5% FBS and 0.01 M NaN3), cells were incubated with AF647 anti-RANK antibody (1:75 dilution; BD Biosciences, No. 566348) and e450 anti-CD11b antibody (1:1000 dilution; eBioscience, No. 48-0112-82). Staining was analyzed using a BD LSR Fortessa in the Lady Davis Institute Flow Cytometry Facility.

CTX-1 ELISA

Plasma was collected using EDTA blood collection tube and stored in the −80°C. CTX-1 levels were assessed using ELISA (Novus Biologicals, Co, USA; No. NBP2-69074).

Statistical Analyses

All statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, California). For comparisons between 2 groups, student t test analysis was performed, whereas for comparisons between 3 or more groups, one-way ANOVA analysis was performed followed with Tukey’s post hoc tests. For the in vivo femur sections, two-way ANOVA was carried out for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

In Vivo Tungsten Exposure Increases the Number of TRAP-Positive Osteoclasts in Femurs of Male Mice

Tungsten alters MSC differentiation through increased adipogenesis and decreased osteogenesis. We hypothesized that tungsten may also alter osteoclast differentiation, potentially affecting bone homeostasis. To investigate this, we first asked whether tungsten exposure in mice altered osteoclast numbers. To do this, we exposed 5-week-old male and female wild-type C57BL/6 mice to 15 ppm tungsten for 4 weeks. We chose this concentration because (1) we have previously observed effects on B lymphocytes and MSCs at this time and tungsten concentration (Bolt et al., 2016; Kelly et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2019), and (2) it is the established action level in the state of Massachusetts, one of the only known regulatory actions regarding tungsten levels in groundwater (EPA, 2012). Although 15 ppm tungsten is relatively high, or 20 times more than what was reported in private residential wells in Fallon, Nevada (Koutsospyros et al., 2006), it is significantly less than the 2000 mg/L being evaluated for the anti-diabetic (Munoz et al., 2001) and anti-obesity (Claret et al., 2005) properties of tungstate. At the end of the experiment, femur sections were stained for TRAP to identify mature osteoclasts and manually counted. Tungsten significantly increased the amount of TRAP+ osteoclasts present in the trabecular regions of the femur in male mice by 2-fold (Figure 1), both in total number and per osteoclasts/trabecular area. However, tungsten did not affect the number of osteoclasts in the female trabecular sections. This finding builds on our previous findings, suggesting tungsten has sex-specific effects on bone homeostasis (Bolt et al., 2016). Additionally, we also evaluated osteoclast activity indirectly through the quantitation of C-terminal telopeptide (CTX-1) in the plasma (Supplementary Figure 1). CTX-1 is a serum biomarker indicative of bone turnover rate (Shetty et al., 2016). Tungsten increased the average CTX-1 plasma values in male, but not female mice. Although this was not statistically significant due to the high variability of CTX-1 in male mice, the data correlate with our observation of increased osteoclasts in the male trabecular femurs, suggesting that there are more active osteoclasts following tungsten exposure.

Figure 1.

Tungsten increases the number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts in the trabecular region of femurs in male C57BL/6 mice. Femurs from C57BL/6 male and female mice exposed to 15 ppm tungsten or tap water for 4 weeks were sectioned and stained for osteoclastic marker TRAP. A, Representative images of TRAP-positive osteoclasts, stained red, and shown with black arrows, whereas the spongy bone is stained green. Images were taken at 10× and scale bar represents 100 μm. B, Total osteoclasts observed in the trabecular region of the femur sections. Graphs show the average number of osteoclasts and average osteoclast/area of bone marrow ± SEM, n = 4. Two-way ANOVA was carried out for statistics, *p < .05.

