To the Editor:

The Public Health response to COVID-19 pandemic has implied strict measures, including social distancing and self-protection enhancement, together with priority shifts in health care resources. Chronic patients have been especially affected by such measures. However, initial reports have shown reductions in the incidence of emergency conditions such as myocardial infarction.1 , 2 Although data from Veterans Affairs Hospitals suggest a steep decrease in hospital admissions,3 information for COPD exacerbations is scarce. Therefore, we aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown (consisting of the limitation of free movement except for acquiring food and medicines, seeking health care, and attending work in essential services) on COPD exacerbations, symptoms, and health care costs in a cohort of well-characterized Spanish COPD patients. This analysis is key, because COPD exacerbations negatively impact health status, rates of hospitalization, and disease progression.4

Methods

Data from all COPD patients visiting the specialized pulmonary consultation of University Hospital Arnau de Vilanova (Lleida, Spain) in 2019 were collected retrospectively from electronic medical records. Telephonically administered surveys with standardized scripting were used to assess pulmonary symptoms (including modified Medical Research Council [mMRC] dyspnea scale and COPD Assessment Test [CAT]), social and labor situations, lockdown enforcement (times leaving home per week), and number and type of COPD exacerbations during the lockdown period in Spain (March 1 to May 31, 2020). All exacerbations were confirmed through comprehensive review of each patient’s electronic medical records to assess the exact date and type of exacerbation based on Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines4: mild exacerbations, those treated with short-acting bronchodilators; moderate exacerbations, those treated with short-acting bronchodilators plus antibiotics or oral corticosteroids; or severe exacerbations, those requiring visits to the ED or hospitalization. Health care costs related to COPD exacerbations (ED visits and hospital admissions) were calculated using official pricings from the Catalan Health Department, updated to May 2020 by the Consumer Price Index. Data on exacerbations, symptoms, and costs were compared for the periods March 1 to May 31, 2019 (before COVID-19) and March 1 to May 31, 2020 (during COVID-19 lockdown), using McNemar’s test, paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Fisher exact test, and mixed proportional-odds model, with the predictors being period (as fixed effect) and patient (as random effect), as appropriate. The alpha value defining statistical significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed using R-project version 3.5.2. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Arnau de Vilanova (CEIC-2299), and all patients provided informed consent.

Results

Of the 369 COPD patients that were visited during 2019, 24 patients had died since their last visit, 31 patients could not be contacted after three calls on different days, and four patients did not consent to participate. Finally, 310 COPD patients were included (mean [SD] age of 67 [8]; 83% male; 79% former smokers; and mean [SD] BMI 28.5 [6]). No significant differences were found in the characteristics of included and excluded patients. Spirometric measures before COVID-19 lockdown showed that the cohort had moderate to severe COPD (mean [SD] predicted percentage of FEV1, 52% [19%]; total lung capacity 92% [23%]; residual volume 145% [65%]; and adjusted diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide 49% [19%]). Most patients were classified as GOLD II (38%) or III (37%), with 37% in GOLD A and 21% in GOLD D, based on symptoms and exacerbations. Most patients were retired (78%) and experienced a strong lockdown enforcement (56% of patients reporting not leaving home at all, and 26% reported leaving home three or fewer times per week during the lockdown period).