Tungsten Does Not Enhance the Adhesion of Mature Osteoclasts to Vitronectin Surfaces

One might hypothesize that an increase in adhesion to the extracellular matrix could explain the increased osteoclast numbers observed in vivo (Figure 1). In fact, adhesion is required for RANKL to induce differentiation of pre-osteoclasts to mature osteoclasts (Mochizuki et al., 2012). Osteoclasts express αvβ3 integrin, a vitronectin receptor, and tightly bind to bone surfaces via arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD)-containing proteins, such as vitronectin (Rodan and Rodan, 1997). To test this, we asked whether tungsten enhanced the adhesion of osteoclasts to vitronectin-coated surfaces. BM was enriched for monocytic pre-osteoclasts and then osteoclast differentiation was induced on non-tissue culture-treated plates in the presence of M-CSF and 15 ng/ml RANKL with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten for a duration of 7 days. These cells were then seeded with M-CSF in vitronectin pre-coated plates and incubated for 45 min, as described by Brazier et al. (2009), before washing and staining for TRAP. No significant difference was observed between treated and control groups (Figure 2A). Furthermore, we tested whether tungsten altered mRNA levels of αvβ3 integrin (Itgav and Itgb3, respectively) in osteoclasts. No significant changes were observed in Itgav expression. Itgb3 mRNA levels were increased by RANKL, but tungsten did not alter this (Figure 2B). Together, these studies suggest that tungsten does not alter osteoclast adhesion to vitronectin.

Figure 2.

Tungsten does not affect adhesion of osteoclasts to vitronectin surfaces. A, Bone marrow-derived osteoclasts were differentiated on bacterial plates for 7 days and then re-seeded at 50 000 cells per well in a 24-well plate previously coated with vitronectin the night before. Cells were incubated for 45 min before washed off and TRAP stained. Four representative pictures were taken per well, summed, and average across 3 technical replicates per biological replicate. Graph shows the mean percent increase normalized to the RANKL treatment group ± SEM. n = 3. B, Expression of Itgav and Itgb3 integrin mRNA levels were assessed in M-CSF-induced osteoclasts exposed to 15 ppm tungsten, 15 ng/ml RANKL, or the combination. n = 3. *p < .05.

Tungsten Enhances the Number of RANKL-Induced Osteoclasts In Vitro

Next, we postulated that tungsten could enhance osteoclast differentiation to result in the increased osteoclast number observed in vivo (Figure 1). Thus, we tested the effects of tungsten, either alone or in combination with known osteoclast-inducer RANKL, in primary murine cultures. To do so, we isolated and enriched the monocytic pre-osteoclasts from BM, and induced osteoclast differentiation using RANKL with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten for a duration of 5–7 days depending on the concentration of RANKL. We utilized 2 different RANKL concentrations: 15 and 50 ng/ml, representing both a suboptimal and optimal concentration for osteoclastogenesis. The lower 15 ng/ml RANKL concentration induced differentiation resulting in multinucleated osteoclasts within 6–7 days. The more potent 50 ng/ml RANKL concentration induced osteoclast differentiation faster, resulting in larger multinucleated osteoclasts observed after 4–5 days. However, the majority of cells died by day 6.

Tungsten alone did not induce TRAP+ osteoclasts (Figure 3). In contrast, tungsten significantly increased the number of RANKL-induced TRAP+ osteoclasts, by 100% and 50% at 15 ng/ml or 50 ng/ml RANKL, respectively (Figure 3A). Thus, the effects of tungsten were more apparent at the lower concentration of RANKL, potentially because the higher concentration was approaching maximum osteoclastogenesis within the parameters of this assay.

Figure 3.

Tungsten enhances the number of RANKL-induced osteoclasts in vitro. Osteoclastogenesis was induced in primary bone marrow cells with 50 ng/ml MCSF and 15 or 50 ng/ml RANKL with or without 15 μg/ml tungsten. The total number of TRAP+ osteoclasts (A), as well as the total number and area of multinucleated osteoclasts (B) were enumerated. Representative images are shown, where scale bar represents 200 μm. Images (10×) were analyzed by taking the sum from 4 representative photos of each well and averaging across 4 technical replicates of each condition. The average area of multinucleated TRAP-positive osteoclasts was analyzed by measuring the size of each multinucleated osteoclast divided by the total number of TRAP-positive multinucleated osteoclasts. Graphs represent the mean ± SEM, n = 3. C, Bone marrow cells were exposed for 24 h to 15 or 50 μg/ml tungsten and the RANK expression on CD11b+ cells assessed by flow cytometry. n = 2. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Osteoclastogenesis culminates in the fusion of mononucleated osteoclasts into large multinucleated osteoclasts. In our differentiation assay, we also analyzed whether the observed increase in osteoclast number was due to increased multinucleated, large osteoclasts. However, no difference in the large osteoclasts was observed (Figure 3B), indicating that the increase observed was due to accumulation of smaller, mononucleated osteoclasts. Importantly, this was not due to an increase in RANK surface expression on CD11b+ BM cells, which includes osteoclasts (Figure 3C).

Tungsten Enhances RANKL-Induced Osteoclastic Gene Markers in Primary Osteoclasts In Vitro

We next asked whether tungsten-enhanced osteoclastogenesis correlated with enhanced gene expression of classic osteoclast markers: Nfatc1, Acp5, Ctsk, and Dcstamp. Nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (Nfatc1) is a transcription factor known to be the master regulator of osteoclastogenesis and controls expression of Acp5, Ctsk, and Dcstamp (Park et al., 2017; Wada et al., 2006). TRAP (Acp5) and cathepsin K (Ctsk) are produced by mature osteoclasts and function to resorb bone (Park et al., 2017; Wada et al., 2006), whereas dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (Dcstamp) is a protein involved in the fusion of mature osteoclasts to produce multinucleated osteoclasts (Yagi et al., 2005). We compared gene expression in primary BM-derived osteoclasts differentiated with 15 ng/ml RANKL with and without tungsten for 7 days. In agreement with the phenotypic assays, tungsten alone did not induce gene expression of the osteoclast markers (Figure 4). As expected, we observed an increase of osteoclastic gene markers upon RANKL treatment. Moreover, tungsten further enhanced expression of these markers induced by 15 ng/ml RANKL, of which Nfatc1 and Acp5 were significantly elevated. Interestingly, no statistically significant change was observed in Dcstamp gene expression following tungsten treatment, supporting the conclusion that tungsten has more of an effect on early mononucleated osteoclast differentiation, rather than fusion of mature osteoclasts.

Figure 4.

Tungsten enhances RANKL-induced osteoclastic gene markers in primary osteoclasts in vitro. Gene expression of osteoclast-specific genes (Nfatc1, Acp5, Ctsk, and Dcstamp) was quantified by qRT-PCR. Primary osteoclasts cultured in vitro in the presence of 50 ng/ml MCSF and 15 ng/ml RANKL with or without 15 ppm tungsten for 6 days, or in the presence of 50 ng/ml MCSF and 50 ng/ml RANKL with or without 15 ppm tungsten for 4 days. Graph shows the mean fold change in gene expression ± SEM. n = 3. *p < .05.

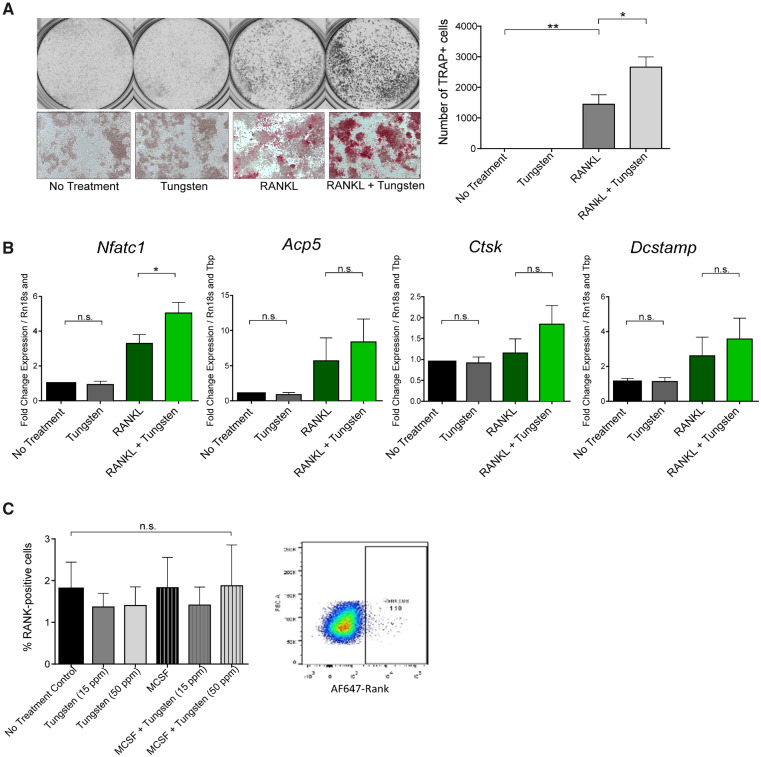

Tungsten Enhances RANKL-Induced Osteoclastogenesis in the RAW264.7 Cell Line Model