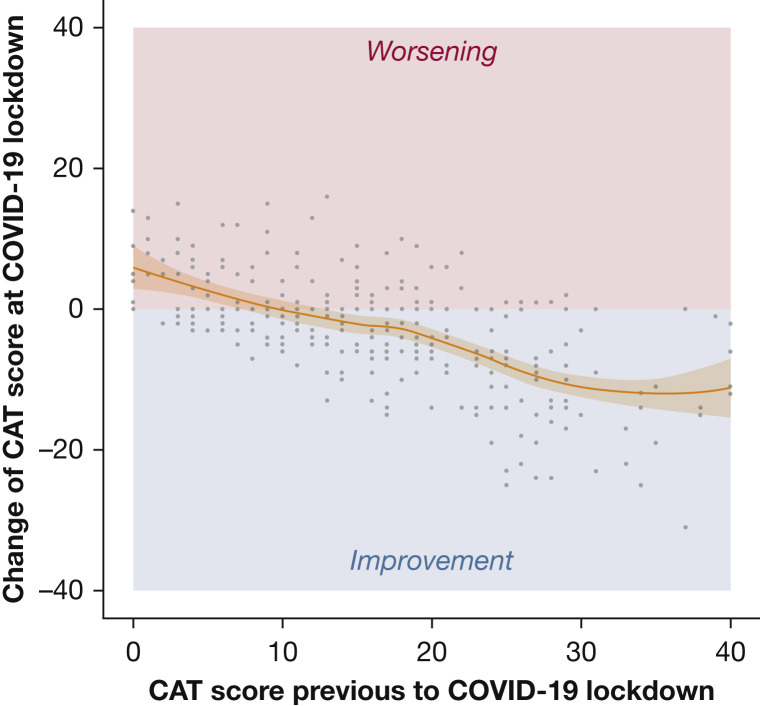

Table 1 shows the comparison of exacerbations and symptoms before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. A 62% decrease in the number of COPD exacerbations was observed. This difference was focused in the number of moderate and severe exacerbations. Regarding symptoms, patients reported better overall CAT score (Fig 1 ) and better scores in all of its dimensions (Table 1) during lockdown. In contrast, the severity of dyspnea worsened during lockdown, although this difference had little clinical relevance (+0.35 points on average). Finally, a 74% reduction in COPD-related health care costs was found.

Table 1.

Comparison of Exacerbations and Symptoms and Health Care Costs Before and During COVID-19 Lockdown

| Exacerbations, Symptoms and Costs | 2019 (Before Lockdown) | 2020 (During Lockdown) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exacerbations | n = 310 | n = 310 | |

| Total exacerbations, No. (%) | 102 (32.9) | 39 (12.6) | <.001 |

| Average exacerbations per patient, mean (SD) | 0.37 (0.56) | 0.14 (0.37) | <.001 |

| Exacerbations according to severity, No. (%) | .153b | ||

| Mild | 5 (4.9%) | 5 (12.8%) | |

| Moderate | 67 (65.7%) | 27 (69.2%) | |

| Severe | 30 (29.4%) | 7 (17.9%) | |

| Length of hospital stay, mean (SD) | 13.1 (11.3) | 13.1 (15.4) | .999 |

| CAT questionnaire | n = 279 | n = 279 | |

| Severity, No. (%) | <.001c | ||

| Low (<10) | 76 (27.2) | 98 (35.1) | |

| Medium (10-20) | 118 (42.3) | 131 (47.0) | |

| High (21-30) | 66 (23.7) | 44 (15.8) | |

| Very high (>30) | 19 (6.81) | 6 (2.15) | |

| Total score, mean (SD) | 16.2 (9.46) | 13.2 (7.76) | <.001 |

| Dimensions, No. (%) | |||

| Cough | 1.92 (1.67) | 1.53 (1.35) | <.001 |

| Mucus | 2.32 (1.71) | 1.62 (1.49) | <.001 |

| Oppression | 1.33 (1.73) | 0.82 (1.24) | <.001 |

| Stairs | 3.58 (1.67) | 3.13 (1.60) | <.001 |

| Home | 2.45 (1.98) | 1.97 (1.82) | <.001 |

| Street | 1.80 (1.83) | 1.27 (1.67) | <.001 |

| Sleep | 1.52 (1.79) | 0.76 (1.39) | <.001 |

| Power | 2.64 (1.75) | 2.14 (1.43) | <.001 |

| mMRC dyspnea scale | n = 302 | n = 302 | |

| Severity, No. (%) | <.001c | ||

| Degree 0 | 59 (19.3) | 45 (14.7) | |

| Degree 1 | 111 (36.4) | 91 (29.6) | |

| Degree 2 | 72 (23.6) | 79 (25.7) | |

| Degree 3 | 53 (17.4) | 54 (17.6) | |

| Degree 4 | 10 (3.28) | 38 (12.4) | |

| Total score, mean (SD) | 1.48 (1.09) | 1.83 (1.23) | <.001 |

| COPD-related health care costs (€ /patient) | n = 310 | n = 310 | |

| Emergency visits (primary care), mean (95%CI) | 16 (13-20) | 7 (4-9) | <.001 |

| Emergency visits (hospital), mean (95%CI) | 15 (10-21) | 4 (1-8) | <.001 |

| Hospitalizations, mean (95%CI) | 421 (209-634) | 109 (0-233) | <.001 |

| Total costs, mean (95%CI) | 453 (237-669) | 120 (0-246) | <.001 |

Compared periods: March 1 to May 31, 2019 (before lockdown) and March 1 to May 31, 2020 (during lockdown).