Although primary osteoclast cultures are important models for differentiation and adhesion, the number of mice needed to generate these cultures in order to explore multiple downstream molecular pathways is prohibitive. Thus, we wanted to see whether a cell line model could recapitulate what we observed with the primary osteoclast tissue culture. RAW264.7 cells are a murine monocytic cell line, which has been reported to differentiate toward osteoclasts in response to RANKL (Taciak et al., 2018). We induced osteoclastogenesis using 15 ng/ml GST-sRANKL with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten and stained for TRAP after 5 days in culture. As with our primary cultures, tungsten treatment alone did not increase osteoclast number (Figure 5A). Tungsten did enhance the number of RANKL-induced TRAP+ osteoclasts on day 5 to a level almost double of RANKL alone (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Tungsten increases the number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts in RAW 264.7 in vitro. A, RAW 264.7 were cultured with or without 15 μg/ml tungsten and with or without 15 ng/ml GST-sRANKL. After 5 days, positive TRAP staining of the total number of cells were counted using the GelCount plate scanner software. Graph shows the mean number for TRAP+ cells ± SEM, n = 4. Gray-scale pictures show representative well of each condition taken using the GelCount plate scanner and microscopic pictures are at the bottom showing the red TRAP stain. B, Gene expression of Nfatc1, Acp5, Ctsk, and Dcstamp were assessed after 24 h. Graph shows the mean ± SEM, n = 3, except for Nfatc1, n = 4. C, Cells were stained after 24 h and the RANK expression on CD11b+ cells assessed. n = 2. *p < .05; **p < .01.

We further characterized the gene expression changes of Nfatc1, Ctsk, Acp5, and Dcstamp in RAW 264.7 to see if a similar response to the primary osteoclasts was attainable. RAW 264.7 cells were induced with 15 ng/ml GST-sRANKL with or without 15 ppm tungsten for 24 h. Here, we see tungsten-enhanced RANKL-induced Nfatc1, Ctsk, and Acp5 gene expression, but not Dcstamp, similar to what was observed in the primary in vitro culture (Figure 5B). Although only Nfatc1 is significantly elevated in the tungsten-treated RAW264.7 cells, these data show that the RAW 264.7 cell line is a potential cell line model for osteoclast differentiation in vitro, and will allow us to interrogate the effects of tungsten on proteins involved in RANK-RANKL signaling. Again, like in the primary osteoclast culture, RANK surface expression was not altered on differentiated RAW264.7 cells in the presence or absence of tungsten (Figure 5C).

Tungsten Enhances MAPK Signaling Downstream of RANK-RANKL

In order to explain the enhanced osteoclasts observed in vitro and in vivo, we looked at protein phosphorylation and activation signaling downstream of RANK. Three mitogen-activated protein kinases are involved in osteoclast differentiation: p38, ERK1/2, and JNK (Lee and Seo, 2018; Matsumoto et al., 2000; Park et al., 2017; Wada et al., 2006). To do this, RAW264.7 cells were seeded and 24 h after, were treated with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten in reduced serum (2.5%). After 18 h, cells were induced with 15 ng/ml GST-sRANKL with or without 15 µg/ml tungsten, harvested accordingly, and protein expression compared with untreated controls at time 0. A 15 ng/ml GST only control was harvested at 15 min to show that the signal observed can be attributed to sRANKL and not the GST portion of GST-sRANKL. Our results show that the presence of tungsten sustains p38 phosphorylation at 45 and 60 min after RANKL stimulation (Figure 6A). Although we observe the increased activity of ERK and JNK signaling 30 min after RANKL stimuli, tungsten does not further enhance either ERK or JNK phosphorylation.

Figure 6.

Tungsten alters signaling downstream of RANK-RANKL. A, RAW 264.7 were cultured in 2.5% serum with or without 15 μg/ml tungsten 24 h after seeding, then induced with 15 ng/ml GST-sRANKL with or without 15 ppm tungsten and harvested over time. Whole cell extracts were used for immunoblots to detect levels of phospho- and total p38, phospho- and total ERK, phospho- and total JNK, phospho- and total p65, and phospho- and total mTOR. Representative blot for loading control of B-ACTIN is also shown. Numbers above phospho-blots indicate average relative densitometry values of phospho-protein/total protein/B-ACTIN across at least 3 different replicates. B, COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with an NF-κB-driven luciferase plasmid. Cells were treated with tungsten alone for 5 or 21 h or pretreated with tungsten and 20 ng/ml TNFα for the final 3 or 5 h. n = 3. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; ****p < .0001.

In addition, we looked at phosphorylation of p65 or RelA, which has be shown to increase upon RANKL stimulation and has implications in regulating the transcription of Nfatc1 after its activation and translocation to the nucleus (Lomaga et al., 1999; Naito et al., 1999; Park et al., 2017; Rucci, 2008; Wada et al., 2006). Phosphorylation of p65 was observed upon RANKL stimulation, however, no differences were observed between the tungsten treatment group and control. Because NF-κB has multiple subunits, we also performed a luciferase assay with an NF-κB response element in COS-1 cells. TNFα was used as a positive control (Figure 6B). Neither tungsten alone nor in combination with TNFα enhanced NF-κB-driven reporter activity, suggesting this is not a mechanism by which tungsten increases osteoclastogenesis.

We also investigated phosphorylation of mTOR because mTOR activation has been shown to be inhibitory toward osteoclast differentiation (Huynh and Wan, 2018). We did not observe tungsten decreasing mTOR phosphorylation at S2448 within the 1 h time frame of our experiment. (Figure 6A). Taken together, tungsten may be acting through phospho-signaling downstream of RANK-RANKL. In particular, tungsten sustains the RANKL-induced phosphorylation of p38, of which would be predicted to enhance osteoclastogenesis. Although some signals may be subtle, this may explain the increased mononucleated TRAP+ osteoclasts observed in vitro, whereas no significant difference observed in multinucleated osteoclasts.

DISCUSSION

Like many metals, tungsten accumulates in bone, but very little is known about what effects this might have to bone homeostasis. Our findings showed that tungsten exposure in vivo increases the number of osteoclasts within the bone after only 4 weeks. It is interesting to note that this increase in osteoclast formation was only observed in male mice in vivo, adding to our previous observations indicating sex-specific effects of tungsten on bone remodeling (Bolt et al., 2016). Increased osteoclast activity is suggested by the increase in CTX-1 observed in male, but not female, mice. Additional experiments should explore the potential changes at longer time points, as activity may only be significantly increased after longer durations of exposure. In addition to the use of biomarkers, such as CTX-1, histomorphometry could quantitate changes within the bone. Furthermore, we did not observe any effects on adhesion of osteoclasts, we did observe an effect on osteoclast differentiation in both a cell line and primary murine cultures. Although tungsten was unable to induce osteoclast differentiation by itself, our in vitro assays demonstrated that the combination of tungsten with the known inducer RANKL results in enhanced osteoclastogenesis without alteration in the RANK surface levels. Furthermore, the MAPK family members ERK, JNK, and p38 are the key players in osteoclast differentiation (Lee and Seo, 2018; Matsumoto et al., 2000; Park et al., 2017; Wada et al., 2006). We observed a sustained p38 signal in tungsten-treated RAW264.7 cells, yet no changes were observed in other MAPK pathways downstream of RANK-RANKL stimulation. Together, these data indicate that tungsten alters RANKL-induced signaling to promote osteoclastogenesis.

Our data adds to the growing literature that tungsten alters bone and the BM microenvironment. Here, we focused on osteoclasts, but previous studies have also demonstrated tungsten-induced changes to the other facet of bone remodeling. Bone remodeling requires both the activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, and there is significant cross-talk between the two cell types. In vitro, tungsten decreases MSC differentiation toward osteoblasts, and osteoblastic gene expression of the master transcription factor Runx2 along with downstream targets Sp7 (Osterix) and Bglap (Osteocalcin) were also decreased (Bolt et al., 2016). Thus, tungsten may alter both osteoblasts and osteoclasts; however, our in vitro model cannot capture the cross-talk of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. On the other hand, tungsten enhances adipogenesis of MSCs both in vitro and in vivo, of which tungsten may act in combination with rosiglitazone on PPARγ, a master regulator of adipogenesis (Bolt et al., 2016). Adipocytes are also capable of expressing both RANKL and OPG with roles in bone homeostasis (Hozumi et al., 2009; Muruganandan and Sinal, 2014). Thus, a coculture of MSCs in the presence of tungsten and osteoclasts may allow us to understand how tungsten may affect this interaction.