CAT = COPD Assessment Test; mMRC = modified Medical Research Council.

McNemar’s test or paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate.

Fisher exact test.

Mixed proportional-odds model with the predictors being period (as fixed effect) and patient (as random effect).

Figure 1.

Changes in CAT score before and during COVID-19 lockdown. A generalized additive model with penalized cubic regression spline assessing the association between the change of CAT (outcome) and baseline CAT score (predictor). The shaded area corresponds to 95% CIs. CAT = COPD Assessment Test.

Discussion

The analysis of data from a well-characterized cohort of COPD patients before and during COVID-19 lockdown suggests a significant reduction in COPD exacerbations, an improvement in symptoms, and a significant reduction in COPD-related health care costs. There are several possible explanations for these findings. First, because exacerbations are triggered primarily by respiratory viral infections or, to a lesser extent, bacterial infections and air pollution,5 the combination of self-protection measures (social-distancing and use of face masks) and the decrease in air pollutants attributable to reduced human activities6 could have impacted positively on COPD exacerbations and symptoms. Next, patients’ perception of vulnerability could have prompted a strict adherence to guidelines and good practices, as demonstrated by the high degree of lockdown enforcement reported in the cohort, or reports suggesting an improvement in asthma and COPD treatment adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic.7 Finally, the possibility of patients being afraid of seeking medical attention for COPD exacerbations during the COVID-19 pandemic also should be considered.

This study has several potential limitations: (1) not all subjects from the cohort could be contacted and reply to the surveys; (2) the pre-post design could be biased by seasonal trends, although the period March through May is usually fairly stable between years; (3) the generalizability of the results to other countries could be dependent on the local health care setting and the characteristics of the applied lockdown measures; and (4) mMRC dyspnea scale and CAT were delivered face-to-face in 2019 but telephonically during the lockdown. However, both tools were administered by the same professionals and are well known to participants, and the mode of administration does not influence the CAT score or its psychometric properties.8

In conclusion, results suggest that the lockdown was associated with a reduction in COPD exacerbations and an improvement in symptoms. An in-depth analysis of factors potentially explaining these results, as well as the impact of the new post-lockdown scenario, should be assessed in future studies.

Acknowledgments

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL/NONFINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: None declared

FUNDING/SUPPORT: J. de Batlle acknowledges receiving financial support from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII; Miguel Servet 2019: CP19/00108), co-funded by the European Social Fund (ESF), “Investing in your future.”

References

- 1.De Filippo O., D’Ascenzo F., Angelini F., et al. Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during Covid-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):88–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon M.D., McNulty E.J., Rana J.S., et al. The Covid-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):691–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum A., Schwartz M.D. Admissions to Veterans Affairs hospitals for emergency conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(1):96–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh D., Agusti A., Anzueto A., et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: the GOLD Science Committee Report 2019. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(5):1900164. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00164-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li M.H., Fan L.C., Mao B., et al. Short-term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter increases hospitalizations and mortality in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2016;149(2):447–458. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L., Li Q., Huang L., et al. Air quality changes during the COVID-19 lockdown over the Yangtze River delta region: an insight into the impact of human activity pattern changes on air pollution variation. Sci Total Environ. 2020;732:139282. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaye L., Theye B., Smeenk I., Gondalia R., Barrett M.A., Stempel D.A. Changes in medication adherence among patients with asthma and COPD during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(7):2384–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agusti A., Soler-Cataluña J.J., Molina J., et al. Does the COPD assessment test (CAT(TM)) questionnaire produce similar results when self- or interviewer administered? Qual Life Res. 2015;24(10):2345–2354. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0983-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]