Tungsten is not the only metal known to modulate the bone. Other metals, such as lead, cadmium, and chromium also accumulate preferentially in the bone (Dermience et al., 2015; Krishnan et al., 1990; Rabinowitz, 1991; Rodriguez and Mandalunis, 2018; Sutherland et al., 2000). Lead primes MSCs toward adipogenesis, while decreasing osteoblastogenesis (Beier et al., 2013). Beier et al. also demonstrated that lead can increase osteoclastogenesis in vivo while impeding resorptive activity of osteoclasts (Beier et al., 2016). Cadmium also alters bone homeostasis by promoting osteoclast formation and resorption activity, while decreasing osteoblast activity, all of which would be predicted to decrease bone integrity (Chen et al., 2009). Of note, osteoclasts were more sensitive to the effects of cadmium than osteoblasts (Chen et al., 2009). Additionally, metals like chromium can change oxidation state as they enter the cell, resulting in reactive oxygen species formation, which further affects bone cell development (Shah et al., 2015). Like chromium, tungsten exhibits many oxidations states (0 to +6), but it is still unclear which oxidation state(s) and/or form(s) of tungsten is most relevant in the bone. Recent studies show that the predominant form of tungsten in the bone may not be sodium tungstate, but rather phosphotungstate (VanderSchee et al., 2018), suggesting that tungsten may integrate itself as part of the inorganic hydroxyapatite component of bone. Heavy metals capable of forming complex structures with bone is not unprecedented, as lead has been shown to compete with calcium for binding to hydroxyapatite and osteocalcin (Dowd et al., 2001). The incorporation of tungsten into the bone matrix could explain the slow rate of release from the bone observed (Kelly et al., 2013). Furthermore, osteoclast activity could modulate the form of tungsten within the bone. Osteoclast activity involves a resorptive pit with very low pH, and pH is known to change solubility and propensity to form polytungstates (Strigul, 2010). Thus, tungsten may move through multiple compartments and states as it transits into the bone and around BM microenvironment.

Beyond its structural role, the bone houses the BM, an important site for hematopoietic stem cell development. We and other have shown that tungsten exposure affects the developing immune system and the immune response. Tungsten alters early B cell differentiation (Kelly et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2019) and changes the immune response to virus infection (Fastje et al., 2012). Effects on other lineages or other immune challenges remain unexplored.

The current data also show that tungsten alone was insufficient to promote osteoclastogenesis. This fits with much of the previous literature suggesting that tungsten enhances the effects of other agents or exposures (Bolt and Mann, 2016). Thus, future research should consider tungsten-containing mixtures, as well as particular windows of exposure to identify particular populations at risk. As the use of tungsten increases, so does the exposure to tungsten through mining, manufacturing, and recycling, such as e-waste recycling. Together, these data contribute to the growing literature indicating that tungsten may have important effects on health.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

FUNDING

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-142227); Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN/04919-2015).

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). (2005). Toxicological Profile for Tungsten ATSDR, Atlanta, GA. Available at: www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp186.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2020. [PubMed]

- Beier E. E., Holz J. D., Sheu T. J., Puzas J. E. (2016). Elevated lifetime lead exposure impedes osteoclast activity and produces an increase in bone mass in adolescent mice. Toxicol. Sci. 149, 277–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier E. E., Maher J. R., Sheu T. J., Cory-Slechta D. A., Berger A. J., Zuscik M. J., Puzas J. E. (2013). Heavy metal lead exposure, osteoporotic-like phenotype in an animal model, and depression of wnt signaling. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt A. M., Grant M. P., Wu T. H., Flores Molina M., Plourde D., Kelly A. D. R., Negro Silva L. F., Lemaire M., Schlezinger J. J., Mwale F., et al. (2016). Tungsten promotes sex-specific adipogenesis in the bone by altering differentiation of bone marrow-resident mesenchymal stromal cells. Toxicol. Sci. 150, 333–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt A. M., Mann K. K. (2016). Tungsten: An emerging toxicant, alone or in combination. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 3, 405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt A. M., Sabourin V., Molina M. F., Police A. M., Negro Silva L. F., Plourde D., Lemaire M., Ursini-Siegel J., Mann K. K. (2015). Tungsten targets the tumor microenvironment to enhance breast cancer metastasis. Toxicol. Sci. 143, 165–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier H., Pawlak G., Vives V., Blangy A. (2009). The rho gtpase wrch1 regulates osteoclast precursor adhesion and migration. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 1391–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Shou P., Zheng C., Jiang M., Cao G., Yang Q., Cao J., Xie N., Velletri T., Zhang X., et al. (2016). Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: Adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death & Differentiation 23, 1128–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhu G., Gu S., Jin T., Shao C. (2009). Effects of cadmium on osteoblasts and osteoclasts in vitro. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 28, 232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claret M., Corominola H., Canals I., Saura J., Barcelo-Batllori S., Guinovart J. J., Gomis R. (2005). Tungstate Decreases Weight Gain and Adiposity in Obese Rats through Increased Thermogenesis and Lipid Oxidation. Endocrinology 146, 4362–4369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermience M., Lognay G., Mathieu F., Goyens P. (2015). Effects of thirty elements on bone metabolism. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 32, 86–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd T. L., Rosen J. F., Mints L., Gundberg C. M. (2001). The effect of Pb(2+) on the structure and hydroxyapatite binding properties of osteocalcin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1535, 153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA. (2008). Emerging contaminant - Tungsten Fact sheet. 505-F-07-005. EPA, Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/nscep. Accessed November 4, 2020.

- EPA. (2012). Technical fact sheet - Tungsten EPA, Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/nscep. Accessed November 4, 2020.

- Fastje C. D., Harper K., Terry C., Sheppard P. R., Witten M. L. (2012). Exposure to sodium tungstate and respiratory syncytial virus results in hematological/immunological disease in c57bl/6j mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 196, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitens J. M., Condon M., Squibb K. S., Centeno J. A., McDiarmid M. A. (2017). Metal exposure in veterans with embedded fragments from war-related injuries: Early findings from surveillance efforts. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 59, 1056–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guandalini G. S., Zhang L., Fornero E., Centeno J. A., Mokashi V. P., Ortiz P. A., Stockelman M. D., Osterburg A. R., Chapman G. G. (2011). Tissue distribution of tungsten in mice following oral exposure to sodium tungstate. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 24, 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozumi A., Osaki M., Goto H., Sakamoto K., Inokuchi S., Shindo H. (2009). Bone marrow adipocytes support dexamethasone-induced osteoclast differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 382, 780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh H., Wan Y. (2018). Mtorc1 impedes osteoclast differentiation via calcineurin and nfatc1. Commun. Biol. 1, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A. D., Lemaire M., Young Y. K., Eustache J. H., Guilbert C., Molina M. F., Mann K. K. (2013). In vivo tungsten exposure alters b-cell development and increases DNA damage in murine bone marrow. Toxicol. Sci. 131, 434–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsospyros A., Braida W., Christodoulatos C., Dermatas D., Strigul N. (2006). A review of tungsten: From environmental obscurity to scrutiny. J. Hazard. Mater. 136, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S. S., Lui S. M., Jervis R. E., Harrison J. E. (1990). Studies of cadmium uptake in bone and its environmental distribution. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 26-27, 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Seo I., Choi M. H., Jeong D. (2018). Roles of mitogen-activated protein kinases in osteoclast biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett R. W. (1997). A model of the distribution and retention of tungsten in the human body. Sci. Total Environ. 206, 147–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemus R., Venezia C. F. (2015). An update to the toxicological profile for water-soluble and sparingly soluble tungsten substances. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 45, 388–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomaga M. A., Yeh W. C., Sarosi I., Duncan G. S., Furlonger C., Ho A., Morony S., Capparelli C., Van G., Kaufman S., et al. (1999). Traf6 deficiency results in osteopetrosis and defective interleukin-1, cd40, and lps signaling. Genes Dev 13, 1015–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M., Sudo T., Saito T., Osada H., Tsujimoto M. (2000). Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in osteoclastogenesis mediated by receptor activator of nf-kappa b ligand (rankl). J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31155–31161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki A., Takami M., Miyamoto Y., Nakamaki T., Tomoyasu S., Kadono Y., Tanaka S., Inoue T., Kamijo R. (2012). Cell adhesion signaling regulates rank expression in osteoclast precursors. PLoS One 7, e48795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz M. C., Barbera A., Dominguez J., Fernandez-Alvarez J., Gomis R., Guinovart J. J. (2001). Effects of Tungstate, a New Potential Oral Antidiabetic Agent, in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats. Diabetes 50, 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muruganandan S., Sinal C. J. (2014). The impact of bone marrow adipocytes on osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation. IUBMB Life 66, 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito A., Azuma S., Tanaka S., Miyazaki T., Takaki S., Takatsu K., Nakao K., Nakamura K., Katsuki M., Yamamoto T., et al. (1999). Severe osteopetrosis, defective interleukin-1 signalling and lymph node organogenesis in traf6-deficient mice. Genes Cells 4, 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Toxicology Program (NTP). (2002). Priority Substance List Nomination Summary-Tungsten Available at: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/testing/noms/search/summary/nm-n20226.html. Accessed April 2, 2020.

- Park J. H., Lee N. K., Lee S. Y. (2017). Current understanding of rank signaling in osteoclast differentiation and maturation. Mol. Cells 40, 706–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz M. B. (1991). Toxicokinetics of bone lead. Environ. Health Perspect. 91, 33–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodan S. B., Rodan G. A. (1997). Integrin function in osteoclasts. J. Endocrinol. 154 Suppl, S47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J., Mandalunis P. M. (2018). A review of metal exposure and its effects on bone health. J. Toxicol. 2018, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucci N. (2008). Molecular biology of bone remodelling. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 5, 49–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah Idil A., Donaldson N. (2018). The use of tungsten as a chronically implanted material. J. Neural Eng. 15, 021006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah K. M., Quinn P. D., Gartland A., Wilkinson J. M. (2015). Understanding the tissue effects of tribo-corrosion: Uptake, distribution, and speciation of cobalt and chromium in human bone cells. J. Orthop. Res. 33, 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty S., Kapoor N., Bondu J. D., Thomas N., Paul T. V. (2016). Bone turnover markers: Emerging tool in the management of osteoporosis. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 20, 846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strigul N. (2010). Does speciation matter for tungsten ecotoxicology? Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 73, 1099–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland J. E., Zhitkovich A., Kluz T., Costa M. (2000). Rats retain chromium in tissues following chronic ingestion of drinking water containing hexavalent chromium. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 74, 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taciak B., Białasek M., Braniewska A., Sas Z., Sawicka P., Kiraga Ł., Rygiel T., Król M. (2018). Evaluation of phenotypic and functional stability of raw 264.7 cell line through serial passages. PLoS One 13, e0198943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Nakayamada S., Okada Y. (2005). Osteoblasts and osteoclasts in bone remodeling and inflammation. Curr. Drug Targets Inflam. Allergy 4, 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas V. G., Roberts M. J., Harrison P. T. (2009). Assessment of the environmental toxicity and carcinogenicity of tungsten-based shot. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 72, 1031–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaananen H. K., Zhao H., Mulari M., Halleen J. M. (2000). The cell biology of osteoclast function. J. Cell Sc. 113(Pt 3), 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderSchee C. R., Kuter D., Bolt A. M., Lo F.-C., Feng R., Thieme J., Chen-Wiegart Y-cK., Williams G., Mann K. K., Bohle D. S. (2018). Accumulation of persistent tungsten in bone as in situ generated polytungstate. Commun. Chem. 1, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Voronov I., Heersche J. N., Casper R. F., Tenenbaum H. C., Manolson M. F. (2005). Inhibition of osteoclast differentiation by polycyclic aryl hydrocarbons is dependent on cell density and rankl concentration. Biochem. Pharmacol. 70, 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T., Nakashima T., Hiroshi N., Penninger J. M. (2006). Rankl-rank signaling in osteoclastogenesis and bone disease. Trends Mol. Med. 12, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. H., Bolt A. M., Chou H., Plourde D., De Jay N., Guilbert C., Young Y. K., Kleinman C. L., Mann K. K. (2019). Tungsten blocks murine b lymphocyte differentiation and proliferation through downregulation of il-7 receptor/pax5 signaling. Toxicol. Sci. 170, 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi M., Miyamoto T., Sawatani Y., Iwamoto K., Hosogane N., Fujita N., Morita K., Ninomiya K., Suzuki T., Miyamoto K., et al. (2005). Dc-stamp is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Exp. Med. 202, 345–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.